Abstract

The mobility of the Ty1 retrotransposon in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is restricted by a large collection of proteins that preserve the integrity of the genome during replication. Several of these repressors of Ty1 transposition (Rtt)/genome caretakers are orthologs of mammalian retroviral restriction factors. In rtt/genome caretaker mutants, levels of Ty1 cDNA and mobility are increased; however, the mechanisms underlying Ty1 hypermobility in most rtt mutants are poorly characterized. Here, we show that either or both of two S-phase checkpoint pathways, the replication stress pathway and the DNA damage pathway, partially or strongly stimulate Ty1 mobility in 19 rtt/genome caretaker mutants. In contrast, neither checkpoint pathway is required for Ty1 hypermobility in two rtt mutants that are competent for genome maintenance. In rtt101Δ mutants, hypermobility is stimulated through the DNA damage pathway components Rad9, Rad24, Mec1, Rad53, and Dun1 but not Chk1. We provide evidence that Ty1 cDNA is not the direct target of the DNA damage pathway in rtt101Δ mutants; instead, levels of Ty1 integrase and reverse transcriptase proteins, as well as reverse transcriptase activity, are significantly elevated. We propose that DNA lesions created in the absence of Rtt/genome caretakers trigger S-phase checkpoint pathways to stimulate Ty1 reverse transcriptase activity.

Long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons and retroviral proviruses are related families of mobile DNA elements found dispersed in eukaryotic genomes. Their structures consist of LTRs flanking a central coding domain, including gag and pol genes and, in the case of infectious retroviruses, an env gene (33). The gag gene encodes structural proteins that form the retrotransposon virus-like particle (VLP) or the retroviral core particle, while the pol gene encodes the enzymes necessary for mobility, including protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN). LTR retrotransposons and integrated retroviral proviruses are transcribed by RNA polymerase II to form a terminally redundant RNA, which is translated and also packaged into the virion core particle or VLP, where it functions as a template for RT. IN catalyzes integration of the resulting cDNA into the host cell genome by a homology-independent mechanism. The similarities between LTR retrotransposon transposition and retrovirus replication suggest that these elements are susceptible to common mechanisms of regulation by their host organisms (58).

The genome of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae harbors five families of LTR retrotransposons, named Ty1 to Ty5. Ty1 elements are the most abundant, the most highly expressed, and the most mutagenic (88). Over 30 genes that encode repressors of Ty1 transposition (RTT genes) have been identified, despite the fact that an exhaustive screen has yet to be performed (58). Many of the known RTT gene products function during S phase to maintain the integrity of the yeast genome. For example, the Rtt factor Rad27 is the ortholog of human FEN-1, a 5′-to-3′ exonuclease, 5′ flap endonuclease required for Okazaki fragment processing and maturation during replication (29, 39, 72). The Rrm3 helicase promotes replication through nonnucleosomal protein-DNA complexes, while the cullin Rtt101 is involved in replication through natural and MMS-induced pause sites (38, 55). Mms1/Rtt108 is a constituent of a functional module containing Rtt101 and is important for replication-dependent DNA repair (36, 70). Rtt109 is a histone acetyltransferase that modifies Lys56 on histone H3 and is required for cells to survive DNA damage during S phase (12, 20, 31, 76, 86). Rtt107/Esc4 is a BRCT domain protein implicated in replication restart after DNA damage (11, 73). Elg1/Rtt110 is a replication factor C homolog that is important for recovery from DNA damage during replication (4, 5, 42). Members of the Rad52 and Rad50 epistasis groups are required for recombination-mediated restart of stalled or broken replication forks (34, 69, 83). The roles of these conserved replication- and repair-related factors in the regulation of Ty1 retrotransposons points to a connection between preserving the integrity of the genome during S phase and maintaining the dormancy of Ty1 elements.

The Rtt/genome integrity factors described to date inhibit transposition at posttranscriptional steps, resulting in low levels of Ty1 cDNA (10, 52, 53, 71, 77, 81). Two models, which are not mutually exclusive, have been proposed to explain how Rtt/genome caretakers limit the levels of Ty1 cDNA and retrotransposition. The first model is one in which Rtt/genome caretakers interact directly with Ty1 cDNA in the nucleus to promote its degradation. This model is exemplified by the TFIIH helicases Rad3 and Ssl2 and Rad27, which block Ty1 cDNA accumulation at a step subsequent to reverse transcription (52, 81). However, an important role for cDNA degradation in restricting transposition is difficult to reconcile with the remarkably long half-life of Ty1 cDNA, determined to be between 93 and 252 min (52, 78, 81). A second model posits that Rtt/genome caretakers prevent the formation of DNA lesions that activate a DNA integrity checkpoint pathway that stimulates Ty1 cDNA synthesis. This model was proposed to explain the DNA damage checkpoint pathway-dependent increase in Ty1 cDNA levels in telomerase-negative mutants (78). Because the half-life of Ty1 cDNA in a telomerase-negative strain was equivalent to that in a wild-type strain, it was proposed that the DNA damage pathway stimulates the activity of a Ty1 or Ty1-associated protein, resulting in increased cDNA synthesis.

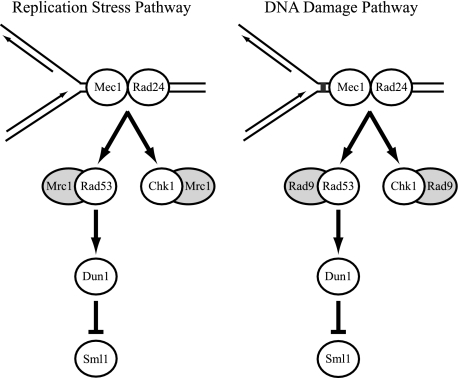

In this study, we ask whether the high levels of Ty1 mobility in rtt mutants that have defects in maintaining genome integrity during replication are triggered by either of two S-phase checkpoint pathways (Fig. 1). The highly integrated S-phase checkpoint pathways are activated by delays in DNA replication (replication stress pathway) or by DNA lesions that obstruct replication (DNA damage pathway) (66). In both pathways, replication blocks are bound independently by a sensor complex containing the essential kinase Mec1 and a second sensor complex, known as the sliding clamp (46, 59). The sliding clamp is loaded onto DNA by a five-subunit clamp loader (56). The clamp loader in the DNA damage pathway consists of RFC2-5 subunits and the replication factor C-like protein Rad24, while Ctf18 and Elg1 play partially redundant roles with Rad24 (4, 5, 42). In the replication stress pathway, Rad24 functions redundantly with Ctf18 (64, 70). Binding of these sensor complexes to DNA at sites of damage or replication pausing promotes the hyperphosphorylation and activation of the Chk kinases Rad53 and Chk1 (74, 75, 79, 80). The activation of Chk kinases also requires the mediator protein Rad9 in the DNA damage pathway or Mrc1 in the replication stress pathway (1, 6, 28, 68, 82, 85). In the absence of Mrc1, Rad9 becomes essential for S-phase checkpoint activity, suggesting that the DNA damage pathway functions as a backup when the replication stress pathway is compromised (1, 43, 66). Both checkpoint pathways block cell cycle progression and initiate a transcriptional and posttranslational response to the DNA lesion (66).

FIG. 1.

The S-phase checkpoint pathways are activated when replication is impeded. Components of each pathway that are relevant to this study are shown. The replication stress and the DNA damage pathways are activated by replication pausing and replication blocks, respectively. The DNA is bound independently by two sensor complexes, represented by the individual components Mec1 and Rad24. Binding of sensor complexes activates the Chk kinases Rad53 and Chk1. The mediator proteins Mrc1 and Rad9 stimulate the activities of the Chk kinases in the replication stress and DNA damage pathways, respectively. Rad53 activates the Dun1 kinase, which has multiple downstream targets, including the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1. The pathways are drawn separately but function in an integrated fashion.

We show below that Ty1 hypermobility in 19 rtt/genome integrity mutants is partially or strongly dependent on the presence of the S-phase checkpoint proteins Rad9 and Rad53 and, in some cases, Rad24. To understand how S-phase checkpoint pathways regulate the mobility of Ty1, we have focused on rtt101Δ mutants, in which the DNA damage checkpoint is activated by defects in replication fork progression (55, 61). Our data indicate that neither Rtt101 nor an effector protein in the DNA damage pathway interacts with Ty1 cDNA to regulate mobility. Instead, the activated DNA damage pathway triggers increases in processed Ty1 IN and RT proteins and in RT activity in Ty1 VLPs. These findings point to a major role for S-phase checkpoint pathways in triggering Ty1 mobility when the integrity of DNA replication is compromised.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Plasmid pGTy1PR-d1his3AI[Δ1], a derivative of pGTy1his3AI[Δ1] (77) in which amino acids 405 to 434 in the Ty1 PR domain are replaced by the peptide sequence GAP (60), was constructed by cloning a 1.5-kb XhoI-BstEII fragment of plasmid pJB1105-d1, kindly provided by J. Boeke, in place of the 1.5-kb XhoI-BstEII fragment in pGTy1his3AI[Δ1].

Plasmid pYES2-3xHA:RTT101 was described previously (47). Derivatives of the URA3-marked 2μ plasmid BG1805, carrying the MMS1, ELG1, RAD27, and RRM3 open reading frames (ORFs) (27), were obtained from Open Biosystems.

S. cerevisiae strains.

The strains used in this study and details of their construction are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. With the exception of the strains used in one experiment, all strains are derivatives of the congenic strains BY4741 and BY4742 (9). Strain JC3212 is a derivative of strain BY4741 containing a chromosomal Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 element. Strain JC3787 also harbors Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 but has the opposite mating type (63). Derivatives of these strains harboring Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 and various gene deletions were made by genetic crossing with yeast ORF deletion strains or by one-step gene replacement. Transformants were tested for loss of the wild-type allele and gain of the mutant allele by PCR. A minimum of three segregants or transformants of each genotype were assayed in a semiquantitative patch test to determine the frequency of Ty1his3AI mobility. One representative segregant or transformant was chosen for quantitative analysis. The oligomer sequences used for one-step gene replacement are available upon request.

