Abstract

Oxygen profoundly affects the composition of oral biofilms. Recently, we showed that exposure of Streptococcus mutans to oxygen strongly inhibits biofilm formation and alters cell surface biogenesis. To begin to dissect the underlying mechanisms by which oxygen affects known virulence traits of S. mutans, transcription profiling was used to show that roughly 5% of the genes of this organism are differentially expressed in response to aeration. Among the most profoundly upregulated genes were autolysis-related genes and those that encode bacteriocins, the ClpB protease chaperone subunit, pyruvate dehydrogenase, the tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes, NADH oxidase enzymes, and certain carbohydrate transporters and catabolic pathways. Consistent with our observation that the ability of S. mutans to form biofilms was severely impaired by oxygen exposure, transcription of the gtfB gene, which encodes one of the primary enzymes involved in the production of water-insoluble, adhesive glucan exopolysaccharides, was down-regulated in cells growing aerobically. Further investigation revealed that transcription of gtfB, but not gtfC, was responsive to oxygen and that aeration causes major changes in the amount and degree of cell association of the Gtf enzymes. Moreover, inactivation of the VicK sensor kinase affected the expression and localization the GtfB and GtfC enzymes. This study provides novel insights into the complex transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulatory networks used by S. mutans to modulate virulence gene expression and exopolysaccharide production in response to changes in oxygen availability.

Of the hundreds of bacterial species that colonize and persist in the mouth, Streptococcus mutans is the organism that is most effective at causing dental caries. The abilities of this organism to form biofilms, to generate acid, and to tolerate environmental stresses are critical to its virulence (10, 11, 24, 25). All organisms in oral biofilms are exposed to rapid variations in the amount and type of metabolizable energy sources, to rapid changes in environmental pH, and to a considerable spectrum of local oxidation-reduction potentials. All of these environmental variables are known to have a profound impact on bacterial gene expression and have been unequivocally shown to be the factors that have the greatest impact on the microbial composition and biological activities of oral biofilms (10, 11, 24, 25). It is becoming generally accepted that the ability of S. mutans to adapt to comparatively hostile environments is a primary mechanism by which this organism emerges as a dominant member of cariogenic dental biofilms (11, 17, 40, 41). While the molecular mechanisms underlying the control of carbohydrate acquisition, acid production, and adaptation to low pH by S. mutans have been the focus of a substantial number of studies, the role of oxygen in fundamental aspects of gene regulation and physiologic homeostasis is poorly understood.

Oxygen is required by many oral organisms for respiration and energy generation. Organisms that initially colonize the surfaces of the mouth are exposed to levels of oxygen approaching those found in air or air-saturated water (30). Mature oral biofilms, however, support a wide range of aerobes, facultative anaerobes, and obligately anaerobic bacteria, indicating that limited diffusion and rapid metabolism of oxygen in mature biofilms combine to substantially reduce oxygen tension and lower the redox potential of dental plaque (22). In fact, oxygen tension in the oral cavity has been estimated to range from 5 to 27 mm Hg (34), while estimates of the redox potential (Eh) of early biofilms (+294 mV) is much higher than that (−141 mV) measured in mature biofilms (22). Although oral streptococci do not possess a full electron transport chain and cannot carry out oxidative phosphorylation, these organisms maintain a high capacity to metabolize oxygen, primarily through NADH oxidase enzymes (19, 30).

We have recently demonstrated that the ability of S. mutans to form biofilms, an essential virulence attribute of this organism, was dramatically reduced when cells were cultivated in the presence of oxygen (2). This finding alone has substantial implications, since it reveals that S. mutans cells that initially colonize a surface in the oral cavity may display much different behaviors than when the organisms are growing in a mature biofilm with reduced oxygen availability or redox potential. We also demonstrated that the behavior of cells in the presence of oxygen is largely influenced by the VicK sensor kinase of a CovRS-like two-component system (TCS) and by the AtlA autolysin pathway, which plays a major role in modulating cell surface composition (2). It was particularly interesting that inactivation of the gene for AtlA or VicK restored the capacity of S. mutans to form biofilms in the presence of oxygen (2). Collectively, these observations indicate that oxygen is a key environmental factor that strongly influences cell envelope composition and biofilm formation and that S. mutans has evolved specialized pathways to regulate gene expression, protein secretion, and cell surface biogenesis in response to redox (2). The purpose of this study was to identify genes differentially expressed in response to oxygen availability to define further the network of genes involved in virulence expression, particularly biofilm formation, by S. mutans. On the basis of previous work (2) and the gene expression profiling data described herein, we subsequently reveal important aspects of posttranscriptional control of the exopolysaccharide machinery that may have substantial implications for how S. mutans regulates biofilm maturation in vivo in response to oxygen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli DH10B was grown in Luria broth, and S. mutans UA159 and its derivatives were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco). For selection of antibiotic-resistant colonies after genetic transformation, ampicillin (100 μg ml−1 for E. coli) and kanamycin (50 μg ml−1 for E. coli or 1 mg ml−1 for S. mutans) were added to the media as needed. For aerobic growth, an overnight culture of S. mutans UA159 was diluted 1:50 into a 250-ml conical flask containing 50 ml of BHI broth (Difco) and cultures were grown on a rotary shaker (150 rpm) at 37°C until the absorbance at 600 nm reached 0.4 (mid-exponential phase). For anaerobic growth, cultures were similarly diluted and incubated without agitation in a BBL GasPak Plus anaerobic system (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to the same optical density. Under these conditions, no significant differences in growth rate were noted between aerated cells and cells cultures anaerobically (2).

Microarray experiments.

Total RNA was isolated from 10 ml of exponential-phase (optical density at 600 nm = 0.4) cultures as described previously (4). All RNA samples were DNase I treated and purified with the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). RNA concentration was estimated spectrophotometrically in triplicate. Reverse transcription (RT) and microarray reactions were performed with 5.0 μg of total bacterial RNA as described elsewhere (1, 49). S. mutans UA159 microarrays were provided by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR), and each slide contained four copies of 1960 corresponding to open reading frames in the genome. For each microarray slide, a separate RNA preparation from a separate culture was used, so a total of eight slides (four for each condition) were used in this study. Hybridizations were performed in a Maui hybridization chamber (BioMicro Systems, Salt Lake City, UT). Additional details regarding the array protocols used are available at http://pfgrc.tigr.org/protocols/protocols.shtml.

Data analysis.

