Abstract

DDX3, a DEAD-box RNA helicase, binds to the hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein. However, the role(s) of DDX3 in HCV replication is still not understood. Here we demonstrate that the accumulation of both genome-length HCV RNA (HCV-O, genotype 1b) and its replicon RNA were significantly suppressed in HuH-7-derived cells expressing short hairpin RNA targeted to DDX3 by lentivirus vector transduction. As well, RNA replication of JFH1 (genotype 2a) and release of the core into the culture supernatants were suppressed in DDX3 knockdown cells after inoculation of the cell culture-generated HCVcc. Thus, DDX3 is required for HCV RNA replication.

DEAD-box RNA helicases are involved in various RNA metabolic processes, including transcription, translation, RNA splicing, RNA transport, and RNA degradation (9, 20). DDX1 and DDX3, DEAD-box RNA helicases, have been implicated in the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Both DDX1 and DDX3 interact with HIV-1 Rev and enhance Rev-dependent HIV-1 RNA nuclear export (10, 24).

On the other hand, DDX3 binds to the hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein (17, 19, 25), and DDX3 expression is deregulated in HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (7, 8). However, the biological function of DDX3 in HCV replication is still not understood. To address this issue, we first used lentivirus vector-mediated RNA interference to stably knock down DDX3 in three HuH-7-derived cell lines: O cells, harboring a replicative genome-length HCV RNA (HCV-O, genotype 1b) (13); sO cells, harboring its subgenomic replicon of HCV RNA (14); or RSc cured cells, which cell culture-generated HCV (HCVcc) (JFH1, genotype 2a) (23) could infect and effectively replicate in (M. Ikeda et al., unpublished data). Oligonucleotides with the following sense and antisense sequences were used for the cloning of short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-encoding sequences against DDX3 in the lentivirus vector: for DDX3i#3, 5′-GATCCCCGGAGGAAATTATAACTCCCTTCAAGAGAGGGAGTTATAATTTCCTCCTTTTTGGAAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAGGAGGAAATTATAACTCCCTCTCTTGAAGGGAGTTATAATTTCCTCCGGG-3′ (antisense); for DDX3i#7, 5′-GATCCCCGGTCACCCTGCCAAACAAGTTCAAGAGACTTGTTTGGCAGGGTGACCTTTTTGGAAA-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAGGTCACCCTGCCAAACAAGTCTCTTGAACTTGTTTGGCAGGGTGACCGGG-3′ (antisense). These oligonucleotides were annealed and subcloned into the BglII-HindIII site, downstream from an RNA polymerase III promoter of pSUPER (6). To construct pLV-DDX3i#3 and pLV-DDX3i#7, the BamHI-SalI fragments of the corresponding pSUPER plasmids were subcloned into the BamHI-SalI site of pRDI292 (5), an HIV-1-derived self-inactivating lentivirus vector containing a puromycin resistance marker allowing for the selection of transduced cells. The vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped HIV-1-based vector system has been described previously (18). We used the second-generation packaging construct pCMV-ΔR8.91 (26) and the VSV-G-envelope plasmid pMDG2. The lentivirus vector particles were produced by transient transfection of 293FT cells with FuGene 6 (Roche).

