Abstract

Mobile genetic elements that reside in gene-dense genomes face the problem of avoiding devastating insertional mutagenesis of genes in their host cell genomes. To meet this challenge, some Saccharomyces cerevisiae long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons have evolved targeted integration at safe sites in the immediate vicinity of tRNA genes. Integration of yeast Ty3 is mediated by interactions of retrotransposon protein with the tRNA gene-specific transcription factor IIIB (TFIIIB). In the genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, the non-LTR retrotransposon TRE5-A integrates ∼48 bp upstream of tRNA genes, yet little is known about how the retrotransposon identifies integration sites. Here, we show direct protein interactions of the TRE5-A ORF1 protein with subunits of TFIIIB, suggesting that ORF1p is a component of the TRE5-A preintegration complex that determines integration sites. Our results demonstrate that evolution has put forth similar solutions to prevent damage of diverse, compact genomes by different classes of mobile elements.

Retrotransposons are ancient mobile elements that amplify in eukaryotic cells via reverse transcription of RNA intermediates (9). Integration of cDNA copies into the host cell genome is a default mechanism in retrotransposition and causes a constant threat of insertion mutagenesis, which may be particularly harmful in host cells with gene-dense genomes. Targeting the vicinity of tRNA genes is frequently used by retrotransposable elements to avoid gene disruptions upon retrotransposition. Two intriguing examples of this kind of adaptation to compact genomes are the Saccharomyces cerevisiae long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons Ty1 and Ty3 (3, 37) and the tRNA gene-targeted retroelements (TREs), a family of non-LTR retrotransposons from the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum (14, 31), discussed in this paper.

TRE5-A, formerly known as DRE, shows a strong bias for integration sites ∼48 bp upstream of D. discoideum tRNA genes (47). This element has two open reading frames (ORF) named ORF1 and ORF2. Based on amino acid similarity with other non-LTR retrotransposons, particularly the human L1 element (30), it is suggested that the ORF2 protein (ORF2p) of TRE5-A possesses reverse transcriptase and endonuclease activities. Little is known about the function of the TRE5-A-encoded ORF1 protein (ORF1p). Both ORF1p and ORF2p encoded in the human L1 element show a strong cis preference in that they bind preferentially to their own RNAs at the sites of translation and form cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein particles (RNPs) (16, 26, 27). The role of ORF1p within the RNP preintegration complex may be primarily to protect the RNA from degradation, but it has also been noted that ORF1p may have important nucleic acid chaperone functions at the integration site during reverse transcription and integration (34).

D. discoideum tRNA genes are scattered on all chromosomes and do not show significant DNA sequence conservation in their flanking regions (11). Thus, we hypothesized that protein interactions between a TRE5-A-encoded protein and an RNA polymerase III (Pol III)-specific transcription factor may be responsible for the recognition of tRNA genes as integration sites (40). We have recently shown that targeting of tRNA genes by TRE5-A requires an active binding site—the B box—for the Pol III transcription factor IIIC (TFIIIC) (40). The ribosomal 5S gene, which is a typical Pol III gene, is also targeted by TRE5-A under experimental conditions (40). Although the 5S gene lacks a B box promoter, its transcription does also depend on TFIIIC. Thus, although it seemed clear that TFIIIC is required for recognition of integration sites by TRE5-A, it remained elusive whether D. discoideum TFIIIC (DdTFIIIC) mediates targeting of TRE5-A to tRNA genes by providing direct protein contacts with a protein in the TRE5-A preintegration complex or whether the role of TFIIIC is to recruit TFIIIB, the Pol III transcription initiation factor, as a binding partner for TRE5-A proteins that determines integration sites.

TFIIIB from the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ScTFIIIB) is a heterotrimeric complex composed of TATA-binding factor (ScTBP), TFIIB-related factor (ScBrf1), and TFIIIB double prime (ScBdp1) (13). ScTBP and ScBrf1 form a stable complex that is also referred to as ScB′ and can be separated from ScB′′ (ScBdp1) by chromatography (20). Homo sapiens TFIIIB (HsTFIIIB) can be separated into two parts by chromatography (42). Transcription of human tRNA genes and the 5S rRNA gene is controlled by TFIIIC2, which recruits HsTFIIIBb (a stable HsTBP-HsBrf1 complex), and TFIIIC1, which may be identical to yeast B′′ and interacts reversibly with preformed TFIIIC2-HsTFIIIBb complexes (44, 45). HsTFIIIBa is comprised of a loosely associated complex of HsTBP, HsBrf2, and HsBdp1 that can be assembled in vitro on the TATA box upstream of the human U6 snRNA gene (42).

Here, we expressed DdTFIIIB subunits in a bacterial two-hybrid system and we show that the TRE5-A-encoded ORF1 protein (ORF1p) interacts directly with all three subunits of DdTFIIIB. Deletion and mutagenesis studies revealed that an amino-terminal domain of ORF1p interacts with an α-helix exposed on the convex surface of DdTBP. The data strongly suggest that ORF1p is a critical component of a TRE5-A preintegration complex and that ORF1p is responsible for the selection of tRNA genes as chromosomal integration sites. The recognition of the Pol III-specific TFIIIB has been developed repeatedly by different types of retrotransposons in both yeast and social amoebae and represents a means to avoid deleterious mutagenesis of compact genomes by retrotransposon activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

DdTFIIIB subunits were cloned using DNA sequence information available at Dictybase (http://dictybase.org). DdTBP (Dictybase entry DDB0185066), DdBrf1 (Dictybase entry DDB0204087), and DdBdp1 (Dictybase entry DDB0220508) genes were synthesized by PCR using either genomic DNA or cDNA templates prepared from D. discoideum AX2 cells. For convenience, DdBrf1 was split into an amino-terminal part homologous to TFIIB, DdBrf11-270, and the carboxy-terminal part DdBrf1271-706. TRE5-A ORF1 and ORF2 DNAs were amplified from plasmid pB3, which contains a nearly full-length TRE5-A.1 (32). ORF2 (3,456 bp) was subcloned in three parts according to the encoded enzyme functions: the endonuclease (ENp, nucleotide positions 1704 to 2669 of a full-length TRE5-A.1), reverse transcriptase (RTp, positions 2638 to 3936), and histidine/cysteine-rich (HCp, positions 3912 to 5159) domains. All PCR primers were designed to introduce NotI restriction sites at both ends of the PCR fragments. All PCR fragments were subcloned in pGEM-T (Promega).

At the 5′ end of each PCR fragment, the NotI site was followed by a Kozak consensus sequence (25) (5′-GCG GCC GCA ATG G-3′; translation initiation codon underlined) to allow for efficient translation in a mammalian in vitro translation system. For this purpose, PCR fragments were inserted into the NotI site of the Promega pTNT vector.

