Abstract

EWS/FLI-1 is a chimeric oncogene generated by chromosomal translocation in Ewing tumors, a family of poorly differentiated pediatric tumors arising predominantly in bone but also in soft tissue. The fusion gene combines sequences encoding a strong transactivating domain from the EWS protein with the DNA binding domain of FLI-1, an ETS transcription factor. A related fusion, TLS/ERG, has been found in myeloid leukemia. To determine EWS/FLI-1 function in vivo, we engineered mice with Cre-inducible expression of EWS/FLI-1 from the ubiquitous Rosa26 locus. When crossed with Mx1-cre mice, Cre-mediated activation of EWS/FLI-1 resulted in the rapid development of myeloid/erythroid leukemia characterized by expansion of primitive mononuclear cells causing hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, severe anemia, and death. The disease could be transplanted serially into naïve recipients. Gene expression profiles of primary and transplanted animals were highly similar, suggesting that activation of EWS/FLI-1 was the primary event leading to disease in this model. The Cre-inducible EWS/FLI-1 mouse provides a novel model system to study the contribution of this oncogene to malignant disease in vivo.

Specific chromosomal translocations are a common genetic mechanism in certain types of sarcomas and leukemias that create novel oncogenes presumed to play an important role in the initiation and/or progression of tumors that harbor them. Ewing tumors are defined at the molecular level by the presence of chromosomal translocations that produce chimeric oncogenes encoding the N-terminal transactivation domain of EWS fused to the C-terminal DNA binding domain from one of several ETS family genes (4). EWS belongs to a small family of RNA binding molecules termed TET proteins that includes TLS/FUS, EWS, and TAFII68 and appears to function in RNA transcription and/or mRNA processing (10, 11, 34, 77). The ETS transcription factor family is a diverse group of proteins that cooperate with other factors to regulate a wide range of cellular processes, such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and senescence (52). EWS/FLI-1 is the most common TET/ETS fusion found in Ewing tumors, occurring in 85% of reported cases, while other fusions, such as EWS/ERG, EWS/FEV, EWS/ETV1, EWS/E1AF, and TLS/ERG, occur at much lower frequencies (31).

Although Ewing tumors are extremely aggressive clinically, EWS/FLI-1 possesses only weak transforming activity in a traditional NIH 3T3 transformation assay (45). Moreover, its expression appears to be toxic to many primary cultured cells, suggesting that cellular context may be critical for the tumorigenic effects of EWS/FLI-1 (17). The cellular origin of Ewing tumors remains unknown, but recent studies suggest that this cell may be a progenitor associated with bone (13, 60, 71). In a previous study, we showed that expression of EWS/FLI-1 inhibits osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitors isolated from mouse bone marrow (71), implying that inappropriate expression of EWS/FLI-1 during embryogenesis may lead to developmental defects and lethality.

Although Ewing tumors are relatively rare, the fusion of TET proteins with different classes of transcription factors via chromosomal translocation is a common genetic mechanism to generate novel oncogenes in sarcomas (4). EWS and TLS can be functionally interchangeable in the context of fusion oncogenes, as shown by the identification of EWS/ERG and TLS/ERG fusions in Ewing tumors and TLS/CHOP and EWS/CHOP fusions in myxoid liposarcoma. ETS proteins have also been implicated in leukemogenesis in several contexts. Viral activation of Fli-1 (Friend leukemia virus integration 1) is a hallmark of Friend-induced and 101A murine leukemia virus-induced leukemias in mice (9, 54). In humans, ERG gene amplification has been detected in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with complex karyotypes (8). Interestingly, while the TET-transcription factor fusions are primarily found in sarcomas, TLS/ERG translocations found in Ewing sarcoma have also been identified in rare cases of acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia, indicating that this class of fusion protein can also contribute to leukemia (29-32, 54, 55).

To determine how EWS/FLI-1 promotes tumorigenicity in vivo, we engineered mice with a Cre-inducible EWS/FLI-1 knocked into the ubiquitous Rosa26 locus (79). This locus has been well characterized and has been used to drive expression of a Cre-inducible β-galactosidase (β-Gal) reporter in mice (66). In this study, we show that expression of EWS/FLI-1 from Rosa26 induces a rapid expansion of primitive myeloid progenitors leading to leukemia that is transplantable to naïve recipients and reminiscent, but distinct from, Friend murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV)-induced erythroleukemias in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Rosa26 loxP-stop-loxP EWS/FLI-1 KI mice.

The reagents to target the murine Rosa26 locus were a kind gift of Philippe Soriano (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA). We modified the original Rosa26-1 targeting vector (66) by replacing a unique Xba1 site on the plasmid with a Pac1 site. Hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged EWS/FLI-1 (type I) (45) was then subcloned downstream of a splice acceptor-loxP-neomycin-4xPA-loxP cassette (loxP-STOP-loxP) and introduced to the Pac1 site of the modified Rosa26-1 plasmid (see Fig. 1A, below). The final Rosa26 EWS/FLI-1 knock-in (KI) construct was electroporated into W9.5 embryonic stem (ES) cells, and colonies were isolated after 10 days of G418 selection. Colonies that had undergone homologous recombination at the Rosa26 locus were identified by digesting ES cell genomic DNA with EcoRV and Southern blotting using the previously described 150-bp probe, 5′ to the Rosa26 promoter (66). From 90 screened colonies, 30 were positive, consistent with the high rate of recombination previously observed at this locus (66). Three positive clones with normal karyotypes were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts, which were then implanted into pseudo-pregnant mice to generate chimeric animals. Five animals with high-percentage chimerism were bred to C57BL/6 mice to screen for germ line transmission of the Rosa26loxP-STOP-loxP-HA-EWS/FLI-1 allele, hereafter referred to as E/F. Mice harboring the E/F allele were routinely genotyped by PCR using primers that discriminated between the endogenous Rosa26 and E/F alleles: 5′-GAGTTGTTATCAGTAAGGGAGC-3′, 5′-ACACACCAGGTTAGCCTTTAAG-3′, and 5′-GATCCACTAGTTCTAGAGCGGC-3′.

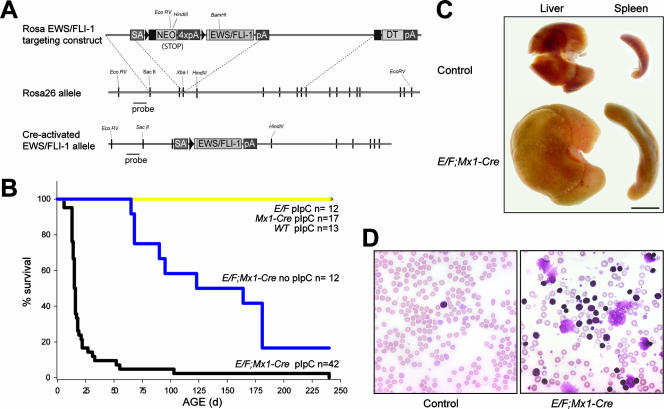

FIG. 1.

Rosa E/F; Mx1-cre mice treated with pIpC show severe pathology. (A) Construction of Cre-inducible Rosa EWS/FLI-1 targeting vector. HA-tagged EWS/FLI-1 was placed downstream of a splice acceptor (SA)-loxP-stop-loxP cassette. loxP sites are shown as triangles. The construct was then introduced into W9.5 ES cells and the cells selected with G418. A probe outside the arms of homology was used to screen ES clones for the knock-in allele. The active EWS/FLI-1 allele is produced by Cre-mediated recombination between loxP sites, thereby removing the stop cassette. (B) Survival of E/F; Mx1-cre mice following treatment with 500 μg pIpC at postnatal days 2 to 3. Greater than 80% of E/F; Mx1-cre mice died before 25 days of age, while no mortality or pathology was observed in pIpC-treated controls with genotypes E/F or Mx1-cre, or nontransgenic littermates. Untreated E/F; Mx1-cre mice showed delayed pathology and mortality compared to treated mice. (C) Photograph of spleens and livers collected from pIpC-treated E/F (control) and E/F; Mx1-cre littermates sacrificed at 19 days of age. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were consistently found in moribund E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Bar, 0.5 cm. (D) Presence of elevated nucleated cells in peripheral blood smears of pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice analyzed at 16 days of age. Blood from a pIpC-treated E/F mouse is shown as a control. Magnification, ×400.

Cre recombinase induction and bromodeoxyuridine in vivo labeling in Mx1-cre mice.

Mx1-cre mice on a pure C57BL/6 background were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred with E/F mice to generate E/F;Mx1-cre mice. Expression of Cre recombinase in mice carrying the Mx1-cre transgene was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection at postnatal day 2 to 3 with 500 μg of polyinosinic·poly(C) (pIpC; Sigma Corp., St. Louis, MO) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline. For bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in vivo labeling experiments, mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (Sigma Corp.) at a dose of 50 μg/g of body weight. Tissue was harvested after 2 h, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and processed for frozen sections. Detection of BrdU incorporation in tissue sections was performed as previously described (23). All procedures involving mice were performed according to St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols.

Histological, cytochemical, and immunohistochemical analyses.

May-Grünwald-Giemsa-stained blood smears and cell cytospins were prepared by standard techniques. Tissues from pIpC-treated mice were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or processed for immunohistochemistry (IHC). IHC tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies to Gata-1 (1:250; N-6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), GR-1 (0.1 μg/ml; RM3000; Invitrogen Corp. Carlsbad, CA), CD3 (1:400; sc-1127; Santa Cruz), CD45R/B220 (1:200; PharMingen), CD45 (1:400; 553076; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA), myeloperoxidase (1:500; A0398; DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA), factor VIII (1:500; A0082; DAKO Corp.), lysozyme (1:600; A0099; DAKO Corp.), Mac2 (1:2,000; ACL-8942AP; Accurate Antibodies, Westbury, NY), TdT (1:20; Supertechs Inc., Rockville, MD), TER119 (1:500; 553671; BD PharMingen), Ki67 (1:5,000; NCL-Ki67p; Novacastra Labs, Newcastle, United Kingdom), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (1:1,000; sc-56; Santa Cruz), BrdU (1:200; Bu20a; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), and active caspase 3 (0.5 μg/ml; 559565; BD PharMingen). Detection of antibody reactivity was performed using the VECTASTAIN ABC system with the oxidation of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for visualization. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Vector Labs). The level of apoptosis was determined by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining using an ApopTag plus peroxidase in situ apoptosis detection kit (S7101; Chemicon) following the manufacturer's instruction. 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside staining was performed on 10-μm-thick frozen sections as previously described (23).

