Abstract

Protective immunity in tuberculosis is dependent on the coordinated release of cytolytic effector molecules from effector T cells and the subsequent granule-associated killing of infected target cells. In this study, we investigated the expression of cytolytic (perforin and granzyme A) and antimicrobial (granulysin) molecules at the single-cell level in cryopreserved lung tissue from patients with chronic, progressive tuberculosis disease. Quantification of protein-expressing cells was performed by in situ imaging, while mRNA levels in the infected tissue were analyzed by real-time PCR. Persistent inflammation, including excessive expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in CD68+ macrophages and significant infiltration of CD3+, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, was evident in tuberculosis lesions in all patients. However, despite the accumulation of CD3+ T cells, perforin- and granulysin-expressing CD3+ T cells were detected at two- to threefold-lower ratios in the tuberculosis lesions than in distal lung parenchyma and uninfected control lungs, respectively. This was evident at both the protein and mRNA levels. Moreover, perforin- and granulysin-expressing CD8+ T cells were scarce in individual granulomas within the tuberculosis lesions. In contrast, significant up-regulation of granzyme A-expressing CD3+ T cells was evident in the lesions from all patients. Confocal microscopy revealed coexpression of perforin and granulysin, primarily in CD8+ T cells; however, this expression was lower in the tuberculosis lesions. These findings suggest that symptomatic, chronic tuberculosis disease is associated with insufficient up-regulation of perforin and granulysin coexpression in CD8+ T cells at the local site of infection.

Tuberculosis (TB) in humans can result in active disease with various clinical manifestations in approximately 10% of infected individuals. Of critical importance in persistent TB control are innate immune responses in macrophages and neutrophils (63), including the production of nitric oxide (NO) (50, 70). Nevertheless, alterations in the balance of cell-mediated immunity reduce the capacity of the host to mediate protection against this granulomatous disease. Therefore, adaptive immune responses, including cytolytic T-cell (CTL) activity, are required to achieve full protection, as well as to cure (22, 29). It is well established that CTLs use either granule- or receptor-mediated killing in order to eliminate infected target cells at the site of infection. Reports on human (10, 18, 47, 61) and mouse (54, 57) TB have provided evidence that mainly T cells that use granule-dependent killing and not Fas/FasL-induced apoptosis of target cells is efficient in decreasing the viability of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. Granule-mediated lysis of M. tuberculosis-infected cells has been shown to be performed mainly by CD8+ and NK T cells expressing perforin and granulysin (23, 54, 60), while the contribution of Fas/FasL is dependent on target cell susceptibility to Fas/FasL-mediated killing (34). Virulent M. tuberculosis strains have been shown to induce Bcl-2 during bacterial replication in macrophages, rendering these cells resistant to FasL-mediated attack (75). Instead, it has been suggested that disease progression is associated with Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis of M. tuberculosis-reactive T cells (35, 46). Thus, the Fas/FasL pathway may be more important in the homeostatic regulation of the T-cell response upon TB infection in humans (32, 71).

CTLs produce cytolytic (e.g., perforin and granzymes) and antimicrobial (e.g., granulysin) molecules, which are released from granules into the intercellular space between the CTL and the infected target cells. It is believed that perforin forms pores in cellular membranes to facilitate entry and endosome-mediated transportation of granzymes and/or granulysin to the intracellular compartments via a newly identified membrane repair mechanism (30). Granzymes A and B are translocated to the nucleus to induce target cell apoptosis (74), whereas granulysin can trigger apoptosis directly (41) and attack the mycobacterial cell membrane inside the endosomes of infected macrophages (60). Granulysin creates cell wall lesions, promotes osmotic lysis of bacteria, and reduces M. tuberculosis growth in a perforin-dependent manner (19, 60). Accordingly, coordinated expression of effector functions, such as cytolytic perforin (64, 73) and antimicrobial granulysin (23, 59, 73), seems to be required for the control of human TB (9, 18).

The collective actions of infected macrophages and different immune cells initiate the development of characteristic tuberculous granulomas (66) that contain the TB infection. Hence, the host response rarely results in complete eradication and clearance of M. tuberculosis bacteria but rather restricts the infection to a dormant state (48). During progressive disease, M. tuberculosis granulomas are typically characterized by central necrosis and liquefaction caused by the immune activation occurring at this site (14, 48). This process primarily involves macrophages and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells but also involves a wide array of nonclassical T cells, such as γδ T cells and CD1-restricted αβ T cells (12, 69). Uncontrolled activation of these cells results in loss of normal pulmonary architecture due to massive tissue necrosis which can lead to cavity formation.

The coordinated release of perforin and granulysin by CTLs may represent one of the major defense mechanisms of the human host efficient in restricting mycobacterial growth. Thus, we aimed to investigate whether these cytolytic effector molecules could be identified as correlates of protective immunity in human TB. Our hypothesis was that persistence of clinical disease is associated with deficient expression of perforin and granulysin at the local site of TB infection. Here, we assessed the expression of cytolytic effector molecules and the prevalence as well as phenotype of infiltrating T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in chronic pulmonary TB in humans. Local immune responses in the pulmonary tissue were gauged in both proximal and distal parts of TB lesions from patients with progressive, chronic disease. The protein expression of cytolytic effector molecules in CTLs was characterized in situ at the single-cell level and compared to levels of mRNA in the tissue. In addition, the phenotype of cells expressing these effector molecules was investigated using two-color staining and confocal microscopy. We demonstrated that active inflammation and T-cell infiltration of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells occurred in the pulmonary lesions of patients with chronic TB infection compared to distal lung parenchyma and uninfected control lungs. However, despite the increase in inflammation, the levels of perforin or granulysin remained low in the TB lesions, and this response included severely impaired expression of these cytolytic effector molecules inside distinct granulomas. Simultaneously, we showed that the numbers of granzyme A-expressing cells were elevated in the TB lesions, suggesting that the down-regulation of perforin and granulysin was selective and not a universal phenomenon involving all cytolytic effector molecules. Coexpression of perforin and granulysin occurred only in granules in CD8+ T cells, and a very low proportion of CD8+ T cells expressed perforin and granulysin in the TB lesions. Our results provide the first evidence that chronic pulmonary TB is associated with impaired perforin and granulysin expression in CD8+ T cells at the local site of infection. Such dysfunctional CTLs could promote active progression of infection and contribute to the chronicity of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Surgical treatment of TB in Russia is performed when the patient fails to respond to conventional treatment with first- and/or second-line drugs due to irregular use of anti-TB drugs and/or development of multidrug-resistant TB. In Russia, excessively long treatment with anti-TB drugs is generally not recommended, and therefore patients with multiple caverns or tuberculomas who cannot be efficiently cured by means of chemotherapy are often given surgical treatment (44). Upon thoracic surgery, areas of damaged and fibrotic tissue are removed in order to decrease the mycobacterial load and thus prevent disease progression. For this study, lung tissue biopsies were obtained from 19 adult patients undergoing surgical treatment for chronic TB. All patients were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1-seronegative patients with an active, progressive TB infection and were enrolled at the Department of Thoracic Surgery at St. Petersburg State City TB Hospital, St. Petersburg, Russia. The inclusion criteria for patients entering the study were a TB diagnosis based on TB contact, clinical symptoms (including severe weight loss, >8 weeks of productive cough, and hemoptysis), and typical X-ray findings and histopathology; in addition, patients that were M. tuberculosis positive as determined by direct microscopy, culturing, or PCR (Cobas Amplicor M. tuberculosis test; Roche) were included (Table 1). Surgery on all 19 patients included in the study was performed in order to limit disease progression in patients who had clinical symptoms of active TB and who did not respond to treatment with conventional anti-TB drugs. All 19 TB patients had recently been treated for more than 6 months with a combination therapy including at least five first- and second-line drugs (Table 1). Three tissue biopsies from each patient were sampled; two of these biopsies were from a gross TB lesion, and one was from the distal, macroscopically normal area of the resected lung. Pathological biopsies were obtained primarily from the granulomatous fibrotic tissue areas of the resected lung, whereas distal lung parenchyma was obtained from visually uninvolved lung tissue at the margin of the pathological TB lesion. The distinction between a pathological TB lesion and macroscopically normal lung parenchyma was made by the surgeon and a TB specialist based on visual examination of the resected lung segments. Histopathological tissue analysis of the TB lesions obtained from each of the 19 patients revealed that the normal structure of the lung parenchyma was destroyed due to a necrotizing granulomatous reaction including epithelioid cells and giant cells, which are morphological characteristics suggestive of TB (Table 1). One of the two biopsies obtained from the TB lesion of each patient was used for direct microscopy and culture of M. tuberculosis, whereas the other biopsy from the TB lesion and the biopsy obtained from distal lung parenchyma were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −85°C for future PCR and immunocytochemical analysis. Lung tissue from patients (n = 10; six males and four females; ages, 60 to 79 years) undergoing lobectomy due to lung malignancy (adenocarcinoma) were used as uninfected controls for immunocytochemical staining. All control subjects were smokers with chronic bronchitis who were cared for at the Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden. Ethical approval was obtained at both hospital sites, and patients were recruited into the study after informed consent.

