Abstract

The production of bacteriocins can be favorable for colonization of the host by eliminating other bacterial species that share the same environment. In Streptococcus pneumoniae, the pnc (blp) locus encoding putative bacteriocins, immunity, and export proteins is controlled by a two-component system similar to the comCDE system required for the induction of genetic competence. A detailed comparison of the pnc clusters of four genetically distinct isolates confirmed the great plasticity of this locus and documented several repeat sequences. Members of the multiple-antibiotic-resistant Spain23F-1 clone, one member of the Spain9V-3 clone, sensitive 23F strain 2306, and the TIGR4 strain produced bactericidal substances active against other gram-positive bacteria and in some cases against S. pneumoniae as well. However, other strains did not show activity against the indicator strains despite the presence of a bacteriocin cluster, indicating that other factors are required for bacteriocin activity. Analysis of strain 2306 and mutant derivatives of this strain confirmed that bacteriocin production was dependent on the two-component regulatory system and genes involved in bacteriocin transport and processing. At least one other bacteriocin gene, pncE, is located elsewhere on the chromosome and might contribute to the bacteriocin activity of this strain.

Bacteriocins are small heat-stable peptides common in gram-positive bacteria (16, 22). The production of bacteriocins has been related to the producer's ability to colonize a host more efficiently due the ability of these peptides to eliminate competitor strains, which often include other species. The human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae is a frequent colonizer of the nasopharynx, and the potential to produce active bacteriocins might play an important role during changes in the pneumococcal strains in the human host and their competition with other strains and other serotypes of the same species, as well as the commensal flora, and might therefore be related indirectly to the pathogenicity potential of the strains.

The constantly growing number of available genome sequences enables searches of genes and gene clusters involved in the production of bacteriocins, facilitating genetic analysis of their regulation and function. Four complete genome sequences of S. pneumoniae are currently available: that of the TIGR4 strain, a highly virulent serotype 4 strain isolated in the late 1970s (46); those of both laboratory strain R6 isolated in the 1940s and its ancestor derived in the 1940s from the type 2 strain D39 (24, 31); and that of a serotype 19 F strain, G54 (http://cmr.tigr.org). The TIGR4 strain contains several gene clusters representing over 150 kb of the 2.2-Mb genome that are not present in R6 and D39 (6), including an approximately 6-kb putative bacteriocin gene cluster (13, 38). This cluster has been shown to be highly variable by genomic hybridization experiments with oligonucleotide microarrays among a set of 20 S. pneumoniae strains tested (20), suggesting that bacteriocin production also differs between different isolates.

The gene cluster designated pnc (38) or blp (13) contains genes encoding class IIb bacteriocins with a typical double-glycine leader peptide followed a glycine-rich mature peptide, small hydrophobic proteins that are putative bacteriocin immunity proteins, and membrane proteins of the CAAX prenyl endopeptidase family (35). They are induced via a complex regulatory system which is located upstream of the bacteriocin cluster (13, 38), resembling the quorum-sensing system involved in genetic competence (9). This system consists of the double-glycine peptide pheromone SpiP, the dedicated ABC transporter SpiABCD containing a peptidase C39 domain, and the two-component signal transducing system SpiR2/H preceded by the partial response regulator SpirR1. The histidine kinase SpiH is believed to act as a receptor for the pheromone peptide, resulting in activation of the response regulator, which in turn acts as an autoinducer of the regulatory system and induces the genes of the pnc/blp bacteriocin cluster as well, probably by binding to a 9-bp direct repeat motif which is part of all operons in the bacteriocin cluster (13). The repeat is closely related to the imperfect repeat motif of the response regulator ComE involved in competence induction, in which 33% of the amino acids are shared with SpiR2 (27, 50). Induction of genes putatively regulated by SpiR/BlpR has been observed only upon addition of synthetic peptide pheromone to the growth medium. This includes the regulatory system with the peptide pheromone and the ABC transporter, documenting autoregulation of the system, as well as the bacteriocin cluster located downstream (13, 38). The natural conditions necessary for induction of the bacteriocins, as well as their function, remain unknown.

We analyzed the bacteriocin cluster in a variety of S. pneumoniae isolates to investigate the variation in this region among and within clones of this species. In addition, an assay for bacteriocin activity was established, which demonstrated interspecies as well as intraspecies activity. Mutants with mutations in the regulatory system and in the bacteriocin cluster were constructed using the genetically competent isolate 2306 in order to examine the genetic requirements for the apparent bacteriocin activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Streptococci were grown in C-medium supplemented with 0.1% yeast extract (Difco) at 37°C without aeration (30). In some experiments, the synthetic SpiP peptide of S. pneumoniae was added at a concentration of 100 ng/ml (N [nephelometric units] = 20). Cellular growth was followed by measuring turbidity using a nephelometer (Diffusion Systems Ltd., England). Escherichia coli JM109, E. coli invα F′, Pseudomonas putida, and Bacillus subtilis were grown in LB broth at 37°C with aeration. All other bacterial strains were grown in LB broth at 37°C without aeration (Table 1). The antibiotic concentrations used for selection in E. coli JM109 were 500 μg/ml erythromycin for pJDC9 derivatives and 100 μg/ml ampicillin or 80 μg/ml spectinomycin for pGEM derivatives; S. pneumoniae strains containing pJDC9 derivatives were selected using 1 μg/ml erythromycin.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Serotype | Origin, genotype, and/or phenotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae strains | |||

| R6 | United States | 4 | |

| TIGR4 | 4 | Norway | 1 |

| 628 | 9V | Spain | 43 |

| Hu15 | 19A | Hungary | 39 |

| 496a | 19F | Spain, 1987 | 43 |

| 456a | 23F | Spain, 1984 | 43 |

| 632a | 23F | Spain, 1987 | 43 |

| 637a | 23F | Spain, 1987 | 43 |

| 638a | 23F | Spain, 1987 | 43 |

| 653a | 23F | Spain, 1987 | 43 |

| 673a | 23F | Spain, 1987 | 43 |

| 674a | 23F | Spain, 1987 | 43 |

| 677a | 23F | Spain, 1987 | 43 |

| SA16a | 23F | South Africa | 43 |

| SA17a | 23F | South Africa | 43 |

| F4a | 23F | France | Collection of Kaiserslautern University |

| F14a | 23F | France | Collection of Kaiserslautern University |

| 2306 | 23F | Finland, 1985 | 43 |

| 2306spiB::pJDB2 | 23F | spiB::pJDB2 mutant of 2306 | This study |

| 2306spiR::pJDR1 | 23F | spiR2::pJDR1 mutant of 2306 | This study |

| 2306pncO::pJDO3 | 23F | pncO::pJDO3 mutant of 2306 | This study |

| 2306pncP::pJDP4 | 23F | pncP::pJDP4 mutant of 2306 | This study |

| 2306ΔpncR-K | 23F | pncR-K deletion mutant of 2306 | This study |

| TIGR4ΔpncA-N | 4 | pncA-N deletion mutant of TIGR4 | This study |

| Other bacteria | |||

| Streptococcus salivarius 674 | Collection of Kaiserslautern University | ||

| Streptococcus oralis 510 | Collection of Kaiserslautern University | ||

| Streptococcus pyogenes spy 15 | Collection of Kaiserslautern University | ||

| Streptococcus sanguis DSM 20567 | 28 | ||

| Streptococcus mitis NTCC10712 | 26 | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus 113 | Collection of Kaiserslautern University | ||

| Lactococcus lactis MG1363 | 51 | ||

| Micrococcus luteus DSM2786 | 42 | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 | 45 | ||

