Abstract

Despite the development of new potent antibiotics, Streptococcus pneumoniae remains the leading cause of death from bacterial pneumonia. Polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) recruitment into the lungs is a primordial step towards host survival. Bacterium-derived N-formyl peptides (N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine [fMLP]) and host-derived chemokines (KC and macrophage inflammatory protein 2 [MIP-2]) are likely candidates among chemoattractants to coordinate PMN infiltration into alveolar spaces. To investigate the contribution of each in the context of pneumococcal pneumonia, CD1, BALB/c, CBA/ca, C57BL/6, and formyl peptide receptor (FPR)-knockout C57BL/6 mice were infected with 106 or 107 CFU of penicillin/erythromycin-susceptible or -resistant serotype 3 or 14 S. pneumoniae strains. Antagonists to the FPR, such as cyclosporine H (CsH) and chenodeoxycholic acid, or neutralizing antibodies to KC and MIP-2 were injected either 1 h before or 30 min after infection, and then bronchoalveolar lavage fluids were obtained for quantification of bacteria, leukocytes, and chemokines. CsH was effective over a short period after infection with a high inoculum, while anti-CXC chemokine antibodies were effective after challenge with a low inoculum. CsH prevented PMN infiltration in CD1 mice infected with either serotype 3 or 14, whereas antichemokine antibodies showed better efficacy against the serotype 3 strain. When different mouse strains were challenged with serotype 3 bacteria, CsH prevented PMN migration in the CD1 mice only, whereas the antibodies were effective against CD1 and C57BL/6 mice. Our results suggest that fMLP and chemokines play important roles in pneumococcal pneumonia and that these roles vary according to bacterial and host genetic backgrounds, implying redundancy among chemoattractant molecules.

Lower respiratory tract infections are among the leading causes of death worldwide, and Streptococcus pneumoniae remains the deadliest infectious agent causing this affliction (6, 7). Early polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) infiltration into pulmonary alveolar spaces plays a critical role in restraining bacterial growth (26), thus preventing tissue injury and bacteremia (33). Understanding how PMNs are recruited into the lungs in pneumococcal pneumonia and which chemoattractant factors predominantly regulate this activity is important to further modulate the host response and the outcome of the disease.

CXC chemokines (e.g., interleukin-8 [IL-8] and GRO-α or their murine counterparts, macrophage inflammatory protein 2 [MIP-2] and KC), leukotriene B4, C5a, and platelet-activating factor are known host-derived factors that regulate PMN chemotaxis (11, 19, 30, 36). Pathogen-derived factors such as N-formyl peptides have also been shown to exert strong PMN chemotaxis in vitro and in animal models (9, 14). These soluble peptides are small by-products of protein synthesis released by bacteria into their environment (16). N-Formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) is the best known of them, and it binds to the high-affinity formyl peptide receptor (FPR) and the low-affinity FPR-like 1 (FPRL1) protein on PMNs (31).

However, despite the known participation of bacterial virulence factors and host inflammatory mediators in PMN chemotaxis in vivo (3, 4, 23, 24, 35), the respective roles of fMLP and chemokines in live pneumococcal pneumonia remain poorly defined, especially because the rate of fMLP release remains undetectable in infected tissues. Since fMLP injected into animals can induce calcium mobilization, nitric oxide release, leukocyte chemotaxis, and inflammation, we believe that the role of this peptide in the host response to pneumococci may be underestimated and that it is likely to play a central role in PMN infiltration into the lungs and in the outcome of the disease (28, 31, 32). fMLP was previously shown in vitro to be a more potent chemoattractant than C5a, which, in turn, was more potent than IL-8, MIP-2, and KC (1). Hence, since a hierarchy exists among leukocyte chemoattractants in vitro, we investigated the respective contributions of fMLP and CXC chemokines in pulmonary infection. To address this issue, specific FPR antagonists and CXC chemokine-targeting monoclonal antibodies were injected into mice subjected to pneumococcal pneumonia. Since MIP-2 and KC have been shown to attract PMNs in vitro as well as under various pathological conditions (17, 30, 36), we selected these two chemokines for investigation in our model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

fMLP was purchased from ICN Biomedical (Irvine, CA). Cyclosporine H (CsH) was a generous gift from Novartis Pharma (Dorval, Quebec, Canada). Chenodeoxycholic acid was obtained from Sigma (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Monoclonal anti-KC and anti-MIP-2 antibodies for blocking experiments and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were purchased from Cedarlane Laboratories Ltd. (Hornby, Ontario, Canada). Biotinylated goat anti-MIP-2 and anti-KC antibodies and recombinant mouse MIP-2 and KC were all obtained from Cedarlane Laboratories Ltd.

Animals.