TABLE 1.

Clinical and bacteriological demographics of TB patientsa

| Patient no. | Genderb | Age (yr) | Time since first TB diagnosis (yr)c | Bacteriological diagnosisd

|

Pathological and anatomical diagnosise

|

Drug treatment (no. of drugs)f | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy (sputum) | Culture (tissue biopsy) | PCR (tissue biopsy) | Histopathology (TB lesion) | X ray | |||||

| 1 | M | 27 | 7 | + | + | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in RLL) | 6 |

| 2 | M | 25 | 3 | + | + | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in LUL) | 7 |

| 3 | M | 30 | 2 | + | + | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in RUL) | 12 |

| 4 | M | 32 | 2 | + | + | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in LUL) | 5 |

| 5 | F | 23 | 1 | + | + | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in RUL) | 8 |

| 6 | F | 48 | 1 | + | + | M. tuberculosis | TB | Non-cavitary TB (IF in LUL) | 5 |

| 7 | M | 30 | 6 | + | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in RUL) | 5 |

| 8 | F | 33 | 2 | + | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in RUL) | 6 |

| 9 | F | 37 | 1 | + | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in RUL) | 9 |

| 10 | M | 54 | 6 | + | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Non-cavitary TB (IF in RUL) | 5 |

| 11 | M | 35 | 2 | + | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Non-cavitary TB (IF in LUL) | 6 |

| 12 | M | 50 | 1 | − | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in RUL) | 7 |

| 13 | F | 24 | 1 | − | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Cavitary TB (FC in LUL) | 9 |

| 14 | M | 39 | 4 | − | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Noncavitary TB (MT in RUL) | 6 |

| 15 | M | 47 | 1 | − | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Noncavitary TB (MT in LUL) | 6 |

| 16 | M | 55 | 1 | − | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Noncavitary TB (IF in RUL) | 5 |

| 17 | M | 35 | 1 | − | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Noncavitary TB (MT in RUL) | 7 |

| 18 | M | 49 | 3 | − | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Noncavitary TB (IF in LUL) | 5 |

| 19 | M | 53 | 1 | − | − | M. tuberculosis | TB | Noncavitary TB (MT in LUL) | 7 |

All patients had clinical symptoms of active pulmonary TB at the time of surgery despite prior treatment with anti-TB drugs. TB diagnosis was based on clinical history, microscopy, culture, PCR, histopathology, and X-ray data.

M, male; F, female.

Time between the first clinical diagnosis of pulmonary TB and the time of surgery. Patients 1, 7, 10, and 14 previously had TB and were clinically cured after the first period of drug treatment, but there was reactivation of TB or reinfection within 1 year before surgery.

Microscopy involved direct microscopy and detection of acid-fast bacilli (Ziehl-Neelsen stain) in induced sputum samples taken at the time of the first clinical diagnosis. Culturing from tissue homogenate of the TB lesions was performed the day after surgery. Tissue sections from the TB lesions were used to verify TB using an M. tuberculosis-specific PCR.

Histopathological analysis of tissue from the TB lesions revealed a granulomatous reaction with giant cells and epithelioid cell clusters suggestive of TB. X-ray analysis of the lung revealed different clinical forms of TB, either cavitary TB or noncavitary TB. The clinical diagnosis was performed according to the guidelines in the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (9th revision). In cavitary TB, a >3-cm cavern with a fibrotic capsule was formed (FC, fibrocavernous TB). In noncavitary TB, there were nodular densities with an elliptical or spherical form, diverse sizes, and discernible contours (MT, multiple tuberculomas) or patchy areas of pulmonary infiltrates with various forms, sizes, and densities (IF, infiltrative TB). RUL right upper lung lobe; LUL, left upper lung lobe; RLL, right lower lung lobe.

The number of anti-TB drugs that each patient was treated with before surgery is shown. The treatments included combinations of more than five of the following anti-TB drugs: rifampin/rifabutin, isoniazid, pyrazinamid, streptomycin, ethambutol, combutol, ethionamid/prothionamide, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, kanamycin, amikacin, fenazid/metazid/prozid, and phthivasid.

Immunohistochemistry and confocal analysis of frozen tissue sections of human lung.

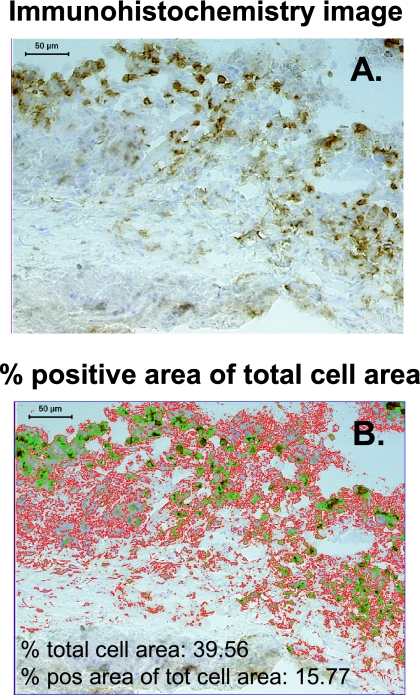

Cryopreserved lung tissue biopsies, embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-TEK; Sakura), were cut into 8-μm-thick sections, mounted on printed microscope slides, and fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Sigma). Immunohistochemical staining was performed as previously described (1); positive staining was developed using a diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector Laboratories), while hematoxylin was used for nuclear counterstaining. In situ imaging and quantification of positive immunostaining were performed using acquired computerized image analysis (Fig. 1) by transferring digital images of the stained tissue samples from a DMR-X microscope (Leica) to a computerized Quantimet 5501W image analyzer (Leica) (6). Single-positive stained cells in 20 to 50 high-power fields were quantified, and protein expression was determined and expressed as the percentage of the positive area in the total relevant cell area (from which fibrotic and necrotic areas of the tissue sections were excluded) using a Qwin 550 software program (Leica Imaging Systems) (2). The total cell area was defined as the nucleated and cytoplasmic area within the tissue. A complete tissue section with a mean size of 6.5 × 106 μm2 was scanned, and each biopsy was assessed twice, which generally resulted in <10% interassay variation. Tissue sections stained with isotype controls or secondary antibodies only were used as negative controls. Two-color staining was performed using indirect immunofluorescence, and double- and single-positive stained cells were quantified by manual counting in 10 high-power fields using a filter-free spectral confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP2 AOBS).

FIG. 1.

Protein expression in tissue quantified using acquired computerized image analysis of immunohistochemistry data. The images show the lymphocyte cuff at the edge of a necrotic granuloma. Positive immunostaining for CD3+ T cells is brown (diaminobenzidine staining), whereas cell nuclei are counterstained blue with hematoxylin. Magnification, ×125. (A) Blank immunohistochemistry image of the field that was analyzed. (B) Overlay image summarizing the analysis of the field in panel A. The positively stained area was marked (green contour line) by setting the threshold for the intensity of the positive staining of the image, whereas the total cellular area (red contour line) was marked by including the positively stained area as well as the nuclear and cytoplasmic area visualized in the field. Artifacts or acellular areas of necrosis were excluded from the analysis using the tissue excluder function of the software program. The field statistics show the percent total cell area and the percent positive area of the total cell area. Positive cells were generally quantified in 20 to 50 high-power fields by scanning the whole tissue section. A mean value for the percent positive area of the total cell area was finally determined. pos, positive; tot, total.

Antibodies.

The primary antibodies were CD3, CD4, and CD8 (BD), elastase/neutrophil, CD68, MAC387, CD1a (Dako), CD1b (Serotec), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (BD/Transduction Laboratories), CD83, DC-SIGN, granzyme A (clone CB9) (BD/Pharmingen), and perforin (clone p16-17) (Mabtech). iNOS was used as an indirect marker for NO production. An affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against human granulysin was kindly provided by Alan Krensky and Carol Clayberger, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA. Biotinylated secondary antibodies, goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G, and swine anti-rabbit F(ab′)2 were purchased from Dako. For dual staining, tissues were stained with rat anti-human CD8 (Serotec) and mouse anti-human granzyme A-perforin, as well as rabbit anti-human granulysin, followed by the appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes).