Two-hybrid experiments were performed with a BacterioMatch II system (Stratagene). The PCR fragments were inserted into the NotI sites of pBT and pTRG. Truncated versions of TRE5-A ORF1 and DdTBP were produced by inserting new NotI sites into the cloned cDNAs at the appropriate positions by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis in the respective pTNT vector derivatives. The resulting shorter DNA fragments were cloned into pBT and pTRG. DdTBP(EES) (a triple mutant of full-length DdTBP1-205 with mutations of three arginine residues in the amino-terminal core domain of DdTBP [R93E, R97E, and R101S]) was generated by single site-directed mutagenesis in pTNT-DdTBP and subcloning of the NotI fragment of DdTBP1-205(EES) into pBT.

A genetic fusion of maltose-binding protein (MBP) and TRE5-A ORF1 was generated in the vector pMAL-c2X (New England Biolabs). First, a NotI restriction site compatible with the BacterioMatch II vectors was introduced into pMAL-c2X by site-directed mutagenesis. The ORF1 PCR fragment was digested with NotI and inserted into pMAL-c2X(Not).

Bacterial two-hybrid system.

Experiments with the BacterioMatch II two-hybrid system were performed essentially as detailed in the provided manual. Briefly, vectors carrying bait (pBT) and prey (pTRG) genes were cotransformed into the BacterioMatch II reporter strain. Clones were selected on agar plates containing chloramphenicol and tetracycline. At least 30 independent clones from three independent cotransformations were then streaked onto selection plates. Growth in the absence of histidine was tested on selection plates containing 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) at final concentrations ranging from 2 to 6 mM.

In vitro transcription/translation and pull-down experiments.

MBP-ORF1 and MBP were produced in W3110 bacteria. Bacteria (50 ml) from a logarithmically growing culture were induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) to produce the recombinant proteins. After 2 h of induction, bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml of binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA). Cells were lysed by sonication, and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. The supernatant was incubated with 100 μl amylose resin (New England Biolabs) for 30 min at 4°C. Unbound proteins were removed by washing with binding buffer. A freshly loaded column was prepared for each pull-down. An aliquot of 10 μl of each loaded resin was checked for protein loading. The resin was boiled in Laemmli sample buffer, and proteins bound to the amylose resin were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie staining.

35S-labeled proteins were generated with a TNT T7 coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega) according to the provided protocol. Proteins were labeled by adding 20 μCi of [35S]methionine (Amersham) to the reaction. The reaction mixes were added to the washed, protein-loaded amylose resins. After incubation for 2 h with shaking, the resins were washed three times with binding buffer. The remaining resins were boiled in Laemmli sample buffer, and 35S-labeled proteins were analyzed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels followed by autoradiography.

Modeling of D. discoideum TBP.

The amino acid sequence of DdTBP (Dictybase entry DDB0185066) was modeled onto the solved crystal structure of human TBP (36) (SwissProt P20226) by use of the SWISS-MODEL program (38) and template file 1CDW.pdb. Figures were made by PyMOL (10).

RESULTS

Composition of DdTFIIIB.

We have shown recently that integration of TRE5-A upstream of D. discoideum tRNA genes requires a functional tRNA gene promoter, suggesting active involvement of DdTFIIIC in the targeting process (40). Since DdTFIIIB is predicted to cover the 5′ end of a tRNA gene close to the natural integration site of TRE5-A, we proposed that TFIIIC may be required only to recruit DdTFIIIB. Thus, DdTFIIIB may provide a platform for direct protein contacts with proteins derived from the TRE5-A ribonucleoprotein preintegration complex.

Based on data from the related human L1 retrotransposon (26), we assumed that the TRE5-A preintegration complex may contain TRE5-A RNA, ORF1p, and ORF2p. We wanted to perform a systematic survey of protein-protein interactions between TRE5-A-encoded proteins and DdTFIIIB subunits. However, little was known at the beginning of these experiments about the Pol III transcription factors involved in tRNA gene expression in D. discoideum cells. Whole-genome sequencing of the D. discoideum genome has recently been finished (11), and the putative D. discoideum proteome has been listed in Dictybase, the Internet platform for Dictyostelium research (5). This allowed us to track putative DdTFIIIB subunits in silico.

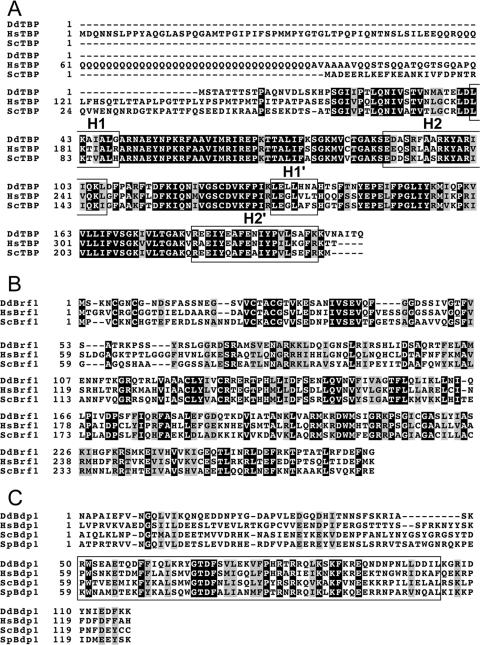

DdTBP contains 205 amino acids and is encoded by the gene tbpA (Dictybase entry DDB0185066). The 22.8-kDa protein has 69% and 68% sequence identity with the conserved carboxy-terminal part of its yeast and human orthologs, respectively (Fig. 1A). DdTBP lacks an amino-terminal extension like the one present in HsTBP.

FIG. 1.

DdTFIIIB subunits. (A) Clustal X alignment of DdTBP with HsTBP and ScTBP. The 22.8-kDa DdTBP has 69% and 68% sequence identity with the conserved carboxy-terminal part of its yeast and human orthologs, respectively. Exposed α-helices along the convex surface of TBP are indicated in boxes. DdTBP is encoded by gene tbpA and is listed under Dictybase entry DDB0185066 (http://dictybase.org/). (B) Identification of a DdBrf1 ortholog. Brf1 proteins can be divided into two functional domains: the conserved TFIIB-like amino-terminal domain and highly divergent carboxy-terminal domains. Clustal X alignment of the conserved TFIIB-homologous region of DdBrf1 (DdBrf1-270) with corresponding regions of HsBrf1 and ScBrf1. The TFIIB-like domain shows 42% and 48% sequence identity with the corresponding regions in ScBrf1 and HsBrf1, respectively. DdBrf1 is 706 amino acids in length (79.9 kDa) and is encoded by gene brf1 (Dictybase entry DDB0204087). (C) Identification of a Bdp1 ortholog in the D. discoideum genome. Use of full-length ScBdp1 as the query sequence in Blastp searches (1) identified a protein that could be aligned within a central domain spanning 130 amino acids with corresponding regions of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Bdp1 (SpBdp1) and ScBdp1 and the human ortholog (HsBdp1). The SANT domain (17) is boxed. DdBdp1 is encoded by gene bdp1 (Dictybase entry DDB0220508).

