Abstract

The canonical Wnt pathway is necessary for gut epithelial cell proliferation, and aberrant activation of this pathway causes intestinal neoplasia. We report a novel mechanism by which the Sox family of transcription factors regulate the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. We found that some Sox proteins antagonize while others enhance β-catenin/T-cell factor (TCF) activity. Sox17, which is expressed in the normal gut epithelium but exhibits reduced expression in intestinal neoplasia, is antagonistic to Wnt signaling. When overexpressed in SW480 colon carcinoma cells, Sox17 represses β-catenin/TCF activity in a dose-dependent manner and inhibits proliferation. Sox17 and Sox4 are expressed in mutually exclusive domains in normal and neoplastic gut tissues, and gain- and loss-of-function studies demonstrate that Sox4 enhances β-catenin/TCF activity and the proliferation of SW480 cells. In addition to binding β-catenin, both Sox17 and Sox4 physically interact with TCF/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) family members via their respective high-mobility-group box domains. Results from gain- and loss-of-function experiments suggest that the interaction of Sox proteins with β-catenin and TCF/LEF proteins regulates the stability of β-catenin and TCF/LEF. In particular, Sox17 promotes the degradation of both β-catenin and TCF proteins via a noncanonical, glycogen synthase kinase 3β-independent mechanism that can be blocked by proteasome inhibitors. In contrast, Sox4 may function to stabilize β-catenin protein. These findings indicate that Sox proteins can act as both antagonists and agonists of β-catenin/TCF activity, and this mechanism may regulate Wnt signaling responses in many developmental and disease contexts.

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway is involved in many biological processes, ranging from embryonic development to stem cell maintenance in adult tissues, while the dysregulation of Wnt signaling is implicated in human tumorigenesis. The key effector of the canonical Wnt pathway is β-catenin, which forms complexes with T-cell factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) high-mobility-group (HMG) box transcription factors to stimulate the transcription of Wnt-responsive genes (7). While numerous studies have shown that β-catenin is regulated at many levels, less is known about the regulation of TCF/LEF transcription factors.

In the absence of a Wnt signal, levels of cytosolic β-catenin are kept low via the interaction of β-catenin with a protein complex including glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and Axin. The phosphorylation of β-catenin by the kinase GSK3β allows β-catenin to be ubiquitinated and targeted for degradation by the proteasome (1). The binding of a canonical Wnt ligand to the frizzled-lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 receptor complex results in the repression of GSK3β and the stabilization of β-catenin. Stabilized β-catenin accumulates in the nucleus, where it acts as a cofactor with the HMG box family of TCF/LEF transcription factors to regulate the expression of Wnt target genes, such as cyclin D1 and Cdx-1 (17, 22). Although the formation of a TCF-β-catenin complex is required for the activation of all Wnt target genes (36), Wnt signaling is involved in a wide array of biological processes, including cell proliferation, cellular transformation (14), and embryonic development (24), demonstrating that the output of this pathway is highly influenced by the cellular context.

Given that aberrant activation of the canonical Wnt pathway can lead to unrestricted cell division and tumor formation (12, 26, 28, 31, 40), it is not surprising that this pathway is antagonized by several different mechanisms. For example, several extracellular antagonists that inhibit ligand-receptor interactions have been described previously, including Dickkopf (Dkk), Cerberus, and the secreted frizzled-related proteins (10, 21, 34, 35). In many instances, Wnt signaling is kept in check by a negative-feedback loop in which β-catenin/TCF activity induces the transcription of its own negative regulators, Axin and Dkk1 (4, 20, 39). Finally, in the absence of activated β-catenin, TCF/LEF transcription factors keep Wnt target genes off via their interaction with members of the Grouch family of transcriptional repressors (4, 20, 39).

Structurally related to TCF/LEFs, several members of the Sox family of HMG box transcription factors, including Sox17, Sox3, Sox7, and Sox9, have also been implicated in repressing β-catenin activity by a mechanism that is not well understood (2, 48, 54, 55). In addition to acting as an antagonist, Sox17 cooperates with β-catenin to activate the transcription of its endoderm target genes in Xenopus laevis (44). These findings suggest that, dependent on the context, Sox proteins can utilize β-catenin as a cofactor or can antagonize β-catenin/TCF function. While the mechanism by which Sox proteins antagonize Wnt signaling is unknown, one possibility is that they compete with TCFs for binding to β-catenin (55).

Here, we report that Sox proteins expressed in normal and neoplastic gut epithelia can modulate canonical Wnt signaling and the proliferation of gastrointestinal tumor cells. While several Sox factors, including Sox17, Sox2, and Sox9, are antagonists of canonical Wnt signaling, others, such as Sox4 and Sox5, promote Wnt signaling activity. Gain- and loss-of-function analyses demonstrate that the Wnt antagonist Sox17 represses colon carcinoma cell proliferation while the agonist Sox4 promotes proliferation. In contrast to a proposed model in which Sox17 protein antagonizes Wnt signaling by competing with TCFs for β-catenin binding, we found that Sox17 interacts with both TCF/LEF and β-catenin and that Sox17 and TCF/LEF proteins interact via their respective HMG domains. Binding experiments suggest that Sox17, TCF, and β-catenin cooperatively interact to form a complex. In contrast, Sox4 can bind to either TCF/LEF or β-catenin alone but does not appear to cooperatively bind both proteins. Structure-function analyses indicate that Sox17 must bind directly to both β-catenin and TCF in order to antagonize Wnt signaling and that Sox17 DNA binding activity is not required. Lastly, functional studies show that Sox17 promotes the degradation of TCF/LEF and β-catenin proteins via a GSK3β-independent mechanism that can be blocked by proteasome inhibitors. In contrast, Sox4 may function to stabilize β-catenin protein. Together, these findings suggest that Sox transcription factors act in a novel pathway to modulate the stability of β-catenin/TCF proteins and regulate the proliferation of colon carcinoma cells. These results have important implications for how Sox proteins regulate the transcriptional output of Wnt signaling in many developmental and pathological processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructs.

The following constructs were previously used and described: pGEX-3X carrying genes encoding a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-β-catenin fusion protein; pcDNA6 carrying genes encoding human wild-type β-catenin and β-catenin with the S37A mutation [β-catenin(S37A)], human TCF4, mouse Lef1, mouse Sox10, Xenopus Sox17, and Sox3; and pcDNA1 carrying Xenopus Tcf3 (55). TCF-luciferase reporter plasmids (TOP-flash and FOP-flash) (17) were generously provided by Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). We subcloned the TCF4 cDNA into pGEX-3X to generate the TCF4-GST fusion protein. Full-length mouse Sox17 was amplified from embryonic day 7.5 mouse endoderm with Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen), cloned into pCIG (11), and sequenced. To generate V5-tagged Sox17, the cDNA was subcloned into pcDNA6, and to produce the GST fusion protein, Sox17 was subcloned into pGEX-3X. Mouse Sox2, Sox4, Sox6, Sox7, Sox9, and Sox18 were amplified from whole embryonic day 12.5 mouse cDNA with Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen), cloned into pcDNA6, and sequenced. Xenopus Sox5 was generated by PCR, and we obtained chick Sox11 from Hugh Woodland (University of Warwick, United Kingdom). Deletions in mouse Sox17 were generated using PCR, and point mutations in Sox17 were generated using the Gene Tailor site-directed mutagenesis kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). To generate the Sox17 reporter plasmid pH4X8-Luci, annealed oligonucleotides containing four additional copies of a Sox17 DNA binding site (15) were inserted into the XhoI site of the pH4X4-Luci reporter plasmid.

Cell culture, treatments, cell transfection with plasmids and siRNAs, and luciferase assays.

COS, 293T, and SW480 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone). Cells were plated into 12-well plates 24 h prior to transfection and were transfected with the TOP-flash plasmid (100 to 150 ng), a β-galactosidase or renilla plasmid (50 ng) as a transfection control, the gene encoding β-catenin(S37A) (100 ng), and the Sox plasmids listed above (100 to 800 ng) by using Fugene 6 (Roche) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The total amount of DNA was kept constant by adding empty-vector DNA. Cell lysates were prepared 24 to 48 h posttransfection, and luciferase activity was measured according to the luciferase assay system (Promega). Transfection efficiency was normalized using either β-galactosidase activity or renilla luciferase activity from the control plasmid. Experiments were done at least three times, and data from a representative example are shown. For small interfering RNA (siRNA) experiments, double-stranded Sox4 and Sox17 siRNAs and siRNA negative controls (Stealth RNA interference negative control med GC, catalog no. 12935-300, and BLOCK-iT Alexa Fluor red fluorescent control siRNA, catalog no. 147500-00) were obtained from Invitrogen. SW480 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in serum and antibiotic-free OptiMEM medium with a 1:1:1 mixture of Sox4 or Sox17 siRNAs at doses of 20, 50, and 100 nM. For all experiments, the siRNA control was used at the equivalent concentrations. The cells were harvested at 48 and 72 h after transfection. The transfection efficiency as measured using the BLOCK-iT Alexa Fluor red fluorescent control siRNA was estimated at 80 to 90% after 12 h (data not shown). A combination of three double-stranded Sox17 siRNA sequences was used (only the sense strand sequences are shown): no. 10620312/116668 B07, GCACGGAAUUUGAACAGUAUCUGCA; no. 10620312/116668 B09, UGCACUUCGUGUGCAAGCCUGAGAU; and no. 10620312/116668 B11, CGCGGUAUAUUACUGCAACUAUCCU. A combination of three double-stranded Sox4 siRNA sequences was used (only the sense strand sequences are shown): no. 10620312/116668 C01, GCAAACGCUGGAAGCUGCUCAAAGA; no. 10620312/116668 C03, UCAAAGACAGCGACAAGAUCCCUUU; and no. 10620312/116668 C05, GCGACAAGAUCCCUUUCAUUCGAGA. For protein stability and degradation experiments, leupeptin, lithium chloride, and chloroquine were purchased from Sigma. Epoxomicin was purchased from Calbiochem, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (1,000× stock), and diluted to 1× in culture medium. The final concentrations were as follows: epoxomicin, 0.1 μM; leupeptin, 100 μM; cholorquine, 25 μM; and LiCl, 40 mM.

