Abstract

About half of the world’s population is exposed to smoke from heating or cooking with coal, wood, or biomass. These exposures, and fumes from cooking oil use, have been associated with increased lung cancer risk. Glutathione S-transferases play an important role in the detoxification of a wide range of human carcinogens in these exposures. Functional polymorphisms have been identified in the GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 genes, which may alter the risk of lung cancer among individuals exposed to coal, wood and biomass smoke and cooking oil fumes. We performed a meta-analysis of six published studies (912 cases; 1063 controls) from regions in Asia where indoor air pollution makes a substantial contribution to lung cancer risk, and evaluated the association between the GSTM1 null, GSTT1 null, and GSTP1 105Val polymorphisms and lung cancer risk. Using a random effects model, we found that carriers of the GSTM1 null genotype had a borderline significant increased lung cancer risk (odds ratio (OR), 1.31; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.95–1.79; p=0.100), which was particularly evident in the summary risk estimate for the four studies carried out in regions of Asia that use coal for heating and cooking (OR, 1.64; 95%CI, 1.25–2.14; p=0.0003). The GSTT1 null genotype was also associated with an increased lung cancer risk (OR, 1.49; 95%CI, 1.17–1.89; p=0.001), but no association was observed for the GSTP1 105Val allele. Previous meta- and pooled-analyses suggest at most a small association between the GSTM1 null genotype and lung cancer risk carried out in populations where the vast majority of lung cancer is attributed to tobacco, and where indoor air pollution from domestic heating and cooking is much less than in developing Asian countries. Our results suggest that the GSTM1 null genotype may be associated with a more substantial risk of lung cancer in populations with coal exposure.

Keywords: coal, heating and cooking, nonsmoking lung cancer, GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1

1. Introduction

About half of the world’s population or 3 billion people, almost all living in developing countries such as China and India, use coal, wood, and biomass for heating and cooking [1]. The annual global health burden of indoor air pollution from solid fuel use is estimated to be 1.6 million deaths and over 38.5 million disability-adjusted life years [2]. This equates to 3% of the total global disease burden. Coal, wood, and biomass smoke, and cooking oil fumes have been associated with a variety of health outcomes [3–13], the most notable being lung cancer [14–16]. Recently, an IARC Working Group met to assess the potential carcinogenicity of household use of solid fuels (coal and biomass) and of high-temperature frying. This comprehensive review concluded that indoor emissions from household combustion of coal are carcinogenic to humans (Group 1), while indoor emissions from household combustion of biomass fuel (primarily wood) and emissions from high-temperature frying are probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A) [17].

The associations observed between indoor air pollution and lung cancer risk are not surprising since fuel combustion products are known to contain carcinogens. In-home smoky coal combustion increases levels of sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, fluorine, and known carcinogens such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), benzene, arsenic, and formaldehyde [18;19]. The corresponding concentrations of benzo(a)pyrene, an indicator of PAHs, from indoor exposures to coal smoke due to cooking and heating can be comparable in some instances to coke oven occupational exposure levels [20]. Cooking oils are commonly heated to high temperatures in woks in Asian cultures and frequently contain numerous mutagens and carcinogens [21]. Peanut oil for example, releases 12 mutagenic compounds when heated [22]. Soybean oil, sunflower oil, rapeseed oil, and lard induce oxidative stress and have been found to have genotoxic properties [23;24].

Genetic variation in enzymes responsible for activating and detoxifying PAHs or other carcinogens present in these environments may alter susceptibility in individuals exposed to coal, wood, and biomass smoke, as well as to cooking oil fumes. This variation could result in significant inter-individual differences in risk at the same level of exposure. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) are involved in the metabolic detoxification of reactive electrophilic compounds, such as PAHs, that are formed during incomplete combustion of carbon-based fuels such as coal and wood [18;25]. There are five known classes of GST enzymes in humans that are important in the metabolism of xenobiotics: GSTA (α), GSTM (μ), GSTP (π), GSTS (σ), and GSTT (θ) [26]. Genetic variants in three of these genes (GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1) have been extensively studied in relation to risk of lung cancer [27]. The GSTM1 and GSTT1 enzymes have been shown to inhibit cellular damage from cytotoxic substances in in vitro studies [28]. The most common functional polymorphism in both the GSTM1 and GSTT1 genes is a deletion, which leads to a lack of function and decreased ability to detoxify electrophilic carcinogens efficiently [29]. Similarly, subjects carrying the GSTP1 Ile105Val Val/Val genotype have a lower ability to detoxify electrophilic compounds than subjects carrying the wildtype genotype, Ile/Ile [29]. Variants in these genes may reduce an individual’s ability to detoxify PAHs and could increase risk for various cancers, including lung cancer [30;31].

The association between lung cancer and the GSTM1 deletion, GSTT1 deletion, and GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphisms have been studied and reviewed in meta-analyses and a pooled analysis, with most work focusing on the GSTM1 null genotype [32–35]. After consideration of potential publication bias, there is little evidence that the GSTM1 null genotype is associated with risk of lung cancer, either among ever-smokers or never-smokers [32;33].

To summarize findings on genetic susceptibility to cancer in populations exposed to coal, wood, and biomass smoke and cooking oil fumes, a systematic review of studies evaluating GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 genotypes and risk of lung cancer in Asian populations, where exposure to indoor air pollution is ubiquitous and in some instances present at relatively high levels, was carried out.

