Abstract

The neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) forms a complex with p59fyn kinase and activates it via a mechanism that has remained unknown. We show that the NCAM140 isoform directly interacts with the intracellular domain of the receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase RPTPα, a known activator of p59fyn. Whereas this direct interaction is Ca2+ independent, formation of the complex is enhanced by Ca2+-dependent spectrin cytoskeleton–mediated cross-linking of NCAM and RPTPα in response to NCAM activation and is accompanied by redistribution of the complex to lipid rafts. Association between NCAM and p59fyn is lost in RPTPα-deficient brains and is disrupted by dominant-negative RPTPα mutants, demonstrating that RPTPα is a link between NCAM and p59fyn. NCAM-mediated p59fyn activation is abolished in RPTPα-deficient neurons, and disruption of the NCAM–p59fyn complex in RPTPα-deficient neurons or with dominant-negative RPTPα mutants blocks NCAM-dependent neurite outgrowth, implicating RPTPα as a major phosphatase involved in NCAM-mediated signaling.

Introduction

The neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) is involved in several morphogenetic events, such as neuronal migration and differentiation, neurite outgrowth, and axon fasciculation. NCAM-induced morphogenetic effects depend on activation of Src family tyrosine kinases and, in particular, p59fyn kinase (Schmid et al., 1999). NCAM-dependent neurite outgrowth is impaired in neurons from p59fyn-deficient mice (Beggs et al., 1994) and is abolished by inhibitors of Src kinase family members (Crossin and Krushel, 2000; Kolkova et al., 2000; Cavallaro et al., 2001). The NCAM140 isoform has been observed in a complex with p59fyn, whereas p59fyn does not associate significantly with NCAM180 or glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked NCAM120 (Beggs et al., 1997). However in oligodendrocytes, p59fyn is also associated with NCAM120 in isolated lipid rafts (Kramer et al., 1999), whereas in tumor cells NCAM is also associated with pp60c-src (Cavallaro et al., 2001), suggesting that additional molecular mechanisms may define NCAM's specificity of interactions with Src kinase family members. Several lines of evidence suggest that NCAM's association with lipid rafts is critical for p59fyn activation. NCAM not only colocalizes with p59fyn in lipid rafts (He and Meiri, 2002) but disruption of NCAM140 association with lipid rafts either by mutation of NCAM140 palmitoylation sites or by lipid raft destruction attenuates activation of the p59fyn kinase pathway, completely blocking neurite outgrowth (Niethammer et al., 2002). However, in spite of compelling evidence that NCAM can activate Src family tyrosine kinases, the mechanism of this activation has remained unclear.

The activity of Src family tyrosine kinases is regulated by phosphorylation (Brown and Cooper, 1996; Thomas and Brugge, 1997; Bhandari et al., 1998; Hubbard, 1999; Petrone and Sap, 2000). The two best-characterized tyrosine phosphorylation sites in Src family tyrosine kinases perform opposing regulatory functions. The site within the enzyme's activation loop (Tyr-420 in p59fyn) undergoes autophosphorylation, which is crucial for achieving full kinase activity. In contrast, phosphorylation of the COOH-terminal site (Tyr-531 in p59fyn) inhibits kinase activity through intramolecular interaction between phosphorylated Tyr-531 and the SH2 domain in p59fyn, which stabilizes a noncatalytic conformation.

A well known activator of Src family tyrosine kinases is the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase RPTPα (Zheng et al., 1992, 2000; den Hertog et al., 1993; Su et al., 1996; Ponniah et al., 1999). It contains two cytoplasmic catalytic domains, D1 and D2, of which only D1 is significantly active in vitro and in vivo (Wang and Pallen, 1991; den Hertog et al., 1993; Wu et al., 1997; Harder et al., 1998). To activate Src family tyrosine kinase, constitutively phosphorylated pTyr789 at the COOH-terminal of RPTPα binds the SH2 domain of Src family tyrosine kinase that disrupts the intra-molecular association between the SH2 and SH1 domains of the kinase. This initial binding is followed by binding between the inhibitory COOH-terminal phosphorylation site of the Src family tyrosine kinase (pTyr531 in p59fyn) and the D1 domain of RPTPα resulting in dephosphorylation of the inhibitory COOH-terminal phosphorylation sites in Src family tyrosine kinases (Zheng et al., 2000). These sites are hyperphosphorylated in cells lacking RPTPα, and kinase activity of pp60c-src and p59fyn in RPTPα-deficient mice is reduced (Ponniah et al., 1999). Like p59fyn and NCAM, RPTPα is particularly abundant in the brain (Kaplan et al., 1990; Krueger et al., 1990), accumulates in growth cones (Helmke et al., 1998), and is involved in neural cell migration and neurite outgrowth (Su et al., 1996; Yang et al., 2002; Petrone et al., 2003).

Remarkably, a close homologue of RPTPα, CD45, associates with the membrane-cytoskeleton linker protein spectrin (Lokeshwar and Bourguignon, 1992; Iida et al., 1994), a binding partner of NCAM (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). Following this lead, we investigated the possibility that RPTPα is involved in NCAM-induced p59fyn activation. We show that the intracellular domains of NCAM140 and RPTPα interact directly and that this interaction is enhanced by spectrin-mediated Ca2+-dependent cross-linking of NCAM and RPTPα. Levels of p59fyn associated with NCAM correlate with the ability of NCAM-associated RPTPα to bind to p59fyn, and the NCAM–p59fyn complex is disrupted in RPTPα-deficient brains implicating RPTPα as linker molecule between NCAM and p59fyn. RPTPα redistributes to lipid rafts in response to NCAM activation and RPTPα levels are reduced in lipid rafts from NCAM-deficient mice, suggesting that NCAM recruits RPTPα to lipid rafts to activate p59fyn. Finally, NCAM-mediated p59fyn activation is abolished in RPTPα-deficient neurons and NCAM-induced neurite outgrowth is blocked in RPTPα-deficient neurons or neurons transfected with dominant-negative RPTPα mutants, demonstrating that RPTPα is a major phosphatase involved in NCAM-mediated signaling.

Results

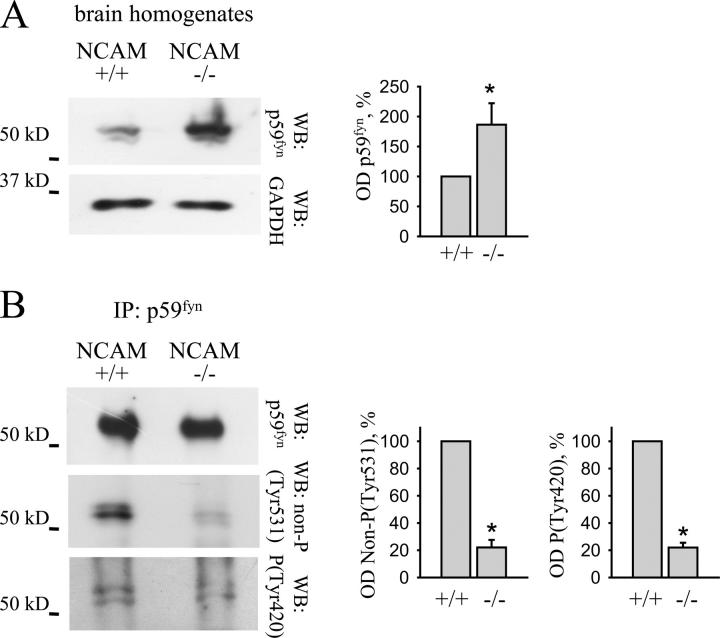

Activation of p59fyn is impaired in NCAM-deficient brains

Cross-linking of NCAM at the cell surface results in a rapid activation of p59fyn kinase (Beggs et al., 1997; Niethammer et al., 2002) via an unknown mechanism. To analyze whether or not NCAM deficiency may affect the activation status of p59fyn, we compared levels of activated p59fyn characterized by dephosphorylation at Tyr-531 and phosphorylation at Tyr-420 in the brains of wild-type and NCAM-deficient mice. Whereas the level of p59fyn protein was higher in brain homogenates of NCAM-deficient mice (Fig. 1 A), labeling with antibodies recognizing only p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531 or with antibodies recognizing only p59fyn phosphorylated at Tyr-420 was reduced in brain homogenates of NCAM-deficient mice (Fig. 1 B), indicating that activation of p59fyn is inhibited in NCAM-deficient brains and suggesting that NCAM is involved in the regulation of p59fyn function.

Figure 1.

Activated p59fyn is reduced in NCAM-deficient brain. (A) Brain homogenates from 0- to 4-d-old wild-type (NCAM+/+) and NCAM-deficient (NCAM−/−) mice were probed by Western blot with antibodies against total p59fyn protein. Labeling for GAPDH was included as loading control. Levels of p59fyn protein are increased in NCAM-deficient brains. (B) p59fyn immunoprecipitates from 0- to 4-d-old wild-type (NCAM+/+) and NCAM-deficient (NCAM−/−) mice were probed by Western blot with antibodies against total p59fyn protein, p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531, or p59fyn phosphorylated at Tyr-420. Activated p59fyn is reduced in NCAM-deficient brains. Histograms (A and B) show quantitation of the blots with OD for wild type set to 100%. Mean values ± SEM (n = 6) are shown. *, P < 0.05, paired t test.

