Abstract

The phage 21 holin, S21, forms small membrane holes that depolarize the membrane and is designated as a pinholin, as opposed to large-hole-forming holins, like Sλ. Pinholins require secreted SAR endolysins, a pairing that may represent an intermediate in the evolution of canonical holin-endolysin systems.

For most phages, the termination of each infection cycle is the strictly programmed and regulated lysis of the host, brought about by two phage-encoded proteins (28). One of these, the endolysin, is capable of degrading the cell wall, while the second, the holin, is a small membrane protein which controls endolysin function. During the assembly of progeny virions, holin molecules accumulate in the cytoplasmic membrane without damaging the host. Then, at a time dictated by their primary structure, holins trigger to disrupt the cytoplasmic membrane. For many phages, like λ and T4, this event releases to the periplasm an endolysin that has accumulated fully folded and enzymatically active in the cytosol. By contrast, phages P1 and 21 encode endolysins that are exported by the host sec system and accumulate in the periplasm as enzymatically inactive proteins tethered to the membrane by an N-terminal SAR (signal anchor-release) domain (25, 26). These SAR endolysins become enzymatically active when their SAR domains exit the membrane to generate the mature, soluble form in the periplasm. This process occurs spontaneously at a low rate but is greatly accelerated when the cytoplasmic membrane is deenergized. Thus, for phages encoding SAR endolysins, holins need only to depolarize the membrane in order to fulfill their role in controlling the timing of lysis. The formation of large membrane lesions like those resulting from Sλ triggering (22) would not be necessary. This raises the possibility that holins serving SAR endolysins may not function with canonical, soluble endolysins to effect host lysis.

R21 expression allows holin-independent lysis by phage λ.