Female CD1 Swiss mice weighing 18 to 20 g (Charles River, St. Constant, Quebec, Canada) were used in all experiments. Female BALB/c and CBA/ca mice aged 6 to 7 weeks (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and female C57BL/6 mice weighing 18 to 20 g (Taconic, Hudson, NY) were also used to determine the impact of genetic variation of mouse strains on the host response to infection. A colony of knockout mice for the fpr gene (KO-FPR), backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for six generations, was bred on-site, with breeding pairs kindly donated by P. M. Murphy and J. L. Gao (Laboratory of Host Defenses, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, MD). All animals were maintained on a standard chow pellet diet with tap water ad libitum, using a 12-h light-dark cycle. All experimental procedures were approved by the Laval University Animal Protection Committee and were conducted in compliance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Bacteria.

Clinical isolates of penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae serotype 3 and 14 strains as well as of penicillin- and erythromycin-resistant S. pneumoniae serotype 14 strains were used. First, they were grown on blood agar for 10 to 13 h. Freshly grown colonies were incubated in brain heart infusion broth at 37°C with 5% CO2 to reach the log phase of growth (optical density at 600 nm, 0.4 to 0.6). Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (2,400 × g for 15 min), washed twice, and then resuspended in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at an appropriate concentration for inoculation into mice. Serial 10-fold dilutions were plated on blood agar to confirm the final concentration of the bacterial inoculum.

Pneumococcal pneumonia model.

Our previously described mouse model of pneumococcal pneumonia was used in this study (8). Briefly, mice were lightly anesthetized by inhalation of 2 to 4% isoflurane and then infected with 106 CFU (low inoculum) or 107 CFU (high inoculum) of S. pneumoniae contained in 50 μl of PBS applied at the tip of the nose and involuntarily inhaled. The two inocula were chosen based on their efficacy at inducing pneumonia in 100% of the mice, though they induced weak versus strong (three- to fivefold difference) PMN infiltration into the lungs, respectively.

fMLP preparation.

An fMLP suspension (2 mg/ml) was prepared by sonication in saline (0.85% NaCl) on ice to generate fine particles that could gain access to the lower respiratory tract and initiate neutrophil migration. Injection of purified fMLP served as a control to verify the blocking potency of inhibitors that were used against pneumonia.

Blocking experiments.

Experiments with antagonists of the FPR were designed to explore the contribution of fMLP to PMN migration into alveolar spaces of infected mice. In these sets of experiments, groups of mice (from all strains mentioned above, including the KO mice) were infected with S. pneumoniae or received one intranasal injection of 100 μg fMLP. Mice (infected or challenged with fMLP) were then subjected to either one oral dose (by gavage) of 50 μg/mouse of CsH 1 h prior to the infection or one intravenous (i.v.) injection of 8 μg/mouse of chenodeoxycholic acid 30 min after the infection. These doses and times were chosen to allow proper recognition and blockade of the FPR by the inhibitors. Control groups were injected with the corresponding diluent (ethanol-corn oil [1:9] for CsH and PBS for chenodeoxycholic acid). Animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under anesthesia at 6 h, 12 h, or 24 h postinfection. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was sampled to quantify leukocytes, bacteria, and chemokines. BALF was obtained as previously described (8). Briefly, the trachea was exposed and intubated with a 22G1 sterile catheter, and lungs were washed three times with 0.7 ml of PBS. BALF samples were centrifuged at 750 × g for 10 min, and supernatants were stored at −20°C until quantification of the chemokines by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Pellets were resuspended in PBS for total cell counts with an automated cell counter (Cell-Dyn 3700; Abbott) and for differential counts with Diff-Quick-stained (VWR) cytospin preparations. Bacterial counts in BALF were done by plating serial 10-fold dilutions on blood agar.

Another set of experiments was designed to investigate the contribution of CXC chemokines (MIP-2 and KC) to PMN recruitment to the pulmonary alveolar spaces. Briefly, 10 μg/mouse of either MIP-2 or KC neutralizing monoclonal antibody, or a combination of both, was injected i.v. into mice 30 min prior to the infection. All mouse strains mentioned above were infected with a low (106 CFU) or a high (107 CFU) inoculum of the bacterial strains. Sacrifice was made at 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h postinfection for sampling of BALF. PMN counts were performed, and chemokine levels were quantified.

Determination of chemokine protein expression.

Ninety-six-well plates (Maxi-Sorp; Nunc) were coated with monoclonal anti-MIP-2 antibody (0.25 μg/ml) (clone 40605; Cedarlane) or monoclonal anti-KC antibody (0.25 μg/ml) (clone 48415; Cedarlane) in coating buffer (PBS, pH 7.4) for 16 to 18 h at 4°C. The plates were then blocked by incubation with PBS-5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 and dilution with PBS-2% BSA, cell-free BALF supernatant or recombinant mouse KC or MIP-2 (for standard curves) was added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed three times, followed by the addition of the corresponding biotinylated goat antichemokine antibody (Cedarlane) diluted to 0.125 μg/ml (for anti-MIP-2) or 0.031 μg/ml (for anti-KC), and then were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing of the cells, poly-horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin (RDI) diluted 1:4,000 in PBS-2% BSA-0.05% Tween 20 was added and incubated for 45 min at room temperature in the dark. Plates were washed three times, TMB substrate (RDI) was added, and the plates were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 to 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.18 M H2SO4, and plates were read at 450 nm in an automated plate reader.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed, unpaired t test for PMN counts and chemokine levels. Bacterial counts were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

fMLP-induced PMN recruitment.