| Listeria ivanovii | 21 | ||

| Listeria welshimeri | 21 | ||

| Bacillus subtilis DB 403 | Collection of Kaiserslautern University | ||

| Pseudomonas putida DSM50906 | 53 | ||

| Escherichia coli JM109 | 54 | ||

| Escherichia coli invα F′ | Promega | ||

| Plasmids | |||

| pJDC9 | Eryr; nonreplicative in S. pneumoniae | 8 | |

| pJDR1 | Eryr; pJDC9 derivative carrying an internal DNA fragment of spiR2 | This study | |

| pJDB2 | Eryr; pJDC9 derivative carrying an internal DNA fragment of spiB | This study | |

| pJDO3 | Eryr; pJDC9 derivative carrying an internal DNA fragment of pncO | This study | |

| pJDP4 | Eryr; pJDC9 derivative carrying an internal DNA fragment of pncP | This study | |

| pGEM-T Easy | Ampr | Promega | |

| pGEM-AB | Ampr; pGEM-T Easy derivative carrying a fragment of spiA and pncO | This study | |

| pGEM-ASB | Ampr Spcr pGEM-T Easy derivative carrying a fragment of spiA and pncO and the aad9 gene | This study |

Member of the multiresistant Spain23F-1 clone.

Transformation.

Plasmids were transformed into E. coli strains using standard protocols for electroporation (Bio-Rad, United States) and were isolated using alkaline lysis protocols (5). The methods used for preparation of competent cells of S. pneumoniae and transformation procedures have been described previously (33). Briefly, 200 μl of competent cells of S. pneumoniae was incubated at 30°C for 45 min in the presence of DNA and then shifted to 37°C for 2 h before plating onto D-agar in the presence of the selective antibiotic.

Assay for bacteriocin production.

A variety of techniques have been used to determine the activity of bacteriocins. For our needs we had to adapt a test based upon antagonistic inhibition which is commonly used with a Lactococcus background (14, 15). The assay is based on a dual-layer blood agar plate system in a 12-cm petri dish; D-agar (2) supplemented with 3% defibrinated sheep blood (Oxoid, Germany) was used throughout. The bottom layer consisted of 15 ml of blood agar on which the bacteriocin-producing tester strain grew, and the top layer consisted of 10 ml of D-agar to support growth of the indicator strain. To screen for bacteriocin activity, 50-μl aliquots of an appropriate dilution in saline of an early-exponential-phase S. pneumoniae culture (n = 30 to 35) were plated on the bottom layer, resulting in 50 to 100 CFU per plate. The plates were dried for 30 min at room temperature before a second layer of 10 ml D-agar was added. The plates were incubated for 16 h in a candle jar at 35°C to allow sufficient time for bacteriocin production and diffusion. Then 100 μl of an exponentially growing indicator strain (n = 30) was plated on the top layer, followed by another 16-h incubation period under the same conditions. Zones of growth inhibition were recorded with a digital imaging system (Digital Interface DFW-X700 [Sony, Japan], Lucia Image [Laboratory Imaging, Czech Republic], and Nikkor 24 mm f/2.8D [Nikon, Japan]).

Construction of loss-of-function mutants.

Insertion-duplication mutagenesis was performed using internal fragments of the spiR, spiB, pncO, and pncP genes cloned into the vector pJDC9 (8). The DNA fragments were amplified from chromosomal DNA using Goldstar Red polymerase (Eurogenetec, Belgium) and the following primer pairs: dspiR2-for/dspiR2-rev for spiR, dspiB-for/dspiB-rev for spiB, dpncO-for/dpncO-rev for pncO, and dpncP-for/dpncP-rev for pncP. PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector system (Promega, United States), and after digestion of the constructs with EcoRI the gene fragments were subcloned into the EcoRI restriction site of pJDC9 (Table 1). Plasmids were transformed into S. pneumoniae, and the resulting mutants were selected with 1 μg/ml erythromycin. Insertion and the orientation of the pJDC9 constructs were examined using primers M13-universal (−21) and M13-reverse (−49) in combination with primers upstream and downstream of the integrated region.

The spectinomycin resistance gene aad9 from pDL278 (32) was used for replacement of the bacteriocin gene region in S. pneumoniae 2306 (pncR-K). Two fragments of the spiA gene and the pncO gene flanking the region to be deleted were amplified with primer pairs spiBC-for/pncA-NheI-rev for spiA and pncO-NheI-for/pncP-rev for pncO. The primers were designed based on the strain 632 sequence to obtain a fragment suitable for deletion of the bacteriocin cluster in any strain. The PCR fragments which hybridized via the overlapping primer sequences (Table 2) were combined by PCR with primers spiB-for and dpncO-rev, yielding a single 1-kb PCR product with an internal NheI restriction site. This fragment was ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector, resulting in vector pGEM-AB. The aad9 gene with flanking NheI sites from plasmid pCR-spec (33) was ligated into NheI-digested vector pGEM-AB. The resulting plasmid, pGEM-ASB, was transformed into S. pneumoniae, and mutants were selected with 80 μg/ml spectinomycin. Insertion and the orientation of the resistance cassette were verified by PCR and DNA sequence analysis using primers spec-out-r1, spec-out-u2, spiBC-for, and pncP-rev.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | Position in the genome of:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| R6 | TIGR4 | ||

| RT-pncI-for | GAG TGC TGG TAT TAT CAA TC | —a | 514905 |

| RT-pncI-rev | CCG GAA TTA CCT CCA TAA AC | —a | 515422 |

| RT-pncJ-for | ATC TTT GGG CAG GAG TAA CA | —a | 515305 |

| RT-pncJ-rev | GGT TTG AAA AGC GAA GAG AA | —a | 515624 |

| RT-ldh-for | CGG TGA TGG TGC TGT AGG TTC ATC | 1098163 | 1150087 |

| RT-ldh-rev | GTG TTC ACC CAT GAT GTA C | 1098667 | 1150591 |

| RT-pncE-for | AAT TAT GGA TAC TGA GAT GCT TG | 39543 | 39900 |

| RT-pncE-rev | CTG CAT AGG CCA CAC C | 39727 | 40084 |

| spiBC-for | AGG CTA ACC TTA TCT CCT TGT TTA ATC GTG AG | 474089 | 509889 |

| pncA-NheI-revb | GAC TAC TAG ATA ATA GAT ACG CTA GCT TTG TAT | ||

| TCA TGA CAA ATA CTC C | |||

| pncO-NheI-forb | GGA GTA TTT GTC ATG AAT ACA AAG CTA GCG TAT | ||

| CTA TTA TCT AGT AGT C | |||

| pncP-rev | TCG ATG GAT CCA TAT TTC ATA ATT TTT ATA AAT | 477928 | 519138 |

| AAT ATA GGA GTG GCC | |||

| spiA-for | GCA GTC GTC CCT TCT TTA TTG GTC | 475485 | 511285 |

| spiB-for | GAA CGG TTA GGA GAT AAT CTC TGG AG | 474936 | 510736 |

| dpncO-rev | GAA GCC AAG ACT AGA ATA TAG GGT GTC | 476995 | 518205 |

| dspiB-for | CGT TGA TAT CTT CGA TAA TGG CAG AGC | 474576 | 510376 |

| dspiB-rev | TCC AAC AAG TCA TGA GCT TCT CCA G | 474980 | 510780 |

| dspiR2-for | CTG CTG GCT GAA GTG CAT GAG AAG GGG | 469889 | 505686 |

| dspiR2-rev | GGC TCT GGG CGA CGT TTC GAG ATA G | —c | 506060 |

| dpncO-for | GGG AGG ATT TCT ATG AAA AAG TAT | 476179 | 517389 |

| CAA CTT CTA TTC | |||

| dpncP-for | TGT CAT TAC AGT TCC TTA TAC G | 477362 | 518573 |

| dpnP-rev | AAC TGA GGT AGT CAA AAT CA | 477643 | 518854 |

Gene not present in the genome.

