Abstract

The chimpanzee monoclonal antibody (MAb) 5H2 is specific for dengue virus type 4 (DENV-4) and neutralizes the virus at a high titer in vitro. The epitope detected by the antibody was mapped by sequencing neutralization escape variants of the virus. One variant contained a Lys174-Glu substitution and another contained a Pro176-Leu substitution in domain I of the DENV-4 envelope protein (E). These mutations reduced binding affinity for the antibody 18- to >100-fold. Humanized immunoglobulin G (IgG) 5H2, originally produced from an expression vector, has been shown to be a variant containing a nine-amino-acid deletion in the Fc region which completely ablates antibody-dependent enhancement of DENV replication in vitro. The variant MAb, termed IgG 5H2 ΔD, is particularly attractive for exploring its protective capacity in vivo. Passive transfer of IgG 5H2 ΔD at 20 μg/mouse afforded 50% protection of suckling mice against challenge with 25 50% lethal doses of mouse neurovirulent DENV-4 strain H241. Passive transfer of antibody to monkeys was conducted to demonstrate proof of concept for protection against DENV challenge. Monkeys that received 2 mg/kg of body weight of IgG 5H2 ΔD were completely protected against 100 50% monkey infectious doses (MID50) of DENV-4, as indicated by the absence of viremia and seroconversion. A DENV-4 escape mutant that contained a Lys174-Glu substitution identical to that found in vitro was isolated from monkeys challenged with 106 MID50 of DENV-4. This substitution was also present in all naturally occurring isolates belonging to DENV-4 genotype III. These studies have important implications for possible antibody-mediated prevention of DENV infection.

The four dengue virus serotypes (dengue virus types 1 to 4 [DENV-1 to DENV-4]) cause more morbidity in humans than any other arthropod-borne flaviviruses (40). Up to 100 million DENV infections occur every year, mostly in tropical and subtropical areas where the vector mosquitoes, principally Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, are present. Dengue illnesses range from mild fever to severe dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS), which has fatality rates ranging from <1% to 5% in children. The most severe dengue (>90% fatality rate) occurs in patients reinfected with DENV of a serotype different from that in the primary infection (15, 50). Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of DENV replication has been proposed as an underlying pathogenic mechanism of severe DHF/DSS (17). A safe and effective vaccine against dengue is still not available.

Early studies of DENV infections in human volunteers showed that homotypic immunity against the same serotype is life-long but that heterotypic immunity against other serotypes lasts only months (49). Since antibodies provide the important component of acquired immunity against infection, type-specific immunity afforded by antibody may contribute significantly to long-term protection. Antigenic differences exist among strains of the same serotype (21). DENV variants that form defined genotypes, in some cases with restricted geographic distributions, have been isolated during and between epidemics (31, 47). Molecular epidemiologic analysis of DENV-4 showed that these virus variants probably arose and disappeared due to high mutation rates associated with adaptive evolution in the transmission between mosquitoes and human hosts (2, 27).

The three-dimensional (3-D) structure of the flavivirus envelope glycoprotein (E) was first reported for tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) (46). The 3-D structures of DENV-2 E and DENV-3 E have also become available recently (37, 39). Flavivirus E proteins assume a similar flat, elongated, dimeric architecture. Each E subunit folds itself into three structurally distinct domains, termed domains I, II, and III. Domain I is organized into an eight-stranded central β-barrel structure. The two large loops that connect the strands of domain I form the elongated domain II, which contains the flavivirus conserved fusion peptide at its distal end. Domain III can fold independently into an immunoglobulin-like module and is also connected to domain I.

Studies on functional activities and binding specificities of mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) have revealed the antigenic structure of flavivirus E, which is remarkably similar to the 3-D structure (13, 20, 34, 48). Antibodies that recognize epitopes involving determinants in domain II are broadly cross-reactive, but weakly to nonneutralizing (10, 54). Binding of these antibodies can affect virus-cell membrane fusion, and viral structural integrity is required for binding of domain II-reactive antibodies, as a reducing agent or low-pH treatment of virions diminished their binding affinities (13, 48). Antibodies reactive to domain III are mostly type- or subtype-specific efficient neutralizers of viral infectivity and can block viral attachment (6, 41). Only relatively few MAbs reactive to domain I epitopes on DENV E have been isolated and characterized (48, 53). The functional role of the domain I structure remains poorly understood.

Murine MAbs that are highly neutralizing against several flaviviruses in vitro have been shown to also be highly protective in animal models (3, 26). However, these mouse MAbs are not directly useful for clinical application because of their immunogenicity in humans. We have identified MAbs from chimpanzees infected with multiple DENV serotypes. These chimpanzee antibodies are valuable for studies of functional and structural specificities and their role in protection in a primate model relevant to human DENV infection. For example, one of these experiments is the passive transfer of antibodies for prevention of DENV infection in monkeys. Humanized MAb immunoglobulin G (IgG) 1A5 recognizes sequences in the fusion loop in domain II and is cross-reactive with DENV and most other flaviviruses (9, 10). MAb IgG 5H2 is type specific and highly efficient for neutralization of DENV-4 in vitro (36).

In the course of constructing these humanized MAbs, we isolated an IgG 5H2 variant that had a nine-amino-acid deletion in the Fc region, resulting from alternative splicing due to a nucleotide substitution in the expression plasmid (8). The variant MAb, designated IgG 5H2 ΔD hereafter, and full-length IgG 5H2 neutralized DENV-4 equally efficiently. We also demonstrated that the ADE activity of DENV replication mediated by IgG 5H2 was abrogated by the nine-amino-acid deletion. Such an antibody is particularly attractive for further exploring its potential for clinical application. In this study, the epitope determinants of the DENV-4-specific MAb were determined by isolation and sequence analysis of antigenic variants. We also demonstrate protection against DENV-4 challenge in mice and rhesus monkeys by passively transferred humanized antibody.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DENV-4 and cells.

Two DENV-4 stocks of strain 814669 (genotype II) isolated from Dominica in 1981, designated DENV-4 (FRhL) and DENV-4 (C6/36), were used for selection of antigenic variants. DENV-4 (C6/36) was recovered from RNA-transfected C6/36 cells and amplified once in the same cells (30). DENV-4 (FRhL) was prepared by passage three times in fetal rhesus lung (FRhL) cells, starting from virus recovered from RNA-transfected C6/36 cells (R. Putnak and C. J. Lai, unpublished observations). The full-length DNA clone of DENV-4 (C6/36) contained an XhoI site introduced near the 3′ end of the E gene to be used as a genetic marker. This XhoI site was absent in DENV-4 (FRhL). Mosquito C6/36 cells were grown in minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. Simian Vero cells and FRhL cells were also grown in MEM plus 10% FBS and antibiotics. Human erythroleukemic K562 cells were propagated in Iscove medium. Media were purchased from Invitrogen.

Antibodies.