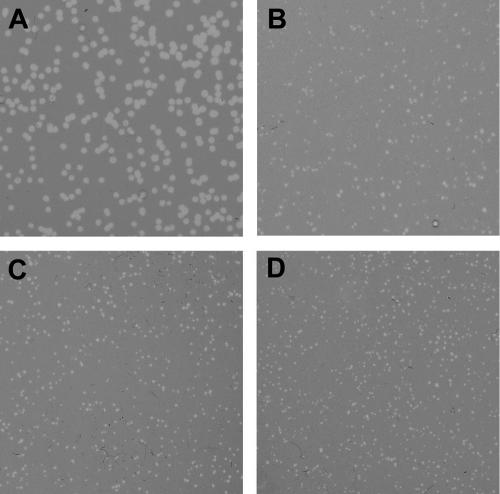

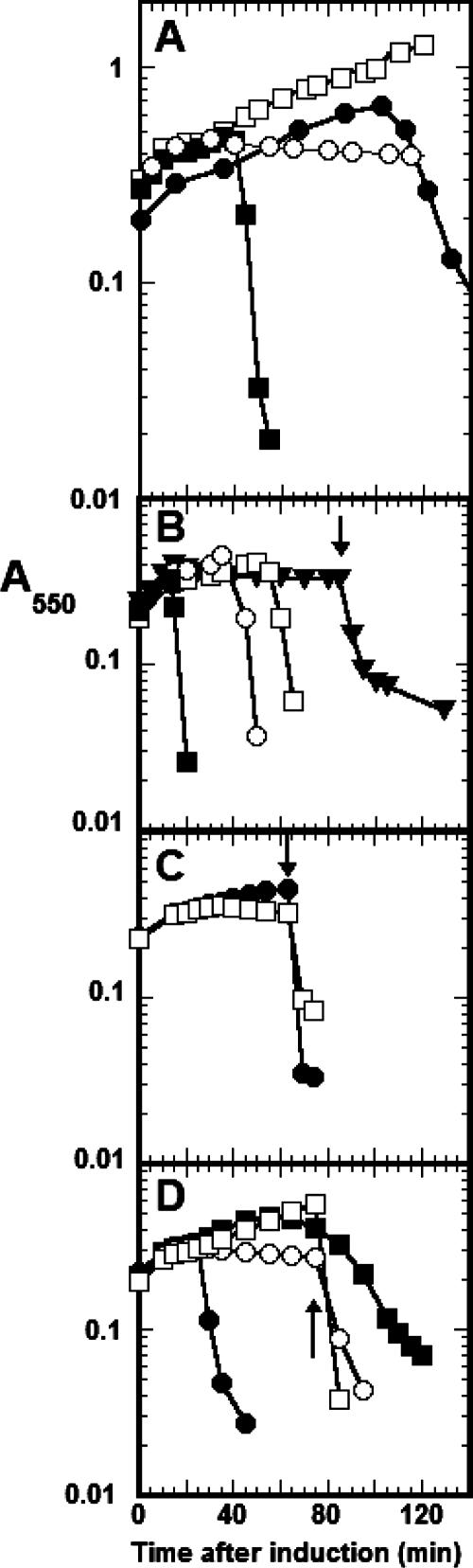

To further characterize the phage 21 holin and endolysin, which are the products of the genes S2168 and R21, respectively (14), we replaced the lysis genes of λ with the lysis genes from phage 21 by homologous recombination between λΔSR and plasmids carrying either S2168R21 or S2168amR21 (Table 1). The recombinant λ S2168R21 formed plaques of uniform size (Fig. 1A) that were slightly smaller than those produced by λ on the same host (not shown). In liquid culture, the lysis of synchronously induced λS2168R21 lysogens exhibited a saltatory character, indicative of the synchronous triggering of the S2168 holin which, in the absence of endolysin function, results in a cessation of growth (Fig. 2A). With nonsuppressor hosts, the behavior of λS2168amR21 was different with respect to both phenotypes. First, the plaques formed by λ S2168amR21 were small and showed a considerable size variation; this heterogeneity persisted when phage from large and small plaques were replated (Fig. 1B to D). Thus, like phage P1 but unlike λ and T4, the S21 holin gene is nonessential for plaque formation (7, 8, 10, 27). Second, for induced λS2168amR21 lysogens, lysis in liquid culture is less saltatory, requiring 30 to 40 min for completion as assessed by monitoring the decrease in culture A550 (Fig. 2A).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, bacteriophages, and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, phage, or plasmid | Genotype and relevant features | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MC4100 | E. coli K-12 F−araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR | 18 |

| MDS12 | MG1655 with 12 deletions, totaling 376,180 nucleotides, including cryptic prophages | 11 |

| MDS12 tonA::Tn10 | tonA::Tn10 transductant of MDS12 | This study |

| Phages and prophages | ||

| λ Δ(SR) | λ stf::cat::tfa cI857 Δ(SR) | 19 |

| λ SamR+ | λcI857 Sam7 (amber in position 56 of S) | Laboratory stock |

| λ S+Ram | λcI857 Ram54am60 (ambers in positions 26 and 73 of R) | Laboratory stock |

| λ S2168R21 | λ-21 hybrid phage carrying S68RRzRz1 of phage 21 under λPR′ | This study |

| λ S2168R21am | λ-21 hybrid phage carrying S68Ram,amRzRz1 of phage 21 under λ PR′; the R21 gene carries am codons in positions 39 and 42 | This study |

| λ S2168amR21 | λ-21 hybrid phage carrying S68amRRzRz1 of phage 21 under λ PR′; the S2168 gene carries an am codon in position 46 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRE | Vector with pBR322 origin, carrying λ late promoter PR′ | Supplemental information of Park et al. (14) |

| pS105 | pBR322 origin, PR′ promoter, and S105RRzRz1 from λ; in the S105 gene, the first codon of S is converted to a CTG; this allele produces only the S105 holin gene product | 19 |

| pTP2 | S105RRzRz1 of pS105 replaced with S68RRzRz1 of phage 21; in the S2168 gene, the first codon of S21 is converted to a CTG; this allele thus produces only the S2168 gene product | Supplemental information of Park et al. (14) |

| pTP3 | pTP2 with amber codon at position 46 of S2168 | Supplemental information of Park et al. (14) |

| pTP4 | pTP2 with amber codons at positions 39 and 42 of R21 | Supplemental information of Park et al. (14) |

| pS105Ram | pS105 with ochre and amber codons at positions 7 and 9, respectively, of R | Laboratory stock |

| pJFLyz | pJF118 tac vector carrying the P1 lyz SAR endolysin gene | Supplementary information of Xu et al. (26) |

| pRλ | pJF118 tac vector carrying the λ R endolysin gene, analogous to pJFLyz | Supplementary information of Xu et al. (26) |

| pJFT4E | pJF118 tac vector carrying the Τ4 e endolysin gene | M. Xu, unpublished data |

| pTGS | TorA TAT leader sequence fused to SsrA-tagged GFP in pBAD33 | 4 |

FIG. 1.

