Abstract

Antiviral CD8+ T cells are thought to play a significant role in limiting the viremia of human and simian immunodeficiency virus (HIV and SIV, respectively) infections. However, it has not been possible to measure the in vivo effectiveness of cytotoxic T cells (CTLs), and hence their contribution to the death rate of CD4+ T cells is unknown. Here, we estimated the ability of a prototypic antigen-specific CTL response against a well-characterized epitope to recognize and kill infected target cells by monitoring the immunodominant Mamu-A*01-restricted Tat SL8 epitope for escape from Tat-specific CTLs in SIVmac239-infected macaques. Fitting a mathematical model that incorporates the temporal kinetics of specific CTLs to the frequency of Tat SL8 escape mutants during acute SIV infection allowed us to estimate the in vivo killing rate constant per Tat SL8-specific CTL. Using this unique data set, we show that at least during acute SIV infection, certain antiviral CD8+ T cells can have a significant impact on shortening the longevity of infected CD4+ T cells and hence on suppressing virus replication. Unfortunately, due to viral escape from immune pressure and a dependency of the effectiveness of antiviral CD8+ T-cell responses on the availability of sufficient CD4+ T cells, the impressive early potency of the CTL response may wane in the transition to the chronic stage of the infection.

It is generally thought that virus-specific CD8+ T cells play a significant role in limiting viremia in CD4+ T-cell-tropic human and simian immunodeficiency virus (HIV and SIV, respectively) infections, resulting in an emphasis on generating high-level antiviral cellular immune responses in current efforts to develop effective HIV vaccines (20). Antiviral CD8+ T cells recognize short peptide sequences (epitopes) derived from the intracellular processing of viral proteins and presented on the surface of virus-infected cells in the context of host class I major histocompatibility complexes (MHC). While cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) cannot directly prevent the infection of host target cells, they can inhibit virus replication by recognizing and killing infected cells prior to the completion of the virus life cycle and the production of progeny virions. Evidence to support the salutary influence of antiviral CD8+ T cells in controlling SIV or HIV replication includes findings from studies of humans with long-term nonprogressing HIV infection and experimental CD8 depletion studies performed with SIV-infected rhesus macaques and the temporal diminution of virus replication with the emergence of CTL responses during acute infection (28, 30, 41, 42, 45). However, there appears to be no clear relationship between the magnitude or breadth of the CTL response and set point virus replication levels during chronic infection (1, 6, 39). Furthermore, HIV-specific CTLs fail to eliminate the virus and are only very rarely able to durably control its replication sufficiently to prevent the eventual depletion of CD4+ T cells (42). In light of this, a major question remains regarding the contribution of CD8+ T cells to the death of infected cells during both acute and chronic HIV and SIV infections.

Among the evidence used to argue in favor of the significance of CTLs in the control of HIV infection is the observed rapid fixation of mutations in epitopes targeted by cellular immune responses. Numerous studies have shown that both HIV and SIV are able to escape from specific CD8+ T-cell recognition during acute and chronic phases of infection (22). However, these observations do not necessarily imply that HIV-specific CTLs are highly effective at killing infected cells, and there currently is a lack of in vivo measures of CD8+ T-cell effectiveness. Indeed, a within-host estimation of the impact of a single part of a multifactorial immune response, involving antibodies, B cells, CD4+ T cells, dendritic cells, and various other innate responses in addition to CTLs, is difficult in a dynamic system as complex as that of HIV or SIV infection. Although ex vivo assays to measure CD8+ T-cell functionality exist, they may not accurately reflect the contribution of CD8+ T cells to the effectiveness of antiviral immune responses to HIV or SIV and how this contribution may change during the course of infection.

In this study, we developed a mathematical model to describe the outgrowth of CD8 T-cell epitope mutants in SIV-infected Mamu-A*01-restricted rhesus macaques. We monitored virus sequence data for escape mutations in the immunodominant epitope Tat28-35 SL8 and tetramer-positive CTLs specific for this epitope over time during infection with SIVmac239, a pathogenic molecular clone-derived SIV isolate (32). The macaques studied were either unmanipulated or treated with the recombinant fusion protein CTLA4-Ig and an anti-CD40L monoclonal antibody to block major costimulatory pathways that involve interactions between B7 and CD28 and between CD40 and CD40 ligand (CD40L), respectively, during acute SIV infection to transiently block the generation of SIV-specific humoral and cellular immune responses (19). The comparison of the control SIV infections to those in which CD4+ T-cell help in mounting CD8+ T-cell responses was potently inhibited allowed us to assess the role that CD4+ T cells play in determining both the level and potency of SIV-specific CTLs. By fitting our model to changes in mutant frequency over time, we were able to estimate the killing rate of Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T cells. Unlike previous studies (4, 15, 52), our incorporation of the Tat SL8-specific CTL measurements of individual animals into our model has allowed us to distinguish between the quality, or lytic capability, of the CD8+ T-cell response and the quantity, or levels, of virus-specific CD8+ T cells raised.

Our analysis shows that at peak levels during the acute infection period, Tat SL8-specific CTLs exert a potent impact on infected CD4+ T-cell longevity prior to the fixation of viral escape variants. Given that highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) represents the best available guidepost to gauge antiviral potency, we sought to compare the estimated effectiveness of the peak Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T-cell response at suppressing viral replication with that of HAART, as measured for individual hosts chronically infected with HIV or SIV (9, 38). This comparison suggests that with sufficiently high peak CTL levels, the antiviral potency of the specific Tat SL8 CTL response can be up to half of the efficacy of HAART. Given the importance of fitness costs associated with viral escape in determining both the rate at which frequencies of mutant viruses increase and the persistence of escape variants at the population level, we expanded our model to allow for the estimation of the fitness of the mutant relative to that of the wild type. We find that there is no fitness cost associated with escape mutations in the SL8 epitope, confirming previous experimental results (16).

In summary, here we provide quantitative estimates of the killing rate constant of SIV-specific CD8+ T cells from the increase in viral CTL escape mutants by using a unique data set. Overall, these data help describe the killing capacity of specific CTLs on a per-CD8+-T-cell level and, in addition, help us to determine the in vivo effectiveness of an epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell response as a whole by comparing its effectiveness to that of HAART. These results help illuminate the requirements that will need to be met if polyclonal CTL responses, whether naturally occurring or elicited by vaccination prior to infection, are to be able to exert durable control of HIV replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data set.

The experiment that generated the data set analyzed in this study has been described previously (19). Briefly, eight rhesus macaques were infected with pathogenic SIVmac239 (day 0), of which four controls were left untreated and four were treated with CTLA4-Ig and αCD40L to block costimulation-signaling pathways in SIV antigen-specific T and B cells during acute SIV infection. The macaques studied possessed the MHC class I allele Mamu-A*01, enabling the longitudinal tracking of Tat SL8-specific CTLs in the peripheral blood using MHC tetramers. The SIV viral load was determined by quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR, and the number of Ki67+ CD4+ T cells was measured using flow cytometry. The sequencing of the tat exon 1 and determination of viral escape on days 13, 16, 20, and 42 are described elsewhere (19). The RNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing of tat at the additional time points of days 27 and 34 were done in the same way using primers SIV6900R and SIV6511F (2). For 33 out of 40 time points, 17 to 20 cDNA clones of the tat exon were sequenced. The average number of cDNA clones sequenced for the remaining time points was 13 (minimum of 10 sequences). The sequence data were analyzed using ClustalX (48) and the BioEdit sequence alignment editor (24).