After the slides were scanned, the resulting images were analyzed by TIGR Spotfinder software (http://www.tigr.org/software/) and further normalized with LOWESS and iterative log mean centering with default settings, followed by in-slide replicate analysis with the TIGR microarray data analysis system (MIDAS; http://www.tigr.org/software/). Statistical analysis was carried out with BRB array tools (http://linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools.html/) with a cutoff P value of 0.001.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed on a subset of the genes to validate the microarray data as described previously (4, 5) and to measure the levels of the gtfB and gtfC mRNAs in the wild-type and vicK-NP strains (Table 1). The gene-specific primers (see Table 2) used in all real-time PCR experiments were designed with Beacon Designer 4.0 software (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA). Standard curves for each gene were prepared as described elsewhere (55).

TABLE 1.

The S. mutans strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| UA159 | Wild type | |

| TW54 | UA159::PgtfB-cat | This study |

| TW55 | UA159::PgtfC-cat | This study |

| vicK-NP | ΔvicK::NPKmr | 2 |

TABLE 2.

Primers used for amplification of putative promoters for cat fusions and for real-time PCR in this study

| Application and name | Sequence | Promoter or amplicon | Primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification of putative promoters | ||||

| PgtfB-5 | ATGGATCCGACAATTGTGGTGGGTAC | PgtfB | PgtfB-3 | CGCTGCAGCTTGTCCATTAGGAACCTCC |

| PgtfC-5 | GTGAATTCGATGCTAACTCTGGAGAACG | PgtfC | PgtfC-3 | GAGGATCCAAAAATAGTTAGAGTTAGTG |

| Real-time RT-PCR | ||||

| gtfB-sense | AGCAATGCAGCCATCTACAAAT | gtfB | gtfB-antisense | ACGAACTTTGCCGTTATTGTCA |

| gtfC-sense | GGTTTAACGTCAAAATTAGCTGTATTAGC | gtfC | gtfC-antisense | CTCAACCAACCGCCACTGTT |

| SMU.150-sense | GGAAGGTATCGGGTGGAGAAGC | SMU.150 | SMU.150-antisense | GAGTCGCACCTGCCAGTCC |

| SMU.299-sense | GGAGCTAATGGCTATGCTTACCG | SMU.299 | SMU.299-antisense | GCACCTGAAGCCCAGCTATTTAC |

| SMU.423-sense | CAACTGTTGAGGGTGGTGGTATG | SMU.423 | SMU.423-antisense | AAGCCGCTCCAGATACTGTACC |

| SMU.575-sense | TTGCCTAAAGCCTTACCGATTCC | SMU.575 | SMU.575-antisense | GCCTGATGGGACAAACATAAAGC |

| SMU.577-sense | TCCATCTACTTCGCAGGTCATTG | SMU.577 | SMU.577-antisense | AATCCCAGCCAGTAAAGAAACCG |

| SMU.879-sense | TTCAGAGCCTGGTTCTTCTTTCC | SMU.879 | SMU.879-antisense | TTCCCAAAGCACTGCCAACTG |

| SMU.1175-sense | GAGAAGTCTCTGGCGGACCTATG | SMU.1175 | SMU.1175-antisense | GCCACTAAGATACCTGCCAATGC |

| SMU.1508-sense | AGGAGAGATGTCTGTTGAGAAGC | SMU.1508 | SMU.1508-antisense | AACGGTTCACCTCCAGTAACAC |

| SMU.1609-sense | TGCAGCCTCAAAAGAATCCTAGC | SMU.1609 | SMU.1609-antisense | GCAATCGCAAGCCAAAAGAAGAC |

| SMU.1913-sense | TCACAAGAAAGTTCGGCTGCTAC | SMU.1913 | SMU.1913-antisense | CTGCTGGCAAATTCGCTTACTTG |

| SMU.1960-sense | ACTGTAACACGTTGGGCGAAAG | SMU.1960 | SMU.1960-antisense | AGCAGCAAAGGCTTCTTTAGACC |

Preparation of protein fractions from S. mutans.

Various protein fractions were prepared from S. mutans cells that were grown under anaerobic or aerobic conditions. In all cases, cells were harvested from BHI broth cultures at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5, centrifuged, and washed twice with Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris, 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4) (3). Culture supernatant proteins were obtained by passing the supernatant fluid through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and concentrating the proteins 80-fold by precipitation with 10% trichloroacetic acid. Whole-cell lysates for protein analysis were obtained by homogenization with a Bead Beater (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK) in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) boiling buffer (60 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 10% glycerol, 5% SDS) in the presence of glass beads. SDS extraction of surface-associated proteins was done by incubating the cells in 4% SDS for 30 min at room temperature (3). For isolation of the cellular soluble fraction, the supernatant fluid was recovered from cells that had been homogenized in the presence of glass beads (0.1 mm, 2 min) in 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The remaining pellet was resuspended in SDS boiling buffer and designated the insoluble fraction.

Protein electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Protein preparations were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) through a 3 to 8% Tris-acetate gradient gel (Invitrogen), and the proteins were transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore). Both GtfB and GtfC were detected with a polyclonal rabbit antiserum raised against purified GtfB (1:500 dilution) (52), which shares 75% amino acid identity with GtfC. Peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (KPL) and Sigma FAST (3,3′-diaminobenzidine tablets) were used to disclose antibody reactivity. The anti-GtfB antiserum was a kind gift from William H. Bowen, University of Rochester. The protein concentration of samples was determined by a bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma).

Construction of reporter gene fusions and CAT assays.

To construct a reporter gene fusion for measuring transcription from the promoters of the gtfB and gtfC genes, a 0.2-kbp fragment containing the putative promoter regions and cognate ribosome binding sites (RBS) of each gene was generated by PCR with the primers listed in Table 2. The products were then cloned into BamHI- and PstI-digested plasmid pU1 so as to drive the transcription and translation of a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene (cat) derived from Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pC194 (12). Accurate amplification of PCR products was always confirmed by sequencing. The transcriptional fusions were then released by partial SmaI and HindIII digestions and inserted into EcoRV- and HindIII-digested pBluescript KS(+). The resulting plasmids were then digested with SmaI and HincII, and the DNA fragments with the gene fusions were gel purified and ligated into the integration vector pBGK (50) at the unique SmaI site. The resulting cat fusion was integrated into the gtfA locus of the wild-type strain in single copy to create strains TW54 and TW55, respectively (Table 1). Double-crossover recombination of the reporter gene fusions into the S. mutans chromosome was confirmed by PCR amplification with primers internal to gtfA.

Microarray data accession number.

Microarray data have been deposited at NCBI-GEO (GSE8544).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overview of the effects of oxygen on the transcriptome of S. mutans.