Real-time PCR analysis of CD8, perforin, and granulysin from tissue sections of frozen human lung.

RNA was extracted from frozen tissue sections using an Ambion RiboPure extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random hexanucleotide primers (Roche). Amplification of ubiquitin C, CD8, perforin, and granulysin cDNA was performed using the ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system and commercial 6-carboxyfluorescein dye-labeled TaqMan MGB probes and primers (Applied Biosystems). Cycle threshold values for CD8, perforin, and granulysin were normalized to the value for ubiquitin C and relative expression by comparing the cycle threshold value for a TB lesion to that for distal lung tissue from the same patient, determined by the Livak method (36). Data are presented below as fold changes in mRNA in a TB lesion compared to the mRNA in either the distal lung or uninfected control lung. Alternatively, a ratio of the relative expression of perforin and granulysin to the relative expression of CD8 is shown for each individual patient.

Statistical analysis.

The data (n = 19) in Fig. 2 passed a normality test (GraphPad Prism-4) and are therefore presented as means ± standard errors. The sample sizes in Fig. 5A to C (n = 6, n = 5, and n = 8) and Fig. 5D to F (n = 10 and n = 9) were considered too small to perform a normality test, and therefore the data are presented as medians ± interquartile ranges. Values from two or three individual experiments are shown. The parametric analysis used to calculate P values in Fig. 2 and 5 included a paired t test or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), whereas the nonparametric analyses used for the data in Fig. 5 included a Kruskal-Wallis test or a Mann-Whitney test. A P value of <0.001 was considered extremely significant, a P value between 0.001 and 0.01 was considered very significant, a P value between 0.01 and 0.05 was considered significant, and a P value of >0.05 was considered not significant. The statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism-4.

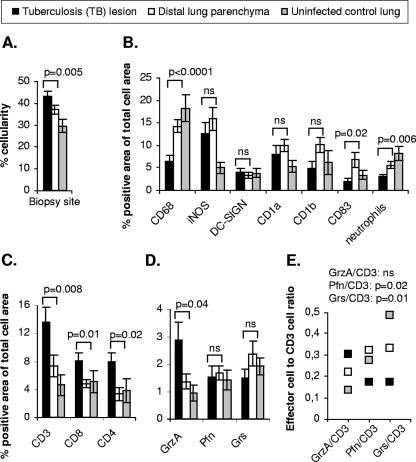

FIG. 2.

Expression and distribution of APCs, neutrophils, T cells, and cytolytic effector molecules in pulmonary tissue as assessed by in situ imaging. (A) Mean cellularity ± standard error of the TB lesions, distal lung parenchyma, and uninfected control lung estimated in the analysis. (B) Mean expression ± standard error of the indicated markers in the TB lesions, the distal lung parenchyma, and uninfected control. The statistical significance of differences in cellularity and protein expression was determined by a paired t test (TB lesion versus distal lung parenchyma). (C and D) Mean expression ± standard error of (C) CD3-, CD8-, and CD4-positive cells and (D) the cytolytic effector molecules granzyme A (GrzA), perforin (Pfn), and granulysin (Grs) in the TB lesions, distal lung parenchyma, and uninfected control. CD4 expression in the distal lung parenchyma was determined by two-color staining of CD3+ CD4+ T cells because this site included CD4+ T cells and CD3− CD4+ macrophages. The statistical significance of differences in protein expression was determined by a paired t test (TB lesion versus distal lung parenchyma). (E) Ratios of granzyme A, perforin, and granulysin expression to CD3 T-cell expression in the TB lesions, distal lung parenchyma, and uninfected control lung. The mean values for paired expression of effectors and CD3 T cells from all individual patients are shown. The statistical significance of differences in the effector cell/CD3 cell ratio among the different clinical groups was determined by one-way ANOVA. ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

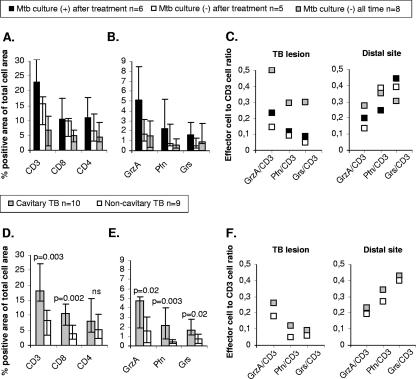

FIG. 5.

Differences in expression of T cells and cytolytic effector molecules in the TB lesions. (A and B) Medians ± interquartile ranges for (A) CD3, CD8, and CD4 and (B) granzyme A (GrzA), perforin (Pfn), and granulysin (Grs) in TB lesions from patients that were culture positive for M. tuberculosis (Mtb) before and after treatment, patients that were culture positive before treatment but negative after treatment, and patients that were consistently culture negative. Differences in protein expression were determined to be not significant using a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. (C) Ratio of granzyme A-, perforin-, and granulysin-expressing cells to CD3 T-cell expression in the TB lesions and distal lung parenchyma. The mean values for paired expression of effector cells and CD3 T cells from M. tuberculosis culture-positive and M. tuberculosis culture-negative patients are shown. (D and E) Median values ± interquartile ranges for (D) CD3, CD8, and CD4 and (E) granzyme A, perforin, and granulysin in TB lesions from patients with either the cavitary or noncavitary form of TB. The statistical significance of differences in protein expression was determined by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. ns, not significant (P > 0.05). (F) Ratio of granzyme A-, perforin-, and granulysin-expressing cells to CD3 T-cell expression in the TB lesions and distal lung parenchyma. The mean values for paired expression of effector cells and CD3 T cells from patients with cavitary TB and noncavitary TB are shown.

RESULTS

Chronic TB infection is associated with persistent inflammation in the lung.

The demographics of the patients are outlined in Table 1. Despite extensive chemotherapy, all patients were PCR positive for M. tuberculosis and had clinical symptoms of active TB (Table 1). Therefore, although the patients were not tested for drug resistance, we considered it very likely that they were infected with multidrug-resistant TB, based on the poor clinical response to extensive medical treatment (>70% of the patients were treated with more than five drugs) (Table 1). In the cohort of patients with verified chronic pulmonary TB infection, the clinical form of TB was diagnosed as either cavitary TB (>3-cm cavern with a fibrotic capsule formed; n = 10) or noncavitary TB (multiple tuberculomas or infiltrative TB; n = 9) (Table 1). Cavitary TB was considered to include extensive tissue destruction with formation of a fibrotic cavern, whereas noncavitary TB included limited fibrotic processes (44). In situ imaging of cryopreserved tissue sections was performed with lung biopsies from the TB lesions, as well as from the macroscopically normal distal lung parenchyma. Thus, we compared paired observations obtained from different sites of the infected lung of the same individual. In addition, uninfected lung biopsies from 10 patients with restricted inflammation were used as controls. The cellularity and positive immunostaining in the tissue sections were quantified using acquired computerized image analysis (Fig. 1). We found that the mean cellularity in pulmonary tissue obtained from the TB lesions was significantly higher than that in the distal lung parenchyma and uninfected control lung (Fig. 2A). Thus, cellular infiltration was increased in the diseased areas of a chronically TB-infected lung. In order to characterize the cellular infiltrate and also measure the levels of immune activation in the different anatomical locations of the TB-infected lung, we analyzed the presence and distribution of APCs, CD3+, CD8+, and CD4+ T cells, and cytolytic effector molecules characteristic of mycobacterial immunity (Fig. 2B to D). There were significant reductions in the levels of CD68+ macrophages and also neutrophils in the TB lesions compared to the levels in distal lung parenchyma or uninfected control tissue (Fig. 2B). DC-SIGN+ dendritic cells were found at comparable levels in all biopsies, while a slight increase in the level of CD1a+-, CD1b+-, and CD83+-expressing cells was evident in the TB-infected lungs compared to control lungs (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the expression of iNOS was significantly higher (P = 0.04) in TB-infected tissue than in uninfected control lung (Fig. 2B). Phenotypic double staining revealed that CD68+ macrophages were the primary source of iNOS (data not shown). Thus, in spite of a significant decrease in the level of CD68+ macrophages, there was a relative increase in the expression of iNOS in the TB lesions (iNOS, 12.7%; CD68, 6.5%) compared to distal lung parenchyma (iNOS, 15.8%; CD68, 14.3%) (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, we observed that the levels of CD3+, CD8+, and CD4+ T cells were significantly higher in the TB lesions than at other sites (Fig. 2C), whereas CD56+ NK cells never accounted for more than 0.1% of the total cellular area in any of the lung biopsies collected (data not shown). Thus, the increased cellularity in the TB lesions was predominately caused by accumulation of CD3+ and CD8+ T cells and CD4-expressing cells at this site. The statistical significance of differences in cellularity and protein expression was determined by a paired t test (TB lesion versus distal lung parenchyma) (Fig. 2A to C) or a one-way ANOVA (TB lesion versus distal lung parenchyma versus uninfected control lung; for cellularity, P = 0.01; for CD68, P < 0.0001; for iNOS, P = 0.01; for neutrophils, P = 0.003; for CD3, CD8, and CD4, P = 0.02).