The absence of S2168 holin contributes to heterogeneity of plaque morphology. MDS12 tonA::Tn10 was used as a host for plating the indicated λ 21 hybrid phages. (A) λS2168R21; (B) λS2168amR21; (C and D) replatings of the small and large plaques from panel B, respectively.

FIG. 2.

The S2168 holin triggers but does not allow release of cytoplasmic endolysins. (A) S2168 supports abrupt lysis with the SAR endolysin R21. Lysogens of MDS12 tonA::Tn10 growing logarithmically in LB medium at 30°C were thermally induced at an A550 of 0.2 by aerating at 42°C for 15 min and at 37°C thereafter. Prophage symbols: ▪, λS2168+R21; ○, λS2168+R21am; •, λS2168amR21+; □, λS2168am R21am. (B) S2168 and Sλ are not functionally equivalent. Lysis-defective lysogens of MC4100 carrying a plasmid with the indicated alleles of holin-endolysin gene pairs were grown and induced as for panel A. The lysis genes on the plasmids are under the transcriptional control of the λ PR′ promoter, which is activated by the Q protein supplied from the induction of the lysogen, as previously described (14). Symbols: ▪, λΔ(SR) and pTP2 (S2168R21); ○, λΔ(SR) and pS105 (SλRλ); ▾, λSam7R+ and pTP4 (S2168R21am), with the arrow indicating the time of addition of CHCl3; □, λS+Ram and pTP3 (S2168amR21). (C and D) Lysogens of MDS12 tonA::Tn10 bearing the indicated prophage and plasmid, the latter carrying an endolysin gene under tac promoter control, were grown and thermally induced as for panel A, except that isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was also added at time zero to induce the plasmid. (C) S2168 does not facilitate lysis by T4 E. •, λΔ(SR) and pJFT4E (e+); □, λS2168+R21am and pJFT4E. CHCl3 was added (arrow) to both cultures (• and □) at 65 min after induction. (D) S2168 allows abrupt lysis by the SAR endolysin P1 lyz. •, λS2168R21am and pJFLyz (lyz+); ○, λS2168R21am and pRλ; ▪, Δ(SR) and pJFLyz; □, λΔ(SR) and pRλ. To verify the expression of the endolysin gene, CHCl3 was added (arrow) to two cultures (○ and □) at 75 min after induction.

S21 and Sλ are not functionally equivalent.

We next designed experiments to determine if S2168 and R21 could complement the lysis defect of phages λSamR+ and λS+Ram, respectively. Previously, we had reported that, when expressed from the pUC18 derivative pTZ18R, the S21 gene appeared to be the functional equivalent of Sλ (2). However, the lysis of the culture was not complete even an hour after its onset, despite the fact that the S21 protein was produced at supraphysiological concentrations from the very-high-copy-number plasmid. For this reason, we repeated these experiments with various alleles of S2168 and R21 transactivated from the λ late promoter on a medium-copy-number plasmid, in trans to lysis-defective prophages. This system was shown in other studies to support lysis with approximately normal timing (1, 6). As can be seen in Fig. 2B, expression of R21 from the plasmid complemented the lysis defect of an induced λS+Ram lysogen, with lysis beginning 55 min after induction and completed within 10 min. In contrast, expression of S2168 did not complement an induced λSamR+ lysogen, despite the fact that the S21 holin triggered, as can be seen from the halt in cell growth at approximately 15 min after induction. Moreover, the addition of CHCl3 resulted in immediate lysis, indicating the presence of a pool of cytoplasmic R endolysin. Similarly, unlike Sλ, S2168 was unable to promote the release of E, the cytosolic endolysin from phage T4 (Fig. 2C). However, coexpression of lyz, encoding the SAR endolysin from phage P1, and S2168 resulted in saltatory and rapid lysis of the host, a characteristic of holin-triggered lysis (Fig. 2D). This S2168-facilitated lysis was easily distinguished from the delayed and gradual lysis that occurs when lyz is induced in the absence of a holin (Fig. 2D) (26). Thus, the phage 21 holin facilitates lysis only when paired with SAR endolysins. We interpret this to mean that when S2168 triggers, it eliminates the proton motive force, causing release and activation of the membrane-tethered inactive SAR endolysin, but does not form holes in the membrane large enough to allow passage of a cytoplasmic endolysin.

