Abstract

Simian Virus 40 (SV40) has been shown to enter host cells by caveolar endocytosis followed by transport via caveosomes to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Using a caveolin-1 (cav-1)–deficient cell line (human hepatoma 7) and embryonic fibroblasts from a cav-1 knockout mouse, we found that in the absence of caveolae, but also in wild-type embryonic fibroblasts, the virus exploits an alternative, cav-1–independent pathway. Internalization was rapid (t 1/2 = 20 min) and cholesterol and tyrosine kinase dependent but independent of clathrin, dynamin II, and ARF6. The viruses were internalized in small, tight-fitting vesicles and transported to membrane-bounded, pH-neutral organelles similar to caveosomes but devoid of cav-1 and -2. The viruses were next transferred by microtubule-dependent vesicular transport to the ER, a step that was required for infectivity. Our results revealed the existence of a virus-activated endocytic pathway from the plasma membrane to the ER that involves neither clathrin nor caveolae and that can be activated also in the presence of cav-1.

Introduction

In addition to clathrin-mediated endocytosis and phagocytosis, animal cells support a variety of other mechanisms for internalizing plasma membrane components, fluid, and surface-bound ligands (Dautry-Varsat, 2000; Johannes and Lamaze, 2002; Conner and Schmid, 2003; Nabi and Le, 2003; Nichols, 2003; Parton and Richards, 2003; Pelkmans and Helenius, 2003). Some of these mechanisms involve the selective internalization of glycolipids, cholesterol, GPI-anchored proteins, lipid raft–associated receptors as well as a variety of ligands that bind to them. Such ligands include autocrine motility factor, serum albumin, cholera and shiga toxin, interleukin-2, and ligands that bind to GPI-anchored proteins (Benlimame et al., 1998; Lamaze et al., 2001; Nichols, 2003; Parton and Richards, 2003; Peters et al., 2003; Williams and Lisanti, 2004). In addition to endocytosis, the nonclathrin pathways are thought to play a role in signal transduction, transcytosis, and the homeostasis of cholesterol (Anderson, 1998; Simons and Ikonen, 2000; Simons and Toomre, 2000; Williams and Lisanti, 2004).

To learn more about these elusive processes, we use animal viruses. Although many viruses enter via clathrin-coated pits and endosomes (Marsh and Helenius, 1989), some make use of clathrin-independent pathways (Gilbert and Benjamin, 2000; Sieczkarski and Whittaker, 2002; Pelkmans and Helenius, 2003). One of the viruses that enter without the help of clathrin is simian virus 40 (SV40), a simple, well-characterized, nonenveloped DNA virus that replicates in the nucleus (Kasamatsu and Nakanishi, 1998). It enters many cell types by a process that involves cell surface caveolae (Anderson et al., 1996; Norkin, 2001; Pelkmans et al., 2001; Parton and Richards, 2003). Caveolae are lipid raft–enriched, flask-shaped plasma membrane indentations stabilized by caveolins, which are cholesterol-binding, integral membrane proteins (Rothberg et al., 1992). Caveolae occur in cells that express either caveolin-1 (cav-1) or its muscle cell–specific homologue, caveolin-3. They give caveolae their characteristic size and indented shape (Fra et al., 1995). Whereas caveolae are present at high concentrations on adipocytes, muscle cells, and endothelial cells, there are few caveolae in hepatocytes and none in neuronal cells and lymphocytes (Drab et al., 2001; Lamaze et al., 2001; Vainio et al., 2002).

Most cell surface caveolae show limited motility and dynamics (Thomsen et al., 2002). However, when triggered by an appropriate ligand such as SV40, activation of tyrosine kinases induces a signaling cascade that results in slow but efficient internalization (Pelkmans et al., 2002; Parton and Richards, 2003). Like clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolar vesicle formation involves recruitment of dynamin II, a GTPase involved in the final stage of vesicle scission (De Camilli et al., 1995; Oh et al., 1998; Pelkmans et al., 2002). Although some of the caveolar ligands are sorted to endosomes and the Golgi complex after internalization (Parton and Richards, 2003), many are transported to caveosomes (Pelkmans et al., 2001; Nichols, 2003; Peters et al., 2003). These are cav-1–positive, pH-neutral organelles distinct from compartments of the classical endocytic and exocytic pathways. From caveosomes, SV40 is transported by a microtubule-mediated process to the ER, where penetration into the cytosol is thought to occur (Pelkmans et al., 2001). From the cytosol, the virus particles enter the nucleus through nuclear pore complexes (Kasamatsu and Nakanishi, 1998).

We have analyzed what happens when SV40 is added to cells devoid of caveolae. We found that the virus entered by an alternative tyrosine kinase– and cholesterol-dependent endocytic pathway, and the cells were infected. The pathway differed from the caveolar pathway in that it was rapid and dynamin II independent. It bypassed the classical endocytic organelles and delivered the virus via nonendosomal, cytosolic organelles to the ER. In wild-type mouse embryonic fibroblasts, the virus apparently used the same dynamin II–independent uptake pathway with a major fraction of viruses internalized independently of cav-1. The results provided information about an endocytic cholesterol-dependent pathway that can exist in parallel with the caveolar pathway. Both pathways apparently merge at the level of caveosomes.

Results

SV40 infects cells devoid of caveolae

We used two types of cav-1–deficient cells: primary embryonic fibroblasts derived from cav-1 knockout (KO) mice (cav-1KO cells; Drab et al., 2001) and a human hepatoma cell line (human hepatoma 7 [HuH7]), also devoid of cav-1 (Vainio et al., 2002). Western blots confirmed that, in contrast to embryonic fibroblasts from a wild-type mouse (cav-1 wild-type [cav-1WT] cells), neither CV-1 or MDCK cells contained detectable cav-1 (Fig. S1 A, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). Although showing no cav-1 staining in the cav-1KO cells, and only weak background staining in HuH7 cells, immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy revealed that both cell lines contained cav-2 in the Golgi complex (Fig. S1 B). This observation was consistent with reports that association with cav-1 is necessary for the transport of cav-2 to peripheral sites (Parolini et al., 1999). Although present in caveolae, cav-2 alone is not able to form caveolae.

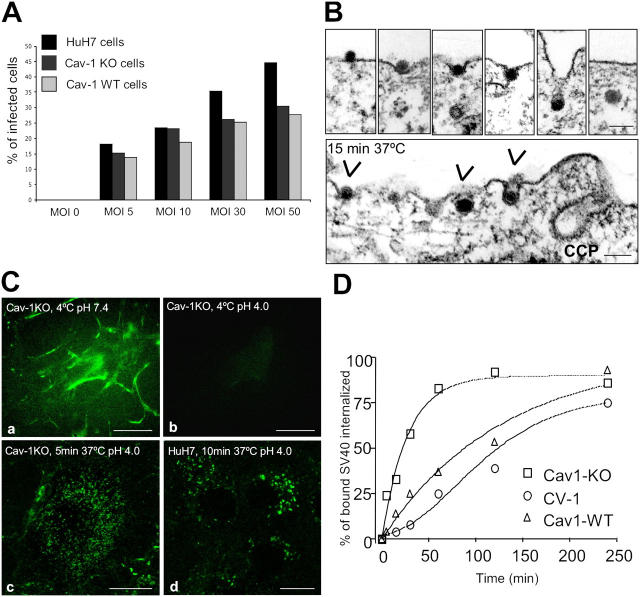

To test whether or not the cells could be infected, they were incubated with SV40, and after 20 h subjected to immunofluorescence using an antibody against T-antigen, a viral protein synthesized early in infection. The results showed that a large fraction of the cells expressed the viral protein (Fig. 1 A) and that there was essentially no difference in infection between cav-1WT and cav-1KO cells. In comparison, CV-1 cells, which are cav-1–positive kidney cells from the natural host of SV40 (the African green monkey), are infected 10 times more efficiently (Pelkmans et al., 2002). To stay in the linear range of the assay, all infection experiments were performed with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 or 30.

