Abstract

We have previously identified and characterized two novel nuclear RNA binding proteins, p34 and p37, which have been shown to interact with a family of nucleolar phosphoproteins, NOPP44/46, in Trypanosoma brucei. These proteins are nearly identical, the major difference being an 18-amino-acid insert in the N terminus of p37. In order to characterize the interaction between p34 and p37 and NOPP44/46, we have utilized an RNA interference (RNAi) cell line that specifically targets p34 and p37. Within these RNAi cells, we detected a disruption of a higher-molecular-weight complex containing NOPP44/46, as well as a dramatic increase in nuclear NOPP44/46 protein levels. We demonstrated that no change occurred in NOPP44/46 mRNA steady-state levels or stability, nor was there a change in cellular protein levels. These results led us to investigate whether p34 and p37 regulate NOPP44/46 cellular localization. Examination of the p34 and p37 amino acid sequences revealed a leucine-rich nuclear export signal, which interacts with the nuclear export factor exportin 1. Immune capture experiments demonstrated that p34, p37, and NOPP44/46 associate with exportin 1. When these experiments were performed with p34/p37 RNAi cells, NOPP44/46 no longer associated with exportin 1. Sequential immune capture experiments demonstrated that p34, p37, NOPP44/46, and exportin 1 exist in a common complex. Inhibiting exportin 1-mediated nuclear export led to an increase in nuclear NOPP44/46 proteins, indicating that they are exported from the nucleus via this pathway. Together, our results demonstrate that p34 and p37 regulate NOPP44/46 cellular localization by facilitating their association with exportin 1.

African trypanosomes are the causative agents of African sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in cattle (22). This parasite continues to pose a serious threat to human health and to cause devastating economic losses (25). African trypanosomiasis is a reemerging infectious disease with estimates ranging between 300,000 and 500,000 new cases each year (34). This rise in infection rates is due, in part, to an increase in parasite drug resistance and vector pesticide resistance.

In previous work from our laboratory, two Trypanosoma brucei RNA binding proteins, p34 and p37, were identified and characterized (39, 40). The only major difference between them is an 18-amino-acid insert located within the amino terminus of p37 that is absent in p34. These proteins contain two RNA binding domains (RBD) within the central coding region, and they have been shown to interact with 5S rRNA (31). In addition to the interaction with 5S rRNA, p34 and p37 have been found to interact with a family of nucleolar phosphoproteins, NOPP44/46 (30). These abundant proteins have been identified and characterized by M. Parsons and colleagues (9, 10, 27, 29). An interaction(s) between p34 and p37 and NOPP44/46 was mapped through yeast two-hybrid analysis and protein affinity chromatography and was shown to be mediated via the RNA binding domain of p34 and p37 (30). Thus, the RBD region of p34 and p37 serves to mediate a protein-RNA interaction with 5S rRNA as well as the protein-protein interaction with the NOPP44/46 proteins. At this time, we do not know whether these interactions are cooperative or competitive.

Here, we employ a T. brucei cell line expressing RNA interference (RNAi) that specifically targets both p34 and p37 (19) to further examine the cellular role of the interaction between p34 and p37 and the NOPP44/46 proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Procyclic-form T. brucei brucei strain 427 was grown in Cunningham's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (8). Clonal p34/p37 RNAi procyclic cells have been previously described (19). Induction of p34/p37 double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) was initiated with the addition of tetracycline (1.0 μg/ml; Sigma) at a cell concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml.

Antibodies.

Antibodies utilized were the following: p34/p37 polyclonal antiserum (39), NOPP44/46 monoclonal antiserum (29), and NOPP44/46 peptide antibody (raised to the peptide CEDMESYGVPPKRGGKS; Bethyl Laboratories); antiserum to T. brucei phosphoglycerate kinase (28); polyclonal antiserum to the T. brucei RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain (9); anti-XpoI (6), polyclonal antiserum to the T. brucei poly(A) binding protein (PABP); and β-tubulin monoclonal antibody (Chemicon).

Nuclear extract preparation and sucrose gradient analysis.

Nuclear extracts were prepared (32) from wild-type cells and p34/p37 clonal RNAi cells at 2 days postinduction of dsRNA expression. Nuclear extracts (either 0.1 or 1.0 mg total protein as determined by the Bradford method) were applied to a continuous sucrose gradient (10 to 30%) and sedimented (31). Total protein from gradient fractions was precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), resolved on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). Western blot analysis was performed with antibodies directed against p34 and p37 or the NOPP44/46 proteins.

Isolation of trypanosome nuclei.

Nuclei were isolated from wild-type cells and p34/p37 RNAi cells as described elsewhere (33). Briefly, 2.5 × 1010 procyclic cells were pelleted and resuspended in 8% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP; Sigma) containing 0.05% Triton X-100 (Sigma), 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), mammalian protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and solution P (100 mg phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mg pepstatin A in 5 ml of ethanol). Cells were homogenized and passed through a 25-gauge needle. The lysate was underlaid with 0.3 M sucrose in 8% PVP, solution P, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor mixture and sedimented at 11,000 × g. The resulting top layer containing the cytoplasmic material was stored at −80°C. The pellet containing the crude nuclear extract was resuspended in 8 ml of 2.1 M sucrose in 8% PVP, DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail, and solution P (final volume containing approximately 2 × 1010 cell equivalents). A 12-ml aliquot of this mixture was applied to a discontinuous gradient in an SW28 tube (bottom to top, 8 ml 2.3 M sucrose-PVP, 8 ml 2.1 M sucrose-PVP, 8 ml 2.01 M sucrose-PVP) and sedimented at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. Nuclei were recovered from the 2.1/2.3 interface. The protein concentration of the cytoplasmic and nuclear isolates was determined using the Bio-Rad RC DC protein assay.

Analysis of protein steady-state levels and cellular distribution.

