Abstract

In the unfolded protein response, the type I transmembrane protein Ire1 transmits an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress signal to the cytoplasm. We previously reported that under nonstressed conditions, the ER chaperone BiP binds and represses Ire1. It is still unclear how this event contributes to the overall regulation of Ire1. The present Ire1 mutation study shows that the luminal domain possesses two subregions that seem indispensable for activity. The BiP-binding site was assigned not to these subregions, but to a region neighboring the transmembrane domain. Phenotypic comparison of several Ire1 mutants carrying deletions in the indispensable subregions suggests these subregions are responsible for multiple events that are prerequisites for activation of the overall Ire1 proteins. Unexpectedly, deletion of the BiP-binding site rendered Ire1 unaltered in ER stress inducibility, but hypersensitive to ethanol and high temperature. We conclude that in the ER stress-sensory system BiP is not the principal determinant of Ire1 activity, but an adjustor for sensitivity to various stresses.

Introduction

Folding, disulfide bond formation, subunit assembly, and core glycosylation of secretory and membrane proteins take place mainly in the ER. A variety of conditions, collectively called ER stress, inhibit these events and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR). The ER-located type I transmembrane protein Ire1 is a key molecule for the UPR (Cox et al., 1993; Mori et al., 1993). Ire1 is dimerized and activated in response to ER stress (Shamu and Walter, 1996; Bertolotti et al., 2000). The COOH terminus of Ire1 possesses an RNase activity, which in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae acts to splice HAC1 precursor mRNA to produce the mature form (Cox and Walter, 1996; Sidrauski and Walter, 1997). The mature HAC1 mRNA is effectively translated into a functional transcription factor that induces various genes including those encoding ER-resident molecular chaperones and protein-folding catalysts (Mori et al., 2000; Travers et al., 2000; Ruegsegger et al., 2001). A promoter element named the UPR element (UPRE), to which the Hac1 protein directly binds, was identified on some of these genes, such as KAR2, which encodes the ER-resident HSP70 chaperone BiP (Mori et al., 1992, 1996; Kohno et al., 1993).

In mammalian cells, the UPR seems to be driven by more complicated pathways. Two paralogues of Ire1, Ire1α and Ire1β, have been identified (Tirasophon et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1998; Iwawaki et al., 2001) and were reported to contribute to splicing of XBP1 mRNA, the mature form of which is translated into a highly active transcription factor protein (Yoshida et al., 2001; Calfon et al., 2002). In addition to this Ire1-XBP1 signaling pathway, another pathway involving the membrane-anchored transcription factor ATF6 also functions in transcriptional induction in response to ER stress (Haze et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2002). Moreover, ER stress attenuates bulk protein synthesis. This is caused by phosphorylation of a eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit by PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), a transmembrane kinase containing an Ire1-like luminal domain, and by cleavage of 28S rRNA by Ire1β (Harding et al., 1999; Iwawaki et al., 2001).

Little is known about the functions of the ER-luminal domain of Ire1, with the exception that it is highly possible that BiP binds to Ire1 to repress its activity under nonstressed conditions. The BiP association with Ire1, together with dissociation in response to ER stress, has been reported by Bertolotti et al. (2000) in mammalian cells and by us in yeast cells (Okamura et al., 2000). The finding that overexpression of BiP attenuates the UPR implies a role for BiP as a negative regulator of Ire1 (Kohno et al., 1993; Okamura et al., 2000). Our mutation study of the KAR2 gene seems to provide further evidence that this association and dissociation controls the activity of Ire1 (Kimata et al., 2003). The UPR pathway was constitutively activated in yeast strains with kar2 alleles encoding mutant BiP proteins that cannot bind to Ire1. And reversely, the UPR pathway was only weakly activated even by the potent ER stressor tunicamycin in strains with kar2 alleles encoding mutant BiP proteins of which dissociation from Ire1 is impaired. However, considering the multiple and essential roles of BiP in protein translocation and folding in the ER (Gething, 1999), it should be noted that the aberration of the UPR in the kar2 strains may be caused not directly by the impaired association or dissociation of BiP from Ire1, but by alterations in the ER stress status in the kar2 mutants.

How does the binding of BiP to Ire1 contribute to overall regulation of Ire1 in response to ER stress, and by which mechanism does BiP dissociate from Ire1? A simple working model hypothesizes that unfolded proteins produced by ER stress competitively deprive Ire1 of BiP, which is sufficient for activation of Ire1. In this scenario, BiP is considered to be the primary determinant of Ire1 activity, and Ire1 itself does not directly function to sense ER stress or to release BiP.

Here, we present an in vivo mutation study of the yeast S. cerevisiae IRE1 gene, which disproves this idea. The BiP dissociation from Ire1 seemed to require the function of an Ire1 subdomain that is structurally independent of the BiP-binding site. Moreover, deletion of the BiP-binding site was not sufficient to activate Ire1. Our findings imply that Ire1 itself possesses the ability to sense various stresses. The role of BiP suggested in this paper is to confine the activation of Ire1 to specifically respond to ER stress.

Results

Subregion structure prediction of the Ire1 luminal domain

At the beginning of this work, we performed 10-amino acid deletion scanning mutagenesis of the yeast Ire1 luminal region. As described in Materials and methods, overlap PCR and in vivo gap repair techniques (Ho et al., 1989; Muhlrad et al., 1992) were used to generate cells with centromeric plasmid-borne expression of mutant Ire1. The scanning resulted in the first deletion from amino acid position 25 to 34, the second deletion from 35 to 44, the third deletion from 45 to 54, and 46 additional serial deletions ending at the juxtamembrane position (Table S1 and Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/jcb.200405153/DC1; to number nucleotide and amino acid positions, we set the initiation Met site of Ire1 as described in an entry [AAB68894; Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ire1p] of the NCBI protein database). All of the scanning mutants carried 10-aa deletions, except that the 19th, 29th, and 39th mutants were generated to carry 11-aa deletions. Each mutant was named by the amino acid position at which the deletion began (for instance, the first mutant was named Δ25).

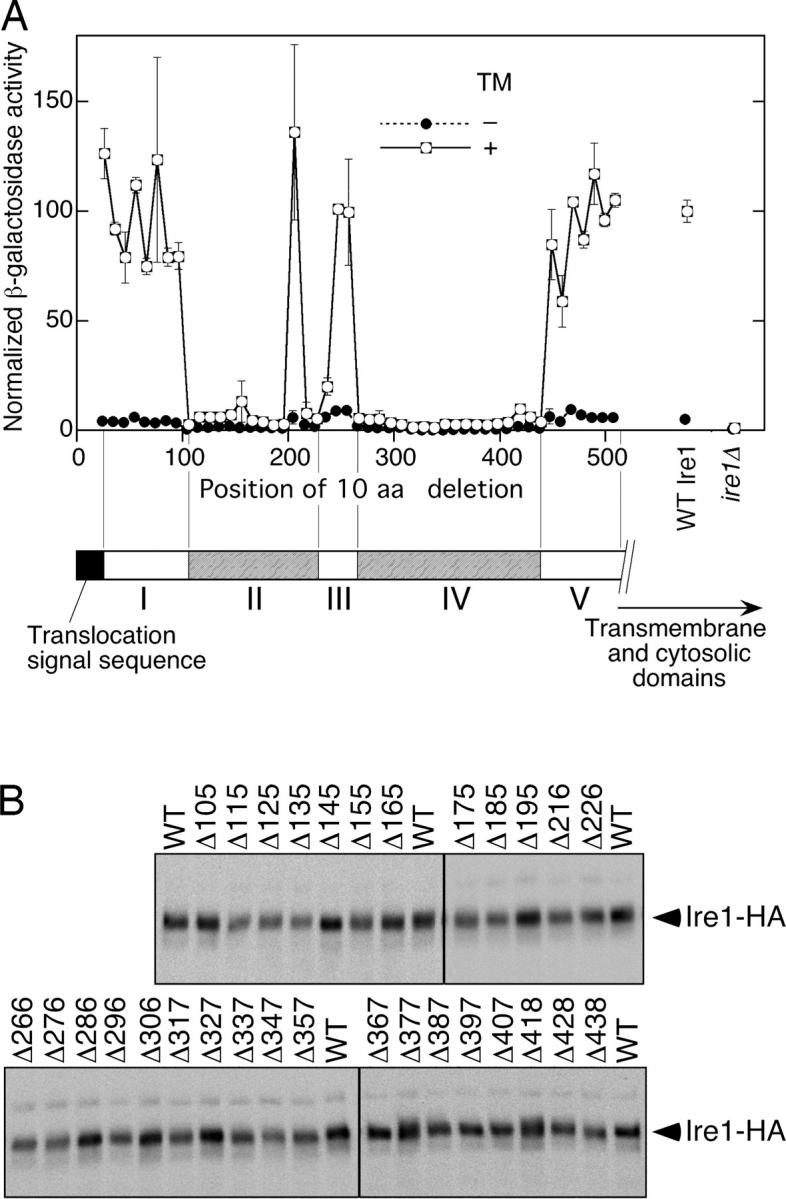

In Fig. 1 A, cellular UPR activity was estimated by expression of a lacZ reporter controlled by the UPRE-driven promoter (Mori et al., 1992). Cells producing the intact Ire1 protein (Fig. 1 A, WT Ire1) showed a clear UPR that was induced by tunicamycin. The tunicamycin inducibility was well preserved with mutations Δ25 to Δ95, Δ205, Δ246, Δ256, and Δ448 to Δ508, and partially with the Δ236 mutation. In contrast, little or no UPR was observed in cells carrying the mutations Δ105 to Δ195, Δ216, Δ226, or Δ266 to Δ438. As determined by Western blot detection of the COOH-terminal influenza virus HA-epitope tag, the steady-state expression of the Ire1 proteins was not significantly affected by most of the deletions that abolished the tunicamycin inducibility (Fig. 1 B), suggesting that these deletions diminished function rather than stability of Ire1. It should be noted that none of the scanning mutants rendered Ire1 constitutively active.

