Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Abnormalities in retinal haemodynamics have been reported in patients with type 1 diabetes in advance of clinical retinopathy. These abnormalities could therefore be useful as early markers or surrogate endpoints for studying the microangiopathy. Since the DCCT, the increased focus on good glycaemic control is changing the natural history of diabetic retinopathy. Based on this, the aim of this study was to investigate whether patients with type 1 diabetes treated entirely or mostly in the post-DCCT era and tested in the absence of confounding factors show retinal haemodynamic abnormalities.

Methods

We measured retinal haemodynamics by laser Doppler flowmetry in 33 type 1 diabetic individuals with no or minimal retinopathy (age 30 ± 7 years, duration of diabetes 8.8 ± 4.6 years, 9% showing microaneurysms), and 31 age- and sex-matched non-diabetic controls. The study participants were not taking vasoactive medications, and blood glucose at the time of haemodynamic measurements was required to be between 3.8 and 11.1 mmol/l.

Results

HbA1c was 7.5 ± 1.2% and blood glucose 7.7 ± 2.8 mmol/l in these type 1 diabetic individuals, indicating relatively good glycaemic control. Retinal blood speed, arterial diameter and blood flow were not different between the diabetic individuals and the matched controls.

Conclusions/interpretation

Type 1 diabetic patients with no or minimal retinopathy who maintain relatively good glycaemic control do not show abnormalities of the retinal circulation at steady state, even after several years of diabetes. In such patients it may be necessary to test the vascular response to challenges to uncover any subtle abnormalities of the retinal vessels.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, Retinal blood flow, Retinal circulation, Type 1 diabetes

The DCCT proved that good glycaemic control is a powerful means of preventing retinopathy or slowing its course in many patients [1]. It also proved that today’s means of achieving good control are imperfect, and that some patients may still progress to sight-threatening stages of retinopathy. With the latter finding, the DCCT encouraged continuation of the quest for therapies able to pre-empt the effects of the residual hyperglycaemia; however, by increasing the prevalence of good glycaemic control it made any trial of such therapies extremely long and expensive. For this reason, there is heightened interest in early markers of retinopathy to be used as surrogates to test adjunct therapies.

Retinal haemodynamics have been investigated extensively in the quest for early functional markers of diabetic retinopathy [2]; some of the changes detected appear to be a function of the duration of diabetes and the severity of retinopathy [2–4]. In patients with type 1 diabetes and absent or minimal retinopathy, several investigators using different techniques have observed decreased retinal blood speed [3–7]. These studies, performed in the early and mid-1990s, were in patients with rather poor glycaemic control by today’s standards, yet the decreased retinal blood speed could not be attributed solely to elevated blood glucose levels at the time of measurement because hyperglycaemia actually increases blood speed [2, 3, 7]. We investigated whether patients with type 1 diabetes treated entirely or mostly in the post-DCCT era and tested in the absence of confounding factors show retinal haemodynamic abnormalities.

Methods

The institutional review boards of the Schepens Eye Research Institute and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) approved this study. We recruited, from the MGH Diabetes Center and the greater Boston area, type 1 diabetic patients with the clinical characteristics of patients previously reported [3–7] to show decreased retinal blood speed: 18–45 years of age, 1–15 years of insulin dependence, and absent or minimal retinopathy. The non-diabetic participants, matched for age and sex, had no history of diabetes and had HbA1c levels lower than 6%. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, smoking, systemic diseases other than type 1 diabetes, other retinal diseases, hypertension and renal insufficiency; also excluded were users of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor antagonists, vitamin E at doses greater than 400 IU/day, aspirin or other antiplatelet drugs, and ibuprofen. After giving informed consent, all participants in the study underwent a complete eye examination. Diabetic individuals were excluded if they had diabetic retinopathy greater than level 20 in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study severity scale (microaneurysms only). HbA1c was measured by the MGH HbA1c laboratory; a level >10% was an exclusion criterion.