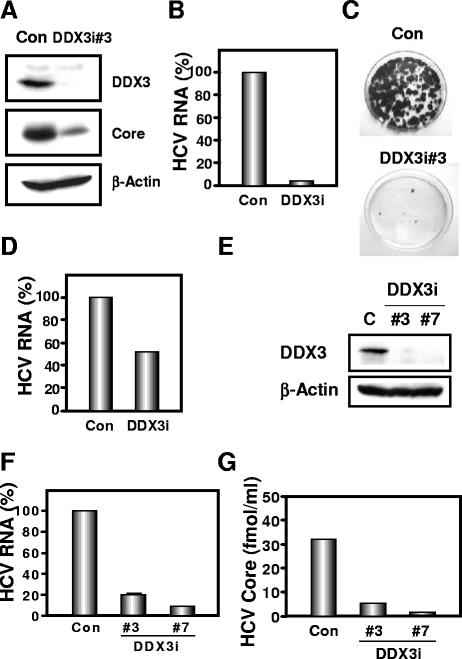

Western blot analysis of the lysates demonstrated the only trace of DDX3 protein in DDX3 knockdown O cells (DDX3i#3) (Fig. 1A). In this context, the HCV core expression level was significantly decreased in the DDX3 knockdown O cells (Fig. 1A). To further confirm this finding, we examined the level of HCV RNA in these cells. We found that accumulation of genome-length HCV-O RNA was notably suppressed in DDX3 knockdown O cells (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the efficiency of colony formation in DDX3 knockdown Oc cells (created by eliminating genome-length HCV RNA from O cells by interferon treatment) transfected with the genome-length HCV-O RNA with an adapted mutation at amino acid (aa) position 1609 in the NS3 helicase region (K1609E) (13) was also notably reduced compared with that in control cells (Fig. 1C). In contrast, highly efficient knockdown of an unrelated host factor, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) (4), had no observable effects on HCV RNA replication, the efficiency of colony formation, or the core expression level (data not shown), suggesting that our finding was not due to a nonspecific event. Interestingly, accumulation of the subgenomic replicon RNA (HCV-sO) was also suppressed in DDX3 knockdown sO cells (Fig. 1D). Moreover, we examined the potential role of DDX3 in an HCV infection and production system (23). We found 80 to 90% reductions in the accumulation of JFH1 RNA and 82 to 94% reductions in the release of the core into the culture supernatants in DDX3 knockdown HuH-7-derived RSc cured cells at 4 days after inoculation of HCVcc (Fig. 1E to G). Thus, DDX3 seems to be required for HCV RNA replication.

FIG. 1.

Requirement of DDX3 for HCV replication. (A to D) Effect of DDX3 knockdown on HCV RNA replication. (A) Inhibition of DDX3 expression by shRNA-producing lentivirus vector. The results of Western blot analysis of cellular lysates with anti-DDX3 (ProSci), anti-HCV core (CP-9; Institute of Immunology), or an anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma) in O cells expressing shRNA against DDX3 (DDX3i#3) as well as in O cells transduced with a control lentivirus vector (Con) are shown. (B) The level of genome-length HCV RNA was monitored by real-time LightCycler PCR (Roche). Experiments were done in duplicate, and bars represent the mean percentages of HCV RNA. (C) Efficiency of colony formation in DDX3 knockdown cells. In vitro-transcribed ON/C-5B K1609E RNA (2 μg) was transfected into the DDX3 knockdown Oc cells (DDX3i#3) or the Oc cells transduced with a control lentivirus vector (Con). G418-resistant colonies were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue at 3 weeks after electroporation of RNA. Experiments were done in duplicate, and representative results are shown. (D) The level of subgenomic replicon RNA was monitored by real-time LightCycler PCR. Experiments were done in duplicate, and bars represent the mean percentages of HCV RNA. (E to G) Effect of DDX3 knockdown on HCV infection. (E) Inhibition of DDX3 expression by shRNA-producing lentivirus vector. The results of Western blot analysis of cellular lysates with anti-DDX3 or an anti-β-actin antibody for RSc cells expressing the shRNA DDX3i#3 or DDX3i#7 and for RSc cells transduced with a control lentivirus vector (Con) are shown. (F) The level of genome-length HCV (JFH1) RNA was monitored by real-time LightCycler PCR after inoculation of the cell culture-generated HCVcc. Results from three independent experiments are shown. (G) The levels of the HCV core in the culture supernatants were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Mitsubishi Kagaku Bio-Clinical Laboratories). Experiments were done in duplicate, and bars represent the mean HCV core protein levels.

