Abstract

Syringe exchange programs (SEPs) aim to reduce the harm associated with injection drug use (IDU). Although they have been accepted as critical components of HIV prevention in many parts of the world, they are often unwelcome and difficult to set up and maintain, even in communities hardest hit by IDU-related HIV transmission. This research examines socio-cultural and political processes that shape community and institutional resistance toward establishing and maintaining SEPs. These processes are configured and reinforced through the socio-spatial stigmatizing of IDUs, and legal and public policy against SEPs. Overarching themes the paper considers are: (1) institutional and/or political opposition based on (a) political and law enforcement issues associated with state drug paraphernalia laws and local syringe laws; (b) harassment of drug users and resistance to services for drug users by local politicians and police; and (c) state and local government (in)action or opposition; and (2) the stigmatization of drug users and location of SEPs in local neighborhoods and business districts. Rather than be explained by “not in my back yard” localism, this pattern seems best conceptualized as an “inequitable exclusion alliance” (IEA) that institutionalizes national and local stigmatizing of drug users and other vulnerable populations.

Keywords: syringe exchange programs, injection drug use, harm reduction, socio-spatial stigma, NIMBY, inequitable exclusion alliance, localism

“We are trying to override the city council vote because you basically have politicians who are embedded in their conservative morality and that morality is driving politics not public interest or health care. So it’s pretty scary.”

Jon Zibbell, Chair (personal communication) Springfield Massachusetts Users Council

Introduction

Epidemiological patterns of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and the effects of stigma, vary among different population groups. Although some aspects of this stigma are shared by all HIV-infected persons, others are population-specific. For example, discrimination against people with HIV/AIDS has drawn from and compounded preexisting stigmas (especially vis-à-vis men who have sex with men (MSM) and injection drug users (IDUs)). Currently, the brunt of the United States (U.S.) epidemic is among racial and ethnic minority groups, inner-city poor and IDUs (CDC, 2004; Mann and Tarantola, 1996).

Thus, people who have acquired HIV by injecting drugs are doubly stigmatized—for being HIV-positive and for being “addicts.” Stigmatization associated with drug use and HIV/AIDS often extends beyond the devaluation or punishment of individuals and groups to become embodied in, and affect, the location of services used by clients (Alonzo and Reynolds, 1995; Daker-White, 1997; Takahashi, 1998). In the U.S., the transfer of stigma from persons to services and often to the places where those services are located can embroil harm reduction focused services such as syringe exchange programs (SEPs), and substitution treatment like methadone maintenance (Des Jarlais et al., 1995a; Des Jarlais, 2000; Lurie and Drucker, 1997).

“Not in my back yard” (NIMBY) movements typically exemplify community opposition to services for stigmatized populations. Such resistance frequently involves concerns over personal security, declining property values, or a generalized perceived threat to the neighborhood’s quality (Dear and Wolch, 1987; Takahashi, 1998). NIMBY politics, Takahashi (1998, p. 81) suggests, “maintain, enforce and reinforce community boundary definitions, resulting in the maintenance of spatial relations of stigma.” These factors affect the utilization, implementation and siting of services for marginalized and vulnerable groups. Additionally, place-based stigmatization affects clients of these services, who may be reluctant to utilize the services due to the stigma attached to persons and place.

Though most community resistance arguments are rooted in local attitudes, community resistance is not purely a local phenomenon. It is tied to wider discourses that stigmatize particular groups and behaviors, and to institutional sources of power that provide resources to those that wish to punish, rather than treat, vulnerable groups. In this research, we extend the concept of resistance toward human services from the local–NIMBY level, to higher systemic levels of government and national culture; and shift the paradigm of the NIMBY concept to consider SEP resistance in view of how public policy, national perceptions toward drug users (specifically injection drug users), and government inaction influence the acceptability or the rejection of SEPs at the local level. We propose that these processes are interrelated and operate at national, state and local levels constructing tendencies to exclude stigmatized groups from resources needed to reduce drug use–related harm.

Using interviews provided by the Community Vulnerability and Response to IDU-related HIV Project we provide illustrations of opposition to consider socio-cultural and political factors that influence resistance toward establishing and maintaining SEPs in the U.S.

NIMBY and socio-spatial distancing: Implications for syringe exchange programs

Most research on community resistance has been centered on facilities for the homeless, supported housing for the mentally ill, half-way houses for ex-offenders, and health-related facilities for persons with AIDS (Dear et al., 1997; Law, 2003; Law and Takahashi, 2000; Lyon-Callo, 2001; Takahashi, 1998; Wolch and Philo, 2000). Social and spatial correlates, such as stigma, underlie characteristics of community response to such facilities (Takahashi, 1998).

Social scientists in seeking to explain local attitudes and resistance toward controversial human services utilize a socio-spatial framework. This framework provides a theoretical base for understanding NIMBY as a socio-spatial stigma. For example, Kearns and Joseph (1993) note, the most socially excluded are often the most spatially distant. Both sorts of “distance”—social and spatial—collapse into one; that is, the constructs that render the “other” different, immoral, or dangerous can be implemented spatially so that physical distance helps safeguard social and moral distance. Dear et al. (1997) argue that difference is characterized by social and spatial processes facilitating the partitioning of the Self from the Other (p. 455). The identification of others as different has clear implications as a mechanism and process for the social exclusion of particular groups deemed different. Thus, the categorization of particular groups and individuals as “deviant” or “nonconforming” results in a purification of space, increasing the visibility of those who do not belong (Fischer and Poland, 1998). Surveillance, both by community and police, is also key to the process through which this dynamic can occur (Atkinson & Flint, 2003; England, 2006; Mitchell, 2003).

Smith’s (1994) research suggests that the sense of one’s social and moral responsibility for others decays as one becomes subjectively distanced from the other. Subjectively distance is argued as being inherently spatial (i.e. individuals as bounded subjects/bodies spatial situated in relation to others) (Soja, 1980; Wilton, 1998). Research by Low (2003) on gated communities, maintains that through physical exclusion residents make it more difficult for themselves to know or care about fellow citizens who are socially, economically, or racially different.

Chiotti and Joseph (1995) outlined three broad perspectives based on the geographic and social theory literature (accessibility, structuralism, and humanism) to understand local attitudes regarding the location of an AIDS hospice facility. Their study found that the location of a hospice is part of the social and spatial process that “serves to reproduce the dominant form of social stratification (dictated by class and culture) and its attendant landscape.” (p. 136). Dear and Wolch (1987) found similar results in describing the concentration of community-based human services in “service-dependent ghettos.” The authors viewed the ghetto as a “landscape of power” whose terrain is heavily marked by the intersection of the powerful welfare state and capitalist urbanization.

These socio-cultural and political dynamics can affect the quality of life and survival of many service-dependent people, including services to reduce drug-related harm for IDUs (Daker-White, 1997; Parker and Aggleton, 2003; Takahashi, 1998). Fischer and Poland (1998), for example argue that increased stigmatization of already marginalized groups can lead to increases in risk behaviors among such groups. Their research suggests that institutionalized means of social control, including legal punishments, deterrence, and compliance, may be related to risk behavior and epidemiologic outcomes.

