Abstract

The cupA gene cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes components and assembly factors of a putative fimbrial structure that enable this opportunistic pathogen to form biofilms on abiotic surfaces. In P. aeruginosa the control of cupA gene expression is complex, with the H-NS-like MvaT protein functioning to repress phase-variable (on/off) expression of the operon. Here we identify four positive regulators of cupA gene expression, including three unusual regulators encoded by the cgrABC genes and Anr, a global regulator of anaerobic gene expression. We show that the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner under anaerobic conditions and that the cgr genes are essential for this expression. We show further that cgr gene expression is negatively controlled by MvaT and positively controlled by Anr and anaerobiosis. Expression of the cupA genes therefore appears to involve a regulatory cascade in which anaerobiosis, signaled through Anr, stimulates expression of the cgr genes, resulting in a concomitant increase in cupA gene expression. Our findings thus provide mechanistic insight into the regulation of cupA gene expression and identify anaerobiosis as an inducer of phase-variable cupA gene expression, raising the possibility that phase-variable expression of fimbrial genes important for biofilm formation may occur in P. aeruginosa persisting in the largely anaerobic environment of the cystic fibrosis host lung.

The gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen of humans that is notorious for being the principal cause of morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients; chronic colonization of the CF lung by P. aeruginosa typically leads to progressive lung damage and eventually respiratory failure and death (13). In the CF lung the organism is thought to persist as a biofilm, forming clusters of cells encased in a polymeric matrix (32). In this biofilm mode of growth P. aeruginosa exhibits increased resistance to antibiotics and is better able to evade the host immune response (6). Recent evidence suggests that the microbial environment in the CF lung is largely anaerobic (43) and that cells of P. aeruginosa persist in the CF lung in anaerobic biofilms (47). Indeed, the biofilm formed by cells of P. aeruginosa under anaerobic conditions is especially robust (47).

The cupA gene cluster of P. aeruginosa encodes components of a putative fimbrial structure that enables this organism to form biofilms on abiotic surfaces (36). Under standard laboratory growth conditions, expression of the cupA gene cluster is tightly repressed by MvaT (37), a putative transcription regulator that is thought to functionally resemble members of the H-NS family of nucleoid-associated proteins (34). MvaT from P. aeruginosa was originally identified as a global regulator of virulence gene expression (7), and recent microarray analyses have revealed that MvaT controls the expression of at least 150 or so genes in P. aeruginosa, with the cupA genes being the most tightly repressed (37). Several of the genes within the MvaT regulon are implicated in virulence, and a preponderance of MvaT-controlled genes encode components of putative adhesive structures or surface proteins such as fimbriae (37).

Recent findings indicate that the control of cupA gene expression in P. aeruginosa is complex. In particular, we have found that in the absence of MvaT, expression of the cupA fimbrial gene cluster is phase variable (i.e., the gene cluster exhibits reversible on/off expression) (38). The diversity in the bacterial population that results from phase-variable expression of the cupA fimbrial genes might impart a fitness advantage. Although we previously observed phase-variable expression of the cupA genes in an mvaT mutant background, we did not know whether phase-variable expression of the cupA genes could occur in wild-type cells.

Here we present evidence that the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner when wild-type cells of P. aeruginosa are grown under anaerobic conditions. Moreover, we identified components of the regulatory network that positively regulates cupA gene expression under these conditions. In particular, using a genetic screen, we identified four positive regulators of cupA gene expression. These include Anr, a global regulator of anaerobic gene expression, and three regulators whose effects on gene expression are localized primarily to the cupA genes. The three local regulators are encoded by the cgrABC genes that reside in a putative operon situated immediately upstream of the cupA gene cluster. The products of the cgr genes do not resemble any classical positive regulator of gene expression; cgrA encodes a hypothetical protein of unknown function, whereas cgrB encodes a putative acetylase and cgrC encodes a protein with homology to the ParB family of DNA-binding proteins that are typically involved in DNA segregation. We show that all three of the cgr genes are required for phase-variable expression of the cupA genes, either in the context of an mvaT mutant background or when wild-type cells are grown anaerobically. We show further that cgr gene expression is subject to control by MvaT, Anr, and anaerobiosis. Our finding that anaerobiosis induces phase-variable cupA gene expression raises the possibility that phase-variable expression of fimbrial genes important for biofilm formation may occur in P. aeruginosa persisting in the CF host lung, where the microbial environment is thought to be largely anaerobic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

All P. aeruginosa strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli DH5αF′IQ (Invitrogen) was used as the recipient strain for all plasmid constructs, and E. coli strain SM10 was used to mate plasmids into P. aeruginosa. P. aeruginosa was grown in LB for all experiments except those whose results are shown in Fig. 5; in the latter experiments LB with 2.5 g/liter NaCl and 1% KNO3 (LBN) was used as the growth medium. When E. coli was grown, antibiotics were used when necessary at the following concentrations: gentamicin, 15 μg/ml; carbenicillin, 100 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 5 μg/ml. When P. aeruginosa was grown, antibiotics were used when necessary at the following concentrations: gentamicin, 25 μg/ml for liquid cultures and 60 μg/ml for solid media; carbenicillin, 300 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 200 μg/ml. Phase-on and phase-off colonies were visualized following growth on LB agar or LBN agar containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (75 μg/ml). Anaerobic growth conditions were achieved using an anaerobic growth chamber together with a gas pack (AnaeroPack system; PML Microbiologicals). To confirm that anaerobic conditions were attained, in each experiment a Δanr strain (PAO1 Δanr cupA lacZ; see below) was incubated alongside the experimental strain(s). As reported previously, anr mutants do not grow under anaerobic conditions in which nitrate is used as the terminal electron acceptor (46, 48).

TABLE 1.

P. aeruginosa strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | Arne Rietsch (Case Western Reserve University) |

| PAO1 cupA lacZ | PAO1 containing chromosomal cupA1 lacZ reporter | 38 |

| PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ | PAO1 cupA lacZ containing deletion of mvaT | 38 |

| PAO1 ΔPA2127 cupA lacZ | PAO1 cupA lacZ containing deletion of PA2127 gene | This study |

| PAO1 ΔPA2126 cupA lacZ | PAO1 cupA lacZ containing deletion of PA2126 gene | This study |

| PAO1 ΔmvaT ΔPA2127 cupA lacZ | PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ containing deletion of PA2127 gene | This study |

| PAO1 ΔmvaT ΔPA2126 cupA lacZ | PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ containing deletion of PA2126 gene | This study |

| PAO1 ΔmvaT PA2127 cupA lacZ | PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ containing partial deletion of PA2127 gene | This study |

| PAO1 ΔmvaT PA2126.1 cupA lacZ | PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ containing partial deletion of PA2126.1 gene | This study |

| PAO1 ΔmvaT PA2126 cupA lacZ | PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ containing partial deletion of PA2126 gene | This study |

| PAO1 PA2126 lacZ | PAO1 containing chromosomal PA2126 gene-lacZ reporter | This study |

| PAO1 ΔmvaT PA2126 lacZ | PAO1 PA2126 lacZ containing deletion of mvaT | This study |

