Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, RDS2 encodes a zinc cluster transcription factor with unknown function. Here, we unravel a key function of Rds2 in gluconeogenesis using chromatin immunoprecipitation-chip technology. While we observed that Rds2 binds to only a few promoters in glucose-containing medium, it binds many additional genes when the medium is shifted to ethanol, a nonfermentable carbon source. Interestingly, many of these genes are involved in gluconeogenesis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and the glyoxylate cycle. Importantly, we show that Rds2 has a dual function: it directly activates the expression of gluconeogenic structural genes while it represses the expression of negative regulators of this pathway. We also show that the purified DNA binding domain of Rds2 binds in vitro to carbon source response elements found in the promoters of target genes. Finally, we show that upon a shift to ethanol, Rds2 activation is correlated with its hyperphosphorylation by the Snf1 kinase. In summary, we have characterized Rds2 as a novel major regulator of gluconeogenesis.

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae adapts to glucose exhaustion through various mechanisms, including reprogramming of gene expression and protein synthesis (for reviews, see references 4 and 47). The release from glucose repression alters the transcription of genes involved in various cellular processes, such as gluconeogenesis, the glyoxylate cycle, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, respiration, β-oxidation, and utilization or transport of alternative sugars. Enzymes of the gluconeogenesis pathway and the glyoxylate cycle are indispensable for growth on nonfermentable carbon sources, such as ethanol, lactate, or glycerol. Activation of the genes that encode these enzymes depends on the upstream activating sequences (UASs) found in their promoters, such as carbon source response elements (CSREs) (reference 42 and references therein). These elements are under the control of the transcriptional regulators Cat8 and Sip4, which are members of the binuclear zinc cluster protein family (21, 30).

The expression and activities of CAT8 and SIP4 are regulated by glucose, and this process is mediated by the Snf1 kinase (19). The enzyme is complexed with the activating subunit Snf4 and one of the three alternative β subunits, Gal83, Sip1, or Sip2 (26, 52). Substantial evidence demonstrates an essential role for Snf1 in glucose derepression through the activation of the above-mentioned activators, as well as deactivation of Mig1, a C2H2 zinc finger protein. In the presence of glucose, Mig1 binds to upstream repressing sequences found in target genes, such as CAT8 (8, 47). The release of Mig1 from the CAT8 promoter allows its expression. Cat8 is then phosphorylated by Snf1, which leads to the derepression of gluconeogenic genes (14, 21, 40, 48). Additional studies have indicated unequal roles for the activators, suggesting a more important contribution by Cat8, as it regulates SIP4 expression. Cells lacking Cat8 display growth defects with nonfermentable carbon sources, while this phenotype is not observed with a Δsip4 strain (21, 30, 39). Although Sip4 has been shown to be a substrate of Snf1 and to be capable of binding directly to CSREs in vitro, its exact contribution and target genes remain to be defined (50).

As stated above, the transcriptional regulators Cat8 and Sip4 belong to the family of binuclear zinc cluster proteins. These proteins (hereafter referred to as the zinc cluster proteins) are unique to fungi and are characterized by the presence of a zinc cluster motif with the consensus sequence CysX2CysX6CysX5-12CysX2CysX6-8Cys. These well-conserved cysteines bind to two zinc atoms and coordinate the folding of the zinc cluster domains involved in DNA recognition, as most zinc cluster proteins are DNA binding transcription factors (32). The founding member and prototype of this class is Gal4, a transcriptional activator of galactose catabolism. Like many other classes of transcriptional regulators, zinc cluster proteins contain separate functional domains. With a few exceptions, the activation domain is found at the C terminus while the DNA binding domain is located near the N terminus. Within the DNA binding domain, a variant linker region bridges a cysteine-rich region and a dimerization domain and contributes to DNA binding specificity. The dimerization region is characterized by a structural feature reminiscent of the leucine zipper heptad repeat, which mediates protein-protein interactions (32). In addition, there is a regulatory domain (also called the middle homology region) located between the DNA binding domain and the C-terminal acidic activation domain (45). The regulatory domain displays less homology among members of this class and has been shown to be involved in controlling their transcriptional activities.

Zinc cluster proteins preferentially bind DNA elements containing CGG triplets (32, 45). For instance, a crystal structure of the Gal4 DNA binding domain revealed that Gal4 binds as a homodimer to inverted CGG triplets spaced by 11 bp (CGG N11 CCG) (34). Hap1, another member of this family, recognizes direct CGG triplets separated by 6 bp (CGG N6 CGG), while Leu3 binds to everted CGG repeats with triplets oriented in opposite directions (CCG N4 CGG) (15, 17, 23, 28, 53). Other zinc cluster proteins have been shown to target promoters as heterodimers (1, 33, 44).

We previously performed a phenotypic analysis of zinc cluster genes (3). Our results showed that a partial deletion of the open reading frame (ORF) YPL133C (in the FY73 background) resulted in impaired growth on the nonfermentable carbon source lactate or glycerol, as well as hypersensitivity to the cell wall-perturbing agent calcofluor white. We also showed that cells lacking YPL133C displayed increased sensitivity to the antifungal drug ketoconazole. YPL133C was named RDS2 for regulator of drug sensitivity (2). However, the exact role of this zinc cluster protein is not known, and its target genes have not been identified.

To better understand the role of Rds2, we conducted a genome-wide location analysis (chromatin immunoprecipitation [ChIP]-chip) to identify its direct target genes. Our results from ChIP-chip performed in rich medium containing 2% glucose revealed that a limited number of promoters are bound by Rds2 under these conditions. We observed binding of Rds2 to the promoter region of a key gluconeogenic gene called PCK1, encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. Pck1 catalyzes an early step in gluconeogenesis and is essential for growth on nonfermentable carbon sources. Interestingly, Rds2 binding to the promoters of other CSRE-containing genes (PCK1, FBP1, YAT1, MLS1, SFC1, MDH2, and IDP2) and TCA cycle genes (CIT1, KGD2, SDH4, and LSC2), as well as respiration genes (HAP4, COX6, and CYC1), is increased following a shift from glucose to ethanol. Rds2 both activates the expression of positive regulators and represses the expression of negative regulators of gluconeogenesis. Finally, we show that Snf1-dependent phosphorylation of Rds2 occurs upon an ethanol shift. Altogether, our data demonstrate that Rds2 has functions partially overlapping with those of Cat8 and that it is a major regulator of gluconeogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains.

The yeast strains used in this study are isogenic to BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) (7). The RDS2 ORF was N-terminally tagged at its natural chromosomal location with a triple hemagglutinin (HA) epitope as described previously (2, 46). The tagging cassette was obtained by PCR using the oligonucleotides AATCAACACAAAATACACATATTTATATAAACTGACGAAATAATGAGGGAACAAAAGCTGGAG and TGTTTTAAAAGCCTTACTGGCTCGTTTTACACCACTGTTTGCTGATAGGGCGAATTGGGTACC with the plasmid p3XHA as a template. The nucleotides in boldface correspond to the start codon. The correct integration and sequence of the HA epitope were confirmed by gene-specific PCR and DNA sequencing of the PCR product. Expression of tagged Rds2 was verified by Western blotting. The tagged Rds2 protein was functional, since the strain grew similarly to the wild-type strain on plates containing the antifungal drug ketoconazole (data not shown).

The HA-RDS2 Δsnf1 and HA-RDS2 Δcat8 strains were generated by homologous recombination by replacing the ORF of SNF1 or CAT8 with the KanMX4 cassette amplified by PCR from the Δsnf1 (using oligonucletotides GAAATTGTTTCAGTGTCATTG and GTTTACTTTATACAAAGGG) or Δcat8 (using oligonucletotides CTCCCCTTTAAACCTGTGATA and GCTGTTCATAAGGTGAACGAA) deletion strain (51).

