Abstract

The population genetic structure of the animal pathogen Staphylococcus intermedius is poorly understood. We carried out a multilocus sequence phylogenetic analysis of isolates from broad host and geographic origins to investigate inter- and intraspecies diversity. We found that isolates phenotypically identified as S. intermedius are differentiated into three closely related species, S. intermedius, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, and Staphylococcus delphini. S. pseudintermedius, not S. intermedius, is the common cause of canine pyoderma and occasionally causes zoonotic infections of humans. Over 60 extant STs were identified among the S. pseudintermedius isolates examined, including several that were distributed on different continents. As the agr quorum-sensing system of staphylococci is thought to have evolved along lines of speciation within the genus, we examined the allelic variation of agrD, which encodes the autoinducing peptide (AIP). Four AIP variants were encoded by S. pseudintermedius isolates, and identical AIP variants were shared among the three species, suggesting that a common quorum-sensing capacity has been conserved in spite of species differentiation in largely distinct ecological niches. A lack of clonal association of agr alleles suggests that assortive recombination may have contributed to the distribution of agr diversity. Finally, we discovered that the recent emergence of methicillin-resistant strains was due to multiple acquisitions of the mecA gene by different S. pseudintermedius clones found on different continents. Taken together, these data have resolved the population genetic structure of the S. intermedius group, resulting in new insights into its ancient and recent evolution.

Staphylococcus intermedius is a member of the normal flora of dogs and is also a major opportunistic pathogen responsible for the common canine skin condition pyoderma (19). S. intermedius has also been found in association with other animal species (1, 3, 12, 16) and can occasionally cause severe infections of humans (26, 29, 37).

Despite its prevalence among many members of the animal kingdom, an understanding of the population genetics of S. intermedius is lacking. Until very recently, studies of the diversity of S. intermedius populations have been limited to phenotypic and molecular typing approaches (1, 3, 5, 12, 16-18, 40). A relatively high degree of phenotypic diversity exists within the species, leading to the identification of different biotypes associated with specific animal hosts (16, 28), and ribotyping studies have shown that strains are typically associated with only a single host species (1, 5). Canine strains were represented by a small number of distinct ribotypes, in contrast to strains from other animals, which generally had greater diversity (17). The level of phenotypic and genotypic diversity observed among S. intermedius isolates has led some investigators to speculate that an S. intermedius group (SIG) consisting of several species or subspecies may exist (5, 28). A closely related species, Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, was recently described (7) and has been isolated from several animal species, including healthy dogs in a veterinary clinic in Japan (32), and from a human infection (38). Very recently, a study of Japanese isolates based on DNA sequences of sodA and hsp60 genes identified three different species, S. intermedius, S. pseudintermedius, and Staphylococcus delphini, among isolates phenotypically identified as S. intermedius and suggested a reclassification of the species (33). However, the distribution of these different species among isolates from outside Japan was not examined.

Worryingly, methicillin-resistant strains of S. intermedius (MRSI) and S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) have recently emerged in veterinary clinics around the world (15, 22, 32, 44), but their evolutionary histories have not been examined. An understanding of the population genetics of S. intermedius is required to provide a much-needed framework for studies of the evolution, pathogenesis, and emerging methicillin resistance of S. intermedius. In order to investigate the population genetic structure of S. intermedius, we developed a multilocus sequencing approach that included five gene loci with a range of predicted nucleotide diversities to facilitate inter- and intraspecies differentiation. Broad new insights into the diversity of S. intermedius populations were obtained.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

In total, 105 isolates were examined, including 99 from an array of diseased and healthy animal species, such as dogs, humans, horses, camels, and pigeons, which were previously identified as S. intermedius in different centers in the United States, Canada, Japan, United Kingdom (including Scotland and England), France, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, and Sweden (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Identification was carried out with standard phenotypic tests that varied slightly depending on the laboratory but included production of coagulase and anaerobic acid from mannitol, sucrose, and d-trehalose and lack of hyaluronidase production, lack of growth on P agar containing acriflavin, and the production of β-galactosidase when grown in o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside broth according to the original description of the species by Hajek (16). In addition, the type strain of S. delphini, ATCC 49171 (39); four strains of the recently described S. pseudintermedius species, including the type strain, LMG 22219T (7); and the type strain of Staphylococcus schleiferi subsp. schleiferi, ATCC 43808 (11), were included in the study.

Bacterial growth conditions and genomic-DNA isolation.

Staphylococcal strains were grown on tryptic soy agar (Oxoid) at 37°C overnight or in tryptic soy broth (Oxoid) at 37°C overnight with shaking at 200 rpm. Genomic-DNA extraction was carried out with a bacterial genomic-DNA purification kit (Edge Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prior to incubation at 37°C for 10 min, 125 μg/ml lysostaphin (Ambi products) was included.

Gene loci selected for DNA sequence analysis.

Five loci, the 16S rRNA, cpn60 (hsp60), tuf, pta, and agrD genes, were selected for DNA sequence analysis. 16S rRNA, cpn60, and tuf have been used previously in single-locus approaches to differentiating staphylococcal species (7, 13, 24, 25), and cpn60, tuf, and pta have been incorporated into multilocus sequence-typing schemes for differentiating strains of several different bacterial species (2, 10, 43). The accessory gene regulator (agr) quorum-sensing system found in the majority of staphylococcal species examined (8) is thought to have diversified along lines of speciation, giving rise to a number of subspecies groups that have the capacity for intra- and interspecies inhibition of virulence (30, 42). We examined the allelic variation of agrD, which encodes the autoinducing peptide (AIP), to further investigate both inter- and intraspecies differentiation.