To construct strains JC4331, JC4333, JC4335, and JC4337, an rtt101Δ::LEU2 allele was introduced by PCR-mediated gene disruption into the spt3Δ::kanMX derivative of BY4741, obtained from Open Biosystems. Plasmids pGTy1his3AI[Δ1] and pGTy1PR-d1 his3AI[Δ1] were then transformed into the spt3Δ::kanMX and spt3Δ::kanMX rtt101Δ::LEU2 derivatives of BY4741.

In contrast to the strains described above, strain JC4438 is a derivative of strain GRF167 (8). This strain and two congenic derivatives were constructed as follows. A single chromosomal Ty1kanMXAI element was introduced into a trp1::hisG derivative of GRF167 by inducing the expression of a Ty1kanMXAI element fused to the GAL1 promoter on a yeast 2μ vector, as described previously (15). The kanMXAI marker consists of a 104-bp artificial intron (AI) (94) inserted in antisense orientation into the SmaI site in the ORF of kanMX4 (89). The kanMXAI marker was introduced into plasmid pGTy1-H3Cla (26) between the TYB1 ORF and the 3′ LTR in the transcriptional orientation opposite that of Ty1 by gap repair in yeast. Plasmid pGTy2his3AI (16) was introduced into the Ty1kanMXAI-2910 trp1::hisG derivative of strain GRF167. An isolate with one chromosomal Ty2his3AI element was derived following induction of transposition to obtain strain JC4438. Strain JC4389 is an ade2Δ rtt101::ADE2 derivative of JC4438 made by PCR-mediated disruption of ADE2 followed by PCR-mediated disruption of RTT101. JC4639 is an rrm3Δ::URA3 derivative of JC4438 made by PCR-mediated gene disruption.

Ty1his3AI mobility assay.

Strain JC3787 was used as the wild-type strain in each experiment. Each strain was grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) broth at 30°C overnight, diluted 1:1,000 into 3 to 12 cultures of YPD broth, and grown at 20°C for 3 days. For samples that were treated with hydroxyurea (HU), various amounts of a freshly prepared 1 M HU solution were added to the YPD culture at the time of dilution. Aliquots of each culture were plated onto YPD and synthetic complete agar without histidine (SC-His agar) and grown for 3 to 4 days at 30°C. The frequency of Ty1his3AI transposition is the number of His+ prototrophs divided by the number of viable cells in the same culture volume.

The mobilities of Ty1his3AI in strains carrying URA3-marked 2μ-based plasmids were determined as follows. Strains JC3212, JC3890, JC3901, and JC3913 were transformed with the pYES2 vector and pYES2-3xHA:RTT101, BG1805-ELG1, or BG1805-MMS1 plasmid DNA. Four transformants from each transformation were grown in SC-Ura glucose broth overnight at 30°C. Cultures were diluted 1:100 into SC-Ura galactose broth and grown for 2 days at 20°C. An equal volume of YPD was added to each culture, which was grown for 18 h at 20°C. Aliquots of each culture were plated on SC-Ura glucose agar and SC-Ura-His glucose agar to determine the frequencies of Ty1HIS3 mobility events occurring in cells that retained the URA3-based plasmid.

Quantitative analysis of Ty1 RNA and cDNA levels.

Northern blot analysis of Ty1, Ty1his3AI, and PYK1 RNAs was performed as described previously (77). For Ty1 cDNA analysis, independent colonies of each strain were inoculated into 10 ml YPD broth or YPD broth containing various concentrations of HU, and cultures were grown at 20°C for 2 days. Genomic DNA prepared from each culture was digested with SphI, and Ty1 cDNA was quantified as described previously (77).

Ty1kanMXAI and Ty2his3AI mobility assay.

To determine the frequencies of Ty1kanMXAI and Ty2his3AI transposition, YPD cultures of strains JC4438, JC4389, and JC4639 grown overnight at 30°C were each diluted 1:1,000 into four independent YPD cultures and grown for 3 days at 20°C. Aliquots of each culture were plated on YPD agar to determine the total number of cells, YPD agar containing 200 μg/ml G418 to determine the number of G418r cells, and SC-His agar to determine the number of His+ cells.

Gag-green fluorescent protein (GFP) activity assay.

Strain JC3808, in which GFP is fused to gag at nucleotide position +1203 within a single chromosomal Ty1 element (78), was crossed with the rtt101Δ::kanMX derivative of BY4741, and congenic wild-type and rtt101Δ segregants containing Ty1-GFP-3566 were obtained by tetrad dissection. The mean fluorescence intensity per cell was determined for three wild-type and six rtt101Δ segregants as described previously (78).

Purification of Ty1 VLPs.

Ty1 VLPs were isolated from strains JC4331, JC4333, JC4335, and JC4337 by established methods (22, 25), but with the following changes in the galactose induction step. A 400-ml culture of each strain was grown for 24 h at 30°C in SC-Ura with 5% raffinose. Cells were pelleted and used as an inoculum for two 1-liter cultures in SC-Ura with 1.6% galactose and 0.5% raffinose. The cultures were grown at 20°C for 12 h, at which time 15 ml of a galactose-raffinose mixture (16%:5%) was added to boost induction, and the cultures were grown for an additional 18 h at 20°C.

RT assays.

Exogenous and endogenous assays for RT activity associated with Ty1 VLPs were carried out as previously described (24, 95), using [α-32P]dGTP incorporation to monitor cDNA synthesis.

Western blot analysis.

Ty1 proteins were separated on 10% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore). The membranes were hybridized with antibody B2 to detect IN, B8 to detect RT (25), or anti-VLP to detect Ty1 Gag (95). Horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G from donkey (Amersham) was used as a secondary antibody. Visualization of antibody complexes was performed using chemiluminescence.

RESULTS

The hypermobility of Ty1 in rtt/genome integrity mutants is triggered by Rad9.

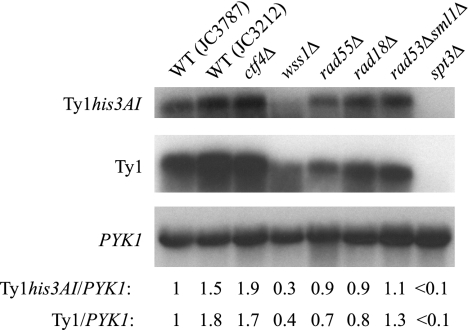

To investigate the hypothesis that S-phase checkpoints activate Ty1 mobility when DNA replication is compromised, we analyzed 19 rtt mutants with roles in maintaining DNA integrity during S phase, including rtt101Δ, rtt107/esc4Δ, mms1/rtt108Δ, rtt109Δ, elg1Δ/rtt110Δ, ctf4Δ, rrm3Δ, wss1Δ, tel1Δ, sae2Δ, rad18Δ, rad27Δ, rad50Δ, xrs2Δ, mre11Δ, rad51Δ, rad52Δ, rad55Δ, and rad57Δ. This set includes four new rtt mutants identified during this study: ctf4Δ, wss1Δ, rad18Δ, and rad55Δ. Ctf4 is a component of the replisome progression complex that links sister chromatid cohesion to DNA synthesis (23, 32). Wss1 interacts genetically with Ctf4 and is thought to play a role in stabilizing stalled or broken replication forks (67). Rad18 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that modifies the replication processivity factor Pol30 to promote translesion synthesis of DNA (35). Rad55 is a recombinational repair protein that stimulates strand exchange in association with Rad57. We originally identified these four rtt strains by screening mutants with S-phase defects for elevated Ty1 cDNA levels and subsequently demonstrated that they have elevated levels of Ty1 mobility (Table 1). As shown previously for other rtt/genome integrity mutants, the absence of Ctf4, Wss1, Rad18, or Rad55 does not cause an increase in Ty1his3AI RNA or total Ty1 RNA, and in fact, both RNAs are decreased ∼3-fold in the wss1Δ mutant (Fig. 2). In addition to these 19 rtt/genome integrity mutants, two rtt mutants, fus3Δ and med1Δ, which have no reported defects in genome maintenance, were analyzed (Table 1). Fus3 is a mitogen-activated protein kinase, while Med1 is a component of the RNA polymerase II transcription mediator complex.

TABLE 1.

Suppression of rtt hypermobility phenotype by rad9Δ

| Genotype of RTT or rtt strain analyzed | Ty1his3AI mobilitya ± SE (10−7)

|

RAD9/rad9Δ ratiob | rttΔ rad9Δ/ RTT rad9Δ ratioc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAD9 | rad9Δ | |||

| RTT | 1.28 ± 0.16 | 0.604 ± 0.091 | 2.1 | NA |

| RTT rad24Δ | 1.41 ± 0.23 | 0.657 ± 0.19 | 2.1 | NA |

| med1Δd | 77.5 ± 7.1 | 56.9 ± 5.3 | 1.4 | 94.2 |

| fus3Δd | 4.72 ± 0.40 | 2.69 ± 0.84 | 1.8 | 4.5 |

| elg1Δe | 135 ± 13 | 33.7 ± 4.9 | 4.0 | 55.8 |

| rtt109Δe | 75.6 ± 16.7 | 20.3 ± 5.4 | 3.7 | 33.6 |

| ctf4Δe | 47.5 ± 9.5 | 6.82 ± 0.61 | 7.0 | 11.3 |

| rrm3Δe | 31.3 ± 4.3 | 4.69 ± 0.84 | 6.7 | 7.8 |

| rtt107Δe | 29.9 ± 5.2 | 4.68 ± 1.92 | 6.4 | 7.7 |

| rad57Δe | 17.1 ± 0.41 | 4.20 ± 0.38 | 4.1 | 7.0 |

| rad27Δe | 13.3 ± 3.5 | 3.48 ± 0.92 | 3.8 | 6.0 |

| wss1Δe | 7.03 ± 1.71 | 2.69 ± 0.75 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| mms1Δe | 55.3 ± 7.1 | 0.625 ± 0.143 | 72.8 | 1.3 |

| rtt101Δe | 54.4 ± 4.2 | 1.07 ± 0.21 | 50.8 | 1.8 |

| rad55Δe | 41.2 ± 5.8 | 2.27 ± 0.48 | 18.2 | 3.8 |

| rad18Δe | 26.9 ± 1.7 | 1.29 ± 0.21 | 20.9 | 2.1 |

| xrs2Δe | 22.9 ± 8.5 | 1.81 ± 0.35 | 12.7 | 3.0 |

| sae2Δe | 22.8 ± 8.0 | 1.16 ± 0.11 | 19.7 | 1.9 |

| rad50Δe | 19.8 ± 2.2 | 1.54 ± 0.55 | 12.9 | 2.6 |

| rad52Δe | 18.7 ± 1.6 | 1.34 ± 0.21 | 14.0 | 2.2 |

| mre11Δe | 12.5 ± 2.1 | 1.64 ± 0.39 | 7.6 | 2.7 |

| rad51Δe | 11.3 ± 0.23 | 2.07 ± 0.38 | 5.5 | 3.4 |

| tel1Δe | 4.57 ± 0.41 | 1.58 ± 0.24 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

Ty1his3AI mobility is the average of the number of His+ prototrophs divided by the total number of cells plated per culture.

