Abstract

Schwann cells form basal laminae (BLs) containing laminin-2 (Ln-2; heterotrimer α2β1γ1) and Ln-8 (α4β1γ1). Loss of Ln-2 in humans and mice carrying α2-chain mutations prevents developing Schwann cells from fully defasciculating axons, resulting in partial amyelination. The principal pathogenic mechanism is thought to derive from structural defects in Schwann cell BLs, which Ln-2 scaffolds. However, we found loss of Ln-8 caused partial amyelination in mice without affecting BL structure or Ln-2 levels. Combined Ln-2/Ln-8 deficiency caused nearly complete amyelination, revealing Ln-2 and -8 together have a dominant role in defasciculation, and that Ln-8 promotes myelination without BLs. Transgenic Ln-10 (α5β1γ1) expression also promoted myelination without BL formation. Rather than BL structure, we found Ln-2 and -8 were specifically required for the increased perinatal Schwann cell proliferation that attends myelination. Purified Ln-2 and -8 directly enhanced in vitro Schwann cell proliferation in collaboration with autocrine factors, suggesting Lns control the onset of myelination by modulating responses to mitogens in vivo.

Introduction

Myelin increases the speed of neural conduction in thin axons. Defects in myelination cause debilitating loss of function in a variety of congenital and acquired neurological disorders. Mechanisms coordinating myelination in the peripheral nervous system are poorly understood, despite descriptions of cellular events (Martin and Webster, 1973; Webster et al., 1973) and the identification of molecular cues to developing Schwann cells (Mirsky et al., 2002). We show that two members of the laminin (Ln) family of glycoproteins act in concert to regulate the onset of myelination in peripheral nerves.

Peripheral myelination is a concerted process in which Schwann cell proliferation, axon defasciculation, and myelin assembly overlap (Webster, 1971; Martin and Webster, 1973; Webster et al., 1973; Stewart et al., 1993). Premyelinating Schwann cells cover fascicles of cotargeted axons. Their proliferation rate initially matches axonal growth, but increases during myelination to supply Schwann cells for individual axons, at perinatal ages in rodents. Progeny invade fascicles after longitudinal division, which increases Schwann cell density along subsets of axons. Invading cells often transiently ensheath several axons, but retract all but one process and myelinate a single axon. Recurrence of these events ultimately reduces fascicles to axons lacking promyelinating signals, which are defasciculated but remain unmyelinated by the final Schwann cell progeny. Webster described the progressive defasciculation and myelination of peripheral axons as radial sorting, and proposed that Schwann cell proliferation is intimately involved in the commitment of longitudinal cohorts to defasciculate and ensheath subjacent axons (Webster, 1971; Martin and Webster, 1973; Webster et al., 1973). Although neuregulins have been identified as key signals for Schwann cell proliferation (Garratt et al., 2000), molecular mechanisms that accelerate perinatal proliferation and propel radial sorting are not known.

The one factor known to have specific roles in radial sorting is Ln-2 (merosin), a major component of the Schwann cell surface basal lamina (BL). Lns comprise a family of αβγ heterotrimers. Loss of Ln-2 through mutations in the α2 chain causes a complex neuromuscular disease including peripheral dysmyelination. In the most studied dy and dy2J strains of Ln α2 mutant mice, peripheral nerves contain bundles of unsheathed axons that resemble embryonic fascicles (Bradley and Jenkison, 1973; Biscoe et al., 1974). This unique pattern of dysmyelination presumably represents incomplete radial sorting and has therefore been termed “amyelination.”

Mechanistic hypotheses for amyelination presume endoneurial BLs are necessary for Schwann cell motility and/or differentiation during rapid remodeling (Madrid et al., 1975; Bunge, 1993; Feltri et al., 2002; Chen and Strickland, 2003). Lns that self-polymerize, including Ln-2, are the key structural component of BLs (Yurchenco et al., 2004), and Ln-2–deficient Schwann cells form patchy, discontinuous BLs (Madrid et al., 1975). However, only spinal roots and cranial nerves are severely amyelinated in dy and dy2J mice; sciatic nerves are partially affected and brachial nerves are nearly normal (Bradley and Jenkison, 1975; Stirling, 1975; Weinberg et al., 1975). One possibility is that BL structure and Ln have limited roles in radial sorting, only critical in large nerves. Alternatively, loss of Ln-2 may be partially compensated by isoforms containing the α1, α4, and α5 chains. Ln α1 is absent in normal nerves, but is expressed in dy2J sciatic nerves; lack of α1 expression in dy2J spinal roots may account for severe amyelination there (Previtali et al., 2003b). Ln α5 is selectively expressed in roots (Nakagawa et al., 2001), which could interfere with α1-Ln heterotrimer assembly in dy2J. Ln α4 is normally low in mature nerves, but is up-regulated in developing nerves and α2-deficient nerves (Patton et al., 1997, 1999; Nakagawa et al., 2001). Targeted deletion of the Ln γ1 chain causes more widespread peripheral dysmyelination than occurs in dy mice, consistent with roles for multiple isoforms (Chen and Strickland, 2003). Here, we address independent and combined roles of Lns containing the α2, α4, and α5 chains.

Results

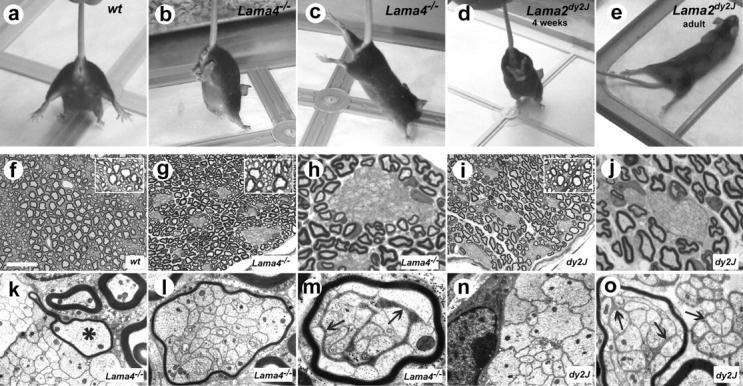

Neuromuscular dysfunction and peripheral neuropathy

When lifted by the tail, Ln α4-deficient mice (Lama4 −/−) retracted hindlimbs toward the body, with toes clenched (Fig. 1 b). In contrast, normal and heterozygous Lama4 +/− littermates extended limbs downward, potentially minimizing fall injuries (Fig. 1 a). Lama4 −/− hindlimb retractions often progressed to rigid rearward extension (Fig. 1 c), but ceased upon landing. Forelimbs were unaffected. Similar suspension-induced hindlimb retraction was observed in juvenile Lama2 dy2J (dy2J) mice (Fig. 1 d), before permanent contractures (Fig. 1 e). The overlap in dysfunction suggested Lama4 −/− might possess an abbreviated form of Ln α2-deficient neuromuscular disease.

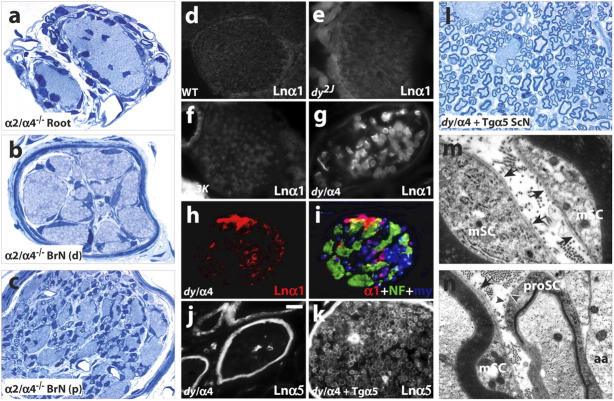

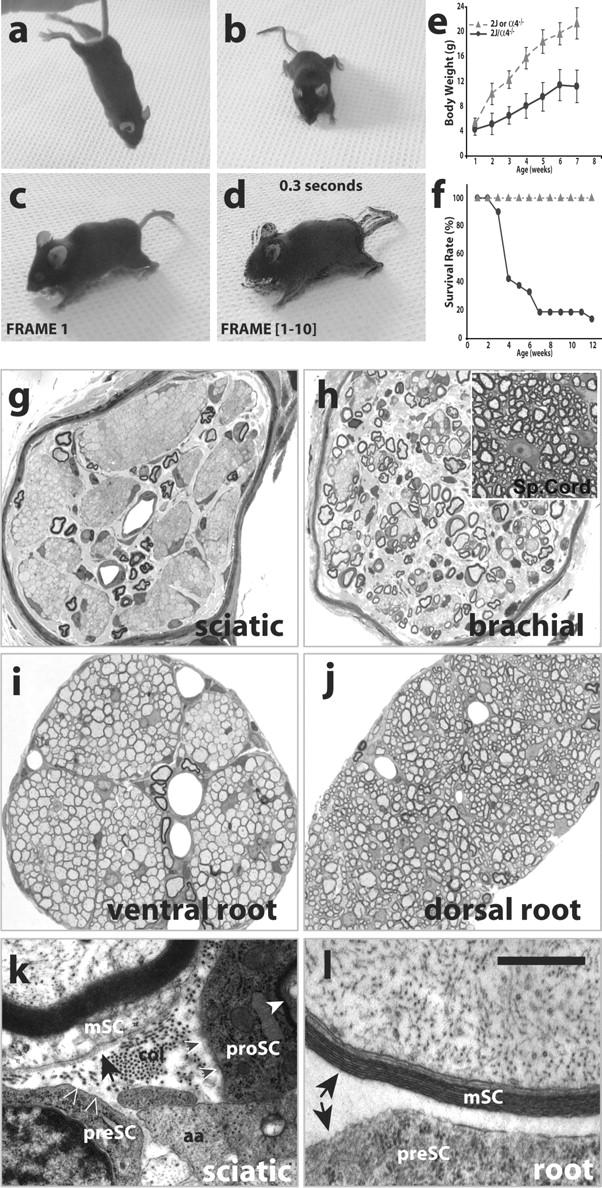

Figure 1.