For SW480 cell proliferation assays, we transfected cells by using a Lipofectamine-based Nucleofector technology kit (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). For colony assays, SW480 cells were transfected with pmax-GFP, pBABE-PURO, and either Sox17-pcDNA6 or Sox4-pcDNA6. Cells were plated at three different dilutions and allowed to recover overnight. Cells were then cultured in three different concentrations of puromycin (0.7, 1.5, and 3 μg/ml), and selection was continued for 5 days, at which time puromycin-resistant, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive colonies were counted. Only colonies containing ≥10 GFP-positive cells were counted. To monitor the total cell number, cells were trypsinized and GFP-positive cells were counted using a hemocytometer. Three wells of cells were counted for each time point and condition tested.

Immunohistochemistry and microscopy.

Paraffin sections (7 μm thick) were collected onto glass slides (Superfrost Plus; Fisher), and the slides were heated overnight at 60°C, dewaxed, and equilibrated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). We performed antigen retrieval by heating slides in a steam chamber in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6, for 20 min. Anti-Sox4 (Sigma; 1:500) and anti-Sox17 (1:500) (33) immunohistochemistry analysis was performed using tissue sections from wild-type CD1 mice or APCmin/+ mice, which carry a mutation in the APC gene that predisposes them to intestinal adenomas. After deparaffinization, rehydration, and antigen retrieval, tissues were blocked for 1 h using 5% normal goat serum in PBS-0.5% Triton X. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies diluted in blocking reagent. On the second day, slides were washed and incubated with goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted in blocking reagent (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were washed and incubated in ABC reagent (Vector Labs) for 30 min at room temperature. Instead of detecting the antigen with the traditional 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogen included in the ABC kit, fluorescence detection of antigens was carried out using the tyramide substrate amplification kit as described by the manufacturer (Molecular Probes). Tyramide-488 was used to produce fluorescent green immunostaining. Sections were counterstained with the red nuclear dye PoPro3 (Molecular Probes). A Leica DM IRB inverted microscope was used to capture digital images of GFP-expressing cells of immunofluorescently labeled sections.

SW480 cells were fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and washed extensively in 1× PBS. They were then blocked using 5% normal goat serum in PBS-0.5% Triton X. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. On the second day, cells were washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies directly conjugated to fluorophores.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were transfected with Sox17 (50 to 400 ng), β-catenin gene (100 ng), TCF4 (100 ng), and/or Lef1 (100 ng) constructs. Cell lysates were prepared 24 to 48 h posttransfection as described previously (55) and analyzed by standard Western immunoblotting procedures with the following antibodies: anti-V5-horseradish peroxidase (anti-V5-HRP; 1:4,000 [Invitrogen]), rabbit anti-β-catenin (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-activated β-catenin (1:1,000; Upstate Biotechnology), mouse antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) antibody (1:1,000; Roche), mouse anti-TCF4 (1:500; Upstate Biotechnology), rabbit anti-Sox4 (1:500; Sigma), mouse antitubulin (1:1,000; Sigma), guinea pig anti-Sox17 (1:1,000), affinity-purified rabbit anti-mouse/human Sox17 (1:5,000), goat anti-rabbit HRP (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch), goat anti-mouse HRP (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch), and rabbit anti-XTCF3 (1:3,000) (54).

In vitro protein binding assays.

GST-mouse Sox17, GST-TCF4, and GST-β-catenin were expressed in bacteria and purified using glutathione-coupled agarose resin. His-tagged Xenopus Sox17β and His-tagged Xenopus Sox17β consisting of amino acids 1 to 150 (see Fig. 4C) were expressed in bacteria and purified on Ni-agarose resin. β-catenin, TCF4, and LEF1 genes (in pcDNA6) and the Xenopus TCF3 gene (in pcDNA1) were transcribed with T7 polymerase, and the proteins were produced in TNT translation reactions (Promega). In vitro-translated proteins were incubated with GST or His fusion proteins coupled to agarose resin as described previously (55), and bound proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting using anti-V5-HRP or anti-HA-HRP antibody or by 35S labeling autoradiography.

FIG. 4.

Sox17 forms a stable, trimeric complex with TCF/LEF and β-catenin proteins. (A) Sox17 interacts with TCF3, TCF4, and LEF proteins. Sox17-GST beads pulled down in vitro-translated, V5 epitope-tagged TCF4, TCF3, and LEF1, and GST beads did not. (B) The interaction between Sox17 and β-catenin is enhanced in the presence of TCF4. Sox17 or TCF4 independently bound to β-catenin-GST beads but not to GST beads alone (panels 1 and 2). The binding of Sox17 to β-catenin-GST beads was enhanced in the presence of TCF4 (compare the ratios of input to bound Sox17 in the presence and absence of TCF4 [lanes marked by *]). β-catenin-interacting proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-V5 antibody. (C) The interaction between β-catenin (β-cat) and TCF3 is stabilized by Sox17 and requires a Sox17-β-catenin interaction. In vitro-translated, S35-labeled TCF3 protein (input) was incubated with β-catenin (myc tagged) alone or with increasing concentrations of purified His-tagged Xenopus Sox17β or His-tagged Xenopus Sox17 consisting of amino acids 1 to 150, which removed the β-catenin interaction domain (ΔC Sox17). β-catenin and its associated proteins were precipitated with an anti-myc antibody, and TCF3 protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. IP, immunoprecipitate. (D and E) Under high-stringency conditions, Sox17-GST beads would not efficiently pull down β-catenin. However, in the presence of TCF4 (D) or TCF3 (E), Sox17 was able to pull down β-catenin. This interaction depends on the β-catenin interaction domain of TCF3, which is deleted in the N terminus-lacking TCF3 protein (ΔN TCF3). +, present; −, absent.

Preparation of nuclear extracts and coimmunoprecipitations.

Approximately 109 SW480 cells were homogenized in 3.5 ml of cell lysis buffer (250 mM sucrose, 30 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, and 0.1% Triton X-100 with protease inhibitors). Nuclei were liberated from the cells by 15 gentle strokes of a tight-fitting pestle in a Dounce homogenizer and centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used as the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, and 0.5% Triton X-100 with protease inhibitors) and sonicated to lyse the nuclei and thoroughly shear the genomic DNA. The resulting extract was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used as the nuclear fraction. In all experiments, we verified the enrichment of the nuclear fraction with nuclear proteins by using an antihistone antibody (data not shown).

For coimmunoprecipitation, equal amounts of nuclear extract were precleared with 1 μg of rabbit preimmune serum and protein A-agarose for 1 h at 4°C. The extracts were then incubated for 4 h at 4°C with protein A-agarose and either 1 μg of a rabbit anti-Sox17 peptide antibody (44) or 1 μg of anti-HA antibody as a negative control. To demonstrate specific binding with anti-Sox17 antibody, 2 μg of a competing Sox17 peptide was included in the incubations. Immunoprecipitates were washed four times in nuclear lysis buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to anti-β-catenin immunoblotting.

Xenopus embryo culture and manipulations.

Two-cell-stage Xenopus embryos were microinjected with Sox17α1, Sox17α2, and Sox17β antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MO; 20 ng of each) as previously described (6), 20 ng of a β-catenin MO (13), or a synthetic mRNA encoding Xenopus Sox17β (10 pg). At stage 11 (according to a normal table of X. laevis development [29]), embryos were harvested and pooled in groups of three for each condition.

RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from embryonic tissue or cells by using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with RNase-free DNase (Roche). cDNA was synthesized with oligo(dT) primers. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and semiquantitative analysis were performed using the Opticon machine (MJ Research-Bio-Rad). The primers used in this study were as follows: human Sox17 forward, 5′-GAC GAC CAG AGC CAG ACC-3′, and human Sox17 reverse, 5′-CGC CTC GCC CTT CAC C-3′ (5); human Sox4 forward, 5′-TTC AGC AAC CAG CAT TC-3′, and human Sox4 reverse, 5′-TCC CTC TCT CTC GCT CTC TC-3′ (37); human cyclin D1 forward, 5′-AAT GAC CCC GCA CGA TT-3′, and human cyclin D1 reverse, 5′-GCA CAA GAC GCA ACG AAG G-3′ (49); human c-myc forward, 5′-GGT GAA GTA CAT GAA CTC AGG GC-3′, and human c-myc reverse, 5′-GGC TTT GAA TCT GCT GGA TTG-3′ (43); human β-tubulin gene forward, 5′-GAT ACC TCA CCG TGG CTG CT-3′, and human β-tubulin gene reverse, 5′-AGA GGA AAG GGG CAG TTG AGT-3′; Xnr3 forward, 5′-AAA TCC ATG TGA GCA CCG TTC-3′, and Xnr3 reverse, 5′-GCA TTC TCT GTC TCA TTC TGT G-3′; Hnf1β forward, 5′-GCA TAT GGC ACA GCA GCC ATT-3′, and Hnf1β reverse, 5′-CAC CAT GCT TGC AAA GGA CAC-3′; Edd forward, 5′-AGA ACG GAG ACT CAG ATC AAT-3′, and Edd reverse, 5′-TTA CTC ATT GCT CCC ACC ATC-3′; Plakoglobin forward, 5′-GCT CGC TGT ACA ACC AGC ATT C-3′, and Plakoglobin reverse, 5′-GTA GTT CCT CAT GAT CTG AAC C-3′; and ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) gene forward, 5′-GCC ATT GTG AAG ACT CTC TCC AAT C-3′, and ODC gene reverse, 5′-TTC GGG TGA TTC CTT GCC AC-3′. SYBR green dye (QIAGEN) was included in the PCR mix. For each experiment and primer pair, a dilution series of cDNA was included in order to generate a standard curve from which the amount of product in each sample was estimated at the log-linear amplification phase. These values were normalized to the level of expression of the ODC gene (53) or the β-tubulin gene, and the data are presented as a ratio of the expression of each gene to ODC or β-tubulin gene expression. In each experiment, samples with water alone or controls without reverse transcriptase were included and failed to give specific products. Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and results from a representative example are shown.