Research by Friedman et al. (2006) found that higher rates of legal repressiveness (hard drug arrests; police employees per capita; and corrections expenditures per capita) are associated with higher HIV prevalence rates among injectors. Aggressive police tactics and/or stigmatization may lead IDUs to engage in hurried injection behaviors, to share syringes more often, and/or to inject in high-risk environments (Aitken et al., 2002; Bluthenthal et al., 1999a; Bluthenthal et al., 1999b; Cooper et al., 2005a; Maher and Dixon, 1999; Rhodes et al., 2006)—and, in addition, to impede the creation or functioning of syringe exchange (Bluthenthal et al., 1997; Davis at al., 2005; Rich et al., 1999; Wood et al., 2003), drug treatment, or other programs to improve users’ health (Des Jarlais et al., 1995a).

Drug-related arrests have been found to affect the use of treatment services by drug users; moreover, arrests of staff at illegal SEPs are associated with later declines in program participation (Bluthenthal et al., 1997; Friedman et al., 2006). Other studies indicate that injectors who fear arrest hesitate to carry syringes, even in states with legal syringe possession which, in turn can impact the quality of life and health of injectors (Aitken et al., 2002; Bourgois et al., 1997).

Similarly, the qualitative research of Rhodes et al., (2006) on public injecting environments in the United Kingdom and Canada, highlights how social regulation of public space interacts with risk associated with public injecting. This research illustrates the dynamic interplay between 3 factors: fear of interruption (by police), privacy, and lack of facilities. These factors combine to affect hygiene and safety as IDUs and lead to an increased risk of infection by a blood-borne virus. Further research indicates that policing patterns affect drug users’ health, even in states where syringe access is considered legal. For instance, Cooper et al., (2005a) found that IDUs who lived in a precinct undergoing a police drug crackdown said that particular crackdown strategies created difficulties in achieving safe injections.

Challenges of contesting the socio-spatial boundaries of who is acceptable to use public space and the “new urban order” are increasingly a dominant discourse among public health and HIV policy advocates. Mitchell’s (2003) research on homelessness, for example, looks at the introduction of laws that criminalize homelessness and deny people access to, and use of, public space within the city. The example above looks at the way in which developmentally disabled people are denied access to space in the neighborhood because of concerns about neighbors’ reactions. Similarly, the research of Fischer et al., (2004) looks at “supervised injection sites (SISs) as a case study of post-welfarist govermentality. This research contends SISs arose as a means of “purifying public spaces of “disorderly” drug users to present the “new city” as an attractive consumption space.” Fischer et al. seeks to understand SISs as a form of governmental regulated risk consumption and the socio-spatial exclusion of marginalized populations from the city core under the “guises of public health.” Contrary to this dynamic underground SEPsI could also in some instances be interpreted as a purification of public space. In this case though, it provides a safety net for SEPs clients and services providers. In this way the SEP does not disrupt neighborhood space, since its presence goes unnoticed—NIMBY or other opposition is averted. Though staff and users of the service must be covert to varying degrees in how they use space and navigate the environment, services are nevertheless provided.

NIMBY-type opposition, for example, has greatly hampered attempts to establish services to prevent the spread of HIV among IDUs in places such as Springfield, Massachusetts, where 54% of AIDS cases are attributed to injection drug use (Buchanan et al., 2003). Springfield pro-SEP activists have experienced ongoing opposition from local citizen’s group since 1998. For example, a variety of groups, including white suburban, middle-class voters and a predominantly inner city African-American organization spoke out against SEPs in their communities; white suburban residents were motivated by a belief in small government and postwelfare state. While Springfield’s politically marginalized inner city communities were motivated by a struggle of poverty, racism, and withdrawal of local neighborhood resources (Shaw, 2006). Community opposition in Springfield had effectively shaped health outcomes for IDUs through defining health policies that reflect their local socio-cultural and political goals and views. These efforts have forced many IDUs to travel across state borders to buy syringes over the counter, or to buy locally from diabetics or black-market sellers who charge $5–$10 per syringe (Shaw, 2002). The lack of social and political tolerance for safe syringe access in Springfield increases the risk of syringe reuse and the potential spread of HIV among IDUs and beyond.

When rooted in place, stigma affects both the client and the location of human services facilities, especially services for those who are highly stigmatized. As a social process, stigma operates by producing and reproducing social structures of power, hierarchy, class, and exclusion, and by transforming difference into social inequality. Within this context, notions of stigma and the social production of difference are useful in helping conceptualize socio-spatial distancing processes, and in understanding how these processes shape community vulnerability toward HIV, and NIMBY-type responses to controversial services such as SEPs.

Historical and Social Contexts of Opposition to SEPs in the United States

In the U.S., SEPs can be difficult to set up even in communities that are hit hardest by injection drug use–related HIV transmission (Shaw, 2006; Tempalski, 2005), despite research demonstrating their effectiveness in reducing risk. Public health researchers have found that syringe exchange reduces HIV risk by reducing the number of potentially infected syringes that circulate in an injectors’ injecting network (Lurie et al., 1993; Kaplan and Heimer, 1994). SEPs have indeed been found to reduce HIV transmission (Des Jarlais et al., 1995b; Hurley et al., 1997; MacDonald et al., 2004; Vlahov et al., 2001).

Resistance to SEPs varies and can be embodied in community attitudes, law enforcement, and political opposition within various levels of government, and in some cases, symbolized through government (in)action around SEP establishment (Bluthenthal, 1998; Keem et al., 2003). For example, the failure of the U.S. federal government to initiate a national program for syringe exchanges can be viewed as government inaction in addressing the spread of blood-borne diseases among IDUs. As such, lifting this ban would send a clear signal that the U.S. government is invested in arresting the transmission of blood-borne diseases.

Services for drug users in the U.S. are often met with resistance. Neighborhood opposition has either delayed or prevented setting up many types of drug treatment programs (e.g., methadone maintenance) (Des Jarlais et al., 1995a), including the establishment and relocation of SEPs (Shaw, 2006; Tempalski, 2005). Prior research on community resistance toward SEPs has cited the fear of program adoption leading to a decrease in property value (Colon and Marston, 1999), or fear of physical danger, such as potential harm from dirty needles (Strike et al., 2004), as reasons for opposing the location of SEPs in a particular area.

There are important differences to note considering resistance to syringe exchange programs in the U.S. in comparison to opposition to services for other underserved or stigmatized populations (e.g., services for the homeless and mentally-ill). First, many SEPs operate covertly either because they are not sanctioned by the law or to minimize opposition. Lack of formal support from local elected officials is usually the reason for covert operation, which is referred to as being “underground.” These SEPs function below the radar of law enforcement or in some cases with the tacit tolerance by law enforcement, and operate where state law does not allow anyone to sell or give a syringe to an IDU for illicit drug injection. Others are underground because they are forced out of sight as a result of NIMBY-type opposition, or to avert opposition.

In the early years of syringe distribution local AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) chapters created AIDS prevention services for injectors through the organizing of direct services as a form of direct action where the majority of syringe distribution occurred without open or even tacit support of law enforcement officials, and, as much as possible, without the knowledge of these officials. Illegal SEPs are formed somewhat differently than legal SEPs, although some eventually do acquire legal status. As mentioned above, individual activists forming SEPs may decide to distribute syringes clandestinely because the logistics of operating a legal SEP simply do not work in some places. SEP organizers find that if the SEP does not disrupt neighborhood space its presence goes unnoticed, NIMBY opposition is avoided, and the organization is better able to accomplish its mission of providing services.

Secondly, the United States has historically been the leader in law enforcement and abstinence-based approach to illicit drug use (Musto, 1999). Harmful drug policies can affect drug users’ health in two ways: (a) it increases elite and lay tendencies to stigmatize drug users, thereby increasing resistance to services for IDUs, resulting in a lack of services; and (b) it increases the rate of incarceration of drug users.