Amyelinating peripheral neuropathies in Lama4 −/− and dy2J mice. (a–d) Overlapping postural defects. When suspended, wild type (a) mice extend limbs downward, whereas Lama4 −/− mice retract and then extend hindlimbs backward (b and c). dy2J mice retract hindlimbs at juvenile ages (d, 4 wk), before the onset of permanent contractures (e, 3 mo). (f–j) Toluidine blue–stained resin sections of adult control (f), Lama4 −/− (g and h), and dy2J (i and j) sciatic nerves at low (f, g, and i) and high (h and j) magnification. Bundles of unsheathed axons are present in mutants, but not controls. (k–o) Electron micrographs show most bundles lack intervening Schwann cell processes. Some Lama4 −/− Schwann cells along large bundles establish promyelinating relations with single axons (k, asterisk), but usually myelinate small bundles altogether (l and m; Table I). Some polyaxonal myelination included intervening Schwann cell processes (m, arrows), possibly from adjacent cells along the nerve. In dy2J, polyaxonal myelination was rare (o, left), but large rafts of partially defasciculated, unmyelinated, mixed caliber fibers were common (o, right). Bar in f, 38 μm (f, g, and i); 15 μm (h and j); 3 μm (k, l, n, and o); 1.8 μm (m).

Ln α2 and α4 are coexpressed in developing muscles and nerves (Patton et al., 1997). As Lama4 −/− has no apparent myopathy and limited defects at neuromuscular junctions (Patton et al., 2001), we assessed peripheral myelination (Fig. 1, f–j). Normal nerves are composed of large myelinated axons and thin axons ensheathed by nonmyelinating Schwann cells. In addition to properly myelinated axons, Lama4 −/− sciatic nerves contained bundles of axons lacking ensheathment. EM confirmed such bundles were largely devoid of Schwann cell processes, and found no solitary naked axons. Premyelinating Schwann cells associated with the large bundles occasionally extended processes between axons or established a promyelinating relationship with a solitary axon (Fig. 1 k; unpublished data). However, most small bundles were polyaxonally myelinated (Fig. 1, l and m; Table I). Defects in Lama4 −/− were remarkably similar to amyelination described in dy and dy2J mice (Bradley and Jenkison, 1973; Biscoe et al., 1974; Weinberg et al., 1975; Okada et al., 1977) (Fig. 1, i and j). Indeed, quantitative analysis of the tibial branch revealed no significant differences between dy2J and Lama4 −/− in the number of amyelinated axons or their distribution in bundles (Table I). In both dy2J and Lama4 −/−, bundles contained mixed caliber axons. The number of larger axons (minimum diameter ≥ 2 μm) in Lama4 −/− bundles (average ± SEM: 292 ± 86/tibial nerve; n = 4) was similar to deficits in myelinated axons. Isolated axons were well myelinated and degenerating myelin figures were absent in both mutants. Finally, although we could not rule out limited central nervous system (CNS) defects in Lama4 −/−, we found no CNS amyelination in either mutant (Fig. 1, g and i; insets). Thus, independent genetic lesions in Ln α2 and α4 produce essentially similar amyelinating peripheral neuropathies.

Table I.

Amyelination in nerves and roots of Ln α2- and α4-deficient mice

| Genotype | Wild type | Lama4 − /− | Lama2dy2J |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tibial N. (n) | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Myelinated axons | 2226 ± 16 | 1697 ± 49* | 1258 ± 16* |

| Amyelinated axons | 0 | 2043 ± 458 | 2380 ± 600 |

| Bundles | 0 | 31 ± 4 | 31.0 ± 1.4 |

| Nonmyelinated bundles | NA | 17 ± 3** | 28.5 ± 0.7** |

| “myelinated” bundles | NA | 14 ± 2** | 2.5 ± 2.1** |

| Axons/bundle (total) | NA | 67 ± 16 | 77 ± 22 |

| Axons/nonmyelinated bundlea | NA | 105 ± 9 | 80 ± 9 |

| Axons/myelinated bundlea | NA | 18 ± 1 | 16 ± 5 |

| V. root (n) | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Myelinated axons | 760 ± 53 | 698 ± 56** | 32 ± 7** |

| Amyelinated axons | 0 | 21 ± 6** | 502 ± 42** |

| Bundles | 0 | 2 ± 1 | 10 ± 2* |

| Axons/bundle (total) | NA | 11 ± 1** | 49 ± 21** |

Values represent mean ± SEM across nerves. *, Different from wild-type value; P < 0.05. **, Difference between mutant values; P < 0.01.

Errors represent pooled bundles of all nerves.

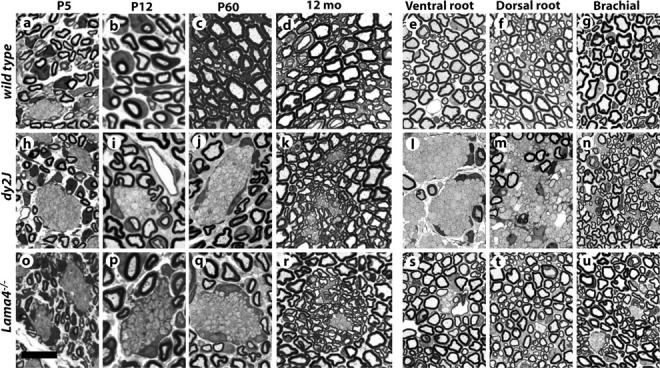

Similarity between Ln α2- and α4-deficient neuropathy included origin and progression (Fig. 2). Most axons in wild-type, Lama2 +/dy2J, and Lama4 +/− sciatic nerves were sorted by P5 and myelinated by P12. In dy2J and Lama4 −/−, axon fascicles persisted throughout postnatal development (Fig. 2, h–j and o–q). The proposition that axon bundles in dy strains arise through incomplete radial sorting (Bradley and Jenkison, 1973) is generally accepted, although lack of efficient methods to identify neonatal mutants prevented developmental studies. We confirm that amyelinated bundles are remnants of embryonic fascicles in both α2- and α4-deficient mice. Amyelination has also been thought permanent (Bradley and Jenkison, 1973). However, we found only a few, small axon bundles remaining in year-old dy2J and Lama4 −/− sciatic nerves, each surrounded by lightly myelinated axons (Fig. 2, k and r). As axonopathy was not observed among amyelinated axons, bundles likely erode slowly through continued myelination at their edges (Fig. 1 k). Regardless, α2- and α4-deficient neuropathies did not diverge between onset and old age despite considerable remodeling.

Figure 2.

Origin and distribution of amyelination in dy2J and Lama4 −/− mice. Toluidine blue stained sections from wild-type (a–g), dy2J (h–n), and Lama4 −/− (o–u) sciatic nerves at indicated postnatal age, or spinal roots and brachial nerves from 6–9-wk adults. Axon fascicles are sorted by P12 in controls, but persist as amyelinated bundles in mutants. Bundles in year-old mutants are small and surrounded by lightly myelinated fibers (k and r). Spinal roots are severely amyelinated in dy2J (l and m) but not Lama4 −/− (s and t). Brachial nerves contain few amyelinated axons in either mutant (n and u). Bar in o, 14 μm (a, h, and o); 8 μm (b, i, and p); 16 μm (c, d, j, k, q, and r); 20 μm (e–g, l–n, and s–u).

Further comparison revealed two significant differences. First, amyelination is especially severe in dy2J spinal roots, but was nearly absent from roots in Lama4 −/− (Fig. 2, l, m, s, and t; Table I). Roots are less affected than distal nerves in Lama4 −/−. We infer amyelination primarily reflects relative dependence on Ln isoforms, rather than nerve diameter or proximity to spinal origin. Sorting in roots depends strongly on Ln-2 and weakly on Ln-8; distal nerves rely more equally on both. Otherwise, amyelination was distributed similarly in Lama4 −/− and dy2J; forelimb and intercostal nerves were less affected than hindlimb (Fig. 2, n and u; unpublished data).

Second, polyaxonal myelination (Fig. 1, l, m, and o; Table I) was common in Lama4 −/− but rare in dy2J, consistent with previous observations in dy (Okada et al., 1977). Most small bundles (≤25 axons) in Lama4 −/− tibial nerves were “myelinated.” Conversely, dy2J nerves contained many islands of ensheathed-but-not-myelinated axons, which were rare in Lama4 −/− (Fig. 1 o, right). Superficially similar to Remak bundles, islands were less condensed, more numerous, and included mixed caliber axons. They appear to be abnormal transitional structures, intermediate between amyelinated bundles and properly myelinated axons, which preferentially appear in dy2J nerves when fascicles contain few axons. Thus, although Ln-2 and -8 both promote axon sorting, they have decidedly unequal roles in roots, and dissimilar roles in the transition from premyelinating to myelinating Schwann cell phenotype.