The RAD9/rad9Δ ratio is the Ty1his3AI mobility in the RAD9 derivative of each RTT or rtt strain analyzed divided by the average Ty1his3AI mobility in the rad9Δ derivative of the same strain.

The rttΔ rad9Δ/RTT rad9Δ ratio is the Ty1his3AI mobility in the rad9Δ derivative of each rttΔ strain analyzed divided by 0.604 ×10−7, which is the Ty1his3AI mobility in the rad9Δ derivative of the wild-type (RTT) strain. NA, not applicable, because the strain did not harbor an rtt mutation.

rtt control strain with no known effect on genome integrity.

rtt/genome integrity mutant.

FIG. 2.

Ty1 RNA levels are not increased in rtt mutants. Northern blot analysis is shown for total RNA from congenic strains whose relevant genotypes are indicated above each lane. The spt3Δ strain is a negative control. The Northern blot was probed with 32P-riboprobes that hybridize to Ty1his3AI RNA (top), total Ty1 RNA (middle), and PYK1 RNA (bottom), the last as a loading control. Autoradiograms of the blot hybridized to each probe are shown. The ratio of 32P activity in the Ty1his3AI band to 32P activity in the PYK1 band and the ratio of 32P activity in the Ty1 band to 32P activity in the PYK1 band were determined by phosphorimaging. Ty1his3AI/PYK1 and Ty1/PYK1 RNA ratios for each strain, normalized to that for wild-type strain JC3787, are provided below each lane. WT, wild type.

To measure Ty1 mobility in rtt mutants, strains harboring the chromosomal Ty1his3AI-3114 element as well as an rtt ORF deletion were generated by genetic crossing or one-step gene disruption. The his3AI retrotranscript indicator gene consists of the HIS3 gene interrupted by an AI in the antisense orientation. The his3AI gene is inserted in the 3′ untranslated region of a genomic Ty1 element in the opposing transcriptional orientation; consequently, splicing of the AI from the Ty1his3AI RNA and reverse transcription of the spliced transcript generate Ty1 cDNA carrying a functional HIS3 gene (15). When Ty1HIS3 cDNA is inserted into the genome by transposition or recombination with genomic Ty1 sequences, the cell becomes His+. Therefore, the frequency of His+ prototroph formation is a measure of the retromobility of the Ty1his3AI element.

To determine whether the DNA damage checkpoint is required for hypertransposition in rtt mutants, we deleted RAD9 and measured the frequency of His+ prototroph formation in congenic RAD9 and rad9Δ strains (Table 1). Individual rtt mutations conferred 3.6 (tel1Δ)- to 105 (elg1Δ)-fold increases in Ty1his3AI mobility. Deletion of RAD9 reduced Ty1 mobility about twofold in the wild-type RTT strain or the rad24Δ RTT strain, and this deletion had a similar or smaller effect in rtt mutant fus3Δ or med1Δ. Deletion of RAD9 had stronger effects in all 19 rtt/genome integrity mutants tested, which showed 2.6 (wss1Δ)- to 73 (mms1Δ)-fold suppressions of Ty1his3AI mobility. Complete suppression of the hypermobility phenotype was seen only in mms1Δ rad9Δ mutants. Thus, Rad9 is partially or strongly required for the hypertransposition phenotype in rtt/genome caretaker mutants but not in rtt mutants med1Δ and fus3Δ, in which genome integrity is not perturbed. In eight rtt/genome caretaker mutants, Ty1 hypermobility was mainly Rad9 independent (rttΔ RAD9/rttΔ rad9Δ < rttΔ rad9Δ/RTT rad9Δ) (Table 1), while in the other 11 rtt/genome integrity mutants, hypermobility was predominantly dependent on the presence of RAD9 (rttΔ RAD9/rttΔ rad9Δ > rttΔ rad9Δ/RTT rad9Δ) (Table 1).

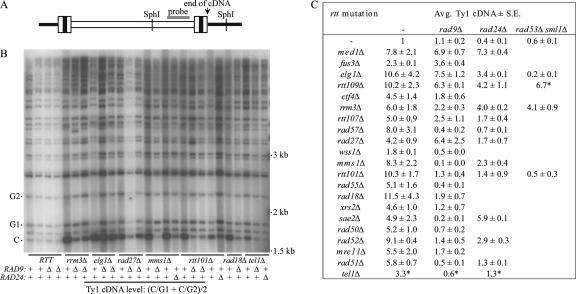

Next, we asked whether rad9Δ suppresses Ty1 hypermobility in rtt/genome integrity mutants by reducing Ty1 cDNA levels (Fig. 3). Deletion of RAD9 did not reduce the level of Ty1 cDNA in a wild-type or fus3Δ strain, and this deletion suppressed Ty1 cDNA only 1.1-fold in a med1Δ mutant. In contrast, rad9Δ suppressed Ty1 cDNA levels 2.5-fold or more in 16 of the 19 of the rtt/genome caretaker mutants. These data suggest that Rad9, and thus the DNA damage checkpoint pathway, is involved in stimulating both Ty1 cDNA levels and hypermobility in the majority of rtt/genome integrity mutants. In elg1Δ, rtt109Δ, and rad27Δ mutants, however, Ty1 cDNA levels were similar or elevated in the absence of Rad9, even though Ty1his3AI mobility was reduced (Table 1). Hence, Rad9 may restrict Ty1 mobility in ways other than altering cDNA levels in a minority of the rtt/genome integrity mutants.

FIG. 3.

High Ty1 cDNA levels are suppressed in the absence of S-phase checkpoint proteins in many rtt/genome integrity mutants. (A) Schematic of a genomic Ty1 element with flanking genomic DNA, denoted by solid black bars. LTRs are indicated by tripartite boxes. A gray rectangle indicates the location of the Ty1 riboprobe used in Southern analysis. The approximate locations of the furthest 3′ SphI site in Ty1 and the next SphI site in genomic DNA 3′ of the Ty1 element are indicated, as is the end of the unintegrated Ty1 cDNA. (B) A representative Southern blot containing SphI-digested genomic DNA hybridized to a 32P-labeled Ty1 riboprobe. Each lane contains genomic DNA from an independent colony grown to a 10-ml saturated culture at 20°C. The 32P activity in the 1.7-kb Ty1 cDNA band (denoted with a C), which extends from the SphI site in Ty1 to the end of the unintegrated cDNA molecule, was quantified by phosphorimaging. Bands from two genomic Ty1 elements (denoted by G1 and G2) were quantified to determine the level of Ty1 cDNA relative to genomic DNA in each sample. The rtt mutation present in each set of strains is indicated below the blot. In addition, the genotypes at the RAD9 and RAD24 loci in each strain are indicated (+, RAD9 or RAD24; Δ, rad9Δ or rad24Δ). (C) Table showing the average Ty1 cDNA level in one to five independent DNA samples of rttΔ, rttΔ rad9Δ, rttΔ rad24Δ, and rttΔ rad53Δ sml1Δ strains relative to the average Ty1 cDNA level in two independent DNA samples of wild-type strain JC3787 run on each Southern blot. The average level of Ty1 cDNA in wild-type strain JC3787 on each Southern blot was assigned a value of 1. Data from the Southern blot shown, and eight additional Southern blots are compiled in the table. The control strains med1Δ and fus3Δ are rtt mutants with no known effect on genome integrity. Asterisks indicate values determined from one DNA sample.

Rad24 is partially required for Ty1 hypermobility in most rtt/genome integrity mutants.

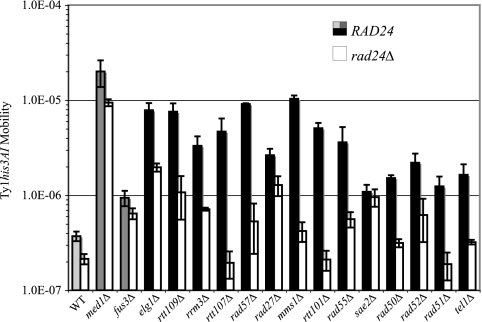

In contrast to Rad9, which functions primarily in the DNA damage pathway, Rad24 is involved in sensing DNA damage in both S-phase checkpoint pathways but is not essential for either. Therefore, we asked whether Ty1 hypermobility is suppressed in a subset of rtt mutants in the absence of Rad24 and, if so, whether the pattern of suppression differs from that for the corresponding rtt rad9Δ mutants. Deletion of RAD24 caused a 1.7-fold decrease in Ty1 mobility in a wild-type strain, and this deletion had a similar effect in a med1Δ or fus3Δ mutant. In contrast, the rad24Δ mutation suppressed hypermobility more than fourfold in 12 of 14 rtt mutants tested (Fig. 4). Complete suppression of hypermobility was observed when RAD24 was deleted in an rtt107Δ mutant, which showed only partial suppression by rad9Δ, and in rtt101Δ and rad51Δ mutants, which displayed strong suppression by rad9Δ. It is likely that Rad24 is required for most of the checkpoint pathway activation of Ty1 hypermobility in these strains, since suppression in an rtt107Δ rad24Δ rad9Δ mutant was equivalent to that in an rtt107Δ mutant (data not shown). On the other hand, the rad24Δ mutation failed to suppress Ty1his3AI hypermobility in a sae2Δ mutant, which was fully suppressed by rad9Δ (Fig. 4, Table 1). Hence, the effect of rad24Δ on Ty1 mobility can differ from that of rad9Δ in some rtt mutants.