Gene induction conditions and primer extension analysis.

Cells were routinely grown in YEPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose). For glucose derepression experiments, cells were grown overnight in YEPD, diluted 30 times in YEPD medium, and cultured to mid-log phase (an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.8 to 1.2). The cells were then spun at 3,000 rpm, washed twice with water, and transferred to YEP medium containing 3% ethanol or to YEPD (control) medium and grown for an additional 3 h. For primer extension analysis, 20 to 40 micrograms of total RNA was used in the assays, which were performed as described previously (31). The DNA sequences of the oligonucleotides used for primer extension analysis are given in Table 1. For RNA loading controls, 20 micrograms of total RNA was run on agarose-formaldehyde gels.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for analysis by primer extension, ChIP, or EMSA

| Oligonucleotide | DNA sequence |

|---|---|

| Primer extension analysis | |

| RDS2 | GCCTTACTGGCTCGTTTTACACC |

| PCK1 | GGAAGTAGATCCTACTGTAGC |

| FBP1 | GGTATCAAACCCTTCGGTAGAGT |

| ICL1 | GCTTGTAAAGCTGCAAAATCGTTC |

| IDP2 | GCTCATCGCCGTCCATTTCCAC |

| GID8 | GCTGCAAGATCCGCTCTTCGTG |

| LSC2 | GCCCACACTTTGAAATTAGGGATA |

| MLS1 | GCTCCTTATCAACATCCACCAGT |

| PFK27 | GGAAGTCAAATATCCATCGTGAGA |

| VID24 | GTCACAGCTTTGGGTTTCTCCG |

| ChIP analysis | |

| FBP1 | CTACCAACTGAGCTAACAAGG and CTTGCGTTGGCTCTTACGCC |

| LSC2 | TCTCTCCAACTGTATGAGGAC and GGACTATCGCTCTATAGTCAC |

| MAE1 | CCTAGGCGGTTTAAATCGGAT and CGAAGCTGGACACAATATACG |

| PCK1-1 | CACTGAAGCTCCGGGTATTTT and GGAAAGGCTGTTGGTTATCTG |

| PCK1-2 | ATCGGAATATCCCACACGATC and GCCCTTTATCCGCCTATCCA |

| PDC1 | AGAACAATTTTGTGTTGTTACGG and CCCAAATCTGATTGCAAGGAG |

| EMSA | |

| PCK1-1A | TCGAACGGGTGAATGGAGATCTGG and TCGACCAGATCTCCATTCACCCGT |

| PCK1-1B | TCGAACAGGTGAATGGAGATCTGG and TCGACCAGATCTCCATTCACCTGT |

| PCK1-1C | TCGAACGGGTGAATAGAGATCTGG and TCGACCAGATCTCTATTCACCCGT |

| PCK1-2A | TCGACCGAGCTTCCTTTCATCCGG and TCGACCGGATGAAAGGAAGCTCGG |

| FBP1-2A | TCGACCGGACGGATGGAATCGCCG and TCGACGGCGATTCCATCCGTCCGG |

| FBP1-2B | TCGACCAGACGGATGGAATCGCCG and TCGACGGCGATTCCATCCGTCTGG |

| FBP1-2C | TCGACCGGACGGATAGAATCGCCG and TCGACGGCGATTCTATCCGTCCGG |

| FBP1-1A | TCGAGCGGACACCCGGAGTTATGC and TCGAGCATAACTCCGGGTGTCCGC |

ChIP.

Wild-type (BY4741), HA-RDS2, HA-RDS2 Δsnf1, and the HA-RDS2 Δcat8 strains were grown as described above. In parallel, cells from these strains were also grown in YEPD (repressive conditions). ChIP assays were performed as described by Larochelle et al. (29) with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were grown in YEPD to an OD600 of 0.8 to 1.2, washed twice in water, and transferred to YEP medium containing 2% glucose or 3% ethanol and grown for 3 h. Equal amounts of whole-cell extract were first adjusted according to the final OD600s of individual strains (0.5 ml/OD600 unit). Five hundred microliters of whole-cell extract was incubated with anti-HA antibody (Roche) coupled with magnetic beads (Dynal). Following immunoprecipitation and cross-link reversal, DNA was purified and used for genome-wide location analysis (ChIP-chip), gene-specific ChIP analysis, or quantitative PCR (QPCR). QPCR was performed with an Mx3005P PCR machine (Stratagene). The sequences of the oligonucleotides used for ChIP analysis are given in Table 1. Labeling of DNA for ChIP-chip analysis was performed as previously described (29). The microarrays used for ChIP-chip contained PCR products specific for each promoter and each ORF in the yeast genome. A detailed description of the microarrays can be found at http://www.ircm.qc.ca/microsites/francoisrobert/en. Hybridization and data analysis were performed as previously described (29).

Western blot analysis of Rds2 and λ protein phosphatase treatment.

Wild-type, HA-RDS2, and the HA-RDS2 Δsnf1 strains were grown in medium containing 2% glucose (repressive conditions) until mid-log phase, washed twice with water, and grown for 3 h in YEP medium with either 2% glucose or 3% ethanol. The cells were pelleted and washed with ice-cold water. Proteins were isolated and immunoprecipitated as described previously (1) with a few modifications. The IP-1 buffer (33) also contained phosphatase inhibitors: 10 mM NaF and 2 mM sodium orthovanadate. Protein extracts (1.25 mg) were enriched for HA-Rds2 after the 2-h incubation with 2.5 or 5 μl of HA antibody (HA probe [Y-11]; sc-805; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4°C. The immunoprecipitated proteins were incubated with 50% protein G-Sepharose slurry for 2 h at 4°C. The samples were then washed five times with the IP-1 buffer without protease inhibitors. Prior to being loaded, the proteins were dissociated from the beads by boiling them at 100°C for 3 min in 40 μl of 6× Laemmli buffer. Samples were run on an 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and visualized by immunoblotting them with a goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (heavy and light)-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Bio-Rad). Samples used for the λ protein phosphatase treatment were processed similarly, except that after the IP-1 washes, 20 μl of Tris-MnCl2 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM MnCl2) was added to the immunoprecipitated proteins bound to the beads. Samples were treated with 200 units of λ phosphatase (New England Biolabs) in the presence or absence of 0.1 mM Na3VO4, a specific λ protein phosphatase inhibitor, and incubated for 1 h at 30°C with occasional shaking. The untreated samples were used as controls. The immunoprecipitated proteins were then washed twice with the IP buffer without protease inhibitors and released from the beads by boiling them in 40 μl of 6× Laemmli buffer.

Protein expression and EMSA.

The DNA binding domain of Rds2 was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides GAAGATCTATGTCAGCAAACAGTGGTGT and GACTACCAATTGACTGCTGGAACTTAGTGATG, while oligonucleotides CGGGATCCATGGCAAATAATAATTCTGA and GGAATTCAGATATTTGTAGAAG were used for Cat8. Genomic DNA isolated from strain BY4741 was used as a template for PCR. The PCR products were cut with BglII and MunI for Rds2 or BamHI and EcoRI for Cat8 and subcloned into the bacterial expression vector pGEX-f (23) cut with BamHI and EcoRI. The DNA binding domains of Rds2 (amino acids 1 to 157) and Cat8 (amino acids 1 to 177) were expressed as glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins as described previously (23). Following purification, the glutathione S-transferase moiety was removed by thrombin cleavage and the resulting proteins were used in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) as described previously (23). The probes for EMSA were obtained by annealing oligonucleotidess and filling in with Klenow and dGTP, dTTP, dATP, and [32P]dCTP. The oligonucleotides used as probes are given in Table 1.

RESULTS

Rds2 binds to the promoter of the PCK1 gene, encoding an essential enzyme for gluconeogenesis.