Molecular and biochemical analyses.

To isolate genomic DNA for Southern blotting analysis, tissue was digested in Laird buffer (40) containing proteinase K and incubated at 55°C for 16 h. Phenol-chloroform-purified genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV and HindIII, fractionated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and blotted onto nylon membranes (Magnaprobe; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Reverse transcription of total RNA, probe hybridization of DNA blots, and immunoblotting were performed as previously described (71). Tissues or cells were homogenized in 1% NP-40, 1% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na-phosphate, pH 7.2, containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Proteins were resolved on 7% polyacrylamide-Tris-acetate gels (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), transferred onto a nitrocellulose support, and incubated with antisera against HA epitope tag (1:500; 3F10; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), Fli-1 (1:1,000; C-19; Santa Cruz), or β-actin (1:5,000; Sigma Corp.). Proteins were also resolved on a 4 to 12% polyacrylamide-bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen Corp), transferred to a nitrocellulose support, and incubated with antisera against p16Ink4a (1:500; M-156; Santa Cruz), p18Ink4c (1:2,000; 39-3400; Zymed), p19Ink4d (1:500; M-167; Santa Cruz), p21 (1:500; F-5; Santa Cruz), p27 (1:500; M-197; Santa Cruz), phospho-AKT (Ser473; 1:1,000; 9271; Cell Signaling), active caspase 3 (0.5 μg/ml; 559565; BD PharMingen), Cdk4 (1:500; sc-260; Santa Cruz), Cdk6 (1:500; sc-177; Santa Cruz), cyclin D1 (1:1,000; 2926; Santa Cruz), cyclin D2 (1:500; sc-452; Santa Cruz), cyclin D3 (1:2,000; 610279; BD Biosciences), Gata-1(1:750; N-6; Santa Cruz), c-Myc (1:700; sc-764; Santa Cruz), phospho-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; 1:1,000; 9101; Cell Signaling), p44/42 MAPK (1:1,000; 9102; Cell Signaling), phospho-Rb (Ser608; 1:1,000; 2181; Cell Signaling), Rb (1:1,000; 9309; Cell Signaling), phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (Ser235/236; 1:1,000; 2211; Cell Signaling), and β-actin. Blots were then incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase and visualized by using the Supersignal chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). EWS/FLI-1 expression was detected in 13 ng of reversed-transcribed total RNA by real-time PCR analysis using the amplification primers 5′-GCCAAGCTCCAAGTCAATATAGC-3′ and 5′-GGACTTTTGTTGAGGCCAGAAT-3′ and the Taqman probe 5′-CCATGCTCCTCTTCTGACTGAGTCATAA-3′. The amplification primers 5′-GATAAGCTGGCCGCTCTAGAAC-3′ and 5′-CAGACTGCCTTGGGAAAAGC-3′, and Taqman probe 5′-CCCTACCCGGTAGAATTCCTGCA-3′ were used to quantitate the level of the unrecombined Rosa E/F knock-in allele.

qPCR primers used to detect erythropoietin receptor, Gata-1, Gata-2, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, Nkx2-2, c-Mpl, HoxA9, carbonic anhydrase VII, nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2, stem cell ligand (Tal-1), Runx1, ID2, p19 (Arf), and Tp53 genes are listed in Table S7 of the supplemental material. PCR and data analyses were performed on a 7900 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). EWS/FLI-1 levels were normalized to ribosomal 18S RNA abundance (Applied Biosystems).

Blood profiles, flow cytometry, and magnetic sorting.

A complete blood cell count of EDTA-treated peripheral blood was performed using a Hemavet 3700R (Drew Scientific, Oxford, CT). For surface antigen analysis, splenocyte suspensions were prepared by disaggregating spleens over a 40-μm mesh (BD Falcon, San Jose, CA) and depleting the resulting suspensions of red blood cells by incubating cells in Gray's balanced solution (Sigma Corp). Cells were then washed in Hanks buffered salt solution (Invitrogen Corp.) and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.2% bovine serum albumin prior to staining with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies or appropriate isotype controls (all antibodies were from BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). Propidium iodide or 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole was added to discriminate between dead and live cells. Analysis of stained cells was performed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), common lymphoid progenitors (CLP), and common myeloid progenitors (CMP) were fractionated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using the methodologies developed by Weissman and coworkers (2, 38). Briefly, bone marrow from crushed bones and spleen preparations were stained for lineage markers (CD3e or CD5, CD11b, CD45R/B220, Ly-6G, Ly-6C, and Ter-119 [Ly-76]), CD127 (IL-7Rα), SCA1, and c-Kit (BD PharMingen). CLP were isolated with the marker profile of Lin− IL-7Rα+ SCA1lo c-Kitlo; HSC were isolated with a marker profile of Lin− IL-7Rα− SCA1+ c-Kit+; CMP-like cells were isolated with a marker profile of Lin− ILRα− SCA1− c-Kit+ (2, 38). Lineage-negative, c-Kit+ splenocytes were isolated by magnetic-activated cell sorting. Briefly, splenocyte suspensions were first depleted of cells expressing CD5, B220, CD11b, Gr-1, Ly-6G/C, 7-4, and Ter-119 markers using a murine lineage depletion kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Enrichment of c-Kit-positive cells was then achieved by incubating the lineage-negative fraction with anti-c-Kit microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), passing labeled cells through a magnetic field, and eluting the retained cells. Successful purification of Lin− c-Kit+ cells was verified by FACS.

Transplantation experiments.

C57/129 recipient mice were sublethally irradiated at 4 to 6 weeks of age with a single dose of 800 cGy cesium. NOD/SCID mice and irradiated recipients were then injected with 4 × 106 to 10 × 106 spleen cells in 500 μl phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 10 units/ml of heparin (Sigma Corp.) into the dorsal tail vein. Recipient mice received the oral antibiotics sulfamethoxasole and trimethoprim in their drinking water. Mice were monitored daily for signs of pathology.

Gene expression profiling.

Total RNA was prepared from frozen tissue or sorted cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Integrity of RNA samples was confirmed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer Lab-on-a-Chip system (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Target cDNA preparation and hybridization to Mouse Genome 430 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA) were performed as previously described (62). Mouse Genome 430 2.0 arrays contain 45,000 probe sets representing more than 39,000 transcripts and variants from over 34,000 well-characterized mouse genes. Hybridized arrays were scanned using a GeneChip scanner 3000 (Affymetrix), and data were acquired and analyzed using GeneChip operating software. Gene expression data were normalized using the MAS5 algorithm and analyzed with Bioconductor version 1.8 (www.bioconductor.org). To limit false positives, probe sets that generated absent calls, as defined by the MAS5 algorithm, in more than half of the samples from a single group (e.g., whole-spleen E/F; Mx1-cre) and probe sets with greater than 75% absent calls across all groups were not used in downstream analysis. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of expression profiles was based on the top 1,000 most variable probe sets selected using the median absolute deviation value. We utilized the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis tools v. 4.0 (www.ingenuity.com) to determine interaction networks and functional/pathway categories of differentially regulated genes based on gene-to-gene interactions collated from the literature and stored in the company's “Knowledge” base.

Cell lines.

The Ewing tumor cell lines were grown in α-MEM (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, MD) with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for TC252 cells and 10% FBS in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) for A673 cells. NIH 3T3 cells were grown in 10% FBS in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. NIH 3T3 cells were transduced with EWS/FLI-1-expressing retrovirus as previously described (71). Murine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells, a kind gift from Paul Ney (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN), were maintained in 10% Iscove's MEM (Invitrogen). F-MuLV-derived MEL cells, CB3 and HB22.2, grown in 10% α-MEM, were a kind gift from Yaacov Ben-David (University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells were isolated and cultured as previously described (71). All tissue culture media contained 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

RESULTS

Construction of mice with a Cre-inducible EWS/FLI-1 allele.

To bypass potential toxicity associated with expressing EWS/FLI-1 during development, we engineered a targeting vector that introduced a Cre-inducible EWS/FLI-1 allele to the Rosa26 locus in ES cells (Fig. 1A). Rosa26 is ubiquitously expressed but does not encode a protein (79). This locus has been exploited to drive the ubiquitous expression of a Cre-inducible β-galactosidase reporter (66). Expression of Cre recombinase mediates deletion of a stop cassette and allows expression of the reporter in cells with Cre activity, as well as all of their progeny. This is a powerful system to detect Cre-mediated recombination when Rosa26 reporter mice (Rosa26R) are crossed with tissue-specific Cre lines. We replaced the β-galactosidase cassette of the original Rosa26 targeting vector (66) with an HA-tagged EWS/FLI-1 cDNA (Fig. 1A) such that Cre-mediated deletion of the stop cassette would induce expression of the EWS/FLI-1 transgene (Fig. 1A). This construct was used to generate E/F mice as described in Materials and Methods.

Activation of EWS/FLI-1 in E/F; Mx1-cre mice leads to a rapid hematological disease and death.

While the cell of origin of Ewing tumors is unknown, most of these tumors arise in bone, and cultured bone or bone marrow progenitors expressing EWS/FLI-1 display some features of Ewing tumor cells (13, 60, 71). In addition, knock-down of EWS/FLI-1 expression in Ewing tumor cell lines results in gene expression profiles similar to cultured mesenchymal progenitors derived from bone marrow (70). Numerous studies have shown that bone marrow contains stem cells that give rise to multipotent progenitors when these cells are grown in vitro. A common precursor of both hematopoietic and mesenchymal lineages may exist within bone marrow (20, 53, 57), making bone marrow a very relevant site to assess the oncogenic effects of EWS/FLI-1. To target expression of EWS/FLI-1 to the bone marrow compartment, we crossed E/F mice with Mx1-cre mice, in which Cre activity is strongly induced in bone marrow, liver, spleen, and other hematopoietic tissues, following administration of alpha/beta interferon or pIpC (39). Double transgenic E/F; Mx1-cre mice were born to heterozygous parents at the expected Mendelian ratios and showed no obvious abnormalities at birth. However, when E/F; Mx1-cre mice were treated with a single dose of pIpC at postnatal day 2 to 3, they rapidly developed severe pathology with a median age to death of 16 days (n = 42) (Fig. 1B). Overtly diseased mice displayed distended abdomens, pale footpads, hunched posture, ruffled fur, and lethargy. No evident pathology or death was observed in E/F, Mx1-cre, or wild-type mice following pIpC treatment (Fig. 1B). Necropsy of moribund E/F; Mx1-cre animals revealed pallid bone marrow in the long bones and the sternum as well as pronounced hepatomegaly and splenomegaly (Fig. 1C). The liver and spleen sizes of induced E/F; Mx1-cre mice were significantly enlarged (3.3- and 12.8-fold, respectively) in comparison to pIpC-treated mice without Cre (controls) (Table 1). Untreated E/F; Mx1-cre mice developed a similar pathology as pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice but with a much-delayed onset, presumably due to low levels of leaky Cre activity. The median age of death was 95 days (Fig. 1B). Background levels of leaky Cre activity without pIpC administration due to normal production of interferon in mice has been reported previously in studies using Mx1-cre mice (14, 27, 41, 47). Induced E/F; Mx1-cre mice also had elevated nucleated cell counts in peripheral blood, with low hematocrit and red blood cell counts (Table 2). Platelet levels were slightly elevated in E/F; Mx1-cre mice (Table 2). Blood smears showed an abnormal presence of immature blasts (Fig. 1D), suggesting deregulation of the hematopoietic compartment in pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice.