Additionally, opposition to HIV/AIDS prevention services for IDUs (such as harm reduction services) has been fueled by city, state and national political and media leaders, as well as the “war on drugs,” which further increases the stigmatization of drug users and for services to drug users. The war on drugs provides opponents with additional arguments for objecting to such programs. Specifically, law enforcement personnel, politicians, and some community members have argued that syringe exchange conflicts with the “Just Say No” or abstinence-based drug education policies and the war on drugs.

Lastly, the failure of the U.S. federal government to initiate a national program for syringe exchange has shifted the emphasis of HIV prevention for IDUs to the states and localities. Although some state and local governments have risen to the challenge, many have not. As a consequence, the local response to the HIV epidemic among IDUs has varied widely.

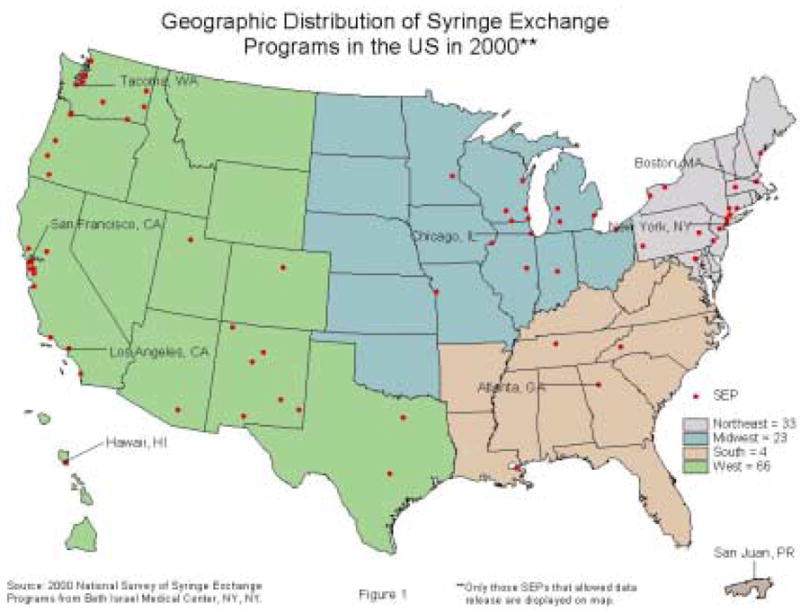

Figure 1 depicts the spatial distribution of SEPs in the United States. The largest geographic clusters of programs are located in the Northeast and the WestII. The South and the Midwest continue to have low numbers of SEPs. The southern and midwestern SEPs remain low in the medical and social services they provide, with few programs publicly funded. In contrast, the northeast and western regions SEPs are most likely to be publicly funded and to provide medical and social services (Tempalski et al., 2003a).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework

In the U.S., opposition to human services can take the form of loosely (or tightly) bonded socio-cultural and political processes that institutionalize an inequity-defending exclusion of the vulnerable, which we refer to here as “inequitable exclusion alliances (IEA).” These alliances’ power and resilience lie in the fact that they are opportunistic and implicit. In the case of syringe exchange, this is embodied in institutional repression and exclusion as a result of several factors, including: the political “war on drugs”; a socio-cultural stigmatization of drug users and view of drug use and users as “criminals” and “junkies”; harassment of drug users by local law enforcement as a result of a legal and policy framework with regard to drug paraphernalia laws; a federal ban on funding for SEPs; over-the-counter-laws that restrict access to clean needles and thus reinforce government (in)action to help stop the spread of HIV among IDUs; and all of the more traditional aspects of NIMBYism such as symbiotic moralizing against the vulnerable and defining their presence as a threat to property values.

This socio-cultural and political approach to drug users then fuels stigma against and opposition to services for them. Our IEA concept suggests that viewing resistance to SEPs as government (in)action toward HIV prevention services misses a crucial point—that such (in)action is part of a national, state and localized pattern of exclusion and stigmatization of drug users, with a broad defense of the political economic status quo.

We further argue, then, that this stigma can dictate the form and function of local and national exclusionary alliances, leading to opportunistic actions that both reinforce social stigma and manage spatial stigma. Such actions are not centrally coordinated, but operate through socio-cultural norms, and legal and public policy. Our conceptual argument is then as follows:

social and spatial stigma create implicit norms for (in)action at both local and national levels;

implicit norms for (in)action lead to a legal and policy framework (state and local drug paraphernalia and syringe prescription laws) that privileges inaction and rejection by state and local actors (local district attorneys and politicians, and local police officials and beat officers).

The combination of socio-spatial stigma, and of a legal and policy framework, shape the configuration of local exclusionary alliances, opportunistic efforts consisting of different sets of actions led by local area residents and business interests, and state and local (in)action to ensure the non-establishment of SEPs or the removal of those already in place.

Methods and Data Collection

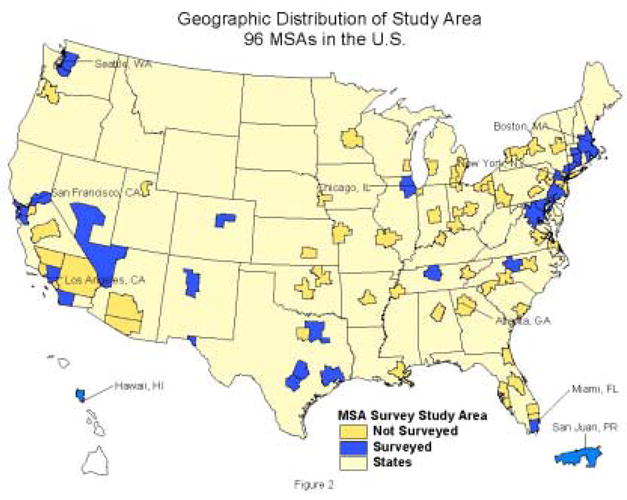

This paper is part of a larger research project that focuses on HIV, injection drug use, and HIV prevention services to injectors in the 96 largest U.S. metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) (Cooper et al., 2005b; Friedman et al, 2004; Tempalski et al., 2003b). We initially planned to conduct interviews in all 96 MSAs; however, locating and reaching appropriate participants took more effort than anticipated. Hence, we selected 32 MSAs through stratified purposive sampling to ensure variation in geographic location and the availability of drug abuse treatment and other services for IDUs. The creation of the sample involved three sets of criteria: (1) geographic region; (2) within each geographic region we sought to include MSAs that represented a relatively large amount of IDU-focused activity as well as MSAs where few or no such activities were taking place. Thus we noted the presence of syringe exchange programs, NIDA-funded research, and Ryan WhiteIII grant funding in each of the MSAs; and (3) we ranked each of the 96 MSAs according to 5 indicator variables, which were the size of the MSA population in 1998, the size of the IDU population as estimated by Holmberg (1996), the prevalence of HIV among IDUs as estimated by Holmberg (1996), the availability of drug treatment for IDUs as estimated by Freidman et al., 2004), and the prevalence of AIDS among an MSA’s population of men who have sex with men (Holmberg, 1996).

In MSAs where prevention programs for IUDs were limited, it was not always possible to find people to talk about why programs did not exist. However, in areas that responded early to the spread of HIV among IDUs and developed a variety of prevention strategies, people were eager to discuss their programs and to refer us to other potential interviewees. These data collection limitations resulted in some MSAs having more data than others.