Total cellular protein was prepared from an equivalent number (5 × 106) of wild-type cells and cells expressing p34/p37 dsRNA by resuspension in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (16) and boiling for 5 minutes. Half of each sample was electrophoresed in two separate 12% SDS-PAGE gels, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes and Western blot analysis (39). Each pair was analyzed using NOPP44/46 monoclonal antiserum or p34/p37 polyclonal antiserum for one blot and β-tubulin antibody (Chemicon) for the other blot as an internal loading control. Densitometric analysis was performed using a GS-700 imaging densitometer in combination with the Multi-Analyst software (Bio-Rad) with the corresponding wild type as the reference.

For analysis of protein cellular distribution, 25 μg of cytoplasmic and purified nuclear extracts from wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells was analyzed by Western blot analysis as described above.

Analysis of mRNA steady-state and stability assays.

Total RNA was isolated from 5 × 106 wild-type or p34/p37 RNAi cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Serial dilutions of total RNA were resolved by electrophoresis through a 2% agarose-formaldehyde gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). Northern blot analysis was performed using oligonucleotide probes as previously described (31, 39), and the blots were processed for subsequent analysis (3). Oligonucleotides directed against small subunit (SSU; 18S) and large subunit (LSU; 28S) rRNA were utilized as loading controls. The oligonucleotide probe used to detect the presence of NOPP44/46 mRNA was the U-3 primer 5′-CGCGTCAATTCCTTCATTGTCCT-3′ (10).

For analysis of mRNA stability, actinomycin D (10 μg/ml; Sigma) was added to wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells, after which total RNA was isolated at the indicated time points. For each sample, 5 μg of total RNA was resolved through a 2% agarose-formaldehyde gel and examined by Northern blot analysis as above. Densitometric analysis for both steady-state and stability assays was performed as described above.

Cellular fractionation for immune capture and LMB experiments.

Wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells were grown to the appropriate density (1 × 106 cells/ml and 1 × 108 cells/ml for leptomycin B [LMB] and immune capture [IC] experiments, respectively), after which they were fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts (32). Protein concentration was quantified using the Bradford method as indicated elsewhere (2).

IC and Western blot experiments.

A 500-μg aliquot of wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi nuclear extract was used for each IC sample. Prior to IC, 100 μl Dynabeads (Dynal) was cross-linked to anti-XpoI antibody (6). Cross-linking was performed as per the manufacturer's instructions. As a negative control, no antibody was added to one reaction mixture to control for proteins interacting nonspecifically with the beads. Following cross-linking, nuclear extracts were added to the beads and incubated overnight at 4°C. Supernatants were collected from the experimental reaction mixtures, and beads were washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The beads from each reaction mixture were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for 16 h at 125 V. To detect the presence of p34 and p37 proteins in the IC reaction mixtures, the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked in 10% nonfat dry milk followed by incubation with anti-p34/p37 polyclonal antiserum. Goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was used as the secondary antibody, and proteins were detected using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce). In order to detect the presence of NOPP44/46 in these samples, Western blots were stripped with buffer containing 0.2 M glycine and 0.05% Tween 20 at a final pH of 2.5 at 80°C for 30 min (S. Howell, Western protocol [http://cancer.ucsd.edu/howelllab/Western.html]). NOPP44/46 were detected as described above using monoclonal anti-NOPP44/46 antiserum.

Sequential immune capture experiments.

Immune capture experiments using anti-XpoI were performed as described above. Following incubation with nuclear extracts, beads were washed with PBS and bound proteins were eluted using PBS with 1% SDS, 50 mM DTT, and 10% β-mercaptoethanol (17). Reaction mixtures were boiled for 5 min, diluted to a 100-μl total volume, and allowed to renature at room temperature. Diluted samples were used for p34 and p37 immune captures as described above. Samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis probing for NOPP44/46.

LMB experiments.

A total of 2.0 × 106 wild-type procyclic cells were treated with LMB (a gift from D. Campbell, UCLA) at a final concentration of 0.001 ng/cell, and aliquots of 1.0 × 106 cells were taken at 0, 12, 24, and 48 h. Following treatment, cells were fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts as described above. The equivalent of 1.0 × 106 cells for each sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE using 5 to 20% gradient gels for 16 h at 150 V. The gel was cut in half at the 60-kDa marker band, and each half was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blot analysis to detect the presence of NOPP44/46 (lower half of the gel) in each sample was performed as described above. For a loading control, the upper half of the gel was used for Western blot analysis against the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Densitometric analysis was performed as described above.

RESULTS

Loss of p34 and p37 leads to an increase in nuclear levels of NOPP44/46 protein.

We have previously shown that p34 and p37 interact with the NOPP44/46 proteins in both stages of the trypanosome life cycle, suggesting this protein-protein interaction serves a conserved role within the parasite (30). RNA interference of the p34 and p37 proteins was employed in order to further characterize this interaction. We have previously established a clonal cell line which, upon addition of tetracycline, induces production of dsRNA specific to p34 and p37 (19). This leads to degradation of p34 and p37 mRNA and a phenotypic absence of these proteins, which were shown to be essential for survival of the parasite.

