Abstract

The decision whether or not a cell undergoes apoptosis is determined by the opposing forces of pro- and antiapoptotic effectors. Here we demonstrate genetically that estrogen can tip this balance toward cell survival in uterine epithelial cells by inducing the expression of baculoviral inhibitors of apoptosis repeat-containing 1 (Birc1), a family of antiapoptotic proteins. In neonatal mice, both 17β-estradiol and the potent synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol strongly suppress uterine epithelial apoptosis while markedly elevating Birc1 transcript level in an estrogen receptor-α-dependent manner. The induction of Birc1 before any effect on apoptosis suppression and failure of diethylstilbestrol to completely inhibit apoptosis in Birc1a-deficient uterine epithelium indicate a functional role for Birc1a in estrogen-mediated apoptosis suppression. In ovariectomized adult mice, expression of Birc1 is also induced by ovarian hormones, suggesting a role for these proteins in normal uterine physiology. We propose that by binding to active caspases, Birc1 proteins can eliminate them through proteasome degradation. These results for the first time establish Birc1 proteins as functional targets of estrogen in suppressing apoptosis in the uterus.

APOPTOSIS, OR PROGRAMMED cell death, plays a number of fundamental roles during embryogenesis, carcinogenesis, and host defense (1). Two major apoptotic pathways have been described in mammals: the extrinsic death-receptor signaling pathway and the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. The former involves ligand-receptor interactions, intracellular adaptor proteins, and autoactivation of an initiator caspase, procaspase-8 (2,3,4,5,6). The latter involves the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, which then binds to apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (Apaf-1). Apaf-1 in turn recruits an initiator caspase, procaspase-9, to form the apoptosome that leads to the activation of caspase-9 (7,8,9,10). From here, the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways converge on the activation of executioner caspases 3 and 7 to generate active forms of these cysteine proteases. Active caspase-3 and -7 cleave more than 200 cellular target proteins, which leads to the final destruction of the cell (11). Several levels of control mechanisms exist in the regulation of the intrinsic cell-death pathway. First, regulation of cytochrome c released into the cytoplasm is conferred by the Bcl-2 family proteins (12,13). Second, the assembly of apoptosome can be regulated by the intracellular dATP concentration and by oncoprotein prothymosin-α (9,14,15). Finally, the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family of proteins can bind to active caspases and either directly inhibit their enzyme activities or subject them to ubiquitin-proteasome degradation (16,17).

The IAP proteins were first identified in baculovirus and contain the baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domains (18,19). They are highly conserved during evolution and inhibit cell death in a variety of species. The most extensively studied member of the human IAP family is XIAP (BIRC4). Located on the X-chromosome, XIAP is proposed to be the only IAP that is capable of inhibiting the enzyme activity of caspases (20). On the other hand, an evolutionarily conserved role for IAPs appears to be caspase removal by the ubiquitin-targeted proteasome degradation, as has been observed in Drosophila IAP (21). The neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein (NAIP), or BIRC1, was first identified by positional cloning as the candidate gene for spinal muscular atrophy (22). In the mouse, amplification of the Birc1 locus resulted in five to seven Birc1 genes depending on the strain (23). Current evidence suggests that in mice, individual Birc1 genes may have distinct functions. Birc1e, mapped to the Lgn1 locus, is associated with resistance to Legionella pneumophila infection (24). On the other hand, Birc1a does not appear to have this function, and Birc1a knockout mice are viable and display increased neuronal death when exposed to kainic acid (25). BIRC1 can physically interact with active caspase-3 and -7 and with active caspase-9 in the presence of ATP, but it is unclear whether it can directly inhibit their enzyme activities (26,27). Birc1 proteins contain BIR domains that can directly bind to active caspases, a NACHT domain believed to be an oligomerization domain where signaling components assemble, and multiple LRR domains believed to be protein-protein interaction domains involved in pathogen sensing. However, the precise mechanism by which the Birc1 proteins inhibit apoptosis remains unclear.

It has been known for more than a decade that estrogens can have opposing effects on cellular apoptosis in various organs including the male and female reproductive tracts (28,29,30). During uterine development, apoptosis serves to eliminate excess cells, sculpture the luminal shape, and maintain simple columnar lining of the uterus. We and others have shown that neonatal treatment with a synthetic estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES), can potently suppress apoptosis in the uterine epithelium (31,32). Neonatal exposure to DES in mice can lead to multiple patterning defects in the female reproductive tract and uterine cancer. In addition, both estrogen and progesterone have recently been shown to have an antiapoptotic effect on the uterine epithelium during embryo implantation (33). Components involved in apoptosis have been shown to be regulated by estrogen; however, their involvement in inhibiting uterine epithelial apoptosis remains unclear (34,35,36). In this paper, we provide genetic evidence that Birc1 proteins play active roles in this process. Our results establish Birc1 genes as important players in estrogen-mediated apoptosis suppression in the uterine epithelium and provide a molecular explanation for estrogen-induced apoptosis inhibition.

RESULTS

DES and 17β-Estradiol (E2) Disrupt the Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway

Neonatal exposure to DES leads to a dramatic suppression of apoptosis in the developing mouse uterine epithelium (31,32). To confirm that this effect is caused by the estrogenic activity of DES, we compared the effect of E2 on neonatal uterine epithelial apoptosis with that of DES. Neonatal C57BL/6J female pups received oil, 2 μg/pup·d DES, or 20 μg/pup·d E2 for five consecutive days beginning at postnatal d 1 (P1) (37,38). This pharmacological dose of E2 was used because previous studies showed that at this dose, E2 can elicit reproductive tract lesions similar to those treated with DES (38). At P5, a significant percentage of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells (19.45 ± 4.70%; see Fig. 5G) were observed in control uterine epithelium, consistent with previous studies (31), whereas DES treatment completely abolished apoptotic cells in the uterine epithelium (Fig. 1, A and D). Treatment with E2 also completely inhibited uterine apoptosis (Fig. 1G).