Chimpanzee Fab 5H2, humanized antibody IgG 5H2, and the variant IgG 5H2 ΔD, containing a nine-amino-acid deletion in the Fc region, were used (8, 36). IgG 5H2 ΔD was produced from a clone of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells selected for high-level expression as described previously (36). Briefly, the CHO cells were adapted to grow in suspension culture in a low-serum medium. IgG 5H2 ΔD was purified from the medium by affinity binding on a protein A column (Kemp Biotechnology, Gaithersburg, MD). IgG 5H2 was produced by transient transfection of 293E cells with an expression plasmid containing the full-length Fc sequence (Kemp Biotechnology, Gaithersburg, MD). Mouse MAb 1H10, specific to DENV-4 E, and MAb 1G6, specific to DENV-4 NS1, were kindly supplied by R. Putnak (Walter Reed Army Institute of Research). DENV-4-specific hyperimmune mouse ascites fluid was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Anti-His (C terminus) antibody coupled to alkaline phosphatase was purchased from Invitrogen.

Selection of antigenic variants.

Antigenic variants were generated by partial neutralization of DENV-4 in the presence of Fab 5H2, followed by amplification of the surviving viruses in Vero cells. Approximately 1 × 105 focus-forming units (FFU) (PFU by plaque assay) of parental DENV-4 (C6/36) or DENV-4 (FRhL) was mixed with 8 μg of Fab 5H2 in 0.1 ml MEM plus 2% FBS and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The mixture was added to a monolayer of Vero cells in a T25 flask for adsorption at 37°C for 1 h. After removal of excess inoculum, Fab 5H2 was added to the infected cells at 16 μg/ml in 5 ml of MEM plus 2% FBS, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 7 days. This was repeated for second and third rounds of neutralization and infection of Vero cells. DENV-4 resistant to Fab 5H2 neutralization appeared after the third round of neutralization. Variants were plaque purified three times on Vero cells and amplified in C6/36 cells. The growth properties of DENV-4 antigenic variants and their parental viruses were analyzed by infecting C6/36 cells or Vero cells at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 and determining the viral yield at various time points.

Plaque reduction neutralization test.

Approximately 50 FFU of DENV-4 was mixed with 10-fold serial dilutions of Fab 5H2 or IgG 5H2 ΔD in 0.2 ml and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The mixture was added to Vero cell monolayers in a 24-well plate in duplicate, adsorbed for 30 min, and overlaid with MEM containing 1% gum tragacanth (Sigma). Four days after infection, viral plaques that formed on the cell monolayer were detected by immunostaining as described previously (36).

Binding affinity of Fab 5H2 and avidity of IgG 5H2 ΔD.

Measurements of the binding affinity (Kd [equilibrium dissociation constant]) of Fab 5H2 and the binding avidity (Kd) of IgG 5H2 ΔD for DENV-4 or its derived variants were performed using equilibrium enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, DENV-4-specific mouse MAb 1H10 was used to coat the wells of a microtiter plate. The wells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin, and then each virus was added in serial dilutions in duplicate. Following incubation at 37°C for 1 h and removal of excess virus, affinity-purified cross-reactive chimpanzee Fab 1A5 was applied to the wells. Fab 1A5 that bound to each virus was detected using goat anti-human IgG-alkaline phosphatase (Sigma). In this manner, the amount of each virus that gave a similar optical density was standardized and selected for MAb capture. In the binding assay, Fab 5H2 or IgG 5H2 ΔD was added in serial dilutions to react with virus captured with MAb 1H10 on the plate. Equilibrium affinity constants were calculated as the antibody concentrations that gave 50% maximum binding. Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay was performed according to a previously described procedure (5).

DNA sequence analysis.

Viral RNAs from each parental DENV-4 strain and its derived antigenic variant were extracted using TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription (RT) of viral RNAs was performed using a complementary sequence in the NS1 region as a primer to generate cDNAs. The C-prM-E DNA fragment was amplified by PCR, and sequence analysis was performed using primers spanning the region in an ABI sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Analysis of neutralization and ADE in vitro.

Neutralization of DENV-4 before or after adsorption to Vero cells was performed by using a constant amount of virus and dilutions of IgG 5H2 ΔD essentially as described previously (6). For ADE assay, serial dilutions of full-length IgG 5H2 were mixed with a constant amount of parental DENV-4 or an antigenic variant and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The mixture was added to an equal volume (0.1 ml) of 4 × 105 K562 cells in Iscove medium plus 2% FBS and incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation, rinsed, and transferred to a 24-well plate for further incubation for 2 days at 37°C. The percentage of infected cells was determined by flow cytometry (8).

Mouse protection studies.

Groups of 3- to 4-day-old BALB/c mice were inoculated with IgG 5H2 ΔD by the intraperitoneal route at a dose of 4, 20, or 92 μg in 50 μl per mouse, and mice in the control group received only phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) diluent. One day later, mice were challenged with 25 50% lethal doses (LD50) (135 FFU) of neurovirulent DENV-4 H241 in 30 μl by the intracerebral route (25). Animals in the control group and insufficiently protected mice developed encephalitis, showing signs of paralysis at 10 to 14 days postchallenge; these mice were euthanized by the close of the day when illness was recognized. Animals which developed slow movement but no signs of paralysis generally survived. Four weeks after challenge, surviving animals were euthanized and the experiment was terminated. Animals were monitored according to Animal Research Advisory Committee (ARAC) guidelines.

Passive immunization of rhesus monkeys with IgG 5H2 ΔD for protection against DENV-4 challenge.

Adult rhesus monkeys who were seronegative for DENV were inoculated in the saphenous vein with humanized IgG 5H2 ΔD in PBS at the indicated dose. The control monkeys received PBS diluent only. Twenty-four hours later, monkeys were injected subcutaneously in the upper back shoulder area with DENV-4 at the dose specified in each study. The diluent of the challenge virus was MEM plus 0.25% human serum albumin. Following DENV-4 challenge, monkeys were bled daily (for up to 12 days) for assay of viremia and then biweekly from the femoral vein for assay of antibody. Following DENV-4 challenge, monkeys were not expected to develop any clinical signs. Monkeys were kept in cages, housed in a mosquito-free environment by Bioqual, Inc. (Rockville, MD), and handled by trained staff. All animal procedures were performed according to the guidelines of ARAC. The experiment was terminated 8 weeks after challenge.

Analysis of viremia and seroresponse.

For assay of FFU of DENV-4 in serum, freshly thawed monkey serum samples (0.1 ml) were mixed with 0.1 ml of MEM, and the mixture was added directly to a confluent Vero cell monolayer in a 24-well plate. The cell monolayer was stained for DENV-infected foci 4 days later, as described previously (42). Quantitative RT-PCR (TaqMan) was also used to detect DENV genome copy numbers in the serum samples (32). Analysis of serum antibodies was carried out by plaque reduction neutralization test or by radioimmunoprecipitation followed by gel electrophoresis. Mouse MAb 1G6 was used in parallel to identify the NS1 immune precipitate.

RESULTS

Fab 5H2 neutralization escape variants of DENV-4.