Figure 1.

10-aa deletion scanning of yeast Ire1. The Δire1 strain KMY1015 harboring the UPRE-lacZ reporter plasmid pCZY1 was transformed with a mixture of linearized pPR315-IRE1-HA (a centromeric plasmid for expression of COOH-terminal HA-tagged Ire1) and a partial fragment of the IRE1 gene carrying the desired deletion. The transformants carrying the successfully gap-repaired plasmid were selected and used. For the wild-type Ire1 (WT Ire1 or WT) and empty vector (Δire1) controls, cells were respectively transformed with nonlinearized pRS315-IRE1-HA and pPR315. (A) Cells were cultured with (+) or without (−) 2 μg/ml tunicamycin (TM) for 240 min and subjected to assays for cellular β-galactosidase activity. Each value is the average of three independent transformants and was normalized to the TM+ wild-type Ire1 control, which was set at 100. (B) Lysates prepared from 3 × 106 nonstressed cells using denaturing lysis buffer were analyzed by anti-HA Western blotting.

Based on the phenotypes of amino acid deletions shown in Fig. 1 A, we predicted five subregions in the Ire1 luminal domain. Subregion I corresponded approximately to amino acid position 25 to 104, subregion II to amino acid position 105 to 235, subregion III to amino acid position 236 to 265, subregion IV to amino acid position 266 to 447, and subregion V to amino acid position 448 to 517.

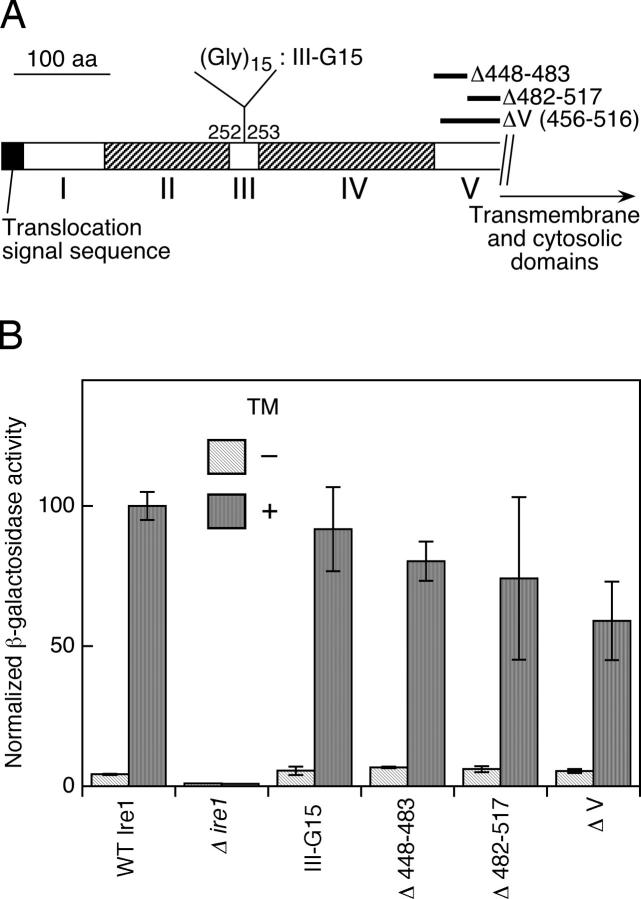

An insertion mutant shown in Fig. 2 A supports our prediction that the “functionally indispensable” region is structurally divided into subregion II and IV. As described in the online supplemental Materials and methods, we generated an Ire1 mutant with a (Gly)15 spacer insertion in subregion III (named III-G15), and found this mutant functioned almost as well as wild type to activate the UPR pathway (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

Activity of Ire1 luminal-domain mutants other than those used in the 10-aa deletion scanning. (A) The insertion and deletions carried on the mutants. III-G15 is a (Gly)15 spacer insertion in subregion III, and Δ448−483, Δ482−517, and ΔV are wide-range deletions in subregion V. (B) KMY1015 (Δire1) cells carrying both pCZY1 (UPRE-lacZ reporter) and a mutant version of pRS315-IRE1-HA were cultured with (+) or without (−) 2 μg/ml tunicamycin (TM) for 240 min and subjected to assays for cellular β-galactosidase activity. For the wild-type Ire1 (WT Ire1) and empty vector (Δire1) controls, cells were respectively transformed with nonlinearized pRS315-IRE1-HA and pPR315. Each value is the average from three independent transformants and was normalized to the TM+ wild-type Ire1 control, which was set at 100.

The BiP-binding site is in subregion V

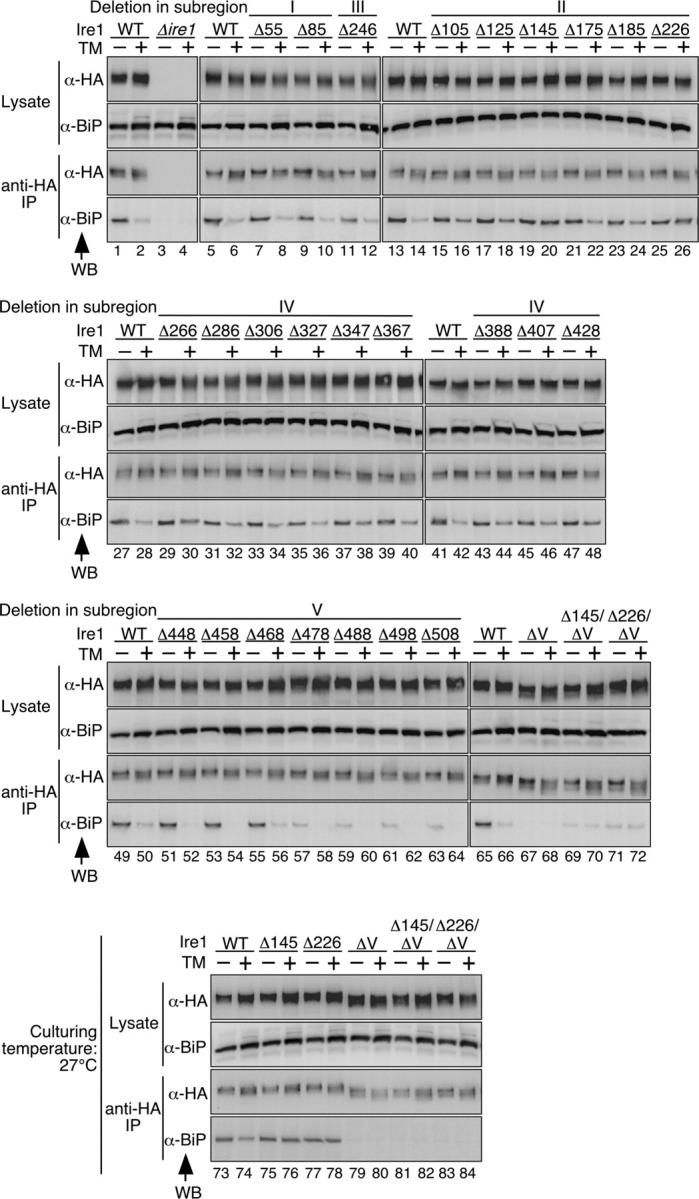

To demonstrate BiP binding to Ire1 in vivo, COOH-terminal HA-tagged Ire1 and its mutants were expressed from 2 μm plasmids, and their interaction with BiP was analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation. As described in Okamura et al. (2000), our 2-μm plasmid expression of HA-tagged Ire1 preserved ER stress inducibility and did not result in constitutive activation of the UPR pathway. Indeed, Northern blot analysis shows that in cells carrying the wild-type version of pRS423-IRE1-HA, high (80%) and very weak (< 5%) cleavage of HAC1 mRNA occurred after 60-min incubation of cells with and without 2 μg/ml tunicamycin, respectively. In the experiment shown in Fig. 3, cells were lysed under nondenaturing conditions before anti-HA immunoprecipitation, and the resulting lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by anti-HA or anti-BiP Western blotting. 25 out of the 49 deletion scanning mutants were analyzed in this experiment.

Figure 3.