NCAM forms a complex with RPTPα

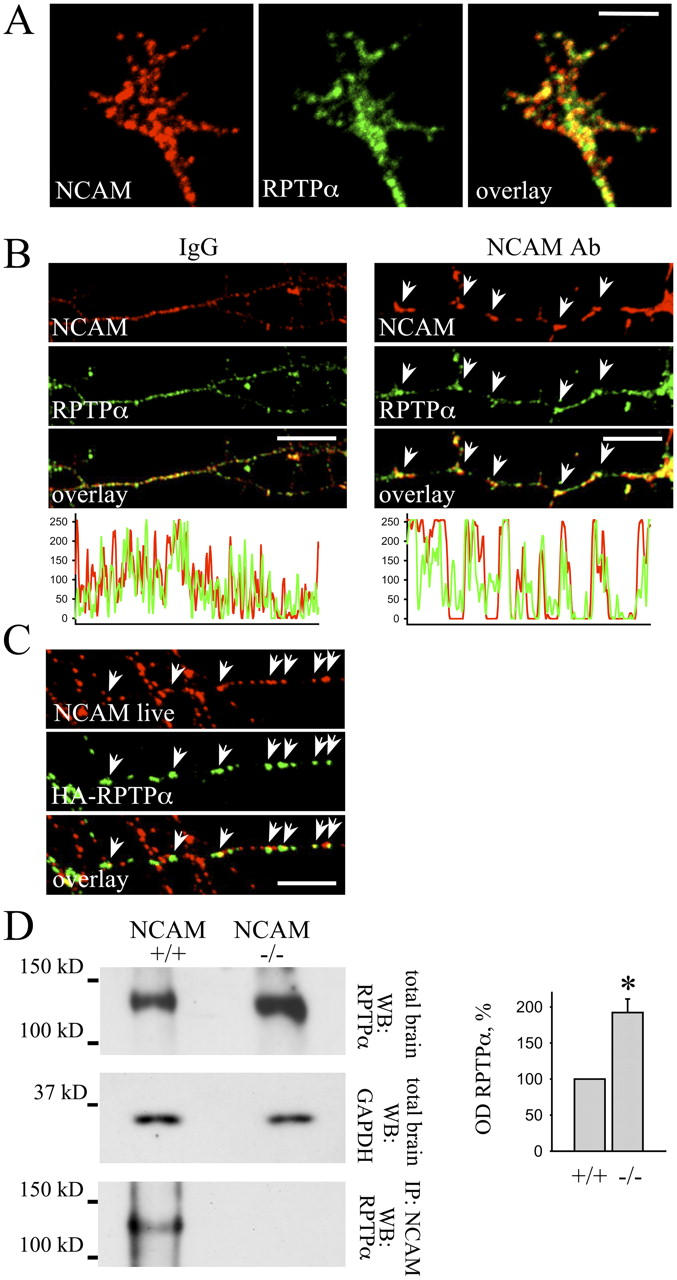

The intracellular domain of NCAM does not contain sequences known to induce p59fyn activation. Thus, NCAM may form a complex with a protein, possibly a protein tyrosine phosphatase, to activate p59fyn. One possible candidate is the RPTPα that dephosphorylates Tyr-531 of p59fyn (Bhandari et al., 1998) and is highly enriched in neurons and growth cones (Helmke et al.,1998). Remarkably, in RPTPα-deficient cells, both dephosphorylation of the COOH-terminal tyrosine residue and autophosphorylation of the tyrosine residue within the activation loop of pp60c-src is reduced (von Wichert et al., 2003), resembling the phenotype of NCAM-deficient mice. Furthermore, a close homologue of RPTPα, CD45, associates with the membrane-cytoskeleton linker protein spectrin (Lokeshwar and Bourguignon, 1992; Iida et al., 1994), a binding partner of NCAM (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). To investigate if NCAM interacts with RPTPα, we analyzed the distribution of both proteins in cultured hippocampal neurons. NCAM and RPTPα partially colocalized along neurites, and both proteins accumulated in growth cones where clusters of NCAM partially overlapped with accumulations of RPTPα (Fig. 2 A). To verify whether or not NCAM interacts with RPTPα, we induced clustering of NCAM at the cell surface of live hippocampal neurons by incubation with antibodies against NCAM. Clustering of NCAM enhanced overlap between NCAM and RPTPα localization (mean correlation between NCAM and RPTPα localization being 0.3 ± 0.05 and 0.6 ± 0.03 in neurons treated with nonspecific IgG or NCAM antibodies, respectively; Fig. 2 B), indicating that RPTPα partially redistributed to NCAM clusters and suggesting that NCAM and RPTPα form a complex. Because antibodies against RPTPα were directed against its intracellular domain, RPTPα contained in intracellular organelles could have been recognized as colocalizing with NCAM that associates with intracellular organelles of trans-Golgi network origin (Sytnyk et al., 2002). Thus, the redistribution of RPTPα to NCAM clusters may represent redistribution of intracellular carriers containing RPTPα. To analyze whether or not NCAM associates with RPTPα in the plasma membrane, we transfected neurons with RPTPα containing the HA tag in the extracellular domain and induced clustering of NCAM and HA-RPTPα with antibodies against NCAM and the HA tag. HA-RPTPα partially redistributed to NCAM clusters (Fig. 2 C), indicating that both proteins form a complex at the cell surface.

Figure 2.

NCAM forms a complex with RPTPα. (A) High magnification image of a growth cone of a hippocampal neuron labeled with antibodies against NCAM and RPTPα. Note that clusters of NCAM overlap with accumulations of RPTPα. (B) Live hippocampal neurons were treated with nonspecific IgG or with antibodies against NCAM. Note that antibodies against NCAM induced clustering of NCAM at the cell surface. Labeling with antibodies against RPTPα showed that RPTPα partially redistributed to NCAM clusters (arrows). The corresponding profiles show NCAM and RPTPα labeling intensities along neurites. Note increased overlap of NCAM and RPTPα clusters in neurons treated with NCAM antibodies. (C) Hippocampal neurons transfected with wild-type RPTPα containing an HA tag extracellularly were incubated live with antibodies against the HA tag and NCAM. Cell surface RPTPα partially redistributed to NCAM clusters (arrows). Bars, 10 μm. (D) Brain homogenates of wild-type (NCAM+/+) and NCAM-deficient (NCAM−/−) mice (total brain) and NCAM immunoprecipitates (IP: NCAM) were probed with antibodies against RPTPα by Western blot. Labeling for GAPDH was included as loading control. RPTPα coimmunoprecipitates with NCAM. Note increased expression of RPTPα in NCAM-deficient brains. Histogram shows quantitation of the RPTPα level in wild type (+/+) and NCAM-deficient (−/−) brains. OD for wild type was set to 100%. Mean values ± SEM (n = 6) are shown. *, P < 0.05, paired t test.

Finally, we examined the association between NCAM and RPTPα in the brain by coimmunoprecipitation. RPTPα coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM from brain homogenates (Fig. 2 D), confirming that NCAM associates with RPTPα. Interestingly, we found that the level of RPTPα was approximately two times higher in the brain of NCAM-deficient mice when compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 2 D), indicating a functional relationship between NCAM and RPTPα.

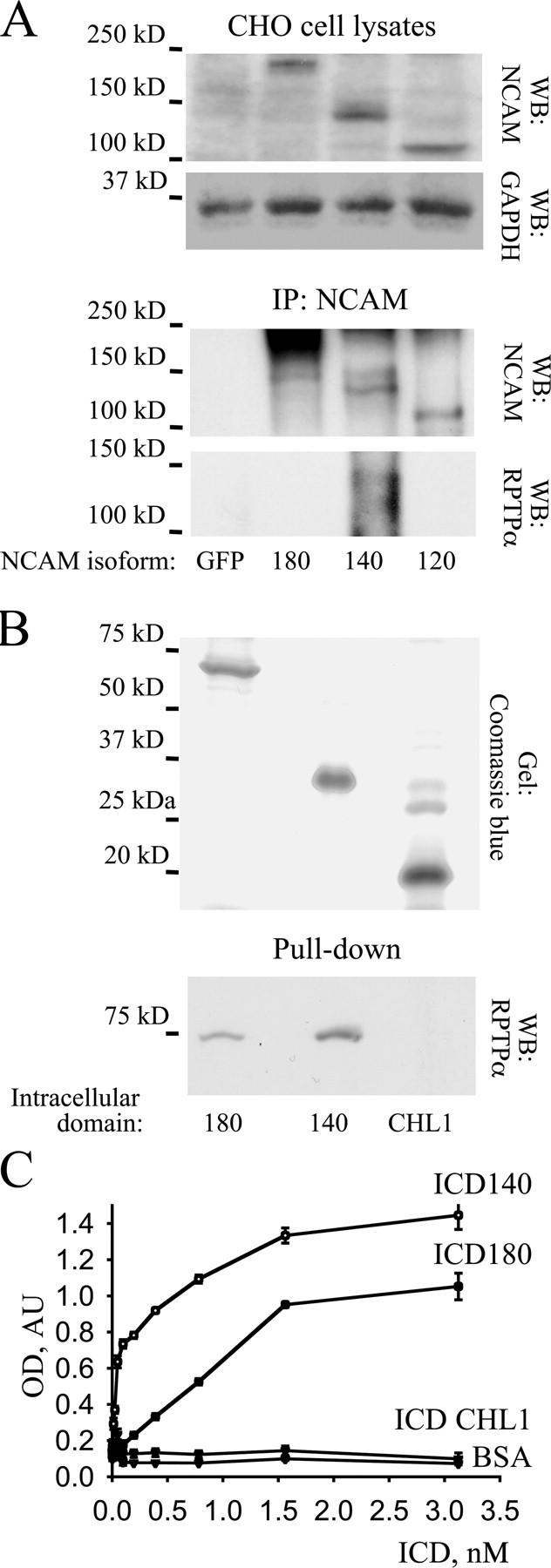

NCAM140 is the most potent RPTPα-binding NCAM isoform

To identify the NCAM isoform interacting with RPTPα, we expressed NCAM120, NCAM140, and NCAM180 in CHO cells and analyzed their association with RPTPα by coimmunoprecipitation. CHO cells endogenously express RPTPα that was detected with RPTPα antibodies as a band with a molecular mass identical to RPTPα detected in brain homogenates (unpublished data). Although transfected CHO cells expressed NCAM120, NCAM140, and NCAM180 in similar amounts, RPTPα coimmunoprecipitated only with NCAM140 (Fig. 3 A). However, after prolonged exposure of the film we could also detect RPTPα in NCAM180 immunoprecipitates (unpublished data). RPTPα did not coimmunoprecipitate with NCAM120. We conclude that RPTPα associates predominantly with NCAM140 and to a lesser extent with NCAM180.