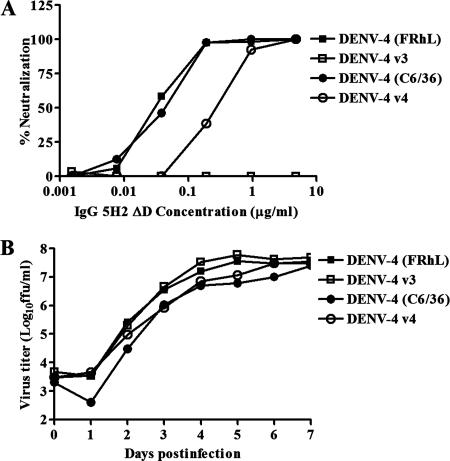

DENV-4 (FRhL) and DENV-4 (C6/36) were both used for selection of antigenic variants of Fab 5H2. The Fab 5H2 fragment, which neutralizes DENV-4 at a high titer, was the first material available for isolation of neutralization escape mutants, before the derived full-length human IgG 5H2 was constructed. An antigenic variant, designated DENV-4 v3, was recovered from DENV-4 (FRhL) after three cycles of neutralization and propagation. A second antigenic variant, designated DENV-4 v4, was selected from DENV-4 (C6/36), also after three cycles of neutralization and propagation. Using DENV-4 v3 for the neutralization assay, Fab 5H2 had a 50% plaque reduction neutralization titer (PRNT50) of >10 μg/ml. Using DENV-4 v4 for neutralization, the Fab had a PRNT50 of approximately 5 μg/ml, compared with PRNT50s of 0.3 to 0.5 μg/ml obtained with the parental viruses. When both parental viruses were used, the complete IgG 5H2 molecule and its derived variant, IgG 5H2 ΔD, had similar titers of 0.03 to 0.05 μg/ml. IgG 5H2 ΔD failed to neutralize DENV-4 v3 at 10 μg/ml (PRNT50, >10 μg/ml) and had a PRNT50 of approximately 0.5 μg/ml against DENV-4 v4 (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) In vitro neutralization assay of IgG 5H2 ΔD against DENV-4 parental viruses and antigenic variants. (B) Growth curves for DENV-4 antigenic variants and parental viruses in C6/36 cells. The multiplicity of infection was 0.1.

The growth properties of DENV-4 variants and their parental viruses were compared. Parental DENV-4 (FRhL) produced a small-plaque morphology compared with parental DENV-4 (C6/36) on Vero cells. The plaque size of each of the variants was similar to that of its parental virus (data not shown). The growth rate of each variant was similar to that of its parental virus in C6/36 cells and in Vero cells. Figure 1B shows that each of these viruses grew to similar titers in C6/36 cells over a 7-day period. The growth curves for the variants and their parent viruses were also similar for Vero cells (data not shown). Clearly, the mutations in the variants did not confer a growth advantage or disadvantage compared to wild-type DENV-4.

Sequence analysis of DENV-4 antigenic variants.

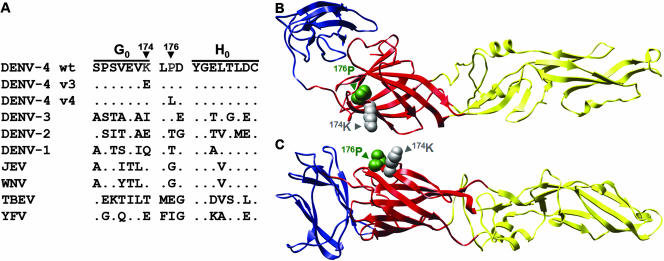

The amino acid change in the C-prM-E structural protein region in each of the variants was determined in order to map the epitope on DENV-4 E that bound to Fab 5H2. Parental DENV-4 (C6/36) and DENV-4 (FRhL) differed by a substitution of Glu for Gln at position 363 in E, possibly resulting from passage and adaptation for growth in FRhL cells. DENV-4 v3 acquired a single A-to-G mutation at nucleotide 1458 that resulted in substitution of Glu for Lys at position 174 in E. In contrast, DENV-4 v4 contained a C-to-T mutation at nucleotide 1465 that produced a substitution of Leu for Pro at position 176 in E. The close spacing of these mutations indicates that Lys174 and Pro176 represent important determinants of the Fab 5H2-reactive epitope. Lys174 of DENV-4 E is unique among the DENVs. Pro176 is present in DENV-3, but a Thr occupies this position in DENV-1 and DENV-2. There is considerable variation at each of these positions among the major flaviviruses, as seen in the alignment of the amino acid sequences at and surrounding these mutations (Fig. 2A). In the 3-D structure, these closely spaced amino acids are located near or within the three-amino-acid loop between the G0 and H0 β-strands in domain I (Fig. 2B). The loop region is exposed on the E surface, consistent with its accessibility for antibody binding (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

(A) Comparison of amino acid sequences of E proteins of wild-type DENV-4, antigenic variants, and other flaviviruses. In the sequence alignment, a dot indicates an identical amino acid compared with DENV-4. The localization of amino acid substitutions at positions 174 and 176 in the 3-D structure of monomeric DENV-4 E, based on the DENV-2 E model, is shown from the top (B) and from the side (C). Domain I is in red, domain II is in yellow, and domain III is in blue. Structural modeling of DENV-4 E was performed using SwissModel and the published crystal coordinates of DENV-2 E (1OAN.pdb) as the template (12, 37). Molecular graphic images were produced using the UCSF Chimera package from the Resource for Bio-Computing, Visualization and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (44).

Binding affinities of Fab 5H2 and IgG 5H2 ΔD for DENV-4.

An ELISA was performed to semiquantify the binding affinities of Fab 5H2 and the derived IgG 5H2 ΔD for parental and variant DENV-4 (Table 1). Binding of Fab 5H2 to the parental viruses reached a maximum at about 0.1 μg/ml. The half-maximal binding value (apparent binding affinity, termed ELISA Kd) was 0.36 nM for DENV-4 (FRhL) and 0.21 nM for DENV-4 (C6/36). Under the same conditions, the ELISA Kd for DENV-4 v3 was >100 nM, a reduction of >100-fold, and the ELISA Kd for DENV-4 v4 was 3.7 nM, a reduction of approximately 18-fold. Since the full-length IgG 5H2 molecule and its derived variant IgG 5H2 ΔD had similar neutralization titers against parental DENV-4, the avidity for binding of IgG 5H2 ΔD to these viruses was also determined. There was only an approximately twofold reduction of binding avidity for DENV-4 v4 compared to that for its parental virus. On the other hand, the binding avidity of IgG 5H2 ΔD for DENV-4 v3 was reduced greatly compared to that for its parent. In each case, a reduction of antibody binding affinity (avidity) correlated with increased resistance to antibody neutralization.

TABLE 1.

Relative binding affinities of Fab 5H2 and avidities of IgG 5H2 ΔD determined by ELISAa

| Virus | Fab 5H2

|

IgG 5H2 ΔD

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd(nM) | Fold reduction | Kd(nM) | Fold reduction | |

| DENV-4 (FRhL) | 0.36 | 0.23 | ||

| DENV-4 v3 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| DENV-4 (C6/36) | 0.21 | 0.14 | ||

| DENV-4 v4 | 3.71 | 17.7 | 0.32 | 2.3 |

Kd values of parental DENV-4 and derived mutants were determined from the concentrations giving 50% maximal binding in ELISA. Two or three separate binding experiments were performed for each virus to obtain the average value.