RESULTS

Sox factors can either repress or enhance β-catenin/TCF activity and are expressed in normal and neoplastic gut tissues.

We chose the intestinal epithelium as a model to study Sox17-Wnt interactions because of the well-established role of the Wnt pathway in this tissue and because it has recently been shown that the mRNA levels corresponding to several Sox transcription factors change during cancer progression in the gut (8, 32, 38). Given this link between Sox factors and Wnt signaling in gut tumorigenesis, we analyzed 11 different Sox factors for their ability to affect the canonical Wnt signaling pathway (Fig. 1A) and further analyzed the expression of two of them in normal and neoplastic gut tissues (Fig. 1B and C). In transfection experiments, we coexpressed individual Sox factors with activated, stabilized β-catenin [β-catenin(S37A)] (Fig. 1) and measured Wnt signaling activity by using the TOP-flash reporter plasmid. The activities of Sox factors fell into three categories. Sox2, Sox3, Sox9, Sox10, and Sox17 were strong antagonists of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Surprisingly, some Sox factors, including Sox4, Sox5, and Sox11, enhanced β-catenin activity. Other Sox factors, such as Sox6, had no impact on Wnt signaling activity. All of the expressed Sox proteins were detectable by Western blot analysis of transfected cell lysates, and none significantly altered TOP-flash activity in cells not cotransfected with β-catenin (data not shown).

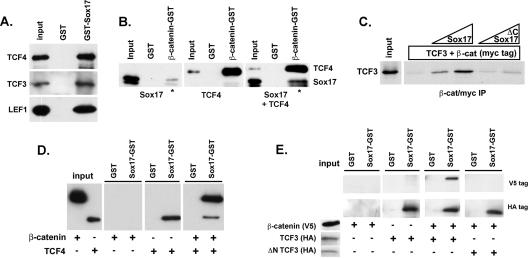

FIG. 1.

Different Sox factors are antagonists or agonists of the canonical Wnt pathway and are expressed in the normal and neoplastic gut. (A) Effect of different Sox family members on Wnt signaling activity. 293T cells (shown) and COS cells (not shown) were transfected with Sox2, Sox3, Sox4, Sox5, Sox6, Sox7, Sox9, Sox10, Sox11, Sox17, and Sox18 together with a TCF-luciferase reporter plasmid (TOP-flash) and an expression plasmid encoding a stabilized form of β-catenin (carrying the S37A mutation). Transfection with β-catenin(S37A) alone resulted in significant activation of the reporter plasmid. Sox2, Sox3, Sox7, Sox9, Sox10, and Sox17 repressed the β-catenin-mediated activation of TOP-flash, whereas Sox4, Sox5, and Sox11 enhanced β-catenin/Wnt activity. Data are shown as ratios of the activity in cotransfected cells to the activity in cells transfected with β-catenin(S37A) alone. Transfection with Sox factors without β-catenin(S37A) did not result in significant TOP-flash activity (data not shown). Letters above the bars denote the Sox subfamily. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means for replicate samples from two separate experiments. −, absent; +, present. (B) Analysis of published microarray data (8, 32, 38). The expression levels of the Wnt antagonists Dkk and Sox17 were reduced in seven of eight tumor samples relative to those in the normal gut samples. The levels of expression of several pro-Wnt signaling genes, Sox4, TCF4, and LEF1, and the Wnt target gene cyclin D1 (CCND1) were elevated in tumor samples relative to those in normal gut samples. The color scale for normalized transcript levels is as follows: red, high; yellow, moderate; and blue, low. (C) Sox4 and Sox17 proteins are expressed in the normal gut epithelium and in APCmin/+ tumors. In the small intestine, Sox17 and Sox4 proteins (green) are expressed in the nuclei of the epithelial cells (a duodenum sample is shown). The Sox4 expression domain is located predominantly in the crypt, whereas Sox17 protein is found throughout the crypt and villus. The right panels show adjacent sections from APCmin/+ tumors in which Sox17 and Sox4 proteins appear to be in mutually exclusive domains. Nuclei are stained with the red nuclear dye PoPro3. Scale bars in duodenum panels, 50 μm.

It has not previously been demonstrated that different Sox proteins act as antagonists or agonists of the canonical Wnt pathway. Given the role of this pathway in intestinal neoplasia, we reinvestigated whether the expression of Sox family members with different activities correlated with tumor progression by using published microarray data from APCmin/+ intestinal tumors (8, 32, 38). The microarray data indicate that Sox4 and Sox17 are two of the most differentially expressed Sox factors in APCmin/+ tumor tissue versus normal gut samples (Fig. 1B). Sox4 mRNA levels were significantly elevated in all eight tumor samples, and Sox17 mRNA levels were reduced in seven of eight tumor samples relative to those in the normal gut samples. Sox4 clustered with other Wnt pathway genes that showed elevated levels of expression in APCmin/+ tumor tissue, including cyclin D1 (CCND1), Lef1, and TCF4, consistent with the activated Wnt activity in these tumors. In contrast, Sox17 expression levels were down regulated in most tumor samples, and Sox17 clustered with other known Wnt antagonists, such as Dkk1. Immunohistochemical analysis of Sox4 and Sox17 in normal and APCmin/+ intestinal tissues revealed that both factors are expressed in the gut epithelium. In normal samples of duodenum, ileum, and jejunum tissue, Sox4 protein appeared to be more restricted to the crypts whereas Sox17 protein was present in both the crypts and villi (Fig. 1C, left panels). Moreover, in APCmin/+ tumors, Sox17 and Sox4 proteins appeared to be found in mutually exclusive domains when we stained adjacent tissue sections.

Sox17 and Sox4 have opposite effects on Wnt activity and the proliferation of colon carcinoma cells.

The fact that Sox17 represses Wnt signaling and is down regulated in Wnt-dependent tumors while Sox4 enhances Wnt signaling and is expressed at high levels in APCmin/+ tumors suggests that these transcription factors may play opposite functional roles in gut tumorigenesis. As a rapid way to investigate this idea, we examined the impact of Sox17 or Sox4 overexpression and loss of function on β-catenin/TCF activity and on the proliferation of SW480 cells. SW480 cells are transformed colon carcinoma cells that contain a mutant APC gene that results in high endogenous β-catenin/TCF activity as measured by a TOP-flash reporter assay (28, 30). Moreover, immunohistochemical analysis revealed endogenous Sox17 and Sox4 protein in SW480 cells (Fig. 2A). Sox17 protein was restricted to the nucleus, whereas Sox4 was present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. For gain-of-function analysis, we transfected SW480 cells with increasing levels of Sox17 or Sox4 plasmids. Sox17 caused a dose-dependent decrease in endogenous β-catenin/TCF activity, whereas Sox4 caused a dose-dependent increase in β-catenin/TCF activity (Fig. 2B and C). We investigated whether the Sox-mediated regulation of Wnt/β-catenin/TCF activity correlated with the proliferation of SW480 cells by using a colony formation assay (51). Consistent with its ability to repress Wnt activity, Sox17 expression caused a significant reduction in the number of SW480 cell colonies (Fig. 2D) but had no impact on apoptosis (data not shown). In addition, we observed a significant decrease in the absolute number of transfected SW480 cells that expressed Sox17 over the course of 4 days (data not shown). In contrast, Sox4 had the opposite effect, causing an increase both in colony numbers and in the average number of cells per colony (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, the cells transfected with Sox17 tended to be flatter and more adherent than cells transfected with Sox4, which were often rounder, smaller, and less adherent (Fig. 2D and E insets). These phenotypes are consistent with the possibility that Sox17 inhibits cellular transformation whereas Sox4 promotes it.

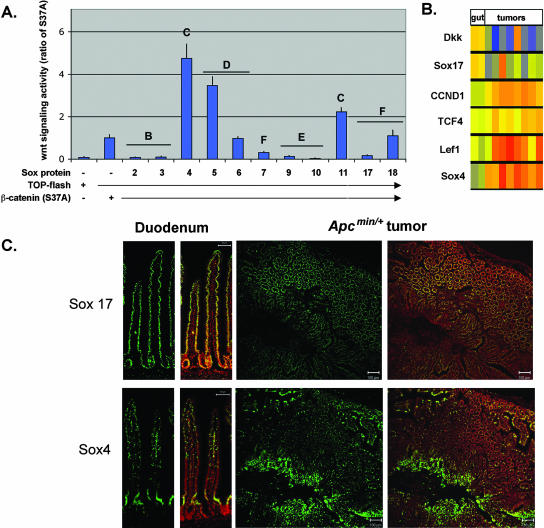

FIG. 2.