Figure 3.

Intracellular domain of NCAM140 directly interacts with the intracellular domain of RPTPα. (A) Lysates and NCAM immunoprecipitates (IP: NCAM) from CHO cells transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, NCAM180, or GFP were probed by Western blot with antibodies against NCAM and RPTPα. Note that NCAM isoforms were expressed in approximately equal amounts whereas RPTPα immunoprecipitated only with NCAM140 but not NCAM180 or NCAM120. Labeling for GAPDH was included as loading control. (B) Intracellular domains of NCAM140, NCAM180, or CHL1 were bound to Ni-NTA agarose beads. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue and shows that approximately equal amounts of the intracellular domains of NCAM140, NCAM180, or CHL1 were bound to beads. Beads were incubated with equal concentrations of intracellular domains of RPTPα and the extent of RPTPα intracellular domain binding was determined by Western blotting using polyclonal antibodies against RPTPα. Intracellular domains of RPTPα interacted with intracellular domains of NCAM140, and to a lesser extent NCAM180, but not with intracellular domains of CHL1. (C) Intracellular domains of NCAM140, NCAM180, or CHL1 were bound to plastic and assayed by ELISA for the ability to bind increasing concentrations of RPTPα intracellular domains. Binding to BSA served as a control. Mean values (OD 405) ± SEM (n = 6) are shown. Intracellular domains of RPTPα bound to intracellular domains of NCAM140 and with a lower affinity to intracellular domains of NCAM180, but not to intracellular domains of CHL1.

Inability of NCAM120, the GPI-linked NCAM isoform without the intracellular domain, to bind RPTPα suggested that the intracellular domain of NCAM is involved in the formation of a complex between NCAM and RPTPα. Furthermore, the extracellular domain of NCAM (NCAM-Fc) did not bind to RPTPα in brain lysates, confirming that the extracellular domain of NCAM does not bind to RPTPα (unpublished data). To verify that the NCAM intracellular domain interacts directly with the intracellular domain of RPTPα, we analyzed binding of the recombinant intracellular domain of RPTPα to the intracellular domain of NCAM180 or NCAM140 in a pull-down assay. For comparison, the intracellular domain of CHL1, another adhesion molecule of the immunoglobulin superfamily, was used. The intracellular domain of RPTPα bound to the intracellular domain of NCAM180 or NCAM140 but not to the intracellular domain of CHL1 (Fig. 3 B). Interaction between the intracellular domains of RPTPα and NCAM140 was severalfold stronger than between the intracellular domains of RPTPα and NCAM180 (Fig. 3 B). To confirm this finding, we examined the direct interaction between the intracellular domains of RPTPα and NCAM180 or NCAM140 by ELISA. Intracellular domain of RPTPα bound to the intracellular domains of NCAM180 or NCAM140 in a concentration-dependent manner, with the intracellular domain of NCAM140 binding with a higher affinity than the intracellular domain of NCAM180 (Fig. 3 C). No binding with the intracellular domain of CHL1 was observed (Fig. 3 C). We conclude that NCAM binds directly to RPTPα via the intracellular domain, with NCAM140 being the most potent RPTPα-binding NCAM isoform.

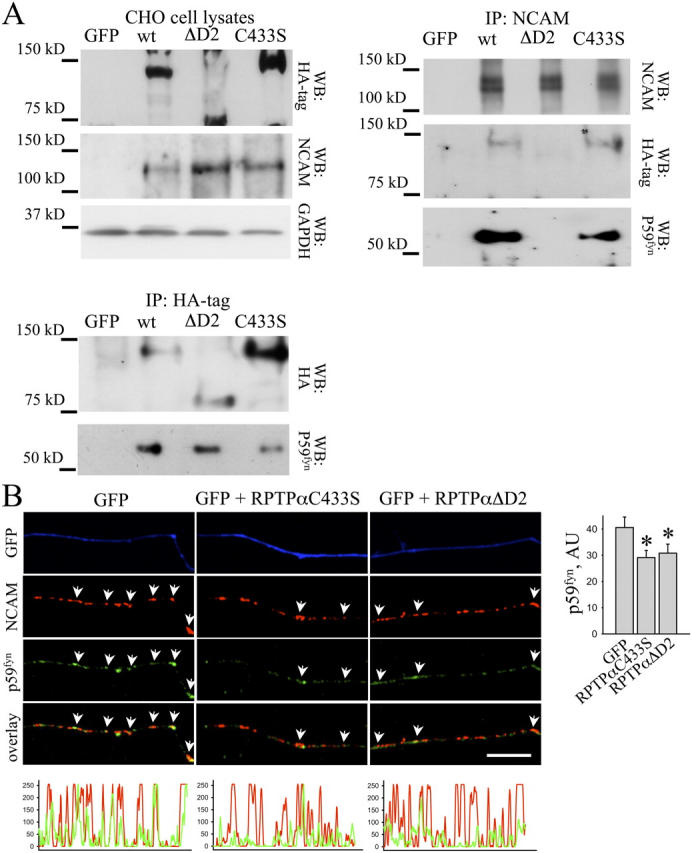

RPTPα binds NCAM140 via the D2 domain and links NCAM140 to p59fyn

To identify the part of the intracellular domain of RPTPα responsible for the interaction with NCAM140, we coexpressed, in CHO cells, NCAM140 together with the wild-type form of RPTPα (wtRPTPα), RPTPα lacking the D2 domain (RPTPαΔD2), or catalytically inactive form of RPTPα containing a mutation within the D1 catalytic domain (RPTPαC433S) and analyzed binding of NCAM140 to these RPTPα mutants by coimmunoprecipitation. All transfected RPTPα constructs contained the HA tag to distinguish them from endogenous RPTPα. As seen for endogenous RPTPα, transfected wtRPTPα coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140 (Fig. 4 A). Similar amounts of RPTPαC433S coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140, whereas RPTPαΔD2 did not coimmunoprecipitate (Fig. 4 A), indicating that the D2 domain is required for the interaction between RPTPα and NCAM140.

Figure 4.

RPTPα interacts with NCAM140 via D2 domain and links NCAM140 to p59fyn. (A) Lysates from CHO cells cotransfected with NCAM140 and wild-type (wt) RPTPα, RPTPαΔD2, RPTPαC433S, or GFP were probed with antibodies against HA tag and NCAM by Western blot. NCAM140 and RPTPα constructs are expressed at approximately equal amounts in transfected CHO cells. Labeling for GAPDH was included as loading control. NCAM (IP: NCAM) or RPTPα (IP: HA) immunoprecipitates were probed with antibodies against HA tag and p59fyn. wtRPTPα and RPTPαC433S but not RPTPαΔD2 coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140. RPTPαC433S and RPTPαΔD2 inhibited coimmunoprecipitation of p59fyn with NCAM140. p59fyn coimmunoprecipitated with wtRPTPα and RPTPαΔD2 but to a lower extent with RPTPαC433S. (B) Hippocampal neurons transfected with RPTPαC433S, RPTPαΔD2, or GFP were incubated live with NCAM antibodies to cluster NCAM and fixed and labeled with antibodies against p59fyn. Note that redistribution of p59fyn to NCAM clusters (arrows) was reduced in neurons transfected with RPTPαC433S or RPTPαΔD2. Bar, 10 μm. The corresponding profiles show NCAM and p59fyn labeling intensities along transfected neurites. The histogram shows mean labeling intensity of p59fyn in NCAM clusters. Transfection with RPTPαC433S or RPTPαΔD2 reduced association between p59fyn and NCAM. Mean values ± SEM (n > 20 neurons) are shown in arbitrary units (AU). *, P < 0.05, t test.

Remarkably, among the major NCAM isoforms, only NCAM140 forms a complex with p59fyn (Beggs et al., 1997) that we found to correlate with its ability to bind RPTPα (see the previous section). RPTPα directly interacts with p59fyn (Bhandari et al., 1998). Accordingly, p59fyn coimmunoprecipitated with wtRPTPα from transfected CHO cells (Fig. 4 A). Approximately the same amount of p59fyn coimmunoprecipitated with RPTPαΔD2 (Fig. 4 A), indicating that this truncated construct also binds p59fyn probably via the D1 domain. In accordance with previous reports, p59fyn showed reduced ability to bind RPTPαC433S, a catalytically inactive mutant of RPTPα (Fig. 4 A; Zheng et al., 2000).

To analyze the role of RPTPα in NCAM140–p59fyn complex formation, we coimmunoprecipitated p59fyn with NCAM140 in the presence of RPTPα mutants. In CHO cells cotransfected with NCAM140 and wtRPTPα, p59fyn coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140 (Fig. 4 A). The amount of p59fyn coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140 was reduced in cells cotransfected with RPTPαC433S (Fig. 4 A), correlating with the reduced ability of this catalytically inactive RPTPα mutant to bind p59fyn (see previous paragraph; Zheng et al., 2000). When NCAM140 was cotransfected with RPTPαΔD2, p59fyn no longer coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140 (Fig. 4 A). Because RPTPαΔD2 binds p59fyn (Fig. 4 A), it is conceivable that this mutant, which does not bind NCAM140, competes with endogenous RPTPα for binding to p59fyn and thus inhibits NCAM140–p59fyn complex formation.