In these 32 MSAs, we conducted a Survey of Community ExpertsIV to determine the existence, size, timing, and sources of opposition, support, and controversy regarding drug abuse treatment, outreach, syringe exchange, and other responses to HIV/AIDS among IDUs; and whether and when any of these programs became foci of controversy in the media or in political campaigns. We attempted to interview 5 local experts in each metropolitan area. This number necessarily varied according to the size of the MSA and the complexity of the services offered. For example, in a large MSA several individuals might handle different aspects of just one of the types of programs that interested us (syringe exchange, outreach, and drug treatment) while in a smaller MSA one person might have responded to our survey regarding all three areas of activity. The interviews were conducted mainly by telephone and email. Telephone interviews lasted approximately an hour with the (primarily open-ended) questions being sent to respondents in advance. The interview protocol was modeled from Friedman (1970) and after the letter-followed-by-telephone call format used in syringe exchange program surveys conducted by Beth Israel (Paone et al. 1996, 1997, 1999).

Transcribed interviews were coded and analyzed for discussions of various types of potential key words/categories regarding SEP (e.g. resistance, police, attacks, harassment, NIMBY, and opposition and/or support, neighbors, media, politics and regulations). Interviews were coded in Atlas.ti using a series of codes developed based on themes from the interviews. While respondents from the same MSA were often able to provide different amounts of information about SEPs and other services in the MSA, disagreements on overlapping data rarely occurred. All of the respondents’ names and locations used in this paper have been changed to protect their anonymity.

Our sample for this paper consisted of 93 telephone interviews in 32 MSAs (Figure 2) with respondents who completed the syringe exchange section of the interview. Twenty-four interviews were conducted with SEP directors, 14 with drug treatment providers, 13 with outreach workers, 28 with researchers and with 14 public health administrators. Interviews took place during the study period of August 2001 to February 2004.

Figure 2.

Themes V

Though the history of resistance to SEPs is unique in each MSA, respondents from across the U.S. sounded some common themes. One of the many problems cited by respondents was language regarding the immorality of drug use that their critics frequently used. The simplistic “Just say No” platitude implies that drug users suffer only from a lack of discipline and are personally responsible for and guilty of their addiction even though research shows that people (of all colors and economic backgrounds) who use drugs do so within a social and cultural context (Cooper et al., 2005b; Courtwright et al., 1998; Latkin et al., 2006; Musto, 1999). Our respondents reported that they typically avoided discussion with regard to the morality and evils of drug use, and also discussion framed in terms of SEPs working against the war on drugs. Instead our respondents try to focus debate on questions of public health and the importance of safe injection. They also address issues of morality as important motivation to support programs. Important public health messages such as using a sterile syringe for each injection is a form of morality that says “We can’t let people die.” (Dave Purchase, personal communication, 2003). In some cases, pro-SEP community activists see themselves as acting out of moral necessity and as being justified in handing out sterile syringes to avert greater harm.

Thus, we argue that opposition toward SEPs in the U.S. comes from a variety of actions that can affect the establishment, maintenance and location of these programs. These actions take multiple forms and extend beyond local resistance of local neighbors and businesses to include law enforcement issues including police harassment, national and state syringe prescription laws, drug paraphernalia laws, and political (in)action. Based on the interplay and complexities of these processes, we suggest expanding the analytic framework for interpreting NIMBY-type opposition from the local, to include broader national based policies and laws. This framework strengthen socio-spatial stigma to ensure the non-establishment of SEPs or the removal of those already in place.

For example, in the U.S., drug policy has focused on criminalizing drugs and on depicting users as immoral and incompetent (Friedman, 1998; Musto, 1999). This socio-cultural and political approach to drug users in general has fueled stigma-related attitudes toward IDUs and services for injectors. This leads, in turn, to still other forms of opposition such as police harassment of service providers and clients, or program suppression using laws against the distribution of “drug paraphernalia” such as syringes. A local outreach worker discussed the ongoing difficulties in trying to establish an SEP with regard to the legal framework of drug paraphernalia laws and the police as the biggest obstacles:

“There were attempts to set up a public program early on, about 8–10 years ago, but the police would not permit it. No one has made an attempt to do anything publicly in the last five years. It is not illegal to set up a syringe exchange, but it is illegal to carry drug paraphernalia. The police arrested everyone who tried to set up programs.”

Our analysis of opposition to SEPs and the presentation of our findings here proceeds according to these themes, which included: (1) institutional and/or political opposition based on (a) political and law enforcement issues associated with state drug paraphernalia laws and local syringe laws; (b) harassment of drug users and resistance to services for drug users by local politicians and police; and (c) state and local government (in)action or opposition; and (2) stigmatization of drug users and SEP resistance from neighbors and businesses. Particular details of the respondents’ accounts (such as various types of police interference, or political inaction) are not all present everywhere and they are present to differing degrees in the MSAs where they are present. A certain form of opposition might indeed be unique to one MSA, but it is still important because it is part of the overall pattern of resistance to SEPs. Taken together, these accounts depict a socio-cultural and political structure of inequitable exclusion alliances (IEA) that encircles drug users and circumscribes the efforts of those who try to provide life-saving assistance, such as services to reduce drug-related harm.

Institutional and/or political opposition

(1A) Political and law enforcement issues associated with state drug paraphernalia laws and local syringe laws

Forms of institutional opposition can result from on-going police harassment of service providers or difficult relations between police and programs stemming from the legal and policy framework of distributing syringes based on state drug paraphernalia laws. Government legal and regulatory barriers such as state drug paraphernalia lawsVI are found in the District of Columbia and every state except Alaska; state prescription laws or syringe regulations are active in 11 statesVII and the Virgin Islands; and pharmacy regulations and practice guidelines are in place in 23 states (American Bar Association, 2001). Government structural constraints, which differ by state and locality, can significantly reduce the ability of IDUs to purchase and possess sterile syringes. Policy processes and regulations governing syringe sales at the state and local levels (e.g., prescription and drug paraphernalia laws) influence the legality of syringe access, the conditions of syringe distribution, and the use of government funds to distribute syringes. One SEP worker provided an example of how the current state and local syringe laws work against providing services:

“If you work for it (the SEP) they arrest you. There’s that kind of harassment. There are people being arrested all the time for possession of syringes. Even if they have a card…They can show a card and they’re told that’s no good here. I don’t know of any workers going to jail, but I know participants have gone to jail for possession of syringes.” [MSA1]

Laws against over-the-counter syringe sales work against IDUs having access to clean syringes and increase the extent to which they share syringes and perhaps other drug paraphernalia. Sharing of needles and injection equipment, in turn, increases their risk of HIV transmission. In some locations where over-the-counter-laws are in place, IDUs enter pharmacies without any certainty that they will be able to buy a clean syringe. One drug researcher had this to say about syringe access through pharmacies:

“Over the counter sales are “quasi-legal”, meaning that the law leaves it up to the discretion of the pharmacy owner and some of them might choose not to sell to people they think are IDUs.” [MSA2]

Regardless of the policy and legality framework of syringe acquisition, SEP clients get arrested for carrying syringes and staff get arrested for exchanging syringes, both of which directly affect syringe coverage and declines in program participation to IDUs, thus increasing syringe sharing and risk environment. Police harassment and arrests of SEP clients and service providers can further lead to the closing or shifting of the location of programs. Still, police have tremendous latitude as to whether or not they enforce a law based on state and local legislation regarding drug paraphernalia laws and laws banning the sale of syringes over the counter.