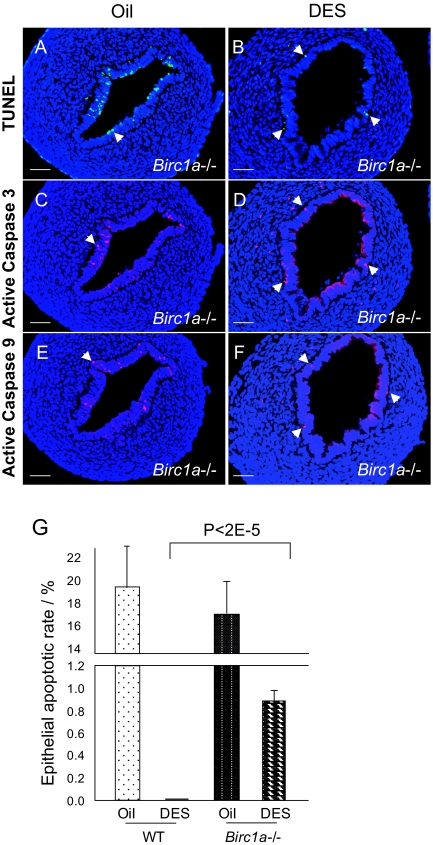

Figure 5.

DES Failed to Completely Suppress Apoptosis in Birc1a-Deficient Uterine Epithelium

A, TUNEL assay revealed that Birc1a mutant uterine epithelium contained a normal number of apoptotic cells. B, DES treatment, however, failed to completely suppress uterine epithelial apoptosis. Apoptotic cells that are TUNEL positive were located near the basal membrane of luminal epithelium (arrows). C–F, Active caspase-3 and -9 are detected in DES-treated Birc1a mutant uteri assayed by immunofluorescence double labeled with TUNEL and on adjacent sections, respectively. Arrows indicate cells that are positive for either activated caspase. Bars, 50 μm (A–F). G, Quantification of uterine epithelial apoptotic rate revealed that the baseline apoptotic rates were 19.45 ± 4.70 and 17.06 ± 3.25% in wild-type and Birc1a mutant oil-treated uteri, respectively (not statistically significant, P = 0.25). DES-treated Birc1a mutant had 0.88 ± 0.06% apoptotic cells, whereas the wild-type counterpart had none (P < 2−5). n = 5. Error bars represent sem.

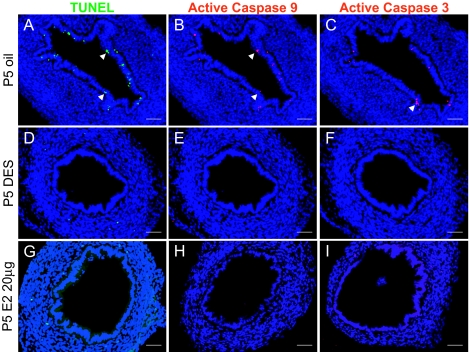

Figure 1.

Both DES and E2 Suppress Uterine Epithelial Apoptosis by Abolishing Active Caspases-3 and -9

A, Apoptotic cells were detected in P5 oil control uterine epithelium by TUNEL (arrows). In contrast, no TUNEL-positive cells were detected when treated with either DES or E2 (D and G, respectively). B and C, Immunofluorescence revealed that active caspase-9 and -3 were present in the oil-treated control uterine epithelium (arrows). Note that some cells positive for TUNEL were also positive for active caspase 9 (double labeling) and active caspase 3 (adjacent section) (compare B and C with A). E and F, DES-treated uteri were negative for active casepase-9 or -3 staining. Similar results were observed in E2-treated uteri (H and I). The nuclei in all figures were stained with Hoechst 33258 and appeared blue. n = 5 in each group. Bars, 50 μm (A–I).

To probe into the mechanisms underlying this inhibitory process, we examined the activation status of caspase-9 and caspase-3 by immunofluorescence with rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for active forms of these proteins. Active caspase-9 and -3 were detected in a fraction of luminal epithelial cells in oil-treated uterus, some of which are also TUNEL positive (Fig. 1, B and C), but were absent in the DES-treated group (Fig. 1, E and F). E2 treatment produced the same inhibitory effect on caspase activation (Fig. 1, H and I) (n = 5 in each group). We also tested lower doses of E2 (5, 50, and 200 ng/pup·d from P1–P5), but these treatments did not result in a complete repression of apoptosis, nor did they eliminate active caspases expression (supplemental Fig. S1, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org). These results suggest that DES, as well as E2, prevent luminal epithelial apoptosis by affecting the steady-state levels of active caspase-9 and -3. However, it is equally possible that E2 or DES can repress the transcription of caspase-9 and -3 genes. To rule out this possibility, we performed RT-PCR to assess the mRNA levels for these two genes with or without hormone treatments. The results clearly showed that neither DES nor E2 significantly affected the abundance of either transcript (n = 3) (Fig. 2A). These results demonstrate that during development, a fraction of uterine epithelial cells undergo apoptosis by activating the caspase-9-mediated intrinsic apoptotic pathway, and this process is completely blocked by neonatal estrogen exposure.

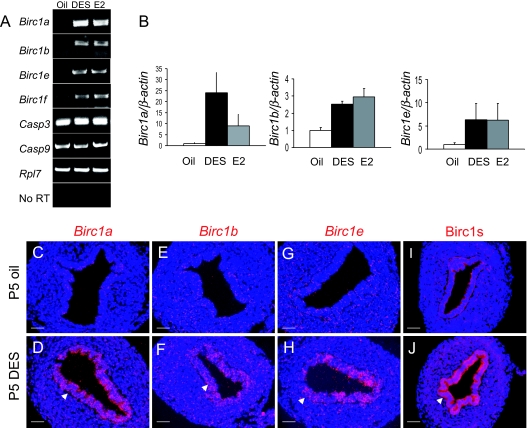

Figure 2.

Regulation of Birc1 Genes by DES and E2

A, Expression of Birc1a, -1b, -1e, and -1f was up-regulated by DES and E2 as assayed by RT-PCR in P5 mouse uteri. The expression of caspase-3 and -9, on the other hand, was not regulated by either hormone treatment. B, Real-time RT-PCR revealed fold-changes of Birc1a, -1b, and -1e upon DES and E2 treatment. C–H, 35S in situ hybridization showed that the induction of Birc1a, -1b, and -1e by DES was confined to the uterine epithelium (arrows). I and J, Immunofluorescence with an antibody that recognize mouse Birc1a, -1b, -1e, -1f, and -1g revealed uterine epithelial specific staining in DES-treated uteri (arrow). n = 3. Bars, 50 μm (C–J).