To extend this analysis to neurons, we transfected hippocampal neurons with GFP alone or cotransfected with GFP and RPTPαΔD2 or RPTPαC433S and analyzed the redistribution of p59fyn to NCAM clusters after cross-linking NCAM with NCAM antibodies (Fig. 4 B). In neurons transfected with RPTPαΔD2 or RPTPαC433S, the level of p59fyn in NCAM clusters was reduced by ∼30% when compared with GFP only transfected cells, suggesting that RPTPαΔD2 or RPTPαC433S inhibit NCAM–p59fyn complex formation by competing with endogenous RPTPα. The combined observations indicate that NCAM140–p59fyn complex formation correlates with the ability of NCAM140-associated RPTPα to bind to p59fyn, implicating RPTPα as a linker between NCAM140 and p59fyn.

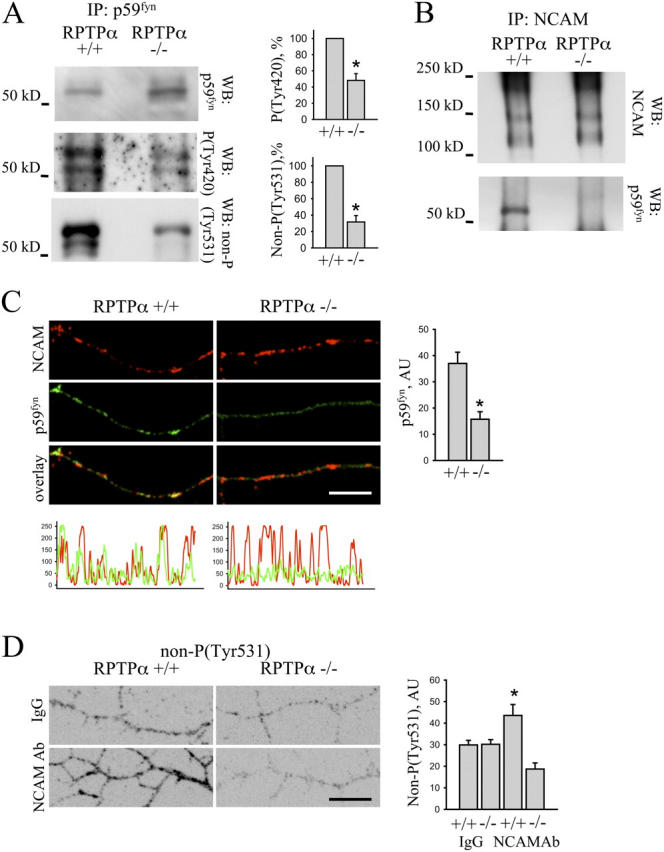

Association between NCAM and p59fyn and NCAM-mediated p59fyn activation are abolished in RPTPα-deficient neurons

To substantiate further our finding that RPTPα is a linker protein between NCAM and p59fyn, we analyzed p59fyn activation and association of p59fyn with NCAM in RPTPα-deficient brains. As for NCAM-deficient brains, levels of p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531 and levels of p59fyn phosphorylated at Tyr-420 were reduced in brain homogenates of RPTPα-deficient mice (Fig. 5 A), further suggesting that RPTPα plays a role in NCAM-mediated p59fyn activation in the brain. To analyze the role of RPTPα in the formation of the complex between NCAM and p59fyn, we immunoprecipitated NCAM from wild-type and RPTPα-deficient brains and probed immunoprecipitates with antibodies against p59fyn. Whereas p59fyn coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM from wild-type brains, p59fyn did not coimmunoprecipitate with NCAM from RPTPα-deficient brains (Fig. 5 B). Furthermore, when NCAM was clustered at the surface of wild-type and RPTPα-deficient cultured hippocampal neurons, levels of p59fyn were significantly reduced in NCAM clusters in RPTPα-deficient neurons when compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 5 C), indicating that RPTPα is required for complex formation between NCAM and p59fyn.

Figure 5.

NCAM–p59fyn complex formation and NCAM-mediated p59fyn activation are abolished in RPTPα-deficient neurons. (A) p59fyn immunoprecipitates from 4-d-old wild-type (RPTPα+/+) and RPTPα-deficient (RPTPα−/−) brain homogenates were probed by Western blot with antibodies against total p59fyn protein, p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531, or p59fyn phosphorylated at Tyr-420. Levels of p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531 and p59fyn phosphorylated at Tyr-420 are reduced in RPTPα-deficient brains. Histograms show quantitation of the blots with OD for wild type set to 100%. Mean values ± SEM (n = 6) are shown. *, P < 0.05, paired t test. (B) NCAM immunoprecipitates (IP: NCAM) from wild-type (RPTPα+/+) and RPTPα-deficient (RPTPα−/−) brain homogenates were probed with antibodies against NCAM and p59fyn by Western blot. Note that p59fyn coimmunoprecipitates with NCAM in wild-type but not in RPTPα-deficient brains. (C) Wild-type and RPTPα-deficient hippocampal neurons were incubated live with NCAM antibodies to cluster NCAM. Cells were fixed and labeled with antibodies against p59fyn. Note that redistribution of p59fyn to NCAM clusters was reduced in RPTPα-deficient neurons. Bar, 10 μm. The corresponding profiles show NCAM and p59fyn labeling intensities along neurites. The histogram shows mean labeling intensity of p59fyn in NCAM clusters. Mean values ± SEM (n > 20 neurons) are shown in arbitrary units (AU). *, P < 0.05, t test. (D) Wild-type and RPTPα-deficient hippocampal neurons were incubated live with nonspecific IgG or NCAM antibodies, and fixed and labeled with antibodies against p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531. Immunofluorescence signals were inverted to accentuate the difference in immunolabeling intensities between groups. Bar, 10 μm. Note that application of NCAM antibodies increased levels of p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531 in wild type, but not in RPTPα-deficient neurons. The histogram shows mean labeling intensity of p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531 along neurites. Mean values ± SEM (n > 20 neurons) are shown in arbitrary units (AU). *, P < 0.05, t test.

NCAM clustering at the cell surface induces rapid p59fyn activation (Beggs et al., 1997). To analyze whether or not RPTPα is required for NCAM-induced p59fyn activation, we treated live hippocampal neurons from wild-type and RPTPα-deficient mice with NCAM antibodies and analyzed levels of p59fyn dephosphorylated at Tyr-531 along neurites of the stimulated neurons. Clustering of NCAM increased levels of Tyr-531–dephosphorylated p59fyn along neurites of wild-type neurons by ∼60% (Fig. 5 D). However, NCAM-mediated p59fyn activation was completely abolished in RPTPα-deficient neurons (Fig. 5 D), demonstrating that RPTPα is required for NCAM-mediated p59fyn activation.

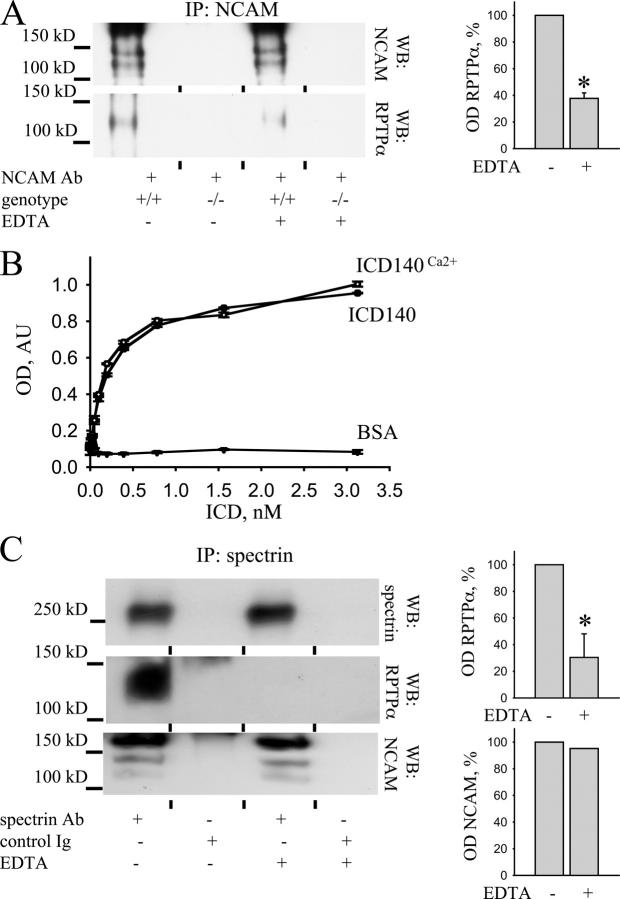

Formation of the complex between RPTPα and NCAM is enhanced by Ca2+

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed either in the presence of Ca2+ or with 2 mM EDTA, a Ca2+-sequestering agent. Whereas RPTPα coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM from brain homogenates under both conditions, coimmunoprecipitated complexes were reduced by ∼60% in the presence of EDTA (Fig. 6 A), suggesting that Ca2+ promotes formation of the NCAM–RPTPα complex. These results are in accordance with findings of Zeng et al. (1999), who found that NCAM and RPTPα did not coimmunoprecipitate in the presence of EDTA. To analyze if the direct interaction between NCAM and RPTPα is Ca2+ dependent, we assayed binding of the intracellular domain of NCAM140 to the intracellular domain of RPTPα by ELISA in the presence or absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 6 B), showing that the direct interaction is Ca2+ independent and suggesting that additional binding partners of NCAM and/or RPTPα may enhance complex formation in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Spectrin, which directly interacts with the intracellular domain of NCAM (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003) and contains a Ca2+ binding domain (De Matteis and Morrow, 2000), is one of the possible candidates. Indeed, RPTPα coimmunoprecipitated with spectrin from brain homogenates (Fig. 6 C). In the presence of 2 mM EDTA, RPTPα coimmunoprecipitating with spectrin was reduced by ∼80% (Fig. 6 C), whereas coimmunoprecipitation of NCAM with spectrin did not depend on Ca2+ (Fig. 6 C). We conclude that RPTPα directly interacts with NCAM in a Ca2+-independent manner. However, formation of the complex is enhanced by Ca2+-dependent cross-linking of NCAM140 and RPTPα via spectrin.