BiP binding and dissociation from deletion mutants of Ire1. The Δire1 strain KMY1516 was transformed with a mixture of linearized pRS423-IRE1-HA-HpaI and a partial fragment of the IRE1 gene carrying the desired deletion generated by overlap PCR. The transformants carrying successfully gap-repaired plasmids (deletion mutant versions of pRS423-IRE1-HA, which is a 2-μm plasmid used for expression of Ire1-HA) were selected and cultured with (+) or without (−) 2 μg/ml tunicamycin (TM) for 60 min. The culturing temperature was 27°C for lanes 73–84 or 30°C for other lanes. For the empty vector (Δire1) and wild-type Ire1 (WT) controls, cells were respectively transformed with nonlinearized pRS423 and pPR423-IRE1-HA. Anti-HA immunoprecipitation was performed as described in Materials and methods, and the cell lysates (equivalent to 3 × 106 cells) and immunoprecipitates (equivalent to 1 × 107 cells) were analyzed by anti-HA (α-HA) and anti-BiP (α-BiP) Western blotting (WB).

Anti-HA Western blotting showed that the mutations did not cause significant changes in Ire1 expression levels (Fig. 3, Lysate, WB: α-HA) and that anti-HA immunoprecipitation trapped the wild-type and mutant Ire1 proteins with almost equal efficiency (Fig. 3, anti-HA IP, WB: α-HA). In this and the later figures, migration of epitope-tagged Ire1 and its deletion mutants on SDS-PAGE was smeary and altered by treatment of cells with tunicamycin. We think that this was caused by heterogeneity of N-glycosylation, which was enhanced by the N-glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin, because Ire1 mutants with amino acid replacements at all potential N-glycosylation sites showed sharp migration patterns on SDS-PAGE, which were not altered by treatment of cells with tunicamycin (unpublished data). In addition, the heterogeneity of N-glycosylation does not affect the activity of Ire1 because N-glycosylation mutants of Ire1 functioned normally to activate the UPR pathway in response to ER stress (Liu et al., 2000; unpublished data).

In anti-BiP Western blots of the immunoprecipitates, the WT lanes in Fig. 3 (lanes 1, 5, 13, 27, 41, 49, and 65) show BiP binding to the intact Ire1 protein under nonstressed conditions, and consistent with our previous reports (Okamura et al., 2000; Kimata et al., 2003), the amount of coimmunoprecipitated BiP was sharply reduced after treatment of cells by tunicamycin (Fig. 3, lanes 2, 6, 14, 28, 42, 50, and 66). This BiP binding and dissociation from Ire1 did not seem to be affected by deletions in subregion I, as represented by Δ55 and Δ85, or a subregion-III deletion, Δ246 (Fig. 3, lanes 7–12). This finding is consistent with the observation in Fig. 1 A, which indicates these deletions do not cause significant alteration in the function of Ire1.

A remarkable finding shown in Fig. 3 is that the binding of BiP to Ire1 was significantly diminished by some of the deletions in subregion V. To map the position contributing the interaction with BiP in subregion V, all of the subregion-V deletions were analyzed. The 10-aa deletions in the former half of subregion V (Δ448, Δ458, and Δ468) did not cause a significant change from the wild type in BiP binding or dissociation (Fig. 3, lanes 51–56). On the contrary, the deletions in the latter half of subregion V (Δ478 to Δ508) remarkably diminished the amount of coimmunoprecipitated BiP, which was still reduced by treatment of the cells with tunicamycin (Fig. 3, lanes 57–64). BiP binding seemed to be completely abolished only when almost the entire sequence of subregion V was deleted (ΔV; Fig. 3, lanes 67, 68, 79, and 80; see Fig. 2 A for the position). Unexpectedly, all of the deletions in subregion V, including ΔV, did not render Ire1 constitutively active, but preserved tunicamycin inducibility (Fig. 1 A and Fig. 2).

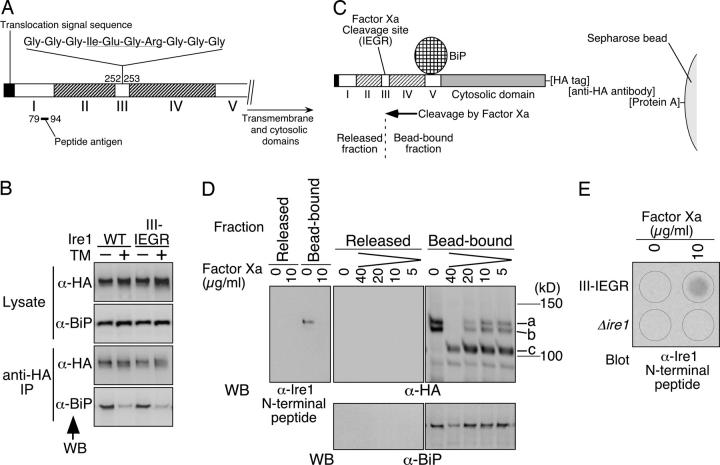

Another approach to determine the BiP-binding site on Ire1 was restricted proteolysis of the BiP-bound Ire1 protein. In this experiment, an HA-tagged version of an Ire1 mutant carrying an insertion of the Factor Xa cleavage site (Ile-Glu-Gly-Arg) in subregion III (Ire1 III-IEGR; Fig. 4 A) was expressed in yeast cells. Tunicamycin treatment of cells and subsequent anti-HA immunoprecipitation indicated that the III-IEGR mutation did not cause a change from the wild type in BiP binding or dissociation in vivo (Fig. 4 B). Nonstressed cells producing III-IEGR Ire1 were subjected to anti-HA immunoprecipitation, and the immunoprecipitate, the constituents of which were deduced as illustrated in Fig. 4 C, was used for the following proteolytic cleavage analysis. As shown by anti-HA Western blotting (Fig. 4 D), treatment with Factor Xa diminished the full-length (Fig. 4 D, a) and slightly truncated (Fig. 4 D, b) Ire1 proteins and yielded an ∼105-kD version (Fig. 4 D, c) in the bead-bound fraction. The migration on SDS-PAGE was consistent with the deduced size of the COOH-terminal fragment produced by the Factor Xa cleavage (101 kD), and, as expected, this protein was undetectable with an Ire1 NH2-terminal antibody that clearly detects the full-length Ire1 (Fig. 4 D, WB: α-Ire1 NH2-terminal peptide). We could not detect the NH2-terminal fragment (deduced to be 25 kD) in either the bead-bound fraction or in the released fraction by the anti-Ire1 NH2-terminal Western blot analysis (unpublished data), probably because this fragment was further cleaved nonspecifically. The presence of the NH2-terminal fragment in the released fraction was indicated by the dot blot analysis shown in Fig. 4 E. The anti-BiP Western blot shown in Fig. 4 D indicates that the amount of BiP in the bead-bound fraction was not diminished by Factor Xa cleavage, except that signals of both Ire1-HA and BiP were reduced by nonspecific proteolysis at 40 μg/ml of Factor Xa. This finding strongly suggests that the BiP-binding site is in the COOH-terminal fragment. Based on this proteolysis experiment and the aforementioned analysis of the deletion mutants, we have concluded that the BiP-binding site lies in subregion V.

Figure 4.

Proteolytic cleavage of Ire1 to assign the BiP-binding site. (A) The III-IEGR mutation in Ire1. The Factor Xa cleavage sequence is underlined. The position of the sequence against which the anti-Ire1 NH2-terminal peptide antibody was generated is also indicated. (B) The Δire1 strain KMY1516 carrying pPR423-IRE1-HA (WT) or its III-IEGR version was cultured with (+) or without (−) 2 μg/ml tunicamycin (TM) for 60 min. Anti-HA immunoprecipitation was performed as described in Materials and methods, and the cell lysates (equivalent to 3 × 106 cells) and immunoprecipitates (equivalent to 1 × 107 cells) were analyzed by anti-HA and anti-BiP Western blotting (WB). (C–E) Proteolytic cleavage analysis. KMY1516 cells carrying the III-IEGR version of pPR423-IRE1-HA were subjected to anti-HA immunoprecipitation, and 15 μl of the resulting immunoprecipitate (equivalent to 1 × 108 cells), the constituents of which were deduced as illustrated in C, was incubated with the indicated concentration of Factor Xa as described in Materials and methods. Note that in C the BiP-binding site is set in subregion V, as concluded in this work. In D, one-tenth portions of the resulting bead-bound and released fractions were fractionated by SDS-PAGE (8%) followed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies, and ECL signals were detected by LAS-1000plus (exposure time of 20 s for anti-BiP, 15 s for anti-HA, and 10 s for the anti-Ire1 NH2-terminal peptide). The positions of the full-length (a), slightly truncated (b), and Factor Xa-cleaved (c) Ire1-HA are indicated. Note that the slight truncation of Ire1-HA occurred independently of Factor Xa in Factor Xa cleavage buffer. In E, anti-HA immunoprecipitate from KMY1516 cells carrying the empty vector pRS423 was used as a negative control (Δire1), and one-third portions of the released fractions were subjected to dot blotting using antibody against the anti-Ire1 NH2-terminal peptide.