DdBrf1 (gene brf1; Dictybase entry DDB0204087) is 706 amino acids in length (79.9 kDa) and can be divided into two functional domains. A TFIIB-like amino-terminal domain spans ca. 270 amino acids and has 42% and 48% sequence identity with the corresponding regions in ScBrf1 and HsBrf1, respectively (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the carboxy-terminal domain of DdBrf1 (ca. 430 amino acids) shows very weak homology with any other Brf1. In particular, no homology with regions I to III (28) could be identified in DdBrf1.

A putative D. discoideum Bdp1 ortholog was recognized by Blastp searches (1) of Dictybase sequences carried out using either ScBdp1 or HsBdp1 as the query sequence. The similarity to the D. discoideum ortholog (DdBdp1; Dictybase entry DDB0220508) is significant but restricted to only about 130 amino acids that include the SANT domain (Fig. 1C). The SANT domain of ScBdp1 has recently been shown to interact with the ScBrf1 homology region II in yeast TFIIIB (21). DdBdp1, encoded by the gene bdp1, contains 457 amino acids and has a predicted molecular mass of 53.0 kDa.

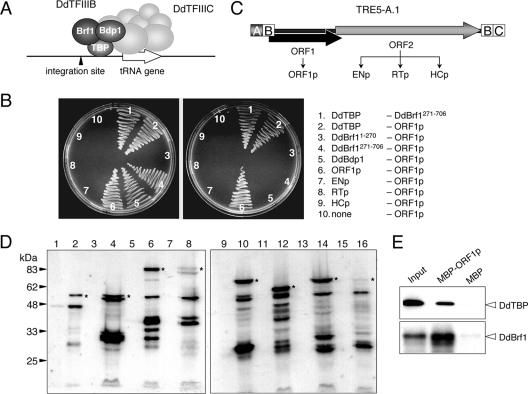

Taken together, the available genome sequence data support the presence of a three-subunit TFIIIB in D. discoideum cells (Fig. 2A). This information was used to study interactions of DdTFIIIB subunits and TRE5-A proteins in a BacterioMatch II two-hybrid system.

FIG. 2.

DdTFIIIB subunits interact with TRE5-A ORF1p. (A) Model for initiation of tRNA gene transcription in D. discoideum. DdTFIIIC binds to the tRNA gene-internal B box sequence and then recruits DdTFIIIB. The latter consists of the three subunits DdTBP, DdBrf1, and DdBdp1 and occupies space at the 5′ end of the tRNA gene close to the TRE5-A integration site. (B) DdTFIIIB subunits were tested for interaction with TRE5-A-derived ORF1p and ORF2p proteins. Selection plates contained minimal medium without histidine that were supplemented with either 5 mM 3-AT (left) or 6 mM 3-AT (right). Combinations of two-hybrid vectors are listed; the left column represents proteins expressed from pBT vectors, and the right column lists proteins cloned into the pTRG vector. (C) Schematic presentation of full-length TRE5-A.1 and the derived proteins tested in two-hybrid assays. The ORF2 protein was cloned in three parts according to the predicted ENp and RTp domains and the HCp domain of unknown function. Modules A, B, and C represent 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of TRE5-A.1. (D) Expression of pBT-derived fusion proteins in the bacterial two-hybrid reporter strain. Western blot showing expression levels of DdTFIIIB subunits and TRE5-A-encoded ORF proteins. The corresponding DNA fragments, cloned in vector pBT, were transformed into the BacterioMatch II reporter strain. Bacteria were grown at 30°C. Extracts were prepared from whole cells and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoretic transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes, proteins were stained with a commercial polyclonal antiserum directed against the λcI repressor protein encoded in the pBT vector (Stratagene). Lanes 1 and 2, DdTBP; lanes 3 and 4, DdBrf1-270; lanes 5 and 6, DdBrf271-706; lanes 7 and 8, DdBdp1; lanes 9 and 10, ORF1p; lanes 11 and 12, ENp; lanes 13 and 14, RTp; lanes 15 and 16, HCp. Lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 show extracts of bacteria without induction of recombinant protein expression. In lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16, expression of recombinant proteins was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 3 h at 30°C. Asterisks denote the bands corresponding to the molecular masses of the full-length λcI fusion proteins. (E) Pull-down experiment. 35S-labeled DdTBP or full-length DdBrf1 was incubated with bacterially expressed MBP or an MBP-ORF1p fusion protein. Bound DdTBP or DdBrf1 was subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. Input refers to 10% of a labeling reaction.

Protein interactions between TFIIIB subunits.

We first screened for protein interactions between the individual DdTFIIIB subunits. DdTBP (205 amino acids) and DdBdp1 (457 amino acids) were expressed in the bacterial two-hybrid vectors as complete genes, whereas DdBrf1 was separated into the TFIIB-homologous amino-terminal domain DdBrf11-270 and the carboxy-terminal remainder (DdBrf1271-706). None of the subcloned DdTFIIIB subunits displayed self-activation when introduced into the bacterial two-hybrid reporter strain (data not shown). We found a robust interaction of DdTBP with DdBrf1271-706 but not with the amino-terminal TFIIB-like domain DdBrf11-270 (Fig. 2B). This result was anticipated considering that ScBrf1 is known to form a stable complex with ScTBP (referred to as ScB′) in yeast cells via homology region II in the carboxy-terminal half of ScBrf1 (19, 22).

We did not detect significant interactions between DdTBP and DdBdp1. Although this may have been due to poor expression of the Bdp1 subunit of DdTFIIIB in the bacterial cells, we should note that we observed an interaction between DdBdp1 and DdBrf1271-706 that was only marginally above background growth of mock-transformed bacteria, which argues for sufficient expression of DdBdp1 in the two-hybrid reporter strain (data not shown).

No interactions between TRE5-A ORF2p and TFIIIB subunits.

TRE5-A ORF2p was divided into three separate proteins according to the predicted functional domains: ENp, RTp, and HCp (Fig. 2C). The ENp-encoding DNA fragment could not be cloned into the two-hybrid vectors unless an active site mutation was introduced to inactivate the deduced EN protein. The D188G mutation of TRE5-A ENp corresponds to the D205G mutation of human L1 ENp previously shown to inactivate the enzyme (12). In previous experiments, we had noticed that ENp aggregates in low-ionic-strength buffers in vitro and forms cytosolic aggregates in vivo (15). The two-hybrid screenings revealed reproducible ENp-ENp interactions (data not shown), suggesting that full-length TRE5-A.1 ORF2p contains a dimerization motif located within the EN domain. No interactions between any of the ORF2p domain proteins and ORF1p were found (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, no significant interactions between any of the TRE5-A ORF2-derived proteins and any of the DdTFIIIB subunits were detected. The absence of ORF2p-TFIIIB interactions was apparently not due to poor expression of these proteins in the reporter strain, as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 2D).