PCR amplification of gene fragments.

Oligonucleotide primers (Sigma-Genosys or Invitrogen) were designed for the 16S rRNA, cpn60, and agrD genes based on gene sequences available for S. intermedius in GenBank (accession numbers Z26897, AF019773, AY965912, and AF346723), and pta primers were designed based on the S. intermedius pta nucleotide sequence (unpublished data). Oligonucleotide sequences specific for the tuf and mecA genes were designed in previous studies (21, 31). The oligonucleotide sequences and predicted PCR product sizes for specified gene fragments were as follows: 16S rRNA (370 bp), 5′-CCT CTT CGG AGG ACA AAG TGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAC CCG GGA ACG TAT TCA CC-3′ (reverse); tuf (500 bp), 5′-CAA TGC CAC AAA CTC G-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCT TCA GCG TAG TCT A-3′ (reverse); cpn60 (550 bp), 5′-GCG ACT GTA CTT GCA CAA GCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAC TGC AAC CGC TGT AAA T G-3′ (reverse); pta (570 bp), 5′-GTG CGT ATC GTA TTA CCA GAA GG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCA GAA CCT TTT GTT GAG AAG C-3′ (reverse); agrD (300 bp), 5′-GGG GTA TTA TTA CAA TCA TTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTG ATG CGA AAA TAA AGG ATT G-3′ (reverse), and 5′-CTC ATG ACT ATT GCA TGC ATC G-3′ (reverse; pigeon isolates only); and mecA (310 bp), 5′-GTA GAA ATG ACT GAA CGT CCG ATAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCA ATT CCA CAT TGT TTC GGT CTA A-3′ (reverse). PCR mixtures for the 16S RNA, tuf, cpn60, pta, and mecA genes included 0.2 μM each primer, 0.025 U/μl Taq polymerase (Promega), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Promega), and 1 μl genomic DNA template in 96-well PCR microplates (Axygen/Thistle Scientific). The thermocycler program for the 16S RNA, tuf, cpn60, and pta genes consisted of an initial denaturation for 2 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation for 1 min at 95°C, annealing for 1 min at 55°C, and an extension for 1 min at 72°C, and a final extension for 7 min at 72°C. The mecA thermocycler program consisted of an initial denaturation for 5 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation for 45 s at 95°C, annealing for 45 s at 52°C, and an extension for 1 min at 72°C, and a final extension for 5 min at 72°C. For agrD amplification, the reaction mixtures included 0.5 μM each primer, 0.02 U/μl Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs [NEB]), 1× ThermoPol Reaction Buffer (NEB), 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Promega), and 1 μl genomic-DNA template. The thermocycler conditions were an initial denaturation for 2 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 15 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 45°C, and extension for 1 min at 72°C, with a final extension for 7 min at 72°C (36). PCR products were purified by incubation with exonuclease I and Antarctic phosphatase (NEB) at 37°C for 15 min, followed by inactivation at 80°C for 15 min.

DNA sequencing.

Sequencing reactions were carried out using 5 μl purified PCR-amplified DNA (approximately 50 to 90 ng) plus 1 μl sequencing primer (3.2 pmol/μl) with the BigDye Terminator v3.0 Ready Reaction cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each sequencing reaction included 25 cycles with denaturation for 30 s at 95°C, annealing for 20 s at 50°C, and extension for 4 min at 60°C. The nucleotide sequence was determined with a 3730 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). For the 16S rRNA, cpn60, tuf, and pta genes, forward and reverse sequencing reactions were carried out with independently amplified PCR products to rule out the possibility of Taq polymerase-generated errors. For agrD, forward and reverse sequencing reactions were carried out from a single PCR product generated with Vent DNA polymerase (NEB), which contains proofreading activity and has a much lower predicted error rate than Taq polymerase.

DNA sequence and molecular evolutionary analyses.

DNA sequences were assembled using BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor software (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html) and the Staden package (35). Nucleotide and amino acid sequences were aligned using AlignX in Vector NTI Advance10 (Invitrogen). Phylogenetic analyses were carried out with MEGA v.3.1 software (23). The neighbor-joining method was applied to construct phylogenetic trees using the Kimura two-parameter model, while the degree of statistical support for the nodes on the minimum evolution tree was evaluated by examining their percent recovery in 1,000 resample trees by the bootstrap test. For estimating events of recombination, RDP software, which includes the programs GENECONV, BOOTSCAN, MAXIMUM χ2, CHIMAERA, and SISTER SCANNING, was used (27). The index of association standardized (IAS) between the different gene loci was calculated using the LIAN program (version 3.1; Department of Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, University of Applied Sciences, Weihenstephan, Germany) (http://adenine.biz.fh-weihenstephan.de/lian_3.1/). The value of the IAS would be expected to be zero for linkage equilibrium when recombination events occur frequently. If the IAS value differs significantly from zero (P < 0.05), recombination should be rare.

eBURST analysis.