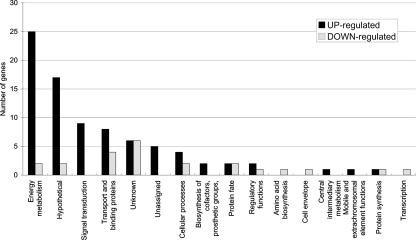

To gain further insights into the molecular basis for the effects of oxygen on biofilm formation by S. mutans (2), we used DNA microarrays to analyze gene expression profiles of cells cultured under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Analysis of microarray data revealed that about 5% of the S. mutans genome displayed altered expression with a P value of ≤0.001 in response to aeration (Fig. 1; Table 3). Substantially more genes were upregulated (n = 83) than downregulated (n = 23) in response to growth in air. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed on a subset of the genes (n = 11) to validate the microarray data (4, 5), and all of the genes displayed the same trend observed in the microarrays (Table 4).

FIG. 1.

Distribution of functions of genes affected by oxygen availability. The 106 genes differentially expressed at P ≤ 0.001 were grouped by functional classification according to the Los Alamos S. mutans genome database (http://www.oralgen.lanl.gov/).

TABLE 3.

Genes differentially expressed under aerobic conditions

| Unique identification no. | Description | Gene(s) | n-Fold difference between aerobic/anaerobic geometric means | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMU.423 | Possible bacteriocin | 41.969 | <1e−07 | |

| SMU.1912c | Hypothetical protein | 33.572 | <1e−07 | |

| SMU.1904c | Hypothetical protein | 32.951 | <1e−07 | |

| SMU.1913c | Hypothetical protein; immunity protein, BlpL like | 33.875 | 0.0000001 | |

| SMU.1903c | Hypothetical protein | 29.797 | <1e−07 | |

| SMU.1425 | ATP-dependent Clp protease, ATP-binding subunit ClpB | clpB | 29.838 | 0.0000006 |

| SMU.150 | Nonlantibiotic mutacin IVA | nlmA | 28.789 | <1e−07 |

| SMU.151 | Nonlantibiotic mutacin IVB | nlmB | 28.011 | <1e−07 |

| SMU.1905c | Hypothetical protein | 26.629 | <1e−07 | |

| SMU.152 | Hypothetical protein | 24.281 | <1e−07 | |

| SMU.1906c | Bacteriocin-related protein | 24.048 | <1e−07 | |

| SMU.1914c | Bacteriocin immunity protein, BlpO like | bip | 17.848 | 0.0000002 |

| SMU.1909c | Hypothetical protein | 14.212 | 0.0000001 | |

| SMU.148 | Alcohol-acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | adhE | 14.326 | 0.0003066 |

| SMU.1424 | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | acoL adhD | 13.986 | 0.0000364 |

| SMU.575c | Murein hydrolase regulator | lrgA | 11.656 | 0.0000492 |

| SMU.2057c | Cadmium efflux ATPase, E1-E2 (heavy-metal-transporting ATPase) | cadA cadD | 9.516 | 0.0000005 |

| SMU.78 | Fructan hydrolase; exo-β-d-fructosidase | fruA | 8.624 | 0.0000002 |

| SMU.1539 | 1,4-α-Glucan branching enzyme | glgB | 8.222 | 0.0000007 |

| SMU.79 | Fructan hydrolase; exo-β-d-fructosidase | fruB | 7.871 | 0.0000032 |

| SMU.1421 | Dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (acetoin dehydrogenase E2 component) | acoC yugF | 7.696 | 0.0000193 |

| SMU.997 | Inorganic ion ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein; possible ferrichrome transport system | fecE yclP | 7.5 | 0.0000001 |

| SMU.2127 | Succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (NAD-dependent aldehyde dehydrogenase) | gabD | 7.463 | 0.0000001 |

| SMU.180 | Oxidoreductase, possible fumarate reductase | 7.063 | 0.00001 | |

| SMU.998 | ABC transporter, ferrichrome-binding protein | fatB yclQ | 6.683 | 0.0000001 |

| SMU.925 | Hypothetical protein | 6.386 | 0.0001306 | |

| SMU.179 | Conserved hypothetical protein (possible oxidoreductase) | 6.287 | 0.0000006 | |

| SMU.1423 | Acetoin dehydrogenase E1 component | acoA | 6.193 | 0.0003586 |

| SMU.402 | Pyruvate formate-lyase | pfl | 6.077 | 0.0000062 |

| SMU.995 | Ferrichrome ABC transporter (permease) | yclN | 5.876 | 0.0000006 |

| SMU.252 | Hypothetical protein | 5.833 | 0.0000004 | |

| SMU.1536 | Glycogen synthase | glgA | 5.513 | 0.0000081 |

| SMU.1117 | H2O-forming NADH oxidase | naoX nox nox-2 | 5.493 | 0.0000507 |

| SMU.996 | ABC transporter, permease protein; possible ferrichrome transport system | yclN | 5.35 | 0.0000091 |

| SMU.577 | Sensor histidine kinase | lytS | 4.969 | 0.0000003 |

| SMU.1535 | Glycogen phosphorylase | glgP | 4.957 | 0.0000031 |

| SMU.1077 | Phosphoglucomutase | pgmA | 4.922 | 0.0000133 |

| SMU.799c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 4.806 | 0.0000024 | |

| SMU.149 | Transposase fragment (IS605/IS200 like) | tpn | 4.794 | 0.000023 |

| SMU.1596 | PTS system, cellobiose-specific IIC component | celB lacE | 4.414 | 0.0000996 |

| SMU.1116c | Hypothetical protein | 4.362 | 0.0001648 | |

| SMU.1957 | Fructose-specific enzyme IID component | levG ptnD | 3.766 | 0.0000435 |

| SMU.1410 | Fumarate reductase | frdC | 3.677 | 0.0000493 |

| SMU.113 | Fructose-1-phosphate kinase | pfk | 3.643 | 0.0009101 |

| SMU.1591 | Catabolite control protein A | ccpA regM | 3.635 | 0.0001455 |

| SMU.1843 | Sucrose-6-phosphate hydrolase | scrB | 3.432 | 0.000015 |

| SMU.500 | Ribosome-associated protein | yfiA | 3.274 | 0.0000558 |

| SMU.1960c | Fructose-specific enzyme IIB component | levE | 3.101 | 0.0000133 |

| SMU.1088 | Thiamine biosynthesis lipoprotein | apbE | 3.098 | 0.0000072 |

| SMU.101 | Sorbose PTS system, IIC component | sorC | 3.048 | 0.0003228 |

| SMU.1956c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.985 | 0.0000254 | |

| SMU.883 | Glucan 1,6-α-glucosidase | dexB | 2.983 | 0.0004012 |

| SMU.1411 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.956 | 0.0001324 | |

| SMU.1958c | Fructose-specific enzyme IIC component | levF | 2.949 | 0.0000213 |