Rds2 is a member of the Gal4 family of zinc cluster proteins that act as transcriptional regulators (32). We have previously shown that deletion of RDS2 sensitizes cells to the cell wall-perturbing agent calcofluor white and the antifungal drug ketoconazole. Depending on the strain background, removal of RDS2 results in a growth defect on nonfermentable carbon sources (2, 3). To learn more about the function of this zinc cluster protein, we performed genome-wide location analysis of Rds2 using the ChIP-chip approach. For this purpose, Rds2 was N-terminally tagged at its natural chromosomal location with a triple HA epitope. HA-Rds2 conferred resistance to ketoconazole similar to that with the untagged factor, suggesting that HA-Rds2 is fully functional (data not shown). ChIP-chip experiments were initially performed with cells grown in rich medium containing glucose (YEPD), and location analysis was determined with microarrays covering both promoters and coding regions (see Materials and Methods). As expected, binding enrichment of HA-Rds2 (compared to the untagged protein) was primarily observed in promoter regions (data not shown).

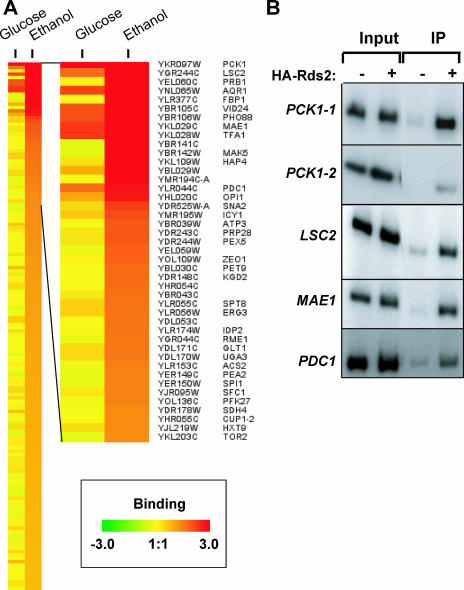

We identified a number of promoters that were occupied by Rds2 (P < 0.005) (Fig. 1A and Table 2). They correspond to genes encoding metabolic enzymes (e.g., PCK1, MAE1, PDC1, and LSC2) and genes with various functions (e.g., AQR1 and OPI1). The results were confirmed by standard ChIP assays (Fig. 1B and data not shown). Interestingly, the strongest Rds2 binding was observed in the promoter region of PCK1 (enrichment ratio of greater than 32). The PCK1 gene encodes phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, an important and well-conserved enzyme involved in an early step in gluconeogenesis.

FIG. 1.

(A) Promoters bound by Rds2 with cells grown in the presence of glucose or ethanol. The enlarged view shown on the right depicts genes bound by Rds2, including systematic ORF names and gene names (when available). Rds2 bound all depicted promoters with a P value of <0.005 under glucose and/or ethanol conditions. (B) Confirmation of ChIP-chip results by standard ChIP analysis of selected genes. Experiments were performed with untagged (−) or HA-tagged (+) Rds2. Signals obtained with either input DNA (Input) or immunoprecipitated DNA (IP) are shown. For the PCK1 gene, two overlapping regions of its promoter were analyzed. The PCK1-1 pair of oligonucleotides targets the promoter region located between −449 and −117 bp, while the PCK1-2 pair targets the segment −605 to −351 bp (the coordinates are relative to ATG). The negative control GND1 (which is not bound by Rds2) did not give any enrichment (data not shown). ChIP analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 2.

Promoters bound by Rds2a

| Systematic name | Gene | Function | Binding enrichmentb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | EtOH | |||

| YKR097W | PCK1 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | 32.8 | 20.5 |

| YGR244C | LSC2 | Beta subunit of succinyl-CoA ligase | 3.3 | 17.2 |

| YEL060C | PRB1 | Vacuolar protease B | 1.1 | 16.7 |

| YNL065W | AQR1 | Multidrug resistance transporter | 4.7 | 14.0 |

| YLR377C | FBP1 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase | 1.0 | 12.2 |

| YBR105C | VID24 | Peripheral vesicle membrane protein | 4.1 | 11.4 |

| YKL029C | MAE1 | Malic enzyme | 5.1 | 10.0 |

| YKL109W | HAP4 | Transcriptional activator of respiratory genes | 1.2 | 8.6 |

| YLR044C | PDC1 | Pyruvate decarboxylase | 3.3 | 6.7 |

| YHL020C | OPI1 | Transcriptional repressor of phospholipid biosynthetic genes | 2.0 | 6.4 |

| YMR195W | ICY1 | Protein that interacts with the cytoskeleton and is involved in chromatin organization and nuclear transport | 1.5 | 4.3 |

| YOL109W | ZEO1 | Peripheral-membrane protein of the plasma membrane that interacts with Mid2 | 1.0 | 3.6 |

| YDR148C | KGD2 | Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex dihydrolipoyl transsuccinylase component | 0.9 | 3.3 |

| YLR056W | ERG3 | C-5 sterol desaturase | 1.4 | 3.1 |

| YLR055C | SPT8 | Probable member of histone acetyltransferase SAGA complex transcription factor | 1.4 | 3.1 |

| YLR174W | IDP2 | NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| YGR044C | RME1 | Zinc finger protein negative regulator of meiosis | 0.8 | 3.0 |

| YLR153C | ACS2 | Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase | 0.8 | 2.8 |

| YJR095W | SFC1 | Succinate-fumarate transport protein | 1.2 | 2.8 |

| YOL136C | PFK27 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase | 0.9 | 2.7 |

| YDR178W | SDH4 | Succinate dehydrogenase membrane anchor subunit | 0.9 | 2.6 |

| YJL219W | HXT9 | Hexose permease | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| YKL203C | TOR2 | Putative protein/phosphatidylinositol kinase involved in signaling activation of translation initiation, distribution of the actin cytoskeleton, and meiosis | 0.8 | 2.5 |

| YNR001C | CIT1 | Citrate synthase | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| YMR135C | GID8 | Involved in proteasome-dependent catabolite inactivation of FBPase | 1.2 | 2.4 |

| YNL117W | MLS1 | Carbon-catabolite-sensitive malate synthase | 0.9 | 2.3 |

| YHR051W | COX6 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit | 0.9 | 2.2 |

| YPR074C | TKL1 | Transketolase 1 | 0.9 | 2.1 |

| YAR035W | YAT1 | Carnitine acetyltransferase | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| YJR048W | CYC1 | Iso-1-cytochrome c | 1.4 | 2.0 |

| YJL089W | SIP4 | Transcriptional activator that binds to the CSRE of gluconeogenic genes | 0.8 | 1.7 |

P < 0.005 under at least one condition.

Enrichment values for ChIP-chip analysis performed with cells grown with glucose or ethanol (EtOH) as described in Materials and Methods.

Rds2 targets are genes for gluconeogenesis, the TCA cycle, and glucose metabolism.

Given that our genome-wide location analysis in glucose-containing medium revealed very strong binding of Rds2 to the PCK1 promoter, we hypothesized that the targets of Rds2 also include other gluconeogenic genes. To test this possibility, additional ChIP-chip analyses were performed with cells grown in the presence of ethanol (see Materials and Methods). We observed increased binding for a majority of Rds2 target genes previously identified under glucose conditions (Table 2). Importantly, enhanced binding of Rds2 to the promoters of gluconeogenic/glycolytic genes was observed, as exemplified by the genes FBP1, PFK27, VID24, and GID8.

