Abstract

Trypanosomatid parasites contain an unusual form of mitochondrial DNA (kinetoplast DNA [kDNA]) consisting of a catenated network of several thousand minicircles and a smaller number of maxicircles. Many of the proteins involved in the replication and division of kDNA are likely to have no counterparts in other organisms and would not be identified by similarity to known replication proteins in other organisms. A new kDNA replication protein conserved in kinetoplastids has been identified based on the presence of posttranscriptional regulatory sequences associated with S-phase gene expression and predicted mitochondrial targeting. The Leishmania major protein P105 (LmP105) and Trypanosoma brucei protein P93 (TbP93) localize to antipodal sites flanking the kDNA disk, where several other replication proteins and nascent minicircles have been localized. Like some of these kDNA replication proteins, the LmP105 protein is only present at the antipodal sites during S phase. RNA interference (RNAi) of TbP93 expression resulted in a cessation of cell growth and the loss of kDNA. Nicked/gapped forms of minicircles, the products of minicircle replication, were preferentially lost from the population of free minicircles during RNAi, suggesting involvement of TbP93 in minicircle replication. This approach should allow the identification of other novel proteins involved in the duplication of kDNA.

Trypanosomatid protozoa contain an unusual form of mitochondrial DNA consisting of thousands of circular DNA molecules catenated into a single enormous network termed “kinetoplast DNA” (kDNA) (24). These parasites are responsible for human diseases such as African sleeping sickness, visceral and dermal leishmaniasis, and Chagas disease. The trypanosomatid protozoa are among the earliest diverging eukaryotic organisms (40). Each parasite cell has only a single mitochondrion, which contains a single kDNA network that is condensed into a disk-shaped structure. The kDNA network is composed of two types of circular DNA: thousands of minicircles and 20 to 30 maxicircles. These circular DNAs are topologically interlocked to form a single DNA network. Each minicircle is interlocked with an average of three neighboring minicircles (8). The maxicircles usually range from 20 to 40 kb in size and encode a set of genes involved in the respiratory chain and mitochondrial rRNAs. Most maxicircle-encoded transcripts require specific addition and deletion of uridine residues by a process termed “RNA editing” to form translatable mRNAs (41). Minicircles from different species range from 0.9 to 10 kb in size and encode guide RNAs required for RNA editing of maxicircle transcripts (24).

kDNA replication involves the duplication of all minicircles and maxicircles in the network and division of the double-size network into two daughter networks. Replication of the kDNA takes place during a distinct period of the cell cycle close to the nuclear S phase (9, 34, 44), unlike in higher eukaryotes, where mitochondrial DNA replicates throughout the cell cycle (5, 14, 42). Minicircles are released from the network by a topoisomerase II prior to replication in the kinetoflagellar zone (KFZ), a specialized region of the mitochondrial matrix between the kDNA disk and the flagellar basal body (12). The free minicircles initiate replication as theta structures by a mechanism proposed to involve the universal minicircle sequence-binding protein (UMSBP), primase, and replicative polymerases (17, 20, 33). An additional protein, p38, has been shown recently to bind to the minicircle replication origin and appears to be essential for initiation of replication (23). The progeny free minicircles are proposed to migrate from the KFZ to the antipodal sites flanking the kDNA disk, where later stages of minicircle replication are catalyzed by proteins including DNA polymerase β, structure-specific endonuclease 1, DNA ligase kβ, and topoisomerase II (13, 18, 28, 38). The newly replicated free minicircles are partially repaired by filling the gaps between Okazaki fragments and sealing nicks before reattaching to the kDNA network at the antipodal sites. However, a single nick or gap remains in the newly synthesized strand of each daughter minicircle until all minicircles have been replicated (3, 4, 31, 32, 36). When all minicircles have been replicated, the remaining nicks/gaps in the minicircles are sealed and the disk is then segregated into two daughter networks by unknown mechanisms. Maxicircles also replicate by a theta mechanism but do not detach from the network during replication (7). However, much less is known about the maxicircle replication mechanism and the proteins involved.

More than 30 proteins have been found to be involved in kDNA replication or maintenance (19, 22). However, the complexity of kDNA replication and the frequency of occurrence of genes required for kDNA maintenance identified in a partial screening of an RNA interference (RNAi) library suggest that at least 100 proteins are required to replicate and maintain kDNA (22). It is likely that many of these kinetoplastid proteins will be unrelated to known replication proteins in other eukaryotes. In earlier studies of kDNA replication genes in Crithidia fasciculata, we found that two or more copies of the consensus octamer (C/A)AUAGAA(G/A) are required in the 5′ and/or 3′ flanking regions of transcripts for S-phase expression of these genes (2, 6, 25, 35). Recently, Shlomai and coworkers (45) developed a computational tool to search the genome of Leishmania major and found that these posttranscriptional control elements identified S-phase-expressed genes in this kinetoplastid as well. We have screened this subset of L. major genes for predicted mitochondrial targeting as a means of identifying new kDNA replication proteins. We describe here a Leishmania major gene, LmP105, that encodes a protein that has a cell cycle-dependent localization to antipodal sites flanking the kinetoplast disk and its Trypanosoma brucei ortholog, TbP93, which we show to be an essential gene implicated in kinetoplast minicircle DNA replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of LmP105 and TbP93 genes and plasmid constructions.

To generate LmP105 (LmjF 25.1360) fusion protein with a C-terminal influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) tag in triplicate, the LmP105 coding region and 5′ flanking sequence was amplified by using Leishmania major genomic DNA as template with the primers 5′-TAGAAGCTTGCAAGGGTGAGGACAGTGGAGGA-3′ and 5′-AGAGATATCAAGATCATCGCCCCCACCAGC-3′. The PCR product was digested with HindIII and EcoRV and ligated into the corresponding sites of plasmid pMA1 (2).

To generate a TbP93 fusion protein with a C-terminal influenza virus HA tag in triplicate, the TbP93 coding region was amplified by using T. brucei 29-13 genomic DNA as a template with the primers 5′-TCGAAGCTTATGCCGGGCTACCCCAC-3′ and 5′-AGCTAGCAAGAATCAGAAAGTAATCCTCCTGTG-3′. The PCR product was digested with HindIII and NheI and ligated to the corresponding compatible sites of HindIII- and XbaI-digested expression vector pJH54, a derivative of pLEW 100 (43) that has had the luciferase gene replaced by three copies of the HA tag.