Sox17 and Sox4 have opposite effects on Wnt activity and proliferation of SW480 colon carcinoma cells. (A) Endogenous Sox17, Sox4, and β-catenin proteins are present in SW480 cells. (B) Sox17 represses endogenous Wnt signaling activity in colon carcinoma cells. Transfection with the TOP-flash reporter alone (lane 1) demonstrates that SW480 cells have high levels of endogenous Wnt/β-catenin/TCF activity. Cells cotransfected with increasing concentrations of a Sox17 expression plasmid (100 to 400 ng) showed dose-dependent reduction in endogenous Wnt activity (lanes 2 to 4). TOP-flash activity is expressed in relative light units that were normalized to the transfection efficiency by using a renilla plasmid. The results shown are representative of those from at least three independent experiments. −, absent. (C) Sox4 enhances endogenous Wnt signaling activity in colon carcinoma cells. SW480 cells that were cotransfected with increasing levels of a Sox4 expression plasmid exhibited a dose-dependent increase in TOP-flash activity. Results for replicate samples are shown, and experiments were done three times. −, absent. (D) Sox17 represses the proliferation of SW480 cells. The formation of puromycin-resistant SW480 cell colonies was used to measure the effect of Sox17 on cell proliferation. SW480 cells were cotransfected with the pBABE-puromycin resistance plasmid, the pmax-GFP plasmid, and either an empty vector or a Sox17 expression vector and grown in puromycin-containing medium for 5 days. Insets show GFP-positive cells before (left) and after (right) puromycin selection. Only colonies that had ≥10 GFP-positive cells were counted. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means of results for three replicate samples. Puro, puromycin. (E) Sox4 promotes the proliferation of SW480 cells. SW480 cells that expressed Sox4 formed more colonies than vector-alone controls. Insets show GFP-positive cells before (left) and after (right) puromycin selection. (F and G) The effects of the loss and gain of function of Sox17 on Wnt and Sox17 target gene expression in Xenopus embryos. MO (20 ng each) previously used to deplete Xenopus embryos of Sox17 (6) or β-catenin (13) were injected into two-cell embryos, and stage 11 embryos were harvested and pooled in groups of three for each condition. Real-time RT-PCR analysis was used to analyze the relative levels of expression of the Wnt target genes Xnr3 and Siamois (data not shown), the Sox17 target gene Hnf1β, or the ubiquitously expressed gene Plakoglobin (Plako). All gene expression levels are shown as a ratio of the expression of the indicated gene to that of the ubiquitously expressed ODC gene (44). These results demonstrate that Sox17 is required to restrict the activity of Wnt/β-catenin/TCF in Xenopus embryos. (H) siRNA-mediated knockdown of Sox17 and Sox4 proteins in SW480 cells. SW480 cells were transfected with 50 nM scrambled control siRNA (C) or the Sox siRNA (S). The left panels show Western blot analyses of Sox17 and Sox4 proteins, and the right panels are confocal images of transfected SW480 cells showing the typical perinuclear localization of the fluorescently labeled control siRNA (red). Nuclei are stained with SYTOX green. (I and J) siRNA knockdown of endogenous Sox17 and Sox4 mRNA levels. Transfection with Sox17 siRNAs resulted in a 70% reduction of endogenous mRNA, whereas Sox4 siRNAs effected >90% reduction relative to mRNA levels in cells transfected with a control siRNA. (K) Quantitative assessment of apoptosis in SW480 cells as measured by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining 48 h after transfection with Sox4 and Sox17 siRNAs. −, control. (L) Quantitative assessment of proliferation of SW480 cells as measured by phosphohistone-H3 (PH3) staining 48 h after transfection with siRNAs. * indicates significance corresponding to a P value of 0.001 versus control samples as calculated using a t test analysis. −, control. (M and N) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the Wnt target genes c-myc (I) and cyclin D1 (J) in SW480 cells 48 h after transfection with Sox4 and Sox17 siRNAs. Quantitative PCR analyses of triplicate biological samples were performed. * indicates significance corresponding to a P value of 0.02 versus control samples as calculated using a t test analysis. −, control. Scale bars in panels A, D, E, and H, 20 μm.

To investigate the functions of endogenous Sox17 and Sox4, we performed siRNA knockdowns of each factor and quantitatively measured the effects on cell proliferation, apoptosis, and endogenous Wnt target genes (Fig. 2H to N). We transfected SW480 cells with an equimolar mixture of three siRNAs for either Sox17 or Sox4 and found that the transfection efficiency was >80%, as determined by the presence of a fluorescently labeled control siRNA (Fig. 2H, right panels). We achieved >60% reduction in Sox17 mRNA levels (Fig. 2I) and >80% reduction in protein levels (Fig. 2H). Sox4 mRNA levels were reduced by >90%, whereas Sox4 protein levels were reduced by ∼70%. These data suggest that Sox4 protein may be more stable than Sox17. Sox4 knockdown resulted in a significant reduction in SW480 cell proliferation and an accompanying reduction in the levels of Wnt target genes c-myc and cyclin D1 (Fig. 2K, M, and N), whereas apoptosis was not significantly affected (Fig. 2L). The efficacy and specificity of Sox4 siRNA knockdown were confirmed by the analysis of two Sox4 target genes, Puma and Tle-1 (22a), both of which had significantly reduced levels of expression in cells transfected with Sox4 siRNA (data not shown). Sox17 knockdown caused a modest increase in proliferation and cyclin D1 mRNA levels. The fact that Sox17 does not have more of an effect in colon carcinoma cells is likely due to the presence of other Sox factors, such as Sox9, that are functionally redundant in relation to Sox17. For example, Sox9 is also a Wnt antagonist (Fig. 1) that is expressed in the gut and represses gut cell proliferation (2, 27).

Sox17 antagonizes endogenous TCF/β-catenin activity in embryos.

Sox17 was previously shown to antagonize canonical Wnt signaling through an unidentified mechanism when overexpressed in Xenopus embryos (44, 55). To investigate whether endogenous Sox17 may perform a similar function in vivo, we depleted Xenopus embryos of either Sox17 or β-catenin by the injection of antisense MO and examined the expression of direct TCF/β-catenin target genes (Fig. 2F and G) (6, 13). As predicted, the depletion of Xenopus embryos of Sox17 resulted in the up regulation of the Wnt target gene Xnr3, whereas the overexpression of Sox17 repressed Xnr3 expression (Fig. 2G) (55). These data further indicate that one normal function of Sox17 is to restrict the activity of β-catenin/TCF. As a control, we demonstrated that the knockdown of β-catenin resulted in the loss of expression of both β-catenin/TCF and β-catenin/Sox17 target genes (Xnr3 and Hnf1β, respectively) (Fig. 2F and G) (13, 44). Taken together, these findings suggest that Sox proteins normally function to either positively or negatively modulate Wnt/β-catenin/TCF activity in a variety of cellular contexts.

Sox proteins interact with β-catenin and TCF/LEF proteins.

Previous studies demonstrated that Xenopus Sox17 binds to β-catenin in vitro (55), suggesting that Sox17-mediated repression in colon carcinoma cells may involve direct interaction with β-catenin. To test this possibility, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation assay using a polyclonal antibody that recognizes mouse and human Sox17 and found that β-catenin can be coimmunoprecipitated with Sox17 from SW480 nuclear extracts (Fig. 3A). This interaction was blocked with a Sox17 peptide used to generate the antibody but not with a control peptide generated from a nonconserved region of Xenopus Sox17β. This finding confirms that the interaction between Sox17 and β-catenin is conserved in Xenopus and humans and suggests that this interaction may be involved in the Sox17-mediated repression of Wnt signaling.

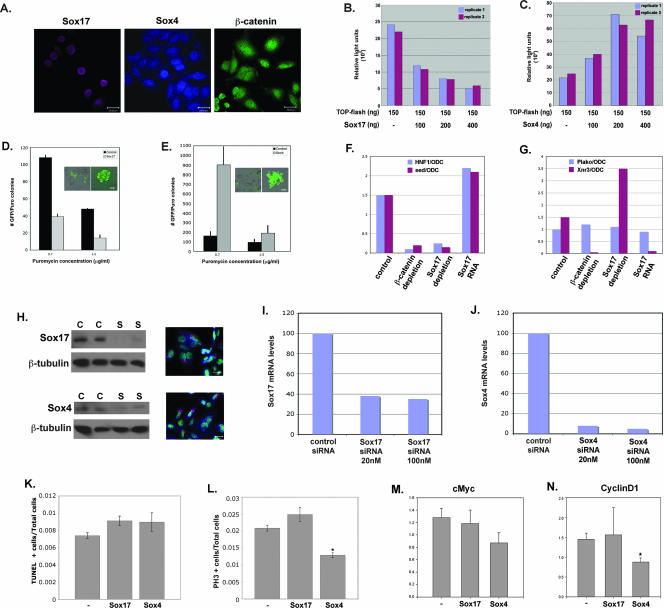

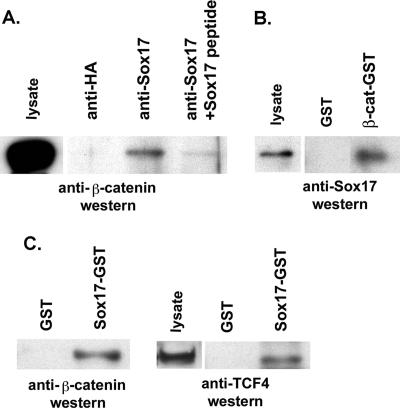

FIG. 3.

Endogenous Sox17, β-catenin, and TCF4 proteins interact in SW480 colon carcinoma cell lysates. (A) Sox17 antibodies were used to coimmunoprecipitate interacting proteins from nuclear extracts of SW480 cells. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with a control antibody (lane 1; anti-HA) or with a Sox17 antibody alone (lane 2) or in the presence of a Sox17 peptide or a control peptide (lanes 3 and 4). The Sox17 peptide used to generate the antibody inhibited the immunoprecipitation. (B) β-catenin (β-cat)-GST-linked beads or glutathione beads alone (GST) were incubated with cell lysates from SW480 cells, and precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-Sox17 antibody. The Sox17 antibody was raised in rabbits and recognizes both mouse and human Sox17. (C) Sox17-GST beads or GST beads alone (GST) were incubated with cell lysates from SW480 cells, and precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti β-catenin or anti-TCF4 antibodies.

One possible mechanism by which Sox17 may antagonize β-catenin/TCF activity is by competing with TCF factors for binding to β-catenin. To investigate this idea, we determined whether TCF4-β-catenin interactions and Sox17-β-catenin interactions were mutually exclusive in pull-down experiments using SW480 lysates with Sox17-GST beads. If Sox17 competes with TCF4 for binding to β-catenin, we would predict that Sox17-GST should pull down only β-catenin without TCF4. Surprisingly, we found that Sox17-GST beads pulled down both endogenous β-catenin and TCF4 (Fig. 3C). These findings are the first reported evidence that Sox17 may interact with both TCF and β-catenin proteins and further suggest that Sox17 does not antagonize Wnt signaling by competing with TCF factors for binding to β-catenin.