Methods

Studies examining the association between GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 genotypes and susceptibility to lung cancer with indoor air pollution exposures were identified by searching the PubMed and Science Citation Index databases. Studies in English published between January 1966 and July 2006, were identified though searches that used keywords associated with relevant genes (e.g., GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1) in combination with words related to indoor air pollution (e.g., indoor air pollution, coal, wood, biomass, cook fume, cook oil) and words related to lung cancer (lung cancer, lung neoplasm). For this analysis, only studies in populations carried out in Asian populations with exposure to coal, wood, and biomass smoke, and cooking oil fumes were considered. Studies were then selected using a three tiered exclusion/inclusion approach. First, studies in which tobacco smoke was the primary cause of lung cancer in the study population were excluded. This included studies that were comprised of only smokers or those in which the lung cancer risk was attributed to smoking in the conclusion of the article. Of the remaining studies, those with either a quantitative or qualitative exposure assessment of coal, wood, or biomass smoke, or cooking oil fumes were included. Finally, for studies that did not carry out an assessment of these exposures, those that had potential indoor air pollution exposures were included if one of the following criteria were met: (1) the article explicitly stated that the subjects’ lung cancer was attributed to exposure from coal, wood, or biomass smoke, or cooking oil fumes or (2) exposure to coal, wood, or biomass smoke, or cooking oil fumes was previously shown to play an important role in the etiology of lung cancer in the same study subjects in previously published reports referenced by the article. For the latter, the respective previous studies were reviewed and the primary exposure was determined to be either smoke from coal, wood, or biomass smoke, or cooking oil fumes.

Studies were identified by a search using “GSTM1” and “lung cancer” in combination with “coal”, “wood”, “biomass”, or “cooking”. The papers were then reviewed to identify case-control studies in Asian populations. A total of 11 case-control studies [36–46] were found. Five studies [36–40] were excluded because there was no exposure assessment and no evidence provided in the study that indoor air pollution from any source made an important contribution to lung cancer. The remaining 6 studies [41–46] satisfied all inclusion criteria, and data related to study design, geographic location, population setting, case selection, control selection, genotyping method, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, type of exposure, exposure assessment, smoking, and number of genotyped cases and controls were extracted.

Overall, one study utilized a quantitative exposure assessment [41], one a qualitative exposure assessment [42], and the presence of indoor air pollution was determined for four studies [43–46]. Lan et al’s [41] study was in Xuan Wei, where more than 95% of the population was exposed to coal and a substantial portion of lung cancer has been attributed to indoor coal use [14;47]. Similarly more than 95% of the population in the Shenyang study reported by Yang et al. [45] was also exposed to coal [45;48], and epidemiologic studies have shown that coal exposure is associated with increased risk of lung cancer in Shenyang [49–51]. Approximately 80% of the population in Changsha City in the Hunan study for nonsmoking lung cancer cases and controls by Chen et al. [43] were exposed to coal up until 1997 (Han-chun Chen, personal communication), and about 80% of the population in the Beijing study by Wang et al. [46] used coal in their homes (Jingwen Wang, personal communication). Although formal risk estimates have not been published for coal use and lung cancer in these two studies, it is highly likely that this exposure is associated with risk of lung cancer [17]. Furthermore, the primary source of fuel for household use in Thailand up to 1- year before Pisani et al.’s [42] study began was wood and charcoal [52]. Finally, the primary fuel sources in Hong Kong up until recently were kerosene and liquid petroleum gas [53]. Since combustion from these fuel sources is not known to be associated with lung cancer, while an excess of lung cancer risk has been attributed to cooking oil fume exposure in Chan-Yeung et al’s [44] and other study populations in Hong Kong [54;55], the primary exposure for Chan-Yeung et al’s [44] Hong Kong study population was classified as cooking oil fumes. In conclusion, the four studies [41;43;45;46] carried out in mainland China were classified as having primarily coal exposure, the study in Thailand [42] was classified as wood and charcoal exposure, and the study in Hong Kong [44] was classified as cooking oil fume exposure.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 9 (College Station, Texas). Heterogeneity among studies was determined using a χ2-based Q-statistic [56]. For the only two possible genotypes for GSTM1 and GSTT1 status, the unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) from each study were used to estimate summary odds ratios. For GSTP1, the unadjusted odds ratio for the dominant genetic model (Val/Val + Val/Ile vs. Ile/Ile) for each study was calculated and used to estimate summary odds ratios. Since there was some evidence of heterogeneity in preliminary analyses, summary odds ratios were determined using a random effects model in which the contribution of each study was weighted by the inverse of the sum of the inter- and intra-study variance. Summary odds ratios were also calculated after stratification by control selection methodology (population-based only) and type of exposure (coal smoke only). Finally, publication bias was assessed via funnel plots and the Begg’s test [57].

3. Results

Six studies evaluating GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 genotypes and their association with risk of lung cancer met the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis [41–46]. Table 1 provides a summary of each gene’s name and chromosomal location. All studies were case-control by design and five studies used population-based controls [41;43–46], while one used a combination of population- and hospital-based controls [42] (Table 2). One study was in a rural setting [41], three in an urban setting [44–46], and two in a mixed setting, consisting of both rural and urban [42;43]. In four studies, coal was the primary fuel exposure [41;43;45;46], in one study cooking oil fumes was the exposure [44], and in the final study, exposure to both charcoal and wood was present [42].

Table 1.

Description of glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms.

| Gene | Name | Chromosomal Location | SNP rs number | Nucleotide change | Amino Acid Change | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSTM1 | glutathione S-transferase M1 | 1p13.3 | gene deletion | [41–46] | ||

| GSTP1 | glutathione S-transferase pi | 11q13 | rs947894 | Ex5-24A>G | Ile105Val | [43;44;46] |

| GSTT1 | glutathione S-transferase theta 1 | 22q11.23 | gene deletion | [41;43;44;46] |

Table 2.