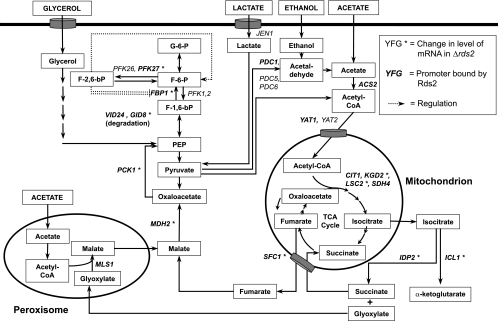

The FBP1 gene encodes a key gluconeogenic enzyme named fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase) that acts in this pathway to dephosphorylate fructose-1,6-bisphosphate to yield fructose-6-phosphate (see Fig. 6). PFK27 encodes 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase, which catalyzes the synthesis of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate from fructose-6-phosphate at the expense of ATP (see Fig. 6). The metabolite fructose-2,6-bisphosphate has been proposed to serve as an allosteric activator of the glycolytic enzymes phosphofructokinases (Pfk1 and Pfk2), as well as an inhibitor of FBPase, although the exact mechanism responsible for the inhibition is not known (22, 35). VID24 encodes a peripheral membrane protein found at the vacuole import and degradation (Vid) vesicles involved in the transport of proteins to the vacuole for degradation. The Vid complex is involved in the degradation of FBPase and malate dehydrogenase via the vacuole- and proteasome-dependent pathways (11, 24, 41). GID8 encodes a protein that is involved in proteasome-dependent degradation of FBPase (41). In addition, binding of Rds2 is observed at promoters of genes of the TCA cycle (CIT1, KGD2, LSC2, and SDH4), the pyruvate branch point (ACS2 and PDC1), the glyoxylate cycle (MDH2 and MLS1), metabolism (e.g., IDP2, MAE1, and TKL1), transport (e.g., YAT1, SFC1, AQR1, and HXT9), respiration (HAP4, COX6, and CYC1), and other important cellular processes (Fig. 1A and Table 2). In summary, our results show that Rds2 is bound to the promoters of many genes involved in glucose metabolism when assayed with a nonfermentable carbon source.

FIG. 6.

Rds2 target genes in the pathway of glucose metabolism. Important genes for glucose metabolism and various metabolites are shown. The nomenclature for genes and various arrows is given in the box in the top right corner. For example, an asterisk indicates genes whose expression is affected by deletion of RDS2, and genes bound by Rds2 are in boldface characters.

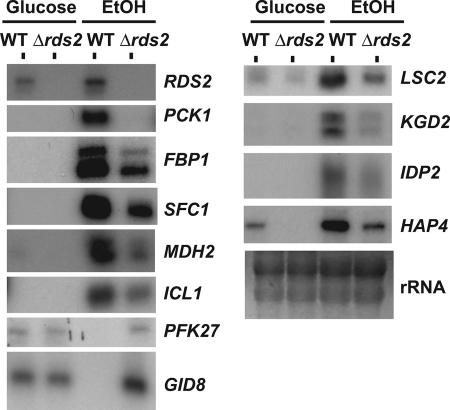

Rds2 regulates the expression of gluconeogenic genes.

It is well established that the expression of gluconeogenic genes is strongly repressed by glucose while it is maximally induced in the absence of the sugar, such as during the diauxic shift or upon transition from a medium containing glucose to a medium containing a nonfermentable carbon source (4, 47). Given the ChIP-chip results obtained with Rds2, we examined its possible role in the regulation of gluconeogenic-gene expression. Wild-type and Δrds2 strains were grown in YEP medium containing 2% glucose until they reached the mid-log phase of growth. The cells were then washed twice with water and transferred to fresh YEP medium containing 3% ethanol. RNA was isolated for analysis by primer extension. As expected, PCK1 mRNA levels were greatly increased following a shift to a nonfermentable carbon source (Fig. 2). Importantly, expression of PCK1 was greatly dependent on the presence of Rds2. We also observed a similar effect for FBP1, another gluconeogenic gene, as well as for other genes whose transcription is subject to glucose-mediated repression (see below). Thus, our results strongly suggest a direct role for Rds2 in regulating gluconeogenesis.

FIG. 2.

Rds2 controls the expression of genes identified by ChIP-chip analysis. Primer extension analysis of selected genes was performed with a wild-type (WT) strain and an RDS2 deletion strain. The strains were grown in the presence of glucose or ethanol (EtOH) prior to RNA isolation (see Materials and Methods). rRNA is shown as a loading control.

Deletion of RDS2 resulted in decreased mRNA levels for the TCA cycle genes LSC2, KGD2, and SFC1 and the respiratory genes HAP4 and COX6 (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Expression of HAP4, encoding an important transcription factor for the regulation of respiratory-gene expression (16), was increased following an ethanol shift (Fig. 2), a result expected from previous studies (13). Interestingly, expression of this gene was greatly reduced upon deletion of RDS2 (Fig. 2). Conversely, RDS2 deletion also led to increased RNA levels for PFK27 and GID8 when assayed in ethanol, while no effect was observed with cells grown in the presence of glucose. As stated above, PFK27 encodes a key glycolytic enzyme, while GID8 is involved in degrading the FBP1 gluconeogenic-gene product. Repression of the expression of these two genes by Rds2 under ethanol provides an additional mechanism for selective activation of gluconeogenesis over glycolysis. In the presence of ethanol, Rds2 was also strongly bound to the promoter of the gene PRB1, which encodes a vacuolar protease B. Expression of this gene was induced by ethanol, but we did not observe any effect on its mRNA level upon RDS2 removal (data not shown). RDS2 redundancy with other transcription factors may contribute to the lack of any large observable effects on mRNA levels. Alternatively, Rds2 may regulate these genes under conditions that were not tested. Nevertheless, our results show that Rds2 is a key regulator of the expression of gluconeogenic genes.

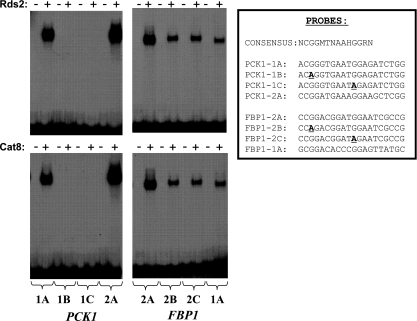

Rds2 binds in vitro to CSREs.

ChIP-chip experiments showed that Rds2 is associated with a number of promoters. We were interested in determining if Rds2 binds directly to DNA and, if so, in determining the DNA elements recognized by the protein. We focused on the PCK1 and FBP1 genes. Proft et al. (37) have systematically characterized the promoter of PCK1 and identified two UAS elements (UAS1 and UAS2) within it. Similarly, two UAS elements were also identified within the FBP1 promoter (12). The DNA binding domain of Rds2 was expressed in bacteria, purified, and used in an EMSA. A series of probes spanning the PCK1 promoter from −610 bp to −520 bp (relative to ATG) was used to map putative binding sites for Rds2. Our results demonstrate that Rds2 recognizes a CSRE corresponding to UAS1 of PCK1 (data not shown). To confirm that Rds2 does recognize a CSRE, EMSAs were performed with wild-type and mutant probes using Rds2 or, as a positive control, Cat8 (Fig. 3). An Rds2-DNA complex was observed when a probe containing a CSRE was used (Fig. 3, left, probe 1A). Mutating nucleotides important for in vivo activity of the UAS element (42) completely abolished binding of Rds2 in vitro (Fig. 3, left, probes 1B and 1C). Similar results were obtained with Cat8 (Fig. 3, bottom left). In addition, both Rds2 and Cat8 bound to a CSRE found in UAS2 of PCK1 (Fig. 3, left, probe 2A). Experiments were then performed with CSREs located in UAS1 and UAS2 of FBP1. Again, both Rds2 and Cat8 bound to a CSRE (located in UAS2), except that mutations similar to those introduced into the UAS1 of PCK1 reduced (but did not abolish) binding of Rds2 or Cat8 (Fig. 3, right, probes 2B and 2C). Finally, Rds2 and Cat8 bound weakly to UAS1 of FBP1 (Fig. 3, right, probe 1A). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that Rds2 recognizes CSREs. In other words, Rds2 and Cat8 (and Sip4) recognize highly related DNA motifs.