Model.

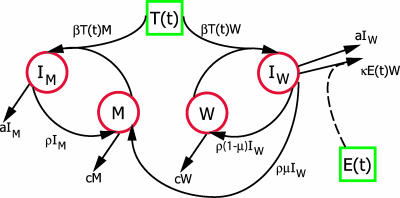

A schematic depicting the mathematical model is shown in Fig. 1. The compartmental model of in vivo virus dynamics is a modification of models previously described (18, 43). It includes a viral population with the wild-type CD8+ T-cell epitope sequence, W, and with epitope escape mutants, M. Both virus types are able to infect target cells, T, at a rate of β, generating cells infected with the wild-type virus, IW, or variant virus, IM. These infected cells produce virus at rate ρ per cell. Free virions are cleared from the blood at rate c. Initially, all virus is wild type, with mutant virus generated at a mutation rate, μ, per epitope per replication cycle from cells infected with wild-type virus. While all infected cells die at an intrinsic rate, a, only the wild-type-virus-infected cells are recognized and killed by CTL effector cells, E, at rate κ microliters cell−1 day−1. The model is given by the following set of ordinary differential equations:

|

(1) |

Given that the clearance rate of virions, c, is greater than the intrinsic death rate of infected cells, a, the virus populations W and M will be in a quasi-steady state with IW and IM. Equation 1 can be reduced to the following:

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

The system of equations was solved numerically using the lsoda routine in the odesolve package in R, version 2.4.1 (27). Parameters estimated from published data (Table 1) and initial population sizes of IM = 0 cells/μl and IW = 0.001 cells/μl were used. The parameter μ in our model denotes the rate at which viral mutants arise that are no longer recognized by the CTL response against the wild-type Tat SL8 epitope. We calculated this rate as follows. First, we assumed that for SIV the mutation rate per base pair and per replication cycle is the same as that estimated for HIV, namely 3.4 × 10−5 (37). Second, assuming a uniform mutation rate across the entire SIV genome, we calculated the rate of a mutation occurring in the RNA sequence encoding the Tat SL8 epitope. This Tat epitope is 8 amino acids long and is encoded by 24 nucleotides. Hence, the mutation rate per 8-amino-acid sequence is 8.1 × 10−4. However, only approximately 70% of mutations will lead to a change in the translated protein. If we assume that all nonsynonymous mutations are escape mutations, the rate at which escape mutations in Tat SL8 are generated is about 5.7 × 10−4 per cycle. Lastly, assuming that a replication cycle of SIV lasts, on average, 1 day (29), we estimate that μ = 5.7 × 10−4 day−1. In this calculation, we neglected back mutations because they occur at very low rates and will therefore only marginally affect the proportion of escape mutants.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the model used to describe the within-host dynamics of viral epitope escape due to selection pressure by specific CTLs. The four variables modeled explicitly (red circles) are wild-type virus, W, epitope escape mutants, M, cells infected with wild-type virus, IW, and cells infected with mutant virus, IM. The target cell, T(t), and effector cell, E(t), functions (green squares) are taken from the data and hence vary between animals.

TABLE 1.

Fixed parameters of the model

| Parameter | Definition | Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| β | Infection rate | 9 × 10−4 day−1 | 48 |

| ρ | Burst size or production rate of virions per productively infected cell | 1,000 day−1 | 24, 28 |

| μ | Proportion of virus released from cell infected with wild-type virus that are mutated in epitope | 1.9 × 10−4 epitope−1 replication cycle−1 | 39 |

| a | Death rate of infected cells | 1.5 day−1 | 9 |

| c | Clearance rate of free virions | 30 day−1 | 47 |

Further, we assume that escape of mutants is complete (i.e., there is no cross-reactivity with existing CTLs) and all nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions in the epitope constitute escape mutants. We also assume that the contribution of back mutations from the mutant epitope to the wild type to the proportion of wild-type sequences will be negligible and hence do not include back mutation in our model.

Of the variables included in the model, both the number of uninfected target cells and the number of CD8+ T-cell effectors are important determinants of the rate of viral replication. Rather than mathematically describing the target cell and CD8+ T-cell dynamics, we incorporated target cell- and epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell levels as time-dependent functions, T(t) and E(t), respectively, obtained by linear interpolation of Ki67+ CD4+ T-cell- and Tat SL8-specific CTL measurements (Fig. 2 and data not shown). This enables us to account for monkey-specific variations in the levels of targets and effectors. It also allows the incorporation of indirect effects of the costimulatory (CS) blockade on viral replication via a reduction in the number of proliferating target cells available for productive infection.

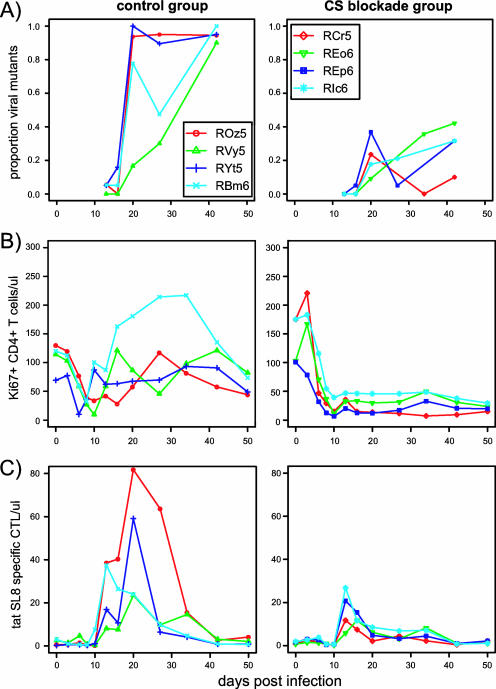

FIG. 2.

Changes in the proportions of viral escape mutants (A), Ki67+ CD4+ T cells (per microliter) (B), and Tat SL8-specific CTLs (per microliter) p.i. (C) measured in the blood for control and CS blockade animals. The images shown in panels B and C have been published previously (19).

Fitness cost of escape.

To make our model more generally applicable, we included a relative fitness cost for the viral escape mutant by modifying the model. We introduced a term, γ, that takes values between 0 and 1, reducing the replication rate of the mutant virus relative to that of the wild type. When γ = 1, there is no difference in fitness between the wild-type and escape virus; when γ = 0, the escape virus cannot grow at all. Equation 3 becomes the following:

|

(4) |

Model fittings.