Figure 6.

NCAM–RPTPα complex formation is enhanced by spectrin in a Ca2 + -dependent manner. (A) NCAM immunoprecipitates obtained from brain homogenates of wild-type mice (+/+) in the presence or absence of 2 mM EDTA were probed by Western blot with antibodies against RPTPα. NCAM-deficient brains (−/−) were taken for control. Coimmunoprecipitation of RPTPα was inhibited by EDTA application. The histogram shows quantitation of the blots. (B) Intracellular domains of NCAM140 were bound to plastic and assayed by ELISA for the ability to bind increasing concentrations of RPTPα intracellular domains in the absence of Ca2+ or in the presence of 2 mM Ca2+. Binding to BSA served as a control. Mean values (OD 405) ± SEM (n = 6) are shown. Binding of intracellular domains of RPTPα to intracellular domains of NCAM140 did not depend on Ca2+. (C) Spectrin immunoprecipitates obtained from brain homogenates of wild-type mice in the absence or presence of 2 mM EDTA were probed by Western blot with antibodies against RPTPα or NCAM. Non-immune rabbit Ig (control Ig) were used for control. Coimmunoprecipitation of RPTPα with spectrin was inhibited by EDTA, whereas coimmunoprecipitation of NCAM did not depend on Ca2+. Histograms show quantitation of the blots. For histograms in A and C, OD in the presence of Ca2+ was set to 100% and mean values ± SEM (n = 6) are shown. *, P < 0.05, paired t test.

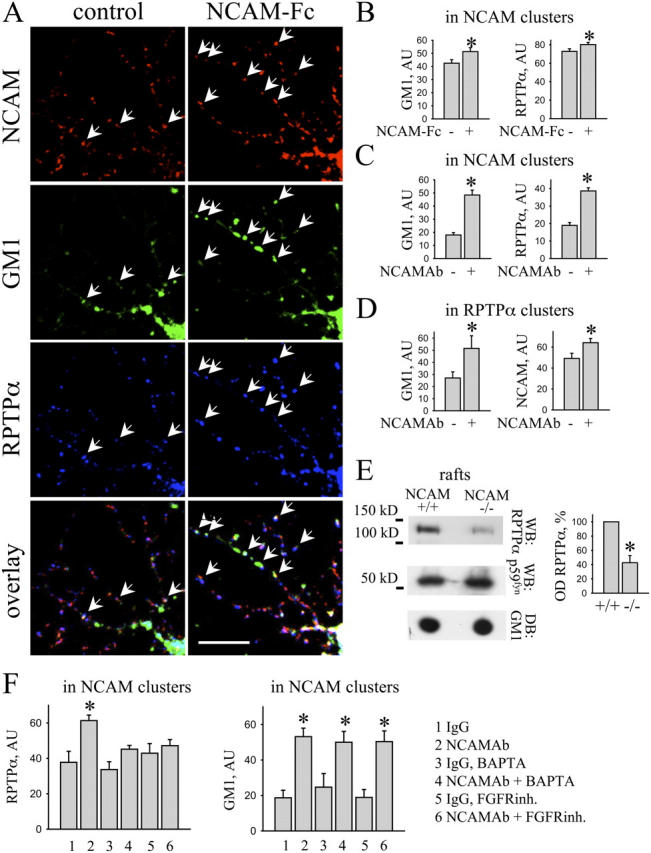

The NCAM–RPTPα complex redistributes to lipid rafts after NCAM activation

Whereas p59fyn is mainly associated with lipid rafts (van't Hof and Resh, 1997; Niethammer et al., 2002; Filipp et al., 2003), only 4–8% of all RPTPα molecules were found in lipid rafts of brain (unpublished data). In hippocampal neurons extracted with cold 1% Triton X-100 to isolate lipid rafts (Niethammer et al., 2002; Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), detergent-insoluble clusters of RPTPα only partially overlapped with the lipid raft marker ganglioside GM1 (Fig. 7 A), further confirming that RPTPα and p59fyn are segregated at the subcellular level. Because activation of NCAM results in its redistribution to lipid rafts (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), it may also promote redistribution of NCAM-associated RPTPα to lipid rafts and thus activate raft-associated p59fyn. To verify this hypothesis, we studied association of NCAM and RPTPα with lipid rafts in hippocampal neurons activated or not activated with NCAM-Fc or NCAM antibodies. In accordance with previous results (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), application of NCAM-Fc or NCAM antibodies increased GM1 levels in detergent-insoluble clusters of NCAM, indicating that NCAM redistributed to lipid rafts (Fig. 7, A–C). Application of NCAM-Fc or NCAM antibodies also increased the level of RPTPα in NCAM clusters, indicating that NCAM activation promoted NCAM–RPTPα complex formation (Fig. 7, A–C). Furthermore, NCAM activation also increased GM1 levels in detergent-insoluble clusters of RPTPα (Fig. 7 D), confirming that NCAM-associated RPTPα also redistributed to lipid rafts and suggesting that NCAM recruits RPTPα to lipid rafts. To further analyze this possibility, we compared levels of RPTPα in lipid rafts in brains of wild-type and NCAM-deficient mice. Indeed, RPTPα was reduced by ∼60% in lipid rafts isolated from NCAM-deficient brains (Fig. 7 E), confirming that NCAM plays a role in RPTPα targeting to lipid rafts. The levels of p59fyn were increased in NCAM-deficient lipid rafts (100% and 124 ± 7.6% in wild-type and NCAM deficient rafts, respectively) probably reflecting increased levels of p59fyn in NCAM-deficient brains. Levels of GM1 were not different in lipid rafts from wild-type and NCAM-deficient brains (100% and 103.3 ± 6.8% in wild-type and NCAM-deficient rafts, respectively), showing that lipid rafts were isolated with the same efficacy from wild-type and NCAM-deficient brains (Fig. 7 E).

Figure 7.

NCAM activation induces redistribution of RPTPα to lipid rafts. (A–D and F) Control hippocampal neurons and neurons incubated with corresponding reagents were extracted in cold 1% Triton X-100 and labeled with antibodies against NCAM and RPTPα together with FITC-labeled cholera toxin to visualize GM1-containing lipid rafts. (A) Note increased overlap of NCAM with RPTPα and GM1 after NCAM-Fc application when compared with control neurons (arrows). Bar, 10 μm. (B and C) Histograms show mean intensities of RPTPα and GM1 in NCAM clusters in control and NCAM-Fc (B) or NCAM antibody (C)–treated neurons. (D) Histograms show mean intensities of NCAM and GM1 in RPTPα clusters in control and NCAM antibody–treated neurons. (E) Lipid rafts obtained from wild-type (+/+) or NCAM-deficient brains (−/−) were probed by Western blot (WB) with antibodies against RPTPα or p59fyn or by dot blot (DB) with cholera toxin. Note reduced amount of RPTPα in rafts from NCAM-deficient brains. The histogram shows quantitation of the RPTPα levels in lipid rafts. OD in wild type was set to 100% and mean values ± SEM (n = 6) are shown. *, P < 0.05, paired t test. (F) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with nonspecific IgG or NCAM antibody alone, or in the presence of BAPTA-AM or FGFR inhibitor. Graphs show mean labeling intensity of RPTPα and GM1 in NCAM clusters. Note that treatment with BAPTA-AM and FGFR inhibitor abolished redistribution of RPTPα to NCAM clusters but not redistribution of NCAM to GM1-positive rafts. Histograms (B–D and F) show mean values ± SEM (n > 50) in arbitrary units (AU). *, P < 0.05, t test.

NCAM-mediated recruitment of RPTPα to lipid rafts is enhanced by NCAM-induced FGF receptor (FGFR)–dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+

NCAM activation increases intracellular Ca2+ concentrations via a FGFR-dependent mechanism (Walsh and Doherty, 1997; Kamiguchi and Lemmon, 2000; Juliano, 2002). This increase in intracellular Ca2+ may account for the enhanced association between NCAM and RPTPα after NCAM activation (Fig. 7, A–D) because of spectrin-mediated cross-linking of NCAM140 and RPTPα (Fig. 6). Interestingly, NCAM activation also induces redistribution of NCAM-associated spectrin to lipid rafts (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). To analyze the role of FGFR and Ca2+ in the recruitment of RPTPα to an NCAM complex, we estimated levels of RPTPα associated with NCAM following NCAM activation in control neurons and neurons incubated with BAPTA-AM, a membrane-permeable Ca2+ chelator (Williams et al., 1992; Cavallaro et al., 2001), or a specific FGFR inhibitor (Niethammer et al., 2002; Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). Whereas NCAM activation increased levels of RPTPα and GM1 in NCAM clusters (Fig. 7 F), treatment with BAPTA-AM or FGFR inhibitor abolished recruitment of RPTPα to NCAM clusters in response to NCAM activation (Fig. 7 F). In accordance with previous findings (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), NCAM redistribution to lipid rafts was not affected by the FGFR inhibitor or BAPTA-AM (Fig. 7 F). BAPTA-AM or FGFR inhibitor did not affect the level of RPTPα associated with NCAM under nonactivated conditions (Fig. 7 F). We conclude that, whereas at resting conditions Ca2+ does not play a major role in the interaction between NCAM and RPTPα, NCAM-induced FGFR-dependent elevations of intracellular Ca2+ levels strengthen the interactions between NCAM and RPTPα in response to NCAM activation, most likely via spectrin (see the section Formation of the complex between RPTPα and NCAM is enhanced by Ca2+).

