Abstract

During sporulation, σG becomes active in the prespore upon the completion of engulfment. We show that the inactivation of the σF-directed csfB locus resulted in premature activation of σG. CsfB exerted control distinct from but overlapping with that exerted by LonA to prevent inappropriate σG activation. The artificial induction of csfB severely compromised spore formation.

Spore formation in Bacillus subtilis has become a paradigm for studying cell differentiation in prokaryotes. Central to sporulation is the compartmentalization of gene expression between the smaller prespore and the larger mother cell that result from a division, which occurs soon after the start of spore formation. The prespore (or forespore) develops into the mature, heat-resistant spore. The mother cell is necessary for spore formation but eventually lyses. The expression of different genes in the two cells is governed in part by the activation of four RNA polymerase sigma factors: σF and then σG in the prespore, and σE and then σK in the mother cell (reviewed in reference 7). The first sigma factor to become active, σF, does so soon after the formation of the spore septum, and its activation leads rapidly to the activation of σE in the mother cell. Development continues, with the mother cell engulfing the prespore. Upon the completion of engulfment, the prespore is entirely within the mother cell and so is no longer in direct contact with the medium. At this stage, σG becomes active in the prespore and σG in turn triggers the activation of σK in the mother cell.

Here, we explore the activation of σG, which is encoded by spoIIIG. The productive transcription of spoIIIG is directed by RNA polymerase containing σF and so is confined to the prespore (8). The transcription of spoIIIG is delayed compared to that of other σF-directed genes (9, 18) and requires a σE-directed signal from the mother cell (11). It also requires the expression of the σF-directed spoIIQ locus (20). Once active, σG directs the transcription of its own structural gene, setting up a positive-feedback loop for σG accumulation (7). Placing spoIIIG under a strong σF-directed promoter (17) or mutating the spoIIIG promoter (6) can result in σE-independent transcription of spoIIIG but not activation of σG. The activation of σG depends on the completion of engulfment of the prespore (19), which requires the activity of several σE-directed genes (1, 5). Other controls acting on σG, notably, the anti-sigma factor SpoIIAB, prevent it from becoming active in the mother cell (2). In the prespore, however, SpoIIAB becomes sequestered in a complex with SpoIIAA and so is thought not to block σG activity in that compartment (7).

Inactivation of csfB results in premature activation of σG.

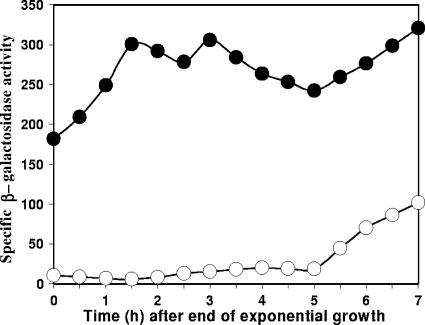

We have recently shown that when spoIIIG was relocated to an origin-proximal locus and the translocation of the origin-distal 70% of the chromosome into the prespore was blocked by a spoIIIE mutation, σE activity was no longer required either for the transcription of spoIIIG directed by σF or for the activation of σG. Thus, σG became active even though σE activation was blocked by a spoIIR mutation, and it became active in the prespore after septum formation rather than after the completion of engulfment (3). In pursuing those studies, we have found that the inactivation of the csfB locus greatly enhanced σG activity; further, that activity was detected during vegetative growth (compare data for strains SL13229 [csfB] and SL13223 [csfB+] in Fig. 1) (strains used in this study are listed in Table 1). The expression of the reporter, PsspA-lacZ, was blocked by inactivating spoIIIG in SL13229, confirming that the reporter indicated σG activity (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Inactivation of csfB causes hyperactivation of σG in a strain with chromosome translocation blocked by a spoIIIE36 mutation and spoIIIG inserted in an origin-proximal locus. Bacteria were grown in modified Schaeffer's sporulation medium at 37°C (12). The activity of σG was assessed as specific β-galactosidase activity expressed from an sspA-lacZ transcriptional fusion. Specific activity is expressed as nanomoles of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside hydrolyzed per minute per milligram (dry weight) of bacteria. Strain SL13223, csfB+ (empty circles); SL13229, csfB (filled circles).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used

| Straina | Relevant genotypeb | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SL10369 | PsspA-lacZ@sspA | Lab stock |