TABLE 1.

Organ weights

| Exptl group | n | Relative organ wt (g)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Spleen | ||

| Controla | 18 | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| E/F; Mx1-cre | 15 | 14.0 ± 3.4 | 6.4 ± 2.1 |

Pooled from E/F, Mx1-cre, and wild-type mice.

b Data for relative organ weights (organ weight relative to body weight) are averages ± standard deviations.

TABLE 2.

Blood profiles

| Exptl group (n) | Avg ± SD

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (1,000/μl) | Red blood cells (106/μl) | Hematocrit (%) | Platelets (1,000/μl) | |

| Controla (27) | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 6.4 ± 1.5 | 37 ± 7 | 399 ± 149 |

| E/F; Mx1-cre (35) | 80 ± 68 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 15 ± 3 | 515 ± 223 |

Pooled from E/F, Mx1-cre, and wild-type mice.

Proliferation of blast cells in spleen, liver, and bone marrow of E/F; Mx1-cre mice.

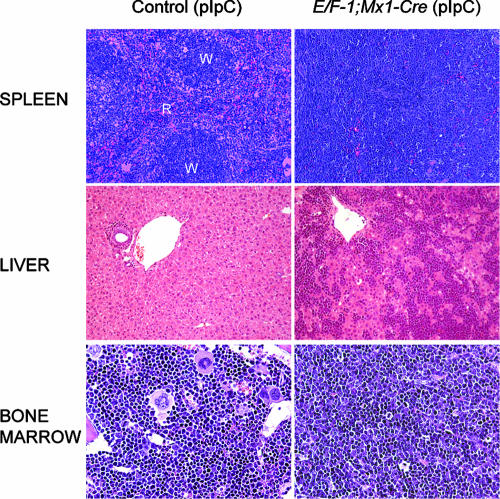

Histological examination of spleens, livers, and bone marrow from diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice revealed proliferation of primitive mononuclear cells which disrupted the normal splenic, hepatic, and bone marrow architectures (Fig. 2). There was a noticeable decrease in lymphoid follicles and marked expansion of the splenic red pulp with immature myeloid cells. This immature population did not express Gr-1, CD3, CD45R/B220, CD45, myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, Mac1, Mac2, TdT, factor VIII, or Ter-119 as determined by immunohistochemistry, indicating that proliferating cells were not mature lymphoid, myeloid, or erythroid cells (data not shown). Consistent with their immature appearance, 30 to 50% of these cells were positive for the stem cell marker c-Kit (data not shown) and >75% were positive for the transcription factor Gata-1 (Fig. 3A). We also verified expression of Gata-1 in spleens and livers of diseased mice by Western blotting (Fig. 3B). c-Kit is present on hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors (37), while Gata-1 is expressed in early erythroid and myeloid progenitors (44). Thymus and lymph nodes were unremarkable in all diseased animals examined. In the bone marrow compartment, normal maturation of myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic lineages was observed, with focal areas of infiltration by Gata-1+ and c-Kit+ immature myeloid cells (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Mononuclear cell infiltration of spleen, liver, and bone marrow of E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Results of histological examination of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections from paraffin-embedded tissue are shown. The normal architecture of the spleen observed in pIpC-treated Mx1-cre or E/F (control) mice is disrupted by the presence of primitive mononuclear cells in pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice. The white pulp (W), the lymphoid component of the spleen, is markedly reduced, while the red pulp (R) is greatly expanded by a myeloid/erythroid component, resulting in the homogeneous appearance of the spleen in pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice compared to controls. The livers and bone marrow of pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice were infiltrated by primitive mononuclear cells. Mice shown were analyzed at 17 days of age. Magnification, ×200 for spleen and liver sections and ×500 for bone marrow.

FIG. 3.

Expression of Gata-1 in tissues from E/F; Mx1-cre mice. (A) Gata-1 immunohistochemistry was performed on tissue sections from pIpC-treated Mx1-cre (control) and E/F; Mx1-cre mice. In control mice, the myeloid/erythroid marker Gata-1 is present in the red pulp of the spleen, while it is absent in the livers of these animals. However, strong staining of Gata-1 is observed in infiltrating mononuclear cells in spleens and livers of E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Note the exclusion of Gata-1 staining in lymphoid cells in the spleen. Mice were analyzed at 15 days of age. Magnification, ×50. (B) Gata-1 was detected in 30 μg total cellular protein from F-MuLV cells, K562 (CML) cells, livers and spleens of a pIpC-treated Mx1-cre mice (control), and pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice (23 days old) using Gata-1 (N6) antiserum. Note the strong detection of a 50-kDa band in F-MuLV and control spleen lysates, while this band was weakly detectable in K562 cells and absent in control liver lysates. Gata-1 was strongly detected in livers of E/F; Mx1-cre mice, consistent with the presence of Gata-1+ malignant cells, as shown as by Gata-1 immunohistochemistry on liver tissue sections from diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Gata-1 was also strongly detected in spleen lysates from E/F; Mx1-cre mice. The blot was stripped and reprobed with β-actin antiserum.

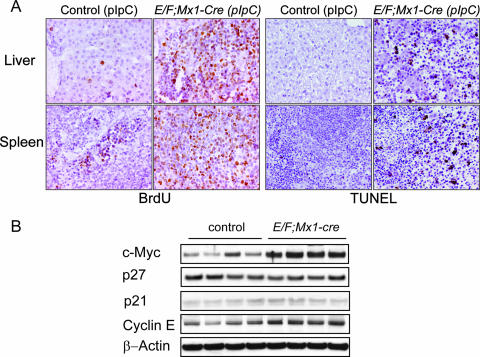

We performed in vivo BrdU labeling experiments to determine if proliferation was the underlying mechanism for the expansion of malignant cells in diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Following a 2-h pulse, significant incorporation of BrdU was evident in infiltrating cells present in spleens and livers of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice (Fig. 4A). In comparison, we observed few BrdU-positive hepatocytes in livers or myeloid cells in spleens of control mice. We obtained concordant results by immunostaining tissue sections of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice with the proliferation markers Ki67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (data not shown). These experiments clearly demonstrate that malignant cells are actively proliferating.

FIG. 4.

Proliferation and apoptosis in livers and spleens of E/F; Mx1-cre mice. (A) To determine actively proliferating cells in E/F (control) or E/F; Mx1-cre mice, 14-day-old mice were injected with BrdU and tissues were analyzed after a 2-h pulse. Infiltrating cells present in the spleens and livers of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice showed significant incorporation of BrdU, indicating malignant cells were actively proliferating. In contrast, BrdU incorporation was observed in few hepatocytes in livers and scattered myeloid cells in spleens of control animals. Magnification, ×400. TUNEL staining in spleens and livers of control or E/F; Mx1-cre mice is shown on the right. Numerous TUNEL-positive cells are observed in infiltrating cells present in livers and spleens of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice (18 days old). In contrast, no TUNEL-positive cells were observed in livers and scattered positive cells were observed in spleens of Mx1-cre mice (controls). Magnification, ×200. (B) c-Myc, p27, p21, and cyclin E were detected in 30 μg total cellular protein from the spleens of E/F; Mx1-cre or E/F (control) mice 4 days after treatment with pIpC. Note the strong upregulation of c-Myc in four E/F; Mx1-cre mice derived from the same litter. Detection of β-actin on the same blots is shown as a loading control.

To determine if a decreased rate of apoptosis could also contribute to the expansion of malignant cells, we performed TUNEL staining on liver and spleen sections of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice. As shown in Fig. 4A, we observed marked apoptosis in infiltrating cells present in spleens and livers of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice, unlike control mice, in which we were unable to detect TUNEL-positive cells in liver and were able to detect only a few scattered positive cells in the myeloid compartment of the spleen. We also stained sections for active caspase 3 and observed significant numbers of active caspase 3-positive cells in the spleens and livers of diseased mice but not control mice (data not shown). Thus, the expansion of malignant cells in diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice is due to enhanced proliferation and not due to decreased apoptosis.

To further characterize the proliferation of the malignant cells in E/F; Mx1-cre mice, we examined expression of proteins associated with proliferation and cell cycle regulation in spleen lysates from diseased mice. There was a marked increase in c-Myc expression in spleens of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice relative to control mice. Increased levels of Cdk4 and -6 and cyclins D1 and E and decreased levels of the cell cycle inhibitory proteins p16Ink4a and p27, along with increased phosphorylation of Rb1, were also detected in spleen lysates from diseased mice, consistent with the proliferative nature of the malignant cells (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We did not detect enhanced activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase or MAPK pathways, as assessed by Western blot analysis of phospho-Akt and phospho-S6 and of phospho-p42/44 MAPK, respectively (not shown). Enhanced c-Myc expression may play a role in driving proliferation as well as apoptosis; therefore, we also evaluated an earlier time point in disease development. Increased c-Myc expression was detected clearly in whole spleens 4 days after pIpC treatment (Fig. 4B), at a stage when a small population of Cre-activated cells were beginning to expand in spleens of E/F; Mx1-cre mice without overt signs of compromised health. At this time point, no appreciable changes in the levels of cyclin E or of the cell cycle inhibitors p27 or p21 were detected (Fig. 4B).

Activation of EWS/FLI-1 in E/F; Mx1-cre mice induced leukemia, as defined by the Bethesda proposals for the classification of hematopoietic neoplasms in mice. Murine nonlymphoid leukemia is defined by (i) diffuse involvement of hematopoietic tissue particularly spleen and bone marrow, (ii) anemia, neutropenia, and/or thrombocytopenia, (iii) an increase in myeloid cells in spleen and/or bone marrow, (iv) dissemination of neoplastic cells, and (v) 20% of immature forms/blasts in peripheral blood, spleen, or bone marrow. The disease induces rapid fatality in primary animals and/or transplantability to naïve recipients (35). The pathology in E/F; Mx1-cre mice met all of the defining criteria of nonlymphoid leukemia.

