Abstract

Takayasu's arteritis with coronary artery involvement is rare, and there is little published information on the subject. Coronary angiographic and histopathologic studies have revealed coronary artery lesions in 9% to 11% of cases. Coronary artery involvement consists mostly of stenosis or occlusion of the coronary ostia.

We report the case of a 19-year-old woman who presented with crescendo angina. Upon investigation, we found that our patient had ostial and left main coronary arterial stenosis with left-dominant circulation; therefore, we decided that an arterial Y graft, performed on a beating heart, would provide better perfusion to the compromised myocardium than would a single graft to the left anterior descending artery. In addition, use of the Y graft obviated the need to perform a proximal anastomosis on an inflamed, edematous ascending aorta, and it conferred long-term graft patency of the internal mammary arteries.

Timely coronary artery bypass grafting relieved our patient's angina, and in early follow-up she has shown good effort tolerance.

Key words: Angina pectoris/etiology/surgery, aorta/pathology, arteritis/complications, coronary angiography, coronary artery bypass, coronary disease/diagnosis/etiology/pathology, coronary stenosis/complications/surgery, coronary vessels/pathology, internal mammary-coronary artery anastomosis/methods, Takayasu's arteritis/classification/complications/pathology/radiography/therapy, treatment outcome

Takayasu's arteritis is associated with a low incidence of coronary arterial involvement (9%–11% of cases). Such involvement presents in the form of stenosis, complete obstruction, aneurysm, or coronary steal syndrome.

We report the case of a young woman who had Takayasu's arteritis with total occlusion of the left main coronary ostium and severe narrowing of the left main coronary artery, and unstable angina. We review the medical literature and discuss medical and surgical options, choices of grafts, and methods of revascularization.

