SUMMARY

Activation of both mTOR and its downstream target, S6K1 (p70 S6 kinase) have been implicated to affect cardiac hypertrophy. Our earlier work, in a feline model of 1–48 h pressure overload, demonstrated that mTOR/S6K1 activation occurred primarily through a PKC/c-Raf pathway. To further delineate the role of specific PKC isoforms on mTOR/S6K1 activation, we utilized primary cultures of adult feline cardiomyocytes in vitro and stimulated with endothelin-1 (ET-1), phenylephrine (PE), TPA, or insulin. All agonist treatments resulted in S2248 phosphorylation of mTOR and T389 and S421/T424 phosphorylation of S6K1, however only ET-1 and TPA-stimulated mTOR/S6K1 activation was abolished with infection of a dominant negative adenoviral c-Raf (DN-Raf) construct. Expression of DN-PKCε blocked ET-1-stimulated mTOR S2448 and S6K1 S421/T424 and T389 phosphorylation but had no effect on insulin-stimulated S6K1 phosphorylation. Expression of DN-PKCδ or pretreatment of cardiomyocytes with rottlerin, a PKCδ specific inhibitor, blocked both ET-1 and insulin stimulated mTOR S2448 and S6K1 T389 phosphorylation. However, treatment with Gö6976, a specific classical PKC (cPKC) inhibitor did not affect mTOR/S6K1 activation. These data indicate that: (i) PKCε is required for ET-1-stimulated T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1, (ii) both PKCε and PKCδ are required for ET-1-stimulated mTOR S2448 and S6K1 T389 phosphorylation, (iii) PKCδ is also required for insulin-stimulated mTOR S2448 and S6K1 T389 phosphorylation. Together, these data delineate both distinct and combinatorial roles of specific PKC isoforms on mTOR and S6K1 activation in adult cardiac myocytes following hypertrophic stimulation.

Keywords: Cardiomyocytes, PKC, mTOR, S6K1, endothelin-1, phenylephrine, hypertrophy

INTRODUCTION

In response to increased mechanical (hemodynamic) load, either mediated through pressure or volume overload, the heart compensates through hypertrophic myocyte growth. Although initially compensatory by normalizing wall stress, this growth process often progresses into failure when it compromises filling capacity or contractile function of the heart (1, 2). The major component underlying this process is the coupling of increased hemodynamic load to intracellular signaling that causes hypertrophic growth. Although numerous cellular signaling mechanisms have been implicated in this process, the complex interplay has yet to be completely understood.

Both mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and one of its key downstream targets, p70 S6 kinase (S6K1) have been extensively studied for their effects during cardiac hypertrophy. For example, in vivo treatment with rapamycin (a specific inhibitor of mTOR) affects cardiac cell size and contractile function and has been shown to blunt the increase in heart weight and cell size during aortic band-induced pressure overload in rodents (3, 4). Rapamycin has also been shown to reduce preexisting hypertrophic myocyte growth even when administered 1 week after aortic banding (5). Therefore mTOR represents a critical mediator of the hypertrophic growth process.

In the mTOR-mediated signaling pathway, S6K1 is thought to be a key downstream regulator of the overall cellular growth response. For example, gene deletion studies in Drosophilia demonstrated a semi-lethal phenotype with only a few surviving adults. These mutant flies exhibit a severely reduced body size attributed to a decrease in cell size rather than a decrease in cell number (6). Furthermore, disruption of the S6K1 gene in mice produced a phenotype characterized by reduced body size that was attributed to a decrease in cell size rather than a decrease in cell number (7). One of the most extensively studied downstream effects of S6K1 is on the phosphorylation of the S6 protein and its contribution to 5′-TOP (5′-terminal oligopyrimidine) mRNA translation (8). In addition to S6 protein, several new targets of S6K1-mediated phosphorylation that may significantly contribute to hypertrophic growth have been discovered, including transcription factors such as c-AMP response element modulator (9), elongation factors such as eEF2K (10), initiation factors such as eIF4B (11), and potential cell size regulators such as S6K1 Aly/Ref like target (SKAR) (12).

For activation, both mTOR and S6K1 undergo phosphorylation at multiple sites. In the case of mTOR, formation of multiprotein complexes that are either sensitive or insensitive to rapamycin inhibition have been demonstrated (13, 14), and only the rapamycin-sensitive complexes are responsible for phosphorylation and activation of S6K1 (15). Various studies in the heart and in other muscle types demonstrate that phosphorylation on the S2448 site of mTOR is indicative of its activation (4, 16–19). S6K1 activation, in contrast, revolves around a complex series of multiple phosphorylations that regulate its kinase activity (20, 21). At least eight phosphorylation sites have been identified and are divided into two sets. The first set, which contains sites important for kinase activity and are sensitive to rapamycin, is situated in the linker region (Thr-389 and Ser-404) and the catalytic domain (Thr-229 and Ser-371) of S6K1 (20, 22). Thr-389 phosphorylation, which occurs during mitogenic stimulation and is sensitive to rapamycin, is required for subsequent Thr-229 phosphorylation and increased kinase activity. The second set of phosphorylation sites involves four different residues in the pseudosubstrate domain: Ser-411, Ser-418, Thr-421, and Ser-424. Phosphorylation of these residues are thought to be important for subsequent Thr-389 phosphorylation and for kinase function (23).

Three major independent signaling pathways (24–28) utilize PI3K, PKA and PKC for S6K1 activation, but our previous work (29, 30) has determined that during the early phase of in vivo induced pressure-overload hypertrophy, a PKC-dependent c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway that does not depend on PI3K or PKA, predominantly contributes to mTOR and S6K1 activation. The PKC family of phospholipid-dependent Ser/Thr kinases includes at least 11 mammalian isoforms, and in adult cardiomyocytes, both the classical (calcium-dependent) isoforms (cPKC), PKCα and PKCβ, as well as the novel (calcium-independent) isoforms (nPKC), PKCε and PKCδ, are the predominantly expressed (31, 32). Our initial in vitro studies (29, 30) utilized TPA, a non-selective PKC activator, to replicate the activation profile of mTOR and S6K1 seen in vivo, but the use of TPA precluded any conclusions regarding individual PKC isoform contributions to their activation. Furthermore, in a study conducted by Wang et al. 2001, the contribution of the nPKC isoforms to S6K1 activation in neonatal cardiocytes was assayed during adrenergic stimulation, although the role of individual PKC isoforms in mediating specific phosphorylations on S6K1 necessary for its activation was not addressed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to characterize specific PKC isoform(s) that mediate mTOR/S6K1 activation through the involvement of a c-Raf/MEK/ERK-dependent, but PI3K-independent pathway. In the present study we demonstrate that ET-1 mimics our in vivo PKC-mediated mTOR/S6K1 activation. Using this agonist, we further demonstrate that both PKCε and PKCδ, but not the classical isoforms PKCα and PKCβ, contribute to mTOR/S6K1 activation using both distinct and combinatorial pathways for mediating mTOR/S6K1 activation. Furthermore, PKCδ is required even during PI3K-mediated mTOR/S6K1 activation, as observed during insulin stimulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Protease inhibitors: 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzene sulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin-A and E-64 (trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucylamido-(4-guanidino) butane) and phosphatase inhibitors: okadaic acid, β-glycerolphosphate, sodium orthovanadate, and EGTA were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Wortmannin, ET-1, TPA, rottlerin and Gö6976 were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). PE and insulin were also obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO).

Antibodies

Antibodies used for Western Blot analysis were obtained from these vendors (used at the following titers): S6K1 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA (1:10,000); phospho-specific Thr-421/Ser-424 (1:5000), and Thr-389 (1:5000) S6K1, Ser-2448 mTOR (1:1000), and phospho and regular ERK (1:5000) from Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; and mTOR (1:2000) from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA.

Adult cardiomyocyte culture model

Adult feline cardiomyocytes were isolated and cultured on laminin coated culture trays as described previously (2). Isolated cardiomyocytes were suspended in a 1.8 mM calcium containing mitogen-free M-199 medium at pH 7.4. For experimental conditions, cells were plated at a density of 1.0×105 cells/35 mm dish and incubated at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2.