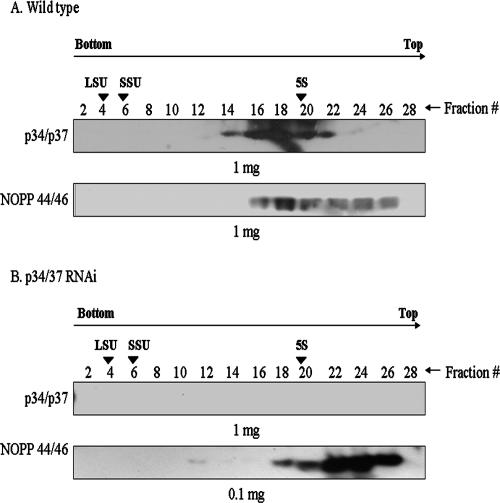

Since p34 and p37 and the NOPP44/46 proteins are predominantly localized to the nucleus and nucleolus, respectively, we first investigated this interaction in nuclear extracts, which contain both nuclear and nucleolar material. To determine whether loss of p34 and p37 disrupts NOPP44/46-containing complexes, we examined nuclear extracts that were sedimented through a continuous 10 to 30% sucrose gradient. Figure 1 is representative of five separate experiments. Two overlapping peaks that contain NOPP44/46 were consistently detected in sucrose gradient fractions of nuclear extracts from wild-type procyclic cells (Fig. 1A, bottom panel). The first of these peaks comigrates with p34 and p37 (fractions 18 to 22), while the second peak does not (fractions 24 and 26). In the p34/p37 RNAi cell extracts, the first peak of NOPP44/46, which previously migrated with p34 and p37, was lost (Fig. 1B, lower panel, fractions 18 and 20). The second peak of NOPP44/46 proteins, which did not comigrate with p34 and p37, was still present. This suggests that, in wild-type cells, p34 and p37 and the NOPP44/46 proteins are part of a higher-molecular-weight complex(es) and that loss of p34 and p37 leads to disruption or alterations within this complex(es). We also observed that the abundance of the NOPP44/46 proteins in p34/p37 RNAi nuclear extracts was significantly increased. For comparison purposes, in the bottom panel of Fig. 1B, 0.1 mg (compared to 1.0 mg in Fig. 1A, bottom panel) of p34/p37 RNAi nuclear extracts had to be used for sedimentation analysis to allow for comparable exposures of these blots. Hence, these experiments demonstrate that an increase in nuclear NOPP44/46 protein levels occurred in the absence of p34 and p37.

FIG. 1.

Sucrose gradient sedimentation analysis of NOPP44/46. Nuclear extracts were prepared from wild-type procyclic cells (A) and cells expressing p34/p37 dsRNA (B). The amount of nuclear extract indicated was sedimented through a continuous 10 to 30% sucrose gradient. Fractions were collected and TCA precipitated. Western blot analysis was performed to detect the positions of p34 and p37 as well as the NOPP44/46 proteins. Fraction 2 designates the bottom of the gradient. The positions of 5S rRNA, small subunit (18S) rRNA, and large subunit (28S) rRNA markers are indicated.

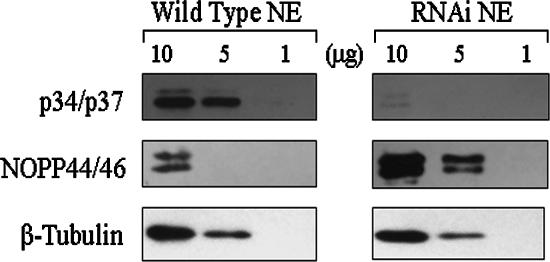

To further explore this phenomenon, we examined the level of NOPP44/46 proteins by using an equivalent amount of nuclear extract from wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells. Using exposures from each experiment in the linear range, Western blot analysis from five separate experiments demonstrated a 12-fold ± 0.3-fold increase in the levels of NOPP44/46 in the p34/p37 RNAi nuclear extracts (Fig. 2, compare NOPP44/46 wild type versus RNAi). These results indicate that p34 and p37 may serve to regulate expression of the NOPP44/46 proteins.

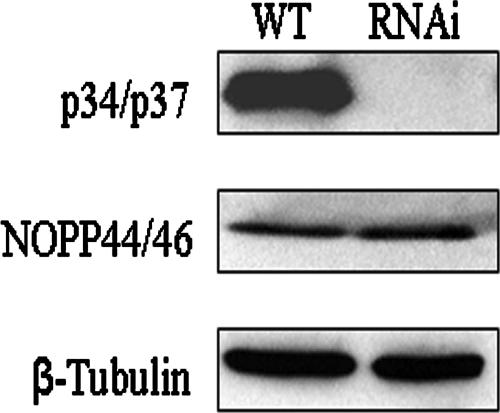

FIG. 2.

Analysis of NOPP44/46 protein levels within nuclear extracts. The indicated amount of nuclear extracts (NE) from either wild-type or p34/p37 RNAi cells was analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies directed against p34 and p37 (upper panel), NOPP44/46 (middle panel), and a β-tubulin loading control (lower panel).

p34 and p37 do not regulate NOPP44/46 mRNA levels in vivo.

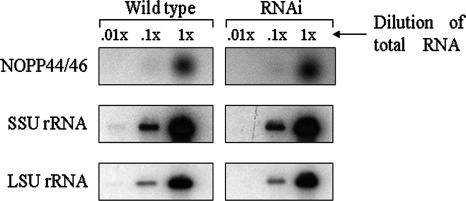

We wished to determine at which level p34 and/or p37 acts to regulate NOPP44/46 expression. In order to determine whether p34 and p37 affect NOPP44/46 transcript abundance, steady-state levels of transcript were analyzed in both wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells. Total RNA was isolated from an equivalent number of wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells, followed by Northern blot analysis. No significant differences were found in the levels of NOPP44/46 transcripts in wild-type versus p34/p37 RNAi cells (Fig. 3, top panel, compare wild type to RNAi) compared to the small and large subunit rRNA controls (middle and bottom panels, respectively). An average of at least three separate experiments demonstrated only a 1.17-fold ± 0.15-fold difference in NOPP44/46 transcript abundance between wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells. These results indicate that p34 and p37 do not regulate the steady-state level of NOPP44/46 transcript.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of NOPP44/46 mRNA steady-state levels within wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells. Total RNA was isolated from an equivalent number (5 × 106) of wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells. Northern blot analysis was performed using oligonucleotide probes specific to NOPP44/46 mRNA (upper panel), SSU rRNA (middle panel), and LSU rRNA (lower panel). The left panels include dilutions of total RNA from wild-type cells, and the right panels include dilutions of total RNA from p34/p37 RNAi cells.