For TbP93 (Tb 927.3.1180) RNAi, a 1,000-bp fragment of TbP93 coding region was amplified by using T. brucei 29-13 genomic DNA as the template with the primers 5′-GAAAAGCTTACTGGCCGTTGCTCTCG-3′ and 5′-CGTTCTAGAGCTGAACGAGCTACAACAGC-3′. The PCR product was digested with HindIII/XbaI and inserted between the opposing T7 promoters in the inducible RNAi vector P2T7 (21). A BLAST search of the T. brucei genome with this fragment showed no significant sequence identity elsewhere in the genome.

Leishmania tarentolae and Trypanosoma brucei growth and transfection.

L. tarentolae was cultured at 28°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Becton, Dickinson and Co.) containing 10 μg/ml hemin (Sigma Co.). Transfection was carried out as follows. Cells were washed twice in ice-cold BHI medium without hemin and resuspended at a density of 2.5 × 108 cells/ml. Ten micrograms of plasmid DNA was mixed with 0.4 ml of cells and electroporated by six pulses at 900 V with a 300-μs pulse length and 200-ms interval between pulses in 2-mm electroporation cuvettes in a BTX ECM830 square-wave electroporator. Cells were allowed to recover for 4 h in 10 ml BHI medium without hemin and then put under drug selection on agar plates (37 mg/ml BHI, 800 μg/ml folic acid [Sigma Co.], 8 mg/ml Bacto agar [Becton, Dickinson and Co.], 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum [Invitrogen Co.], 20 μg/ml hemin, 100 μg/ml hygromycin [Mideatech, Inc.]).

T. brucei strain 29-13 (43) was grown in SM medium (10) with 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen Co.), 32 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen Co.), and 50 μg/ml hygromycin at 28°C. Transfection was carried out as described previously (15). Cells were washed in electroporation buffer (120 mM KCl, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 9.2 mM K2HPO4, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM EDTA, 4.75 mM MgCl2, 69 mM sucrose, pH 7.6) and resuspended at 5 × 107 cells/ml. Fifteen micrograms of linearized plasmid DNA was mixed with 450 μl of cells and electroporated by five pulses at 1,700 V with a 100-μs pulse length and 200-ms interval between pulses in 4-mm electroporation cuvettes in a BTX ECM830 square wave electroporator. Cells were allowed to recover overnight in 10 ml of medium and then put under drug selection (2.5 μg/ml of phleomycin D1 [Invitrogen, Inc.]) the following day. Clonal cell lines were obtained by limited dilution in 50% conditioned medium and incubated at 28°C.

Protein immunolocalization.

Immunofluorescent localization of HA-tagged fusion protein was performed as described previously (38). Briefly, cells at 4 × 107 per ml were harvested, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 6.5 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4), spotted onto poly-l-lysine-coated slides, and allowed to adhere for 30 min in a humid chamber. The cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. Fixation was stopped by two 5-min washes in 0.1 M glycine in PBS, followed by incubation for 10 min in 0.025% Triton X-100 in PBS. The slides were kept in methanol at −20°C overnight, rehydrated by washing three times in PBS, and then blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 20% goat serum in PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). The slides were then incubated at room temperature overnight with a mixture of anti-HA monoclonal antibody HA.11 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Covance) at a 1:100 dilution, washed three times in PBST for 5 min each, and mounted in SlowFade Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Invitrogen Co.). T. brucei cells undergoing RNAi were prepared in the same way, incubated with YL1/2 (Chemicon; rat monoclonal antibodies against Saccharomyces cerevisiae tyrosinated α-tubulin at a 1:400 dilution), washed three times in PBS, and stained with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary goat antibodies (Molecular Probes) to stain basal bodies. Cells were imaged using a Zeiss Axioskop II compound microscope with a 63× Plan-neofluor oil immersion objective lens. Images were captured using a Zeiss Axiocam digital camera and Zeiss Axiovision 3.0 software. Red, blue, and green images of the same field were captured independently and merged using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 on a MacIntosh computer running OSX v10.4.9. Contrast and brightness were adjusted in Photoshop for each image.

RNAi, RNA purification, and Northern blotting.

Cloned T. brucei cells stably transfected with NotI-cleaved TbP93 RNAi vector were induced for RNAi by the addition of tetracycline (1 μg/ml). Aliquots of the culture were removed every 24 h and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. Fixation was stopped by two 5-min washes in 0.1 M glycine in PBS, followed by incubation for 10 min in 0.025% Triton X-100 in PBS. The slides were kept in methanol at −20°C overnight and rehydrated by washing three times in PBS. The cells were mounted in SlowFade Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen Co.) containing DAPI and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy for DNA phenotype. More than 150 cells were counted for each time point.

For Northern blots, cloned cells induced for RNAi by the addition of 1 μg/ml tetracycline for 40 h were collected and total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). RNA from 5 × 106 cells was loaded per lane, fractionated on a 1.2% agarose gel containing 7% formaldehyde, and analyzed by standard Northern blotting using a 32P-labeled probe made by random priming of the 1,000-bp fragment used for RNAi. A BLAST search of the genome did not detect additional sequences that might give rise to an off-target effect.

Leishmania tarentolae synchronization and LtP105 expression.

Leishmania tarentolae cells were synchronized by hydroxyurea treatment (34, 37). Cells were grown to late log phase (∼108 cells/ml) at 28°C in BHI medium supplemented with 10 μg hemin/ml and 100 μg streptomycin sulfate/ml prior to the addition of hydroxyurea to 200 μg/ml for 6 h. Cultures expressing the epitope-tagged Lm105 protein also contained 40 μg hygromycin/ml. Growth was continued at 28°C in fresh medium lacking hydroxyurea, and samples were removed every 30 min to determine the cell number and the number of dividing cells. Analysis of L. tarentolae P105 gene (LtP105) expression during the cell cycle was performed by Northern blotting of RNA isolated from samples (5 × 107 cells) taken at 30-min intervals from a synchronous culture of L. tarentolae. RNA isolation and blotting were performed as described above. DNA probes were amplified from genomic DNA using the primers 5′-CGCACCAGCAGCTCGACGCCG-3′ and 5′-GGTAGGCTCCAGCACATCTTGCCG-3′ for P105 and 5′-CTATCTGCATCCACATCGGCCAGGC-3′ and 5′-GCCGTAGTCCACAGACAGGCGCTCC-3′ for α-tubulin. The resulting PCR products (275 and 476 bp, respectively) were labeled with 32P by random priming for probing the Northern blot.