Macromolecules easily pass through Sλ but not S21 holes.

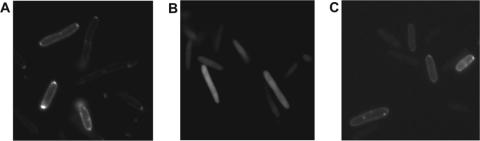

In order to demonstrate that Sλ but not S21 allows the nonspecific movement of macromolecules across the inner membrane, the genes for either holin were expressed in cells producing the fluorescent periplasmic marker TorA-GFP-SsrA (4). The latter protein has the leader peptide and the first 8 amino acids of TorA fused to the N terminus of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) variant, allowing the Tat-specific secretion of the chimera to the periplasm. The SsrA sequence at its C terminus promotes the degradation by the ATP-dependent proteases ClpAP and ClpXP of any of the chimeric protein that escapes export and remains in the cytoplasm. When examined by fluorescence microscopy, a thin ring of fluorescence at the periphery of cells expressing the torA-gfp-ssrA gene is observed (Fig. 3A), indicative of the periplasmic localization of the TorA-GFP-SsrA protein. The induction and triggering of Sλ in such cells result in a uniform, diffuse fluorescence throughout the cytoplasm, indicating that the chimeric GFP has reentered the cytoplasm through the Sλ holes (Fig. 3B). Lack of degradation of the fluorescent chimera by ClpAP and ClpXP is due to the rapid depletion of ATP subsequent to the formation of Sλ holes in the inner membrane. By contrast, the induction and triggering of S2168 in cells with periplasmic TorA-GFP-SsrA did not cause its redistribution to the cytoplasm (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Assessing the passage of a periplasmic marker through membrane lesions generated by S105 and S2168. MDS12 tonA::Tn10 λΔ(SR) lysogens bearing pTGS (torA-gfp-ssrA) and either pRE (vector) (A), pS105 (S105) (B), or pTP2 (S2168) (C) were grown in the presence of 0.2% arabinose for 100 min to induce Tor-GFP-SsrA fusion and then thermally induced. After 1 h, cells were collected by centrifugation, washed, and immediately examined under a Zeiss Axioplan 2 imaging fluorescence microscope.

Implications for the evolution of holin-endolysin systems.

At physiological levels of expression, the holin of phage 21 is lethal and can mediate host lysis when coexpressed with cognate and noncognate SAR endolysins but not with the cytoplasmic endolysins (Fig. 2). We interpret this to mean that the S21 holin makes holes too small to allow the passage of proteins the size of phage endolysins (∼15 kDa) from the cytoplasm to the periplasm. We propose that holins of this type be called “pinholins” to emphasize their small hole size. We suggest that the S21/R21 gene pair, encoding a pinholin and a SAR endolysin, may represent an intermediate stage in the evolution of holin-endolysin systems. The minimum requirement for an effective phage lysis system, other than the muralytic activity itself, is a delay in lysis after the onset of late gene expression, to allow for assembly of progeny virions (28). Originally, phages may have had no dedicated lysis system at all but simply relied on the fact that redirection of the host macromolecular metabolism towards phage replication and assembly would eventually cause cellular disintegration because of a failure in the functions required for maintenance of the envelope. The most primitive dedicated lysis system could have consisted of a SAR endolysin alone. This mode would provide a lysis delay because of the gradual release and activation of the membrane-tethered endolysins. In addition, due to their sensitivity to membrane depolarization, the SAR endolysins would provide a sentinel function (20) to effect immediate lysis in the event of any condition which disrupted the integrity of the membrane, including superinfection, which, in the case of myophage or siphophage, results in a temporary depolarization of the cytoplasmic membrane concomitant with DNA injection (12, 13).