(1B) Harassment and resistance by politicians and police

Prejudice attached to drug use is reinforced by the illegal and covert nature of illicit drug use. Types of harassment and prejudice by politicians and police mentioned by our respondents included city council members who believed that drug use is wrong and would oppose syringe exchange to maintain their consituents’ support. As a result of such prejudices, people who use drugs are easy targets for other local problems whether related to drug use or not. For example, a change in the prevalence of certain crimes can lead to a shift in priorities among local law enforcement, and in some cases, a change in support for programs such as syringe exchange. In the example below, a public health adminisrator discussed how an increase in murders and crack use led police who once supported a local SEP to become less tolerant of drug users and hence less tolerant of syringe exchange. Thus, scapegoating drug users as a result of an increase in crime led to police cracking down drug users:

“There is a homicide a day in [our city], it is crack cocaine coming in again. The police are cracking down. Police are better at respecting areas around the SEP than they have been in the past, but it is an ongoing discussion. The needle exchanges are willing to identify syringes as coming from their program and even to identify users as registered users. But skyrocketing homicide rates put an end to cooperation from the police” [MSA3]

A public health administrator described the “police chief‘s prejudiced attitude” toward drug users and how this prevented local police from supporting “any” services for drug users:

“The Chief of Police would probably go out and personally shoot any NEP workers. The Chief doesn’t believe in drug treatment…he’s been the chief for 20 years… [MSA4]

Finally, one researcher who tried to start a SEP describes how physical abuse by police shut down the program:

“The director of that program was harassed by the police to the extent where they had her down on the ground and her head in the gutter, so there were some physical things there by the police.” [MSA5]

Some individuals view HIV as a natural, acceptable consequence of deviant behavior. If, and when, such beliefs spread, they intensify stigma and create barriers to initiating HIV prevention services for IDUs. In this case, it is not a negative experience with syringe exchange that leads to local opposition to these services, but the overall moral judgment that drug users are evil. Furthermore, anti-SEP advocates agree with legal policy and law enforcement efforts, that SEPs work against the goals of abstinence-based treatment programs and the “war on drugs” by enabling drug use. As a result of these types of opposition to SEPs in the U.S., community activists, business owners and law enforcement personnel are trying to block new SEPs and suspend existing programs.

Public health strategies such as using a sterile syringe for every injection are designed to reduce the transmission of blood-borne diseases. The public health approach thus seeks to provide IDUs with the means to protect themselves against HIV and other diseases. This approach differs drastically from law enforcement and policy responses to the social and health problems associated with injection drug use. These present formidable obstacles to public health strategies to prevent HIV among IDUs, rendering it much more difficult to acquire sterile syringes, and reduce injecting risk environments.

(1C) Political (in)action

Political opposition to SEPs can be expressed through state and local government (in)action. Fear of adopting or discussing SEPs in the political and public health sectors, because of perceived political opposition can be some the biggest barriers to implementing programs in some localities. Political opposition can paralyze attempts by community members to start an SEP, and can occur at different government levels. For example, in 1993, California tried to ban syringe exchange at the state level; however, while a court case was challenging the constitutionality of that ban, the city of San Francisco declared a local emergency, enabling it to establish a city-funded exchange program. In this example, although, the state was trying to paralyze the distribution of syringes, the city was able to overcome state actions.

A governor in one state passed a syringe law for there to be ten pilot SEPs throughout the state. The law stated that local approval is needed in each specific city and that this could happen in two ways: if the mayor writes an executive order saying it’s approved or if the city council votes on it and approves it. One harm reduction supporter talks about a neighborhood coalition group organizing against syringe exchange in his area:

“…And so what happened is that [neighborhood] coalition organized all those white communities and voted those people in and the non-binding referendum on the ballot failed for needle exchange. So the city council went back on their yes vote and rescinded their vote, which I think is illegal. We haven’t had the money to fight it legally. So in 1998 they actually voted for it and then they reversed the decision and ever since then it has been hard to get it passed. None of them really have any arguments or any knowledge about drug use or medicine or healthcare or anything. Its like politicians making decisions on a public health level. It’s really problematic. So, we can’t get it passed the city council. We try, we’ve tried the city council for years. Then we tried the community level and finally we just said we have to do this anyways, people are dying. If we go to jail, we go to jail, whatever.” [MSA6]

AIDS advocacy groups and public health researchers argue that the conservative views of the local community, backed by a Republican majority, can knock down any initiative to establish a legal SEP. In explaining why an SEP did not exist in one city, a local activist and university researcher describes the political environment in their MSA in the following terms:

“Politically, I mean there are lawyers that come up to me and… people know me, I don’t even know them sometimes, but they know me. “You’re doing good work. We know what you’re doing.” and stuff like that. But, it’s the political structure, the state elected officials who won’t budge [on voting for SEPs] and the powers-that-be.” [MSA7]

“There are none. The political climate is such that … forget it. There has never been needle exchange here. No one seems to want to do it… the door is slammed shut by the legislature and the mayor. There is no chance for it for a long time.” [MSA8]

Attempts to set up SEPs in New Jersey, Massachusetts, and California point to political processes producing a disconnect between service needs and public policy. In New Jersey, injection drug use is the most frequently reported risk behavior among HIV-positive individuals, (as reported by the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services). The number of IDU-related AIDS cases in the state peaked in 1993, accounting for 49% of the AIDS cases that year. Despite that alarming situation, in April 1996, the then governor of New Jersey, Christine Whitman, rejected the recommendations of her Advisory Council on AIDS to distribute clean needles to intravenous drug users and allow the sale of syringes in pharmacies, stating that SEPs are ineffective and send the wrong message. By 2000, the only publicly visible SEP in the state had been suppressed by arrests. In 2004, an executive order by Governor James E. McGreevey was signed, permitting programs for injectors to acquire sterile syringes in Camden and Atlantic City. However, that the executive order was quashed by three state Senators. On December 19, 2006, New Jersey Governor Jon Corzine signed the Bloodborne Disease Harm Reduction Act which allows up to six cities in New Jersey to establish syringe access programs. The recent state legislative battles in states like Massachusetts and New Jersey have been difficult and expensive; though drug and AIDS advocacy groups such as the Drug Policy Alliance, ACT UP and some state AIDS organizations have provided resources to fight these tough legal battles.

In other areas, AIDS advocacy groups and harm reduction advocates argue that government inaction created a political opportunity structure that enabled harm reduction activists to set up SEPs in some localities (Bluthenthal, 1998). Although the endorsement of public health officials and evidence-based research can be essential to bringing SEPs into being, AIDS advocacy groups and harm reduction advocates argue that government inaction created a political opportunity structure that enabled harm reduction activists to set up SEPs in some localities (Bluthenthal, 1998). The combined efforts of local activists, health service providers, researchers, and drug injectors who recognized the need for social and political change has led to the design and implementation of effective harm reduction effort developed from the failure of federal policymakers to effectively respond to the epidemic among IDUs.

(2) Neighbors and businesses

Opposition to SEPs among neighbors and businesses varies widely. Stigma against drug users, and prejudices attached to drug use contribute to local NIMBY arguments by neighbor and businesses in the areas where SEP services are located. In some cases, local organized resistance against SEPs can come from within minority communities and religious groups (Shaw, 2006; Tempalski, 2005). In other situations opposition can come from the belief that distributing clean needles encourages drug use or it is morally wrong, or in some neighborhoods where SEPs are located.