We first checked for the specificity of CsH in binding the FPR and thus preventing fMLP-induced PMN infiltration into the lungs. Following intranasal administration of 100 μg of purified fMLP to CD1 mice, PMNs were fully recruited to the alveolar spaces, reaching 6.7 × 105 ± 0.79 × 105/ml of BALF within 6 h. Negligible counts of PMNs were detected in BALF from control mice. In animals treated with CsH, PMN infiltration was reduced 33%, reaching 4.47 × 105 ± 0.44 × 105/ml (P < 0.05). To confirm the direct activity of the compound against fMLP-induced chemotaxis of PMNs in vivo, we checked for potential artifacts. The results showed that CsH had no in vivo toxicity on alveolar leukocytes after 6 h (cells isolated from BALF of normal mice and analyzed by a Cell-Dyn counter had counts of 0.245 × 105 ± 0.019 × 105/ml and 0.214 × 105 ± 0.015 × 105/ml following one oral dose of diluent and one oral dose of 50 μg of CsH, respectively [data are means ± SEM for seven or eight values]) and did not induce leucopenia (blood analysis by a Cell-Dyn counter gave counts of 4.40 × 106 ± 0.49 × 106/ml and 5.26 × 106 ± 0.85 × 106/ml following one oral dose of diluent and one oral dose of 50 μg of CsH, respectively).

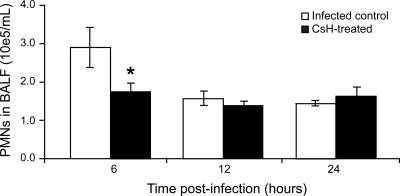

We then studied bacterium-derived fMLP activity during active pneumococcal pneumonia. After administration of a high inoculum (107 CFU) of S. pneumoniae serotype 3 to CD1 mice pretreated with CsH, PMNs were counted in BALF 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h after infection (Fig. 1). A significant reduction (46%) in PMN migration was observed in the CsH-treated group (1.57 × 105 ± 0.19 × 105/ml of BALF) compared to the infected control group (2.89 × 105 ± 0.52 × 105/ml of BALF) (P < 0.05) at 6 h postinfection. However, this effect was not observed later on, at 12 h and 24 h (even when additional doses of CsH were given at 4 h and 8 h postinfection).

FIG. 1.

Effect of CsH on pneumococcus-induced PMN recruitment into the lungs of CD1 mice over time. Animals were pretreated with an oral dose of 50 μg CsH (or diluent). One hour later, mice were infected with 107 CFU of S. pneumoniae serotype 3, and they were sacrificed at 6 h, 12 h, or 24 h postinfection. *, P < 0.05 (compared to infected controls). Data are means ± SEM for six mice per group.

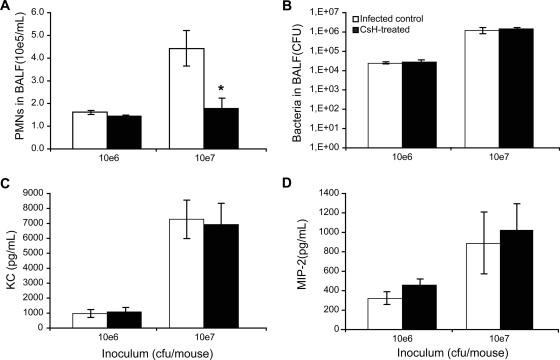

We further tested the efficacy of CsH in preventing PMN chemotaxis to alveolar spaces after infection with a low-inoculum dose. S. pneumoniae serotype 3 given at 106 CFU was compared to a dose of 107 CFU in CD1 mice pretreated with the same amount of CsH as that described above. PMNs in BALF were quantified at 6 h postinfection. Mice that were infected with the highest inoculum showed a 60% reduction in PMNs for the CsH-treated group compared to the corresponding infected controls (1.77 × 105 ± 0.45 × 105/ml versus 4.42 × 105 ± 0.78 × 105/ml; P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, CsH did not prevent the modest PMN migration observed in mice infected with the low inoculum. The effect of CsH on PMN counts with the high inoculum did not result from any influence of the compound on bacterial growth in lungs (Fig. 2B) or on CXC chemokine (MIP-2 and KC) production (Fig. 2C and D).

FIG. 2.

