Abstract

Mast cells and basophils are known to be a critical interleukin 4 (IL-4) source for establishing Th2 protective responses to parasitic infections. Chromatin structure and histone modification patterns in the Il13/Il4 locus of mast cells were similar to those of IL-4-producing type 2 helper T cells. However, using a transgenic approach, we found that Il4 gene expression was distinctly regulated by individual cis regulatory elements in cell types of different lineages. The distal 3′ element contained conserved noncoding sequence 2 (CNS-2), which was a common enhancer for memory phenotype T cells, NKT cells, mast cells, and basophils. Targeted deletion of CNS-2 compromised production of IL-4 and several Th2 cytokines in connective-tissue-type and immature-type mast cells but not in basophils. Interestingly, the proximal 3′ element containing DNase I-hypersensitive site 4 (HS4), which controls Il4 gene silencing in T-lineage cells, exhibited selective enhancer activity in basophils. These results indicate that CNS-2 is an essential enhancer for Il4 gene transcription in mast cell but not in basophils. The transcription of the Il4 gene in mast cells and basophils is independently regulated by CNS-2 and HS4 elements that may be critical for lineage-specific Il4 gene regulation in these cell types.

Interleukin 4 (IL-4) and IL-13 are canonical Th2 cytokines responsible for immunity to extracellular pathogens and helminth parasites and contribute to the pathology of allergy, asthma, and other atopic diseases. Several cell types have been reported to secrete IL-4 and IL-13, including CD4 T cells, Th2 cells, NKT cells, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils (1, 6, 29, 43, 48). The initial production of IL-4 appears to be key to determining the subsequent course of immune responses. Th2 cells are regarded as the main source of IL-4 and IL-13 during the effector phase of Th2 responses. However, CD44hi memory phenotype (MP) CD4 T cells appear to be critical for the initial generation of IL-4 to regulate the development of Th2 cells from naive T cells, since MP CD4 cells have the potential to produce large amounts of IL-4 and IL-13 following antigenic activation (42). Considerable research emphasis has been placed on understanding the molecular basis of Il4 gene regulation in CD4 T cells. However, myeloid-lineage cells, including mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils, are candidate IL-4 sources in innate immune responses to parasite worms and in allergic responses (8, 16, 19, 26). Mast cells and basophils are distinguished by expression of the high-affinity immunoglobulin E receptor (FcɛRI), which is absent from murine eosinophils (7, 45). Cross-linking of FcɛRI-bound immunoglobulin E with allergens rapidly induces a broad spectrum of bioactive mediators, such as histamine, arachidonic acid metabolites, proteases, chemokines, and cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13 (10, 18). Moreover, various other stimuli induce IL-4 production by mast cells and basophils. Calcium ionophores and bacterial pathogen-associated molecular patterns are inducers common to both cell types, while IL-3 is a unique stimulus for basophils (11, 18). Therefore, transcriptional regulatory mechanisms of the Il4 gene in myeloid-lineage cells should be distinguishable from those in CD4 T cells, but our understanding of Il4 gene regulation in innate myeloid-lineage immune cells is very limited.

Mast cells are derivatives of bone marrow-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells and migrate into all vascularized tissues, where they complete their maturation (9, 10). Connective-tissue-type mast cells normally reside close to epithelia, blood vessels, nerves, airways, the gastrointestinal tract, and mucus-producing glands but do not recirculate into other vascularized tissue (46). This type of mast cell is morphologically distinguishable from immature bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) (33, 34). Basophils share several features with mast cells, but these two lineages are distinguishable based on mediator contents, such as serotonin, heparin, elastase, arachidonic acid metabolites (PGE2 and PGD2), and platelet-activating factor. Serotonin, prostaglandin, and platelet-activating factor are secreted only from mast cells (10). Mast cells are typically long lived, whereas basophils complete their maturation in the bone marrow and normally circulate in blood with a short life span (10). IL-4 and IL-13 are cytokines produced by both lineages (44), but there is no clear evidence that they share common transcriptional activation mechanisms for production of these cytokines.

The importance of the myeloid lineage as an innate source of IL-4 is also suggested by a series of studies using bicistronic IL-4 reporter (4get) transgenic mice produced by the targeted addition of an internal ribosome entry site-green fluorescent protein (GFP) to the 3′ untranslated region of the Il4 gene (30). In vivo studies with 4get mice have demonstrated that mast cells and basophils constitutively express IL-4 and IL-13 transcripts (12), thereby allowing immediate production of these cytokines during an innate immune response to parasite infections (26-28). However, a key question unresolved in the studies with 4get mice concerns Il4 gene regulation and whether cells of different lineages use overlapping mechanisms to transcribe the same gene. A combination of DNase I-hypersensitive assays, histone modification analysis, and cross-species comparative sequence analysis have led to the identification of a number of cis regulatory elements regulating Th2-specific IL-4 expression. cis regulatory elements have been defined in the region between Il13 and Il4 (CNS-1), within the Il4 promoter (HS1), second intron (HS2, corresponding to the intronic enhancer [IE]), and proximal 3′ (HS4) and distal 3′ (HS5 and 5a) elements. HS5 is a highly conserved Th2-specific HS site and corresponds to conserved noncoding sequence 2 (CNS-2), while HS5a is an inducible HS site. Targeted deletion of HS5a and CNS-2 abrogates Il4 gene transcription in BMMCs, suggesting that binding of NFAT-1 to HS5a is implicated in IL-4 and IL-13 expression (2). However, deletion of CNS-1 is not harmful for IL-4 and IL-13 production in BMMCs (31). Previous studies also suggest that mast cells utilize a different set of transcriptional factors from Th2 cells. BMMCs appear to utilize GATA-1/2 instead of GATA-3 (39), and coordination of GATA-1/2 with AP-1 regulates IL-13 promoter activity in mast cells (25). Recently Ikaros was reported to negatively regulate GATA-mediated IL-4 production by BMMCs (13). However, the mechanisms that regulate Il4 gene expression in basophils are virtually unknown, although their importance in Th2 and allergic responses is clear.

We have developed a series of GFP reporter transgenic lines that contain different cis-acting elements in order to examine the role of each CNS in cells of different lineages. We have previously shown that CNS-2 is active in MP CD4 T cells and NKT cells but not resting Th2 cells and that IE and HS4 elements showed no activity in T-lineage cells (42). In the present study, we demonstrate that CNS-2 is a common regulatory element for MP CD4 cells, NKT, mast cells, and basophils but is dispensable for IL-4 production in basophils. Our studies suggest that the HS4 element instead is a specific enhancer for IL-4 transcription in basophils. These results demonstrate that mast cells and basophils use distinguishable mechanisms to regulate Il4 gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of GFP reporter Tg mice and CNS-2-deficient mice.