To fit our model (equations 2 and 3) to the data on virus escape, we first calculate the predicted fraction of escape mutant virus, fαipred(κ), of animal a at time i for a certain value of the parameter κ, which measures the efficacy of the CD8+ T cells against Tat SL8 with the following equation: faipred(κ) = IM(ti)/[IW(ti) + IM(ti)]. Note that the prediction faipred(κ) is based on the time-dependent levels of target cells, T(t), and Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T cells, E(t).

We then obtain the best estimate of the parameter κ by minimizing the residual sum of squares.

|

(5) |

G is either the CS blockade or control group of animals, and  is the fraction of escape mutant virus measured in animal a at time i. The fractions were transformed by arcsin √ to normalize their error distribution. Note that by minimizing the above expression we obtain one estimate of κ for each group and not one estimate for each animal. We chose to focus on group estimates rather than estimates for each individual animal, because our primary focus is the quantification of CTL efficacy across animals rather than interanimal differences in CTL efficacy.

is the fraction of escape mutant virus measured in animal a at time i. The fractions were transformed by arcsin √ to normalize their error distribution. Note that by minimizing the above expression we obtain one estimate of κ for each group and not one estimate for each animal. We chose to focus on group estimates rather than estimates for each individual animal, because our primary focus is the quantification of CTL efficacy across animals rather than interanimal differences in CTL efficacy.

To fit the extended model that incorporates a potential cost of escape (equations 2 and 4) to the data on virus escape, we proceed analogously. We first calculate the predicted fraction of escape mutant virus,  (κ,γ), of animal a at time i for a certain value of the parameters κ and γ, giving the equation

(κ,γ), of animal a at time i for a certain value of the parameters κ and γ, giving the equation  (κ,γ) = IM(ti)/[IW(ti) + IM(ti)]. We then obtain the best estimates of κ and γ similarly by minimizing with the following equation:

(κ,γ) = IM(ti)/[IW(ti) + IM(ti)]. We then obtain the best estimates of κ and γ similarly by minimizing with the following equation:

|

(6) |

The fitting routines were implemented in R, version 2.4 (27), using the function optim(). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) of the parameter estimates were obtained by a bootstrap method (11) using the function boot() in R with 199 bootstrap replicates.

RESULTS

Rapid escape of Tat SL8 epitope in the presence of specific CTLs.

In this study, we sought to characterize the evolution of viral epitopes recognized by specific antiviral CTLs. We focused on the Tat28-35 SL8 epitope, which is an immunodominant epitope recognized in Mamu-A*01 rhesus macaques. We monitored the frequency of viral Tat SL8 variants in eight macaques infected with the clonal virus strain SIVmac239. Four of the animals were treated with CTLA4-Ig and anti-CD40L monoclonal antibody, blocking T cell-dendritic cell costimulation pathways, and as a result they had severely abrogated CD4+ and CD8+ T- and B-cell responses, as previously described (19). The nucleotide sequences of up to 20 viral clones of tat were determined at day 13, 16, 20, 27, or 34 and at day 42 postinfection (p.i.) for all animals. We observed a progressive increase in viral diversity over time for Tat SL8. A total of 22 distinct mutants of Tat SL8 (STPESANL) emerged (Table 2). The most common variants had a single amino acid change, similar to antiretroviral drug-resistant HIV variants that emerge upon unsuccessful treatment with, for example, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (25). Of the epitope variants observed in all animals during the study, 15 of the mutations have been shown empirically to result in a 67 to 99% reduction in binding to the Mamu-A*01 MHC allele compared to that of the wild-type epitope (2) or constitute significant changes in amino acid size or charge or the third-position anchor residue (for the wild type, the residue is proline) (3). The five most frequent escape variants, which account for 91% of mutants observed during the study, all have been shown previously to be bona fide escape mutants (Table 2). The other epitope variants observed, although they have not been characterized, have characteristics of escape mutants. Hence, for the purpose of this analysis, it was assumed that all epitope variants that had nonsynonymous mutations in the Tat28-35 SL8 sequence were escape mutants.

TABLE 2.

Tat28-35 SL8 epitope escape mutant sequences observed during acute SIV infection in eight rhesus macaques across all time points

| Sequence type | Sequencea | No. of escape sequences observed | Escape characteristicb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | STPESANL | ||

| Mutant | P....... | 156 | ‡ |

| .I...... | 26 | ‡ | |

| .......P | 9 | ‡ | |

| ....L... | 6 | ‡ | |

| C....... | 3 | * | |

| .N...... | 2 | ||

| ...G.... | 2 | ||

| ......S. | 1 | ||

| ......D. | 1 | ||

| P......P | 1 | ‡ | |

| .....V.. | 1 | ||

| ..T..... | 1 | * | |

| IP.SRSM. | 1 | * | |

| .......Q | 1 | ‡ | |

| ....P... | 1 | * | |

| .....T.. | 1 | ||

| .ANLGEEI | 1 | * | |

| ......K. | 1 | ||

| F....... | 1 | * | |

| .......R | 1 | ‡ | |

| P..K.... | 1 | ‡ | |

| C...L... | 1 | ‡ |

Total number of mutants observed, 219. Total number of epitopes sequenced, 716.

In control animals, Tat SL8 viral escape occurs early in infection. By day 42 p.i., 90 to 100% of viral clones are escape mutants (Fig. 1A). The kinetics of viral escape mutant outgrowth is similar to the kinetics of outgrowth of antiretroviral monotherapy-resistant variants manifesting a low genetic barrier to the development of resistance (wherein a single or a few nucleotide changes, and the single or very limited codon alterations that result, are sufficient to engender high-level resistance to the antiviral effects of specific antiretroviral drugs) (12, 25). By contrast, in CS blockade animals, in which both the levels of Tat SL8-specific CTLs and proliferating CD4+ T-cell targets are lower, the level of Tat SL8 mutants remains below 42% (Fig. 1A). In addition, Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T cells decline in CS blockade animals, although the wild-type virus is still present, possibly indicating a loss of their function and durability in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help. The rapid escape from Tat-specific CTLs seen in control animals is consistent with previous observations (2). As in other studies, we do not see escape in the second immunodominant Mamu-A*01 epitope, Gag CM9, until 51 weeks p.i., and then only together with the compensatory mutations described previously (44 and data not shown). The escape of the Tat SL8 epitope is much more rapid than that described for other well-characterized CTL epitopes, including Gag CM9 in SIV or Env gp160, Tat CC8, and Vpr EI9 in HIV, which do not reach fixation until at least 20 weeks p.i. (8, 10, 44). This could be a reflection of a more immunodominant or more potent Tat SL8 CTL response or a lower genetic barrier of Tat SL8 to escape, or it could be that, unlike many epitopes targeted by virus-specific CTLs, the observed Tat SL8 escape variants have little or no fitness cost of escape (16, 36).

Estimating the killing rate of CD8+ T cells.