| SMU.1090 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.783 | 0.0000132 | |

| SMU.1495 | Galactose-6-phosphate isomerase | lacB rpiB | 2.61 | 0.0003498 |

| SMU.629 | Superoxide dismutase | sod sodA | 2.601 | 0.0000356 |

| SMU.878 | ABC transporter, sugar-binding protein | msmE | 2.585 | 0.0002202 |

| SMU.765 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, subunit F | ahpF nox1 | 2.566 | 0.0000345 |

| SMU.674 | Phosphotransferase system phosphohistidine-containing protein | pthP | 2.523 | 0.0000325 |

| SMU.882 | Multiple sugar-binding transport ATP-binding protein MsmK | msmK | 2.527 | 0.0002513 |

| SMU.1758c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.471 | 0.0004122 | |

| SMU.1490 | Phospho-β-d-galactosidase | lacG | 2.448 | 0.0002415 |

| SMU.130 | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | acoL adhD | 2.401 | 0.0003251 |

| SMU.879 | ABC transporter, sugar permease protein | msmF | 2.379 | 0.0000512 |

| SMU.1844 | Sucrose operon repressor | scrR | 2.365 | 0.0000449 |

| SMU.131 | Lipoate-protein ligase | lplA | 2.286 | 0.0000561 |

| SMU.1916 | Histidine kinase | comD hk08 iH | 2.267 | 0.0000234 |

| SMU.1590 | Intracellular α-amylase | amy | 2.205 | 0.0002606 |

| SMU.880 | Multiple-sugar-binding transport system permease protein MsmG | msmG | 2.178 | 0.000069 |

| SMU.924 | Thiol peroxidase | tpx | 2.127 | 0.0009348 |

| SMU.1754c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.122 | 0.0002191 | |

| SMU.633 | Thioesterase | tesA | 2.117 | 0.0001955 |

| SMU.1126 | Pantothenate kinase | coaA | 2.116 | 0.0007698 |

| SMU.1183 | Phosphotransferase system enzyme II | mtlA2 | 2.113 | 0.000973 |

| SMU.1563 | Cation-transporting P-ATPase | pacL | 2.093 | 0.0007923 |

| SMU.404c | Hypothetical protein | 2.046 | 0.0003166 | |

| SMU.1978 | Acetate kinase | ackA comYI | 1.964 | 0.0003371 |

| SMU.881 | Sucrose phosphorylase | gftA | 1.825 | 0.0009275 |

| SMU.251 | ABC transporter permease | 1.789 | 0.0009034 | |

| SMU.204c | Hypothetical protein | 1.752 | 0.0007489 | |

| SMU.926 | GTP pyrophosphokinase family protein | 1.703 | 0.0008682 | |

| SMU.273 | Hexulose-6-phosphate synthase | rmpD | 1.635 | 0.0009137 |

| SMU.1609c | Preprotein translocase, SecG subunit | secG | 0.575 | 0.0002803 |

| SMU.2129c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.566 | 0.000596 | |

| SMU.363 | Transcriptional regulator; glutamine synthetase repressor | glnR | 0.564 | 0.0005633 |

| SMU.1519 | Glutamine ABC transport, ATP-binding protein | glnQ | 0.537 | 0.0002578 |

| SMU.672 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | citC icd | 0.513 | 0.0009986 |

| SMU.2071 | Anaerobic ribonucleoside triphosphate reductase-activating protein | nrdG | 0.488 | 0.0005869 |

| SMU.697 | Translation initiation factor IF-3 | infC | 0.486 | 0.00014 |

| SMU.299c | Bacteriocin peptide precursor | ip | 0.481 | 0.0004078 |

| SMU.2073c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.445 | 0.0000822 | |

| SMU.1897 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein; similar to BlpA | 0.435 | 0.0004475 | |

| SMU.1554c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.434 | 0.0008506 | |

| SMU.1997 | Competence-specific sigma factor | comX | 0.434 | 0.0000765 |

| SMU.1505c | Conserved hypothetical protein (phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase fragment) | pheT | 0.432 | 0.0006737 |

| SMU.611 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase/DEAD family | deaD rheA | 0.432 | 0.0004757 |

| SMU.40 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.422 | 0.0009784 | |

| SMU.396 | Glycerol uptake facilitator protein | glpF | 0.416 | 0.0005311 |

| SMU.1701c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.396 | 0.0004313 | |

| SMU.1502c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.386 | 0.0000699 | |

| SMU.1657c | Nitrogen regulatory protein PII | glnB | 0.354 | 0.0000544 |

| SMU.758c | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.303 | 0.0001941 | |

| SMU.539c | Prepilin peptidase type IV | comC hopD | 0.278 | 0.00063 |

| SMU.1004 | Glucosyltransferase I | gtfB | 0.262 | 0.0000241 |

| SMU.1175 | Sodium:alanine (or glycine) symporter | dagA | 0.117 | 0.0004863 |

TABLE 4.

Comparison of real-time PCR and microarray differences between selected genes

| Unique GenBank identification no. | Description |

n-Fold difference between aerobic/anaerobic geometric means

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray | Real-time PCR | ||

| SMU.423 | Possible bacteriocin | 41.969 | 20.619 |

| SMU.1913 | Hypothetical protein, putative immunity protein, BlpL like | 32.951 | 11.852 |

| SMU.150 | Nonlantibiotic mutacin IVA (nlmA) | 28.789 | 21.951 |

| SMU.575 | Murein hydrolase regulator (lrgA) | 11.656 | 16.139 |

| SMU.577 | Sensor histidine kinase (lytS) | 4.969 | 3.201 |

| SMU.1960 | Fructose-specific enzyme IIB component (levE) | 3.101 | 4.681 |

| SMU.879 | ABC transporter, sugar permease protein (msmF) | 2.365 | 1.882 |

| SMU.1609 | Preprotein translocase, SecG subunit | 0.575 | 0.473 |

| SMU.299 | Bacteriocin peptide precursor (ip) | 0.481 | 0.425 |

| SMU.1004 | Glucosyltransferase I (gtfB) | 0.262 | 0.451 |

| SMU.1175 | Sodium:alanine (glycine) symporter (dagA) | 0.117 | 0.071 |

Up-regulated genes.