Western blots.

L. tarentolae cells (2 × 107) stably expressing HA-tagged LmP105 fusion protein were harvested at 12,000 × g for 5 min. The cell pellets were washed three times with 1 ml PBS buffer, resuspended in 50 μl PBS, mixed with 50 μl 2× sample loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 16% glycerol, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.025% bromphenol blue, pH 6.8), and boiled at 100°C for 5 min. Total lysates of 2 × 106 cells were separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membrane (Perkin-Elmer) with transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 20% methanol, 0.2 M glycine) at 100 V for 1 h. The membrane was incubated in Tris-buffered saline-Tween (TBST) buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8.0) for 5 min. The membrane was blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk and 5% (vol/vol) goat serum in TBST for 1 h, and then incubated with anti-HA monoclonal antibody 12CA5 (Abcam, Inc.) in blocking buffer at a 1:1,000 dilution with gentle rocking for 1 h. After three washes in TBST for 5 min each, HA-tagged fusion protein bands were visualized using peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Sigma) as secondary antibodies in blocking buffer at a 1:8,000 dilution and the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent system (Pierce).

Isolation of total DNA from RNAi-induced cells and Southern blots.

For total DNA extraction, cloned T. brucei 29-13 cells stably transfected with the P93 RNAi vector were induced by the addition of 1 μg/ml tetracycline and sampled every 48 h. Cells were harvested, washed once with NET-100 (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 100 mM EDTA) and resuspended in NET-100 at a density of 2 × 108 cells/ml. Cells were lysed in 0.5% SDS containing 0.2 mg/ml proteinase K at 56°C for 4 h and then treated with 0.1 mg/ml RNase A at 37°C for 15 min. After extraction with 1:1 phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitation, DNA was suspended in Tris-EDTA buffer. Analysis of free minicircle replication intermediates was performed by gel electrophoresis of total DNA samples and Southern blotting as described previously (23). The minicircle probe was amplified from plasmid pJN6 (31). pJN6 has the Trypanosoma equiperdum minicircle sequence, which has approximately 100 bp of sequence found in all T. brucei minicircle DNAs. The same amount of total DNA was digested with HindIII and XbaI for a loading control and analyzed by electrophoresis on a separate gel and Southern blotting. The trypanosome hexose transporter probe (used as a loading control) was amplified from total DNA with primers 5′-ATGACTGAGCGTCGTG-3′ and 5′-TTAGTTCCGCGGAGATG-3′.

RESULTS

Identification of a putative kDNA replication/maintenance gene.

A computational search of the L. major genome database identified a set of S-phase-expressed genes based on the presence of two or more sequences related to the octamer consensus (C/A)ATAGAA(A/G) in 5′ and/or 3′ flanking regions (45). We have searched this subset of genes using Mitoprot II software to identify genes that have a high probability of being mitochondrial. A gene, LmP105 (LmjF25.1360), identified in this search has an open reading frame encoding a protein of 965 amino acids. LmP105 has two putative posttranscriptional control elements, CATAGAA and CATAGAG, in the 5′ flanking region within 400 nucleotides from the open reading frame. We have not yet mapped the LmP105 splice acceptor site to determine whether these sequences lie within the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR); however, essential control sequences have been found 5′ of the splice acceptor site in earlier studies in C. fasciculata (2). Mitoprot II predicts mitochondrial import of the protein with a probability of 0.98. The protein is highly conserved in kinetoplastids, as shown in Fig. 1, but has no significant similarity to genes of other organisms nor does it have any motifs that would give a clue as to its function.

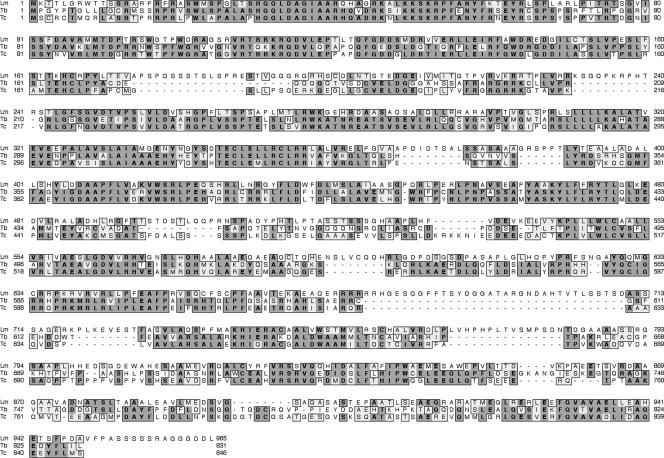

FIG. 1.

Clustal alignment of predicted amino acid sequences of kinetoplastid genes related to LmP105. Identical amino acids are in boxes with dark shading. Similar amino acids are indicated by light shading. Lm, Leishmania major, CAJ05244.1; Tb, Trypanosoma brucei, XP_843712; Tc, Trypanosoma cruzi, XP_814115.1.

Kinetoplast localization of LmP105.

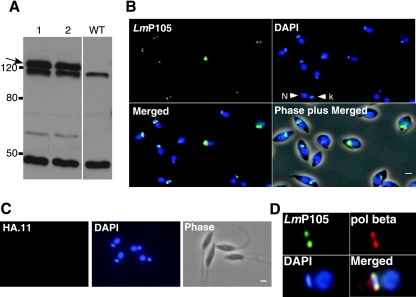

To determine the intracellular localization of LmP105, the coding sequence of LmP105, along with putative posttranscriptional control elements in the 5′ flanking sequence, was cloned and expressed with three copies of an HA epitope tag in Leishmania tarentolae (Fig. 2A). The tagged protein is predicted to have a molecular mass of 109 kDa but migrates on an SDS gel at a rate corresponding to a molecular mass of approximately 130 kDa, suggesting possible posttranslational modification of the protein. Figure 2B shows the immunolocalization of epitope-tagged LmP105 to antipodal sites flanking the kinetoplast disk. Although not all cells show localization of the LmP105 protein, immunostaining of untransfected cells only shows background staining throughout the cell and never showed staining of the kinetoplast (Fig. 2C). Coimunolocalization with DNA polymerase β was also performed to further confirm the intracellular localization of LmP105. DNA polymerase β localized to antipodal sites of the kDNA disk, as previously reported for C. fasciculata (18). The results in Fig. 2D show that LmP105 colocalizes with the polymerase β at the antipodal sites. Since many cells in an exponential culture do not show localization of LmP105, we suspected that the protein may have a cell cycle-dependent localization like that of several C. fasciculata DNA replication proteins, including topoisomerase II, polymerase β, ligase kα, SSE1, and UMSBP (1, 13, 18, 39).