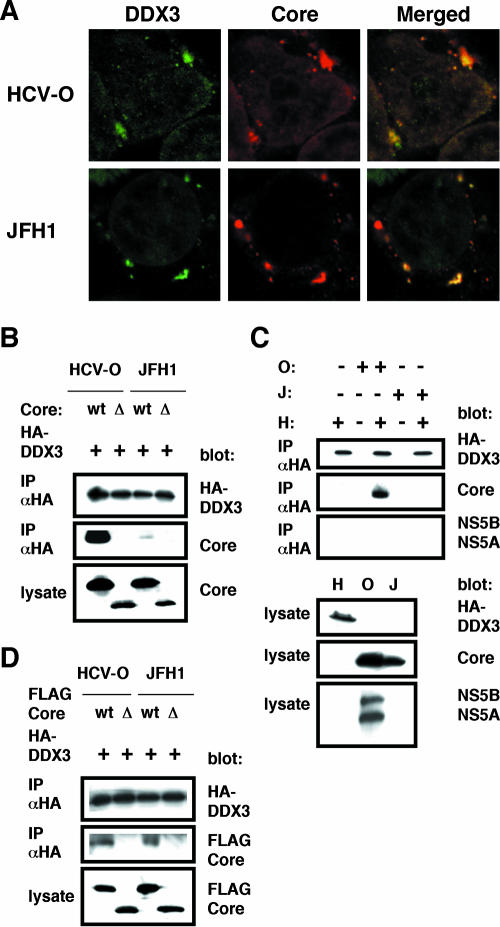

Previously, DDX3 was identified as an HCV core-interacting protein by yeast two-hybrid screening. This interaction required the N-terminal domain of the core (aa 1 to 59) and the C-terminal domain of DDX3 (aa 553 to 622) (17, 19, 25). To determine whether the core can interact with DDX3 regardless of the HCV genotype, we used the HCV-O core (genotype 1b) and the JFH1 core (genotype 2a) (Table 1). We first examined their subcellular localization by confocal laser scanning microscopy as previously described (3). Consistent with previous reports (17, 19, 25), both the HCV-O core and JFH1 core mostly colocalized with DDX3 in the perinuclear region (Fig. 2A). Then we immunoprecipitated lysates from 293FT cells in which hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged DDX3 and HCV-O core, JFH1 core, or their 40-aa N-truncated mutants were overexpressed with an anti-HA antibody. Cells were lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 10 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Lysates were precleared with 30 μl of protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). Precleared supernatants were incubated with 1 μg of anti-HA antibody (3F10; Roche) at 4°C for 1 h. Following absorption of the precipitates on 30 μl of protein G-Sepharose resin for 1 h, the resin was washed four times with 700 μl lysis buffer. Proteins were eluted by boiling the resin for 5 min in 1× Laemmli sample buffer. The proteins were then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by immunoblot analysis using either anti-HA (HA-7; Sigma) or anti-HCV core antibody (CP-9 and CP-11 mixture). We observed that the HCV-O core but not its N-truncated mutant could strongly bind to HA-tagged DDX3 (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the binding activity of the JFH1 core to HA-tagged DDX3 seemed to be fairly weak (Fig. 2B). As well, immunoprecipitation of lysates of 293FT cells expressing HA-tagged DDX3, O cells, or JFH1-infected RSc cells, or mixtures of these lysates, with an anti-HA antibody revealed that HCV-O core but not JFH1 core could bind strongly to DDX3 (Fig. 2C). The anti-HCV core antibody we used could detect both HCV-O core and JFH1 core (Fig. 2), while both anti-HCV NS5A and anti-NS5B antibodies failed to detect JFH1 NS5A and NS5B (Fig. 2C). At least, we failed to detect an interaction between DDX3 and either HCV-O NS5A or NS5B under experimental conditions that permitted the core to interact with DDX3 by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the FLAG-tagged JFH1 core could bind to HA-tagged DDX3 just as efficiently as the FLAG-tagged HCV-O core could (Fig. 2D). Thus, the binding affinity or stability of the complex formed between the JFH1 core and DDX3 might be weaker than that between the HCV-O core and DDX3.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for construction of the HCV core-expressing plasmidsa