Characteristics of case-control studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Controls | Number Genotyped | Smokers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Region | Population Setting | Source | Matching Factors | Cases | Controls | HWE? | Exposure | Cases (%) | Controls (%) |

| GSTM1 null (gene deletion) | ||||||||||

| Lan, 2000 | Yunnan | Rural | Population-based | gender, age, village, type fuel | 122 | 122 | N/A | Coal | 70 (57%) | 69 (57%) |

| Wang, 2003 | Beijing | Urban | Population-based | gender,age | 112 | 119 | N/A | Coal | 48 (43%) | 48 (40%) |

| Chan-Yeung, 2004 | Hong Kong | Urban | Population-based | none | 229 | 197 | N/A | Cooking Oil | 130 (57%) | 79 (40%) |

| Yang, 2004 | Shenyang | Urban | Population-based | age | 186 | 139 | N/A | Coal | 111 (55.5%) | 54 (37.5%) |

| Chen, 2006 | Hunan | Mixed | Population-based | gender,age | 97 | 197 | N/A | Coal | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pisani, 2006 | Thailand | Mixed | Population- and hospital-based | gender,age | 166 | 289 | N/A | Charcoal/Wood | 93 (44%) | 145 (36%) |

| TOTAL | 912 | 1063 | ||||||||

| GSTT1 null (gene deletion) | ||||||||||

| Lan, 2000 | Yunnan | Rural | Population-based | gender, age, village, type fuel | 122 | 122 | N/A | Coal | 70 (57%) | 69 (57%) |

| Wang, 2003 | Beijing | Urban | Population-based | gender, age | 112 | 119 | N/A | Coal | 48 (43%) | 48 (40%) |

| Chan-Yeung, 2004 | Hong Kong | Urban | Population-based | none | 229 | 197 | N/A | Cooking Oil | 130 (57%) | 79 (40%) |

| Chen, 2006 | Hunan | Mixed | Population-based | gender, age | 97 | 197 | N/A | Coal | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| TOTAL | 560 | 635 | ||||||||

| GSTP1 Ile105Val (rs947894) | ||||||||||

| Wang, 2003 | Beijing | Urban | Population-based | gender, age | 112 | 119 | Yes | Coal | 48 (43%) | 48 (40%) |

| Chan-Yeung, 2004 | Hong Kong | Urban | Population-based | none | 229 | 197 | Yes | Cooking Oil | 130 (57%) | 79 (40%) |

| Chen, 2006 | Hunan | Mixed | Population-based | gender, age | 97 | 197 | * | Coal | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| TOTAL | 438 | 513 | ||||||||