Interactions among ORF1 molecules.

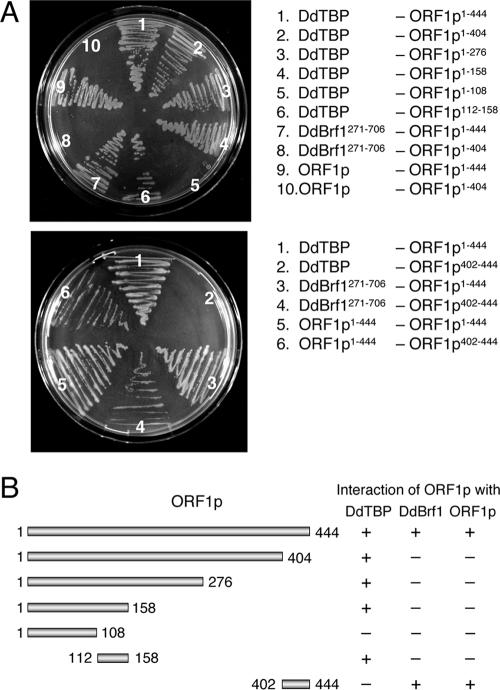

We observed robust interactions between ORF1p molecules (Fig. 2B). Dimerization and oligomerization of ORF1p were also observed in previous biochemical analyses, and it was found that a fusion protein consisting of green fluorescent protein and ORF1p expressed in D. discoideum cells formed large cytosolic aggregates (15). Full-length ORF1p (ORF1p1-444) is predicted to contain coil domains located roughly between amino acids 220 to 260 and 410 to 444, the latter representing the carboxy terminus of the protein. We assumed that formation of ORF1p dimers or multimers might be dependent on the coil conformations of the protein. Thus, we generated a carboxy-terminal-deleted version of ORF1p, ORF1p1-404. As shown in Fig. 3A, deletion of 40 amino acids from the carboxy terminus of ORF1p abolished interaction of ORF1p with other ORF1p molecules in the two-hybrid experiments. It was unlikely that loss of ORF1p interaction in ORF1p1-404 was due to improper expression or folding of the protein, since ORF1p1-404 interacted readily with DdTBP (see below). We directly tested interaction of the domain spanning amino acids 402 to 444 (i.e., the carboxy terminus of ORF1p) with other ORF1p molecules. ORF1p402-444 was cloned into two-hybrid vector pTRG and tested against full-length ORF1p. The carboxy-terminal tail of ORF1p was sufficient to interact with full-length ORF1p, suggesting that the carboxy terminus of ORF1p provides a dimerization platform (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Determination of protein interaction domains on ORF1p. (A) Two-hybrid assays were performed to determine binding domains for DdTBP and DdBrf1 on ORF1p. The selection plates contained minimal medium without histidine that was supplemented with 5 mM 3-AT. Combinations of two-hybrid vectors are listed; the left column represents proteins expressed from pBT vectors, and the right column lists proteins cloned into the pTRG vector. (B) Presentation of ORF1p deletions tested for interaction with ORF1p (dimerization), DdTBP, and DdBrf1. + and − refer to growth of transformants on selection plates containing 5 mM 3-AT.

ORF1p binds to TFIIIB subunits.

ORF1p showed a robust interaction with DdTFIIIB subunit DdTBP even when the highly stringent concentration of 6 mM 3-AT was used in the two-hybrid assay (Fig. 2B). Significant interactions between ORF1p and the TFIIIB subunits DdBrf1 and DdBdp1 were also observed. These interactions were lost at moderate concentrations of 3-AT in the assay (Fig. 2B), which may reflect differences in the expression levels of the DdTFIIIB subunits in the reporter strain (as determined by Western blotting of pBT-derived fusion proteins) (Fig. 2D).

Interaction of ORF1p with DdTBP and DdBrf1 was confirmed in biochemical pull-down experiments. We expressed ORF1p in bacteria as a genetic fusion with MBP. MBP-ORF1p or MBP alone was loaded onto amylose resin in parallel incubations. The putative binding partners of ORF1p were 35S-labeled proteins produced in coupled in vitro transcription/translation reactions. As shown in Fig. 2E, both 35S-DdTBP and 35S-DdBrf could be precipitated with MBP-ORF1p but not with the MBP control. Pull-down experiments with DdBdp1 were not feasible due to insufficient 35S labeling of the protein.

We tested a series of carboxy-terminal ORF1p deletions to narrow down the sites of interaction with DdTBP and DdBrf1. As shown in Fig. 3, DdTBP interacted with all deletions tested, including ORF1p1-158, but did not bind to ORF1p1-108. Thus, the domain on ORF1p that interacts with DdTBP must be located within a region spanning amino acids 108 to 158 of ORF1p. This was in fact confirmed by showing interaction of ORF1p112-158 with DdTBP (Fig. 3).

The ORF1p deletion series depicted in Fig. 3B was also used to map the binding site of DdBrf1 on the ORF1 protein. The DdBrf1-ORF1p interaction was abolished by deleting the last 40 amino acids of ORF1p, which are also required for ORF1p dimerization (Fig. 3A). We confirmed by using the ORF1p402-444 construct that Brf1 binds directly at the carboxy terminus of ORF1p (Fig. 3A). Thus, DdBrf1 may compete with ORF1p within a TRE5-A preintegration complex for a binding site at the carboxy termini of other ORF1p molecules.

Mapping DdTBP surfaces required for interaction with DdBrf1 and ORF1p.

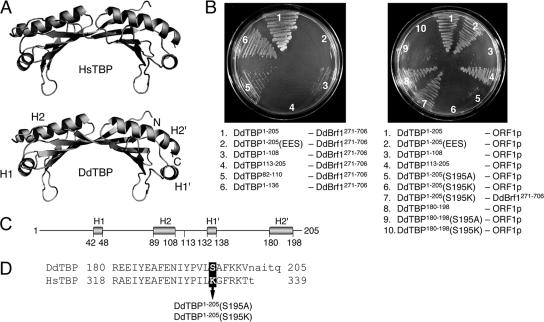

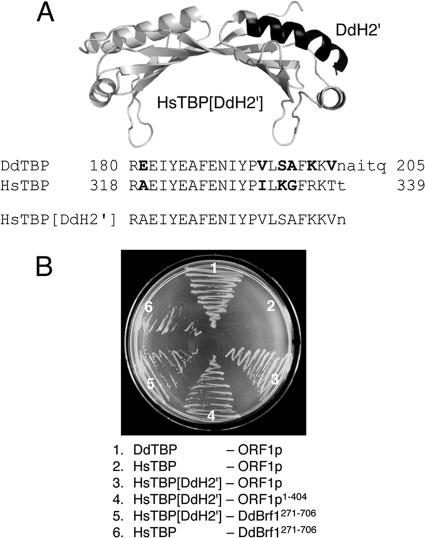

HsTBP and DdTBP show 68% sequence identity in the carboxy-terminal conserved domain (Fig. 1A). We modeled the DdTBP sequence onto the solved crystal structure of HsTBP and found that the two proteins are strikingly similar (Fig. 4A). Thus, we assumed that known protein interaction interfaces in the yeast TBP/Brf1 dimer (18) may also exist in the DdTBP/Brf1 complex.