| Plasmid name | Direction | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| pCXbsr/core(HCV-O) | Forward | 5′-GGAATTCCCACCATGAGCACGAATCCTAAACCTC-3 |

| Reverse | 5′-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCCTATCAAGCGGAAGCTGGGATGGT-3′ | |

| pcDNA3/core(HCV-O) | Forward | 5′-CGGGATCCAAGATGAGCACGAATCCTAAACCTCAAAGA-3′ |

| pcDNA3/FLAG-core(HCV-O) | Reverse | 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCAAGCGGAAGCTGGGATGGTCAAACA-3′ |

| pcDNA3/Δcore(HCV-O) | Forward | 5′-CGGGATCCAAGATGGGCCCCAGGTTGGGTGTGCGC-3′ |

| pcDNA3/FLAG-Δcore(HCV-O) | Reverse | 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCAAGCGGAAGCTGGGATGGTCAAACA-3′ |

| pcDNA3/core(JFH1) | Forward | 5′-CGGGATCCAAGATGAGCACAAATCCTAAACCTCAAAGA-3′ |

| pcDNA3/FLAG-core(JFH1) | Reverse | 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCAAGCAGAGACCGGAACGGTGATGCA-3′ |

| pcDNA3/Δcore(JFH1) | Forward | 5′-CGGGATCCAAGATGGGCCCCAGGTTGGGTGTGCGC-3′ |

| pcDNA3/FLAG-Δcore(JFH1) | Reverse | 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCAAGCAGAGACCGGAACGGTGATGCA-3′ |

To construct pCXbsr/core(HCV-O), a DNA fragment encoding the core was amplified by PCR from pON/C-5B (13) with the indicated primers. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI-NotI and subcloned into the same site of pCX4bsr (1). To construct pcDNA3/core(HCV-O), pcDNA3/FLAG-core(HCV-O), pcDNA3/Δcore(HCV-O), and pcDNA3/FLAG-Δcore(HCV-O), DNA fragments encoding the core were amplified by PCR from pON/C-5B (13) with the indicated primer sets. To construct pcDNA3/core(JFH1), pcDNA3/FLAG-core(JFH1), pcDNA3/Δcore(JFH1), and pcDNA3/FLAG-Δcore(JFH1), DNA fragments encoding the core were amplified by PCR from pJFH1 (23) with the indicated primer sets. The PCR products were digested with BamHI and XhoI and then subcloned into the same site of pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) or pcDNA3-FLAG (2).

FIG. 2.

Interaction of the HCV core with DDX3. (A) The HCV core colocalizes with DDX3. 293FT cells cotransfected with 100 ng of pCXbsr/core(HCV-O) or pcDNA3/core(JFH1) and 200 ng of pHA-DDX3 were examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Cells were stained with anti-HCV core (CP-9 and CP-11 mixture) and anti-DDX3 antibodies and were then visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate (DDX3) or Cy3 (core). Images were visualized using confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM510; Carl Zeiss). The right panels exhibit the two-color overlay images (Merged). Colocalization is shown in yellow. (B) The core binds to DDX3. 293FT cells were cotransfected with 4 μg of pHA-DDX3 and 4 μg of pCXbsr/core(HCV-O) (wt), pcDNA3/Δcore(HCV-O) (Δ), pcDNA3/core(JFH1) (wt), or pcDNA3/Δcore(JFH1) (Δ). The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody (3F10; Roche), followed by immunoblot analysis using either anti-HA (HA-7; Sigma) or anti-HCV core antibody (CP-9 and CP-11 mixture). (C) 293FT cells transfected with 4 μg of pHA-DDX3 (H), O cells (O), or RSc cells 3 days after inoculation of HCVcc (JFH1) (J) were lysed and immunoprecipitated (IP) with 1 μg of anti-HA antibody (3F10), followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (HA-7), anti-core (CP-9 and CP-11 mixture), or anti-HCV NS5A (no. 8926) and anti-HCV NS5B. (D) 293FT cells transfected with 4 μg of pHA-DDX3 and 4 μg of pcDNA3/FLAG-core(HCV-O) (wt), pcDNA3/FLAG-Δcore(HCV-O) (Δ), pcDNA3/FLAG-core(JFH1) (wt), or pcDNA3/FLAG-Δcore(JFH1) (Δ) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of an anti-HA antibody (3F10), followed by immunoblotting with an anti-HA (HA-7) or anti-core (CP-9 and CP-11 mixture) antibody.