Redundancy and compensation in the BL

To ask if Ln-2 and -8 independently incorporate into endoneurial BLs, we stained cryostat sections of normal and mutant sciatic nerves with Ln chain–specific antibodies. In normal nerves, Ln α4 was coconcentrated with the α2, β1, and γ1 chains at ab-axonal Schwann cell surfaces; none were detected at axonal surfaces (Fig. 3, d, e, m, and n; unpublished data). Detection of α4 varied considerably with antibody, but endoneurial BLs stained weakly compared with perineurium, as shown previously (Patton et al., 1997; Nakagawa et al., 2001). Loss of α4 did not affect staining for α2 at any postnatal age (Fig. 3 u; unpublished data). Similarly, α4 staining was not decreased in dy2J nerve; indeed, levels increased relative to controls, confirming previous results (Patton et al., 1997, 1999; Nakagawa et al., 2001) with additional reagents. In addition, staining for entactin, perlecan, agrin, and collagen IV was unaffected in either mutant (Fig. 3, g–i, p–r, and y–a′; unpublished data). Thus, amyelination-inducing mutations in α2 and α4 do not act by inhibiting expression of their counterpart specifically, or disrupting the molecular composition of endoneurial BLs generally. We found no morphological or histological defects in double-heterozygous Lama2 dy2J/+ ;Lama4 +/− offspring (not depicted). Therefore, Ln-2 and Ln-8 each contribute a distinct activity necessary to complete radial sorting.

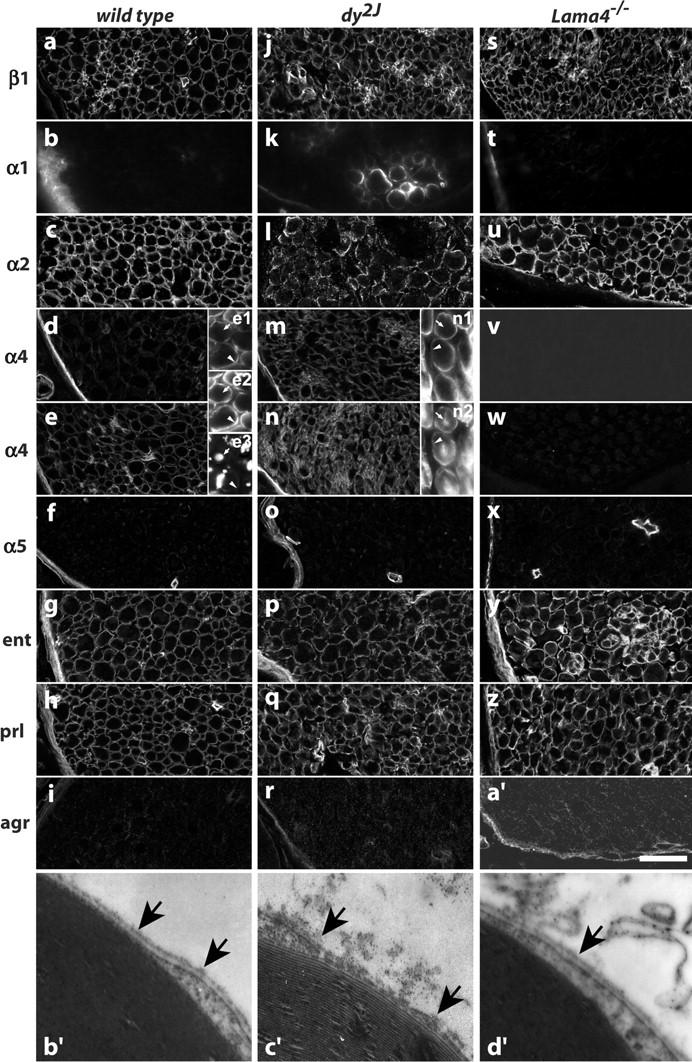

Figure 3.

Loss of Ln α4 does not otherwise affect endoneurial BL composition or structure. (a–a′) Medial sciatic nerve sections from adult (6–9 wk) wild-type (a–i), dy2J (j–r), and Lama4 −/− (s–a′) mice were stained with antibodies to the Ln β1 (a, j, and s), α1 (mAb 198; b, k, and t), α2 (c, l, and u), α4 (mAb 1G5: d, m, and v; polyclonal: e, n, and w), and α5 (f, o, and x) chains, and to entactin (g, p, and y), perlecan (h, q, and z), and agrin (i, r, and a′). Double-labeled sections show α4 (e1, n1) coconcentrated with α2 (e2) at ab-axonal surfaces (arrowheads) of Schwann cells (S100 in n2); axons are stained for neurofilaments (e3; arrow). Changes in dy2J include degraded staining for α2, variable up-regulation of α1, and uniform up-regulation of α4. Ln α4 deficiency does not alter distribution of other Lns or BL components. (b′–d′) Electron micrographs of endoneurial BLs (arrows) in mature control (b′), dy2J (c′), and Lama4 −/− nerves. BL integrity is disrupted by mutations in Ln α2 but not α4. Bar in a′, 30 μm in a–a′; 0.45 μm in b′–d′.

Next, we asked if myelination achieved in dy2J and Lama4 −/− reflects partial compensation between Ln-2 and -8, by generating double mutant dy2J/α4null mice (see Materials and methods). dy2J/α4null mice had normal birthweight, fed actively, and responded to stimuli, but were dyskinetic by P14. Adults had splayed stance and strong tremor, moved haltingly, retracted all limbs when suspended, were 50% smaller than normal littermates, and rarely survived 3 mo (Fig. 4, a–f). Peripheral nerves were translucent, rather than the opaque white of myelinated regions of the nervous system. Histological sections showed nearly all forelimb and hindlimb axons were concentrated in large amyelinated bundles (Fig. 4, g and h), dramatically exceeding defects in the parent dy2J and Lama4 −/− strains. Premyelinating Schwann cells surrounded bundles, and a few isolated axons were well myelinated, demonstrating neural crest migration and proliferation of Schwann cell precursors was not prevented. CNS myelination appeared unimpaired (Fig. 4 h, inset), showing potential metabolic disorders in these mice do not, per se, prevent formation of myelin. Thus, Ln-2 and -8 act in concert to play a dominant role in the myelination of distal nerve, and each only partially compensates the other's deficiency.

Figure 4.

Severe neuropathy in dy2J/α4null double-mutant mice. (a–d) Adult dy2J/α4null mice (14 wk shown) retract fore and hind limbs when suspended, and have splayed stance and tremor. (c) Frame 1 of 0.3-s video; (d) all frames superimposed by “Difference” in Photoshop 6. (e and f) Growth and longevity of double mutants (circles) are decreased; triangles, littermate controls; values in e show average ± SEM. (g and h) Sciatic and brachial nerves are severely amyelinated in dy2J/α4null; CNS is well myelinated (h, inset). (i and j) Paradoxically, dy2J/α4null spinal roots are well sorted and lightly myelinated, a marked improvement from dy2J roots (compare with Fig. 2, l and m). (k and l) Myelinating Schwann cells (mSC) have BLs (arrows) in distal nerves, but not in roots. All premyelinating (preSC) and promyelinating (proSC) Schwann cells lack BLs. aa, amyelinated axon; col, collagen fibrils; white arrowhead, proSC myelin. Small black arrows in k indicate lack of BL on preSC and proSC surfaces. Bar in l is 100 μm in g–j; 1 μm in k and l.

Remarkably, however, spinal roots in dy2J/α4null mice were completely sorted. Compared with dy2J, the additional loss of Ln α4 strongly enhanced radial sorting in dy2J/α4null roots (Fig. 4, i and j; compare with Fig. 2, l and m). Paradoxically, Ln-8 promotes radial sorting in distal dy2J nerves but inhibits sorting in dy2J roots. To explain disparate results in root and distal nerve, we sought differences in Ln receptors and components of the endoneurial matrix that could modulate Schwann cell responses to Ln-2 or -8. We found no reliable differences in receptor components integrin α3, α6, β1, and β1D subunits, α-dystroglycan, β-dystroglycan, or β-sarcoglycan, between normal, dy2J, or Lama4 −/− mice (unpublished data), extending results in dy2J and dy3K (Nakagawa et al., 2001; Previtali et al., 2003a,b). Two matrix differences between sciatic nerves and roots are reported; both are Ln α chains. Ln α1, which is absent in normal endoneurium, is expressed in dy2J sciatic nerves, but not their roots (Previtali et al., 2003b). In contrast, Ln α5 is expressed in normal and α2-deficient roots, but not distal nerve (Nakagawa et al., 2001).

Several aspects of Ln α1 expression were inconsistent with roles in radial sorting. First, α1 expression and myelination were poorly correlated in adult dy2J (6–9 wk). α1 was undetectable on many myelinated fibers (Fig. 3 k), and was absent from any brachial or sciatic fibers in 4 of 8 dy2J mice. Several α1 antibodies, which strongly stained CNS pial surfaces included as controls, gave similar results. Second, we were unable to detect α1 in dy2J nerves before P14, when radial sorting has largely ended even in mutants (Fig. 5, d and e; unpublished data). Third, α1 was absent from partially myelinated nerves in Lama4 −/− (Fig. 3 t) and α2-null dy3K mice (Fig. 5 f). Fourth, levels of α1 were highest in severely amyelinated dy2J/α4null nerves (Fig. 5, g–i), indicating endogenous α1 expression is insufficient for radial sorting. As Ln-1 (α1β1γ1) is elsewhere implicated in BL assembly (Yurchenco et al., 2004), the heterogeneous expression of Ln α1 we observed in dy2J may account for the variable integrity of endoneurial BLs present (but not often acknowledged) in this strain. In dy2J/α4null nerves, α1 was predominantly associated with myelinated fibers (Fig. 5, h and i), many of which contained well-formed BLs (Fig. 4 k). Pre- and promyelinating dy2J/a4null Schwann cells lacked BLs (Fig. 4 k). Thus, Ln α1 may not promote radial sorting because α2-deficient Schwann cells express it after myelination.

Figure 5.