FIG. 2.

Expression and localization of epitope-tagged LmP105. (A) Western blot of two cloned L. tarentolae strains expressing HA-tagged LmP105 (indicated by an arrow). The two additional major bands are due to cross-reacting proteins and are present in untransfected cells (wild type [WT]). (B and C) Immunostaining of L. tarentolae expressing HA-tagged LmP105 (B) and untransfected cells (C) using monoclonal antibody HA.11 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. DNA is stained with DAPI. (D) Colocalization of epitope-tagged LmP105 and DNA polymerase β (pol beta). Cloned cells expressing HA-tagged LmP105 were immunolocalized using anti-HA monoclonal antibody HA.11 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 to detect LmP105. Polymerase β was detected using rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the C. fasciculata polymerase β and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568. DNA is stained with DAPI. Scale bars, 2 μm.

Cell cycle dependence of LmP105 kinetoplast localization.

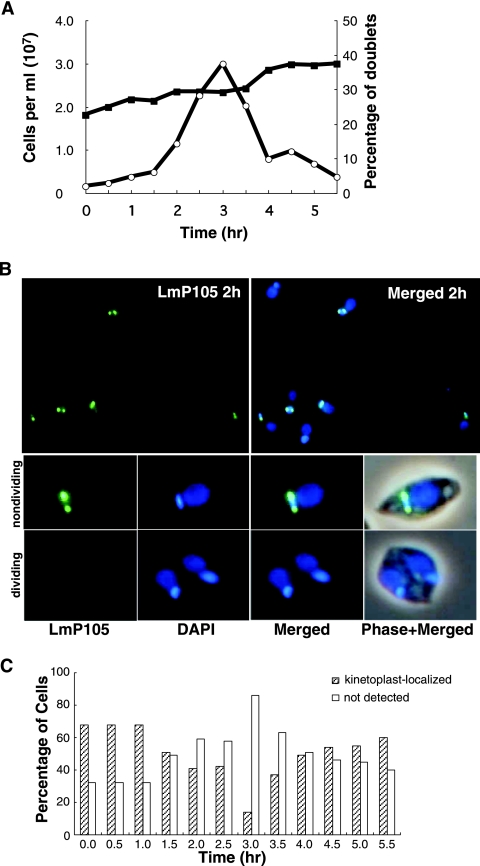

L. tarentolae cells expressing epitope-tagged LmP105 were synchronized by release from a hydroxyurea block in order to investigate LmP105 localization during the cell cycle (Fig. 3A). The lack of a complete doubling of the cell number by 5.5 h in the synchronized culture likely reflects the presence of cells initially that were unable to recover from the hydroxyurea treatment. It was noted earlier that hydroxyurea is selectively lethal to L. tarentolae cells in S phase (37), and these cells would contribute to the total cell count. Cells were scored for the presence of dividing cells containing two nuclei (doublets) as an indicator of cell cycle position. LmP105 was immunolocalized in cells harvested at 30-min intervals. Figure 3B shows an absence of kinetoplast localization in dividing cells with two nuclei. The lower panels of Fig. 3B show typical images of dividing and nondividing cells. Figure 3C shows the frequency of kinetoplast localization of LmP105 during the cell cycle. The frequency of kinetoplast localization of LmP105 was at a relative maximum from 0 to 1 h after release from the hydroxyurea block, a time corresponding to the initial S phase upon release from the block, and was at a minimum at 3 h, which corresponds approximately to G2/M. Cells undergoing division were never observed to show kinetoplast localization of LmP105.

FIG. 3.

Localization of epitope-tagged LmP105 varies during the cell cycle. Leishmania tarentolae cells expressing HA-tagged LmP105 were collected at 30-min intervals from a hydroxyurea-synchronized culture. (A) Cell number and percentage of doublets (cells containing two nuclei) during the cell cycle. (B) Immunolocalization of HA-tagged LmP105 at 2 h after release from a hydroxyurea block. Lower panels show typical dividing and nondividing cells. (C) Percentage of cells having LmP105 kinetoplast localization during the cell cycle as determined by microscopic analysis of DAPI-stained cells (>150 randomly selected cells counted each 30 min).

S-phase expression of the LtP105 transcript in synchronized L. tarentolae.

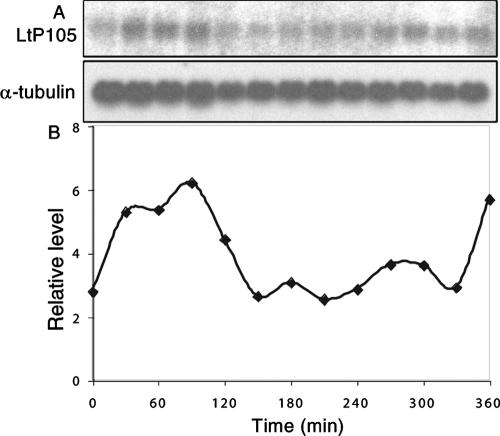

The possible S-phase expression of LtP105 was investigated by Northern blotting of RNA isolated from a synchronous culture at 30-min intervals after removal of the hydroxyurea block. As shown in the autoradiogram of the blotted RNA (Fig. 4A) and in the quantitation of the phosphorimage (Fig. 4B), the LtP105 levels cycle in the same manner as the cyclic localization of the LmP105 protein in L. tarentolae cells.

FIG. 4.

S-phase expression of LtP105 in synchronized L. tarentolae cells. (A) RNA samples (5 mg) isolated at 30-min intervals were analyzed by Northern blotting using probes for LtP105 and α-tubulin. (B) PhosphorImager quantitation of the Northern blot using α-tubulin to normalize for uneven loading.