“Opposition is diffuse here. You’re getting some religious opposition but then you’re getting some religious support. You’re getting some, “you’re giving drugs to needle users”, from people who really have no scientific backing or background, but just pulling things out saying it encourages drug use.” [MSA9]

Resistance to SEPs does not exist in isolation and different players can generate opposition to SEPs. For example, neighbors and businesses can put pressure on local politicans or client providers to make a program re-locate, or local business interests can force rezoning of many health-related and other service type facilities. There was one such case in an MSA where street-outreach services to IDUs were located in a downtown area for years; when up-scale businesses moved into the area the program was forced to move:

“We’ve had local opposition here. There’s some NIMBY-ism. The needle exchange resides on a seedy block that connects the market district with the retail core where the large department stores are. That location is problematic. That street is problematic to downtown, for pleasant innocuous kinds of shopping trips or for the tourist trade or for the interests of development. So that’s a conflict and we are currently being pressured to move and are facing a pretty difficult time of trying to find a location. So it’s a tough thing. We get a lot of opposition in that way. We have until the end of the month to be out of the facility… We’re working out of a van for the moment, trying to find a place to move to. We’re doing guerrilla needle exchange.” [MSA10]

The forced re-location of services in the above example can be interpreted as an element of socio-spatial exclusion of a marginalized group from the city core for the sole purposes of presenting an attractive consumption space (as suggested by Fischer et al., 2004). In this situation opposition was expressed through local businesses, these services were moved to a much less convenient, somewhat isolated area where transportation is lacking. As a result, fewer people now access outreach services offered at the new location.

In this research we have found that opposition toward SEPs extends beyond local NIMBY resistance and into the broader political spheres where harm reduction has been resisted and stigmatized by powerful national, state and local governmental actors. Federal, state and local governments in the U.S. have been resistant to a harm reduction approach, and encourage a philosophy of hate and fear toward drug users. Thus, we extend the concept of resistance toward human services from the local-NIMBY level to higher systemic levels of government and national culture. As a result, this research moves beyond traditional notions of localized-NIMBY to suggest a new theoretical concept based on resistance to syringe exchange programs in the U.S.

Extending the NIMBY Paradigm: IEA

Both “political changes” and “opposition from neighbors and businesses” can transform a supportive SEP environment into a contentious, anti-SEP environment. For example, in a state where syringe exchange programs had been legal since 1997, the interaction of state and local politics including a strong anti-SEP community presence shaped the policy outcome of this long-standing program. Opposition from neighbors in alliance with local businesses pressured city council members to close the SEP. As a result, in the fall of 2001, the city council passed a zoning law that directly contradicted the intention of the state law. The then new mayor declared his opposition to the SEP, and police behavior changed from active support, where an officer might occasionally drive an IDU to the exchange, to outright harassment. The social and political landscape was such that it forced the long standing SEP to close. One state health official characterized the events as follows:

“There have been arrests, most recently since the new mayor took office; there has been a whole change in the police attitude and they have been arresting folks holding clean syringes, SEP syringes, arresting them and taking them to the jail, but then releasing them the next day, dropping the charges because they know it won’t stick. So it’s just a form of harassment.”

With regards to SEPs in the US, there appears to be a system of nationally-based institutionalized exclusion that concretizes state and local stigmatizing of drug users into an informal (or, sometime formal) alliance of local politicians and of local-elite-led opposition to services for them. In some cases, state politicians have prevented government workers from publicly or privately supporting or working for a SEP. One ex-government employee had this to say:

“As a matter of fact, state employees under the [current] administration were required, and I mean required, to not support it publicly or privately, were warned if they said anything favorable about it..and in fact were required to vote against any motion to support it. In other words, if a Ryan White planning council voted, and there was a state employee there, we were supposed to vote against it. So most of us abstained and made a big deal out of abstaining while the rest of the council just laughed at us… Oh, and it was draconian. They weren’t kidding. The word got down and you were told to tone it down, to zero. So they forced us underground, most of us.”

Thus, we suggest that there are similar institutionalized systems of exclusion for other groups who are socially designated as legitimate targets for scorn and/or hatred. This concept of IEA is broader than the NIMBY concept per se in several ways: (1) it captures the rooting of service-exclusion in local and national patterns of stigma. Thus, we would hypothesize, similar patterns of exclusion of services would be expected in situations where racial, ethnic or religious groups, the poor, or similar groups were targeted by stigma; (2) it goes beyond the neighborhood actors in the situation and highlights their ties to local politicians and business interests and perhaps to national elites as well; (3) it problematizes the forms of alliance or other more implicit forms of cooperation among these various actors for future research and, perhaps, for persuasion or attack by proponents of services for stigmatized groups; and (4) it suggests that NIMBY supporters are not simply victims of invasion by unwanted service institutions, nor simply “local people,” but that they may be part of widespread networks and organized powers of exclusion.

Discussion

Public health strategies such as using a sterile syringe for every injection are designed to reduce the transmission of blood-borne diseases. The public health approach thus seeks to provide IDUs with the means to protect themselves against HIV and other diseases. This approach differs drastically from current U.S. legal, policy framework and law enforcement responses to the social and health problems associated with injection drug use. These present formidable obstacles to public health strategies to prevent HIV among IDUs, rendering it much more difficult to acquire sterile syringes, and reduce injecting risk environments. Understanding place-based factors associated with community acceptance and policy implementation of programs for IDUs can help guide effective strategies to foster the implementation of interventions to help reduce drug-related harm in areas where programs are urgently needed.

In many localities, prejudice attached to drug use is reinforced by the illegal and covert nature of illicit drug use and by the depiction of drug users as lower class and/or as members of stigmatized races and ethnicities. Often, then, it is not a negative experience with syringe exchange that leads to opposition to these services, but the overall judgment that drug users are evil or unpleasant to have around. As a consequence, stigma associated with drug use marks both IDUs and individuals and programs who work with them. Social and spatial stigma surrounding injection drug use and HIV have dramatic consequences for substance users seeking help, and for the kinds of treatment and prevention structures that national and state policymakers are willing to support, in particular structures based on the philosophy of harm reduction. As a result, a large proportion of injectors remain unable to access sterile syringes or clean injection equipment, and since SEPs are an important entry into drug treatment and HIV counseling and testing, the lack of such programs means that many IDUs lack full access to health services in general. These factors affect the utilization, implementation and siting of services for marginalized and vulnerable groups. Additionally, place-based stigmatization also affects clients of these services, who may be reluctant to utilize the services due to the stigma attached to persons and place.

National policy response and socio-cultural norms toward the HIV epidemic and IDUs have shaped the nature and quality of services for users in need of them. As a result, IDUs are near the bottom in terms of social tolerance in the hierarchy of client groups and in terms of services that federally policy-makers are willing to fund. And, although drug use happens everywhere, it is only when poor people or minorities use drugs that it becomes a moral crisis, raising issues related to social exclusion and place; and in particular who is socially acceptable to access public space.