| PAO1 attB::pPA2127-lacZ | PAO1 containing chromosomal pPA2127-lacZ reporter integrated at φCTX attachment site | This study |

| PAO1 ΔmvaT attB::pPA2127-lacZ | PAO1 attB::pPA2127-lacZ containing deletion of mvaT | This study |

| PAO1 Δanr cupA lacZ | PAO1 cupA lacZ containing deletion of anr | This study |

| PAO1 Δanr ΔmvaT cupA lacZ | PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ containing deletion of anr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pPSV35 | Shuttle vector with gentamicin resistance gene (aacC1), PA origin, lacIq, and lacUV5 promoter | 24 |

| pPSV35-1 | pPSV35 with genomic DNA fragment from P. aeruginosa strain PAK containing part of PA2125 gene through part of PA2129 gene | This study |

| pPSV35-2 | Derivative of pPSV35-1 containing part of PA2127 gene-cupA1 intergenic region through part of PA2129 gene | This study |

| pPSV35-3 | Derivative of pPSV35-1 containing part of PA2125 gene through part of PA2127 gene-cupA1 intergenic region | This study |

| pPSV35-4 | pPSV35 with genomic DNA fragment from P. aeruginosa strain PAK containing apt and anr | This study |

| p2127 | PA2127 gene from PAO1 cloned into pPSV35 | This study |

| p2126.1 | PA2126.1 gene from PAO1 cloned into pPSV35 | This study |

| p2126 | PA2126 gene from PAO1 cloned into pPSV35 | This study |

| p2127-2126.1 | PA2127 and PA2126.1 genes from PAO1 cloned into pPSV35 | This study |

| p2126.1-2126 | PA2126.1 and PA2126 genes from PAO1 cloned into pPSV35 | This study |

| p2126-2127 | PA2126 and PA2127 genes from PAO1 cloned into pPSV35 | This study |

| pM | pMMB67EH vector with carbenicillin resistance gene (bla), lacIq, and tac promoter | 12 |

| pM-MvaT | mvaT from PAO1 cloned into pMMB67EH | 38 |

| pAnr | anr from PAO1 cloned into pPSV35 | This study |

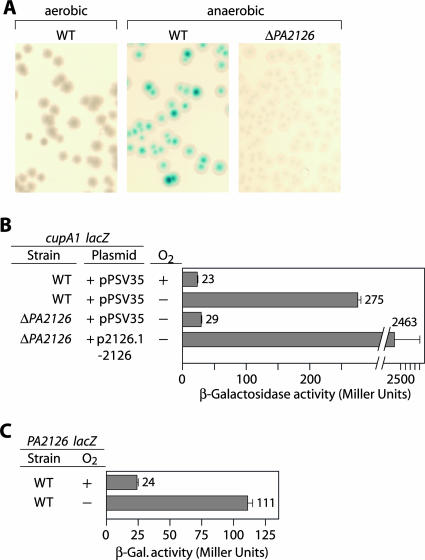

FIG. 5.

Anaerobiosis promotes phase-variable expression of the cupA genes and stimulates expression of the cgr genes. (A) Phenotypes of the wild-type cupA lacZ reporter strain grown under aerobic or anaerobic conditions and the ΔPA2126 cupA lacZ reporter strain grown under anaerobic conditions. Strains were grown at 37°C on LBN agar containing X-Gal. Only the wild-type reporter strain gave rise to blue (phase-on) and pale blue (phase-off) colonies when cells were grown under anaerobic conditions. (B) Quantification of cupA lacZ expression in cells of the wild-type and ΔPA2126 reporter strains containing the indicated plasmids. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of O2 as indicated. Plasmid p2126.1-2126 directs the synthesis of PA2126.1 plus PA2126 and is derived from the parent vector pPSV35. (C) Quantification of PA2126-lacZ expression in cells of the wild-type reporter strain grown in the presence or absence of O2. WT, wild type; β-Gal., β-galactosidase.

Construction of strains and plasmids.

Deletion constructs for the PA2127 and PA2126 genes were generated by amplifying flanking regions by PCR and then splicing the flanking regions together by overlap extension PCR. The deletions were in frame and contained the following linker sequences: 5′-GAATTC-3′ and 5′-AAGCTTTGGGAG-3′, respectively. The resulting PCR products were then cloned into plasmids pEX18Gm (17) and pEXG2 (24), yielding plasmids pEX-ΔPA2127 and pEX-ΔPA2126. These plasmids were then used to create strains PAO1 ΔPA2127 cupA lacZ, PAO1 ΔPA2126 cupA lacZ, PAO1 ΔmvaT ΔPA2127 cupA lacZ, and PAO1 ΔmvaT ΔPA2126 cupA lacZ containing in-frame deletions of the PA2127 and PA2126 genes by allelic exchange. Deletions were confirmed by PCR. Strains PAO1 cupA lacZ and PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ have been described previously (38).

Partial deletion constructs for the PA2127, PA2126.1, and PA2126 genes were generated using the same principle, and this yielded plasmids pEX-PΔ2127, pEX-PΔ2126.1, and pEX-PΔ2126, which allowed deletion of all but the last codon of the PA2127 gene, replacement of the intergenic region between the PA2127 and PA2126 genes by the linker 5′-AAGCTT-3′, and deletion of all but the 27 first codons of the PA2126 gene, respectively. These plasmids were then used to create strains PAO1 ΔmvaT PA2127 cupA lacZ, PAO1 ΔmvaT PA2126.1 cupA lacZ, and PAO1 ΔmvaT PA2126 cupA lacZ containing partial deletions of the PA2127, PA2126.1, and PA2126 genes, respectively, by allelic exchange. Deletions were confirmed by PCR.

The PA2126 lacZ reporter strain contained the lacZ gene integrated immediately downstream of the PA2126 gene on the PAO1 chromosome and was made by allelic exchange. Flanking PCR products were amplified and spliced together in order to add KpnI, NcoI, and SphI sites one base after the PA2126 gene stop codon. The resulting PCR product was cloned on a SacI/PacI fragment into pEXG2 (24), yielding plasmid pEXG2-PA2126. The lacZ gene was subsequently cloned into this construct on a KpnI/SphI fragment derived from plasmid pP18-lacZ (Arne Rietsch, unpublished data), generating plasmid pEXG2-PA2126-lacZ. This plasmid was then used to create reporter strains PAO1 PA2126 lacZ and PAO1 ΔmvaT PA2126 lacZ by allelic exchange.

The PA2127 lacZ reporter strain contained the promoter region of the PA2127 gene (pPA2127) cloned upstream of lacZ and inserted at the φCTX attachment site on the PAO1 chromosome (18). The 637 bp of DNA upstream of the PA2127 gene start codon was amplified by PCR and cloned upstream of lacZ in the Mini CTX lacZ vector (18), yielding plasmid Mini CTX PA2127-lacZ. This plasmid was then used essentially as described previously (18) to introduce the pPA2127-lacZ fusion at the φCTX attachment site on the chromosomes of PAO1 and PAO1 ΔmvaT, creating reporter strains PAO1 attB::pPA2127-lacZ and PAO1 ΔmvaT attB::pPA2127-lacZ, respectively.