Effect of inoculum size on the blocking efficacy of CsH against PMN recruitment. One hour after pretreatment with an oral dose of 50 μg CsH, CD1 mice were infected with 106 or 107 CFU of S. pneumoniae serotype 3. Mice were sacrificed at 6 h postinfection, and BALF samples were obtained. (A) PMN counts in BALF. (B) Bacterial counts in BALF. (C) MIP-2 levels in BALF. (D) KC levels in BALF. Data are means ± SEM for six mice per group. *, P < 0.05 (compared to infected controls).

To confirm the specificity of FPR blockade as the mechanism whereby CsH reduces PMN chemotaxis during pneumococcal pneumonia, chenodeoxycholic acid, a bile salt that is a specific antagonist (ligand) of the FPR, was used. When the drug was injected shortly after infection with a high inoculum (107 CFU), the treated mice showed a significant reduction (38%) of PMN migration into the BALF compared to the infected control mice (2.77 × 105 ± 0.49 × 105 PMNs/ml versus 4.47 × 105 ± 0.51 × 105 PMNs/ml; P < 0.05). This reduction was observed 6 h after infection, whereas no difference was detected later on, at 12 h and 24 h, similar to the case for CsH-treated mice.

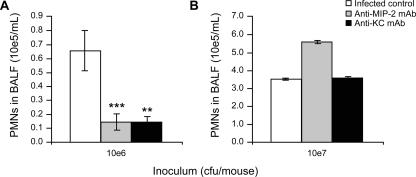

Contribution of CXC chemokines to neutrophilic migration.

The contribution of CXC chemokines (KC and MIP-2) to PMN recruitment into the alveolar spaces was assessed in the context of pneumococcal pneumonia. To be consistent with the experiments with CsH, we compared a low (106 CFU) and a high (107 CFU) inoculum. Administration of anti-MIP-2 and anti-KC monoclonal antibodies 30 min prior to the infection led to 79% and 78% reductions in PMN migration, respectively, 6 h after infection with a low inoculum (Fig. 3A) compared to the level with the nonspecific IgG control (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively). When a high inoculum was used, anti-CXC chemokine antibodies were ineffective at preventing PMN recruitment (Fig. 3B). These results contrast with the opposite data observed with the FPR antagonists.

FIG. 3.

Contribution of CXC chemokines to PMN migration into the lungs. CD1 mice were pretreated with one i.v. dose of 10 μg anti-MIP-2 or 10 μg anti-KC monoclonal antibody or 10 μg of nonspecific IgG (infected control) 30 min before infection with 106 CFU (A) or 107 CFU (B) of S. pneumoniae serotype 3. Mice were sacrificed at 6 h postinfection to obtain BALF for PMN counts. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (compared to IgG control). Data are means ± SEM for 6 to 12 mice per group.

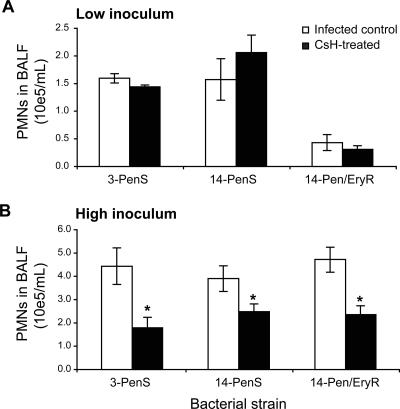

Influence of bacterial genetic variation on fMLP- and chemokine-induced PMN infiltration.

To investigate the influence of bacterial genotypic/phenotypic variation on the relative fMLP and chemokine contributions to alveolar recruitment of PMNs, three S. pneumoniae strains from two different serotypes characterized by two different antibiotic susceptibility profiles were used to infect CD1 mice. Despite the fact that S. pneumoniae strains induced various PMN responses, only with the high inoculum did CsH prevent this response by 37% to 60% for the three strains tested (Fig. 4A and B).

FIG. 4.

Impact of bacterial genetic background on fMLP contribution to PMN recruitment into the lungs. One hour after pretreatment with an oral dose of 50 μg CsH (or diluent for the controls), CD1 mice were infected with either 106 CFU (A) or 107 CFU (B) of S. pneumoniae serotype 3 or serotype 14, displaying susceptibility (S) or resistance (R) to penicillin (Pen) or penicillin and erythromycin (Pen/Ery). Mice were sacrificed at 6 h postinfection to perform PMN counts on BALF. *, P < 0.05 (compared to corresponding infected controls). Data are means ± SEM for five or six mice per group.