Malignant cells in E/F; Mx1-cre mice express the cell surface markers c-Kit, CD43, and CD71.

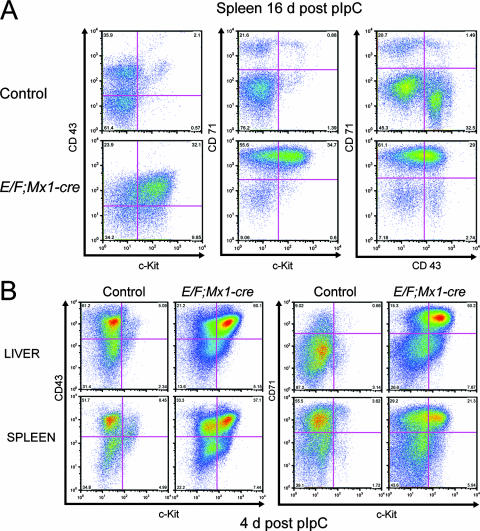

We further characterized the cell surface epitopes on malignant cells in E/F; Mx1-cre mice using FACS analysis of spleen preparations from diseased and control mice. Consistent with immunohistochemical analyses, spleen preparations from diseased animals were not enriched for cells expressing mature T- and B-cell markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, Thy1.2, CD19, CD21, CD23, immunoglobulin M, immunoglobulin D, and B-220) or mature erythroid and myeloid cell markers (Ter-119, Gr-1, Mac1, CD41, CD31, F4/80, and CD16-32). These cells were also CD45 dim. Spleen preparations were also negative for the stem cell markers SCA1 and CD34. In addition, we did not observe enrichment of lineage-negative, CD127 (IL-7αR)-positive cells in spleens or bone marrow of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice, suggesting that malignant cells were not of an early lymphoid origin (data not shown). However, spleen preparations were enriched for cells expressing c-Kit, CD43, and transferrin receptor (CD71) compared to control spleen preparations (Fig. 5A). The disease arising in uninduced E/F; Mx1-cre mice (Fig. 1B) also showed the same histopathological features, Gata-1 expression, and c-Kit/CD43/CD71 cell surface profiles, demonstrating similar pathology but with prolonged latency associated with leaky Cre activity (data not shown). The transferrin receptor is expressed across hematopoietic lineages but highly expressed in immature erythroid cells (50, 67). CD43 is expressed in early hematopoietic cells and myeloid and lymphoid precursors (73). Enrichment of c-Kit+/CD43+/CD71+ cells was evident as early as 4 days after the initial pIpC treatment in both the spleens and livers from E/F; Mx1-cre mice (Fig. 5B, upper right quadrants) but appeared to be much more pronounced in the liver. Interestingly, a population of c-Kit dim/CD43+ cells was also present in spleens and livers of control mice at this age (Fig. 5B, upper left quadrants, left panels). This population of cells present in young mice may give rise to the malignant cells found in moribund E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Histological examination of hematopoietic tissue of E/F; Mx1-cre mice 4 days after pIpC treatment revealed the presence of multiple large foci of blast cells expressing Gata-1 and c-Kit in the liver but not in spleen or bone marrow (data not shown), suggesting that the liver may be the initial site of malignant cell expansion.

FIG. 5.

Enrichment of c-Kit/CD43/CD71-positive cells in spleens and livers of E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Spleen and liver cells were stained with fluorescently labeled c-Kit, CD43, and CD71 antibodies and analyzed by FACS. (A) Spleens from pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice were enriched in cells coexpressing c-Kit, CD43, and CD71. The same population of cells was also present in spleens of pIpC-treated control mice, but at a much lower frequency. Mice were analyzed 16 days after pIpC treatment. (B) Expansion of c-Kit+ CD43+ and c-Kit+ CD71+ cells is evident in spleens and livers of 7-day-old E/F; Mx1-cre mice, 4 days after pIpC treatment. c-Kit dim CD43+ and C-kit dim CD71+ cells are present in livers and spleens of control mice and may be the origin of the malignant cells in E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Control mice were pIpC-treated E/F mice.

Leukemia in E/F; Mx1-cre mice can be transplanted to naïve recipients.

Expansion of primitive myeloid mononuclear cells in spleen, liver, and eventually bone marrow of pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-Cre mice leading to severe anemia and rapid death of these animals is consistent with the criterion defining nonlymphoid neoplasia in mice (35). Expression of Gata-1, c-Kit, CD43, and CD71 and morphology allow the classification of the leukemia in E/F; Mx1-cre mice as myeloid/erythroleukemia. To determine if leukemia in E/F; Mx1-cre mice could be transplanted to naïve recipients, we injected spleen cells from diseased animals into allogeneic sublethally irradiated recipients. In four separate experiments, 19/26 animals developed severe anemia, splenomegaly, and pallid bones leading to death (Table 3). The latency of disease in recipient mice varied from 22 to 125 days with a median time of 87 days. The remaining mice (7/26) did not develop pathology within 6 months or died with no gross evidence of disease. Transplantation of control spleen cells failed to generate disease in recipient mice (n = 7). We further tested the ability of E/F; Mx1-cre spleen cells to be transplanted serially. Spleen cells from two separate diseased transplanted mice from different experiments were injected into seven allogeneic sublethally irradiated recipients and six NOD/SCID mice. We used immunocompromised NOD/SCID mice to determine if leukemic cells from transplanted animals could engraft without the use of irradiation. From this group, 7/7 of the allogeneic recipient and 4/6 NOD/SCID mice developed a similar pathology to that of the donor mice with a latency that varied from 28 to 42 days with a median time of 37 days; two NOD/SCID mice died of unknown causes. We injected spleen cells from a sick NOD/SCID mouse into four additional NOD/SCID mice, which became diseased with a latency of 25 to 27 days. Histological analysis of spleen, liver, and bone marrow of the recipient mice revealed proliferation of primitive mononuclear cells similar to that observed in donor E/F; Mx1-cre mice. These cells were also positive for the proliferation marker Ki67, Gata-1, and c-Kit by IHC, and the spleens of these animals were enriched for c-Kit/CD43/CD71-positive cells, similar to donor mice (data not shown). The transplant recipients recapitulated a disease with characteristics similar to the primary disease in E/F; Mx1-cre mice, demonstrating that leukemia induced by the activation of EWS/FLI-1 is fully transplantable and suggesting that activation of EWS/FLI-1 is responsible for the oncogenic expansion of myeloid/erythroid progenitors in E/F; Mx1-Cre mice and transplant recipients.

TABLE 3.

Summary of serial transplant experiments

| Donor group and set | First transplant

|

Serial transplant

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia frequency | Latency (days) | Leukemia frequency | Latency (days) | |

| E/F; Mx1-cre donors | ||||

| Set 1 | 3/4 | 27-104 | ||

| Set 2 | 8/9 | 42-102 | 6/8 | 29-41 |

| Set 3 | 4/7 | 22-103 | ||

| Set 4 | 5/6 | 87-125 | 5/5 | 28-42 |

| Control donors | 19/26 | 87a | 11/13 | 37a |

| Set 5 (E/F) | 0/3 | |||

| Set 6 (Mx1-cre) | 0/4 | |||

Median value for the two control groups.

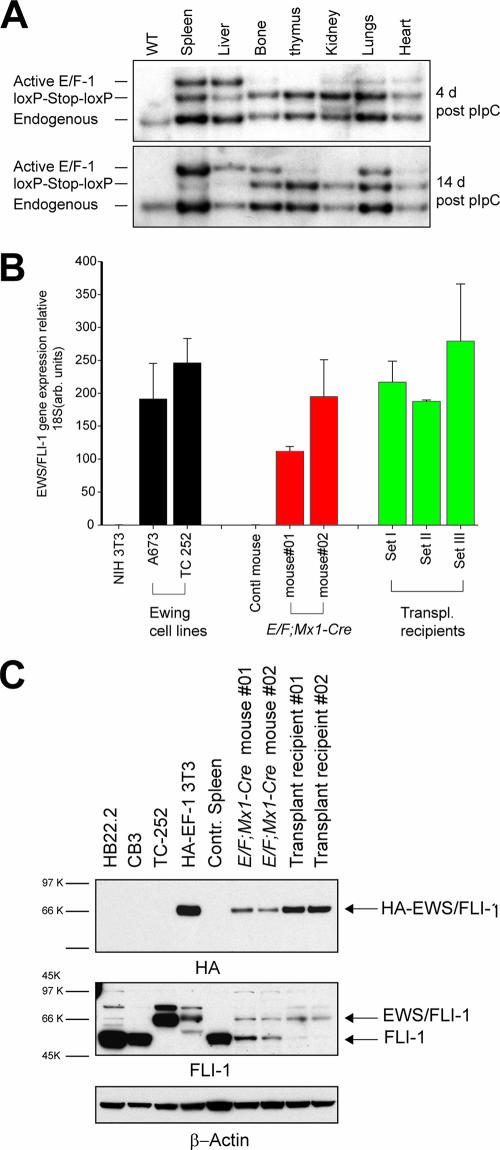

Expression of EWS/FLI-1 is associated with leukemic proliferation in E/F; Mx1-cre and transplanted recipient mice.