Ire1 seems to function positively in the dissociation from BiP

As described in the Introduction and Discussion, there is a simple hypothesis that does not require a positive contribution of Ire1 for its dissociation from BiP in response to ER stress. Another finding shown in Fig. 3 seems to provide counterevidence for this idea. This finding is that most of the deletion mutants in subregions II and IV showed less sharp dissociation of BiP than wild-type Ire1 after treatment of cells with tunicamycin (Fig. 3, lanes 15–26, 29–40, and 43–48). In particular, two of the deletions in subregion II, Δ145 and Δ226, rendered Ire1 constitutive in binding to BiP. The double deletion mutants, Δ145/ΔV and Δ226/ΔV, showed reduced binding to BiP even under nonstressed cells (Fig. 3, lanes 69–72). We speculate that the residual binding of BiP to Δ145/ΔV and Δ226/ΔV Ire1 observed in lanes 69–72 of Fig. 3 was caused by partial and local unfolding of the Ire1 molecules. When cells were cultured at a lower temperature (27°C), this residual binding of BiP was not observed (Fig. 3, lanes 81–84), whereas Δ145 and Δ226 single mutants still bound to BiP constitutively (Fig. 3, lanes 75–78). Thus in the Δ145 and Δ226 mutants, BiP probably binds to the same site as wild-type Ire1. These findings suggest that subregion II, and possibly also subregion IV, function in the dissociation of BiP from subregion V.

Another interpretation for impaired dissociation of BiP from the Δ145 and the Δ226 mutants is that the protein folding of Ire1 was globally perturbed by these mutations, which caused targeting of BiP to the Ire1 mutants by a rather nonspecific mechanism. The following observations in Figs. 5 and 6 suggest that this interpretation is unlikely.

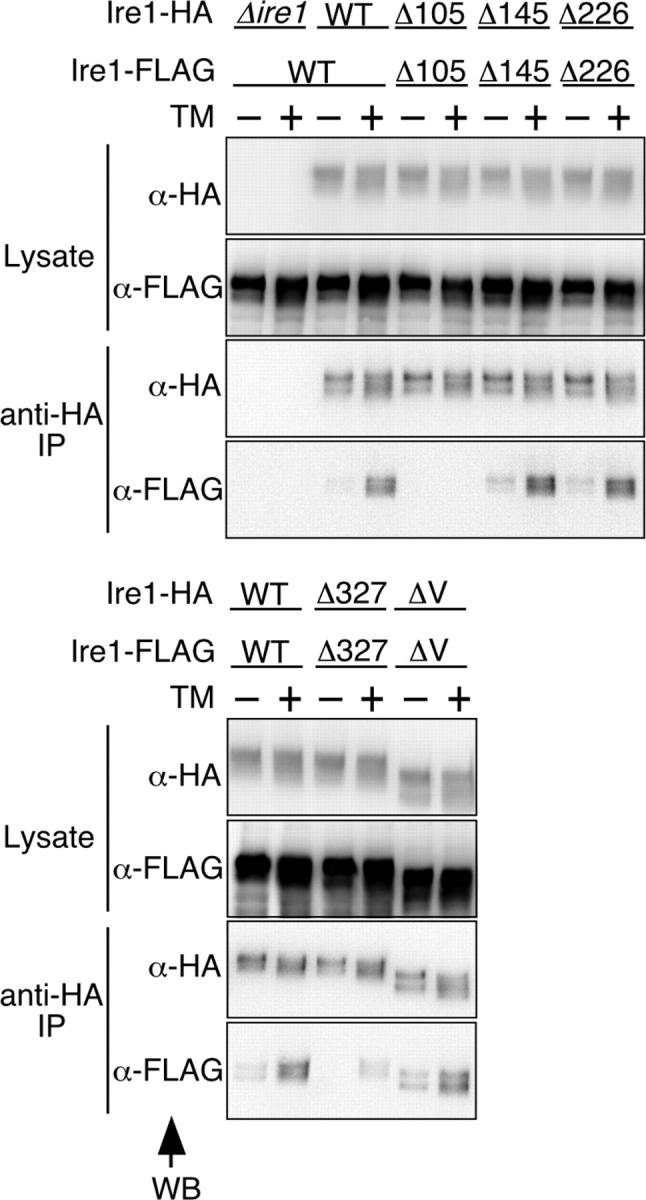

Figure 5.

Dimer formation of deletion mutants of Ire1. The Δire1 strains KMY1015 (MATα) and KMY1520 (MATa) respectively carrying deletion mutant versions of pRS315-IRE1-HA and pRS426-IRE1-FLAG, which is a 2-μm plasmid used for expression of Ire1-FLAG, were crossed to obtain diploid cells. For the empty vector control (Δire1), cells carrying pRS315 were used. The resulting diploid cells were cultured with (+) or without (−) 2 μg/ml tunicamycin (TM) for 60 min, and subjected to anti-HA immunoprecipitation as described in Materials and methods. The cell lysates (equivalent to 3 × 106 cells) and immunoprecipitates (equivalent to 1 × 107 cells) were analyzed by anti-HA (α-HA) and anti-FLAG (α-FLAG) Western blotting (WB; ECL signals were detected by LAS-1000plus with exposure time of 20 s to 1 min).

Figure 6.

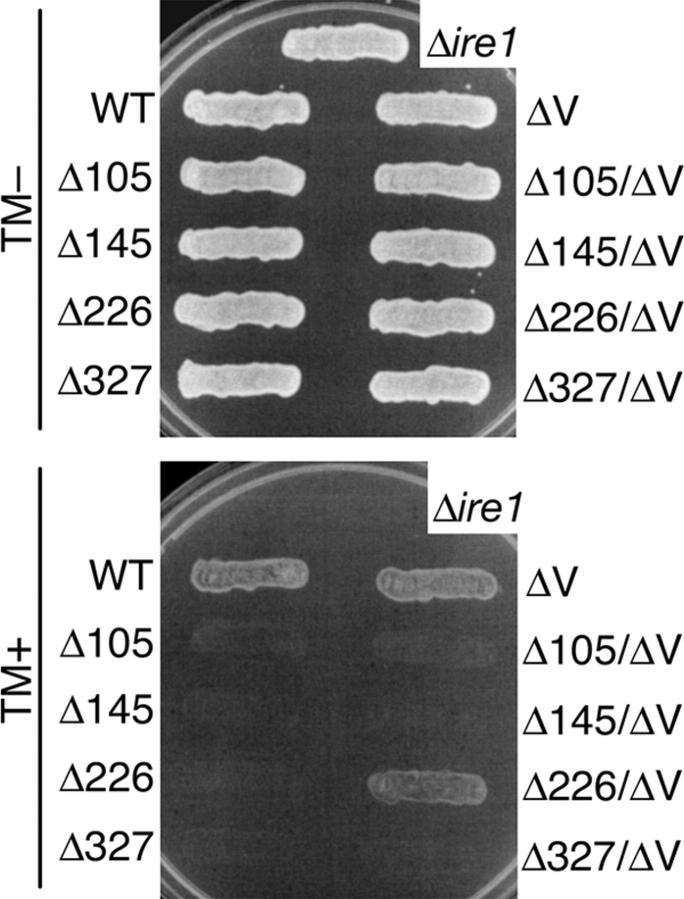

Growth of deletion mutants of Ire1 on agar plates containing tunicamycin. The Δire1 strain KMY1015 carrying the indicated deletion mutant version of pRS315-IRE1-HA was streaked on SD agar plates containing (TM+) or not containing (TM−) 2 μg/ml tunicamycin. For the empty vector control (Δire1), cells carrying pRS315 were used. After incubation at 30°C for 3 d, plates were photographed.

Upon activation, Ire1 is dimerized in response to ER stress (Shamu and Walter, 1996; Bertolotti et al., 2000), and Liu et al. (2000)(and 2002) reported that one important function of the Ire1 luminal domain is to allow the formation of homodimers. Therefore, we checked whether or not the 10-aa deletion mutants formed dimers (or oligomers) in response to ER stress. In Fig. 5, cells coexpressing HA-tagged Ire1 and FLAG-tagged Ire1 were subjected to anti-HA immunoprecipitation. Then, the coimmunoprecipitated FLAG-tagged versions, which are indicative of the oligomeric status of Ire1, were detected by anti-FLAG Western blotting. To render complex formation between HA- and FLAG-tagged molecules more effective than that between two HA-tagged molecules, Ire1-HA and Ire1-FLAG were expressed from the centromeric and 2-μm plasmids, respectively. The first and second panels in Fig. 5 indicate that the deletion mutations tested in this experiment did not cause significant changes in Ire1 expression levels. As expected, wild-type Ire1-FLAG was clearly coimmunoprecipitated with wild-type Ire1-HA in response to treatment of cells with tunicamycin. It is notable that similar results were obtained when either the Δ145 or the Δ226 mutation was introduced. On the contrary, another subregion-II deletion (Δ105) and a subregion-IV deletion (Δ327) impaired dimerization of Ire1. Therefore, we have concluded that the Δ145 and the Δ226 Ire1 molecules are folded correctly at least to a level such that dimerization in response to ER stress occurs.