Sox17 but not Sox4 forms a stabilized protein complex containing both TCF and β-catenin.

To further investigate whether Sox and TCF proteins interact, we performed a series of in vitro binding assays with recombinant Sox17, Sox4, β-catenin, and TCF/LEF proteins (Fig. 4 and 5). Using Sox17-GST beads, we determined that Sox17 binds directly to TCF4, TCF3, and LEF1 (Fig. 4A), which indicates that TCF/LEF transcription factors physically interact with Sox proteins.

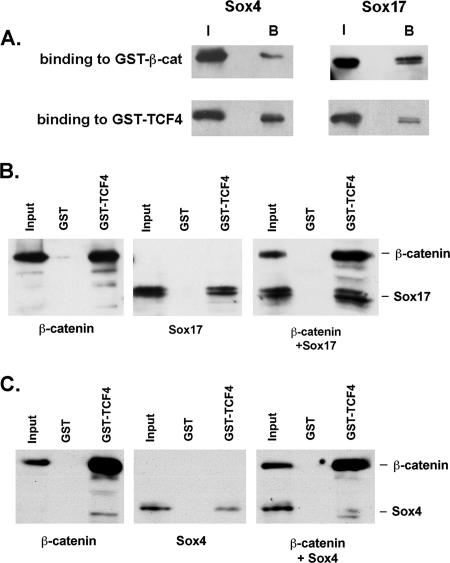

FIG. 5.

Sox4 and Sox17 have similar affinities for TCF4 and β-catenin, but Sox4 does not form a stable complex. (A) Sox4 has affinities for TCF4 and β-catenin (β-cat) similar to those of Sox17. The ratios of the input (I) and bound (B) protein fractions are similar for Sox17 and Sox4. (B) Sox17 formed a complex with β-catenin and TCF4. Also, more Sox17 protein was pulled down by TCF4-GST beads in the presence of β-catenin. (C) GST-TCF4 beads were able to pull down either β-catenin or Sox4 but did not efficiently pull down Sox4 in the presence of β-catenin. Moreover, Sox4 binding to TCF4 was somewhat inhibited in the presence of β-catenin, suggesting that Sox4 and β-catenin compete for binding.

Given that Sox17 interacts with either TCF or β-catenin protein, we investigated whether these three proteins can simultaneously interact to form a complex. As expected, β-catenin-GST beads pulled down either Sox17 or TCF4 protein (Fig. 4B). When Sox17 and TCF4 proteins were added together, both proteins bound to β-catenin-GST beads but not to control GST beads. Moreover, the interaction between Sox17 and β-catenin appeared to be stabilized in the presence of TCF4 (compare the ratios of input protein to bound protein with and without TCF4). These data suggest that rather than Sox17's and TCF's competing for β-catenin binding, all three proteins interact to form a complex. Consistent with this suggestion, adding increasing amounts of purified Sox17 protein into the binding assay mixture stabilized the interaction of β-catenin and TCF3 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C). In contrast, a truncated Sox17 protein lacking the C-terminal, β-catenin interaction domain did not stabilize the complex.

To further test the hypothesis that the interaction of all three proteins serves to stabilize a complex, we repeated the in vitro binding experiments with higher salt concentrations at which β-catenin would not efficiently bind to GST-Sox17 but at which TCF could (Fig. 4D and E). Under these conditions, we found that the ability of Sox17-GST to pull down β-catenin protein was restored in the presence of TCF4 or TCF3 (Fig. 4D and E). Moreover, we demonstrated that the β-catenin interaction domain of TCF3 was necessary for the ability of Sox17 to pull down β-catenin (Fig. 4E).

In summary, rather than Sox17's and TCF's competing for β-catenin binding, as had been previously proposed, we found that all three proteins interact in a complex. The interaction between TCF/LEF and β-catenin proteins is stabilized in the presence of Sox17, and this stabilization depends on the ability of Sox17 to interact with β-catenin. Similarly, Sox17-β-catenin interactions are stabilized in the presence of TCF/LEF and depend on the ability of Sox17 to interact with TCF/LEF.

The fact that Sox4 has an impact on β-catenin/TCF activity opposite that of Sox17 prompted us to investigate whether this difference is manifested at the level of β-catenin/TCF protein-protein interaction. We found that Sox4, like Sox17, could bind directly to TCF4 or β-catenin (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, in three separate experiments, Sox4 was unable to enhance the binding between TCF4 and β-catenin, as Sox17 could (Fig. 5B and C). In fact, our data suggested that Sox4, TCF/LEF, and β-catenin may interfere with binding to one another (Fig. 5C and data not shown). One implication of these data is that the differences in Sox17 and Sox4 binding to β-catenin and TCF may account for the opposite effects of these proteins on Wnt signaling activity.

Sox17 has distinct TCF and β-catenin interaction domains.

To further investigate the nature of the Sox17-β-catenin-TCF protein complex, we performed reciprocal structure-function binding assays to identify the domains that mediate this interaction. We generated a series of deletions and several point mutations in Sox17 and assayed the ability of mutant proteins to bind to TCF4-GST or β-catenin-GST beads (Fig. 6A). An N-terminal deletion of Sox17 (leaving amino acids 129 to 419 intact) that removed 80% of the HMG domain greatly reduced the ability of the protein to bind to TCF4, whereas the deletion of the C-terminal β-catenin interaction domain (55) had little effect (Fig. 6A). A point mutation (G to R at amino acid 103) was generated in the HMG domain of Sox17, which based on the crystal structure of the HMG domain of LEF1 (23) was predicted to disrupt the α-helical structure of the HMG domain. This mutation abolished the ability of Sox17 to interact with TCF4 but did not reduce β-catenin binding (Fig. 6A). We generated a second point mutation in the HMG domain (M to A at amino acid 76), which was not predicted to affect HMG domain structure (50) but rather impair DNA binding. As predicted, the Sox17 M-to-A mutant form retained the ability to interact with TCF4 and β-catenin proteins but was incapable of activating the transcription of a Sox17 reporter gene (pH4X8-Luci) (Fig. 6A and D). These data suggest that the HMG domain of Sox17 mediates the interaction with TCF4 and is distinct from the β-catenin interaction domain.

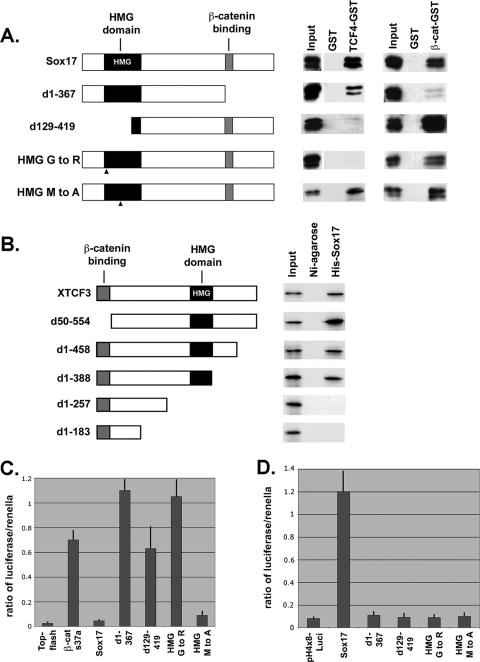

FIG. 6.

Structure-function analyses of Sox17-TCF-β-catenin interactions. (A) Sox17 interacts with TCF4 protein via its HMG domain. The left panel shows a schematic diagram of Sox17 deletions and point mutations. HMG mutant 1 carries a stringent mutation (G to R at amino acid 103), and HMG mutant 2 carries a more conservative mutation (M to A at amino acid 76). d1-367, now contains amino acids 1 to 367; d129-419, now contains amino acids 129 to 419. The right panel shows the interaction of in vitro-translated Sox17 mutant proteins (V5 tagged) with GST alone, TCF4-GST, or β-catenin (β-cat)-GST. (B) Identification of protein domains of TCF3 that mediate its interaction with Sox17. The left panel shows a schematic diagram of deletions of Xenopus TCF3. The right panel shows the interaction of the in vitro-translated S35-labeled TCF3 mutant proteins with His-tagged Xenopus Sox17β or Ni-agarose alone. (C) Sox17 requires interactions with both β-catenin and TCF/LEF to antagonize Wnt activity. COS cells were transfected with β-catenin(S37A) and TOP-flash alone or together with the Sox17 mutant forms, and TOP-flash activity was measured after 48 h. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means of results for replicate samples from at least three separate experiments. (D) Sox17 does not require transcriptional activity to antagonize Wnt activity. 293T cells were cotransfected with Sox17 and derived mutant forms and a Sox17 reporter plasmid (pH4X8-Luci). The transcriptional activity of Sox17 requires a functional DNA binding domain (HMG domain) and a functional transactivation domain (at the C terminus). While the Sox17 HMG mutant form carrying an M-to-A mutation is transcriptionally inactive, it still is able to interact with both TCF4 and β-catenin and antagonize Wnt activity. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means of results for replicate samples from two separate experiments.

In the reciprocal experiment, we generated a series of deletions in XTCF3 and assayed the ability of the mutant forms to bind to His-tagged Sox17 in vitro (Fig. 6B). Since all TCF family members tested interact with Sox17, we focused our structure-function analysis on one representative family member, TCF3. The deletion of the N-terminal β-catenin binding motif of TCF3 had no effect on the ability of TCF3 to interact with Sox17. However, the deletion of the HMG domain abolished TCF3 interaction with Sox17 (Fig. 6B). These data indicate that the interaction between Sox17 and TCF factors is mediated via their respective HMG domains. This idea is consistent with the recent finding that the HMG domains of Sox8 and Sox10 interact with DNA binding domains of several other transcription factors (3, 52).

Sox17 requires both its TCF and β-catenin interaction domains, but not transcriptional activity, for Wnt-antagonizing activity.