Estrogen Induces Birc1 Gene Expression in Neonatal Uterine Epithelium through Estrogen Receptor (ER)-α

Our previous microarray data revealed that Birc1a was up-regulated by an average of 6.9-fold upon DES treatment (32). This finding prompted us to test the hypothesis that Birc1a and possibly other Birc1 genes are involved in DES-mediated inhibition of apoptosis. First, RT-PCR analyses were performed to verify the microarray result on RNA isolated from P5 oil- and DES-treated uterine samples (n = 3). Expression of Birc1a, -1b, and -1e was barely detectable in the oil-treated group; it was markedly up-regulated in the DES-injected group, whereas that of Birc1f was slightly up-regulated and that of Birc1c and -1g was not (Fig. 2A and data not shown). Administration of E2 elicited a similar response (Fig. 2A). Transcript levels of Birc1 genes induced by both DES and E2 were quantified by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 2B). The magnitude of Birc1 induction by lower E2 doses (50 and 200 ng/pup·d) was much lower compared with DES or a high dose of E2 as assayed by real-time RT-PCR (supplemental Fig. S2). The fact that lower E2 doses failed to completely inhibit uterine epithelial apoptosis suggests the requirement for a threshold level of Birc1 gene expression to inhibit apoptosis. Because DES and E2 caused the same biological response in this context, only DES was used in subsequent experiments involving neonatal mice. In situ hybridization confirmed the up-regulation and showed that Birc1a, -1b, and -1e mRNAs were localized to the uterine epithelium, where suppression of apoptosis was observed (Fig. 2, C–H). Moreover, immunofluorescence with a rabbit polyclonal antibody that recognizes the mouse Birc1a, -1b, -1e, -1f, and -1g proteins showed strong signals in the DES-treated uterine epithelium but not in oil-treated controls (Fig. 2, I and J). In contrast, expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 was not altered upon DES treatment (supplemental Fig. S3). Together, these results for the first time established Birc1 genes as targets of estrogen in the uterus and suggested that estrogen represses apoptosis via Birc1 proteins.

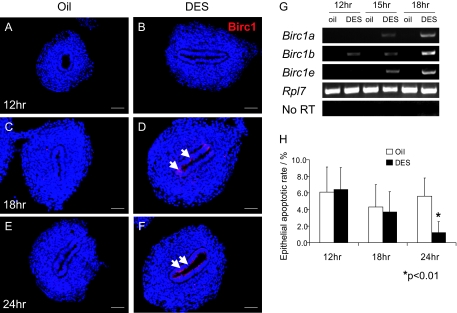

If Birc1 proteins mediate estrogen suppression of apoptosis, then the induction of Birc1 expression by estrogen should occur before its inhibitory effect on apoptosis. In support of this notion, a time-course RT-PCR experiment on P1 pups revealed that Birc1b transcript level was elevated as early as 12 h after DES injection, with Birc1a and -1e being induced at 15 h (Fig. 3G). Birc1 protein was not detected at 12 h but was expressed in the uterine epithelium at 18 and 24 h after DES treatment, as assayed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 3, A–F). By 18 h, there was no significant difference between the apoptotic rates in oil- and DES-treated uterine epithelia (4.32 ± 2.71 vs. 3.67 ± 2.45%, P = 0.31; n = 3). Only after 24 h was the apoptotic rate significantly lower in DES-treated uterine epithelia compared with oil-treated controls (1.20 ± 0.13 vs. 5.64 ± 2.21%, P < 0.01; n = 3) (Fig. 3H). The fact that up-regulation of Birc1s precedes apoptosis inhibition is consistent with the hypothesis that Birc1 induction by estrogen leads to the suppression of apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Induction of Birc1s Precedes Apoptosis Suppression by DES Treatment

A–F, Immunofluorescence of Birc1 revealed that DES induced Birc1 expression as early as 18 h after the first injection, and the induction persisted at 24 h (arrows point to positive Birc1 staining). G, RT-PCR analysis showed that Birc1b was induced 12 h after DES treatment, whereas Birc1a and -1e were induced by 15 h. H, A significant decrease in epithelial apoptotic rate conferred by DES treatment was observed only at 24 h (oil vs. DES: 5.64 ± 0.05 vs. 1.20 ± 0.13%, P < 0.01) but not at earlier time points (6.13 ± 3.03 vs. 6.42 ± 2.66% at 12 h and 4.32 ± 2.71% vs. 3.67 ± 2.45% at 18 h). Error bars represent sem. Bars, 50 μm (A–F).

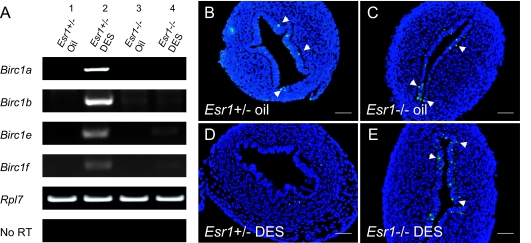

Previous studies demonstrated an obligatory role for ER-α in the teratogenic effect of DES on the reproductive tracts (39,40,41). To address whether DES inhibits apoptosis and induces expression of Birc1s through ER-α, we examined uterine apoptosis and Birc1 induction in P5 Esr1−/− pups treated with DES from P1-P5. Expression of Birc1a, -1b, -1e, and -1f was potently induced by DES in Esr1+/− uteri (Fig. 4A). In contrast, Birc1e and -1f were only marginally induced by DES in Esr1−/− uteri, whereas Birc1a and -1b were not induced at all (Fig. 4A). TUNEL staining revealed a similar apoptotic rate between oil-treated Esr1+/− and Esr1−/− uteri (Fig. 4, B and C) (n = 3). However, although DES potently suppressed apoptosis in Esr1+/− uterine epithelia (Fig. 4D), it failed to do so in Esr1−/− mice (Fig. 4E) (n = 3). These results demonstrate that ER-α is principally required in neonatal mice for DES to induce uterine Birc1 expression and to suppress apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Transcriptional Regulation of Birc1s by DES Is Mediated via Esr1

A, RT-PCR of Birc1a, -1b, -1e, and -1f showed that all the genes were up-regulated by DES in Esr1+/− uterus on P5 but were minimally responsive to DES treatment in Esr1−/−. B and C, TUNEL staining revealed no significant difference in uterine epithelial apoptosis between Esr1+/− and Esr1−/− mice on P5. D and E, DES treatment resulted in a complete abolishment of TUNEL-positive cells in Esr1+/− uteri (D) but had no effect on epithelial apoptosis in Esr1−/− uteri (E). Arrows indicate apoptotic cells in the uterine epithelium. n = 3. Bars, 50 μm (B–E).