FIG. 4.

A rad24Δ mutation suppresses Ty1 hypermobility in most rtt/genome integrity mutants. Ty1his3AI mobility is shown for RAD24 (light gray, dark gray, or black bars) and rad24Δ (white bars) derivatives of a wild-type strain and isogenic rtt derivatives. Light gray bars, RTT strains; dark gray bars, rtt mutants without defects in genome maintenance; black bars, rtt/genome integrity mutants. Error bars; standard error.

Next, we asked whether the rad24Δ mutation reduces the level of Ty1 cDNA in each of 12 rtt/genome integrity mutants (Fig. 3C). Deletion of RAD24 reduced Ty1 cDNA 2.5-fold in the wild-type strain and only slightly in the med1Δ mutant. In the majority of rtt/genome integrity mutants tested, rad24Δ did not reduce Ty1 cDNA levels any further than it did in a wild-type strain. In contrast, Ty1 cDNA was substantially reduced in rtt101Δ, rad57Δ, and rad51Δ mutants when RAD24 was deleted. Thus, in most rtt/genome integrity mutants, Rad24 appears to suppress Ty1 mobility subsequent to the accumulation of cDNA.

The replication stress checkpoint pathway triggers Ty1 hypermobility.

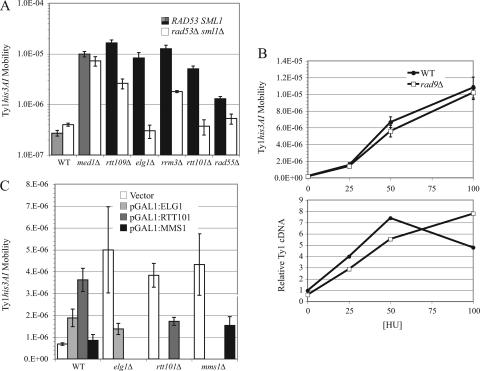

We intended to analyze the epistatic relationship between rtt mutations and the mrc1Δ mutation to determine whether the replication stress pathway, like the DNA damage pathway, triggers Ty1 mobility in rtt/genome integrity mutants. However, unlike all the other S-phase checkpoint mutations analyzed here and in a previous study (78), the mrc1Δ mutation conferred a hypertransposition phenotype on the wild-type strain. The Ty1his3AI mobility frequency was 8.00 × 10−8 ± 1.25 × 10−8 in the wild-type strain and 50.8 × 10−8 ± 9.1 × 10−8 in the isogenic mrc1Δ strain. Since Mrc1 has a role in restarting of stalled replication forks in addition to its role in replication checkpoint signaling (43, 68), stalled replication forks could trigger the DNA damage checkpoint in mrc1Δ mutants, resulting in Ty1 hypermobility. In fact, Ty1 hypermobility was reduced when a plasmid carrying the mrc1AQ allele that is defective for replication checkpoint signaling but competent for replication restart (68) was introduced into the mrc1Δ strain (data not shown). Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint in mrc1Δ mutants complicates the use of this mutation to examine the role of the replication stress checkpoint pathway in triggering Ty1 hypertransposition. Therefore, we determined the effect of deleting RAD53, which is required for the activities of both S-phase checkpoints, in a subset of rtt/genome caretaker mutants. The rad53Δ mutation was introduced subsequent to deletion of SML1, which suppresses the inviability caused by a rad53Δ mutation. Deletion of RAD53 and SML1 had only a minor effect on Ty1his3AI mobility in a wild-type strain or med1Δ mutant (Fig. 5A). In an elg1Δ mutant, Ty1his3AI hypermobility was completely suppressed in the absence of Rad53 and Sml1, even though neither rad9Δ nor rad24Δ caused strong suppression. These results suggest that the replication stress checkpoint pathway activates Ty1 in elg1Δ mutants. Ty1his3AI hypermobility in an rtt101Δ or rad55Δ strain was fully suppressed in the absence of Rad53, as it was in the absence of Rad9, consistent with our conclusion that the DNA damage checkpoint pathway activates Ty1 in these mutants. In rrm3Δ and rtt109Δ mutants, Ty1his3AI mobility was moderately decreased in the absence of Sml1 and Rad53, indicating that Ty1 hypermobility in rrm3Δ and rtt109Δ mutants is partially dependent on the S-phase checkpoints. Comparison of the Ty1 cDNA levels in four of these five rttΔ mutants to those in the corresponding rttΔ rad53Δ sml1Δ mutant fully supports the conclusions reached by Ty1his3AI mobility assays (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 5.

Ty1 is activated through S-phase checkpoint pathways in rtt/genome integrity mutants. (A) Ty1his3AI mobility in RAD53 SML1 (light gray bars, RTT strains; dark gray bars, rtt mutants without defects in genome integrity; black bars, rtt/genome integrity mutants) and rad53Δ sml1Δ (white bars) derivatives of a wild-type strain and congenic rtt mutants. WT, wild type. (B) Ty1his3AI mobility in wild-type and isogenic rad9Δ strains grown in the presence of increasing concentrations of HU. The level of Ty1 cDNA relative to that of genomic Ty1 DNA in two independent DNA samples was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2. (C) Ty1his3AI mobility in a wild-type strain and three mutant rtt strains carrying the pGAL1 vector or one of three pGAL1:RTT gene expression constructs. Ty1his3AI mobility, which is the average of the number of His+ Ura+ prototrophs divided by the number of total Ura+ cells per culture, was determined for each strain. Error bars, standard errors.

To further test the hypothesis that replication stress can induce Ty1 mobility, we measured Ty1his3AI mobility and Ty1 cDNA levels when cells were treated with low levels of HU, which causes nucleotide depletion and replication fork pausing (Fig. 5B). The frequency of Ty1his3AI mobility increased progressively as the concentration of HU was increased from 25 to 100 mM. The level of Ty1 cDNA was also elevated at 25 mM HU and peaked at 50 mM. The lower level of Ty1 cDNA at 100 mM HU may indicate that not only DNA replication but also synthesis of cDNA in VLPs is inhibited at higher HU concentrations. The HU-mediated increases in Ty1 cDNA and mobility do not require Rad9, consistent with activation occurring through the replication stress pathway rather than the DNA damage pathway.

Mec1 and Dun1 are essential for Ty1his3AI hypermobility in rtt101Δ mutants.

To examine how the DNA damage checkpoint pathway induces Ty1 mobility in response to DNA lesions, we focused on the rtt101Δ mutant, in which the DNA damage checkpoint is known to be activated by defects in replication fork progression (55, 61). Elevated levels of Ty1 mobility and cDNA in rtt101Δ mutants are strongly suppressed by rad9Δ, rad24Δ, and rad53Δ sml1Δ mutations (Table 1 and Fig. 3C, 4, and 5A), suggesting that the DNA damage checkpoint pathway specifically induces Ty1 mobility in rtt101Δ mutants. In support of this model, deletion of MEC1 and SML1 also fully suppressed Ty1his3AI mobility in an rtt101Δ mutant, while an sml1Δ mutation alone modestly increased Ty1his3AI mobility in the rtt101Δ mutant (Table 2). Chk1 is phosphorylated by Mec1 and regulates the transition from metaphase to anaphase in the DNA damage checkpoint pathway (74). A chk1Δ mutation had little effect on Ty1his3AI mobility in a wild-type strain and suppressed Ty1his3AI hypermobility in the rtt101Δ mutant only 1.9-fold. Thus, Chk1 does not play a pivotal role in the activation of Ty1 in rtt101Δ mutants. The kinase Dun1 acts downstream of Mec1 and Rad53 to induce expression of damage-inducible genes and degradation of Sml1, an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase (Fig. 1). Deletion of DUN1 or DUN1 and SML1 slightly increased Ty1 mobility in a wild-type strain, but Ty1his3AI mobility in an rtt101Δ mutant was partially suppressed by the dun1Δ mutation and completely suppressed by the dun1Δ sml1Δ mutations (Table 2). Ty1 cDNA levels in an rtt101Δ mutant were also strongly suppressed by either the mec1Δ sml1Δ mutations or the dun1Δ sml1Δ mutations (data not shown). Thus, checkpoint proteins Mec1 and Dun1 are required to mobilize Ty1 elements in rtt101Δ mutants.

TABLE 2.

Effect of checkpoint gene deletions on Ty1his3AI mobility in rtt101Δ mutants

| Relevant genotype | Ty1his3AI mobilitya ± SE (10−7) | Fold difference (relative to wild-type value) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1.69 ± 0.15 | 1 |

| sml1Δ | 4.77 ± 0.87 | 2.8 |

| mec1Δ sml1Δ | 4.55 ± 0.55 | 2.7 |

| chk1Δ | 2.25 ± 0.51 | 1.3 |

| dun1Δ | 1.97 ± 0.64 | 1.2 |

| dun1Δ sml1Δ | 4.63 ± 0.60 | 2.7 |

| rtt101Δ | 54.2 ± 3.9 | 32.1 |

| rtt101Δ sml1Δ | 65.8 ± 19.6 | 38.9 |

| rtt101Δ mec1Δ sml1Δ | 2.15 ± 0.17 | 1.3 |

| rtt101Δ chk1Δ | 28.9 ± 3.4 | 17.1 |

| rtt101Δ dun1Δ | 10.6 ± 0.4 | 6.3 |

| rtt101Δ dun1Δ sml1Δ | 5.51 ± 0.63 | 3.3 |

Ty1his3AI mobility is the average of the number of His+ prototrophs divided by the total number of cells plated per culture.

Overexpression of Rtt101 does not repress Ty1his3AI mobility.