Stimulation of PKC and S6K1 in cultured cardiomyocytes

Freshly isolated adult feline cardiomyocytes were cultured overnight and stimulated with 400 nM ET-1, 100 μM PE, 200 nM TPA, or 100 nM insulin in the presence or absence of various pharmacologic inhibitors. Untreated cells served as controls. For treatment with pharmacologic inhibitors, cells were pre-incubated for 1 h and then stimulated for various time periods as indicated in the figure legends. For adenoviral expression, freshly isolated cardiomyocytes were plated on laminin-coated trays and incubated for 4 h prior to infection. Cells were then incubated overnight in serum-free M-199 media containing the adenovirus at m.o.i. (multiplicity of infection) levels of 200 for DN-Raf (C4B), 75 for DN-PKCε, and 150 for DN-PKCδ. Cells infected with an equal m.o.i. of galactosidase (β gal) adenovirus served as control. The generation of DN-Raf and DN-PKCε has been described previously (30, 33) and the DN-PKCδ adenovirus was obtained from Dr. Williams’ laboratory (34). The media was replaced after 24 h and allowed to incubate for an additional 24 h prior to agonist stimulation.

Western blotting

Triton X-100 soluble fraction of cardiomyocytes was prepared following extraction with lysis buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2% Triton X-100, 10 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.02 μM okadaic acid, 0.5 mM EGTA and 2 μM E-64). Cells in the lysis buffer were passed through an insulin-syringe ten times and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min. An equal volume of SDS-sample buffer was then added to the supernatant and boiled for 5 min. The protein concentration was determined using BCA reagent (Pierce) and adjusted for comparison. Approximately 10 μg of protein from each sample was resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred electrophoretically to Immobilion-P membranes. After blocking the membranes for 1 h using 5 % milk and 1% BSA in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl and 0.1% Tween-20), primary antibodies diluted in TBST were added and incubated overnight at 4° C. Membranes were washed three times for 5 minutes each in TBST and incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody in TBST buffer for 1 h at room temperature. After five final washes for five minutes each, proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence, ECL (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA) and X-OMAT imaging film (Kodak). Phosphorylation and the total level of each signaling intermediate were determined by Western blot analysis followed by densitometry using NIH Image J program. The phosphorylation of each protein was normalized to their respective total protein level, and the normalized value for control was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 and used for comparison of all other treatment conditions. The summary data for all the experiments are expressed in graphical form as means ± S.E. Differences between the groups were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey test, and a value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Stimulation of PKC-mediated S6K1 activation in adult cardiomyocytes

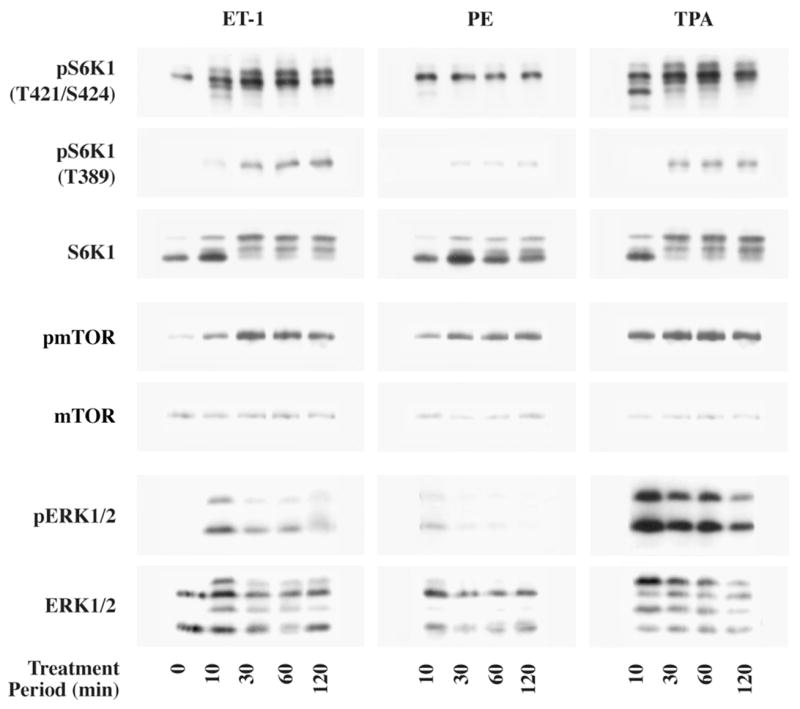

Our previous in vivo (29) studies identified that a PKC-mediated pathway contributes to the activation of mTOR and its downstream target S6K1 during the early period (within 1 h) of right ventricular pressure overload (RVPO) in the adult feline myocardium. In the present study, we delineated the role of individual PKC isoforms during mTOR/S6K1 activation by mimicking our in vivo data using cardiac hypertrophic agonists, known to activate PKC pathways during hypertrophy, on isolated adult cardiomyocytes in culture. While agonists like angiotensin II, and Insulin have been shown to stimulate cardiocytes in culture, they primarily utilize PI3K (30, 35). However, both ET-1 and PE have been shown to be important during hypertrophic growth of the myocardium and specifically PE has been used to stimulate PKCε and PKCδ in neonatal rat cardiocytes (36, 37). Therefore, we sought to determine whether ET-1 or PE stimulation in culture would replicate our in vivo PKC/c-Raf/ERK-dependent mTOR and S6K1 activation. We assayed for phosphorylation of mTOR at S2448, S6K1 at T389, and S6K1 at T421/S424 which can appear in multiple bands as published previously (30, 38). Figure 1 shows that stimulation of isolated cardiomyocytes with ET-1 and to a lesser extent PE increased the level of S6K1 T421/S424 and T389 phosphorylation and mTOR S2448 phosphorylation. Both ET-1 and PE exhibit a similar trend to that of TPA in the time course of activation of mTOR and S6K1. Both phosphorlyation of S6K1 at T421/S424 and mTOR at S2448 by all these agonists occurred as early as 10 min and the activation was sustained up to 2 h. Similarly the T389 phosphorylation of S6K was increased after 30 min of treatment and was also sustained up to 2 h. The increase in T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 was also reflected in the retarded electrophoretic mobility (band shift) of S6K1 (visualized by the total S6K1 antibody as multiple bands ~70 kDa), which also appears at 30 min and is sustained through 2 h.

Fig 1. Agonist stimulation of S6K1, mTOR and ERK in an in vitro feline adult cardiomyocyte culture model.

Freshly isolated feline adult cardiomyocytes were cultured on laminin-coated plates. A time course of stimulation using 400 nM ET-1, 100 μM PE and 200 nM TPA was performed. Untreated cells served as controls. Cells were harvested as described in the Methods section. For each experimental condition, an equal amount of protein per sample (10 μg) was used for Western blot analysis of S6K1, mTOR and ERK using non-selective and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies. Results were confirmed in three additional experiments.

Since our previous in vivo studies (30) demonstrated that a c-Raf/MEK/ERK-dependent pathway controls both mTOR and S6K1 phosphorylation/activation, we also evaluated the effects of these agonists on the stimulation of ERK. ET-1, TPA and to a lesser extent PE, stimulated ERK phosphorylation at 10 min that remained up to 2 h. These initial studies established the appropriate dose and duration of ET-1, PE and TPA treatments of adult cardiomyocytes to stimulate mTOR, S6K1 and ERK phosphorylation.