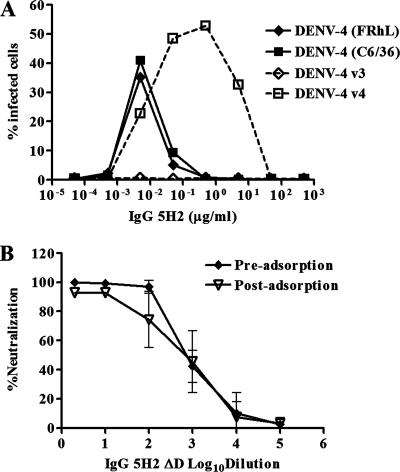

ADE and other functional properties of the DENV-4-specific epitope.

We showed previously that sequence variations at the antibody binding sites of DENV-4 were responsible for the differences in IgG 1A5 ADE activity (8). In that experiment, DENV-cross-reactive IgG 1A5, which recognizes epitope determinants involving the fusion peptide in domain II, was used to study enhancement of DENV infection in monocytic K562 cells. Antigenic variants exhibited different levels of enhancement dependent on the antibody avidity. This finding was further tested by comparison of IgG 5H2-mediated enhancing activities on DENV-4 parental viruses and their derived antigenic variants v3 and v4, which had reduced binding avidities. As predicted, IgG 5H2 enhanced the infection of parental viruses, but not low-avidity DENV-4 v3, in K562 cells (Fig. 3A). In contrast, enhancement of infection by DENV-4 v4 was detected over a broad range of IgG 5H2 concentrations (10 down to 0.005 μg/ml), reminiscent of the enhancement pattern mediated by the cross-reactive MAb IgG 1A5. This analysis showed that the type-specific IgG 5H2-reactive epitope also mediated ADE and that its activity depended on the binding interaction of the antibody-virus complex.

FIG. 3.

ADE of DENV-4-specific epitope and neutralization of DENV-4 by IgG 5H2 ΔD before and after adsorption to Vero cells. A comparison of ADE of replication of parental DENV-4 and its derived antigenic variants in K562 cells exposed to full-length IgG 5H2 was performed. (A) Percentage of cells infected with DENV-4, determined by flow cytometry. (B) In pre- and postadsorption antibody neutralization assays, a constant amount of DENV-4 (70 FFU) was tested against various dilutions of IgG 5H2 ΔD.

The conformational dependency of the Fab 5H2-reactive epitope was also investigated. While treatment of DENV-4 E in the cell lysate with 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate had no apparent effect on binding to Fab 5H2, UV irradiation (at approximately 2,000 μW/cm2) or 2-mercaptoethanol treatment of the virus completely abolished DENV-4 binding to Fab 5H2, as determined by ELISA or Western blot analysis (data not shown). These results are consistent with the notion that the integrity of the Fab 5H2-reactive epitope on DENV-4 E is conformationally dependent. HI assay showed that the HI titer of IgG 5H2 ΔD (PRNT50, 1:9,000) was <4, whereas the HI titers of polyclonal convalescent-phase sera from DENV-4-infected monkeys (PRNT50, 1:600) were >128 against sucrose-acetone-extracted DENV-4 intact antigen prepared from the parental 814669 strain. This finding suggests that the type-specific 5H2 epitope on DENV-4 E is neutralization positive but HI negative. To determine whether IgG 5H2 ΔD neutralized by blocking viral adsorption, a comparative neutralization assay was performed on DENV-4 before and after adsorption to Vero cells (Fig. 3B). Neutralization of DENV-4 by IgG 5H2 ΔD was nearly equally efficient before and after binding of the virus to cells, suggesting that the antibody neutralized at a step following binding of DENV-4 to the cells.

Protection against DENV-4 infection of mice.

Mice infected intracerebrally with a mouse-adapted neurovirulent DENV develop encephalitis and eventually die in the absence of intervention. This mouse model was employed to analyze the protective efficacy of IgG 5H2 ΔD against DENV-4 infection in vivo. Table 2 shows that the survival rates of mice after challenge with neurovirulent DENV-4 H241 depended on the dose of IgG 5H2 ΔD transferred. Nearly all mice in the control group and the group that received the lowest dose (4 μg/mouse) of antibody succumbed to DENV-4 H241 infection (survival rates, 10 to 13%). The survival rate was 46% for the group that received 20 μg of the antibody and 92% for the group that received 92 μg of antibody after challenge. Thus, the amount of IgG 5H2 ΔD that afforded 50% protection of mice was approximately 20 μg per mouse.

TABLE 2.

Protection of suckling mice from challenge with a neurovirulent DENV-4 strain by passive transfer of IgG 5H2 ΔDa

| IgG 5H2 ΔD dose (μg/mouse) | No. of mice in group | No. (%) of surviving mice |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8 | 1 (12.5) |

| 4 | 10 | 1 (10.0) |

| 20 | 11 | 5 (45.5) |

| 92 | 12 | 11 (91.7) |

Groups of 3- to 4-day-old suckling BALB/c mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with IgG 5H2 ΔD at the dose indicated and then challenged with 25 LD50 of neurovirulent DENV-4 H241 24 h later. The eight control mice received PBS diluent instead of an irrelevant human IgG antibody, which also had no effect on virus neutralization (8).

Protection of monkeys by passive transfer of antibody.

Next, we determined if IgG 5H2 ΔD protected against DENV-4 infection in an animal model relevant to human infection. The amount of DENV used for infection may be critical for analysis of protection by antibody in rhesus monkeys. Therefore, we determined the 50% monkey infectious dose (MID50) of the challenge DENV-4 strain 814669 that had been used earlier for chimpanzee infection for antibody isolation in order to better evaluate the protective capacity of the neutralizing antibody IgG 5H2 ΔD. Pairs of monkeys were infected with a range of DENV-4 doses (1.0, 0.1, and 0.01 FFU), and seroconversion was determined 8 weeks later. This titration showed that the DENV-4 MID50 was 0.1 FFU (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Determination of MID50 of DENV-4 strain 814669a

| Monkey | DENV-4 titer (FFU) | Seroconversion |

|---|---|---|

| RH665 | 1 | + |

| RH667 | 1 | + |

| RH668 | 0.1 | + |

| RH671 | 0.1 | − |

| RH687 | 0.01 | − |

| RH691 | 0.01 | − |

Monkeys were inoculated with 10-fold dilutions of DENV-4, and seroconversion was determined by IgG ELISA 8 weeks after infection.