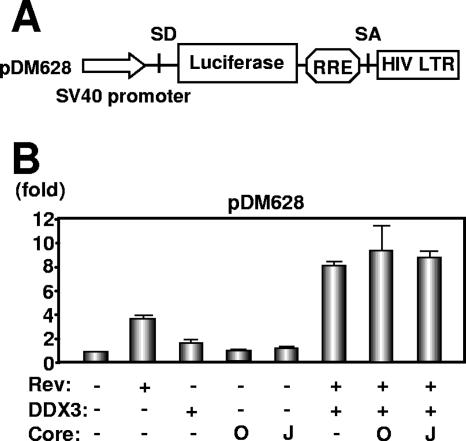

Since DDX3 is required for HIV-1 and HCV replication, we hypothesized that the HCV core might affect the function of HIV-1 Rev when both proteins were coexpressed. To test this hypothesis, we used the Rev-dependent luciferase-based reporter plasmid pDM628, harboring a single intron that includes both the Rev-responsive element (RRE) and the luciferase coding sequences (Fig. 3A) (10). In this system, Rev binds to RRE on the unspliced reporter mRNA, allowing its export from the nucleus for luciferase reporter gene expression, while the intron containing the luciferase gene is excised during RNA splicing when cells are transiently transfected with pDM628 alone. As previously reported (10), the luciferase activity in 293FT cells transfected with this reporter plasmid was stimulated by Rev, which induced a fourfold increase in the reporter signal (Fig. 3B). Luciferase activity was increased eightfold by the combination of Rev and DDX3, whereas neither the HCV-O core nor the JFH1 core had any effect on this Rev function (Fig. 3B). Since the Rev-binding domain (the N-terminal domain) and the core-binding domain (the C-terminal domain) do not overlap in DDX3, the HCV core might not compete with HIV-1 Rev for binding with DDX3. However, the development of a novel DDX3 inhibitor might provide a powerful antiviral agent against both HIV-1 and HCV (15).

FIG. 3.

HCV core does not affect the DDX3-mediated synergistic activation of Rev function. (A) Schematic representation of HIV-1 Rev-dependent luciferase-based reporter plasmid pDM628 harboring a splicing donor (SD), splicing acceptor (SA), and RRE. (B) 293FT cells were cotransfected with 100 ng of pDM628, 200 ng of pcRev, 200 ng of pHA-DDX3, and/or 100 ng of either pcDNA3/core(HCV-O) (O) or pcDNA3/core(JFH1) (J). A luciferase assay was performed 24 h later. All transfections utilized equal total amounts of plasmid DNA owing to the addition of the empty vector pcDNA3 to the transfection mixture. The relative stimulation of luciferase activity (n-fold) is shown. The results shown are means from three independent experiments.