One prediction of the hypothesis that Rtt101 inhibits Ty1 mobility indirectly by suppressing DNA lesions that trigger the DNA damage checkpoint is that overexpression of Rtt101 will not enhance the inhibition of Ty1 transposition. In contrast, overexpression of Rtt101 should enhance the repression of Ty1his3AI mobility if Rtt101 interacts directly with Ty1 cDNA. When RTT101, or ELG1 or MMS1 for comparison, was expressed from the GAL1 promoter on a high-copy-number vector, Ty1his3AI mobility in a wild-type strain increased (Fig. 5C). Thus, overexpression of RTT101, ELG1, or MMS1 failed to enhance the repression of Ty1 mobility conferred by endogenous levels of the same protein. This was not due to lack of pGAL1:RTT expression, since expression of ELG1, RTT101, or MMS1 reduced the hypermobility phenotype of an elg1Δ, rtt101Δ, or mms1Δ mutant, respectively (Fig. 5C). We also attempted to overexpress RAD27 and RRM3, because both have been proposed to interact with Ty1 cDNA (77, 81). However, expression of pGAL1:RAD27 failed to complement the rad27Δ mutation, and strains harboring the pGAL1:RRM3 plasmid did not grow in media containing galactose. Nonetheless, our results are consistent with the conclusion that Rtt101, Mms1, and Elg1 act indirectly to reduce Ty1 cDNA levels.

Mobility of Ty1 but not Ty2 is elevated in rtt101Δ mutants.

Next, we tested the hypothesis that a downstream protein in the DNA damage pathway directly interferes with degradation of Ty1 cDNA by nuclear DNA repair enzymes in the rtt101Δ mutant. If cDNA were the direct target of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway, we would expect the mobilities of elements from different Ty families to be increased in the absence of Rtt101, since cDNA is an intermediate in all retrotransposition events. Therefore, we asked whether the mobilities of both Ty1 and Ty2 elements, which are closely related, are increased in an rtt101Δ mutant. An rtt101Δ mutation was introduced into a strain harboring a genomic Ty1kanMXAI element and a genomic Ty2his3AI element. Ty1kanMXAI mobility was increased 34-fold upon deletion of RTT101, while Ty2his3AI increased only 2-fold (Table 3). In comparison, the difference between the stimulation of Ty1kanMXAI mobility and that of Ty2his3AI mobility was much less significant when RRM3 was deleted (21-fold and 8-fold, respectively). The finding that rtt101Δ preferentially activates the mobility of a Ty1 element argues against a direct role for the DNA damage pathway in preventing degradation of Ty cDNA by DNA repair enzymes.

TABLE 3.

Effect of rtt101Δ and rrm3Δ mutations on Ty1 and Ty2 element mobilitya

| Relevant genotype | Ty1kanMXAI mobilityb ± SE (10−7) | Ty2his3AI mobilityc ± SE (10−7) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 3.79 ± 1.13 (1) | 1.17 ± 0.24 (1) |

| rtt101Δ | 130 ± 25 (34) | 2.09 ± 0.48 (2) |

| rrm3Δ | 79.0 ± 22 (21) | 9.19 ± 0.99 (8) |

Values in parentheses are increases (n-fold) relative to wild-type values.

Ty1kanMXAI mobility is the average of number of G418r colonies divided by the total number of colonies plated per culture.

Ty2his3AI mobility is the average of the number of His+ colonies divided by the total number of colonies plated per culture.

Levels of RT and IN proteins and RT activity are increased in rtt101Δ mutants.

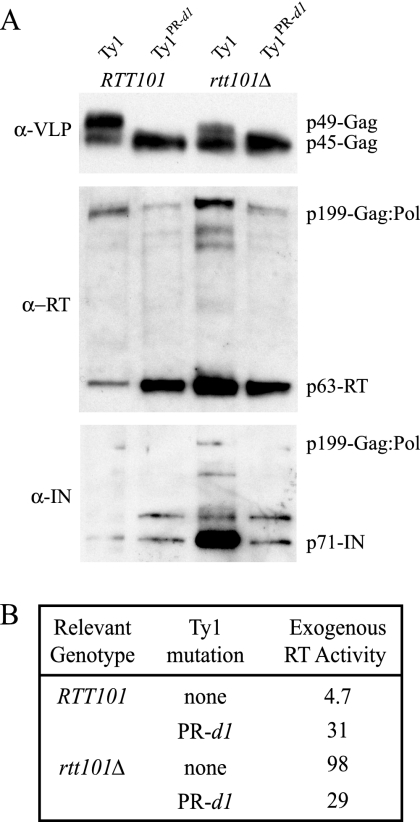

In rtt101Δ mutants, Ty1 cDNA levels and levels of cDNA integration upstream of tRNA genes, which are preferred regions for integration, are elevated, yet Ty1 RNA is not increased (77). Furthermore, we found that deletion of RTT101 did not increase the level of Ty1 Gag-GFP fusion protein produced from the chromosomal Ty1-GFP-3566 element (78). (The mean fluorescence intensity per particle was 5.70 ± 0.02 in RTT101 strains versus 4.44 ± 0.23 in congenic rtt101Δ mutants.) Thus, the elevated level of Ty1 cDNA in an rtt101Δ mutant is not explained by an increase in translation of Ty1 RNA. Therefore, we asked whether the rtt101Δ mutation confers an increase in VLP-associated RT protein or activity levels that could result in increased cDNA levels. The RT protein produced from endogenous Ty1 elements is difficult to detect by Western blotting of whole-cell proteins or sucrose gradient fractions enriched for Ty1 VLPs, particularly in the S288C strain background used in this study (14, 71) (data not shown). To overcome this problem, a Ty1 element was expressed from the GAL1 promoter on a high-copy-number plasmid (pGTy1). In addition, a pGTy1 element containing a 30-amino-acid deletion in the C terminus of Gag and the overlapping N terminus of PR (PR-d1) was expressed (51). Since the N-terminal region of PR is divergent between Ty1 and Ty2 elements, we reasoned that this domain of Ty1 was a possible target of the DNA damage checkpoint in rtt101Δ mutants.

The pGTy1 and pGTy1PR-d1 elements were introduced into RTT101 spt3Δ and rtt101Δ spt3Δ strains. (The spt3Δ mutation blocks transcription of endogenous Ty1 elements but not pGTy1 elements.) Ty1 VLP-enriched sucrose gradient fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-VLP, anti-RT, and anti-IN polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 6A). Anti-VLP antibodies detected both the p49-Gag precursor protein and proteolytic processed p45-Gag in VLP fractions from cells expressing the wild-type Ty1 element. Only one band was detected in VLPs derived from Ty1PR-d1, because the Gag protein encoded by the Ty1PR-d1 gene lacks most of the C terminus of Gag, which is removed by proteolytic processing (51). Total levels of Gag produced from wild-type Ty1 or Ty1PR-d1 were not increased in rtt101Δ mutants, consistent with the result that Rtt101 affects a posttranslational step in transposition. However, there was less p49-Gag precursor and more processed p45-Gag in the rtt101Δ strain expressing wild-type Ty1 than in the RTT101 strain (Fig. 6A, top). Thus, Gag processing may be more efficient in rtt101Δ mutants.

FIG. 6.

Deletion of RTT101 results in increased levels of Ty1 IN and RT proteins and RT activity in VLPs derived from a pGTy1 element but not a pGTy1PR-d1 element. (A) Western blot analysis of VLP-enriched sucrose gradient fractions. (Top) 0.7 μg of each VLP-enriched fraction was probed with anti-VLP (α-VLP) antibody, which recognizes p49-Gag and p45-Gag. (Middle) 2.1 μg of each VLP-enriched fraction was probed with anti-RT antibody, which recognizes the Gag-Pol fusion protein, processing intermediates (not labeled), and RT. (Bottom) 2.1 μg of each VLP-enriched fraction was probed with anti-IN antibody, which recognizes Gag-Pol, processing intermediates (not labeled), and IN. (B) RT activity of VLP fractions from each strain on an exogenously added template. Units are 105 32P counts μg−1 h−1.

In contrast to what was found for Gag proteins, marked increases in the levels of processed Pol proteins RT and IN relative to the levels in the RTT101 strain were observed when wild-type Ty1 was expressed in the rtt101Δ mutant (Fig. 6A, middle and bottom, lanes 1 and 3). The activity of RT on an exogenously added RNA-DNA primer template was also increased 21-fold in the absence of RTT101 (Fig. 6B). In addition, the ratio of total Gag to p199-Gag:Pol is elevated in the rtt101Δ mutant (Fig. 6A, middle, lanes 1 and 3), and this relative increase in Gag-Pol may contribute to the elevated levels of mature RT and IN. Intriguingly, these rtt101Δ-mediated increases in Gag-Pol, RT, and IN were completely blocked when Ty1PR-d1 was expressed. There were moderate increases in both RT protein and exogenous RT activity in VLPs from Ty1PR-d1 relative to the levels in VLPs from wild-type Ty1 in an RTT101 strain (Fig. 6A, middle, lanes 1 and 2, and B); however, the levels of RT, IN, and exogenous RT activity in VLPs from the Ty1PR-d1 element were equivalent in the rtt101Δ and RTT101 strains. These data raise the possibility that the DNA damage checkpoint pathway activated in an rtt101Δ mutant targets the N-terminal domain of PR that is deleted in Ty1PR-d1.