Predicted lines of evolutionary descent and clonal complexes in our collection of isolates were identified using the eBURST algorithm (http://eburst.mlst.net). Sequence types (STs) were included in the same group if they shared four of the five gene loci with at least one other ST within the group. Subgroups were defined by the existence of at least three single-locus variants.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank, accession no. EU157195 to EU157715.

RESULTS

Multilocus sequence analysis of S. intermedius.

Overall, 192,482 bp representing 521 sequences from 105 isolates, including 99 isolates phenotypically identified as S. intermedius, 4 isolates of S. pseudintermedius, and the type strains of S. delphini and S. schleiferi subsp. schleiferi, were generated. 16S rRNA gene sequences contained 1.37% variable sites and 7 alleles, tuf sequences contained 2.4% and 9 alleles, cpn60 contained 12.76% and 28 alleles, pta contained 10.98% and 18 alleles, and agrD contained 13.04% polymorphic nucleotide sites and 9 alleles (Table 1). 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis revealed the existence of five ambiguous nucleotide sites characterized by a double peak for a single site in the sequencing trace for eight isolates. A mixed or contaminated template was ruled out by repurification of the strain to a single colony before genomic-DNA isolation, repeat PCR, and sequencing. These data are consistent with the existence of intragenomic 16S rRNA gene polymorphisms, which have been previously observed (6). Phylogenetic reconstructions were carried out using concatenated sequences, which included both possible 16S rRNA alleles to determine if they influenced tree topology, but no significant difference in topology was observed (data not shown). The least common allelic alternative was selected for each strain and used in phylogenetic analysis and assignment of STs. The cpn60 sequences for S. delphini ATCC 49171 and S. schleiferi ATCC 43808 (GenBank accession numbers AF053571 and AF033622) and the agrD sequence for S. intermedius NCTC 11048 (GenBank accession number AF346723) were obtained from the NCBI GenBank nucleotide database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

TABLE 1.

Summary of nucleotide sequence variation for the SIG and for the S. pseudintermedius, S. delphini, and S. intermedius phylotypes

| Gene locus | Group | No. of strains | Total length of sequence (bp) | No. of variable sites (%) | No. of singleton variable sites (%) | No. of allelesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | SIG | 104 | 366 | 5 (1.37) | 2 (0.55) | 7 |

| S. pseudintermedius. | 89 | 2 (0.55) | 1 (0.27) | 3 | ||

| S. delphini | 11 | 3 (0.82) | 1 (0.27) | 5 | ||

| S. intermedius | 4 | 1 (0.27) | 0 (0.00) | 1 | ||

| tuf | SIG | 104 | 417 | 10 (2.40) | 4 (0.96) | 9 |

| S. pseudintermedius | 89 | 3 (0.72) | 2 (0.48) | 4 | ||

| S. delphini | 11 | 3 (0.72) | 2 (0.48) | 4 | ||

| S. intermedius | 4 | 1 (0.24) | 1 (0.24) | 2 | ||

| cpn60 | SIG | 104 | 431 | 55 (12.76) | 9 (2.10) | 28 |

| S. pseudintermedius | 89 | 14 (3.25) | 3 (0.70) | 20 | ||

| S. delphini | 11 | 19 (4.41) | 8 (1.86) | 7 | ||

| S. intermedius | 4 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 | ||

| pta | SIG | 104 | 492 | 54 (10.98) | 11 (2.24) | 18 |

| S. pseudintermedius | 89 | 12 (2.44) | 6 (1.22) | 10 | ||

| S. delphini | 11 | 8 (1.63) | 7 (1.42) | 6 | ||

| S. intermedius | 4 | 4 (0.81) | 4 (0.81) | 2 | ||

| agrD | SIG | 104 | 138 | 18 (13.04) | 4 (2.90) | 9 |

| S. pseudintermedius | 89 | 6 (4.35) | 0 (0.00) | 4 | ||

| S. delphini | 11 | 11 (7.97) | 5 (3.62) | 5 | ||

| S. intermedius | 4 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 |

One 16S rRNA allele is shared by S. pseudintermedius and S. delphini and one by S. delphini and S. intermedius. S. pseudintermedius and S. delphini share one allele for the tuf gene and one for agrD.

Phylogenetic analysis reveals that S. pseudintermedius and not S. intermedius is the common canine pyoderma pathogen.