Taking these results together, this study has shown for the first time that DDX3 is required for HCV RNA replication. Since helicases are motor enzymes that use energy derived from nucleoside triphosphate hydrolysis to unwind double-stranded nucleic acids, the DDX3-core complex might unwind the HCV double-stranded RNA and separate the RNA strands or might contribute to the function of HCV NS3 helicase. Since the replication of subgenomic replicon RNA was also partially suppressed in DDX3 knockdown cells (Fig. 1D), DDX3 might be associated with an HCV nonstructural protein(s) or HCV RNA itself. Indeed, Tingting et al. recently reported that DDX1 bound to both the HCV 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) and the HCV 5′ UTR and that short interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of DDX1 caused a marked reduction in the replication of subgenomic replicon RNA (22). Furthermore, Goh et al. demonstrated that DDX5/p68 associated with HCV NS5B and that depletion of endogenous DDX5 correlated with a reduction in the transcription of negative-strand HCV RNA (11). However, we failed to observe an interaction between DDX3 and NS5A or NS5B by immunoprecipitation under our experimental conditions in which the core could interact with DDX3 (Fig. 2C). Importantly, our DDX3 knockdown study demonstrated a more significant reduction in the accumulation of genome-length HCV RNA (95% reduction) than in the accumulation of subgenomic replicon RNA (52% reduction) (Fig. 1B and D). To date, it has been demonstrated that the 5′ UTR, the 3′ UTR, and the NS3-to-NS5B coding region are sufficient for HCV RNA replication (16); however, the core might be partly involved in the replication of genome-length HCV RNA. Importantly, DDX1 and DDX3 were specifically detected in the lipid droplets of core-expressing Hep39 cells by proteomic analysis (21), suggesting that DDX3 might be associated with HCV assembly or might incorporate into the HCV virion through interaction with the core to act as an RNA chaperone.