Case Report

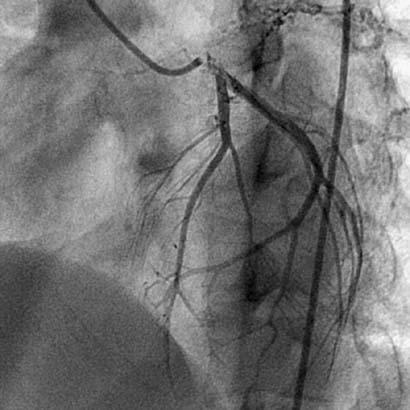

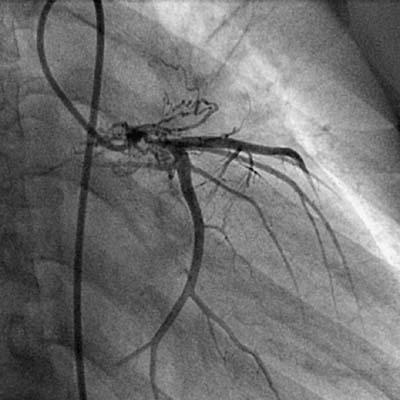

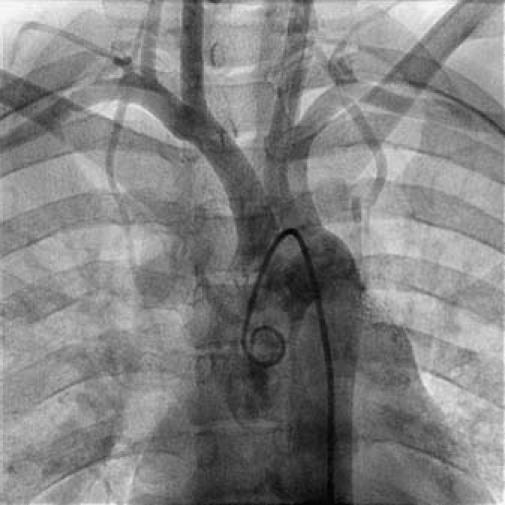

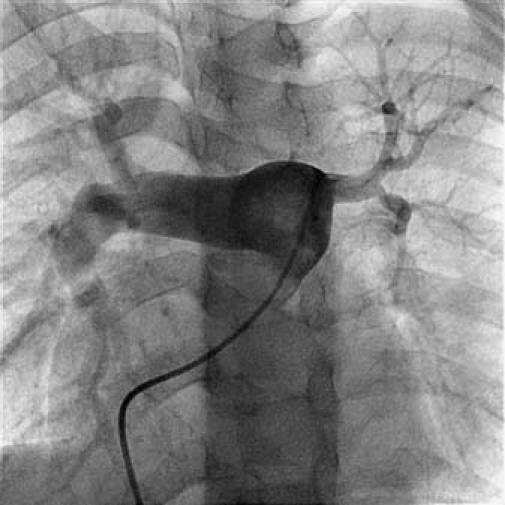

In December 2005, a 19-year-old woman presented at King Edward Memorial Hospital with retrosternal chest pain that had radiated to the left arm on exertion for 2 months. Resting had relieved the pain. During the past 15 days, however, her pain had increased in intensity and duration; it was occurring during rest and was accompanied by profuse sweating. Her electrocardiogram showed ST-segment depression in the inferolateral leads. She was admitted to intensive care and was started on aspirin, clopidogrel, and intravenous nitroglycerin. She was not diabetic or hypertensive, and she neither drank alcohol nor smoked. She had no history of cerebrovascular accidents or peripheral vascular disease, and there was no family history of coronary artery disease. Physical examination with the patient in the supine position revealed a pulse of 80 beats/min and blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg in the right arm. All peripheral pulses were well felt. No bruit was heard anywhere, and heart sounds were normal on auscultation. On the day of admission, the patient's C-reactive protein level (97.58 mg/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (56 mm/hr) were high; however, the results of routine hematologic and biochemical investigations were normal. Her lipid, lipoprotein A, and plasma homocysteine levels were normal. A VDRL test was nonreactive. The IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibody, antinuclear factor, anti-double-strand DNA, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, and cryoglobin results were all negative. The human leukocyte antigen haplotypes A2, A24, B27, Bw4, Cw7, DR14, DR15, DQ1, DRw51, and DRw52 were identified. Two-dimensional echocardiography revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 0.60 and no regional wall motion abnormalities. Coronary angiography showed total occlusion of the left main coronary ostium and severe narrowing of the left main coronary artery. Collateral vessels from the aortic root were partially refilling the left main coronary artery (LMCA), distal to the occlusion, with TIMI 3 antegrade flow (Fig. 1). In contrast, the left anterior descending (LAD), circumflex (Fig. 2), and right coronary arteries were normal. An aortogram showed normal arch vessels (Fig. 3) and normal bilateral renal arteries. A pulmonary angiogram showed diffuse stenosis of the left pulmonary artery (Fig. 4) with a gradient of approximately 10 mmHg, which was hemodynamically insignificant; therefore, no intervention was performed.

Fig. 1 Coronary angiogram shows left main ostial stenosis.

Fig. 2 Coronary angiogram shows normal ostia of the left anterior descending, circumflex, and obtuse marginal arteries.

Fig. 3 Aortogram shows normal arch vessels.

Fig. 4 Pulmonary angiogram shows left pulmonary artery stenosis.

Because of the preoperative diagnosis of Takayasu's arteritis, the patient was started on steroids. She presented no focus of tuberculosis, but a Mantoux test was positive. Because subclinical exposure to tuberculosis is common in the Indian subcontinent and an association of tuberculosis with Takayasu's arteritis has been shown,1 4-drug antitubercular therapy was begun. Her C-reactive protein level and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate were normal after 7 days.

The patient was taken for coronary revascularization. On inspection, the ascending aorta was thickened in places. The myocardial tissue and epicardial fat were all edematous. The left internal mammary artery (LIMA) and right internal mammary artery (RIMA) were harvested, and a Y graft was constructed. She underwent off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), with Y-graft anastomosis of the LIMA to the LAD artery and the RIMA to the obtuse marginal artery (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Intraoperative photograph shows left internal mammary artery–right internal mammary artery Y graft to the left anterior descending and obtuse marginal coronary arteries, and surrounding edematous tissues.

The patient experienced an uneventful intraoperative and postoperative course. All electrocardiographic readings reverted to normal. She continued on a regimen of steroids for 6 weeks and was then put on methotrexate. She continued taking antitubercular drugs for 6 months. As of her 18-month follow-up, she remained completely asymptomatic, with good exertional tolerance.

Discussion

Takayasu's arteritis, a chronic inflammatory arterial disease of unknown cause, occurs predominantly in young women. The condition involves elastic arteries such as the aorta and its main branches, and sometimes the pulmonary arteries. The inflammation leads to stenosis and occlusion of the involved artery, aneurysmal formation, or both.1,2 The origin of aortic arch arteritis remains unknown. Various treatments, including steroids, vascular surgery, and balloon angioplasty, have been used in the management of these patients. The 1st choice of treatment in patients who have Takayasu's arteritis and noncritical vascular involvement is immunosuppression, primarily with corticosteroids. When steroids are administered, a 40% to 60% rate of remission is seen. Approximately 40% of steroid-resistant patients respond to the steroids with the addition of cytotoxic agents. Methotrexate, an alternative to cyclophosphamide as an immunosuppressive agent, may induce remission when other treatments have failed. Approximately 20% of all patients are resistant to any kind of treatment.3–5

The 1st classification and natural history of Takayasu's arteritis was reported by Ishikawa2 in 1985. Clinical findings were classified into 4 groups: Group 1, uncomplicated disease with or without pulmonary arterial involvement; Group 2, a mild or moderate single complication along with uncomplicated disease; Group 3, a severe single complication with uncomplicated disease; and Group 4, uncomplicated disease plus 2 or more complications.

