Abstract

All ligands of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which has important roles in development and disease, are released from the membrane by proteases. In several instances, ectodomain release is critical for activation of EGFR ligands, highlighting the importance of identifying EGFR ligand sheddases. Here, we uncovered the sheddases for six EGFR ligands using mouse embryonic cells lacking candidate-releasing enzymes (a disintegrin and metalloprotease [ADAM] 9, 10, 12, 15, 17, and 19). ADAM10 emerged as the main sheddase of EGF and betacellulin, and ADAM17 as the major convertase of epiregulin, transforming growth factor α, amphiregulin, and heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in these cells. Analysis of adam9/12/15/17− /− knockout mice corroborated the essential role of adam17− /− in activating the EGFR in vivo. This comprehensive evaluation of EGFR ligand shedding in a defined experimental system demonstrates that ADAMs have critical roles in releasing all EGFR ligands tested here. Identification of EGFR ligand sheddases is a crucial step toward understanding the mechanism underlying ectodomain release, and has implications for designing novel inhibitors of EGFR-dependent tumors.

Keywords: EGF receptor; EGF receptor ligands; ADAMs; ectodomain shedding; growth factor signaling

Introduction

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway has critical functions in development and in diseases such as cancer (Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001). Ligands of the EGFR comprise a family of structurally and functionally related integral membrane proteins that can be proteolytically processed and released from cells (Harris et al., 2003). EGFR ligands include EGF (Cohen, 1965), heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF; Higashiyama et al., 1991), TGFα (Derynck et al., 1984), betacellulin (Shing et al., 1993), amphiregulin (Shoyab et al., 1989), epiregulin (Toyoda et al., 1995), and epigen (Strachan et al., 2001). Although membrane-bound EGFR ligands can engage in juxtacrine signaling (Brachmann et al., 1989; Wong et al., 1989; Higashiyama et al., 1991), a metalloprotease activity is critical for activation of EGFR signaling under a variety of circumstances. For example, EGFR-dependent proliferation and migration of a mammary epithelial cell line can be inhibited by the metalloprotease inhibitor batimastat (BB94), and this inhibition is rescued by addition of soluble EGF (Dong et al., 1999). Furthermore, activation of TGFα and potentially other EGFR ligands during mouse development depends on the presence of functional ADAM17 (Peschon et al., 1998). Moreover, the metalloprotease-dependent release of HB-EGF as well as amphiregulin from cells has been described as a key step in the transactivation of the EGFR by different G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs; Prenzel et al., 1999; Gschwind et al., 2003; Lemjabbar et al., 2003). Production of soluble HB-EGF by keratinocytes is up-regulated in response to wounding, and a metalloprotease inhibitor that blocks release of EGFR ligands from these cells abolishes their migration in vitro, and wound healing in vivo (Tokumaru et al., 2000). Shedding of HB-EGF also has an important role in heart development (Jackson et al., 2003; Yamazaki et al., 2003) and in a mouse model of myocardial hypertrophy, which can be prevented through a metalloprotease inhibitor (Asakura et al., 2002). A recent report demonstrates that even juxtacrine activation of the EGFR by TGFα on an adjacent cell can require a metalloprotease activity (Borrell-Pages et al., 2003). Finally, all three EGFR ligands in Drosophila (Spitz, Gurken, and Keren) are activated via cleavage of their transmembrane anchors (Lee et al., 2001; Urban et al., 2001; Ghiglione et al., 2002; Tsruya et al., 2002; Shilo, 2003). However, in Drosophila, different proteolytic enzymes, the Rhomboid-type proteases, have been implicated in this process (Urban et al., 2002). Thus, proteolytic processing of EGFR ligands is emerging as a critical step in their functional regulation under several different circumstances.

Metalloproteases of the ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloprotease) family are thought to be responsible for shedding of certain EGFR ligands. ADAMs are membrane-anchored glycoproteins with diverse functions, including critical roles in fertilization, neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and in shedding of membrane-bound proteins from cells (Black and White, 1998; Schlöndorff and Blobel, 1999; Primakoff and Myles, 2000; Seals and Courtneidge, 2003). Mice lacking ADAM17 die perinatally and resemble mice lacking TGFα (Mann et al., 1993), HB-EGF (Iwamoto et al., 2003; Jackson et al., 2003), and the EGFR (Miettinen et al., 1995; Sibilia and Wagner, 1995; Threadgill et al., 1995; Peschon et al., 1998). Consistent with these observations, ADAM17-deficient cells have been shown to be defective in shedding of TGFα, HB-EGF, and amphiregulin (Peschon et al., 1998; Merlos-Suarez et al., 2001; Sunnarborg et al., 2002). However, in addition to ADAM17, three other ADAMs have been linked to HB-EGF shedding. Overexpression of ADAM9 increases HB-EGF shedding in VeroH cells, whereas a mutant form of ADAM9 that is presumably unfolded and retained in the ER decreases HB-EGF shedding (Izumi et al., 1998); yet no defect in HB-EGF shedding was observed in cells lacking ADAM9 (Weskamp et al., 2002). Furthermore, ADAM12 reportedly has a role in HB-EGF shedding in the heart (Asakura et al., 2002) and in the down-regulation of cell-associated HB-EGF after stimulation with the phorbol ester PMA (Kurisaki et al., 2003). ADAM10 is the fourth ADAM to be implicated in HB-EGF shedding as part of the crosstalk between GPCRs and the EGFR (Lemjabbar and Basbaum, 2002; Yan et al., 2002). The remaining EGFR ligands, EGF, betacellulin, epiregulin, and epigen, are also known to be shed from cells, yet little information is available about the responsible enzyme(s) (Dempsey et al., 1997; Harris et al., 2003).

A crucial step toward understanding the mechanism underlying proteolytic cleavage of EGFR ligands (and its potential role in their activation) is to identify the responsible enzyme(s). In previous papers, different cell types and different approaches were used to analyze shedding of some EGFR ligands (see previous paragraphs), including antisense oligonucleotides and overexpression of both wild-type and putative dominant-negative ADAM constructs. Here, we chose a genetically defined system that is less prone to potential artifacts to evaluate the role of ADAMs in EGFR ligand shedding. To address potential compensatory or redundant functions between ADAMs 9, 12, 15, and 17, we generated adam9/12/15 −/− and adam9/12/15/17 −/− mice. Furthermore, we used cells isolated from wild-type, adam9/12/15 −/−, adam10 −/− , adam17 −/− , adam19 −/− , or adam9/12/15/17 −/− mice to evaluate how loss of one or more widely expressed ADAMs affects the shedding of different EGFR ligands. This paper represents the first systematic characterization of EGFR ligand processing using mouse cells that lack one or more candidate sheddase of the ADAM family of metalloproteases.

Results

Generation of adam9/12/15 − /− triple knockout mice to assess potential compensatory or redundant roles of these candidate EGFR ligand sheddases in mouse development

ADAMs 9 and 12 have previously been implicated as sheddases for HB-EGF (Izumi et al., 1998; Asakura et al., 2002; Kurisaki et al., 2003). To evaluate potential redundant or compensatory roles of ADAMs 9 and 12, as well as the related ADAM 15 in development and in the shedding of HB-EGF and other EGFR ligands, we generated double knockout mice (adam9/15 −/−) and triple knockout mice (adam9/12/15 −/−) as described in the Materials and methods. Table I shows that adam9/15 −/− double knockout mice were born with the expected Mendelian ratio from matings of doubly heterozygous parents. adam9/15 −/− mice were viable and fertile, and did not display any evident spontaneous pathological phenotypes (see Materials and methods for details). Triple knockout mice lacking ADAMs 9, 12, and 15 were generated by mating adam9/15 −/− parents carrying one mutant ADAM12 allele (adam9/15 −/− 12 +/−). The genotype of offspring from these matings was Mendelian with respect to the mutant ADAM12 allele (Table II), and adam9/12/15 −/− triple knockout mice were viable and fertile and did not display any evident pathological phenotypes (see below, and Materials and methods for details).

Table I.

Genotype of offspring from matings of adam9 +/− 15 +/− parents

| Genotype of offspring | Expected | Observed |

|---|---|---|

| % | % | |

| 9+/+15+/+ | 6.25 | 5.5 (10) |

| 9+/+15+/− | 12.5 | 15.0 (27) |

| 9+/+15−/− | 6.25 | 5.0 (9) |

| 9+/−15+/+ | 12.5 | 12.8 (23) |

| 9+/−15+/− | 25.0 | 23.9 (43) |

| 9+/−15−/− | 12.5 | 12.8 (23) |

| 9−/−15+/+ | 6.25 | 5.5 (10) |

| 9−/−15+/− | 12.5 | 15.5 (27) |

| 9−/−15−/− | 6.25 | 4.4 (8) |

Numbers in parentheses, # (total of 180).

Table II.

Genotype of offspring from matings of adam9 −/− 15 −/− 12 +/− parents

| Genotype of offspring | Percent |

|---|---|

| 9−/−15−/−12+/+ | 30.1 (50) |

| 9−/−15−/−12+/− | 44.0 (73) |

| 9−/−15−/−12−/− | 25.9 (43) |

Numbers in parentheses, # (total of 166).