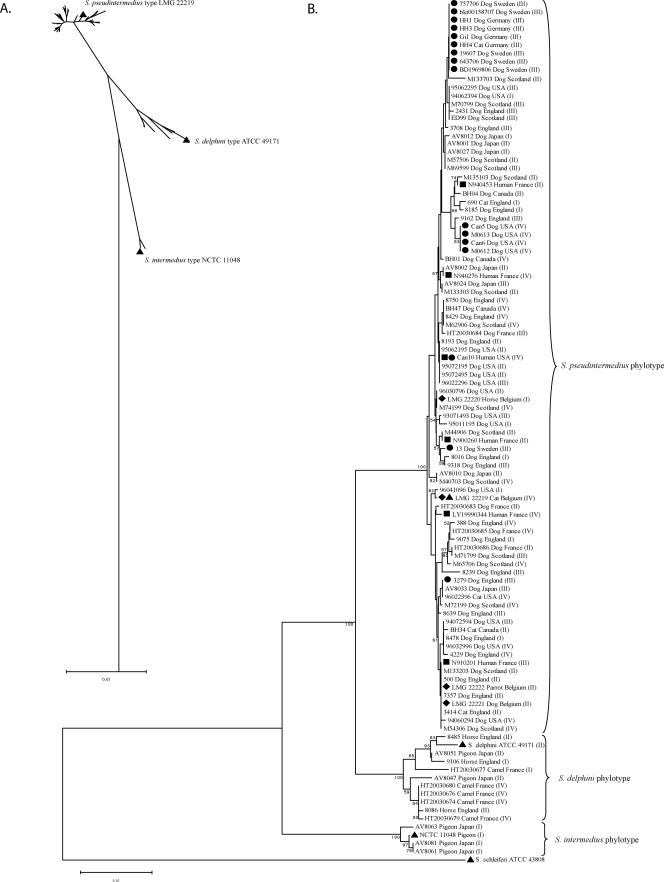

Neighbor-joining trees were constructed with MEGA3.1 using the Kimura two-parameter model combined with 1,000 resample trees by the bootstrap test using sequences for each individual locus (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Trees constructed with sequences from each housekeeping locus appeared to be generally in good agreement, indicating a robust phylogenetic signal (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In contrast, the topology of the tree generated with the agrD nucleotide sequence was very different from those of trees generated with the other gene sequences, suggesting that recombination may have interfered with the phylogenetic signal (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Accordingly, agrD sequences were not included in the concatenated sequence analysis (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analysis based on the concatenated sequence data indicated the existence of three major phylotypes with strong confidence (bootstrap values, 100% for each node) (Fig. 1). For comparison, phylogenetic-tree reconstruction was also carried out using the Minimum Evolution and unweighted-pair group method using average linkages approaches, and each resulted in a topology that was cognate with the neighbor-joining trees (data not shown). The type strain of S. intermedius (NCTC 11048) belongs to a small phylogenetically distinct group of pigeon isolates that is not representative of the majority of isolates phenotypically identified as S. intermedius. All canine isolates (n = 75) belong to a single phylotype, which includes the four isolates previously identified as the novel species S. pseudintermedius (7) (Fig. 1). The S. pseudintermedius isolates were distributed among the canine isolates in the phylogenetic tree, including two strains, S. pseudintermedius LMG 22221 and S. pseudintermedius LMG 22222, that were genetically indistinguishable from canine isolates belonging to one of the most populous nodes (Fig. 1). These data indicate that the recently described S. pseudintermedius and not S. intermedius is the common canine pyoderma pathogen.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree constructed by the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates of concatenated 16S rRNA gene, tuf, cpn60, and pta sequences. (A) Radiating tree indicating the three major phylotypes, with species type strains indicated by triangles. (B) Branch style tree indicating the host and geographic origins of all isolates. Methicillin-resistant, mecA-positive isolates (dots); human isolates (squares); previously identified S. pseudintermedius isolates (diamonds); and species-type isolates (triangles) are indicated, along with the agr type in roman numerals in parentheses. Bootstrap values over 50% are indicated.

The third major phylotype was represented by isolates from horse, camel, and pigeon hosts and included the S. delphini type strain, ATCC 49171, isolated from a dolphin (39), suggesting that S. delphini may be commonly misidentified as S. intermedius. Taken together, these data indicate the existence of at least three closely related but distinct species among isolates that are identified as S. intermedius by phenotypic methods and that together could be described as the SIG.

S. pseudintermedius has a largely clonal population structure.

As mentioned above, trees constructed with sequences from each housekeeping locus appeared to be generally in good agreement, suggesting that recombination has not played a major role in the evolution of these genes and consistent with a clonal population structure (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To further investigate the population structure, we calculated the degrees of linkage disequilibrium within the whole SIG and within the S. pseudintermedius and S. delphini species (Table 2). The value of the IAS for the SIG as a whole was 0.1510 (P < 0.001), and for the S. pseudintermedius and S. delphini species it was 0.0877 (P < 0.001) and 0.3699 (P < 0.001), respectively, indicating that there is linkage disequilibrium within each group tested (Table 2). In addition, the RDP2 program was used to search for evidence of recombination among the selected gene loci (27). For each locus, none of the recombination detection methods, GENECONV, BOOTSCAN, MAXIMUM χ2, CHIMAERA, and SISTER SCANNING, detected any evidence for recombinant sequences among the isolates examined (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate a largely clonal population structure for the SIG as a whole and for the S. pseudintermedius and S. delphini species.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of linkage disequilibrium by calculation of IAS for the SIG and for the S. pseudintermedius and S. delphini phylotypes

| Group selection | IAS |

P valuea

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Parametric | Monte Carlo (100 iterations) | ||

| SIG | 0.151 | 0.0000 | 0.001 |

| S. pseudintermedius | 0.0877 | 0.0000 | 0.001 |

| S. delphini | 0.3699 | 0.0000 | 0.001 |

| S. intermediusb | ND | ND | ND |

The value of the IAS would be expected to be zero for linkage equilibrium when recombination events occur frequently. If the IAS (P < 0.05) value differs significantly from zero, recombination should be rare.

The small number of isolates of the S. intermedius phylotype precluded carrying out this analysis. ND, not done.