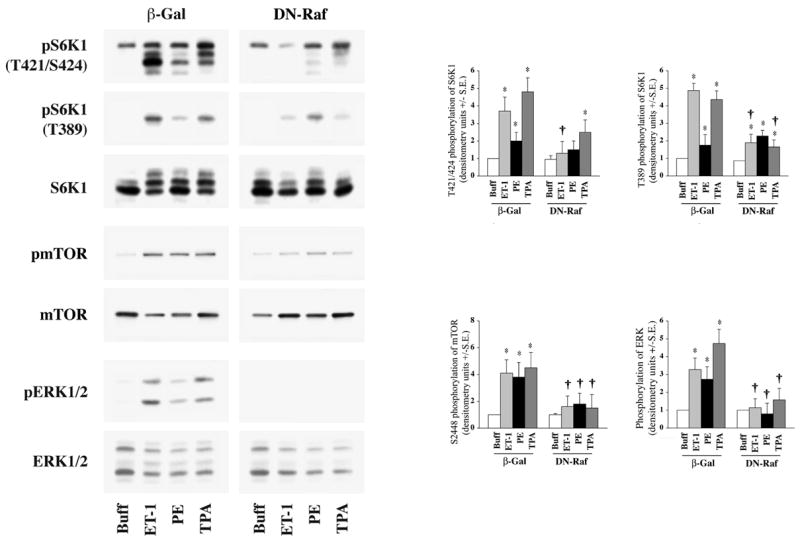

Effect of dominant negative c-Raf (DN-Raf) expression on agonist stimulated mTOR, S6K1 and ERK activation

We first sought to determine if the c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is necessary for ET-1 and PE stimulation of mTOR and S6K1 activation. Cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviruses to express either β-gal or a DN-Raf isoform, thus blocking the c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway (29). Following infection, cardiomyocytes were then stimulated with ET-1, PE or TPA. The ET-1 and TPA-mediated phosphorylation of mTOR at S2448 and S6K1 at T421/S424 and T389 were significantly reduced in DN-Raf expressing cardiomyocytes (Figure-2). However, DN-Raf expression did not block the T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 during PE stimulation. Furthermore, the phosphorylation of ERK stimulated by all three agonists was blocked during DN-Raf expression. These data show that ET-1 requires a c-Raf-mediated pathway for mTOR, S6K1 and ERK activation and provide evidence that perhaps another (c-Raf independent and possibly PI3K-dependent) pathway is utilized at least in part, during PE stimulation.

Fig 2. Effect of DN-Raf expression on agonist-stimulated activation of S6K1, mTOR and ERK in adult cardiomyocytes.

Freshly isolated feline adult cardiomyocytes were cultured on laminin-coated plates. After 4 h culturing period, cells were infected with either β-galactosidase (β-Gal) or DN-Raf expressing adenoviruses as described in the Methods section. Cells were then stimulated with 400 nM ET-1, 100 μM PE and 200 nM TPA for 60 min, and untreated cells served as controls. Cells were then processed for Western blot analysis with non-selective and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies. Phosphorylation levels of S6K1, mTOR and ERK were assessed by densitometry, and the phosphorylation of each protein was normalized to their respective total protein level. The normalized value for control was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 and used for comparison of all other treatment conditions. The summary data of three experiments is presented in a histogram as means +/− standard error (side panels). * represents p<0.05 as compared to buffer control, † represents p<0.05 as compared to matched stimulation in β-gal expressing cardiomyocytes.

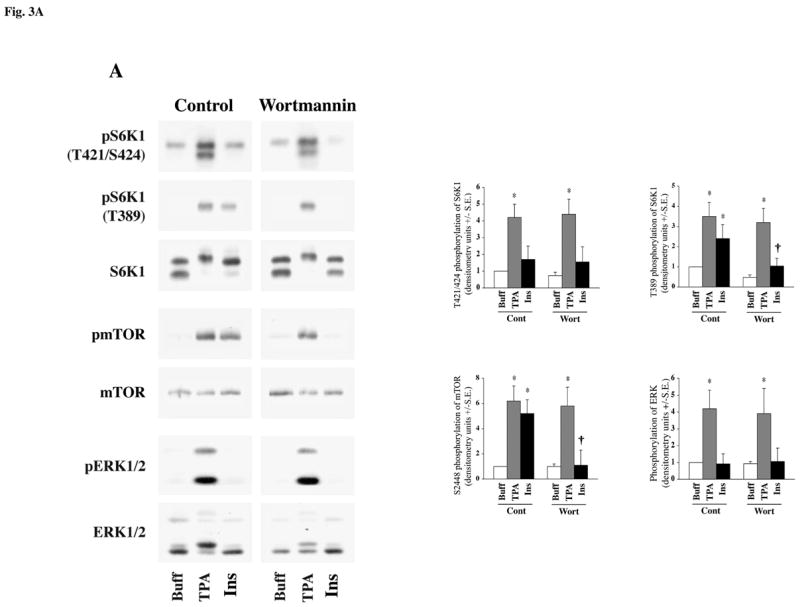

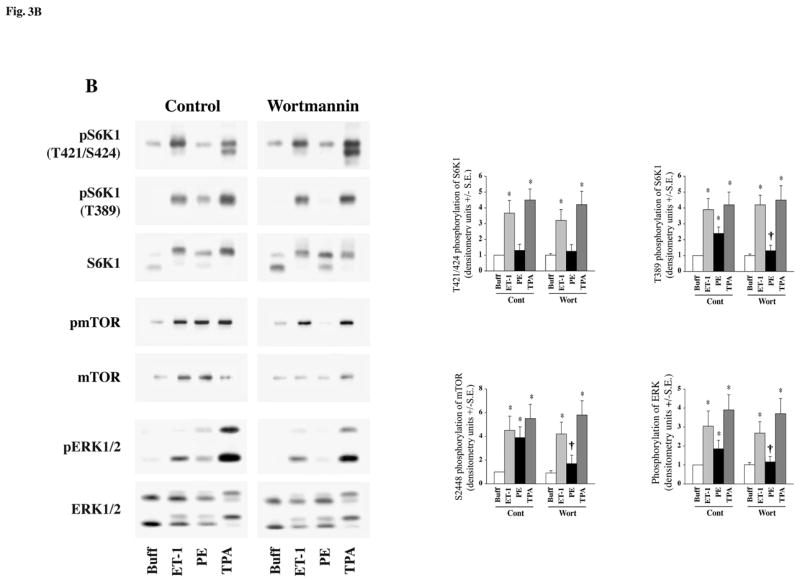

Effect of wortmannin on agonist stimulated mTOR, S6K1 and ERK activation

To confirm that ET-1 but not PE replicates our in vivo data where activation of mTOR, S6K1 and ERK is mediated primarily through a PKC-mediated pathway, independent of PI3K, we tested agonist stimulation in cardiomyocytes pretreated with wortmannin (a specific pharmacologic inhibitor of PI3K). To first ascertain the correct dosing of wortmannin to specifically block the PI3K pathway, we tested the effect of wortmannin on insulin versus TPA stimulation (Figure-3A). We sought to use a dose of wortmannin that would effectively block insulin (PI3K-dependent) stimulation of mTOR and S6K1 while leaving the PKC-mediated (PI3K-independent) stimulation by TPA, unaffected. Recent studies (39) have utilized wortmannin at a dose of 30 nm, however pretreatment of cardiomyocytes in our studies with 100 nM wortmannin specifically blocked insulin-stimulated mTOR and S6K1 activation and left TPA stimulated activation of mTOR, S6K1 or ERK unaffected. Having determined that wortmannin blocked only the PI3K-dependent pathway, we next analyzed which of the two agonists, ET-1 or PE, mediates mTOR, S6K1 and ERK activation via a PI3K-independent pathway.

Fig 3. Effect of Wortmannin on agonist-stimulated activation of S6K1, mTOR and ERK in adult cardiomyocytes.

Freshly isolated feline adult cardiomyocytes were cultured on laminin-coated plates. The cultures were pre-incubated for 1 h with Wortmannin at 100 nm prior to stimulation. Cells were then stimulated with 200 nM TPA and 100 nM insulin (A) or 400 nM ET-1, 100 μM PE and 200 nM TPA (B) for 60 min. Cells were then processed for Western blot analysis with non-selective and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies. Phosphorylation levels of S6K1, mTOR and ERK were assessed by densitometry, and the phosphorylation of each protein was normalized to their respective total protein level. The normalized value for control was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 and used for comparison of all other treatment conditions. The summary data of four experiments is presented in a histogram as means +/− standard error (side panels). * represents p<0.05 as compared to buffer control, † represents p<0.05 as compared to matched stimulation with no inhibitor.