To determine how activation of EWS/FLI-1 resulted in the proliferation of primitive myeloid cells, we examined the pattern of EWS/FLI-1 expression in E/F; Mx1-cre mice after Cre activity was induced by pIpC treatment. We first performed Southern blot analysis to determine the relative level of Cre-mediated recombination in both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissue of pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice. At 4 days after pIpC treatment, the band representing the recombined, active Rosa EWS/FLI-1 allele was strongly visible in the spleen and liver and much weaker in bone and other tissues examined (Fig. 6A, active band). Correspondingly, the nonrecombined allele was reduced in spleen and liver (Fig. 6A, loxP-Stop-loxP band) in comparison to the endogenous Rosa26 allele (Fig. 6A). In diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice 14 days after pIpC treatment, the recombined allele was strongly present in spleen, liver, bone, and lungs (Fig. 6A) with little of the nonrecombined allele remaining in spleen and liver (Fig. 6A). We also observed recombination of the Rosa E/F KI allele in spleen, liver, and bone marrow of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice not treated with pIpC, suggesting that activation of EWS/FLI-1 caused disease in induced and uninduced mice (data not shown). We determined the relative induction of EWS/FLI-1 expression in diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Spleen, liver, and bone marrow showed the highest level of induction, consistent with the high degree of recombination observed in these tissues by Southern blotting (data not shown) and involvement of these tissues in leukemogenesis of E/F; Mx1-Cre mice. Detection of EWS/FLl-1 mRNA was also evident in all transplanted recipient mice assayed and appeared slightly higher than in E/F; Mx1-cre mice (Fig. 6B). This may be influenced by differences in the extent of leukemic infiltration in the spleen at the time the tissue was collected, as well as a slight increase in EWS/FLI-1 expression in the transplanted disease. The level of EWS/FLI1 mRNA found in E/F; Mx1-cre and transplanted recipient mice was also within the range of expression observed in Ewing tumor cell lines (Fig. 6B). We then compared EWS/FLI-1 protein levels in spleen lysates from pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice and transplanted mice. EWS/FLI-1 was readily detectable in protein lysates of transplanted mice (Fig. 6C), indicating that EWS/FLI-1-expressing cells caused transplantable leukemia. The levels of EWS/FLI-1 in both primary and transplanted mice were also much lower than EWS/FLI-1 in cultured Ewing tumor cells (TC252) as detected with FLI-1 antiserum (Fig. 6C). Endogenous levels of FLI-1 appear to be much reduced in EWS/FLI-1 diseased animals compared to control spleens, most likely because leukemic cells had infiltrated and replaced normal cell types that express higher levels of Fli-1 in spleen, including normal B cells and megakaryocytes (3, 46). Indeed, the levels of endogenous Fli-1 detected in lysates from E/F; Mx1-cre and transplanted recipient mice were similar to the level of Fli-1 present in primitive myeloid/erythroid cells (data not shown). It is noteworthy that the level of EWS/FLI-1 expression driving disease is substantially lower than the level of Fli-1 found in erythroleukemia cell lines made with F-MuLV (Fig. 6C, lanes CB3 and HB22.2), in which viral activation of Fli-1 drives the development of erythroleukemia (9). This indicates a much more potent effect of EWS/FLI-1 in leukemogenesis.

FIG. 6.

Cre-activated expression of EWS/FLI-1 from the Rosa26 locus. (A) Southern blot analysis of E/F; Mx1-cre mice 4 and 14 days after pIpC treatment to induce cre expression. DNA was extracted from wild-type tissue or the indicated tissues from pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice, digested with HindIII/EcoRV, and hybridized with a Rosa26 probe. The 3-kb band represents the endogenous Rosa26 allele. The “loxp-Stop-loxp” band (4.3 kb) represents the Cre-inducible EWS/FLI-1 allele. Deletion of the stop cassette results in the active EWS/FLI-1 allele, the 5.1-kb band. In E/F; Mx1-cre mice 4 days after pIpC treatment, strong Cre-mediated recombination was evident in spleen and liver. At 14 days after pIpC treatment, deletion of the stop cassette was almost complete in liver and spleen. Strong recombination was evident in leg bones and lungs. (B) Real-time RT-PCR was used to detect expression levels of EWS/FLI-1 mRNA in spleens from E/F; Mx1-cre mice 17 days after pIpC treatment and transplanted recipient mice. EWS/FLI-1 mRNA levels were normalized to ribosomal 18S. The relative levels of EWS/FLI-1 mRNA detected in two Ewing cell lines are shown for comparison. Nontransgenic spleen cells were used as a control. (C) Detection of EWS/FLI-1 protein in spleen (30 μg) lysates from primary (18- and 23-day-old mice) and transplanted recipient mice was performed using a biotinylated anti-HA antibody. Lysate from NIH 3T3 cells expressing HA-EWS/FLI-1 from a viral promoter was used as a positive control. The blot was stripped and reprobed using an antibody that detects the C terminus of FLI-1. Lysate from the Ewing cell line TC252 was used as a control for EWS/FLI-1. The blot was stripped and reprobed for β-actin.

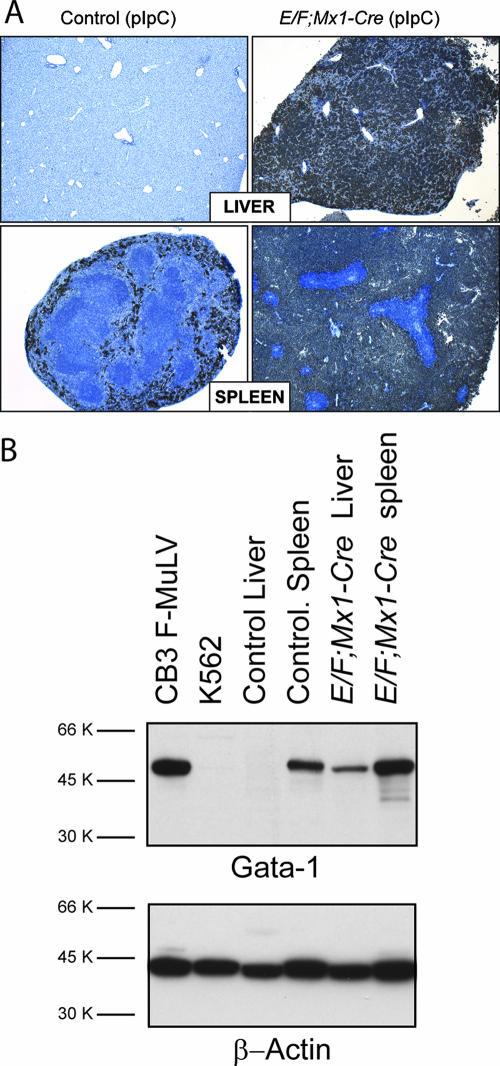

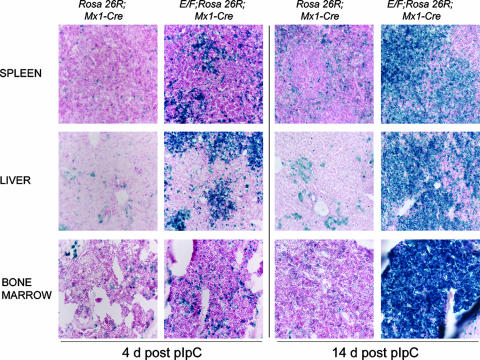

EWS/FLI-1 was difficult to detect by immunohistochemistry due to low expression levels. Therefore, we identified cells in which Cre-mediated recombination had occurred by assaying β-galactosidase activity in E/F; Mx1-cre mice crossed to Rosa26R reporter mice (66). Triple transgenic E/F; Mx1-cre; Rosa26R mice developed similar pathology to pIpC-treated E/F; Mx-1-cre mice in a similar time course. At 4 days after the initial pIpC injection, multiple large foci of cells containing Cre-mediated recombination (Fig. 7) were found in livers of E/F; Mx1-cre; Rosa26R mice, while much smaller foci of β-Gal-positive cells were observed in spleens. This expansion of β-Gal-positive cells in liver and spleen is also consistent with the enrichment of c-Kit/CD43/CD71+ cells observed by FACS analysis 4 days after pIpC treatment of E/F; Mx1-cre mice (Fig. 7). Scattered β-Gal-positive cells were observed in bone marrow sections (Fig. 7) and other tissues, such as kidney, thymus, and lung (data not shown). By comparison, only scattered Cre-activated cells were observed in livers, spleens, or bone marrow of Rosa26R; Mx1-cre control mice 4 days after pIpC treatment, with a slight increase observed at 14 days following pIpC treatment. The specific pattern of β-Gal activity and epitope expression observed 4 days after pIpC administration suggests that myeloid progenitors present in livers and spleens of E/F; Mx1-cre mice are susceptible to the oncogenic effects of EWS/FLI-1 activation, while in other cell types of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissues no obvious proliferative effects were observed by Cre-mediated activation of EWS/FLI-1. At 14 days after pIpC treatment, β-Gal-positive cells predominated in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow of E/F; Mx1-cre; Rosa26R mice, showing that Cre-mediated activation of EWS/FLI-1 drives the expansion of the leukemic cells in moribund animals.

FIG. 7.

Expansion of cells with Cre activity in E/F; Mx1-cre; Rosa26R mice. X-Gal staining of frozen sections of tissue from E/F; Mx1-cre; Rosa26R or Mx1-cre; Rosa26R (control) mice 4 and 14 days after pIpC treatement. At 4 days posttreatment, spleen, liver, and bone marrow cells of Mx1-cre; Rosa26R mice contained scattered X-Gal-positive (blue) cells, indicating deletion of the stop cassette and expression of the reporter. In contrast, livers and spleens of E/F; Mx1-cre; Rosa26R mice contained clusters of X-Gal-positive primitive mononuclear blast cells, and bone marrow of the same animal contained increased numbers of X-Gal-positive cells. At 14 days after pIpC treatment, a substantial increase in the relative numbers of X-Gal-positive cells was observed in all three tissues of E/F; Mx1-cre; Rosa26R mice, while control mice showed scattered blue cells in spleens, liver, and bone marrow. Magnification, ×200.

EWS/FLI-1 appears to drive the specific expansion of myeloid/erythroid progenitors in E/F; Mx1-cre mice. However, this effect could be due to the selective activation of EWS/FLI-1 in this type of hematopoietic cell. To determine the relative level of EWS/FLI-1 activation in stem cells and progenitor cells present in bone marrow and spleens of pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice, we developed a quantitative PCR assay to determine the relative level of Cre-mediated deletion of the stop cassette in the Rosa E/F knock-in allele. We isolated CLP, HSC, and mixed CMP cells by FACS (2, 38) from the spleens of E/F; Mx1-cre mice 4, 5, or 10 days after pIpC treatment. We then determined the relative level of recombination of the Rosa E/F knock-in allele in genomic DNA isolated from sorted cells. As shown in Table 4, we detected significant recombination in both early lymphoid and myeloid precursors as early as 4 or 5 days after a single pIpC treatment, with the highest level observed in CMP cells. We also observed a high level (53 to 77%) of recombination in HSC, indicating that induction of Cre activity was very efficient in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells that are present in the spleen at this age. In contrast, there was less recombination in lineage-committed hematopoietic cells. At 10 days after pIpC treatment, just before the time at which E/F; Mx1-cre mice present with pathology, the level of recombination was >75% in CLP and HSC, with the CMP cells showing close to 100% recombination of the Rosa E/F KI allele, coinciding with the emergence of malignant cells. Recombination in whole bone 4 days after pIpC treatment ranged from 3 to 17%. We were unable to derive enough cells from bone at 4 days post-pIpC treatment to isolate HSC, CLP, and CMP cells from the same mouse. However, at 5 days post-pIpC treatment, we observed recombination in CLP, HSC, and CMP cells, with CMP cells reaching close to 100% recombination by 10 days post-pIpC treatment. These experiments show that activation of EWS/FLI-1 was not limited to the myeloid lineage, suggesting cells of myeloid/erythroid lineage are particularly sensitive to the oncogenic effects of EWS/FLI-1.