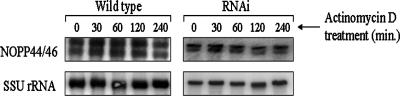

Another possibility was that p34 and p37 serve to regulate NOPP44/46 transcript stability, leading to an increase in protein levels in the p34/p37 RNAi cells. In order to determine this, RNA stability assays were performed. Actinomycin D was added to both wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells to inhibit RNA polymerase II activity, and total RNA was isolated at increasing time points (Fig. 4). NOPP44/46 mRNA (Fig. 4, top panel) was quite stable in both wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells (Fig. 4, top panel, compare wild type to RNAi) compared to the SSU rRNA loading control (Fig. 4, lower panel), showing very little degradation over 4 hours. Upon quantification of three separate experiments, we found an average of only a 1.26-fold ± 0.02-fold difference in stability of the NOPP44/46 transcript between wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells over a 4-hour period, which does not account for the differences in protein levels seen in Fig. 1 and 2. Additionally, all forms of NOPP44/46 (10) are equally stable in these experiments. Overall, our results suggest that NOPP44/46 transcript steady-state levels and stability are not changed in the p34/p37 RNAi cells compared to wild-type cells. We thus conclude that p34 and p37 do not regulate NOPP44/46 at the level of transcript.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of NOPP44/46 mRNA stability within wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells. Actinomycin D was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Total RNA was isolated at increasing time points, and 5 μg of each sample was analyzed. Probes specific to NOPP44/46 mRNA (upper panel) and SSU rRNA (lower panel) were utilized in Northern blot analyses.

p34 and p37 do not alter cellular NOPP44/46 protein levels in vivo.

We had demonstrated that p34 and p37 do not regulate NOPP44/46 at the level of transcript abundance or stability (Fig. 3 and 4), and so we next wished to determine whether they regulate the total cellular levels of NOPP44/46 protein. An equivalent number of wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells were lysed, and protein levels were examined via Western blot analysis. The results shown are representative of four separate experiments. Surprisingly, no change in the overall protein levels of NOPP44/46 occurred within the p34/p37 RNAi cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. 5, middle panel). This is in contrast to what was seen within the nuclear fraction of p34/p37 RNAi cells (Fig. 2, middle panel, compare wild type to RNAi), suggesting that p34 and p37 act to regulate NOPP44/46 cellular localization.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of NOPP44/46 total protein levels. Total cellular protein was prepared from an equivalent number (5 × 106) of wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells. In each experiment, half of the cell suspension was applied to two separate SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and samples were processed for Western blot analysis, probing for either p34 and p37 (top panel) or NOPP44/46 (middle panel). A representative blot for the β-tubulin loading control is shown (lower panel).

Loss of p34 and p37 leads to a change in localization of NOPP44/46.

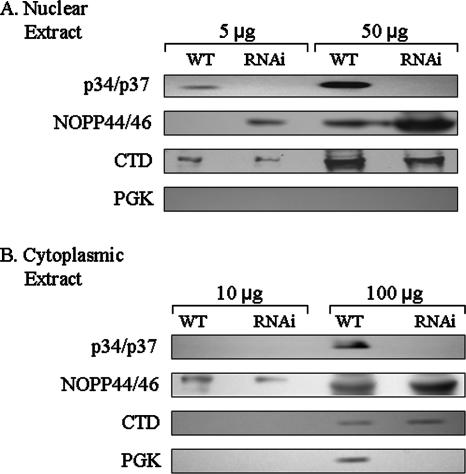

Using the protocol of Rout and Field (33), we isolated nuclei to analyze NOPP44/46 protein localization within T. brucei cells. This technique yields more highly purified nuclei than the technique utilized in conjunction with sucrose gradient sedimentation analyses, thus allowing for better evaluation of the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of NOPP44/46. The results in Fig. 6 are representative of three separate experiments. Analysis of phosphoglycerate kinase (a cytoplasmic marker) and RNA polymerase II large subunit (a nuclear marker) indicates that nuclear preparations obtained from both wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells yielded clearly distinct subcellular fractions (Fig. 6A and B, lower two panels). Although some nuclear contamination of cytoplasmic extracts may be present (Fig. 6B, third panel), the nuclear fraction is substantially free of cytoplasmic contamination (Fig. 6A, bottom panel). We first confirmed that p34 and p37 are no longer detectable in cell extracts upon induction of p34/p37 dsRNA expression (top panel). Using the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, we demonstrated a clear enrichment in NOPP44/46 abundance within the nuclear extracts, concomitant with loss of p34 and p37 expression (Fig. 6A, second panel, compare wild type to RNAi). This increase occurs even though overall protein levels of NOPP44/46 remain unaltered within these cells (Fig. 5), indicating that p34 and p37 do indeed affect NOPP44/46 protein cellular localization.

FIG. 6.

NOPP44/46 localization in p34/p37 RNAi cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared from wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi cells. With the amount of extract indicated, samples were separated using SDS-PAGE and processed for Western blot analysis. (A) Results from nuclear extracts; (B) results from cytoplasmic extracts. The presence of p34 and p37 proteins, NOPP44/46, phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK; a cytoplasmic marker), and the RNA polymerase II large subunit (CTD; a nuclear marker) were detected as indicated.