However, a lysis system employing a SAR endolysin alone would be inherently inferior to canonical holin-endolysin systems for two reasons. First, because canonical holins function with cytoplasmic endolysins, the muralytic activity elaborated during the infection cycle can be produced in great excess. Not only does this mean that once the holin triggers, host lysis occurs in a matter of seconds, reducing the dwell time in the dead, nonproductive host to a minimum, but also it means that lysis timing is completely dependent on the holin. Secondly, it has been shown that most missense changes in holin proteins alter the timing of lysis, unpredictably advancing or retarding the instant of triggering (5, 9, 15-17, 24). This malleability would provide a distinct evolutionary advantage, since maintaining fitness under different environmental conditions requires the ability to tune the timing of lysis; for example, increased and decreased host cell densities favor shorter and longer infection cycles, respectively (3, 21, 23). By contrast, SAR endolysins would offer few mutational paths to advance or retard the timing of lysis. A small number of mutations affecting active site residues would meaningfully change the kcat and, similarly, only mutations in the N-terminal SAR domain would be expected to alter the kinetics of membrane release. This combination of malleability and uniformity in the canonical holins would make selection of a new, fitter holin allele, with altered lysis timing, much more rapid when the selective environment changed to the advantage of a shortened or lengthened vegetative cycle.

These advantages are partially replicated in the phage 21 system, with a SAR endolysin and a pinholin, which exhibits a more saltatory lysis profile than the SAR endolysin alone (Fig. 2A). This presumably derives from the quantitative activation of the SAR endolysin at the time of the pinholin triggering, rather than relying on its gradual spontaneous activation (Fig. 2). However, the pinholin has a restricted tuning range, since the SAR endolysin itself will cause lysis at some point after induction, irrespective of the pinholin allele. Moreover, the level of muralytic activity has to be much lower to avoid inappropriately early lysis; in fact, the specific activity of the classic T4 gpe endolysin is >103-fold higher than that of P1 Lyz (25). Presumably, further evolutionary optimization would involve, first, alterations in the holin that would allow it to form protein-sized membrane lesions and, second, loss of the N-terminal SAR domain from the endolysin.