Not reported

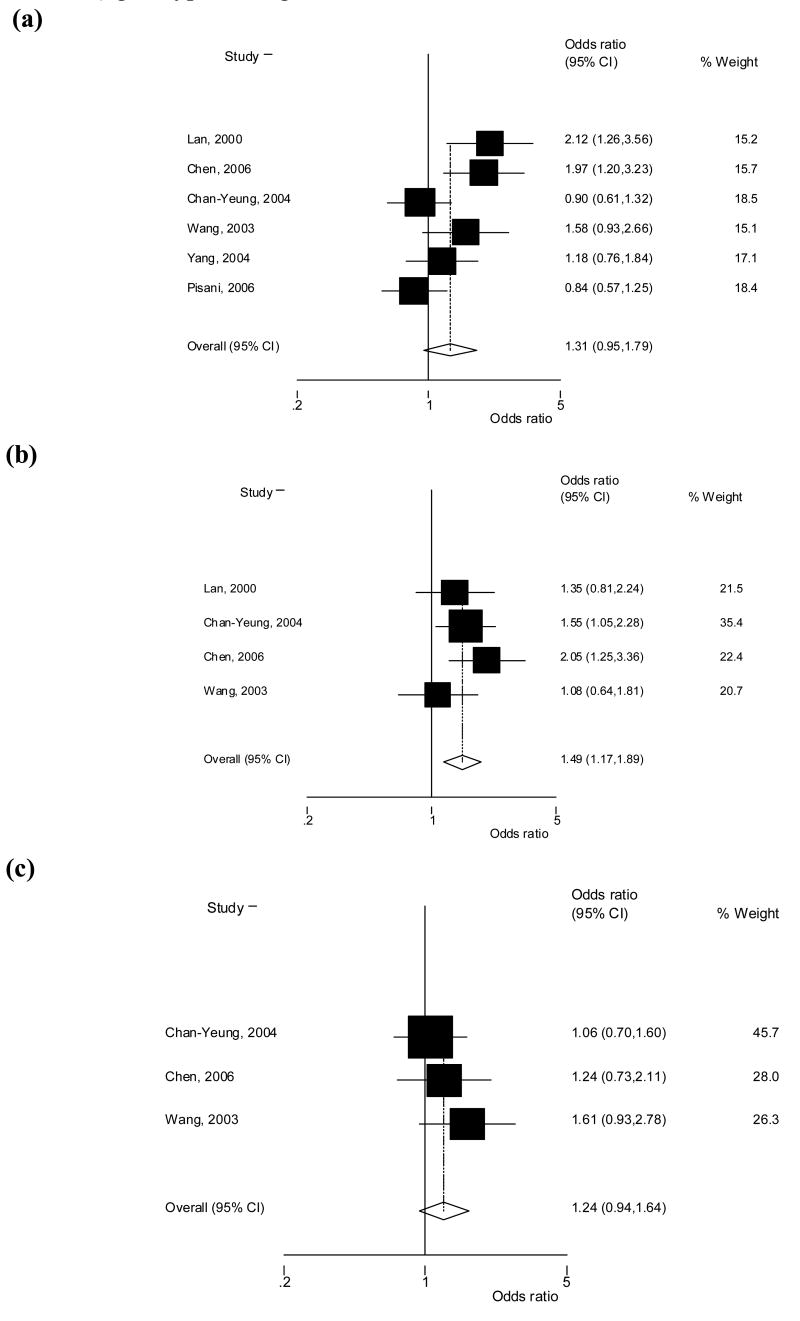

All six studies evaluated the association of the GSTM1 null genotype and risk of lung cancer for a total of 912 cases and 1063 controls [41–46]. The average sample size was 152 cases and 177 controls and the studies were found to be statistically heterogeneous (p = 0.01). Heterogeneity in the summary risk estimate was decreased somewhat by removing the only study that utilized hospital- and population-based controls, which also had not been carried out in China (p = 0.04). There was no evidence of heterogeneity (p = 0.31) in the summary risk estimate based on the four studies with coal exposure. Four of the studies found the GSTM1 null genotype to be associated with an increased risk of lung cancer, which was statistically significant in two studies [41;43]. No association was observed by the other two studies. In our meta-analysis, carriers of the GSTM1 null genotype were found to have a borderline significant increased risk of lung cancer compared to those with at least one allele present (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.95–1.79; p = 0.100) (Figure 1a). The GSTM1 null genotype was significantly associated with an increased risk of lung cancer among the five studies that used population-based controls (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.03–2.00; p = 0.033) and among the four studies that identified coal exposure as an important contributor to lung cancer (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.25–2.14; p = 0.0003) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for the association between lung cancer and (a) GSTM1 null, (b) GSTT1 null, and (c) GSTP1 Ile105Val (Ile/Val + Val/Val vs Ile/Ile) genotypes, using random effects.

Table 3.

Summary odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 genotypes and lung cancer risk stratified by study characteristics, using the random effects model.

| All studies | Population-based Controls | Coal Smoke Exposure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSTM1 null | 1.31 (0.95–1.79) | 1.44 (1.03–2.00) | 1.64 (1.25–2.14) |

| # of studies | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Cases/Controls (n) | 912/1063 | 746/774 | 517/577 |

| GSTT1 null | 1.49 (1.17–1.89) | 1.49 (1.17–1.89) | 1.45 (1.00–2.09) |

| # of studies | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Cases/Controls (n) | 560/635 | 560/635 | 331/438 |

| GSTP1 Ile105Val* | 1.24 (0.94–1.64) | 1.24 (0.94–1.64) | 1.41 (0.96–2.06) |

| # of studies | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Cases/Controls (n) | 438/513 | 438/513 | 209/316 |

GSTP1 Ile105Val and Val105Val versus GSTP1 Ile105Ile

Of the six studies, four evaluated the GSTT1 null genotype and lung cancer risk for a total of 560 cases and 635 controls [41;43;44;46]. The average sample size was 140 cases and 159 controls and there was not evidence of heterogeneity (p = 0.36). All four of these studies used population-based controls and found an elevated risk of lung cancer associated with the GSTT1 null genotype, which was statistically significant in two studies [43;44]. The increased risk of lung cancer observed among carriers of the GSTT1 null genotype compared to those with at least one allele present was statistically significant for this meta-analysis (OR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.17–1.89; p = 0.0001) (Figure 1b). The GSTT1 null genotype was associated with a significant increased risk of lung cancer among the three studies that reported coal exposure (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.00 – 2.09; p = 0.048) (Table 3).

Only three studies evaluated the GSTP1 Ile105Val (rs947894) polymorphism and lung cancer risk for a total of 438 cases and 513 controls, with an average sample size of 146 cases and 171 controls per study [43;44;46]. There was no evidence of heterogeneity (p = 0.77). Due to the reporting limitations in the original studies, only the dominant genetic model (Ile/Val + Val/Val vs Ile/Ile) could be evaluated. All three of the studies found a non-significant increased risk of lung cancer associated with the GSTP1 105Val allele. In this meta-analysis, carriers of the Val allele were found to have a non-significant increased risk of lung cancer (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.94–1.64; p = 0.136) (Figure 1c). Due to the low number of studies and one study that did not report if the genotype frequencies in the control subjects were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [43], meaningful conclusions could not be drawn from the stratifications of study characteristics for the GSTP1 105Val allele. Of note, the odds ratio for GSTP1 Val variant was elevated among the two studies with coal exposure (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 0.96–2.06; p = 0.076) compared to the summary odds ratio for all studies (Table 3).