A deletion construct for anr was generated by amplifying flanking regions by PCR and then splicing the flanking regions together by overlap extension PCR. The deletion was in frame and contained the linker sequence 5′-GAATTC-3′. The resulting PCR product was then cloned into plasmid pEX18Gm (17), yielding plasmid pEX-Δanr. This plasmid was then used to create strains PAO1 Δanr cupA lacZ and PAO1 ΔmvaT Δanr cupA lacZ, each containing an in-frame deletion of anr, by allelic exchange. The anr deletion in each strain was confirmed by PCR.

The P. aeruginosa genomic DNA library was a gift from Arne Rietsch (Case Western Reserve University). The library was made from genomic DNA of P. aeruginosa strain PAK that had been partially digested with Sau3AI and size fractionated. DNA in the 2- to 5-kb size range was cloned into BamHI-digested pPSV35 (24) to make the library. Plasmids pPSV35-1 (see Fig. 1) and pPSV35-4 (see Fig. 4) were isolated from the library. To make pPSV35-2, a HindIII fragment (containing the PA2126, PA2126.1, and PA2127 genes) was excised from pPSV35-1, and the backbone was recircularized. The same HindIII fragment was subcloned into pPSV35, generating plasmid pPSV35-3.

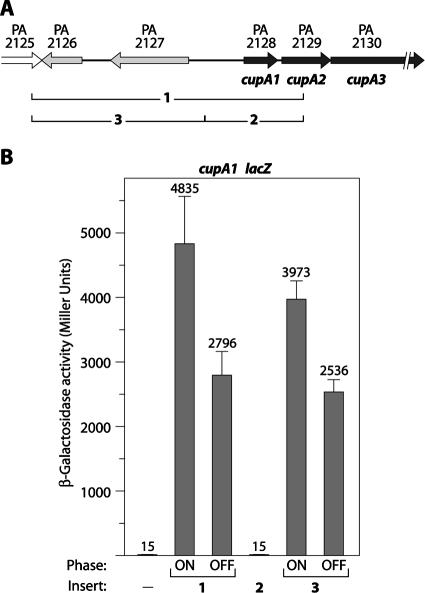

FIG. 1.

Plasmids containing the PA2126 and PA2127 genes promote phase-variable expression of the cupA genes in P. aeruginosa. (A) Organization of genes within and upstream of the cupA gene cluster. The DNAs corresponding to inserts 1, 2, and 3 are indicated at the bottom. (B) Quantification of cupA lacZ expression in cells of the wild-type reporter strain harboring plasmids with the indicated DNA inserts. Cells were grown in the presence of 1 mM IPTG and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Where indicated, cultures were obtained from phase-on or phase-off colonies. Phase-variable expression of the cupA lacZ reporter was not observed in cells containing the parent plasmid pPSV35 or in cells containing the plasmid carrying insert 2 (pPSV35-2).

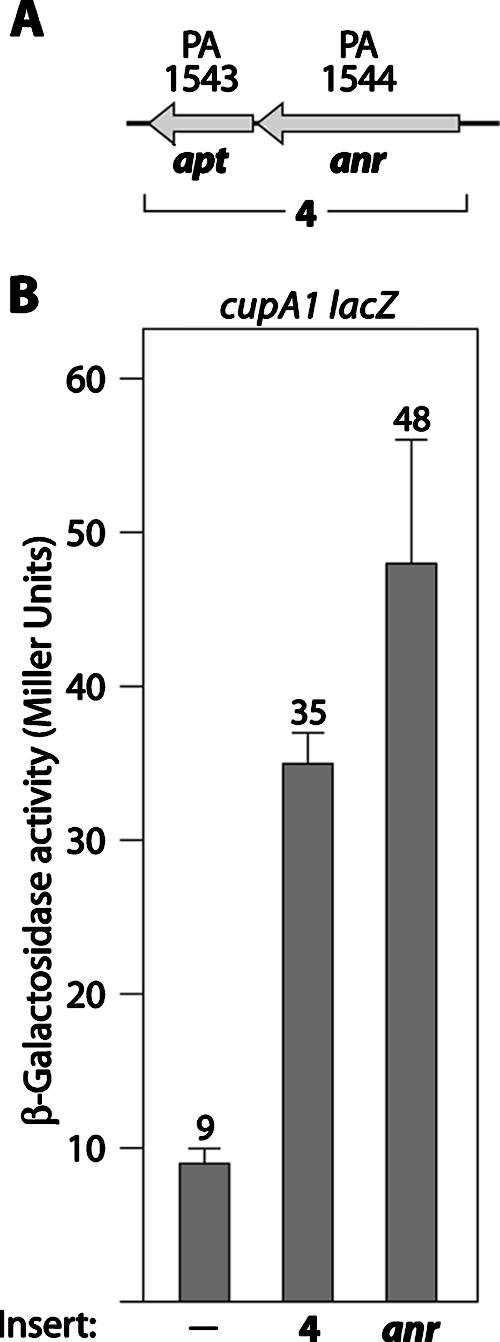

FIG. 4.

Plasmids containing the anr gene stimulate cupA gene expression in P. aeruginosa. (A) Organization of the apt and anr genes. DNA corresponding to the DNA contained on insert 4 is indicated. (B) Quantification of cupA lacZ expression in cells of the wild-type reporter strain harboring plasmids with the indicated DNA inserts. Plasmid pAnr, a derivative of pPSV35, was the source of the anr gene. Cells were grown in the presence of 1 mM IPTG and assayed for β-galactosidase activity.

Plasmids p2127, p2126.1, p2126, and pAnr are derivatives of pPSV35 and direct the synthesis of the PA2127, PA2126.1, PA2126, and Anr proteins, respectively, under control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible lacUV5 promoter. The plasmids were made by cloning PCR-amplified DNA fragments containing each of the PA2127, PA2126.1, PA2126, and anr genes from P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 into pPSV35.

Plasmids p2127-2126.1 and p2126.1-2126 were made by cloning PCR-amplified DNA fragments containing either the PA2127 and PA2126.1 genes or the PA2126.1 and PA2126 genes from P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 into pPSV35. Plasmid p2126-2127 was made by cloning a PCR-amplified DNA fragment containing the PA2126, PA2126.1, and PA2127 genes from P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 into pPSV35. Plasmid pM-MvaT directs the synthesis of P. aeruginosa MvaT under control of the IPTG-inducible tac promoter and has been described previously (38). Plasmid pMMB67EH, from which pM-MvaT was derived, has been described previously (12).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Cells were grown at 37°C either in LB with aeration or in LBN under anaerobic conditions. Media were supplemented as needed with gentamicin (25 μg/ml) or carbenicillin (300 μg/ml) and IPTG at the concentration indicated. Cells were permeabilized with sodium dodecyl sulfate and CHCl3 and assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described previously (8). Assays were performed at least three times in triplicate on separate occasions. Representative data sets are shown below. The values are averages based on one experiment.

Microarray experiments.