Whereas pretreatment of cardiomyocytes with 100 nm wortmannin did not affect the ET-1 or TPA-stimulated S6K1 and mTOR phosphorylation, it did block PE stimulation of mTOR and S6K1 phosphorylation at S2448 and T389 sites, respectively (Figure-3B). Therefore, ET-1 and the positive control TPA, stimulate mTOR and S6K1 activation primarily independent of PI3K, whereas PE-stimulated activation is dependent on PI3K. Thus, ET-1 utilizes a c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway for activation of mTOR and S6K1, and therefore, mimics our previous in vivo pressure overload studies and in vitro TPA-stimulated studies in feline cardiomyocytes (30). Identification of ET-1, as a specific agonist for mTOR/S6K1 activation that proceeds independent of PI3K, was crucial for subsequent experiments while ascertaining the role of specific PKC isoforms during this activation process.

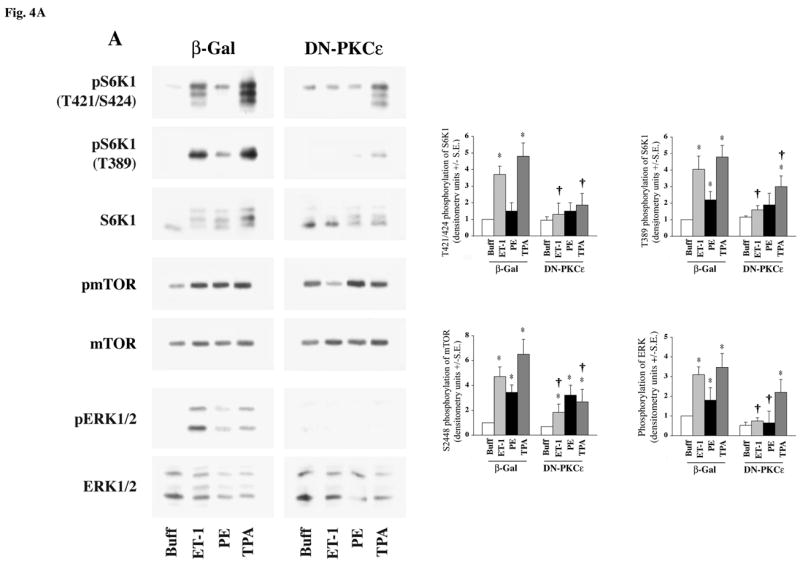

Effect of DN-PKCε expression on agonist stimulated mTOR, S6K1 and ERK activation

To determine the contribution of individual PKC isoforms on mTOR and S6K1 activation, we first tested the role of PKCε. PKCε is a member of the novel PKC isoform family that does not require calcium for its activation and is known to be expressed in the heart (31, 32, 40). We used adenoviral-mediated expression of a dominant negative PKCε (DN-PKCε) isoform (33) in cardiomyocytes and stimulated with ET-1, PE or TPA (Figure-4A). In cardiomyocytes expressing DN-PKCε, the ET-1-stimulated phosphorylation of mTOR (S2448), S6K1 (T421/S424 and T389), and ERK were significantly reduced, and this trend was reflected in the loss of the retarded electrophoretic mobility (band shifting) of S6K1. In the case of TPA, which stimulates multiple isoforms of PKC, only a partial effect was observed on the loss of T389 phosphorylation in DN-PKCε expressing cells. Importantly, except for the loss of ERK phosphorylation, DN-PKCε expression did not significantly affect PE-stimulated mTOR and S6K1 phosphorylation. Overall, these data (Figure-4A) clearly show that PKCε is a critical signaling intermediate during ET-1-stimulated ERK, mTOR and S6K1 phosphorylation.

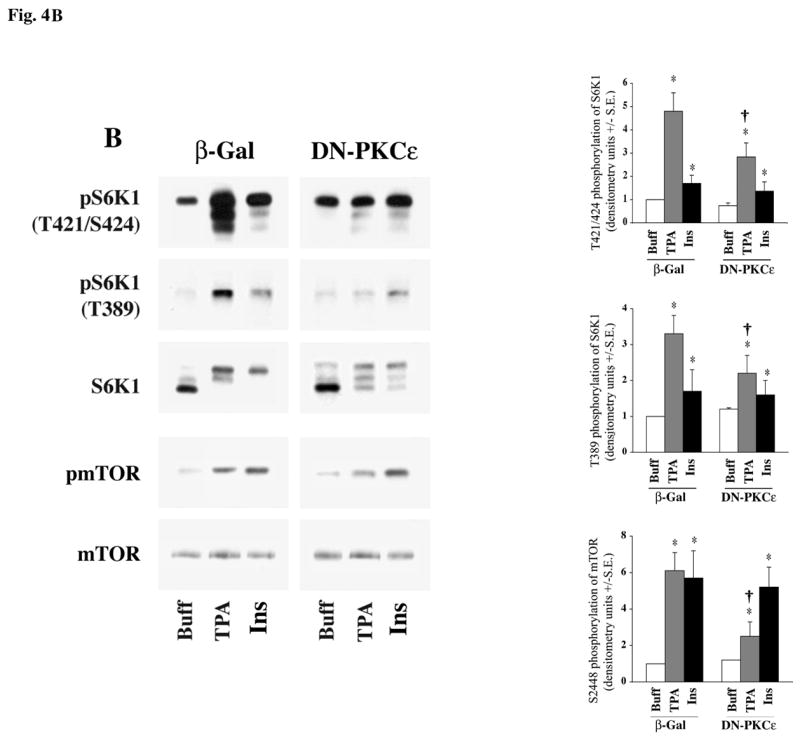

Fig 4. Effect of DN-PKCε expression on agonist-stimulated activation of S6K1, mTOR and ERK in adult cardiomyocytes.

Freshly isolated feline adult cardiomyocytes were cultured on laminin-coated plates. After 4 h culturing period, cells were infected with β-galactosidase (βGal), and DN-PKCε expressing adenoviruses for experiments in (A & B) as described in the Methods section. Cells were then stimulated with 400 nM ET-1, 100 μM PE and 200 nM TPA (A) or 200 nM TPA and 100 nM insulin (B) for 60 min. Cells were then processed for Western blot analysis with non-selective and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies. Phosphorylation levels of S6K1, mTOR and ERK were assessed by densitometry, and the phosphorylation of each protein was normalized to their respective total protein level. The normalized value for control was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 and used for comparison of all other treatment conditions. The summary data of three experiments is presented in a histogram as means +/− standard error (side panels). * represents p<0.05 as compared to buffer control, † represents p<0.05 as compared to matched stimulation in β-gal expressing cardiomyocytes.

To confirm the specificity of DN-PKCε virus, we tested the effect of expression of DN-PKCε on mTOR/S6K1 activation stimulated by insulin (PI3K-dependent) as compared with TPA stimulation (PI3K-independent). As shown in Figure 4B, insulin-stimulated activation/phosphorylation of both mTOR and S6K1 was not blocked by the expression of DN-PKCε, although phosphorylation of mTOR and S6K1 during TPA stimulation was significantly reduced. Thus, during expression of this PKC dominant negative isoform, there is no confounding crossover effect on the PI3K-mediated mTOR/S6K1 activation. Overall, these studies demonstrate that ET-1-stimulated mTOR/S6K1 and ERK activation proceeds independent of PI3K (Figure-3B), and requires PKCε (Figure-4A). Furthermore, these data also demonstrate that PE stimulation of mTOR and S6K1 is only partially dependent on PKCε activation, and requires PI3K-dependent activation (Figure-3B).