Roles for Ln α5, not α1, in dy2J myelination. (a–c) Amyelination in Lnα2/α4-DKO mice (P11 shown) includes spinal roots as well as distal nerve, revealing dy2J variant Ln-2 is required for sorting in dy2J/α4null roots. (d–i) Ln α1 is not detected in wild-type (d) or dy2J (e) sciatic nerves at juvenile ages (P8 shown), or adult dy3K (f). (g–l) In adult dy2J/α4null nerve, Ln α1 is detected on myelinated fibers but not amyelinated bundles (g–i), and Ln α5 is restricted to perineurium and capillaries. (k and l) In dy2J/α4null/+TgA5 nerve, Ln α5 is present in endoneurial BL, and radial sorting is greatly increased. BLs are present on myelinating (m) but not promyelinating (n) cells in dy2J/α4null/+TgA5. Labels as in Fig. 4; NF, neurofilaments (green); my, myelin autofluorescence (blue in i). d–n; tibial branch, medial sciatic nerve. Bar in j, 25 μm in a–c; 45 μm in d; 30 μm in e, f, j, and k; 18 μm in g; 25 μm in h and i; 15 μm in l; 0.38 μm in m and n.

Next, we asked if Ln α5 fosters radial sorting in dy2J/a4null nerve roots. Lama5 −/− mice die as embryos (Miner et al., 1998), before radial sorting. Therefore, we used a broadly expressed α5 transgene (TgA5) (Kikkawa et al., 2002) to ask if ectopic α5 expression would promote sorting and myelination in the distal portions of dy2J/α4null nerves. Although TgA5 did not increase levels of Ln α5 in wild-type or dy2J endoneurial BLs (unpublished data), possibly due to competition from endogenous α2 and α4 chains for heterotrimer assembly, α5 was readily detected in dy2J/α4null/TgA5 nerves (Fig. 5 k). α5 colocalized with the β1 and γ1 chains, and β2 was absent (not depicted), indicating ectopic expression of Ln-10 (α5β1γ1). Ln-10 expression was accompanied by suppression of tremor and dyskinesia, and a marked increase in sorting and myelination in distal nerves (Fig. 5, k and l; compare with Fig. 4 g). The results implicate Ln-10 in the sorting and myelination of axons in dy2J/a4null roots, but do not establish whether Ln-10 acts autonomously or depends on the truncated isoform of Ln-2 produced from the dy2J allele of Lama2. To completely eliminate Ln-2 and Ln-8, we generated Ln α2/α4 double-knockout mice (Lnα2/α4-DKO; see Materials and methods). All Lnα2/α4-DKO pups appeared normal at birth and suckled effectively, but died by P13 (n = 20), preventing comparison with mature dy2J/α4nulls. Nevertheless, a nearly complete absence of sorting in Lnα2/α4-DKO spinal roots as well as distal nerves at P11 (Fig. 5, a–c) suggests strongly that Ln-10 promotes defasciculation and myelination via collaboration with dy2J-variant Ln-2.

Cell and molecular mechanisms

Amyelination has been thought to derive in large measure from disruption of Schwann cell BLs (Madrid et al., 1975; Bunge et al., 1986; Eldridge et al., 1989; Feltri et al., 2002). However, amyelination in Lama4 −/− was not accompanied by disruption of endoneurial BLs, on either myelinating or premyelinating Schwann cells (Fig. 3 d′; unpublished data). Moreover, Schwann cells in dy2J/a4null roots ensheathed and myelinated all axons despite lacking even a trace of endoneurial BLs (Fig. 4 l). Promyelinating Schwann cells in dy2J/a4null/TgA5 nerves also lacked BLs (Fig. 5 n). Thus, BLs are neither sufficient (in Lama4 −/−) or necessary (in dy2J/a4null) for Schwann cells to complete radial sorting.

Therefore, we considered potential signaling roles for Lns. Several lines of research suggest signaling through Ln receptors might promote Schwann cell proliferation during myelination. Radial sorting is closely coupled to Schwann cell mitosis (Bradley and Asbury, 1970; Webster et al., 1973), amyelinated regions of Ln α2 mutant nerves have fewer Schwann cells than normal (Bray and Aguayo, 1975; Okada et al., 1976), and Ln-1 promotes Schwann cell proliferation in vitro (Porter et al., 1987). First, we asked if Schwann cell deficits correlate specifically with amyelination, or with loss of Ln-2 or BL structure. We found Schwann cell deficits accompanied amyelination in Lama4 −/−, and large deficits accompanied severe amyelination in dy2J/α4nulls (Fig. 6 a). In transverse sections of Lama4 −/− tibial nerve, deficits in myelinated axons (24 ± 2%; calculated from Table I) and Schwann cells (30 ± 13%; Fig. 6 a) were proportional. In teased Lama4 −/− nerve preparations, myelinated fibers had normal numbers of Schwann cells (Fig. 6, b and c; controls, 12 ± 4 nuclei/field at 1000×; Lama4 −/−, 14 ± 5). Thus, Schwann cell deficits specifically accrue from amyelinated axons.

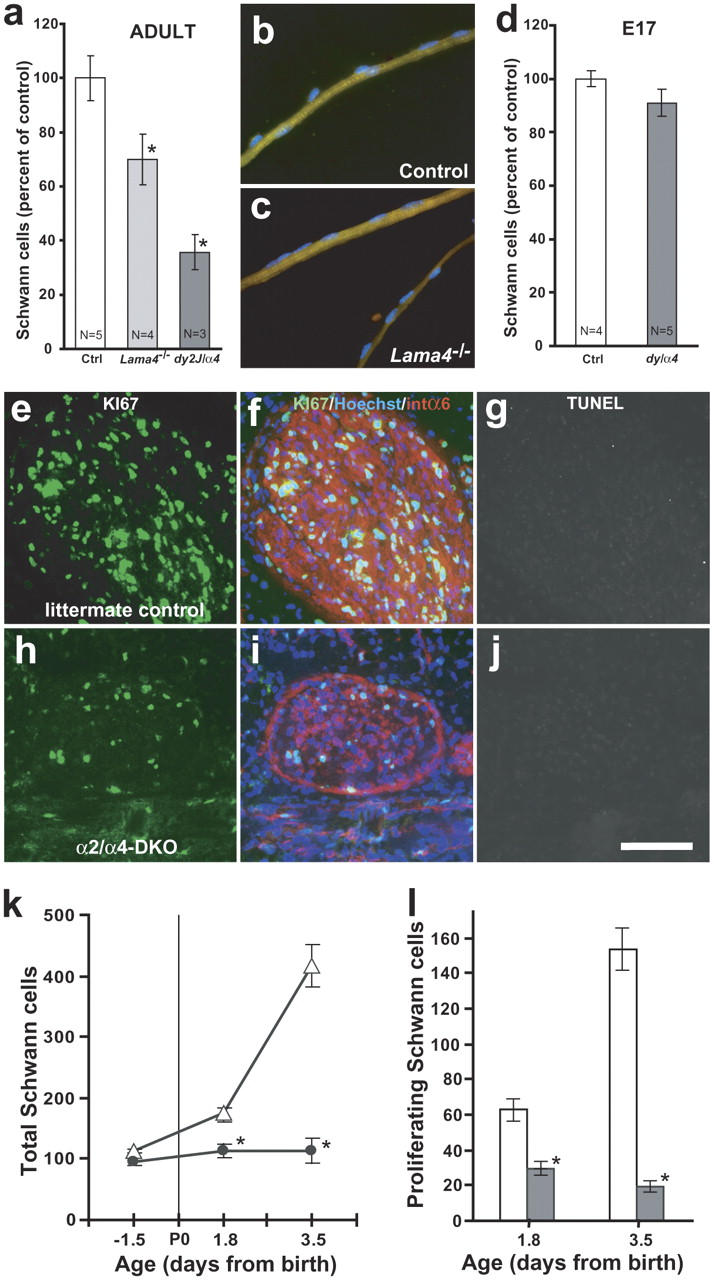

Figure 6.

Lns increase perinatal Schwann cell proliferation. (a) Adult Lama4 −/− and dy2J/α4null nerves have fewer Schwann cells per unit length than age-matched controls. Bars show nuclei per 8 μm transverse section of tibial branch at medial level; means ± SEM, n mice; 4–9 serial sections/nerve. (b and c) Myelinated fibers teased from wild-type (control) and Lama4 −/− tibial nerves have similar Schwann cell density; S100 (green); Hoechst (blue); values in text. (d) Ln-deficient nerves have normal numbers of Schwann cells at E17.5. Bars show nuclei per 10-μm section of entire medial sciatic nerve, as in a. Combined data from dy2J/α4null (n = 2) and Lnα2/α4-DKO (n = 3) are not statistically different from normal littermates. (e–j) Quadruple-stained sections of P3.5 tibial nerve from a normal (e–g) and Lnα2/α4-DKO (h–j) littermate pair: Ki67 (pseudocolored green), Hoeschst (blue), integrin α6 (red), and TUNEL (FITC shown in grayscale; g and j). Compared with controls, mutant nerves are thin and have fewer cell soma, proportionally fewer proliferative (Ki67 labeled) cells, and almost no necrotic cells. Quantitation of total soma (k) and proliferative cells (l) in 10-μm tibial nerve sections shows perinatal expansion of Schwann cell populations in normal littermates (open symbols, bars), but not Lnα2/α4-DKO (filled symbols, bars). Proliferation in mutants maintains immature Schwann cell density (numbers per 10-μm length) at embryonic levels during postnatal limb growth. Bar in j, 40 μm in b and c; 27 μm in e–j. Asterisk indicates P < 0.05 for ANOVA comparison between age-matched data sets.