The basic pIL-4 construct was made by insertion of the 5′ enhancer (5′E) (−863 to −5448; starting codon is defined as sequence number 0) (22) and the IL-4 promoter from position −64 to −827 downstream of a GFP cDNA from the IL-2P/GFP/hCD2LCR reporter construct (37). IE (+311 to +3534), HS4 (+6231 to +10678), and 5a/CNS-2 (+11308 to +15635) fragments were isolated from a mouse YAC clone (catalog no. 95022; Research Genetics) and inserted into the basic pIL-4 construct. The deletion mutant constructs pBS-Δ5a/CNS-2 and pBS-Δ5a were generated by deleting the first 1,657 bp and 244 bp from the distal 3′ fragment. Each transgenic (Tg) line was obtained more than three times and was backcrossed onto the BALB/c strain for more than six generations. The transgene copy number was analyzed by Southern blotting with an IL-4 promoter probe and was calculated by comparing the band intensity with that of pBS-pIL-4 plasmid DNA.

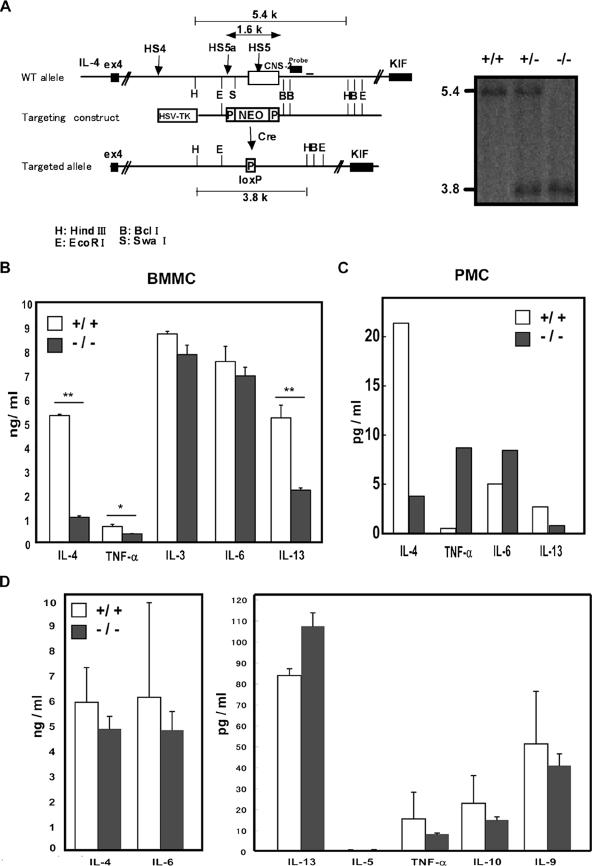

The CNS-2 targeting vector was constructed in a PGK-neo cassette flanked by LoxP sites and a herpes simplex virus tk gene, with short-arm (+10359 to +11304) and long-arm (+12965 to +19025) sequences obtained from the Il4 locus. Deletion on the 5.4-kb wild-type allele resulted in a new 3.8-kbp HindIII/HindIII fragment, which was detected by Southern blotting (see Fig. 6A). To delete the PGK-neo gene, chimeric mice were crossed with CAG-Cre Tg mice (36). A mouse with a deletion of CNS-2 was backcrossed onto the B6 line for at least four generations. All mice used in this study were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Animal care was conducted in accordance with guidelines of the RIKEN Yokohama Institute.

FIG. 6.

(A) Generation of CNS-2-deficient mice and schematic representations of wild-type (WT) and mutant alleles in Il4 loci and target construct. The CNS-2 enhancer element is represented by an open box. The neomycin-resistant gene (NEO), the gene coding for the thymidine kinase driven by a herpes simplex virus promoter (HSV-TK), and loxP (P) are indicated by white boxes. HindIII-digested genomic DNA fragments were detected by using a probe. Restriction sites: H, HindIII; B, BclI; E, EcoRI; S, SwaI. Representative Southern blot analysis with HindIII-digested DNA. The position of the probe is shown on the WT allele of the left panel. (B) Cytokine production pattern in BMMC cells. The IL-3-induced BMMC cells from normal littermate (+/+) or CNS-2-deficient (−/−) mice were stimulated with PMA-Iono for 24 h, and cytokine production was assessed. Data are means and standard deviations for three experiments. **, P < 0.01. *, P < 0.05. (C) Cytokine production pattern in PMC cells. c-Kit+ peritoneal cells from normal littermate (+/+) or CNS-2-deficient (−/−) mice were stimulated with PMA-Iono for 24 h, and cytokine production was assessed as described for panel B. (D) Basophils were enriched as DX-5+ B220− cells from BM of normal littermate (+/+) or CNS-2-deficient (−/−) mice, and cells were stimulated with IL-3 for 24 h.

Cytokine measurement and antibodies.

Cytokine production was measured by using the 23-Plex panel of the Bioplex cytokine assay system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay system (BD, San Diego, CA). For analysis of the cell surface phenotype, anti-CD4 (L3T4), -NK1.1 (PK136), -c-Kit (2B8), -FcɛRI (MAR-1), -B220 (RA3-6B2), and -CD49b (DX-5) antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen.

Single-cell analysis of GFP expression and cell preparation.

The preparation of Th2 cells was previously described (2). BMMCs were derived from bone marrow (BM) cells cultured for 4 weeks in the presence of IL-3 (Pepro Tech, Inc., London, United Kingdom) and/or stem cell factor (SCF) (50 ng/ml; WAKO, Osaka, Japan). For enrichment of basophils from spleen and BM, positive sorting with DX-5 beads (Milteny Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) was carried out after negative sorting with biotin-conjugated anti-CD3 (145-2C11), -B220, and -CD19 (MB19-1) antibodies (BD) and streptavidin beads (BD).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and restriction enzyme accessibility (REA) assay.

DNA recovered from an aliquot of sheared chromatin was used as the “input” sample. The chromatin was precleared with protein A and G agarose (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and immunoprecipitated with anti-acetylated H3 antibody (#06-599; Upstate, Charlottesville, VA) or anti-trimethylated K4 antibody (ab8580; Abcam Cambridge, United Kingdom). Input DNA and immunoprecipitated DNA were quantified by Pico Green fluorescence (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Equivalent masses of sample and input sample were compared using real-time PCR. Data are presented as the ratio of sample versus input values.