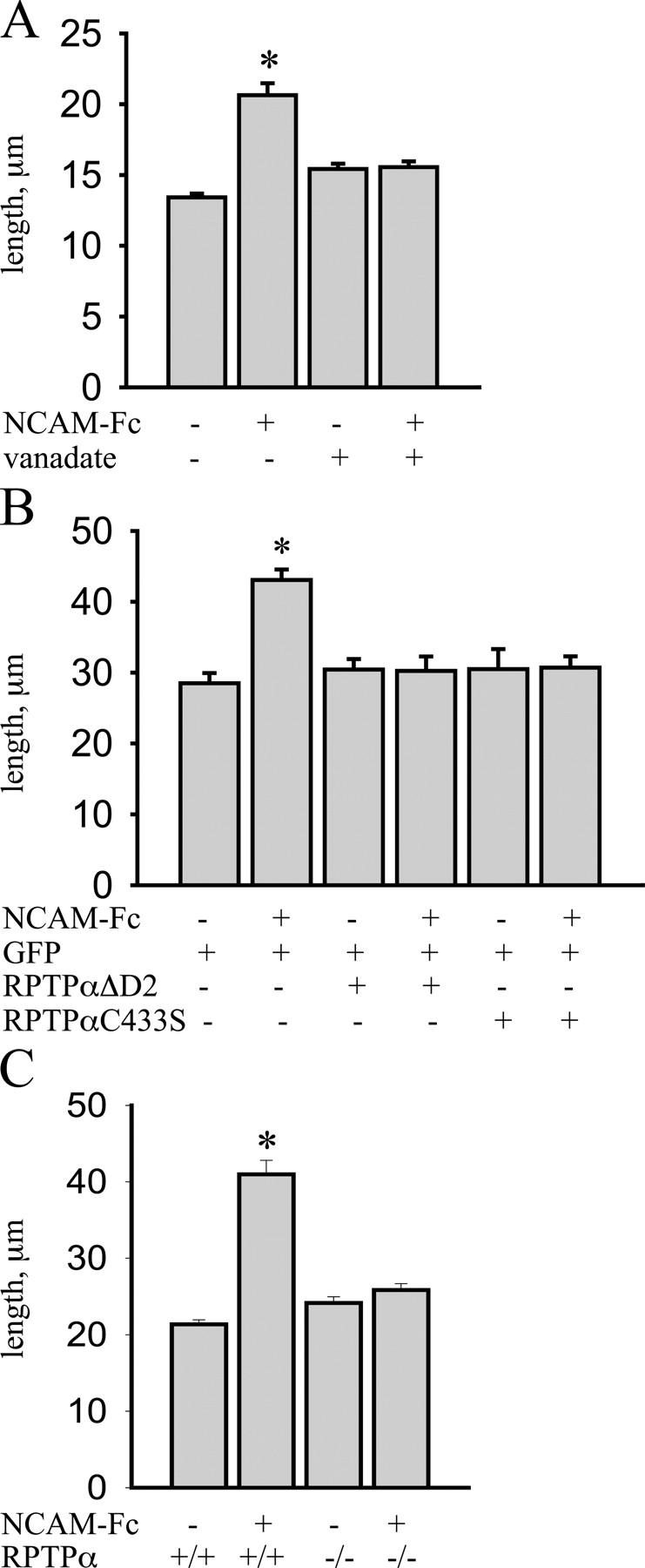

NCAM-induced neurite outgrowth depends on NCAM association with RPTPα

NCAM-induced neurite outgrowth depends on p59fyn activation (Kolkova et al., 2000), suggesting that NCAM association with RPTPα may be involved. To analyze the role of protein tyrosine phosphatases in NCAM-induced neurite outgrowth, we incubated cultured hippocampal neurons with 100 μM vanadate, an inhibitor of these phosphatases (Helmke et al., 1998). NCAM-Fc–enhanced neurite outgrowth was abolished by vanadate, indicating that activation of protein tyrosine phosphatases is required for NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth. Vanadate did not affect neurite outgrowth in nonstimulated neurons, indicating that vanadate does not lead to nonspecific impairments (Fig. 8 A). To directly assess the role of RPTPα in NCAM-induced neurite outgrowth, we transfected hippocampal neurons with the dominant-negative mutants of RPTPα. Both, RPTPαΔD2, which does not bind NCAM but associates with p59fyn, and catalytically inactive RPTPαC433S, which associates with NCAM but binds p59fyn with a lower efficiency than endogenous RPTPα, inhibited association of NCAM with p59fyn by competing with endogenous RPTPα (Fig. 4). In neurons transfected with GFP only, stimulation with NCAM-Fc significantly enhanced neurite length when compared with control nonstimulated neurons (Fig. 8 B). However, neurons transfected with RPTPαΔD2 or RPTPαC433S remained unresponsive to NCAM-Fc stimulation (Fig. 8 B), indicating that RPTPα plays a major role in NCAM-induced neurite outgrowth. To confirm this finding, we analyzed NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth in hippocampal neurons from RPTPα-deficient mice. Whereas NCAM-Fc enhanced neurite outgrowth in neurons from RPTPα wild-type littermates by ∼100%, NCAM-Fc–induced neurite outgrowth was completely abolished in RPTPα-deficient neurons (Fig. 8 C), further confirming that RPTPα is required for NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth.

Figure 8.

NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth depends on RPTPα activation. (A) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with NCAM-Fc alone or with NCAM-Fc together with vanadate, and lengths of the longest neurites were measured. NCAM-Fc increased neurite length when compared with control neurons. Vanadate decreased neurite outgrowth in the NCAM-Fc–stimulated group to the control group level but did not affect basal neurite outgrowth over poly-l-lysine. (B) Hippocampal neurons transfected with GFP alone or cotransfected with GFP and RPTPαC433S or RPTPαΔD2 were incubated with NCAM-Fc after transfection and lengths of the longest neurites were measured. NCAM-Fc increased neurite lengths in GFP-transfected neurons. NCAM-Fc–stimulated neurite outgrowth was blocked in the group cotransfected with RPTPαC433S or RPTPαΔD2. (C) Lengths of the longest neurites were measured in wild-type (+/+) and RPTPα-deficient (−/−) neurons not treated or treated with NCAM-Fc. NCAM-Fc increased neurite length in wild-type but not in RPTPα-deficient neurons. For A–C, mean values ± SEM are shown (n > 150 neurons; *, P < 0.05, t test). Experiments were performed two times with the same effect.

Discussion

It is by now well established that in response to homophilic or heterophilic binding cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily, such as NCAM, L1, or CHL1, activate Src family tyrosine kinases, and in particular pp60c-src or p59fyn, resulting in morphogenetic events, such as cell migration and neurite outgrowth. However, the mechanisms of Src family tyrosine kinase activation in these paradigms have remained unresolved. Here, we identify a cognate activator of p59fyn, the receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase RPTPα, as a novel binding partner of NCAM. Activation of p59fyn is reduced in NCAM-deficient mice and interaction between NCAM and p59fyn is abolished in RPTPα-deficient brains. Interestingly, we found that the levels of p59fyn and RPTPα are increased in NCAM-deficient brains, possibly reflecting a compensatory reaction to the decreased activity of these enzymes in the mutant and further indicating a tight functional relationship between NCAM, RPTPα, and p59fyn. NCAM-induced neurite outgrowth is completely abrogated in RPTPα-deficient neurons or in neurons transfected with dominant-negative RPTPα mutants, indicating that RPTPα links NCAM to p59fyn both physically and functionally.

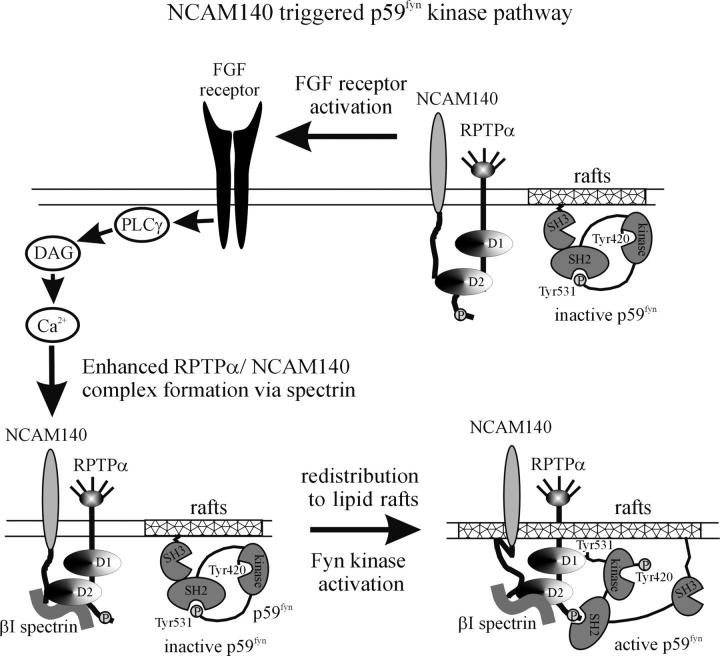

Role of Ca2+ in NCAM–RPTPα–p59fyn complex formation

Interactions between NCAM and RPTPα and NCAM–RPTPα–p59fyn complex formation leading to neurite outgrowth are tightly regulated (Fig. 9). First, whereas direct interaction between NCAM and RPTPα is Ca2+ independent, NCAM–RPTPα complex formation is enhanced by Ca2+-dependent cross-linking via spectrin. Remarkably, NCAM activation results in an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration via influx through Ca2+ channels or release from intracellular stores, and may thus provide a positive feedback loop between NCAM activation and NCAM–RPTPα complex formation involving spectrin. RPTPα binding to spectrin may also elevate RPTPα enzymatic dephosphorylation activity (Lokeshwar and Bourguignon, 1992). Interestingly, NCAM activation also induces activation of PKC (Kolkova et al., 2000; Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), which is known to phosphorylate RPTPα and stimulate its activity (den Hertog et al., 1995; Tracy et al., 1995; Zheng et al., 2002). Thus, a network of activated intracellular signaling molecules may underlie the induction and maintenance of NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth. It is interesting in this respect that the NCAM140 isoform predominates in these interactions: it interacts more efficiently with p59fyn via RPTPα and enhances neurite outgrowth more vigorously than NCAM180 (Niethammer et al., 2002). The structural dispositions of NCAM140 for this preference will remain to be established.