Restriction site is underlined.

TIGR4-specific sequence.

Long-range PCR, DNA sequencing, and sequence analysis.

The pnc clusters were amplified using the Expand Long template PCR system (Roche Applied Science, United States) with primers spiA-for and pncP-rev. The reaction mixture was prepared as recommended by the manufacturer with buffer 1, and the PCR was carried out using the following amplification conditions: (i) 10 cycles with an elongation time of 8 min and (ii) 15 cycles with an elongation time of 8 min with an increase of 20 s after every cycle, using 55°C for annealing and 68°C for extension. DNA sequencing was performed with an ABI Prism dye terminator reaction kit 3.1 and an ABI 3100 capillary sequencer.

RNA preparation and real-time RT-PCR.

For all experiments, 10 ml of an exponentially growing S. pneumoniae culture in C-medium was harvested at a cell density of N = 80, and after centrifugation at a relative centrifugal force of 8,000 and 4°C for 10 min cells were lysed by addition of 100 μl of 0.01% sodium deoxycholate-0.02% sodium dodecyl sulfate. RNA was prepared with QIAGEN RNeasy columns as recommended by the manufacturer (QIAGEN, Germany). One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a First Strand cDNA synthesis kit for reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) with random hexamer primers. Five microliters of 1:10-diluted cDNA was used in an RT-PCR, using a LightCycler Fast Start DNA Master Plus SYBR green I kit (Roche Diagnostics, Germany), the manufacturer's instructions, and 10 pmol of each primer in a 20-μl (total volume) mixture. The reaction mixture was placed into a LightCycler capillary, which was then centrifuged at 735 × g for 15 s in an LC Carousel 2.0 centrifuge and loaded into a LightCycler 2.0 thermocycler (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). The following temperature profile was used for amplification: denaturation/activation for one cycle at 95°C for 10 min, 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s (temperature transition rate, 20°C s−1), 55°C for 10 s (temperature transition rate, 20°C s−1), and 72°C for 14 s (temperature transition rate, 20°C s−1), with fluorescence acquisition in the single mode at the end of each cycle. Melting curve analysis was performed at 65 to 95°C (temperature transition rate, 0.1°C s−1) with continuous fluorescence acquisition in all cases. Gene-specific amplification from cDNA was carried out with the following primer combinations: for ldh (504 bp), RT-ldh-for and RT-ldh-rev; for pncI (517 bp), RT-pncI-for and RT-pncI-rev; for pncJ (319 bp), RT-pncJ-for and RT-pncJ-rev; and for pncE (184 bp), RT-pncE-for and RT-pncE-rev. Each measurement was performed in duplicate, and the mean value was determined. All experiments were performed with at least three independently grown cultures.

Computational programs.

Nucleotide sequences were assembled using Phred/Phrap/Consed (18). Database searches were done using BLAST (3). Open reading frames (ORFs) were determined using the NCBI ORF Finder (52). Alignments were constructed with Multalin (10). Pairwise sequence comparisons were performed with the Artemis comparison tool (7).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences have been deposited in the GenBank database under the following accession numbers: strain 2306, EF488100; strain 2306pncE, EF488094; strain 628, EF488095; strain 632, EF488096; strain F4, EF488097; strain Hu15, EF488098; strain R6, EF488099; and strain TIGR4, EF488093.

RESULTS

Bacteriocin clusters in different S. pneumoniae clones.

For amplification of the bacteriocin cluster by long-range PCR in different S. pneumoniae isolates, oligonucleotides that primed within spiA and in the 5′ region of pncP were designed for generation of PCR fragments since these genes were present in both the genome of TIGR4, which contains the cluster, and the genome of R6, which does not contain the cluster. Members of major penicillin-resistant clones were selected, including a multiple-antibiotic-resistant Hungarian serotype 19A isolate (strain Hu15), 18 members of the early multiple-antibiotic-resistant and high-level penicillin-resistant clone Spain23F-1, and one member of clone Spain9V-3 (strain 628); a penicillin-sensitive 23F isolate from Finland (strain 2306) was also included (Table 1) because it showed a strong phenotype in the bacteriocin assay and was transformable with high efficiency. In all cases a PCR product was obtained which was larger than the 2.5-kb fragment of the R6 strain; the sizes ranged from approximately 4 kb in strain Hu15 to 8 kb in strains 628 and TIGR4, suggesting that there is a variable genomic region. The sizes of the PCR fragments obtained from all 18 members of the Spain23F-1 clone, which included early serotype switch 19F strain 496 and isolates from different countries and continents (Table 1), were identical, as judged by agarose gel electrophoresis, strongly suggesting that there is no variation within this clone with respect to the size of the bacteriocin cluster.

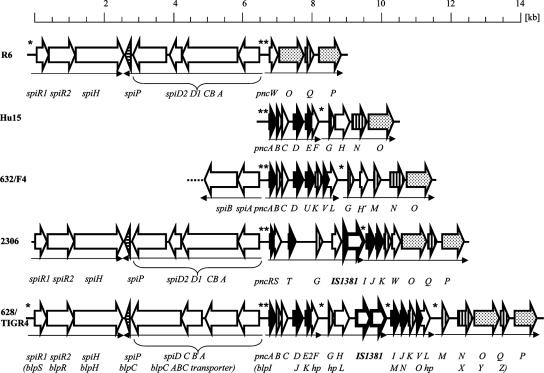

DNA sequence analyses of the bacteriocin clusters were performed for two members of the Spain23F-1 clone and for the other genetically distinct isolates, and the presence of genes similar to those in the TIGR4 cluster was confirmed in all cases. All of the different clusters included genes encoding putative bacteriocins, immunity proteins, and CAAX proteases implicated in bacteriocin processing (35). Figure 1 gives an overview of the genetic arrangement of the three new clusters compared to the R6 and TIGR4 genes.

FIG. 1.

Bacteriocin cluster and regulatory components in S. pneumoniae strains. The gene encoding the pheromone BlpC/SpiP is indicated by arrowheads with horizontal stripes. Genes in the bacteriocin cluster are indicated as follows: solid arrows, genes encoding putative bacteriocins with the typical double-glycine-type leader sequence; dotted arrows, CAAX peptidases; arrows with vertical stripes, immunity proteins; bold type, IS1381 element and truncated derivatives; open arrows, hypothetical genes of unknown function. Asterisks indicate SpiR2 recognition motifs, and small arrows indicate transcription units. Genes are designated as described by Reichmann et al. (38). Except for the first pnc gene the pnc genes in the bacteriocin clusters are indicated by only uppercase letters; annotated genes in the TIGR genome are indicated by brackets. A Hu15 spiA gene is present, but it has not been fully sequenced.

The two resistant 23F strains, strains 632 and F4, contained identical clusters. Also, the 628 sequence was nearly identical to that of TIGR4 (47 bp and 15 amino acid changes plus two single nucleotide insertions within the 13,966-bp fragment of strain 628), with significant alterations only in pncF (6 bp and one amino acid change) and pncO (27 bp and 10 amino acid changes); two single-nucleotide insertions occurred in intergenic regions. The other three clusters were completely different; whereas the Hu15 cluster lacked the entire TIGR4 region, including pncH-pncM, the 2306 cluster contained three new genes, pncRST, and lacked large parts of the TIGR4 cluster, and the 632 cluster, which contained a new pncU gene, showed marked rearrangements compared to TIGR4. The IS1381 element that occurs frequently in S. pneumoniae genomes was present only in the TIGR4/628 and 2306 clusters (41).