In the next experiment, four monkeys that had been given 2 mg of IgG 5H2 ΔD/kg of body weight intravenously and two control monkeys that received PBS only were challenged with 100 MID50 (equivalent to 10 FFU) of DENV-4 strain 814669 1 day later. Table 4 shows that viremia was detected in one control monkey, lasting for 3 days with a peak virus titer of 120 FFU/ml on day 7, and the positive viremia was confirmed by the more sensitive TaqMan RT-PCR analysis. Viremia was not detected in samples from the other control monkey, either by direct plaque assay or by PCR assay. Nevertheless, both control monkeys were clearly infected with DENV-4, since each developed anti-NS1 antibody as measured by radioimmunoprecipitation (Table 4). Viremia was not detected in any of the four monkeys that received IgG 5H2 ΔD antibody and were subsequently challenged with DENV-4. Seroanalysis by radioimmunoprecipitation also showed that anti-NS1 antibody was not detected in these four monkeys (Table 4), indicating that DENV-4 was completely neutralized and its replication was prevented in these monkeys. This experiment demonstrates proof of principle that passive transfer of antibody IgG 5H2 ΔD can protect monkeys (and presumably humans) against DENV-4 infection.

TABLE 4.

Protection of monkeys against DENV-4 challenge by passive transfer of IgG5H2 ΔDa

| Monkey | Antibody (2 mg/kg) transferred | Viremia (day after challenge)

|

Seroconversion | Protection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus assay (FFU/ml) | RT-PCR (FFU/ml equivalents) | ||||

| H671 | No | 13 (6), 120 (7), 27 (8) | 120 (6), 500 (7), 550 (8) | Yes | No |

| H687 | No | ND | ND | Yes | No |

| CF7H | Yes | ND | ND | No | Yes |

| CF7B | Yes | ND | ND | No | Yes |

| CJ4X | Yes | ND | ND | No | Yes |

| H742 | Yes | ND | ND | No | Yes |

Two control monkeys (H671 and H687) received PBS in lieu of antibody. Rhesus monkeys were each challenged with 100 MID50 of DENV-4 1 day after antibody transfer. Viremia titer was analyzed by direct plaque analysis and by RT-PCR (TaqMan). Seroconversion was determined by the presence of anti-NS1 antibodies, as measured by radioimmunoprecipitation. Evidence of infection, i.e., seroconversion, was used to assess protection. ND, not detected.

Isolation of antigenic variants from monkeys infected with 106 MID50 DENV-4.

Since partial neutralization of DENV-4 by Fab 5H2 generated escape mutants in vitro, we wanted to study if DENV-4 antigenic variants could also be isolated in vivo. Four monkeys that received IgG 5H2 ΔD at 0.9 mg/kg by passive transfer and two monkeys that received PBS alone as controls were each challenged with 106 MID50 of DENV-4 24 h later. Table 5 shows that viremia was detected for 5 to 6 days, with the peak titer ranging from 10 to 230 FFU/ml in the control monkeys. Monkeys that received the antibody also developed viremia with a similar duration and peak virus titers. One of these monkeys (RH685) showed a delayed onset and short duration of viremia compared to the other monkeys, suggesting the possibility of reduced DENV-4 replication and partial protection by antibody. This monkey also had a brief (2 days) viremic period, in contrast to 4 to 6 days of viremia for the other monkeys. The result was further supported by seroanalysis using radioimmunoprecipitation. All four monkeys that received antibody by passive transfer, as well as the two control monkeys, developed antibodies against prM and NS1, confirming that there was DENV-4 replication in these monkeys. The monkey with delayed and minimal viremia developed only a low level of anti-prM and anti-NS1 antibodies compared to the other monkeys, confirming the attenuated infection (data not shown). It is clear that additional experiments will be needed to support this finding, as the delayed viremia onset was detected in only one of four monkeys in the group and because of the overall small number of animals used in the study.

TABLE 5.

Viremia following challenge with 106 MID50 DENV-4 in rhesus monkeys passively administered IgG 5H2 ΔDa

| Monkey | IgG 5H2 ΔD (0.9 mg/ml) administration | Viremia

|

Peak virus titer (FFU/ml)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset day | Duration (days) | |||

| RH690 | − | 2 | 6 | 230 |

| RH670 | − | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| RH692 | + | 6 | 6 | 801 |

| RH688 | + | 6 | 4 | 2001,2 |

| RH693 | + | 4 | 5 | 2102 |

| RH685 | + | 8 | 2 | 10 |

Rhesus monkeys that received 0.9 mg/kg of IgG 5H2 ΔD (approximately 300 PRNT50/ml) intravenously were challenged subcutaneously with 1 × 106 MID50 DENV-4 24 h later. Control monkeys (RH690 and RH670) that received the diluent PBS were similarly challenged. Monkey serum samples obtained on days 1 to 12 postchallenge were analyzed for viremia by focus-forming assay.

Putative neutralization escape mutant viruses recovered had Lys174-Arg (1) and Lys174-Glu (2) mutations.

The viruses present in several viremic samples from passively immunized monkeys were recovered, and the sequence in the C-prM-E region was analyzed. A substitution of Glu for Lys174 in E was found in the viruses recovered from the day 6 serum sample of monkey RH693 and from the day 8 sample of monkey RH688. A substitution of Arg for Lys174 was found in the viruses recovered from the day 9 samples of monkey 692 and monkey RH688. Thus, both variant viruses were recovered from monkey RH688. Other mutations were not detected in the C-prM-E region of viruses recovered from monkeys. Wild-type DENV-4 was not recovered from the samples of monkeys RH688, RH692, and RH693. Significantly, the substitution of Glu for Lys174 was identical to that found in antigenic variant v3 isolated in vitro.

DISCUSSION

Panels of chimpanzee MAbs have been recovered from infections with multiple DENV serotypes by repertoire cloning. DENV-4-specific MAb 5H2 is unique in that it is highly potent for in vitro neutralization of virus isolates from different geographic regions (36). The epitope reactive with 5H2 was determined by isolation and sequencing of antigenic variants of DENV-4. Important sites for binding of 5H2 were localized to amino acids 174 and 176 in E, near or within the three-amino-acid loop between the H0 and G0 β-strands in domain I of the 3-D structure. The location of these closely spaced amino acids on the glycoprotein surface is consistent with their accessibility to antibody binding. Alternatively, these mutations in domain I may influence conformational changes in E that expose the true epitope bound by MAb 5H2. Conclusive mapping of the epitope reactive with 5H2 will await data from crystallographic analysis of E-antibody complexes. There is >40% sequence diversity among DENVs and other flaviviruses in the region that includes the three-amino-acid loop and five amino acids flanking each side. The epitope was conformationally dependent, as treatment of DENV-4 with UV irradiation or a reducing agent completely destroyed the binding capacity of 5H2. The substitution of Leu for Pro176 was a nonconservative change that would have increased the local hydrophobicity of the region surrounding residues 174 to 178 of E from a mean hydrophobicity score of −6.1 for wild-type DENV-4 to a score of −2.3 for variant DENV-4 v4 (29). For the region encompassing residues 172 to 176, the substitution of Glu for Lys174 was a charged amino acid change that would have increased the local hydrophobicity of the protein from −2.4 for wild-type DENV-4 to 2.0 for variant DENV-4 v3. Neither of these substitutions in E altered the growth characteristics of DENV-4 in mosquito or mammalian cells in vitro. However, these changes resulted in marked reductions in the binding affinity of 5H2 for the variant viruses.