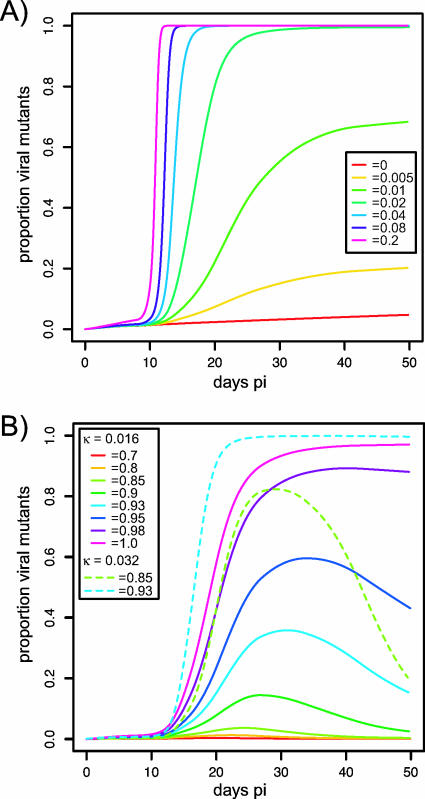

The increase in the fraction of escape mutants informs us about the efficacy of specific CTLs. Here, we developed a mathematical model to quantify the escape of a viral variant from CTL immune pressure (Fig. 2). Given that the only difference between escape and wild-type viruses is a particular epitope sequence, it is reasonable to assume that the reduction in death rate of mutant-infected cells is due to the lack of killing by epitope-specific CD8+ T cells. Although CTLs can have other means of affecting viral replication (e.g., by the production of cytokines and chemokines that exert antiviral effects), because this would affect both mutant and wild-type viruses equally, we disregard this function of cytotoxic T cells for the purpose of this analysis and focus only on the ability of CD8+ T cells to kill infected target cells by contact-dependent lysis following MHC-peptide recognition. Our model allows us to estimate the killing rate of specific CTLs, assuming that the two virus types do not otherwise differ in replication rates. The higher the killing rate of specific CD8+ T cells, the bigger the selective advantage of the escape variant and thus the more rapidly its frequency increases (Fig. 3A). Without CTL killing (κ = 0), the frequency of mutants increases only at the rate of mutation, μ. A crucial difference between modeling the escape of virus from CD8+ T cells and modeling selection pressure exerted by antiretrovirals, like the model developed previously (7), is that the changing levels of specific CTLs have to be incorporated to enable an accurate per-CTL killing rate estimate. Hence, we distinguish between the killing rate constant, κ, and the killing rate, which is defined as the killing rate constant, κ, multiplied by the number of cytotoxic T cells, E, at a given time point. Although others have estimated the CTL killing rates (4, 15, 52), here we provide in vivo estimates of CTL killing that take into account the temporal variation in CTL levels by incorporating data on the numbers of Tat SL8-specific (tetramer-positive) CD8+ T cells.

FIG. 3.

Simulation of viral escape mutant frequency using (A) different values of κ with no differences in replication rates (γ = 1) between wild-type and mutant viruses or (B) different values of γ with κ = 0.016 μl cell−1 day−1 (solid lines) and with κ = 0.032 μl cell−1 day−1 (dashed lines). Target and effector cell data used were from control animal RBm6.

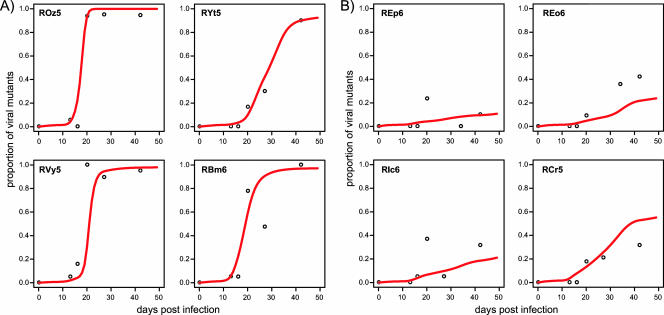

We fit our model to the proportion of Tat SL8 escape mutants during acute SIV infection of control and CS blockade macaques and estimated the killing rate constant, κ, of an SL8-specific CD8+ T cell. In our fittings, we control for differences of targets (Ki67+ CD4+ T cells) and effectors (Tat SL8-specific CTLs tracked by MHC class I tetramer staining) between animals and over time for each animal (the raw data used to obtain the interpolated functions of targets and effectors are available from the authors upon request). We thus fit individual animal data with a single estimate of κ for each group (see Materials and Methods), but similar estimates are obtained when animals are fitted singly (data not shown). We estimated that κ = 0.0161 μl cell−1 day−1 (95% CI, 0.005 to 0.0197 μl cell−1 day−1) for control macaques and κ = 0.0145 μl cell−1 day−1 (95% CI, 0.0107 to 0.0176 μl cell−1 day−1) for CS blockade macaques (Fig. 4). The poorer fits to REo6 and RCr5 are due to within-group variation and are a consequence of fitting all the group data points together. There was no significant difference between killing rate constants estimated for the two animal groups. Differences in the rate of increase for the mutant virus can be explained merely by the substantially (on average, 65%) lower overall CTL levels in CS blockade animals (Fig. 1C). This suggests that at least for the initial CD8+ T-cell response, limited CD4+ T-cell help does not impair the killing capacity of anti-Tat CTLs. However, the decline of Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T cells in CS blockade animals prior to the fixation of the escape variants clearly indicates that CTL responses emerging in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help are not maintained.

FIG. 4.

Model fits to the frequency of Tat SL8 escape mutants in (A) control animals, for which κ = 0.0161 μl cell−1 day−1 (95% CI, 0.005 to 0.0197 μl cell−1 day−1), and (B) CS blockade animals, for which κ = 0.0145 μl cell−1 day−1 (95% CI, 0.0107 to 0.0176 μl cell−1 day−1).

The κ estimates are very robust with regard to changes in other parameters of the model (data not shown). Changing individual parameters in the model by 20% changes the estimates of κ by less than 5%. This is due to the fact that the only difference between the frequency of mutant virus and that of wild-type virus is determined by the number of specific CTLs and any fitness costs, a useful advantage of our approach. Similarly, given that the number of potential target cells in the model is approximated by inclusion of only peripheral blood Ki67+ CD4+ T cells and that these cells may not be reflective of the overall population of cells that are infected with SIV during the primary infection period (33), we investigated the effect of increasing target cell numbers on our estimates of κ. Again, κ estimates are highly robust, even with a large (10,000-fold) increase in target cells. Furthermore, in light of recent evidence demonstrating that proportions of Ki67+ CD4+ cells in the blood closely mirror those found in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (21), which represent the major sources of virus production during the acute infection period (33, 54), estimates of the levels of potential target cells extant at successive times of acute infection that are based on sampling of peripheral blood cells alone are likely to provide a sufficiently accurate gauge of target cell availability for incorporation into this model. Although the time to emergence of an escape mutant is a stochastic process (34) that we approximate here by a deterministic one, our estimates depend primarily on the rate of increase of the mutant once it has emerged. An alternative model that assumes the preexistence of escape mutants, rather than their emergence by mutation, yields estimates of κ that are not significantly different from the ones we obtain above by assuming the emergence of escape by mutation. Further, the fact that SIV infections studied here were initiated with a homogeneous strain of virus derived from a molecular clone of SIV likely precludes the latter alternative. An additional caveat is that it is possible that not all of the escape variants confer 100% escape from Tat SL8-specific killing as we assume. Unfortunately, there are no experimental data available on whether these variants are partially recognized in vivo, but if partial CTL recognition of the epitope mutants does occur then we have underestimated κ.