Kinetoplast localization of TbP93 and RNAi.

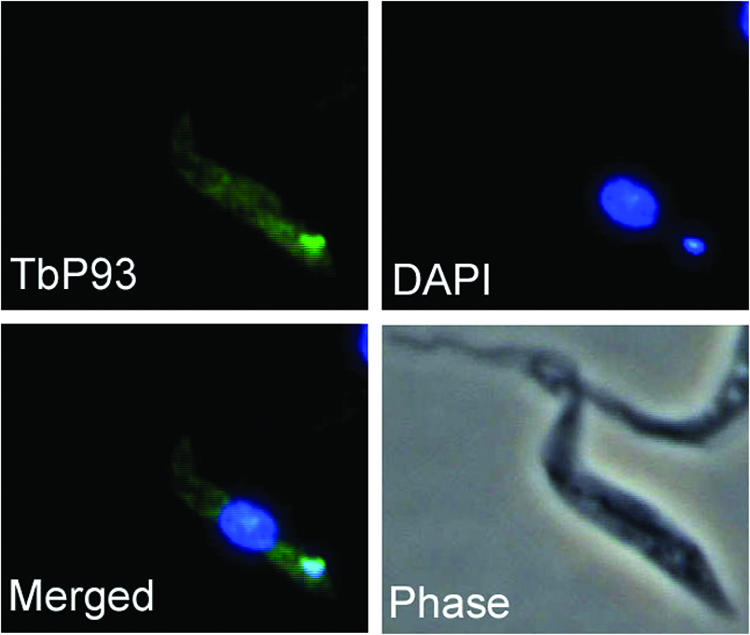

TbP93, the ortholog of LmP105 in T. brucei, shares 46% identity with LmP105 at the amino acid sequence level. To further characterize the role of TbP93/LmP105 in kinetoplast DNA replication/maintenance, the TbP93 coding sequence was cloned and inserted into a tetracycline-inducible expression vector with three copies of the influenza virus HA epitope tag and electroporated into T. brucei 29-13 cells. Immunolocalization of the epitope-tagged protein shows localization of the protein to the kinetoplast (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Kinetoplast localization of TbP93. Shown is immunolocalization of Trypanosoma brucei expressing HA-tagged TbP93 by monoclonal antibody HA.11 conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488.

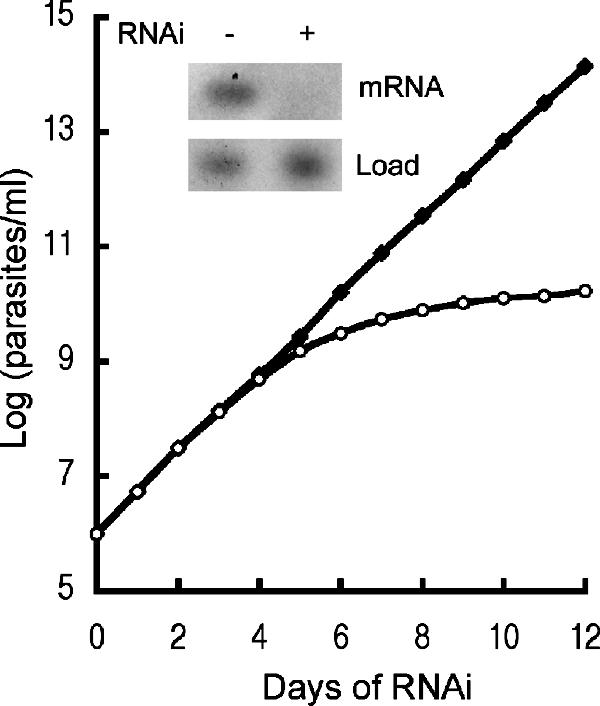

To address the function of TbP93, the coding sequence was cloned into the tetracycline-inducible RNAi vector P2T7 and electroporated into T. brucei 29-13 cells. Figure 6 shows the growth curve and Northern blot analysis of a typical RNAi clone. Cells grew normally in the absence of tetracycline, whereas after 5 days of tetracycline treatment to induce RNAi, cell growth was arrested. A Northern blot of the TbP93 transcript shows a disappearance by 40 h after the addition of tetracycline.

FIG. 6.

RNAi of TbP93. Shown is cell growth in an uninduced culture (−) or a culture induced (+) for RNAi by addition of 1 μg/ml tetracycline. The cell density (parasites/ml × dilution factor) is plotted against days of growth in the presence of tetracycline. The Northern blot (inset) shows the effect of RNAi (40 h) on the TbP93 mRNA level. RNase HIIC served as a loading control. Uninduced, solid squares; induced, open circles.

Shrinkage and loss of kDNA by TbP93 RNAi.