Decreased expression of perforin- and granulysin-expressing cells in TB lesions from infected lungs despite elevated levels of CD3+ T cells.

Next, we evaluated tissue expression of cytolytic granule-associated effector molecules, such as granzyme A and perforin, as well as the antimicrobial protein granulysin. There was significant up-regulation of granzyme A in the TB lesions, whereas the levels of perforin- and granulysin-expressing cells were not increased but were comparable to the levels in distal lung parenchyma and uninfected control lungs, respectively (Fig. 2D). The statistical significance of differences in the expression of cytolytic effector molecules was determined by a paired t test (TB lesions versus distal lung parenchyma) (Fig. 2D) or one-way ANOVA (TB lesion versus distal lung parenchyma versus uninfected control lung; for granzyme A, P = 0.02; for perforin and granulysin, P > 0.05 [not significant]). Thus, although there was a significantly higher level of CD3+ T cells in the TB lesions (Fig. 2C), the levels of perforin- and granulysin-expressing cells decreased (Fig. 2E). This generated a ratio of perforin- and granulysin-expressing cells to total CD3+ T cells that was significantly altered in the TB lesions compared to the ratios for the distal sites and uninfected control lungs (Fig. 2E).

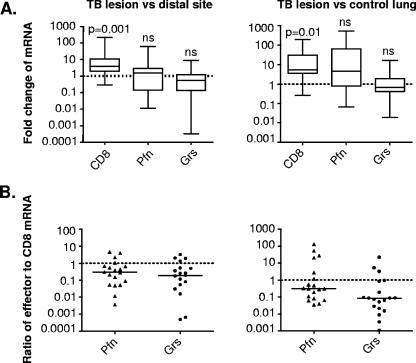

To investigate whether low expression of perforin and granulysin in the TB lesions was evident at the transcriptional level, we quantified mRNA levels for CD8, perforin, and granulysin as a measurement complementary to protein expression detected at the single-cell level. The fold change in the mRNA levels in the TB lesions was compared to that in the distal lung tissue and to that in uninfected control lung tissue. In agreement with the protein analysis (Fig. 2C and D), there was a significant increase in the mRNA level for CD8, whereas the mRNA levels for perforin and granulysin were unchanged and reduced, respectively, in the TB lesions compared to both the distal sites and uninfected control lungs (Fig. 3A). As expected, the relative expression of granzyme A mRNA was significantly higher (P = 0.001) in the TB lesions than in the distal lung parenchyma and control lungs (data not shown). Furthermore, the relative expression or ratio of perforin and granulysin mRNA to CD8 mRNA revealed that there was lower per cell expression of effectors in the TB lesions than in the distal lung sites and uninfected lungs (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

mRNA expression of CD8, perforin, and granulysin as assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. (A) Fold changes in the ratios of CD8, perforin (Pfn), and granulysin (Grs) mRNA to ubiquitin C mRNA in the TB lesions compared to those in distal lung tissue or uninfected control lung tissue. The data are presented as a box and whisker plot. The statistical significance of differences in mRNA levels was determined by a paired t test (TB lesion versus distal lung parenchyma) or an unpaired t test (TB lesion versus uninfected control lung). ns, not significant (P > 0.05). (B) Ratios of relative expression of perforin and granulysin to CD8 mRNA levels in the TB lesions compared to those in the distal sites or uninfected control lung for individual patients. The data are expressed as the ratios of effector levels to CD8 mRNA levels in a scatter plot, and the solid bars indicate the medians.

Granulomas in gross TB lesions have few CD8+ T cells and perforin- and granulysin-expressing cells.

Giant cells (Fig. 4A, left panels) and granulomas (Fig. 4A, middle panels) are both characteristic and well-defined morphological structures of TB that could be observed in all tissue samples from the TB lesions. Histopathological examination of the lung tissue revealed a typical granulomatous reaction in the TB lesions, consisting of confluent as well as individual, distinct granulomas (Fig. 4A, middle panels) of different sizes. However, despite the increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells in the TB lesions, CD8+ T cells could be detected only in the periphery of the granulomas (Fig. 4A, middle panels), which contained many CD3+ and CD4+ T cells (data not shown). In agreement with the altered protein expression of cytolytic effector molecules in the TB lesions, we found that local expression of perforin and granulysin was low in granulomas dispersed within the TB lesions (Fig. 4A, middle panels). In contrast, granzyme A was up-regulated in the granulomas (Fig. 4A, middle panels), as well as the rest of the lesions. Immunostaining of distal lung parenchyma revealed a normal pulmonary architecture without inflammatory infiltrates or a granulomatous reaction (Fig. 4A, right panels).

FIG. 4.

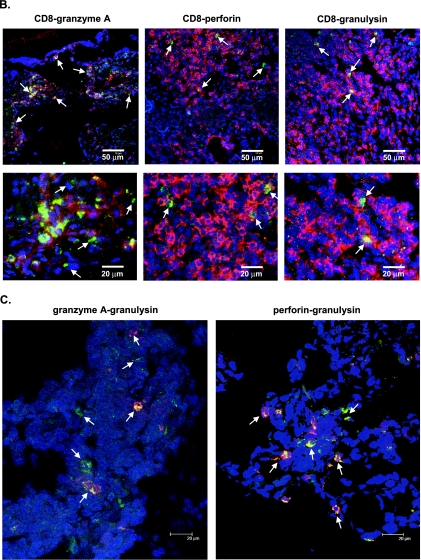

Immunohistochemical analysis and confocal microscopy showing local distribution and coexpression of CD8+ T cells, granzyme A, perforin, and granulysin. (A) Giant cell (GC) formation (left panels) and a granuloma (middle panels) as characteristic morphological structures in a TB lesion. CD8-, granzyme A-, perforin-, and granulysin-expressing cells in serial sections of an area outside a distinct granuloma (left panels) or inside a distinct granuloma (middle panels) within a TB lesion were compared to cells in distal lung parenchyma (right panels) from a patient with cavitary TB. The arrows indicate positive cells (brown diaminobenzidine staining). Cell nuclei were counterstained blue with hematoxylin. Magnification of giant cell images, ×250; magnification of granuloma and distal lung images, ×125. (B) Two-color confocal immunofluorescent staining of CD8 (red; Alexa-633) and the granular markers granzyme A, perforin, and granulysin (green; Alexa-488) in the TB lesion from a patient with cavitary TB. The CD8+ T-cell-rich area shown facilitates visualization of CD8+ T cells that express the cytolytic effector molecules (see Table 2). Single-positive cells are red or green, whereas double-positive cells are yellow. The arrows in the upper panels indicate double-positive cells, and the arrows in the lower panels indicate granzyme A single-positive cells (green) and CD8-perforin or CD8-granulysin double-positive cells (yellow). Magnification for upper panels, ×125. The lower panels are close-up views of selected areas from the upper panels. (C) Dual staining of granulysin (red; Alexa-594) and granzyme A or perforin (green; Alexa-488) in the TB lesion from a patient with cavitary TB. Magnification, ×600. The arrows indicate both single-positive cells (green or red) and double-positive cells (yellow).

CD8+ T cells are the main producers of cytolytic effector molecules in the TB lesions.

Two-color staining and confocal microscopy showed that the great majority of granulysin- and perforin-expressing cells in the TB lesions belonged to the CD8+ T-cell population (Table 2 and Fig. 4B). However, the overall coexpression of both molecules was low among CD8+ T cells, whereas the expression of granzyme A was considerably higher in the CD8+ T-cell population (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, perforin and granulysin were typically coexpressed in the CD8+ T cells both in the TB lesions (Fig. 4C) and in the distal lung tissue (data not shown). Most perforin- and granulysin-expressing cells also coexpressed granzyme A (Fig. 4C). Apart from these double-positive cells, an additional CD8 T-cell population presumably contributed to granzyme A expression in the TB lesions as only approximately 70% of the granzyme A-expressing cells were CD8+ T cells (Table 2 and Fig. 4B).

TABLE 2.