No fitness cost of escape for Tat SL8 epitope mutants.

In addition to being determined by the killing rate of specific CD8+ T cells, the relative increase in the frequency of escape mutant virus can be affected by the reduction in replication rate of the mutant, i.e., a fitness cost of escape. We extended our model to include a parameter, γ, that decreases the growth rate of the mutant. When γ = 1, the growth rates of wild-type and escape virus are the same (fitness cost, 1 − γ = 0), while when γ = 0, the mutant is unable to grow (see Materials and Methods). Whether or not the fitness cost is large enough to prevent the increase of an escape mutant depends on the relative advantage the variant has by avoiding CTL killing and hence on the magnitude of the selection pressure that epitope-specific CD8+ T cells can exert. Figure 3B illustrates that for κ = 0.016 and a peak number of Tat SL8-specific CTLs of 37.4 cells/μl, the escape variant does not reach fixation even for a fitness cost as low as 1 − γ = 0.05. With large fitness costs, the mutant virus would be expected to reach fixation only if the killing rate is large enough to give the mutant an advantage great enough to outcompete the wild type or, alternatively, if the mutant acquires compensatory mutations that reduce its replicative cost. For κ = 0.016 and the particular CD8+ T-cell levels of the animal RBm6, a fitness cost of 1 − γ = 0.15 is sufficient to prevent the outgrowth of the mutant. In contrast, when the killing rate constant is higher, κ = 0.032, then the mutant virus can reach fixation with a higher fitness cost and the mutant will be able to outgrow the wild type at 1 − γ = 0.15. The model predicts that with a cost of escape, the frequency of the mutant declines when the levels of epitope-specific CD8+ T cells (and hence the selection pressure) decrease. Thus, there will be a reversion to the wild type (Fig. 3B).

To investigate whether our Tat SL8 mutants carry a fitness cost, we fitted the extended model to our data and determined γ. It was estimated that γ = 1.011 (95% CI, 0.939 to 1.341) for the control group and γ = 0.969 (95% CI, 0.867 to 1.174) for the CS blockade group. For both the CS blockade and control groups, γ was not significantly different from 1.0; thus, from our data, there is no evidence that Tat SL8 epitope escape variants suffer a reduction in replication rate.

DISCUSSION

During SIV infection of rhesus macaques, like in HIV infection of humans, more CD4+ T cells are dying than are replaced. This elevation of CD4+ T-cell turnover plays an essential role in HIV disease progression, although the detailed mechanisms underlying AIDS pathogenesis have yet to be fully elucidated (23). Furthermore, the relative contributions of viral cytopathicity, immune response-mediated lysis, activation-induced cell death, and bystander apoptosis to CD4+ T-cell death remain unclear and may differ at different times following infection (23). Here, we have presented a method to assess the quantitative impact of one of the contributors to the death of infected CD4+ T cells: killing by specific CD8+ T cells. Understanding the killing effectiveness of CTLs is of central importance to AIDS vaccine development efforts, in which the majority of candidates are based on the induction of antiviral CD8+ T-cell responses (20).

In this study, we use epitope escape data for Tat SL8 during SIVmac239 infection of rhesus macaques and a mathematical model incorporating measurements of epitope-specific CTLs to estimate the killing rate constant (κ) per Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T cell (E). Hence, we are able not only to quantify the strength of the selection pressure that CD8+ T cells exert on the virus but also to determine how this selection pressure changes over time as CTL levels change. This enables both comparisons of killing rate constants for different epitope-specific CTLs (their quality) as well as determining the impact that certain peak levels of specific CD8+ T cells (their quantity) can have on viral replication. This is of significant relevance, as it may aid in determining if vaccine-elicited CTL responses can be sufficiently potent to have a significant and durable impact on viral replication (wherein virus replication is controlled to a sufficiently low level that, as observed in the case of effective combination antiretroviral therapy, can preclude the emergence of resistant variants). We estimated that the killing rate, κE, is between 0.3 and 0.9 day−1, at peak CTL levels of between 23.5 and 81.8 Tat-specific CD8+ T cells per μl of peripheral blood, in control animals. In CS blockade macaques, the reduced number of Tat-specific CD8+ T cells raised (peak CTL numbers were between 11.7 and 26.8 cells/μl) resulted in a decreased overall impact of CTLs (κE between 0.1 and 0.3 day−1 at peak CTL levels) despite a similar killing rate constant.

There are several previous studies that have estimated the killing rate of virus-infected cells for HIV- or SIV-specific CD8+ T cells (4, 5, 15, 45, 52). While our estimates of the killing rate at peak CTL levels are very similar to other estimates of the killing rate made early during the acute infection phase (15, 45), they are much higher (∼5- to 100-fold) than those estimated from later in the infection (4, 52). This difference may to some extent reflect that Tat SL8 CTLs predominate during the acute infection phase and that the impairment of CD4+ T-cell help and damage resulting from chronic antigen stimulation have not yet taken their toll on CD8+ T-cell function (51). In addition, given the essential function of Tat early during the viral replication cycle and its expression prior to Nef-induced downregulation of MHC class I (13, 53), we hypothesized that Tat-specific CTLs are particularly effective at killing infected cells prior to their production of viral progeny. There is some experimental evidence to suggest this might be the case (35, 36). In part, the discrepancy between our estimates and those of others also may be due to the fact that the killing rates estimated do not incorporate specific CD8+ T-cell levels and hence that the killing rates represent mean selection pressures over the time period for which they were estimated. From our model, the mean killing rate is between 0.07 and 0.22 day−1 for control animals. Interestingly, our estimate is substantially (∼100-fold) lower than the killing constant that was estimated for specific CD8+ T cells in the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus murine model from the decline in adoptively transferred, peptide-pulsed target cells (46), and possible reasons for this are reviewed extensively elsewhere (47).