FIG. 4.

Determination of protein binding sites on DdTBP. (A) The crystal structure of HsTBP was used as a template to model DdTBP (see Materials and Methods). The α-helices along the convex surface of TBP are indicated. The N and C termini of the protein are also indicated. (B) Two-hybrid assays for the interaction of DdTBP mutants with DdBrf1 (left) and ORF1p (right). Selections were performed on plates containing 5 mM 3-AT. Combinations of two-hybrid vectors are listed; the left column represents proteins expressed from pBT vectors, and the right column lists proteins cloned into the pTRG vector. (C) Delineation of amino acid positions of α-helices H1, H2, H1′, and H2′ in DdTBP (total length, 205 amino acids). (D) Amino acid sequences of the carboxy termini of DdTBP and HsTBP. The α-helix H2′ is written in uppercase letters. The arrow depicts the S195A and S195K mutations in DdTBP tested in the two-hybrid experiments.

We split DdTBP at amino acid position 108 to separate the two symmetric core domains, DdTBP1-108 and DdTBP113-205. Then we tested both core domains for interactions with either DdBrf1 or ORF1p. We found that DdBrf1 interacted with DdTBP1-108 but not with DdTBP113-205. Conversely, ORF1p bound to DdTBP113-205 but not to DdTBP1-108 (Fig. 4B). Thus, DdTBP is able to interact with DdBrf1 and ORF1p via different core domains.

In HsTBP, a triple mutation of three arginine residues on the outer surface of α-helix H2 (R231E, R235E, and R239S) was shown to disrupt interaction with HsBrf1 (39). We produced a triple mutant of DdTBP with mutations at the corresponding sites in the amino-terminal core domain of DdTBP (R93E, R97E, and R101S), herein referred to as DdTBP1-205(EES). The DdTBP1-205(EES) mutant was unable to interact with DdBrf1 in the two-hybrid assay (Fig. 4B). This was not due to poor expression or instability of the mutant DdTBP1-205(EES) protein, because it interacted readily with ORF1p (see below).

The results described above suggested that helix H2 of DdTBP (amino acids 89 to 108) (Fig. 4C) is involved in the binding of DdBrf1. To show this directly, we cloned the helix H2 region (amino acids 82 to 110) into the two-hybrid vector and found that this helix supported an interaction of DdTBP with DdBrf1 (Fig. 4B). However, we consistently noticed that the binding of DdBrf1 to DdTBP1-108 was weaker than to DdTBP1-136. This suggested that other amino acids outside helix H2 may provide important protein contacts as well.

ORF1p bound to DdTBP113-205 but not to DdTBP1-108 (Fig. 4B). Given the high structural similarity of DdTBP and HsTBP, it was tempting to evaluate whether HsTBP would interact with ORF1p. This was not the case (discussed below). The alignment of HsTBP and DdTBP showed that the most pronounced differences in amino acid sequence are found within the H1′ and the H2′ α-helices of the C-terminal core domain (Fig. 1A). The H2′ helices of DdTBP and HsTBP differ in seven amino acids, five of which are located within the carboxy-terminal half of the helix (corresponding to the carboxy terminus of HsTBP) (Fig. 4D).

Maybe the most pronounced difference between the two TBP orthologs in this part of helix H2′ is Lys-333 (K333) in full-length HsTBP, which corresponds to Ser-195 (S195) in DdTBP. Modeling of the α-helices from both TBP orthologs suggested that K333 and S195 are exposed at the surfaces of the respective TBP proteins (not shown). To test whether the affinity of ORF1p for DdTBP is due to interaction with helix H2′, we introduced point mutations to change S195 in DdTBP to alanine and lysine. The S195A mutation in the full-length DdTBP molecule drastically reduced the affinity for ORF1p, yet it was poorly detectable on selection plates containing 5 mM 3-AT (Fig. 4B) and clearly visible on selection plates containing 2 to 4 mM 3-AT (data not shown). By contrast, the DdTBP1-205(S195K) mutant protein completely lost its affinity for ORF1p and no interaction could be shown even at low selection stringency in the two-hybrid assays. This result was not due to improper expression of the DdTBP1-205(S195K) protein, since it still interacted well with DdBrf1 (Fig. 4B). Thus, although a serine in position 195 in helix 2′ seems to be critical for interaction with ORF1p, the introduction of a neutral amino acid may be tolerated, whereas a positively charged amino acid completely disrupts TBP-ORF1p interaction in the context of the two-hybrid assay.

We should note that the DdTBP variant DdTBP1-136 revealed very weak but reproducible interaction with ORF1p. Thus, we cannot exclude that α-helix H1′, which is in close proximity to helix H2′ (Fig. 4A), also contributes to the binding of ORF1p to DdTBP. However, most of the affinity is contributed by helix H2′, which could in fact be tested directly. We cloned helix H2′ and tested its ability to interact with ORF1p in the two-hybrid assay. Binding of the isolated H2′ helix with ORF1p could be demonstrated (Fig. 4B). We also tested the S195A and S195K mutants of the isolated H2′ helix for binding and found results similar to those seen for the full-length DdTBP protein (Fig. 4B).

TRE5-A ORF1p binds to an HsTBP/DdTBP chimera.

As already mentioned, ORF1p did not bind to HsTBP. If the α-helix H2′ was the major determinant for the affinity to ORF1p for the DdTBP protein, then adaptation of the HsTBP H2′ helix to the DdTBP sequence might enable HsTBP to bind to ORF1p. To test this assumption, we performed site-directed mutagenesis on HsTBP to exchange variant amino acids in helix H2′ with the corresponding DdTBP sequence (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5B, unmodified HsTBP did not interact with ORF1p, although it bound to DdBrf1271-706. The HsTBP mutant containing the H2′ helix of DdTBP (named HsTBP[DdH2′]) bound reproducibly to both ORF1p and DdBrf1271-706. Thus, the major determinant of DdTBP/ORF1p interaction is in fact located within helix H2′ of TBP. However, we found that the interaction between the HsTBP[DdH2′] mutant and ORF1p was weaker than the interaction between DdTBP and ORF1p, suggesting that additional contacts on DdTBP outside of helix H2′ may be required.