Second, we asked if Schwann cell deficits temporally correlate with radial sorting. Sciatic nerves in Lnα2/α4-DKO, dy2J/α4null, and normal littermates had statistically similar numbers of Schwann cells at E17 (Fig. 6 d). Severe deficits in Lnα2/α4-DKO nerves accrued almost entirely between E17.5 (14.7 ± 8.1%) and P3.5 (73 ± 6.9%) (Fig. 6 k). Moreover, deficits occurred through inadequate proliferation rather than cell death (Fig. 6, e–l). Proliferating cells were identified with antibody to Ki67 (Lalor et al., 1987), and necrotic cells by TUNEL assay. At P3.5, 40% of normal (littermate control) endoneurial cells were Ki67-positive, whereas <20% were labeled in Ln α2/α4-DKO pups (compare with values in Fig. 6, k and l). Fewer than 1% of nuclei in normal and mutant nerves were TUNEL stained at any perinatal age (Fig. 6, g and j; unpublished data). Thus, Ln-2 and -8 are specifically required for the perinatal increase in Schwann cell proliferation that coincides with radial sorting. They appear dispensable for the proliferation of immature Schwann cells covering fascicles, consistent with EM observations.

To ask if Ln-2 and -8 promote proliferation directly, we cultured primary Schwann cells on substrates containing purified isoforms (Fig. 7, a–d). Populations plated at moderate densities on Ln-1, -2, and -8 expanded at similar rates, doubling the rate on uncoated surfaces. When Ln concentration or cell density were limiting, proliferation was significantly faster on Ln-8 than on Ln-1 or -2. These data extend previous studies with Ln-1 (Porter et al., 1987) to suggest that Ln-2 and -8 promote Schwann cell proliferation in concert with autocrine growth factors. The results are consistent with the early hypothesis that increasing cell density activates Schwann cells to invade fascicles and ensheath axons (Martin and Webster, 1973).

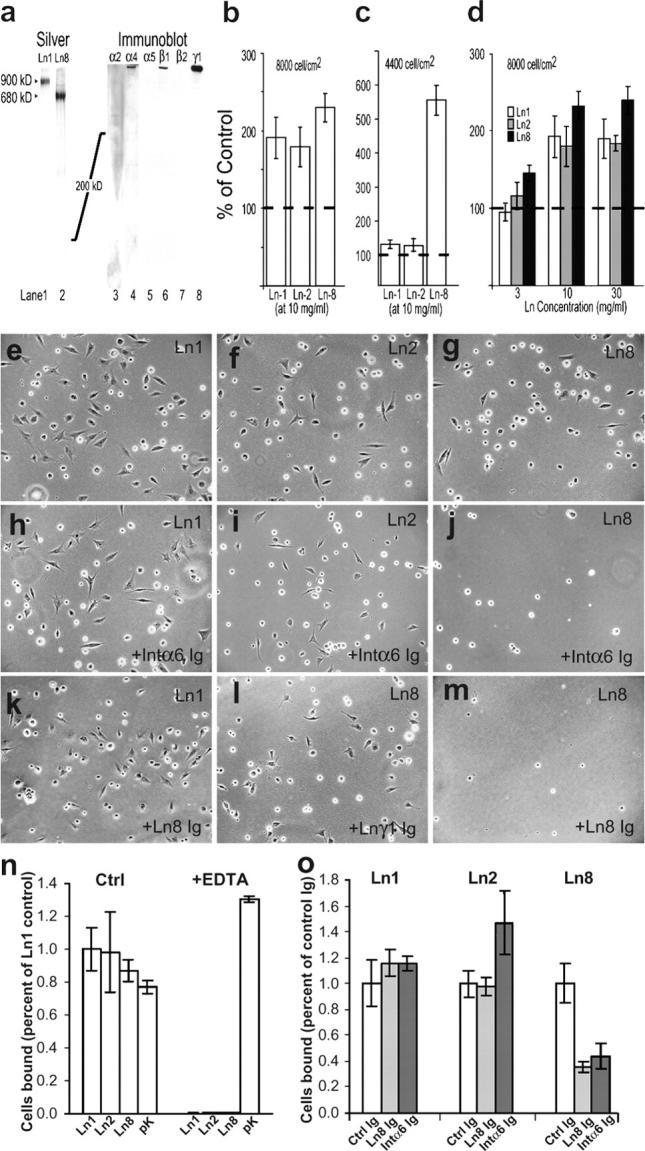

Figure 7.

Differential proliferation and adhesion on Ln-2 and -8. (a) Purified human Ln-8 is homogeneous on silver-stained gels, migrates slightly faster than Ln-1, contains α4, β1, and γ1 immunoreactivity, and lacked degradation. (b–d) Primary Schwann cells counted after culturing 3 d on purified Ln-1, -2, and -8, at high (b and d) and low (c) initial cell density. Lns promote proliferation above bare substrata (dotted lines). Ln-8 is more active at low cell density and Ln concentrations. (e–o) Schwann cells adhere (2 h) to purified Ln-1, -2, and -8. Adhesion to Lns but not poly-lysine is inhibited by EDTA (n). Adhesion to Ln-8 is selectively blocked by antibodies to integrin α6 (j and o) and Ln-8 (m and o), but not to Ln γ1 chain (l; control Ig in o).

Lastly, we used adhesion assays to ask if Schwann cells interact with Ln-2 and -8 through distinct or similar receptors (Fig. 7, e–o). Adhesion to purified Ln-1, -2, and -8, but not poly-lysine, was blocked by EDTA, consistent with a role for integrin receptors. Antiserum raised against Ln-8 blocked adhesion to Ln-8 but not Ln-2, indicating that binding to Ln-8 relies on distinct epitopes. Finally, adhesion to Ln-8 but not Ln-2 was inhibited by function-blocking antibody to integrin α6. The simplest interpretation of these data is that Ln-2 and -8 regulate Schwann cells through distinct integrin subtypes. Consistent with this notion, Schwann cell–specific disruption of the integrin β1 gene (Feltri et al., 2002) produced the pattern of amyelination (partial in sciatic nerve; absent in roots) characteristic to Lama4 −/−, and distinct from that in dy2J. The combined results suggest Ln-8 (and not Ln-2) promotes radial sorting through integrin α6β1.

Discussion

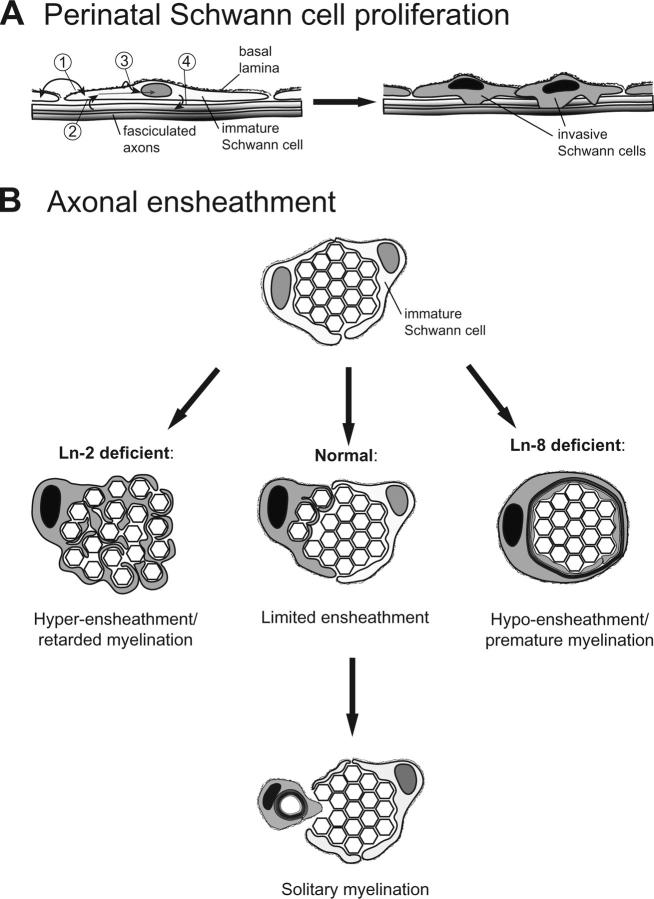

We establish a dominant role for Lns in peripheral myelination, identify which of the four isoforms (Ln 1, 2, 8, and 10) expressed by Schwann cells are primarily involved, and clarify mechanisms by which they act. Ln-2 and Ln-8 act in concert to increase rates of Schwann cell proliferation at the onset of radial sorting, such that combined Ln-2/Ln-8 deficiency prevents radial sorting altogether. Ln-2 and -8 also regulate the onset of myelin formation by postmitotic Schwann cells, but through distinct effects on axonal ensheathment. At both steps, their combined activities foster solitary relationships between myelinating Schwann cells and axons (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed roles for Ln-2 and Ln-8 in peripheral nerve development. (A) Developing Schwann cells are regulated by autocrine (1) and axon-derived (2) factors. Ln-2 and -8 are concentrated in Schwann cell BLs, on ab-axonal surfaces (3). Immature Schwann cells initially proliferate to cover axon fascicles, without dependence on Ln-2 or -8. Radial sorting commences as combined Ln-2, Ln-8, and mitogen signals increase Schwann cell proliferation rates and stimulate progeny to envelop subjacent axons (4). (B) Ln-2 and -8 differentially regulate axonal ensheathment. Ln-8 promotes small ensheathing processes and/or delays myelin formation. Ln-2 promotes onset of myelination and/or inhibits formation of ensheathing processes.