Estimates for the half-lives of virus-infected cells have been obtained from the chronic infection phase of both SIV infections of rhesus macaques and HIV infections of humans by quantifying the rate of decline of the viral load following HAART (26, 50). Most recent analyses suggest that the half-life is ∼0.5 days (9, 38). This number incorporates any effect that CTLs might have on infected cell death. Our estimate of the CTL killing rate during acute infection suggests that if infected cells were dying only as a result of killing by Tat-specific CD8+ T cells, in control animals at peak CTL numbers infected cells would have a half-life of 1.1 to 4.0 days. Given that there is at least one other dominant Mamu-A*01-restricted SIV-specific CD8+ T-cell response to another epitope (Gag CM9) and there are other, non-Mamu-A*01-restricted CTL responses, this means that with high enough specific CD8+ T-cell levels, CTLs can make a substantial contribution to the death of infected cells during the acute infection phase. This substantial impact is, however, likely to be short lived. As mentioned above, Asquith et al. showed that the killing rate of specific CD8+ T cells is significantly lower during chronic infection (4). This is plausible given the dysfunction of CD8+ T cells that can arise during chronic infections, especially in the absence of sufficient CD4+ T-cell help (51). Additional support for the compromised CD8+ T-cell control of HIV replication during the chronic infection phase, be it the result of CD8+ T-cell dysfunction or viral escape, comes from the observation that HIV-infected individuals with very different viral load set points have similar infected cell half-lives during chronic infection irrespective of their baseline CD4+ T-cell counts, and presumably they have variable levels of HIV-specific CTLs (14). This insight and recent studies showing the substantial loss of CD4+ T cells in mucosal tissue emphasizes that there are key distinctions to be made between primary and chronic infection in understanding the dynamics of CD4+ T cells (40, 49).

To look at the biological meaning of our killing rate estimates from a different perspective, that of the control of viral replication, the effectiveness of Tat-specific CTLs can be compared to the maximum efficacy of HAART in SIV-infected macaques, given that HAART is the best available example for modulating HIV or SIV replication in vivo. The maximum effectiveness of HAART in reducing viral replication was determined empirically by Brandin et al. from the rate of decrease in the viral load following treatment of SIVmac251-infected macaques to be 1.5 day−1 (9), which is similar to what has been estimated for humans (38). HAART causes the observed decline in virus load by preventing new rounds of infection. The decline thus reveals the ongoing death of infected cells. Conversely, the killing rate by Tat-specific CTLs, κE, of virus-infected cells, which we estimated to be as high as 0.9 day−1, is an estimate of the impact of CTLs on limiting viral replication. A comparison of the killing rate of Tat-specific CTLs to the effectiveness of HAART thus suggests that Tat-specific CD8+ T cells can have a considerable impact on suppressing virus replication, approximately half of what can be achieved with HAART. It should be pointed out that the comparisons of CTLs to HAART depend on the HAART effectiveness estimates used. Here, we have made the most stringent comparison and compared results for Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T cells to those for the most potent antiretroviral therapy used for primates (quadruple therapy using zidovudine, lamivudine, tenofovir, and lopinavir). Estimates of CTL efficacy will be somewhat higher than those for antiretroviral monotherapy.

HAART, when used correctly, can overcome the inherent propensity of the virus to escape from drug pressure through development of resistance mutations (enabled by high rates of virus replication and dependence on an error-prone reverse transcriptase). In a number of ways, the response to certain individual CD8+ T-cell responses, such as the Tat SL8 responses, can resemble the response to antiretrovirals of the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor class that have significant antiviral potency, which is promptly lost when they are used as monotherapy (25). Yet, just like different antiretroviral drugs, different CTL responses may target viral sequences that are less able to escape from prevailing selective pressures (due to a higher genetic barrier imposed by the need for multiple nucleotide alterations to change a sufficient number of codons to permit reduced susceptibility to the relevant selective pressure) and/or that exact a greater fitness cost. While the principles of successful HAART regimens are now well understood, it remains to be determined what it will take for antiviral CTLs to effectively and durably control virus replication. One essential variable for the principles of successful CTL control of virus replication is the actual in vivo potency of different antiviral CD8+ T-cell responses. To this end, the development of new quantitative methods to robustly estimate the in vivo effectiveness of CTLs and thereby gauge the relative potency of CD8+ T-cell responses will be crucial.

In an estimation of the killing rate of CTLs, it is important to determine the fitness cost of escape so that CTL killing is not underestimated. Viral variants are subject to a selection-versus-fitness balance that has important implications for the rational design of vaccines and for understanding how CD8+ T cells can shape viral evolution at the between-individual level. Previously, fitness costs for escape from CD8+ T-cell selection pressure have been inferred from the reduced viral replication escape mutants in vitro (17), the presence of compensatory mutations that enhance viral replication (44), and the relative propensity for reversion of escape mutants after transmission to MHC class I-disparate primates or humans (16, 31). Our model allows the quantification of the fitness cost of escape for a particular epitope directly from the increase in frequency of the virus mutant over time. We show that even for a small reduction in replication rate of the mutant relative to that of the wild-type virus, reversion will occur once the selective pressure exerted by specific CTLs declines. If the fitness cost of escape is large enough, then it can prohibit the outgrowth of escape mutants, at least until compensatory mutations are accumulated, as is the case for the Gag CM9 epitope, for which escape occurs late in infection despite the presence of similar levels of Gag CM9- and Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T cells during acute SIV infection (17, 19, 44). The results of our model fittings are consistent with experimental evidence that Tat SL8 escape mutations do not manifest a discernible replicative fitness cost. In particular, previous experimental infection studies have demonstrated the persistence of Tat SL8 mutations following experimental infection of Mamu-A*01-negative macaques with SIV harboring Tat SL8 mutations (16). However, both our data and the available experimental results may have been insufficiently sensitive to detect a very small fitness cost exacted by Tat SL8 escape mutations. Insufficient sensitivity to detect very-low-level fitness costs of escape could be the result of sample sizes employed being too small. Nevertheless, the Tat coding sequence and the Tat protein appear to readily tolerate the observed sequence mutations in the Tat SL8 epitope region without a meaningful resulting reduction in the in vivo replicative capacity of such viral variants. However, it is likely that the limited or absent fitness costs manifested by the Tat SL8 epitope variants that confer escape from SL8-specific CTLs are unusual and that most other mutations that arise in other viral regions in response to the selective pressure imposed by other epitope-specfic CTLs will be associated with various degrees of fitness impairment.