A detailed pairwise comparative analysis revealed several inconsistencies, including neglected ORFs compared with previously published annotations of the TIGR4 cluster, and we therefore decided to reannotate these regions and chose the nomenclature which distinguishes the regulatory region (spi genes) from the bacteriocin cluster (pnc genes) (Table 3) (38). The highly divergent bacteriocin clusters include multiple repeat sequences, indicating that this region is a hot spot for recombination events with a history of multiple insertions and deletions. Since such repeats are parts of coding regions in several cases, there are putative genes which are identical in part but contain different extensions. Examples include (i) TIGR4/632 pncL, which is part of a duplication of a region that includes TIGR4/Hu15 pncF, resulting in a 5′ extension of pncL; (ii) TIGR4/Hu15 pncH (blpL), which is longer than 632 pncH′ due to the presence of a repeat sequence in the 5′ region, resulting in extension of the ORF; and (iii) a region which includes the coding sequence for the leader peptide in pncA (blpI) and upstream sequences, which is part of almost all bacteriocin genes (except pncT in 2306 and pncJ in TIGR4) and the spr0470 gene in R6, the latter of which encodes a putative protein in which the double-glycine motif is absent (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the putative pncQ (blpZ) gene includes part of a BOX sequence in its reading frame. The full set of pairwise comparisons of all bacteriocin clusters can be viewed at http://nbc11.biologie.uni-kl.de/comparison_bacteriocin_cluster.

TABLE 3.

Genes of the spi/pnc cluster and their putative functions

| Gene | Synonym | Putative function |

|---|---|---|

| spiR1 | blpS | Regulatory protein |

| spiR2 | blpR | Response regulator |

| spiH | blpH | Histidine kinase |

| spiP | blpC | Peptide pheromone |

| spiD | blpB | Transport accessory protein |

| spiA | blpA | ABC transporter, ATPase |

| spiB | blpA | ABC transporter, transmembrane domain |

| spiC | blpA | ABC transporter, C39 protease domain |

| pncA | blpI | Bacteriocin |

| pncB | NAa | Immunity protein |

| pncC | NA | Hypothetical protein |

| pncD | blpJ | Bacteriocin |

| pncE | blpU/thmA | Bacteriocin |

| pncE2 | blpK | Bacteriocin |

| pncF | SP0534 | Hypothetical protein |

| pncG | SP0535 | Immunity protein |

| pncH | blpL | Hypothetical protein |

| pncI | blpM | Bacteriocin |

| pncJ | blpN | Bacteriocin |

| pncK | NA | Immunity protein |

| pncL | SP0542 | Hypothetical protein |

| pncM | NA | Immunity protein |

| pncN | blpX | Immunity protein |

| pncO | blpY | CAAX protease |

| pncP | SP0547 | CAAX protease |

| pncQ | blpZ | Immunity protein |

| pncR | Bacteriocin | |

| pncS | Hypothetical protein | |

| pncT | Bacteriocin | |

| pncU | Bacteriocin | |

| pncV | blpO | Bacteriocin |

| pncW | spr0470 | Hypothetical protein, fusion |

NA, not annotated.

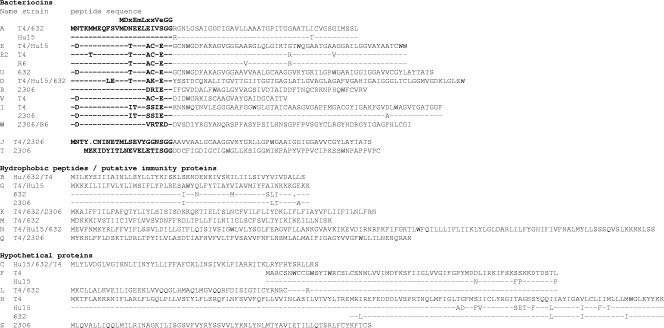

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequences of bacteriocins, immunity proteins, and proteins of unknown function in the bacteriocin cluster of S. pneumoniae strains. Only divergent amino acids are shown in homologous peptides of different strains. The double-glycine leader peptide of the bacteriocin genes is indicated by bold type. The nomenclature is the same as that in Fig. 1. T4, TIGR4.

In addition to the bacteriocin cluster, the region encoding the signaling peptide SpiP and the designated ABC transporter SpiABCD thought to process and export the peptide pheromone as well as the bacteriocin peptides was sequenced in the 2306 strain (Fig. 1). The genetic design of the ABC transporter which is homologous to the comAB locus involved in the processing and export of the competence signaling peptide CSP is different: there are either one (TIGR4) or two (R6) ORFs encoding the ComB homologue SpiD and three (TIGR4) or two (R6) ORFs encoding the ComA homologue SpiABC (13). The spiABCD region in 2306 is an R6-type region. Nevertheless, in all cases the products represent the entire ABC transporter, but different domains are fused to each other, indicating that there is a functional protein complex.

Bactericidal activity in S. pneumoniae.

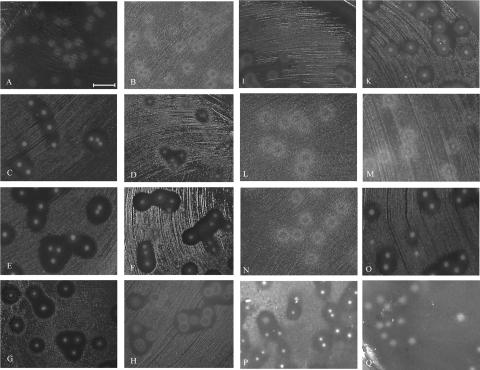

In order to see whether the presence of bacteriocin genes correlates with the production of antibacterial compounds, we established a test system on the basis of previously described bacteriocin assays as described in Materials and Methods. Briefly, the test strain was plated on top of a first agar layer, and after a growth period allowing the production of bacteriocins and their diffusion into a second agar layer, the presence of bactericidal activity was tested by plating one of two indicator strains used frequently in bacteriocin assays, Micrococcus luteus and Lactococcus lactis, on top (Fig. 3). Slightly larger inhibition zones were observed with M. luteus than with L. lactis, but documentation of inhibition zones was easier with L. lactis as the indicator. For optimal results plates were incubated at 35°C in a candle jar; at 37°C under normal oxygen concentrations bactericidal activity was not detectable (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Bacteriocin-like activity in S. pneumoniae. Different S. pneumoniae strains were tested for bacteriocin production with L. lactis (A, C, E, and G) or M. luteus (B, D, F, and H) as the indicator strain, using the double-layer technique as described in Materials and Methods. The test strains included R6 (A and B), TIGR4 (C and D), 2306 (E and F), and 632 (G and H). Strain 632 also showed activity against S. mitis NCTC10712 (I) and S. pneumoniae R6 (K) as indicator strains. The bacteriocin activities of different S. pneumoniae mutants against L. lactis were also determined; the mutants used were S. pneumoniae 2306spiR::pJDR1 (L), S. pneumoniae 2306spiB::pJDB2 (M), S. pneumoniae 2306pncO::pJDO3 (N), S. pneumoniae 2306ΔpncR-K (O), S. pneumoniae 2306pncP::pJDP4 (P), and S. pneumoniae TIGR4ΔpncA-N (Q). The mutants with mutations in spiR2, spiB, and pncO are bacteriocin negative, and the pncP mutant is bacteriocin positive. The 2306ΔpncR-K mutant is bacteriocin positive, but the zones of inhibition are slightly smaller than those of the wild type. In contrast, the TIGR4ΔpncA-N mutant is bacteriocin negative. Bar = 1 cm.