Birc1a Is Required in a Subset of Uterine Epithelial Cells to Suppress Apoptosis

Our data suggest that estrogen exerts its antiapoptotic effect on uterine epithelial cells by inducing the expression of Birc1 proteins, which presumably bind and eliminate active caspase-3 and -9. If this hypothesis is correct, removing Birc1 genes should compromise the ability of estrogen to suppress apoptosis. Because mice lacking the entire Birc1 locus are not available, we used Birc1a mutant mice to examine its function in DES-induced apoptosis suppression. Birc1a mutant mice do not exhibit any gross defects and have normal uterine morphology and fertility (25) (data not shown). TUNEL assay showed no significant difference in the number of apoptotic cells between wild-type (19.45 ± 4.70%) and Birc1a−/− (17.06 ± 3.25%) oil-treated uterine epithelia (n = 5; P = 0.25; compare Fig. 5A with 1A, Fig. 5G). After DES treatment however, a notable portion (0.88 ± 0.06%) of Birc1a−/− uterine epithelial cells were still TUNEL positive compared with zero in the wild type (n = 5, P <2−5) (Fig. 5, B and G). This demonstrates that approximately 5.2% (0.88/17.06 × 100%) of apoptotic uterine epithelial cells in Birc1a mutants have escaped DES-mediated suppression. Consistent with the TUNEL results, a number of active caspase-3 and -9-positive cells were also detected in DES-treated Birc1a−/− uterine epithelium but not in wild-type controls (compare Fig. 5, C–F, with Fig. 1). These results demonstrate that at least in some uterine epithelial cells, Birc1a is required for DES to inhibit apoptosis.

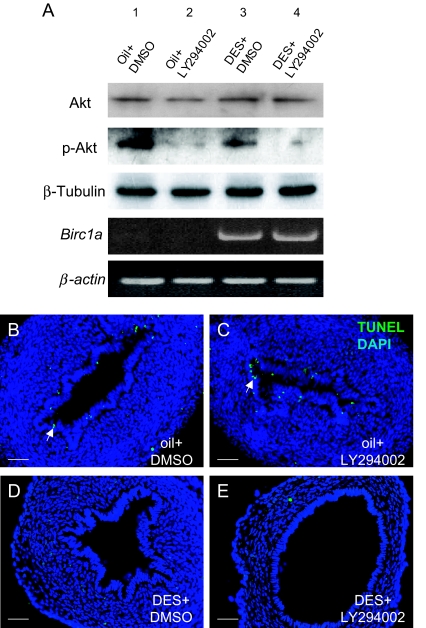

Estrogen is known to be able to induce phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activity, an event leading to the phosphorylation of Akt (42). One study showed that in primary neuronal culture, Akt phosphorylation can induce Birc1a expression (43). As a first step toward studying the regulation of Birc1a by estrogen, we investigated whether this signaling pathway is also involved in Birc1a regulation in the uterine epithelium. Because our data showed that DES can also effectively inhibit apoptosis in CD-1 neonatal uteri (32) and that this strain was used to establish the neonatal DES model (37), we used CD-1 mice in this experiment. RT-PCR analysis showed that the same Birc1 genes were induced by DES treatment in CD-1 neonatal uterus (data not shown). CD-1 pups were treated with a PI3K inhibitor, LY-294002, before oil or DES injection on P4 and P5 (n = 3). Western blotting with an antibody specific for phosphorylated Akt showed that a substantial amount of phospho-Akt was detected even in oil-treated controls, where Birc1a was not expressed. We did not observe an increase in phospho-Akt level consistently upon DES treatment possibly because the regulation of the Akt pathway by DES or estrogen is different in neonatal uterus. Treatment with LY-294002 together with DES effectively blocked PI3K, as reflected by a decrease in Akt phosphorylation level (Fig. 6A). However, treatment with this drug had no discernible effect on Birc1a induction by DES (Fig. 6A). Likewise, no effect on apoptotic suppression by DES was observed when LY-294002 was coadministered (Fig. 6, B–E). These results do not support an involvement of the PI3K-Akt pathway in Birc1a regulation by DES in our system.

Figure 6.

Up-Regulation of Birc1a by DES Was Not Associated with Akt Phosphorylation

A, Western blot analysis of Akt, phospho-Akt, and β-tubulin after oil or DES injection, with or without PI3K inhibitor LY-294002 treatment. Even without DES, there was a substantial amount of phosphorylated Akt (lane 1). Coinjection of DES with LY-294002 resulted in a reduction in the phospho-Akt level, but not the total Akt level (lane 4). RT-PCR showed that changes in the phospho-Akt level did not affect Birc1a transcript level with or without DES treatment. B–E, TUNEL staining showed that coinjection of LY-294002 with DES did not rescue the suppressive effect on uterine epithelial apoptosis. Arrows indicate apoptotic cells. Bars, 50 μm (B–E).

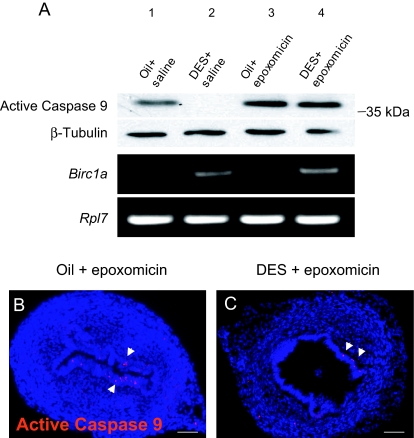

Estrogen Depletes Active Caspase-9 through Proteasome Degradation

Some biochemical and structural studies indicate that only XIAP can directly inhibit the enzyme activities of caspases, whereas other IAPs might exert their antiapoptotic functions by targeting active caspases to ubiquitin-proteasome degradation (20,44,45). To test whether Birc1 inhibits apoptosis by subjecting active caspases to proteasome degradation, we blocked proteasome function by coadministering a proteasome inhibitor, epoxomicin, along with oil or DES. Uterine epithelial tissues were isolated, and proteins were extracted and subjected to Western blotting to examine the level of active caspase-9. As shown in Fig. 7A, we detected a band just above the 35-kDa marker in oil controls, corresponding to active caspase-9 (39 kDa). Coinjection of epoxomicin and oil slightly elevated the active caspase-9 level compared with oil alone (Fig. 7A, lanes 1 and 3). DES treatment completely eliminated active caspase-9, a result that is consistent with the immunofluorescence result (Fig. 7A, lane 2, and Fig. 1E), whereas cotreatment with epoxomicin and DES restored active caspase-9 (Fig. 7A, lane 4; n = 3 in each treatment group). Coadministration of epoxomicin did not affect the induction of Birc1a by DES (Fig. 7A). Immunostaining for active caspase-9 confirmed the Western blot result and localized the restored active caspase-9 in the uterine epithelium (Fig. 7, B and C, arrows). These results support the hypothesis that Birc1 proteins inhibit apoptosis by subjecting active caspases to proteasome degradation.