Cells of PAO1 containing plasmid pPSV35-3 or pPSV35 were grown with aeration at 37°C in LB containing gentamicin (25 μg/ml). Duplicate cultures of each strain were inoculated at a starting optical density at 600 nm of 0.01 and grown to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.5 (corresponding to the mid-logarithmic phase of growth). RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and cDNA fragmentation and labeling were performed essentially as described previously (42). Labeled samples were hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip P. aeruginosa genome arrays (Affymetrix). Data were analyzed for statistically significant changes in gene expression using GeneSpring GX. The genes whose expression changed fivefold or more, with a P value of ≤0.01, are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Microarray analysis of genes controlled by overexpression of the PA2126 and PA2127 genes during the mid-logarithmic phase of growth

| Gene | Designation | Fold change | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA2129 | cupA2 | 144.7 | CupA2, chaperone |

| PA2130 | cupA3 | 48.1 | CupA3, usher |

| PA2132 | cupA5 | 15.5 | CupA5, chaperone |

| PA3384 | phnC | 6.2 | PhnC, component of ABC transporter |

| PA0718 | 6.0 | Hypothetical from bacteriophage Pf1 | |

| PA0238 | 5.3 | Hypothetical | |

| PA4603 | −5.6 | Hypothetical | |

| PA0679 | −6.7 | Hypothetical | |

| PA1328 | −7.5 | Transcription regulator, LysR family | |

| PA4186 | −7.8 | Hypothetical | |

| PA5256 | dsbH | −8.1 | DsbH, disulfide bond formation protein |

| PA4799 | −15.2 | Hypothetical |

RESULTS

Genetic screen for positive regulators of cupA gene expression.

When cells of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 are grown at 37°C in LB, expression of the cupA fimbrial genes is tightly repressed by MvaT (37, 38). In an attempt to identify positive regulators of cupA gene expression, we screened a plasmid library of P. aeruginosa genomic DNA for plasmids that stimulated expression of a chromosomal cupA lacZ reporter. Specifically, we introduced into reporter strain PAO1 cupA lacZ (38) a library of plasmids containing different portions of P. aeruginosa genomic DNA and isolated the transformants that gave rise to blue colonies on LB agar plates containing X-Gal. Plasmids isolated from these transformants were retransformed into reporter strain PAO1 cupA lacZ to confirm the plasmid linkage of the observed phenotype. Restriction analysis of the isolated plasmids and subsequent sequence analysis of the corresponding genomic DNA inserts revealed that we had isolated two different plasmids that stimulated cupA gene expression. One of these plasmids, referred to here as pPSV35-1, contained DNA spanning part of the PA2125 gene through the middle of the cupA2 (PA2129) gene (referred to as insert 1) (Fig. 1A). We have previously shown that the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner in the absence of MvaT (38). We found that the cupA genes are also expressed in a phase-variable manner in cells containing plasmid pPSV35-1 (Fig. 1B and data not shown). In particular, reporter strain cells carrying plasmid pPSV35-1 gave rise to both dark and pale blue colonies on LB agar plates containing X-Gal; when cells were restreaked onto LB agar plates containing X-Gal, dark blue colonies gave rise to both dark and pale blue colonies, and pale blue colonies gave rise to both pale and dark blue colonies. Quantification of cupA gene expression revealed that there is at least an ∼320-fold difference in cupA gene expression between phase-on cells (cells derived from phase-on, dark blue colonies) carrying pPSV35-1 and wild-type cells containing the pPSV35 parent plasmid (Fig. 1B).

To better define which portion of insert 1 was responsible for the stimulatory effect on cupA gene expression, we subcloned two different portions of insert 1 (corresponding to inserts 2 and 3 shown in Fig. 1A) into the pPSV35 parent vector. The plasmid containing insert 2 failed to stimulate cupA gene expression, whereas the plasmid containing insert 3 stimulated cupA gene expression to levels approaching those seen in cells with the plasmid containing insert 1 (Fig. 1B). As we had seen for cells with the plasmid containing insert 1, cells with the plasmid containing insert 3 expressed the cupA genes in a phase-variable manner (Fig. 1B and data not shown). Although the genomic DNA in plasmid pPSV35-1 and its derivatives originates from P. aeruginosa strain PAK, cells with a plasmid (p2126-2127) containing the PA2126 and PA2127 genes from P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 also expressed the cupA genes in a phase-variable manner (data not shown). These findings suggest that plasmids containing the PA2126 and PA2127 genes can promote phase-variable expression of the cupA genes in P. aeruginosa.

Genes that map immediately upstream of the cupA operon positively control cupA gene expression.

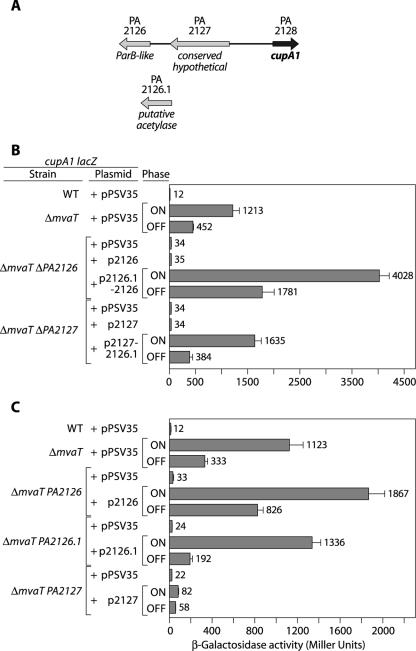

The PA2126 and PA2127 genes encode a ParB-like protein and a conserved hypothetical protein of unknown function, respectively (Fig. 2A). Strikingly, homologs of the PA2126 and PA2127 genes have previously been implicated in the control of genes encoding immunoglobulin-binding proteins in E. coli (27). We reasoned that if the PA2126 and PA2127 genes were important for cupA gene expression, then deletion of either one of these genes should reduce cupA gene expression in an mvaT mutant background. To test these predictions, we introduced in-frame deletions of either the PA2126 gene (ΔPA2126) or the PA2127 gene (ΔPA2127) into an mvaT mutant derivative of our cupA reporter strain (38). Deletion of either the PA2126 or PA2127 gene dramatically reduced cupA gene expression in the ΔmvaT mutant background (Fig. 2B). Surprisingly, phase-variable expression of the cupA genes could not be complemented in either the ΔmvaT ΔPA2126 mutant background or the ΔmvaT ΔPA2127 mutant background with either the PA2126 gene or the PA2127 gene in trans (Fig. 2B). We discovered that our failure to complement either the ΔPA2126 or ΔPA2127 in-frame deletion mutant was due to the fact that there is a third gene, referred to here as the PA2126.1 gene (see the supplemental material), not previously annotated on the PAO1 genome (http://www.pseudomonas.com) and overlapping both the PA2126 and PA2127 genes (Fig. 2A), that is also required for cupA gene expression. Therefore, both our ΔPA2126 and ΔPA2127 in-frame deletion mutants also contained mutations in the PA2126.1 gene. In keeping with this idea, the ΔPA2126 mutant could be complemented by a plasmid expressing both the PA2126.1 and PA2126 genes, and the ΔPA2127 mutant could be complemented by a plasmid expressing both the PA2127 and PA2126.1 genes (Fig. 2B). The PA2126.1 gene appears to encode a protein with homology to members of the Gcn5-related N-acetyltransferase (GNAT) superfamily (40).