Functions for Lns in nerve development

Mechanisms underlying the transition from immature Schwann cells surrounding axon fascicles to myelinating and nonmyelinating Schwann cells ensheathing individual axons are not known. Martin and Webster (1973) observed that involution of axons along fascicle edges is immediately preceded by Schwann cell mitosis and an increase in cell density along those axons, and proposed that Schwann cell proliferation plays a primary role in the onset of radial sorting. Indeed, developing Schwann cell populations appear to expand in two stages: proliferation initially matches elongation of the embryonic nerve, and increases sharply to supply individual axons during myelination (Webster et al., 1973; Stewart et al., 1993). We found Ln-2 and -8 specifically promote the later, radial sorting component of Schwann cell proliferation. Schwann cell proliferation requires signaling through erbB receptors for neuregulins (Riethmacher et al., 1997). As Schwann cell proliferation on purified Ln-2 and -8 was highly dependent on cell density, we anticipate they act by increasing Schwann cell sensitivity to mitogenic factors such as neuregulin. A similar activity was previously shown for Ln-1 in vitro (Porter et al., 1987). Interestingly, interactions between integrin and neuregulin signaling pathways regulate the myelinating activity of oligodendrocytes as well (Colognato et al., 2002). Thus, mechanisms controlling the onset of myelination in the central and peripheral nervous systems may be conserved.

Decreased proliferation and Schwann cell deficits occur in Ln α2-deficient nerves (Bradley and Jenkison, 1973; Bray and Aguayo, 1975; Stirling, 1975; Perkins et al., 1980). However, perinatal proliferation is reportedly normal in mice with Schwann cell–specific loss of Ln γ1 or integrin β1, both of which are amyelinated (Feltri et al., 2002; Chen and Strickland, 2003). Interestingly, disruption of floxed Ln γ1 alleles occurred unexpectedly in the Schwann cell lineage at E17, through Cre expression off a CaM kinase II (CaMKII) promoter (Chen and Strickland, 2003). As this coincides with the onset of Ln-dependent proliferation we identify, CaMKII-Cre expression could begin in Ln-dependent progeny. Defects in CaMKII–Cre/Lnγ1-deficient nerves would be consistent with additional roles for Ln-2 and -8 in the invasion of fascicles and/or ensheathment of axons, as suggested previously (Chen and Strickland, 2003). Similarly, β1 integrins could preferentially mediate these later roles (Feltri et al., 2002).

Our results suggest Ln-2 and -8 coordinate axonal ensheathment by promyelinating Schwann cells. Lama4 −/− Schwann cells prematurely myelinated bundles of axons, before completing their separation. dy2J Schwann cells lingered between ensheathing multiple axons and myelinating single axons. In principle, both activating and inhibitory mechanisms could underlie these results. For example, Ln-8 may promote the formation of multiple ensheathing Schwann cell processes, or simply retard myelin formation; loss of either function could produce polyaxonal myelination. Similarly, Ln-2 may promote myelin formation, and/or limit the formation of axon-ensheathing processes. Regardless, the results provide an initial insight into the mystery of how each Schwann cell manages to myelinate a single axon.

Molecular mechanisms

Ln-2 and -8 do not fully compensate each other's loss in vivo, and have distinct binding and proliferative activities for Schwann cells in vitro, suggesting distinct receptors mediate their actions. Schwann cells express several Ln-binding integrins and dystroglycan (Previtali et al., 2001). Early steps of myelination depend greatly on β1-integrins (Fernandez-Valle et al., 1994; Feltri et al., 2002), and not dystroglycan (Saito et al., 2003). Amyelination caused by loss of integrin β1 (partial in distal nerves; nearly absent in roots) now appears to largely phenocopy loss of Ln-8 rather than Ln-2. The major β1-integrin in developing Schwann cells is integrin α6β1. As blocking antibody to integrin α6 inhibited Schwann cell binding to Ln-8 and not Ln-2 (Fig. 7), the simplest interpretation at present is that integrin α6β1 primarily mediates the effects of Ln-8 in radial sorting. Ln-2 engages additional receptors, as adding its loss to α4-deficiency (i.e., in dy2J/α4null and Lnα2/α4-DKO) produces amyelination far exceeding that in β1-integrin–deficient nerves. Testing in vivo roles for integrin α6β4, expressed by perinatal Schwann cells, may require tissue-specific mutations, as mice lacking these subunits die at birth (Dowling et al., 1996; Georges-Labouesse et al., 1996).

Endoneurial BLs

The idea that Schwann cell BLs are necessary for the proper defasciculation and myelination of axons in developing nerves (Madrid et al., 1975) has endured for nearly 30 years (Bunge, 1993; Feltri et al., 2002; Chen and Strickland, 2003). In muscle, disruption of myofiber BLs likely initiates α2-deficient myodegeneration (Moll et al., 2001; Durbeej and Campbell, 2002). However, our results show no correlation in nerves between radial sorting and endoneurial BL integrity. First, α4-deficiency has no ulterior effect on endoneurial BL structure or composition, but causes the same degree of sciatic amyelination as α2-deficiency. Second, Ln-8 promotes considerable sorting and myelination without BLs. For example, radial sorting and myelination in dy2J brachial nerves is nearly normal, develops without BLs, and is almost entirely dependent on Ln-8 (dy2J/α4null brachial nerves are severely amyelinated). The inability of Ln-8 to promote BL assembly is consistent with Ln α4 lacking amino-terminal domains required for heterotrimer polymerization (Yurchenco et al., 2004). Third, all axons in dy2J/α4null spinal roots are sorted and myelinated without endoneurial BL formation. Fourth, transgenic Ln α5 promotes myelination in dy2J/α4null sciatic nerves without forming BLs on the pre- and promyelinating Schwann cells involved in radial sorting. This last result is curious as α5-Lns are expected to promote BL formation, but is consistent with observations in α2-deficient spinal roots, which contain α5 but lack BLs (Madrid et al., 1975; Weinberg et al., 1975; Nakagawa et al., 2001). In sum, endoneurial BLs are neither necessary to achieve complete radial sorting nor sufficient to prevent amyelination. That BL integrity is irrelevant to the initial myelination of axons brings mammalian myelination into line with amphibians, in which Schwann cells acquire BLs after myelination (Webster and Billings, 1972).

Therefore, it seems likely that signaling through Ln receptors regulates Schwann cell activation during myelination. In this context, it is worth reconsidering the dy2J isoform of Ln-2 (Xu et al., 1994). Amyelination in dy2J/a4null and Lnα2/α4-DKO sciatic nerves were similarly severe, revealing that Ln-2(dy2J) is nearly inactive. Yet, the amino-terminal Lama2dy2J mutation specifically impairs the ability of Ln-2(dy2J) to polymerize and scaffold BLs, and does not prevent binding to cell surface receptors (Colognato and Yurchenco, 1999), which seems to argue strongly for the importance of BL structure. To reconcile these results with the above view that BLs are not required for sorting, we suggest that short-arm interactions between Ln-2 heterotrimers are critical for Ln-2 to activate its Schwann cell receptors, possibly through receptor aggregation. Further, we speculate that transgenic expression of Ln α5 promotes radial sorting without BL assembly by stabilizing short-arm interactions with Ln-2(dy2J) and restoring the activation of Ln-2 receptors. Ln-8, which lacks an α-chain short arm, may paradoxically promote the severe amyelination in dy2J roots by diluting Ln-10/Ln-2(dy2J) interactions.

Materials and methods

Animals

Use was by National Institutes of Health guidelines and approved by Oregon Health and Science University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mutants received accessible food and water and were killed at terminal stages whenever possible. C57BL/6J and Lama2 dy2J mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice null for Lama2 (Lama2 dy3K) and Lama4 were described previously (Miyagoe et al., 1997; Patton et al., 2001); both were backcrossed five generations to C57BL/6J. Mutant alleles of Lama2 and Lama4 on chromosome 10 were linked by mating heterozygous males (Lama2+/dy2J;Lama4−/+; or Lama2+/dy3K;Lama4−/+) to wild-type females and screening offspring for possession of both mutant α2 and α4 alleles (which required paternal recombination). Lama4null recombined with Lama2dy2J in 3 of 171 offspring, and with Lama2dy3K in 2 of 125 offspring, in agreement with reported genetic distance (Miner et al., 1997). Linkage was confirmed by mating with wild types. Mutants were born at Mendelian frequencies in all founder lines. dy2J/α4null and α2/α4null-DKO mutants did not differ significantly between lines, or from F1 mutants from inter-line crosses in which sites of recombination remain heterozygous, and their data were pooled. Ln α2 and α4 were undetectable in Lnα2/α4-DKO tissues, as in single mutants (Miyagoe et al., 1997; Patton et al., 2001). A previously described full-length mouse Ln α5 cDNA transgene (Kikkawa et al., 2002) prevents embryonic lethality and rescues all known defects in Lama5 −/− mice.

Genotypes were identified by PCR off tail-tip DNA, using the following sense (-S) and antisense (-AS) primers. Lama4 wt-S: 5′-GGCAGGCGTCCCAGTGTC-3′; -AS: 5′-CAACAAAGTTGCAACTTGGGCTC-3′. Lama4 null-S: 5′-AGCGTACCCTCCCACCCAC-3′; -AS: 5′-GCTAAAGCGCATGCTCCAGACTG-3′, in PGK promoter. Lama2 wt-S: 5′-CCAGATTGCCTACGTAATTG-3′; -AS: 5′-CCTCTCCATTTTCTAAAG-3′. Lama2 dy3K-S: 5′-CTTTCAGATTGCATTGCAAGC-3′; -AS: 5′-TCGTTTGTTCGGATCCGTCG-3′. Lama2 dy2J-S: 5′-TCCTGCTGTCCTGAATCTTG-3′; -AS: 5′-AGGCTCATGAGTCCTTTG-3′. dy2J offspring were typed similar to (Vilquin et al., 2000). Touch-down PCR across the point mutation site (annealing from 60°C to 52°C in 10 cycles plus 25 cycles at 50°C) was followed by NdeI digestion to produce 164- and 109-bp fragments from dy2J but not wild-type product. Digestion ambiguities were resolved by HypCH4 III, which cuts wild-type but not dy2J product.