FIG. 5.

TRE5-A ORF1p binds to an HsTBP/DdTBP chimera. (A) Modeled structure of HsTBP (light gray) containing the α-helix H2′ sequence of DdTBP (black). Variant amino acid positions in HsTBP and DdTBP helix 2H′ are written in bold. The amino acid sequence of the carboxy terminus in the chimeric HsTBP[DdH2′] protein is indicated. (B) Two-hybrid experiment showing the binding of HsTBP[DdH2′] to ORF1p and DdBrf1. Combinations of two-hybrid vectors are listed; the left column represents proteins expressed from pBT vectors, and the right column lists proteins cloned into the pTRG vector. Selections were performed on plates containing 3 mM 3-AT.

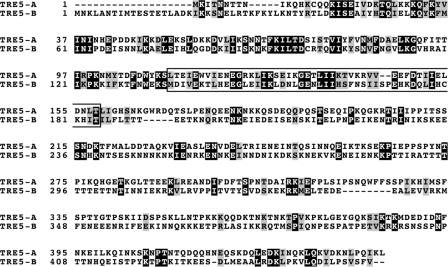

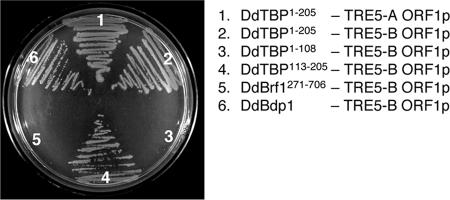

The TRE5-B ORF1 protein interacts with DdTFIIIB subunits.

TRE5-A and TRE5-B are distantly related retrotransposons that probably shared a common ancestor in the evolution of the TREs in the genome of D. discoideum (14). TRE5-B shows the same integration preference as TRE5-A, i.e., 45 to 50 bp upstream of tRNA genes (46). Hence, it was predicted that TRE5-B should use molecular interactions similar to those of TRE5-A to identify integration sites. However, the ORF1 proteins from both retrotransposons show only ∼25% amino acid identity (Fig. 6). To test whether TRE5-A and TRE5-B use similar mechanisms to identify tRNA genes as integration sites, we cloned full-length TRE5-B ORF1 into the pTRG vector and tested the protein for interaction with DdTFIIIB subunits in the two-hybrid assay. As shown in Fig. 7, TRE5-B ORF1p interacted with the carboxy-terminal symmetrical core of DdTBP like TRE5-A ORF1p. Interestingly, however, TRE5-B ORF1p bound to DdBdp1 but not to DdBrf1, which is the opposite of what we observed with TRE5-A ORF1p. Nevertheless, the results suggest that TRE5-A and TRE5-B retrotransposons identify integration sites by similar protein interactions with TFIIIB subunits.

FIG. 6.

Clustal X alignment of ORF1 proteins from D. discoideum TRE5-A and TRE5-B retrotransposons. The DdTBP-interacting region defined in TRE5-A ORF1p is boxed.

FIG. 7.

TRE5-B ORF1p binds to TFIIIB subunits. A two-hybrid experiment with TRE5-B ORF1p (cloned in pTRG) and the DdTFIIIB subunit proteins (cloned in pBT). The plate contained histidine-free medium supplemented with 5 mM 3-AT. Combinations of two-hybrid vectors are listed; the left column represents proteins expressed from pBT vectors, and the right column lists proteins cloned into the pTRG vector.

DISCUSSION

Selection of integration sites by TRE5-A requires ORF1p-TFIIIB interactions.

Bacterial two-hybrid assays revealed interactions between TRE5-A ORF1p and all three DdTFIIIB subunits. TRE5-A is the first non-LTR retrotransposon that has been shown to use direct protein contacts with chromatin constituents for integration site selection. Recent experiments have revealed a role for DdTFIIIC in the targeting of genes transcribed by RNA Pol III (i.e., tRNA genes and the ribosomal 5S gene) by TRE5-A (40). Here, we provide direct evidence that DdTFIIIB is the target of TRE5-A ORF1p, which suggests that the role of DdTFIIIC in tRNA gene targeting by TRE5-A is to recruit DdTFIIIB. Interestingly, analysis of yeast Pol III transcription initiation complexes revealed that TFIIIB occupies space in the 5′ flank of the tRNA gene limited to about 50 bp upstream of the first coding nucleotide of tRNA genes (23). Thus, it is plausible to assume that interaction of the TRE5-A preintegration complex with DdTFIIIB brings the substrate for reverse transcription and integration of the element in close proximity to the genomic DNA target (∼50 bp upstream of tRNA genes).

Target site selections by the yeast LTR retrotransposon Ty3 and non-LTR retrotransposon TRE5-A show interesting similarities. Ty3 integration in vivo is compromised by tRNA gene mutations in the A box or B box that also interfere with transcription (4). A low level of Ty3 integration occurs on target DNA occupied by TBP and Brf (the B′ complex), indicating that the Ty3 preintegration complex interacts with these TFIIIB subunits (48). Both halves of Brf1 enhance integration of Ty3, but the contribution of the amino-terminal TFIIB-like half of yeast Brf1 seems to be more pronounced (48). Ty3 integration frequency is strongly enhanced by ScBdp1, suggesting either that Ty3 may require additional contacts with this factor or that ScBdp1 changes the topology of the B′ complex in a way that enhances interaction of Ty3 with B′ (49). In addition, Ty3 integration competes for binding of Pol III to the transcription initiation complex (7). Thus, the Pol III transcription initiation complex consisting of tDNA, TFIIIC, and TFIIIB is the primary target for the Ty3 preintegration complex. D. discoideum TRE5-A integration in vivo is compromised by B box mutations predicted to interfere with tRNA gene expression (40). In contrast to protein contacts required for targeted Ty3 integration in yeast, the affinity of the TRE5-A protein for DdBrf1 is due to binding to the diverged carboxy-terminal domain rather than to the conserved amino-terminal TFIIB-like domain. However, similarly to Ty3 integration, TRE5-A likely uses additional contacts with Bdp1 for target site recognition.

The ORF1 protein is part of the TRE5-A preintegration complex.