Characterization of CD8+ T cells in pulmonary tissue from TB lesions of M. tuberculosis-infected patients

| Marker | % CD8+ T-cell expressiona | % Expression in CD8+ T cellsb |

|---|---|---|

| Granzyme A | 1.7 | 70 |

| Perforin | 0.1 | 87 |

| Granulysin | 0.2 | 93 |

Mean percentage of total CD8+ T cells that expressed each cytolytic marker in the TB lesions as assessed by two-color staining and confocal microscopy analysis.

Mean percentage of each cytolytic marker that was expressed by CD8+ T cells in the TB lesions as assessed by two-color staining and confocal microscopy analysis.

Differences in immune activation in the TB lesions: comparisons of M. tuberculosis culture-positive and M. tuberculosis culture-negative patients or patients with cavitary TB and patients with noncavitary TB.

Culturing revealed that 11 patients were M. tuberculosis positive prior to the initiation of anti-TB treatment, and six of these patients remained culture positive for M. tuberculosis after the treatment period (Table 1). Eight TB patients were consistently culture negative (Table 1). Interestingly, expression of iNOS in the TB lesions was twice as high (16.4% versus 8.6 and 7.1%, respectively) among patients that remained M. tuberculosis culture positive after anti-TB treatment as among culture-negative patients, despite similar levels of CD68+ macrophages in all these groups (6.9% versus 6.8 and 5.4%, respectively). Moreover, the total cellularity was elevated in M. tuberculosis culture-positive patients compared to the culture-negative patients (data not shown). Accordingly, the expression of CD3+ T cells (Fig. 5A), as well as cytolytic effectors (Fig. 5B), was elevated in TB lesions from patients who remained culture positive even after anti-TB treatment. However, the ratio of cells expressing cytolytic effector molecules to CD3+ T cells was lower in the TB lesions from culture-positive patients than in the TB lesions from culture-negative patients (Fig. 5C). Importantly, the ratio of CD3+ T cells expressing perforin or granulysin was two to threefold higher at the distal site than in the TB lesions (Fig. 5C).

Interestingly, most of the patients that remained M. tuberculosis culture positive after anti-TB treatment had cavitary TB, while most culture-negative patients had noncavitary TB. Indeed, we found that the cytolytic T-cell response differed for these clinical forms of TB since the expression of both CD3+ and CD8+ T cells and the expression of cytolytic effector molecules were significantly increased in patients with cavitary TB compared to patients with noncavitary TB (Fig. 5D and E). In accordance with the results described above for M. tuberculosis culture-positive and -negative patients, the ratio of effector cells to CD3+ T cells was higher for the distal sites than for the TB lesions in patients with cavitary TB as well as in patients with noncavitary TB (Fig. 5F). In contrast, there was no significant difference in iNOS expression when patients with cavitary TB and patients with noncavitary TB were compared (12.9 versus 12.4%), whereas the proportion of CD68+ macrophages was slightly lower in patients with cavitary TB than in patients with noncavitary TB (5.2 versus 7.9%).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study in which an attempt was made to compare T-cell expression of granule-associated cytolytic effector molecules at the site of infection in human pulmonary TB to the clinical progression of disease. This report describes a unique clinical cohort of chronically TB-infected patients in whom we studied the expression of cytolytic effector molecules and antimicrobial peptides at the single-cell level in situ. We provide evidence that both perforin- and granulysin-expressing cells were scarce in chronic pulmonary TB lesions despite significant infiltration of CD3+ T cells. The local deficiency in perforin and granulysin was evident at both the protein and mRNA levels. Perforin- and granulysin-expressing CD3+ T cells were particularly scarce in granulomas and were detected at two- to threefold-lower ratios in the TB lesions than at the distal sites of the TB-infected lungs and in the uninfected control lungs. A reduction in the level of perforin and granulysin in relation to the level of granzyme A was evident in patients with persistent clinical disease, while higher per cell expression of perforin and granulysin was associated with bacteriological control. Thus, these results suggest that perforin and granulysin could be used as markers or correlates of immune protection in human TB.

Previously, studies using peripheral blood mononuclear cells from blood have described coordinated expression of granule-associated cytolytic effector molecules that correlates with control of TB infection in humans. Reports have provided evidence that increased mRNA expression of perforin, granzyme, and granulysin in human CD3+ T cells is associated with inhibition of mycobacterial growth in macrophages (73). γ/δ T cells that express both perforin and granulysin also contribute to a protective host response in human TB (17, 18). In addition, a subset of human CD8+ T cells was shown to coexpress CCL5, perforin, and granulysin, which resulted in enhanced recruitment and killing of M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages (59). Interestingly, an improved capacity of human CD8+ T cells to lyse M. tuberculosis-infected monocytes was associated with higher expression of perforin and granulysin but not Fas ligand (47). Antibody blockage of the granule exocytosis pathway, but not Fas/FasL interactions, in human T cells dramatically decreased their lytic activity against M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages (10) and thus increased the intracellular growth of bacteria (18). One of the few studies that investigated human CTL responses at the site of mycobacterial infection described a reduced frequency of granulysin-expressing T cells in skin from patients with a severe form of disseminated Mycobacterium leprae infection (40). Similarly, we found impaired expression of both perforin and granulysin at the site of pulmonary TB infection. The importance of granzymes in reducing the viability of intracellular mycobacteria has been investigated less well. Here, our results suggest that progression of clinical disease among chronic TB patients occurred despite an increased level of granzyme A-expressing T cells in the lesions. Elevated tissue expression of granzyme A alone may not be sufficient to reduce the bacterial burden. Instead, a rise in granzyme A expression together with deficient up-regulation of perforin and granulysin in CD3+ T cells in the TB lesions may contribute to the severity of the disease. It has been shown that granzyme A/B may promote immune pathology and tissue destruction in a number of different disease conditions (8, 20, 31), perhaps by induction and extracellular release of proinflammatory cytokines such as alpha interferon (IFN-α), tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-1 (IL-1).

Although a crucial role for the granule-mediated pathway of CTL killing has also been confirmed in mouse TB, some of the results generated from the use of experimental TB in mice suggest that granule-associated effector molecules are not very important. Perforin and granzyme knockout mice maintain most of the capacity to control a pulmonary TB infection (13), whereas Fas and FasL knockout mice do not control M. tuberculosis growth in the chronic phase of infection (65). However, other studies have demonstrated that perforin knockout mice have increased susceptibility to systemic TB infection (58), whereas the absence of FasL did not alter the course of experimental infection compared to that in wild-type mice (43). Interestingly, in both perforin and FasL knockout mice there appears to be compensatory activation of cytokine genes, since in these mice there was a three- to fivefold increase in the mRNA levels of IL-10, IL-12p35, IL-6, and IFN-γ (33). Presumably, this cytokine response could compensate for the lack of perforin as well as FasL. Importantly, mice lack the antimicrobial molecule granulysin, which again indicates that mouse TB is regulated differently than human TB.

While many reports have emphasized the importance of M. tuberculosis-specific CD4+ T cells (26) in the control of infection (49, 51, 53), M. tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells can also be found at elevated frequencies in the lungs following infection with M. tuberculosis (27, 28). Whereas CD4+ T cells are primarily engaged in cytokine production and Fas/FasL-mediated immune regulation, CD8+ T cells are mainly responsible for IFN-γ production and the induction of granule-mediated cytolytic mechanisms upon infection with TB (15, 53, 57). There are extensive experimental data that highlight the role of CD8+ T cells in M. tuberculosis infection, particularly in the chronic phase (24, 62). The mean survival times for CD8-deficient mice infected with M. tuberculosis were significantly shorter than those for wild-type animals (58). In addition, antibody depletion of CD8+ T cells in mice severely impaired the capacity to control subsequent infection with M. tuberculosis (37), whereas adoptive transfer with CD8+ T cells confers protection in mice (42). Furthermore, M. tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T-cell lines were capable of lysing M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages in vitro, suggesting that CD8+ T cells with antigen-specific cytolytic potential are generated during clinical TB (16). Here, we demonstrated that the levels of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were increased in the TB lesions of infected patients compared to distal sites and uninfected controls. However, CD8+ T cells were the primary producers of granzyme A, perforin, and granulysin. Confocal microscopy of tissue sections obtained from TB lesions provided evidence that there was coexpression of granulysin and perforin in the CD8+ T cells, while very few of these cells had the CD4+ phenotype (<10%). In addition, granzyme A expression was also seen in the perforin-positive, granulysin-positive CD8+ T cells, even though approximately 30% of the granzyme A-positive cells were not CD8+ T cells. It is possible that CD8− NK T-cell subsets contributed to the pool of granule-containing effectors. However, the frequency of CD56+ NK cells in the lung tissue was particularly low (<0.1%), and thus it is unlikely that these cells contributed to the pool of granzyme A-expressing cells.