| SL10969 | PsspA-gfp@sspA | Lab stock |

| SL11801 | lonA::tet PsspA-gfp@sspA | Lab stock |

| SL12657 | spoIID::neo PsspA-lacZ@sspA | Lab stock |

| SL13223 | spoIIIE36 amyE::spoIIIG spoIIR::PsspA-lacZ | Lab stock |

| SL13229 | spoIIIE36 amyE::spoIIIG spoIIR::PsspA-lacZ csfBΔ::cat | This study |

| SL13315 | lonA::tet csfBΔ::cat PsspA-gfp@sspA | This study |

| SL13359 | thrC::Pspac(Hy)-csfB PsspA-lacZ@sspA | This study |

| SL13554 | csfBΔ::cat PsspA-gfp@sspA | This study |

| SL13556 | spoIIR::PsspA-lacZ | This study |

| SL13563 | spoIIR::PsspA-lacZ csfBΔ::cat | This study |

| SL13564 | spoIIR::PsspA-gfp csfBΔ::cat | This study |

| SL13767 | csfBΔ::cat PsspA-lacZ@sspA | This study |

| SL13776 | lonA::tet PsspA-lacZ@sspA | This study |

| SL13778 | csfBΔ::cat spoIID::neo PsspA-lacZ@sspA | This study |

| SL13825 | amyE::PspoIID-lacZ thrC::Pspac(Hy)-csfB | This study |

| SL13835 | amyE::PspoIIQ-lacZ thrC::Pspac(Hy)-csfB | This study |

| SL13914 | csfBΔ::cat lonA::erm PsspA-lacZ@sspA | This study |

| SL14127 | amyE::PgerE-lacZ thrC::Pspac(Hy)-csfB | This study |

| SL14244 | spoIIR::PsspA-lacZ csfBΔ::cat spoIIIG::spc | This study |

| SL14263 | csfBΔ::cat lonA::erm PsspA-lacZ@sspA spoIIIG::spc | This study |

All strains are in the genetic background of B. subtilis 168 strain BR151 (trpC2 lys-3 metB10). Details of strain construction are available upon request.

@ indicates that the fusion has been introduced by single-crossover (Campbell-like) recombination.

The csfB locus was identified as being controlled by sigma F (4). The deletion of csfB had no effect on the sporulation of a spo+ strain (4), and we presume that the dramatic effect we observed on σG activity depended on the particular mutant background used. A possible explanation of our result is that CsfB directly or indirectly prevents premature σG activation. We speculate that there is a basal level of σF-directed transcription during vegetative growth. This activity results in a low level of spoIIIG transcription, leading to the formation of some σG, but a low basal level of σF-directed csfB expression is sufficient to prevent σG activation. In the csfB mutant, however, a positive-feedback loop is established in which σG, now not inhibited by CsfB, directs spoIIIG transcription, leading to high σG activity.

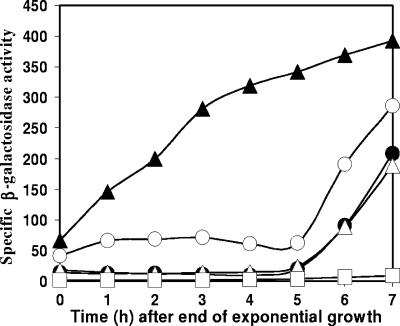

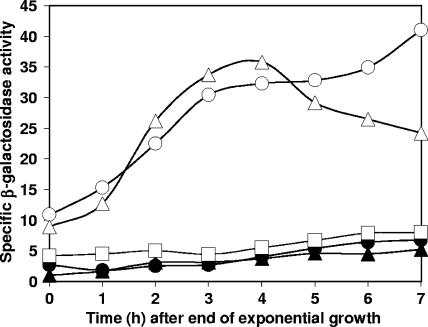

The effects described above were observed using a particular genetic background. The effects of csfB inactivation were more modest when chromosome translocation was unimpaired and spoIIIG was at its natural locus. Nevertheless, csfB inactivation did accelerate the appearance of a low level of σG activity during spore formation (compare data for strains SL13767 and SL10369 in Fig. 2). This premature expression of σG activity was also observed with the inactivation of spoIIIA or spoIIQ (data not shown), loci whose expression is normally required for the activation of σG upon the completion of engulfment (7, 10, 20). σG became active independently of the completion of engulfment (compare data for the spoIID mutants SL13778 and SL12657 in Fig. 3) and of σE activity (compare data for the spoIIR mutants SL13563 and SL13556 in Fig. 3), although the ultimate level of σG activity did not reach that of a spo+ strain. In csfB spoIID and csfB spoIIR mutants, σG activity (monitored with a gfp fusion) was usually located in the preengulfment prespore (Table 2 and data not shown). The inactivation of spoIIIG abolished the expression of the PsspA-directed reporters used, confirming that the reporters were monitoring σG activity (Fig. 3, strain SL14244, and data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of csfB and lonA inactivation on σG activity in spo+ strains. Bacteria were grown in modified Schaeffer's sporulation medium at 37°C. The activity of σG was assessed as specific β-galactosidase activity expressed from an sspA-lacZ transcriptional fusion. Strain SL10369, parent strain (filled circles); SL13767, csfB (empty circles); SL13776, lonA (empty triangles); SL13914, csfB lonA (filled triangles); SL14263, csfB lonA spoIIIG (empty squares).