We used the mutant forms of Sox17 to investigate whether the interaction between Sox17, TCF/LEF, and β-catenin was necessary for Wnt-antagonizing activity. We found that Sox17 mutants that did not interact with either TCF/LEF or β-catenin failed to antagonize Wnt signaling in TOP-flash assays (Fig. 6C). One possibility was that Sox17 regulates Wnt signaling indirectly by activating the transcription of a gene encoding a Wnt antagonist. However, the Sox17 mutant protein with the M-to-A mutation (at amino acid 76), which was predicted to have impaired DNA binding ability and cannot stimulate the transcription of a Sox17 reporter gene (pH4X8-Luci), was still capable of repressing β-catenin-stimulated TOP-flash activity (Fig. 6C). Importantly, this Sox17 M-to-A mutant protein retained the ability to bind to both TCF/LEF and β-catenin (Fig. 6A). This finding suggests that Sox17 does not antagonize Wnt signaling via transcription but rather does so by direct interaction with TCF/LEF and β-catenin.

Sox factors regulate the degradation of β-catenin and TCF/LEF proteins.

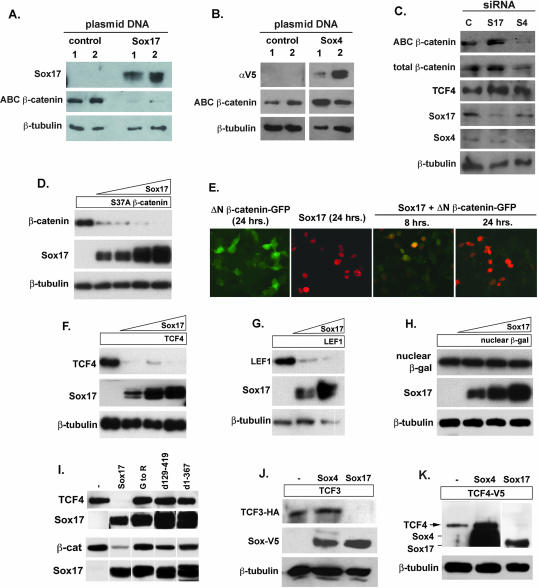

While performing transfection experiments with Sox17 and β-catenin plasmids, we observed reduced β-catenin protein levels in cells cotransfected with Sox17. We therefore analyzed the effect of Sox17 overexpression on levels of endogenous β-catenin protein in SW480 cells. We found that the unphosphorylated signaling pool of β-catenin protein was significantly reduced in the presence of elevated levels of Sox17 protein (Fig. 7A) (the activated-β-catenin antibody recognizes unphosphorylated β-catenin). In contrast, β-catenin protein levels were elevated when Sox4 was overexpressed (Fig. 7B). In RNA interference experiments, we found the opposite; a reduction of Sox4 protein coincided with a significant reduction of endogenous unphosphorylated β-catenin protein, and Sox17 siRNAs caused a modest increase in β-catenin protein (Fig. 7C). Similarly, endogenous TCF4 protein levels were slightly elevated by Sox17 siRNAs; however Sox4 siRNAs had no impact on TCF4 levels. These data suggest that Sox factors modulate β-catenin/TCF activity through regulating protein levels.

FIG. 7.

Sox proteins affect β-catenin and TCF/LEF protein levels. (A and B) Effects of Sox17 and Sox4 overexpression on endogenous β-catenin protein levels in SW480 cells. The overexpression of Sox17 in SW480 cells causes significant reduction in the levels of endogenous unphosphorylated β-catenin protein, which was detected using an antibody specific for unphosphorylated β-catenin (ABC β-catenin). The overexpression of Sox4 caused an increase in the levels of endogenous unphosphorylated β-catenin protein. αV5, anti-V5 antibody. (C) Impact of siRNA knockdown of Sox17 (S17) and Sox4 (S4) on β-catenin and TCF4 levels in SW480 cells. Reduced levels of endogenous Sox4 protein coincide with a significant decrease in unphosphorylated β-catenin protein. Reduced levels of endogenous Sox17 protein coincide with a slight increase in β-catenin and TCF4 protein levels. C, control. (D) Sox17 promotes the degradation of stabilized β-catenin protein in a dose-dependent manner. COS cells (or 293T cells [data not shown]) were transfected with a plasmid encoding stabilized β-catenin (carrying the S37A mutation and tagged with V5 epitope; 100 ng) alone or with increasing amounts of a Sox17 expression plasmid (50, 100, 200, and 400 ng). After 24 to 48 h, cell lysates were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-V5 (β-catenin), anti-Sox17, and anti-β-tubulin antibodies. (E) Time course of Sox17-mediated reduction in stabilized β-catenin protein. Cells were transfected with a Sox17 plasmid (100 ng) and a plasmid encoding stabilized, GFP-tagged β-catenin (ΔN β-catenin-GFP; 100 ng) alone or together. The expression levels of Sox17 and β-catenin were analyzed 8 and 24 h posttransfection by the analysis of GFP for β-catenin or by immunohistochemistry analysis with a Sox17 antibody. (F and G) Sox17 promotes the degradation of TCF4 (F) and LEF1 (G) proteins in a dose-dependent manner. (H) A Sox17 plasmid (50, 100, and 200 ng) had no effect on the levels of expression of nuclear β-galactosidase protein (β-gal), demonstrating that Sox17 did not generally affect the transcription or translation of plasmids in cotransfected cells. β-tubulin protein was used to indicate that each lane contained roughly equivalent amounts of total protein. (I) The interaction of Sox17 with either TCF4 or β-catenin (β-cat) is required for the degradation of these proteins. COS cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding Sox17 mutant forms and TCF4 or β-catenin, and degradation was analyzed by Western blotting of cell extracts after 48 h. The relative levels of expression of the V5 epitope-tagged Sox17 mutant forms are shown in the bottom panel. Mutant forms of Sox17 that retained the ability to interact with TCF but failed to interact with β-catenin were unable to promote TCF4 degradation and vice versa, suggesting that interaction with both is required for degradation. −, control. (J and K) Effects of Sox4 versus Sox17 on TCF3 and TCF4 protein levels. Sox4, Sox17, and TCF4 proteins were detected by Western blotting with an anti-V5 antibody and closely comigrate, as indicated in panel K. TCF3 protein was detected using a HA epitope tag, and the Sox proteins were detected using a V5 epitope tag. β-Tubulin protein was used to indicate that each lane contained roughly equivalent amounts of total protein. −, control. For all panels, experiments were repeated at least three times and results from a representative experiment are shown.

Endogenous protein levels can be affected by transcription, translation, or protein stability. Our data suggest that Sox proteins may affect β-catenin/TCF protein levels posttranslationally via direct protein-protein interaction. To avoid the effects of Sox proteins on β-catenin and TCF transcription and translation, we studied how Sox factors affect β-catenin and TCF proteins that are expressed from plasmids in cotransfected cells, in which the transcription and translation of these factors should be relatively constant. We first performed a time course experiment to analyze the effects of Sox17 on the signaling pool of β-catenin protein by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 7E). We found that 8 h after cotransfection, both Sox17 and nonphosphorylatable β-catenin protein (stabilized β-catenin-GFP fusion protein with an N-terminal deletion in β-catenin) were detected in the same cells. In contrast, 24 h posttransfection, Sox17 protein levels were the same but β-catenin-GFP protein was not detectable in most cells. We quantitatively investigated the relationship between Sox17 and β-catenin protein levels by cotransfecting cells with increasing amounts of a Sox17 plasmid and a constant amount of a β-catenin(S37A)-expressing plasmid (the S37A mutation renders β-catenin nonphosphorylatable and thus stable). Increasing amounts of Sox17 protein directly correlated with a decrease in β-catenin(S37A) protein levels in COS cells (Fig. 7D) and 293T cells (data not shown). Sox17 did not generally inhibit the transcription or translation of plasmids in cotransfected cells since Sox17 had no effect on protein levels driven from a plasmid encoding nuclear β-galactosidase (Fig. 7H). In addition, the mRNA levels corresponding to the β-catenin plasmid in transfected cells were unaffected by Sox17 (data not shown).

While it has been previously reported that Sox9 affects β-catenin protein levels (2), we have demonstrated that Sox17 also interacts with TCF/LEF proteins. Therefore, it is possible that Sox17 may regulate the levels of TCF/LEF proteins. To investigate this possibility, COS cells were cotransfected with TCF4 or LEF1 expression plasmids and increasing levels of a Sox17 plasmid, and extracts were harvested 48 h later (Fig. 7F and G). Interestingly, an increase in Sox17 correlated with a dramatic reduction in TCF4 and LEF1 protein levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7F and G). To determine if Sox17 needed to interact directly with TCF4 and β-catenin protein to modulate the stability of these proteins, we used the mutant forms of Sox17 depicted in Fig. 6A. Sox17 mutant proteins that did not interact with TCF4 also failed to promote its degradation, and mutant proteins that did not interact with β-catenin did not promote its degradation (Fig. 7I). Interestingly, a Sox17 mutant protein (containing only amino acids 1 to 367) that failed to interact with β-catenin but still interacted with TCF4 was unable to promote TCF4 degradation. The converse was true in that interaction with TCF4 was required for β-catenin degradation. Together, these findings suggest that Sox17 must directly interact with both β-catenin and TCFs to trigger the degradation of the complex and to antagonize Wnt signaling.

We next investigated whether Sox4 overexpression affected TCF4 or TCF3 protein levels. The Sox and TCF4 proteins were both V5 tagged, which allowed for the direct comparison of protein levels by Western blotting with an anti-V5 antibody. As expected, Sox17 overexpression coincided with a reduction in TCF4 and TCF3. In three separate experiments, Sox4 overexpression either caused no change or effected a slight increase in TCF4 protein levels and had little effect on TCF3 (Fig. 7J and K). Also, Sox4 overexpression had no effect on levels of coexpressed β-catenin(S37A) protein (data not shown). These findings are the first to indicate that Sox factors regulate Wnt signaling by modulating the stability of TCF/LEF family members.

Sox17 stimulates β-catenin and TCF4 protein degradation by the proteasome in a GSK3-independent manner.