Next, we asked if activity of these subregion-II and -IV mutants is restored by introduction of the ΔV mutation. First, we tried the UPRE-lacZ reporter assay using the same procedure as in Figs. 1 A and 2 B, and detected no activity with the double deletion mutant Δ105/ΔV, Δ145/ΔV, Δ226/ΔV, or Δ327/ΔV. We then monitored growth of the Ire1 mutant cells on agar plates containing tunicamycin because this method allows us to detect activity of Ire1 mutants even if it is too weak to be detected by the UPRE-lacZ reporter assay or Northern blot detection of the spliced form of HAC1 mRNA. In Fig. 6, Δire1 strains transformed with plasmids for expression of the Ire1 mutants were streaked on two synthetic medium plus dextrose (SD) agar plates, one of which contained 2 μg/ml tunicamycin. After incubation of the plates at 30°C for 3 d, only cells carrying wild-type, ΔV, or Δ226/ΔV Ire1 grew on the tunicamycin plate. This finding shows that abolishment of BiP binding partly restored activity of Δ226 Ire1, and thus that one important defect caused by the Δ226 mutation is specific to the process of releasing BiP.

Deletion of subregion V renders Ire1 hypersensitive to ethanol and high temperature

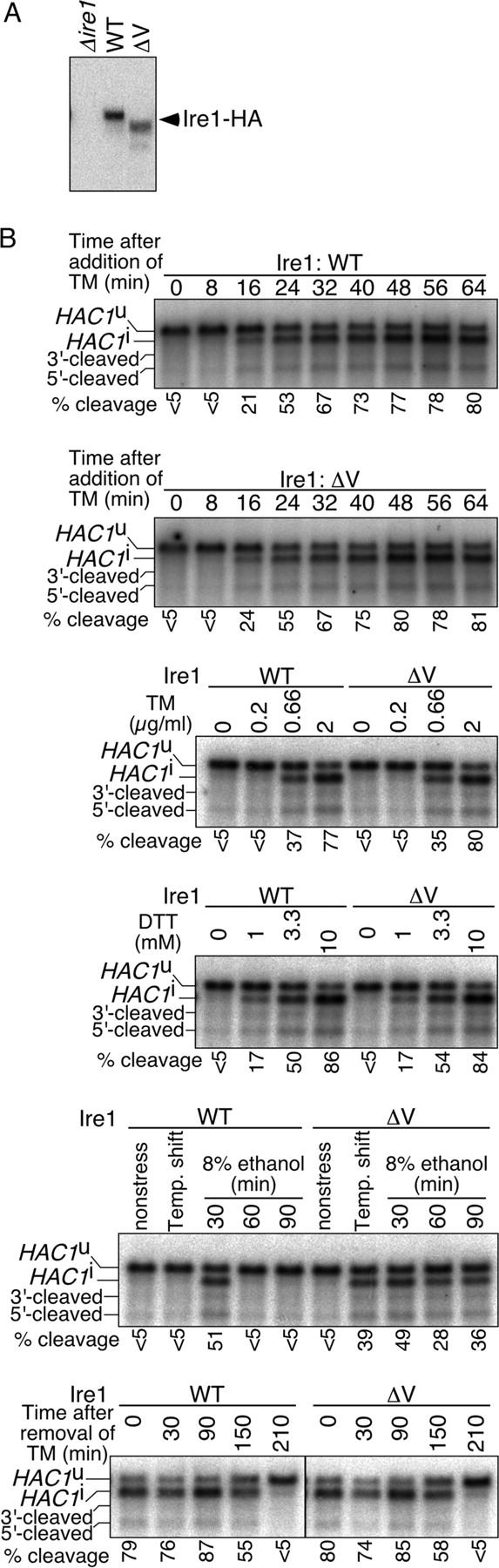

We performed a detailed phenotypic analysis of the ΔV mutant to understand what happens when the binding of BiP to Ire1 is abolished. First, Ire1 and its ΔV version were expressed as HA-tagged proteins from the centromeric plasmids and were detected by anti-HA Western blotting of the cell lysates. As shown in Fig. 7 A, the ΔV mutation caused a small (∼20%) diminution of the steady-state level of the Ire1 protein.

Figure 7.

Hypersensitive response of Ire1 with a subregion-V deletion not to conventional ER stressors, but to high temperature and ethanol. (A) The Δire1 strain KMY1015 carrying either empty vector pRS315 (Δire1), pRS315-IRE1-HA (WT), or its ΔV mutant version was cultured under nonstressed conditions, and its lysate (equivalent to 3 × 106 cells; prepared using denaturing lysis buffer) was analyzed by anti-HA Western blotting. (B) A Δire1 strain KMY1516 carrying either pRS313-IRE1 (a centromeric plasmid for expression of untagged Ire1; WT) or its ΔV mutant version was cultured under nonstressed conditions of 30°C, treated with tunicamycin (TM) at 2 μg/ml for the indicated time (top and second panels) or at the indicated concentration for 60 min (third panel), DTT at the indicated concentration for 40 min (fourth panel) or 8% ethanol for the indicated time (fifth panel), or shifted to 37°C for 30 min and then to 39°C for 30 min (fifth panel, Temp. shift). For the bottom panel, cells treated with 2 μg/ml tunicamycin for 60 min were washed twice with fresh SD medium and further cultured for the indicated time. 1 μg of total RNA prepared from these cells was analyzed by Northern blotting using the HAC1 gene as probe. The positions of uncleaved (HAC1 u), cleaved then ligated (HAC1 i), and cleaved but unligated (5′-cleaved and 3′-cleaved) versions of HAC1 mRNA are indicated (Kawahara et al., 1998). The percentage of HAC1 mRNA cleavage was estimated as described in Kimata et al. (2003).

To perform a more detailed comparison of the activities, we expressed untagged Ire1 proteins in a Δire1 strain and observed cleavage of HAC1 mRNA, which is the direct target of Ire1. When stresses were not imposed on cells, HAC1 mRNA was hardly cleaved by either wild-type or ΔV Ire1 (Fig. 7 B, time 0 in the first and second panels, tunicamycin or DTT at a concentration of 0 in the third and fourth panels, and “nonstress” in the fifth panel). As shown in the first and second panels of Fig. 7 B, wild-type and ΔV Ire1 showed no significant difference in the time course of activation by treatment of cells with 2 μg/ml tunicamycin. Cells were then treated with tunicamycin and another ER stressor, DTT, at various concentrations. The treatment time was 60 min for tunicamycin or 40 min for DTT, which is long enough for saturation of the response (Fig. 7 B, first and second panels; and not depicted). As shown in the third and fourth panels of Fig. 7 B, both tunicamycin and DTT induced cleavage of HAC1 mRNA in concentration-dependent manners, and no difference was observed between wild-type and ΔV Ire1. As indicated in Fig. 5, dimer formation of ΔV Ire1, as well as that of wild-type Ire1, was also dependent on ER stress.

This observation indicates that BiP does not play a key role in ER-stress sensing and raises the question of what is the physiological significance of BiP binding to Ire1. Because we hypothesized that BiP acts as a sort of adjustor that inhibits improper activation of Ire1, stresses not commonly considered to affect the ER were imposed on cells producing either wild-type or ΔV Ire1. As shown in the fifth panel of Fig. 7 B, treatment of cells with 8% ethanol caused transient activation of wild-type Ire1, which within 60 min, was attenuated to a level at which cleavage of HAC1 mRNA was not observed. On the contrary, the cleavage was clearly observed in the ΔV Ire1 cells even 90 min after addition of ethanol into the culture. To impose high temperature, cultures were shifted from 30 to 37°C for 30 min, and then to 39°C for 30 min, to avoid acute damage to cells. This temperature shift caused HAC1 mRNA cleavage in the ΔV Ire1 cells, but not in wild-type cells (Fig. 7 B, fifth panel).

Another explanation for the role of BiP is to shut down UPR signaling at the time of recovery from ER stressed conditions. To test this idea, cells exposed to tunicamycin were washed and further cultured in normal medium, but we failed to demonstrate a significant difference between the wild-type and ΔV Ire1 cells (Fig. 7 B, bottom panel).

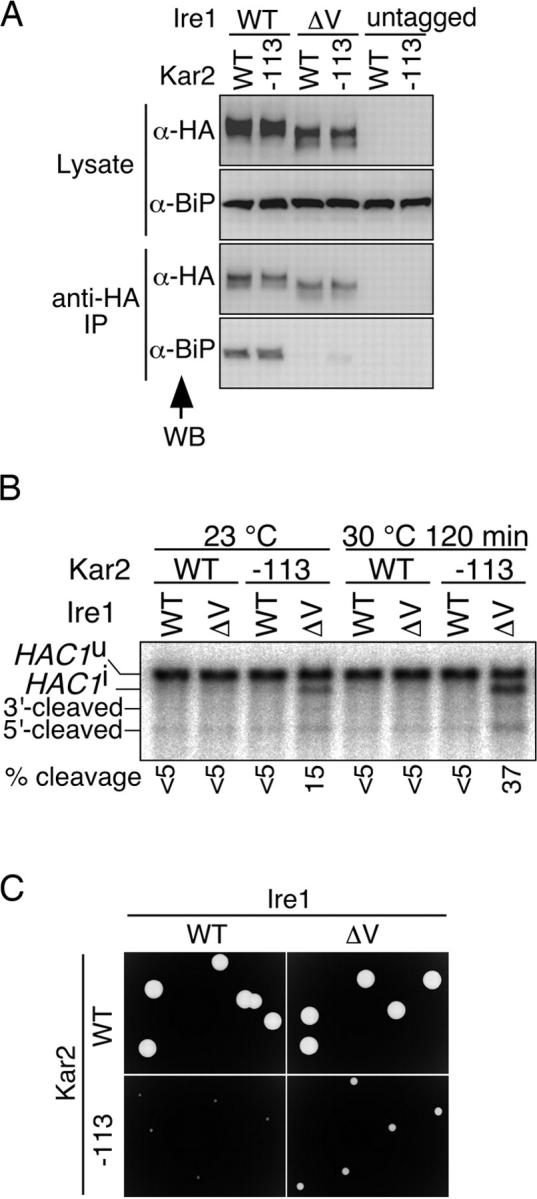

UPR repression phenotype of kar2-113 is suppressed by deletion of Ire1 subregion V