FIG. 2.

Genes that map immediately upstream of the cupA operon are required for cupA gene expression in an mvaT mutant background. (A) Organization of genes that map immediately upstream of the cupA gene cluster. The PA2126 gene encodes a ParB-like protein; the PA2126.1 gene, which was discovered in this study, encodes a putative acetylase; and the PA2127 gene encodes a hypothetical protein of unknown function. (B) Quantification of cupA lacZ expression in cells of the wild-type, ΔmvaT, ΔmvaT ΔPA2126, and ΔmvaT ΔPA2127 reporter strains containing the indicated plasmids. (C) Quantification of cupA lacZ expression in cells of the wild-type, ΔmvaT, ΔmvaT PA2126, ΔmvaT PA2126.1, and ΔmvaT PA2127 reporter strains containing the indicated plasmids. For panels B and C cells were grown in the presence of 1 mM IPTG and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Plasmids p2126, p2126.1, p2127, p2126.1-2126, and p2127-2126.1 direct the synthesis of the PA2126, PA2126.1, PA2127, PA2126.1 plus PA2126, and PA2127 plus PA2126.1 proteins, respectively, and were derived from the parent vector pPSV35. Where indicated, cultures were obtained from phase-on or phase-off colonies. Note that overexpression of the PA2126, PA2126.1 (data not shown), or PA2127 gene does not suffice to promote phase-variable expression of the cupA genes. WT, wild type.

To assess the individual contributions of the PA2126, PA2126.1, and PA2127 genes to cupA gene expression, we constructed three additional mutant strains. Specifically, we introduced mutations affecting the PA2126, PA2126.1, or PA2127 gene into our ΔmvaT cupA lacZ reporter strain. Figure 2C shows that mutation of the PA2126, PA2126.1, or PA2127 gene abolished cupA gene expression in the ΔmvaT mutant background. Furthermore, the effects of the PA2126, PA2126.1, and PA2127 gene mutations on cupA gene expression could be complemented with the corresponding wild-type gene in trans (Fig. 2C). Note that although the plasmid expressing the PA2127 gene alone only weakly complemented the PA2127 mutant (Fig. 2C), the importance of the PA2127 gene in cupA gene expression was further demonstrated by the fact that a plasmid expressing both the PA2127 and PA2126.1 genes could complement the in-frame PA2127 deletion mutant (ΔPA2127) (Fig. 2B), whereas a plasmid expressing the PA2126.1 gene alone could not do this (data not shown). Our findings suggest that the PA2127, PA2126.1, and PA2126 genes are important for expression of the cupA genes in an mvaT mutant background. We therefore designated the PA2127, PA2126.1, and PA2126 genes cupA gene regulator A (cgrA), cgrB, and cgrC, respectively.

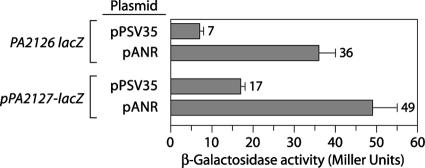

MvaT controls expression of the cgr genes.

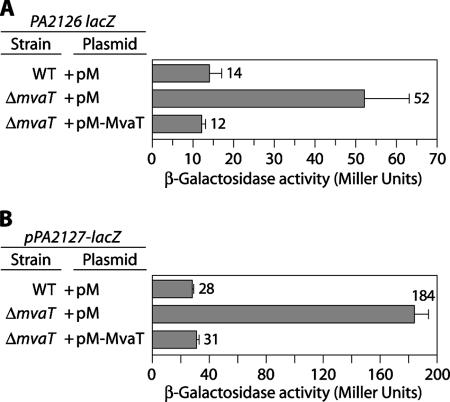

MvaT has previously been shown to repress cupA gene expression (37, 38). However, it is not known whether MvaT exerts its effect on cupA gene expression directly (for example, by binding to the cupA promoter region) or indirectly through effects on other regulators that control cupA gene expression or both. In order to test whether MvaT controls cupA gene expression, at least in part, through an effect on expression of the cgr genes, we constructed two additional reporter strains. In one of these strains lacZ was placed downstream of the PA2126 (cgrC) gene on the PAO1 chromosome. In the other strain, the cupA1-PA2127 intergenic region was placed upstream of lacZ such that the putative PA2127 promoter(s) was driving expression of lacZ and a single copy of the resulting PA2127 gene-lacZ reporter fusion was inserted into the φCTX attachment site in the PAO1 chromosome (18). Subsequently, we introduced an in-frame deletion of the mvaT gene into each of these reporter strains. Figure 3A shows that deletion of mvaT resulted in an ∼4-fold increase in expression of the PA2126 (cgrC) gene and presumably the entire cgrABC operon. This effect of the mvaT deletion could be complemented with the mvaT gene supplied in trans (Fig. 3A). Consistent with these findings, deletion of mvaT resulted in an ∼6-fold increase in expression of the PA2127-lacZ reporter (Fig. 3B). These findings suggest that expression of the cgr genes is repressed, either directly or indirectly, by MvaT. We infer from this that MvaT represses cupA gene expression, at least in part, by repressing expression of the cgr genes, which positively regulate cupA gene expression. Note that although the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner in an mvaT mutant background (38), we did not see phase-variable expression of either the PA2126-lacZ reporter or the PA2127-lacZ reporter in the absence of MvaT. Phase-variable expression of the cgr genes is therefore unlikely to account for the phase-variable expression of the cupA genes that occurs in an mvaT mutant background.

FIG. 3.

MvaT represses expression of the cgr genes. (A) Quantification of PA2126-lacZ expression in cells of the wild-type reporter strain and the ΔmvaT mutant derivative harboring the indicated plasmids. Plasmid pM-MvaT directs the synthesis of MvaT and was derived from plasmid pMMB67EH, which is designated pM here. The PA2126-lacZ reporter strain contains the lacZ gene placed downstream of the PA2126 gene on the PAO1 chromosome. Cells were grown in the presence of 1 mM IPTG and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. (B) Quantification of PA2127-lacZ expression in cells of the wild-type reporter strain (PAO1 attB::pPA2127-lacZ) and the ΔmvaT mutant derivative harboring the indicated plasmids. The plasmids and experimental conditions are the same as those described above for panel A. The PA2127-lacZ reporter strains contain the PA2127 promoter(s) driving expression of a linked lacZ reporter gene integrated as a single copy into the φCTX attachment site on the PAO1 chromosome. WT, wild type.

Microarray analyses of genes regulated by the cgr gene cluster.

Expression of the cgr genes from a multicopy plasmid results in an ∼320-fold increase in cupA gene expression (Fig. 1B). To determine whether the expression of other genes in addition to those of the cupA operon is controlled by the cgr genes, we used DNA microarrays. In particular, we compared the global gene expression profiles of cells carrying a multicopy plasmid encoding the cgr locus and cells carrying a control plasmid using the P. aeruginosa GeneChip microarrays from Affymetrix. Table 2 shows that the expression of only 12 genes changed fivefold or more when the cgr genes were overexpressed, and of these, the cupA genes were most strongly affected. These findings suggest that the products of the cgr genes function primarily as local regulators and do not control the expression of many of the other MvaT-controlled genes in P. aeruginosa (37).