For the REA assay, a nuclear fraction of BMMC was resuspended in buffer F (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM 2-ME) (38). The nuclear fraction was treated with restriction endnucleases (100 U; Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), and the sample was precipitated with ethanol. After resuspension in Tris-EDTA buffer, the digested DNA (5 μg) was analyzed by Southern blot analysis with appropriate digoxigenin-labeled probes.

RESULTS

Epigenic regulation of the Il13/Il4 locus in mast cells.

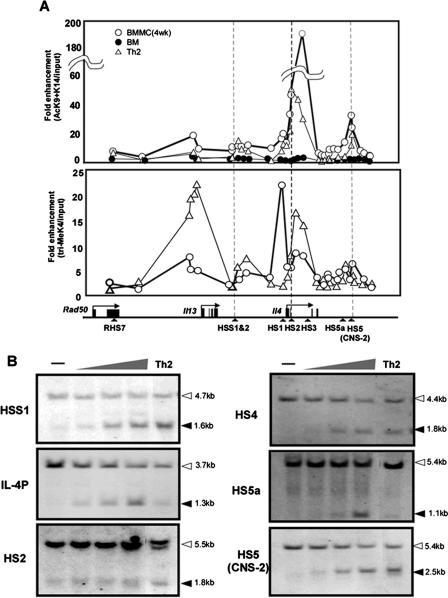

Acquisition of IL-4 production ability by CD4 T cells is controlled epigenetically during Th2 differentiation (3, 41). To determine whether IL-4 production by myeloid cells is under similar epigenetic control, BMMC were prepared by long-term culture with IL-3 and analyzed by ChIP analysis to assess modification of histone H3 across the il13/il4 locus. For histone H3, posttranscriptional modification for transcriptional accessibility can be defined by lysine 9/14 acetylation (AcK9/14) and lysine 4 trimethylation (3MeK4). Therefore, our analysis focused on these transcriptionally permissive modifications in mast cells. BMMCs showed high levels of AcK9/14 in a region extending from the IL-13 promoter to downstream of the HS2 and HS5 sites, and the overall pattern of AcK9/14 increase was similar to that seen in Th2 cells (Fig. 1A). The pattern of 3MeK4 increase also resembled that of Th2 cells except in the region around the IL-4 promoter, with a previous study reporting no permissive modification in the IL-4 promoter of unstimulated Th2 cells (5).

FIG. 1.

(A) H3 modification pattern. Acetylation and methylation in mast cells. ChIP analysis for AcH3 K9/14 and 3Me H3K4 was performed on developmental Th2 cells(▵), BMMCs (○), and BM cells (•) from BALB/c mice. Th2 cells were prepared using plate-bound anti-T-cell-receptor and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies in the presence of IL-4 and anti-IL-12. BMMCs were derived from BM cells cultured for 4 weeks in the presence of IL-3. The bottom panel shows the structure of the Il13/Il4 locus and hypersensitive site (HS). The data are representative of three independent experiments. (B) REA pattern in BMMC. Nuclei were prepared from BMMC and Th2 cells (5 × 106 cells) and digested with three distinct concentrations, 1, 10, and 100 U of XhoI for HSS1, PstI for IL-4P and IE, BtsI for HS4, SwaI for HS5a, or HgaI for HS5. Gray triangle (top) indicates the gradation of restriction enzymes. For Th2 cells, representative data for digestion with 10 U restriction enzyme are shown. DNA was purified and digested with either EcoRI for CNS-1, HindIII for IL-4P, HS2, HS5a, and HS5, or PstI for HS4 and analyzed by Southern blotting using appropriate probes. The open arrows indicate EcoRI, HindIII, and PstI sites, and the filled arrows indicate XhoI, PstI, BtsI and HgaI sites.

We next investigated the modification of chromatin conformation on HS sites in BMMCs by a REA assay. HSS1 and -2, IL-4 promoter (IL-4P), HS2, and HS5 (CNS-2) are Th2-specific constitutive HS sites (3, 41), and HS-5a is a Th2-specific, activation-dependent site (2). HS-4 is a constitutive HS site commonly observed in both Th1 and Th2 cells (3). Chromatin remodeling was clearly found at all HS sites, and overall, the pattern in BMMC was quite similar to that seen in Th2 cells except for the HS5a site, which was constitutively accessible (Fig. 1B). These results indicated that modification of chromatin conformation across the Il13/Il4 locus in mast cells closely resembles that in Th2 cells.

Regulation of IL-4 enhancer in basophils and mast cells.

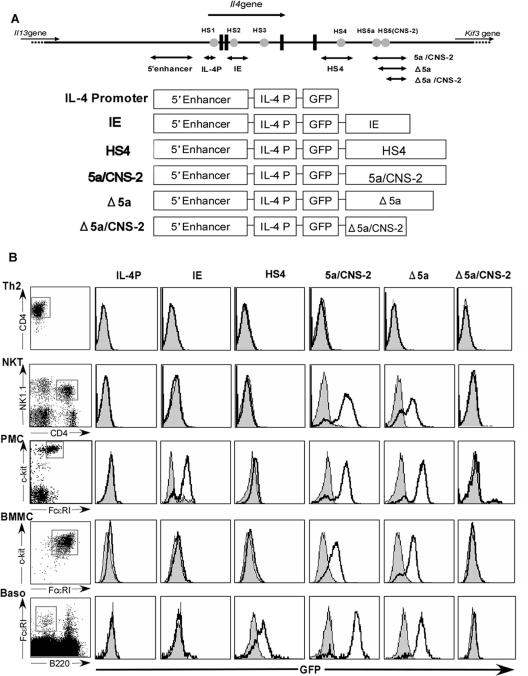

We recently established a series of Tg lines to define the activity of regions of the Il13/Il4 locus that are highly conserved among vertebrate species (Fig. 2). In T-lineage, NKT and MP CD4 T cells from HS5a/CNS-2 GFP Tg mice (HS5a/CNS-2 Tg), GFP was expressed only in unstimulated cells, and Th2-specific GFP expression was found only when the constitutively GFP-expressing cells were restimulated (42). We further investigated the function of these enhancer elements in mast cells and basophils. BMMCs were prepared by IL-3 culture (>95% c-Kit+ FcɛR+), and peritoneal mast cells (PMC) were sorted from peritoneal cells as c-kit+ FcɛR+ cells. Basophils were purified from spleen and bone marrow as B220− c-Kit− DX-5+ FcɛR+ cells by sorting. NKT cells were sorted as NK1.1+ cells from CD4 T cells in liver tissue from C57BL/6 background mice.