Figure 7.

Blockage of Proteasome Activity Led to Restoration of Active Caspase-9

A, Western blot showed that at P5, DES treatment resulted in the depletion of active caspase-9 (lane 2) compared with oil-treated control (lane 1). Coadministration of epoxomicin with DES restored its level (lane 4) but did not affect the regulation of Birc1a expression by DES. B and C, Immunofluorescence detected active caspase-9-positive cells (arrows) in the uterine epithelium treated with epoxomicin together with either oil or DES. n = 3. Bars, 50 μm (B and C).

Ovarian Hormones Regulate Birc1 Genes in Adult Uterus

Ovarian hormones, i.e., estrogen and progesterone, can inhibit apoptosis in the luminal epithelium, which is important for implantation (33). To determine whether expression of Birc1s is regulated by ovarian hormones in the adult uterus, we examined their expression in ovariectomized mice after hormone treatments. Eight-week-old ovariectomized mice were treated with a single injection of oil, E2 (250 ng/mouse), progesterone (1 mg/mouse), or E2 plus progesterone, and uteri were harvested 8 h later for RNA extraction and immunofluorescence (n = 3). This time point was chosen to determine whether induction of Birc1 expression precedes suppression of apoptosis by ovarian hormones, which was obvious at 24 h after treatment (33). Total Birc1 proteins were up-regulated by E2, progesterone, or E2 plus progesterone treatment in both luminal and glandular epithelium as assayed by immunofluorescence (supplemental Fig. S4, A–D). Real-time RT-PCR confirmed this result and revealed that Birc1a, -1b, and -1e were all positively regulated by the two hormones (supplemental Fig. S4E). It is noteworthy that Birc1b is synergistically activated by the two hormones, suggesting a possible function during implantation (supplemental Fig. S4E). We also examined Birc1 expression during the estrous cycle and found that their expression fluctuates with lower expression in the diestrous phase and higher expression during the rest of the estrous cycle (supplemental Fig. S5). These results indicate that endogenous ovarian hormones can similarly regulate Birc1 expression in adult uterus, suggesting a functional role of Birc1s in adult uterine biology.

DISCUSSION

Estrogen is known to have antiapoptotic effects on a variety of cell types, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, osteoblasts, and uterine epithelial cells (28,46,47,48). However, the underlying antiapoptotic mechanisms conferred by estrogen can be very tissue specific. In the ischemia/reperfusion cardiac model, stress induces reactive oxygen species that triggers cytochrome c release (49). Pretreatment of estrogen induces the expression of the mitochondrial respiratory complex, which prevents cytochrome c release from the mitochondria (50). Estrogen inhibits apoptosis in osteoblasts but has the opposite effect on osteoclasts, which has been attributed to duration of ERK phosphorylation (48). In the cervical epithelium, Wang et al. (36) showed that normal apoptosis is mediated through P2X7 receptor and a Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial pathway. They also showed that this effect was dependent on de novo transcription and protein synthesis. However, the target proteins induced by estrogen were not identified. In addition, the majority of these studies used cell lines as a model system, for which the in vivo relevance is questionable.

Here we present molecular and genetic evidence that Birc1 genes represent a subset of estrogen-induced targets that are directly involved in apoptotic repression. First, Birc1 genes were potently induced by neonatal treatment of E2 or DES through ER-α in the uterine epithelium, where apoptotic cells were mainly detected. Given the natural function of these proteins, their induction by estrogen makes them good candidates for a role in the observed apoptosis inhibition. Second, the induction of Birc1 genes precedes estrogen’s effect on apoptosis. This is an important observation that supports a causal rather than secondary role for the various Birc1s in apoptosis inhibition. Finally, the most compelling evidence for our model comes from the genetic study in which neonatal estrogen or DES treatment failed to completely inhibit apoptosis in Birc1a knockout uterine epithelium. This result clearly demonstrates that in a fraction of uterine epithelial cells, Birc1a is required for cellular survival after estrogen exposure. Intriguingly, only a small fraction of cells escaped apoptosis suppression. A possible explanation for this is that there is an IAP protein threshold level required to inhibit apoptosis, which varies among uterine epithelial cells. The loss of Birc1a thus lowers the total IAP protein level below a threshold that is required in some uterine epithelial cells for survival. On the other hand, cells that have a lower threshold for IAP proteins will still be protected from apoptosis due to functional redundancy from other IAP proteins, such as other Birc1s. Even though our data do not exclude the involvement of other antiapoptotic proteins, it is clear that Birc1a and possibly other Birc1s play active roles in mediating estrogen-induced apoptosis suppression.

At present, it is unclear how Birc1 proteins inhibit apoptosis in vivo. A number of studies have shown that BIRC1 can inhibit caspase-3, -7, and -9 activities by direct binding through BIR domains (26,27). However, recent biochemical and structural studies argue against this hypothesis and propose BIRC4 (XIAP) as the sole IAP to directly inhibit caspase activities (20). Moreover, characterization of mice lacking functional Birc6 revealed that Birc6 can function upstream of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway by regulating both the expression and nuclear localization of p53 (51). In our study, inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome machinery resulted in an accumulation of active caspase-9 even when treated with DES. This result suggests that estrogen treatment does not inhibit the activation of caspase-9 but rather affects active caspase-9 stability, and Birc1 proteins are an integral part of this posttranslational regulation. In this scenario, Birc1s may function by subjecting active caspases to proteasome degradation and, as a result, inhibit uterine epithelial apoptosis. Because Birc1 proteins do not have the RING zinc-finger domain, they must then interact with other proteins to ubiquitinate and degrade active caspases. Which E3 ligase Birc1s interact with in the uterine epithelium remains to be determined.