FIG. 3.

Rds2 binds in vitro to the promoters of the PCK1 and FBP1 genes. The purified DNA binding domains of Rds2 (top) and Cat8 (bottom) were used in an EMSA with the probes indicated along the bottom. The sequences of wild-type and mutant probes are indicated on the right, along with a consensus CSRE (42). The sequences are complementary to previously reported CSREs to highlight the conserved CGG triplet. Mutations are in boldface and underlined. M = A or C; H = A, C, or T; R = G or A. PCK1-1, CRSE1 of PCK1 (located at −561 to −542 bp); PCK1-2, CSRE2 of PCK1 (located at −470 to −489 bp); FBP1-1, CRSE1 of FBP1 (located at −433 to −414 bp); FBP1-2, CSRE2 of FBP1 (located at −505 to −486 bp). All positions are relative to the ATG codon (12, 37).

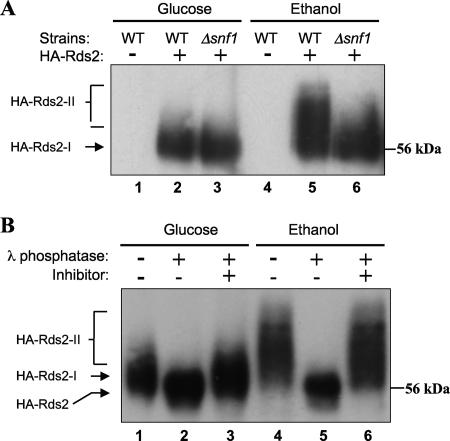

Rds2 phosphorylation is mediated by the Snf1 kinase.

Growth on nonfermentable carbon sources results in an important reprogramming of gene expression, including several genes encoding transcriptional regulators responsible for response to decreased glucose availability (13). For example, CAT8, SIP4, and HAP4 expression is increased in response to a diauxic shift (13, 47). However, Cat8 activation occurs at the posttranslational level via phosphorylation by the Snf1 kinase (40). We wished to determine at which level RDS2 is regulated under these conditions. Our results showed that RDS2 expression is not subjected to major glucose repression. RDS2 mRNA levels were only moderately induced following the ethanol shift (Fig. 2).

Since expression of RDS2 was not affected during glucose repression, we explored the possibility that Rds2 is posttranslationally regulated. The involvement of the Snf1 kinase as a posttranslational regulator of gluconeogenesis is well established (4, 8, 47). This activity is exemplified by the phosphorylation of the positive regulators Cat8 and Sip4, as well as the negative regulator Mig1, in response to glucose starvation. Phosphorylation of Cat8 correlates with increased expression of target genes, suggesting that this posttranslational modification is pivotal for Cat8 activation. These examples led us to further investigate the putative role of Snf1 in Rds2 activation by phosphorylation. Extracts were prepared from various strains grown in the presence of either glucose or ethanol and used for immunoprecipitation with an HA antibody, followed by Western blot analysis. With extracts prepared from cells grown in the presence of glucose, a band corresponding to HA-Rds2 could be seen at the expected molecular mass, while no signal was obtained using an extract prepared from a strain expressing an untagged Rds2 protein (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 4). In the presence of glucose, expression of tagged Rds2 in a Δsnf1 background did not alter HA-Rds2 mobility (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 2 and 3). Growth with ethanol as the sole carbon source resulted in a mobility shift of HA-Rds2 that was prevented by removal of SNF1 (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 5 and 6). These results suggest that Rds2 is phosphorylated by the Snf1 kinase upon a shift from glucose to ethanol. We confirmed that the altered mobility of Rds2 is due to phosphorylation by subjecting immunoprecipitated extracts to treatment with λ phosphatase. The mobility of HA-Rds2 obtained from cells exposed to ethanol decreased following λ phosphatase treatment (Fig. 4B, lanes 4 and 5). This effect was abolished upon addition of phosphatase inhibitors (Fig. 4B, lane 6). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the ethanol-induced altered mobility of Rds2 is due to its phosphorylation by the Snf1 kinase. Interestingly, a band corresponding to the HA-tagged Rds2 shifted slightly to a more slowly migrating form when the sample was treated with phosphatase in the absence of the phosphatase inhibitor (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 to 3). Thus, it appears that Rds2 is also phosphorylated prior to the glucose-to-ethanol shift. Therefore, growth in the presence of glucose or ethanol results in differential phosphorylation of Rds2.

FIG. 4.

Rds2 is phosphorylated by the Snf1 kinase. (A) Extracts were prepared from wild-type (WT) or SNF1 deletion (Δsnf1) cells grown in the presence of glucose or ethanol as indicated. The strains expressed either HA-Rds2 (+) or untagged Rds2 (−). Immunoprecipitation of HA-Rds2 was performed on extracts, followed by Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibody, as described in Materials and Methods. HA-Rds2-I and HA-Rds2-II refer to the phosphorylated and the hyperphosphorylated forms of HA-Rds2, respectively. (B) Extracts prepared from HA-Rds2-expressing wild-type cells, grown in glucose or ethanol, were treated with λ phosphatase and phosphatase inhibitor as indicated. Treatment was carried out as described in Materials and Methods.

Snf1 and Cat8 are required for binding of Rds2 to a target gene.

Snf1 phosphorylates both Rds2 and Cat8, and these modifications correlate with the induction of transcription of gluconeogenic genes, such as PCK1 and FBP1, that are common targets for these two transcriptional regulators. We wished to further investigate the roles of Snf1 and Cat8 in the binding of Rds2 to promoters that are recognized by both transcriptional regulators. We hypothesized that if Snf1 or Cat8 was required for Rds2 binding, deletion of either of the genes would result in decreased binding of Rds2. Either the SNF1 or the CAT8 gene was deleted from the previously described strain expressing HA-Rds2. Our ChIP analysis using QPCR showed that Snf1 and Cat8 affect Rds2 binding to its target promoters to various extents. For example, at PCK1, Rds2 binding was still significant upon removal of the SNF1 gene or the CAT8 gene (Fig. 5, lanes 1 to 3). Since Rds2 binds to the PCK1 promoter even in the presence of glucose (Table 2), phosphorylation of Rds2 may not be required for its binding. Hence, Rds2 binding to this promoter appears to be constitutive and does not correlate with PCK1 promoter activity. For FBP1, the binding pattern of Rds2 differed. Unlike PCK1, binding of Rds2 to the FBP1 promoter was detected only following a shift to ethanol (Table 2). Moreover, binding of Rds2 to the FBP1 promoter was largely dependent on the presence of both Snf1 and Cat8 (Fig. 5, compare lanes 4 to 6). The requirement for Snf1 in Rds2 binding to this promoter emphasizes the importance of phosphorylation in mediating Rds2 activation. Our results suggest that the promoter context determines what factors are required for transcriptional regulation by Rds2.

FIG. 5.

Snf1 and Cat8 are required for binding of Rds2 to the FBP1 but not the PCK1 promoter. ChIP analysis of Rds2 at the PCK1 and FBP1 promoters was performed by QPCR analysis using various strains, as indicated. Open bar, wild-type strain; black bar, Δcat8 strain; hatched bar, Δsnf1 strain. Enrichment ratios were obtained by normalizing signals to input DNA and to an untagged strain. Standard deviations are shown as vertical lines with perpendicular ends.

DISCUSSION

Growth of yeast on a nonfermentable carbon source, such as ethanol, results in increased expression of genes encoding enzymes of the gluconeogenic pathway and the glyoxylate cycle (13). Transcription of metabolic genes in both pathways is subject to glucose-mediated repression. Glucose exhaustion results in the activation of the Snf1 kinase required for the inactivation of the repressor Mig1 and its release from the promoter of the regulatory gene CAT8 (8). Subsequently, the Snf1-dependent activator Cat8 binds to promoters of target genes, including the SIP4 regulatory gene, allowing transcriptional derepression. In addition to this transcriptional control, increased degradation of enzymes involved in glycolysis also plays a role in the regulation of gluconeogenesis, thus preventing the simultaneous activation of the two opposite pathways (4, 47).