The retinal haemodynamic parameters were measured when capillary blood glucose levels were between 3.8 and 11.1 mmol/l in order to avoid the confounding effects of acute hypo- or hyperglycaemia on retinal blood flow [7]. The investigator performing the laser Doppler measurements (G. T. Feke) was masked to the diabetes status of the participants. The study eye was chosen on the basis of vascular anatomy. The superior temporal retinal arteries are preferred because temporal arteries are larger than nasal arteries, and the lesions of diabetic retinopathy are more prevalent in the superior temporal than in the other quadrants. The arterial blood column diameter and centreline blood speed were measured using a Canon laser Doppler retinal blood flow instrument (CLBF 100; Canon, Tokyo, Japan) [8]. The blood flow rate in units of μl/min is calculated automatically as the product of the cross-sectional area of the artery at the laser Doppler measurement site and the average blood speed, assuming a circular arterial cross-section [8].

Data are presented as means±SD. Parameters were compared between diabetic and control participants using the non-paired t test.

Results

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the study population. The diabetic and control groups differed only in the levels of HbA1c and blood glucose. The diabetic participants received insulin through multiple daily injections or an external pump. The mean HbA1c level was 7.5% and the range 5.2–9.3%, eight patients having HbA1c levels above 8%. The mean duration of type 1 diabetes was 8.8 years. Only three patients manifested retinopathy, two of them showing one microaneurysm and one several microaneurysms. Of note, no diabetic individual who sought participation in the study was excluded because of advanced retinopathy, and only one diabetic individual was not included because of HbA1c greater than 10% (10.8%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Diabetic individuals (n = 33) | Controls (n = 31) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30 ± 7.0 | 30 ± 5.6 | 0.86 |

| Sex (% female) | 48 | 58 | 0.44 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 8.8 ± 4.6 | n/a | n/a |

| Blood glucose level (mmol/l)a | 7.7 ± 2.8 | 5.4 ± 0.8 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 106 ± 11 | 109 ± 7 | 0.27 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 65 ± 8 | 66 ± 7 | 0.47 |

| Retinopathyb (%) | 9 | n/a |

Data are means±SD or percentages

aMeasured immediately before the retinal haemodynamic studies

bAssessed using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study severity scale. Individuals with a score of greater than 20 were excluded from the study

n/a, not applicable

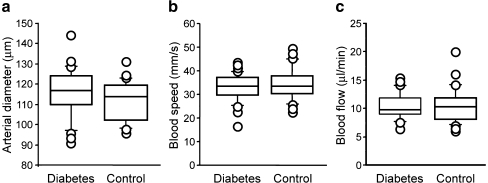

Figure 1 presents the retinal haemodynamic measurements in 27 diabetic and 26 control participants in whom the measurements could be performed at the major superior temporal artery. Arterial diameter and blood speed were not significantly different between the diabetic patients and the controls (diameter: patients 116 ± 12 μm, controls 112 ± 10 μm, p = 0.18; blood speed: patients 32.9 ± 6.0 mm/s, controls 34.6 ± 6.8 mm/s, p = 0.34). Accordingly, retinal blood flow was the same in the two groups (patients 10.4 ± 2.4 μl/min; controls 10.4 ± 3.2 μl/min, p = 0.98). In the remaining six diabetic and five control participants there was early bifurcation of the artery, and one of the branches was used for the measurements; again, no differences were noted between the two groups. The sample size provided 80% power (α = 0.05) to detect differences as low as 0.75 SD between diabetic and control participants. This translates into differences of 7, 15 and 24% for retinal artery diameter, blood speed and blood flow, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Retinal haemodynamic parameters in type 1 diabetic individuals and matched non-diabetic controls. The box plots present the data for the 27 diabetic and 26 control participants in whom the measurements could be performed at the major superior temporal artery. Each box plot shows the 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th and 90th percentiles of the indicated parameter. Values above the 90th and below the 10th percentile are plotted as points

None of the haemodynamic measurements showed a significant correlation with coincident blood glucose levels, HbA1c, age, diabetes duration, systolic or diastolic blood pressure in either the diabetic or the control participants (data not shown).

Discussion

The important finding of this study is that in young patients with relatively well-controlled type 1 diabetes and no complications the baseline retinal circulatory parameters are within the normal range, even after several years of diabetes. These results differ from those of studies completed before the publication and widespread application of the DCCT results. In these earlier studies [3–7] the average HbA1c levels were 8, 10 or 12% compared with 7.5% in our diabetic individuals. Although we did not observe a correlation of HbA1c with retinal blood speed or flow, most likely because of the narrow range of HbA1c values, it was previously shown that retinal blood flow decreased with increasing HbA1c in type 1 diabetic patients without retinopathy [4].