TABLE 4.

Deletion of the stop cassette in hematopoietic cells from EF; Mx1-cre micea

| Tissue | Cell type | % Cre-mediated recombination at indicated day after pIpC treatment

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Spleen | CLP | 49 ± 2 | 30 ± 6 | 52 ± 6 | 39.2 ± 7 | 85.5 ± 5 |

| HSC | 77 ± 1 | 66 ± 1 | 53 ± 4 | 39 ± 5 | 76.2 ± 7 | |

| CMP mixed | 98 ± 1 | 99 ± 1 | 43 ± 2 | 82 ± 2 | 100 ± 2 | |

| Lineage positive | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 40 ± 3 | 82.8 ± 5 | |

| Whole bone | 11 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 17 ± 3 | |||

| Bone | CLP | 25 ± 2 | 14 ± 7 | |||

| HSC | 24 ± 10 | 81 ± 3 | ||||

| CMP mixed | 36 ± 2 | 100.0 ± 2 | ||||

| Lineage positive | 10 ± 3 | 52 ± 3 | ||||

Data shown (averages ± standard deviations) were derived from a single mouse at each time point.

Recent studies have suggested that bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPC) grown ex vivo may be sensitive to the oncogenic effects of EWS/FLI-1 (13, 60). However, the bone marrow cells in vivo that give rise to MPC ex vivo remain poorly characterized, making their direct isolation difficult. To determine indirectly if EWS/FLI-1 was activated in this stem or progenitor pool in vivo, we grew MPC from bone marrow of E/F; Mx1-cre mice 4 days post-pIpC treatment under conditions that did not promote the growth of hematopoietic cells (56). After 7 days of ex vivo culture, the level of recombination at the Rosa E/F KI allele in MPC ranged from 9 to 22% in cultures from five different mice, suggesting that EWS/FLI-1 was activated in vivo in this stem or progenitor pool.

Absence of recurrent chromosomal abnormalities or Tp53 mutations in EWS/FLI-1-induced leukemia.

Disease resulting from induction of EWS/FLI-1 occurred extremely rapidly, suggesting that EWS/FLI-1 expression induced a potent oligoclonal response rather than a monoclonal expansion involving the accumulation of additional mutations within a single evolving clone. Chromosomal abnormalities are frequently associated with clonal malignancies. To assess whether the transplanted leukemia represented a clonal evolution of the primary disease induced by EWS/FLI-1, we performed spectral karyotype analysis on spleen cells from pIpC-induced E/F; Mx1-cre mice with primary disease, uninduced E/F; Mx1-cre mice that developed disease with prolonged latency or transplanted disease. We were unable to detect any consistent chromosomal abnormalities in pIpC-treated or untreated E/F; Mx1-cre mice or transplanted recipient mice that we examined (n = 13) (data not shown). Although we cannot rule out clonal mutations that cannot be detected at the chromosomal level, the lack of recurrent abnormalities in transplanted disease is consistent with the notion that activation of EWS/FLI-1 in E/F; Mx1-cre leads to the oligoclonal expansion of leukemic cells. To determine if Tp53, commonly mutated in human cancers, was also affected in leukemia induced by EWS/FLI-1, we sequenced the open reading frame of Tp53 in diseased spleens from pIpC-induced E/F; Mx1-cre, disease that arose later in uninduced E/F; Mx1-cre mice and transplanted recipient mice. Tp53 was wild type in leukemias from E/F; Mx1-cre mice with primary disease and 90% (9/10) of transplanted mice, indicating that mutations in Tp53 are not a common feature of leukemias induced by activation of EWS/FLI-1 in myeloid/erythroid progenitors. We also did not detect deletions of the tumor suppressor gene Ink4a/Arf by quantitative PCR assay for exon 1β or exon 2 in spleen cells from diseased E/F; Mx1-cre (8/8) or transplanted (3/3) mice. Further, there was a low level of expression of exons 2 and 3 of the Ink4/Arf locus by array analysis, indicating that the locus was neither deleted nor induced, as might be expected in the context of a Tp53 mutation.

Gene expression profiling indicates that primary and transplanted EWS/FLI-1 leukemias are very similar.

Gene expression profiles provide a large-scale unbiased analysis of the transcriptome and can identify a molecular signature that differentiates one stage of tumor from another. This analysis is particularly relevant for EWS/FLI-induced leukemia, as EWS/FLI-1 functions as a transcription factor. Initially, we compared the expression profiles of unpurified spleen samples from diseased E/F; Mx1-cre (n = 5), transplanted recipients (n = 4), or control (n = 4) mice. There were 5,781 probe sets differentially regulated between E/F; Mx1-cre and control animals, while there were 6,144 probe sets differentially regulated between transplanted mice and control animals (false discovery rate [q] < 0.01) (for gene lists, see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Surprisingly, we found a minimal number (25; q < 0.01) of differentially regulated genes between E/F; Mx1-cre and transplanted recipient mice (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), suggesting that the initiating activation of EWS/FLI-1 in myeloid/erythroid progenitors induces a primary disease capable of transplantation without substantial additional changes.

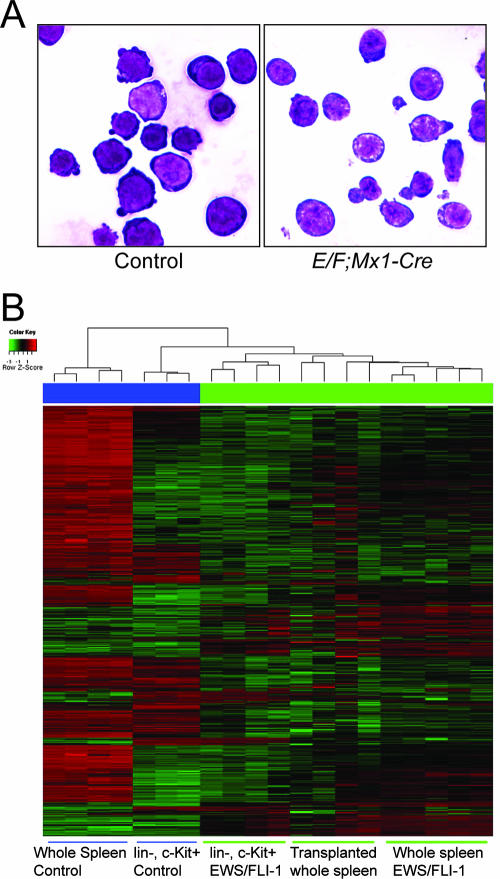

Leukemic cells from E/F; Mx1-cre mice expressed the stem cell marker c-Kit but did not express cell surface markers associated with specific hematopoietic lineage differentiation, suggesting that the leukemia may have arisen from a progenitor population. To compare the leukemia to a control population of cells with a similar differentiation profile, we isolated lineage-negative (Lin−), c-Kit+ cells from control and E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Spleen preparations were initially depleted of “lineage-positive” cells expressing CD5, B220, CD11b, Gr-1, Ly-6G/C, 7-4, or Ter-119. c-Kit+ cells were isolated from this Lin− fraction by magnetic-activated cell sorting as described in Materials and Methods. Lin− c-Kit+ spleen cells isolated from E/F mice without cre, 4 days after pIpC treatment, were used as controls. Based on FACS profiles, c-Kit+ cells were more enriched in spleens at this age than older control animals (Fig. 5). Lin− c-Kit+ cells represented less than 3% of total cells in control spleens (n = 3) and 36 to 47% of spleen cells in moribund E/F; Mx1-cre mice (n = 4). Cells from both control and E/F; Mx1-cre mice had a similar blast-like morphology (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Expression profiling of cells with EWS/FLI-1 activation. (A) Isolation of lineage-negative, c-Kit+ cells from E/F; Mx1-cre mice. A cytospin preparation of magnetically sorted spleen cells was stained with May-Grumwald-Giemsa. Lin− c-Kit+ cells from pIpC-treated E/F (control) or E/F; Mx1-cre mice show a blast-like appearance. Cells shown were isolated from 16-day-old mice. Magnification, ×1,000. (B) RNA was isolated from purified Lin− c-Kit+ cells or whole spleen tissue. Expression array data were generated on Affymetrix Murine 430 v. 2.0 chips. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the 1,000 most variable probe sets from control, E/F; Mx1-cre, and transplanted recipients and Lin− c-Kit+ cells from control and E/F; Mx1-cre (EWS/FLI-1) mice.

Comparison of gene expression profiles of Lin− c-Kit+ cells from control and E/F; Mx1-cre spleens showed 924 probe sets differentially regulated (q < 0.01), indicating that these cells were much more similar than comparisons with whole spleen, but still demonstrated substantial differences associated with EWS/FLI-1 activation. As expected, an unsupervised hierarchical clustering showed that EWS/FLI-1-induced leukemia from unpurified cells in primary or transplanted animals, or Lin− c-Kit+ purified cells, were closely related to one another and more similar to Lin− c-Kit+ control cells than to whole spleens from control animals (Fig. 8B). The 924 probe sets differentially regulated in Lin− c-Kit+ cells from E/F; Mx1-cre mice presumably represent genes important for the development of leukemia and potential target genes of EWS/FLI-1 in this cell background (see Table 5 for the top 40 most differentially regulated genes; see also Table S4 in supplemental material for a complete list). Pathway analysis using the Ingenuity Knowledge Base tools (www.analysis.ingenuity.com), which explore network interaction, function, and disease based on the published literature, revealed gene functions associated with cancer, cell morphology, cellular development, cell signaling, posttranslational modification, cell death, and gene expression (see Tables S5 and S6 in supplemental material for the complete list of categories and statistics), consistent with the development of leukemia in E/F; Mx1-cre mice.

TABLE 5.