FIG. 2.

(A) Diagram of the Il4 locus and constructs for Tg mice. Gray circles indicate HS sites, and bidirectional arrows indicate fragments that were used for Tg reporter constructs. All GFP reporter constructs used in this study are shown. (B) GFP expression in Th2 cells, NKT cells, PMCs, BMMCs, and basophils. Unstimulated Th2 cells were prepared from splenic CD4 T cells of each Tg line, NKT cells were freshly isolated from liver cells of each Tg line as NK1.1+ CD4+ cells, and PMCs and basophils were freshly isolated from peritoneal and spleen cells as FceRI+ c-Kit+ cells and FceRI+ B220− cells, respectively. BMMCs were derived from BM cells cultured for 4 weeks in the presence of IL-3. The data are representative of three experiments.

The IL-4P Tg cells consistently showed no GFP expression in any of the lineages that we examined in this study. In contrast, the HS5a/CNS-2 enhancer was active in NKT cells, BMMC, PMC, and basophils but not in resting Th2 cells (Fig. 2). This result is consistent with our previous finding that the HS5a/CNS-2 enhancer is inactive in the Th2 cells derived from GFP-nonexpressing cells (42). To narrow down the region driving GFP expression, we further examined two Tg lines in which HS5a or both HS5a and the CNS-2 region were deleted (Δ5a and Δ5a/CNS Tg). The proportions of GFP-expressing cells in Δ5a and HS5a/CNS-2 Tg were comparable, but deletion of the CNS-2 region abolished GFP expression in all cell lineages (Fig. 2), suggesting that CNS-2 not only regulates IL-4 production in NKT and MP CD4 T cells but also has enhancer activity in mast cells and basophils.

The IE was originally characterized as a mast cell-specific enhancer (15). However, in IE Tg cells, GFP expression was found only in PMCs, which are thought to be connective-tissue-type mast cells (Fig. 2). On the other hand, HS4 behaved as a positive regulatory element in basophils (Fig. 2). The HS4 region showed no GFP expression in any T lineage, because this region contains a silencer and the HS4 site, which may regulate Th1-specific silencing (4). These results indicate that IE and HS4 elements play a role as lineage-specific enhancers for connective-tissue-type mast cells and basophils, respectively.

CNS-2 enhancer regulates innate IL-4 production from mast cells.

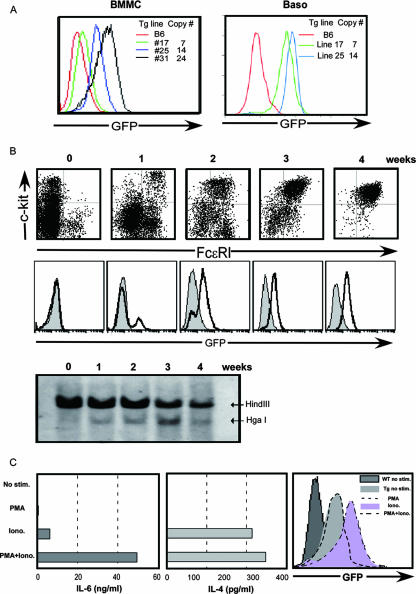

Next, we examined the temporal activity of the CNS-2 enhancer in IL-3-induced mast cells and basophils. All HS5a/CNS-2 Tg and Δ5a Tg lines indicated consistent GFP expression in these two cell types (Fig. 3A). Long-term culture of BM cells with IL-3 gradually induced development of c-Kit+ FcɛRI+ mast cells, and more than 95% of BM cells expressed both c-Kit and FcɛRI by 4 weeks. GFP+ cells also gradually increased in parallel with the increasing of the number of c-Kit+ FcɛRI+ mast cells. REA of IL-3-cultured BM cells indicated that structural chromatin modification in CNS-2 was detectable within 1 week, accompanying the appearance of mast cells in the cultures (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that the appearance of CNS-2 enhancer activity correlates with the differentiation of mast cells.

FIG. 3.

(A) GFP expression of three Δ5a Tg lines. GFP expression was assessed in BMMC and basophils derived from Δ5a Tg lines. The copy number of each line is shown in the column. (B) The appearance of CNS-2 enhancer-mediated GFP expression correlates with the differentiation of mast cells. BM cells from HS5a/CNS-2 Tg mice were cultured with IL-3, and GFP (middle panel) and c-Kit/FcɛR (upper panel) expression was analyzed at 1 to 4 weeks. The bottom panel represents the REA pattern in IL-3-cultured BM cells. Nuclei were prepared from IL-3-cultured BM cells (5 × 106 cells) and digested with HgaI. DNA was purified and digested with HindIII and analyzed by Southern blotting using the probes for HS5. The data are representative of two independent experiments. (C) The CNS-2 enhancer activity correlates with IL-4 production in BMMC. BMMC derived from HS5a/CNS-2 Tg mice were stimulated with either PMA, Iono, or PMA-Iono. Secretion of IL-6 (left) or IL-4 (middle) in culture supernatant of the stimulated BMMC was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The right panel represents GFP expression in BMMC derived from HS5a/CNS-2 Tg mice. The data are representative of three experiments.

IL-4P has been reported to be solely controlled by increases in Ca+ mobilization, since the calcium ionophore, ionomycin (Iono), initiated full activation of IL-4P and IL-4 expression in Th2 cells through the calcineurin-NFAT pathway (20, 21, 24). Therefore, we examined the correlation between activation of CNS-2 enhancer activity and IL-4 production in cells stimulated with either Iono or a combination of PMA and Iono (PMA-Iono). Iono stimulation initiated clear activation of enhancer activity and induction of IL-4 but not IL-6 in BMMCs from HS5a/CNS-2 Tg mice, but a combination of PMA and Iono was required for full induction of IL-6 production (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that CNS-2 enhancer activity may regulate the ability of mast cells to secrete IL-4.

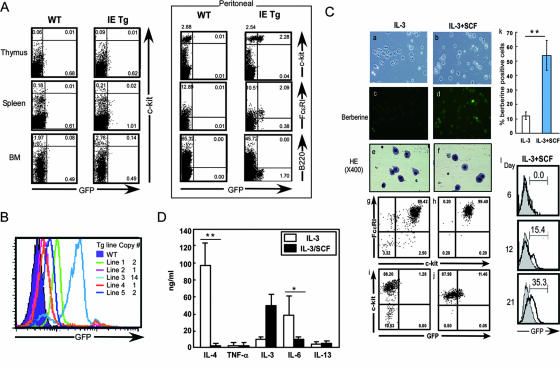

IE is a specific enhancer for peritoneal cell-derived mast cells.