S. pseudintermedius clonal diversity and intercontinental distribution.

We identified the number of alleles at each of the five gene loci and defined unique complements of alleles as STs (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). S. pseudintermedius is characterized by the existence of 61 different STs among 89 isolates examined, indicating considerable clonal diversity within the species (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The limited number of S. pseudintermedius isolates that were from human and noncanine animal sources commonly shared identical or closely related genotypes with S. pseudintermedius canine commensal strains, consistent with zoonotic transfer from dogs (Fig. 1). In addition, identical or closely related S. pseudintermedius STs were found on different continents, indicating broad geographic dissemination of successful clones (Fig. 1).

Identification and distribution of agr types among the SIG of closely related species.

DNA sequencing of the agrD locus revealed the presence of four predicted AIP variants among the strains examined, including a novel fourth variant that has not been described previously (designated type IV) which is specific to 27% of all strains (Table 3). The AIP variants may correspond to distinct agr interference groups (8, 30, 36, 42). All staphylococcal species examined to date have been shown to encode AIP peptides that are unique to each species. In contrast, the three closely related species examined in the current study had AIP peptide variants in common, suggesting the existence of a conserved agr quorum-sensing system. All four AIP variants (I to IV) were encoded among the S. pseudintermedius isolates; AIP variants I, II, and IV were identified among the S. delphini group of isolates; and the S. intermedius type strain and related pigeon isolates all encoded AIP type I (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 3.

Amino acid sequences of the predicted agrD-encoded AIPs identified among the strains examined

| agr type (AIP) | Amino acid sequence | No. of strains (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | RIPTSTGFF | 16 (15) |

| II | RIPISTGFF | 31 (30) |

| III | KIPTSTGFF | 29 (28) |

| IVa | KYPTSTGFF | 28 (27) |

Novel AIP variant identified in the current study.

A lack of clonal association of agrD alleles was observed, and several isolates shared identical genotypes by 16S rRNA gene, tuf, cpn60, and pta but encoded different AIP variants (Fig. 1). Further, the agr gene tree topology was markedly different from those of the other gene trees. These data and the lack of recombination breakpoints identified within agrD sequences using the RDP2 suite of programs suggest that assortive (whole-gene) recombination may have contributed to the distribution of agr alleles. There was no identifiable association between agr type and host, clinical, or geographic origin.

MRSP strains have evolved by multiple mecA gene acquisitions by different clones.

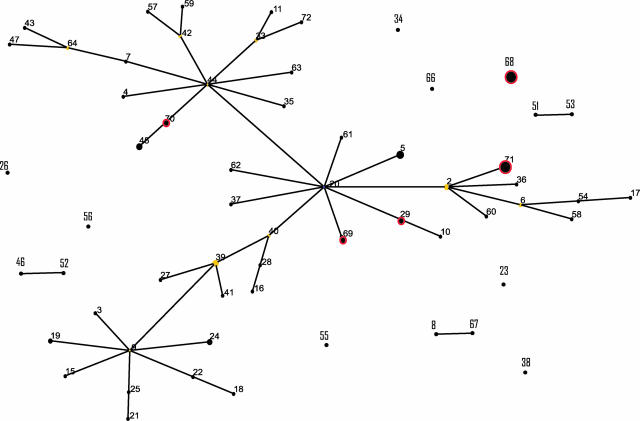

The presence of the mecA gene in 16 of 105 isolates was detected by PCR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Sequencing of the mecA gene in representative isolates revealed a high degree of homology with mecA of Staphylococcus aureus origin (95 to 100%; data not shown). These strains had previously been identified as MRSI in the centers where they were isolated and had oxacillin MIC levels of >256 μg/ml for all strains except one (strain 13), which had an MIC of 0.75 μg/ml. All strains previously identified as MRSI belonged to the S. pseudintermedius phylotype and are therefore reclassified as MRSP. MRSP genotypes are distributed widely across the diversity identified within the S. pseudintermedius phylogenetic tree, including one isolate, 3279, that is genetically indistinguishable from methicillin-sensitive isolates (ST29), suggesting horizontal transfer of the mecA gene (Fig. 1). The existence of multiple MRSP clones is supported by eBURST analysis, which shows that MRSP isolates belong to five distinct STs (ST29, ST68, ST69, ST70, and ST71) that differ at two to four of the five loci examined, strongly suggesting that they do not share a very recent ancestor (Fig. 2). Taken together, these data suggest that the mecA gene has been acquired multiple times by different S. pseudintermedius strains. Of note, 9 out of 10 MRSP isolates from five different centers in Sweden and Germany belong to ST71, indicating that a common clone may predominate in North and Central Europe (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). There was no sharing of STs among European and U.S. MRSP isolates (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 2.

Schematic diagram of the clonal relatedness of S. pseudintermedius STs predicted by eBURST analysis. Each ST is represented by a black dot, the size of which is proportional to the number of isolates of that ST. Blue and yellow dots denote the predicted group founder and subgroup founders, respectively. Single-locus variants are linked by lines. STs that include MRSP strains are indicated by red circles. STs that are not linked by branches to other STs do not share at least four identical alleles with any other ST.