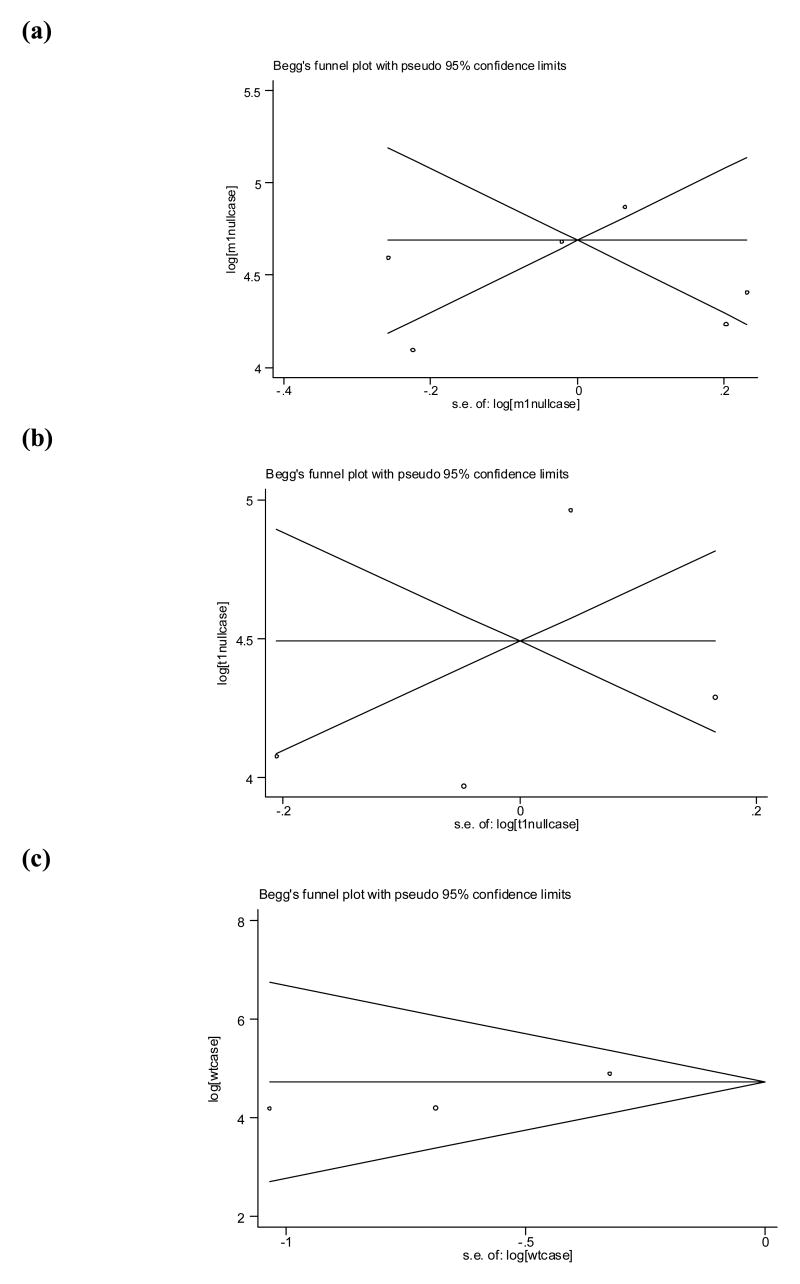

Finally, there was no evidence of publication bias for the GSTM1 (p = 0.85), GSTT1 (p = 0.50), and GSTP1 (p = 0.60) studies (Figure 2), or for the four studies that evaluated GSTM1 genotype and coal exposure (p = 0.73).

Figure 2.

Begg’s funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits for studies evaluating the association between lung cancer and (a) GSTM1 null, (b) GSTT1 null, and (c) GSTP1 Ile105Val (Ile/Val + Val/Val vs Ile/Ile) genotypes, using random effects.

4. Discussion

We carried out what is, to the best of our knowledge, the first systematic review of the growing literature on genetic susceptibility of lung cancer in Asian populations with exposure to coal, wood, and biomass smoke, and cooking oil fumes. This meta-analysis found that the GSTM1 null genotype may be associated with an increased risk of lung cancer in populations exposed to these sources of indoor air pollution from cooking and heating, with no evidence of publication bias. Further, the association between the GSTM1 null genotype and lung cancer was particularly evident in studies carried out in populations that used coal for home heating and cooking (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.25 – 2.14; p = 0.0003).

In the most recent meta-analysis of 119 studies, almost all of which were carried out in populations where tobacco use is likely to be the primary cause of lung cancer, the GSTM1 null genotype was associated with a significantly increased lung cancer risk (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.14–1.23) [32]. However, there was strong evidence of publication bias from positive findings in smaller studies (Begg’s test p < 0.0001). Restriction to the five studies with greater than 500 cases yielded no association with the GSTM1 null genotype (OR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.95–1.14). A pooled analysis of 21 studies found similar risks for ever-smokers (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.0 – 1.2) and never-smokers (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.8 – 1.4) [33]. In sub-analyses for studies carried out in Asia, there was a non-significant increase in risk for ever-smokers (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.9 – 1.7) and a non-significant decrease in risk for never-smokers (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.4 – 1.4). However, these estimates were based on a relatively small number of study subjects [33]. Overall, the weight of evidence suggests that the GSTM1 null genotype is associated with at most a small risk of lung cancer. The results of our meta-analysis suggest that this genetic variant may play a more substantial role in lung cancer among populations that use coal for home heating and cooking in certain parts of Asia.