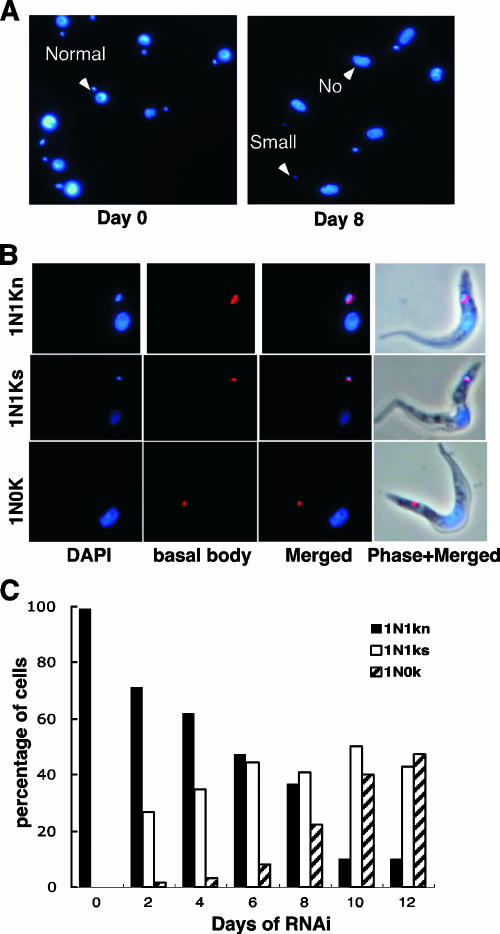

To observe both the nucleus and kDNA during RNAi induction, cells were removed from the culture every 48 h after tetracycline addition and stained with DAPI. RNAi of TbP93 resulted in a shrinkage and loss of kDNA. T. brucei cells had a normal-size kDNA prior to addition of tetracycline (Fig. 7A). After 8 days of RNAi induction, many cells showed a shrinkage or loss of kDNA. The typical cell phenotypes were categorized into three groups: the normal group, which included one nucleus and one normal-size kinetoplast; the small group, which included one nucleus and one small kinetoplast; and the “no” group, which included one nucleus and no kinetoplast. Figure 7B shows typical examples of these three types in cells stained with DAPI and with basal body antibodies. The percentage of each phenotype is shown in Fig. 7C. The percentage of cells with normal-size kDNA decreased during RNAi, and the percentage of cells with small or no kDNA increased during RNAi. The absence of kDNA was judged based on a lack of detectable DAPI fluorescence adjacent to the basal body. However, the possibility of a kDNA remnant too small to be detected cannot be excluded.

FIG. 7.

Shrinkage and loss of kDNA during RNAi. (A) Cells at 0 or 8 days in the presence of tetracycline were fixed and stained with DAPI and categorized as follows: normal, cells with a nucleus and kDNA; small, cells with a nucleus and tiny kDNA; no, cells with a nucleus but no kDNA. (B) Examples of three categories of T. brucei cells during RNAi. Basal bodies are detected using monoclonal antibody YL1/2. (C) Kinetics of kDNA loss during RNAi as determined by visual analysis (>150 randomly selected cells analyzed each day). Kinetoplast sizes: 1N1k, normal size; 1N1ks, small; 1N0k, no kinetoplast detected.

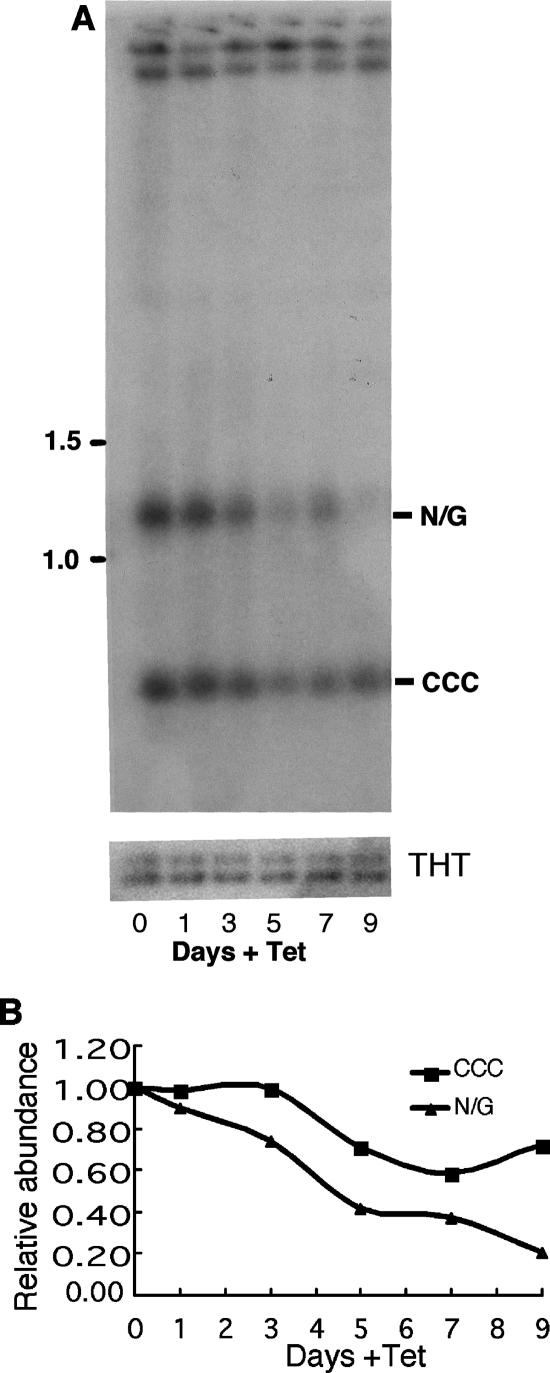

Effect of TbP93 RNAi on free minicircle replication intermediates.

The shrinkage and loss of kDNA during RNAi suggest involvement of TbP93 in kDNA replication. Since minicircle replication occurs free of the kDNA network, we have therefore examined the population of free minicircles during RNAi by Southern blotting of total DNA using a minicircle probe. Prior to RNAi (day 0) there are similar levels of covalently closed (nonreplicating) and nicked/gapped free minicircles. The latter species, the products of replication, decreases during RNAi in parallel with the shrinkage and loss of kDNA (Fig. 8). The upper bands on the Southern blot are due to kDNA and to nonspecific hybridization to chromosomal DNA. The abundance of free covalently closed minicircles also declines during RNAi but less so than that of the nicked and gapped free minicircles. The preferential loss of nicked/gapped minicircles, the products of minicircle replication, during RNAi implies a role for TbP93 in minicircle replication.

FIG. 8.

Effect of TbP93 RNAi on free minicircle replication intermediates. (A) Total cellular DNA (2 × 106 cells/lane) was analyzed by Southern blotting. The positions of molecular size markers (in kilobases) are shown to the left of the gels. (B) Quantitation of the levels of covalently closed (CCC) and nicked/gapped (N/G) free minicircles by phosphorimaging of the gel shown in panel A. Levels were normalized relative to the loading controls (equal amounts of total DNA digested with HindIII and XbaI and run under identical conditions).

DISCUSSION

We have shown in a series of earlier studies that transcripts of several genes involved in DNA replication in Crithidia fasciculata vary during the cell cycle, with maximal levels during S phase (2, 6, 16, 25-27, 29, 30, 34, 35). Furthermore, octamer consensus sequences (C/A)ATAGAA(A/G) present in flanking sequences of these genes were found to be essential for S-phase expression of these transcripts. A computational search of the Leishmania major genome database for similar posttranscriptional control sequences identified 132 genes, of which one-third encode known DNA metabolism genes and the remaining two-thirds are not annotated (45). A test of seven of the latter genes showed that in each case their transcripts showed S-phase expression. In a further screen of the unannotated set of genes for a high probability of mitochondrial import, we have identified LmP105 and shown here that both LmP105 and its T. brucei ortholog, TbP93, are indeed mitochondrial and are associated with antipodal sites flanking the kDNA. Although we have not yet examined the possible S-phase expression of Tb93, we note that two CATAGAC sequences are contained within 400 nucleotides of the stop codon, one within the coding sequence and one in the 3′ flanking sequence (unpublished).