DISCUSSION

Hajek and colleagues first described the novel coagulase-positive species S. intermedius, which was isolated from pigeons, dogs, minks, and horses in 1976 (16). The type strain, NCTC 11048 (also known as ATCC 29663, CCM 5739, or LMG 13351), isolated from a pigeon, has typically been used to represent S. intermedius in species differentiation studies (7, 11, 13, 24, 25). Very recently, Sasaki and colleagues carried out nucleotide sequence analysis of the sodA and hsp60 (cpn60) genes and identified S. intermedius, S. pseudintermedius, and S. delphini among isolates from Japan phenotypically identified as S. intermedius (33). Here, we show that isolates obtained from 10 different countries on three continents have a population structure that is consistent with that identified among Japanese isolates by Sasaki et al. (33). Our data indicate that the pigeon isolate represents a distinct taxon that is not representative of the majority of isolates commonly identified as S. intermedius. All canine isolates examined (n = 75) belong to the phylotype that includes four isolates of the recently described S. pseudintermedius species, including the type strain (7). Importantly, two S. pseudintermedius strains (ST5) were genetically indistinguishable from canine isolates phenotypically identified as S. intermedius. These data indicate that the newly described S. pseudintermedius species and not S. intermedius is the common cause of canine pyoderma. S. pseudintermedius is characterized by over 60 different STs identified among the 89 isolates examined, revealing considerable clonal diversity within the species. Identical and closely related STs were identified in several countries on different continents, indicating global dissemination of the most successful clones. The clonal diversity and broad geographic distribution of S. pseudintermedius suggests that it has coevolved with its canine host for a long time in evolutionary terms and possibly since the evolution of dogs between 40 and 50 million years ago (20, 41). STs of S. pseudintermedius isolates infecting humans are identical or closely related to commensal isolates of dogs, suggesting that human infections are due to zoonotic transmission from a canine host. Indeed, transmission of S. pseudintermedius has been shown to occur frequently between dogs affected by deep pyoderma and their owners (14).

The third major phylotype found among the isolates previously identified as S. intermedius was associated with several different host species, including horse, camel, and pigeon, and was phylogenetically aligned with the S. delphini type strain isolated from a dolphin (39). A previous DNA-DNA hybridization analysis confirmed that the S. delphini type strain represented a distinct species compared to the recently described S. pseudintermedius and the S. intermedius type strain (7). Taken together, these data suggest that S. delphini is commonly misidentified as S. intermedius and may be more clinically important than was previously thought. In fact, very few studies have reported the identification of S. delphini strains since the original description of the species, but one study in Norway isolated S. delphini from a case of bovine mastitis, extending the broad host range observed in the current study (4). Of note, Sasaki et al. indicated that more than one species may exist among isolates genetically allied with S. delphini (33).

The accessory gene regulator (agr) is conserved throughout the staphylococci but has diverged along lines that appear to parallel speciation within the genus (8, 42). This divergence has given rise to a novel type of interstrain and interspecies cross-inhibition that likely represents an essential aspect of staphylococcal biology and may be a predominant feature of the evolutionary forces that have driven it. In order to further investigate the diversity of SIG populations, we examined the diversity of the agrD locus, which encodes the AIP (8, 20, 36, 42). Sung et al. identified three agrD alleles corresponding to agr specificity groups encoding different AIP variants among 20 strains of S. intermedius isolated from dogs in a single veterinary hospital in the United Kingdom (36) and demonstrated biological activity for two of them. Here, we identified the same three predicted AIPs, in addition to a novel fourth AIP, which was encoded by approximately 27% of strains (Table 3). Of note, all of the predicted AIP variants of the SIG contain a serine in place of the conserved cysteine found in the AIPs of the other staphylococcal species analyzed to date, resulting in a lactone rather than a thiolactone ring (20). S. aureus populations are also divided into four distinct groups based on agr allelic variation. Interference in virulence gene expression caused by different S. aureus agr groups has been suggested to be a mechanism for isolating bacterial populations and a fundamental basis for subdividing the species (42). All previously examined staphylococcal species encode AIPs that are unique to each species (8). However, we found that agr alleles were shared among the three closely related species of the SIG, indicating that a common quorum-sensing capacity has been maintained despite species differentiation in largely distinct ecological niches.

A previous study of agr evolution in S. aureus reported that genotypes were not associated with more than one agr type, indicating that agr radiation preceded clonal diversification and that recombination has played a very limited role in the distribution of agr diversity (42). The study concluded that the species was phylogenetically structured according to agr group (42). More recently, Robinson et al. provided evidence that the S. aureus species could be divided into two subgroups that both contain multiple clonal complexes and agr groups (30). The authors proposed that recombination events had resulted in the sharing of agr groups between the two subspecies but concluded that recombination of agr has not occurred very frequently within S. aureus populations, as agr and clone tree topologies within the two subspecies were in agreement (30). In contrast, the association of different agr alleles with strains of S. pseudintermedius of identical genotype identified in the current study suggests that assortive recombination has frequently contributed to the distribution of agr alleles among S. pseudintermedius populations. The markedly different topology of the phylogenetic tree constructed with agrD sequences compared to trees based on the other four gene loci is consistent with this theory (Fig. 1). Overall, we have found that S. pseudintermedius has a largely clonal population structure, but recombination appears to have played an important role in the distribution of agr alleles within the S. pseudintermedius species and the SIG as a whole. The sharing of agr alleles between different species of staphylococci has not been previously observed. This discovery indicates that agr differentiation has not occurred strictly along lines that parallel speciation. The lack of an association between agr type and SIG species, host, disease, and clinical or geographic origin identified in the current study leads to the question of what selective pressure is driving agr diversification. The basis for agr diversity and the importance of its biological activity in the SIG remain to be elucidated.