There is further evidence supporting the unique characteristics of lung cancer attributed to coal exposure, with evidence that risk may be driven in great part by PAHs, which are substrates for detoxification by GSTM1 [30;31]. The GST family members’ ability to catalyze the detoxification of PAHs varies for GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 [58–60]. Both in vivo and in vitro studies have concluded that the GSTM1 null and GSTP1 105Val genotypes decrease the body’s PAH detoxification efficiency [58;59], while the GSTT1 null genotype seems to not play an important role in PAH metabolism [31]. Since GSTM enzymes have a 20-fold higher reaction velocity than the GSTP enzymes, it is conceivable that the GSTM1 gene may have greater importance for detoxifying PAHs [61]. DeMarini et al., reported that 76% of the p53 mutations in a series of 24 tumor samples from nonsmoking women in Xuan Wei, China, where exposure to combustion products of smoky coal accounts for the vast majority of lung cancer, were G to T transversions, consistent with the mutational spectrum of PAHs. In lung cancer tumors from the IARC TP53 mutation database (version DataR4, April 2000), this transversion was present in only 29% of tumors from smokers (p = 0.09 versus smoky coal users) and 11% of tumors from non-smokers (p = 0.0003 versus smoky coal users) [62]. This mutational spectrum suggests that PAHs may play a more important role in the pathogenesis of lung cancer in Xuan Wei, China, than their role in the etiology of lung cancer among smokers and nonsmokers in populations without smoky coal exposure. Exposure to smoky coal has also been associated with increased PAH–DNA adducts levels in Xuan Wei, China [63]. Similarly, 58% of the placentas and 77.8% of peripheral and cord white blood cells of women from Xuan Wei burning smoky coal in homes without chimneys were positive for PAH-DNA adducts compared to only 5% and 33.3% of controls, respectively [64]. In addition, the GSTM1 null genotype has been associated with the presence of PAH-DNA adducts in lung tissue (OR, 8.6; 95% CI, 1.03–100) [65]. Further, one study included in our meta-analysis [41] found that the risk of lung cancer increased 1.2 fold (95% CI, 0.8 – 1.9) for GSTM1 positive subjects per 100 tons of lifetime smoky coal use and increased 2.4 fold per 100 tons for those with the GSTM1 null genotype (95% CI, 1.6 – 3.9) (p for interaction = 0.05). Although the GSTT1 null genotype was associated with increased risk of lung cancer in our meta-analysis, there was some evidence of an effect among coal users, which is a bit unexpected given that this enzyme may not play an important role in PAH metabolism [31].

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. Although no evidence of publication bias was observed, our assessment was based on relatively few studies and publication bias can not be definitively ruled out. Secondly, the crude odds ratios from each study were used to estimate summary odds ratios and it is possible that some uncontrolled confounding was present. However, with the exception of age and race, confounding is unlikely to be a major source of bias in genetic studies. To support this assertion, a meta-analysis of the limited number of studies that reported adjusted odds ratios in this study was conducted and found similar results.