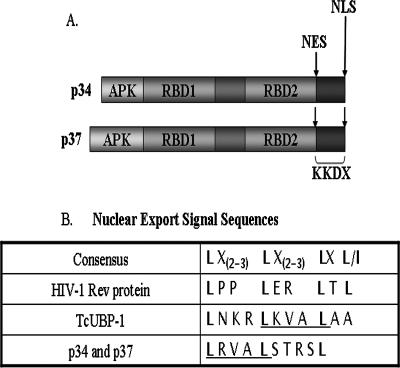

The p34 and p37 proteins associate with exportin 1.

p34 and p37 each contain several domains, including an N-terminal alanine, proline, lysine-rich domain (APK), two RBD, and a C-terminal lysine, lysine, glutamic acid, “X” repeat motif (Fig. 7A). The last 16 amino acids of each protein comprise a bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Fig. 7A), and these proteins were shown to be predominantly nuclear in our previous work (39). We next wanted to determine if p34 and p37 contain any additional motifs that may be involved in regulating the nuclear export of the NOPP44/46 proteins. Using the NetNES program website (24), we found that p34 and p37 each contain a leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES) (Fig. 7A and B). This type of NES is known to mediate the interaction of a subset of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins with the nuclear export factor exportin 1 (14). Figure 7B shows the p34 and p37 NES compared to the canonical sequence, which is based on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev protein (7). We also show the NES from TcUBP-1, a T. cruzi RNA binding protein (12), to demonstrate the similarities between these two kinetoplastid NES sequences.

FIG. 7.

Motif and sequence analysis of p34 and p37 proteins. (A) Motif maps of the p34 and p37 proteins, including locations of NLS and NES. APK, alanine, proline, lysine-rich domain; RBD, RNA binding domain; KKDX, lysine, lysine, aspartic acid, and “X” repeat motif. (B) Nuclear export signal sequences shown with the consensus sequence. Similar and identical residues between T. brucei p34 and p37 and T. cruzi UBP-1 are underlined. Spaces were introduced to allow for alignment of conserved leucine residues.

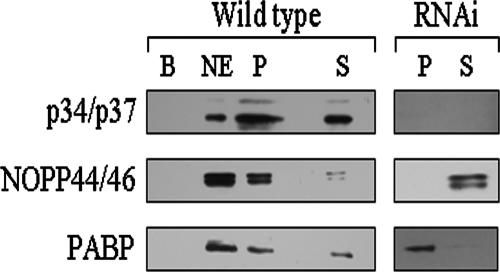

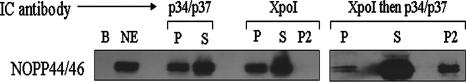

In order to determine whether p34 and p37 interact with exportin 1, IC experiments were performed. Wild-type nuclear extracts were incubated with anti-XpoI-cross-linked Dynabeads, and Western blot analysis was performed using anti-p34/p37 antiserum. The data shown are representative of five separate experiments. The results of these experiments show that p34 and p37 are present in the IC pellet fraction to the same extent that they are present in the nuclear extract (Fig. 8, left top panel, compare nuclear extract and pellet fractions), demonstrating an interaction of both proteins with exportin 1. Neither p34 nor p37 interacted with the beads alone (Fig. 8, left top panel). When these experiments were repeated using p34/p37 RNAi cells, no p34 or p37 was found in the IC pellet or supernatant fractions (Fig. 8, left top panel), as anticipated. These data demonstrate that p34 and p37 interact with exportin 1, suggesting they may play a role in regulating the cellular localization of additional RNA and/or proteins.

FIG. 8.

NOPP44/46 associate with exportin 1 through an interaction with p34/p37. Wild-type and RNAi cells were fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts. A 500-μg aliquot of nuclear extract was used for subsequent immune capture of exportin 1. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis to detect p34 and p37 (upper panel). Membranes were stripped and reprobed for detection of NOPP44/46 (middle panel). As a control, membranes were stripped again and reprobed for PABP (lower panel). B, IC beads-alone control; NE, 50 μg nuclear extract; P, IC pellet fraction; S, IC supernatant fraction.

The NOPP44/46 proteins associate with exportin 1.

To determine whether NOPP44/46 were associated with exportin 1, we stripped the above-described Western blots and probed for NOPP44/46. The IC experiment performed with wild-type nuclear extracts showed the presence of NOPP44/46 in the pellet fraction (Fig. 8, left middle panel), indicating that NOPP44/46 do associate with exportin 1. However, in the p34/p37 RNAi cells, there was no detectable NOPP44/46 in the IC pellet fraction (Fig. 8, right middle panel). These data indicate that the association of NOPP44/46 with exportin 1 is dependent on the presence of p34 and/or p37. To ensure that the loss of association between NOPP44/46 and exportin 1 in the absence of p34 and p37 was specific to these proteins, we stripped the Western blot and probed for PABP. In Trypanosoma brucei, PABP is present in both cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts (K. Prohaska, unpublished data), indicating that it is likely a shuttling protein similar to yeast PABP, whose nuclear export is facilitated by exportin 1 (4). Thus, we deduced that PABP could act as a positive control for these experiments. As shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 8, PABP is present in the IC pellet fractions in both wild-type and p34/p37 RNAi nuclear extracts (compare wild type to RNAi), indicating its localization is unaffected by the presence or absence of p34 and p37. Thus, the loss of the NOPP44/46-exportin 1 association was due specifically to the absence of p34 and/or p37.

p34, p37, NOPP44/46, and exportin 1 exist in a common complex.

Single immune capture experiments demonstrated that p34 and/or p37 is required for the association of NOPP44/46 with exportin 1. Thus, we wished to determine whether p34 and/or p37, NOPP44/46, and exportin 1 form a molecular complex. The results shown in Fig. 9 are representative of five separate experiments. We performed single IC experiments to capture p34 and p37 (Fig. 9, left panel, p34/p37 IC) and, in a separate experiment, exportin 1 (Fig. 9, left panel, XpoI IC). These experiments confirmed the interaction between NOPP44/46 and p34 and p37, and also between NOPP44/46 and exportin 1 (Fig. 9, compare IC-P lanes between p34/p34 IC and XpoI IC). Sequential immune capture experiments, capturing exportin 1 and then p34 and p37, demonstrated that a subset of nuclear NOPP44/46 are in complex with p34 and/or p37 and with exportin 1 simultaneously (Fig. 9, right panel). This may not represent the entire population of NOPP44/46 involved in this complex, as more protein was released from the beads upon a second elution (Fig. 9, right panel).