Ectodomain shedding of EGFR ligands in mouse embryonic fibroblasts

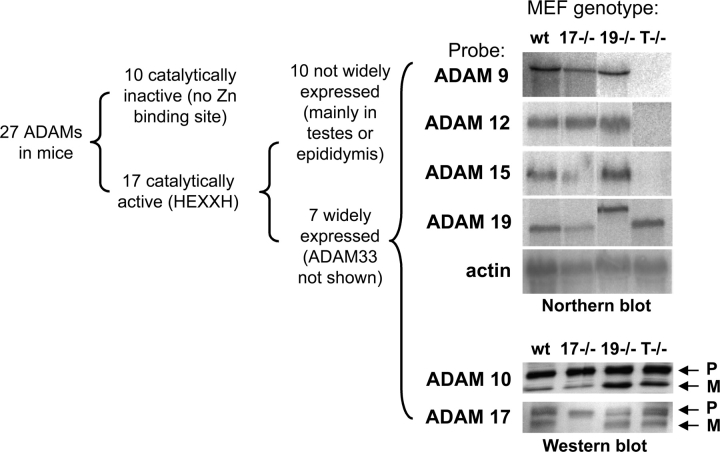

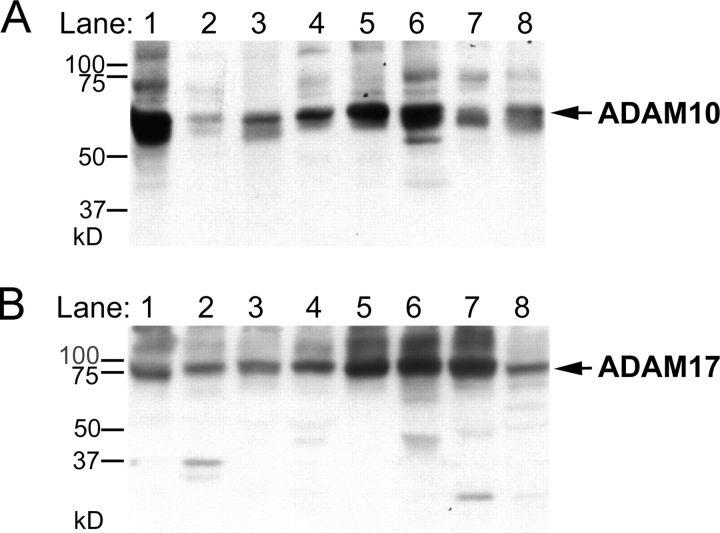

To further explore the role of ADAMs in EGFR ligand shedding, we turned to cell-based assays using cells isolated from triple knockout adam9/12/15 −/− mice, as well as from animals lacking ADAM10, ADAM17, or ADAM19, and wild-type controls. This allowed us to evaluate the contribution of all but one of the widely expressed and catalytically active ADAMs (ADAMs 9, 10, 12, 15, 17, and 19; see Fig. 1; ADAM33 was not included in this work) to the shedding of the EGFR ligands TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, HB-EGF, betacellulin, and EGF. The general approach was to transfect cells with alkaline phosphatase (AP)–tagged forms of EGFR ligands, and then to quantitate shedding by measuring AP activity released into the culture supernatant, or by an in-gel detection of the released AP domain (Weskamp et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2002; see Materials and methods for details). Because immortalization of primary cells can significantly affect the expression pattern of ADAMs and other genes (unpublished data), shedding experiments were performed with primary E13.5 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) whenever this was possible. The only exceptions were adam10 −/− and adam10 +/− cell lines, which were immortalized because adam10 −/− embryos die early in embryogenesis (E9.5) (Hartmann et al., 2002). Northern or Western blot analyses confirmed that primary mEFs from wild-type mice indeed express all ADAMs analyzed here (ADAMs9, 10, 12, 15, 17, and 19; see Fig. 1). Furthermore, Northern blots of RNA isolated from primary adam −/− cells confirmed the absence of wild-type RNA for the corresponding targeted ADAM(s). Finally, Western blot analysis confirmed that ADAM10 is expressed in all adam −/− primary mEFs, and that no mature ADAM17 is produced in adam17 −/− cells.

Figure 1.

Expression of widely expressed and catalytically active ADAMs in MEFs. ADAMs are grouped by expression pattern and presence or absence of a catalytic site (HEXXH) in the metalloprotease domain. 27 ADAMs have been identified in mice, of which 10 lack an HEXXH sequence, and are presumably not catalytically active. Out of 17 ADAMs with an HEXXH sequence, 10 are mainly expressed in the testes or epididymis, or are not widely expressed (J.M. White, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA; http://www.people.virginia.edu/%7Ejw7g/Table_of_the_ADAMs.html). Six of the seven widely expressed HEXXH-containing ADAMs were included in this paper. The top right panel shows a Northern blot analysis of the expression of ADAMs 9, 12, 15, and 19 in primary MEFs. The ADAM19 mRNA in adam19 −/− cells is larger than in the other cells analyzed because the ADAM19 gene is disrupted by insertion of a secretory gene trap (Zhou et al., 2004). The bottom right panel is a Western blot depicting expression of ADAMs 10 and 17 in the primary embryonic fibroblasts used here. Both pro- and mature ADAM10 are expressed in all primary mEFs analyzed here, and pro- and mature ADAM17 are expressed in wild-type, adam19 −/−, and adam9/12/15 −/− cells. Note that the exon containing the Zn2+-binding catalytic site of ADAM17 is deleted in adam17 −/− cells (ADAM17ΔZn/ΔZn). This will most likely impair proper protein folding, resulting in retention of mutant ADAM17 in the ER by chaperones and subsequent degradation (Suzuki et al., 1998). wt, wild type; 17−/−, adam17 −/−; 19−/−, adam19 −/−; T−/−, adam9/12/15 −/− triple knockout; P, pro-form; M, mature.

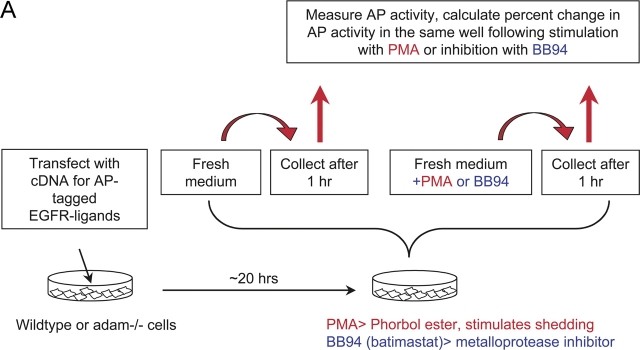

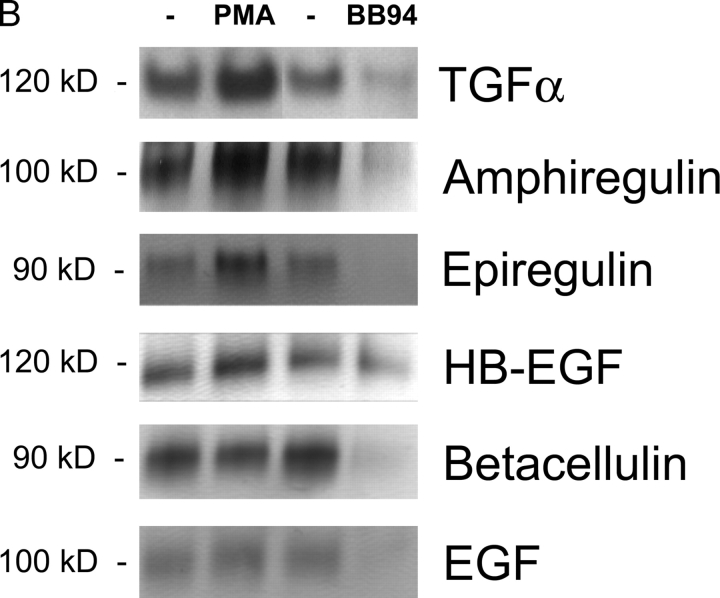

As differences in expression levels between tissue culture wells or separate experiments might affect the interpretation of these experiments, each data point was derived from two consecutive measurements of AP activity shed from a single transfected well (see Fig. 2 A). Stimulation of EGFR ligand shedding in a given well was determined by collecting medium after 1 h from unstimulated cells, and then after 1 h from the same cells stimulated with the phorbol ester PMA, a commonly used activator of ectodomain shedding (Massague and Pandiella, 1993; Hooper et al., 1997; see Fig. 3 A). This was used to calculate the increase in shedding in a given well during PMA stimulation. The batimastat-sensitive constitutive shedding was determined similarly, by measuring the decrease in AP activity in media collected after 1 h in the presence of batimastat and comparing it to the AP activity released from the same well collected 1 h before treatment (see Fig. 4 A). This single-well assay minimizes possible effects caused by different transfection levels. Nevertheless, the absolute values for constitutive shedding from different wild-type or primary adam −/− cells expressing a given EGFR ligand were also determined to provide a reference point for the comparison of total unstimulated shedding levels.

Figure 2.