We next examined whether IE was active in particular subsets of mast cells. Thus, the enhancer activity was analyzed in c-Kit+ cells from thymus, spleen, BM, and peritoneal cells of IE Tg mice. The c-Kit+ cells exhibited clear GFP expression in peritoneal cells but not in spleen and BM cells (Fig. 4A). The cell surface phenotype of peritoneal GFP+ cells (c-Kit+ FcɛRI+ B220−) identified them as PMC. All five independent Tg mouse lines showed detectable GFP expression in peritoneal c-Kit+ FcɛRI+ cells, and the expression levels were controlled in a copy number-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). As shown in Fig. 2B, long-term IL-3-cultured BMMC from HS5a/CNS-2 Tg and Δ5a Tg lines expressed GFP, but the IL-3-cultured BMMC from IE Tg mice failed to initiate enhancer activity (Fig. 4C). However, culture with both IL-3 and SCF initiated GFP expression by BMMC and an accompanying increase in connective-tissue-like mast cells characterized by c-Kit and FcɛRI expression and staining with the heparin binding dye berberine sulfate (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the cytokine production pattern in IL-3 BMMC was quite distinct from that in IL-3/SCF BMMC. The immature type of IL-3 BMMC secreted much higher amounts of IL-4 and IL-6 (about 200 to 1,000 times) than did connective-tissue-type mast cells, such as IL-3/SCF BMMC and PMC (Fig. 4D and 6C). These results suggest that the connective-tissue-type mast cells have potential distinct from BMMC in terms of IL-4 production and that the IE behaves as a tissue-specific enhancer in this restricted subset of mast cells.

FIG. 4.

(A) IE enhancer activity in c-Kit+ cells from thymus, spleen, BM, and peritoneal cells. GFP expression was assessed in c-Kit+ cells from thymus, spleen, and BM of wild-type (WT) or IE Tg mice (left panel). The IE-mediated GFP expression was analyzed in c-Kit+, FceRI+, or B220− peritoneal cells (right panel). (B) IE enhancer activity is copy number dependent. GFP expression was assessed in BMMC derived from five independent IE Tg lines. The copy number of each line is shown in the column. (C) IE is a specific enhancer for IL-3/SCF-induced BMMC. BM cells were cultured with IL-3 in the absence (a, c, e, g, and i) or the presence (b, d, f, h, j) of SCF, and cells were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and berberine; visible light (a and b), berberine (c and d), and HE (e and f) visualization is shown. Percentages of berberine-positive cells were assessed in IL-3- or IL-3/SCF-cultured BM cells (k). Data indicate means and standard deviations. **, P < 0.01. GFP expression was assessed in a c-Kit+ FceRI+ population from IL-3-cultured (g and i) or IL-3/SCF-cultured (h and j) BM cells. To assess the appearance of IE enhancer-mediated GFP expression, BM cells from IE Tg mice were cultured with IL-3 in the presence of SCF and GFP expression was assessed at days 6, 12 and 21 (l). (D) The cytokine production pattern in IL-3- or IL-3/SCF-induced BMMC cells. IL-3- or IL-3/SCF-induced BMMC cells were stimulated with PMA+Iono for 24 h, and cytokine production was assessed using the 23-Plex panel of the Bio-Plex assay system. Data indicate means and standard deviations for three experiments. **, P < 0.01. *, P < 0.05.

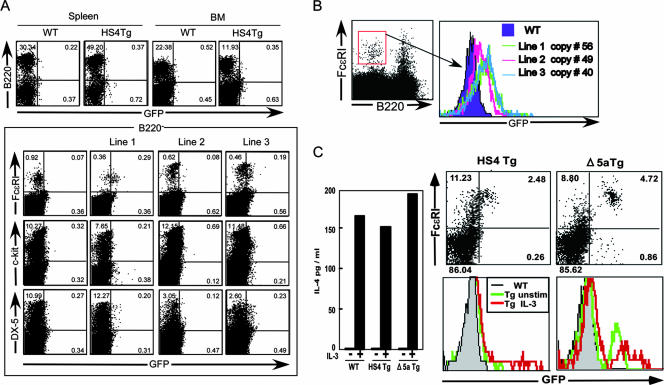

HS4 element is a specific enhancer for basophils.

Basophils are thought to be an innate source of IL-4 in response to IL-3 and FceRI cross-linking (35), and results for 4get mice and 5a/CNS-2 Tg mice demonstrated that basophils acquire constitutive IL-4 transcription (19). The Δ5a Tg cells showed detectable levels of GFP expression, indicating that it is partly regulated by CNS-2 (Fig. 3A). However, B220− c-Kit− DX-5+ FcɛRI+ basophils from spleen and BM cells of HS4 Tg mice also showed constitutive GFP expression (Fig. 5A and B), although its level was quite low compared to that in 5a/CNS-2 Tg and Δ5a Tg cells (Fig. 5C). Basophils secreted IL-4 in response to either IL-3 or Iono, and these stimuli induced activation of HS4 and CNS-2 enhancer activity in BM-derived basophils (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the HS4 element may contribute to basophil-specific expression of il4. Interestingly, HS4 is the regulatory element that controls il4 gene silencing in T-cell lineages; meanwhile, the same region activates the il4 gene in basophils.

FIG. 5.

(A) HS4 enhancer activity in spleen and BM. GFP expression was assessed in B220− cells from spleen and BM of wild-type (WT) or HS4 Tg mice (upper panel). HS4-mediated GFP expression was assessed in FceRI+, DX-5+, or c-Kit− cells from B220− spleen cells of three HS4 Tg lines, lines 1 to 3 (bottom panel). (B) HS4 enhancer activity is copy number independent. GFP expression was assessed in FceRI+ DX-5+ B220− spleen cells isolated from three independent Tg lines, lines 1, 2, and 3. The copy number of each line is shown in the column. (C) The CNS-2 and HS4 enhancer activities correlate with IL-4 production in basophils. DX-5+ B220− cells were isolated from BM of wild-type (WT) mice and HS4 and ΔHS5a Tg mice, and GFP expression (right panel) and IL-4 production (left panel) were assessed with (red line in bottom light histogram) or without (upper right and green line in bottom light histogram) IL-3 stimulation.