Anr can influence cupA gene expression.

Our genetic screen for positive regulators of cupA gene expression identified a second plasmid that stimulated cupA gene expression. This plasmid had a relatively modest effect on cupA gene expression and contained DNA encompassing the apt and anr genes encoding adenine phosphoribosyltransferase and the Fnr-like transcription activator Anr, respectively (Fig. 4). Moreover, a plasmid expressing anr alone had an equal stimulatory effect on cupA gene expression (Fig. 4B), whereas a plasmid expressing apt alone had no effect on cupA gene expression (data not shown). These findings suggest that Anr can influence cupA gene expression, either directly or indirectly. Although Anr typically controls the expression of genes under anaerobic conditions (29, 48), Anr can also influence gene expression under aerobic conditions (26). To determine whether Anr is essential for cupA gene expression under aerobic conditions, we created a derivative of our PAO1 ΔmvaT cupA lacZ reporter strain carrying an in-frame deletion of the anr gene. Quantification of cupA gene expression in this Δanr mutant revealed that deletion of anr resulted in a modest decrease (less than twofold) in cupA gene expression (data not shown), suggesting that unlike the products of the cgr genes, Anr is not essential for cupA gene expression in the absence of MvaT. We were unable to accurately assess the contribution of Anr to cupA gene expression under anaerobic conditions because anr is essential under the conditions used in our experiments, in which nitrate is used as the terminal electron acceptor to support anaerobic respiration (46, 48).

Anaerobiosis promotes phase-variable expression of the cupA genes.

We have previously shown that the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner in the absence of MvaT (38). However, we have been unable to detect phase-variable expression of the cupA genes in the presence of MvaT (i.e., in wild-type cells). Because Anr can influence cupA gene expression (Fig. 4) and because Anr typically controls the expression of genes under anaerobic conditions, we next asked whether the cupA genes were expressed in a phase-variable manner under anaerobic conditions. Cells of the PAO1 cupA lacZ reporter strain gave rise to both blue and pale blue colonies on LB agar plates containing nitrate and X-Gal when the cells were grown anaerobically but not when the cells were grown aerobically (Fig. 5A). When cells were restreaked on LB agar plates containing X-Gal and nitrate, following incubation under anaerobic conditions, blue colonies gave rise to both blue and pale blue colonies, and pale blue colonies gave rise to both blue and pale blue colonies (data not shown). These findings are consistent with the idea that the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner when cells are grown anaerobically. Moreover, expression of the cupA genes under anaerobic conditions is dependent on the cgr genes since phase-variable expression of the cupA genes could not be detected under anaerobic conditions in the ΔPA2126 mutant (containing mutations in both the PA2126/cgrC and PA2126.1/cgrB genes) (Fig. 5A and B) or in any other cgr mutant strain (data not shown).

Anaerobiosis stimulates expression of the cgr genes.

Because the cgr genes are important for cupA gene expression under anaerobic conditions, we next asked whether expression of the cgr genes was controlled by anaerobiosis. Figure 5C shows that expression of the PA2126-lacZ reporter was ∼4-fold higher in cells grown under anaerobic conditions than in cells grown aerobically. We inferred from this that expression of the PA2126 (cgrC) gene and presumably the rest of the cgr genes is upregulated in response to growth under anaerobic conditions.

Anr stimulates expression of the cgr genes.

Expression of anr from a multicopy plasmid stimulates cupA gene expression (Fig. 4B). To begin to address whether Anr mediates its stimulatory effect through an effect on the cgr genes, we introduced a plasmid containing anr together with a control plasmid into the PA2126-lacZ and PA2127-lacZ reporter strains and quantified reporter gene expression by measuring β-galactosidase activity. Figure 6 shows that expression of anr from a multicopy plasmid resulted in an ∼6-fold increase in expression of the PA2126 gene and an ∼3-fold increase in expression of the PA2127-lacZ reporter. These findings suggest that Anr can influence expression of the cgr genes. Taken together, our findings suggest that anaerobiosis promotes phase-variable expression of the cupA genes, at least in part, through an effect on cgr gene expression. Moreover, they suggest that the effect of anaerobiosis on cgr gene expression is mediated, either directly or indirectly, by Anr.

FIG. 6.

Plasmid containing the anr gene stimulates cgr gene expression in P. aeruginosa: quantification of PA2126-lacZ expression and quantification of PA2127-lacZ expression in cells of wild-type reporter strains harboring the indicated plasmids. Cells were grown in the presence of 1 mM IPTG and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Plasmid pAnr, a derivative of pPSV35, was the source of the anr gene.

DISCUSSION

Using a genetic screen, we identified four previously undescribed positive regulators of cupA gene expression in P. aeruginosa. These regulators include three local regulators encoded by the cgrABC genes and Anr, a global regulator of anaerobic gene expression. Moreover, through the identification of Anr, we were able to identify anaerobiosis as one environmental condition under which the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner; previously, we had observed phase-variable expression of the cupA genes only in the absence of MvaT (i.e., in an mvaT mutant background) (38). All three of the cgr genes appear to be required for phase-variable expression of the cupA genes. Although we suspect that the cgr genes are required for cupA gene expression, it is also possible that they simply serve to switch on phase-variable expression of the cupA operon, or both.

How do the cgr genes positively regulate cupA gene expression?

Our microarray experiments suggested that the effects of the Cgr regulators are largely limited to the cupA genes. The Cgr regulators themselves are unusual in that they do not resemble any classical positive regulator of gene expression. CgrC (PA2126) belongs to the ParB family of DNA-binding proteins, which often contain a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif and are typically involved in DNA partitioning (15, 19, 31). However, ParB family members are also known to control gene expression. For example, the ParB protein from the E. coli P1 plasmid can repress expression of genes flanking the P1 centromere (25). Although most ParB-like proteins that influence gene expression tend to function as repressors or silencers (5, 21, 23, 25, 45), there are several examples where ParB-like proteins positively regulate gene expression. Indeed, VirB from Shigella flexneri is a ParB-like protein that functions exclusively as a transcription regulator and mediates its positive effects on virulence gene expression by displacing the negative regulator H-NS (4, 35). Of particular relevance to the Cgr system, the ParB-like IbrB protein has been implicated in the positive control of gene expression in E. coli strain ECOR-9 (27). In particular, it is thought that IbrB functions together with IbrA, a homolog of CgrA, to coregulate expression of the prophage-associated eib genes, which encode immunoglobulin-binding proteins. However, the mechanism of action of IbrA and IbrB is unknown.

Sequence analysis and structural prediction algorithms suggest that CgrA is a member of the adenine nucleotide α-hydrolase superfamily. This family includes the phosphoadenosine phosphosulfate/adenosine phosphosulfate reductases, ATP sulfurylases, and N-type ATP pyrophosphatases (28). Like IbrA (27), CgrA contains a putative phosphoadenosine phosphosulfate/adenosine phosphosulfate-binding domain, and it will be interesting to determine whether this domain within CgrA is important for its activity.