Shedding of EGFR ligands in wild-type primary MEFs. (A) Diagram of a typical shedding experiment (see text for details). (B) Detection of shed AP-tagged EGFR ligands after renaturation in SDS gels (see Materials and methods for details). The left lane shows the AP-tagged forms of TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, HB-EGF, betacellulin, and EGF released in 1 h into the supernatant of a single well each of transfected mEF under resting conditions. The next lane shows the EGFR ligands released in 1 h from the same well after addition of PMA, a phorbol ester that stimulates ectodomain shedding. The third lane shows EGFR ligands released from a separate well in 1 h under resting conditions, and the fourth lane shows the released EGFR ligands in that same well after addition of the hydroxamate-based metalloprotease inhibitor batimastat (BB94).

Figure 3.

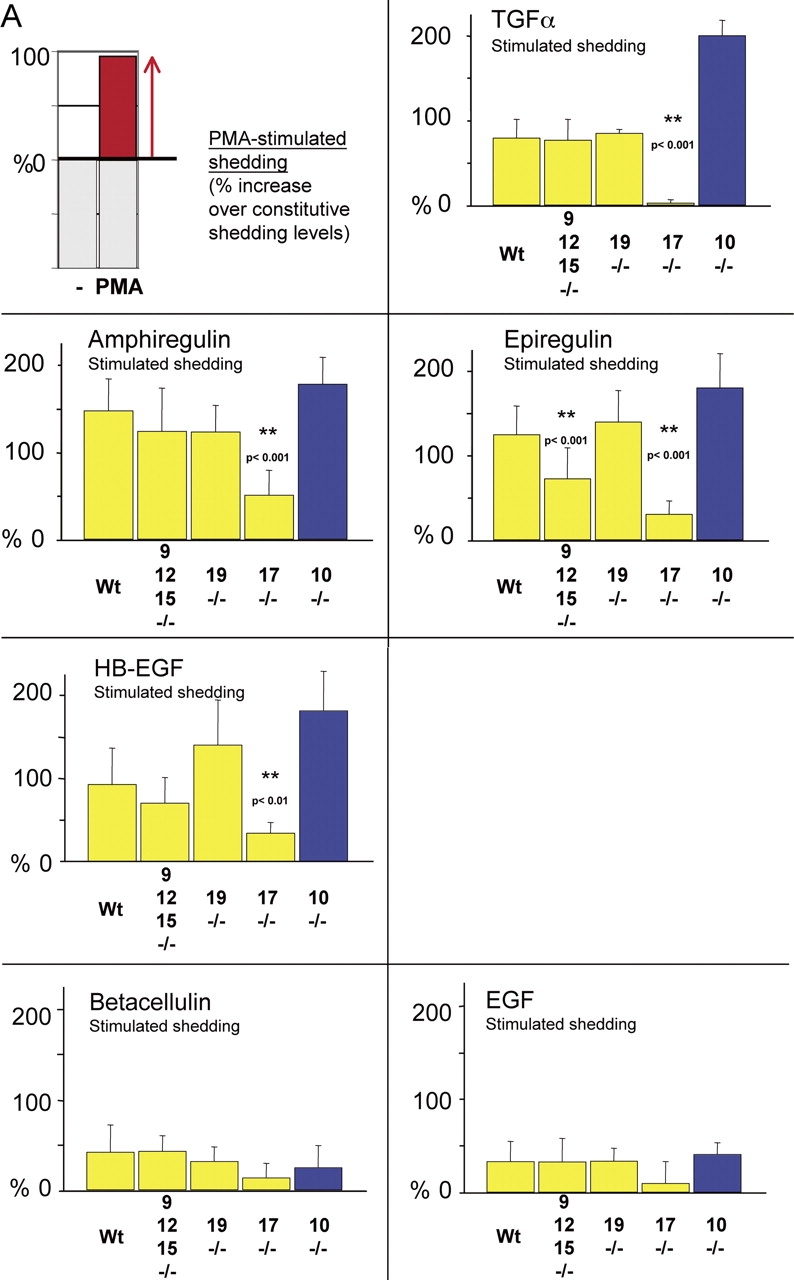

PMA-stimulated shedding of EGFR ligands in adam −/− cells. (A) The first panel shows an explanatory diagram depicting how increases in ectodomain shedding of different EGFR ligands from a given well are presented in the remaining panels of this figure. Shedding stimulated by 20 ng/ml PMA for 1 h is calculated as the percent increase in AP activity over constitutive shedding in the same well for 1 h. The next panels only show the PMA-dependent increase in shedding over constitutive levels for each EGFR ligand and each adam −/− cell type. Data from primary mEFs (yellow bars) are compiled from separate experiments using cells from three or more litters for each adam −/− mouse line. Only adam10 −/− and control adam10 +/− cells were immortalized (blue bars). Overall, at least four separate wells were evaluated per EGFR ligand. The results indicate that ADAM17 is the major stimulated sheddase for TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and HB-EGF. ADAMs 9, 12, or 15 (or a combination of two or more of these ADAMs) also contribute to stimulated epiregulin shedding. On the other hand, the shedding of betacellulin and EGF is only weakly stimulated by PMA. Because the increase in stimulated shedding is small, no statistically significant differences in stimulated shedding of betacellulin or EGF was seen in adam −/− cells compared with wild-type controls. (B) Histological analysis of sectioned hematoxylin and eosin–stained eyes and eyelids (A–D), aortic valves (E–H), pulmonic valves (I–L), and tricuspid valves (M–P) of newborn wild-type (A, E, I, and M), adam9/12/15 −/− (B, F, J, and N), adam17 −/− (C, G, K, and O), and adam9/12/15/17 −/− (D, H, L, and P) mice. Eyelids of wild-type and adam9/12/15 −/− mice are closed at birth (A and B), whereas those of adam17 −/− and adam9/12/15/17 −/− mice are open (C and D). The aortic, pulmonic, and tricuspid valves of adam9/12/15 −/− mice (F, J, and N) resemble those of wild-type mice (E, I, and M, respectively), whereas these valves are thickened and misshapen in adam17 −/− (G, K, and C) and adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mice (H, L, and P). The valve defects in adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mice, which also include thickened and misshapen mitral valves (not depicted), are comparable to those in adam17 −/− mice. Eyelids in A–D marked by red arrows, heart valves in E–P marked by yellow arrows. Bar (E–P), 100 μm.

Figure 4.