FIG. 3.

Inactivation of csfB renders σG activation independent of σE activity and of the completion of engulfment. Bacteria were grown in modified Schaeffer's sporulation medium at 37°C. The activity of σG was assessed as specific β-galactosidase activity expressed from sspA-lacZ transcriptional fusions. Strain SL12657, spoIID (filled circles); SL13778, spoIID csfB (empty circles); SL13556, spoIIR (filled triangles); SL13563, spoIIR csfB (empty triangles); SL14244, spoIIR csfB spoIIIG (empty squares).

TABLE 2.

Location of GFP expressed from a σG-directed promotera

| Strain | Description or relevant genotype | Time (h)b | % Of cells displaying GFP fluorescence characterized asc:

|

Total no. of organisms scored | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | MC | WC | ||||

| SL10969 | Parent strain | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| 6 | 66 | 0 | 0 | 50 | ||

| SL11801 | lonA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3d | 205 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 8d | 155 | ||

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 10d | 256 | ||

| 6 | 32 | 0 | 4 | 143 | ||

| SL13315 | csfB lonA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 225 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 150 | ||

| 4 | 23 | 0 | 23 | 120 | ||

| 6 | 53 | 0 | 2 | 106 | ||

| SL13554 | csfB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 220 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 351 | ||

| 4 | 20 | 0 | 1 | 103 | ||

| 6 | 51e | 0 | 0 | 156 | ||

| SL13564 | spoIIR csfB | 2 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 92 |

| 4 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 183 | ||

| 6 | 36 | 0 | 3 | 75 | ||

Membranes were visualized by staining with FM4-64. σG activity was visualized using a PsspA-gfp fusion.

Time after the end of exponential growth.

GFP, green fluorescent protein; PS, prespore specific; MC, mother cell specific; WC, whole-cell fluorescence.

Weak signal detected.

Some bacteria also displayed weak activity in the mother cell.

CsfB and LonA exert overlapping controls of σG activation.

There are now several examples of overlapping regulatory mechanisms acting during spore formation (reviewed in reference 7), and we tested to see if the regulation of σG by CsfB overlapped that by the LonA protease (14, 16). LonA has previously been shown to prevent inappropriate σG activation during stationary phase or during a stress response (14). The inactivation of lonA did not completely deregulate σG; indeed, it had little effect on σG activity under sporulation conditions and did not affect spore formation (14). Under our conditions, the inactivation of lonA also had little effect on σG activity (Fig. 2, strain SL13776). However, the inactivation of both csfB and lonA resulted in substantial σG activity extending from exponential growth through sporulation for a spo+ strain (SL13914) (Fig. 2), much greater than that resulting from the inactivation of only csfB (SL13767) or lonA. This hyperactivity in the csfB lonA mutant was abolished by the inactivation of spoIIIG (Fig. 2, strain SL14263). Thus, CsfB and LonA appear to exert different but overlapping controls to prevent premature σG activation.

The effects of lonA and csfB mutations on the localization of σG activity were visualized using an sspA-gfp transcriptional fusion. The expression of this fusion is normally detected only in the prespore after the completion of engulfment (Table 2, strain SL10969). Under the conditions used, engulfment was completed between 4 and 6 h and septation was completed between 2 and 4 h after the end of exponential growth. In different experiments, 30 to 70% of organisms displayed strong prespore-specific green fluorescent protein fluorescence at 6 h whereas no fluorescing organisms were observed in samples of SL10969 at 4 h or earlier. With the csfB mutant SL13554, 1% of bacteria in the 0- and 2-h samples displayed whole-cell fluorescence (Table 2). About 20% of organisms in the 4-h sample of SL13554 displayed fluorescence specific to the preengulfment prespores, consistent with the loss of CsfB's permitting premature activation of σG in the prespore. In the 6-h sample of SL13554, about 50% of organisms displayed fluorescence in the prespores, which were by then largely engulfed.