In many parts of the world, SEPs have been accepted as essential components of HIV and hepatitis C prevention. The U.S. is however the outstanding exception. Legal access to syringes either through pharmacy sales or SEPs remains difficult in most parts of the country. Federal funding for SEPs continues to be withheld. Despite their proven effectiveness in HIV prevention and despite support from local public health authorities and research institutions, SEPs remain a controversial issue in the United States. They face ongoing obstacles from the government, funding constraints, disapproving attitudes of local residents or business associations, and police harassment of clients and service providers. As such, explaining the underlying socio-cultural and political environment for maintaining and establishing syringe exchange programs and other HIV prevention programs such as drug treatment and outreach, all of which have been shown to reduce HIV risk behaviors and the spread of HIV, is of clear policy relevance. Here action is localized rather than national where place-based factors are likely to affect whether different interventions are established. Knowledge of these factors can help program planners determine how to facilitate their spread. The extent to which program need and presence are associated will indicate whether current allocation and initiation processes are working. If substantial levels of unmet need exist for such programs, serious policy discussions about the next steps to take will become even more urgent.

Although some states and local communities have responded appropriately to the void created by the federal ban on funding for SEPs, the role of the federal government remains vitally important. Lifting the federal ban would allow existing SEPs to substantially expand their services, and it would increase communication among different types of programs (e.g., between underground programs and those receiving state and local funds) and between similar government-sponsored services for IDUs. It would also send a clear signal that the federal government is invested in preventing the transmission of HIV among IDUs (Clear, personal communication, 2006).

Concluding Remarks

This paper adds to the current literature on localized resistance to human service facilities and political opposition toward SEPs which maintains that opposition to SEPs is embedded in local socio-cultural norms from residents and political attitudes that conflate drug use, stigma attached to being HIV-positive, and moral issues relating to IDUs access to sterile syringes. It emphasizes how place-based political, social, and economic processes—such as national economic relations and inequalities, “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY)–type community responses, and grassroots activism—affect the geographies of health care services for people with HIV/AIDS and other stigmatized groups. Thus, the present research improves our understanding of the geography of HIV/AIDS services in the hidden and highly stigmatized population of IDUs; while shedding light on the socio-cultural and political factors that underlie the systematic rejection of government funding of SEPs in the United States. The perspective of such opposition as being based on nationally-institutionalized IEA should aid harm reduction activists and other proponents of human services in planning how to resist such opposition more successfully and thus in expanding and spreading programs that protect human health and comfort.

In the U.S., grassroots activists continue to influence and implement HIV prevention efforts to help reduce harm associated with injection drug use. Basing the location of prevention services on the characteristics of the population in need will maximize the impact of such services. The factors defining need are best determined by the people who are actually braving the crisis, not by government policies based on fear and exaggeration. Grassroots efforts, such as those of the harm reduction movement, defy the despotic nature of negative public policies, and work toward building solidarity for developing and designing HIV prevention services for stigmatized groups.

As such, this research brings to light an attitude of rejection of services to those populations most vulnerable in the U.S. That is, what SEPs are confronted with is an attitude of rejection and resistance that is firmly entrenched in our culture and national perceptions toward drug users. Thus, we have found, as often is the case, that this is a script by which action can be organized.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse grant R01 DA13336 (Community Vulnerability and Response to IDU-related HIV)

The work described in this paper is drawn from on-going research on the Community Vulnerability and Response to IDU-Related HIV project at the National Development and Research Institutes., Inc. (supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse grant # R01 DA13336). Special thanks to peer-reviewers for their help with the conceptual framework, and Moriah M. McGrath and Dr. John Jost for their editorial suggestions during the writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Underground programs usually do not have the formal support of local elected officials. In most cases these programs function below the radar of law enforcement.

In order to make our categories for regions more homogeneous politically, culturally and economically, US Census categories for Region were adjusted by moving Maryland, Delaware and Washington, DC to the Northeast Region; Texas to the West; and Oklahoma to the Midwest.

In 1990, Congress enacted The Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act or Ryan White Care Act, the United States’ largest federally funded program (excluding Medicaid and Medicare) for the care of those living with HIV and AIDS

Community experts are defined as professionals and activists working in the fields of HIV prevention, drug treatment or HIV public policy. Experts interviewed were researchers, program managers, clinic directors, and advocates for services for injection drug users.

For confidentiality reasons, reporting of some cities, programs or individuals has been restricted.

A few states have amended drug paraphernalia laws by excluding syringes and injection equipment.

New York, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Maine have deregulated sales of up to 10–30 clean syringes. California, Delaware, Vermont, District of Columbia, Virginia, Kansas, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania require prescriptions to buy syringes.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aitken C, Moore D, Higgs D, Kelsall J, Kerger M. The impact of a police crackdown on a street drug scene: Evidence from the street. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13:189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo AA, Reynolds NR. Stigma, HIV, and AIDS: An exploration and elaboration of a stigma trajectory. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41:303–315. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Bar Association, AIDS Coordinating Committee. Deregulation of hypodermic needles and syringes as a public health measure: a report on emerging policy and law in the United States. ABA, AIDS Coordination Project; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R, Flint J. Localing the local in informal processes of social control: The defended neighbourhood and informal crime management. Centre for Neighbourhood Research paper 10, School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol and the Department of Urban Studies at the University of Glasgow. 2003 http://www.neighbourhoodcentre.org.uk, Downloaded Feb 2007.