With R6 (which contained no bacteriocin genes in the cluster) as the test strain, the indicator strains grew evenly over the entire surface (Fig. 3A and B), confirming the absence of bactericidal activity in R6. The Hungarian strain Hu15 also did not produce detectable amounts of bacteriocins (not shown), although it contained apparently intact bacteriocin genes (Fig. 1), indicating that either there was a defect in induction or export and processing of the bacteriocins occurred. In contrast, zones of growth inhibition were visible above the TIGR4 colonies with both indicator strains (Fig. 3C and D). Test strains 2306 and 632 produced clearly larger growth inhibition zones than TIGR4 produced (Fig. 3E to H). This suggests that either a more potent bacteriocin(s) is encoded elsewhere on the chromosome or larger amounts are produced in the case of the 632 strain, whereas this phenotype of the 2306 strain could also be due to the presence of any of the three new ORFs in the cluster (Fig. 2). Strain 628 also showed inhibitory activity similar to that observed with the TIGR4 strain (not shown).

In addition, 13 members of the Spain23F-1 clone were investigated. Five strains, including the South African isolates, did not produce detectable amounts of bacteriocins (strains 637, 653 674, SA16, and SA17) (Table 1) independent of the indicator strain used, whereas another eight strains did (456, 496, 632, 638, 673, 677, F14, and F4). This shows that although the size of the bacteriocin cluster was the same for all members of the Spain23F-1 clone, there were differences in terms of the production of bactericidal substances. All positive strains gave large zones of inhibition similar to those produced by the 632 strain (Fig. 3G and H).

Bactericidal activity spectrum with other bacterial species.

A variety of bacterial species were tested to determine their sensitivities to three bacteriocin-producing strains, S. pneumoniae TIGR4, 632, and 2306. None of the three test strains showed activity against the indicator strains of Enterococcus faecalis, Listeria ivanovii, Listeria welshimeri, Streptococcus sanguis, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and Pseudomonas putida. However, activity against other S. pneumoniae strains and other Streptococcus spp. (Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus mitis, and Streptococcus oralis strains) was detectable with the 632 strain, and 2306 showed activity against S. mitis and Streptococcus salivarius (Table 4); examples are shown in Fig. 3I and K. The TIGR4 strain showed no activity against any of the indicator strains other than M. luteus and L. lactis. This suggests that the 632-specific bacteriocins not present in the TIGR4 strain are responsible for this phenotype. It should be emphasized here that the responses with the indicator strains used do not necessarily represent the responses of the different species in general, especially in view of the great variation in genes encoding putative bacteriocins and immunity proteins in S. pneumoniae.

TABLE 4.

Bacteriocin activities of S. pneumoniae strains against different indicator strains

| Indicator strain | Activity against the following S. pneumoniae test strains:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2306 | 632 | TIGR4 | 628 | R6 | |

| M. luteus DSM2786 | + | + | + | + | − |

| L. lactis M61363 | + | + | + | + | − |

| S. pneumoniae R6 | − | + | − | − | − |

| S. pneumoniae 2306 | − | + | − | − | − |

| S. oralis 510 | − | + | − | − | − |

| S. pyogenes 15 | − | + | − | − | − |

| S. mitis NCTC10712 | + | + | − | − | − |

| S. salivarius 674 | + | − | − | − | − |

| S. sanguis DSM 20567 | − | − | − | − | − |

Bacteriocin production in mutants of S. pneumoniae 2306.

To examine the relationship between the bacteriocin cluster genes and phenotypic bacteriocin production, we chose strain 2306 since it was highly competent and mutants could be generated easily. Therefore, in addition to the bacteriocin cluster described above, flanking regions were also sequenced, which demonstrated the presence of the regulatory genes encoding the TCS13 components SpiR1, SpiR2, and SpiH, the SpiP peptide, and the ABC transporter SpiABCD on one side, with the SpiP peptide gene and the receptor kinase gene SpiH representing the R6 alleles; on the other side the pncN and pncO genes were in the same arrangement as they are in the TIGR4 genome (Fig. 1).

Four loss-of-function 2306 mutants were generated by insertion duplication mutagenesis in the following single genes: (i) the response regulator gene spiR2 of the TCS13 two-component system involved in activation of the bacteriocin genes (13, 38); (ii) spiB encoding part of the ABC transporter believed to represent the dedicated transporter for the signaling peptide SpiP; and (iii) pncO and pncP encoding proteins with homology to the CAAX family of proteases suggested to be involved in processing and activation of bacteriocins and/or immunity proteins (35). Finally, the region between spiA and pncO including all four putative bacteriocin genes (pncR, pncT, pncI, and pncJ) was replaced with the spectinomycin resistance cassette, resulting in the construct 2306ΔpncR-K, leaving the genes encoding the regulatory system as well as pncO, pncQ, and pncP intact. Replacement of the entire peptide cluster was also done in strain TIGR4, resulting in mutant TIGR4ΔpncA-N.

When tested for apparent bacteriocin production, the spiR2, spiB, and pncO single-gene mutants displayed a bacteriocin-negative phenotype (Table 5). This shows not only that an active TCS13 and the putative SpiP transporter are required for bacteriocin activity but also that the putative CAAX peptidase PncO plays an important role in this process, whereas PncP does not. However, mutant 2306ΔpncR-K with the deleted bacteriocin genes still showed bactericidal activity, although somewhat less than the 2306 parent, suggesting that other bacteriocin genes are located elsewhere on the chromosome.

TABLE 5.

Bacteriocin activities of S. pneumoniae 2306 derivatives and sensitivity to the parental strain S. pneumoniae 2306 as the test strain

| S. pneumoniae strain | Activity with L. lactis | Sensitivity to 2306 |

|---|---|---|

| 2306 | + | − |

| 2306spiB::pJDB2 | − | + |

| 2306spiR::pJDR1 | − | + |

| 2306pncO::pJDO3 | − | + |

| 2306ΔpncR-K | + | − |

| 2306pncP::pJDP4 | + | − |

The mutants were also used as indicator strains in order to see whether they are able to display immunity against the bactericidal activity of wild-type strain 2306 (Table 5). All three single-gene mutants were sensitive to the parental strain, in agreement with previous reports that expression of the immunity proteins depends on a functional SpiRH system (13) and also indicating that pncO is involved in the immunity response. The bacteriocin deletion mutant, however, was resistant to the wild-type 2306 strain, confirming the putative role of pncO in the immunity response.

PncE gene in S. pneumoniae 2306.