We have shown recently that TRE5-A maintains an active population of retrotransposition-competent elements in the D. discoideum genome (2, 40). Phylogenetic analysis has pointed out a significant similarity between the TRE5-A-encoded ORF2 protein and the human L1 element (30). The properties of de novo-integrated TRE5-A copies (40) are consistent with the assumption that this element integrates using a canonical target-primed reverse transcription mechanism (6, 8, 29). Genetic evidence suggests that both ORF proteins encoded by the human L1 element are essential for retrotransposition (35). They also demonstrate a strong cis preference, which means that freshly translated ORF1 proteins bind preferentially to their own RNAs at the sites of translation (43). We have recently made progress in the generation of artificial TRE5-A elements, which are tagged by a system similar to the neomycin selection cassette used by Moran and coworkers to mobilize cloned L1 elements (35). In these assays, we found that TRE5-A ORF1p shows a pronounced cis preference (the cis preference of ORF2p could not yet be analyzed [O. Siol and T. Winckler, unpublished data]). Similarly to L1 elements (16, 27, 33), TRE5-A ORF1p forms large cytosolic particles (15). Since TRE5-A retrotransposition occurs in growing D. discoideum cells and no obvious nuclear localization sequences can be recognized on either TRE5-A ORF protein, it is possible that the TRE5-A RNPs await nuclear envelope breakdown and assess chromosomal integration targets during or after mitosis. Thus, formation of ribonucleoparticles by ORF1p and TRE5-A RNA may serve to protect and transport retroelement-derived transcripts to the site of integration. In addition, ORF1p may play a direct catalytic role in the target-primed reverse transcription process, as suggested by others for L1 ORF1p (27, 34). We have provided compelling evidence to suggest that ORF1p is part of the TRE5-A preintegration complex, since it is present at least long enough to facilitate target site selection.

Convergent evolution of targeting strategies.

The concept of specific targeting of tRNA gene loci has been developed at least twice for S. cerevisiae, since Ty3 and Ty1 target tRNA genes at different distances and probably use different protein interactions at the integration sites (24). For D. discoideum, the targeting of tRNA genes has evolved at least three times: the TRE5 non-LTR retrotransposons discussed here integrate ∼48 bp upstream of tRNA genes, while the poorly characterized putative LTR retrotransposon DGLT-A integrates ∼30 bp upstream of D. discoideum tRNA genes (14). TRE3 elements, which are close relatives of TRE5 elements, integrate ca. 100 bp downstream of tRNA genes (14, 41). TRE3s likely target either tRNA gene-internal B boxes or downstream extra B boxes (41), which points to a mechanism of tRNA gene recognition that involves direct interaction of a TRE3-encoded protein and DdTFIIIC.

In gene-dense and haploid genomes like those of S. cerevisiae and D. discoideum, there is a strong selection pressure on mobile elements to avoid devastating insertional mutagenesis. Evolution has put forth convergent mechanisms of tRNA gene targeting that allow target-specific mobile elements to colonize such inhospitable genomes. The striking similarity in target site recognition by diverse retrotransposons such as S. cerevisiae Ty3 and D. discoideum TRE5-A predicts that the Pol III transcription machinery provides exceptionally useful surfaces that allow for the recognition of safe integration sites in compact genomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant WI 1142/5-4 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 October 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST und PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck, P., T. Dingermann, and T. Winckler. 2002. Transfer RNA gene-targeted retrotransposition of Dictyostelium TRE5-A into a chromosomal UMP synthase gene trap. J. Mol. Biol. 318:273-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeke, J. D., and S. E. Devine. 1998. Yeast retrotransposons: finding a nice quiet neighborhood. Cell 93:1087-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chalker, D. L., and S. B. Sandmeyer. 1992. Ty3 integrates within the region of RNA polymerase III transcription initiation. Genes Dev. 6:117-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm, R. L., P. Gaudet, E. M. Just, K. E. Pilcher, P. Fey, S. N. Merchant, and W. A. Kibbe. 2006. dictyBase, the model organism database for Dictyostelium discoideum. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:D423-D427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christensen, S. M., A. Bibillo, and T. H. Eickbush. 2005. Role of Bombyx mori R2 element N-terminal domain in the target-primed reverse transcription (TPRT) reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:6461-6468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connolly, C. M., and S. B. Sandmeyer. 1997. RNA polymerase III interferes with Ty3 integration. FEBS Lett. 405:305-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cost, G. J., Q. Feng, A. Jacquier, and J. D. Boeke. 2002. Human L1 element target-primed reverse transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 21:5899-5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig, N. L., R. Craigie, M. Gellert, and A. M. Lambowitz (ed.). 2002. Mobile DNA II. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 10.DeLano, W. L. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. http://www.pymol.org.