The epitopes detected by subtype/type-specific TBEV-neutralizing MAb i2 and MAb IC3 have been localized to positions 171 and 181 (corresponding to DENV-4 positions 170 and 180) in domain I, respectively (22, 34). An antigenic variant of TBEV that has diminished reactivity with MAb IC3 shows a significant loss of mouse neuroinvasiveness, but its growth phenotype in cultured cells appears not to be affected (22). MAb i2, which also reacts with domain I of TBEV, has been shown to inhibit virus-induced fusion (14). Only relatively few mouse MAbs map to epitopes in domain I of DENV by competitive binding assay, and these MAbs are nonneutralizing (48). The DENV cross-reactive MAb 4G2 selected a DENV-2 escape mutant that contained substitutions at Ser169 (domain I) and Glu275 (domain II) (53). The DENV-2 escape mutant had an altered fusion activity, but the responsible mutation was not precisely assigned.

An antigenic model of DENV E is beginning to emerge from epitope analysis of antibodies recovered from DENV-infected chimpanzees by repertoire cloning (9, 10, 36). The majority of chimpanzee antibodies are cross-reactive and non- to weakly neutralizing and react with epitope determinants in domain II. Surprisingly, neutralizing antibodies that react with domain III-specific peptides (DENV amino acids 295 to 394) prepared in Escherichia coli have not been recovered, despite numerous attempts. Instead, the highly potent, DENV-4-neutralizing MAb 5H2, which binds to sites in domain I, has been recovered. Epitope analysis of antibodies from West Nile virus-infected humans also showed a predominant number of antibodies reactive to domains I and II, whereas domain III-specific antibodies are relatively rare (43, 55). This is despite evidence suggesting that E domain III may be responsible for binding to a putative receptor(s) on the cell surface (6, 23, 37, 46), and many flavivirus type-specific, highly neutralizing MAbs recovered from mice have been shown to react with determinants in domain III (41, 48). Our results suggest that the DENV-4-specific epitope on E in domain I may be an important target in a vaccine strategy to elicit strong neutralizing antibodies against DENV infection in humans.

The binding interaction of IgG 5H2 ΔD with each of the two DENV-4 antigenic variants was reduced. The in vitro neutralization experiment showed that IgG 5H2 ΔD neutralized DENV-4 before and after adsorption to the cell surface equally efficiently, suggesting that the antibody neutralized primarily at a step after attachment of DENV-4 to the cells. One interpretation is that the antibody probably blocks viral infectivity by preventing viral entry or subsequent membrane fusion. Since mutations of amino acids that are positioned in the interface between domain I and II structures affect the threshold pH for fusion, it has been proposed that both domains change orientation during a conformational shift, enabling fusion (4, 38). Binding of IgG 5H2 ΔD to domain I on the virus surface could interfere with such structural reorganization, thus preventing fusion from occurring. Neutralization by West Nile virus-specific, mouse-derived MAb E16, which reacts with determinants in domain III, has also been shown to take place at postattachment steps by blocking conformational changes of the envelope glycoprotein (41). The chimpanzee DENV-4-neutralizing MAb IgG 5H2 represents the first antibody reactive to a domain I epitope on DENV E. The epitope probably plays an important role in eliciting strong DENV type-specific immunity in humans. Inclusion of this epitope is an important consideration for an effective vaccine.

The protective efficacy of IgG 5H2 ΔD was evaluated using a mouse DENV encephalitis model described previously (24, 52). Passive transfer of IgG 5H2 ΔD at a dose of approximately 20 μg/mouse afforded 50% protection against challenge with 25 LD50 of the mouse-neurovirulent DENV-4 strain H241. This protective concentration was higher than the 2 to 4 μg/mouse observed with the most highly neutralizing murine MAbs against Japanese encephalitis virus or yellow fever virus (1, 26, 51). However, the strain and age of mice and the virus challenge dose used in each case were also different. To demonstrate proof of concept for protection, the virus challenge dose of DENV-4 was selected to be 100 MID50 (10 FFU) per monkey. Monkeys that received 2 mg/kg of IgG 5H2 ΔD were completely protected, as indicated by the absence of viremia and lack of seroconversion. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to evaluate protection of primates against DENV infection by passive transfer of antibody.

In the monkey model, the virus challenge dose may be critical in assessing the protective capacity of antibody. Our results showed that the MID50 dose of DENV-4 strain 814669 was about 0.1 FFU. For comparison, some values obtained earlier were 22 50% mosquito infectious doses (approximately 0.09 FFU) for DENV-4 H-241, 9.5 50% mosquito infectious doses (approximately 0.01 FFU) for DENV-2 PR-159 (28), 0.5 FFU for DENV-4 strain 341750 Carib, and 2 × 104 FFU for its derived attenuated vaccine (18, 35). Conceivably, the infectivity of DENVs depends on the serotype and passage history. An early study showed that as little as one mouse LD50 of DENV-1 could infect a human being (49). Others also found that the 50% human infectious dose of the candidate vaccine DENV-4 delta 30 was 0.1 FFU (7). In nature, the virus titer transmitted in a mosquito bite could vary widely, depending on the mosquito species, extrinsic incubation period (in insects), etc. The amount of DENV orally transmitted by A. albopictus was measured at between 102 and 104 50% mosquito infectious doses (11). Thus, the amount of DENV-4 administered to the monkeys was approximately equivalent to one mosquito bite.

Protection was not observed in monkeys given 0.9 mg/kg of IgG 5H2 ΔD by passive transfer and challenged with 106 MID50 of DENV-4. Significantly, wild-type DENV-4 was not recovered from viremic samples, indicating that IgG 5H2 ΔD prevented spread of the virus in infected monkeys, even though the amount of virus administered was approximately equivalent to 104 mosquito bites. One antigenic variant contained a Glu-to-Lys174 substitution identical to that found in vitro. Molecular epidemiologic analysis of a large number of DENV-4 strains recovered from humans has demonstrated the presence of three genotypes (genotypes I, II, and III) (27). DENV-4 strains belonging to the smallest group, genotype III, were isolated in Bangkok, Thailand, during the period 1997-2001. Remarkably, all five members contained the Glu-to-Lys174 mutation. At least three of these genotype III viruses were recovered from DHF patients undergoing DENV reinfections with various degrees of disease severity. The presence of the Glu-to-Lys174 substitution might be essential to allow replication, especially in a DENV-4-immune background. It is not known whether an immunological selection pressure was involved in the appearance and disappearance of this particular genotype. There is evidence that DENV-4 strains undergo continual evolutionary change at a rate as high as 1 × 10−3 nucleotide substitution per site per year (27). The Glu-to-Lys174 mutation has not been identified among members of DENV-4 genotypes I and II, the latter of which represents the most prevalent genotype in the Americas and some parts of Asia. Fortunately, the DENV-4 genotype III viruses have thus far remained localized, although their evolutionary course remains uncertain. It remains to be tested whether IgG 5H2 ΔD is effective for neutralization of these naturally occurring strains of DENV-4. The utility of antibody-mediated prevention of dengue fever may be complicated by the apparent rapid selection of neutralization escape mutants in vitro and in monkeys. Clearly, high concentrations of MAb that allow complete neutralization of the virus should be used. Another possible strategy is the combined application of neutralizing MAbs that are preferably reactive to epitopes located in different domains of E.