CgrB is a putative member of the GNAT family of acetyl transferases (40). Although acetylases belonging to the GNAT family play important roles in regulating gene expression in eukaryotes (22, 33), there are few examples in which acetylases are known to influence gene expression in prokaryotes (10, 41). Perhaps CgrB acetylates either CgrA or CgrC to promote its activity. It is also possible that CgrB targets a small molecule, the acetylation of which is required for either CgrA or CgrC to function. Nevertheless, whether CgrB is truly an acetylase and how CgrB functions together with CgrA and CgrC to positively control cupA gene expression remain to be determined.

Because CgrC is predicted to be a DNA-binding protein, we speculate that CgrC may regulate cupA gene expression by binding directly to the cupA1 promoter region and, together with CgrA and CgrB, function either to remove a repressor from the cupA promoter DNA or to activate transcription from the cupA1 promoter(s). If the Cgr proteins do function to remove a repressor from the cupA1 promoter region, that repressor is unlikely to be MvaT, since we have shown that the cgr genes are required for cupA gene expression in the absence of MvaT.

It is important to note that we do not yet know the mechanism governing phase-variable expression of the cupA genes. It is possible that the cgr genes themselves somehow mediate phase-variable expression of the cupA genes or that some yet-to-be-identified factor(s) is responsible.

Mechanism by which MvaT represses cupA gene expression.

We and others have previously shown that MvaT represses expression of the cupA genes (37, 38). Here we found that MvaT represses cgr gene expression, suggesting that MvaT represses cupA gene expression, at least in part, by repressing the expression of genes encoding positive regulators of cupA gene expression. Our findings are consistent with those of a previous study in which the cgrA (PA2127) transcript was found by DNA microarray to be ∼2-fold more abundant in cells of an mvaT mutant strain than in cells of the wild-type strain (37).

Phase-variable expression of the cupA genes under anaerobic conditions.

We have presented evidence that the cupA genes are expressed in a phase-variable manner when cells are grown anaerobically. Consistent with these findings, previous microarray analyses found that cupA gene expression was induced during anaerobic growth (1, 9) and during growth under microaerophilic conditions (1). We have also shown that the presence of anr on a multicopy plasmid can stimulate expression of both the cupA genes and the cgr genes under aerobic conditions and that cgr gene expression is upregulated during anaerobic growth. In support of the latter finding, a recent proteomic analysis of P. aeruginosa revealed that CgrA (PA2127) was more abundant in cells grown anaerobically than in cells grown aerobically (44). Our findings suggest that under anaerobic conditions, expression of the cgr genes is induced in an Anr-dependent fashion, resulting in a concomitant increase in cupA gene expression. Although we do not yet know whether Anr regulates expression of the cgr or cupA genes (or both) directly, we have discovered a putative Anr-binding site within the cgrA-cupA1 intergenic region (Sandra Castang and S. L. Dove, unpublished). Because P. aeruginosa encodes a second Anr ortholog, called Dnr (2), which recognizes similar binding sites and whose expression is dependent upon Anr (3, 14, 30), it is important to determine whether any role that this site might play is a direct result of Anr binding.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the microbial environment in the chronically infected CF lung is largely anaerobic (43, 47). Our finding that phase-variable expression of the cupA genes occurs under anaerobic conditions raises the possibility that phase-variable expression of the cupA genes may occur in cells of P. aeruginosa growing in the CF host lung. Because the cupA genes can influence biofilm formation in vitro (11, 20, 36), it is important to determine whether the cupA genes are expressed in vivo and, if they are, what role they play in the host lung environment. Perhaps, under the anaerobic conditions of the CF host lung, expression of the cupA genes (in phase-on cells) facilitates the initial formation of the biofilm. Subsequent switching to the phase-off expression state might better enable cells to persist either because it could facilitate escape from the biofilm and subsequent colonization of other sites or because it could facilitate immune evasion by cells that no longer produce immunogenic CupA fimbriae. Indeed, in many instances the phase-variable expression of bacterial surface structures is thought to provide a mechanism for immune evasion (39). Any heterogeneity in the cell population that would result from phase-variable expression of the cupA genes may therefore contribute to the long-term survival of P. aeruginosa in the CF host lung.