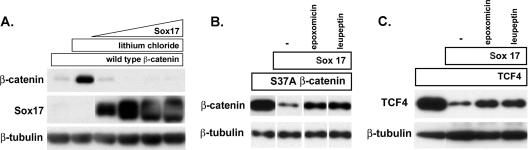

Our data suggest that the Sox17-mediated degradation of β-catenin is GSK3β independent because mutant forms of β-catenin that cannot be phosphorylated by GSK3β and thus are constitutively stable were still targeted for degradation by Sox17 (Fig. 7D and E). To confirm this finding, we inhibited GSK3β activity by including lithium chloride in the culture medium and monitored levels of wild-type β-catenin (myc tagged) alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of a Sox17 plasmid. As expected, wild-type β-catenin protein did not accumulate in COS cells (Fig. 8A, lane 1); however, including LiCl (40 mM) in the culture medium resulted in the accumulation of wild-type β-catenin protein (Fig. 8A, lane 2). The coexpression of Sox17 in LiCl-treated cultures caused a dose-dependent loss of wild-type β-catenin protein. This finding confirms that Sox17 promotes GSK3β-independent degradation of wild-type β-catenin protein.

FIG. 8.

Sox17-mediated degradation of β-catenin and TCF4 is independent of GSK3β activity and mediated by the proteasome. (A) LiCl does not affect Sox17-mediated degradation of β-catenin. COS cells were transfected with an expression plasmid encoding wild-type β-catenin (100 ng; myc tagged) in the absence (lane 1) or presence(lanes 2 to 6) of 40 mM LiCl. Cells were cotransfected with increasing amounts of Sox17 plasmid (50, 100, 200, and 400 ng) and the wild-type β-catenin gene in the presence of lithium chloride (lanes 3 to 6). LiCl effectively stabilized wild-type β-catenin protein in the absence of Sox17 but could not inhibit Sox17-mediated degradation of wild-type β-catenin protein. (B and C) The proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin inhibits Sox17-induced degradation of stabilized β-catenin (B) and TCF4 (C). Cells were transfected with the β-catenin(S37A) mutant form (100 ng) or TCF4 (100 ng) alone or together with Sox17 (100 ng). Culturing cotransfected cells with epoxomicin (0.1 μM) or leupeptin (25 μM) inhibited Sox17-mediated degradation of β-catenin and TCF4 proteins. The lysosomal acidification inhibitor cholorquine (25 μM) had no effect (data not shown). −, control.

The targeted degradation of many cellular proteins, including β-catenin, is mediated by the proteasome (1). We used the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin to determine if the Sox17-mediated reduction in β-catenin and TCF4 protein levels was due to degradation by the proteasome. We cotransfected cells with Sox17 and a gene for stabilized β-catenin(S37A) or TCF4 and cultured cells in the presence or absence of epoxomicin (Fig. 8B and C). Sox17-mediated degradation of both TCF4 and β-catenin was substantially inhibited by epoxomicin, which selectively inhibits the chymotrypsin-like activity of the proteasome (25). Interestingly, the degradation of β-catenin and TCF4 was also repressed by the protease inhibitor leupeptin, which inhibits the lysosomal protease cathepsin B (42) as well as other serine and cysteine proteases. The specific lysosomal acidification inhibitor cholorquine had no effect on the degradation of either β-catenin or TCF4 (data not shown), suggesting that these proteins are not degraded by the lysosome. These data suggest that the proteasome and possibly a leupeptin-sensitive protease are involved in Sox17-mediated degradation of β-catenin and TCF4.

DISCUSSION

The expression of several Sox proteins has been tightly correlated with colon cancer progression. Our data and previously published findings indicate that Sox4 expression levels are elevated in intestinal tumors whereas the expression of Sox17 is reduced in adenomas relative to that in normal gut epithelia (Fig. 1) (8, 32, 38). We have identified some Sox proteins as repressors and others as enhancers of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity and the proliferation of colon carcinoma cells, suggesting that Sox proteins may act as tumor suppressors or tumor promoters. While Sox factors are best known for their transcriptional function, we have identified a novel posttranslational mechanism by which Sox proteins regulate Wnt signaling and cell proliferation.

Nontranscriptional functions of Sox factors.

We have demonstrated that Sox17 and Sox4 can directly interact with β-catenin and TCF/LEF proteins. In the case of Sox17, it forms a complex with both β-catenin and TCF. This finding is significant because one of the prevailing models is that Sox17 may antagonize Wnt activity by competing with TCFs for binding to β-catenin, in which case Sox17 and TCF binding would be mutually exclusive. Our data show that Sox17 antagonizes the Wnt pathway by promoting the degradation of TCF/LEF and β-catenin proteins via a GSK3β-independent mechanism. Structure-function analyses indicate that Sox17 must be able to interact directly with both TCF and β-catenin in order to promote their turnover. In contrast, while Sox4 can bind to TCF and β-catenin individually, the three proteins do not appear to from a stable complex. In addition, Sox4 overexpression does not promote β-catenin/TCF degradation like the overexpression of Sox17 does. Rather, reduced levels of Sox4 were associated with a reduction of β-catenin protein, and the overexpression of Sox4 either had no impact on TCF4 levels or in some instances caused an increase in TCF4 protein levels. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that Sox proteins modulate canonical Wnt signaling by influencing levels of TCF/LEF factors.

In addition to a reduction in β-catenin protein levels, the knockdown of Sox4 coincided with a decrease in the activation of β-catenin and TCF target genes, such as cyclin D1, and reduced the proliferation of colon carcinoma cells, whereas reduced Sox17 levels had the opposite effect in these cells and in Xenopus embryos, resulting in the hyperactivation of Wnt target genes. Together, these data suggest that Sox proteins normally function to modulate β-catenin/TCF activity in vivo. One possible mechanism by which Sox4 may stabilize β-catenin was suggested by the finding of Lee et al. (19), who demonstrated that TCF3 can stabilize β-catenin protein by preventing its association with Axin and APC.

Transcriptional functions of Sox, β-catenin, and TCF proteins.

Although we have demonstrated that the ability of Sox17 to antagonize β-catenin and TCF is separable from its role as a transcription factor, it is possible that the transcriptional function of Sox proteins may also have an impact on Wnt signaling in some contexts. For example, Sox and TCF proteins may compete for common DNA binding sites or shared cofactors. In Xenopus, there is evidence that Sox3 and TCF bind to adjacent DNA sites to coordinately regulate the expression of the Wnt and β-catenin target gene Xnr5 (54). In addition, it has recently been shown that the HMG domain of Sox factors can interact with other transcription factors, including homeodomain proteins, zinc finger proteins, and basic helix-loop-helix and leucine zipper proteins (3, 52), each of which may affect the ability of Sox factors to bind DNA or interact with cofactors such as β-catenin and TCF proteins. Thus, in addition to Sox proteins' regulating β-catenin and TCF protein stability, Sox-TCF complexes may regulate target gene transcription.

In the case of Sox17, there is evidence that it has two distinct functions, to repress or limit β-catenin and TCF activity and to use β-catenin as a cofactor to activate Sox17 target gene expression in Xenopus embryos. The depletion of Xenopus embryos of endogenous Sox17 protein results in the hyperactivation of Wnt target genes, and the depletion of β-catenin results in reduced Sox17 target gene expression. Although transcriptional targets of Sox17 in the intestinal epithelium are unknown, we postulate that a similar mechanism may act there. Together, the present and previously published findings show that Sox17 can either utilize β-catenin as a transcriptional cofactor or promote the degradation of β-catenin and TCFs. Thus, Sox17 may radically shift the transcriptional output of the Wnt signaling pathway from TCF to Sox target genes. Ultimately, the function of Sox17 as a Wnt antagonist or a transcriptional activator may depend on the relative levels of Sox17, β-catenin, and TCF/LEF. In a case in which the signaling pool of β-catenin is in excess, we predict that high Sox17 levels could both repress Wnt signaling by promoting the degradation of β-catenin-TCF complexes and activate the expression of Sox17 target genes.

Sox proteins and cancer.

Oncogenic, activating mutations in β-catenin stabilize the protein by preventing its phosphorylation by GSK3β and subsequent degradation and are associated with the formation of colorectal carcinoma (26, 28, 46). Our data show that Sox17 promotes the degradation of oncogenic forms of β-catenin, suggesting its possible role as a tumor suppressor. Consistent with such a function, Sox17 expression levels are down regulated in APCmin/+ tumors and in colon cancer as adenomas progress to carcinomas (32). In addition, Sox17 mRNA was almost undetectable in 66 human primary tumors derived from various tissues (16). Finally, our functional analysis of Sox17 clearly indicates that this factor represses colon carcinoma cell proliferation and Wnt signaling, possibly via targeting β-catenin and TCF for degradation. These findings suggest that down regulating Wnt antagonists like Sox17 may be an obligatory step in tumor formation and progression.

In contrast to those of Sox17, elevated Sox4 levels are correlated with cancer in many contexts; Sox4 was identified as one of the most highly tumor-associated genes in an insertional mutagenesis screen for oncogenes (47). Elevated Sox4 levels are associated with small-cell lung carcinomas and medulloblastomas (9, 18, 45) and APCmin/+ adenomas (Fig. 1) (8, 32, 38). Our data provide a novel mechanism by which Sox4 may act as an oncogene, namely, by stimulating Wnt signaling, possibly by regulating β-catenin or TCF protein stability and/or activity. Together, our findings suggest a novel mechanism by which some Sox proteins may act as protooncogenes while others may act as tumor suppressors by regulating β-catenin and TCF protein activity.

Mammals have over 20 Sox proteins that are found in many cell types (41). The fact that most Sox proteins can have an impact on canonical Wnt responses in TOP-flash assays suggests that Sox-mediated regulation of β-catenin and TCF proteins is a broadly utilized mechanism that may regulate Wnt signaling in a variety of physiological and pathological contexts, ranging from embryonic development to cancer. Moreover, this novel GSK3β-independent means to degrade TCF/LEF and β-catenin proteins represents a new molecular target for drug therapies that target the canonical Wnt pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gail Deutsch, Janet Heasman, and Xinhua Lin for comments on the manuscript and members of the Wells and Zorn labs for advice. We thank Richard Harland, Mike Klymkowsky, and Hugh Woodland for reagents. We thank Michael Weiss for advice on HMG box mutations. We also thank Michael Kleimeyer and Bruce Aronow for help with the clustering analysis depicted in Fig. 1.