Our data also showed that the up-regulation of Birc1 genes by estrogen was unlikely to be mediated by Akt phosphorylation, because attenuation of Akt phosphorylation had little effect on Birc1a expression. On the other hand, ER-α is required to induce Birc1 expression, suggesting that ER may directly regulate their expression by binding to estrogen-response elements in the Birc1 promoters. A sequence analysis on the mouse Birc1a promoter did reveal two putative estrogen-response elements, but their functional significance is not clear at present.

DES, a synthetic estrogen, causes abnormal reproductive tract development (37,52). Prescribed to pregnant women for three decades in the last century, it has caused tremendous suffering in the next generation exposed to it in utero. In the mouse DES model, DES alters uterine epithelial cell fate, inhibits uterine epithelial apoptosis, and induces uterine adenocarcinoma formation in 90% of mice by 18 months (32,53). The molecular mechanism underlying uterine carcinogenesis is unclear; however, mutations in tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN may contribute to the development of uterine cancer (54). One speculation is that by inhibiting apoptosis, DES can prolong the lives of damaged uterine epithelial stem cells that should undergo apoptosis if they are unable to correct the majority of these mutations. However, with the help of DES, these uterine stem cells may persist, proliferate, and ultimately lead to the development of uterine adenocarcinoma. In conclusion, we demonstrate for the first time that Birc1 proteins are functional targets of estrogen and play an important role in apoptosis suppression in the mouse developing uterine epithelium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice Maintenance and Surgical Procedure

All mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility at Washington University and handled according to National Institutes of Health guidelines. Birc1a−/− mice were generated by gene targeting as described previously and were maintained on C57BL/6J genetic background (25). Esr1+/− mice on C57BL/6J background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). CD-1 and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA), and the Jackson Laboratory, respectively. Ovariectomy was performed on 8-wk-old females under general anesthesia following a routine protocol (55), and mice were allowed to rest for 2 wk before steroid treatments.

Steroids and Drug Treatments

DES (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in ethanol at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and further diluted 100-fold in corn oil. E2 (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in corn oil to final concentrations of 250 ng, 2.5 μg, 10 μg, and 1 mg/ml for different dosage regimens. Neonatal pups were injected daily at 1000 h with 20 μl corn oil, E2, or DES sc from P1–P5, and uteri were harvested at 1600 h on P5. E2 and progesterone (Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in sesame oil to a final concentration of 2.5 μg/ml and 10 mg/ml, respectively, and injected sc into ovariectomized females alone or in combination (100 μl/mouse), where control mice received 100 μl sesame oil. For PI3K inhibitory experiments, LY-294002 (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide to a final concentration of 20 mg/ml. Neonatal pups undergoing daily oil or DES injection received ip injection of LY-294002 (20 μl/pup) 15 min before oil or DES injection on P4 and P5. Control animals received an equal volume of dimethylsulfoxide. For proteasome inhibition experiments, neonates were treated daily with oil or DES from P1–P5 and received a single injection of 20 μl of either saline or 100 μm epoxomicin solution in saline (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) ip at 1800 h on P4. Uterine tissues were harvested at 1600 h on P5.

TUNEL Assay and Uterine Epithelial Apoptotic Rate Analysis

TUNEL assay was performed on paraformaldehyde-fixed 10-μm paraffin sections using the In Situ Cell Death Kit (Roche Diagnostic Corp., Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both TUNEL-positive and the total cell numbers in the uterine epithelium were scored on 10 transverse sections of an individual uterus. The apoptotic rate for each section was calculated by dividing the number of TUNEL-positive cells by the total number of luminal epithelial cells. The apoptotic rate for an experimental group is an average of those derived from all examined uterine sections. All experimental groups consisted of at least three individual animals.

Immunofluorescence and Double Labeling with TUNEL

Immunofluorescence was performed following procedures as described previously (56). The dilutions used for the primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies were as follows: anti-cleaved caspase-9, 1:200 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); anti-active caspase-3, 1:50 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and anti-NAIP, 1:100 (Chemicon). Alexa Fluor dye-labeled secondary goat antirabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was diluted 1:2000. Slides were counterstained with 2 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Sigma-Aldrich), mounted with antifading mounting solution (5% N-propyl gallate; 70% glycerol; and 25% 0.5 m Tris, pH 9.0), and examined under a Zeiss Axioskop 2 fluorescent microscope. Double labeling with TUNEL was performed as described above, except that after secondary antibody incubation, an additional step of incubation with the enzyme mix from the TUNEL kit was performed at 37 C for 1 h.

RT-PCR and Real-Time RT-PCR

Uterine tissues were removed and briefly rinsed in cold PBS. Total RNA was extracted by using RNA STAT-60 reagent (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, TX) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated using SuperScriptII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Primers used for PCRs were designed using Primer3 online software (57) and are listed in supplemental Table S1. PCR was performed by using an MJ Research PTC-200 Peltier Thermal Cycler; products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. PCR products were subsequently purified and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and their sequences were verified. Real-time RT-PCR was performed in a 20-μl reaction volume containing FastStart SYBR Green Master mix (Roche), using 7300 Real-Time PCR systems (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR were performed as follows: 2 min at 95 C and 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95 C, 30 sec at 60 C, and 30 sec at 72 C. All PCR products were sequence verified. To ensure the specificity of PCR amplification from cDNAs, negative controls including reactions with no templates or no primers and using RNA as templates were performed. Real-time PCR results were analyzed by ABI PRISM 7000 (Applied Biosystems) and Microsoft Excel as previously described (56).

In Situ Hybridizations

In situ hybridizations were performed on paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded 10-μm sections as described previously (58). The Birc1a 3′-untranslated region PCR fragment of was cloned into the pCR4 vector (Invitrogen), whereas those for Birc1b and Birc1e were cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega). These subclones were used to generate gene-specific 35S-labeled cRNA probes first by linearizing the plasmids with specific restriction endonucleases and followed by in vitro transcription using RNA polymerases outlined in supplemental Table S2.