Recently, an increasing number of episodes of S. intermedius infections that were refractory to treatment with methicillin have been reported (15, 22, 32, 44). Here, we found that the methicillin-resistant SIG strains examined are all classified as S. pseudintermedius and have evolved by multiple acquisitions of the mecA gene by different S. pseudintermedius clones. Of note, a common clone was identified among isolates from five different centers in Sweden and Germany, indicating the existence of a widespread successful clone in Northern and Central Europe. MRSP clones were not shared between Europe and North America, indicating geographic restriction and probably reflecting the very recent emergence of methicillin-resistant strains. The identification of the common methicillin-resistant clones in the current study means that surveillance can be carried out to monitor MRSP clonal dissemination and strategies for the control of MRSP infections can be targeted to the most widespread clones.

Taken together, these data have resolved the population genetic structure of the SIG, resulting in broad new insights into the ancient and recent evolution of this important group of animal pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to U. Andersson, A. Chow, M. Bes, G. Bohach, E. De Graef, J. Freney, K. Futagawa-Saito, F. Haesebrouck, J. Harris, L. Hume, and S. Weese for provision of isolates; Mairi Mitchell, Nuria Barquero, and Charlotte Baker for technical assistance; and A. Robinson for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 September 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarestrup, F. M. 2001. Comparative ribotyping of Staphylococcus intermedius isolated from members of the Canoidea gives possible evidence for host-specificity and co-evolution of bacteria and hosts. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1343-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartual, S. G., H. Seifert, C. Hippler, M. A. Luzon, H. Wisplinghoff, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 2005. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for characterization of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4382-4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bes, M., L. Saidi Slim, F. Becharnia, H. Meugnier, F. Vandenesch, J. Etienne, and J. Freney. 2002. Population diversity of Staphylococcus intermedius isolates from various host species: typing by 16S-23S intergenic ribosomal DNA spacer polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2275-2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjorland, J., T. Steinum, B. Kvitle, S. Waage, M. Sunde, and E. Heir. 2005. Widespread distribution of disinfectant resistance genes among staphylococci of bovine and caprine origin in Norway. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4363-4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chesneau, O., A. Morvan, S. Aubert, and N. el Solh. 2000. The value of rRNA gene restriction site polymorphism analysis for delineating taxa in the genus Staphylococcus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:689-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coenye, T., and P. Vandamme. 2003. Intragenomic heterogeneity between multiple 16S ribosomal RNA operons in sequenced bacterial genomes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 228:45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devriese, L. A., M. Vancanneyt, M. Baele, M. Vaneechoutte, E. De Graef, C. Snauwaert, I. Cleenwerck, P. Dawyndt, J. Swings, A. Decostere, and F. Haesebrouck. 2005. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius sp. nov., a coagulase-positive species from animals. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:1569-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dufour, P., S. Jarraud, F. Vandenesch, T. Greenland, R. P. Novick, M. Bes, J. Etienne, and G. Lina. 2002. High genetic variability of the agr locus in Staphylococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 184:1180-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reference deleted.