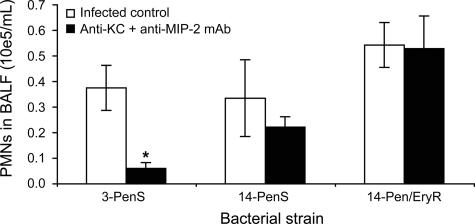

Anti-MIP-2 and anti-KC monoclonal antibodies, even when given in combination, did not prevent PMN infiltration induced by serotype 14 strains (either susceptible or resistant to penicillin and erythromycin), whereas they prevented up to 84% of PMN recruitment for the serotype 3 penicillin-susceptible strain given at a low inoculum (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). The effect of the antibodies was not seen at the same time point after a high-inoculum dose (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Impact of bacterial genetic background on chemokine contribution to PMN recruitment into the lungs. Thirty minutes after pretreatment with an i.v. dose of a combination of 10 μg anti-MIP-2 and 10 μg anti-KC monoclonal antibodies (or 20 μg of nonspecific IgG for the infected controls), CD1 mice were infected with 106 CFU of S. pneumoniae serotype 3 or 14, displaying susceptibility (S) or resistance (R) to penicillin (Pen) or penicillin and erythromycin (Pen/Ery). Mice were sacrificed at 6 h postinfection to perform PMN counts on BALF. *, P < 0.05 (compared to corresponding infected controls). Data are means ± SEM for five or six mice per group.

Influence of host genetic variation on fMLP- and chemokine-induced PMN infiltration.

In the next set of experiments, we checked for the influence of mouse interstrain variability on the host response to infection and, more specifically, for the relative role of fMLP and chemokines on PMN migration from the bloodstream to pulmonary alveoli. The penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae serotype 3 strain was used to infect BALB/c, CBA/ca, and C57BL/6 inbred mouse strains in addition to CD1 outbred mice. These strains were chosen based on their different susceptibilities to pneumococci. BALB/c mice are known to be quite resistant to infection, C57BL/6 mice develop pulmonary infection and septicemia (but die a few days later than CD1 mice in this model), and CBA/ca mice are quite susceptible to pneumococci (2, 18, 25, 34).

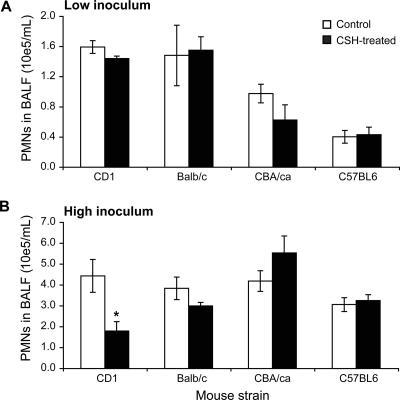

Surprisingly, only the CD1 strain responded to CsH after severe infection, displaying a marked reduction in PMN migration to the lungs at 6 h postinfection for the high inoculum only (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6B). No significant reduction was observed after a low inoculum was used for any of the four strains tested (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Impact of host genetic background on fMLP contribution to PMN recruitment into the lungs. One hour after pretreatment with an oral dose of 50 μg CsH (or diluent for the controls), CD1, BALB/c, CBA/ca, and C57BL/6 mice were infected with either 106 CFU (A) or 107 CFU (B) of penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae serotype 3. Mice were sacrificed at 6 h postinfection to perform PMN counts on BALF. *, P < 0.05 (compared to corresponding infected controls). Data are means ± SEM for 6 to 12 mice per group.

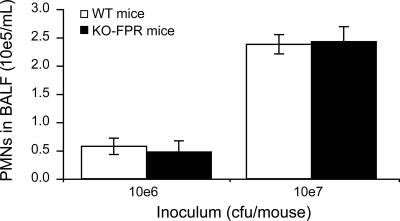

To further investigate the potential contribution of fMLP to PMN recruitment, C57BL/6 KO-FPR mice devoid of FPR activity were used. Fig. 7 shows similar PMN counts in pulmonary alveoli (BALF) of wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice and their KO-FPR counterparts 6 h after infection with either the low or the high inoculum. Bacterial growth in lungs was quantified 6 h after infection with 107 CFU to verify the efficacy of pneumococci at infecting C57BL/6 mice, and it was found to be similar (no statistical difference) in KO-FPR mice (1.0 × 106 ± 0.4 × 106/ml) and WT mice (2.1 × 106 ± 1.0 × 106/ml).

FIG. 7.

PMNs recovered from BALF of KO-FPR mice infected with a low or a high inoculum of S. pneumoniae. WT and KO-FPR mice were infected with 106 or 107 CFU of S. pneumoniae serotype 3 and were sacrificed 6 h later. Data are means ± SEM for 6 to 12 mice per group.

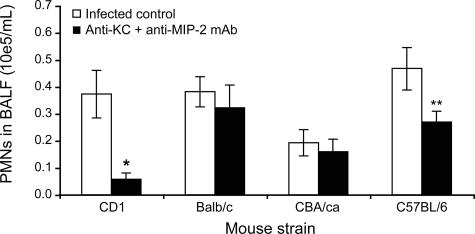

Antibodies against the CXC chemokines (MIP-2 and KC) did not prove to be effective in preventing PMN migration to the lungs in BALB/c and CBA/ca mice but significantly reduced it in CD1 and C57BL/6 mice infected with the low inoculum of pneumococci (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Impact of host genetic background on chemokine contribution to PMN recruitment into the lungs. Thirty minutes after pretreatment with an i.v. dose of a combination of 10 μg anti-MIP-2 and 10 μg anti-KC monoclonal antibodies (or 20 μg of nonspecific IgG for the infected controls), CD1, BALB/c, CBA/ca, and C57BL/6 mice were infected with 106 CFU of penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae serotype 3. Mice were sacrificed at 6 h postinfection to perform PMN counts on BALF. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared to corresponding infected controls). Data are means ± SEM for 6 to 12 mice per group.