Western Blotting

Uterine tissues were harvested, rinsed briefly in cold PBS, and snap frozen on dry ice. Isolation of uterine epithelium was as described previously (59). Proteins were extracted by homogenizing frozen tissues in RIPA buffer (1% Nonidet P-40; 0.25% Na-deoxycholate; 150 mm NaCl; 1 mm EDTA; and 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin), followed by brief centrifugation at 4 C. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assays (60). An equal amount of total protein from each sample was loaded and resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) after electrophoresis. The membranes were washed three times in PBST (0.1% Tween 20 and 1× PBS, pH 7.6) and blocked in 5% BSA in PBST overnight at 4 C with agitation. They were then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature. The dilutions used for each primary antibody were 1:500 for rabbit polyclonal anti-β-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), 1:1000 for rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase-9 (Cell Signaling), 1:1000 for rabbit polyclonal anti-Akt (Cell Signaling) and 1:1000 for mouse monoclonal anti-phospho-Akt (Cell Signaling). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antirabbit or antimouse secondary antibodies were diluted 5000-fold in blocking solution and incubated with corresponding blots. The blots were then washed and incubated in Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) and exposed to autoradiography films.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test, and results are expressed as means ± sem. The number of independent experiments is specified in the results and figure legends. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD41492 and ES014482 to L.M.

Disclosure Statement: Y.Y., W.-W.H., C.L., H.C., and L.M. have nothing to declare. A.M. holds a patent on NAIP as a neuroprotector.

First Published Online September 27, 2007

Abbreviations: BIR, Baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis repeat; DES, diethylstilbestrol; E2, 17β-estradiol; ER, estrogen receptor; IAP, inhibitor of apoptosis; NAIP, neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein; P1, postnatal d 1; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling.