The majority of the upregulated genes were in five functional groups, i.e., (i) hypothetical, unassigned, and unknown proteins (n = 28); (ii) energy metabolism proteins (n = 25); (iii) signal transduction proteins (n = 9); (iv) transport and binding proteins (n = 8); and (v) cellular-process proteins (n = 4) (Fig. 1; Table 3). Notably, 16 genes were strongly induced by aeration (10- to 42-fold) and most of these were either established or predicted bacteriocin-encoding genes (SMU.150 [nlmA], SMU.151 [nlmB], SMU.423, SMU.1905c, SMU.1906c, and SMU.1914c [bip]) (16) that are localized in two gene clusters, SMU.148 to SMU.152 and SMU.1903c to SMU.1914c. Because mutacins (S. mutans bacteriocins) are known to kill or inhibit the growth of closely related bacteria (16, 20), their biogenesis in an aerated environment may reflect a defense mechanism by S. mutans to inhibit the colonization of competitor organisms during early biofilm formation. A putative bacteriocin immunity protein gene, bip, that is located immediately upstream from comC was also was found to be up-regulated by about 18-fold. Interestingly, Bip has been reported to affect sensitivity to a variety of antimicrobial agents, as well as to be upregulated in the presence of low concentrations of antibiotics and during biofilm formation (31). It was postulated that Bip may have broad specificity and could provide protection against a variety of inhibitory substances (i.e., antibiotics, bacteriocins, metals, etc.), which is likely important for the resistance of S. mutans to host defenses and antagonistic interactions in nascent and mature biofilms. Consistent with the activation of bacteriocin-related genes, comD (SMU.1916c), which encodes the histidine kinase of a TCS and coordinates multiple environmental signals for the induction of com genes and development of competence (5, 27), was upregulated about 2.3-fold in the presence of oxygen. Of note, the comC quorum-sensing system (ComCDE) of S. mutans has been shown to regulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides (23, 46), including the two-peptide nonlantibiotic bacteriocin encoded by nlmAB and bip (46).

It is known that cultivation of lactic acid bacteria in the presence of air can affect glycolytic rates and elicit a shift to heterofermentative metabolism (21, 35, 45, 53, 57). Consistent with this knowledge, growth in oxygen markedly increased the expression of genes that encode the partial tricarboxylic acid cycle of S. mutans, upregulated pyruvate formate lyase, and increased expression of the water- and peroxide-forming NADH oxidases (Table 3). In addition to these changes, which can modify the way carbohydrate flows through the cell, it is noteworthy that the ccpA (carbon catabolite protein A) gene was upregulated 3.6-fold in response to growth in air. CcpA is a DNA binding protein that functions as part of a global regulatory system that controls transcription, in response to levels of glycolytic intermediates, of a variety of genes that encode products involved in the transport and catabolism of carbohydrates (38, 51). Recently, CcpA in S. mutans has been shown to serve as a major regulator of the expression of glycolytic and tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes, carbohydrate transporters, and catabolic pathways (Burne et al., unpublished data), as well as to have a central role in the control of biofilm formation (51) and the expression of the gtfBC and ftf genes (9), which encode the major exopolysaccharide-producing enzymes of S. mutans (38, 51). Consistent with the differential regulation of CcpA, a variety of carbohydrate uptake systems, including PTS (phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar transferase system) and ABC (ATP-binding cassette) transporters, were substantially upregulated (Table 3) in cells exposed to oxygen. It is noteworthy that oxygen is a major factor in the ccpA-mediated control of metabolism in Lactococcus lactis (14). Collectively, these data indicate that the machinery for the uptake and catabolism of carbohydrates is extensively regulated by oxygen at the transcriptional level for efficient carbohydrate utilization, maintenance of NAD-NADH balances, and active oxygen metabolism during growth in air. The relationship of these changes to alterations in the expression levels of CcpA remains to be explored, especially in light of the fact that the DNA binding activity of CcpA is tightly controlled by binding to serine-phosphorylated HPr and particular glycolytic intermediates (13, 14, 28, 48).

There may be considerable significance to the observation that gene products that are predicted to influence autolysis, including lrgA (SMU575c), lytT (SMU.576c), lytS (SMU.577c), SMU.1700c, and SMU.1701c, were strongly up- or down-regulated during growth with aeration (Table 3). It has been established that autolysins participate in a variety of biological processes, including cell wall turnover, cell growth, antibiotic resistance, cell-to-surface adhesion, genetic competence, and protein secretion (7, 15, 18, 33, 39). In S. mutans, the AtlA autolysin is required for efficient biofilm maturation and profoundly influences the composition of the cell envelope (3, 8). In S. aureus, the lrgAB gene products are under the control of the LytSR TCS and control autolytic behavior by modulating autolysin activity and penicillin tolerance (15). Given the demonstrated importance of autolytic activity and oxygen for S. mutans biofilm maturation (2), further investigation of the roles of the LrgAB and LytST proteins in the control of virulence-related phenotypes is warranted. It is also of note that the staphylococcal lrgAB and cidABC genes, which encode a second group of gene products that participate in autolysin regulation, are strongly influenced by glucose and acetic acid (36). Thus, the alterations in the expression of the apparent homologues of lrg and lytS in S. mutans may be induced secondarily by changes in acid end products caused by growth in air or through alterations in the levels or binding activity of CcpA. In fact, the expression of the genes in the two regions, SMU.574c to SMU.577c and SMU.1700c to SMU.1701c, was significantly influenced by loss of CcpA and affected by growth under conditions that alleviate catabolite repression in S. mutans (Burne et al., unpublished data). Finally, the large number (n = 28) of hypothetical proteins that display increased expression in cells cultivated in air are of considerable interest, as they may be important in factors in initial adherence or biofilm formation by S. mutans.

Down-regulated genes.

The 23 down-regulated genes encode predominantly hypothetical or unknown proteins (n = 8), products involved in transport and binding processes (n = 4), cellular processes (n = 2), energy metabolism (n = 2), and protein fate (n = 2). It is of note that regulators and transporters associated with amino acid metabolism, such as glnR (SMU.363), dagA (SMU.1175), glnQ (SMU.1519), and glnB (SMU.1657c), were downregulated, possibly implicating the engagement of stringent control of gene expression mediated by the nutritional alarmones (p)ppGpp. This idea is supported by the observation that relP (SMU.926), which has recently been shown to catalyze (p)ppGpp synthesis in S. mutans (26), was up-regulated about 70% in the presence of oxygen. It has been proposed that (p)ppGpp adjusts cellular metabolism by favoring the transcription of genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and stress tolerance at the expense of those essential for growth (29). On the other hand, the down-regulation of genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis is confined to a relatively small subset of genes, and the observations could be due to other factors, including alterations in carbohydrate metabolism, in CcpA levels, or in other regulatory proteins, for example, SMU.1657c, which encodes a putative nitrogen-dependent regulator of gene expression.

Oxygen and exopolysaccharide metabolism.