DISCUSSION

A large and diverse group of genome caretakers, particularly proteins that function during replication, have been implicated in the regulation of Ty1 (10, 52, 53, 71, 77, 81). Several Rtt/genome caretakers, including Elg1, Rtt101, Rtt109, Rrm3, and Sgs1, also restrict the mobility of the Ty3 retrotransposon, which is more closely related to mammalian retroviruses than is Ty1 (37). Moreover, human orthologs of several other Rtt/genome caretakers, including Rad3, Ssl2, Rad52, and Rad18, have been found to impede retroviral replication (48, 54, 93). In this study, we tested the hypothesis that transposition is derepressed in the absence of Rtt/genome integrity factors by a common mechanism, i.e., stimulation of Ty1 mobility by S-phase checkpoint pathways. In mammalian systems, some studies have suggested that DNA damage response proteins are required for retroviral integration or for survival of cells after retroviral infection (17, 18, 49, 65), but other studies found no evidence for a contribution of checkpoint proteins to retroviral transduction (2, 19). In yeast, S-phase checkpoint pathways are dispensable for the mobility of Ty1 elements (78), and accordingly, we observed no more than a 2.5-fold decrease in Ty1 retromobility or cDNA levels in rad9, rad24, mec1, rad53, or dun1 mutants (Fig. 3, 4, and 5A and Tables 1 and 2). We have not ruled out the possibility that defects in the S-phase checkpoint pathway alter the ratio of Ty1 cDNA that is integrated into the genome to cDNA that recombines with preexisting Ty1 sequences. Clearly, though, Ty1 cDNA integration can occur in rad9Δ and rad24Δ mutants, since the frequency of Ty1his3AI mobility in a rad9Δ or rad24Δ mutant is not reduced when RAD52, a gene required for Ty1 cDNA recombination, is deleted (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Although S-phase checkpoint proteins are not essential for Ty1 mobility in wild-type cells, they are required to different degrees for the elevated levels of Ty1 cDNA and retrotransposition in all of the 19 rtt/genome integrity mutants tested. In contrast, S-phase checkpoint proteins play no role in the Ty1 hypermobility phenotypes of two rtt mutants without known defects in DNA replication (Table 1 and Fig. 3 and 5A). The various degrees of influence of Rad9, Rad24, and Rad53 on transposition in rtt/genome integrity mutants suggest that the DNA damage pathway, the replication stress pathway, or a combination of the two can activate Ty1 cDNA and mobility. Moreover, the variation is consistent with the diverse roles of Rtt/genome caretakers in the maintenance of genome integrity during S phase, since their absence is likely to result in a variety of DNA lesions.

Various contributions of the replication stress pathway and DNA damage pathway to hypertransposition in rtt/genome caretaker mutants.

Strong suppression of the Ty1 hypermobility phenotype by rad9Δ indicated that hypermobility is triggered primarily through the DNA damage checkpoint pathway in 11 different rtt/genome integrity mutants, including the recombinational repair mutants rad50Δ, mre11Δ, xrs2Δ, rad51Δ, rad52Δ, and rad55Δ (Table 1). Rattray et al. (71) found that recombinational repair proteins block Ty1 transposition at a posttranslational step and suggested that these repair proteins promote degradation of Ty1 cDNA. However, the half-life of Ty1 cDNA in a rad50Δ mutant is equivalent to that in a wild-type strain (78), arguing against the hypothesis that Ty1 cDNA is stabilized in recombinational repair mutants. Studies of human cells using a recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) vector indicate that the human RAD52 protein inhibits HIV-1 integration by binding HIV-1 cDNA and preventing the binding of factors necessary to promote integration (48). The model in which IN and Rad52 compete for binding to retroelement cDNA is not inconsistent with our model in which Rad52 inhibits Ty1 by repressing lesions that activate the DNA damage pathway. Perhaps Ty1 cDNA synthesis is stimulated through the activated DNA damage pathway in rad52Δ mutants, as we have proposed for rtt101Δ mutants, and in addition, the fraction of Ty1 cDNA that is utilized for integration is increased because Rad52 cannot compete with IN for binding Ty1 cDNA. An argument against this hypothesis is that Rattray et al. (71) found no evidence for increased levels of RT protein or activity in rad52Δ and other recombinational repair mutants. However, the DNA damage response is strongly required in both rtt101Δ and rad52Δ mutants, and our data on rtt101Δ mutants suggest that activation of the DNA damage pathway leads to higher levels of Ty1 RT and IN proteins (Fig. 5A). Thus, we suggest that the difference in our results is due to the fact that Rattray et al. (71) quantified the levels of RT protein and activity in endogenous VLPs, whereas we have analyzed VLPs from pGTy1 elements. The yield of VLPs from endogenous Ty1 elements is low, and the purity varies from one preparation to the next (13, 71). Moreover, accurate measurement of RT activity in endogenous VLP preparations is complicated by the low concentrations of RT protein. Therefore, an effect of the rad52Δ mutation on Ty1 proteins may have gone undetected.

In elg1Δ mutants, it is likely that Ty1 hypermobility is triggered primarily through the replication checkpoint pathway, as the elevated Ty1 cDNA and mobility levels were reduced only slightly by a rad9Δ mutation, but they were completely suppressed by a rad53Δ mutation (Table 1 and Fig. 3C and 5A). Consistent with Elg1 acting indirectly to modulate the mobility of Ty1, overexpression of ELG1 failed to enhance repression of Ty1 in a wild-type strain. Elg1 interacts with Rad27 and Pol30 and likely functions at the replication fork, but Elg1 is not required for the replication stress checkpoint (4, 42). Therefore, DNA lesions arising in the absence of Elg1 may activate the replication stress checkpoint, which in turn promotes Ty1 mobility. Further evidence that the replication stress pathway can trigger Ty1 cDNA accumulation and retromobility is provided by the finding that treatment of cells with low levels of HU caused a Rad9-independent increase in Ty1 cDNA and retromobility (Fig. 5B).

Both the DNA damage checkpoint and the replication stress checkpoint could contribute to the hypertransposition phenotype of an rtt107Δ mutant, which was partially suppressed by rad9Δ but strongly suppressed by rad24Δ. In rtt/genome integrity mutants such as rtt109Δ, rrm3Δ, and rad27Δ, S-phase checkpoint pathways appear to play a modest role in stimulating Ty1 mobility. Ty1 mobility and cDNA levels remained partially elevated even when RAD53, which is required for the activities of both pathways, was deleted in rtt109Δ and rrm3Δ mutants (Fig. 5A). Hypertransposition in these mutants could be influenced indirectly by an S-phase checkpoint pathway or be regulated by more than one mechanism. In the rad27Δ mutant, neither the rad9Δ nor the rad24Δ mutation strongly suppressed the elevated Ty1 mobility or cDNA levels. (We have not analyzed a rad27Δ rad53Δ mutant.) A previous study found that Rad27 represses Ty1 retrotransposition at a step subsequent to reverse transcription, consistent with Rad27 interacting directly with Ty1 cDNA (81).

The DNA damage pathway causes increased Ty1 cDNA synthesis by altering the level and activity of Ty1 RT.

Although Ty1 and Ty2 elements are closely related LTR retroelements in yeast (40, 41, 45), both the yeast protein kinase Fus3 and APOBEC3G, a human retroviral restriction factor that interacts with Ty1 Gag when expressed in yeast, have been shown to preferentially repress the activity of Ty1 (13, 21). Remarkably, Rtt101 also represses Ty1 more strongly than Ty2. In contrast, the retromobilities of both Ty1 and Ty2 elements were elevated in rrm3Δ mutants, although a modest preference for stimulation of Ty1 mobility was observed. Our interpretation is that Rrm3 interacts directly with Ty1 and Ty2 cDNA to inhibit mobility or that Ty1 and Ty2 cDNAs are incorporated into the genome at DNA lesions created in the absence of Rrm3. On the other hand, it is unlikely that Rtt101 represses Ty cDNA directly or that an effector protein in the DNA damage signaling pathway prevents degradation of Ty1 cDNA in rtt101Δ mutants. Since Ty1 and Ty2 cDNAs are structurally equivalent molecules, the DNA repair enzymes that recognize the unprotected ends of linear cDNA and cause their degradation are not expected to differentiate between them. The observation that Ty1 mobility is not repressed by overexpression of RTT101 is also inconsistent with a direct interaction between Rtt101 and cDNA. Therefore, we propose that the preferential activation of Ty1 elements in rtt101Δ mutants results from a difference in amino acid sequence between analogous Ty1 and Ty2 proteins, resulting in a difference in their abilities to interact with an effector protein in the DNA damage pathway.

If an effector protein in the DNA damage pathway does not interact directly with Ty1 cDNA, then how does the checkpoint pathway activate Ty1? Hypermobility in an rtt101Δ mutant was fully suppressed by rad9Δ, rad24Δ, rad53Δ sml1Δ, mec1Δ sml1Δ, and dun1Δ sml1Δ mutations. Thus, one possibility is that a Ty1 protein is the target of the Dun1 kinase and that phosphorylation of this protein results in hypermobility. We were unable to identify an amino acid motif in Ty1 Gag or Pol that matched the characterized Dun1 phosphorylation motif in Sml1 (87), and Dun1 is a nuclear protein, while Ty1 VLPs are cytoplasmic. Since Sml1 is not necessary for the rtt101Δ hypertransposition phenotype, Dun1 may work through another downstream effector protein or protein cascade, which in turn interacts directly with Ty1 proteins in the cytoplasm to regulate their activity. Indeed, activation of the S-phase checkpoints can regulate the nuclear export of downstream target proteins such as ribonucleotide reductase subunits Rnr2 and Rnr4 (92).

Analysis of Ty1 VLP proteins in an rtt101Δ mutant indicates that a Ty1 protein(s) could be the target of the activated DNA damage pathway. Processed RT and IN proteins and RT activity in VLP-enriched fractions from cells expressing a pGTy1 element were substantially increased in an rtt101Δ mutant (Fig. 6). The Gag-Pol precursor protein was also modestly elevated. The higher levels of processed Pol proteins are probably due to enhanced protein stability rather than increased translational frameshifting, because conditions that increase frameshifting efficiency are inhibitory to transposition (3, 44, 91). Perhaps modification of Pol proteins or the Gag-Pol protein precursor by an effector protein in the DNA damage pathway results in increased Pol protein stability and processing. In contrast to the results obtained with the pGTy1 element, levels of RT and IN proteins and RT activity in Ty1 VLPs derived from a mutant pGTy1PR-d1 element were not increased by the rtt101Δ mutation. It is possible, therefore, that the 30-amino-acid domain in the N terminus of PR and the C terminus of p49-Gag, which is absent from proteins derived from pGTy1PR-d1 (50), is a target of the DNA damage pathway. Because the 30-amino-acid domain is divergent between Ty1 and Ty2 elements, posttranslational modification of the domain could underlie the preferential mobilization of Ty1 in rtt101Δ mutants. Furthermore, the N-terminal region of PR plays a nucleocapsid-related function in the initiation of reverse transcription (51), so modification of this region could conceivably affect the efficiency of cDNA synthesis. If this domain is modified within Gag-Pol, enhanced processing for forming mature RT and IN might result. Modification of the 30-amino-acid domain in the C terminus of p49-Gag could also enhance the processing of p49-Gag to p45-Gag in the rtt101Δ mutant (Fig. 6A).