Figure 1.

Cav-1KO and HuH7 cells internalize SV40 and are infected. (A) All cell lines were incubated with different MOIs and analyzed for T-antigen expression after 20 h. (B) Electron micrographs of cav-1KO cells after incubation for 15 min with SV40 at 37°C. Arrowheads point to internalizing virus particles. CCP, clathrin-coated pit. Bars, 100 nm. (C) FITC-labeled SV40 was bound to cav-1KO and HuH7 cells at 4°C and allowed to internalize after shifting to 37°C. Lowering the extracellular pH to 4.0 allowed visualization of only those virus particles that had been internalized. Bars, 10 μm. (D) Internalization of 125I-labeled biotin-SS-SV40 in cav-1WT, cav-1KO, and CV-1 cells. Cells were incubated at 4°C for 2 h and shifted to 37°C in the continuous presence of the virus. At the indicated time points, cells were analyzed for the amount of internalized virus (Pelkmans et al., 2002).

SV40 endocytosis in the absence of caveolae

Thin section electron microscopy after incubation with SV40 for 15 min at 37°C showed that the virus was internalized by tight-fitting vesicles (60-nm diameter) similar to SV40-containing vesicles in CV-1 cells (Kartenbeck et al., 1989). However, the particles did not seem to enter preexisting, caveolar-sized pits but rather indentations that seemed to progressively adopt the rounded shape of the virus with the membrane tightly associated with the surface of the virus (Fig. 1 B). The viruses did not associate with clathrin-coated pits.

To characterize the internalization process by light microscopy, and to quantify it biochemically, two assays were used (Pelkmans et al., 2001, 2002). First, fluorescein-labeled SV40 (FITC-SV40) was added to cells in the cold, and after washing and raising the temperature to 37°C, the fate of the bound virus particles was determined by confocal microscopy. To distinguish between internalized and noninternalized particles, the pH in the extracellular medium was lowered to 4. This quenched the FITC-fluorescence of noninternalized particles and allowed detection of internalized viruses in organelles of neutral pH (Pelkmans et al., 2001). The results showed that already after 5–10 min at 37°C, a large fraction of the FITC-SV40 had been internalized. Fluorescence could be seen in small spots throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 1 C, c and d). Acid quenching without prior warming resulted in the complete loss of fluorescence (Fig. 1 C, b).

The second assay made use of 125I- and biotin-coupled virus particles and a membrane-impermeable reducing agent to remove the biotin from exposed virions (Pelkmans et al., 2002). The results showed that SV40 internalization into cav-1KO cells started immediately after warming, proceeding rapidly with a t 1/2 of 20 ± 3 min and reaching maximum (95%) within an hour (Fig. 1 D). Uptake was considerably faster than in CV-1 cells (t 1/2 = 101 ± 11 min). When the same assay was applied to cav-1WT cells, the uptake was found to be equally efficient as in the cav-1KO cells but the t 1/2 was considerably longer (t 1/2 = 98 ± 15 min).

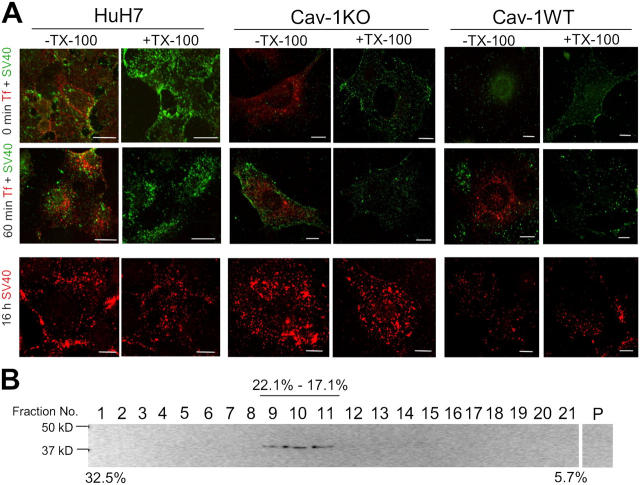

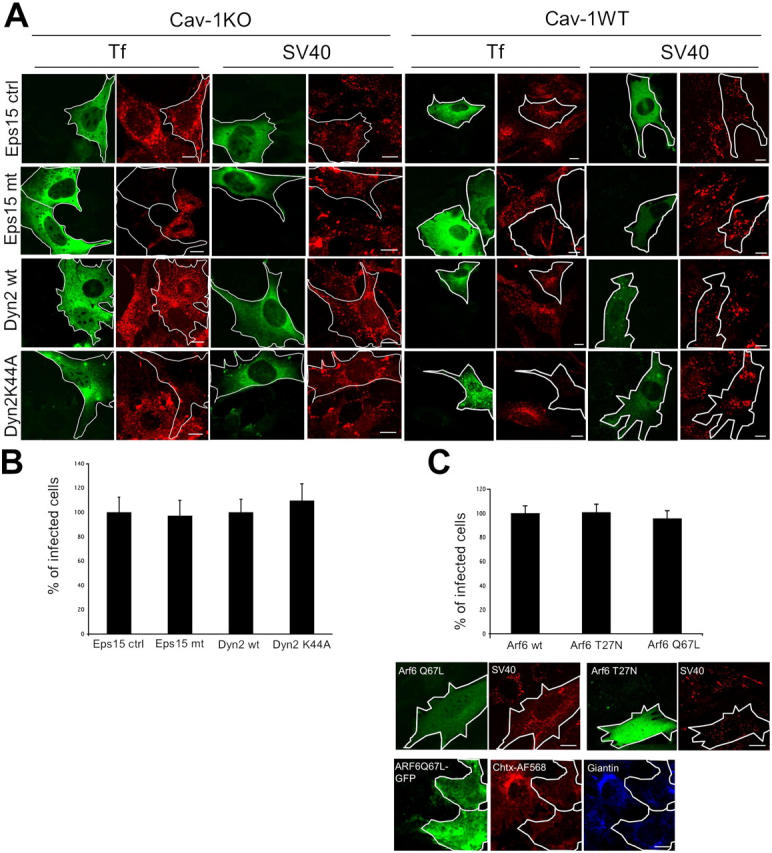

A clathrin-, dynamin II–, and ARF6-independent mechanism

Expression of dominant-negative Eps15 (EΔ95/295), which interferes with clathrin-coated pit assembly (Benmerah et al., 1999), did not inhibit infection of cav-1KO (Fig. 2 B) or HuH7 cells (Fig. S2 B, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). Nor was internalization of Alexafluor (AF) 594-SV40 into cav-1WT, cav-1KO, or HuH7 cells impaired, although internalization of AF568-labeled transferrin (Tf), a marker for clathrin-mediated uptake, was dramatically reduced (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S2 A). This result indicated that SV40 did not depend on clathrin for endocytosis.

Figure 2.

Internalization and infection of SV40 occurs independently of Eps15, Dynamin II, and ARF6. Cav-1KO and cav-1WT cells were transfected with Eps15IIIΔ2 (Eps15 ctrl), Eps15 EΔ95/295 (Eps15 mt), Dyn2wt, or Dyn2K44A, all tagged with GFP. (A) After transfection, cells were incubated with AF594-SV40 for 2 h, fixed, and examined in confocal microscopy. AF594-Tf served as a positive control. Representative images are shown. Bars, 10 μm. (B) After transfection, cav-1KO cells were infected with SV40 for 20 h, fixed, and analyzed for infection. Infection in cells expressing the control constructs was set at 100%. Values are given as the mean ± SD. (C) Cav-1KO cells were cotransfected with ARF6 wild type, ARF6 T27N, ARF6 Q67L, and GFP. After transfection, cells were infected with SV40 for 20 h, fixed, and analyzed for infection. Infection in cells expressing the wild-type construct was set at 100%. Values are given as the mean ± SD. Alternatively, cells were incubated with AF594-SV40 for 1.5 h and imaged live. As a positive control, ARF6 Q67L-GFP–transfected cells were incubated with cholera toxin-AF568, fixed, and immunostained with an anti-giantin antibody (blue). Bars, 10 μm.