- Bluthenthal RN, Kral AH, Erringer EA, Edlin BR. Drug Paraphernalia Laws and Injection-Related Infectious Disease Risk Among Drug Injectors. Drug Issues. 1999a;22:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Lorvick J, Kral AH, Erringer EA, Kahn JG. Collateral damage in the war on drugs: HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 1999b;10:25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN. Syringe exchange as a social movement: A case study of harm reduction in Oakland, California. Substance Use and Misuse. 1998;33:1147–1171. doi: 10.3109/10826089809062212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Kral AH, Lorvick J, Watters JK. Impact of law enforcement on syringe exchange programs: a look at Oakland and San Francisco. Medical Anthropology. 1997;18:61–83. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1997.9966150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Lettiere M, Quesada J. Social misery and the sanctions of substance abuse: Confronting HIV risk among homeless heroin addicts in San Francisco. Social Problems. 1997;44:155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan D, Shaw S, Ford A, Singer M. Empirical science meets moral panic: an analysis of the politics of needle exchange. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2003;24:427–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chiotti QP, Joseph AE. Casey house: Interpreting the location of a Toronto AIDS hospice. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41:131–140. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00304-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clear A. Personal communication. Executive Director. Harm Reduction Coalition; New York City, New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Colon I, Marston B. Resistance to a residential AIDS home: An empirical test of NIMBY. Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;37:135–145. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n03_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. The Impact of a Police Drug Crackdown on Drug Injectors’ Ability to Practice Harm Reduction: A Qualitative Study. Social Science and Medicine. 2005a;61:673–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Friedman S, Tempalski B, Friedman R, Keem M. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Injection Drug Use in 94 U.S. Metropolitan Statistical Areas in 1998. Annals of Epidemiology. 2005b;15:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtwright D, Joseph H, Des Jarlais D. Addicts who survived: An oral history of narcotic use in America, 1923–1965. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Daker-White G. Drug user’s access to community-based services. Health & Place. 1997;3:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, Burris S, Kraut-Becher KG, Lynch KG, Metzger D. Effects of an intensive street-level police intervention on syringe exchange program use in Philadelphia, PA. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:233–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear MJ, Wolch JR. Landscapes of despair: From deinstitutionalization to homelessness. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dear M, Wilton R, Gaber SL, Takahashi LM. Seeing people differently: The sociospatial construction of disability. Environment and Planning: Society and Space. 1997;15:455–480. [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC. Research, politics, and needle exchange. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1392–1394. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Paone D, Friedman SR, Peyser N, Newman RG. Public health then and now: Regulating controversial programs for unpopular people: Methadone maintenance and syringe-exchange programs. American Journal of Public Health. 1995a;85:1577–1584. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.11.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Hagan H, Friedman SR, Friedmann P, Goldberg D, Frischer M, Green S, Tunving K, Ljungberg B, Wodak A, Ross M, Purchase D, Millson ME, Myers T. Maintaining Low HIV Seroprevalence in Populations of Injecting Drug Users. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995b;274:1226–1231. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.15.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England MR. Doctoral Dissertation. Department of Geography; University of Kentucky: 2006. Citizens on patrol: Community policing and the territorialization of public space in Seattle, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Poland B. Exclusion, “risk,” and social control: Reflections on community policing and public health. Geoforum. 1998;29:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Turnbull S, Poland B, Haydon E. Governing drug use: Supervised Injection Facilities as a case study in the government of health, risk and space. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2004;15:357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR. The political economy of drug-user scapegoating and the philosophy and politics of resistance. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy. 1998;5:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR. Doctoral Dissertation. The University of Michigan; 1970. Political Issues in Cities. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Tempalski B, Cooper H, Perlis T, Keem M, Friedman R, Flom PL. Estimating numbers of IDUs in metropolitan areas for structural analyses of community vulnerability and for assessing relative degrees of service provision for IDUs. Journal of Urban Health. 2004;8:377–400. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Cooper HL, Tempalski B, Keem M, Friedman R, Flom PL, Des Jarlais DC. Relationships of deterrence and law enforcement to drug-related harms among drug injectors in US metropolitan areas. AIDS. 2006;20:93–99. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196176.65551.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg S. The estimated prevalence and incidence of HIV in 96 large U.S. metropolitan areas. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:642–654. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.5.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley SF, Jolley DJ, Kaldor JM. Effectiveness of needle-exchange programs for prevention of HIV infection. The Lancet. 1997;21:1797–1800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Heimer R. A Circulation Theory of Needle Exchange. AIDS. 1994;8:567–574. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns RA, Joseph AE. Space in its place: Developing the link in medical geography. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;37:711–717. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90364-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keem M, Friedman R, Tempalski B, Friedman SR. Community reactions to services for IDUs: Learning from support and opposition. Published abstract National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, GA. 27–30 July 2003.2003. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Davey MA, Hua W. Social context of needle selling in Baltimore, Maryland. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:901–13. doi: 10.1080/10826080600668720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law R. Communities, citizens, and the perceived importance of AIDS-related services in West Hollywood, California. Health and Place. 2003;9:7–22. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(02)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law RM, Takahashi LM. HIV, AIDS and human services: Exploring public attitudes in West Hollywood, California. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2000;8:90–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low S. Behind the gates: Life, security, and the pursuit of happiness in fortress America. Routledge; New York, N.Y.: [Google Scholar]

- Lurie P, Drucker E. An opportunity lost: HIV infections associated with lack of a national needle-exchange programmes in the USA. The Lancet. 1997;349:604–608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05439-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie P, Reingold A, Bowser BP, Chen D, Foley J, Guydish J, Kahn JG, Lane S, Sorensen JL. The public health impact of needle-exchange programs in the United States and abroad. Berkeley, CA: U. California, Berkeley, School of Public Health; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon-Callo V. Making sense of NIMBY: poverty, power and community opposition to homeless shelters. City & Community. 2001;13:183–209. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald M, Law M, Kaldor J, Hales J, Dore G. Effectiveness of needle and syringe programmes for preventing HIV transmission. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2004;14:351–352. [Google Scholar]

- Maher L, Dixon D. Policing and public health: Law enforcement and harm minimization in a street-level drug market. British Journal of Criminology. 1999;39:488–512. [Google Scholar]

- Mann J, Tarantola M, editors. AIDS in the world II: Global dimensions, social roots, and responses. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell D. The right to the city: Social justice and the fight for public space. The Guilford Press; New York, N.Y.: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Musto DF. The American disease: Origins of narcotic control. New York: Oxford U. Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services. New Jersey HIV/AIDS Cases Report. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Paone D, Des Jarlais DC, Clark J, Shi Q. Syringe-Exchange Programs in the United States: Where Are We Now? AIDS & Public Policy Journal. 1996;11:144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paone D, Des Jarlais D, Clark J, et al. Update: Syringe-exchange programs--United States, 1996. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1997;46:565–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paone D, Clark J, Shi Q, Purchase D, Des Jarlais DC. Syringe Exchange in the United States, 1996: A National Profile. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:43–46. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purchase D. Personal communication. Director, Point Defiance AIDS Projects, and the North American Syringe Exchange Network. 2003.

- Rich JD, Strong L, Towe CW, McKenzie M. Obstacles to needle exchange participation in Rhode Island. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:396–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Kimber J, Small W, Fitzgerald J, Kerr T, Hickman M, Holloway G. Public injecting and the need for ‘safer environment interventions’ in the reduction of drug-related harm. Addition. 2006;101:1384–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling RF, Fontdevila J, Fernando D, El-Bassel N, Monterroso E. Proximity to needle exchange programs and HIV-realted risk behavior among injection drug users in Harlem. Evaluation and Planning. 2004;27:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Soja EW. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. Vol. 70 1980. The Socio-spatial dialectic. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SJ. Public Citizens, Marginalized Communities: The Struggle for Syringe Exchange in Springfield, Massachusetts. Medical Anthropology. 2006;25:31–63. doi: 10.1080/01459740500488510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SJ. Injection drug users & HIV risk: results from the syringe access, use and discard study, Springfield, MA. Oral presentation at: North American Syringe Exchange Conference, XII; Albuquerque, N.M.. April.2002. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM. Geography and social justice. Cambridge, MA.: Blackwell Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Strike CJ, Myers T, Millson M. Finding a place for needle exchange programs. Critical Public Health. 2004;14:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi LM. Homelessness, AIDS, and stigmatization. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B. The Uneven Geography of Syringe Exchange Programs in the United States: Need, Politics and Place. Department of Geography, University of Washington; 2005. Doctoral Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Burris S. Spatial variations of legality, funding and services among U.S. SEPs. Published abstract 14th International Conference on the Reduction of Drug Related Harm; Chiang Mai, Thailand. 6–10 April.2003a. [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC, McKnight C, Keem M, Friedman R. What predicts which metropolitan areas in the USA have syringe exchange programs? International Journal on Drug Policy, Special Issue on syringe exchange and access. 2003b;14:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. 2000 Metropolitan Statistical Area Definitions. Population Division, Population Distribution Branch; [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Des Jarlais DC, Goosby E, Hollinger PC, Lurie PG, Shiver MD, Strathdee S. Needle exchange programs for the prevention of human immuno-deficiency virus infection: Epidemiology and policy. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154:S70–S77. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.s70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton RD. The constitution of difference: Space and psyche in landscapes of exclusion. Geoforum. 1998;29:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wolch J, Philo C. From distribution of deviance to definition of difference: Past and future mental health geographies. Health and Place. 2000;6:137–157. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(00)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, Jones J, Schecter MT, Tyndall MW. The impact of police presence on access to needle exchange programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:116–118. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200309010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibbell J. Personal communication, Chair Springfield Massachusetts Users Council. 2006. [Google Scholar]