We have shown that anaerobic growth is an important environmental cue for phase-variable expression of the cupA genes. Although several other phase variation systems are responsive to environmental conditions (16, 39), the cupA system appears to be an example of a system in which phase variation occurs only in response to a specific environmental stimulus. Precisely how the components of the regulatory cascade that we have described are integrated into the regulatory mechanism controlling phase-variable expression of the cupA genes remains to be determined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Arne Rietsch for the P. aeruginosa PAK genomic library, Anja Brencic for help with microarray experiments, and Renate Hellmiss for artwork. We thank Ann Hochschild, Stephen Lory, Joseph Mougous, and Arne Rietsch for discussions and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI069007 (to S.L.D.). J.S.S. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 September 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez-Ortega, C., and C. S. Harwood. 2007. Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to low oxygen indicate that growth in the cystic fibrosis lung is by aerobic respiration. Mol. Microbiol. 65:153-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai, H., Y. Igarashi, and T. Kodama. 1995. Expression of the nir and nor genes for denitrification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires a novel CRP/FNR-related transcriptional regulator, DNR, in addition to ANR. FEBS Lett. 371:73-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arai, H., T. Kodama, and Y. Igarashi. 1997. Cascade regulation of the two CRP/FNR-related transcriptional regulators (ANR and DNR) and the denitrification enzymes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 25:1141-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beloin, C., and C. J. Dorman. 2003. An extended role for the nucleoid structuring protein H-NS in the virulence gene regulatory cascade of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 47:825-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervin, M. A., G. B. Spiegelman, B. Raether, K. Ohlsen, M. Perego, and J. A. Hoch. 1998. A negative regulator linking chromosome segregation to developmental transcription in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 29:85-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costerton, J. W., P. S. Stewart, and E. P. Greenberg. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diggle, S. P., K. Winzer, A. Lazdunski, P. Williams, and M. Camara. 2002. Advancing the quorum in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: MvaT and the regulation of N-acylhomoserine lactone production and virulence gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 184:2576-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dove, S. L., and A. Hochschild. 2004. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on transcription activation. Methods Mol. Biol. 261:231-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filiatrault, M. J., V. E. Wagner, D. Bushnell, C. G. Haidaris, B. H. Iglewski, and L. Passador. 2005. Effect of anaerobiosis and nitrate on gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 73:3764-3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forouhar, F., I.-S. Lee, J. Vujcic, S. Vujciv, J. Shen, S. M. Vorobiev, R. Xiao, T. B. Acton, G. T. Montelione, C. W. Porter, and L. Tong. 2005. Structural and functional evidence for Bacillus subtilis PaiA as a novel N1-spermidine/spermine acetyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 280:40328-40336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman, L., and R. Kolter. 2004. Genes involved in matrix formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 51:675-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furste, J. P., W. Pansegrau, R. Frank, H. Blocker, P. Scholz, M. Bagdasarian, and E. Lanka. 1986. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene 48:119-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govan, J. R., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa, N., H. Arai, and Y. Igarashi. 1998. Activation of a consensus FNR-dependent promoter by DNR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in response to nitrite. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 166:213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes, F., and D. Barilla. 2006. Assembling the bacterial segrosome. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31:247-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernday, A., M. Krabbe, B. Braaten, and D. Low. 2002. Self-perpetuating epigenetic pili switches in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16470-16476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoang, T. T., A. J. Kutchma, A. Becher, and H. P. Schweizer. 2000. Integration-proficient plasmids for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: site-specific integration and use for engineering of reporter and expression strains. Plasmid 43:59-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khare, D., G. Ziegelin, E. Lanka, and U. Heinemann. 2004. Sequence-specific DNA binding determined by contacts outside the helix-turn-helix motif of the ParB homolog KorB. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:656-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulasekara, H. D., I. Ventre, B. R. Kulasekara, A. Lazdunski, A. Filloux, and S. Lory. 2005. A novel two-component system controls the expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa fimbrial cup genes. Mol. Microbiol. 55:368-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch, A. S., and J. C. Wang. 1995. SopB protein-mediated silencing of genes linked to the sopC locus of Escherichia coli F plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1896-1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marmorstein, R., and S. Y. Roth. 2001. Histone acetyltransferases: function, structure, and catalysis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11:155-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quisel, J. D., and A. D. Grossman. 2000. Control of sporulation gene expression in Bacillus subtilis by the chromosome partioning proteins Soj (ParA) and Spo0J (ParB). J. Bacteriol. 182:3446-3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rietsch, A., I. Vallet-Gely, S. L. Dove, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2005. ExsE, a secreted regulator of type III secretion genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:8006-8011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodionov, O., M. Lobocka, and M. Yarmolinsky. 1999. Silencing of genes flanking the P1 plasmid centromere. Science 283:546-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rompf, A., C. Hungerer, T. Hoffmann, M. Lindenmeyer, U. Romling, U. Gross, M. O. Doss, H. Arai, Y. Igarashi, and D. Jahn. 1998. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemF and hemN by the dual action of the redox response regulators Anr and Dnr. Mol. Microbiol. 29:985-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandt, C. H., J. E. Hopper, and C. W. Hill. 2002. Activation of prophage eib genes for immunoglobulin-binding proteins by genes from the IbrAB genetic island of Escherichia coli ECOR-9. J. Bacteriol. 184:3640-3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Savage, H., G. Montoya, C. Svensson, J. D. Schwenn, and I. Sinning. 1997. Crystal structure of phosphoadenylyl sulphate (PAPS) reductase: a new family of adenine nucleotide α hydrolases. Structure 5:895-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawers, G. R. 1991. Identification and molecular characterization of a transcriptional regulator from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 exhibiting structural and functional similarity to the FNR protein of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1469-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreiber, K., R. Krieger, B. Benkert, M. Eschbach, H. Arai, M. Schobert, and D. Jahn. 2007. The anaerobic regulatory network required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa nitrate respiration. J. Bacteriol. 189:4310-4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schumacher, M. A., and B. E. Funnell. 2005. Structures of ParB bound to DNA reveal mechanism of partition complex formation. Nature 438:516-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh, P. K., A. L. Schaefer, M. R. Parsek, T. O. Moninger, M. J. Welsh, and E. P. Greenberg. 2000. Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407:762-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterner, D. E., and S. L. Berger. 2000. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:435-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tendeng, C., O. A. Soutourina, A. danchin, and P. N. Bertin. 2003. MvaT proteins in Pseudomonas spp.: a novel class of H-NS-like proteins. Microbiology 149:3047-3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner, E. C., and C. J. Dorman. 2007. H-NS antagonism in Shigella flexneri by VirB, a virulence gene transcription regulator that is closely related to plasmid partition factors. J. Bacteriol. 189:3403-3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vallet, I., J. W. Olson, S. Lory, A. Lazdunski, and A. Filloux. 2001. The chaperone/usher pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of fimbrial gene clusters (cup) and their involvement in biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6911-6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vallet, I., S. P. Diggle, R. E. Stacey, M. Camara, I. Ventre, S. Lory, A. Lazdunski, P. Williams, and A. Filloux. 2004. Biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: fimbrial cup gene clusters are controlled by the transcriptional regulator MvaT. J. Bacteriol. 186:2880-2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vallet-Gely, I., K. E. Donovan, R. Fang, J. K. Joung, and S. L. Dove. 2005. Repression of phase-variable cup gene expression by H-NS-like proteins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:11082-11087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Woude, M. W., and A. J. Baumler. 2004. Phase and antigenic variation in bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:581-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vetting, M. W., L. P. S. de Carvalho, M. Yu, S. S. Hegde, S. Magnet, S. L. Roderick, and J. S. Blanchard. 2005. Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 433:212-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White-Ziegler, C. A., A. M. Black, S. H. Eliades, S. Young, and K. Porter. 2002. The N-acetyltransferase RimJ responds to environmental stimuli to repress pap fimbrial transcription in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:4334-4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfgang, M. C., V. T. Lee, M. E. Gilmore, and S. Lory. 2003. Coordinate regulation of bacterial virulence genes by a novel adenylate cyclase-dependent signaling pathway. Dev. Cell 4:253-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Worlitzsch, D., R. Tarran, M. Ulrich, U. Schwab, A. Cekici, K. C. Meyer, P. Birrer, G. Bellon, J. Berger, T. Weiss, K. Botzenhart, J. R. Yankaskas, S. Randell, R. C. Boucher, and G. Doring. 2002. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Investig. 109:317-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu, M., T. Guina, M. Brittnacher, H. Nguyen, J. Eng, and S. I. Miller. 2005. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa proteome during anaerobic growth. J. Bacteriol. 187:8185-8190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yarmolinsky, M. 2000. Transcriptional silencing in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:138-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye, R. W., D. Haas, J.-O. Ka, V. Krishnapillai, A. Zimmermann, C. Baird, and J. M. Tiedje. 1995. Anaerobic activation of the entire denitrification pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires Anr, an analog of Fnr. J. Bacteriol. 177:3606-3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoon, S. S., R. F. Hennigan, G. M. Hilliard, U. A. Ochsner, K. Parvatiyar, M. C. Kamani, H. L. Allen, T. R. DeKievit, P. R. Gardner, U. Schwab, J. J. Rowe, B. H. Iglewski, T. R. McDermott, R. P. Mason, D. J. Wozniak, R. E. W. Hancock, M. R. Parsek, T. L. Noah, R. C. Boucher, and D. J. Hassett. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa anaerobic respiration in biofilms: relationships to cystic fibrosis pathogenesis. Dev. Cell 3:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zimmermann, A., C. Reimann, M. Galimand, and D. Haas. 1991. Anaerobic growth and cyanide synthesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa depend on anr, a regulatory gene homologous with fnr of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1483-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.