We previously reported that in the temperature-sensitive mutant alleles of the KAR2 gene encoding BiP with single amino acid changes in the ATPase domain, and BiP dissociation from Ire1 and activation of the UPR pathway are impaired when cells are cultured at a restrictive temperature (Kimata et al., 2003). One prediction from the present work is that deletion of Ire1 subregion V, abolishing BiP binding to Ire1, may suppress the UPR repression phenotype of the kar2 mutants. To test this possibility, we introduced the kar2-113 mutation, a commonly used mutant allele of the BiP ATPase domain, into wild-type and ΔV Ire1 strains. As shown in Fig. 8 A, binding of BiP to Ire1 was abolished by the Ire1 ΔV mutation not only in KAR2 but also in kar2-113 cells.

Figure 8.

Analysis of a double mutation of kar2-113 and Ire1 subregion-V deletion. (A) The kar2-113 mutation was introduced into the Δire1 strain KMY1516 carrying either pRS313-IRE1 (untagged), pRS423-IRE1-HA (WT), or its ΔV mutant version, as described in the online supplemental Materials and methods (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200405153/DC1). The resulting cells and the control KAR2 cells (WT) were cultured at 23°C without extrinsic ER stress and subjected to anti-HA immunoprecipitation as described in Materials and methods. The cell lysates (equivalent to 3 × 106 cells) and immunoprecipitates (equivalent to 1 × 107 cells) were analyzed by anti-HA and anti-BiP Western blotting. (B) The kar2-113 mutation was introduced into KMY1516 cells carrying pRS313-IRE1 (WT) or its ΔV mutant version, as described in the online supplemental Materials and methods. The resulting cells and the control KAR2 cells (WT) were cultured at 23°C or shifted to 30°C for 120 min without extrinsic ER stress and analyzed by Northern blotting of 1 μg of total RNA using the HAC1 gene as probe. The positions of the HAC1 mRNA variants are indicated as in Fig. 7 B. The percentage of HAC1 mRNA cleavage was estimated as described in Kimata et al. (2003). (C) After spreading the cultures used in B (those at 23°C), SD agar plates were incubated at 33°C for 2 d and colonies were photographed.

Activity of Ire1 was estimated by Northern blot analysis for cleavage of HAC1 mRNA (Fig. 8 B). In kar2-113 / Ire1ΔV double mutant cells, a little cleavage of mRNA occurred even at the permissive temperature of 23°C and was enhanced at the semi-permissive temperature of 30°C. In contrast, kar2-113 single mutant cells, as well as Ire1ΔV single mutant and wild-type cells, showed no or very weak cleavage.

There are two interpretations for this finding. The first is that the kar2-113 mutation itself imposes ER stress, which in the single mutant, does not activate Ire1 because of impaired dissociation of the mutant BiP protein from Ire1. In this case, cleavage of HAC1 mRNA in the double mutant cells is considered to be a result of suppression of the UPR repression phenotype of kar2-113 by the Ire1 ΔV mutation. The second is that the double mutation, not the single mutation, somehow causes ER stress. We think that the former interpretation is likely because severe growth retardation of the kar2-113 cells at 33°C is partly restored by the Ire1 ΔV mutation (Fig. 8 C).

We did not perform experiments as shown in Fig. 8 B by incubating cells at temperatures higher than 35°C because ΔV Ire1 was significantly degraded in kar2-113 cells but not in wild-type cells at these temperatures (unpublished data), probably for complicated reasons. The ΔV Ire1 protein may be unstable at high temperatures, and it is likely that the high activation of the UPR pathway induced ER-associated degradation of proteins (Casagrande et al., 2000; Friedlander et al., 2000; Travers et al., 2000).

Discussion

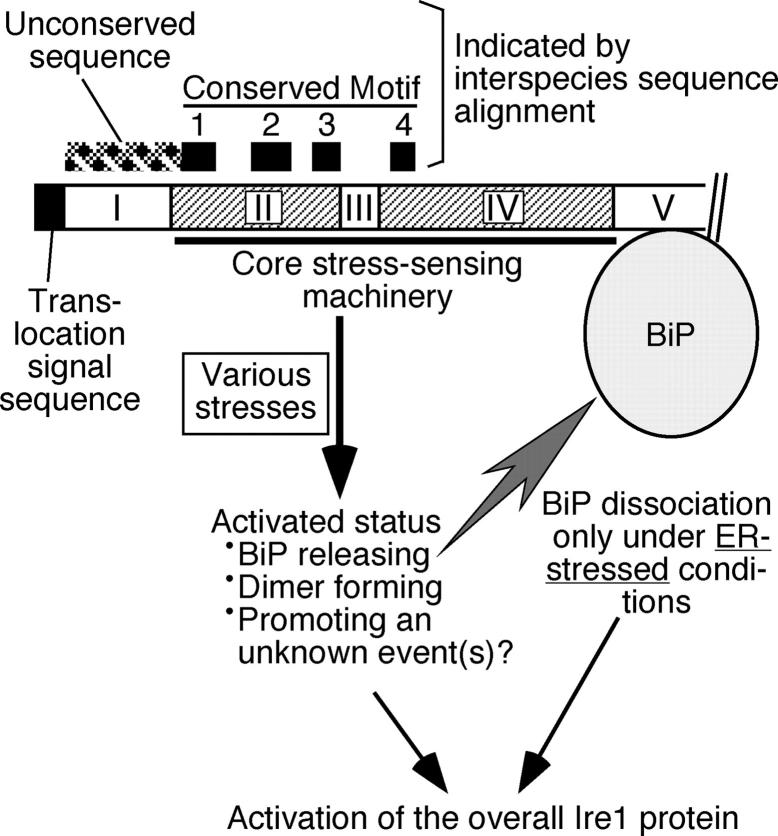

This work was initiated from a serial and targeted mutagenesis study of the yeast IRE1 gene to understand the relationship of structure to function of the Ire1 luminal domain. As shown in Fig. 1 A and Fig. 2, the results predict that the yeast Ire1 luminal domain is divided into five subregions, among which subregions II and IV are indispensable for Ire1 activity. Liu et al. (2000) reported an interspecies comparison of Ire1 and PERK sequences, which predicted four conserved motifs (named Motif 1 to 4) in their luminal domains. As illustrated in Fig. 9, Motifs 1, 2, and 3 reside in subregion II, and Motif 4 in subregion IV. The interspecies comparison of Ire1 also shows that subregion I is carried only by yeast Ire1, as the sequences corresponding to subregion II neighbor the NH2-terminal translocation signal in metazoan and plant Ire1 orthologues (Liu et al., 2000; Koizumi et al., 2001). It seems that these findings provide a good example of the dogma that an evolutionarily conserved sequence is functionally important and vice versa.

Figure 9.

Our current model to interpret structure and function of the yeast Ire1 luminal domain. Positions of conserved motifs deduced by interspecies sequence alignment of Ire1 and PERK (Liu et al., 2000), together with that of an unconserved sequence not present in Ire1 orthologues of higher eukaryotes (Liu et al., 2000, Koizumi et al., 2001) are indicated.

Because deletions of sequential amino acid residues may cause gross perturbation of protein structure, we do not think that all of the 10-aa segments in subregion II and IV are responsible for specific functions to activate Ire1. However, as discussed later, we believe that the Δ226 mutant, and possibly also the Δ145 mutant, are specifically impaired in releasing BiP from Ire1. Liu et al. (2000) performed single amino acid mutation analysis of subregion II and IV, but no mutants that altered the function of Ire1 were identified.

The deletion and in vitro proteolysis analyses of Ire1 shown in Figs. 3 and 4 indicate that the BiP-binding site is located in subregion V. Because we speculate that subregions II and IV, being highly sensitive to internal deletions, are tightly folded, it seems reasonable that BiP does not target these subregions. Binding of BiP to Ire1 in mammalian cells, which was initially reported in Bertolotti et al. (2000), was further demonstrated in Liu et al. (2002)(2003) by pulling down BiP with luminal domain fragments of human Ire1α from mammalian cell lysates. Inconsistent with our observation, BiP was reported to bind to the Ire1α luminal domain fragment with further truncation of the juxtamembrane 107 amino acids. This may have been caused by insufficient folding of the highly expressed Ire1α fragment, which was clearly detectable in cell lysates by 1-D PAGE and subsequent Coomassie blue staining of the gel.