ADE has been proposed as an underlying mechanism of severe dengue fever associated with reinfection by a different DENV serotype (17). Enhancement of DENV replication by antibody can be demonstrated readily in vitro with Fc-bearing monocytic cells (19, 33) and has been confirmed in vivo (8, 16). A direct link between ADE and severe DENV illness is still lacking, and the pathogenesis of such illness remains to be elucidated. We have shown that the cross-reactive, weakly neutralizing humanized antibody IgG 1A5 enhanced DENV-4 replication in Fc receptor-bearing K562 cells over a wide range of subneutralizing concentrations (10−3 to 103 μg/ml) (8). Type-specific full-length IgG 5H2 also showed ADE activity, albeit at a low and narrow concentration range compared to that for cross-reactive IgG 1A5. ADE analysis of DENV-4 variants (Fig. 3A) showed that antibody neutralization and enhancement of infection are related and based on common viral determinants. Recently, the stoichiometry of ADE and antibody neutralization of West Nile virus infection was determined using appropriate cell lines (45). Interestingly, the peak enhancement was demonstrated with subneutralizing antibody concentrations corresponding to approximately 25% occupancy of available binding sites on the virion, which is lower than that required to neutralize the virus.

There remains a concern about the safety of immunization against DENV by passive antibody transfer. As shown recently, introduction of the nine-amino-acid deletion in the antibody Fc region entirely ablates the ADE activity of DENV-4 replication in vitro (8). It is likely that IgG 5H2 ΔD would not mediate ADE of DENV infection in vivo. These results warrant further development of the antibody transfer strategy for potential use in prevention and/or treatment of DENV infections. Before this goal can be realized, the effects of alterations in the Fc region on antibody stability and effector cell functions that play a role in viral clearance will need to be characterized further.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Putnak for help with HI assays, staff members of Bioqual Inc. for help with procedures in primate studies, and the staff of Comparative Medicine Branch, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, for help with procedures in mouse studies.