Dynamin II is involved in the formation of both clathrin-coated and caveolar vesicles (De Camilli et al., 1995; Oh et al., 1998). Expression of a dominant-negative dynamin II mutant (dyn2K44A; Fish et al., 2000) inhibits SV40 internalization as well as infection in CV-1 cells by 80% (Pelkmans et al., 2002). However, when dyn2K44A was expressed in cav-1KO and HuH7 cells neither SV40 internalization nor infection were affected (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S2, A and B). Strikingly, SV40 internalization was also unaffected in cav-1WT cells expressing dyn2K44A. As expected, we observed virtually complete inhibition of Tf internalization in these cell lines (Fig. 2 A and Fig. S2 A). We concluded that SV40 uptake in caveolin-deficient cells occurred by clathrin-independent mechanisms, and that, in contrast to caveolar internalization in CV-1 cells, dynamin II was not required for SV40 uptake into cav-1WT, cav-1KO, and HuH7 cells.

ARF6 has been described to be an important factor in the clathrin- and caveolae- independent endocytosis of MHC class I, IL2 receptor α subunit (Tac), carboxypeptidase E, and the GPI-anchored protein CD59 (Arnaoutova et al., 2003; Naslavsky et al., 2003, 2004). Neither expression of a constitutively active ARF6 mutant (ARF6 Q67L) nor of the constitutively inactive form (ARF6 T27N) in cav-1KO cells inhibited SV40 infection (Fig. 2 C). Internalization of SV40 was also not affected (Fig. 2 C). It was recently reported that ARF6 is required for cholera toxin transport to the Golgi in cav-1KO cells (Kirkham, M., A. Fujita, S.J. Nixon, T.V. Kurzchalia, J.F. Hancock, R.G. Parton. European Life Scientist Organization Meeting. 2004. 542). Therefore, as a control, ARF6 Q67L–expressing cav-1KO cells were incubated with cholera toxin-AF568 for 45 min, fixed, and immunostained with an anti-giantin antibody. Whereas in untransfected control cells cholera toxin reached the Golgi, no colocalization in ARF6 Q67L-GFP–expressing cells was observed with giantin.

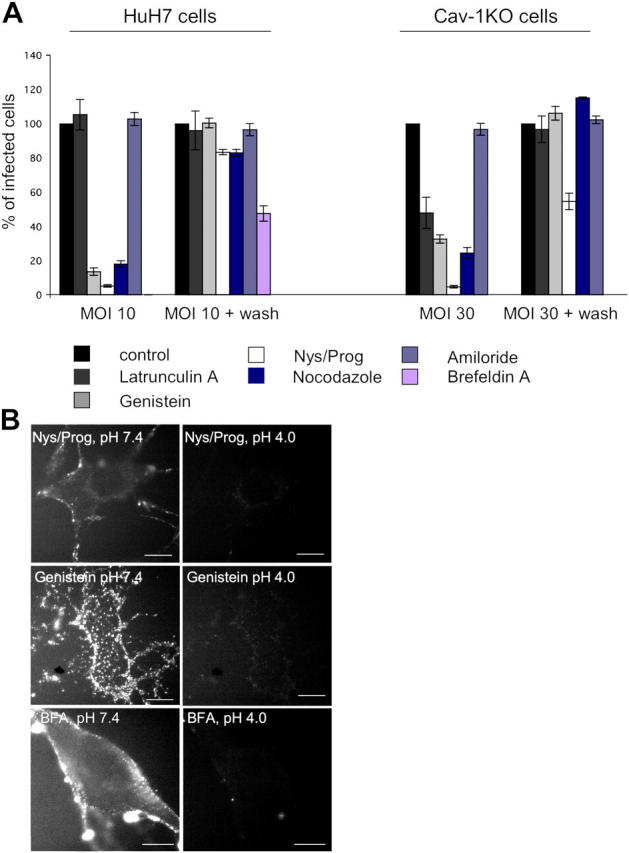

The effect of inhibitors

To investigate the role of other cellular components, we made use of inhibitors known to affect endocytic processes. Cav-1KO or HuH7 cells were pretreated with the drug, exposed to SV40 in the continued presence of the drug, and fixed after 20 h incubation. The fraction of cells expressing T-antigen was determined and compared with untreated control cells. To confirm that drug-induced effects were reversible, we assayed SV40 infectivity after drug wash-out at 20 h.

Combined cholesterol depletion by nystatin and inhibition of cholesterol synthesis by progesterone resulted in an almost complete infection block (Fig. 3 A). Genistein (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and nocodazole (a microtubule-dissociating drug) also reduced infection dramatically. Brefeldin A (BFA), a drug affecting the activation of Arf1, induced a complete block of infection in HuH7 cells. The results suggested that infection of cells devoid of caveolae required cholesterol, tyrosine kinases, Arf1, and a functional microtubule skeleton. That nystatin/progesterone, BFA, and genistein caused inhibition of virus internalization was shown by the FITC-based internalization assay; after 1 h of incubation at 37°C, FITC-SV40 could still be quenched by lowering extracellular pH in drug-treated cav-1KO cells (Fig. 3 B). Latrunculin A, an actin monomer-sequestering drug, did not have any influence on SV40 infection in HuH7 cells and reduced infectivity in cav-1KO cells by 50%. To show that Latrunculin A disassembled filamentous actin, cav-1KO and HuH7 cells were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). Amiloride, a Na+/H+ channel blocker that inhibits macropinocytosis, also did not affect infection.

Figure 3.

Caveolae- and clathrin-independent SV40 infection requires cholesterol, tyrosine kinases, and a functional microtubule cytoskeleton. (A) HuH7 and cav-1KO cells were either left untreated (control) or pretreated with the indicated drugs and incubated with SV40 for 2 h in the presence of drugs. Virus was removed and cells were further incubated either in the presence of drugs or as a control after drug washout (MOI 10 + wash in HuH7 and MOI 30 + wash in cav-1KO cells). 20 h after infection, cells were analyzed for expression of T-antigen. Values are given as the mean ± SD. (B) Cav-1KO cells were pretreated with nystatin/progesterone, genistein, or BFA and incubated with FITC-SV40 for 1 h. Fluorescence of not internalized viruses was quenched by lowering the extracellular pH to 4. Bars, 10 μm.