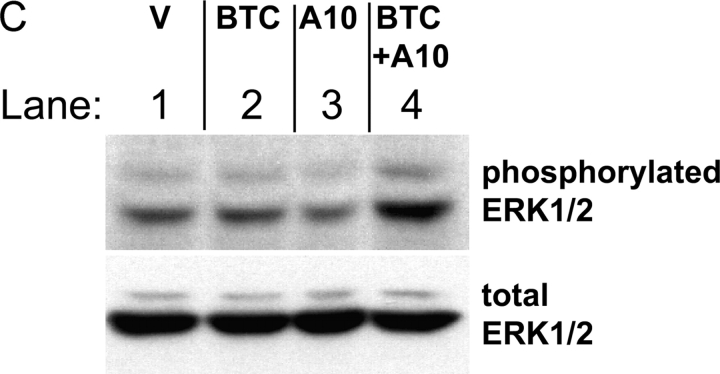

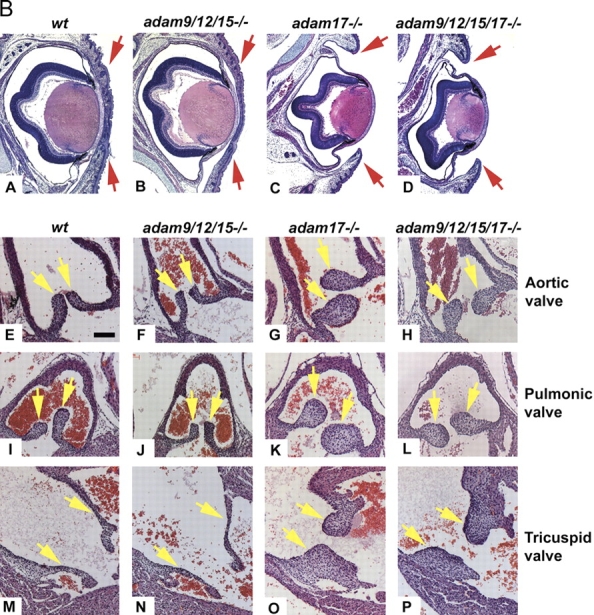

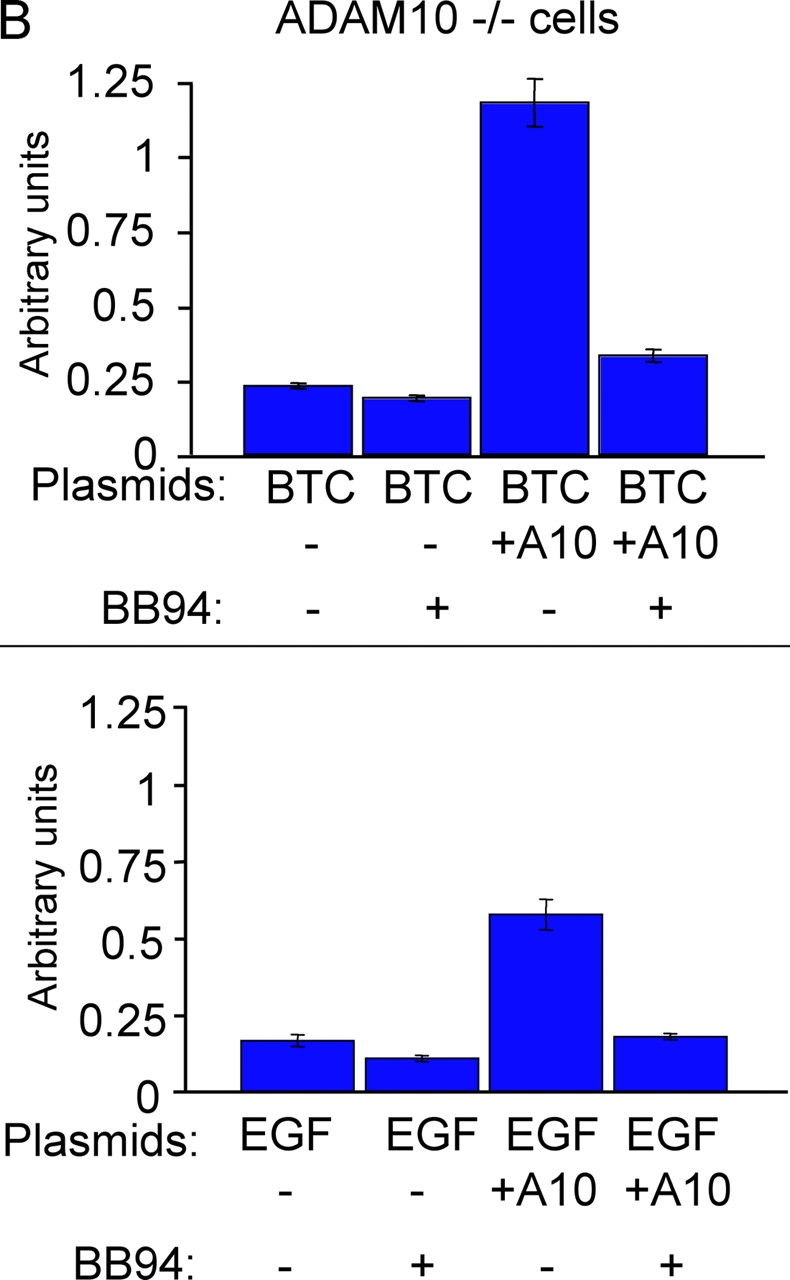

Batimastat-sensitive constitutive shedding of EGFR ligands in adam −/− cells. (A) A diagram indicating how the batimastat-sensitive component of ectodomain shedding of different EGFR ligands from a given well of resting cells was determined. Shedding of EGFR ligands in 1 h from resting cells is used as a reference to determine the percentage of batimastat-sensitive constitutive shedding (percent decrease after addition of batimastat). The next panels show the batimastat-sensitive decrease in shedding of each EGFR ligand in each adam −/− cell type. As in Fig. 3, separate experiments were performed with cells from three or more litters for each adam −/− mouse line. At least six separate wells were analyzed for adam10 −/− and control adam10 +/− cells, which were immortalized (blue bars). Several wells were evaluated in each experiment for each lot of cells and for each EGFR ligand. The results show that ADAMs 9, 10, 12, 15, and 19 are not essential for the batimastat-sensitive constitutive shedding of TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and HB-EGF. The absolute levels of constitutive release of each EGFR ligand were comparable between wild-type, adam9/12/15 −/−, and adam19 −/− cells (not depicted). However, the levels of constitutive shedding of TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and HB-EGF were significantly reduced in adam17 −/− cells compared with wild-type controls (see inset gel figures; SN, supernatant; CL, cell lysate), indicating that ADAM17 is also the major constitutive sheddase for these ligands. Data on the batimastat-sensitive shedding in adam17 −/− cells are not included in the graph because addition of batimastat further decreases the small amount of constitutive shedding in adam17 −/− cells. Thus, another metalloprotease besides ADAM17 apparently makes a very minor contribution to shedding of these four substrates. The batimastat-sensitive shedding of betacellulin and EGF was very similar in adam9/12/15 −/− , adam19 −/− , adam17 −/−, and adam10 +/− mEFs compared with wild-type controls. Although the absolute levels of constitutive shedding from these cells were also very similar (not depicted), constitutive shedding of betacellulin from adam10 −/− cells was decreased by 87.5%, whereas shedding of EGF was decreased by 49.7% compared with adam10 +/− cells. In the absence of ADAM10, the remaining small amount of constitutive shedding was not inhibitable by batimastat. (B) Batimastat-sensitive shedding of betacellulin (BTC) and EGF from adam10 −/− cells can be rescued by cotransfection with wild-type ADAM10 (A10; each bar represents the results from six tissue culture wells). These results confirm that the defect in EGF and betacellulin shedding in adam10 −/− cells is indeed due to the absence of ADAM10. (C) Constitutive phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in adam10 −/− cells transfected with the pcDNA3 vector (V, lane 1) is not increased by transfection with BTC (lane 2) or ADAM10 (lane 3). However, ERK1/2 phosphorylation is increased when BTC and ADAM10 are cotransfected (lane 4), demonstrating that ADAM10 is critical for BTC-dependent EGFR signaling in these cells. The bottom panel shows the same blot reprobed with antibodies against total ERK1/2 to confirm equal loading in all lanes.

Shedding of EGFR ligands in wild-type cells

Shedding of EGFR ligands was first evaluated in wild-type MEFs. As shown in Fig. 2 B, unstimulated mEFs shed basal amounts of TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, HB-EGF, betacellulin, and EGF. In the case of TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and HB-EGF, shedding was stimulated relatively strongly by PMA, whereas shedding of betacellulin and EGF was only weakly enhanced by PMA (see also Fig. 3 A). Treatment with the metalloprotease inhibitor batimastat strongly reduced both PMA-stimulated (unpublished data) and constitutive shedding of all EGF family members except HB-EGF. Although stimulated HB-EGF shedding was effectively inhibited by batimastat (unpublished data), constitutive release was only weakly affected (see also Fig. 4 A), suggesting that the predominant constitutive HB-EGF sheddase in primary mEFs is not a batimastat-sensitive metalloprotease, and is distinct from the sheddase(s) of other EGFR ligands.

PMA-stimulated shedding of EGFR ligands in adam − /− cells

The potential role of different ADAMs as EGFR ligand sheddases was then addressed in adam −/− mEFs. When we evaluated PMA-stimulated EGFR ligand shedding in triple knockout adam9/12/15 −/− cells, no significant decrease in the release of HB-EGF, TGFα, amphiregulin, EGF, or betacellulin compared with wild-type cells was observed (Fig. 3 A). However, there was a statistically significant reduction in stimulated shedding of epiregulin in adam9/12/15 −/− cells (41.8%), suggesting that one or more of these ADAMs contributes to stimulated epiregulin processing. Similarly, we found no evidence for a major role of ADAM19 in stimulated shedding of the EGFR ligands tested here (Fig. 3 A). The reason for the slight increase in HB-EGF shedding in adam19 −/− cells compared with wild-type controls remains to be determined.

ADAM17 has been implicated in the shedding of TGFα and HB-EGF in immortalized embryonic fibroblasts and primary keratinocytes (Peschon et al., 1998; Merlos-Suarez et al., 2001; Sunnarborg et al., 2002), and of amphiregulin in primary keratinocytes (Sunnarborg et al., 2002). Consistent with these results, we observed a significant reduction of PMA-induced shedding of TGFα (89%), amphiregulin (65.8%), and HB-EGF (58.1%) in adam17 −/− compared with wild-type mEFs (Fig. 3 A). Furthermore, shedding of epiregulin was also strongly decreased in adam17 −/− cells (75.7%), providing the first evidence for a critical role of ADAM17 in stimulated shedding of this EGFR ligand. For TGFα, amphiregulin, and epiregulin, PMA-dependent ectodomain shedding in adam17 −/− cells was increased when wild-type ADAM17 was cotransfected, confirming that the defect in PMA-dependent shedding is indeed due to loss of ADAM17 (unpublished data).

ADAM10 has been implicated in shedding of HB-EGF as part of a pathway for crosstalk between a GPCR and the EGFR (Lemjabbar and Basbaum, 2002; Yan et al., 2002). As shown in Fig. 3, PMA-stimulated shedding of HB-EGF, TGFα, amphiregulin, and epiregulin is not decreased in adam10 −/− cells, suggesting that ADAM10 is not required for the PMA-stimulated shedding of these EGFR ligands. The enhanced stimulated shedding of these EGFR ligands in adam10 −/− (Fig. 3 A) and adam10 +/− cells (unpublished data) compared with the primary mEFs is presumably a consequence of immortalization.

Generation of adam9/12/15/17 − /− quadruple knockout mice, and evaluation of PMA-stimulated EGFR ligand shedding in adam9/12/15/17 − /− cells

Although ADAM17 is essential for the majority of stimulated shedding of HB-EGF in mEF cells, a residual amount of PMA-stimulated HB-EGF shedding is seen in the absence of ADAM17. Could this residual shedding depend on ADAMs 9 or 12, both of which have been implicated in HB-EGF shedding, or on the related ADAM15? To address this issue, we generated quadruple knockout mice lacking ADAMs 9, 12, 15, and 17 (see Materials and methods for details). Similar to adam17 −/− mice, adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mice that were born had open eyes and died in the first day after birth. The percentage of adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout embryos at E18.5 generated by mating adam9 −/− 12 −/− 15 −/− 17 +/− parents was somewhat lower than the percentage of adam17 −/− embryos at E17.5–18.5 produced by mating adam17 +/− mice (Table III; Peschon et al., 1998).