Figure 9.

A proposed model of NCAM140-mediated p59fyn activation cascade. Before NCAM activation, NCAM140 and RPTPα located predominantly in raft-free areas are segregated from p59fyn, which predominantly associates with lipid rafts. NCAM activation induces FGFR-dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+ that enhances RPTPα–NCAM140 complex formation via spectrin as a cross-linking platform. Additionally, NCAM activation results in the redistribution of the complex to lipid rafts due to NCAM palmitoylation. In lipid rafts, RPTPα binds and dephosphorylates p59fyn resulting in p59fyn activation, which, in turn, promotes neurite outgrowth.

The role of lipid rafts

Additional regulation of RPTPα-mediated p59fyn activation is achieved by segregation of RPTPα and p59fyn to different subdomains in the plasma membrane (Fig. 9). Approximately 90% of all RPTPα molecules in the brain are located in a lipid raft-free environment and are thereby segregated from lipid raft-associated p59fyn under nonstimulated conditions. Whereas segregation of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases from their potential substrates due to targeting to different plasma membrane domains has been suggested as a general mechanism of the regulation of receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase function (Petrone and Sap, 2000), the mechanisms that target receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases to lipid rafts have remained unclear. We show that levels of raft-associated RPTPα in the NCAM-deficient brain are reduced, and NCAM redistribution to lipid rafts in response to NCAM activation also induces redistribution of RPTPα to lipid rafts via its NCAM association. The combined observations indicate that NCAM plays a role in recruiting NCAM-associated RPTPα to lipid rafts via NCAM palmitoylation (Niethammer et al., 2002; Fig. 9) or via NCAM interaction with GPI-anchored components of lipid rafts, such as the GPI-linked GDNF receptor (Paratcha et al., 2003). Investigations on the regulatory mechanisms underlying palmitoylation will be required to understand the subcellular compartment-specific distribution of the NCAM–RPTPα–p59fyn complex. Furthermore, the localization of adhesion molecules and receptors will have to be elucidated in view of lipid rafts heterogeneities.

Potential role of protein tyrosine phosphatases in signaling mediated by other cell adhesion molecules

Besides NCAM, activation of L1 and CHL1, other cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily, also results in the activation of Src family tyrosine kinases (Schmid et al., 2000; Buhusi et al., 2003). As for NCAM, the intracellular domains of L1 and CHL1 do not possess structural motif for protein tyrosine phosphatase activity, suggesting that yet unidentified protein tyrosine phosphatases may be involved. Identification of protein tyrosine phosphatases associated with other cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily and conjunctions with RPTPα-activated integrins (Zeng et al., 2003) will be an important next step in the elucidation of the mechanisms that cell adhesion molecules use differentially to guide cell migration and neurite outgrowth in the developing nervous system.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and toxins

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against NCAM (Niethammer et al., 2002) were used in immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and immunocytochemical experiments; and rat mAbs H28 against mouse NCAM (Gennarini et al., 1984) were used in immunocytochemical experiments. Both antibodies recognize the extracellular domain of all NCAM isoforms. Hybridoma clone H28 was a gift of C. Goridis (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique UMR 8542, Paris, France). Rabbit antibodies against RPTPα were a gift of C.J. Pallen (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) or were generated as described previously (den Hertog et al., 1994). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human erythrocyte spectrin, rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the HA tag, nonspecific rabbit immunoglobulins, and cholera toxin B subunit tagged with fluorescein to label GM1 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse mAbs against the HA tag (clone 12CA5) were obtained from Roche Diagnostics. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies and mouse mAbs against p59fyn protein were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Tyr-527–dephosphorylated or Tyr-416–phosphorylated pp60c-src kinase that cross-react with Tyr-531–dephosphorylated or Tyr-420–phosphorylated p59fyn were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Secondary antibodies against rabbit, rat, and mouse Ig coupled to HRP, Cy2, Cy3, or Cy5 were obtained from Dianova.

Animals

To compare wild-type and NCAM-deficient mice, C57BL/6J mice and NCAM-deficient mice (Cremer et al., 1994) inbred for at least nine generations onto the C57BL/6J background were used. NCAM-deficient mice were a gift of H. Cremer (Developmental Biology Institute of Marseille, Marseille, France).To compare wild-type and RPTPα-deficient mice, RPTPα-positive and -negative littermates obtained from heterozygous breeding were used (see online supplemental material).

Image acquisition and manipulation

Coverslips were embedded in Aqua-Poly/Mount (Polysciences, Inc.). Images were acquired at RT using a confocal laser scanning microscope (model LSM510; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.), LSM510 software (version 3; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.), and oil Plan-Neofluar 40× objective (NA 1.3; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) at 3× digital zoom. Contrast and brightness of the images were further adjusted in Photo-Paint 9 (Corel Corporation).

Detergent extraction of cultured neurons

Cells washed in PBS were incubated for 1 min in cold microtubule-stabilizing buffer (2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA, and 60 mM Pipes, pH 7.0) and extracted 8 min on ice with 1% Triton X-100 in microtubule-stabilizing buffer as described previously (Ledesma et al., 1998). After washing with PBS, cells were fixed with cold 4% formaldehyde in PBS.

Colocalization analysis

Colocalization quantification was performed as described previously (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). In brief, an NCAM cluster was defined as an accumulation of NCAM labeling with a mean intensity at least 30% higher than background. NCAM clusters were automatically outlined using the threshold function of the Scion Image software (Scion Corporation). Within the outlined areas the mean intensities of NCAM, RPTPα, p59fyn, or GM1 labeling associated with NCAM cluster were measured. The same threshold was used for all groups. All experiments were performed two to three times with the same effect. Colocalization profiles were plotted using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

DNA constructs

Rat NCAM140 and NCAM180/pcDNA3 were a gift of P. Maness (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). Rat NCAM120 (a gift of E. Bock, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) was subcloned into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) by two EcoRI sites. The EGFP plasmid was purchased from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc. cDNAs encoding intracellular domains of NCAM140 and NCAM180 were as described previously (Sytnyk et al., 2002; Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). The plasmid encoding the intracellular domain of RPTPα was a gift of C.J. Pallen. Wild-type RPTPα, RPTPαC433S, and RPTPαΔD2 (containing RPTPα residues 1–516 [last 6 residues: KIYNKI]) were as described previously (den Hertog and Hunter, 1996; Blanchetot and den Hertog, 2000; Buist et al., 2000).

Online supplemental material

Details on cultures and transfection of hippocampal neurons and CHO cells, immunofluorescence labeling, ELISA and pull-down assay, coimmunoprecipitation, isolation of lipid enriched microdomains, gel electrophoresis, immunoblotting, and generation of RPTPα-deficient mice are given in online supplemental material. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200405073/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Achim Dahlmann and Eva Kronberg for genotyping and animal care, Drs. Patricia Maness and Elisabeth Bock for NCAM cDNAs, Dr. Catherine J. Pallen for antibodies against RPTPα and cDNA encoding the RPTPα intracellular domain, Dr. Harold Cremer for NCAM-deficient mice, and Dr. Christo Goridis for hybridoma clone H28.

This work was supported by Zonta Club, Hamburg-Alster (I. Leshchyns'ka), and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (I. Leshchyns'ka, V. Sytnyk, and M. Schachner).

V. Bodrikov, I. Leshchyns'ka, and V. Sytnyk contributed equally to this paper.

Abbreviations used in this paper: FGFR, FGF receptor; NCAM, neural cell adhesion molecule.