An intermediate organelle

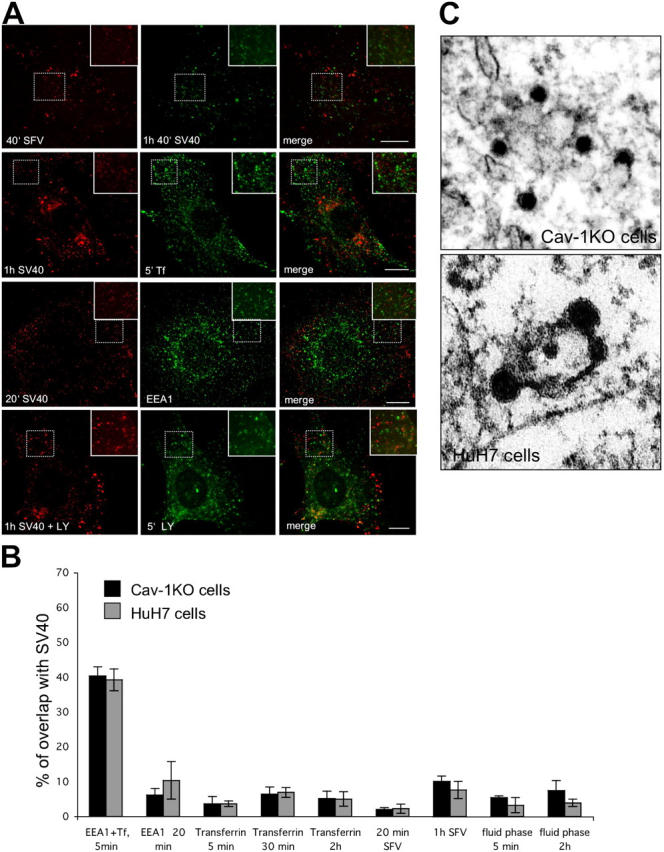

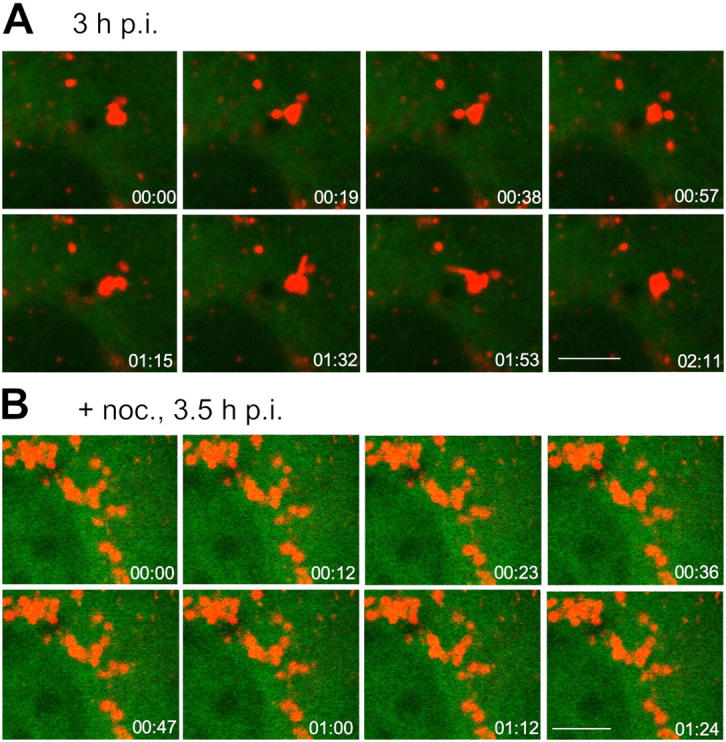

When the distribution of internalized AF594-SV40 was visualized using confocal microscopy, the viruses could be observed in discrete spots of variable sizes and shapes distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 4 A and Fig. S4, A and B, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). Typically, there were more than 100 such spots per cell. Thin section electron microscopy showed that the viruses were localized in membrane-bounded organelles of irregular shape (Fig. 4 C). The virus particles were still attached to the limiting membrane over a large part of their surface. Video microscopy after internalization of AF594-SV40 showed that although the organelles underwent continuous local motion, they behaved like caveosomes in that they seldom moved long distances (Videos 1 and 2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). About 2 h after filling up with viruses, the organelles became more dynamic, undergoing fusion and releasing virus-filled vesicles (Videos 3 and 4, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). The dynamic phase lasted until ∼3.5 h after warming.

Figure 4.

SV40-containing organelles are distinct from organelles of the classical endosomal pathway. (A) Cav-1KO cells were incubated with AF488-SV40 or AF594-SV40 and the endosomal markers AF594-SFV (first row) or AF488-Tf (second row) for the indicated times, fixed, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. SV40-carrying vesicles did not contain markers specific for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The same was shown by immunofluorescence of fixed cav-1KO cells (third row) incubated with AF594-SV40 and stained with the early endosomal marker EEA1 (green). In cav-1KO cells incubated with AF594-SV40 and the fluid phase marker Lucifer yellow (LY), only a minor portion of SV40-carrying vesicles contained LY (fourth row). Bars, 10 μm. (B) Quantification of colocalization with endosomal and fluid phase markers in cav-1KO and HuH7 cells after various times. As a control, the first two bars show overlap between Tf and EEA1. Values are given as the mean ± SD. (C) Thin section electron micrographs of cav-1KO and HuH7 cells showing virus particles in intermediate organelles that resemble caveosomes.

To determine the relationship between the virus-containing organelles and other endocytic structures, we internalized AF488-Tf and AF594-Semliki Forest virus (SFV) together with AF594-SV40 and AF488-SV40, respectively. Tf and SFV are known to be internalized via clathrin-mediated endocytosis into endosomes. The overlap between SV40 and Tf was almost nonexistent in both cell types (Fig. 4, A and B; and Fig. S4 A). When quantified, it was found to be 6.4% in cav-1KO and 6.9% in HuH7 cells, which is probably close to background. In a control, internalization of AF488-Tf for 5 min followed by immunostaining against EEA1 showed 40.3% overlap in cav-1KO and 39.2% overlap in HuH7 cells (Fig. 4 B, first two columns). Two fluorescent fluid-phase markers, Lucifer yellow (LY) and AF594-10K Dextran, were also allowed to be internalized together with the AF594-SV40. Again the overlap was negligible (Fig. 4, A and B; and Fig. S4). Indirect immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy showed that the major portion of SV40-containing vesicles lacked EEA1, a marker of early endosomes (Fig. 4, A and B; and Fig. S4 A). The overlap remained at equally low levels when SV40 was chased with these endocytic markers up to 4 h. Also in cav-1WT cells there was no considerable overlap of internalized SV40 with the endosomal markers SFV, Tf, and LY (Fig. S4 B).

To exclude that the virus-containing vesicles constitute invaginations connected to the plasma membrane, we made use of FITC-quenching as described for Fig. 1 C. HuH7 cells were incubated with FITC-SV40 for 2 h, and the pH of the extracellular medium was lowered to 4 to quench the fluorescence of noninternalized viruses (Fig. S4 C, b). Although the fluorescence was reduced partially, there were numerous FITC-SV40–containing vesicles that continued to be brightly fluorescent. When added to the low pH medium, the ionophores monensin and nigericin (10 μM each) equilibrated extra- and intracellular pH, resulting in an almost complete loss of fluorescence of internalized vesicles (Fig. S4 C, c). We concluded that the virus accumulated in organelles that were disconnected from the plasma membrane and had a nonacidic pH.

Association with detergent-resistant membranes

The sensitivity of infection to cholesterol depletion suggested that internalization might involve cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich microdomains, i.e., so-called lipid rafts. To approach this possibility, we performed Triton X-100 extraction of cells exposed to AF488-SV40 and AF568-Tf at 4°C either immediately after binding the ligands to the plasma membrane in the cold or after shifting to 37°C for various periods of time. The rationale was that cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich membrane domains are more resistant to Triton X-100 solubilization at reduced temperatures than nonraft membranes (Brown and Rose, 1992).

Confocal microscopy showed that Triton X-100 extraction of unfixed HuH7, cav-1KO, and cav-1WT cells on coverslips completely extracted the AF568-Tf, a ligand bound to a receptor that does not associate with detergent-resistant membranes (Lamaze et al., 2001). However, AF488-SV40 remained unextracted, both in the plasma membrane at 4°C and in intracellular structures after warming for 10, 30, 60, and 240 min. Even after 16 h, a large fraction of the AF488-SV40 was still detergent resistant (Fig. 5 A). We concluded that AF488-SV40 was bound to detergent-resistant membranes already in the cold, and remained associated with such structures during and after internalization.

Figure 5.

Association of SV40 with detergent-insoluble membranes. (A) Internalized SV40 but not Tf is resistant to Triton X-100 extraction at 4°C. AF488-SV40 and AF568-Tf were bound to HuH7 (left), cav-1KO (middle), and cav-1WT cells (right) on ice and allowed to internalize for the indicated times. The cells were washed, extracted for 5 min on ice with 1% Triton X-100, and fixed. Bars, 10 μm. (B) SV40 associates and internalizes with DRMs in cav-1–deficient cells. Cav-1KO cells were incubated with SV40 for 30 min at 37°C before cell lysis and extraction with 1% Triton X-100 at 4°C. Samples were floated in a linear sucrose gradient, and fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted against SV40.