This research was supported by a career development award and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (J.M.W. and S.-C.J.L.), an NIH training grant in developmental and perinatal endocrinology, no. T32 HD07463 (J.R.S.), and the NIH grants HD42572 (A.M.Z.) and GM072915 (J.M.W.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 September 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberle, H., A. Bauer, J. Stappert, A. Kispert, and R. Kemler. 1997. β-Catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 16:3797-3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akiyama, H., J. P. Lyons, Y. Mori-Akiyama, X. Yang, R. Zhang, Z. Zhang, J. M. Deng, M. M. Taketo, T. Nakamura, R. R. Behringer, P. D. McCrea, and B. de Crombrugghe. 2004. Interactions between Sox9 and beta-catenin control chondrocyte differentiation. Genes Dev. 18:1072-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambrosetti, D. C., C. Basilico, and L. Dailey. 1997. Synergistic activation of the fibroblast growth factor 4 enhancer by Sox2 and Oct-3 depends on protein-protein interactions facilitated by a specific spatial arrangement of factor binding sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6321-6329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavallo, R. A., R. T. Cox, M. M. Moline, J. Roose, G. A. Polevoy, H. Clevers, M. Peifer, and A. Bejsovec. 1998. Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signalling activity. Nature 395:604-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, C. M., C. L. Kao, Y. L. Chang, M. J. Yang, Y. C. Chen, B. L. Sung, T. H. Tsai, K. C. Chao, S. H. Chiou, and H. H. Ku. 2007. Placenta-derived multipotent stem cells induced to differentiate into insulin-positive cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 357:414-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements, D., I. Cameleyre, and H. R. Woodland. 2003. Redundant early and overlapping larval roles of Xsox17 subgroup genes in Xenopus endoderm development. Mech. Dev. 120:337-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clevers, H. 2006. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127:469-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du, Y., S. E. Spence, N. A. Jenkins, and N. G. Copeland. 2005. Cooperating cancer-gene identification through oncogenic-retrovirus-induced insertional mutagenesis. Blood 106:2498-2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman, R. S., C. S. Bangur, E. J. Zasloff, L. Fan, T. Wang, Y. Watanabe, and M. Kalos. 2004. Molecular and immunological evaluation of the transcription factor SOX-4 as a lung tumor vaccine antigen. J. Immunol. 172:3319-3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glinka, A., W. Wu, H. Delius, A. P. Monaghan, C. Blumenstock, and C. Niehrs. 1998. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature 391:357-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grapin-Botton, A., A. R. Majithia, and D. A. Melton. 2001. Key events of pancreas formation are triggered in gut endoderm by ectopic expression of pancreatic regulatory genes. Genes Dev. 15:444-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groden, J., A. Thliveris, W. Samowitz, M. Carlson, L. Gelbert, H. Albertsen, G. Joslyn, J. Stevens, L. Spirio, and M. Robertson. 1991. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell 66:589-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heasman, J., M. Kofron, and C. Wylie. 2000. Beta-catenin signaling activity dissected in the early Xenopus embryo: a novel antisense approach. Dev. Biol. 222:124-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huelsken, J., and W. Birchmeier. 2001. New aspects of Wnt signaling pathways in higher vertebrates. Curr. Opin. Gen. Dev. 11:547-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanai, Y., M. Kanai-Azuma, T. Noce, T. C. Saido, T. Shiroishi, Y. Hayashi, and K. Yazaki. 1996. Identification of two Sox17 messenger RNA isoforms, with and without the high mobility group box region, and their differential expression in mouse spermatogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 133:667-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katoh, M. 2002. Molecular cloning and characterization of human SOX17. Int. J. Mol. Med. 9:153-157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korinek, V., N. Barker, P. J. Morin, D. van Wichen, R. de Weger, K. W. Kinzler, B. Vogelstein, and H. Clevers. 1997. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC−/− colon carcinoma. Science 275:1784-1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, C. J., V. J. Appleby, A. T. Orme, W. I. Chan, and P. J. Scotting. 2002. Differential expression of SOX4 and SOX11 in medulloblastoma. J. Neuro-Oncol. 57:201-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, E., A. Salic, and M. W. Kirschner. 2001. Physiological regulation of β-catenin stability by Tcf3 and CK1epsilon. J. Cell Biol. 154:983-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levanon, D., R. E. Goldstein, Y. Bernstein, H. Tang, D. Goldenberg, S. Stifani, Z. Paroush, and Y. Groner. 1998. Transcriptional repression by AML1 and LEF-1 is mediated by the TLE/Groucho corepressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11590-11595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyns, L., T. Bouwmeester, S. H. Kim, S. Piccolo, and E. M. De Robertis. 1997. Frzb-1 is a secreted antagonist of Wnt signaling expressed in the Spemann organizer. Cell 88:747-756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lickert, H., C. Domon, G. Huls, C. Wehrle, I. Duluc, H. Clevers, B. I. Meyer, J. N. Freund, and R. Kemler. 2000. Wnt/(beta)-catenin signaling regulates the expression of the homeobox gene Cdx1 in embryonic intestine. Development 127:3805-3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Liu, P. S. Ramachandran, M. Ali Seyed, C. D. Scharer, N. Laycock, W. B. Dalton, H. Williams, S. Karanam, M. W. Datta, D. L. Jaye, and C. S. Moreno. 2006. Sex-determining region Y box 4 is a transforming oncogene in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 66:4011-4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Love, J. J., X. Li, D. A. Case, K. Giese, R. Grosschedl, and P. E. Wright. 1995. Structural basis for DNA bending by the architectural transcription factor LEF-1. Nature 376:791-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKendry, R., S. C. Hsu, R. M. Harland, and R. Grosschedl. 1997. LEF-1/TCF proteins mediate wnt-inducible transcription from the Xenopus nodal-related 3 promoter. Dev. Biol. 192:420-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng, L., R. Mohan, B. H. Kwok, M. Elofsson, N. Sin, and C. M. Crews. 1999. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10403-10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyaki, M., T. Iijima, J. Kimura, M. Yasuno, T. Mori, Y. Hayashi, M. Koike, N. Shitara, T. Iwama, and T. Kuroki. 1999. Frequent mutation of beta-catenin and APC genes in primary colorectal tumors from patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 59:4506-4509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mori-Akiyama, Y., M. van den Born, J. H. van Es, S. R. Hamilton, H. P. Adams, J. Zhang, H. Clevers, and B. de Crombrugghe. 2007. SOX9 is required for the differentiation of Paneth cells in the intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology 133:539-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morin, P. J., A. B. Sparks, V. Korinek, N. Barker, H. Clevers, B. Vogelstein, and K. W. Kinzler. 1997. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science 275:1787-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieuwkoop, P. D., and J. Faber (ed.). 1994. Normal table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin): a systematical and chronological survey of the development from the fertilized egg till the end of metamorphosis. Garland Science, London, United Kingdom.

- 30.Nishisho, I., Y. Nakamura, Y. Miyoshi, Y. Miki, H. Ando, A. Horii, K. Koyama, J. Utsunomiya, S. Baba, and P. Hedge. 1991. Mutations of chromosome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer patients. Science 253:665-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oving, I. M., and H. C. Clevers. 2002. Molecular causes of colon cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 32:448-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paoni, N. F., M. W. Feldman, L. S. Gutierrez, V. A. Ploplis, and F. J. Castellino. 2003. Transcriptional profiling of the transition from normal intestinal epithelia to adenomas and carcinomas in the APCMin/+ mouse. Physiol. Genomics 15:228-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park, K. S., J. M. Wells, A. M. Zorn, S. E. Wert, and J. A. Whitsett. 2006. Sox17 influences the differentiation of respiratory epithelial cells. Dev. Biol. 294:192-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pera, E. M., and E. M. De Robertis. 2000. A direct screen for secreted proteins in Xenopus embryos identifies distinct activities for the Wnt antagonists Crescent and Frzb-1. Mech. Dev. 96:183-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piccolo, S., E. Agius, L. Leyns, S. Bhattacharyya, H. Grunz, T. Bouwmeester, and E. M. De Robertis. 1999. The head inducer Cerberus is a multifunctional antagonist of Nodal, BMP and Wnt signals. Nature 397:707-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poy, F., M. Lepourcelet, R. A. Shivdasani, and M. J. Eck. 2001. Structure of a human Tcf4-beta-catenin complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:1053-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pramoonjago, P., A. S. Baras, and C. A. Moskaluk. 2006. Knockdown of Sox4 expression by RNAi induces apoptosis in ACC3 cells. Oncogene 25:5626-5639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reichling, T., K. H. Goss, D. J. Carson, R. W. Holdcraft, C. Ley-Ebert, D. Witte, B. J. Aronow, and J. Groden. 2005. Transcriptional profiles of intestinal tumors in Apc(Min) mice are unique from those of embryonic intestine and identify novel gene targets dysregulated in human colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 65:166-176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roose, J., M. Molenaar, J. Peterson, J. Hurenkamp, H. Brantjes, P. Moerer, M. van de Wetering, O. Destree, and H. Clevers. 1998. The Xenopus Wnt effector XTcf-3 interacts with Groucho-related transcriptional repressors. Nature 395:608-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubinfeld, B., B. Souza, I. Albert, O. Muller, S. H. Chamberlain, F. R. Masiarz, S. Munemitsu, and P. Polakis. 1993. Association of the APC gene product with beta-catenin. Science 262:1731-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schepers, G. E., R. D. Teasdale, and P. Koopman. 2002. Twenty pairs of sox: extent, homology, and nomenclature of the mouse and human sox transcription factor gene families. Dev. Cell 3:167-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]