Deletion of CNS-2 from il4 locus diminishes IL-4 expression in mast cells but not basophils.

Our results lead to the possibility that distinctive enhancer elements coordinately regulate IL-4 production in mast cells and basophils. CNS-2 may be a common enhancer for all IL-4-producing myeloid lineage cells, not just mast cells and basophils, whereas the IE and HS4 element seem to be lineage-specific enhancers. Thus, we next asked whether CNS-2 is a critical regulatory element for IL-4 production by myeloid lineage cells. To answer this question, we generated CNS-2-deficient mice by targeted deletion of the CNS-2 site from the endogenous Il13/Il4 locus (Fig. 6A).

BMMCs and PMCs were prepared from wild-type littermate and CNS-2-deficient mice, respectively. Cytokine production by BMMCs and PMCs was measured in response to Iono. CNS-2 deficient BMMC showed a marked reduction in IL-4 and IL-13 but not IL-3 and IL-6 production (Fig. 6B). IL-4 and IL-13 production by PMC showed a similar reduction in the CNS-2-deficient mice, although PMC produced about 200 times less IL-4 in comparison with BMMC (Fig. 6C). Based on these data, we conclude that the CNS-2 enhancer regulates IL-4 and IL-13 production in both the connective tissue type and immature type of mast cells.

Next, we prepared enriched basophils from BM of wild-type littermate and CNS-2-deficient mice and measured cytokine production in response to IL-3. Unlike mast cells, basophils from CNS-2 deletion mice showed no significant reduction in IL-4 or other cytokine production (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that the CNS-2 enhancer is essential for IL-4 production by mast cells but not by basophils. Therefore, the CNS-2 enhancer is not a critical basophil enhancer, and it is likely that another enhancer, such as the HS4 element, may regulate il4 gene expression in these cells.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that Il4 gene expression is distinctively regulated by individual cis regulatory element in different cell lineages, such as CD4 T cells, NKT cells, mast cells, and basophils. CNS-2 enhancer activity was common to NKT cells, mast cells, and basophils. However, the results from mutant mice in which the CNS-2 region had been deleted indicate that CNS-2 is essential for IL-4 and IL-13 production in mast cells but not in basophils. On the other hand, the HS4 element was selectively active only in basophils. The IE is active only in particular subsets of mast lineages, such as PMC and IL-3/SCF-derived BMMCs. These results indicate that the IE and HS4 enhancers are cell-type-specific cis-acting elements that may regulate transcription of the Il4 gene in mast cells and basophils, respectively.

Chromatin structure and H3 modification patterns of mast cells in the Il13/Il4 locus almost overlapped those of Th2 cells. Histone modification is thought to be a stable epigenetic marker capable of indexing chromatin function, and 3MeK4 and AcK9/14 of H3 are well-established indicators for the transcriptionally active state of chromatin. Therefore, BMMCs exhibited chromatin accessibility at most of the cis-acting elements within the Il13/Il4 locus, which have been well characterized for Th2 cells. Our results are consistent with the overall pattern of the HS site and histone acetylation profile in embryonic stem cell-derived mast cells and BMMC that have been reported by others (13, 32). Moticelli et al. reported two mast cell-specific differences in HS sites with DNase I compared to those of Th2 cells. The CNS-1 is not accessible in BMMCs, while the first intron region of the Il13 gene contains a mast cell-specific HS site (32). We examined HS sites with restriction enzyme, and all well-characterized HS sites in the Il4 locus were accessible. On the other hand, Gregory et al. found the inconsistent result that the CNS-1 and HS5a sites are heavily acetylated in embryonic stem cell-derived mast cells and BMMC (13). Our data indicate that BMMCs exhibit dynamic transcriptional accessibility in a wide range of the region spanning the Il13 promoter to the CNS-2 region, and this is a common event in both Th2 cells and mast cells. Therefore, the acquisition of accessible chromatin may be a crucial event for the IL-4-producing cells, although it remains unclear whether all cis-acting elements contribute equally to the determination of cell-type-specific gene expression.

Our results using the CNS-2 enhancer deletion mutant mice showed a marked reduction in IL-4 and IL-13 production in mast cell lineages, BMMC and PMC. Our knockout construct harbored a deletion of the last half of HS5a and all of CNS-2 from the genome; therefore, these results are consistent with previous data from HS5a/CNS-2-deficient mice (40). We cannot totally exclude the involvement of HS5a in IL-4 and IL-13 production in mast cell lineages. However, our results for 5a/CNS-2, Δ5a, and Δ5a/CNS-2 Tg lines in Fig. 2B indicated that HS5a may be dispensable for enhancer activity in mast cells, because deletion of HS5a showed a level of enhancer activity comparable to that of the 5a/CNS-2 Tg line while deletion of HS5a and CNS-2 attenuated the enhancer activity. HS5a is a less well conserved HS site that is adjacent to the CNS-2 region (2) and has been characterized as an inducible enhancer for Il4 expression in mast cells through the binding of NFAT, GATA, and Ikaros (13). The Tg approach showed clearly that 5a/CNS-2 or CNS-2 is a constitutive enhancer in mast cells, although activation of calcium signaling was required for induction of full enhancer activity and IL-4 production. These results clearly support the possibility that CNS-2 is a critical enhancer for Il4 expression in mast cells.

In BMMCs, deletion of CNS-1 located between the Il13 and Il4 genes had no effect on IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 production (29). In contrast, deletion of RHS7, an HS site located in the intronic region at the 3′ end of the Rad50 gene, reduced IL-4 and IL-13 production to about half the levels for wild-type mice, but not IL-5 production (23). Another HS site, HS4, is transcriptionally permissive in naive T cells, Th1 and Th2 cells, and mast cells, but its deletion increased IL-4 production, suggesting that HS4 functions as a silencer for Il4 gene expression in BMMC (4). Since CNS-2 and RHS7 are likely to redundantly control positive regulation of the Il4 and Il13 genes, coordination of the RHS7, HS4, and CNS-2 elements may regulate Il4 gene expression in mast cell lineages.

We found that the IE is a cell-type-specific enhancer for PMC and IL-3/SCF-derived BMMC. The IE is contained within HS2 and corresponds precisely to a mast cell-specific cis-acting element that has been characterized by reporter analysis in the CFTL-15 fetal liver-derived mast cell line (17). GATA-1, GATA-2, and PU.1 can bind to this element, and PU.1 is likely to facilitate its cell-specific enhancer activity (14, 47). PMC and IL-3/SCF-derived BMMC morphologically and functionally resemble connective-tissue-type mast cells that are derived from immature IL-3-cultured BMMC. If the CFTL-15 mast cell line is a prototype of mature mast cells, our results support the notion that the IE is a mast cell-specific cis-acting element. However, since this element is not utilized by immature IL-3-cultured BMMC, the IE seems to be a specific cis-acting element to distinguish connective-tissue-type mast cells from immature BMMC.