Antibodies

Rat mAbs 198 and 200 to Ln α1 were from Lydia Sorokin (Sorokin et al., 1992; Lund University, Lund, Sweden). Rabbit antibodies to Ln α1 and α2 (Rambukkana et al., 1997) were from Peter Yurchenco (Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Piscataway, NJ); anti-α1 was generated against EHS Ln-1, affinity purified against E3 fragment, and cross-adsorbed against E8 fragment. mAbs to α2 (4H8-2; Qbiogene), β1 (MAB1928; CHEMICON International), and γ1 (MAB1914; CHEMICON International) were purchased. Rabbit and guinea pig antibodies to Ln α4, α5, and β2 are described elsewhere (Miner et al., 1997). A pAb to purified human Ln-8 (Fig. 8), and mAb 1G5 raised to an α4 LG1-domain fusion protein, were generated in Lama4 −/− mice; each labels Ln-8 on blots (Fig. 5 a) and all α4-rich BLs in normal mice, but no BLs in Lama4 −/−. Rabbit antibodies to integrin β1D and agrin were gifts from Eva Engvall (Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA) and David Glass (corporate license from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals), respectively. Other purchased antibodies: MAB1946 (entactin), MAB1948 (perlecan), AB1920 (integrin α3), and MAB1982 (integrin α6) from CHEMICON International; GoH3 (integrin α6; Beckman Coulter); CD29 (integrin β1; BD Biosciences); VIA4-1 (α-dystroglycan; Upstate Biotechnology); β-dystroglycan and β-sarcoglycan (NovoCastra); neurofilament (2H3; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank repository, Ames, Iowa); S100 (Neomarkers); Ki67 (Vector Laboratories); and Alexa 488– (Molecular Probes, Inc.), Cy3-, and Cy5-conjugated (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) second antibodies.

Lns

Mouse Ln-1 and human Ln-2 were from CHEMICON International. Human Ln-8 was purified from T98G cell–conditioned media using nondenaturing methods. Protein precipitated by 40% ammonium sulfate was bound to a DEAE-Sepharose Fast-Flow FPLC column (Amersham Biosciences) in imidazole (10 mM; pH 7.0) and eluted with a 0.05–1.0-M NaCl gradient. Pooled fractions containing Ln-8 (0.4–0.5 M NaCl) by dot-blot assay were dialyzed (5 mM phosphate and 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.3) and repurified by DEAE-Sepharose. The second DEAE pool was concentrated (Aquacide; Calbiochem) and size-fractionated by FPLC through Superose 6 HR. The final pool contained a single major protein complex at 680 kDl on silver-stained SDS-PAGE nonreducing gels (Fig. 5 a). In this material, immunoreactivity for Ln α4, β1, and γ1 chains comigrated, and α1, α2, α5, and β2 were not detectable.

Histology

For resin sections, killed animals were perfused with 3% (wt/vol) PFA, 1% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, in PBS; nerves were incubated overnight at 4°C in 4% PFA, 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate; 1-mm pieces were post-fixed 1 h in 1% OsO4, dehydrated through ethanol, and embedded in Epon. Semithin sections (0.5 μm) were stained with toluidine blue (1% in alcohol) and imaged by digital color photomicroscopy. Ultrathin sections (90 nm) stained with uranyl acetate were imaged by transmission EM. Quantitation of myelination patterns was performed on photographic montages of transverse sections of the entire tibial nerve. Myelinated fibers were counted from semithin sections; nonmyelinated axons were counted from ultrathin sections on Formvar-coated hole grids photographed at 2,000–10,000×.

Immunohistochemistry was done as described previously (Miner et al., 1997), using 8–10-μm cryostat sections cut from OCT-embedded unfixed tissue snap frozen in −150°C 2-methylbutane, or teased sciatic nerves prepared by gently spreading 1–2-mm segments on subbed slides. Ln α4 and β2 epitopes required denaturation (Miner et al., 1997). In brief, sections were incubated overnight with antibodies diluted in PBS containing 5% (wt/vol) BSA, washed in PBS, and bound antibodies detected with species-specific, fluorescent second antibodies (1 h). Teased fibers were prefixed for 15 min with 2% PFA, cleared with 0.1 M glycine, and stained in PBS with 5% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100. Hoechst 33258 (Molecular Probes, Inc.) was added to mounting medium to visualize nuclei. TUNEL staining was performed according to kit directions (Roche; product 1684795). Myelin was visible by intrinsic fluorescence (Ex365 nm/Em450 nm). Images were made at ambient temperature with PlanApo 60× (1.4 NA) oil-immersion lenses on BX microscopes (Olympus), using either a DC 350F camera and IM50 acquisition software (Leica) or an FV300 confocal scan head (Olympus). Multiply stained images were colorized and superimposed in Photoshop 6.0. Quantitation of Schwann cell nuclei was performed strictly on transverse sections of PFA-fixed medial sciatic nerves frozen in situ (the thigh). All nerve nuclei (Hoechst, total; Ki67, proliferating; TUNEL, apoptotic) not residing in perineurial sheaths (distinguished by integrin α6 counterstaining and morphology) were counted in digital images taken at 400× without background subtraction.

Cell culture

Proliferation assays used Schwann cells (92–98% S100-positive) freshly prepared from desheathed E13 chick sciatic nerves (Patton et al., 1998). Plastic 96-wells were coated with poly-l-lysine (0.1 mg/ml, 1 h; Sigma-Aldrich), then Ln-1, -2, or -8 in PBS (for 8 h at 4°C; concentrations in Fig. 7). Cells were plated at indicated densities in 0.2 ml DME and 10% FCS, and were incubated at 37°C. Population levels were measured 3 d later, by release with 0.1 ml of 0.05% trypsin, 10 mM EDTA, and duplicate hemocytometer readings. Experiments included triplicate wells for each condition. In control experiments, fed by 50% medium replacement at d 3, cells remained adherent to all substrates at d 5, when TUNEL assay (Roche) labeled <2% of cells. Adhesion assays used Schwann cells cultured 10 d or less after preparation from P4 mice. Schwann cells were enriched (>97% S100-reactive) by complement-mediated lysis of fibroblasts with anti-Thy1.1 antibody (TN-26; Sigma-Aldrich), and expanded in DME, 10% FCS, and recombinant heregulin (10 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Constellations of substrate spots of Ln-1, -2, -8 (10 μg/ml PBS), and poly-d-lysine (100 μg/ml) were formed on tissue culture plastic by incubating 5-μl aliquots overnight at 4°C in a humid box. Sulforhodamine (20 μg/ml) was included to identify spot boundaries by fluorescence. Substrates were washed (PBS), blocked 4–12 h with 10 mg/ml Ig-free BSA, and preincubated for 30 min in DME with or without anti-Ln antibodies. Cells were collected from growth plates by minimal trypsin treatment, thrice washed in DME, resuspended to 0.5 × 106/ml in DME containing 3 mg/ml Ig-free BSA with or without blocking antibodies, preincubated 30 min at 4°C, and incubated with substrates (23,000 cells/cm2) for 2 h at 37°C. After washing with PBS, bound cells were fixed (3% PFA in PBS) and coverslipped in medium containing Hoechst. Cells were counted at 400× with phase and fluorescence optics and an eyepiece reticule. Averages were calculated from four contiguous image fields, nearly spanning each spot. Reported values show mean ± SEM for three assays.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Drs. Sorokin and Yurchenco for critical immunoreagents, H. Sharpless for genetic screens, and K. Fujimoto for cell culture.

Work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS40759 to B.L. Patton; GM60432 to J.H. Miner; and NS39550 and RR00163 to L.S. Sherman), the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to B.L. Patton), and the March of Dimes (to J.H. Miner).

Abbreviations used in this paper: BL, basal lamina; CNS, central nervous system; Ln, laminin.

References

- Biscoe, T.J., K.W. Caddy, D.J. Pallot, U.M. Pehrson, and C.A. Stirling. 1974. The neurological lesion in the dystrophic mouse. Brain Res. 76:534–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, W.G., and A.K. Asbury. 1970. Duration of synthesis phase in neurilemma cells in mouse sciatic nerve during degeneration. Exp. Neurol. 26:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, W.G., and M. Jenkison. 1973. Abnormalities of peripheral nerves in murine muscular dystrophy. J. Neurol. Sci. 18:227–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, W.G., and M. Jenkison. 1975. Neural abnormalities in the dystrophic mouse. J. Neurol. Sci. 25:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, G.M., and A.J. Aguayo. 1975. Quantitative ultrastructural studies of the axon Schwann cell abnormality in spinal nerve roots from dystrophic mice. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 34:517–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge, M.B. 1993. Schwann cell regulation of extracellular matrix biosynthesis and assembly. Peripheral Neuropathy. Vol. 1. P.J. Dyck, P.K. Thomas, P.A. Low, and J.F. Poduslo, editors. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia. 299–316.