A small proportion of lonA mutant bacteria that had not completed engulfment (strain SL11801 in 0-, 2-, and 4-h samples) displayed whole-cell fluorescence (Table 2). This fluorescence was very weak, which may account for the failure to detect σG activity at those times using lacZ as a promoter probe (Fig. 2). In contrast, about 10% of the population of a lonA csfB double-mutant strain displayed strong fluorescence during exponential growth and at early times during spore formation (Table 2). Later in sporulation, the double mutant resembled the other strains in that strong fluorescence was detected in the engulfed prespores of about 50% of the population (Table 2, strain SL13315 at 6 h). These results are consistent with the idea that CsfB and LonA exert different but overlapping controls to prevent premature σG activation. Despite the effect on the compartmentalization of σG activity, the inactivation of both csfB and lonA had little effect on spore formation under the conditions used (data not shown); however, it is possible that the ∼10% of bacteria displaying premature, strong whole-cell σG activity were unable to form spores.

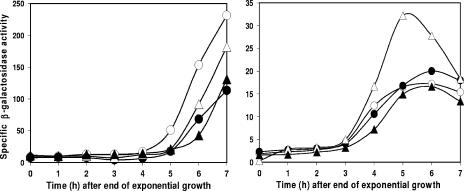

Artificial induction of csfB expression blocked spore formation.

The csfB locus was placed under the control of the strong, IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible Pspac(Hy) promoter (13) and integrated at the ectopic thrC locus. The Pspac(Hy)-csfB construct was introduced into spo+ strains containing lacZ under the control of σG, σF, σE, or σK. The presence of IPTG had no observable effect on growth but reduced spore formation about 1,000-fold compared to that in cultures without IPTG (Table 3). This effect was independent of lonA (data not shown). Examination by microscopy indicated that organisms completed engulfment efficiently in the presence of IPTG but did not go on to form phase-bright spores. The induction of csfB reduced σG activity by about 50% and delayed the appearance of activity by about 1 h compared to no induction (Fig. 4, left panel, strain SL13359). The induction of csfB also resulted in about 50% reduction of σE activity (Fig. 4, right panel, strain SL13825) but no reduction of σF activity (Fig. 4, right panel, strain SL13835). There was a reduction and delay in σK activity caused by csfB induction (Fig. 4, left panel, strain SL14127), which may be a secondary consequence of the effect on σG. It is not known if CsfB acts directly or indirectly on these sigma factors. CsfB is predicted to be a 64-residue protein (4). It shows no similarity to proteins of known function, and its mode of action is unknown. Given that csfB transcription is ordinarily directed by σF, so that csfB is expressed predominantly in the prespore, the effect of CsfB on σE (and possibly σK) may represent a fail-safe mechanism to help prevent σE from becoming active in the prespore. The observed effects on reporters of σE, σG, and σK activities caused by csfB induction (Fig. 4) seem inadequate to explain the dramatic effect on spore formation. However, it may be that CsfB has a strong effect on particular promoters, leading to the block in spore formation.

TABLE 3.

Effect of csfB induction on spore formation

| Strain | Description or relevant genotypea | % Of parent level of sporulation in the absence of IPTG as measured:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Without IPTG | With IPTG | ||

| BR151 | Parent strain | 100b | 94 |

| SL13359 | Pspac(Hy)-csfB PsspA-lacZ@sspA | 58 | 0.08 |

| SL13825 | Pspac(Hy)-csfB amyE::PspoIID-lacZ | 68 | 0.05 |

| SL13835 | Pspac(Hy)-csfB amyE::PspoIIQ-lacZ | 84 | 0.04 |

| SL14127 | Pspac(Hy)-csfB amyE::PgerE-lacZ | 59 | 0.06 |

@ indicates that the fusion has been introduced by single-crossover (Campbell-like) recombination.

Equivalent to 2.1 × 108 heat-resistant spores/ml.

FIG. 4.

Effect of induction of csfB expression from the Pspac(Hy) promoter on the activities of sporulation-specific σ factors, assessed with lacZ transcriptional fusions directed by the different σ factors. Bacteria were grown in modified Schaeffer's sporulation medium at 37°C without IPTG (empty symbols) or with 1 mM IPTG throughout growth and sporulation (filled symbols). (Left panel) σG, strain SL13359 (circles); σK, strain SL14127 (triangles); (right panel) σF, strain SL13835 (circles); σE, strain SL13825 (triangles).