While granzyme A has not been implicated in direct killing of M. tuberculosis bacilli, a skewed balance of perforin- and granulysin-expressing cells may result in reduced killing of intracellular M. tuberculosis (19, 59, 60). We observed a reduced ratio of perforin- and granulysin-expressing CD3+ T cells in the TB lesions compared to the ratios at the distal sites and in normal lungs. Deficient CTL effector molecule responses have been described for HIV, where abundant expression of granzyme A but low levels of perforin were found in CD8+ T cells in the gut (55) and lymphoid tissue (2), as well as in tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells, of HIV-infected patients. It has been suggested that this dissociation between granzyme A and perforin expression may result in impaired CTL activity since perforin is required for intracellular endosome transportation of granzymes in target cells. Accordingly, a selective absence of CD8+ T cells, as well as cells armed with perforin and granulysin at the site of bacterial replication in the TB lesions, may limit contact-dependent killing and host protection. The lack of an appropriate cytolytic response inside the granuloma could result in persistence of bacteria sheltered in granuloma-associated macrophages. Hence, whereas inadequate expression of perforin and granulysin in granules of CTLs could be partially responsible for disease progression, the anatomical organization of the CTL response in relation to infected cells may also be important. Alternatively, host cells within the granuloma are killed via the Fas/FasL pathway, which has previously been shown to be inefficient in killing intracellular mycobacteria in experimental settings (15, 61). In this way, extracellular M. tuberculosis could continue to grow in the caseous necrotic center of the granuloma and eventually propagate the infection (21, 68).

Polyfunctional CD8+ T cells (coexpressing IFN-γ, MIP-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-2, and markers for degranulation; CD107a) have recently been identified as important functional cells in the generation of proper immunity against intracellular infections (5). Thus, several factors presumably influence and determine the quality and magnitude of the CTL response. Inappropriate cytokine production or costimulation, due to a lack of help from APCs and CD4+ T cells, may result in deficient CD8+ CTL development (53). It is also possible that highly activated macrophages inhibit T-cell activation during mycobacterial infections (38, 56). Alternatively, apoptosis of alveolar macrophages and monocytes has been described as a consequence of M. tuberculosis infection (7). It has recently been demonstrated that dendritic cells phagocytose apoptotic vesicles from mycobacterium-infected macrophages, resulting in cross-priming of CD8+ T cells (72). However, insufficient cross-priming in chronic TB patients may result in reduced stimulation of CD8+ T cells. Another explanation for low perforin and granulysin expression could be degranulation of CD8+ T cells. However, this is unlikely as we found a direct correlation between low mRNA and protein contents in the tissue samples. Furthermore, we could not detect significant extracellular deposition of perforin or granulysin in the tissue sections, which indirectly excluded degranulation. Physiological release of granzyme A and perforin should lead to the presence of granzyme A in a nuclear location in the target cells (4). Instead, the cellular expression of granzyme A in the tissues was polarized and granular, indicating that granzyme A had not entered the target cells properly.

Accumulation and activation of regulatory T cells (Treg cells) may also disturb the normal immunological balance by suppressing the expansion of M. tuberculosis-specific immune responses and therefore contributing to the persistence of a chronic pulmonary TB infection. It was recently reported that elevated numbers of naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells (45), as well as FoxP3+ Treg cells (25) and CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg cells (11), were found in the blood and at the site of infection in TB patients. Consistent with these data, patients with chronic, progressive HIV infection have been shown to have significantly increased expression of FoxP3+ Treg cells in the lymphoid tissue and gut, concurrent with deficient perforin expression (3). However, a potential role for Treg cells in the down-regulation of cytolytic and antimicrobial activity and expression of perforin and granulysin at the local site of TB infection remains to be determined.

The patients included in the current study failed to respond to treatment with conventional anti-TB drugs and thus retained clinical symptoms and exhibited active disease progression. Our results confirmed that chronic, incurable TB was associated with persistent inflammation, including excessive expression of iNOS (39, 52). Interestingly, in contrast to the low expression of perforin and granulysin in CD3+ T cells, the relative expression of iNOS in CD68+ macrophages was higher in the TB lesions than in the distal lung parenchyma. Yet, although iNOS up-regulation was evident in most TB cases, high iNOS expression did not correlate with bacteriological control. Thus, NO may contribute to TB control but is not solely responsible for the outcome. Persistent inflammation in the TB lesions was also driven by increased infiltration of CD3+ T cells expressing granzyme A, especially in patients with cavitary TB who remained culture positive for M. tuberculosis even after anti-TB treatment. Consistent with this notion, it was recently demonstrated that lung tissue from patients with active cavitary TB was enriched with lymphocytes and contained fewer macrophages than lung tissue from patients with latent TB in nonprogressive tuberculomas (67). A decline in the number of activated macrophages and a concurrent rise in the number of T cells may be characteristic of advanced and severe forms of TB disease. Insufficient up-regulation of perforin and granulysin by CTLs in the lesions may have contributed to the lack of appropriate anti-TB activity, whereas the presence of inflammatory mediators and extracellular granzyme A in the granulomatous environment could presumably be involved in subsequent steps leading to cavity formation. Both host and bacterial factors have been shown to influence the development of cavitary and noncavitary forms of TB disease. However, pulmonary cavities typically develop late in the course of disease and originate from large, mature, and caseous granulomas that are closely associated with extensive tissue destruction. Thus, sustained bacterial replication during chronic disease may provoke aberrant immune activation, including uncoordinated expression of cytolytic effector molecules that fail to control infection and disease progression.

This report illustrates a quantitative difference as well as a qualitative difference in the expression of immune cells and cytolytic granule-released effectors in TB lesions compared to the expression in distal lung parenchyma from patients with chronic TB. The diminished expression of perforin and granulysin may result in impaired CTL activity, primarily in granuloma-associated CTLs in the TB lesions. We propose that perforin and granulysin could be used as immune correlates of protection upon evaluation of polyfunctional CTL responses in human TB. This knowledge is essential for the construction of more effective TB vaccines, as well as for the implementation of immunotherapies that could strengthen immunity and prevent disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vladimir Zhemkov, Albert Zaichik, and Leonid Churilov at the St. Petersburg State City Anti-TB Dispensary, Gennadiy Zubov at the St. Petersburg State City Anti-TB Hospital, and Lidiya Steklova at the St. Petersburg State City Bacteriological Laboratory, St. Petersburg, Russia, for excellent scientific and practical support. We thank Anders Sönnerborg and the personnel at the P3 safety laboratory at the Department of Clinical Virology and Carl-Gustav Hillebrant at the Thorax Clinic at Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge for providing scientific and technical assistance. We are also grateful to Anette Hofmann at the Center for Infectious Medicine for excellent technical help with confocal microscopy. We thank Anna Norrby-Teglund and Karin Loré at the Center for Infectious Medicine, Karolinska Institiutet, for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Karolinska Institute Research Training Programme (KIRT), VINST/VINNOVA, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, and the SIDA/SAREC Foundation.