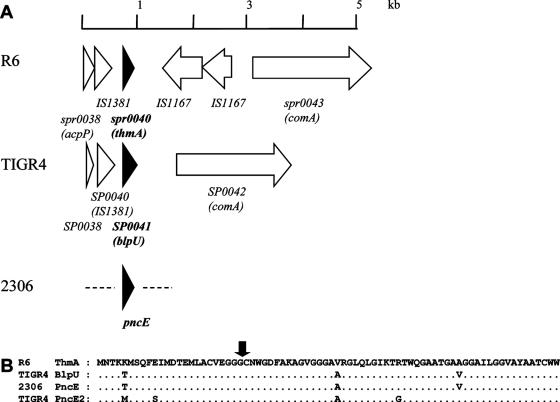

In order to explain the apparent bacteriocin-positive phenotype of the bacteriocin deletion mutant 2306ΔpncR-K, we searched for potential bacteriocin genes located elsewhere in the chromosome. Upstream of the comAB operon both the R6 and TIGR4 strains contain a bacteriocin gene (SP0041 [blpU] and spr0040, respectively) which is almost identical to the TIGR4 PncE gene in the bacteriocin cluster (pncE2), including upstream regions homologous to putative SpiR-regulated sites (13). The flanking regions are distinct (Fig. 4). A DNA fragment could indeed be amplified from 2306 DNA containing a PncE gene identical to the TIGR4 pncE2 gene (Fig. 2). However, attempts to determine the chromosomal location of pncE in 2306 with primers corresponding to flanking regions of pncE2 in the TIGR4 or R6 genome failed, probably due to highly variable sequences in this location.

FIG. 4.

(A) Comparison of the upstream region of the comA gene containing the pncE gene in S. pneumoniae R6 and TIGR4. The pncE gene is indicated by a solid arrowhead. The genes according to the annotation of the R6 and TIGR4 genomes are indicated. (B) Alignment of the peptide sequences. The arrow indicates the C39 processing site.

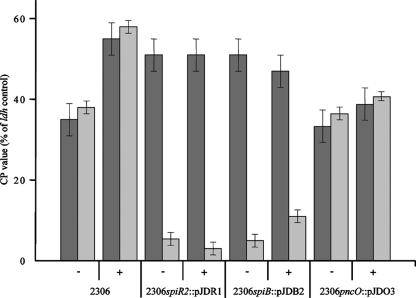

We then investigated whether this gene is expressed in strain 2306 and its mutant derivatives in liquid culture using RT-PCR (Fig. 5); pncJ was used as control. A gene product could be targeted with pncE-specific oligonucleotides, not only in control strains R6 and TIGR4 (not shown) but also in the 2306 wild-type strain and its mutant derivatives (Fig. 5). In contrast, only a pncJ product was obtained with the parent strain, as expected. In all cases, the pncE expression was the same order of magnitude as the expression of pncJ in 2306 (Fig. 5) or of pncI and pncJ in TIGR4 (not shown). When the cells were challenged with the 2306 SpiP peptide, expression of pncJ was induced in the wild type and to a lesser degree in the spiB mutant, also due to complementation of the defect in SpiP export but not in the spiR mutant. Melting curve analyses confirmed the presence of a pncJ-specific transcript in each case. However, no increase in the pncE product was seen, indicating that there is a high level of SpiR-independent expression of this gene. We concluded that the bacteriocin activity seen in mutant 2306ΔpncR-K is due to production of PncE, but it should be mentioned that direct comparison between the functional assay that relies on growth in agar plates and gene expression in liquid media is not possible.

FIG. 5.

Expression of the bacteriocin genes pncE and pncJ in strain 2306 and mutants. Gene expression was determined by RT-PCR. The bars indicate CP values relative to the CP values of the control gene ldh (lactate dehydrogenase), which was defined as 100%. Minus and plus signs indicate the absence and presence of SpiP during cellular growth, respectively. Dark gray bars, pncE; light gray bars, pncJ product.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we present evidence that S. pneumoniae produces bacteriocin-like activity directed not only against other strains of the same species but also against closely related streptococci, such as S. mitis, S. oralis, S. salivarius, and S. pyogenes, all of which are colonizers of the upper respiratory tract and the oral cavity. However, the species that appeared to be the most suitable indicators for the pneumococcal bacteriocins were M. luteus, which is common in soil and can also be isolated from skin, and L. lactis, which is found in dairy products and plants. No activity was observed against other gram-positive bacteria more distantly related to S. pneumoniae, such as Listeria, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and Bacillus strains, or against a gram-negative Pseudomonas strain. We have investigated only three S. pneumoniae bacteriocin producers, and a screen with many more strains is needed to obtain a general picture of the spectrum of target species.

The ability to produce bactericidal substances and the host spectrum vary considerably among different S. pneumoniae strains, which is reflected by the enormous genetic variability of the bacteriocin clusters, confirming results obtained by previous genomic comparisons of streptococci (20). In addition to genes encoding putative double-glycine bacteriocins and immunity proteins, two proteases belonging to the CAAX family are present, and two isolates contain transposase fragments (Fig. 1). We stress that the double-glycine leader peptide is not a sufficient marker for a bacteriocin. Similar leaders occur in peptide pheromones, such as S. pneumoniae ComC, and curiously also in the Streptococcus mutans bacteriocin immunity protein BIP (34).

The fact that with the TIGR4ΔpncA-N mutant no inhibitory effect was observed in the biological assay strongly suggests that only the pnc locus is responsible for bacteriocin production (Fig. 3). However, the presence of a bacteriocin cluster alone is apparently not sufficient for the production of functional bacteriocins under the conditions employed here. This is exemplified by the bacteriocin-negative phenotype of the Hu15 strain, which contains three putative bacteriocin genes, including the putative regulatory region, and by the heterogeneity of the Spain23F-1 clone in terms of bacteriocin activity, although all members tested here apparently contained the same cluster, as indicated by PCR analysis and by sequence analysis of two strains. Also, the streptococcal indicator strains used here are not necessarily representatives of the species, and their genetic makeup, including defense mechanisms against bacteriocins, may also vary. The complex situation is further indicated by the 2306ΔpncR-K mutant, which showed activity even though all bacteriocin genes in the cluster were deleted. Although we could identify another putative bacteriocin gene, pncE, in this strain, its location on the chromosome remained unclear, perhaps because of extensive genome rearrangements in its flanking regions, as seen in theTIGR4 genome compared to the R6 genome. In these two strains pncE is located upstream of the comAB operon (SP0041 [bplU] and spr0040, respectively) in a variable region which includes transposase gene fragments. The fact that the 2306ΔpncR-K mutant expresses immunity against the parental strain is also puzzling, suggesting that downstream gene products are involved in this phenotype. Since immunity is abolished in the 2306ΔpncO mutant whereas it is not abolished in the 2306ΔpncP mutant, either the CAAX protease PncO itself or the putative membrane protein PncQ must be responsible for the expression of immunity in this strain.

Two additional bacteriocins, CibA and CibB, have been described (11, 37), which are part of the competence regulon (40), and the cognate immunity protein CibC could also play a role in the response to the Pnc bacteriocins.

The lengths of the secreted bacteriocin peptides vary from 26 amino acids (PncV) to 66 amino acids (PncD). We hesitate to predict functionality for all putative bacteriocins in this cluster, since the many recombination events that occurred in this region as deduced from the presence of several repetitive sequences and relicts of a transposase might have resulted in artificial genes and gene products. Although most of these genes are likely to be transcribed as shown recently (13), it is not clear whether all of them are processed and exported or whether the actual products are functional. A clear example where rearrangements might produce a nonsense protein is represented by pncW (corresponding to R6 spr0470), where the repetitive sequence coding for the leader peptide of the bacteriocins is fused at the 5′ end of a frame, creating a putative ORF with a mutated (e.g., nonfunctional) cleavage motif.