To determine whether the loss of ADAMs 9, 12, and 15 exacerbates known defects in EGFR signaling in adam17 −/− mice, we performed a histopathological examination of wild-type, adam9/12/15 −/− , adam17 −/− , and adam9/12/15/17 −/− E18.5 embryos. As shown in Fig. 3 B (panels A–D), the open-eye phenotype in adam17 −/− mice that results from lack of TGFα activation (Peschon et al., 1998) is similar in adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mice, whereas it is not seen in adam9/12/15 −/− triple knockout mice. Furthermore, Jackson et al. (2003) have described a defect in morphogenesis of the semilunar heart valves and the tricuspid and mitral valves in adam17 −/− mice (Fig. 3 B, panels E–P; mitral valve not depicted), which resembles the thickened and misshapen valves seen in hb-egf −/− mice and in mice with a knock-in mutation that abolishes HB-EGF shedding (Iwamoto et al., 2003; Yamazaki et al., 2003). As shown in Fig. 3 B, the heart valves in adam9/12/15 −/− triple knockout mice are indistinguishable from those in wild-type mice, and again, the defects in heart valve morphogenesis in adam17 −/− mice are comparable to the defects in adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mice. A morphometric analysis of all heart valves of six adam9/12/15/17 −/− E18.5 embryos also did not show an increased size compared with six adam17 −/− E18.5 embryos (unpublished data). When we performed shedding experiments with adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mEFs, the residual amount of PMA-stimulated HB-EGF shedding was comparable to what is observed in adam17 −/− cells (percent increase in HB-EGF shedding after PMA stimulation in adam9/12/15/17 −/− mEF: 33.3 ± 26.5%, n = 16; four embryos, 2–6 wells analyzed per embryo); compared with 33.7 ± 12.9% in adam17 −/− mEF; Fig. 3 A). Together, these results argue against a significant contribution of ADAMs 9, 12, or 15 to the shedding of HB-EGF in these cells.

Constitutive shedding of EGFR ligands in adam − /− cells

Next, we evaluated the batimastat-sensitive component of constitutive shedding of EGFR ligands in the presence or absence of different ADAMs. No significant difference in the batimastat-sensitive constitutive shedding of all six ligands tested here was observed in adam9/12/15 −/− or adam19 −/− cells compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 4 A). Furthermore, constitutive shedding of TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and HB-EGF was also not affected in adam10 −/− cells.

Because the shedding assay used here relies on measurements of the percent increase (see above) or decrease in shedding after treatment compared with unstimulated shedding, it is important to ensure that the levels of unstimulated shedding are indeed similar in different adam −/− and wild-type cells. In experiments where wild-type cells were evaluated simultaneously with adam9/12/15 −/− or adam19 −/− cells, comparable amounts of each EGFR ligand analyzed here were released from unstimulated cells (unpublished data). However, the overall levels of constitutive shedding for TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and HB-EGF (but not EGF and betacellulin) were reduced in adam17 −/− cells compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 4 A, insets; unpublished data). This demonstrates that ADAM17 has a key role in both stimulated and constitutive shedding of these EGFR ligands.

Interestingly, when we measured the batimastat-sensitive constitutive shedding of EGF and betacellulin, we found that it was abrogated in two independent adam10 −/− cell lines compared with control adam10 +/− cells and the primary mEF cells (Fig. 4 A; unpublished data). This resulted in a strong decrease in overall unstimulated constitutive shedding of betacellulin (87.5%) and EGF (49.7%) from adam10 −/− cells compared with adam10 +/− cells (unpublished data). Constitutive shedding of betacellulin and EGF could be rescued with wild-type ADAM10, confirming that the defect in shedding in adam10 −/− cells is indeed due to the lack of ADAM10 (Fig. 4 B). Next, we evaluated the role of ADAM10 in betacellulin-dependent EGFR signaling in adam10 −/− cells. When either ADAM10 or betacellulin were introduced in adam10 −/− cells, there was no increase in phosphorylation of ERK1/2, a commonly used indicator for activation of the EGFR (Fig. 4 C). However, when wild-type ADAM10 was cotransfected with betacellulin in adam10 −/− cells, ERK1/2 phosphorylation was increased (Fig. 4 C). Thus, EGFR signaling via transfected betacellulin depends on the presence of functional ADAM10 in these cells. Together, these results are the first to identify the major sheddase for EGF and betacellulin in mouse embryonic cells, and thus also to uncover two novel substrates for ADAM10.

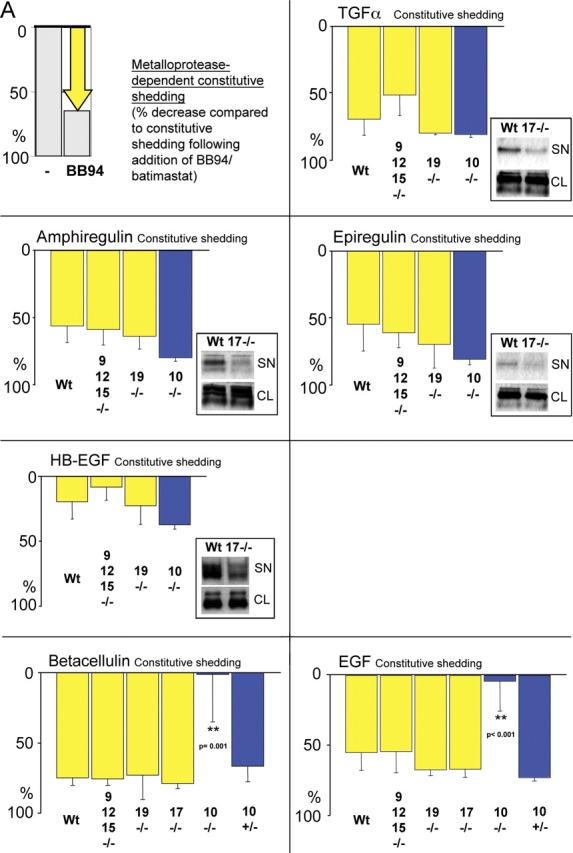

To address whether the results obtained in mEF cells could in principle also be relevant for other cells and tissues, Western blot analysis of the expression of ADAMs 10 and 17 in different mouse tissues was performed (Fig. 5). This confirmed that both ADAMs are widely expressed, even though their expression levels vary. Thus, it is likely that both ADAMs 10 and 17 are expressed in the cells and tissues in which the ligands analyzed in this paper exert their function as activators of EGFR signaling.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of ADAM10 and ADAM17 protein levels in different mouse tissues. Western blots of mouse tissue extracts were probed with a polyclonal antiserum against ADAM10 (A) or ADAM17 (B). Equal amounts of Con A–enriched glycoproteins from the following tissues were loaded per lane: brain (lane 1), skeletal muscle (lane 2), kidney (lane 3), heart (lane 4), lung (lane 5), spleen (lane 6), testis (lane 7), and liver (lane 8). The arrow indicates the position of ADAM10 in A, and of ADAM17 in B.

Discussion

Protein ectodomain shedding of EGFR ligands can be critical for their functional activation. All EGFR ligands analyzed in this paper are synthesized as membrane-anchored precursors, and were initially identified as soluble biologically active growth factors (Cohen, 1962, 1965; de Larco and Todaro, 1978; Todaro et al., 1980; Shoyab et al., 1989; Higashiyama et al., 1991; Shing et al., 1993; Toyoda et al., 1995). A key step in elucidating the mechanism underlying the proteolytic release of EGFR ligands is the identification of the responsible sheddases. Although ADAM17 has been implicated in the shedding of TGFα, HB-EGF, and amphiregulin (Merlos-Suarez et al., 2001; Sunnarborg et al., 2002; Jackson et al., 2003), no information was previously available about the identity of the sheddases for epiregulin, EGF, and betacellulin. Furthermore, three other ADAMs (9, 10, and 12) had been implicated in HB-EGF shedding (Izumi et al., 1998; Asakura et al., 2002; Lemjabbar and Basbaum, 2002), raising questions about their individual contributions to HB-EGF release. To test the hypothesis that the sheddases for epiregulin, EGF, and betacellulin are also ADAMs, and to further evaluate the contribution of different ADAMs to HB-EGF shedding, we studied the release of these proteins from cells lacking one or more members of this family of metalloproteases. Moreover, even though ADAM17 has been linked to the shedding of TGFα and amphiregulin, we included these EGFR ligands in our paper both to investigate whether other ADAMs may participate in the shedding of these two proteins and as a positive control to validate the assay used here. Finally, we determined the effects of targeted deletions of up to four ADAMs that are candidate sheddases (ADAMs 9, 12, 15, and 17) on mouse development.