- Bunge, R.P., M.B. Bunge, and C.F. Eldridge. 1986. Linkage between axonal ensheathment and basal lamina production by Schwann cells. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 9:305–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.L., and S. Strickland. 2003. Laminin γ1 is critical for Schwann cell differentiation, axon myelination, and regeneration in the peripheral nerve. J. Cell Biol. 163:889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato, H., and P.D. Yurchenco. 1999. The laminin α2 expressed by dystrophic dy(2J) mice is defective in its ability to form polymers. Curr. Biol. 9:1327–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato, H., W. Baron, V. Avellana-Adalid, J.B. Relvas, A. Baron-Van Evercooren, E. Georges-Labouesse, and C. ffrench-Constant. 2002. CNS integrins switch growth factor signaling to promote target-dependent survival. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:833–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, J., Q.C. Yu, and E. Fuchs. 1996. β4 integrin is required for hemidesmosome formation, cell adhesion and cell survival. J. Cell Biol. 134:559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej, M., and K.P. Campbell. 2002. Muscular dystrophies involving the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: an overview of current mouse models. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12:349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge, C.F., M.B. Bunge, and R.P. Bunge. 1989. Differentiation of axon-related Schwann cells in vitro: II. Control of myelin formation by basal lamina. J. Neurosci. 9:625–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltri, M.L., D. Graus Porta, S.C. Previtali, A. Nodari, B. Migliavacca, A. Cassetti, A. Littlewood-Evans, L.F. Reichardt, A. Messing, A. Quattrini, et al. 2002. Conditional disruption of β1 integrin in Schwann cells impedes interactions with axons. J. Cell Biol. 156:199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Valle, C., L. Gwynn, P.M. Wood, S. Carbonetto, and M.B. Bunge. 1994. Anti-β1 integrin antibody inhibits Schwann cell myelination. J. Neurobiol. 25:1207–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garratt, A.N., S. Britsch, and C. Birchmeier. 2000. Neuregulin, a factor with many functions in the life of a Schwann cell. Bioessays. 22:987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges-Labouesse, E., N. Messaddeq, G. Yehia, L. Cadalbert, A. Dierich, and M. Le Meur. 1996. Absence of integrin α6 leads to epidermolysis bullosa and neonatal death in mice. Nat. Genet. 13:370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa, Y., C.L. Moulson, I. Virtanen, and J.H. Miner. 2002. Identification of the binding site for the Lutheran blood group glycoprotein on laminin α5 through expression of chimeric laminin chains in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 277:44864–44869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalor, P.A., P.I. Mapp, P.A. Hall, and P.A. Revell. 1987. Proliferative activity of cells in the synovium as demonstrated by a monoclonal antibody, Ki67. Rheumatol. Int. 7:183–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid, R.E., E. Jaros, M.J. Cullen, and W.G. Bradley. 1975. Genetically determined defect of Schwann cell basement membrane in dystrophic mouse. Nature. 257:319–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.R., and H.D. Webster. 1973. Mitotic Schwann cells in developing nerve: their changes in shape, fine structure, and axon relationships. Dev. Biol. 32:417–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner, J.H., B.L. Patton, S.I. Lentz, D.J. Gilbert, W.D. Snider, N.A. Jenkins, N.G. Copeland, and J.R. Sanes. 1997. The laminin α chains: expression, developmental transitions, and chromosomal locations of α1–5, identification of heterotrimeric laminins 8–11, and cloning of a novel α3 isoform. J. Cell Biol. 137:685–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner, J.H., J. Cunningham, and J.R. Sanes. 1998. Roles for laminin in embryogenesis: exencephaly, syndactyly, and placentopathy in mice lacking the laminin α5 chain. J. Cell Biol. 143:1713–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky, R., K.R. Jessen, A. Brennan, D. Parkinson, Z. Dong, C. Meier, E. Parmantier, and D. Lawson. 2002. Schwann cells as regulators of nerve development. J. Physiol. (Paris). 96:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagoe, Y., K. Hanaoka, I. Nonaka, M. Hayasaka, Y. Nabeshima, K. Arahata, and S. Takeda. 1997. Laminin α2 chain-null mutant mice by targeted disruption of the Lama2 gene: a new model of merosin (laminin 2)-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy. FEBS Lett. 415:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll, J., P. Barzaghi, S. Lin, G. Bezakova, H. Lochmuller, E. Engvall, U. Muller, and M.A. Ruegg. 2001. An agrin minigene rescues dystrophic symptoms in a mouse model for congenital muscular dystrophy. Nature. 413:302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, M., Y. Miyagoe-Suzuki, K. Ikezoe, Y. Miyata, I. Nonaka, K. Harii, and S. Takeda. 2001. Schwann cell myelination occurred without basal lamina formation in laminin α2 chain-null mutant (dy 3K/dy 3K) mice. Glia. 35:101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada, E., V. Mizuhira, and H. Nakamura. 1976. Dysmyelination in the sciatic nerves of dystrophic mice. J. Neurol. Sci. 28:505–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada, E., V. Mizuhira, and H. Nakamura. 1977. Abnormally combined myelinated and unmyelinated nerves in dystrophic mice. J. Neurol. Sci. 33:243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, B.L., J.H. Miner, A.Y. Chiu, and J.R. Sanes. 1997. Distribution and function of laminins in the neuromuscular system of developing, adult, and mutant mice. J. Cell Biol. 139:1507–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, B.L., A.Y. Chiu, and J.R. Sanes. 1998. Synaptic laminin prevents glial entry into the synaptic cleft. Nature. 393:698–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, B.L., A.M. Connoll, P.T. Martin, J.M. Cunningham, S. Mehta, A. Pestronk, J.H. Miner, and J.R. Sanes. 1999. Distribution of ten laminin chains in dystrophic and regenerating muscles. Neuromuscul. Disord. 9:423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, B.L., J.M. Cunningham, J. Thyboll, J. Kortesmaa, H. Westerblad, L. Edstrom, K. Tryggvason, and J.R. Sanes. 2001. Properly formed but improperly localized synaptic specializations in the absence of laminin α4. Nat. Neurosci. 4:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, C.S., G.M. Bray, and A.J. Aguayo. 1980. Persistent multiplication of axon-associated cells in the spinal roots of dystrophic mice. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 6:83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter, S., L. Glaser, and R.P. Bunge. 1987. Release of autocrine growth factor by primary and immortalized Schwann cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:7768–7772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali, S.C., M.L. Feltri, J.J. Archelos, A. Quattrini, L. Wrabetz, and H. Hartung. 2001. Role of integrins in the peripheral nervous system. Prog. Neurobiol. 64:35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali, S.C., G. Dina, A. Nodari, M. Fasolini, L. Wrabetz, U. Mayer, M.L. Feltri, and A. Quattrini. 2003. a. Schwann cells synthesize α7β1 integrin which is dispensable for peripheral nerve development and myelination. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 23:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previtali, S.C., A. Nodari, C. Taveggia, C. Pardini, G. Dina, A. Villa, L. Wrabetz, A. Quattrini, and M.L. Feltri. 2003. b. Expression of laminin receptors in Schwann cell differentiation: evidence for distinct roles. J. Neurosci. 23:5520–5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambukkana, A., J.L. Salzer, P.D. Yurchenco, and E.I. Tuomanen. 1997. Neural targeting of Mycobacterium leprae mediated by the G domain of the laminin-α2 chain. Cell. 88:811–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riethmacher, D., E. Sonnenberg-Riethmacher, V. Brinkmann, T. Yamaai, G.R. Lewin, and C. Birchmeier. 1997. Severe neuropathies in mice with targeted mutations in the ErbB3 receptor. Nature. 389:725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito, F., S.A. Moore, R. Barresi, M.D. Henry, A. Messing, S.E. Ross-Barta, R.D. Cohn, R.A. Williamson, K.A. Sluka, D.L. Sherman, et al. 2003. Unique role of dystroglycan in peripheral nerve myelination, nodal structure, and sodium channel stabilization. Neuron. 38:747–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, L.M., S. Conzelmann, P. Ekblom, C. Battaglia, M. Aumailley, and R. Timpl. 1992. Monoclonal antibodies against laminin A chain fragment E3 and their effects on binding to cells and proteoglycan and on kidney development. Exp. Cell Res. 201:137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, H.J., L. Morgan, K.R. Jessen, and R. Mirsky. 1993. Changes in DNA synthesis rate in the Schwann cell lineage in vivo are correlated with the precursor–Schwann cell transition and myelination. Eur. J. Neurosci. 5:1136–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, C.A. 1975. Abnormalities in Schwann cell sheaths in spinal nerve roots of dystrophic mice. J. Anat. 119:169–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilquin, J.T., N. Vignier, J.P. Tremblay, E. Engvall, K. Schwartz, and M. Fiszman. 2000. Identification of homozygous and heterozygous dy2J mice by PCR. Neuromuscul. Disord. 10:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster, H.D. 1971. The geometry of peripheral myelin sheaths during their formation and growth in rat sciatic nerves. J. Cell Biol. 48:348–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Hde F., and S.M. Billings. 1972. Myelinated nerve fibers in Xenopus tadpoles: in vivo observations and fine structure. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 31:102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster, H.D., R. Martin, and M.F. O'Connell. 1973. The relationships between interphase Schwann cells and axons before myelination: a quantitative electron microscopic study. Dev. Biol. 32:401–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, H.J., P.S. Spencer, and C.S. Raine. 1975. Aberrant PNS development in dystrophic mice. Brain Res. 88:532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H., X.R. Wu, U.M. Wewer, and E. Engvall. 1994. Murine muscular dystrophy caused by a mutation in the laminin α2 (Lama2) gene. Nat. Genet. 8:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenco, P.D., P.S. Amenta, and B.L. Patton. 2004. Basement membrane assembly, stability and activities observed through a developmental lens. Matrix Biol. 22:521–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]