- 10.Feil, E. J., J. E. Cooper, H. Grundmann, D. A. Robinson, M. C. Enright, T. Berendt, S. J. Peacock, J. M. Smith, M. Murphy, B. G. Spratt, C. E. Moore, and N. P. Day. 2003. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus? J. Bacteriol. 185:3307-3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freney, J., Y. Brun, M. Bes, H. Meugnier, F. Grimont, P. A. D. Grimont, C. Nervi, and J. Fleurette. 1988. Staphylococcus lugdunensis sp. nov. and Staphylococcus schleiferi sp. nov., two species from human clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38:168-172. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Futagawa-Saito, K., T. Sugiyama, S. Karube, N. Sakurai, W. Ba-Thein, and T. Fukuyasu. 2004. Prevalence and characterization of leukotoxin-producing Staphylococcus intermedius in isolates from dogs and pigeons. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5324-5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goh, S. H., Z. Santucci, W. E. Kloos, M. Faltyn, C. G. George, D. Driedger, and S. M. Hemmingsen. 1997. Identification of Staphylococcus species and subspecies by the chaperonin 60 gene identification method and reverse checkerboard hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3116-3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guardabassi, L., M. E. Loeber, and A. Jacobson. 2004. Transmission of multiple antimicrobial-resistant Staphylococcus intermedius between dogs affected by deep pyoderma and their owners. Vet. Microbiol. 98:23-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guardabassi, L., S. Schwarz, and D. H. Lloyd. 2004. Pet animals as reservoirs of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:321-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajek, V. 1976. Staphylococcus intermedius, a new species isolated from animals. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 26:401-408. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hesselbarth, J., and S. Schwarz. 1995. Comparative ribotyping of Staphylococcus intermedius from dogs, pigeons, horses and mink. Vet. Microbiol. 45:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hesselbarth, J., W. Witte, C. Cuny, R. Rohde, and G. Amtsberg. 1994. Characterization of Staphylococcus intermedius from healthy dogs and cases of superficial pyoderma by DNA restriction endonuclease patterns. Vet. Microbiol. 41:259-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill, P. B., A. Lo, C. A. Eden, S. Huntley, V. Morey, S. Ramsey, C. Richardson, D. J. Smith, C. Sutton, M. D. Taylor, E. Thorpe, R. Tidmarsh, and V. Williams. 2006. Survey of the prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of dermatological conditions in small animals in general practice. Vet. Rec. 158:533-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji, G., W. Pei, L. Zhang, R. Qiu, J. Lin, Y. Benito, G. Lina, and R. P. Novick. 2005. Staphylococcus intermedius produces a functional agr autoinducing peptide containing a cyclic lactone. J. Bacteriol. 187:3139-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonas, D., M. Speck, F. D. Daschner, and H. Grundmann. 2002. Rapid PCR-based identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from screening swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1821-1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kania, S. A., N. L. Williamson, L. A. Frank, R. P. Wilkes, R. D. Jones, and D. A. Bemis. 2004. Methicillin resistance of staphylococci isolated from the skin of dogs with pyoderma. Am. J. Vet. Res. 65:1265-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwok, A. Y., and A. W. Chow. 2003. Phylogenetic study of Staphylococcus and Macrococcus species based on partial hsp60 gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:87-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwok, A. Y., S. C. Su, R. P. Reynolds, S. J. Bay, Y. Av-Gay, N. J. Dovichi, and A. W. Chow. 1999. Species identification and phylogenetic relationships based on partial HSP60 gene sequences within the genus Staphylococcus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1181-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahoudeau, I., X. Delabranche, G. Prevost, H. Monteil, and Y. Piemont. 1997. Frequency of isolation of Staphylococcus intermedius from humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2153-2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin, D. P., C. Williamson, and D. Posada. 2005. RDP2: recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 21:260-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer, S. A., and K. H. Schleifer. 1978. Deoxyribonucleic acid reassociation in the classification of coagulase-positive staphylococci. Arch. Microbiol. 117:183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pottumarthy, S., J. M. Schapiro, J. L. Prentice, Y. B. Houze, S. R. Swanzy, F. C. Fang, and B. T. Cookson. 2004. Clinical isolates of Staphylococcus intermedius masquerading as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5881-5884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson, D. A., A. B. Monk, J. E. Cooper, E. J. Feil, and M. C. Enright. 2005. Evolutionary genetics of the accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187:8312-8321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakai, H., G. W. Procop, N. Kobayashi, D. Togawa, D. A. Wilson, L. Borden, V. Krebs, and T. W. Bauer. 2004. Simultaneous detection of Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci in positive blood cultures by real-time PCR with two fluorescence resonance energy transfer probe sets. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:5739-5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki, T., K. Kikuchi, Y. Tanaka, N. Takahashi, S. Kamata, and K. Hiramatsu. 2007. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in a veterinary teaching hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1118-1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki, T., K. Kikuchi, Y. Tanaka, N. Takahashi, S. Kamata, and K. Hiramatsu. 2007. Reclassification of phenotypically identified Staphylococcus intermedius strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2770-2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reference deleted.

- 35.Staden, R. 1996. The Staden sequence analysis package. Mol. Biotechnol. 5:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sung, J. M., P. D. Chantler, and D. H. Lloyd. 2006. Accessory gene regulator locus of Staphylococcus intermedius. Infect. Immun. 74:2947-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanner, M. A., C. L. Everett, and D. C. Youvan. 2000. Molecular phylogenetic evidence for noninvasive zoonotic transmission of Staphylococcus intermedius from a canine pet to a human. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1628-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Hoovels, L., A. Vankeerberghen, A. Boel, K. Van Vaerenbergh, and H. De Beenhouwer. 2006. First case of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius infection in a human. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4609-4612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varaldo, P. E., R. Kilpper-Balz, F. Biavasco, G. Satta, and K. H. Schleifer. 1988. Staphylococcus delphini sp. nov., a coagulase-positive species isolated from dolphins. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38:436-439. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakita, Y., A. Shimizu, V. Hajek, J. Kawano, and K. Yamashita. 2002. Characterization of Staphylococcus intermedius from pigeons, dogs, foxes, mink, and horses by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 64:237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wayne, R. K. 1993. Molecular evolution of the dog family. Trends Genet. 9:218-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright, J. S., III, K. E. Traber, R. Corrigan, S. A. Benson, J. M. Musser, and R. P. Novick. 2005. The agr radiation: an early event in the evolution of staphylococci. J. Bacteriol. 187:5585-5594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zadoks, R. N., Y. H. Schukken, and M. Wiedmann. 2005. Multilocus sequence typing of Streptococcus uberis provides sensitive and epidemiologically relevant subtype information and reveals positive selection in the virulence gene pauA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2407-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zubeir, I. E., T. Kanbar, J. Alber, C. Lammler, O. Akineden, R. Weiss, and M. Zschock. 2007. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of methicillin/oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus intermedius isolated from clinical specimens during routine veterinary microbiological examinations. Vet. Microbiol. 121:170-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.