DISCUSSION

The role of N-formyl peptides as chemoattractant molecules has been studied widely (10, 14, 15, 29). However, the influence of fMLP on the orchestration of leukocyte responses in bacterial infections remains poorly investigated. This might be due to the fact that no FPR-neutralizing antibody for mice has yet been engineered, but also, fMLP could not be quantified in live infections due to technical limitations and potentially misleading interpretations. Thus, we investigated fMLP-dependent leukocyte chemotaxis through the use of specific FPR antagonists. Our previous works (16) revealed that BOC- PLPLP, one of the antagonists, inhibits up to 42% of monocyte infiltration in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. Since both monocytes and PMNs possess FPR1 and FPR2 (20), we sought in the present study to investigate the role of fMLP in PMN infiltration into the lungs in pneumococcal pneumonia. Various chemoattractants likely coordinate PMN chemotaxis to their destination over the course of pneumonia, so we investigated the respective roles of fMLP and CXC chemokines in diverse mouse strains infected with two different inocula of S. pneumoniae strains displaying various genotypic/phenotypic backgrounds.

Overall, the effects of CsH, an antagonist of the FPR, in CD1 mice infected with S. pneumoniae serotype 3 were seen over only a short period of time after infection with a high inoculum, while anti-CXC chemokine antibodies were effective mainly after challenge with a low inoculum. When three different S. pneumoniae strains were injected into CD1 mice, CsH significantly prevented PMN infiltration for serotypes 3 and 14, independently of their susceptibility to antibiotics, whereas antichemokine antibodies were effective only against the serotype 3 strain. When different mouse strains were challenged with serotype 3 bacteria, CsH prevented PMN migration in the CD1 mice only, whereas blockade was achieved in the CD1 and C57BL/6 mouse strains by antichemokine antibodies.

In the present experiments, CsH specificity was confirmed by the use of chenodeoxycholic acid, and potential artifacts (e.g., cytotoxicity) were ruled out. The observed CsH efficacy following a high inoculum of pneumococci suggests a high level of fMLP release shortly after infection (disregarding the serotype or antibiotic susceptibility of the strain tested) that contributed to a rapid host response through innate immunity. However, the FPR antagonists did not prevent PMN chemotaxis at 12 h and 24 h, even after multiple injections, suggesting that other chemoattractants prevailed over time. Another possibility would be that phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages could temporarily restrain bacteria and fMLP amounts in alveoli. In fact, pneumococcal growth in lungs was already reported to decrease and stabilize over the first 4 to 12 h in this model and then to increase sharply after 24 h or to be cleared, depending on the size of the initial inoculum (12, 13).

CsH failed to prevent PMN infiltration in mice challenged with a low inoculum that induced subacute infection, suggesting again the involvement of other sensitive chemotactic agents that can be activated by small numbers of bacteria. High KC and MIP-2 secretion was observed in mice shortly after infection with either a low or a high inoculum of serotype 3 pneumococci. The observed efficacy of antichemokine antibodies in mice facing subacute pneumonia suggests a substantial role for CXC chemokines in PMN infiltration into the lungs. However, considering the greater efficacy of FPR antagonists in severe pneumonia, our results support the hierarchy of chemoattractant potencies proposed by Ali et al. (1) for fMLP and CXC chemokines. Ali et al. also showed that fMLP can induce autodesensitization of its own FPR. If that occurred, formyl peptides released by live or destroyed bacteria in the lungs at 12 h and 24 h postinfection may have initiated FPR desensitization, thus leaving the opportunity for chemokines, C5a, leukotriene B4, platelet-activating factor, or other factors to prevail as main chemoattractants for PMN infiltration.

Interestingly, the extent of CXC chemokine participation appeared to be linked to the type of pneumococcus involved, with the penicillin-susceptible serotype 3 strain being the only one tested to induce antibody-reversible MIP-2- and KC-dependent PMN infiltration into the lungs of CD1 mice. Colonization of airways and invasiveness by serotype 3 and 14 pneumococci have been shown to differ from each other, especially when phenotypes of antibiotic resistance are noted (27). It is known that differences in capsular polysaccharide contents of pneumococcal strains influence phagocytosis (21) and that surface proteins can also interfere with the alternative and classical pathways of complement (22). It is less clear to what extent these factors impact the activity of C5a and the activation of specific chemokines by serotypes 3 and 14, respectively.