In summary, our results provide evidence that at least during acute infection, CD8+ T cells can have a significant impact on shortening the longevity of CD4+ T cells and are able to exert a substantial selective pressure on the replicating virus population. Indeed, with sufficiently high peak CTL levels emerging during the acute infection period, CTLs that are specific for single viral epitopes can, at least transiently, be up to half as effective as HAART in suppressing virus replication. Given the current predominance of HIV vaccine approaches predicated on the induction of antiviral CTLs (20), our data providing quantitative support for the potency of certain antiviral responses that emerge during primary infection is encouraging. However, the actual effectiveness of the Tat SL8 responses is abrogated by immune escape and appears to be significantly influenced by the availability of CD4+ T-cell help elicited during primary infection and maintained thereafter. As such, for CTL-based vaccines to accomplish durable control of virus replication and avoid the inherent propensity of HIV to escape from immune selective pressures, it is likely that, analogous to HAART, multiple viral gene products will need to be targeted by vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cells, including those that possess a significant genetic barrier to escape or that, in the event of escape via epitope mutation, exhibit substantial fitness impairment. Furthermore, following HIV infection, the durability of immune control of virus replication by CTLs induced by vaccination prior to infection is likely to be dependent upon the extent to which the prompt activation of memory CD8+ T cells during primary infection can favorably alter early infection dynamics and enable the preservation of CD4+ T-cell help required for significant and durable antiviral CD8+ T-cell responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Lee for determining the SIV viral loads, T. Vanderford and A. Hendel for technical advice, and R. Antia, B. Levin, G. Silvestri, S. Staprans, L. White, and A. Yates for invaluable discussions.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Institutes of Health grants AI49334 (R.R.) and AI049155.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addo, M. M., X. G. Yu, A. Rathod, D. Cohen, R. L. Eldridge, D. Strick, M. N. Johnston, C. Corcoran, A. G. Wurcel, C. A. Fitzpatrick, M. E. Feeney, W. R. Rodriguez, N. Basgoz, R. Draenert, D. R. Stone, C. Brander, P. J. Goulder, E. S. Rosenberg, M. Altfeld, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Comprehensive epitope analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell responses directed against the entire expressed HIV-1 genome demonstrate broadly directed responses, but no correlation to viral load. J. Virol. 77:2081-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, T. M., D. H. O'Connor, P. Jing, J. L. Dzuris, B. R. Mothe, T. U. Vogel, E. Dunphy, M. E. Liebl, C. Emerson, N. Wilson, K. J. Kunstman, X. Wang, D. B. Allison, A. L. Hughes, R. C. Desrosiers, J. D. Altman, S. M. Wolinsky, A. Sette, and D. I. Watkins. 2000. Tat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes select for SIV escape variants during resolution of primary viraemia. Nature 407:386-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen, T. M., J. Sidney, M. F. del Guercio, R. L. Glickman, G. L. Lensmeyer, D. A. Wiebe, R. DeMars, C. D. Pauza, R. P. Johnson, A. Sette, and D. I. Watkins. 1998. Characterization of the peptide binding motif of a rhesus MHC class I molecule (Mamu-A*01) that binds an immunodominant CTL epitope from simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Immunol. 160:6062-6071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asquith, B., C. T. Edwards, M. Lipsitch, and A. R. McLean. 2006. Inefficient cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated killing of HIV-1-infected cells in vivo. PLoS Biol. 4:e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asquith, B., and A. R. McLean. 2007. In vivo CD8+ T cell control of immunodeficiency virus infection in humans and macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:6365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betts, M. R., D. R. Ambrozak, D. C. Douek, S. Bonhoeffer, J. M. Brenchley, J. P. Casazza, R. A. Koup, and L. J. Picker. 2001. Analysis of total human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses: relationship to viral load in untreated HIV infection. J. Virol. 75:11983-11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonhoeffer, S., A. D. Barbour, and R. J. De Boer. 2002. Procedures for reliable estimation of viral fitness from time-series data. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269:1887-1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borrow, P., H. Lewicki, X. Wei, M. S. Horwitz, N. Peffer, H. Meyers, J. A. Nelson, J. E. Gairin, B. H. Hahn, M. B. Oldstone, and G. M. Shaw. 1997. Antiviral pressure exerted by HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) during primary infection demonstrated by rapid selection of CTL escape virus. Nat. Med. 3:205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandin, E., R. Thorstensson, S. Bonhoeffer, and J. Albert. 2006. Rapid viral decay in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques receiving quadruple antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 80:9861-9864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao, J., J. McNevin, U. Malhotra, and M. J. McElrath. 2003. Evolution of CD8+ T cell immunity and viral escape following acute HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 171:3837-3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Efron, B., and R. Tibshirani. 1986. Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Stat. Sci. 1:54-77. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feinberg, M. B. 2002. The interface between the pathogenesis and treatment of HIV infection. In E. A. Emini (ed.), The human immunodeficiency virus. Biology, immunology and therapy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- 13.Feinberg, M. B., D. Baltimore, and A. D. Frankel. 1991. The role of Tat in the human immunodeficiency virus life cycle indicates a primary effect on transcriptional elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:4045-4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feinberg, M. B., and A. R. McLean. 1997. AIDS: decline and fall of immune surveillance? Curr. Biol. 7:R136-R140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez, C. S., I. Stratov, R. De Rose, K. Walsh, C. J. Dale, M. Z. Smith, M. B. Agy, S. L. Hu, K. Krebs, D. I. Watkins, H. O'Connor, D. M. P. Davenport, and S. J. Kent. 2005. Rapid viral escape at an immunodominant simian-human immunodeficiency virus cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope exacts a dramatic fitness cost. J. Virol. 79:5721-5731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedrich, T. C., E. J. Dodds, L. J. Yant, L. Vojnov, R. Rudersdorf, C. Cullen, D. T. Evans, R. C. Desrosiers, B. R. Mothe, J. Sidney, A. Sette, K. Kunstman, S. Wolinsky, M. Piatak, J. Lifson, A. L. Hughes, N. Wilson, D. H. O'Connor, and D. I. Watkins. 2004. Reversion of CTL escape-variant immunodeficiency viruses in vivo. Nat. Med. 10:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedrich, T. C., C. A. Frye, L. J. Yant, D. H. O'Connor, N. A. Kriewaldt, M. Benson, L. Vojnov, E. J. Dodds, C. Cullen, R. Rudersdorf, A. L. Hughes, N. Wilson, and D. I. Watkins. 2004. Extraepitopic compensatory substitutions partially restore fitness to simian immunodeficiency virus variants that escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte response. J. Virol. 78:2581-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganusov, V. V., and R. J. De Boer. 2006. Estimating costs and benefits of CTL escape mutations in SIV/HIV infection. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2:e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garber, D. A., G. Silvestri, A. P. Barry, A. Fedanov, N. Kozyr, H. McClure, D. C. Montefiori, C. P. Larsen, J. D. Altman, S. I. Staprans, and M. B. Feinberg. 2004. Blockade of T cell costimulation reveals interrelated actions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in control of SIV replication. J. Clin. Investig. 113:836-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garber, D. A., G. Silvestri, and M. B. Feinberg. 2004. Prospects for an AIDS vaccine: three big questions, no easy answers. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4:397-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon, S. N., N. R. Klatt, S. E. Bosinger, J. M. Brenchley, J. M. Milush, J. C. Engram, R. M. Dunham, M. Paiardini, S. Klucking, A. Danesh, E. A. Strobert, C. Apetrei, I. V. Pandrea, D. Kelvin, D. C. Douek, S. I. Staprans, D. L. Sodora, and G. Silvestri. 