Strains TIGR4 and 2306 differ not only in the bacteriocin cluster but also in the genetic makeup of the spiABCD genes encoding the dedicated transporter for the SpiP peptide, the signaling molecule responsible for induction of the bacteriocin cluster. However, since both strains show bacteriocin activity, the SpiABCD apparatus appears to function equally well in them. We found a third variant of these genes in the unfinished genome of the serotype 6B strain 670, where only one ORF covers the spiABC region. These three strains all contain distinct spiA alleles (Fig. 1) (38), but whether this is related to the differences in the makeup of the ABC transporter is not clear. The importance of the regulatory system for the production of functional bacteriocin became evident in the mutant with a disrupted SpiR2response regulator, confirming previous results which showed that induction of the bacteriocin gene cluster was induced upon addition of the peptide pheromone (12, 13, 38). The SpiR2 binding sites are part of a large sequence repeat of variable length that occurs, e.g., in TIGR4 four times and that is also part of the operons of the other bacteriocin clusters.

Recently, bacteriocin-like activity depending on the presence of the bacteriocin cluster was reported in a clinical isolate but not in the TIGR4 strain (12). In contrast to the previous report, we found activity in the TIGR4 strain, probably because of the different in vitro conditions. For example, we observed that bacteriocin production can readily be detected at 35°C, whereas at 37°C the TIGR4 strain had a negative phenotype and 2306 had a clearly reduced phenotype. Differences in the expression of putative bacteriocin immunity during biofilm formation relative to that in planktonic cells have been observed in S. mutans (34).

Human carriers are typically infected with one pneumococcal strain which remains in the nasopharynx for some months before it is replaced by another strain or disappears (17). The mechanisms by which carrier strain switching occurs are unclear, but direct competition between pneumococcal strains in mixed infections has been observed using a bacteriocin-producing strain and a mutant with a deleted bacteriocin cluster (12). Although the mutant was able to grow in the mouse nasopharynx normally, it was unable to compete with its parent strain. Our observation of interspecies bacteriocin-like activity strongly suggests that bacteriocin production is an important factor for the pneumococcus to compete with the resident flora as well.

Biofilm formation, genetic competence, and bacteriocin activity appear to be closely linked in streptococci (29). In this context it is important that we did not observe bacteriocin production at 37°C and observed it only at 35°C, conditions that are favorable for biofilm formation and resemble the natural environment of the upper nasopharynx (49). Bacteriocin production in Streptococcus gordonii and S. mutans appears to be controlled by the competence regulon (23, 48), and competence favors growth in biofilms in Streptococcus intermedius (36). For efficient DNA uptake during the state of competence it is important to ensure that DNA is available in the surrounding environment, as suggested previously (29), and interspecies signaling mediated by lantibiotic bacteriocins has been described for S. salivarius and S. pyogenes (47). During the state of competence in S. pneumoniae, the cibABC bacteriocin system is induced, which is involved in the induction of autolysis in a subpopulation of noncompetent cells, a process termed allolysis (19, 25, 37, 44). The ability to produce a whole set of bacteriocins enhances the ability to colonize not only by killing competing bacteria but also by increasing the availability of foreign DNA for horizontal gene transfer events and is therefore directly coupled with the evolution of pathogenesis. The enormous variation observed for the pnc cluster, which documents the genetic mobility in this region, probably reflects this selective advantage, leaving the target organisms little chance to evolve defense mechanisms effective against every set of bacteriocins that they might encounter.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karsten Mayr for sequencing the F4 cluster, Laurent Gutman for providing French isolates of the Spain23F-1 clone, and Sonja Schröck from the NBC for help with DNA sequence analysis.