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, J., J. Abrams, L. Bjork, K. Funa, M. Litton, K. Agren, and U. Andersson. 1994. Concomitant in vivo production of 19 different cytokines in human tonsils. Immunology 83:16-24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, J., H. Behbahani, J. Lieberman, E. Connick, A. Landay, B. Patterson, A. Sonnerborg, K. Lore, S. Uccini, and T. E. Fehniger. 1999. Perforin is not co-expressed with granzyme A within cytotoxic granules in CD8 T lymphocytes present in lymphoid tissue during chronic HIV infection. AIDS (London) 13:1295-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson, J., A. Boasso, J. Nilsson, R. Zhang, N. J. Shire, S. Lindback, G. M. Shearer, and C. A. Chougnet. 2005. The prevalence of regulatory T cells in lymphoid tissue is correlated with viral load in HIV-infected patients. J. Immunol. 174:3143-3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson, J., S. Kinloch, A. Sonnerborg, J. Nilsson, T. E. Fehniger, A. L. Spetz, H. Behbahani, L. E. Goh, H. McDade, B. Gazzard, H. Stellbrink, D. Cooper, and L. Perrin. 2002. Low levels of perforin expression in CD8+ T lymphocyte granules in lymphoid tissue during acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1355-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betts, M. R., M. C. Nason, S. M. West, S. C. De Rosa, S. A. Migueles, J. Abraham, M. M. Lederman, J. M. Benito, P. A. Goepfert, M. Connors, M. Roederer, and R. A. Koup. 2006. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 107:4781-4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjork, L., T. E. Fehniger, U. Andersson, and J. Andersson. 1996. Computerized assessment of production of multiple human cytokines at the single-cell level using image analysis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 59:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bocchino, M., D. Galati, A. Sanduzzi, V. Colizzi, E. Brunetti, and G. Mancino. 2005. Role of mycobacteria-induced monocyte/macrophage apoptosis in the pathogenesis of human tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 9:375-383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buzza, M. S., L. Zamurs, J. Sun, C. H. Bird, A. I. Smith, J. A. Trapani, C. J. Froelich, E. C. Nice, and P. I. Bird. 2005. Extracellular matrix remodeling by human granzyme B via cleavage of vitronectin, fibronectin, and laminin. J. Biol. Chem. 280:23549-23558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caccamo, N., S. Meraviglia, C. La Mendola, G. Guggino, F. Dieli, and A. Salerno. 2006. Phenotypical and functional analysis of memory and effector human CD8 T cells specific for mycobacterial antigens. J. Immunol. 177:1780-1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canaday, D. H., R. J. Wilkinson, Q. Li, C. V. Harding, R. F. Silver, and W. H. Boom. 2001. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells kill intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a perforin and Fas/Fas ligand-independent mechanism. J. Immunol. 167:2734-2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, X., B. Zhou, M. Li, Q. Deng, X. Wu, X. Le, C. Wu, N. Larmonier, W. Zhang, H. Zhang, H. Wang, and E. Katsanis. 2007. CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells suppress Mycobacterium tuberculosis immunity in patients with active disease. Clin. Immunol. 123:50-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, Z. W. 2005. Immune regulation of γδ T cell responses in mycobacterial infections. Clin. Immunol. 116:202-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper, A. M., C. D'Souza, A. A. Frank, and I. M. Orme. 1997. The course of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in the lungs of mice lacking expression of either perforin- or granzyme-mediated cytolytic mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 65:1317-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dannenberg, A. M., Jr. 1991. Delayed-type hypersensitivity and cell-mediated immunity in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Immunol. Today 12:228-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De La Barrera, S. S., M. Finiasz, A. Frias, M. Aleman, P. Barrionuevo, S. Fink, M. C. Franco, E. Abbate, and C. S. M. del. 2003. Specific lytic activity against mycobacterial antigens is inversely correlated with the severity of tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 132:450-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Libero, G., I. Flesch, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1988. Mycobacteria-reactive Lyt-2+ T cell lines. Eur. J. Immunol. 18:59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dieli, F., G. Sireci, N. Caccamo, C. Di Sano, L. Titone, A. Romano, P. Di Carlo, A. Barera, A. Accardo-Palumbo, A. M. Krensky, and A. Salerno. 2002. Selective depression of interferon-gamma and granulysin production with increase of proliferative response by Vγ9/Vδ2 T cells in children with tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1835-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieli, F., M. Troye-Blomberg, J. Ivanyi, J. J. Fournie, A. M. Krensky, M. Bonneville, M. A. Peyrat, N. Caccamo, G. Sireci, and A. Salerno. 2001. Granulysin-dependent killing of intracellular and extracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Vγ9/Vδ2 T lymphocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1082-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst, W. A., S. Thoma-Uszynski, R. Teitelbaum, C. Ko, D. A. Hanson, C. Clayberger, A. M. Krensky, M. Leippe, B. R. Bloom, T. Ganz, and R. L. Modlin. 2000. Granulysin, a T cell product, kills bacteria by altering membrane permeability. J. Immunol. 165:7102-7108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faria, D. R., K. J. Gollob, J. Barbosa, Jr., A. Schriefer, P. R. Machado, H. Lessa, L. P. Carvalho, M. A. Romano-Silva, A. R. de Jesus, E. M. Carvalho, and W. O. Dutra. 2005. Decreased in situ expression of interleukin-10 receptor is correlated with the exacerbated inflammatory and cytotoxic responses observed in mucosal leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun. 73:7853-7859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fenhalls, G., L. Stevens, L. Moses, J. Bezuidenhout, J. C. Betts, P. van Helden, P. T. Lukey, and K. Duncan. 2002. In situ detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcripts in human lung granulomas reveals differential gene expression in necrotic lesions. Infect. Immun. 70:6330-6338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn, J. L., and J. Chan. 2001. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:93-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gansert, J. L., V. Kiessler, M. Engele, F. Wittke, M. Rollinghoff, A. M. Krensky, S. A. Porcelli, R. L. Modlin, and S. Stenger. 2003. Human NKT cells express granulysin and exhibit antimycobacterial activity. J. Immunol. 170:3154-3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grotzke, J. E., and D. M. Lewinsohn. 2005. Role of CD8+ T lymphocytes in control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Microbes Infect. 7:776-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyot-Revol, V., J. A. Innes, S. Hackforth, T. Hinks, and A. Lalvani. 2006. Regulatory T cells are expanded in blood and disease sites in patients with tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173:803-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hervas-Stubbs, S., L. Majlessi, M. Simsova, J. Morova, M. J. Rojas, C. Nouze, P. Brodin, P. Sebo, and C. Leclerc. 2006. High frequency of CD4+ T cells specific for the TB10.4 protein correlates with protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 74:3396-3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irwin, S. M., A. A. Izzo, S. W. Dow, Y. A. Skeiky, S. G. Reed, M. R. Alderson, and I. M. Orme. 2005. Tracking antigen-specific CD8 T lymphocytes in the lungs of mice vaccinated with the Mtb72F polyprotein. Infect. Immun. 73:5809-5816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamath, A., J. S. Woodworth, and S. M. Behar. 2006. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and the development of central memory during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 177:6361-6369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufmann, S. H. 2002. Protection against tuberculosis: cytokines, T cells, and macrophages. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 61(Suppl. 2):54-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keefe, D., L. Shi, S. Feske, R. Massol, F. Navarro, T. Kirchhausen, and J. Lieberman. 2005. Perforin triggers a plasma membrane-repair response that facilitates CTL induction of apoptosis. Immunity 23:249-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koopman, G., P. C. Wever, M. D. Ramkema, F. Bellot, P. Reiss, R. M. Keehnen, I. J. Ten Berge, and S. T. Pals. 1997. Expression of granzyme B by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the lymph nodes of HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kremer, L., J. Estaquier, I. Wolowczuk, F. Biet, J. C. Ameisen, and C. Locht. 2000. Ineffective cellular immune response associated with T-cell apoptosis in susceptible Mycobacterium bovis BCG-infected mice. Infect. Immun. 68:4264-4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laochumroonvorapong, P., J. Wang, C. C. Liu, W. Ye, A. L. Moreira, K. B. Elkon, V. H. Freedman, and G. Kaplan. 1997. Perforin, a cytotoxic molecule which mediates cell necrosis, is not required for the early control of mycobacterial infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 65:127-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewinsohn, D. M., T. T. Bement, J. Xu, D. H. Lynch, K. H. Grabstein, S. G. Reed, and M. R. Alderson. 1998. Human purified protein derivative-specific CD4+ T cells use both CD95-dependent and CD95-independent cytolytic mechanisms. J. Immunol. 160:2374-2379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, B., H. Bassiri, M. D. Rossman, P. Kramer, A. F. Eyuboglu, M. Torres, E. Sada, T. Imir, and S. R. Carding. 1998. Involvement of the Fas/Fas ligand pathway in activation-induced cell death of mycobacteria-reactive human gδ 32 T cells: a mechanism for the loss of gδ 32 T cells in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 161:1558-1567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCT) method. Methods (San Diego) 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller, I., S. P. Cobbold, H. Waldmann, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1987. Impaired resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection after selective in vivo depletion of L3T4+ and Lyt-2+ T cells. Infect. Immun. 55:2037-2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nabeshima, S., M. Nomoto, G. Matsuzaki, K. Kishihara, H. Taniguchi, S. Yoshida, and K. Nomoto. 