2007. Severe depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells in AIDS-free simian immunodeficiency virus-infected sooty mangabeys. J. Immunol. 179:3026-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goulder, P. J., and D. I. Watkins. 2004. HIV and SIV CTL escape: implications for vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:630-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman, Z., M. Meier-Schellersheim, W. E. Paul, and L. J. Picker. 2006. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nat. Med. 12:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Havlir, D. V., S. Eastman, A. Gamst, and D. D. Richman. 1996. Nevirapine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus: kinetics of replication and estimated prevalence in untreated patients. J. Virol. 70:7894-7899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho, D. D., A. U. Neumann, A. S. Perelson, W. Chen, J. M. Leonard, and M. Markowitz. 1995. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature 373:123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ihaka, R., and R. Gentleman. 1996. R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5:299-314. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin, X., D. E. Bauer, S. E. Tuttleton, S. Lewin, A. Gettie, J. Blanchard, C. E. Irwin, J. T. Safrit, J. Mittler, L. Weinberger, L. G. Kostrikis, L. Zhang, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8+ T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Exp. Med. 189:991-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim, S. Y., R. Byrn, J. Groopman, and D. Baltimore. 1989. Temporal aspects of DNA and RNA synthesis during human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for differential gene expression. J. Virol. 63:3708-3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuroda, M. J., J. E. Schmitz, W. A. Charini, C. E. Nickerson, M. A. Lifton, C. I. Lord, M. A. Forman, and N. L. Letvin. 1999. Emergence of CTL coincides with clearance of virus during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J. Immunol. 162:5127-5133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leslie, A. J., K. J. Pfafferott, P. Chetty, R. Draenert, M. M. Addo, M. Feeney, Y. Tang, E. C. Holmes, T. Allen, J. G. Prado, M. Altfeld, C. Brander, C. Dixon, D. Ramduth, P. Jeena, S. A. Thomas, A. St. John, T. A. Roach, B. Kupfer, G. Luzzi, A. Edwards, G. Taylor, H. Lyall, G. Tudor-Williams, V. Novelli, J. Martinez-Picado, P. Kiepiela, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. HIV evolution: CTL escape mutation and reversion after transmission. Nat. Med. 10:282-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis, M. G., S. Bellah, K. McKinnon, J. Yalley-Ogunro, P. M. Zack, W. R. Elkins, R. C. Desrosiers, and G. A. Eddy. 1994. Titration and characterization of two rhesus-derived SIVmac challenge stocks. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:213-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, Q., L. Duan, J. D. Estes, Z. M. Ma, T. Rourke, Y. Wang, C. Reilly, J. Carlis, C. J. Miller, and A. T. Haase. 2005. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature 434:1148-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, Y., J. I. Mullins, and J. E. Mittler. 2006. Waiting times for the appearance of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte escape mutants in chronic HIV-1 infection. Virology 347:140-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loffredo, J. T., B. J. Burwitz, E. G. Rakasz, S. P. Spencer, J. J. Stephany, J. P. Giraldo Vela, S. R. Martin, J. Reed, S. M. Piaskowski, J. Furlott, K. L. Weisgrau, D. S. Rodrigues, T. Soma, G. Napoe, T. C. Friedrich, N. A. Wilson, E. G. Kallas, and D. I. Watkins. 2007. SIV-specific CD8+ T-cell antiviral efficacy is unrelated to epitope specificity and abrogated by viral escape. J. Virol. 81:2624-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loffredo, J. T., E. G. Rakasz, J. P. Giraldo, S. P. Spencer, K. K. Grafton, S. R. Martin, G. Napoe, L. J. Yant, N. A. Wilson, and D. I. Watkins. 2005. Tat28-35 SL8-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes are more effective than Gag181-189 CM9-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes at suppressing simian immunodeficiency virus replication in a functional in vitro assay. J. Virol. 79:14986-14991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansky, L. M., and H. M. Temin. 1995. Lower in vivo mutation rate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 than that predicted from the fidelity of purified reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 69:5087-5094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markowitz, M., M. Louie, A. Hurley, E. Sun, M. Di Mascio, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 2003. A novel antiviral intervention results in more accurate assessment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication dynamics and T-cell decay in vivo. J. Virol. 77:5037-5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masemola, A., T. Mashishi, G. Khoury, P. Mohube, P. Mokgotho, E. Vardas, M. Colvin, L. Zijenah, D. Katzenstein, R. Musonda, S. Allen, N. Kumwenda, T. Taha, G. Gray, J. McIntyre, S. A. Karim, H. W. Sheppard, and C. M. Gray. 2004. Hierarchical targeting of subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteins by CD8+ T cells: correlation with viral load. J. Virol. 78:3233-3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattapallil, J. J., D. C. Douek, B. Hill, Y. Nishimura, M. Martin, and M. Roederer. 2005. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature 434:1093-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McMichael, A. J., and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2001. Cellular immune responses to HIV. Nature 410:980-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Migueles, S. A., A. C. Laborico, W. L. Shupert, M. S. Sabbaghian, R. Rabin, C. W. Hallahan, D. Van Baarle, S. Kostense, F. Miedema, M. McLaughlin, L. Ehler, J. Metcalf, S. Liu, and M. Connors. 2002. HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat. Immunol. 3:1061-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nowak, M. A., R. M. May, and R. M. Anderson. 1990. The evolutionary dynamics of HIV-1 quasispecies and the development of immunodeficiency disease. AIDS 4:1095-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peyerl, F. W., D. H. Barouch, W. W. Yeh, H. S. Bazick, J. Kunstman, K. J. Kunstman, S. M. Wolinsky, and N. L. Letvin. 2003. Simian-human immunodeficiency virus escape from cytotoxic T-lymphocyte recognition at a structurally constrained epitope. J. Virol. 77:12572-12578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Regoes, R. R., R. Antia, D. A. Garber, G. Silvestri, M. B. Feinberg, and S. I. Staprans. 2004. Roles of target cells and virus-specific cellular immunity in primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 78:4866-4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regoes, R. R., D. L. Barber, R. Ahmed, and R. Antia. 2007. Estimation of the rate of killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:1599-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Regoes, R. R., A. Yates, and R. Antia. 2007. Mathematical models of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte killing. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:274-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veazey, R. S., and A. A. Lackner. 1998. The gastrointestinal tract and the pathogenesis of AIDS. AIDS 12(Suppl. A):S35-S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei, X., S. K. Ghosh, M. E. Taylor, V. A. Johnson, E. A. Emini, P. Deutsch, J. D. Lifson, S. Bonhoeffer, M. A. Nowak, B. H. Hahn, et al. 1995. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature 373:117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wherry, E. J., J. N. Blattman, K. Murali-Krishna, R. van der Most, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J. Virol. 77:4911-4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wick, W. D., O. O. Yang, L. Corey, and S. G. Self. 2005. How many human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected target cells can a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte kill? J. Virol. 79:13579-13586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams, M., J. F. Roeth, M. R. Kasper, R. I. Fleis, C. G. Przybycin, and K. L. Collins. 2002. Direct binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef to the major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) cytoplasmic tail disrupts MHC-I trafficking. J. Virol. 76:12173-12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, Z. Q., S. W. Wietgrefe, Q. Li, M. D. Shore, L. Duan, C. Reilly, J. D. Lifson, and A. T. Haase. 2004. Roles of substrate availability and infection of resting and activated CD4+ T cells in transmission and acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:5640-5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]