FIG. 9.

p34 and/or p37, exportin 1, and NOPP44/46 are involved in a common complex. Procyclic nuclear extracts were used to perform exportin 1 immune capture assays. The first capture was eluted using SDS, DTT, and β-mercaptoethanol. Eluate was renatured and used for subsequent immune capture of p34 and p37. B, IC beads-alone control; NE, 50 μg nuclear extract; P, IC pellet fraction; S, IC supernatant fraction; P2, IC second elution.

A large proportion of NOPP44/46 is present in the IC supernatant sample (Fig. 9, right panel), representing either free protein or protein involved in another complex(es). Thus, p34 and/or p37, NOPP44/46, and exportin 1 are part of a common complex which may also contain additional proteins and/or RNA.

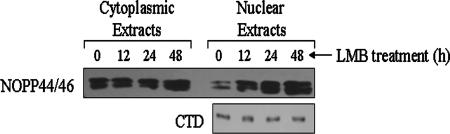

NOPP44/46 proteins accumulate in the nucleus upon treatment of wild-type procyclic cells with leptomycin B.

Since NOPP44/46 are associated with exportin 1 in a p34- and/or p37-dependent manner, we hypothesized that they are subsequently transported out of the nucleus. To determine whether this is the case, we treated wild-type cells with LMB, a specific inhibitor of the exportin 1 pathway. LMB acts to inhibit exportin 1-dependent nuclear export by irreversibly modifying a conserved cysteine residue required for the interaction with NES-containing cargoes (23). Cells were treated with LMB at a final concentration of 0.001 ng/cell, as previously described for T. brucei (38). Cells were left untreated (control) or treated for 12, 24, or 48 h, after which cells were fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts. Extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE for subsequent Western blot analysis of NOPP44/46. As shown in Fig. 10 (representative of four separate experiments), we detected a steady increase in nuclear NOPP44/46 protein abundance throughout the time course of the experiment (right panel), whereas cytoplasmic NOPP44/46 levels remained relatively constant (left panel). Using exposures from each experiment in the linear range, there was an average 5.5-fold ± 0.3-fold increase in nuclear NOPP44/46 protein levels after 48 h of treatment. These results correlate with those shown in the middle panels of Fig. 2, where there was an increase in nuclear NOPP44/46 proteins in the absence of p34 and p37. As a control, we used an antibody directed against the large subunit of RNA polymerase II (Fig. 10, bottom panel), since it does not contain a nuclear export signal. The levels of this protein remained steady throughout the time course of the experiment, demonstrating that the increase in nuclear NOPP44/46 abundance is specific to their interaction with exportin 1. Together, our results demonstrate that NOPP44/46 exit the nucleus through an exportin 1-dependent mechanism, which is mediated by their interaction with p34 and/or p37.

FIG. 10.

Localization of NOPP44/46 upon treatment of wild-type procyclic cells with leptomycin B. A total of 1.0 × 106 cells/reaction mixture were left untreated or treated with LMB for the indicated time points at a final concentration of 0.001 ng/cell. Cells were fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Western blot analyses were performed to detect NOPP44/46 (upper panel) and the large subunit of RNA polymerase II (CTD) (lower panel).

DISCUSSION

We have previously identified two nearly identical RNA binding proteins, p34 and p37, which are essential for Trypanosoma brucei survival (19, 40). These trypanosome-specific proteins (18) interact with NOPP44/46 (30), a family of trypanosome-specific nucleolar phosphoproteins (29), suggesting that this protein-protein interaction serves a unique function within T. brucei. In the experiments presented here, we knocked down the expression of both p34 and p37 proteins using RNA interference to further characterize their association with the NOPP44/46 proteins.

Results presented here indicate that loss of p34 and p37 proteins leads to the disruption of a cellular complex(es) that normally contains these proteins. In sucrose gradient analysis of RNAi cell nuclear extracts, an upward shift in the sedimentation profile of the NOPP44/46 proteins occurred (Fig. 1B, bottom panel), indicating that loss of p34 and p37 resulted in alterations within a complex(es) that contains both proteins.

Upon induction of p34/p37 dsRNA, an increase in nuclear NOPP44/46 protein levels occurred compared to wild type (Fig. 2, middle panels). A 12-fold increase in NOPP44/46 protein levels was observed upon loss of p34 and p37 (Fig. 6A, second panel), suggesting that p34 and p37 regulate NOPP44/46 expression. We detected no change in the abundance or stability of NOPP44/46 transcript in the RNAi cells (Fig. 3 and 4), indicating that p34 and p37 do not regulate NOPP44/46 transcript expression. Unexpectedly, when we examined the overall cellular protein levels of NOPP44/46, we found that they remained unchanged in p34/p37 RNAi versus wild-type cells (Fig. 5). Taken together with our cellular fractionation results (Fig. 2 and 6), this strongly suggests that p34 and p37 act to regulate NOPP44/46 cellular localization.

Previous studies using immunoelectron microscopy and immunofluorescence analyses have indicated that NOPP44/46 are localized to the nucleolus (10). However, this does not preclude the possibility that a small subset of these proteins rapidly shuttle out of the nucleolus/nucleus, since their cytoplasmic abundance may be below the level of detection with these methods. The NOPP44/46 proteins do not contain a nuclear localization or export signal sequence, although their amino-terminal unique (U) sequence has been shown to be required for nucleolar localization. This suggests that the cellular localization of NOPP44/46 may be dependent on other nuclear and/or nucleolar proteins.

In p34 and p37, the last nine residues of the second RBD comprise a putative NES sequence (Fig. 7A), which fits the consensus sequence found in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev protein (13). It is also very similar to the NES found in the T. cruzi RNA binding protein TcUBP-1 (Fig. 7B) (12), indicating a sequence conservation within trypanosomes. Figure 8 demonstrates that p34 and p37 interact with the nuclear export factor exportin 1. A variety of cellular components undergo exportin 1-dependent nuclear export. These include the large (60S) and small (40S) ribosomal subunits, many cellular proteins, several U snRNAs, all rRNAs, and a subset of mRNAs (7, 15, 20, 26, 36, 37). Exportin 1 has been identified in trypanosomes and is indicated as having a role in the nuclear export of spliced leader RNA in T. brucei as well as a subset of mRNA in T. cruzi (6, 38).