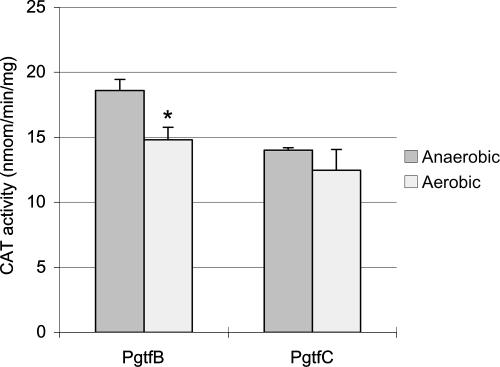

One particularly interesting finding was that the gtfB gene was down-regulated 3.3-fold under aerobic conditions. Since GtfB is a major enzyme involved in the production of adhesive, water-insoluble glucan exopolymers, down-regulation of this gene could contribute to the diminished capacity to form biofilms in air (2). It is also of interest that the expression of the gtfC gene was not altered, even at P < 0.01, considering that gtfB and gtfC are tandemly arranged and have been reported to be cotranscribed (44, 56). Given the critical roles that GtfB and GtfC play in establishing the extracellular polysaccharide matrix (glucans) that is crucial for the organisms’ adherence to and accumulation on tooth surfaces (6, 32, 54), we investigated in more detail the regulation of gtfBC in response to oxygen. To measure the expression of gtfB and gtfC, transcriptional fusions to the promoters of these genes were constructed as described in Materials and Methods, with the primers shown in Table 2 and the strains described in Table 1. Consistent with the microarray data, the expression of gtfB (TW54) alone was reduced by about 20% in response to growth in oxygen (Fig. 2). However, there was no significant difference in the expression of gtfC (TW55) under these same conditions. This result confirms the microarray data showing that gtfB expression is sensitive to aeration but also reveals that the two genes can be independently and differentially regulated in response to an environmental signal.

FIG. 2.

CAT assay. The gtfB and gtfC promoter fusions with the cat gene were inserted in a single copy into the chromosome of the wild type, and the resulting strains were designated TW54 (PgtfB) and TW55 (PgtfC), respectively. The strains were grown under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. See the text for more details. The data presented are means ± standard deviations (error bars) of at least three independent experiments. *, P < 0.01 (Student's t test).

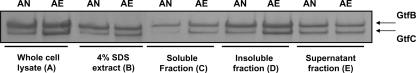

Recently, we observed that a protein band of approximately 150 kDa was present in much greater quantity in cell-associated fractions of S. mutans UA159 grown under aerobic conditions compared with anaerobic conditions (data not shown). To identify the band, it was excised from the gel and trypsin-digested protein was analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. The protein was identified as GtfC, suggesting that that the amount of GtfC enzyme associated with the surface of S. mutans increased dramatically in aerobically cultivated cells. Taking into account this finding, we investigated further the posttranscriptional regulation of the Gtf proteins by oxygen.

Localization of GtfB and GtfC is significantly affected by oxygen.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis were used to compare GtfB and GtfC levels in various protein fractions from S. mutans cells grown under anaerobic or aerobic conditions (3). The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE through a 3 to 8% gradient gel and transferred to Immobilon P membranes. Both GtfB and GtfC were detected with a polyclonal antiserum raised against purified GtfB (1:500 dilution) (52), which shares 75% amino acid identity with GtfC. In the Western blot profile of whole-cell lysates prepared by homogenizing cells in the presence SDS, both GtfB (top) and GtfC (bottom) were readily detected (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, in cells cultured aerobically, the intensity of the GtfC band, as a proportion of the reactivity with GtfB, in the 4% SDS extracts of cells (Fig. 3B), the soluble fraction prepared by bead beating in Tris buffer without SDS (Fig. 3C), and the insoluble fraction consisting of the remaining pellet that had been treated with SDS boiling buffer (Fig. 3D), was always greater than that of the GtfC band in the same fraction prepared from anaerobically grown cells. However, the relative amounts of GtfC were equivalent in the supernatant fractions, regardless of the atmosphere in which the cells were grown (Fig. 3E). These observations contrast with the transcriptional data and demonstrate that not only the localization but probably also the stability of the GtfC enzyme is affected by oxygen. On the basis of our previous observations, we believe that alterations in the localization of GtfC arise from changes in the envelope induced by growth in oxygen (2). The basis for the increase in the absolute amount of GtfC in aerobically grown cells may be due to enhanced translation or secretion of GtfC or to the downregulation or inhibition of an activity that degrades GtfC. However, there was no evidence of increased amounts of Gtf breakdown products in Western blot assays of anaerobically grown cells (data not shown). Importantly, the increased production of the GtfC enzyme in aerated cells and its strong association with the cell surface may reflect an important role of this enzyme in the early stages of biofilm formation by this organism in vivo. Specifically, strong association of the enzyme with the cells in newly forming biofilms, where O2 concentrations may be high, may enhance the synthesis of, and adherence to, water-insoluble glucans by the organism. Along these lines, the kinetic properties and stability of GtfC are known to be enhanced by binding of the enzyme to a solid surface (42, 43, 47), so cell association may increase the efficiency of this enzyme in vivo and alter the nature of the polysaccharides produced in early biofilms. Future studies will be oriented toward understanding the basis for the enhanced cell association of GtfC, which may arise, for example, from changes in the physicochemical properties of the wall, from altered expression or localization of proteins that interact with Gtf proteins, or through the synthesis of carbohydrate bridging molecules that are bound by wall-associated proteins and the Gtf proteins.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of different cell extracts from wild-type S. mutans grown under anaerobic (AN) or aerobic (AE) conditions, i.e., bead-beaten SDS boiling extract (whole-cell lysates, A), 4% SDS extracts (B), bead-beaten Tris extracts (soluble fraction, C), the insoluble fraction (D), and the supernatant fraction (E). See Materials and Methods for more details about the preparation of the cellular fractions. Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to Western blotting with an anti-GtfB polyclonal antiserum at a 1:500 dilution.

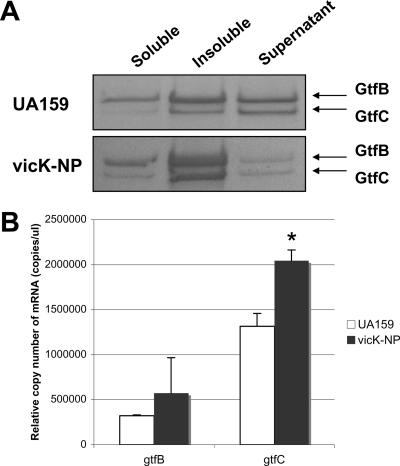

The VicRK TCS affects the localization of GtfB or GtfC.