Recent studies have suggested a potential role of DDX3 and DDX5 in the pathogenesis of HCV-related liver diseases. DDX3 expression is deregulated in HCV-associated HCC (7, 8), and Huang et al. identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the DDX5 gene that were significantly associated with an increased risk of advanced fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C (12). Interestingly, DDX3 might be a candidate tumor suppressor. DDX3 inhibits colony formation in various cell lines, including HuH-7, and up-regulates the p21waf1/cip1 promoter (8). If DDX3 could in fact suppress tumor growth, then the core might overcome DDX3-mediated cell growth arrest and down-regulate p21waf1/cip1 through interaction with DDX3, and it might also be involved in HCC development.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Trono, K.-T. Jeang, V. Yedavalli, R. J. Pomerantz, J. Fang, R. Iggo, M. Hijikata, T. Akagi, and M. Kohara for pCMVΔR8.91, pMDG2, pHA-DDX3, pDM628, pcRev, pSUPER, pRDI292, 293FT cells, pCX4bsr, and the anti-NS5B antibody. We also thank A. Morishita and T. Nakamura for technical assistance.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), by a Grant-in-Aid for Research on Hepatitis from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan, by the Naito Foundation, by the Ichiro Kanehara foundation, and by a research fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akagi, T., T. Shishido, K. Murata, and H. Hanafusa. 2000. v-Crk activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway in transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7290-7295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariumi, Y., A. Kaida, M. Hatanaka, and K. Shimotohno. 2001. Functional cross-talk of HIV-1 Tat with p53 through its C-terminal domain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 287:556-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariumi, Y., T. Ego, A. Kaida, M. Matsumoto, P. P. Pandolfi, and K. Shimotohno. 2003. Distinct nuclear body components, PML and SMRT, regulate the trans-acting function of HTLV-1 Tax oncoprotein. Oncogene 22:1611-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ariumi, Y., P. Turelli, M. Masutani, and D. Trono. 2005. DNA damage sensors ATM, ATR, DNA-PKcs, and PARP-1 are dispensable for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integration. J. Virol. 79:2973-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridge, A. J., S. Pebernard, A. Ducraux, A.-L. Nicoulaz, and R. Iggo. 2003. Induction of an interferon response by RNAi vectors in mammalian cells. Nat. Genet. 34:263-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brummelkamp, T. R., R. Bernard, and R. Agami. 2002. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science 296:550-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, P. C., C. W. Chi, G. Y. Chau, F. Y. Li, Y. H. Tsai, J. C. Wu, and Y. H. Lee. 2006. DDX3, a DEAD box RNA helicase, is deregulated in hepatitis virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma and is involved in cell growth control. Oncogene 25:1991-2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao, C. H., C. M. Chen, P. L. Cheng, J. W. Shih, A. P. Tsou, and Y. H. Lee. 2006. DDX3, a DEAD box RNA helicase with tumor growth-suppressive property and transcriptional regulation activity of the p21waf1/cip1 promoter, is a candidate tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 66:6579-6588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordin, O., J. Banroques, N. K. Tanner, and P. Linder. 2006. The DEAD-box protein family of RNA helicases. Gene 367:17-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang, J., S. Kubota, B. Yang, N. Zhou, H. Zang, R. Godbout, and R. J. Pomerantz. 2004. A DEAD box protein facilitates HIV-1 replication as a cellular co-factor of Rev. Virology 330:471-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh, P. Y., Y. J. Tan, S. P. Lim, Y. H. Tan, S. G. Lim, F. Fuller-Pace, and W. Hong. 2004. Cellular RNA helicase p68 relocalization and interaction with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5B protein and the potential role of p68 in HCV RNA replication. J. Virol. 78:5288-5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang, H., M. L. Shiffman, R. C. Cheung, T. J. Layden, S. Friedman, O. T. Abar, L. Yee, A. P. Chokkalingam, S. J. Schrodi, J. Chan, J. J. Catanese, D. U. Leong, D. Ross, X. Hu, A. Monto, L. B. McAllister, S. Broder, T. White, J. J. Sninsky, and T. L. Wright. 2006. Identification of two gene variants associated with risk of advanced fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 130:1679-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda, M., K. Abe, H. Dansako, T. Nakamura, K. Naka, and N. Kato. 2005. Efficient replication of a full-length hepatitis C virus genome, strain O, in cell culture, and development of a luciferase reporter system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 329:1350-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato, N., K. Sugiyama, K. Namba, H. Dansako, T. Nakamura, M. Takami, K. Naka, A. Nozaki, and K. Shimotohno. 2003. Establishment of a hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon derived from human hepatocytes infected in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 306:756-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwong, A. D., B. G. Rao, and K. T. Jeang. 2005. Viral and cellular RNA helicases as antiviral targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4:845-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohmann, V., F. Körner, J.-O. Koch, U. Herian, L. Theilman, and R. Bartenschlager. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285:110-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mamiya, N., and H. J. Worman. 1999. Hepatitis C virus core protein binds to a DEAD box RNA helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15751-15756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naldini, L., U. Blömer, P. Gallay, D. Ory, R. Mulligan, F. H. Gage, I. M. Verma, and D. Trono. 1996. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of non-dividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 272:263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owsianka, A. M., and A. H. Patel. 1999. Hepatitis C virus core protein interacts with a human DEAD box protein DDX3. Virology 257:330-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocak, S., and P. Linder. 2004. DEAD-box proteins: the driving forces behind RNA metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:232-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato, S., M. Fukasawa, Y. Yamakawa, T. Natsume, T. Suzuki, I. Shoji, H. Aizaki, T. Miyamura, and M. Nishijima. 2006. Proteomic profiling of lipid droplet proteins in hepatoma cell lines expressing hepatitis C virus core protein. J. Biochem. 139:921-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tingting, P., F. Caiyun, Y. Zhigang, Y. Pengyuan, and Y. Zhenghong. 2006. Subproteomic analysis of the cellular proteins associated with the 3′ untranslated region of the hepatitis C virus genome in human liver cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347:683-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakita, T., T. Pietschmann, T. Kato, T. Date, M. Miyamoto, Z. Zhao, K. Murthy, A. Habermann, H. G. Kräusslich, M. Mizokami, R. Bartenschlager, and T. J. Liang. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11:791-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yedavalli, V. S., C. Neuveut, Y. H. Chi, L. Kleiman, and K. T. Jeang. 2004. Requirement of DDX3 DEAD box RNA helicase for HIV-1 Rev-RRE export function. Cell 119:381-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You, L. R., C. M. Chen, T. S. Yeh, T. Y. Tsai, R. T. Mai, C. H. Lin, and Y. H. Lee. 1999. Hepatitis C virus core protein interacts with cellular putative RNA helicase. J. Virol. 73:2841-2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zufferey, R., D. Nagy, R. J. Mandel, L. Naldini, and D. Trono. 1997. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 15:871-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]