The relation between HbA1c and retinal circulatory parameters must be interpreted with the knowledge that acute elevations [2, 7] or coincident high levels [2, 3] of blood glucose increase retinal blood flow, by increasing blood speed. Thus, the decreased blood speed and blood flow found in type 1 patients in previous studies indicated the presence of chronic effects of hyperglycaemia on retinal vessels in advance of clinical retinopathy. Elevated plasma glucose levels at the time of haemodynamic measurements could actually have masked, to some extent, such chronic effects of hyperglycaemia, contributing to the inconsistency with which retinal circulatory abnormalities were detected in diabetic patients without retinopathy [2]. The design of our study, requiring relatively normal glucose levels prior to the laser Doppler measurements (Table 1), limited such potential confounding effects, and the normal retinal haemodynamics that we recorded in diabetic participants should be informative of the status of retinal vessels.

Our results are empowering for patients with type 1 diabetes and those who care for them, for two reasons. First, it is apparent that good glycaemic control is attainable in a non-clinical trial setting, and is sustainable over time. Second, such good control not only delays or prevents retinopathy, as shown by the DCCT, but also delays or prevents abnormalities in the retinal circulation that may be prodromes to the development of retinopathy. Normal retinal haemodynamics were also reported recently in patients with type 2 diabetes with no retinopathy and mean HbA1c of 7.2% [9] or 7.7% [2].

From the standpoint of finding early markers of retinopathy, our observations indicate that measurements of retinal circulatory parameters in the unperturbed state may not be sufficiently sensitive in patients with absent or minimal retinopathy and well-controlled diabetes. Insofar as the HbA1c levels in such patients are often still greater than normal, the residual hyperglycaemia is likely to leave signs on the retinal vessels, but these may be uncovered only when a functional challenge is applied to the vessels. In response to hyperoxia, used as a stimulus to test vascular reactivity, patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes showed normal retinal haemodynamics [9], but type 1 patients in another study did not [10]. Unfortunately, the latter study did not report levels of glycaemic control. The next step will be to compare in the same well-controlled type 1 diabetic individuals the behaviour of retinal haemodynamics at steady state and in response to a challenge. In this way we will begin to reconstruct systematically the history of retinal microangiopathy in the post-DCCT era.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by Public Health Service grant EY014812 to M. Lorenzi, funded through the Special Statutory Funding Program for Type 1 Diabetes Research, and by the Massachusetts Lions Research Fund. D. M. Nathan is supported in part by the Ida S. Charlton Charity Fund.

Duality of interest The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

References

- 1.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1993) The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329:977–986 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Guan K, Hudson C, Wong T et al (2006) Retinal hemodynamics in early macular edema. Diabetes 55:813–818 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Feke GT, Buzney SM, Ogasawara H et al (1994) Retinal circulatory abnormalities in type 1 diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 35:2968–2975 [PubMed]

- 4.Clermont AC, Aiello LP, Mori F, Aiello LM, Bursell S-E (1997) Vascular endothelial growth factor and severity of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy mediate retinal hemodynamics in vivo: a potential role for vascular endothelial growth factor in the progression of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 124:433–446 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Wolf S, Arend O, Toonen H, Bertram B, Jung F, Reim M (1991) Retinal capillary blood flow measurement with a scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Ophthalmology 98:996–1000 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kawagishi T, Nishizawa Y, Emoto M et al (1995) Impaired retinal artery blood flow in IDDM patients before clinical manifestations of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 18:1544–1549 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bursell S-E, Clermont AC, Kinsley BT, Simonson DC, Aiello LM, Wolpert HA (1996) Retinal blood flow changes in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and no diabetic retinopathy. A video fluorescein angiography study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37:886–897 [PubMed]

- 8.Yoshida A, Feke GT, Mori F et al (2003) Reproducibility and clinical application of a newly developed stabilized retinal laser Doppler instrument. Am J Ophthalmol 135:356–361 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Gilmore ED, Hudson C, Nrusimhadevara RK et al (2007) Retinal arteriolar diameter, blood velocity, and blood flow response to an isocapnic hyperoxic provocation in early sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48:1744–1750 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Trick GL, Edwards P, Desai U, Berkowitz BA (2006) Early supernormal retinal oxygenation response in patients with diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47:1612–1619 [DOI] [PubMed]