The p34 and p37 proteins appear to act as adapter proteins allowing for the export of the NOPP44/46 proteins out of the nucleus in an exportin 1-dependent manner. Examples of proteins and protein complexes that depend on adapter proteins for their association with exportin 1 and subsequent nuclear export include the mammalian 14-3-3 proteins and the yeast 60S ribosomal subunit (5, 20). The 60S ribosomal subunit is exported to the cytoplasm via the exportin 1 nuclear export pathway, which requires the nonribosomal adapter protein Nmd3p (20). Nmd3p acts to provide the nuclear export signal to mediate the association between the 60S ribosomal subunit and exportin 1. It is important to note that, in addition to Nmd3p, several other nonribosomal factors are required for nuclear export of the 60S ribosomal subunit, including Nop53p, Nug1p, and Nug2p (1, 35). This suggests that nuclear export may involve large complexes and that it is regulated by several different types of proteins. Thus, p34 and p37, possibly in concert with unidentified factors, may act in a similar manner to regulate NOPP44/46 cellular localization. This is further supported by the p34/p37 RNAi immune capture results, which demonstrated the loss of the NOPP44/46-exportin 1 association in the absence of p34 and p37 (Fig. 8, right middle panel). The accumulation of NOPP44/46 in the nucleus following LMB treatment (Fig. 10) further suggests that NOPP44/46 are exported from the nucleus via exportin 1. Together, these data suggest that p34 and p37 may function as a control mechanism to shuttle excess NOPP44/46 proteins out of the nucleus or, alternatively, they may serve to regulate the nuclear export of a larger complex containing the NOPP44/46 proteins.

We have previously established that p34 and p37 associate with 5S rRNA (31), a component of the 60S ribosomal subunit. Recent work from this laboratory using the same p34/p37 RNAi cells has demonstrated a dramatic decrease in the levels of 5S rRNA, in addition to disruption of a cellular complex(es) containing 5S rRNA (19). These results suggest an important role for p34 and p37 in stabilizing 5S rRNA. The loss of 5S rRNA in these cells leads to a significant decrease in protein synthesis efficiency, which appears to be the result of a defect in the assembly the 60S ribosomal subunits into the 80S complex (19). At this time, we do not know whether the disrupted complex(es) in the p34/p37 RNAi cells contains both NOPP44/46 and 5S rRNA or whether they are separate and distinct complexes. The Parsons laboratory has recently shown that NOPP44/46 are involved in the later stages of 60S ribosomal subunit biogenesis (21). Experiments utilizing NOPP44/46 RNAi cells have demonstrated aberrant processing of pre-60S rRNA, disruption of 60S assembly, and cell death (21). Incorporation of 5S rRNA is one of the final steps in the assembly pathway of the 60S ribosomal subunit (11). Thus, p34 and p37 may function to coordinate 5S rRNA incorporation into assembling pre-60S ribosomal subunits through an interaction with the NOPP44/46 proteins.

We do not currently know whether the interaction of p34 and p37 with 5S rRNA and the NOPP44/46 proteins reflects one common or two distinct roles for these proteins. Thus, these interactions could occur independently of one another. Overall, the results presented here indicate that the protein-protein interaction of p34 and p37 with NOPP44/46 plays an important role in NOPP44/46 protein cellular distribution, possibly in the context of a larger complex. Experiments are currently under way to more precisely define the components and function of this complex.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marilyn Parsons (Seattle Biomedical Research Institute) for the NOPP44/46 monoclonal antibody as well as antisera to T. brucei phosphoglycerate kinase. We also thank Vivian Bellofatto (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey) for polyclonal antiserum to the T. brucei RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain and Alberto Frasch (Instituto de Investigaciones Biotechnologicas) for the anti-XPOI antibody. We also thank David Campbell (UCLA) for the leptomycin B.