CsfB is one of several entities that regulate σG activation. The main role for CsfB during spore formation is probably to help prevent premature activation of σG in the prespore. In the absence of CsfB, σG becomes active after the formation of the sporulation septum rather than after the completion of engulfment (Table 2). This premature activation is independent of the SpoIIIA-SpoIIIJ pathway; CsfB does not appear to be involved in that pathway, which is required for the more substantial activation of σG that normally occurs in the prespore following the completion of engulfment (7, 10, 15). CsfB is also not required for the repression of σG by SpoIIAB in the mother cell (data not shown). CsfB has a role overlapping with (though distinct from) that of LonA (14) in regulating σG, as the loss of both greatly enhanced premature σG activity (Fig. 3). Despite this expanding list of regulators, our understanding of σG regulation remains incomplete.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM43577 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abanes-De Mello, A., Y. L. Sun, S. Aung, and K. Pogliano. 2002. A cytoskeleton-like role for the bacterial cell wall during engulfment of the Bacillus subtilis forespore. Genes Dev. 16:3253-3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chary, V. K., M. Meloni, D. W. Hilbert, and P. J. Piggot. 2005. Control of the expression and compartmentalization of σG activity during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis by regulators of σF and σE. J. Bacteriol. 187:6832-6840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chary, V. K., P. Xenopoulos, and P. J. Piggot. 2006. Blocking chromosome translocation during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis can result in prespore-specific activation of σG that is independent of σE and of engulfment. J. Bacteriol. 188:7267-7273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decatour, A., and R. Losick. 1996. Identification of additional genes under the control of the transcription factor σF of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:5039-5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eichenberger, P., P. Fawcett, and R. Losick. 2001. A three-protein inhibitor of polar septation during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1147-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans, L., A. Feucht, and J. Errington. 2004. Genetic analysis of the Bacillus subtilis sigG promoter, which controls the sporulation-specific transcription factor σG. Microbiology 150:2277-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilbert, D. W., and P. J. Piggot. 2004. Compartmentalization of gene expression during Bacillus subtilis spore formation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:234-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karmazyn-Campelli, C., C. Bonamy, B. Savelli, and P. Stragier. 1989. Tandem genes encoding factors for consecutive steps of development in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 3:150-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karow, M. L., and P. J. Piggot. 1995. Construction of gusA transcriptional fusion vectors for Bacillus subtilis and their utilization for studies of spore formation. Gene 163:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellner, E. M., A. Decatur, and C. P. Moran, Jr. 1996. Two-stage regulation of an anti-σ factor determines developmental fate during bacterial endospore formation. Mol. Microbiol. 21:913-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partridge, S. R., and J. Errington. 1993. The importance of morphological events and intercellular interactions in the regulation of prespore-specific gene expression during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 8:945-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piggot, P. J., and C. A. M. Curtis. 1987. Analysis of the regulation of gene expression during Bacillus subtilis sporulation by manipulation of the copy number of spo-lacZ fusions. J. Bacteriol. 169:1260-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quisel, J. D., W. F. Burkholder, and A. D. Grossman. 2001. In vivo effects of sporulation kinases on mutant Spo0A proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:6573-6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt, R., A. L. Decatur, P. N. Rather, C. P. Moran, Jr., and R. Losick. 1994. Bacillus subtilis Lon protease prevents inappropriate transcription of genes under the control of the sporulation transcription factor σG. J. Bacteriol. 176:6528-6537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrano, M., L. Côrte, J. Opdyke, C. P. Moran, Jr., and A. O. Henriques. 2003. Expression of SpoIIIJ in the prespore is sufficient for activation of σG and for sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 185:3905-3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serrano, M., S. Hövel, C. P. Moran, Jr., A. O. Henriques, and U. Völker. 2001. Forespore-specific transcription of the lonB gene during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:2995-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serrano, M., A. Neves, C. M. Soares, C. P. Moran, Jr., and A. O. Henriques. 2004. Role of the anti-sigma factor SpoIIAB in regulation of σG during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 186:4000-4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steil, L., M. Serrano, A. O. Henriques, and U. Völker. 2005. Genome-wide analysis of temporally regulated and compartment-specific gene expression in sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 151:399-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stragier, P. 1989. Temporal and spatial control of gene expression during sporulation: from facts to speculations, p. 243-254. In I. Smith, R. A. Slepecky, and P. Setlow (ed.), Regulation of prokaryotic development. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 20.Sun, Y. L., M. D. Sharp, and K. Pogliano. 2000. A dispensable role for forespore-specific gene expression in engulfment of the forespore during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:2919-2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]