Virtually nothing is known about the mechanisms that regulate Il4 gene expression in basophils except that IL-4 production can be initiated by cross-linking of FcɛR or IL-3 stimulation (18). Surprisingly, deletion of CNS-2 had no effect on IL-4 and IL-13 production by IL-3-stimulated basophils, although the CNS-2 enhancer behaves like a universal cis regulatory element in our Tg reporter system. This result indicates that the CNS-2 enhancer seems to be active but this activity is not essential for Il4 expression in basophils. The CNS-2 enhancer may play a distinct role between basophils and mast cells This discrepancy in the Tg and knockout approach may conceivably be explained by allelic exclusion in IL-4 regulation, because it is ambiguous that regulatory events would occur similarly at the Tg or endogenous locus. However, IL-4 production was normally found in GFP-expressing cells, indicating that regulation would be independent between the Tg and endogenous Il4 loci.

The HS4 element contains two negative regulatory elements for Il4 gene expression in T cells, the Il4 silencer (22) and HS4 (4). In striking contrast, this element behaves as an enhancer in basophils. Thus, the HS4 element has opposite functions in T cells and basophils and may play an important role in up-regulation of the Il4 gene in a basophil-specific manner. However, further investigation using deletion mutants of the Il4 silencer and HS4 will be required to test this idea. A more-detailed understanding of the functional relevance of the multiple Il4 regulatory elements at the single-cell level may provide new insights into their behavior and functional significance in allergic immune diseases and parasitic infection.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to H. Fujimoto, Y. Matsuno, Y. Suzuki, and M. Nakamura for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Grants in Aid for Scientific Research (B) and Grants in Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas programs of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan. Yasutaka Motomura is the recipient of a Junior Research Associate grant at RIKEN. S. Tanaka is a recipient of the Special Postdoctoral Researchers program at RIKEN.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas, A. K., K. M. Murphy, and A. Sher. 1996. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature 383:787-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal, S., O. Avni, and A. Rao. 2000. Cell-type-restricted binding of the transcription factor NFAT to a distal IL-4 enhancer in vivo. Immunity 12:643-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal, S., and A. Rao. 1998. Modulation of chromatin structure regulates cytokine gene expression during T cell differentiation. Immunity 9:765-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansel, K. M., R. J. Greenwald, S. Agarwal, C. H. Bassing, S. Monticelli, J. Interlandi, I. M. Djuretic, D. U. Lee, A. H. Sharpe, F. W. Alt, and A. Rao. 2004. Deletion of a conserved Il4 silencer impairs T helper type 1-mediated immunity. Nat. Immunol. 5:1251-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baguet, A., and M. Bix. 2004. Chromatin landscape dynamics of the Il4-Il13 locus during T helper 1 and 2 development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:11410-11415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, M. A., and J. Hural. 1997. Functions of IL-4 and control of its expression. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 17:1-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Andres, B., E. Rakasz, M. Hagen, M. L. McCormik, A. L. Mueller, D. Elliot, A. Metwali, M. Sandor, B. E. Britigan, J. V. Weinstock, and R. G. Lynch. 1997. Lack of Fc-epsilon receptors on murine eosinophils: implications for the functional significance of elevated IgE and eosinophils in parasitic infections. Blood 89:3826-3836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dombrowicz, D., and M. Capron. 2001. Eosinophils, allergy and parasites. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13:716-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galli, S. J. 2000. Mast cells and basophils. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 7:32-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galli, S. J., J. Kalesnikoff, M. A. Grimbaldeston, A. M. Piliponsky, C. M. Williams, and M. Tsai. 2005. Mast cells as “tunable” effector and immunoregulatory cells: recent advances. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:749-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galli, S. J., S. Nakae, and M. Tsai. 2005. Mast cells in the development of adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 6:135-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gessner, A., K. Mohrs, and M. Mohrs. 2005. Mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils acquire constitutive IL-4 and IL-13 transcripts during lineage differentiation that are sufficient for rapid cytokine production. J. Immunol. 174:1063-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory, G. D., S. S. Raju, S. Winandy, and M. A. Brown. 2006. Mast cell IL-4 expression is regulated by Ikaros and influences encephalitogenic Th1 responses in EAE. J. Clin. Investig. 116:1327-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henkel, G., and M. A. Brown. 1994. PU. 1 and GATA: components of a mast cell-specific interleukin 4 intronic enhancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7737-7741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henkel, G., D. L. Weiss, R. McCoy, T. Deloughery, D. Tara, and M. A. Brown. 1992. A DNase I-hypersensitive site in the second intron of the murine IL-4 gene defines a mast cell-specific enhancer. J. Immunol. 149:3239-3246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hida, S., M. Tadachi, T. Saito, and S. Taki. 2005. Negative control of basophil expansion by IRF-2 critical for the regulation of Th1/Th2 balance. Blood 106:2011-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hural, J. A., M. Kwan, G. Henkel, M. B. Hock, and M. A. Brown. 2000. An intron transcriptional enhancer element regulates IL-4 gene locus accessibility in mast cells. J. Immunol. 165:3239-3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawakami, T., and S. J. Galli. 2002. Regulation of mast-cell and basophil function and survival by IgE. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:773-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khodoun, M. V., T. Orekhova, C. Potter, S. Morris, and F. D. Finkelman. 2004. Basophils initiate IL-4 production during a memory T-dependent response. J. Exp. Med. 200:857-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubo, M., R. L. Kincaid, and J. T. Ransom. 1994. Activation of the interleukin-4 gene is controlled by the unique calcineurin-dependent transcriptional factor NF(P). J. Biol. Chem. 269:19441-19446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo, M., R. L. Kincaid, D. R. Webb, and J. T. Ransom. 1994. The Ca2+/calmodulin-activated, phosphoprotein phosphatase calcineurin is sufficient for positive transcriptional regulation of the mouse IL-4 gene. Int. Immunol. 6:179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubo, M., J. Ransom, D. Webb, Y. Hashimoto, T. Tada, and T. Nakayama. 1997. T-cell subset-specific expression of the IL-4 gene is regulated by a silencer element and STAT6. EMBO J. 16:4007-4020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, G. R., C. G. Spilianakis, and R. A. Flavell. 2005. Hypersensitive site 7 of the TH2 locus control region is essential for expressing TH2 cytokine genes and for long-range intrachromosomal interactions. Nat. Immunol. 6:42-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo, C., E. Burgeon, J. A. Carew, P. G. McCaffrey, T. M. Badalian, W. S. Lane, P. G. Hogan, and A. Rao. 1996. Recombinant NFAT1 (NFATp) is regulated by calcineurin in T cells and mediates transcription of several cytokine genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3955-3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masuda, A., Y. Yoshikai, H. Kume, and T. Matsuguchi. 2004. The interaction between GATA proteins and activator protein-1 promotes the transcription of IL-13 in mast cells. J. Immunol. 173:5564-5573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Min, B., M. Prout, J. Hu-Li, J. Zhu, D. Jankovic, E. S. Morgan, J. F. Urban, Jr., A. M. Dvorak, F. D. Finkelman, G. LeGros, and W. E. Paul. 2004. Basophils produce IL-4 and accumulate in tissues after infection with a Th2-inducing parasite. J. Exp. Med. 200:507-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohrs, K., D. P. Harris, F. E. Lund, and M. Mohrs. 2005. Systemic dissemination and persistence of Th2 and type 2 cells in response to infection with a strictly enteric nematode parasite. J. Immunol. 175:5306-5313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohrs, K., A. E. Wakil, N. Killeen, R. M. Locksley, and M. Mohrs. 2005. A two-step process for cytokine production revealed by IL-4 dual-reporter mice. Immunity 23:419-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohrs, M., C. M. Blankespoor, Z. E. Wang, G. G. Loots, V. Afzal, H. Hadeiba, K. Shinkai, E. M. Rubin, and R. M. Locksley. 2001. Deletion of a coordinate regulator of type 2 cytokine expression in mice. Nat. Immunol. 2:842-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohrs, M., K. Shinkai, K. Mohrs, and R. M. Locksley. 2001. Analysis of type 2 immunity in vivo with a bicistronic IL-4 reporter. Immunity 15:303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monticelli, S., K. M. Ansel, D. U. Lee, and A. Rao. 2005. Regulation of gene expression in mast cells: micro-RNA expression and chromatin structural analysis of cytokine genes, p. 179-190. In D. J. Chadwick and J. Goode (ed.), Mast cells and basophils: development, activation and roles in allergic/autoimmune disease, no. 271. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ. [PubMed]