Top 40 differentially regulated genes in cells with activated EWS/FLI-1

| Probe ID | Name | Description | Ratioa | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1427482_a_at | Car8 | Carbonic anhydrase 8 | 7.2 | 1.35E-12 |

| 1435749_at | Gda | Guanine deaminase | 5.3 | 3.24E-13 |

| 1427357_at | Cda | Cytidine deaminase | 5.2 | 5.17E-12 |

| 1448154_at | Ndrg2 | N-myc downstream regulated gene 2 | 5.1 | 2.45E-06 |

| 1441962_at | Alox5 | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase | 5.0 | 1.97E-11 |

| 1433715_at | Cpne7 | Copine VII | 5.0 | 1.35E-05 |

| 1423858_a_at | Hmgcs2 | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase 2 | 4.9 | 3.22E-06 |

| 1423294_at | Mest | Mesoderm-specific transcript | 4.7 | 5.06E-08 |

| 1420944_at | Zfp185 | Zinc finger protein 185 | 4.6 | 1.30E-09 |

| 1425570_at | Slamf1 | Signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 1 | 4.5 | 1.07E-04 |

| 1448954_at | Nrip3 | Nuclear receptor interacting protein 3 | 4.4 | 5.41E-06 |

| 1442166_at | Cpne5 | Copine V | 4.4 | 2.58E-07 |

| 1426887_at | Nudt11 | Nudix (nucleoside diphosphate-linked moiety X)-type 11 | 4.4 | 4.06E-09 |

| 1427221_at | Xtrp3s1 | X transporter protein 3 similar 1 gene | 4.2 | 1.22E-10 |

| 1419082_at | Serpinb2 | Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade B | 4.2 | 3.87E-05 |

| 1417837_at | Phlda2 | Pleckstrin homology-like domain, family A, member 2 | 4.1 | 8.35E-10 |

| 1422824_s_at | Eps8 | Epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate B | 4.0 | 4.96E-06 |

| 1417429_at | Fmo1 | Flavin-containing monooxygenase 1 | 4.0 | 8.37E-09 |

| 1432466_a_at | Apoe | Apolipoprotein E | 3.9 | 8.07E-08 |

| 1434273_at | A830073O21 | RIKEN cDNA A830073O21 gene | 3.8 | 9.64E-10 |

| 1427049_s_at | Smo | Smoothened homolog (Drosophila) | −3.5 | 1.51E-10 |

| 1455626_at | Hoxa9 | Homeobox A9 | −3.5 | 5.32E-07 |

| 1424338_at | Slc6a13 | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter) | −3.5 | 3.07E-06 |

| 1426657_s_at | Phgdh | 3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | −3.6 | 3.10E-07 |

| 1417219_s_at | Tmsb10 | Thymosin, beta 10 | −3.6 | 8.47E-07 |

| 1433428_x_at | Tgm2 | Transglutaminase 2, C polypeptide | −3.8 | 2.81E-06 |

| 1426908_at | Galnt7 | Polypeptide GalNac transferase 7 | −3.9 | 2.08E-07 |

| 1416330_at | Cd81 | CD 81 antigen | −3.9 | 1.90E-06 |

| 1428230_at | Prkcn | Protein kinase C, nu | −4.0 | 1.47E-07 |

| 1418480_at | Cxcl7 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 7 | −4.0 | 7.20E-08 |

| 1417777_at | Ltb4dh | Leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase | −4.0 | 4.25E-09 |

| 1416368_at | Gsta4 | Glutathione S-transferase, alpha 4 | −4.0 | 8.08E-09 |

| 1436759_x_at | Cnn3 | Calponin 3, acidic | −4.0 | 1.12E-04 |

| 1460121_at | 9630010G10 | RIKEN cDNA 9630010G10 gene | −4.1 | 1.26E-07 |

| 1429881_at | Arhgap15 | Rho GTPase activating protein 15 | −4.1 | 3.58E-09 |

| 1435343_at | Dock10 | Dedicator of cytokinesis 10 | −4.3 | 4.63E-07 |

| 1433575_at | LOC672274 | Similar to transcription factor SOX-4 | −4.3 | 7.89E-07 |

| 1419573_a_at | Lgals1 | Lectin, galactose binding, soluble 1 | −4.3 | 3.88E-09 |

| 1450700_at | Cdc42ep3 | CDC42 effector protein (Rho GTPase binding) 3 | −4.4 | 3.53E-09 |

| 1425458_a_at | Grb10 | Growth factor receptor-bound protein 10 | −4.6 | 8.42E-10 |

Log2 ratio of the signal intensity between Lin− c-Kit+ E/F; Mx1-Cre cells (n = 4) and control Lin− c-Kit+ cells (n = 3).

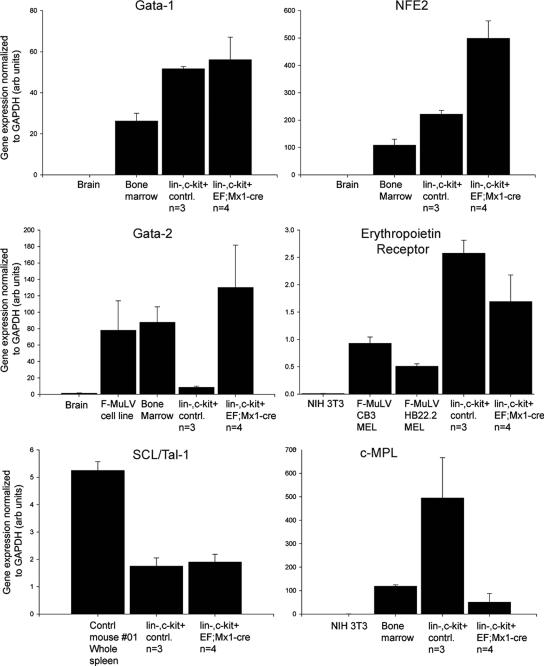

We used quantitative RT-PCR to validate a number of gene expression changes identified by the gene expression array analysis. As shown in Fig. 9 (see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), every gene we examined by quantitative RT-PCR was regulated as indicated by the expression array data set. The myeloid/erythroid marker Gata-1 is highly expressed in malignant cells found in spleens and livers of diseased mice. Expression of the myeloid/erythroid transcription factor Gata-2 was also highly up-regulated in spleens of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Lin− c-Kit+ spleen cells from E/F; Mx1-cre mice expressed the erythropoietin receptor to levels higher than expressed in Friend leukemia cell lines (Fig. 9). Erythropoietin receptor expression has been detected in precursors of erythroid and megakaryocytes lineages but is absent in other myeloid and lymphoid precursors (2) and is not expressed in hematopoietic stem cells. The transcription factor SCL/Tal-1, also expressed in erythroid/myeloid precursors, was present but not elevated in leukemic cells of diseased E/F; Mx1-cre mice (Fig. 9). Lin− c-Kit+ cells also express c-Mpl, the thrombopoietin receptor, but at a low level. These data strongly indicate that the leukemic cells in E/F; Mx1-cre mice are of a myeloid/erythroid nature.

FIG. 9.

Quantitative PCR validation of myeloid/erythroid markers in Lin− c-Kit+ cells from E/F; Mx1-cre mice. SYBR Green quantative PCR was used to quantitate the relative levels of Gata-1, Gata-2, NF-E2, erythropoietin receptor, Scl/Tal-1, and the thrombopoietin receptor c-Mpl in Lin− c-Kit+ cells from control or E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Reverse-transcribed RNAs from whole wild-type spleen, bone marrow, brain, or cultured 3T3 cells were used as control samples. Averages ± standard deviations are shown.

DISCUSSION

Despite the aggressive clinical behavior of Ewing tumors, EWS/FLI-1 or other EWS/ETS fusion proteins lack strong transforming activities in vitro. EWS/ETS fusions consistently arise in Ewing tumors, but the role of these proteins in oncogenesis remains poorly understood. The E/F; Mx1-cre mouse is the first reported model in which EWS/FLI-1 expression has been induced in vivo and provides clear evidence for strong oncogenic activity of EWS/FLI-1. In comparison to other oncoproteins expressed in mice, EWS/FLI-1 also shows very strong oncogenic activity. Mice carrying a floxed K-ras allele and Mx1-cre transgene succumb to myeloproliferative disease with a latency of 35 days after pIpC treatment (14). Activation of AML-ETO in mice carrying a floxed AML-ETO KI allele and the Mx1-cre transgene develop leukemia with low incidence after 1 year of life following pIpC treatment (28). Ews/ERG; Rag1-cre mice develop T-cell lymphoma after 150 days (15). F-MuLV induces erythroleukemia in mice with a latency of 1 to 3 months (42). In comparison, activation of EWS/FLI-1 led to a rapid expansion of leukemic cells that were lineage-negative and c-Kit, CD43, CD71, Gata-2, Gata-1, and erythropoietin receptor positive, causing severe hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, anemia, and >80% mortality within the first 25 days of life.

The histopathological and molecular features of disease arising in E/F; Mx1-cre mice were similar whether mice were treated with pIpC or not, but they developed with very different latencies. In both cases, mice presented with organomegaly, anemia, lethargy, and ultimately death. Spleen, liver, and bone marrow showed infiltration of primitive cells that stained for Gata-1 reactivity and were c-Kit, CD43, and CD71 positive. We detected a high level of recombination of the Rosa E/F KI allele and induction of EWS/FLI-1 mRNA in spleens of diseased non-pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice. Development of pathology in the absence of pIpC treatment has been previously reported in studies using Mx1-cre mice (14, 27, 41, 47). Induction of Cre recombinase in mice carrying the Mx1-cre transgene is dependent on interferon production, consistent with some level of interferon production in mice housed under standard conditions.