The detergent resistance of cell-associated SV40 was confirmed by flotation in sucrose gradients after Triton X-100 solubilization of cav-1KO cells (Brown and Rose, 1992). When the gradient fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and to blotting with antibodies against VP1, the major SV40 coat protein, it was found that the virus had floated to a density of 1.068–1.090 g/cm3 (Fig. 5 B).

The results indicated that soon after binding to the plasma membrane, SV40 associated with detergent-resistant membrane domains. It was then internalized in association with them, and remained associated in the intermediate organelles and beyond.

Microtubule-dependent transport to the ER

The cytosolic, AF488-SV40-loaded organelles became more dynamic when viewed 2–3.5 h after virus uptake (Video 3). Virus-filled protrusions and tubules formed on their surface, some of these dissociated, giving rise to vesicles and tubular carriers that could be seen to move along linear pathways through the cytoplasm (Fig. 6 A and Video 4). The speed of movement of the vesicles was 0.143 ± 0.03 μm/s. When the cells were transfected with YFP-α-tubulin, and viewed live by confocal microscopy, it could be seen that the vesicles moved along microtubules (Videos 3 and 4). When cells were treated with nocodazole to disassemble the microtubules, AF594-SV40 was internalized normally but accumulated in cytoplasmic organelles that did not undergo surface changes, and did not support further vesicle traffic (Fig. 6 B and Video 5, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). The organelles in which the virus accumulated were larger than the intermediate organelles in control cells (1.5–2 μm in diameter compared with 0.5 μm). They were often round and clustered in the perinuclear cytoplasm.

Figure 6.

Endocytosis of SV40 into cav-1–deficient cells results in the accumulation of virus in cytosolic organelles. Cav-1KO cells were transfected with YFP-α-tubulin and incubated with AF594-SV40 for the indicated times. Before virus addition, cells had either been treated with nocodazole (B) or left untreated (A). Movies were recorded by confocal live microscopy of which a series of frames is shown. In nocodazole-treated cells, virus accumulated in caveosome-like organelles, which remained stationary. In A, a series of frames of untreated cells shows the formation of virus-containing transport vesicles from a larger cytosolic organelle. Bars, 5 μm.

Like in caveolin-containing cells, a large fraction of the viruses slowly found their way to the ER where they colocalized with syntaxin 17, a smooth ER marker (Steegmaier et al., 2000; Fig.7 A and Fig. S5, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). Colocalization with syntaxin 17 was obvious after 8 h, and extensive after 16 h. Some vesicles also stained positive for the ER markers calnexin (Fig. 7 A) and protein disulfide isomerase (Fig. S5). The increase in overlap with syntaxin 17 with time was probably due to increased synthesis of this marker protein induced by the virus. This was visible as increased syntaxin 17 immunofluorescence from 8 to 16 h, and it correlated with the expansion of the smooth ER observed by EM. No significant overlap with the Golgi markers mannosidase II (Fig. 7 A) and membrin (Fig. S5) was observed at any time. Thin section electron microscopy of cav-1KO cells showed accumulation of virus particles in large reticular networks of the smooth ER (Fig. 7 B). Similar SV40-induced expansions of the smooth ER arising after prolonged incubation with SV40 were previously described in CV-1 cells (Kartenbeck et al., 1989).

Figure 7.

18 h after internalization, SV40 accumulates in the smooth ER. (A) Cav-1KO cells were incubated with AF594-SV40, fixed after 18 h, stained in indirect immunofluorescence with a Golgi marker (ManII, mannosidase II), an ER marker (CNX, Calnexin), and a marker for the smooth ER (Syn17, syntaxin 17), and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Histograms show colocalization of SV40 with the respective markers over time. Values are given as the mean ± SD. Bars, 10 μm. (B) Thin section electron micrographs of cav-1KO cells infected with SV40 for 18 h showing virus accumulations in tubulo-reticular out-growths of the smooth ER.

In summary, we found that microtubules were not required for internalization or initial targeting of incoming virus-carrying vesicles to the intermediate organelle. However, they were essential for the formation of transport vesicles in these organelles, and for the transport of SV40 to the ER. If present in large numbers, the viruses induced expansion of the smooth ER network.

Effects of cav-1 expression

When expressed in cells that lack it, cav-1 induces the formation of caveolae (Fra et al., 1995). Therefore, it was of interest to determine what would happen to SV40 entry and infection when cav-1 was expressed in cav-1KO cells. To be able to visualize the caveolae and caveosomes in live cells, we used cav-1 tagged with fluorescent protein at the COOH terminus. We have previously shown that tagged caveolin, when expressed at moderate levels, colocalizes with cav-1 without compromising caveolar function (Pelkmans et al., 2001). Caveolar dynamics can be normally activated by phosphatase inhibitors and SV40 (unpublished data). Furthermore, cycles of internalization and fusion of caveolae with the plasma membrane are observed by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (unpublished data). Accordingly, we found that cav-1-mRFP was distributed in a pattern similar to that observed in most cav-1–positive cells; in addition to numerous small spots on the cell surface, there was cav-1-mRFP in cytoplasmic organelles resembling caveosomes. When exposed to SV40, the cells expressing cav-1-mRFP were infected at the same level of efficiency as cells transfected with mRFP alone.

When measured 10 min after warming, 1 out of 10 of incoming AF488-SV40 colocalized with cav-1-mRFP in cav-1–expressing cav-1KO cells (Fig. 8 A, a and c; and Video 6, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). In the video recordings, we observed immobile virus particles on the cell surface, some colocalizing with cav-1-mRFP, others not. In addition, there were particles that disappeared from the membrane presumably by endocytosis. Some of these were associated with cav-1-mRFP (Fig. 8 B). In the cytoplasm, overlap was seen in small, mobile vesicles (Fig. 8 A, a, arrowheads), and increasingly with time in larger periplasmic structures that resembled caveosomes in localization, motility, size, and shape. That the fraction of viruses that colocalized with cav-1-mRFP increased to more than 57% at 70 min (Fig. 8 A, b and c; and Video 7, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1) was due to their localization in these caveosomes. Confocal live microscopy confirmed that after internalization the viruses entered cav-1–positive organelles resembling caveosomes. We concluded that expression of cav-1-mRFP resulted in the formation of cell surface caveolae and caveosomes, that the viruses used both cav-1–containing and caveolin-free primary endocytic vesicles, and that the majority of viruses were transported to cav-1–containing intracellular organelles comparable to caveosomes.

Figure 8.

Cav-1 retransfection shifts the endocytic process back to caveosomes. (A) Confocal fluorescence microscopy of live cav-1KO and cav-1WT cells retransfected with cav-1-mRFP and infected with AF488-SV40. 10 min after warming (a and d), only a portion of AF488-SV40 colocalized with cav-1-mRFP (arrowheads) as quantified in panels c and f. In both cell types, viruses merged with caveosomes (b and e) at later time points. Values are given as the mean ± SD. Bars, 10 μm. (B) Series of frames taken from Video 6. Arrowheads point toward viruses that are subsequently internalized as shown by the dotted circle in the last frame. (arrow) Note that this particle colocalizes with cav-1 and was there in the previous frames. Bars, 5 μm.

Also, in cav-1WT cells expressing cav-1-mRFP, only a small fraction of virus particles colocalized initially with cav-1-mRFP (Fig. 8 A, d and f). With time, the fraction again increased as the viruses reached the caveosomes. Consistent with the slower endocytosis (Fig. 1 D), the increase in colocalization was less rapid than on the corresponding cav-1KO cells. (Fig. 8 A, f). Delivery of individual virus particles in cav-1–negative carriers to caveosomes could be observed by video microscopy (Fig. 8 A, e; and Video 8, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1). Thus, it was clear that both cav-1WT and cav-1KO cells possessed a cav-1–independent pathway that was available for virus endocytosis and was actively used by the virus as an alternative to caveolar endocytosis.