Ectodomain shedding experiments using these six major EGFR ligands in adam −/− MEFs corroborated previous reports that ADAM17 has a major role in the shedding of TGFα, HB-EGF, and amphiregulin (Peschon et al., 1998; Merlos-Suarez et al., 2001; Sunnarborg et al., 2002). We found no evidence for a major contribution of other ADAMs besides ADAM17 to TGFα, HB-EGF, and amphiregulin shedding in these cells. Furthermore, epiregulin was identified as a novel ADAM17 substrate. Previous works have shown that adam17 −/− mice resemble tgfα 2/− mice (Peschon et al., 1998) in that they have open eyes at birth, as well as displaying similar vibrissae, hair, and skin defects (Mann et al., 1993). Furthermore, adam17 −/− mice also resemble hb-egf −/− mice (Iwamoto et al., 2003) in that they have thickened aortic and pulmonic valves (Jackson et al., 2003). A similar phenotype is seen in mice with a mutation in the cleavage site of HB-EGF that abolishes its shedding (Yamazaki et al., 2003). Finally, the phenotype of adam17 −/− mice resembles that of egfr −/− mice (Miettinen et al., 1995; Sibilia and Wagner, 1995; Threadgill et al., 1995; Peschon et al., 1998). Thus, genetic experiments have substantiated that ADAM17 is also essential for the activation of EGFR ligands in vivo. It remains to be determined whether the lack of processing of amphiregulin or epiregulin (or both) also contributes to the phenotype of adam17 −/− mice.

ADAMs 9, 10, and 12 are also considered candidate HB-EGF sheddases (Izumi et al., 1998; Asakura et al., 2002; Kurisaki et al., 2003). However, although PMA-stimulated ectodomain shedding of HB-EGF was somewhat reduced in adam9/12/15 −/− cells, this reduction was not statistically significant. In addition, the residual PMA stimulation of HB-EGF shedding in adam17 −/− cells is most likely also not due to ADAMs 9, 12, or 15 because it remains unchanged in adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout cells. In a previous paper, Kurisaki et al. (2003) reported a significant reduction in the down-regulation of cell-associated HB-EGF in phorbol ester–stimulated adam12 −/− cells compared with wild-type controls. This apparent discrepancy may be due to differences in cell preparation or experimental design. Nevertheless, the main conclusion from the side-by-side comparison of different adam −/− cells isolated and cultured under identical conditions in this paper is that ADAM17 is the predominant PMA-stimulated HB-EGF sheddase in primary mEF cells.

The conclusion that ADAM17 has a critical role in shedding HB-EGF in vivo was further corroborated by an analysis of the role of these ADAMs during mouse development. As mentioned previously in this paper, adam17 −/− mice resemble egfr −/− , tgfα2/−, or hb-egf −/− mice, whereas no similar defects were seen in adam9/12/15 −/− mice. Furthermore, the phenotype of adam17 −/− mice does not appear to be considerably exacerbated when ADAMs 9, 12, and 15 are also deleted. Together, these findings argue against major compensatory or redundant roles for ADAMs 9, 12, and the related ADAM 15 in the activation of TGFα, HB-EGF, or the EGFR during development. However, it cannot be ruled out that ADAMs 9, 12, or 15 contribute to shedding of EGFR ligands in cells or tissues where these enzymes and potential substrates are highly expressed. Further analyses will address which ADAMs are capable of cleaving EGFR ligands when overexpressed, and in which tissues candidate EGFR ligand sheddases besides ADAMs 10 and 17 are highly expressed together with EGFR ligands that they can cleave.

ADAM10 has also been implicated in HB-EGF shedding as part of a pathway that involves crosstalk between GPCRs and the EGFR (Lemjabbar and Basbaum, 2002; Yan et al., 2002; Lemjabbar et al., 2003). On the other hand, our results indicate that ADAM10 does not make a major contribution to PMA-stimulated or constitutive shedding of HB-EGF in the cells tested here. This is consistent with the notion that different stimuli may activate different ADAMs, such that HB-EGF shedding depends mainly on ADAM17 under the conditions used here, and mainly on ADAM10 when the appropriate GPCR is stimulated.

Little was previously known about the sheddases responsible for the release of EGF and betacellulin from cells. Here, we show that constitutive shedding of both EGF and betacellulin was strongly reduced in adam10 −/− cells compared with heterozygous controls, and could be rescued by reintroduction of wild-type ADAM10. Furthermore, stimulation of the EGFR by transfected betacellulin in adam10 −/− cells is only seen when these cells are rescued by cotransfection with wild-type ADAM10. These results are the first to identify ADAM10 as the major sheddase for these two crucial EGFR ligands in mouse cells. Because ADAM10 is widely expressed, it is tempting to speculate that it may participate in the functional regulation of these two EGFR ligands in development and in diseases such as cancer.

In light of the genetic evidence for a key role of ADAM17 in activation of EGFR ligands in mice (Peschon et al., 1998; Sunnarborg et al., 2002; Jackson et al., 2003), it is surprising that no ADAM has been identified as an essential part of the EGFR pathway in Drosophila (Lee et al., 2001; Urban et al., 2001; Ghiglione et al., 2002; Tsruya et al., 2002; Shilo, 2003). Instead, Rhomboids (integral membrane proteins with seven membrane-spanning domains) have been implicated in cleaving EGFR ligands (Urban et al., 2002), whereas reducing the expression of a putative ADAM17 orthologue in Drosophila via small interfering RNA did not block development of EGFR-dependent structures (Lee et al., 2001).

These results suggest that there are critical differences in the mechanism underlying proteolytic activation of EGFR ligands between flies and mice. However, the finding that all EGFR ligands tested here are processed by ADAM10 or ADAM17 in mEFs suggests a possible alternative explanation for these findings. Drosophila carry orthologues of ADAM10 (KUZ) and ADAM17 (AAF56986, the ADAM targeted by RNA interference in Lee et al. [2001]), as well as a third ADAM related to ADAM17 and KUZ with no evident orthologue in mammals (AAF56926). It is conceivable that two or three of these ADAMs fulfill redundant or compensatory roles in activation of EGFR ligands during development in Drosophila. This may only become apparent once two or three of these putative EGFR ligand sheddases are simultaneously inactivated. Conversely, the results in Drosophila suggest that it will be worthwhile to further investigate the potential role of Rhomboids and intramembrane proteolysis in EGFR ligand activation in mammals.

In summary, we report the first systematic analysis of the shedding of EGFR ligands in cells lacking one or more widely expressed and catalytically active ADAM. Our results uncover critical roles for both ADAM10 and ADAM17 in shedding of EGFR ligands in mEF cells. ADAM17 emerged as the major PMA-stimulated and constitutive sheddase of TGFα, amphiregulin, HB-EGF, and epiregulin, which is consistent with the essential role for ADAM17 in activation of the EGFR during development. Furthermore, ADAM10 was found to be the major batimastat-sensitive sheddase for betacellulin and EGF in mEF. Further experiments, including the generation of conditional adam10 −/− knockout mice, as well as knock-in mutations that abolish shedding of EGF and betacellulin, will be necessary to address the biological relevance of ADAM10 in shedding the endogenous forms of these EGFR ligands in vivo. The identification of different EGFR ligands as substrates for ADAM10 and ADAM17 sets the stage for the further analysis of how these ADAMs are regulated and how their substrate specificity is achieved. Because proteolysis of EGFR ligands may be critical for their functional activation, and signaling via the EGFR has been implicated in diseases such as cancer, ADAM10 and ADAM17 may be attractive targets for the design of drugs that modulate the action of these ligands.

Materials and methods

Generation of adam9/15 − /−, adam9/12/15 − /−, and adam9/12/15/17 − /− knockout mice

Mice lacking ADAMs 9, 12, or 15 have been described previously (Weskamp et al., 2002; Horiuchi et al., 2003; Kurisaki et al., 2003). To generate adam9/15 −/− double knockout mice, we mated adam9 +/− 15 +/− doubly heterozygous parents. This produced offspring in the expected Mendelian ratio (Table I). adam9/15 −/− double knockout mice were then mated with adam12 −/− mice (provided by Dr. Fujisawa-Sehara, University of Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan) to produce adam9 +/− 12 +/− 15 +/− triple heterozygous parents. These were backcrossed with adam9/15 −/− mice to generate adam9/15 −/− 12 +/− animals. When adam9/15 −/− 12 +/− mice were crossed, the ratio of offspring was Mendelian with respect to the mutant ADAM12 allele (Table II). Genotyping was performed by Southern blot as described previously (Weskamp et al., 2002; Horiuchi et al., 2003; Kurisaki et al., 2003). All animals used in this work were of mixed genetic background (129Sv/C57Bl6).

The histopathological analysis of adam9/15 −/− mice was performed as described previously for adam9 −/− or adam15 −/− mice (Weskamp et al., 2002; Horiuchi et al., 2003). Histopathological analysis of adam9/12/15 −/− mice was performed by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center mouse phenotyping core. No abnormalities or pathological phenotypes were observed in adam9/15 −/− and adam9/12/15 −/− mice. Serial sections of tissues affected in egfr −/− , hb-egf −/− , and tgfα2/− mice did not uncover any evident defects in adam9/12/15 −/− mice. Specifically, there were no defects in the development of the heart or its valves (Fig. 3 B, panels E–P), and also no defects in epithelia, intestine, lung, or in hair development. Finally, adam9/12 −/− double knockout and adam9/12/15 −/− triple knockout mice were indistinguishable from wild-type controls in their appearance and behavior during routine handling.