Our experiments also showed that genetic variation in the host greatly influences the respective contributions of fMLP and CXC chemokines to PMN recruitment into the lungs. Only the CD1 mice responded positively to the fMLP antagonist. This finding was further confirmed in experiments with KO-FPR mice, which showed similar PMN counts in lungs to those of WT infected controls, suggesting a greater role for chemokines than for fMLP in C57BL/6 mice. Actually, antichemokine antibodies showed efficacy in C57BL/6 mice but not in CBA/Ca and BALB/c mice.

It is likely that outbred mice (CD1) responded to infection with greater variability (due to activation of a larger repertoire of receptors and mediators in their subpopulations) than did inbred mice (C57BL/6, CBA/Ca, and BALB/c). In fact, much of the negative data in this work might be explained by the concept of redundancy. In other words, many cytokines/chemokines and other regulators of leukocyte responses share the common ability to trigger proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory responses. When a particular inhibitor is used without effect on leukocyte recruitment, it may simply mean that some other signaling pathway compensates in the absence of the system being inhibited (5). Much remains to be done to fully delineate the complexity of the host immune response to Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant CIHR-MOP-57744 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Marie-Christine Dumas is a recipient of Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) student scholarships.

CsH was a generous gift from Novartis Pharma, Dorval, Canada. We thank Philip M. Murphy and Ji-Liang Gao from the Laboratory of Host Defenses, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, MD, who kindly provided the KO-FPR mice.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, H., R. M. Richardson, B. Haribabu, and R. Snyderman. 1999. Chemoattractant receptor cross-desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 274:6027-6030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay-Dupuis, E., J. P. Bedos, E. Vallée, and J. J. Pocidalo. 1991. Comparative activity of fluorinated quinolones in acute and subacute Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia models: efficacy of temafloxacin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 28(Suppl. C):45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barocchi, M. A., J. Ries, X. Zogaj, C. Hemsley, B. Albiger, A. Kanth, S. Dahlberg, J. Fernebro, M. Moschioni, V. Masignani, K. Hultenby, A. R. Taddei, K. Beiter, F. Wartha, A. von Euler, A. Covacci, D. W. Holden, S. Normark, R. Rappuoli, and B. Henriques-Normark. 2006. A pneumococcal pilus influences virulence and host inflammatory responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2857-2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beiter, K., F. Wartha, B. Albiger, S. Normark, A. Zychlinsky, and B. Henriques-Normark. 2006. An endonuclease allows Streptococcus pneumoniae to escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr. Biol. 16:401-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergeron, Y., and M. G. Bergeron. 2006. Cytokine and chemokine network in the infected lung, p. 57-74. In A. Torres, S. Ewig, L. Mandell, and M. Woodhead (ed.), Respiratory infections. Edward Arnold Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

- 6.Bergeron, Y., and M. G. Bergeron. Pulmonary infections in the immunocompromised host. In C. J. D. Patterson, T. W. Rice, A. Lerut, F. G. Pearson, J. Deslauriers, and J. D. Luketich (ed.), Pearson's thoracic and esophageal surgery, 3rd ed., in press. Churchill Livingston, Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA.