Discussion

It is apparent that SV40 can enter and infect cells by multiple pathways. One is the previously described pathway that involves cell surface caveolae (Parton and Lindsay, 1999; Norkin, 2001; Pelkmans et al., 2001, 2002) and one described here that is independent of caveolae and cav-1. In cav-1–containing cells, such as mouse embryonic lung fibroblasts, the two pathways seem to coexist and complement each other. Both pathways are strictly cholesterol dependent, and endocytic vesicle formation is in both cases triggered by virus-induced signals that involve activation of tyrosine kinases. The viruses are internalized in small, tight fitting endocytic vesicles that look and behave similarly whether they contain caveolin or not. They deliver the viruses to pH-neutral, intermediate organelles distributed throughout the cytoplasm. In caveolin-containing cells, these organelles are the previously described caveosomes (Pelkmans et al., 2001). In caveolin-free cells, the corresponding organelles are devoid of caveolar domains, but resemble caveosomes in their over-all distribution, their neutral lumenal pH, their lack of endosomal markers and ligands, and their activation upon SV40 internalization. In fact, the part of the pathway that involves caveosome activation and microtubule-mediated transport of vesicles to the smooth ER appears identical for both modes of entry.

In this work, we have characterized the caveolin-independent process by following SV40 entry and infection in cells devoid of caveolae. We found that internalization and infection were cholesterol dependent but independent of clathrin, dynamin II, and ARF6. Although distinguished by faster kinetics, cav-1–independent internalization resembled cav-1–mediated uptake in many of its over-all characteristics. The low level of fluid phase uptake and the inhibition by genistein indicated that internalization did not occur by a continuous but rather by a transient virus-activated process. Clearly, both endocytic processes fell into the category of mechanisms triggered by the cargo and involving a local signal.

To induce internalization in cav-1KO cells, the viruses had to associate with cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich lipid microdomains (i.e., lipid rafts). We found that the viruses were rapidly included in a detergent-resistant membrane fraction in which they remained during the rest of the entry process. The viruses either entered preexisting lipid rafts immediately after attachment, or, more likely, induced the formation of such domains by multivalent association with ganglioside molecules in the membrane. When clustered, GM1 is known to partition effectively into lipid rafts and to be trapped in caveolae (Parton, 1994).

Electron microscopy of cells devoid of caveolae showed that the SV40 particles were internalized via small plasma membrane pits and vesicles devoid of visible coats. The viruses were transported to pH-neutral organelles that resembled caveosomes except that they did not contain cav-1 or -2. Judging by their detergent insolubility, they were rich in raft lipids.

2 to 3 h after arrival of the viruses, live cell microscopy showed that the intermediate compartments became much more dynamic, and virus-containing transport vesicles and tubular carriers were formed. The generation of such transport vesicles, and the propagation of their movement from the intermediate organelle to the ER, was microtubule dependent and essential for infection. The virus particles later accumulated in tubular networks of the smooth ER. As a consequence of virus internalization, the networks grew in size and complexity. The accumulation of viruses induced increased expression of syntaxin 17, a smooth ER marker.

Whereas SV40 uptake in CV-1 and cav-1WT cells shows a t 1/2 of ∼100 min (Fig. 1 D; Pelkmans et al., 2002), initial uptake in cav-1KO cells had a t 1/2 of only 20 min. Thus, the kinetics of uptake was clearly faster in cells devoid of cav-1. Nabi and Le (2003) have proposed that caveolar and caveolin-independent processes constitute a common endocytosis system in which the role of the caveolae is to slow down endocytosis by stabilizing lipid rafts. In other words, although there is no doubt that caveolae themselves can internalize if properly activated, their main function in endocytosis may be to suppress rapid internalization of lipid rafts and raft-ligands. Although internalization of a major portion of SV40 was caveolae independent in cav-1WT cells, the kinetics of uptake were comparable to caveolar endocytosis in CV-1 cells. This result may be explained by sequestration of lipid microdomains into nonactivated caveolae, slowing down virus internalization by the faster alternative pathway.

Another significant difference between CV-1 cells (Pelkmans et al., 2002) and HuH7, cav-1WT, and cav-1KO cells was the inability of the GTPase-deficient mutant of dynamin II to reduce SV40 endocytosis and infection. One possible reason why dynamin II might be dispensable during SV40 entry into cells devoid of caveolae is that alternative cellular factors are used to form these vesicles. There is already evidence that endocytic pathways do not all rely on dynamin II. The dynamin-independent pathways reported include an ARF6-dependent process that internalizes not only non-raft proteins such as Class I MHC antigens but also some raft-associated proteins such as CD59 from the cell surface to endosomes (Arnaoutova et al., 2003; Naslavsky et al., 2003). The internalization of nonclustered GPI-anchored proteins to endosomes has also been reported to be dynamin II independent, but, in contrast to SV40 endocytosis, it is ARF6 dependent (Sabharanjak et al., 2002; Naslavsky et al., 2004). Moreover, polyomavirus has been reported to enter NIH-3T3 cells by a pathway that is dynamin I, clathrin, and cav-1 independent, but this pathway was not affected by cholesterol depletion (Gilbert and Benjamin, 2000).

The presence of two distinct mechanisms for SV40 endocytosis raises several questions of general nature. How many clathrin-independent mechanisms and pathways are there? To what extent do they overlap mechanistically and functionally? What is their cargo and how is it sorted and distributed intracellularly?

In trying to answer these questions, it is clear from our results and data from other systems that there are multiple cholesterol-dependent and clathrin- and cav-1–independent mechanisms. Several reports describe a rapid, caveolin-independent, but dynamin-dependent pathway involved in the formation of small, noncoated vesicles at the plasma membrane (Benlimame et al., 1998; Dautry-Varsat, 2000; Le et al., 2002; Nabi and Le, 2003; Nichols, 2003; Parton and Richards, 2003). In cells that have caveolae, this pathway coexists with the caveolar pathway, and the two have overlapping functions. In cells that do not have caveolae, the same dynamin-dependent pathway may at least in part replace caveolar endocytosis functionally (Nabi and Le, 2003). Interleukin-2 and cholera toxin are internalized by this mechanism in Caco-2 cells, lymphocytes, and Jurkat lymphoma cells that all lack caveolae and in Cos-7 cells where cav-1 expression was reduced with RNAi (Lamaze et al., 2001; Nichols, 2002). Autocrine motility factor is similarly internalized in transformed NIH-3T3 cells that contain little caveolin and few surface caveolae (Benlimame et al., 1998; Le et al., 2002).

The functional redundancy in cholesterol-dependent endocytosis revealed by SV40 entry into cells devoid of caveolae may help to explain why cav-1KO mice in the genetic background used here survive and display relatively minor physiological defects (Drab et al., 2001; Razani et al., 2002). Many processes thought to depend on caveolae, such as transcytosis in endothelia, cholesterol homeostasis, and the organization of lipid rafts, are essentially unimpaired in these mice (Kurzchalia and Parton, 1999; Simons and Ikonen, 2000; Simons and Toomre, 2000). It is possible that caveolar functions in the KO mice are taken over by caveolin-independent pathways such as the one used by SV40 in the cav-1KO cells derived from these mice. That alternative pathways may be up-regulated when cav-1 is lost, is suggested by knock-down experiments using iRNA that indicate that rapid depletion (<24 h) of cav-1 mRNA reduces SV40 infection and is toxic to cells in contrast to slower reduction, in which case alternative pathways may have more time to be induced (unpublished data).