In our recent study (2), elevated levels of cell-associated GtfC were observed in Coomassie-stained gels of whole-cell lysates and 4% SDS extracts of a VicK-deficient strain (vicK-NP, Table 1). The VicK sensor kinase protein, as a component of the VicRKX TCS, was recently reported to harbor a PAS domain, which can function as a sensor of redox potential (37). When various fractions of proteins from wild-type and vicK-NP cells were separated by SDS-PAGE, GtfB and GtfC levels were significantly elevated in both the soluble and insoluble fractions. In contrast, there was a reduction in the amount of both proteins in the supernatant fractions (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the SDS-PAGE data, gtfC mRNA levels were 20 to 30% higher in the vicK mutant (P = 0.002) during growth in the presence oxygen (Fig. 4B). Expression of the gtfB gene also showed a trend for increased transcription, but the increase was not statistically significant (P = 0.38). Collectively, the data are most supportive of the idea that while some increase in the transcription of the genes occurs in the VicK-deficient strain, alterations in the composition and biochemical properties of the surface of the cells occur (2) that allow a stronger association of the Gtf proteins with the cell. A central player in Vic-dependent modification of the cell surface appears to be the AtlA autolysin complex (2), but the array data support the idea that other autolytic pathways may play a role in modulation of the properties of the cell surface. Studies are under way to understand why loss of VicK causes substantial changes in surface protein profiles and to elucidate the nature of the changes to the cell surface or Gtf proteins that affect not only the localization of GtfB and GtfC but also biofilm formation and virulence gene expression by S. mutans.

FIG. 4.

The behaviors of GtfB and GtfC in the vicK-deficient mutant (vicK-NP). (A) Western blot analysis of different cell extracts from wild-type (UA159) and vicK-NP strains of S. mutans, i.e., bead-beaten Tris extract (soluble fraction), the insoluble fraction, and the supernatant fraction. Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to Western blotting with an anti-GtfB polyclonal antiserum at a dilution of 1:500. See the text for more details. (B) Differential expression of gtfB and gtfC in the wild-type and vicK mutant strains by real-time PCR. The data shown are means ± standard deviations (error bars) from at least three independent experiments. *, P < 0.001 (Student's t test).

Concluding remarks.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that shows a global gene expression profile of S. mutans in the presence of oxygen. The results presented herein indicate that oxygen is a key environmental signal that significantly alters the transcriptome and that these alterations strongly influence bacteriocin production, carbohydrate metabolism, and the expression of known virulence attributes. As shown here and in our previous work (2), oxygen also has profound effects on the biogenesis of a normal cell surface, exerted in large part through the Vic signal transduction pathway and the AtlA autolytic circuit. The dramatic changes in the localization of enzymes that produce the polysaccharide matrix that is characteristic of S. mutans biofilms indicates that the organisms have evolved a sophisticated sensing pathway to alter their capacity to form biofilms in response to the redox environment. Continued analysis of the effects of O2, Vic, and AtlA on the expression and localization of specific gene products is under way to provide a comprehensive picture of the way in which S. mutans integrates environmental signals during biofilm maturation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacqueline Abranches for helpful guidance in microarray experiments.