In addition to Ire1, PERK and ATF6 have been reported to bind to BiP under nonstressed conditions (Bertolotti et al., 2000; Shen et al., 2002). Though dissociation from BiP is a common event upon activation of Ire1, PERK, and ATF6 (Bertolotti et al., 2000; Okamura et al., 2000; Shen et al., 2002), the mechanism is poorly understood. The simplest explanation for BiP dissociation is competitive deprivation of BiP by unfolded protein substrate produced by ER stress. Our previous work, suggesting that BiP recognizes Ire1 as a chaperone substrate (Kimata et al., 2003), seems to support this “competitive deprivation model.” One implication of this model is that Ire1 does not positively function in Ire1-BiP dissociation, which this work does not support.

Because of the following observations, we believe that the subregion-II deletion mutation Δ226, and possibly also another subregion-II deletion mutation (Δ145), specifically impair BiP release from Ire1 without causing gross perturbations in Ire1 structure. As shown in lanes 19, 20, 25, 26, and 75–78 in Fig. 3, BiP constitutively bound to the Δ145 and the Δ226 mutants. Even in these mutants, the BiP-binding site was located in subregion V (Fig. 3, lanes 69–72 and 81–84). Moreover, both the Δ145 and the Δ226 mutants had the ability to dimerize in response to ER stress (Fig. 5). In addition, activity of the Δ226 mutant was partly restored when the ΔV mutation, which abolishes BiP binding to Ire1, was introduced (Fig. 6). Therefore, we propose that subregion II positively functions to release BiP from Ire1, though another line of evidence will be required to prove definitively this idea.

It is likely that another role for subregion II, and also for subregion IV, is to promote dimerization of Ire1. Both the recombinant fragment of subregion II and that of subregion IV form homodimers in vitro (unpublished data). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 5, the Δ105 and the Δ327 mutants had no or slight dimer-forming ability. It should be noted that BiP dissociated from these mutants in response to ER stress (Fig. 3, lanes 15, 16, 35, and 36), although this dissociation was not as drastic as that from wild-type Ire1. The phenotypic differences between Δ145 and Δ226 and Δ105 and Δ327 imply the absence of causality between BiP release and dimer formation. Furthermore, we speculate that an unknown event(s) other than BiP release or dimer formation may be required for Ire1 to be fully activated. This is because the activities of the Δ145/ΔV and Δ226/ΔV double mutants were undetectable and weak, respectively, although these mutants showed both the abolishment of BiP binding and normal dimerization (Fig. 3, lanes 69–72 and 81–84; and not depicted).

Importantly and unexpectedly, mutations that abolished binding of BiP (e.g., ΔV) did not render Ire1 constitutively active. As shown in Fig. 7 B, wild-type Ire1 and the ΔV mutant did not show a difference in sensitivity to the conventional ER stressors, tunicamycin and DTT. Moreover, the time courses of attenuation of activity during recovery from ER-stressed conditions were almost identical between these two Ire1 proteins. However, a hypersensitive response of ΔV Ire1 was observed when cells were treated either with ethanol or high temperature (39°C). This finding suggests that Ire1 has an intrinsic ability to sense not only conventional ER stress but also other stresses, which actually cause little or no activation of Ire1. In this scenario, BiP functions to confine Ire1 to responding to ER stress. It remains unclear how treatment of cells with ethanol or high temperature is sensed by ΔV Ire1 because these stresses impose various kinds of cellular damage, including membrane damage.

Ma et al. (2002) reported a mutation study of human PERK (called PEK in their paper), in which the results are partly similar and partly different from ours. According to them, deletions in middle region (amino acid position 102–407) of the luminal domain abolished dimer formation and activation of PERK. Because deletion not of this middle region but of the juxtamembrane amino acids (position 411–481) diminished BiP binding to PERK, the BiP-binding site was set in the juxtamembrane sequence. An important difference from our work is that this deletion of the juxtamembrane amino acids caused constitutive activation of PERK. One explanation for this finding is that the regulatory mechanism of PERK is somewhat different from that of Ire1. Alternatively, their PERK mutant with the juxtamembrane amino-acid deletion may be activated by its overexpression from the strong cytomegalovirus promoter, as we believe that deletion of the BiP-binding site caused “potential” activation of Ire1 and probably also PERK.

As described in the Introduction, we now think that much care is required to interpret results from the kar2 mutant strains used in our previous paper (Kimata et al., 2003) because of the multiple and essential roles of BiP in protein import, folding, and export. In that paper, cells carrying substrate-binding domain mutations of BiP constitutively showed activation of Ire1 and dissociation of the BiP/Ire1 complex when cultured at the restrictive temperature. We now believe that this is caused at least in part by elevation of ER-stress status by these BiP mutations because knocking out the IRE1 gene caused a severe growth delay of the BiP mutant cells (unpublished data). In contrast, we show here that it is likely that phenotypes of the kar2-113 mutation are directly caused in part by impaired dissociation of the mutant BiP protein from Ire1 (Fig. 8). Importantly, our finding that the UPR repression phenotype of kar2-113 is suppressed by the Ire1 ΔV mutation provides further evidence for negative regulation of Ire1 by BiP binding to subregion V.

In conclusion, although it is an ER-resident protein that negatively regulates the UPR signaling pathway, BiP does not seem to be involved in the core machinery to sense ER stress because it is very likely that Ire1 positively functions to release BiP and because Ire1 lacking the BiP-binding site still responds to ER stress. In Fig. 9, we present a possible mechanism by which Ire1 is up-regulated. According to this model, subregions II and IV constitute the core stress-sensing machinery, which, in response to ER stress, become activated to dimerize, to release BiP from subregion V, and possibly to promote an unknown event(s) for overall up-regulation of the Ire1 protein. Here, we also propose that the precision of this core stress-sensing machinery is insufficient, and BiP functions as an adjustor to limit Ire activation to respond only to ER stress. Upon ER stress, unfolded proteins that accumulate in the ER may act to facilitate dissociation of BiP from Ire1, though the aforementioned simple “competitive deprivation model” is unlikely. Various intracellular signaling pathways have been reported to be controlled by cytosolic HSP70 (for reviews see Morimoto, 1998; Nollen and Morimoto, 2002). To fully elucidate the biological meaning of this regulation, we hope that insights from our work provide suggestions.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains, plasmids, and generation of their mutants

Culturing and genetic manipulation of yeast strains were by standard techniques described in Kaiser et al. (1994). Basically, cells were cultured in minimal SD supplemented with appropriate nutrients at 30°C. The genotypes of Δire1 strains KMY1015, KMY1516, and KMY1520 are described in the online supplemental Materials and methods. These strains show no difference in phenotypes related to the UPR, and we used these three strains according to the difference of nutrient markers and mating types. The URA3 2-μm plasmid pCZY1, carrying a fusion of UPRE-CYC1 core promoter-lacZ, was a gift of K. Mori (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). Because of reproducibility of results, we preferred pCZY1 to the chromosomally integrated UPR reporters carried by KMY1516. Construction of the IRE1 plasmids is described in the online supplemental Materials and methods.

IRE1 mutants used in this study were created by a methodology using the overlap PCR and in vivo gap repair techniques (Ho et al., 1989; Muhlrad et al., 1992). The detailed procedure is described in the online supplemental Materials and methods. In brief, an IRE1 gene fragment carrying a desired mutation was generated by the overlap PCR technique, and one of the IRE1 plasmids was restriction enzyme digested to make a gap on its IRE1 gene sequence. The resulting overlap PCR product and linearized plasmid were cotransformed into one of the Δire1 strains, and transformant clones carrying the successfully gap-repaired circular plasmid generated by homologous recombination between the two DNAs were used for the experiments in this paper. The procedure for introduction of the kar2-113 mutation into yeast strains is described in the online supplemental Materials and methods.

Antibodies and protein analyses

Antibodies used in this paper were mouse anti-HA mAb 12CA5 (Roche Diagnostics), rabbit anti-recombinant yeast BiP antiserum (Tokunaga et al., 1992), mouse anti-FLAG mAb M2 (Sigma-Aldrich), and affinity-purified rabbit antibody against yeast Ire1 NH2-terminal peptide CNTADNRRANKKGRRAA.

Lysis of yeast cells under nondenaturing conditions was performed as described previously (Kimata et al., 2003). For cell lysis under denaturing conditions, this method was modified by breaking the cells using glass-bead beating in denaturing lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.9, 5 mM EDTA, 180 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors. Anti-HA immunoprecipitation from the nondenaturing lysates was performed as described previously (Kimata et al., 2003), using protein A–conjugated Sepharose beads (protein A–Sepharose 4 FF; Amersham Biosciences).