This work was supported by the EU (grant LSHM-CT-2003-503413), the Stiftung Rheinland Pfalz für Innovation (grant 0580), and the Forschungsschwerpunkt Biotechnologie at the University of Kaiserslautern.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaberge, I. S., J. Eng, G. Lermark, and M. Lovik. 1995. Virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae in mice: a standardized method for preparation and frozen storage of the experimental bacterial inoculum. Microb. Pathog. 18: 141-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alloing, G., C. Granadel, D. A. Morrison, and J.-P. Claverys. 1996. Competence pheromone, oligopeptide permease, and induction of competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 21: 471-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avery, O. T., C. M. MacLeod, and M. McCarty. 1944. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types. Induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from pneumococcus type III. J. Exp. Med. 79: 137-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnboim, H. D., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7: 1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brückner, R., M. Nuhn, P. Reichmann, B. Weber, and R. Hakenbeck. 2004. Mosaic genes and mosaic chromosomes—genomic variation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294: 157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carver, T. J., K. M. Rutherford, M. Berriman, M.-A. Rajandream, B. Barrell, and J. Parkhill. 2005. ACT: the Artemis comparison tool. Bioinformatics 21: 3422-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, J.-D., and D. A. Morrison. 1988. Construction and properties of a new insertion vector, pJDC9, that is protected by transcriptional terminators and useful for cloning of DNA from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Gene 64: 155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claverys, J.-P., and L. S. Havarstein. 2002. Extracellular-peptide control of competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Front. Biosci. 7: 1798-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corpet, F. 1988. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16: 10881-10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagkessamanskaia, A., M. Moscoso, V. Hénard, S. Guiral, K. Overweg, M. Reuter, B. Martin, J. Wells, and J.-P. Claverys. 2004. Interconnection of competence, stress and CiaR regulons in Streptococcus pneumoniae: competence triggers stationary phase autolysis of ciaR mutant cells. Mol. Microbiol. 51: 1071-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawid, S., A. M. Roche, and J. N. Weiser. 2007. The blp bacteriocins of Streptococcus pneumoniae mediate intraspecies competition both in vitro and in vivo. Infect. Immun. 75: 443-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Saizieu, A., C. Gardès, N. Flint, C. Wagner, M. Kamber, T. J. Mitchell, W. Keck, K. E. Amrein, and R. Lange. 2000. Microarray-based identification of a novel Streptococcus pneumoniae regulon controlled by an autoinduced peptide. J. Bacteriol. 182: 4696-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diep, D. B., L. S. Håvarstein, and I. F. Nes. 1995. A bacteriocin-like peptide induces bacteriocin synthesis in Lactobacillus plantarum C11. Mol. Microbiol. 18: 631-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diep, D. B., O. Johnsborg, P. A. Risøen, and I. F. Nes. 2001. Evidence for dual functionality of the operon plnABCD in the regulation of bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum. Mol. Microbiol. 41: 633-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eijsink, V. G., L. Axelsson, D. B. Diep, L. S. Havarstein, H. Holo, and I. F. Nes. 2002. Production of class II bacteriocins by lactic acid bacteria; an example of biological warfare and communication. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 81: 639-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Rodriguez, J. A., and M. J. Fresnadillo Martinez. 2002. Dynamics of nasopharyngeal colonization by potential respiratory pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50(Suppl. S2): 59-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon, D., C. Abajian, and P. Green. 1998. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8: 195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guiral, S., T. J. Mitchell, B. Martin, and J.-P. Claverys. 2005. Competence-programmed predation of noncompetent cells in the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae: genetic requirements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 8710-8715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hakenbeck, R., N. Balmelle, B. Weber, C. Gardes, W. Keck, and A. de Saizieu. 2001. Mosaic genes and mosaic chromosomes: intra- and interspecies variation of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 69: 2477-2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakenbeck, R., and H. Hof. 1991. Relatedness of penicillin-binding proteins from various Listeria species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 84: 191-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hechard, Y., and H. G. Sahl. 2002. Mode of action of modified and unmodified bacteriocins from Gram-positive bacteria. Biochimie 84: 545-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heng, N. C. K., J. R. Tagg, and G. R. Tompkins. 2007. Competence-dependent bacteriocin production by Streptococcus gordonii DL1 (Challis). J. Bacteriol. 189: 1468-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, Jr., J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D.-J. Fu, W. Fuller, C. Geringer, R. Gilmour, J. S. Glass, HJ. Khoja, A. R. Kraft, R. E. Lagace, D. J. LeBlanc, L. N. Lee, E. J. Lefkowitz, J. Lu, P. Matsushima, S. M. McAhren, M. McHenney, K. McLeaster, C. Q. Mundy, T. I. Nicas, F. H. Norris, J. O'Gara, R. B. Peery, G. T. Robertson, P. Rockey, P.-M. Sun, J. E. Winkler, Y. Yang, M. Young-Bellido, G. Zhao, C. A. Zook, R. H. Baltz, S. R. Jaskunas, P. R. J. Rosteck, P. L. Skatrud, and J. I. Glass. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183: 5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kausmally, L., O. Johnsborg, M. Lunde, E. Knutsen, and L. S. Havarstein. 2005. Choline-binding protein D (CbpD) in Streptococcus pneumoniae is essential for competence-induced cell lysis. J. Bacteriol. 187: 4338-4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilian, M., L. Mikkelsen, and J. Henrichsen. 1989. Taxonomic study of viridans streptococci: description of Streptococcus gordonii sp. nov. and emended descriptions of Streptococcus sanguis (White and Niven 1946), Streptococcus oralis (Bridge and Sneath 1982), and Streptococcus mitis (Andrewes and Horder 1906). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39: 471-484. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knutsen, E., O. Ween, and L. S. Havarstein. 2004. Two separate quorum-sensing systems upregulate transcription of the same ABC-transporter in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 186: 3078-3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kochanowski, B., W. Fischer, N. Iida-Tanaka, and I. Ishizuka. 1993. Isomalto-oligosaccharide-containing lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus sanguis. Basic structure. Eur. J. Biochem. 214: 747-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreth, J., J. Merritt, W. Shi, and F. Qi. 2005. Co-ordinated bacteriocin production and competence development: a possible mechanism for taking up DNA from neighbouring species. Mol. Microbiol. 57: 392-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lacks, S., and R. D. Hotchkiss. 1960. A study of the genetic material determining an enzyme activity in pneumococcus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 39: 508-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanie, J. A., W. L. Ng, K. M. Kazmierczak, T. M. Andrzejewski, T. M. Davidsen, K. J. Wayne, H. Tettelin, J. I. Glass, and M. E. Winkler. 2007. Genome sequence of Avery's virulent serotype 2 strain D39 of Streptococcus pneumoniae and comparison with that of unencapsulated laboratory strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 189: 38-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeBlanc, D. J., L. N. Lee, and J. M. Inamine. 1991. Cloning and nucleotide base sequence analysis of a spectinomycin adenyltransferase AAD(9) determinant from Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35: 1804-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mascher, T., M. Merai, N. Balmelle, A. de Saizieu, and R. Hakenbeck. 2003. The Streptococcus pneumoniae cia regulon: CiaR target sites and transcription profile analysis. J. Bacteriol. 185: 60-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumoto-Nakano, M., and H. K. Kuramitsu. 2006. Role of bacteriocin immunity proteins in the antimicrobial sensitivity of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188: 8095-8102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pei, J., and N. V. Grishin. 2001. Type II CAAX prenyl endopeptidases belong to a novel superfamily of putative membrane-bound metalloproteases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26: 275-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petersen, F. C., D. Pecharki, and A. A. Scheie. 2004. Biofilm mode of growth of Streptococcus intermedius favored by a competence-stimulating signaling peptide. J. Bacteriol. 186: 6327-6331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson, S. N., C. K. Sung, R. Cline, B. V. Desai, E. C. Snesrud, P. Luo, J. Walling, H. Li, M. Mintz, G. Tsegaye, P. C. Burr, Y. Do, S. Ahn, J. Gilbert, R. D. Fleischmann, and D. A. Morrison. 2004. Identification of competence pheromone responsive genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae by use of DNA microarrays. Mol. Microbiol. 51: 1051-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reichmann, P., and R. Hakenbeck. 2000. Allelic variation in a peptide-inducible two component system of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190: 231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reichmann, P., E. Varon, E. Günther, R. R. Reinert, R. Lütticken, A. Marton, P. Geslin, J. Wagner, and R. Hakenbeck. 1995. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Germany: genetic relationship to clones from other European countries. J. Med. Microbiol. 43: 377-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rimini, B., B. Jansson, G. Feger, T. C. Robert, M. de Francesco, A. Gozzi, F. Faggioni, E. Domenici, D. M. Wallace, N. Frandsen, and A. Polissi. 2000. Global analysis of transcription kinetics during competence development in Streptococcus pneumoniae using high density DNA arrays. Mol. Microbiol. 36: 1279-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Beato, A. R., E. Garcia, R. Lopez, and J. L. Garcia. 1997. Identification and characterization of IS1381, a new insertion sequence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 179: 2459-2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schleifer, K. H., W. E. Kloos, and A. Moore. 1972. Taxonomic status of Micrococcus luteus (Schroeter 1872) Cohn 1872: correlation between peptidoglycan type and genetic compatibility. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 22: 224-227. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sibold, C., J. Wang, J. Henrichsen, and R. Hakenbeck. 1992. Genetic relationship of penicillin-susceptible and -resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated on different continents. Infect. Immun. 60: 4119-4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinmoen, H., A. Teigen, and L. S. Havarstein. 2003. Competence-induced cells of Streptococcus pneumoniae lyse competence-deficient cells of the same strain during cocultivation. J. Bacteriol. 185: 7176-7183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swenson, J. M., N. C. Clark, D. F. Sahm, M. J. Ferraro, G. Doern, J. Hindler, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, L. B. Reller, and M. P. Weinstein. 1995. Molecular characterization and multilaboratory evaluation of Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 51299 for quality control of screening tests for vancomycin and high-level aminoglycoside resistance in enterococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33: 3019-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293: 498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Upton, M., J. R. Tagg, P. Wescombe, and H. F. Jenkinson. 2001. Intra- and interspecies signaling between Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus pyogenes mediated by SalA and SalA1 lantibiotic peptides. J. Bacteriol. 183: 3931-3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Ploeg, J. R. 2005. Regulation of bacteriocin production in Streptococcus mutans by the quorum-sensing system required for development of genetic competence. J. Bacteriol. 187: 3980-3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waite, R. D., J. K. Struthers, and C. G. Dowson. 2001. Spontaneous sequence duplication within an open reading frame of the pneumococcal type 3 capsule locus causes high-frequency phase variation. Mol. Microbiol. 42: 1223-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ween, O., P. Gaustad, and L. S. Håvarstein. 1999. Identification of DNA binding sites for ComE, a key regulator of natural competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 33: 817-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wegmann, U., M. O'Connell-Motherway, A. Zomer, G. Buist, C. Shearman, C. Canchaya, M. Ventura, A. Goesmann, M. J. Gasson, O. P. Kuipers, D. van Sinderen, and J. Kok. 2007. Complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363. J. Bacteriol. 189: 3256-3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wheeler, D. L., D. M. Church, S. Federhen, A. E. Lash, T. L. Madden, J. U. Pontius, G. D. Schuler, L. M. Schrim, E. Sequeira, T. A. Tatusova, and L. Wagner. 2003. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 28-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wunsch, P., M. Herb, H. Wieland, U. M. Schiek, and W. G. Zumft. 2003. Requirements for Cu(A) and Cu-S center assembly of nitrous oxide reductase deduced from complete periplasmic enzyme maturation in the nondenitrifier Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 185: 887-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pCU19 vectors. Gene 33: 103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]