It is clear that cells have multiple, parallel mechanisms and pathways for internalizing lipid raft components and associated molecules. These participate in the regulation of the plasma membrane composition by selective sequestration of specific membrane constituents and ligands associated with them. The various caveolae/raft pathways are tyrosine kinase activated, pH neutral, and they largely by-pass endosomes and lysosomes. They are so similar in important respects that it is tempting to view them as variants of a common process. However, they differ in internalization rate, involvement of caveolae, and role of cytosolic proteins such as dynamin and actin. Moreover, different cell types seem to have distinct preferences in respect to mechanisms that they make use of. The main challenge will be to characterize the molecular mechanisms involved and to analyze these pathways using a variety of cellular systems and ligands. Viruses such as SV40 will also be valuable tools.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: rabbit anti–cav-1(N20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), mouse anti–cav-2 and mouse anti-EEA1 (Transduction Laboratories), mouse anti-PDI (StressGen Biotechnologies), mouse anti-membrin (StressGen Biotechnologies), rabbit anti-giantin (Covance), and mouse anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich). Antiserum against SV40 was described previously (Pelkmans et al., 2001). Antiserum against mannosidase II was provided by M. Farquhar (University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA); antiserum against syntaxin 17 was provided by M. Steegmaier (Stanford University, Stanford, CA); antibodies against calnexin are described by Hammond and Helenius (1994); antisera against viral large T-antigen were provided by G. Brandner (University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany). All fluorescently labeled ligands were obtained from Molecular Probes.

Cell culture and virus

Media and reagents for tissue culture were purchased from GIBCO BRL. CV-1, MDCK, and HuH7 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. Cav-1KO and cav-1WT cells are lung mouse fibroblasts described previously (Drab et al., 2001). All cells were grown in DME containing 10% serum, 1× antibiotics, and 1× Glutamax, and incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2. AF594-SFV was provided by A. Vonderheit (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland). SV40 was purified and labeled with fluorophores as described previously (Pelkmans et al., 2001).

Construction and expression of constructs

The construction of cav-1-GFP was described by Pelkmans et al. (2001), and cav-1-mRFP was constructed by exchanging GFP against mRFP. Dynamin II GFP (wt, K44A) constructs were obtained from M. McNiven (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Eps15 constructs were obtained from A. Benmerah and A. Dautry-Varsat (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) and ARF6 constructs were obtained from J. Donaldson (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), YFP-α-tubulin was obtained from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc. Cells were grown to 70–90% confluency on coverslips and transiently transfected with plasmid-DNA using superfect reagent (QIAGEN). Cells that showed relatively low levels of expression were used for analysis after 16–20 h.

Drug treatments

Cells were preincubated for 30–60 min at 37°C in DME complete containing 0.5–1 μM Latrunculin A (Molecular Probes), 100 μM genistein (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 μM nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich), 2.5 μg/ml BFA (Serva), or 10 μM amiloride (Sigma-Aldrich). Preincubation with 25 μg/ml nystatin (Sigma-Aldrich) plus 10 μg/ml progesterone (Sigma-Aldrich) was performed over night. The drugs were either present throughout the experiments or washed out 2 h after virus addition to show that the effects were reversible. Drug treatments did not result in a loss of cell viability.

Infection and internalization assays

Drug-treated cells or cells expressing XFP-tagged constructs were analyzed for infection with indirect immune fluorescence 20 h after virus addition using antibodies against SV40 large T-antigen. In three independent experiments, at least 500 cells each were counted for the expression of T-antigen in the nucleus. Data were expressed as percentage ± SD of untreated control cells. To quantitate SV40 internalization biochemically, we used the assays as described previously (Pelkmans et al., 2002).

Triton X-100 extraction, sucrose flotation, and fractionation

Per experiment, four confluent 10-cm dishes of cav-1KO cells were used. SV40 was allowed to internalize into cav-1KO cells for 30 min. Cells were scraped and resuspended in ice-cold MES buffer containing CLAP and PMSF. Cells were pelleted and lysed with 1% Triton X-100 in MES buffer containing protease inhibitors. Lysates were incubated on ice for 20 min, mixed with an equal volume 80% (wt/vol) sucrose in MES containing 1% Triton X-100, and loaded underneath a linear 5–30% sucrose gradient. After centrifugation at 38,000 rpm for 17 h, fractions were collected from the bottom, precipitated, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted against SV40.

To follow the effect of Triton X-100 extraction by microscopy, cells on coverslips were incubated with AF488-SV40 and AF594-Tf for 1 h at 4°C, rinsed, and incubated in complete medium at 37°C for 10, 30, 60, or 240 min or treated immediately on ice. The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and either incubated in Triton X-100 (1% in Pipes) for 5 min on ice or mock treated. Control cells and Triton X-100–treated cells were washed three times with ice cold PBS, fixed, quenched, and examined as described in the section Microscopic techniques.

Western blotting

One confluent 10-cm dish of cells was lysed in Laemmli sample buffer. Equal amounts of protein were heated to 95°C for 10 min and run in a 12.5% SDS gel. Samples were immunoblotted against cav-1 and actin.

Microscopic techniques

For immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were grown to subconfluency on coverslips and incubated with fluorescently labeled SV40 diluted in R-Medium for the indicated times. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl, permeabilized with 0.05% saponin, and incubated with primary antibodies and the appropriate secondary antibodies. Coverslips were mounted with Immu Mount and examined using a confocal microscope (model LSM510; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) equipped with a 63 or 100×/1.40 plan-Apochromat objective.

For fluorescence microscopy, fluorescently labeled SV40 was bound to cav-1KO, cav-1WT, or HuH7 cells (or cells expressing a variety of XFP-tagged proteins) on ice. Internalization followed after shifting the temperature to 37°C for the indicated times. Endocytic structures were identified using appropriate fluorescent markers (Tf, dextran, SFV, and LY). In detail, cells were washed with R-Medium and fluorescently labeled SV40 was internalized for 1 h at 37°C before addition of 50 μg/ml AF488-Tf for 5 min or AF594-SFV for 40 min. In experiments using fluid phase markers, cells were incubated with AF594-SV40 plus 1μg/ml LY for 1 h, the inoculum was washed off, and the cells were further incubated with LY for 5 min. Cells on coverslips were either fixed and mounted or transferred to custom-built aluminium microscope-slide chambers (Workshop Biochemistry, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zürich) and imaged live in CO2-independent medium on a heated stage at 37°C using wide-field (model Axiovert; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) or confocal microscopy (model LSM510; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). Internalized FITC-labeled virus particles were distinguished from surface-bound particles by shifting medium to pH 4.0, completely quenching emitted light from extracellular FITC-SV40.

Videos were processed and analyzed using LSM 510 software package (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). Overlap between two channels in confocal images was quantified using MatLab 6.5. Image matrices of red and green channels were scaled to intensity values between 0 and 1 and multiplied, and a threshold was applied to define pixels that are positive in both channels. The overlap of virus signal with the respective marker is expressed as colocalizing pixels divided by total pixel of virus signal.

For thin section electron microscopy, cells were washed with R-Medium and incubated with SV40 at 37°C for 15 min, 2 h, or 18 h. Cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (0.05 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.2, 50 mM KCl, 1.25 mM MgCl2, and 1.25 mM CaCl2) for 30 min at RT followed by 1.5 h in 2% OsO4. Dehydration, embedding, and thin sectioning were performed as described previously (Kartenbeck et al., 1989).

Online supplemental material

A concise description of the data presented in each supplemental figure is introduced upon citation in the text. Online supplemental material (Figs. S1–S5 and Videos 1–8) is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200407113/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank all laboratory members for discussions and suggestions throughout this work. We thank Marek Drab for help in early stages of the project. We also thank K. Quirin for providing the code for quantitation of overlap of confocal images and Uta Haselmann-Weiss for indispensable help in electron microscopy.

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) and Swiss National Science Foundation.

Abbreviations used in this paper: AF, Alexafluor; BFA, Brefeldin A; cav-1, caveolin-1; cav-1WT, cav-1 wild-type; HuH7, human hepatoma 7; KO, knockout; LY, Lucifer yellow; MOI, multiplicity of infection; SFV, Semliki Forest virus; SV40, simian virus 40; Tf, transferrin.