To generate adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mice, adam9/12/15 −/− triple knockout mice were mated with adam17 +/− animals. Offspring from this mating that were heterozygous for the targeted allele of all four ADAMs were identified by Southern blotting, and were backcrossed several times with adam9/12/15 −/− triple knockout mice to obtain adam9 −/− 12 −/− 15 −/− 17 +/− mice. Crosses of adam9 −/− 12 −/− 15 −/− 17 +/− mice produced litters with a similar distribution of the targeted ADAM17 allele at E18.5 to what has been reported from crosses of adam17 +/− mice (Table III; Peschon et al., 1998). Histopathological evaluation of newborn adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mice did not uncover any significant worsening of the developmental defects described for adam17 −/− mice. The cause for the slightly increased embryonic lethality of adam9/12/15/17 −/− mice compared with adam17 −/− mice (Table III) remains to be determined. Images of fixed and hematoxylin and eosin–stained heart sections mounted in Permount/Histoclear were acquired with Axiovision software via an Axiocam HRC camera mounted on an Axioplan2 microscope (software, camera, and microscope all from Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). The objective was a Plan-Neofluar 10×/0,30 (44 03 30; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) lens. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop® 7.0, and the surface area of heart valves in serial sections was measured using NIH Image 1.63 software.

Table III.

Offspring of matings of adam9/12/15 −/− 17 +/− parents

| Genotype of E18.5 embryos | Percent |

|---|---|

| 9−/−15−/−12−/−17+/+ | 36.7 (36) |

| 9−/−15−/−12−/−17+/− | 49.0 (48) |

| 9−/−15−/−12−/−17−/− | 14.3 (14) [4] |

| Genotype of E17.5–18.5 embryos | |

| 17+/+ | 23.3 (23) |

| 17+/− | 57.3 (59) |

| 17−/− | 20.4 (21) [4] |

Genotype of E18.5 embryos from matings of adam9 −/− 15 −/− 12 −/− 17 +/− parents. Numbers in parentheses, # (total of 98). Genotype of E17.5–18.5 embryos from matings of adam17 +/− parents, taken from Peschon et al. (1998). Numbers in parentheses, # (total of 103). Nonviable embryos are indicated in brackets.

Expression vectors for AP-tagged EGFR ligands

Plasmids encoding AP-tagged EGFR ligands were constructed by inserting partial cDNAs for human TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, EGF, betacellulin, and HB-EGF into the 3′ end of human placental AP cDNA on a pRc/CMV-based expression vector pAlPh. pAlPh contains an NH2-terminally located HB-EGF signal sequence. In all cases, the junction between AP and the EGFR ligand was placed next to the membrane-proximal EGF repeat. Release of the AP module into the culture supernatant thus requires cleavage at the COOH-terminal cleavage site. It should be noted that the results obtained with AP-tagged EGFR ligands corroborate previous results that TGFα, HB-EGF, and amphiregulin are cleaved by ADAM17 (Peschon et al., 1998; Merlos-Suarez et al., 2001; Sunnarborg et al., 2002; Jackson et al., 2003). This validates the use of AP tags to measure ectodomain shedding for these substrates. In addition, the use of an AP tag has been independently validated using the TNF family members TNFα and TRANCE/OPGL (Zheng et al., 2002; Chesneau et al., 2003). This strongly suggests that an AP tag, which provides a sensitive and quantitative means of measuring ectodomain shedding, should not interfere with the shedding properties of the other EGFR ligands tested here.

Generation of primary MEFs

Primary MEFs were generated from wild-type or adam −/− E13.5 embryos and were cultured as described previously (Weskamp et al., 2002). In addition to adam9/12/15 −/− triple knockout and adam9/12/15/17 −/− quadruple knockout mice, we also used adam17 −/− (Peschon et al., 1998) and adam19 −/− (Zhou et al., 2004) mice as well as wild-type controls of mixed genetic background (129Sv/C57Bl6) to generate the corresponding primary mEF cells. All genotyping was performed by Southern blot analysis. adam10 −/− fibroblast cell lines derived from E9.5 embryos have been described previously (Hartmann et al., 2002).

Northern blot analyses

Procedures for isolation of mRNA, gel electrophoresis, transfer to membranes, and generation of 32P-labeled cDNA probes of the indicated ADAMs under high stringency were described previously (Weskamp and Blobel, 1994).

Transfections and shedding assays

cDNA constructs encoding AP-EGFR ligand fusion proteins were transfected with LipofectAMINE™ (Invitrogen). Fresh Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) medium was added the next day, incubated for 1 h, and then replaced with fresh medium containing either 20 ng/ml PMA or 1 μM batimastat (provided by D. Becherer, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC), which was also collected after 1 h. Evaluation of AP activity by SDS-PAGE or by colorimetric assays was performed as described previously (Zheng et al., 2002). No AP activity was present in conditioned media of nontransfected cells.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis of the expression of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in MEFs and in different mouse tissues was performed as described previously (Weskamp et al., 1996). The blots were probed with a polyclonal antiserum against ADAM10 (CHEMICON International) and against ADAM17 (Schlöndorff et al., 2000).

Statistical analyses

t tests for two samples assuming equal variances were used to calculate the P values. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Atsuko Fujisawa-Sehara for providing adam12 −/− mice; to Drs. Valerie Chesneau, Roy Black, Graham Carpenter, and Peter Dempsey for critical comments on the manuscript; and to Thadeous Kacmarczyk for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1 GM65740 (to C.P. Blobel), by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center support grant NCI-P30-CA-08748, and by the Samuel and May Rudin Foundation, the DeWitt Wallace Fund, the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

Abbreviations used in this paper: ADAM, a disintegrin and metalloprotease; AP, alkaline phosphatase; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GPCR, G protein–coupled receptor; HB-EGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; TACE, TNFα-converting enzyme.