The LmP105 protein colocalized with the mitochondrial DNA polymerase β at antipodal sites flanking the kDNA disk, and its localization there varied throughout the cell cycle, with maximum kinetoplast localization during the S phase, similar to that observed in C. fasciculata for DNA polymerase β, topoisomerase II, DNA ligase kα, and structure-specific endonuclease 1 (13, 18, 39). Expression of the LtP105 transcript also showed S-phase expression and possibly accounts for variation in localization of the protein throughout the cell cycle. The absence of HA-tagged LmP105 fluorescence in dividing cells is similar to that observed in C. fasciculata for polymerase β (18) and structure-specific endonuclease 1 (13). Since the absence of a fluorescence signal at the antipodal sites in dividing cells is a common feature of at least three proteins found there, there may be a common, but yet unknown, basis for the disappearance of the signal during cell division.

To address the function of this kinetoplast protein, we turned to the T. brucei ortholog TbP93 to take advantage of the use of RNAi to knock down expression of the gene. TbP93 was found to be essential for cell growth and for maintenance of the kDNA. During RNAi, the kDNA became progressively smaller and was lost in a large fraction of the cells. Further analysis of free minicircles showed a fivefold loss by day 9 of RNAi of the relative abundance of nicked/gapped minicircles, the products of minicircle replication. Taken together, these results suggest that LmP105/TbP93 has a direct role in kDNA replication. In the absence of a known motif in LmP105/TbP93, further characterization at a biochemical level will be required to address the function of these genes' proteins.

If LmP105 and TbP93 are directly involved in minicircle replication, it is surprising that they localize to the antipodal sites of the kDNA disk rather than to the KFZ, where minicircle replication appears to take place. The antipodal sites have been identified in earlier studies as sites where at least partial repair of nicks/gaps in minicircles takes place after the nascent minicircles have been reattached to the kDNA network. Recent studies suggest that the antipodal sites are more complex than previously thought and may contain subdomains. For example, T. brucei ligase kβ and topoisomerase II do not precisely colocalize at the antipodal sites (11). p38, a recently described protein that can bind to the minicircle replication origin and which has been implicated in early minicircle replication, also localizes to the antipodal sites of the kDNA disk (23). The puzzling localization of LmP105 and TbP93 and that of p38 suggest that the role of the antipodal sites may be less restricted than previously thought.

Over 30 proteins implicated in kDNA replication or maintenance have been identified (22). The highly unusual structure of kDNA and its complex replication and maintenance mechanism may require a large number of replication proteins, many of which are possibly unique to kinetoplastids. An RNAi library-based screen has been reported to identify genes for kDNA replication and maintenance (22). It is estimated that over 100 genes may be involved in kDNA replication and maintenance. Here we demonstrate another approach based on a bioinformatics screen. By combining the search for posttranscriptional control elements (C/A)ATAGAA(A/G) for S-phase gene expression (45) and the prediction of mitochondrial targeting, a new gene involved in kDNA replication was identified. Our work shows this is an alternative means to identify kinetoplast replication genes that may not contain a known DNA replication-related motif.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Shlomai for providing us with an unpublished manuscript. We thank George Cross for T. brucei 29-13 cells, Paul Englund for plasmid pJN6 and oligonucleotides for amplification of maxicircle and chromosomal fragments, Larry Simpson for L. tarentolae cells, Steve Beverley for L. major cells, and Kent Hill for plasmid P2T7 and for use of his phase-contrast microscope.