Importance of PKCδ in mTOR and S6K1 phosphorylation/activation

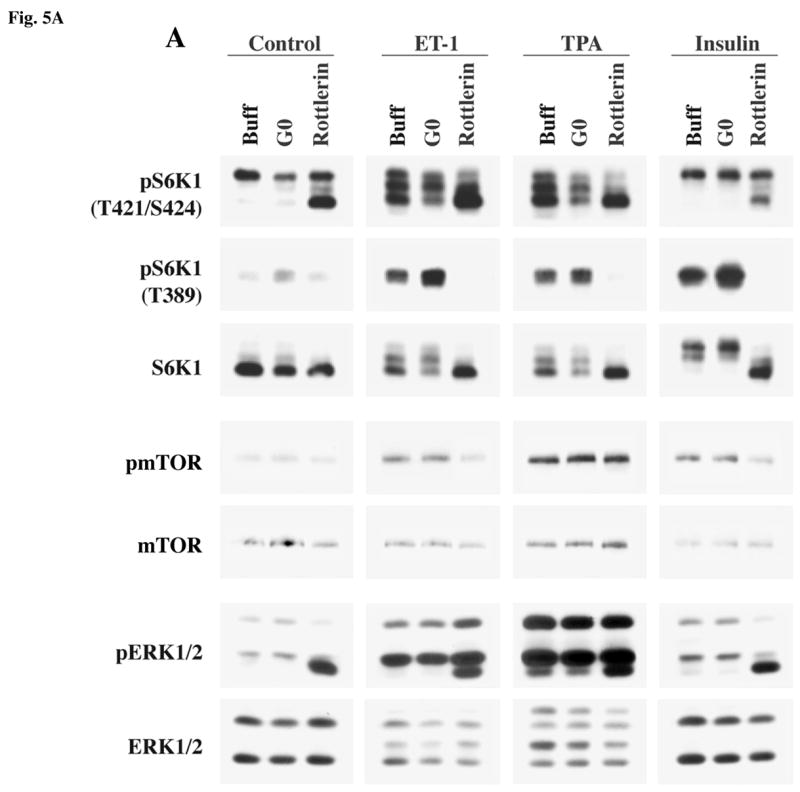

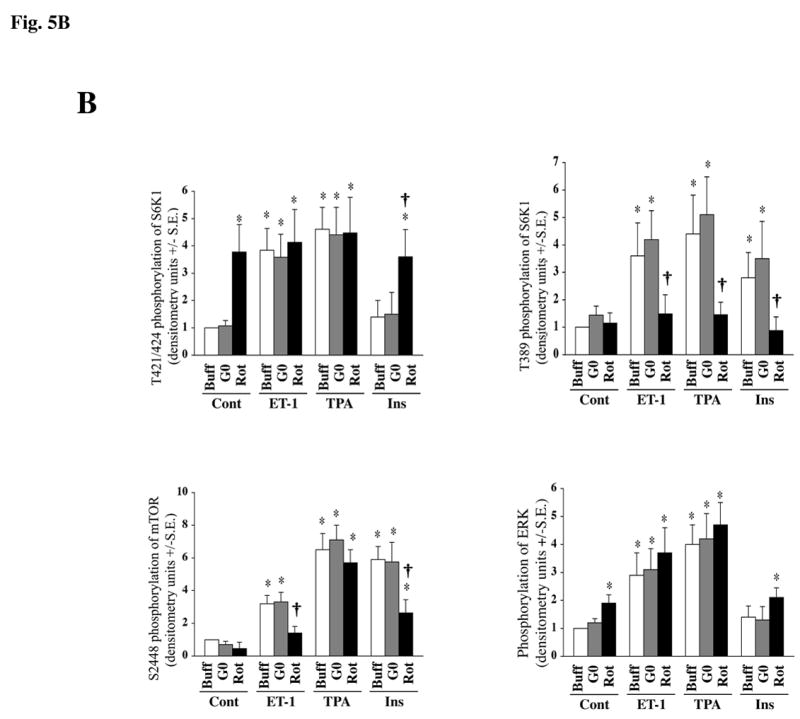

Our studies demonstrate that PKCε plays a major role in ET-1 stimulated activation of S6K1, mediated through the c-Raf/MEK/ERK and mTOR pathways. Since adult cardiomyocytes express multiple isoforms of PKC (31, 40), including classical isoforms, PKCα and PKCβ along with the other novel family member, PKCδ, and since a recent study (41) specifically demonstrated an important role for PKCδ during S6K1 activation by PE in adult rat cardiomyocytes, we next explored the importance of these PKC isoforms during PI3K-dependent and -independent stimulation of mTOR/S6K1 activation. For this, we first used the commercially available pharmacological inhibitors, Gö6976 and rottlerin to specifically block PKCα/β and PKCδ, respectively (42, 43) and studied their effect on the ET-1, TPA and insulin-stimulated mTOR/S6K1 activation (Figure-5A). As in previous experiments, stimulation of adult feline cardiomyocytes with all agonists (ET-1, TPA and insulin) resulted in mTOR, S6K1 and ERK phosphorylation, although to varying degrees (Figure 5A). This activation profile was found to be unaffected in Gö6976 pretreated cells, as shown in the summary data (Figure 5B). Rottlerin pretreatment however blocked mTOR S2448 phosphorylation mediated by ET-1 and insulin, but not TPA. On the other hand, pretreatment of cardiomyocytes with rottlerin showed a differential effect on the phosphorylation of S6K1 at specific sites (Figure-5A). That is, pretreatment of cells with rottlerin increased the basal level of T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1 and phosphorylation/activation of ERK (Figure-5A), while it did not affect the baseline phosphorylation of T389 of S6K1. Importantly, rottlerin blocked T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 during ET-1, TPA and insulin stimulation, and these changes were reflected in the retarded electrophoretic mobility (band shift) of S6K1. All these data were confirmed in multiple experiments and given as summary data (Figure-5B). Overall, these data indicate that PKCδ is required for ET-1-stimulated mTOR S2448 phosphorylation and subsequent S6K1 T389 phosphorylation, while simultaneously leaving ERK and S6K1 T421/S424 phosphorylation unaffected. Also, even during insulin-stimulated (PI3K-dependent) activation, PKCδ is necessary for phosphorylation of mTOR at S2448 and S6K1 at T389 sites.

Fig 5. Effect of blocking PKCα/β and PKCδ isoforms in cardiomyocytes on agonist stimulated activation of S6K1, mTOR and ERK in adult cardiomyocytes.

Freshly isolated feline adult cardiomyocytes were cultured on laminin-coated plates. The cultures were pre-incubated for 1 h with 1 μM Gö6976 or 500 nM rottlerin and then stimulated for 60 minutes with 400 nM ET-1 and 200 nM TPA or 100 nM insulin. Untreated cells were used as controls. Western blot analysis was performed using non-selective and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies (A). Phosphorylation levels of S6K1, mTOR and ERK were assessed by densitometry, and the phosphorylation of each protein was normalized to their respective total protein level. The normalized value for control was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 and used for comparison of all other treatment conditions. The summary data of three experiments is presented in a histogram as means +/− standard error (B). * represents p<0.05 as compared to untreated control, † represents p<0.05 as compared to rottlerin treatment against matched stimulation with no inhibitors.