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. The Resource for Bio-Computing, Visualization and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, is supported by NIH grant P41 RR-01081.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beasley, D. W., L. Li, M. T. Suderman, F. Guirakhoo, D. W. Trent, T. P. Monath, R. E. Shope, and A. D. Barrett. 2004. Protection against Japanese encephalitis virus strains representing four genotypes by passive transfer of sera raised against ChimeriVax-JE experimental vaccine. Vaccine 22:3722-3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett, S. N., E. C. Holmes, M. Chirivella, D. M. Rodriguez, M. Beltran, V. Vorndam, D. J. Gubler, and W. O. McMillan. 2003. Selection-driven evolution of emergent dengue virus. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20:1650-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandriss, M. W., J. J. Schlesinger, E. E. Walsh, and M. Briselli. 1986. Lethal 17D yellow fever encephalitis in mice. I. Passive protection by monoclonal antibodies to the envelope proteins of 17D yellow fever and dengue 2 viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 67:229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bressanelli, S., K. Stiasny, S. L. Allison, E. A. Stura, S. Duquerroy, J. Lescar, F. X. Heinz, and F. A. Rey. 2004. Structure of a flavivirus envelope glycoprotein in its low-pH-induced membrane fusion conformation. EMBO J. 23:728-738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke, D. H., and J. Casals. 1958. Techniques for hemagglutination and hemagglutination-inhibition with arthropod-borne viruses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 7:561-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crill, W. D., and J. T. Roehrig. 2001. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to domain III of dengue virus E glycoprotein are the most efficient blockers of virus adsorption to Vero cells. J. Virol. 75:7769-7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durbin, A. P., S. S. Whitehead, J. McArthur, J. R. Perreault, J. E. Blaney, Jr., B. Thumar, B. R. Murphy, and R. A. Karron. 2005. rDEN4delta30, a live attenuated dengue virus type 4 vaccine candidate, is safe, immunogenic, and highly infectious in healthy adult volunteers. J. Infect. Dis. 191:710-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goncalvez, A. P., R. E. Engle, M. St. Claire, R. H. Purcell, and C. J. Lai. 2007. Monoclonal antibody-mediated enhancement of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo and strategies for prevention. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:9422-9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goncalvez, A. P., R. Men, C. Wernly, R. H. Purcell, and C. J. Lai. 2004. Chimpanzee Fab fragments and a derived humanized immunoglobulin G1 antibody that efficiently cross-neutralize dengue type 1 and type 2 viruses. J. Virol. 78:12910-12918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goncalvez, A. P., R. H. Purcell, and C. J. Lai. 2004. Epitope determinants of a chimpanzee Fab antibody that efficiently cross-neutralizes dengue type 1 and type 2 viruses map to inside and in close proximity to fusion loop of the dengue type 2 virus envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 78:12919-12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gubler, D. J., and L. Rosen. 1976. A simple technique for demonstrating transmission of dengue virus by mosquitoes without the use of vertebrate hosts. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 25:146-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guex, N., and M. C. Peitsch. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guirakhoo, F., F. X. Heinz, and C. Kunz. 1989. Epitope model of tick-borne encephalitis virus envelope glycoprotein E: analysis of structural properties, role of carbohydrate side chain, and conformational changes occurring at acidic pH. Virology 169:90-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guirakhoo, F., F. X. Heinz, C. W. Mandl, H. Holzmann, and C. Kunz. 1991. Fusion activity of flaviviruses: comparison of mature and immature (prM-containing) tick-borne encephalitis virions. J. Gen. Virol. 72:1323-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guzman, M. G., G. Kouri, E. Martinez, J. Bravo, R. Riveron, M. Soler, S. Vazquez, and L. Morier. 1987. Clinical and serologic study of Cuban children with dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS). Bull. Pan Am. Health Organ. 21:270-279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halstead, S. B. 1979. In vivo enhancement of dengue virus infection in rhesus monkeys by passively transferred antibody. J. Infect. Dis. 140:527-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halstead, S. B. 1970. Observations related to pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. VI. Hypotheses and discussion. Yale J. Biol. Med. 42:350-362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halstead, S. B., and N. J. Marchette. 2003. Biologic properties of dengue viruses following serial passage in primary dog kidney cells: studies at the University of Hawaii. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 69:5-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halstead, S. B., and E. J. O'Rourke. 1977. Antibody-enhanced dengue virus infection in primate leukocytes. Nature 265:739-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinz, F. X. 1986. Epitope mapping of flavivirus glycoproteins. Adv. Virus Res. 31:103-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henchal, E. A., P. M. Repik, J. M. McCown, and W. E. Brandt. 1986. Identification of an antigenic and genetic variant of dengue-4 virus from the Caribbean. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 35:393-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holzmann, H., K. Stiasny, M. Ecker, C. Kunz, and F. X. Heinz. 1997. Characterization of monoclonal antibody-escape mutants of tick-borne encephalitis virus with reduced neuroinvasiveness in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 78:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung, J. J., M. T. Hsieh, M. J. Young, C. L. Kao, C. C. King, and W. Chang. 2004. An external loop region of domain III of dengue virus type 2 envelope protein is involved in serotype-specific binding to mosquito but not mammalian cells. J. Virol. 78:378-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman, B. M., P. L. Summers, D. R. Dubois, and K. H. Eckels. 1987. Monoclonal antibodies against dengue 2 virus E-glycoprotein protect mice against lethal dengue infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 36:427-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawano, H., V. Rostapshov, L. Rosen, and C. J. Lai. 1993. Genetic determinants of dengue type 4 virus neurovirulence for mice. J. Virol. 67:6567-6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura-Kuroda, J., and K. Yasui. 1988. Protection of mice against Japanese encephalitis virus by passive administration with monoclonal antibodies. J. Immunol. 141:3606-3610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klungthong, C., C. Zhang, M. P. Mammen, Jr., S. Ubol, and E. C. Holmes. 2004. The molecular epidemiology of dengue virus serotype 4 in Bangkok, Thailand. Virology 329:168-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraiselburd, E., D. J. Gubler, and M. J. Kessler. 1985. Quantity of dengue virus required to infect rhesus monkeys. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79:248-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyte, J., and R. F. Doolittle. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157:105-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai, C. J., B. T. Zhao, H. Hori, and M. Bray. 1991. Infectious RNA transcribed from stably cloned full-length cDNA of dengue type 4 virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5139-5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lanciotti, R. S., D. J. Gubler, and D. W. Trent. 1997. Molecular evolution and phylogeny of dengue-4 viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 78:2279-2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanciotti, R. S., and A. J. Kerst. 2001. Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification assays for rapid detection of West Nile and St. Louis encephalitis viruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4506-4513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Littaua, R., I. Kurane, and F. A. Ennis. 1990. Human IgG Fc receptor II mediates antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection. J. Immunol. 144:3183-3186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandl, C. W., F. Guirakhoo, H. Holzmann, F. X. Heinz, and C. Kunz. 1989. Antigenic structure of the flavivirus envelope protein E at the molecular level, using tick-borne encephalitis virus as a model. J. Virol. 63:564-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchette, N. J., D. R. Dubois, L. K. Larsen, P. L. Summers, E. G. Kraiselburd, D. J. Gubler, and K. H. Eckels. 1990. Preparation of an attenuated dengue 4 (341750 Carib) virus vaccine. I. Pre-clinical studies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 43:212-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Men, R., T. Yamashiro, A. P. Goncalvez, C. Wernly, D. J. Schofield, S. U. Emerson, R. H. Purcell, and C. J. Lai. 2004. Identification of chimpanzee Fab fragments by repertoire cloning and production of a full-length humanized immunoglobulin G1 antibody that is highly efficient for neutralization of dengue type 4 virus. J. Virol. 78:4665-4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modis, Y., S. Ogata, D. Clements, and S. C. Harrison. 2003. A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:6986-6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Modis, Y., S. Ogata, D. Clements, and S. C. Harrison. 2004. Structure of the dengue virus envelope protein after membrane fusion. Nature 427:313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Modis, Y., S. Ogata, D. Clements, and S. C. Harrison. 2005. Variable surface epitopes in the crystal structure of dengue virus type 3 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 79:1223-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monath, T. P. 1994. Dengue: the risk to developed and developing countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2395-2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nybakken, G. E., T. Oliphant, S. Johnson, S. Burke, M. S. Diamond, and D. H. Fremont. 2005. Structural basis of West Nile virus neutralization by a therapeutic antibody. Nature 437:764-769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okuno, Y., T. Fukunaga, M. Tadano, Y. Okamoto, T. Ohnishi, and M. Takagi. 1985. Rapid focus reduction neutralization test of Japanese encephalitis virus in microtiter system. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 86:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliphant, T., G. E. Nybakken, S. K. Austin, Q. Xu, J. Bramson, M. Loeb, M. Throsby, D. H. Fremont, T. C. Pierson, and M. S. Diamond. 2007. Induction of epitope-specific neutralizing antibodies against West Nile virus. J. Virol. 81:11828-11839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettersen, E. F., T. D. Goddard, C. C. Huang, G. S. Couch, D. M. Greenblatt, E. C. Meng, and T. E. Ferrin. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pierson, T. C., Q. Xu, S. Nelson, T. Oliphant, G. E. Nybakken, D. H. Fremont, and M. S. Diamond. 2007. The stoichiometry of antibody-mediated neutralization and enhancement of West Nile virus neutralization. Cell Host Microbiol. 1:135-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rey, F. A., F. X. Heinz, C. Mandl, C. Kunz, and S. C. Harrison. 1995. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 A resolution. Nature 375:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rico-Hesse, R. 2003. Microevolution and virulence of dengue viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 59:315-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roehrig, J. T., R. A. Bolin, and R. G. Kelly. 1998. Monoclonal antibody mapping of the envelope glycoprotein of the dengue 2 virus, Jamaica. Virology 246:317-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabin, A. B. 1952. Research on dengue during World War II. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1:30-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sangkawibha, N., S. Rojanasuphot, S. Ahandrik, S. Viriyapongse, S. Jatanasen, V. Salitul, B. Phanthumachinda, and S. B. Halstead. 1984. Risk factors in dengue shock syndrome: a prospective epidemiologic study in Rayong, Thailand. I. The 1980 outbreak. Am. J. Epidemiol. 120:653-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlesinger, J. J., M. W. Brandriss, C. B. Cropp, and T. P. Monath. 1986. Protection against yellow fever in monkeys by immunization with yellow fever virus nonstructural protein NS1. J. Virol. 60:1153-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlesinger, W., and J. W. Frankel. 1952. Adaptation of the New Guinea B strain of dengue virus to suckling and to adult Swiss mice; a study in viral variation. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1:66-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serafin, I. L., and J. G. Aaskov. 2001. Identification of epitopes on the envelope (E) protein of dengue 2 and dengue 3 viruses using monoclonal antibodies. Arch. Virol. 146:2469-2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stiasny, K., S. Kiermayr, H. Holzmann, and F. X. Heinz. 2006. Cryptic properties of a cluster of dominant flavivirus cross-reactive antigenic sites. J. Virol. 80:9557-9568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Throsby, M., C. Geuijen, J. Goudsmit, A. Q. Bakker, J. Korimbocus, R. A. Kramer, M. Clijsters-van der Horst, M. de Jong, M. Jongeneelen, S. Thijsse, R. Smit, T. J. Visser, N. Bijl, W. E. Marissen, M. Loeb, D. J. Kelvin, W. Preiser, J. ter Meulen, and J. de Kruif. 2006. Isolation and characterization of human monoclonal antibodies from individuals infected with West Nile virus. J. Virol. 80:6982-6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]