It is important to note that although levels of RT and IN proteins derived from a pGTy1 element were substantially elevated in an rtt101Δ mutant, the frequency of pGAL1Ty1his3AI mobility was not increased (data not shown). The latter result was anticipated, since most, if not all, repressors of chromosomal Ty1 elements do not inhibit pGTy1 elements (30). The fact that pGTy1 RT and IN levels, but not mobility, increase in rtt101Δ mutants suggests that transposition of pGTy1 elements is limited at a late step, such as integration.

A role for the S-phase checkpoint pathways in activating transposition provides a common explanation for involvement of diverse genome caretakers in restricting Ty1 mobility. The observation that Ty1 reverse transcription and mobility are activated through S-phase checkpoint pathways supports the hypothesis that Ty1 activity is part of the cellular response to DNA damage (78). Fragments of Ty1 cDNA are captured at sites of DNA breaks in the absence of homologous recombination (62, 84, 96), suggesting a potential role for cDNA in the repair of double-strand breaks. Also, cDNA of the Y′ subtelomeric repeat, synthesized in Ty1 VLPs, is introduced into the genome at high levels in telomerase-negative survivors, where it may play a role in telomere maintenance (57). Ty1 transposition itself, while often inconsequential or deleterious, is also capable of creating adaptively favorable mutations (7, 90). Hence, Ty1 transposition or components of Ty1 VLPs could play functional roles in genome reorganization or cell survival when the genome is compromised.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wadsworth Center Immunology core for flow cytometry and Patrick Maxwell for comments on the manuscript.

Our work is supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM52072 to M.J.C. The work of D.J.G. and S.M. was sponsored by the Center for Cancer Research of the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services.