- 32.Monticelli, S., D. U. Lee, J. Nardone, D. L. Bolton, and A. Rao. 2005. Chromatin-based regulation of cytokine transcription in Th2 cells and mast cells. Int. Immunol. 17:1513-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakano, T., Y. Kanakura, H. Asai, and Y. Kitamura. 1987. Changing processes from bone marrow-derived cultured mast cells to connective tissue-type mast cells in the peritoneal cavity of mast cell-deficient w/wv mice: association of proliferation arrest and differentiation. J. Immunol. 138:544-549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otsu, K., T. Nakano, Y. Kanakura, H. Asai, H. R. Katz, K. F. Austen, R. L. Stevens, S. J. Galli, and Y. Kitamura. 1987. Phenotypic changes of bone marrow-derived mast cells after intraperitoneal transfer into W/Wv mice that are genetically deficient in mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 165:615-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paul, W. E. 1991. Interleukin-4 production by Fc epsilon R+ cells. Skin Pharmacol. 4(Suppl. 1):8-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakai, K., and J. Miyazaki. 1997. A transgenic mouse line that retains Cre recombinase activity in mature oocytes irrespective of the cre transgene transmission. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 237:318-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saparov, A., F. H. Wagner, R. Zheng, J. R. Oliver, H. Maeda, R. D. Hockett, and C. T. Weaver. 1999. Interleukin-2 expression by a subpopulation of primary T cells is linked to enhanced memory/effector function. Immunity 11:271-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seki, N., M. Miyazaki, W. Suzuki, K. Hayashi, K. Arima, E. Myburgh, K. Izuhara, F. Brombacher, and M. Kubo. 2004. IL-4-induced GATA-3 expression is a time-restricted instruction switch for Th2 cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 172:6158-6166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherman, M. A., T. Y. Nachman, and M. A. Brown. 1999. Cutting edge: IL-4 production by mast cells does not require c-maf. J. Immunol. 163:1733-1736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solymar, D. C., S. Agarwal, C. H. Bassing, F. W. Alt, and A. Rao. 2002. A 3′ enhancer in the IL-4 gene regulates cytokine production by Th2 cells and mast cells. Immunity 17:41-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takemoto, N., N. Koyano-Nakagawa, T. Yokota, N. Arai, S. Miyatake, and K. Arai. 1998. Th2-specific DNase I-hypersensitive sites in the murine IL-13 and IL-4 intergenic region. Int. Immunol. 10:1981-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka, S., J. Tsukada, W. Suzuki, K. Hayashi, K. Tanigaki, M. Tsuji, H. Inoue, T. Honjo, and M. Kubo. 2006. The interleukin-4 enhancer CNS-2 is regulated by Notch signals and controls initial expression in NKT cells and memory-type CD4 T cells. Immunity 24:689-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voehringer, D., T. A. Reese, X. Huang, K. Shinkai, and R. M. Locksley. 2006. Type 2 immunity is controlled by IL-4/IL-13 expression in hematopoietic non-eosinophil cells of the innate immune system. J. Exp. Med. 203:1435-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voehringer, D., D. B. Rosen, L. L. Lanier, and R. M. Locksley. 2004. CD200 receptor family members represent novel DAP12-associated activating receptors on basophils and mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:54117-54123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walsh, G. M. 2001. Eosinophil granule proteins and their role in disease. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 8:28-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wasserman, S. I. 1990. Mast cell biology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 86:590-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiss, D. L., and M. A. Brown. 2001. Regulation of IL-4 production in mast cells: a paradigm for cell-type-specific gene expression. Immunol. Rev. 179:35-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshimoto, T., B. Min, T. Sugimoto, N. Hayashi, Y. Ishikawa, Y. Sasaki, H. Hata, K. Takeda, K. Okumura, L. Van Kaer, W. E. Paul, and K. Nakanishi. 2003. Nonredundant roles for CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells and conventional CD4+ T cells in the induction of immunoglobulin E antibodies in response to interleukin 18 treatment of mice. J. Exp. Med. 197:997-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]