This work was supported by NIAID grant AI 41134 (to N.W. and W. T. Ruyechan) and NIH Predoctoral Training Grant T32AI07614 for the support of K.H. and K.P.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassler, J., P. Grandi, O. Gadal, T. LeBmann, E. Petfalski, D. Tollervey, J. Lechner, and E. Hurt. 2001. Identification of a 60S preribosomal particle that is closely linked to nuclear export. Mol. Cell 8:517-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, T., and K. Mackey. 1997. Analysis of RNA by northern and slot blot hybridization, p. 4.9.1-4.9.16. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 4.Brune, C., S. E. Munchel, N. Fischer, A. V. Podtelejnikov, and K. Weis. 2005. Yeast poly(A)-binding protein Pab1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and functions in mRNA export. RNA 11:517-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunet, A., F. Kanai, J. Stehn, J. Xu, D. Sarbassova, J. Frangioni, S. Dalal, J. DeCaprio, M. Greenberg, and M. Yaffe. 2002. 14-3-3 transits to the nucleus and participates in nucleocytoplasmic transport. J. Cell Biol. 156:817-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuevas, I. C., A. C. C. Frasch, and I. D'Orso. 2005. Insights into a CRM1-mediated RNA-nuclear export pathway in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 139:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen, B. R. 2003. Nuclear RNA export. J. Cell Sci. 116:587-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham, I. 1977. New culture medium for maintenance of tsetse tissues and growth of trypanosomatids. J. Protozool. 24:325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das, A., H. Li, T. Liu, and V. Bellofatto. 2006. Biochemical characterization of Trypanosoma brucei RNA polymerase II. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 150:201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das, A., G. C. Peterson, S. B. Kanner, U. Frevert, and M. Parsons. 1996. A major tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of Trypanosoma brucei is a nucleolar RNA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15675-15681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dechampesme, A. M., O. Koroleva, I. Leger-Silvestre, N. Gas, and S. Camier. 1999. Assembly of 5S ribosomal RNA is required at a specific step of the pre-rRNA processing pathway. J. Cell Biol. 145:1369-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Orso, I., and A. Frasch. 2001. TcUBP-1, a developmentally regulated U-rich RNA binding protein involved in selective mRNA destabilization in trypanosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:34801-34809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer, U., J. Huber, W. C. Boelens, I. W. Mattaj, and R. Luhrmann. 1995. The HIV-1 Rev activation domain is a nuclear export signal that accesses a nuclear export pathway used by specific cellular RNAs. Cell 82:475-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fornerod, M., M. Ohno, M. Yoshida, and I. W. Mattaj. 1997. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell 90:1051-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gadal, O., D. Strauss, J. Kessl, B. Trumpower, D. Tollervey, and E. Hurt. 2001. Nuclear export of 60S ribosomal subunits depends on Xpo1p and requires a nuclear export sequence-containing factor, Nmd3p, that associates with the large subunit protein Rpl10p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3405-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallagher, S. R. 1996. One-dimensional SDS gel electrophoresis of proteins, p.10.2.30. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 17.Gilboa, L., A. Nohe, T. Geissendorfer, W. Sebald, Y. Henis, and P. Knaus. 2000. Bone morphogenic protein receptor complexes: a new oligomerization mode for serine/threonine kinase receptors. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:1023-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomes, G. G., T. Urmenyi, E. Rondinelli, N. Williams, and R. Silva. 2004. TcRRMs and Tcp28 genes are intercalated and differentially expressed in Trypanosoma cruzi life cycle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 322:985-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hellman, K. M., M. Ciganda, S. Brown, J. Li, W. T. Ruyechan, and N. Williams. 2007. Two trypanosome-specific proteins are essential factors for 5S rRNA abundance and ribosomal assembly in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1766-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho, J. H., G. Kallstrom, and A. W. Johnson. 2000. Nmd3p is a Crm1p-dependent adapter protein for nuclear export of the large ribosomal subunit. J. Cell Biol. 151:1057-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen, B. C., D. L. Brekken, A. C. Randall, C. T. Kifer, and M. Parsons. 2005. Species specificity in ribosome biogenesis: a nonconserved phosphoprotein is required for formation of the large ribosomal subunit in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell 4:30-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy, P. G. E. 2004. Human African trypanosomiasis of the CNS: current issues and challenges. J. Clin. Investig. 113:496-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kudo, N., N. Matsumori, H. Taoka, D. Fujiwara, E. P. Schreiner, B. Wolff, M. Yoshida, and S. Horinouchi. 1999. Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9112-9117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.la Cour, T., L. Kiemer, A. Molgaard, R. Gupta, K. Skriver, and S. Brunak. 2004. Analysis and prediction of leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 17:526-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matovu, E., T. Seebeck, J. C. K. Enyaru, and R. Kaminsky. 2001. Drug resistance in Trypanosoma brucei spp., the causative agent of sleeping sickness in man and nagana in cattle. Microbes Infect. 3:763-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moy, T. I., and P. A. Silver. 2002. Requirements for the nuclear export of the small ribosomal subunit. J. Cell Sci. 115:2985-2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park, J. H., D. L. Brekken, A. C. Randall, and M. Parsons. 2002. Molecular cloning of Trypanosoma brucei CK2 catalytic subunits: the alpha isoform is nucleolar and phosphorylates the nucleolar protein Nopp44/46. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 119:97-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker, H. L., T. Hill, K. Alexander, N. B. Murphy, W. R. Fish, and M. Parsons. 1995. Three genes and two isozymes: gene conversion and the compartmentalization and expression of the phosphoglycerate kinases of Trypanosoma (Nannomonas) congolense. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 69:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons, M., J. A. Ledbetter, G. L. Schieven, A. E. Nel, and S. B. Kanner. 1994. Developmental regulation of pp44/46 tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins associated with tyrosine/serine kinase activity in T. brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 63:69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitula, J., J. Park, M. Parsons, W. T. Ruyechan, and N. Williams. 2002. Two families of RNA binding proteins from Trypanosoma brucei associate in a direct protein-protein interaction. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 122:81-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitula, J., W. T. Ruyechan, and N. Williams. 2002. Two novel RNA binding proteins from Trypanosoma brucei are associated with 5S rRNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290:569-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts, T. G., N. R. Sturm, B. K. Yee, M. C. Yu, T. Hartshorn, N. Agabian, and D. A. Campbell. 1998. Three small nucleolar RNAs identified from the spliced leader-associated RNA locus in kinetoplastid protozoans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4409-4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rout, M. P., and M. C. Field. 2001. Isolation and characterization of subnuclear compartments from Trypanosoma brucei: identification of a major repetitive nuclear lamina component. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38261-38271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seed, J. R. 2001. African trypanosomiasis research: 100 years of progress, but questions and problems still remain. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:434-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomson, E., and D. Tollervey. 2005. Nop53p is required for late 60S ribosomal subunit maturation and nuclear export in yeast. RNA 11:1215-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trotta, C. R., E. Lund, L. Kahan, A. W. Johnson, and J. E. Dahlberg. 2003. Coordinated nuclear export of 60S ribosomal subunits and NMD3 in vertebrates. EMBO J. 22:2841-2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tschochner, H., and E. Hurt. 2003. Pre-ribosomes on the road from the nucleolus to the cytoplasm. Trends Cell Biol. 13:255-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeiner, G. M., N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2003. Exportin 1 mediates nuclear export of the kinetoplastid spliced leader RNA. Eukaryot. Cell 2:222-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, J., W. Ruyechan, and N. Williams. 1998. Developmental regulation of two nuclear RNA binding proteins, p34 and p37, from Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 92:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, J., and N. Williams. 1997. Purification, cloning, and expression of two closely related Trypanosoma brucei nucleic acid binding proteins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 87:145-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]