Although FLI-1 has a much weaker transactivating activity than EWS/FLI-1, activation of Fli-1 in erythroleukemia induced by F-MuLV is a critical initial step in the multistage development of this leukemia (29). Leukemia induced by EWS/FLI-1 resembles F-MuLV-induced mouse erythroleukemia, but it is clearly distinguished by its rapid onset. The disease is readily transplantable to naïve recipients (latency to death, 1 to 4 months), and the gene expression profiles of transplanted disease are extremely similar to the primary disease state, suggesting that minimal additional changes are required for the EWS/FLI-1-induced primary disease to be propagated through transplantation. Transgenic mice made to overexpress FLI-1 from the ubiquitous H-2KK (major histocompatibility complex antigen class I) promoter do not develop leukemia. Instead, these mice develop B-cell hyperplasia that leads to immune complex glomerulonephritis (80). The phenotype of FLI-1 transgenic mice suggests that other factors, in addition to FLI-1 activation, are required for F-MuLV-induced leukomegenesis. Alternatively, it is possible that the correct subpopulation of hematopoietic cells did not express the FLI-1 transgene in this study. From Western blotting analysis, expression of EWS/FLI-1 appears to be low, much lower than EWS/FLI-1 in a representative Ewing tumor cell line or than endogenous FLI-1 in F-MuLV cell lines or control spleens. The strong transactivation domain from EWS, as well as enhanced or novel interactions with other transcription factors that are present in the susceptible cells, may allow EWS/FLI-1 to drive oncogenesis at the very low protein levels observed in E/F; Mx1-cre mice. We previously transduced murine hematopoietic stem cells in whole bone marrow with an EWS/FLI-1-expressing retrovirus. We obtained a low yield of transduced cells, and these cells did not proliferate in recipient mice in contrast to vector transduced cells (E. C. Torchia and S. Baker, unpublished observations). In these experiments, high-level expression of EWS/FLI-1 driven by the retroviral long terminal repeat (71) may have been toxic to hematopoietic cells. Expression of EWS/FLI-1 by strong promoters in primary cultured fibroblasts was toxic unless the tumor suppressors Arf or p53 were deleted, thus allowing stable EWS/FLI-1 expression without substantial cell death (17). The strongly oncogenic activity of EWS/FLI-1 observed in our study when expressed from the relatively weak Rosa26 promoter suggests that the levels of EWS/ETS proteins may be critical for their function. Similar observations have been made with other oncoproteins. The rhabdomyosarcoma fusion protein PAX3-FKHR transformed cultured myoblasts at low protein levels but induced growth arrest at higher levels (76). Expression of oncogenic Ras at physiological levels resulted in immortalization of primary murine embryonic fibroblasts, while high levels of Ras caused senescence (26, 72).

EWS/FLI-1 is believed to function, at least in part, through aberrant transcription regulation. Expression profiling of Lin− c-Kit+ cells from E/F; Mx1-cre mice did not reveal a single pathway or class of genes regulated by EWS/FLI-1 that may be critical for the transformation of normal hematopoietic cells. From the exploration of gene networks based on the Ingenuity Knowledge Base, the highest ranking function and disease gene networks were associated with oncogenesis, cellular death, cell cycle progression, and proliferation, supporting the notion that interaction of various factors with the activation of EWS/FLI-1 may be important for the development of leukemia in E/F; Mx1-cre mice. However, we did not observe transcriptional upregulation of previously reported target genes of EWS/FLI-1 (1, 18, 19, 58, 69, 74), with the exception of ID2 (24, 51). There was not significant overlap between expression profiles of EWS/FLI-1-induced leukemic cells with expression array data from published studies of Ewing tumors or fibroblasts expressing EWS/FLI-1 (7, 43, 65), even when leukemia-specific genes were identified and compared to presumptive EWS/FLI-1 targets in the other systems. The different cell of origin of these tumor types, with the leukemias arising from hematopoietic cells and sarcoma presumably arising from mesenchymal cells, is likely to be the basis for the low correspondence in expression data. Specificity of promoter binding by ETS transcription factors is determined to a large extent by the complement of cooperating transcription factors that act synergistically with ETS proteins at particular promoters (33). Thus, the presence of cell-type-specific transcription targets for EWS/FLI-1 may obscure the facile identification of similarities between leukemia and sarcoma arising from EWS/FLI-1-mediated transformation. These differences are consistent with studies showing that TLS/ERG can transform both NIH 3T3 and L-G cells, but by distinct pathways, as revealed by distinct patterns of gene expression in these different types of cells (81). In addition, Lessnick and coworkers showed that NIH 3T3 cells expressing EWS/ETS fusion proteins form tumors in mice that resemble human Ewing sarcomas histologically but do not recapitulate the expression profiles of the human tumors (12), supporting the hypothesis that the specific cell context may be critical to generating highly similar gene expression profiles.

c-Myc has been shown to be a target of EWS/FLI-1 (24), and deregulation of c-Myc is a feature of many tumors, including Ewing sarcoma (6, 51). We observed a dramatic upregulation of c-Myc protein in lysates from the whole spleen of E/F; Mx1-cre mice as early as 4 days after induction of Cre activity, although only a small population of cells within the spleen contain Cre-activated cells at this time point. However, the gene expression comparison of Lin− c-Kit+ spleen cells from control and E/F; Mx1-cre mice did not show a significant difference in c-Myc expression. This suggests that EWS/FLI-1 may induce c-Myc expression to similar levels as those found in normal progenitor cells, and this induction may be an early event driving the disease process. Alternatively, the increased c-Myc levels detected at the early stage of the disease may reflect a part of the normal expression profile found in the target cell population susceptible to malignant transformation by EWS/FLI-1.

Leukemic cells in E/F; Mx1-cre mice expressed c-Kit and Gata-1. It is not clear whether this expression pattern was functionally relevant in the development of leukemia or simply marked the population of cells susceptible to transformation by EWS/FLI-1. Both c-Kit and Gata-1 play important roles in normal and pathological hematopoiesis. Gata-1 interacts with various hematopoietic factors, such as FOG-1, Gfi-1, and TAL-1, to repress or activate target genes involved in maturation of erythroid and megakaryocyte precursors (61, 68, 75). Gata-1 expression is essential for the survival of erythroid precursors through the induction of antiapoptotic signals (25). Deregulation of Gata-1 function has also been implicated in human hematopathologies, including myeloid and erythroleukemias (16, 21, 36, 63). Similarly, the c-Kit receptor is expressed on hematopoietic stem cells and various myeloid and erythroid progenitors (37) and is frequently associated with human cancers (48). The c-Kit receptor plays a vital role in erythroid cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation (49). Thus, it is possible that Gata-1 and c-Kit may participate in EWS/FLI-1-induced leukemogenesis.

As shown by detection of Cre activity in Mx1-Cre; Rosa26R or E/F; Mx1-Cre; Rosa26R mice, activation of EWS/FLI-1 occurred throughout various tissue types of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic origin. The Rosa locus is ubiquitously expressed, including in all hematopoietic cells (5, 79). We showed significant Cre-mediated activation of EWS/FLI-1 in hematopoeitic stem cells and lymphoid and myeloid progenitors and at lower levels in cells that give rise to mesenchymal progenitors ex vivo. The rapid development of leukemia in E/F; Mx1-cre mice indicated that myeloid/erythroid cells were preferentially sensitive to the oncogenic effects of EWS/FLI-1. EWS/FLI-1 may initiate a sarcoma program in MPC, as recent papers have suggested (13, 60, 70), or additional mutations may be required to observed sarcoma in mice when EWS/FLI-1 is activated in mesenchymal progenitors. The early morbidity and mortality caused by rapid and severe leukemia in pIpC-treated E/F; Mx1-cre mice may preclude the detection of sarcoma or other pathologies in these mice. Interestingly, we observed embryonic lethality when E/F mice were crossed with Dermo1-cre or Col1α2-cre mice, both of which express Cre activity in mesenchymal tissues during development (22, 78; Torchia and Baker, unpublished). Development of tumors resembling Ewing tumors will likely require the use of lineage-specific expression and inducible Cre molecules (e.g., Cre-ER fusions) that will bypass developmental lethality as well as the aggressive and highly penetrant leukemia phenotype observed in this study.

Although EWS/FLI-1 fusions have not been reported in hematopoietic disease, the related TLS/ERG fusion has been found in acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia as well as in Ewing tumors (30, 32, 55, 64). Recently, a Cre-inducible Ews/ERG knock-in mouse was reported which, when crossed to a RAG1-cre mouse, gave rise to T-cell lymphomas with an onset of 5 months (15). In this model, Ews/ERG was also expressed in B cells but did not induce B-cell neoplasia, suggesting that like EWS/FLI-1, the effects of Ews/ERG are dependent on cellular context. Given the rapid onset of aggressive disease initiated by EWS/FLI-1 expression, it is surprising that EWS/FLI-1 is not frequently identified in human hematopoietic disease. This may reflect intrinsic differences between mice and humans. It is well established that mice are susceptible to a different spectrum of sporadic tumors than humans, and cultured mouse cells are more readily transformed by oncogenic stimuli than human cells (59). Unlike humans, mice have ongoing extramedullary hematopoiesis in the red pulp of the spleen. Interestingly, expansion of myeloid/erythroid cells in E/F; Mx1-cre mice appeared to originate from the liver or spleen, and not the bone marrow, a more common site for development of leukemias in humans. Alternatively, the frequency of chromosomal translocations required to generate EWS/ETS fusions may occur at much lower frequency in human hematopoietic cells compared to mesenchymal tissues. However, our model reveals that EWS/FLI-1 strongly disrupts normal regulation of the myeloid compartment and as such may provide a fruitful avenue for further studies of normal myeloid development and leukemogenesis.

The rapid and severe disease resulting from EWS/FLI-1 activation is the first example of in vivo oncogenic activity of this fusion protein. EWS/FLI-1-induced leukemia provides a model system to study the contribution of the EWS/ETS family of fusion proteins to tumorigenesis and may have important implications for human hematopoietic disorders, as dysregulation of ETS family proteins has been observed in murine and human leukemia (8, 9, 54). E/F; Mx1-cre mice may also give important insights into what cellular contexts are important to render cells susceptible to the oncogenic effects of TET/ETS translocation proteins. Further, E/F mice are a novel experimental tool that can be combined with different Cre mice for in vivo and in vitro analysis of EWS/FLI-1 function in diverse cell types and developmental contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Philippe Soriano (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA) for constructs to generate the ROSA26/EWS/FLI-1 targeting vector and Yaacov Ben David (University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada) for F-MuLV cell lines. We thank Paul Ney (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital) for MEL cells and helpful discussions and Bob Lorsbach, James Downing, and Charles Mullighan for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant CA92117 to S.J.B. and by the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 September 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abaan, O. D., A. Levenson, O. Khan, P. A. Furth, A. Uren, and J. A. Toretsky. 2005. PTPL1 is a direct transcriptional target of EWS-FLI1 and modulates Ewing's sarcoma tumorigenesis. Oncogene 24:2715-2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akashi, K., D. Traver, T. Miyamoto, and I. L. Weissman. 2000. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature 404:193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, M. K., G. Hernandez-Hoyos, R. A. Diamond, and E. V. Rothenberg. 1999. Precise developmental regulation of Ets family transcription factors during specification and commitment to the T cell lineage. Development 126:3131-3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arvand, A., and C. T. Denny. 2001. Biology of EWS/ETS fusions in Ewing's family tumors. Oncogene 20:5747-5754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asari, S., S. Okada, Y. Ohkubo, A. Sakamoto, M. Arima, M. Hatano, Y. Kuroda, and T. Tokuhisa. 2004. Beta-galactosidase of ROSA26 mice is a useful marker for detecting the definitive erythropoiesis after stem cell transplantation. Transplantation 78:516-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]