References

- Asakura, M., M. Kitakaze, S. Takashima, Y. Liao, F. Ishikura, T. Yoshinaka, H. Ohmoto, K. Node, K. Yoshino, H. Ishiguro, et al. 2002. Cardiac hypertrophy is inhibited by antagonism of ADAM12 processing of HB-EGF: metalloproteinase inhibitors as a new therapy. Nat. Med. 8:35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black, R.A., and J.M. White. 1998. ADAMs: focus on the protease domain. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10:654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell-Pages, M., F. Rojo, J. Albanell, J. Baselga, and J. Arribas. 2003. TACE is required for the activation of the EGFR by TGF-α in tumors. EMBO J. 22:1114–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann, R., P.B. Lindquist, M. Nagashima, W. Kohr, T. Lipari, M. Napier, and R. Derynck. 1989. Transmembrane TGF-α precursors activate EGF/TGF-α receptors. Cell. 56:691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesneau, V., D. Becherer, Y. Zheng, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and C.P. Blobel. 2003. Catalytic properties of ADAM19. J. Biol. Chem. 278:22331–22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. 1962. Isolation of a mouse submaxillary gland protein accelerating incisor eruption and eyelid opening in the new-born animal. J. Biol. Chem. 237:1555–1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. 1965. The stimulation of epidermal proliferation by a specific protein (EGF). Dev. Biol. 12:394–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Larco, J.E., and G.J. Todaro. 1978. Growth factors from murine sarcoma virus-transformed cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 75:4001–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, P.J., K.S. Meise, Y. Yoshitake, K. Nishikawa, and R.J. Coffey. 1997. Apical enrichment of human EGF precursor in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells involves preferential basolateral ectodomain cleavage sensitive to a metalloprotease inhibitor. J. Cell Biol. 138:747–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck, R., A.B. Roberts, M.E. Winkler, E.Y. Chen, and D.V. Goeddel. 1984. Human transforming growth factor-α: precursor structure and expression in E. coli. Cell. 38:287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J., L.K. Opresko, P.J. Dempsey, D.A. Lauffenburger, R.J. Coffey, and H.S. Wiley. 1999. Metalloprotease-mediated ligand release regulates autocrine signaling through the epidermal growth factor receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:6235–6240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiglione, C., E.A. Bach, Y. Paraiso, K.L. Carraway, III, S. Noselli, and N. Perrimon. 2002. Mechanism of activation of the Drosophila EGF receptor by the TGFα ligand Gurken during oogenesis. Development. 129:175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwind, A., S. Hart, O.M. Fischer, and A. Ullrich. 2003. TACE cleavage of proamphiregulin regulates GPCR-induced proliferation and motility of cancer cells. EMBO J. 22:2411–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R.C., E. Chung, and R.J. Coffey. 2003. EGF receptor ligands. Exp. Cell Res. 284:2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, D., B. de Strooper, L. Serneels, K. Craessaerts, A. Herreman, W. Annaert, L. Umans, T. Lubke, A. Lena Illert, K. von Figura, and P. Saftig. 2002. The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is essential for Notch signalling but not for α-secretase activity in fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11:2615–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama, S., J.A. Abraham, J. Miller, J.C. Fiddes, and M. Klagsbrun. 1991. A heparin-binding growth factor secreted by macrophage-like cells that is related to EGF. Science. 251:936–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, N.M., E.H. Karran, and A.J. Turner. 1997. Membrane protein secretases. Biochem. J. 321:265–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi, K., G. Weskamp, L. Lum, H.P. Hammes, H. Cai, T.A. Brodie, T. Ludwig, R. Chiusaroli, R. Baron, K.T. Preissner, et al. 2003. Potential role for ADAM15 in pathological neovascularization in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:5614–5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, R., S. Yamazaki, M. Asakura, S. Takashima, H. Hasuwa, K. Miyado, S. Adachi, M. Kitakaze, K. Hashimoto, G. Raab, et al. 2003. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor and ErbB signaling is essential for heart function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:3221–3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi, Y., M. Hirata, H. Hasuwa, R. Iwamoto, T. Umata, K. Miyado, Y. Tamai, T. Kurisaki, A. Sehara-Fujisawa, S. Ohno, and E. Mekada. 1998. A metalloprotease-disintegrin, MDC9/meltrin-gamma/ADAM9 and PKCdelta are involved in TPA-induced ectodomain shedding of membrane-anchored heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. EMBO J. 17:7260–7272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L.F., T.H. Qiu, S.W. Sunnarborg, A. Chang, C. Zhang, C. Patterson, and D.C. Lee. 2003. Defective valvulogenesis in HB-EGF and TACE-null mice is associated with aberrant BMP signaling. EMBO J. 22:2704–2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurisaki, T., A. Masuda, K. Sudo, J. Sakagami, S. Higashiyama, Y. Matsuda, A. Nagabukuro, A. Tsuji, Y. Nabeshima, M. Asano, et al. 2003. Phenotypic analysis of Meltrin α (ADAM12)-deficient mice: involvement of Meltrin α in adipogenesis and myogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.R., S. Urban, C.F. Garvey, and M. Freeman. 2001. Regulated intracellular ligand transport and proteolysis control EGF signal activation in Drosophila. Cell. 107:161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemjabbar, H., and C. Basbaum. 2002. Platelet-activating factor receptor and ADAM10 mediate responses to Staphylococcus aureus in epithelial cells. Nat. Med. 8:41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemjabbar, H., D. Li, M. Gallup, S. Sidhu, E. Drori, and C. Basbaum. 2003. Tobacco smoke-induced lung cell proliferation mediated by tumor necrosis factor α-converting enzyme and amphiregulin. J. Biol. Chem. 278:26202–26207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, G.B., K.J. Fowler, A. Gabriel, E.C. Nice, R.L. Williams, and A.R. Dunn. 1993. Mice with a null mutation of the TGF α gene have abnormal skin architecture, wavy hair, and curly whiskers and often develop corneal inflammation. Cell. 73:249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague, J., and A. Pandiella. 1993. Membrane-anchored growth factors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62:515–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlos-Suarez, A., S. Ruiz-Paz, J. Baselga, and J. Arribas. 2001. Metalloprotease-dependent protransforming growth factor-α ectodomain shedding in the absence of tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 276:48510–48517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, P.J., J.E. Berger, J. Meneses, Y. Phung, R.A. Pedersen, Z. Werb, and R. Derynck. 1995. Epithelial immaturity and multiorgan failure in mice lacking epidermal growth factor receptor. Nature. 376:337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon, J.J., J.L. Slack, P. Reddy, K.L. Stocking, S.W. Sunnarborg, D.C. Lee, W.E. Russel, B.J. Castner, R.S. Johnson, J.N. Fitzner, et al. 1998. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 282:1281–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenzel, N., E. Zwick, H. Daub, M. Leserer, R. Abraham, C. Wallasch, and A. Ullrich. 1999. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. 402:884–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primakoff, P., and D.G. Myles. 2000. The ADAM gene family: surface proteins with an adhesion and protease activity packed into a single molecule. Trends Genet. 16:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlöndorff, J., and C.P. Blobel. 1999. Metalloprotease-disintegrins: modular proteins capable of promoting cell-cell interactions and triggering signals by protein ectodomain shedding. J. Cell Sci. 112:3603–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlöndorff, J., J.D. Becherer, and C.P. Blobel. 2000. Intracellular maturation and localization of the tumour necrosis factor α convertase (TACE). Biochem. J. 347:131–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals, D.F., and S.A. Courtneidge. 2003. The ADAMs family of metalloproteases: multidomain proteins with multiple functions. Genes Dev. 17:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo, B.Z. 2003. Signaling by the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor pathway during development. Exp. Cell Res. 284:140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shing, Y., G. Christofori, D. Hanahan, Y. Ono, R. Sasada, K. Igarashi, and J. Folkman. 1993. Betacellulin: a mitogen from pancreatic beta cell tumors. Science. 259:1604–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoyab, M., G.D. Plowman, V.L. McDonald, J.G. Bradley, and G.J. Todaro. 1989. Structure and function of human amphiregulin: a member of the epidermal growth factor family. Science. 243:1074–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibilia, M., and E.F. Wagner. 1995. Strain-dependent epithelial defects in mice lacking the EGF receptor. Science. 269:234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan, L., J.G. Murison, R.L. Prestidge, M.A. Sleeman, J.D. Watson, and K.D. Kumble. 2001. Cloning and biological activity of epigen, a novel member of the epidermal growth factor superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 276:18265–18271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunnarborg, S.W., C.L. Hinkle, M. Stevenson, W.E. Russell, C.S. Raska, J.J. Peschon, B.J. Castner, M.J. Gerhart, R.J. Paxton, R.A. Black, and D.C. Lee. 2002. Tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme (TACE) regulates epidermal growth factor receptor ligand availability. J. Biol. Chem. 277:12838–12845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T., Q. Yan, and W.J. Lennarz. 1998. Complex, two-way traffic of molecules across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 273:10083–10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threadgill, D.W., A.A. Dlugosz, L.A. Hansen, T. Tennenbaum, U. Lichti, D. Yee, C. LaMantia, T. Mourton, K. Herrup, R.C. Harris, et al. 1995. Targeted disruption of mouse EGF receptor: effect of genetic background on mutant phenotype. Science. 269:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro, G.J., C. Fryling, and J.E. De Larco. 1980. Transforming growth factors produced by certain human tumor cells: polypeptides that interact with epidermal growth factor receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 77:5258–5262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumaru, S., S. Higashiyama, T. Endo, T. Nakagawa, J. Miyagawa, K. Yamamori, Y. Hanakawa, H. Ohmoto, K. Yoshino, Y. Shirakata, et al. 2000. Ectodomain shedding of epidermal growth factor receptor ligands is required for keratinocyte migration in cutaneous wound healing. J. Cell Biol. 151:209–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda, H., T. Komurasaki, D. Uchida, Y. Takayama, T. Isobe, T. Okuyama, and K. Hanada. 1995. Epiregulin. A novel epidermal growth factor with mitogenic activity for rat primary hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:7495–7500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsruya, R., A. Schlesinger, A. Reich, L. Gabay, A. Sapir, and B.Z. Shilo. 2002. Intracellular trafficking by Star regulates cleavage of the Drosophila EGF receptor ligand Spitz. Genes Dev. 16:222–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban, S., J.R. Lee, and M. Freeman. 2001. Drosophila rhomboid-1 defines a family of putative intramembrane serine proteases. Cell. 107:173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban, S., J.R. Lee, and M. Freeman. 2002. A family of Rhomboid intramembrane proteases activates all Drosophila membrane-tethered EGF ligands. EMBO J. 21:4277–4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weskamp, G., and C.P. Blobel. 1994. A family of cellular proteins related to snake venom disintegrins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:2748–2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weskamp, G., J.R. Krätzschmar, M. Reid, and C.P. Blobel. 1996. MDC9, a widely expressed cellular disintegrin containing cytoplasmic SH3 ligand domains. J. Cell Biol. 132:717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weskamp, G., H. Cai, T.A. Brodie, S. Higashyama, K. Manova, T. Ludwig, and C.P. Blobel. 2002. Mice lacking the metalloprotease-disintegrin MDC9 (ADAM9) have no evident major abnormalities during development or adult life. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1537–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.T., L.F. Winchell, B.K. McCune, H.S. Earp, J. Teixido, J. Massague, B. Herman, and D.C. Lee. 1989. The TGF-α precursor expressed on the cell surface binds to the EGF receptor on adjacent cells, leading to signal transduction. Cell. 56:495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, S., R. Iwamoto, K. Saeki, M. Asakura, S. Takashima, A. Yamazaki, R. Kimura, H. Mizushima, H. Moribe, S. Higashiyama, et al. 2003. Mice with defects in HB-EGF ectodomain shedding show severe developmental abnormalities. J. Cell Biol. 163:469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y., K. Shirakabe, and Z. Werb. 2002. The metalloprotease Kuzbanian (ADAM10) mediates the transactivation of EGF receptor by G protein–coupled receptors. J. Cell Biol. 158:221–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarden, Y., and M.X. Sliwkowski. 2001. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y., J. Schlöndorff, and C.P. Blobel. 2002. Evidence for regulation of the tumor necrosis factor α-convertase (TACE) by protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTPH1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:42463–42470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.M., G. Weskamp, V. Chesneau, U. Sahin, A. Vortkamp, K. Horiuchi, R. Chiusaroli, R. Hahn, D. Wilkes, P. Fisher, et al. 2004. Essential role for ADAM19 in cardiovascular morphogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]