- 11.Eichinger, L., J. A. Pachebat, G. Glöckner, M.-A. Rajandream, R. Sucgang, M. Berriman, J. Song, R. Olsen, K. Szafranski, Q. Xu, B. Tunggal, S. Kummerfeld, M. Madera, B. A. Konfortov, F. Rivero, A. T. Bankier, R. Lehmann, N. Hamlin, R. Davies, P. Gaudet, P. Fey, K. Pilcher, G. Chen, D. Saunders, E. Sodergren, P. Davis, A. Kerhornou, X. Nie, N. Hall, C. Anjard, L. Hemphill, N. Bason, P. Farbrother, B. Desany, E. Just, T. Morio, R. Rost, C. Churcher, J. Cooper, S. Haydock, N. van Driessche, A. Cronin, I. Goodhead, D. Muzny, T. Mourier, A. Pain, M. Lu, D. Harper, R. Lindsay, H. Hauser, K. James, M. Quiles, M. Madan Babu, T. Saito, C. Buchrieser, A. Wardroper, M. Felder, M. Thangavelu, D. Johnson, A. Knights, H. Loulseged, K. Mungall, K. Oliver, C. Price, M. A. Quail, H. Urushihara, J. Hernandez, E. Rabbinowitsch, D. Steffen, M. Sanders, J. Ma, Y. Kohara, S. Sharp, M. Simmonds, S. Spiegler, A. Tivey, S. Sugano, B. White, D. Walker, J. Woodward, T. Winckler, Y. Tanaka, G. Shaulsky, M. Schleicher, G. Weinstock, A. Rosenthal, E. C. Cox, R. L. Chisholm, R. Gibbs, W. F. Loomis, M. Platzer, R. R. Kay, J. Williams, P. H. Dear, A. A. Noegel, B. Barrell, and A. Kuspa. 2005. The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature 435:43-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng, Q. H., J. V. Moran, H. H. Kazazian, and J. D. Boeke. 1996. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell 87:905-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geiduschek, E. P., and G. A. Kassavetis. 2001. The RNA polymerase III transcription apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 310:1-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glöckner, G., K. Szafranski, T. Winckler, T. Dingermann, M. Quail, E. Cox, L. Eichinger, A. A. Noegel, and A. Rosenthal. 2001. The complex repeats of Dictyostelium discoideum. Genome Res. 11:585-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hentschel, U., I. Zündorf, T. Dingermann, and T. Winckler. 2001. On the problem of establishing the subcellular localization of Dictyostelium retrotransposon TRE5-A proteins by biochemical analysis of nuclear extracts. Anal. Biochem. 296:83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohjoh, H., and M. F. Singer. 1996. Cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein complexes containing LINE-1 protein and RNA. EMBO J. 15:630-639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishiguro, A., G. A. Kassavetis, and E. P. Geiduschek. 2002. Essential roles of Bdp1, a subunit of RNA polymerase III initiation factor TFIIIB, in transcription and tRNA processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3264-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juo, Z. S., G. A. Kassavetis, J. Wing, E. P. Geiduschek, and P. B. Sigler. 2003. Crystal structure of a transcription factor IIIB core interface ternary complex. Nature 422:534-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kassavetis, G. A., C. Bardeleben, A. Kumar, E. Ramirez, and E. P. Geiduschek. 1997. Domains of the Brf component of RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB (TFIIIB): functions in assembly of TFIIIB-DNA complexes and recruitment of RNA polymerase to the promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5299-5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kassavetis, G. A., B. Bartholomew, J. A. Blanco, T. E. Johnson, and E. P. Geiduschek. 1991. Two essential components of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factor TFIIIB: transcription and DNA-binding properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:7308-7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassavetis, G. A., R. Driscoll, and E. P. Geiduschek. 2006. Mapping the principle interaction site of the Brf1 and Bdp1 subunits of S. cerevisiae TFIIIB. J. Biol. Chem. 281:14321-14329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kassavetis, G. A., A. Kumar, E. Ramirez, and E. P. Geiduschek. 1998. Functional and structural organization of Brf, the TFIIB-related component of the RNA polymerase III transcription initiation complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:5587-5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kassavetis, G. A., D. L. Riggs, R. Negri, L. H. Nguyen, and E. P. Geiduschek. 1989. Transcription factor IIIB generates extended DNA interactions in RNA polymerase III transcription complexes on tRNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:2551-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, J. M., S. Vanguri, J. D. Boeke, A. Gabriel, and D. F. Voytas. 1998. Transposable elements and genome organization: a comprehensive survey of retrotransposons revealed by the complete Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome sequence. Genome Res. 8:464-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozak, M. 1989. The scanning model for translation: an update. J. Cell Biol. 108:229-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulpa, D. A., and J. V. Moran. 2006. Cis-preferential LINE-1 reverse transcriptase activity in ribonucleoprotein particles. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13:655-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulpa, D. A., and J. V. Moran. 2005. Ribonucleoprotein particle formation is necessary but not sufficient for LINE-1 retrotransposition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14:3237-3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar, A., A. Grove, G. A. Kassavetis, and E. P. Geiduschek. 1998. Transcription factor IIIB: the architecture of its DNA complex, and its role in initiation of transcription by RNA polymerase III. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 63:121-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luan, D. D., M. H. Korman, J. L. Jakubczak, and T. H. Eickbush. 1993. Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell 72:595-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malik, H. S., W. D. Burke, and T. H. Eickbush. 1999. The age and evolution of non-LTR retrotransposable elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:793-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marschalek, R., T. Brechner, E. Amon-Böhm, and T. Dingermann. 1989. Transfer RNA genes: landmarks for integration of mobile genetic elements in Dictyostelium discoideum. Science 244:1493-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marschalek, R., J. Hofmann, G. Schumann, R. Gosseringer, and T. Dingermann. 1992. Structure of DRE, a retrotransposable element which integrates with position specificity upstream of Dictyostelium discoideum tRNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:229-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin, S. L. 1991. Ribonucleoprotein particles with LINE-1 RNA in mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:4804-4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin, S. L., and F. D. Bushman. 2001. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of the ORF1 protein from the mouse LINE-1 retrotransposon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moran, J. V., S. E. Holmes, T. P. Naas, R. J. DeBerardinis, J. D. Boeke, and H. H. Kazazian. 1996. High frequency retrotransposition in cultured mammalian cells. Cell 87:917-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikolov, D. B., H. Chen, E. D. Halay, A. Hoffman, R. G. Roeder, and S. K. Burley. 1996. Crystal structure of a human TATA box-binding protein/TATA element complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:4862-4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandmeyer, S. B. 1998. Targeting retrotransposition: at home in the genome. Genome Res. 8:416-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwede, T., J. Kopp, N. Guew, and M. C. Peitsch. 2003. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3381-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen, Y., G. A. Kassavetis, G. O. Bryant, and A. J. Berk. 1998. Polymerase (Pol) III TATA-binding protein (TBP)-associated factor Brf binds to a surface on TBP also required for activated Pol II transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1692-1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siol, O., M. Boutliliss, G. Glöckner, T. Chung, T. Dingermann, and T. Winckler. 2006. Role of RNA polymerase III transcription factors in the selection of integration sites by the Dictyostelium non-long terminal repeat retrotransposon TRE5-A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:8242-8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szafranski, K., G. Glöckner, T. Dingermann, K. Dannat, A. A. Noegel, L. Eichinger, A. Rosenthal, and T. Winckler. 1999. Non-LTR retrotransposons with unique integration preferences downstream of Dictyostelium discoideum transfer RNA genes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 262:772-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teichmann, M., and K. H. Seifart. 1995. Physical separation of two different forms of human TFIIIB active in the transcription of the U6 or the VAI gene in vitro. EMBO J. 14:5974-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei, W., N. Gilbert, S. L. Ooi, J. F. Lawler, E. M. Ostertag, H. H. Kazazian, J. D. Boeke, and J. V. Moran. 2001. Human L1 retrotransposition: cis preference versus trans complementation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1429-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weser, S., C. Gruber, H. M. Hafner, M. Teichmann, R. G. Roeder, K. H. Seifart, and W. Meissner. 2004. Transcription factor (TF)-like nuclear regulator, the 250-kDa form of Homo sapiens TFIIIB′′, is an essential component of human TFIIIC1 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279:27022-27029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weser, S., J. Riemann, K. H. Seifart, and W. Meissner. 2003. Assembly and isolation of intermediate steps of transcription complexes formed on the human 5S rRNA gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:2408-2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winckler, T., T. Dingermann, and G. Glöckner. 2002. Dictyostelium mobile elements: strategies to amplify in a compact genome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:2097-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winckler, T., K. Szafranski, and G. Glöckner. 2005. Transfer RNA gene-targeted integration: an adaptation of retrotransposable elements to survive in the compact Dictyostelium discoideum genome. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110:288-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yieh, L., H. Hatzis, G. Kassavetis, and S. B. Sandmeyer. 2002. Mutational analysis of the transcroption factor IIIB-DNA target of Ty3 retroelement integration. J. Biol. Chem. 277:25920-25928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yieh, L., G. A. Kassavetis, E. P. Geiduschek, and S. B. Sandmeyer. 2000. The Brf and TATA-binding protein subunits of the RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB mediate position-specific integration of the gypsy-like element Ty3. J. Biol. Chem. 275:29800-29807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]