1999. T-cell hyporesponsiveness induced by activated macrophages through nitric oxide production in mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 67:3221-3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholson, S., G. Bonecini-Almeida Mda, J. R. Lapa e Silva, C. Nathan, Q. W. Xie, R. Mumford, J. R. Weidner, J. Calaycay, J. Geng, N. Boechat, C. Linhares, W. Rom, and J. L. Ho. 1996. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in pulmonary alveolar macrophages from patients with tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 183:2293-2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ochoa, M. T., S. Stenger, P. A. Sieling, S. Thoma-Uszynski, S. Sabet, S. Cho, A. M. Krensky, M. Rollinghoff, E. Nunes Sarno, A. E. Burdick, T. H. Rea, and R. L. Modlin. 2001. T-cell release of granulysin contributes to host defense in leprosy. Nat. Med. 7:174-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okada, S., Q. Li, J. C. Whitin, C. Clayberger, and A. M. Krensky. 2003. Intracellular mediators of granulysin-induced cell death. J. Immunol. 171:2556-2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orme, I. M., and F. M. Collins. 1984. Adoptive protection of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected lung. Dissociation between cells that passively transfer protective immunity and those that transfer delayed-type hypersensitivity to tuberculin. Cell. Immunol. 84:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearl, J. E., I. M. Orme, and A. M. Cooper. 2000. CD95 signaling is not required for the down regulation of cellular responses to systemic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Tuber. Lung Dis. 80:273-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perelman, M. I., and V. P. Strelzov. 1997. Surgery for pulmonary tuberculosis. World J. Surg. 21:457-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribeiro-Rodrigues, R., T. Resende Co, R. Rojas, Z. Toossi, R. Dietze, W. H. Boom, E. Maciel, and C. S. Hirsch. 2006. A role for CD4+ CD25+ T cells in regulation of the immune response during human tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 144:25-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rios-Barrera, V. A., V. Campos-Pena, D. Aguilar-Leon, L. R. Lascurain, M. A. Meraz-Rios, J. Moreno, V. Figueroa-Granados, and R. Hernandez-Pando. 2006. Macrophage and T lymphocyte apoptosis during experimental pulmonary tuberculosis: their relationship to mycobacterial virulence. Eur. J. Immunol. 36:345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samten, B., B. Wizel, H. Shams, S. E. Weis, P. Klucar, S. Wu, R. Vankayalapati, E. K. Thomas, S. Okada, A. M. Krensky, and P. F. Barnes. 2003. CD40 ligand trimer enhances the response of CD8+ T cells to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 170:3180-3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saunders, B. M., and W. J. Britton. 2007. Life and death in the granuloma: immunopathology of tuberculosis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:103-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saunders, B. M., A. A. Frank, I. M. Orme, and A. M. Cooper. 2002. CD4 is required for the development of a protective granulomatous response to pulmonary tuberculosis. Cell. Immunol. 216:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scanga, C. A., V. P. Mohan, K. Tanaka, D. Alland, J. L. Flynn, and J. Chan. 2001. The inducible nitric oxide synthase locus confers protection against aerogenic challenge of both clinical and laboratory strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Infect. Immun. 69:7711-7717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scanga, C. A., V. P. Mohan, K. Yu, H. Joseph, K. Tanaka, J. Chan, and J. L. Flynn. 2000. Depletion of CD4+ T cells causes reactivation of murine persistent tuberculosis despite continued expression of interferon gamma and nitric oxide synthase 2. J. Exp. Med. 192:347-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schon, T., G. Elmberger, Y. Negesse, R. H. Pando, T. Sundqvist, and S. Britton. 2004. Local production of nitric oxide in patients with tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 8:1134-1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serbina, N. V., V. Lazarevic, and J. L. Flynn. 2001. CD4+ T cells are required for the development of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 167:6991-7000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serbina, N. V., C. C. Liu, C. A. Scanga, and J. L. Flynn. 2000. CD8+ CTL from lungs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice express perforin in vivo and lyse infected macrophages. J. Immunol. 165:353-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shacklett, B. L., C. A. Cox, M. F. Quigley, C. Kreis, N. H. Stollman, M. A. Jacobson, J. Andersson, J. K. Sandberg, and D. F. Nixon. 2004. Abundant expression of granzyme A, but not perforin, in granules of CD8+ T cells in GALT: implications for immune control of HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 173:641-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimizu, T., S. Cai, and H. Tomioka. 2005. Roles of reactive nitrogen intermediates and transforming growth factor-beta produced by immunosuppressive macrophages in the expression of suppressor activity against T cell proliferation induced by TCR stimulation. Cytokine 30:7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silva, C. L., and D. B. Lowrie. 2000. Identification and characterization of murine cytotoxic T cells that kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 68:3269-3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sousa, A. O., R. J. Mazzaccaro, R. G. Russell, F. K. Lee, O. C. Turner, S. Hong, L. Van Kaer, and B. R. Bloom. 2000. Relative contributions of distinct MHC class I-dependent cell populations in protection to tuberculosis infection in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4204-4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stegelmann, F., M. Bastian, K. Swoboda, R. Bhat, V. Kiessler, A. M. Krensky, M. Roellinghoff, R. L. Modlin, and S. Stenger. 2005. Coordinate expression of CC chemokine ligand 5, granulysin, and perforin in CD8+ T cells provides a host defense mechanism against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 175:7474-7483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stenger, S., D. A. Hanson, R. Teitelbaum, P. Dewan, K. R. Niazi, C. J. Froelich, T. Ganz, S. Thoma-Uszynski, A. Melian, C. Bogdan, S. A. Porcelli, B. R. Bloom, A. M. Krensky, and R. L. Modlin. 1998. An antimicrobial activity of cytolytic T cells mediated by granulysin. Science 282:121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stenger, S., R. J. Mazzaccaro, K. Uyemura, S. Cho, P. F. Barnes, J. P. Rosat, A. Sette, M. B. Brenner, S. A. Porcelli, B. R. Bloom, and R. L. Modlin. 1997. Differential effects of cytolytic T cell subsets on intracellular infection. Science 276:1684-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sud, D., C. Bigbee, J. L. Flynn, and D. E. Kirschner. 2006. Contribution of CD8+ T cells to control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 176:4296-4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tan, B. H., C. Meinken, M. Bastian, H. Bruns, A. Legaspi, M. T. Ochoa, S. R. Krutzik, B. R. Bloom, T. Ganz, R. L. Modlin, and S. Stenger. 2006. Macrophages acquire neutrophil granules for antimicrobial activity against intracellular pathogens. J. Immunol. 177:1864-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Temmerman, S. T., S. Place, A. S. Debrie, C. Locht, and F. Mascart. 2005. Effector functions of heparin-binding hemagglutinin-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in latent human tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 192:226-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Turner, J., C. D. D'Souza, J. E. Pearl, P. Marietta, M. Noel, A. A. Frank, R. Appelberg, I. M. Orme, and A. M. Cooper. 2001. CD8- and CD95/95L-dependent mechanisms of resistance in mice with chronic pulmonary tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 24:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ulrichs, T., and S. H. Kaufmann. 2006. New insights into the function of granulomas in human tuberculosis. J. Pathol. 208:261-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ulrichs, T., G. A. Kosmiadi, S. Jorg, L. Pradl, M. Titukhina, V. Mishenko, N. Gushina, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2005. Differential organization of the local immune response in patients with active cavitary tuberculosis or with nonprogressive tuberculoma. J. Infect. Dis. 192:89-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ulrichs, T., G. A. Kosmiadi, V. Trusov, S. Jorg, L. Pradl, M. Titukhina, V. Mishenko, N. Gushina, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2004. Human tuberculous granulomas induce peripheral lymphoid follicle-like structures to orchestrate local host defence in the lung. J. Pathol. 204:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ulrichs, T., D. B. Moody, E. Grant, S. H. Kaufmann, and S. A. Porcelli. 2003. T-cell responses to CD1-presented lipid antigens in humans with Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 71:3076-3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang, C. H., C. Y. Liu, H. C. Lin, C. T. Yu, K. F. Chung, and H. P. Kuo. 1998. Increased exhaled nitric oxide in active pulmonary tuberculosis due to inducible NO synthase upregulation in alveolar macrophages. Eur. Respir. J. 11:809-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watson, V. E., L. L. Hill, L. B. Owen-Schaub, D. W. Davis, D. J. McConkey, C. Jagannath, R. L. Hunter, Jr., and J. K. Actor. 2000. Apoptosis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice exhibiting varied immunopathology. J. Pathol. 190:211-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Winau, F., S. Weber, S. Sad, J. de Diego, S. L. Hoops, B. Breiden, K. Sandhoff, V. Brinkmann, S. H. Kaufmann, and U. E. Schaible. 2006. Apoptotic vesicles crossprime CD8 T cells and protect against tuberculosis. Immunity 24:105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Worku, S., and D. F. Hoft. 2003. Differential effects of control and antigen-specific T cells on intracellular mycobacterial growth. Infect. Immun. 71:1763-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang, D., M. S. Pasternack, P. J. Beresford, L. Wagner, A. H. Greenberg, and J. Lieberman. 2001. Induction of rapid histone degradation by the cytotoxic T lymphocyte protease granzyme A. J. Biol. Chem. 276:3683-3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang, J., R. Jiang, H. Takayama, and Y. Tanaka. 2005. Survival of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis involves preventing apoptosis induced by Bcl-2 upregulation and release resulting from necrosis in J774 macrophages. Microbiol. Immunol. 49:845-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]