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology established criteria for classification of the disease.6 In 1994, a new classification was framed on the basis of angiographic findings.7 Type 1 findings involved branches from the aortic arch; Type 2a, the ascending aorta, and the aortic arch and its branches; Type 2b, the ascending aorta, aortic arch and its branches, and the descending thoracic aorta; Type 3, the descending thoracic aorta, abdominal aorta, or the renal arteries; Type 4, the abdominal aorta or the renal arteries; and Type 5, the combination of Type 2b and Type 4 features. According to this system, involvement of coronary arteries should be labeled C(+), and involvement of pulmonary arteries should be labeled P(+).

Although these systems are useful in that they enable a comparison of patients' characteristics according to the vessels involved and are thus helpful in the planning of surgery, they offer little insight into comparative postsurgical prognoses. Coronary angiographic and pathologic studies together have revealed coronary artery lesions in 9% to 11% of cases.8,9 Coronary artery involvement consists mostly of stenosis or occlusion of coronary ostia, which was first described by Frovig and Loken10 as a fatal complication. It is rare for patients to present with coronary ostial stenosis and no other arch-vessel involvement.11,12 Coronary ostial stenosis occurs as a result of the extension of inflammation, which induces intimal proliferation and fibrous contraction in the ascending aorta around the coronary ostia. Coronary aneurysms associated with Takayasu's arteritis are extremely rare.10 Nasu11 reported a 10.5% rate of coronary lesions that complicated Takayasu's arteritis.

Three surgical approaches are CABG, patch angioplasty of the LMCA ostium, and transaortic coronary ostial endarterectomy.15 The timing of the operation is important, because surgery should be avoided during the active stage of inflammation. Nonetheless, in a patient with unstable angina, such as ours, surgery should be performed without delay, because myocardial infarction is a major sequela in such patients. The choice of conduit—either a saphenous vein graft or an internal mammary artery (IMA)—is controversial. The long-term graft patency of the IMA versus the saphenous vein in atherosclerotic patients favors the use of the IMA, provided that its origin and that of the proximal subclavian artery are normal,16 as they were in our patient. The main drawback of the IMA is compromise of the grafts when the disease recurs and involves the origin of the subclavian artery or the brachiocephalic trunk. Conventional CABG with a saphenous vein graft can be used in cases of arch-vessel involvement if the IMA fails; however, in cases of concomitant coronary and arch-vessel involvement (which are more common than isolated coronary involvement), saphenous vein grafting is a better choice.8,10

Other options besides CABG are coronary ostioplasty, transaortic coronary ostial endarterectomy, or a hybrid procedure. In coronary ostioplasty, a patch can be created from a piece of autologous pericardium (with or without glutaraldehyde treatment), saphenous vein graft, or internal thoracic artery.15 Transaortic coronary ostial endarterectomy was first described by Endo in 1982.17 Another special technique is hybrid CABG, which consists of preoperative stent insertion and off-pump CABG with a saphenous vein or internal thoracic artery graft.15 The hybrid procedure is used mainly in patients who have a porcelain aorta.

The use of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in isolated cases of Takayasu's disease has been reported.18 Stenting may be performed in an emergency, in patients who refuse surgery, or in high-risk patients who have severe pulmonary hypertension. The medical literature says little about the occurrence of in-stent restenosis in those cases, but directional atherectomy and sirolimus-eluting stents have reportedly been used to reduce restenosis.19

Summary

In young patients (particularly women) who present with angina during rest or exertion, Takayasu's arteritis should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Clinicians should consider the possibility of congenital or atherosclerotic20,21 ostial obstruction. Only histologic examination of the aortic biopsy sample can confirm the diagnosis. However, pulmonary-vessel involvement, elevated inflammatory mediators, and geographic distribution of the disease (occurrence is most commonly in Asians and women) can support a diagnosis of Takayasu's arteritis. Stabilization with steroids and timely surgical intervention can prevent death, and the use of high-patency internal thoracic artery grafts in patients with normal arch vessels can prolong survival.

In our patient, who had ostial and LMCA stenosiswith left-dominant circulation, an arterial Y graft provided better perfusion to the compromised myocardium than a single graft to the LAD artery would have. Also of note: in our patient, with left-dominant circulation, the low amount of retrograde flow in the proximal LAD artery across the diseased distal LMCA into the circumflex artery would have jeopardized the myocardium.