This research was supported by NIH grant GM53254.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu-Elneel, K., D. R. Robinson, M. E. Drew, P. T. Englund, and J. Shlomai. 2001. Intramitochondrial localization of universal minicircle sequence-binding protein, a trypanosomatid protein that binds kinetoplast minicircle replication origins. J. Cell Biol. 153:725-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avliyakulov, N. K., J. C. Hines, and D. S. Ray. 2003. Sequence elements in both the intergenic space and the 3′ untranslated region of the Crithidia fasciculata KAP3 gene are required for cell cycle regulation of KAP3 mRNA. Eukaryot. Cell 2:671-677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkenmeyer, L., H. Sugisaki, and D. S. Ray. 1987. Structural characterization of site-specific discontinuities associated with replication origins of minicircle DNA from Crithidia fasciculata. J. Biol. Chem. 262:2384-2392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birkenmeyer, L., H. Sugisaki, and D. S. Ray. 1985. The majority of minicircle DNA in Crithidia fasciculata strain CF-Cl is of a single class with nearly homogeneous DNA sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:7101-7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogenhagen, D., and D. A. Clayton. 1977. Mouse L cell mitochondrial DNA molecules are selected randomly for replication throughout the cell cycle. Cell 11:719-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, L. M., and D. S. Ray. 1997. Cell cycle regulation of RPA1 transcript levels in the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3281-3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter, L. R., and P. T. Englund. 1995. Kinetoplast maxicircle DNA replication in Crithidia fasciculata and Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:6794-6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, J., C. A. Rauch, J. H. White, P. T. Englund, and N. R. Cozzarelli. 1995. The topology of the kinetoplast DNA network. Cell 80:61-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosgrove, W. B., and M. J. Skeen. 1970. The cell cycle in Crithidia fasciculata. Temporal relationships between synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid in the nucleus and in the kinetoplast. J. Protozool. 17:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham, I. 1977. New culture medium for maintenance of tsetse tissues and growth of trypanosomatids. J. Protozool. 24:325-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downey, N., J. C. Hines, K. M. Sinha, and D. S. Ray. 2005. Mitochondrial DNA ligases of Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell 4:765-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drew, M. E., and P. T. Englund. 2001. Intramitochondrial location and dynamics of Crithidia fasciculata kinetoplast minicircle replication intermediates. J. Cell Biol. 153:735-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel, M. L., and D. S. Ray. 1999. The kinetoplast structure-specific endonuclease I is related to the 5′ exo/endonuclease domain of bacterial DNA polymerase I and colocalizes with the kinetoplast topoisomerase II and DNA polymerase beta during replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8455-8460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guttes, E. W., P. C. Hanawalt, and S. Guttes. 1967. Mitochondrial DNA synthesis and the mitotic cycle in Physarum polycephalum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 142:181-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill, K. L., N. R. Hutchings, D. G. Russell, and J. E. Donelson. 1999. A novel protein targeting domain directs proteins to the anterior cytoplasmic face of the flagellar pocket in African trypanosomes. J. Cell Sci. 112:3091-3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hines, J. C., and D. S. Ray. 1997. Periodic synthesis of kinetoplast DNA topoisomerase II during the cell cycle. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 88:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, C. E., and P. T. Englund. 1999. A refined localization of the mitochondrial DNA primase in Crithidia fasciculata. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 102:205-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, C. E., and P. T. Englund. 1998. Changes in organization of Crithidia fasciculata kinetoplast DNA replication proteins during the cell cycle. J. Cell Biol. 143:911-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klingbeil, M. M., M. E. Drew, Y. Liu, J. C. Morris, S. A. Motyka, T. T. Saxowsky, Z. Wang, and P. T. Englund. 2001. Unlocking the secrets of trypanosome kinetoplast DNA network replication. Protist 152:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klingbeil, M. M., S. A. Motyka, and P. T. Englund. 2002. Multiple mitochondrial DNA polymerases in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell 10:175-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaCount, D. J., S. Bruse, K. L. Hill, and J. E. Donelson. 2000. Double-stranded RNA interference in Trypanosoma brucei using head-to-head promoters. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 111:67-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, B., Y. Liu, S. A. Motyka, E. E. Agbo, and P. T. Englund. 2005. Fellowship of the rings: the replication of kinetoplast DNA. Trends Parasitol. 21:363-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, B., H. Molina, D. Kalume, A. Pandey, J. D. Griffith, and P. T. Englund. 2006. The role of p38 in replication of Trypanosoma brucei kinetoplast DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:5382-5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukeš, J., D. L. Guilbride, J. Votýpka, A. Ziková, R. Benne, and P. T. Englund. 2002. Kinetoplast DNA network: evolution of an improbable structure. Eukaryot. Cell 1:495-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahmood, R., J. C. Hines, and D. S. Ray. 1999. Identification of cis and trans elements involved in the cell cycle regulation of multiple genes in Crithidia fasciculata. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6174-6182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahmood, R., B. Mittra, J. C. Hines, and D. S. Ray. 2001. Characterization of the Crithidia fasciculata mRNA cycling sequence binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4453-4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmood, R., and D. S. Ray. 1998. Nuclear extracts of Crithidia fasciculata contain factors that bind to the 5′ untranslated regions of TOP2 and RPA1 mRNAs containing sequences required for their cell cycle regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23729-23734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melendy, T., C. Sheline, and D. S. Ray. 1988. Localization of a type II DNA topoisomerase to two sites at the periphery of the kinetoplast DNA of Crithidia fasciculata. Cell 55:1083-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mittra, B., and D. S. Ray. 2004. Presence of a poly(A) binding protein and two proteins with cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation in Crithidia fasciculata mRNA cycling sequence binding protein II. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1185-1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mittra, B., K. M. Sinha, J. C. Hines, and D. S. Ray. 2003. Presence of multiple mRNA cycling sequence element-binding proteins in Crithidia fasciculata. J. Biol. Chem. 278:26564-26571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ntambi, J. M., and P. T. Englund. 1985. A gap at a unique location in newly replicated kinetoplast DNA minicircles from Trypanosoma equiperdum. J. Biol. Chem. 260:5574-5579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ntambi, J. M., T. A. Shapiro, K. A. Ryan, and P. T. Englund. 1986. Ribonucleotides associated with a gap in newly replicated kinetoplast DNA minicircles from Trypanosoma equiperdum. J. Biol. Chem. 261:11890-11895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onn, I., I. Kapeller, K. Abu-Elneel, and J. Shlomai. 2006. Binding of the universal minicircle sequence binding protein at the kinetoplast DNA replication origin. J. Biol. Chem. 281:37468-37476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasion, S. G., G. W. Brown, L. M. Brown, and D. S. Ray. 1994. Periodic expression of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA replication genes during the trypanosomatid cell cycle. J. Cell Sci. 107:3515-3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasion, S. G., J. C. Hines, X. Ou, R. Mahmood, and D. S. Ray. 1996. Sequences within the 5′ untranslated region regulate the levels of a kinetoplast DNA topoisomerase mRNA during the cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6724-6735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan, K. A., and P. T. Englund. 1989. Synthesis and processing of kinetoplast DNA minicircles in Trypanosoma equiperdum. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:3212-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson, L., and P. Braly. 1970. Synchronization of Leishmania tarentolae by hydroxyurea. J. Protozool. 17:511-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinha, K. M., J. C. Hines, N. Downey, and D. S. Ray. 2004. Mitochondrial DNA ligase in Crithidia fasciculata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4361-4366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinha, K. M., J. C. Hines, and D. S. Ray. 2006. Cell cycle-dependent localization and properties of a second mitochondrial DNA ligase in Crithidia fasciculata. Eukaryot. Cell 5:54-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sogin, M. L., and J. D. Silberman. 1998. Evolution of the protists and protistan parasites from the perspective of molecular systematics. Int. J. Parasitol. 28:11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stuart, K. 1991. RNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1:412-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williamson, D. H., and E. Moustacchi. 1971. The synthesis of mitochondrial DNA during the cell cycle in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 42:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wirtz, E., S. Leal, C. Ochatt, and G. A. Cross. 1999. A tightly regulated inducible expression system for conditional gene knock-outs and dominant-negative genetics in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 99:89-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woodward, R., and K. Gull. 1990. Timing of nuclear and kinetoplast DNA replication and early morphological events in the cell cycle of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Cell Sci. 95:49-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zick, A., I. Onn, R. Bezalel, H. Margalit, and J. Shlomai. 2005. Assigning functions to genes: identification of S-phase expressed genes in Leishmania major based on post-transcriptional control elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:4235-4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]