About 25% of phages possess SAR endolysins, as judged by manual inspection of endolysin genes in the currently available phage genomes (I.-N. Wang and R. Young, unpublished). However, the holin of phage P1, which is paired with the SAR endolysin Lyz, is a canonical holin that can complement defects in λ S (M. Xu, D. K. Struck, and R. Young, unpublished), and so there is no way, a priori, to determine how many of the SAR endolysins are served by pinholins. The canonical holins thus have a selective advantage not only for fitness, in terms of the mechanistic advantages of holin function, but also because they can function with either cytoplasmic endolysins or SAR endolysins, whereas the pinholin genes can function only with SAR endolysins. It will be interesting to see whether the S21 pinholin gene can be mutated to a larger hole size, allowing passage of a fully folded cytoplasmic endolysin like Rλ, and thus attain the universal functionality of a canonical holin.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Geourgiou and his laboratory group for the TorA-GFP-SsrA fusion and advice about its use in our system. We also thank the members of the Young laboratory, past and present, for their helpful criticisms and suggestions, especially Rebecca White for her help with the fluorescence experiments. The skillful clerical assistance of Daisy Wilbert is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported by PHS grant GM27099 to R.Y., the Robert A. Welch Foundation, and the Program for Membrane Structure and Function, a Program of Excellence grant from the Office of the Vice President for Research at Texas A&M University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barenboim, M., C.-Y. Chang, F. dib Hajj, and R. Young. 1999. Characterization of the dual start motif of a class II holin gene. Mol. Microbiol. 32:715-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonovich, M. T., and R. Young. 1991. Dual start motif in two lambdoid S genes unrelated to λ S. J. Bacteriol. 173:2897-2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bull, J. J., D. W. Pfennig, and I. N. Wang. 2004. Genetic details, optimization and phage life histories. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19:76-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delisa, M. P., P. Samuelson, T. Palmer, and G. Georgiou. 2002. Genetic analysis of the twin arginine translocator secretion pathway in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29825-29831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gründling, A., U. Bläsi, and R. Young. 2000. Genetic and biochemical analysis of dimer and oligomer interactions of the λ S holin. J. Bacteriol. 182:6082-6090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gründling, A., D. L. Smith, U. Bläsi, and R. Young. 2000. Dimerization between the holin and holin inhibitor of phage lambda. J. Bacteriol. 182:6075-6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris, A. W., D. W. A. Mount, C. R. Fuerst, and L. Siminovitch. 1967. Mutations in bacteriophage lambda affecting host cell lysis. Virology 32:553-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iida, S., and W. Arber. 1977. Plaque forming specialized transducing phage P1: isolation of P1CmSmSu, a precursor of P1Cm. Mol. Gen. Genet. 153:259-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson-Boaz, R., C.-Y. Chang, and R. Young. 1994. A dominant mutation in the bacteriophage lambda S gene causes premature lysis and an absolute defective plating phenotype. Mol. Microbiol. 13:495-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josslin, R. 1970. The lysis mechanism of phage T4: mutants affecting lysis. Virology 40:719-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolisnychenko, V., G. Plunkett III, C. D. Herring, T. Feher, J. Posfai, F. R. Blattner, and G. Posfai. 2002. Engineering a reduced Escherichia coli genome. Genome Res. 12:640-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labedan, B., and L. Letellier. 1981. Membrane potential changes during the first steps of coliphage infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:215-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Letellier, L., and P. Boulanger. 1989. Involvement of ion channels in the transport of phage DNA through the cytoplasmic membrane of E. coli. Biochimie 71:167-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park, T., D. K. Struck, J. F. Deaton, and R. Young. 2006. Topological dynamics of holins in programmed bacterial lysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:19713-19718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raab, R., G. Neal, C. Sohaskey, J. Smith, and R. Young. 1988. Dominance in lambda S mutations and evidence for translational control. J. Mol. Biol. 199:95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramanculov, E. R., and R. Young. 2001. Genetic analysis of the T4 holin: timing and topology. Gene 265:25-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rydman, P. S., and D. H. Bamford. 2003. Identification and mutational analysis of bacteriophage PRD1 holin protein P35. J. Bacteriol. 185:3795-3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silhavy, T. J., M. L. Berman, and L. W. Enquist. 1984. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 19.Smith, D. L., C.-Y. Chang, and R. Young. 1998. The λ holin accumulates beyond the lethal triggering concentration under hyper-expression conditions. Gene Expr. 7:39-52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran, T. A. T., D. K. Struck, and R. Young. 2005. The role of holin and antiholin periplasmic domains in T4 lysis inhibition. J. Bacteriol. 187:6631-6640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, I. N. 2006. Lysis timing and bacteriophage fitness. Genetics 172:17-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, I. N., J. F. Deaton, and R. Young. 2003. Sizing the holin lesion with an endolysin-β-galactosidase fusion. J. Bacteriol. 185:779-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, I. N., D. E. Dykhuizen, and L. B. Slobodkin. 1996. The evolution of phage lysis timing. Evol. Ecol. 10:545-558. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, I. N., D. L. Smith, and R. Young. 2000. Holins: the protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:799-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu, M., A. Arulandu, D. K. Struck, S. Swanson, J. C. Sacchettini, and R. Young. 2005. Disulfide isomerization after membrane release of its SAR domain activates P1 lysozyme. Science 307:113-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu, M., D. K. Struck, J. Deaton, I. N. Wang, and R. Young. 2004. The signal arrest-release (SAR) sequence mediates export and control of the phage P1 endolysin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, USA 101:6415-6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yarmolinsky, M. B., and N. Sternberg. 1988. Bacteriophage P1, p. 291-438. In R. Calendar (ed.), The bacteriophages, vol. 1. Plenum Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young, R., and I. N. Wang. 2006. Phage lysis, p. 104-126. In R. Calendar (ed.), The bacteriophages. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.