The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 October 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcasabas, A. A., A. J. Osborn, J. Bachant, F. Hu, P. J. Werler, K. Bousset, K. Furuya, J. F. Diffley, A. M. Carr, and S. J. Elledge. 2001. Mrc1 transduces signals of DNA replication stress to activate Rad53. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:958-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariumi, Y., P. Turelli, M. Masutani, and D. Trono. 2005. DNA damage sensors ATM, ATR, DNA-PKcs, and PARP-1 are dispensable for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integration. J. Virol. 79:2973-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasundaram, D., J. D. Dinman, R. B. Wickner, C. W. Tabor, and H. Tabor. 1994. Spermidine deficiency increases +1 ribosomal frameshifting efficiency and inhibits Ty1 retrotransposition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:172-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellaoui, M., M. Chang, J. Ou, H. Xu, C. Boone, and G. W. Brown. 2003. Elg1 forms an alternative RFC complex important for DNA replication and genome integrity. EMBO J. 22:4304-4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Aroya, S., A. Koren, B. Liefshitz, R. Steinlauf, and M. Kupiec. 2003. ELG1, a yeast gene required for genome stability, forms a complex related to replication factor C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:9906-9911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blankley, R. T., and D. Lydall. 2004. A domain of Rad9 specifically required for activation of Chk1 in budding yeast. J. Cell Sci. 117:601-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeke, J. D., and S. E. Devine. 1998. Yeast retrotransposons: finding a nice quiet neighborhood. Cell 93:1087-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeke, J. D., D. J. Garfinkel, C. A. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 1985. Ty elements transpose through an RNA intermediate. Cell 40:491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brachmann, C. B., A. Davies, G. J. Cost, E. Caputo, J. Li, P. Hieter, and J. D. Boeke. 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14:115-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryk, M., M. Banerjee, D. Conte, Jr., and M. J. Curcio. 2001. The Sgs1 helicase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae inhibits retrotransposition of Ty1 multimeric arrays. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:5374-5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin, J. K., V. I. Bashkirov, W. D. Heyer, and F. E. Romesberg. 2006. Esc4/Rtt107 and the control of recombination during replication. DNA Repair 5:618-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins, S. R., K. M. Miller, N. L. Maas, A. Roguev, J. Fillingham, C. S. Chu, M. Schuldiner, M. Gebbia, J. Recht, M. Shales, H. Ding, H. Xu, J. Han, K. Ingvarsdottir, B. Cheng, B. Andrews, C. Boone, S. L. Berger, P. Hieter, Z. Zhang, G. W. Brown, C. J. Ingles, A. Emili, C. D. Allis, D. P. Toczyski, J. S. Weissman, J. F. Greenblatt, and N. J. Krogan. 2007. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature 446:806-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conte, D., E. Barber, M. Banerjee, D. J. Garfinkel, and M. J. Curcio. 1998. Posttranslational regulation of Ty1 retrotransposition by mitogen-activated protein kinase Fus3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2502-2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curcio, M. J., and D. J. Garfinkel. 1992. Posttranslational control of Ty1 retrotransposition occurs at the level of protein processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:2813-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curcio, M. J., and D. J. Garfinkel. 1991. Single-step selection for Ty1 element retrotransposition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:936-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curcio, M. J., N. J. Sanders, and D. J. Garfinkel. 1988. Transpositional competence and transcription of endogenous Ty elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implications for regulation of transposition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:3571-3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniel, R., G. Kao, K. Taganov, J. G. Greger, O. Favorova, G. Merkel, T. J. Yen, R. A. Katz, and A. M. Skalka. 2003. Evidence that the retroviral DNA integration process triggers an ATR-dependent DNA damage response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4778-4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniel, R., R. A. Katz, G. Merkel, J. C. Hittle, T. J. Yen, and A. M. Skalka. 2001. Wortmannin potentiates integrase-mediated killing of lymphocytes and reduces the efficiency of stable transduction by retroviruses. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1164-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dehart, J. L., J. L. Andersen, E. S. Zimmerman, O. Ardon, D. S. An, J. Blackett, B. Kim, and V. Planelles. 2005. The ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related protein is dispensable for retroviral integration. J. Virol. 79:1389-1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Driscoll, R., A. Hudson, and S. P. Jackson. 2007. Yeast Rtt109 promotes genome stability by acetylating histone H3 on lysine 56. Science 315:649-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutko, J. A., A. Schafer, A. E. Kenny, B. R. Cullen, and M. J. Curcio. 2005. Inhibition of a yeast LTR retrotransposon by human APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases. Curr. Biol. 15:661-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eichinger, D. J., and J. D. Boeke. 1988. The DNA intermediate in yeast Ty1 element transposition copurifies with virus-like particles: cell-free Ty1 transposition. Cell 54:955-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gambus, A., R. C. Jones, A. Sanchez-Diaz, M. Kanemaki, F. van Deursen, R. D. Edmondson, and K. Labib. 2006. GINS maintains association of Cdc45 with MCM in replisome progression complexes at eukaryotic DNA replication forks. Nat. Cell Biol. 8:358-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garfinkel, D. J., J. D. Boeke, and G. R. Fink. 1985. Ty element transposition: reverse transcriptase and virus-like particles. Cell 42:507-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garfinkel, D. J., A. M. Hedge, S. D. Youngren, and T. D. Copeland. 1991. Proteolytic processing of pol-TYB proteins from the yeast retrotransposon Ty1. J. Virol. 65:4573-4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garfinkel, D. J., M. F. Mastrangelo, N. J. Sanders, B. K. Shafer, and J. N. Strathern. 1988. Transposon tagging using Ty elements in yeast. Genetics 120:95-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelperin, D. M., M. A. White, M. L. Wilkinson, Y. Kon, L. A. Kung, K. J. Wise, N. Lopez-Hoyo, L. Jiang, S. Piccirillo, H. Yu, M. Gerstein, M. E. Dumont, E. M. Phizicky, M. Snyder, and E. J. Grayhack. 2005. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the yeast proteome with a movable ORF collection. Genes Dev. 19:2816-2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert, C. S., C. M. Green, and N. F. Lowndes. 2001. Budding yeast Rad9 is an ATP-dependent Rad53 activating machine. Mol. Cell 8:129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene, A. L., J. R. Snipe, D. A. Gordenin, and M. A. Resnick. 1999. Functional analysis of human FEN1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its role in genome stability. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8:2263-2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffith, J. L., L. E. Coleman, A. S. Raymond, S. G. Goodson, W. S. Pittard, C. Tsui, and S. E. Devine. 2003. Functional genomics reveals relationships between the retrovirus-like Ty1 element and its host Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 164:867-879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han, J., H. Zhou, B. Horazdovsky, K. Zhang, R. M. Xu, and Z. Zhang. 2007. Rtt109 acetylates histone H3 lysine 56 and functions in DNA replication. Science 315:653-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanna, J. S., E. S. Kroll, V. Lundblad, and F. A. Spencer. 2001. Saccharomyces cerevisiae CTF18 and CTF4 are required for sister chromatid cohesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3144-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Havecker, E. R., X. Gao, and D. F. Voytas. 2004. The diversity of LTR retrotransposons. Genome Biol. 5:e225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herzberg, K., V. I. Bashkirov, M. Rolfsmeier, E. Haghnazari, W. H. McDonald, S. Anderson, E. V. Bashkirova, J. R. Yates III, and W. D. Heyer. 2006. Phosphorylation of Rad55 on serines 2, 8, and 14 is required for efficient homologous recombination in the recovery of stalled replication forks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:8396-8409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoege, C., B. Pfander, G. L. Moldovan, G. Pyrowolakis, and S. Jentsch. 2002. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 419:135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hryciw, T., M. Tang, T. Fontanie, and W. Xiao. 2002. MMS1 protects against replication-dependent DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:848-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irwin, B., M. Aye, P. Baldi, N. Beliakova-Bethell, H. Cheng, Y. Dou, W. Liou, and S. Sandmeyer. 2005. Retroviruses and yeast retrotransposons use overlapping sets of host genes. Genome Res. 15:641-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivessa, A. S., B. A. Lenzmeier, J. B. Bessler, L. K. Goudsouzian, S. L. Schnakenberg, and V. A. Zakian. 2003. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae helicase Rrm3p facilitates replication past nonhistone protein-DNA complexes. Mol. Cell 12:1525-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin, Y. H., R. Obert, P. M. Burgers, T. A. Kunkel, M. A. Resnick, and D. A. Gordenin. 2001. The 3′->5′ exonuclease of DNA polymerase delta can substitute for the 5′ flap endonuclease Rad27/Fen1 in processing Okazaki fragments and preventing genome instability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5122-5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jordan, I. K., and J. F. McDonald. 1999. Comparative genomics and evolutionary dynamics of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ty elements. Genetica 107:3-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan, I. K., and J. F. McDonald. 1998. Evidence for the role of recombination in the regulatory evolution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ty elements. J. Mol. Evol. 47:14-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanellis, P., R. Agyei, and D. Durocher. 2003. Elg1 forms an alternative PCNA-interacting RFC complex required to maintain genome stability. Curr. Biol. 13:1583-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katou, Y., Y. Kanoh, M. Bando, H. Noguchi, H. Tanaka, T. Ashikari, K. Sugimoto, and K. Shirahige. 2003. S-phase checkpoint proteins Tof1 and Mrc1 form a stable replication-pausing complex. Nature 424:1078-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawakami, K., S. Pande, B. Faiola, D. P. Moore, J. D. Boeke, P. J. Farabaugh, J. N. Strathern, Y. Nakamura, and D. J. Garfinkel. 1993. A rare tRNA-Arg(CCU) that regulates Ty1 element ribosomal frameshifting is essential for Ty1 retrotransposition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 135:309-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim, J. M., S. Vanguri, J. D. Boeke, A. Gabriel, and D. F. Voytas. 1998. Transposable elements and genome organization: a comprehensive survey of retrotransposons revealed by the complete Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome sequence. Genome Res. 8:464-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kondo, T., T. Wakayama, T. Naiki, K. Matsumoto, and K. Sugimoto. 2001. Recruitment of Mec1 and Ddc1 checkpoint proteins to double-strand breaks through distinct mechanisms. Science 294:867-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laplaza, J. M., M. Bostick, D. T. Scholes, M. J. Curcio, and J. Callis. 2004. Saccharomyces cerevisiae ubiquitin-like protein Rub1 conjugates to cullin proteins Rtt101 and Cul3 in vivo. Biochem. J. 377:459-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lau, A., R. Kanaar, S. P. Jackson, and M. J. O'Connor. 2004. Suppression of retroviral infection by the RAD52 DNA repair protein. EMBO J. 23:3421-3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lau, A., K. M. Swinbank, P. S. Ahmed, D. L. Taylor, S. P. Jackson, G. C. Smith, and M. J. O'Connor. 2005. Suppression of HIV-1 infection by a small molecule inhibitor of the ATM kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:493-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lawler, J. F., Jr., G. V. Merkulov, and J. D. Boeke. 2001. Frameshift signal transplantation and the unambiguous analysis of mutations in the yeast retrotransposon Ty1 Gag-Pol overlap region. J. Virol. 75:6769-6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawler, J. F., Jr., G. V. Merkulov, and J. D. Boeke. 2002. A nucleocapsid functionality contained within the amino terminus of the Ty1 protease that is distinct and separable from proteolytic activity. J. Virol. 76:346-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee, B. S., L. Bi, D. J. Garfinkel, and A. M. Bailis. 2000. Nucleotide excision repair/TFIIH helicases RAD3 and SSL2 inhibit short-sequence recombination and Ty1 retrotransposition by similar mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2436-2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee, B. S., C. P. Lichtenstein, B. Faiola, L. A. Rinckel, W. Wysock, M. J. Curcio, and D. J. Garfinkel. 1998. Posttranslational inhibition of Ty1 retrotransposition by nucleotide excision repair transcription factor TFIIH subunits Ss12p and Rad3p. Genetics 148:1743-1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lloyd, A. G., S. Tateishi, P. D. Bieniasz, M. A. Muesing, M. Yamaizumi, and L. C. Mulder. 2006. Effect of DNA repair protein Rad18 on viral infection. PLoS Pathog. 2:e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luke, B., G. Versini, M. Jaquenoud, I. W. Zaidi, T. Kurz, L. Pintard, P. Pasero, and M. Peter. 2006. The cullin Rtt101p promotes replication fork progression through damaged DNA and natural pause sites. Curr. Biol. 16:786-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Majka, J., and P. M. Burgers. 2003. Yeast Rad17/Mec3/Ddc1: a sliding clamp for the DNA damage checkpoint. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:2249-2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maxwell, P. H., C. Coombes, A. E. Kenny, J. F. Lawler, J. D. Boeke, and M. J. Curcio. 2004. Ty1 mobilizes subtelomeric Y′ elements in telomerase-negative Saccharomyces cerevisiae survivors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:9887-9898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maxwell, P. H., and M. J. Curcio. 2007. Host factors that control long terminal repeat retrotransposons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: implications for the regulation of mammalian retroviruses. Eukaryot. Cell. 6:1069-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Melo, J. A., J. Cohen, and D. P. Toczyski. 2001. Two checkpoint complexes are independently recruited to sites of DNA damage in vivo. Genes Dev. 15:2809-2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merkulov, G. V., K. M. Swiderek, C. B. Brachmann, and J. D. Boeke. 1996. A critical proteolytic cleavage site near the C terminus of the yeast retrotransposon Ty1 Gag protein. J. Virol. 70:5548-5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michel, J. J., J. F. McCarville, and Y. Xiong. 2003. A role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cul8 ubiquitin ligase in proper anaphase progression. J. Biol. Chem. 278:22828-22837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moore, J. K., and J. E. Haber. 1996. Capture of retrotransposon DNA at the sites of chromosomal double-strand breaks. Nature 383:644-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mou, Z., A. E. Kenny, and M. J. Curcio. 2006. Hos2 and Set3 promote integration of Ty1 retrotransposons at tRNA genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 172:2157-2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naiki, T., T. Kondo, D. Nakada, K. Matsumoto, and K. Sugimoto. 2001. Chl12 (Ctf18) forms a novel replication factor C-related complex and functions redundantly with Rad24 in the DNA replication checkpoint pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:5838-5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nunnari, G., E. Argyris, J. Fang, K. E. Mehlman, R. J. Pomerantz, and R. Daniel. 2005. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by caffeine and caffeine-related methylxanthines. Virology 335:177-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nyberg, K. A., R. J. Michelson, C. W. Putnam, and T. A. Weinert. 2002. Toward maintaining the genome: DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36:617-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O'Neill, B. M., D. Hanway, E. A. Winzeler, and F. E. Romesberg. 2004. Coordinated functions of WSS1, PSY2 and TOF1 in the DNA damage response. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:6519-6530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Osborn, A. J., and S. J. Elledge. 2003. Mrc1 is a replication fork component whose phosphorylation in response to DNA replication stress activates Rad53. Genes Dev. 17:1755-1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Osborn, A. J., S. J. Elledge, and L. Zou. 2002. Checking on the fork: the DNA-replication stress-response pathway. Trends Cell. Biol. 12:509-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pan, X., P. Ye, D. S. Yuan, X. Wang, J. S. Bader, and J. D. Boeke. 2006. A DNA integrity network in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 124:1069-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rattray, A. J., B. K. Shafer, and D. J. Garfinkel. 2000. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA recombination and repair functions of the RAD52 epistasis group inhibit Ty1 transposition. Genetics 154:543-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reagan, M. S., C. Pittenger, W. Siede, and E. C. Friedberg. 1995. Characterization of a mutant strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a deletion of the RAD27 gene, a structural homolog of the RAD2 nucleotide excision repair gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:364-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rouse, J. 2004. Esc4p, a new target of Mec1p (ATR), promotes resumption of DNA synthesis after DNA damage. EMBO J. 23:1188-1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanchez, Y., J. Bachant, H. Wang, F. Hu, D. Liu, M. Tetzlaff, and S. J. Elledge. 1999. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by chk1 and rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science 286:1166-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sanchez, Y., B. A. Desany, W. J. Jones, Q. Liu, B. Wang, and S. J. Elledge. 1996. Regulation of RAD53 by the ATM-like kinases MEC1 and TEL1 in yeast cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Science 271:357-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schneider, J., P. Bajwa, F. C. Johnson, S. R. Bhaumik, and A. Shilatifard. 2006. Rtt109 is required for proper H3-K56 acetylation: a chromatin mark associated with the elongating RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 281:37270-37274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scholes, D. T., M. Banerjee, B. Bowen, and M. J. Curcio. 2001. Multiple regulators of Ty1 transposition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have conserved roles in genome maintenance. Genetics 159:1449-1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scholes, D. T., A. E. Kenny, E. R. Gamache, Z. Mou, and M. J. Curcio. 2003. Activation of a LTR-retrotransposon by telomere erosion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15736-15741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun, Z., D. S. Fay, F. Marini, M. Foiani, and D. F. Stern. 1996. Spk1/Rad53 is regulated by Mec1-dependent protein phosphorylation in DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways. Genes Dev. 10:395-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sun, Z., J. Hsiao, D. S. Fay, and D. F. Stern. 1998. Rad53 FHA domain associated with phosphorylated Rad9 in the DNA damage checkpoint. Science 281:272-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sundararajan, A., B. S. Lee, and D. J. Garfinkel. 2003. The Rad27 (Fen-1) nuclease inhibits Ty1 mobility in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 163:55-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sweeney, F. D., F. Yang, A. Chi, J. Shabanowitz, D. F. Hunt, and D. Durocher. 2005. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 acts as a Mec1 adaptor to allow Rad53 activation. Curr. Biol. 15:1364-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Symington, L. S. 2002. Role of RAD52 epistasis group genes in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:630-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Teng, S. C., B. Kim, and A. Gabriel. 1996. Retrotransposon reverse-transcriptase-mediated repair of chromosomal breaks. Nature 383:641-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Toh, G. W., and N. F. Lowndes. 2003. Role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 protein in sensing and responding to DNA damage. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:242-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]