In this study, we showed that Rds2 functions as a transcriptional regulator of gluconeogenic genes. The ChIP-chip approach was used to identify genes that are bound by Rds2. With cells grown in the presence of glucose, Rds2 bound to the promoters of genes involved in various cellular processes, such as glucose metabolism, transport, cell wall integrity, and transcription. This finding supports potential transcriptional regulatory roles of Rds2 in various pathways, in agreement with the multiple defective phenotypes displayed by cells lacking RDS2 (2, 3). Importantly, our ChIP-chip analysis revealed strong enrichment of Rds2 at the promoter of the PCK1 gene, encoding a key gluconeogenic enzyme. Given the localization of Rds2 in the promoter region of the PCK1 gene, we further investigated the role of this factor in gluconeogenesis. ChIP-chip experiments performed with ethanol revealed that, under these conditions, Rds2 binds to many additional promoters (Fig. 1A). These include other gluconeogenic genes, as well as genes involved in the TCA and glyoxylate cycles and glucose metabolism (Fig. 1A and Table 2).

Rds2 acts as both transcriptional activator and repressor.

We demonstrated that Rds2 regulates the expression of certain genes when cells are shifted to a nonfermentable carbon source (Fig. 2). In agreement with previous observations (13), no mRNA of gluconeogenic or glyoxylate genes was detected from cells grown in glucose while an ethanol shift led to a substantial increase in the expression of these genes. Rds2 is required for the maximum expression of the genes encoding central enzymes in the gluconeogenic pathway and the glyoxylate cycle (such as MDH2) required for utilization of nonfermentable carbons and glucose-6 phosphate production. Conversely, Rds2 also represses the expression of gluconeogenic negative regulatory genes (PFK27 and GID8).

The expression of PFK27 is induced by fermentable carbon sources, while its gene product, along with that of PFK26, is responsible for the synthesis of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (6). This metabolic compound allosterically inhibits the activity of FBPase and enhances the activities of the two glycolytic phosphofructokinases Pfk1 and Pfk2 (22). The activities of both Pfk26 and Pfk27 are also regulated by phosphoenolpyruvate, a metabolite product of the gluconeogenic pathway. Rds2 appears to play a dual role, since it represses PFK27 to prevent glycolysis while it positively controls the expression of the gluconeogenic gene FBP1. Similarly, Rds2 is a repressor of GID8 whose gene product is involved, in the presence of glucose, in the degradation of gluconeogenic enzymes, such as Pck1, Fbp1, and Mdh2 (Fig. 6). Gid8 functions in the proteasome-dependent degradation pathway (11, 24, 41). It is likely that the transcriptional repression of GID8 by Rds2 is necessary to prevent degradation of gluconeogenic enzymes during growth on ethanol. Thus, Rds2 mediates gluconeogenesis by acting as a positive and a negative transcriptional regulator. The importance of Rds2 in mediating glucose metabolism is further illustrated by the fact that it positively regulates expression of HAP4, which encodes an activator of respiration genes (16). Rds2 also binds to OPI1, whose gene product inhibits the activators Ino2 and Ino4, which control expression of genes for the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to inositol (10).

A CSRE is recognized by three different transcriptional regulators.

The transcriptional response to gluconeogenic carbon sources, such as ethanol, is mediated by the binding of the transcriptional regulators Cat8 and Sip4 to a cis-acting element called CSRE (5, 9, 43). These two gluconeogenic activators were thought to be the sole CSRE-dependent activators responsible for the activation of several glucose-repressible genes. However, we showed that the purified DNA binding domain of Rds2 also recognizes CSREs located in the promoters of the PCK1 and FBP1 genes (Fig. 3). The observation that Rds2, Cat8, and Sip4 can recognize the same DNA elements is reminiscent of the zinc cluster proteins Pdr1 and Pdr3, which are involved in controlling expression of drug resistance genes (27, 32). Both Pdr1 and Pdr3 bind to the same DNA element either as homo- or heterodimers (33). In contrast, the transcriptional regulators Leu3 and Uga3, two other member of the family of zinc cluster proteins, recognize highly related but distinct DNA sequences (36).

Why have three factors that all recognize a common target? It is possible that these regulators recognize subsets of CSREs with different affinities, allowing regulation of both common and distinct genes. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that mutant CSREs show differential activation by Cat8 and Sip4 (42). Rds2 and Cat8 have a limited set of common target genes (see below). Thus, preferential binding of Rds2 to a promoter would be facilitated by the presence of CSREs for which Rds2 has high affinity. Alternatively, other factors may increase the binding of Rds2 at some promoters. Interestingly, a large-scale two-hybrid analysis showed that Rds2 interacts with the putative zinc cluster protein encoded by YBR239C (25). Binding in vivo of Rds2 at the FBP1 promoter is largely dependent on Cat8, while binding of Rds2 at the PCK1 promoter shows little dependency on Cat8 (Fig. 5). This raises the possibility that Rds2 heterodimerizes with Cat8 at specific CSREs for fine tuning of gene expression. However, we do not have evidence for the formation of an Rds2-Cat8 heterodimer (N. Soontorngun and B. Turcotte, unpublished results).

Rds2 has functions distinct from and overlapping with those of Cat8 and Sip4.

The contributions of the zinc cluster proteins Cat8 and Sip4 to gluconeogenic-gene activation have been extensively studied (4, 8, 47). A ChIP-chip analysis was performed by Tachibana et al. to identify promoters recognized by Cat8 under high- and low-glucose conditions (48). Examination of genes bound by Rds2 and Cat8 provides important insight into their specific contributions. Rds2 and Cat8 appear to bind to distinct sets of promoters. When ChIP-chip data for Rds2 (as assayed in ethanol) and Cat8 (tested under low glucose) were compared, only 14 promoters were common to both Rds2 and Cat8. Importantly, some of these promoters belong to genes of the gluconeogenesis-related pathway (PCK1, FBP1, MDH2, YAT1, and SFC1). Many of the overlapping genes contain at least one CSRE in their promoters.

Rds2 also binds to the promoters of a number of additional genes whose expression is strongly induced during growth on nonfermentable carbon sources. These include many genes of oxidative and gluconeogenic metabolism, as depicted in Fig. 6. Transcription of TCA cycle genes is subject to glucose-mediated derepression (13). During the diauxic transition, their expression is induced by nonfermentable carbon sources and is coregulated with the transcription of gluconeogenic genes. In addition, cells lacking any of the TCA cycle genes show growth defects when grown on nonfermentable carbon sources. Interestingly, following the ethanol shift, we observed increased binding of Rds2 to the promoters of the TCA cycle genes CIT1, KGD2, LSC2, and SDH4. We also observed coregulated induction of the TCA cycle genes (as tested with LSC2 and KGD2) with the gluconeogenic genes. For example, LSC2 expression is induced by ethanol and is partially dependent on Rds2 (Fig. 2). In contrast, these genes are apparently not bound or regulated by Cat8 (20, 48). Thus, it appears that Rds2 plays a more general role than Cat8 or Sip4 in controlling genes for glucose synthesis. HAP4 is another notable example of a gene whose expression is regulated by Rds2. As stated above, Hap4 functions as an activator subunit of the heme-activated and glucose-repressed Hap2/3/4/5 CCAAT-binding complex (16). It has a global regulatory role in respiration, and its expression is increased during the diauxic shift (13). Interestingly, expression of HAP4 is reduced upon removal of RDS2 in both cells grown in glucose and cells grown in ethanol (Fig. 2). Thus, Rds2 not only controls genes encoding enzymes for glucose production, but also controls regulatory genes.