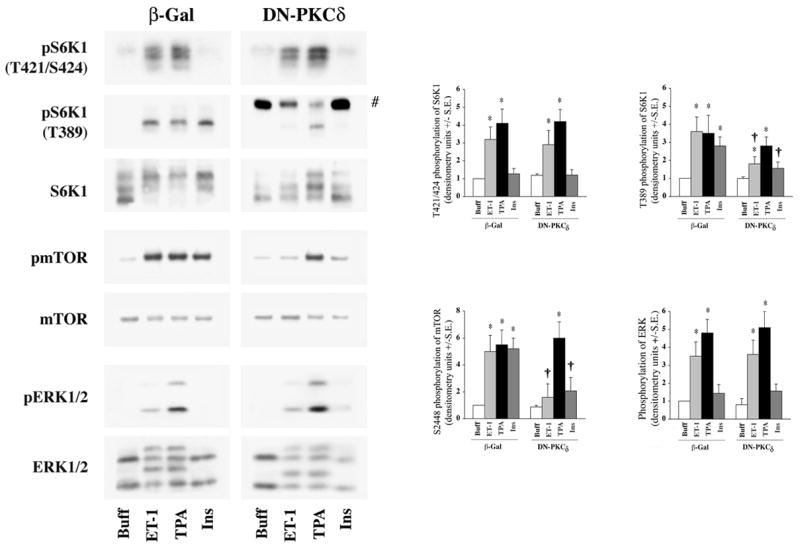

Effect of DN-PKCδ expression on agonist stimulated mTOR, S6K1 and ERK activation

To further confirm that PKCδ is required for mTOR S2448 and S6K1 T389 phosphorylations and to dismiss any non-specific effects caused by rottlerin, we next utilized a dominant negative PKCδ (DN-PKCδ) adenovirus to block PKCδ activity. Unlike rottlerin, expression of DN-PKCδ did not induce a baseline increase in T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1 (Figure-6). Expression of DN-PKCδ also did not affect ET-1, TPA or insulin-stimulated T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1 or ERK1/2 activation. DN-PKCδ expression did, however, block T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 and S2448 phosphorylation of mTOR during ET-1 and insulin stimulation. However, TPA stimulation, which is known to directly stimulate multiple PKC isoforms, was not significantly affected during DN-PKCδ expression. Overall, these data are consistent with our studies using rottlerin, demonstrating that PKCδ is required for both ET-1 and insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of mTOR at S2448 and S6K1 at T389. Thus, during ET-1 and insulin-stimulated mTOR/S6K1 activation, which is mediated by PI3K-independent and -dependent pathways, respectively, PKCδ functions as a common mediator downstream of both pathways (Figures-5 and 6).

Fig 6. Effect of DN-PKCδ expression on agonist-stimulated activation of S6K1, mTOR and ERK in adult cardiomyocytes.

Freshly isolated feline adult cardiomyocytes were cultured on laminin-coated plates. After 4 h culturing period, cells were infected with β-galactosidase (βGal), and DN-PKC expressing adenoviruses as described in the Methods section. Cells were stimulated with 400 nM ET-1, 200 nM TPA or 100 nM insulin for 60 min. Untreated cells served as controls. Cells were then processed for Western blot analysis with non-selective and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies. Phosphorylation levels of S6K1, mTOR and ERK were assessed by densitometry, and the phosphorylation of each protein was normalized to their respective total protein level. The normalized value for control was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 and used for comparison of all other treatment conditions. # represents a non-specific reaction of the S6K1 pT389 antibody in DN-PKC expressing cardiomyocytes. The summary data of three experiments is presented in a histogram as means +/− standard error (side panels). * represents p<0.05 as compared to buffer control, † represents p<0.05 as compared to matched stimulation in β-gal expressing cardiomyocytes.

DISCUSSION

Our earlier studies in pressure-overloaded myocardium (29, 30) indicated that a PI3K independent mechanism initially activates mTOR and S6K1 through the activation of a PKC/c-Raf/MEK/ERK. Furthermore, our earlier in vitro studies, which utilized a global stimulator of PKC, TPA, and a global inhibitor of PKC, BIM, confirmed the importance of a PKC mediated pathway during mTOR and S6K1 activation. These broad-spectrum agents however are not endogenous to the body and are not specific enough to define the role of individual PKC isoforms on mTOR/S6K1 activation. The present study sought to replicate our earlier in vivo findings where PKC activates c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway and causes mTOR/S6K1 activation in a PI3K-independent manner, using agonist stimulation of cardiomyocytes in culture. After characterizing ET-1 as an ideal agonist for stimulation of these pathways, we were able to tease out the specific contributions of individual PKC isoforms on mTOR and S6K1 activation. ET-1 is an endogenously produced G-protein coupled receptor agonist, known to mediate its effects predominantly through PKC activation of the novel isoforms (44). We began using isolated adult feline cardiac myocytes in cell culture and stimulated with ET-1 to replicate our earlier in vivo data (i.e. a PI3K independent PKC/c-Raf/MEK/ERK mediated pathway of mTOR and S6K1 activation). In addition, we used PE, an adrenergic agonist, that has been shown, in other studies, to specifically stimulate both PKCε and PKCδ in neonatal rat cardiocytes in culture (41), and PI3K-dependent pathways (45). Cells were also stimulated with TPA as a positive control for PKC-mediated PI3K-independent activation, and insulin was used as a control for PI3K-dependent activation. We used phosphorylation state-specific antibodies to measure the activation of mTOR and S6K1, including a phospho-S2448 antibody for mTOR, and two independent antibodies against phospho-T389 and phospho-T421/S424 (dual site phosphorylation) for S6K1. In addition, since phosphorylated S6K1 is known to exhibit retarded electrophoretic mobility during SDS-PAGE separation, we analyzed for such changes using a phosphorylation-state independent antibody of S6K1. Herein we show that: (i) ET-1 stimulation of cardiomyocytes, in cell culture, mimics our in vivo pressure overload-induced mTOR and S6K1 activation utilizing a PKC dependent c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, independent of PI3K (ii) ET-1 stimulated phosphorylation of S6K1 at T421/S424 and T389 requires c-Raf and PKCε (iii) ET-1-induced phosphorylation of S2448 of mTOR and T389 of S6K1 utilizes both PKCε and PKCδ (iv) PKCδ is critical for mTOR S2448 and S6K1 T389 phosphorylation during both ET-1 (PI3K-independent) and insulin (PI3K-dependent) activation but does not affect ERK mediated S6K1 T421/S424 phosphorylation. Taken together, our results demonstrate that PKCε and PKCδ differentially regulate ET-1-induced mTOR and S6K1 phosphorylation and activation in adult feline cardiomyocytes and thus provide potential mechanisms for growth regulation in the hypertrophying myocardium by different PKC isoforms.

We have previously shown in vivo (29) that mTOR and S6K1 activation were mediated primarily through a PKC-dependent pathway during the early period of pressure-overload induced hypertrophy. These studies indicate that additional pathways besides PKC and c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathways contribute to PE-stimulated S6K1 activation (Figure-2). A role for PI3K activation during PE stimulation has been suggested in previous studies (36, 45, 46), and our studies support these findings, since pretreatment of adult feline cardiomyocytes with wortmannin resulted in loss of PE- but not ET-1-stimulated mTOR S2448 and S6K1 T389 phosphorylation. To this end, our data demonstrate that ET-1, rather than PE, more closely recapitulates our in vivo data demonstrating PKC/c-Raf/MEK/ERK mediated mTOR and S6K1 phosphorylation (29).

Several recent studies have identified a critical role for the nPKC isoforms in the activation of S6K1 (41, 47). In a recent study the novel PKC isoforms, PKCε and PKCδ, but not the classical PKC isoforms, PKCα or PKCβ, were shown to be involved in PE-stimulated S6K1 phosphorylation of adult rat cardiomyocytes (as measured through electrophoretic mobility shifting of S6K1) (41). Our data, in addition to supporting these findings, demonstrate critical roles of both PKCε and PKCδ and delineate their importance during both PI3K-independent and -dependent signaling pathways mediating phosphorylation on specific residues of both mTOR and S6K1.

Expression of a kinase-inactive PKCε mutant (DN-PKCε) blocked ET-1 stimulated ERK phosphorylation and T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1. Our previous work in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (33) linked PKCε mediated signaling to ERK phosphorylation. Therefore, it is possible that PKCε inhibition blocked ET-1-induced T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1 by modulating ERK activation. DN-PKCε expression, however, also blunted ET-1 stimulation of mTOR S2448 and S6K1 T389 phosphorylations (Figure-4A). Two possible mechanisms could explain why T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 was also blocked by PKCε. First, overexpression of DN-PKCε may have partially blunted PKCδ activity, as has been suggested in prior studies with adenoviral mediated transgene overexpression (41). We do not expect this to be the case, since DN-PKCε expression showed no significant effect on insulin-stimulated T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 (Figure-4B) while the specific blockade of PKCδ using rottlerin or dominant negative expression successfully blocked T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 (Figure-5A, B and Figure-6). A second mechanism involves the blockade of mTOR phosphorylation occurring through either a direct PKCε effect or indirectly through its role in ERK activation (48). This last idea is supported both by DN-Raf expression (Figure-2) and our previous study (30), using pretreatment with a MEK inhibitor U0126 or expression of a MAPK phosphatase, MKP-3. All of these treatments effectively blocked ERK activity and also prevented phosphorylation at S2448 of mTOR and T389 of S6K1. Therefore, it is possible that in ET-1 stimulated adult cardiomyocytes, PKCε activates the c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway leading to S2448 phosphorylation of mTOR and T389 phosphorylation of S6K1, in addition to its role in controlling T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1.