References

- Jacobson MD, Weil M, Raff MC 1997 Programmed cell death in animal development. Cell 88:347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J 1998 Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell 94:491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeev EE, Schuchmann M, Luria V, Chiannilkulchai N, Beckmann JS, Mett IL, Rebrikov D, Brodianski VM, Kemper OC, Kollet O, Lapidot T, Soffer D, Sobe T, Avraham KB, Goncharov T, Holtmann H, Lonai P, Wallach D 1998 Targeted disruption of the mouse Caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity 9:267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldin MP, Goncharov TM, Goltsev YV, Wallach D 1996 Involvement of MACH, a novel MORT1/FADD-interacting protease, in Fas/APO-1- and TNF receptor-induced cell death. Cell 85:803–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Armstrong RC, Krebs J, Srinivasula SM, Wang L, Bullrich F, Fritz LC, Trapani JA, Tomaselli KJ, Litwack G, Alnemri ES 1996 In vitro activation of CPP32 and Mch3 by Mch4, a novel human apoptotic cysteine protease containing two FADD-like domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:7464–7469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A, Harris AW, Huang DC, Krammer PH, Cory S 1995 Bcl-2 and Fas/APO-1 regulate distinct pathways to lymphocyte apoptosis. EMBO J 14:6136–6147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X 1997 Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 91:479–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Henzel WJ, Liu X, Lutschg A, Wang X 1997 Apaf-1, a human protein homologous to C. elegans CED-4, participates in cytochrome c-dependent activation of caspase-3. Cell 90:405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Li Y, Liu X, Wang X 1999 An APAF-1.cytochrome c multimeric complex is a functional apoptosome that activates procaspase-9. J Biol Chem 274:11549–11556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh A, Srinivasula SM, Acharya S, Fishel R, Alnemri ES 1999 Cytochrome c and dATP-mediated oligomerization of Apaf-1 is a prerequisite for procaspase-9 activation. J Biol Chem 274:17941–17945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y 1998 Caspases: enemies within. Science 281:1312–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ 1999 BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev 13:1899–1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory S, Adams JM 2002 The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev Cancer 2:647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genini D, Budihardjo I, Plunkett W, Wang X, Carrera CJ, Cottam HB, Carson DA, Leoni LM 2000 Nucleotide requirements for the in vitro activation of the apoptosis protein-activating factor-1-mediated caspase pathway. J Biol Chem 275:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Kim HE, Shu H, Zhao Y, Zhang H, Kofron J, Donnelly J, Burns D, Ng SC, Rosenberg S, Wang X 2003 Distinctive roles of PHAP proteins and prothymosin-α in a death regulatory pathway. Science 299:223–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y 2004 Caspase activation, inhibition, and reactivation: a mechanistic view. Protein Sci 13:1979–1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias B, Ashhab Y, Ben-Yehuda D 2004 The inhibitor of apoptosis protein family (IAPs): an emerging therapeutic target in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 14:231–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook NE, Clem RJ, Miller LK 1993 An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J Virol 67:2168–2174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clem RJ, Robson M, Miller LK 1994 Influence of infection route on the infectivity of baculovirus mutants lacking the apoptosis-inhibiting gene p35 and the adjacent gene p94. J Virol 68:6759–6762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckelman BP, Salvesen GS, Scott FL 2006 Human inhibitor of apoptosis proteins: why XIAP is the black sheep of the family. EMBO Rep 7:988–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal L, McCall K, Agapite J, Hartwieg E, Steller H 2000 Induction of apoptosis by Drosophila reaper, hid and grim through inhibition of IAP function. EMBO J 19:589–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy N, Mahadevan MS, McLean M, Shutler G, Yaraghi Z, Farahani R, Baird S, Besner-Johnston A, Lefebvre C, Kang X, Salih M, Aubry H, Tamai K, Guan X, Ioannou P, Crawford TO, de Jong PJ, Surh L, Ikeda J-E, Korneluk RG, MacKenzie A 1995 The gene for neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein is partially deleted in individuals with spinal muscular atrophy. Cell 80:167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endrizzi MG, Hadinoto V, Growney JD, Miller W, Dietrich WF 2000 Genomic sequence analysis of the mouse Naip gene array. Genome Res 10:1095–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez E, Lee SH, Gauthier S, Yaraghi Z, Tremblay M, Vidal S, Gros P 2003 Birc1e is the gene within the Lgn1 locus associated with resistance to Legionella pneumophila. Nat Genet 33:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik M, Thompson CS, Yaraghi Z, Lefebvre CA, MacKenzie AE, Korneluk RG 2000 The hippocampal neurons of neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein 1 (NAIP1)-deleted mice display increased vulnerability to kainic acid-induced injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:2286–2290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier JK, Lahoua Z, Gendron NH, Fetni R, Johnston A, Davoodi J, Rasper D, Roy S, Slack RS, Nicholson DW, MacKenzie AE 2002 The neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein is a direct inhibitor of caspases 3 and 7. J Neurosci 22:2035–2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoodi J, Lin L, Kelly J, Liston P, MacKenzie AE 2004 Neuronal apoptosis-inhibitory protein does not interact with Smac and requires ATP to bind caspase-9. J Biol Chem 279:40622–40628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz S, Lynch MP, Galand P, Gerschenson LE 1987 Hormonal regulation of cell death in rabbit uterine epithelium. Am J Pathol 127:51–59 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo T, Terada N, Saji F, Tanizawa O 1993 Inhibitory effects of estrogen, progesterone, androgen and glucocorticoid on death of neonatal mouse uterine epithelial cells induced to proliferate by estrogen. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 46:25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rodriguez J, Martinez-Garcia C 1997 Apoptosis pattern elicited by oestradiol treatment of the seminiferous epithelium of the adult rat. J Reprod Fertil 110:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Newbold RR, Dixon D 1999 Effects of neonatal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure on morphology and growth patterns of endometrial epithelial cells in CD-1 mice. Toxicol Pathol 27:325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WW, Yin Y, Bi Q, Chiang TC, Garner N, Vuoristo J, McLachlan JA, Ma L 2005 Developmental diethylstilbestrol exposure alters genetic pathways of uterine cytodifferentiation. Mol Endocrinol 19:669–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Paria BC 2006 Importance of uterine cell death, renewal, and their hormonal regulation in hamsters that show progesterone-dependent implantation. Endocrinology 147:2215–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt SC, Deroo BJ, Hansen K, Collins J, Grissom S, Afshari CA, Korach KS 2003 Estrogen receptor-dependent genomic responses in the uterus mirror the biphasic physiological response to estrogen. Mol Endocrinol 17:2070–2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seval Y, Cakmak H, Kayisli UA, Arici A 2006 Estrogen-mediated regulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in human endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:2349–2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li X, Wang L, Feng YH, Zeng R, Gorodeski G 2004 Antiapoptotic effects of estrogen in normal and cancer human cervical epithelial cells. Endocrinology 145:5568–5579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, McLachlan JA 1982 Vaginal adenosis and adenocarcinoma in mice exposed prenatally or neonatally to diethylstilbestrol. Cancer Res 42:2003–2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg JG, Kalland T 1981 Neonatal estrogen treatment and epithelial abnormalities in the cervicovaginal epithelium of adult mice. Cancer Res 41:721–734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Korach KS 2004 Estrogen receptor-α mediates the detrimental effects of neonatal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in the murine reproductive tract. Toxicology 205:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Dixon D, Yates M, Moore AB, Ma L, Maas R, Korach KS 2001 Estrogen receptor-α knockout mice exhibit resistance to the developmental effects of neonatal diethylstilbestrol exposure on the female reproductive tract. Dev Biol 238:224–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins GS, Birch L, Couse JF, Choi I, Katzenellenbogen B, Korach KS 2001 Estrogen imprinting of the developing prostate gland is mediated through stromal estrogen receptor α: studies with αERKO and βERKO mice. Cancer Res 61:6089–6097 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisamoto K, Ohmichi M, Kurachi H, Hayakawa J, Kanda Y, Nishio Y, Adachi K, Tasaka K, Miyoshi E, Fujiwara N, Taniguchi N, Murata Y 2001 Estrogen induces the Akt-dependent activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 276:3459–3467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Gabriel C, Nelson DA, White E, Mackenzie ET, Vivien D, Buisson A 2005 Akt-dependent expression of NAIP-1 protects neurons against amyloid-β toxicity. J Biol Chem 280:24941–24947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC 1997 X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature 388:300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Cai M, Gunasekera AH, Meadows RP, Wang H, Chen J, Zhang H, Wu W, Xu N, Ng SC, Fesik SW 1999 NMR structure and mutagenesis of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein XIAP. Nature 401:818–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelzer T, Neumann M, de Jager T, Jazbutyte V, Neyses L 2001 Estrogen effects in the myocardium: inhibition of NF-κB DNA binding by estrogen receptor-α and -β. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 286:1153–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyridopoulos I, Sullivan AB, Kearney M, Isner JM, Losordo DW 1997 Estrogen-receptor-mediated inhibition of human endothelial cell apoptosis. Estradiol as a survival factor. Circulation 95:1505–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JR, Plotkin LI, Aguirre JI, Han L, Jilka RL, Kousteni S, Bellido T, Manolagas SC 2005 Transient versus sustained phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation of ERKs underlie anti-versus pro-apoptotic effects of estrogens. J Biol Chem 280:4632–4638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK, Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER 2006 Estrogen prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis through inhibition of reactive oxygen species and differential regulation of p38 kinase isoforms. J Biol Chem 281:6760–6767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh YC, Yu HP, Suzuki T, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH 2006 Upregulation of mitochondrial respiratory complex IV by estrogen receptor-beta is critical for inhibiting mitochondrial apoptotic signaling and restoring cardiac functions following trauma-hemorrhage. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41:511–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Shi M, Liu R, Yang QH, Johnson T, Skarnes WC, Du C 2005 The Birc6 (Bruce) gene regulates p53 and the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis and is essential for mouse embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:565–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J 1971 Transplacental carcinogenesis by stilbestrol. N Engl J Med 285:404–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold RR, Bullock BC, McLachlan JA 1990 Uterine adenocarcinoma in mice following developmental treatment with estrogens: a model for hormonal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 50:7677–7681 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro H, Blazes MS, Wu R, Cho KR, Bose S, Wang SI, Li J, Parsons R, Ellenson LH 1997 Mutations in PTEN are frequent in endometrial carcinoma but rare in other common gynecological malignancies. Cancer Res 57:3935–3940 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B, Beddington R, Costantini F, Lacy E 1994 Manipulating the mouse embryo. 2nd ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Lin C, Ma L 2006 MSX2 promotes vaginal epithelial differentiation and Wolffian duct regression and dampens the vaginal response to diethylstilbestrol. Mol Endocrinol 20:1535–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky H 2000 Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132:365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawersik S, Epstein JA 2000 Gene expression analysis by in situ hybridization. Radioactive probes. Methods Mol Biol 137:87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigsby RM, Cooke PS, Cunha GR 1986 A simple efficient method for separating murine uterine epithelial and mesenchymal cells. Am J Physiol 251:E630–E636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM 1976 A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.