References

- Beggs, H.E., P. Soriano, and P.F. Maness. 1994. NCAM-dependent neurite outgrowth is inhibited in neurons from Fyn-minus mice. J. Cell Biol. 127:825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggs, H.E., S.C. Baragona, J.J. Hemperly, and P.F. Maness. 1997. NCAM140 interacts with the focal adhesion kinase p125(fak) and the SRC-related tyrosine kinase p59(fyn). J. Biol. Chem. 272:8310–8319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, V., K.L. Lim, and C.J. Pallen. 1998. Physical and functional interactions between receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha and p59fyn. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8691–8698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchetot, C., and J. den Hertog. 2000. Multiple interactions between receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase (RPTP) alpha and membrane-distal protein-tyrosine phosphatase domains of various RPTPs. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12446–12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.T., and J.A. Cooper. 1996. Regulation, substrates and functions of src. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1287:121–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi, M., B.R. Midkiff, A.M. Gates, M. Richter, M. Schachner, and P.F. Maness. 2003. Close homolog of L1 is an enhancer of integrin-mediated cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 278:25024–25031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist, A., C. Blanchetot, L.G. Tertoolen, and J. den Hertog. 2000. Identification of p130cas as an in vivo substrate of receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20754–20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, U., J. Niedermeyer, M. Fuxa, and G. Christofori. 2001. N-CAM modulates tumour-cell adhesion to matrix by inducing FGF-receptor signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, H., R. Lange, A. Christoph, M. Plomann, G. Vopper, J. Roes, R. Brown, S. Baldwin, P. Kraemer, S. Scheff, et al. 1994. Inactivation of the N-CAM gene in mice results in size reduction of the olfactory bulb and deficits in spatial learning. Nature. 367:455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossin, K.L., and L.A. Krushel. 2000. Cellular signaling by neural cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Dev. Dyn. 218:260–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis, M.A., and J.S. Morrow. 2000. Spectrin tethers and mesh in the biosynthetic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 113:2331–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog, J., and T. Hunter. 1996. Tight association of GRB2 with receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha is mediated by the SH2 and C-terminal SH3 domains. EMBO J. 15:3016–3027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog, J., C.E. Pals, M.P. Peppelenbosch, L.G. Tertoolen, S.W. de Laat, and W. Kruijer. 1993. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha activates pp60c-src and is involved in neuronal differentiation. EMBO J. 12:3789–3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog, J., S. Tracy, and T. Hunter. 1994. Phosphorylation of receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha on Tyr789, a binding site for the SH3-SH2-SH3 adaptor protein GRB-2 in vivo. EMBO J. 13:3020–3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog, J., J. Sap, C.E. Pals, J. Schlessinger, and W. Kruijer. 1995. Stimulation of receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha activity and phosphorylation by phorbol ester. Cell Growth Differ. 6:303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipp, D., J. Zhang, B.L. Leung, A. Shaw, S.D. Levin, A. Veillette, and M. Julius. 2003. Regulation of Fyn through translocation of activated Lck into lipid rafts. J. Exp. Med. 197:1221–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennarini, G., M. Hirn, H. Deagostini-Bazin, and C. Goridis. 1984. Studies on the transmembrane disposition of the neural cell adhesion molecule N-CAM. The use of liposome-inserted radioiodinated N-CAM to study its transbilayer orientation. Eur. J. Biochem. 142:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder, K.W., N.P. Moller, J.W. Peacock, and F.R. Jirik. 1998. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha regulates Src family kinases and alters cell-substratum adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 273:31890–31900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Q., and K.F. Meiri. 2002. Isolation and characterization of detergent-resistant microdomains responsive to NCAM-mediated signaling from growth cones. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 19:18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmke, S., K. Lohse, K. Mikule, M.R. Wood, and K.H. Pfenninger. 1998. SRC binding to the cytoskeleton, triggered by growth cone attachment to laminin, is protein tyrosine phosphatase-dependent. J. Cell Sci. 111:2465–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, S.R. 1999. Src autoinhibition: let us count the ways. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:711–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida, N., V.B. Lokeshwar, and L.Y. Bourguignon. 1994. Mapping the fodrin binding domain in CD45, a leukocyte membrane-associated tyrosine phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 269:28576–28583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano, R.L. 2002. Signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors and the cytoskeleton: functions of integrins, cadherins, selectins, and immunoglobulin-superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 42:283–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiguchi, H., and V. Lemmon. 2000. IgCAMs: bidirectional signals underlying neurite growth. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R., B. Morse, K. Huebner, C. Croce, R. Howk, M. Ravera, G. Ricca, M. Jaye, and J. Schlessinger. 1990. Cloning of three human tyrosine phosphatases reveals a multigene family of receptor-linked protein-tyrosine-phosphatases expressed in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:7000–7004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolkova, K., V. Novitskaya, N. Pedersen, V. Berezin, and E. Bock. 2000. Neural cell adhesion molecule-stimulated neurite outgrowth depends on activation of protein kinase C and the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J. Neurosci. 20:2238–2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, E.M., C. Klein, T. Koch, M. Boytinck, and J. Trotter. 1999. Compartmentation of Fyn kinase with glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored molecules in oligodendrocytes facilitates kinase activation during myelination. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29042–29049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.X., M. Streuli, and H. Saito. 1990. Structural diversity and evolution of human receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatases. EMBO J. 9:3241–3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, M.D., K. Simons, and C.G. Dotti. 1998. Neuronal polarity: essential role of protein-lipid complexes in axonal sorting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:3966–3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshchyns'ka, I., V. Sytnyk, J.S. Morrow, and M. Schachner. 2003. Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) association with PKCβ2 via βI spectrin is implicated in NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth. J. Cell Biol. 161:625–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokeshwar, V.B., and L.Y. Bourguignon. 1992. Tyrosine phosphatase activity of lymphoma CD45 (GP180) is regulated by a direct interaction with the cytoskeleton. J. Biol. Chem. 267:21551–21557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer, P., M. Delling, V. Sytnyk, A. Dityatev, K. Fukami, and M. Schachner. 2002. Cosignaling of NCAM via lipid rafts and the FGF receptor is required for neuritogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 157:521–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paratcha, G., F. Ledda, and C.F. Ibanez. 2003. The neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM is an alternative signaling receptor for GDNF family ligands. Cell. 113:867–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrone, A., and J. Sap. 2000. Emerging issues in receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase function: lifting fog or simply shifting? J. Cell Sci. 113:2345–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrone, A., F. Battaglia, C. Wang, A. Dusa, J. Su, D. Zagzag, R. Bianchi, P. Casaccia-Bonnefil, O. Arancio, and J. Sap. 2003. Receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha is essential for hippocampal neuronal migration and long-term potentiation. EMBO J. 22:4121–4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponniah, S., D.Z. Wang, K.L. Lim, and C.J. Pallen. 1999. Targeted disruption of the tyrosine phosphatase PTPalpha leads to constitutive downregulation of the kinases Src and Fyn. Curr. Biol. 9:535–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, R.S., R.D. Graff, M.D. Schaller, S. Chen, M. Schachner, J.J. Hemperly, and P.F. Maness. 1999. NCAM stimulates the Ras-MAPK pathway and CREB phosphorylation in neuronal cells. J. Neurobiol. 38:542–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, R.S., W.M. Pruitt, and P.F. Maness. 2000. A MAP kinase-signaling pathway mediates neurite outgrowth on L1 and requires Src-dependent endocytosis. J. Neurosci. 20:4177–4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, J., L.T. Yang, and J. Sap. 1996. Association between receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase RPTPalpha and the Grb2 adaptor. Dual Src homology (SH) 2/SH3 domain requirement and functional consequences. J. Biol. Chem. 271:28086–28096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytnyk, V., I. Leshchyns'ka, M. Delling, G. Dityateva, A. Dityatev, and M. Schachner. 2002. Neural cell adhesion molecule promotes accumulation of TGN organelles at sites of neuron-to-neuron contacts. J. Cell Biol. 159:649–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.M., and J.S. Brugge. 1997. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:513–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S., P. van der Geer, and T. Hunter. 1995. The receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase, RPTP alpha, is phosphorylated by protein kinase C on two serines close to the inner face of the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 270:10587–10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van't Hof, W., and M.D. Resh. 1997. Rapid plasma membrane anchoring of newly synthesized p59fyn: selective requirement for NH2-terminal myristoylation and palmitoylation at cysteine-3. J. Cell Biol. 136:1023–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wichert, G., G. Jiang, A. Kostic, K. De Vos, J. Sap, and M.P. Sheetz. 2003. RPTP-α acts as a transducer of mechanical force on αv/β3-integrin–cytoskeleton linkages. J. Cell Biol. 161:143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F.S., and P. Doherty. 1997. Neural cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily: role in axon growth and guidance. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:425–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., and C.J. Pallen. 1991. The receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase HPTP alpha has two active catalytic domains with distinct substrate specificities. EMBO J. 10:3231–3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, E.J., P. Doherty, G. Turner, R.A. Reid, J.J. Hemperly, and F.S. Walsh. 1992. Calcium influx into neurons can solely account for cell contact–dependent neurite outgrowth stimulated by transfected L1. J. Cell Biol. 119:883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L., A. Buist, J. den Hertog, and Z.Y. Zhang. 1997. Comparative kinetic analysis and substrate specificity of the tandem catalytic domains of the receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 272:6994–7002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.T., K. Alexandropoulos, and J. Sap. 2002. c-SRC mediates neurite outgrowth through recruitment of Crk to the scaffolding protein Sin/Efs without altering the kinetics of ERK activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17406–17414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L., L. D'Alessandri, M.B. Kalousek, L. Vaughan, and C.J. Pallen. 1999. Protein tyrosine phosphatase α (PTPα) and contactin form a novel neuronal receptor complex linked to the intracellular tyrosine kinase fyn. J. Cell Biol. 147:707–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L., X. Si, W.P. Yu, H.T. Le, K.P. Ng, R.M. Teng, K. Ryan, D.Z. Wang, S. Ponniah, and C.J. Pallen. 2003. PTPα regulates integrin-stimulated FAK autophosphorylation and cytoskeletal rearrangement in cell spreading and migration. J. Cell Biol. 160:137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.M., Y. Wang, and C.J. Pallen. 1992. Cell transformation and activation of pp60c-src by overexpression of a protein tyrosine phosphatase. Nature. 359:336–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.M., R.J. Resnick, and D. Shalloway. 2000. A phosphotyrosine displacement mechanism for activation of Src by PTPalpha. EMBO J. 19:964–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.M., R.J. Resnick, and D. Shalloway. 2002. Mitotic activation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase alpha and regulation of its Src-mediated transforming activity by its sites of protein kinase C phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:21922–21929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]