In regard to PKCδ, specific inhibition with rottlerin or DN-PKCδ expression in cardiomyocyte cultures blocked both ET-1 (PI3K-independent) and insulin (PI3K-dependent) stimulated S2448 and T389 phosphorylation of mTOR and S6K1, respectively, while having no effect on either ERK or S6K1 T421/S424 phosphorylations (Figure-5A, B and Figure-6). One possible explanation is that PKCδ exists in a signaling module/complex with mTOR, as has been shown previously (49). A link between mTOR and various PKC isoforms was also demonstrated in HEK293 cells in which mTOR was shown to be responsible for controlling phosphorylation in the hydrophobic C-terminal site of both PKCε and PKCδ (50). Taken together, these data suggest that PKCδ plays a role in S6K1 activation independent of the c-Raf/MEK/ERK-mediated T421/S424 phosphorylation, but may remain dependent on mTOR activation. Finally, although PKCα was found to be activated in our in vivo pressure-overload model (29) we did not observe any role for this kinase in this present study during ET-1-induced S6K1 activation. Pretreating cardiomyocytes with the classical PKC isoform inhibitor, Gö6976, had no effect on ET-1 stimulated mTOR or S6K1 phosphorylation.

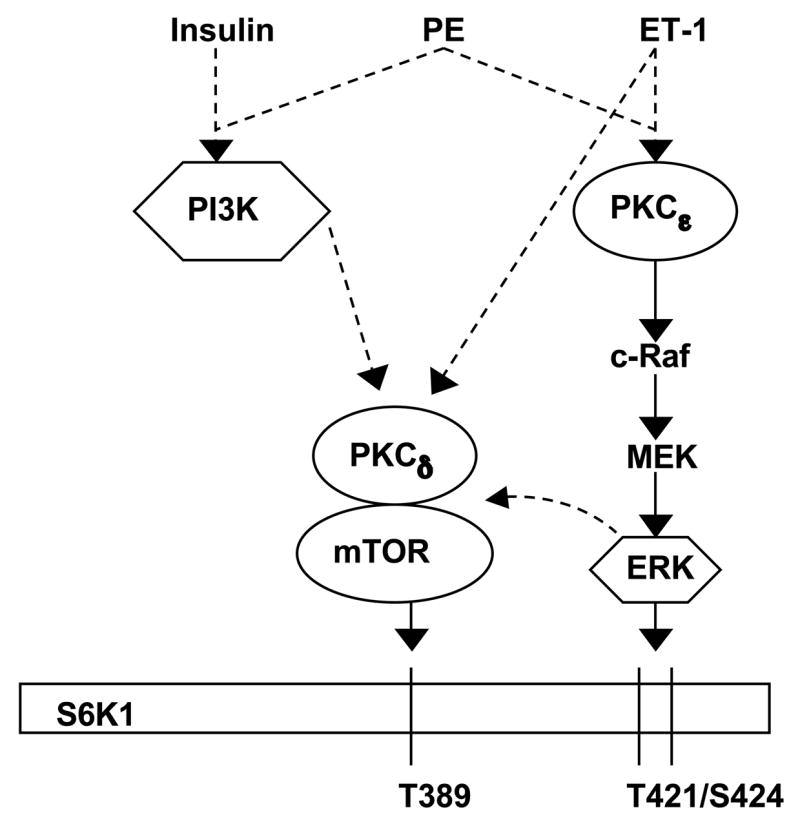

Based upon our present study, we propose the signaling mechanism illustrated in Figure-7. ET-1 stimulation leads to PKCε activation via a PI3K-independent pathway involving cRaf/MEK, which results in T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1 through the c-Raf/MEK/ERK cascade. PKCε also appears to be required during ET-1 stimulated mTOR S2448 phosphorylation and subsequent T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 (Figure-4A). Interestingly, insulin appears to stimulate T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 independent of PKCε (Figure-4B) and c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway and supports our previous studies showing low level of ERK activation in insulin treated adult cardiomyocytes (30). Our present study indicates that this trend partly applies to PE stimulation also. Finally, PKCδ is required during both ET-1 and insulin stimulation of S2448 phosphorylation of mTOR and subsequent T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 (Figure-5 and 6). In summary, we have identified that ET-1 utilizes a PI3K-independent pathway to stimulate mTOR and S6K1, which corresponds to our in vivo observations during the early period of pressure overload. This activation utilizes PKCε and PKCδ to differentially regulate phosphorylation on critical growth components at specific regulatory sites and provides further insight into growth regulation. The activation of mTOR has been studied as a critical component of the compensatory growth response; furthermore our in vivo observations have demonstrated PKC mediated activation of mTOR during the early phase of compensatory growth. This study has now delineated the various pathways that converge on the nPKC isoforms and control the activation of critical growth regulators mTOR and S6K1. In addition we have demonstrated that PKCδ is also a downstream component of PI3K activation. The research surrounding PI3K place this pathway independent of any PKC activation, however we can show that indeed, in adult cardiomyocytes, the PI3K pathway utilizes a specific PKC isoform, PKCδ, during mTOR and S6K1 activation. This data provides a map to acutely manipulate the activation of these critical growth regulators through influence on the nPKC isoforms and possibly regulate compensatory growth in order to delay or even prevent maladaptive compensation in the myocardium.

Fig 7. Model showing the differential roles of nPKC isoforms during S6K1 activation by ET-1, PE and Insulin as demonstrated during in vivo pressure overload.