This work was supported by NIDCR grant DE13239.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abranches, J., M. M. Candella, Z. T. Wen, H. V. Baker, and R. A. Burne. 2006. Different roles of EIIABMan and EIIGlc in regulation of energy metabolism, biofilm development, and competence in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188:3748-3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, S. J., and R. A. Burne. 2007. Effects of oxygen on biofilm formation and the AtlA autolysin of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 189:6293-6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn, S. J., and R. A. Burne. 2006. The atlA operon of Streptococcus mutans: role in autolysin maturation and cell surface biogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 188:6877-6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn, S. J., J. A. Lemos, and R. A. Burne. 2005. Role of HtrA in growth and competence of Streptococcus mutans UA159. J. Bacteriol. 187:3028-3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn, S. J., Z. T. Wen, and R. A. Burne. 2006. Multilevel control of competence development and stress tolerance in Streptococcus mutans UA159. Infect. Immun. 74:1631-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banas, J. A., and M. M. Vickerman. 2003. Glucan-binding proteins of the oral streptococci. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 14:89-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackman, S. A., T. J. Smith, and S. J. Foster. 1998. The role of autolysins during vegetative growth of Bacillus subtilis 168. Microbiology 144:73-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, T. A., Jr., S. J. Ahn, R. N. Frank, Y. Y. Chen, J. A. Lemos, and R. A. Burne. 2005. A hypothetical protein of Streptococcus mutans is critical for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 73:3147-3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browngardt, C. M., Z. T. Wen, and R. A. Burne. 2004. RegM is required for optimal fructosyltransferase and glucosyltransferase gene expression in Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 240:75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burne, R. A. 1998. Oral streptococci…products of their environment. J. Dent. Res. 77:445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burne, R. A., R. G. Quivey, Jr., and R. E. Marquis. 1999. Physiologic homeostasis and stress responses in oral biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 310:441-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burne, R. A., Z. T. Wen, Y. Y. Chen, and J. E. Penders. 1999. Regulation of expression of the fructan hydrolase gene of Streptococcus mutans GS-5 by induction and carbon catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 181:2863-2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galinier, A., J. Deutscher, and I. Martin-Verstraete. 1999. Phosphorylation of either crh or HPr mediates binding of CcpA to the Bacillus subtilis xyn cre and catabolite repression of the xyn operon. J. Mol. Biol. 286:307-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaudu, P., G. Lamberet, S. Poncet, and A. Gruss. 2003. CcpA regulation of aerobic and respiration growth in Lactococcus lactis. Mol. Microbiol. 50:183-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groicher, K. H., B. A. Firek, D. F. Fujimoto, and K. W. Bayles. 2000. The Staphylococcus aureus lrgAB operon modulates murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 182:1794-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hale, J. D., Y. T. Ting, R. W. Jack, J. R. Tagg, and N. C. Heng. 2005. Bacteriocin (mutacin) production by Streptococcus mutans genome sequence reference strain UA159: elucidation of the antimicrobial repertoire by genetic dissection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7613-7617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton, I. R., and G. Svensater. 1998. Acid-regulated proteins induced by Streptococcus mutans and other oral bacteria during acid shock. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 13:292-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heilmann, C., M. Hussain, G. Peters, and F. Gotz. 1997. Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystyrene surface. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higuchi, M., M. Shimada, Y. Yamamoto, T. Hayashi, T. Koga, and Y. Kamio. 1993. Identification of two distinct NADH oxidases corresponding to H2O2-forming oxidase and H2O-forming oxidase induced in Streptococcus mutans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:2343-2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack, R. W., J. R. Tagg, and B. Ray. 1995. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 59:171-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karpenko, M. K., E. I. Kvasnikov, and A. A. Burakova. 1964. Respiration and oxidative phosphorylation in homo- and hetero-fermentative lactic acid bacteria. Mikrobiol. Zh. 26:6-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenney, E. B., and M. M. Ash, Jr. 1969. Oxidation reduction potential of developing plaque, periodontal pockets and gingival sulci. J. Periodontol. 40:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleerebezem, M., and L. E. Quadri. 2001. Peptide pheromone-dependent regulation of antimicrobial peptide production in gram-positive bacteria: a case of multicellular behavior. Peptides 22:1579-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolenbrander, P. E. 2000. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:413-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuramitsu, H. K. 1993. Virulence factors of mutans streptococci: role of molecular genetics. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 4:159-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemos, J. A., V. K. Lin, M. M. Nascimento, J. Abranches, and R. A. Burne. 2007. Three gene products govern (p)ppGpp production by Streptococcus mutans. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1568-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Y. H., N. Tang, M. B. Aspiras, P. C. Lau, J. H. Lee, R. P. Ellen, and D. G. Cvitkovitch. 2002. A quorum-sensing signaling system essential for genetic competence in Streptococcus mutans is involved in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 184:2699-2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorca, G. L., Y. J. Chung, R. D. Barabote, W. Weyler, C. H. Schilling, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 2005. Catabolite repression and activation in Bacillus subtilis: dependency on CcpA, HPr, and HprK. J. Bacteriol. 187:7826-7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magnusson, L. U., A. Farewell, and T. Nystrom. 2005. ppGpp: a global regulator in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 13:236-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marquis, R. E. 1995. Oxygen metabolism, oxidative stress and acid-base physiology of dental plaque biofilms. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15:198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto-Nakano, M., and H. K. Kuramitsu. 2006. Role of bacteriocin immunity proteins in the antimicrobial sensitivity of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188:8095-8102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattos-Graner, R. O., M. H. Napimoga, K. Fukushima, M. J. Duncan, and D. J. Smith. 2004. Comparative analysis of Gtf isozyme production and diversity in isolates of Streptococcus mutans with different biofilm growth phenotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4586-4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mercier, C., C. Durrieu, R. Briandet, E. Domakova, J. Tremblay, G. Buist, and S. Kulakauskas. 2002. Positive role of peptidoglycan breaks in lactococcal biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 46:235-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mettraux, G. R., F. A. Gusberti, and H. Graf. 1984. Oxygen tension (pO2) in untreated human periodontal pockets. J. Periodontol. 55:516-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pederson, C. S., and M. N. Albury. 1955. Variation among the heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 70:702-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice, K. C., J. B. Nelson, T. G. Patton, S. J. Yang, and K. W. Bayles. 2005. Acetic acid induces expression of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC and lrgAB murein hydrolase regulator operons. J. Bacteriol. 187:813-821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shemesh, M., A. Tam, M. Feldman, and D. Steinberg. 2006. Differential expression profiles of Streptococcus mutans ftf, gtf and vicR genes in the presence of dietary carbohydrates at early and late exponential growth phases. Carbohydr. Res. 341:2090-2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simpson, C. L., and R. R. Russell. 1998. Identification of a homolog of CcpA catabolite repressor protein in Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 66:2085-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, T. J., S. A. Blackman, and S. J. Foster. 2000. Autolysins of Bacillus subtilis: multiple enzymes with multiple functions. Microbiology 146:249-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svensäter, G., U. B. Larsson, E. C. Greif, D. G. Cvitkovitch, and I. R. Hamilton. 1997. Acid tolerance response and survival by oral bacteria. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 12:266-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svensäter, G., B. Sjogreen, and I. R. Hamilton. 2000. Multiple stress responses in Streptococcus mutans and the induction of general and stress-specific proteins. Microbiology 146(Pt. 1):107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thurnheer, T., J. R. van der Ploeg, E. Giertsen, and B. Guggenheim. 2006. Effects of Streptococcus mutans gtfC deficiency on mixed oral biofilms in vitro. Caries Res. 40:163-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsumori, H., and H. Kuramitsu. 1997. The role of the Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferases in the sucrose-dependent attachment to smooth surfaces: essential role of the GtfC enzyme. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 12:274-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ueda, S., T. Shiroza, and H. K. Kuramitsu. 1988. Sequence analysis of the gtfC gene from Streptococcus mutans GS-5. Gene 69:101-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van de Guchte, M., P. Serror, C. Chervaux, T. Smokvina, S. D. Ehrlich, and E. Maguin. 2002. Stress responses in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 82:187-216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Ploeg, J. R. 2005. Regulation of bacteriocin production in Streptococcus mutans by the quorum-sensing system required for development of genetic competence. J. Bacteriol. 187:3980-3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venkitaraman, A. R., A. M. Vacca-Smith, L. K. Kopec, and W. H. Bowen. 1995. Characterization of glucosyltransferaseB, GtfC, and GtfD in solution and on the surface of hydroxyapatite. J. Dent. Res. 74:1695-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warner, J. B., and J. S. Lolkema. 2003. CcpA-dependent carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:475-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wen, Z. T., H. V. Baker, and R. A. Burne. 2006. Influence of BrpA on critical virulence attributes of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 188:2983-2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wen, Z. T., and R. A. Burne. 2001. Construction of a new integration vector for use in Streptococcus mutans. Plasmid 45:31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wen, Z. T., and R. A. Burne. 2002. Functional genomics approach to identifying genes required for biofilm development by Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1196-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wunder, D., and W. H. Bowen. 2000. Effects of antibodies to glucosyltransferase on soluble and insolubilized enzymes. Oral Dis. 6:289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto, Y., and Y. Kamio. 2001. Oxygen metabolism and oxidative stress in lactic acid bacteria. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso 46:726-732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamashita, Y., W. H. Bowen, R. A. Burne, and H. K. Kuramitsu. 1993. Role of the Streptococcus mutans gtf genes in caries induction in the specific-pathogen-free rat model. Infect. Immun. 61:3811-3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin, J. L., N. A. Shackel, A. Zekry, P. H. McGuinness, C. Richards, K. V. Putten, G. W. McCaughan, J. M. Eris, and G. A. Bishop. 2001. Real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for measurement of cytokine and growth factor mRNA expression with fluorogenic probes or SYBR green I. Immunol. Cell Biol. 79:213-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshida, A., and H. K. Kuramitsu. 2002. Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation: utilization of a gtfB promoter-green fluorescent protein (PgtfB::gfp) construct to monitor development. Microbiology 148:3385-3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaunmüller, T., M. Eichert, H. Richter, and G. Unden. 2006. Variations in the energy metabolism of biotechnologically relevant heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria during growth on sugars and organic acids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 72:421-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]