In conclusion, we found evidence that the GSTM1 null genotype was associated with a statistically significant increased risk of lung cancer in Asian populations exposed to coal smoke, based on a meta-analysis of four studies. Although consistent with the biology of PAH metabolism and the known function of the GSTM1 null genotype, this finding should be considered hypothesis generating and requires replication in additional and larger studies. It is also important that future studies include a detailed assessment for exposure to fuels from all possible sources and by all potential routes, and for amount as well as frequency and other characteristics of use. Such studies will also provide an opportunity to identify other genetic factors that may modify the effect of exposure to combustion products of coal and other indoor fuel sources and fumes, as well as other important co-factors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.World Resources Institute., United Nations Environment Programme., United Nations Development Programme., B. World. A guide to the global environment. A special reprint from World Resources, 1996–97. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. The urban environment; p. iv.p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezzati M World Health Organization. Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiraz K, Kart L, Demir R, Oymak S, Gulmez I, Gulmez I, Unalacak M, Ozesmi M. Chronic pulmonary disease in rural women exposed to biomass fumes. Clin Invest Med. 2003;26:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrestha IL, Shrestha SL. Indoor air pollution from biomass fuels and respiratory health of the exposed population in Nepalese households. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2005;11:150–160. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2005.11.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra V, Retherford R, Smith KR. Biomass cooking fuels and prevalence of tuberculosis in India. Int J Infect Dis. 1999;3:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(99)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pokhrel A, Smith K, Khalakdina A, Deuja A, Bates M. Case-control study of indoor cooking smoke exposure and cataract in Nepal and India. Int J Epidemiol. 2005 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi015. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wichmann J, Voyi KV. Influence of Cooking and Heating Fuel Use on 1–59 Month Old Mortality in South Africa. Matern Child Health J. 2006;0:0. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0121-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schei MA, Hessen J, Smith KR, Bruce N, McCracken J, Lopez V. Childhood asthma and indoor woodsmoke from cooking in Guatemala. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2004;14:S110–S117. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pintos J, Franco E, Kowalski L, Oliveira B, Curado MP. Use of wood stoves and risk of cancers of the upper aero-digestive tract: a case-control study. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:936–940. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.6.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang D, Li T, Liu JJ, Chen Y, Qu L, Perera F. PAH-DNA adducts in cord blood and fetal and child development in a Chinese cohort. Environmental health perspectives. 2006;114:1297–1300. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mishra V, Dai X, Smith KR, Mika L. Maternal exposure to biomass smoke and reduced birth weight in Zimbabwe. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J, Hanley JA. The role of woodstoves in the etiology of nasal polyposis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:682–686. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.6.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters E, Esin R, Immananagha K, Siziya S, Osim EE. Lung function status of some Nigerian men and women chronically exposed to fish drying using burning firewood. Cent Afr J Med. 1999;45:119–124. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v45i5.8467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mumford JL, He XZ, Chapman RS, Cao SR, Harris DB, Li XM, Xian YL, Jiang WZ, Xu CW, Chuang JC. Lung cancer and indoor air pollution in Xuan Wei, China. Science. 1987;235:217–220. doi: 10.1126/science.3798109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metayer C, Wang Z, Kleinerman RA, Wang L, Brenner AV, Cui H, Cao J, Lubin JH. Cooking oil fumes and risk of lung cancer in women in rural Gansu, China, Lung cancer (Amsterdam. Netherlands) 2002;35:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez-Garduno E, Brauer M, Perez-Neria J, Vedal S. Wood smoke exposure and lung adenocarcinoma in non-smoking Mexican women. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El F, Ghissassi F, Cogliano V. Carcinogenicity of household solid fuel combustion and of high-temperature frying. Lancet Oncology. 2006;7:977–978. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(06)70969-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans., International Agency for Research on Cancer., National Cancer Institute (U.S.) Polynuclear aromatic compounds, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Albany, N.Y: WHO Publications Centre USA [distributor], [Lyon]; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Smith KR. Indoor air pollution: a global health concern. British medical bulletin. 2003;68:209–225. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mumford JL, Li X, Hu F, Lu XB, Chuang JC. Human exposure and dosimetry of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urine from Xuan Wei, China with high lung cancer mortality associated with exposure to unvented coal smoke. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:3031–3036. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.12.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tung YF, Ko JF, Liang YF, Yin LF, Pu YF, Lin P. Cooking oil fume-induced cytokine expression and oxidative stress in human lung epithelial cells. Environ Res. 2001;87:47–54. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu SF, Yen GF, Sheu F. Mutagenicity and identification of mutagenic compounds of fumes obtained from heating peanut oil. J Food Prot. 2001;64:240–245. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shields PG, Xu GX, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Trivers GE, Pellizzari ED, Qu YH, Gao YT, Harris CC. Mutagens from heated Chinese and U.S. cooking oils. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;87:836–841. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.11.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dung CH, Wu SC, Yen GC. Genotoxicity and oxidative stress of the mutagenic compounds formed in fumes of heated soybean oil. sunflower oil and lard. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.08.019. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Smith KR. Indoor Air Pollution From Household Fuel Combustion in China: A Review. 2005. The 10th International Conference on Indoor Air Quality and Climate; 9-4-2005; Ref Type: Conference Proceeding. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannervik B, Awasthi YC, Board PG, Hayes JD, Di Ilio C, Ketterer B, Listowsky I, Morgenstern R, Muramatsu M, Pearson WR. Nomenclature for human glutathione transferases. Biochem J. 1992;282(Pt 1):305–306. doi: 10.1042/bj2820305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parl FF. Glutathione S-transferase genotypes and cancer risk. Cancer letters. 2005;221:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norppa H, Hirvonen A, Jarventaus H, Uuskula M, Tasa G, Ojajarvi A, Sorsa M. Role of GSTT1 and GSTM1 genotypes in determining individual sensitivity to sister chromatid exchange induction by diepoxybutane in cultured human lymphocytes. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1261–1264. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.6.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolt HM, Thier R. Relevance of the deletion polymorphisms of the glutathione S-transferases GSTT1 and GSTM1 in pharmacology and toxicology. Curr Drug Metab. 2006;7:613–628. doi: 10.2174/138920006778017786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirvonen A. Polymorphisms of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes and susceptibility to cancer. Environmental health perspectives. 1999;107(Suppl 1):37–47. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rebbeck TR. Molecular epidemiology of the human glutathione S-transferase genotypes GSTM1 and GSTT1 in cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:733–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye Z, Song H, Higgins JP, Pharoah P, Danesh J. Five glutathione s-transferase gene variants in 23,452 cases of lung cancer and 30,397 controls: meta-analysis of 130 studies. PLoS Med. 2006 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030091. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benhamou S, Lee WJ, Alexandrie AK, Boffetta P, Bouchardy C, Butkiewicz D, Brockmoller J, Clapper ML, Daly A, Dolzan V, Ford J, Gaspari L, Haugen A, Hirvonen AF, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Kalina I, Kihara M, Kremers P, Le Marchand L, London SJ, Nazar-Stewart V, Onon-Kihara M, Rannug A, Romkes M, Ryberg D, Seidegard J, Shields P, Strange RC, Stucker I, To-Figueras J, Brennan P, Taioli E. Meta- and pooled analyses of the effects of glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphisms and smoking on lung cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1343–1350. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.8.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raimondi S, Paracchini V, Autrup H, Barros-Dios JM, Benhamou S, Boffetta P, Cote ML, Dialyna IA, Dolzan V, Filiberti R, Garte S, Hirvonen A, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Imyanitov EN, Kalina I, Kang D, Kiyohara C, Kohno T, Kremers P, Lan Q, London S, Povey AC, Rannug A, Reszka E, Risch A, Romkes M, Schneider J, Seow A, Shields PG, Sobti RC, Sorensen M, Spinola M, Spitz MR, Strange RC, Stucker I, Sugimura H, To-Figueras J, Tokudome S, Yang P, Yuan JM, Warholm M, Taioli E. Meta- and Pooled Analysis of GSTT1 and Lung Cancer: A Huge-GSEC Review. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raimondi S, Boffetta P, Anttila S, Brockmoller J, Butkiewicz D, Cascorbi I, Clapper ML, Dragani TA, Garte S, Gsur A, Haidinger G, Hirvonen A, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Kalina I, Lan Q, Leoni VP, Le Marchand L, London SJ, Neri M, Povey AC, Rannug A, Reszka E, Ryberg D, Risch A, Romkes M, Ruano-Ravina A, Schoket B, Spinola M, Sugimura H, Wu X, Taioli E. Metabolic gene polymorphisms and lung cancer risk in non-smokers. An update of the GSEC study. Mutation research. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.06.002. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cranor C. Scientific inferences in the laboratory and the law. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(Suppl 1):S121–S128. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Deng Y, Li L, Kuriki K, Ding J, Pan X, Zhuge X, Jiang J, Luo C, Lin P, Tokudome S. Association of GSTM1, CYP1A1 and CYP2E1 genetic polymorphisms with susceptibility to lung adenocarcinoma: a case-control study in Chinese population. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:448–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Safe S. Endocrine disruptors and human health: is there a problem. Toxicology. 2004;205:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Easterling TR, Martin DP. Risk of uterine rupture during labor among women with a prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:3–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fee E, Brown TM. “A doctors’ war”: expert witnesses in late 19th-century America. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(Suppl 1):S28–S29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lan Q, He X, Costa DJ, Tian L, Rothman N, Hu G, Mumford JL. Indoor coal combustion emissions, GSTM1 and GSTT1 genotypes, and lung cancer risk: a case-control study in Xuan Wei, China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:605–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pisani P, Srivatanakul P, Randerson-Moor J, Vipasrinimit S, Lalitwongsa S, Unpunyo P, Bashir S, Bishop DT. GSTM1 and CYP1A1 polymorphisms, tobacco, air pollution, and lung cancer: a study in rural Thailand. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:667–674. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen HC, Cao YF, Hu WX, Liu XF, Liu QX, Zhang J, Liu J. Genetic polymorphisms of phase II metabolic enzymes and lung cancer susceptibility in a population of Central South China. Dis Markers. 2006;22:141–152. doi: 10.1155/2006/436497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan-Yeung M, Tan-Un KC, Ip MS, Tsang KW, Ho SP, Ho JC, Chan H, Lam WK. Lung cancer susceptibility and polymorphisms of glutathione-S-transferase genes in Hong Kong. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2004;45:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang XR, Wacholder S, Xu Z, Dean M, Clark V, Gold B, Brown LM, Stone BJ, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Caporaso NE. CYP1A1 and GSTM1 polymorphisms in relation to lung cancer risk in Chinese women. Cancer letters. 2004;214:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J, Deng Y, Cheng J, Ding J, Tokudome S. GST genetic polymorphisms and lung adenocarcinoma susceptibility in a Chinese population. Cancer letters. 2003;201:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lan Q, Chapman RS, Schreinemachers DM, Tian L, He X. Household stove improvement and risk of lung cancer in Xuanwei, China. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94:826–835. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu ZY, Blot WJ, Xiao HP, Wu A, Feng YP, Stone BJ, Sun J, Ershow AG, Henderson BE, Fraumeni JF., Jr Smoking, air pollution, and the high rates of lung cancer in Shenyang, China. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1989;81:1800–1806. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.23.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou BS, Wang TJ, Guan P, Wu JM. Indoor air pollution and pulmonary adenocarcinoma among females: a case-control study in Shenyang, China. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:1253–1259. doi: 10.3892/or.7.6.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu ZY, Blot WJ, Xiao HP, Wu A, Feng YP, Stone BJ, Sun J, Ershow AG, Henderson BE, Fraumeni JF., Jr Smoking, air pollution, and the high rates of lung cancer in Shenyang, China. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1989;81:1800–1806. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.23.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu ZY, Blot WJ, Li G, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Zhao DZ, Stone BJ, Yin Q, Wu A, Henderson BE, Guan BP. Environmental determinants of lung cancer in Shenyang. China, IARC Sci Publ; 1991. pp. 460–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sajjakulnukit B, Yingyuad R, Maneekhao V, Pongnarintasut V, Bhattacharya SC, Salam PA. Assessment of sustainable energy potential of non-plantation biomass resources in Thailand. Biomass and Energy. 2005;29 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ko YC, Lee CH, Chen MJ, Huang CC, Chang WY, Lin HJ, Wang HZ, Chang PY. Risk factors for primary lung cancer among non-smoking women in Taiwan. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:24–31. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu IT, Chiu YL, Au JS, Wong TW, Tang JL. Dose-response relationship between cooking fumes exposures and lung cancer among Chinese nonsmoking women. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4961–4967. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan-Yeung M, Koo LC, Ho JC, Tsang KW, Chau WS, Chiu SW, Ip MS, Lam WK. Risk factors associated with lung cancer in Hong Kong. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2003;40:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sundberg K, Johansson AS, Stenberg G, Widersten M, Seidel A, Mannervik B, Jernstrom B. Differences in the catalytic efficiencies of allelic variants of glutathione transferase P1-1 towards carcinogenic diol epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:433–436. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hecht SS, Carmella SG, Yoder A, Chen M, Li ZZ, Le C, Dayton R, Jensen J, Hatsukami DK. Comparison of polymorphisms in genes involved in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism with urinary phenanthrene metabolite ratios in smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1805–1811. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thier R, Bruning T, Roos PH, Rihs HP, Golka K, Ko Y, Bolt HM. Markers of genetic susceptibility in human environmental hygiene and toxicology: the role of selected CYP, NAT and GST genes. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2003;206:149–171. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warholm M, Guthenberg C, Mannervik B. Molecular and catalytic properties of glutathione transferase mu from human liver: an enzyme efficiently conjugating epoxides. Biochemistry. 1983;22:3610–3617. doi: 10.1021/bi00284a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeMarini DM, Landi S, Tian D, Hanley NM, Li X, Hu F, Roop BC, Mass MJ, Keohavong P, Gao W, Olivier M, Hainaut P, Mumford JL. Lung tumor KRAS and TP53 mutations in nonsmokers reflect exposure to PAH-rich coal combustion emissions. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6679–6681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu K, Li X, Hu F. [A study on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adduct in lung cancer patients exposed to indoor coal-burning smoke] Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine] 1997;31:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mumford JF, Lee XF, Lewtas JF, Young TF, Santella RM. DNA adducts as biomarkers for assessing exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in tissues from Xuan Wei women with high exposure to coal combustion emissions and high lung cancer mortality. Environmental health perspectives. 1993;99:83–87. doi: 10.1289/ehp.939983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kato S, Bowman ED, Harrington AM, Blomeke B, Shields PG. Human lung carcinogen-DNA adduct levels mediated by genetic polymorphisms in vivo. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1995;87:902–907. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.12.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]