Although angiography may show normal ostia of the LAD and circumflex arteries, only intravascular ultrasonography can reveal a compromise of both ostia and the distal LMCA lumen that has arisen from an inflammatory process. In our patient, the Y graft obviated the need to perform a proximal anastomosis on an inflamed, edematous ascending aorta, and it conferred the advantage of the better long-term patency rate of the IMA. In cardiopulmonary bypass operations, off-pump beating-heart surgery helps to avert a systemic inflammatory response, which is why we chose this approach in our patient. If the patient's disease progresses to left subclavian artery involvement, the arterial Y-grafts will be compromised; however, vein grafts may be used for reoperation.

Because Takayasu's arteritis was restricted to our patient's LMCA, we believe that the palliation offered was appropriate. In such cases, however, we strongly recommend follow-up examination of the arterial graft patency at regular intervals.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: A.M. Patwardhan, MCh, P.K. Sen Department of Cardiovascular & Thoracic Surgery, King Edward Memorial Hospital and Seth G.S. Medical College, Mumbai 400012, India. E-mail: anilpatwardhan@hotmail.com

References

- 1.Sen PK, Kinare SG, Kelkar MD, Parulkar GB. Nonspecific aortoarteritis—a monograph based on a study of 101 cases. Bombay: Tata McGraw-Hill; 1972. p. 41–2.

- 2.Ishikawa K. Natural history and classification of occlusive thromboaortopathy (Takayasu's disease). Circulation 1978; 57:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J, Leavitt RY, Fauci AS, Rottem M, Hoffman GS. Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:919–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hall S, Barr W, Lie JT, Stanson AW, Kazmier FJ, Hunder GG. Takayasu arteritis. A study of 32 North American patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985;64:89–99. [PubMed]

- 5.Shelhamer JH, Volkman DJ, Parrillo JE, Lawley TJ, Johnston MR, Fauci AS. Takayasu's arteritis and its therapy. Ann Intern Med 1985;103:121–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Calabrese LH, Edworthy SM, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1129–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Johnston SL, Lock RJ, Gompels MM. Takayasu arteritis: a review. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:481–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Cipriano PR, Silverman JF, Perlroth MG, Griepp RB, Wexler L. Coronary arterial narrowing in Takayasu's aortitis. Am J Cardiol 1977;39:744–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Makino N, Orita Y, Takeshita A, Nakamura M, Matsui K, Tokunaga K. Coronary arterial involvement in Takayasu's disease. Jpn Heart J 1982;23:1007–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Frovig AG, Loken AC. The syndrome of obliteration of the arterial branches of the aortic arch, due to arteritis; a post-mortem angiographic and pathological study. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand 1951;26:313–37. [PubMed]

- 11.Noma M, Sugihara M, Kikuchi Y. Isolated coronary ostial stenosis in Takayasu's arteritis: case report and review of the literature. Angiology 1993;44:839–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kihara M, Kimura K, Yakuwa H, Minamisawa K, Hayashi S, Umemura S, et al. Isolated left coronary ostial stenosis as the sole arterial involvement in Takayasu's disease. J Intern Med 1992;232:353–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Suzuki H, Daida H, Tanaka M, Sato H, Kawai S, Sakurai H, Yamaguchi H. Giant aneurysm of the left main coronary artery in Takayasu aortitis. Heart 1999;81:214–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Nasu T. Takayasu's truncoarteritis in Japan. A statistical observation of 76 autopsy cases. Pathol Microbiol (Basel) 1975;43: 140–6. [PubMed]

- 15.Endo M, Tomizawa Y, Nishida H, Aomi S, Nakazawa M, Tsurumi Y, et al. Angiographic findings and surgical treatments of coronary artery involvement in Takayasu arteritis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:570–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Singh SK, Kumar D, Yadave RD, Khanna AR, Sinha SK. “Y” graft bypass for bilateral coronary ostial aortoarteritis. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2002;10:162–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Endo M, Ooteki H, Ishihara S, Koyanagi H, Takahashi K, Iseki K, et al. Transaortic intraoperative angioplasty (Gruntzig) and punch-out endarterectomy. Cardioangiology 1982; 11:63–7.

- 18.Lee HY, Rao PS. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in Takayasu's arteritis. Am Heart J 1996;132:1084–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Furukawa Y, Tamura T, Toma M, Abe M, Saito N, Ehara N, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stent for in-stent restenosis of left main coronary artery in takayasu arteritis. Circ J 2005;69:752–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Patwardhan AM, Pantvaidya SH, Pahlajani DB, Patil RB, Vishwanathan M, Chaukar AP. Left main coronary block in a nineteen-year-old woman. Tex Heart Inst J 1985;12:199–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Satran A, Dawn B, Leesar MA. Congenital ostial left main coronary artery stenosis associated with a bicuspid aortic valve in a young woman. J Invasive Cardiol 2006;18:E114–6. [PubMed]