Activation of PKCε during in vivo pressure overload or ET-1 stimulation activates the c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway independent of PI3K activation. Activation of this pathway controls the phosphorylation of mTOR at S2448 and S6K1 at T421/S424 and T389. Activation of PKCδ is also required for mTOR activation and T389 phosphorylation of S6K1 during ET-1 stimulation, although its activity is not required for T421/S424 phosphorylation of S6K1. During insulin stimulation, PI3K dependent activation utilizes PKCδ and not PKCε for mTOR activation and T389 phosphorylation of S6K1. PE stimulation utilizes both PI3K-independent (similar to ET-1) and PI3K-dependent (similar to insulin) pathways for mTOR and S6K1 activation. Overall, these data reveal a combined role for both PKCε and PKCδ on mTOR S2448 and subsequent S6K1 T389 phosphorylation, while simultaneously exhibiting a specific role for PKC on S6K1 T421/S424 phosphorylation.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by Merit awards from the Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, by Program Project Grant HL-48788 from the NIH, and by an NIH T32HL07260 predoctoral fellowship for Phillip Moschella. We would like to thank Dr. Jim Tuxworth for careful reading of this manuscript. We also thank Ms. Mary Barnes and Dr. Harinath Kasiganesan for adult cardiomyocyte isolation and Ms. Charlene Kerr for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chua BH, Russo LA, Gordon EE, Kleinhans BJ, Morgan HE. Faster ribosome synthesis induced by elevated aortic pressure in rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:C323–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.252.3.C323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper Gt. Basic determinants of myocardial hypertrophy: a review of molecular mechanisms. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:13–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shioi T, McMullen JR, Tarnavski O, Converso K, Sherwood MC, Manning WJ, Izumo S. Rapamycin attenuates load-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circulation. 2003;107:1664–70. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000057979.36322.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ha T, Li Y, Gao X, McMullen JR, Shioi T, Izumo S, Kelley JL, Zhao A, Haddad GE, Williams DL, Browder IW, Kao RL, Li C. Attenuation of cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting both mTOR and NFkappaB activation in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:1570–80. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMullen JR, Sherwood MC, Tarnavski O, Zhang L, Dorfman AL, Shioi T, Izumo S. Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin regresses established cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload. Circulation. 2004;109:3050–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130641.08705.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montagne J, Stewart MJ, Stocker H, Hafen E, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Drosophila S6 kinase: a regulator of cell size. Science. 1999;285:2126–9. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5436.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shima H, Pende M, Chen Y, Fumagalli S, Thomas G, Kozma SC. Disruption of the p70(s6k)/p85(s6k) gene reveals a small mouse phenotype and a new functional S6 kinase. Embo J. 1998;17:6649–59. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jefferies HB, Reinhard C, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Rapamycin selectively represses translation of the “polypyrimidine tract” mRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4441–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Groot RP, Ballou LM, Sassone-Corsi P. Positive regulation of the cAMP-responsive activator CREM by the p70 S6 kinase: an alternative route to mitogen-induced gene expression. Cell. 1994;79:81–91. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Li W, Williams M, Terada N, Alessi DR, Proud CG. Regulation of elongation factor 2 kinase by p90(RSK1) and p70 S6 kinase. Embo J. 2001;20:4370–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raught B, Peiretti F, Gingras AC, Livingstone M, Shahbazian D, Mayeur GL, Polakiewicz RD, Sonenberg N, Hershey JW. Phosphorylation of eucaryotic translation initiation factor 4B Ser422 is modulated by S6 kinases. Embo J. 2004;23:1761–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson CJ, Broenstrup M, Fingar DC, Julich K, Ballif BA, Gygi S, Blenis J. SKAR is a specific target of S6 kinase 1 in cell growth control. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1540–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110:163–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, Yoshino K, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Avruch J, Yonezawa K. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell. 2002;110:177–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, Oppliger W, Jenoe P, Hall MN. Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2002;10:457–68. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolster DR, Kubica N, Crozier SJ, Williamson DL, Farrell PA, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Immediate response of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated signalling following acute resistance exercise in rat skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2003;553:213–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.047019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenessey A, Ojamaa K. Thyroid hormone stimulates protein synthesis in the cardiomyocyte by activating the Akt-mTOR and p70S6K pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20666–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512671200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiang GG, Abraham RT. Phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) at Ser-2448 is mediated by p70S6 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25485–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varma S, Khandelwal RL. Effects of rapamycin on cell proliferation and phosphorylation of mTOR and p70(S6K) in HepG2 and HepG2 cells overexpressing constitutively active Akt/PKB. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:71–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pullen N, Dennis PB, Andjelkovic M, Dufner A, Kozma SC, Hemmings BA, Thomas G. Phosphorylation and activation of p70s6k by PDK1. Science. 1998;279:707–10. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dufner A, Thomas G. Ribosomal S6 kinase signaling and the control of translation. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:100–9. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han JW, Pearson RB, Dennis PB, Thomas G. Rapamycin, wortmannin, and the methylxanthine SQ20006 inactivate p70s6k by inducing dephosphorylation of the same subset of sites. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21396–403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahalingam M, Templeton DJ. Constitutive activation of S6 kinase by deletion of amino-terminal autoinhibitory and rapamycin sensitivity domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:405–13. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erikson RL. Structure, expression, and regulation of protein kinases involved in the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6007–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou MM, Blenis J. The 70 kDa S6 kinase: regulation of a kinase with multiple roles in mitogenic signalling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:806–14. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung J, Grammer TC, Lemon KP, Kazlauskas A, Blenis J. PDGF- and insulin-dependent pp70S6k activation mediated by phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature. 1994;370:71–5. doi: 10.1038/370071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monfar M, Lemon KP, Grammer TC, Cheatham L, Chung J, Vlahos CJ, Blenis J. Activation of pp70/85 S6 kinases in interleukin-2-responsive lymphoid cells is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and inhibited by cyclic AMP. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:326–37. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cass LA, Summers SA, Prendergast GV, Backer JM, Birnbaum MJ, Meinkoth JL. Protein kinase A-dependent and -independent signaling pathways contribute to cyclic AMP-stimulated proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5882–91. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laser M, Kasi VS, Hamawaki M, Cooper Gt, Kerr CM, Kuppuswamy D. Differential activation of p70 and p85 S6 kinase isoforms during cardiac hypertrophy in the adult mammal. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24610–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iijima Y, Laser M, Shiraishi H, Willey CD, Sundaravadivel B, Xu L, McDermott PJ, Kuppuswamy D. c-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway controls protein kinase C-mediated p70S6K activation in adult cardiac muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23065–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puceat M, Hilal-Dandan R, Strulovici B, Brunton LL, Brown JH. Differential regulation of protein kinase C isoforms in isolated neonatal and adult rat cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16938–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinberg SF, Goldberg M, Rybin VO. Protein kinase C isoform diversity in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:141–53. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao VU, Shiraishi H, McDermott PJ. PKC-epsilon regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase: a potential role in phenylephrine-induced cardiocyte growth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H2195–203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00475.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C, Chen X, Williams JA. Regulation of CCK-induced amylase release by PKC-delta in rat pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G764–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00111.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wenzel S, Abdallah Y, Helmig S, Schafer C, Piper HM, Schluter KD. Contribution of PI 3-kinase isoforms to angiotensin II- and alpha-adrenoceptor-mediated signalling pathways in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:352–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schluter KD, Simm A, Schafer M, Taimor G, Piper HM. Early response kinase and PI 3-kinase activation in adult cardiomyocytes and their role in hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1655–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao XS, Pan W, Bekeredjian R, Shohet RV. Endogenous endothelin-1 is required for cardiomyocyte survival in vivo. Circulation. 2006;114:830–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah OJ, Ghosh S, Hunter T. Mitotic regulation of ribosomal S6 kinase 1 involves Ser/Thr, Pro phosphorylation of consensus and non-consensus sites by Cdc2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16433–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300435200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang TL, Yang YH, Chang H, Hung CR. Angiotensin II signals mechanical stretch-induced cardiac matrix metalloproteinase expression via JAK-STAT pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:785–94. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mackay K, Mochly-Rosen D. Localization, anchoring, and functions of protein kinase C isozymes in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1301–7. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Rolfe M, Proud CG. Ca(2+)-independent protein kinase C activity is required for alpha1-adrenergic-receptor-mediated regulation of ribosomal protein S6 kinases in adult cardiomyocytes. Biochem J. 2003;373:603–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gschwendt M, Muller HJ, Kielbassa K, Zang R, Kittstein W, Rincke G, Marks F. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:93–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gschwendt M, Kittstein W, Marks F. Elongation factor-2 kinase: effective inhibition by the novel protein kinase inhibitor rottlerin and relative insensitivity towards staurosporine. FEBS Lett. 1994;338:85–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woo SH, Lee CO. Effects of endothelin-1 on Ca2+ signaling in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes: role of protein kinase C. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:631–43. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Northcott CA, Hayflick J, Watts SW. Upregulated function of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase in genetically hypertensive rats: a moderator of arterial hypercontractility. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:851–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.04276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doenst T, Wijeysundera D, Karkouti K, Zechner C, Maganti M, Rao V, Borger MA. Hyperglycemia during cardiopulmonary bypass is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1144. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sawhney RS, Cookson MM, Sharma B, Hauser J, Brattain MG. Autocrine transforming growth factor alpha regulates cell adhesion by multiple signaling via specific phosphorylation sites of p70S6 kinase in colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47379–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williamson DL, Kubica N, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Exercise-induced alterations in extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling to regulatory mechanisms of mRNA translation in mouse muscle. J Physiol. 2006;573:497–510. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar V, Pandey P, Sabatini D, Kumar M, Majumder PK, Bharti A, Carmichael G, Kufe D, Kharbanda S. Functional interaction between RAFT1/FRAP/mTOR and protein kinase cdelta in the regulation of cap-dependent initiation of translation. Embo J. 2000;19:1087–97. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parekh D, Ziegler W, Yonezawa K, Hara K, Parker PJ. Mammalian TOR controls one of two kinase pathways acting upon nPKCdelta and nPKCepsilon. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34758–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]