Mechanism of Rds2 activation.

Regarding the mechanism of Rds2 activation, our results showed that RDS2 expression is not subject to glucose repression, as RDS2 mRNA is detectable in glucose-grown cells (Fig. 2). In agreement with this result, no Mig1 consensus binding sites are found in the RDS2 promoter (data not shown). We observed only a modest increase in the RDS2 mRNA level following a shift to ethanol (Fig. 2). In contrast, the expression of CAT8 and SIP4 is negatively regulated by Mig1 and the corepressor complex Ssn6/Tup1 in the presence of glucose (8, 47). Our results show, as reported for Cat8, Sip4, and Mig1, that phosphorylation of Rds2 is dependent on the Snf1 kinase. Moreover, a large-scale in vitro study strongly suggested that Snf1 directly phosphorylates Rds2 (38). Several lines of evidence suggest that phosphorylation of Rds2 is responsible for its activation (Fig. 4). In ethanol-grown cells, a band corresponding to HA-Rds2 exhibits a mobility shift that correlates with the expression of gluconeogenic-gene targets of Rds2. Our results also show that Snf1 is responsible for this hyperphosphorylation of Rds2 under ethanol-inducing conditions, since the HA-Rds2 mobility shift is reduced in the Δsnf1 strain to an extent similar to that observed under glucose-repressing condition. Finally, λ phosphatase treatment resulted in a decreased mobility shift of HA-Rds2. Thus, the activities of all three gluconeogenic activators (Rds2, Cat8, and Sip4) are controlled by the master kinase Snf1.

Our results suggest that Rds2 is also phosphorylated under glucose-repressing conditions. Snf1 is unlikely to be involved in this modification, since a similar mobility shift is observed with the Δsnf1 strain (Fig. 4). In addition to Snf1, Ptacek et al. have identified a number of additional kinases that phosphorylate Rds2 in vitro (38). One of these enzymes may thus be responsible for phosphorylating Rds2 under glucose conditions, allowing regulation of a subset of genes. For example, AQR1, which is constitutively bound by Rds2, encodes a plasma membrane transporter of the major facilitator superfamily that confers resistance to various compounds, including the antifungal drug ketoconazole (49). Rds2 may regulate the expression of AQR1, providing a rationale for the azole sensitivity of a Δrds2 strain (2).

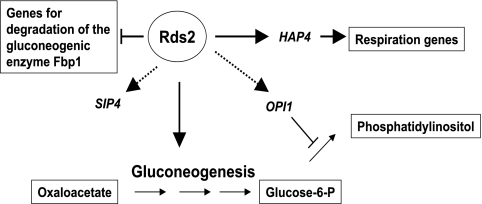

Rds2 is a major regulator of gluconeogenesis.

Studies have shown that many yeast transcriptional regulators have both distinct and overlapping functions (18, 29, 32). For example, Cat8 and Adr1 display binding at common promoters, as well as distinct ones (48). Similarly, Rds2 and Cat8 share a few common target promoters including the important gluconeogenic genes PCK1 and FBP1. However, our study showed that Rds2 plays a predominant role in regulating glucose metabolism in yeast (Fig. 7). Unlike Cat8 or Sip4, Rds2 also controls the expression of some TCA cycle genes, for example, KGD2, as well as negative regulators of gluconeogenesis, such as GID8. It also regulates the expression of the important regulatory gene HAP4, while binding of Rds2 is observed at the SIP4 promoter. In addition, Rds2 is also bound at the OPI1 gene involved in repressing genes such as INO1, which encodes a key enzyme for the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to phosphatidylinositol (10). Under ethanol conditions, Rds2 also represses genes involved in glycolysis, such as PFK27. In summary, our study identifies Rds2 as a pivotal regulator that both activates and represses key genes involved in glucose metabolism in S. cerevisiae.

FIG. 7.