References

- Anderson, H.A., Y. Chen, and L.C. Norkin. 1996. Bound simian virus 40 translocates to caveolin-enriched membrane domains, and its entry is inhibited by drugs that selectively disrupt caveolae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 7:1825–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.G. 1998. The caveolae membrane system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:199–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutova, I., C.L. Jackson, O.S. Al-Awar, J.G. Donaldson, and Y.P. Loh. 2003. Recycling of Raft-associated prohormone sorting receptor carboxypeptidase E requires interaction with ARF6. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:4448–4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlimame, N., P.U. Le, and I.R. Nabi. 1998. Localization of autocrine motility factor receptor to caveolae and clathrin-independent internalization of its ligand to smooth endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell. 9:1773–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benmerah, A., M. Bayrou, N. Cerf-Bensussan, and A. Dautry-Varsat. 1999. Inhibition of clathrin-coated pit assembly by an Eps15 mutant. J. Cell Sci. 112:1303–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.A., and J.K. Rose. 1992. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 68:533–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner, S.D., and S.L. Schmid. 2003. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 422:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautry-Varsat, A. 2000. Clathrin-independent endocytosis. Endocytosis. M. Marsh, editor. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 26–57.

- De Camilli, P., K. Takei, and P.S. McPherson. 1995. The function of dynamin in endocytosis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 5:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drab, M., P. Verkade, M. Elger, M. Kasper, M. Lohn, B. Lauterbach, J. Menne, C. Lindschau, F. Mende, F.C. Luft, et al. 2001. Loss of caveolae, vascular dysfunction, and pulmonary defects in caveolin-1 gene-disrupted mice. Science. 293:2449–2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish, K.N., S.L. Schmid, and H. Damke. 2000. Evidence that dynamin-2 functions as a signal-transducing GTPase. J. Cell Biol. 150:145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fra, A.M., E. Williamson, K. Simons, and R.G. Parton. 1995. De novo formation of caveolae in lymphocytes by expression of VIP21-caveolin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:8655–8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, J.M., and T.L. Benjamin. 2000. Early steps of polyomavirus entry into cells. J. Virol. 74:8582–8588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, C., and A. Helenius. 1994. Quality control in the secretory pathway: retention of a misfolded viral membrane glycoprotein involves cycling between the ER, intermediate compartment, and Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 126:41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes, L., and C. Lamaze. 2002. Clathrin-dependent or not: is it still the question? Traffic. 3:443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartenbeck, J., H. Stukenbrok, and A. Helenius. 1989. Endocytosis of simian virus 40 into the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 109:2721–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasamatsu, H., and A. Nakanishi. 1998. How do animal DNA viruses get to the nucleus? Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:627–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzchalia, T.V., and R.G. Parton. 1999. Membrane microdomains and caveolae. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaze, C., A. Dujeancourt, T. Baba, C.G. Lo, A. Benmerah, and A. Dautry-Varsat. 2001. Interleukin 2 receptors and detergent-resistant membrane domains define a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Mol. Cell. 7:661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le, P.U., G. Guay, Y. Altschuler, and I.R. Nabi. 2002. Caveolin-1 is a negative regulator of caveolae-mediated endocytosis to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 277:3371–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, M., and A. Helenius. 1989. Virus entry into animal cells. Adv. Virus Res. 36:107–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, I.R., and P.U. Le. 2003. Caveolae/raft-dependent endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 161:673–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslavsky, N., R. Weigert, and J.G. Donaldson. 2003. Convergence of non-clathrin- and clathrin-derived endosomes involves Arf6 inactivation and changes in phosphoinositides. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:417–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslavsky, N., R. Weigert, and J.G. Donaldson. 2004. Characterization of a nonclathrin endocytic pathway: membrane cargo and lipid requirements. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:3542–3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, B. 2003. Caveosomes and endocytosis of lipid rafts. J. Cell Sci. 116:4707–4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, B.J. 2002. A distinct class of endosome mediates clathrin-independent endocytosis to the Golgi complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norkin, L.C. 2001. Caveolae in the uptake and targeting of infectious agents and secreted toxins. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 49:301–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, P., D.P. McIntosh, and J.E. Schnitzer. 1998. Dynamin at the neck of caveolae mediates their budding to form transport vesicles by GTP-driven fission from the plasma membrane of endothelium. J. Cell Biol. 141:101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolini, I., M. Sargiacomo, F. Galbiati, G. Rizzo, F. Grignani, J.A. Engelman, T. Okamoto, T. Ikezu, P.E. Scherer, R. Mora, et al. 1999. Expression of caveolin-1 is required for the transport of caveolin-2 to the plasma membrane. Retention of caveolin-2 at the level of the golgi complex. J. Biol. Chem. 274:25718–25725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton, R.G. 1994. Ultrastructural localization of gangliosides; GM1 is concentrated in caveolae. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 42:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton, R.G., and M. Lindsay. 1999. Exploitation of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules and caveolae by simian virus 40. Immunol. Rev. 168:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton, R.G., and A.A. Richards. 2003. Lipid rafts and caveolae as portals for endocytosis: new insights and common mechanisms. Traffic. 4:724–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans, L., and A. Helenius. 2003. Insider information: what viruses tell us about endocytosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15:414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans, L., J. Kartenbeck, and A. Helenius. 2001. Caveolar endocytosis of simian virus 40 reveals a new two-step vesicular-transport pathway to the ER. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans, L., D. Puntener, and A. Helenius. 2002. Local actin polymerization and dynamin recruitment in SV40-induced internalization of caveolae. Science. 296:535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, P.J., A. Mironov Jr., D. Peretz, E. van Donselaar, E. Leclerc, S. Erpel, S.J. DeArmond, D.R. Burton, R.A. Williamson, M. Vey, and S.B. Prusiner. 2003. Trafficking of prion proteins through a caveolae-mediated endosomal pathway. J. Cell Biol. 162:703–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razani, B., T.P. Combs, X.B. Wang, P.G. Frank, D.S. Park, R.G. Russell, M. Li, B. Tang, L.A. Jelicks, P.E. Scherer, and M.P. Lisanti. 2002. Caveolin-1-deficient mice are lean, resistant to diet-induced obesity, and show hypertriglyceridemia with adipocyte abnormalities. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8635–8647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, K.G., J.E. Heuser, W.C. Donzell, Y.S. Ying, J.R. Glenney, and R.G. Anderson. 1992. Caveolin, a protein component of caveolae membrane coats. Cell. 68:673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabharanjak, S., P. Sharma, R.G. Parton, and S. Mayor. 2002. GPI-anchored proteins are delivered to recycling endosomes via a distinct cdc42-regulated, clathrin-independent pinocytic pathway. Dev. Cell. 2:411–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieczkarski, S.B., and G.R. Whittaker. 2002. Dissecting virus entry via endocytosis. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1535–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons, K., and E. Ikonen. 2000. How cells handle cholesterol. Science. 290:1721–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons, K., and D. Toomre. 2000. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegmaier, M., V. Oorschot, J. Klumperman, and R.H. Scheller. 2000. Syntaxin 17 is abundant in steroidogenic cells and implicated in smooth endoplasmic reticulum membrane dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:2719–2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, P., K. Roepstorff, M. Stahlhut, and B. van Deurs. 2002. Caveolae are highly immobile plasma membrane microdomains, which are not involved in constitutive endocytic trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:238–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainio, S., S. Heino, J.E. Mansson, P. Fredman, E. Kuismanen, O. Vaarala, and E. Ikonen. 2002. Dynamic association of human insulin receptor with lipid rafts in cells lacking caveolae. EMBO Rep. 3:95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.M., and M.P. Lisanti. 2004. The caveolin proteins. Genome Biol. 5:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]