The lysates and immunoprecipitates were denatured in SDS/DTT-sampling buffer and analyzed by anti-HA and anti-BiP Western blotting, using HRP-coupled secondary antibodies and the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences), also as described previously (Kimata et al., 2003) except for the following modifications. First, we performed SDS-PAGE by using precast gels (Daiichi Pure Chemicals). The concentration of acrylamide in the gels was 10% for the experiments shown in Figs. 3, 4 B, and 8 A, initially to detect bands of the 12CA5 antibody as an internal control for immunoprecipitation. For the experiments to detect Ire1-HA only, 7.5% polyacrylamide gels were used. Second, ECL signals were detected by a cooled CCD camera system LAS-1000plus (Fuji) instead of X-ray films. The exposure time was 10–15 s for BiP, 1–2 min for Ire1-HA expressed from centromeric plasmids (Figs. 1 B and 7 A), and 8–13 s for Ire1-HA in other preparations. The same method was used for Western blot detection of Ire1-FLAG by anti-FLAG M2 antibody in Fig. 5.

For proteolytic cleavage analysis, nondenaturing lysate from cells producing HA-tagged Ire1 with the III-IEGR insertion was subjected to anti-HA immunoprecipitation. The resulting immunoprecipitate equivalent to 1 × 108 cells (15 μl of protein A–conjugated Sepharose beads trapping anti-HA antibody bound to target proteins) was resuspended in 15 μl of Factor Xa cleavage buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, and 2 mM CaCl2) containing or not containing Factor Xa (New England Biolabs, Inc.) and incubated at 23°C for 4 h with rotation. The beads were collected by centrifugation (3,000 g for 10 s), washed five times with Factor Xa cleavage buffer, and heated in SDS/DTT-sampling buffer for Western blot analysis. The released (supernatant) fraction after Factor Xa cleavage was also collected and heated in SDS/DTT-sampling buffer for Western blot analysis. For dot blotting, 5 μl of the released fraction was spotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Hybond-P; Amersham Biosciences), and the membrane was treated with the same procedure as Western blot analysis using the HRP-coupled secondary antibody and the ECL system.

Other techniques

Cellular β-galactosidase activity assays and RNA analysis were performed as described previously (Kimata et al., 2003).

Image acquisition

Radioactive signal from the Northern blots was detected using a PhosphorImager (model BAS-2500; Fuji). ECL signal from the Western blots was detected using LAS-1000plus as described in Antibodies and protein analyses. Non-linear adjustments of the images were not performed.

Online supplemental material

Table S1 lists the internal sense deletion primers used for the overlap PCR. The antisense deletion primers were made complementary to the sense deletion primers. In Fig. S1, positions of the 10-aa deletions are presented with the amino acid sequence of the luminal domain of yeast Ire1. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200405153/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kazutoshi Mori for materials and Miki Matsumura for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (14037240 to K. Kohno and 15030232 to Y. Kimata) and for 21st Century COE Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (15570160 to Y. Kimata).

Abbreviations used in this paper: PERK, PKR-like ER kinase; SD, synthetic medium plus dextrose; UPR, unfolded protein response; UPRE, UPR element.

References

- Bertolotti, A., Y. Zhang, L.M. Hendershot, H.P. Harding, and D. Ron. 2000. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfon, M., H. Zeng, F. Urano, J.H. Till, S.R. Hubbard, H.P. Harding, S.G. Clark, and D. Ron. 2002. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 415:92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande, R., P. Stern, M. Diehn, C. Shamu, M. Osario, M. Zuniga, P.O. Brown, and H. Ploegh. 2000. Degradation of proteins from the ER of S. cerevisiae requires an intact unfolded protein response pathway. Mol. Cell. 5:729–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.S., and P. Walter. 1996. A novel mechanism for regulating activity of a transcription factor that controls the unfolded protein response. Cell. 87:391–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.S., C.E. Shamu, and P. Walter. 1993. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 73:1197–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander, R., E. Jarosch, J. Urban, C. Volkwein, and T. Sommer. 2000. A regulatory link between ER-associated protein degradation and the unfolded-protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething, M.J. 1999. Role and regulation of the ER chaperone BiP. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 10:465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, H.P., Y. Zhang, and D. Ron. 1999. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 397:271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haze, K., H. Yoshida, H. Yanagi, T. Yura, and K. Mori. 1999. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 10:3787–3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.N., H.D. Hunt, R.M. Horton, J.K. Pullen, and L.R. Pease. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 77:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwawaki, T., A. Hosoda, T. Okuda, Y. Kamigori, C. Nomura-Furuwatari, Y. Kimata, A. Tsuru, and K. Kohno. 2001. Translational control by the ER transmembrane kinase/ribonuclease IRE1 under ER stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, C., S. Michaelis, and A. Mitchell. 1994. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 230 pp.

- Kawahara, T., H. Yanagi, T. Yura, and K. Mori. 1998. Unconventional splicing of HAC1/ERN4 mRNA required for the unfolded protein response. Sequence-specific and non-sequential cleavage of the splice sites. J. Biol. Chem. 273:1802–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata, Y., Y.I. Kimata, Y. Shimizu, H. Abe, I.C. Farcasanu, M. Takeuchi, M.D. Rose, and K. Kohno. 2003. Genetic evidence for a role of BiP/Kar2 that regulates Ire1 in response to accumulation of unfolded proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:2559–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno, K., K. Normington, J. Sambrook, M.J. Gething, and K. Mori. 1993. The promoter region of the yeast KAR2 (BiP) gene contains a regulatory domain that responds to the presence of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:877–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi, N., I.M. Martinez, Y. Kimata, K. Kohno, H. Sano, and M.J. Chrispeels. 2001. Molecular characterization of two Arabidopsis Ire1 homologs, endoplasmic reticulum-located transmembrane protein kinases. Plant Physiol. 127:949–962. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K., W. Tirasophon, X. Shen, M. Michalak, R. Prywes, T. Okada, H. Yoshida, K. Mori, and R.J. Kaufman. 2002. IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 16:452–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Y., M. Schroder, and R.J. Kaufman. 2000. Ligand-independent dimerization activates the stress response kinases IRE1 and PERK in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 275:24881–24885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Y., H.N. Wong, J.A. Schauerte, and R.J. Kaufman. 2002. The protein kinase/endoribonuclease IRE1α that signals the unfolded protein response has a luminal N-terminal ligand-independent dimerization domain. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18346–18356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.Y., Z. Xu, and R.J. Kaufman. 2003. Structure and intermolecular interactions of the luminal dimerization domain of human IRE1α. J. Biol. Chem. 278:17680–17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K., K.M. Vattem, and R.C. Wek. 2002. Dimerization and release of molecular chaperone inhibition facilitate activation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2 kinase in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18728–18735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, K., A. Sant, K. Kohno, K. Normington, M.J. Gething, and J.F. Sambrook. 1992. A 22 bp cis-acting element is necessary and sufficient for the induction of the yeast KAR2 (BiP) gene by unfolded proteins. EMBO J. 11:2583–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, K., W. Ma, M.J. Gething, and J. Sambrook. 1993. A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signaling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell. 74:743–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, K., T. Kawahara, H. Yoshida, H. Yanagi, and T. Yura. 1996. Signalling from endoplasmic reticulum to nucleus: transcription factor with a basic-leucine zipper motif is required for the unfolded protein-response pathway. Genes Cells. 1:803–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, K., N. Ogawa, T. Kawahara, H. Yanagi, and T. Yura. 2000. mRNA splicing-mediated C-terminal replacement of transcription factor Hac1p is required for efficient activation of the unfolded protein response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:4660–4665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, R.I. 1998. Regulation of the heat shock transcriptional response: cross talk between a family of heat shock factors, molecular chaperones, and negative regulators. Genes Dev. 12:3788–3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlrad, D., R. Hunter, and R. Parker. 1992. A rapid method for localized mutagenesis of yeast genes. Yeast. 8:79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollen, E.A., and R.I. Morimoto. 2002. Chaperoning signaling pathways: molecular chaperones as stress-sensing ‘heat shock’ proteins. J. Cell Sci. 115:2809–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura, K., Y. Kimata, H. Higashio, A. Tsuru, and K. Kohno. 2000. Dissociation of Kar2p/BiP from an ER sensory molecule, Ire1p, triggers the unfolded protein response in yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 279:445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegsegger, U., J.H. Leber, and P. Walter. 2001. Block of HAC1 mRNA translation by long-range base pairing is released by cytoplasmic splicing upon induction of the unfolded protein response. Cell. 107:103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamu, C.E., and P. Walter. 1996. Oligomerization and phosphorylation of the Ire1p kinase during intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. EMBO J. 15:3028–3039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J., X. Chen, L. Hendershot, and R. Prywes. 2002. ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Dev. Cell. 3:99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrauski, C., and P. Walter. 1997. The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 90:1031–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirasophon, W., A.A. Welihinda, and R.J. Kaufman. 1998. A stress response pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus requires a novel bifunctional protein kinase/endoribonuclease (Ire1p) in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 12:1812–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga, M., A. Kawamura, and K. Kohno. 1992. Purification and characterization of BiP/Kar2 protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 267:17553–17559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers, K.J., C.K. Patil, L. Wodicka, D.J. Lockhart, J.S. Weissman, and P. Walter. 2000. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 101:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Z., H.P. Harding, Y. Zhang, E.M. Jolicoeur, M. Kuroda, and D. Ron. 1998. Cloning of mammalian Ire1 reveals diversity in the ER stress responses. EMBO J. 17:5708–5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, H., T. Matsui, A. Yamamoto, T. Okada, and K. Mori. 2001. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 107:881–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]