Model for regulation by Rds2. Major targets of Rds2 are shown. An arrow indicates positive regulation by Rds2 of a given gene, while a line with a perpendicular end denotes negative regulation. A dotted arrow indicates a gene bound by Rds2 whose effect on expression has not been tested. See the text for more details.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Hellauer, Julie Huang, and Amelie Waldin for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to B.T. (grant 184053) and by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant to F.R. (MOP-82891). N.S. is supported by a studentship from the Thai government. S.D. holds a doctoral studentship from the Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montréal/CIHR Cancer Research Program. F.R. holds a CIHR New Investigator Award.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akache, B., S. MacPherson, M. A. Sylvain, and B. Turcotte. 2004. Complex interplay among regulators of drug resistance genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279:27855-27860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akache, B., and B. Turcotte. 2002. New regulators of drug sensitivity in the family of yeast zinc cluster proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277:21254-21260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akache, B., K. Q. Wu, and B. Turcotte. 2001. Phenotypic analysis of genes encoding yeast zinc cluster proteins. Nucleic. Acids Res. 29:2181-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnett, J. A., and K. D. Entian. 2005. A history of research on yeasts—9: regulation of sugar metabolism. Yeast 22:835-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bojunga, N., and K. D. Entian. 1999. Cat8p, the activator of gluconeogenic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, regulates carbon source-dependent expression of NADP-dependent cytosolic isocitrate dehydrogenase (Idp2p) and lactate permease (Jen1p). Mol. Gen. Genet. 262:869-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boles, E., H. W. H. Gohlmann, and F. K. Zimmerman. 1996. Cloning of a second gene encoding 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase in yeast, and characterization of mutant strains without fructose-2,6-bisphosphate. Mol. Microbiol. 20:65-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brachmann, C. B., A. Davies, G. J. Cost, E. Caputo, J. Li, P. Hieter, and J. D. Boeke. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14:115-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson, M. 1999. Glucose repression in yeast. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:202-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caspary, F., A. Hartig, and H. J. Schuller. 1997. Constitutive and carbon source-responsive promoter elements are involved in the regulated expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae malate synthase gene MLS1. Mol. Gen. Genet. 255:619-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, M., L. C. Hancock, and J. M. Lopes. 2007. Transcriptional regulation of yeast phospholipid biosynthetic genes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771:310-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang, M. C., and H. L. Chiang. 1998. Vid24p, a novel protein localized to the fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase-containing vesicles, regulates targeting of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase from the vesicles to the vacuole for degradation. J. Cell Biol. 140:1347-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Mesquita, J. F., O. Zaragoza, and J. M. Gancedo. 1998. Functional analysis of upstream activating elements in the promoter of the FBP1 gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 33:406-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derisi, J. L., V. R. Iyer, and P. O. Brown. 1997. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science 278:680-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vit, M. J., J. A. Waddle, and M. Johnston. 1997. Regulated nuclear translocation of the Mig1 glucose repressor. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:1603-1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzgerald, M. X., J. R. Rojas, J. M. Kim, G. B. Kohlhaw, and R. Marmorstein. 2006. Structure of a Leu3/DNA complex: recognition of everted CGG half sites by a Zn2Cys6 binuclear cluster protein. Structure 14:725-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gancedo, J. M. 1998. Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:334-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ha, N., K. Hellauer, and B. Turcotte. 1996. Mutations in target DNA elements of yeast HAP1 modulate its transcriptional activity without affecting DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:1453-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harbison, C. T., D. B. Gordon, T. I. Lee, N. J. Rinaldi, K. D. Macisaac, T. W. Danford, N. M. Hannett, J. B. Tagne, D. B. Reynolds, J. Yoo, E. G. Jennings, J. Zeitlinger, D. K. Pokholok, M. Kellis, P. A. Rolfe, K. T. Takusagawa, E. S. Lander, D. K. Gifford, E. Fraenkel, and R. A. Young. 2004. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature 431:99-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardie, D. G., D. Carling, and M. Carlson. 1998. The AMP-activated/Snf1 protein kinase subfamily: metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:821-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haurie, V., M. Perrot, T. Mini, P. Jeno, F. Sagliocco, and H. Boucherie. 2001. The transcriptional activator Cat8p provides a major contribution to the reprogramming of carbon metabolism during the diauxic shift in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 276:76-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedges, D., M. Proft, and K. D. Entian. 1995. CAT8, a new zinc cluster-encoding gene necessary for derepression of gluconeogenic enzymes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:1915-1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinisch, J. J., E. Boles, and C. Timpel. 1996. A yeast phosphofructokinase insensitive to the allosteric activator fructose 2,6-bisphosphate: glycolysis metabolic regulation allosteric control. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15928-15933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hellauer, K., M. H. Rochon, and B. Turcotte. 1996. A novel DNA binding motif for yeast zinc cluster proteins: the Leu3p and Pdr3p transcriptional activators recognize everted repeats. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6096-6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung, G. C., C. R. Brown, A. B. Wolfe, J. J. Liu, and H. L. Chiang. 2004. Degradation of the gluconeogenic enzymes fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and malate dehydrogenase is mediated by distinct proteolytic pathways and signaling events. J. Biol. Chem. 279:49138-49150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito, T., T. Chiba, R. Ozawa, M. Yoshida, M. Hattori, and Y. Sakaki. 2001. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4569-4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang, R., and M. Carlson. 1997. The Snf1 protein kinase and its activating subunit, Snf4, interact with distinct domains of the Sip1/Sip2/Ga183 component in the kinase complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:2099-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jungwirth, H., and K. Kuchler. 2006. Yeast ABC transporters: a tale of sex, stress, drugs and aging. FEBS Lett. 580:1131-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King, D. A., L. Zhang, L. Guarente, and R. Marmorstein. 1999. Structure of a HAP1-DNA complex reveals dramatically asymmetric DNA binding by a homodimeric protein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larochelle, M., S. Drouin, F. Robert, and B. Turcotte. 2006. Oxidative stress-activated zinc cluster protein Stb5 has dual activator/repressor functions required for pentose phosphate pathway regulation and NADPH production. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:6690-6701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lesage, P., X. Yang, and M. Carlson. 1996. Yeast SNF1 protein kinase interacts with SIP4, a C6 zinc cluster transcriptional activator: a new role for SNF1 in the glucose response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1921-1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma, J., and M. Ptashne. 1987. The carboxy-terminal 30 amino acids of GAL4 are recognized by GAL80. Cell 51:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacPherson, S., M. Larochelle, and B. Turcotte. 2006. A fungal family of transcriptional regulators: the zinc cluster proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:583-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mamnun, Y. M., R. Pandjaitan, Y. Mahe, A. Delahodde, and K. Kuchler. 2002. The yeast zinc finger regulators Pdr1p and Pdr3p control pleiotropic drug resistance (PDR) as homo- and heterodimers in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1429-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmorstein, R., M. Carey, M. Ptashne, and S. C. Harrison. 1992. DNA recognition by GAL4: structure of a protein-DNA complex. Nature 356:408-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller, S., F. K. Zimmermann, and E. Boles. 1997. Mutant studies of phosphofructo-2-kinases do not reveal an essential role of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate in the regulation of carbon fluxes in yeast cells. Microbiology 143:3055-3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noel, J., and B. Turcotte. 1998. Zinc cluster proteins Leu3p and Uga3p recognize highly related but distinct DNA targets. J. Biol. Chem. 273:17463-17468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proft, M., D. Grzesitza, and K. D. Entian. 1995. Identification and characterization of regulatory elements in the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene PCK1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246:367-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ptacek, J., G. Devgan, G. Michaud, H. Zhu, X. W. Zhu, J. Fasolo, H. Guo, G. Jona, A. Breitkreutz, R. Sopko, R. R. McCartney, M. C. Schmidt, N. Rachidi, S. J. Lee, A. S. Mah, L. Meng, M. J. R. Stark, D. F. Stern, C. De Virgilio, M. Tyers, B. Andrews, M. Gerstein, B. Schweitzer, P. F. Predki, and M. Snyder. 2005. Global analysis of protein phosphorylation in yeast. Nature 438:679-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahner, A., A. Scholer, E. Martens, B. Gollwitzer, and H. J. Schuller. 1996. Dual influence of the yeast Cat1p (Snf1p) protein kinase on carbon source-dependent transcriptional activation of gluconeogenic genes by the regulatory gene CAT8. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:2331-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Randez-Gil, F., N. Bojunga, M. Proft, and K. D. Entian. 1997. Glucose derepression of gluconeogenic enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae correlates with phosphorylation of the gene activator Cat8p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:2502-2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regelmann, J., T. Schule, F. S. Josupeit, J. Horak, M. Rose, K. D. Entian, M. Thumm, and D. H. Wolf. 2003. Catabolite degradation of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a genome-wide screen identifies eight novel GID genes and indicates the existence of two degradation pathways. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:1652-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roth, S., J. Kumme, and H. J. Schuller. 2004. Transcriptional activators Cat8 and Sip4 discriminate between sequence variants of the carbon source-responsive promoter element in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 45:121-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roth, S., and H. J. Schuller. 2001. Cat8 and Sip4 mediate regulated transcriptional activation of the yeast malate dehydrogenase gene MDH2 by three carbon source-responsive promoter elements. Yeast 18:151-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rottensteiner, H., A. J. Kal, B. Hamilton, H. Ruis, and H. F. Tabak. 1997. A heterodimer of the Zn2Cys6 transcription factors Pip2p and Oaf1p controls induction of genes encoding peroxisomal proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 247:776-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schjerling, P., and S. Holmberg. 1996. Comparative amino acid sequence analysis of the C6 zinc cluster family of transcriptional regulators. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4599-4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider, B. L., W. Seufert, B. Steiner, Q. H. Yang, and A. B. Futcher. 1995. Use of polymerase chain reaction epitope tagging for protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 11:1265-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schuller, H. J. 2003. Transcriptional control of nonfermentative metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 43:139-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tachibana, C., J. Y. Yoo, J. B. Tagne, N. Kacherovsky, T. I. Lee, and E. T. Young. 2005. Combined global localization analysis and transcriptome data identify genes that are directly coregulated by Adr1 and Cat8. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:2138-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tenreiro, S., P. A. Nunes, C. A. Viegas, M. S. Neves, M. C. Teixeira, M. G. Cabral, and I. Sa-Correia. 2002. AQR1 gene (ORF YNL065w) encodes a plasma membrane transporter of the major facilitator superfamily that confers resistance to short-chain monocarboxylic acids and quinidine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292:741-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vincent, O., and M. Carlson. 1998. Sip4, a Snf1 kinase-dependent transcriptional activator, binds to the carbon source-responsive element of gluconeogenic genes. EMBO J. 17:7002-7008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winzeler, E. A., D. D. Shoemaker, A. Astromoff, H. Liang, K. Anderson, B. André, R. Bangham, R. Benito, J. D. Boeke, H. Bussey, A. M. Chu, C. Connelly, K. Davis, F. Dietrich, S. W. Dow, M. El Bakkoury, F. Foury, S. H. Friend, E. Gentalen, G. Giaever, J. H. Hegemann, T. Jones, M. Laub, H. Liao, N. Liebundguth, R. W. Davis, et al. 1999. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285:901-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang, X. L., R. Jiang, and M. Carlson. 1994. A family of proteins containing a conserved domain that mediates interaction with the yeast Snf1 protein kinase complex. EMBO J. 13:5878-5886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang, L., and L. Guarente. 1994. The yeast activator Hap1—a Gal4 family member—binds DNA in a directly repeated orientation. Genes Dev. 8:2110-2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]