- 7.Bergeron, Y., and M. G. Bergeron. 1999. Why does pneumococcus kill? Can. J. Infect. Dis. 10:49C-60C. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergeron, Y., N. Ouellet, A. M. Deslauriers, M. Simard, M. Olivier, and M. G. Bergeron. 1998. Cytokine kinetics and other host factors in response to pneumococcal pulmonary infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 66:912-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokoch, G. M. 1995. Chemoattractant signaling and leukocyte activation. Blood 86:1649-1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulay, F., and M. J. Rabiet. 2005. The chemoattractant receptors FPR and C5aR: same functions-different fates. Traffic 6:83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crooks, S. W., and R. A. Stockley. 1998. Leukotriene B4. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 30:173-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dallaire, F., N. Ouellet, Y. Bergeron, V. Turmel, M. C. Gauthier, M. Simard, and M. G. Bergeron. 2001. Microbiological and inflammatory factors associated with the development of pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 184:292-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dallaire, F., N. Ouellet, M. Simard, Y. Bergeron, and M. G. Bergeron. 2001. Efficacy of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in a murine model of pneumococcal pneumonia: effects of lung inflammation and timing of treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 183:70-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalpiaz, A., S. Spisani, C. Biondi, E. Fabbri, M. Nalli, and M. E. Ferretti. 2003. Studies on human neutrophil biological functions by means of formyl-peptide receptor agonists and antagonists. Curr. Drug Targets Immune Endocr. Metabol. Disord. 3:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durr, M. C., S. A. Kristian, M. Otto, G. Matteoli, P. S. Margolis, J. Trias, K. P. van Kessel, J. A. van Strijp, E. Bohn, R. Landmann, and A. Peschel. 2006. Neutrophil chemotaxis by pathogen-associated molecular patterns—formylated peptides are crucial but not the sole neutrophil attractants produced by Staphylococcus aureus. Cell. Microbiol. 8:207-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fillion, I., N. Ouellet, M. Simard, Y. Bergeron, S. Sato, and M. G. Bergeron. 2001. Role of chemokines and formyl peptides in pneumococcal pneumonia-induced monocyte/macrophage recruitment. J. Immunol. 166:7353-7361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuhler, G. M., G. J. Knol, A. L. Drayer, and E. Vellenga. 2005. Impaired interleukin-8- and GROalpha-induced phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase result in decreased migration of neutrophils from patients with myelodysplasia. J. Leukoc. Biol. 77:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gingles, N. A., J. E. Alexander, A. Kadioglu, P. W. Andrew, A. Kerr, T. J. Mitchell, E. Hopes, P. Denny, S. Brown, H. B. Jones, S. Little, G. C. Booth, and W. L. McPheat. 2001. Role of genetic resistance in invasive pneumococcal infection: identification and study of susceptibility and resistance in inbred mouse strains. Infect. Immun. 69:426-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, R. F., and P. A. Ward. 2005. Role of C5a in inflammatory responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:821-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartt, J. K., G. Barish, P. M. Murphy, and J. L. Gao. 1999. N-Formylpeptides induce two distinct concentration optima for mouse neutrophil chemotaxis by differential interaction with two N-formylpeptide receptor (FPR) subtypes. Molecular characterization of FPR2, a second mouse neutrophil FPR. J. Exp. Med. 190:741-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hostetter, M. K. 1986. Serotypic variations among virulent pneumococci in deposition and degradation of covalently bound C3b: implications for phagocytosis and antibody production. J. Infect. Dis. 153:682-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janulczyk, R., F. Iannelli, A. G. Sjoholm, G. Pozzi, and L. Bjorck. 2000. Hic, a novel surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae that interferes with complement function. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37257-37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones, M. R., B. T. Simms, M. M. Lupa, M. S. Kogan, and J. P. Mizgerd. 2005. Lung NF-{kappa}B activation and neutrophil recruitment require IL-1 and TNF receptor signaling during pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Immunol. 175:7530-7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jounblat, R., H. Clark, P. Eggleton, S. Hawgood, P. W. Andrew, and A. Kadioglu. 2005. The role of surfactant protein D in the colonisation of the respiratory tract and onset of bacteraemia during pneumococcal pneumonia. Respir. Res. 6:126-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerr, A. R., J. J. Irvine, J. J. Search, N. A. Gingles, A. Kadioglu, P. W. Andrew, W. L. McPheat, C. G. Booth, and T. J. Mitchell. 2002. Role of inflammatory mediators in resistance and susceptibility to pneumococcal infection. Infect. Immun. 70:1547-1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi, S. D., J. M. Voyich, C. Burlak, and F. R. DeLeo. 2005. Neutrophils in the innate immune response. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsaw) 53:505-517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kronenberg, A., P. Zucs, S. Droz, and K. Muhlemann. 2006. Distribution and invasiveness of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in Switzerland, a country with low antibiotic selection pressure, from 2001 to 2004. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2032-2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan, Z. K., L. Y. Chen, C. G. Cochrane, and B. L. Zuraw. 2000. fMet-Leu-Phe stimulates proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in human peripheral blood monocytes: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Immunol. 164:404-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabiet, M. J., E. Huet, and F. Boulay. 2005. Human mitochondria-derived N-formylated peptides are novel agonists equally active on FPR and FPRL1, while Listeria monocytogenes-derived peptides preferentially activate FPR. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:2486-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sager, R., S. Haskill, A. Anisowicz, D. Trask, and M. C. Pike. 1991. GRO: a novel chemotactic cytokine. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 305:73-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selvatici, R., S. Falzarano, A. Mollica, and S. Spisani. 2006. Signal transduction pathways triggered by selective formyl peptide analogues in human neutrophils. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 534:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sodhi, A., and S. K. Biswas. 2002. fMLP-induced in vitro nitric oxide production and its regulation in murine peritoneal macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 71:262-270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, E., M. Simard, N. Ouellet, Y. Bergeron, D. Beauchamp, and M. G. Bergeron. 2002. Pathogenesis of pneumococcal pneumonia in cyclophosphamide-induced leukopenia in mice. Infect. Immun. 70:4226-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe, H., K. Numata, T. Ito, K. Takagi, and A. Matsukawa. 2004. Innate immune response in Th1- and Th2-dominant mouse strains. Shock 22:460-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witzenrath, M., B. Gutbier, A. C. Hocke, B. Schmeck, S. Hippenstiel, K. Berger, T. J. Mitchell, J. R. de los Toyos, S. Rosseau, N. Suttorp, and H. Schutte. 2006. Role of pneumolysin for the development of acute lung injury in pneumococcal pneumonia. Crit. Care Med. 34:1947-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeilhofer, H. U., and W. Schorr. 2000. Role of interleukin-8 in neutrophil signaling. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 7:178-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]