Abstract

For many years after the discovery of actin filaments and microtubules, it was widely assumed that their polymerization, organization, and functions were largely distinct. However, in recent years it has become increasingly apparent that coordinated interactions between microtubules and filamentous actin are involved in many polarized processes, including cell shape, mitotic spindle orientation, motility, growth cone guidance, and wound healing. In the past few years, significant strides have been made in unraveling the intricacies that govern these intertwined cytoskeletal rearrangements.

In this report, we highlight the actin–microtubule crosstalk that occurs during directed cell movements. For each step in the process, we review the regulatory mechanisms that underlie both the independent and the interdependent cytoskeletal rearrangements of actin filaments and microtubules that coordinate cellular locomotion in a polarized fashion. We discuss how external directional cues activate Rho GTPases at specific cellular sites to initiate localized cytoskeletal rearrangements, and we focus on the signaling pathways that cause either actin or microtubule rearrangement and the regulatory interactions between these cytoskeletons. We also consider “search and capture” mechanisms involving structural interactions between F-actin and microtubules near the leading edge of cells. Finally, we spotlight spectraplakins, able to directly bind both F-actin and microtubules. Recently, spectraplakins have emerged as candidates for coordinating the two cytoskeletons in directional migration.

Establishment of the cortical platform at the leading edge of a cell

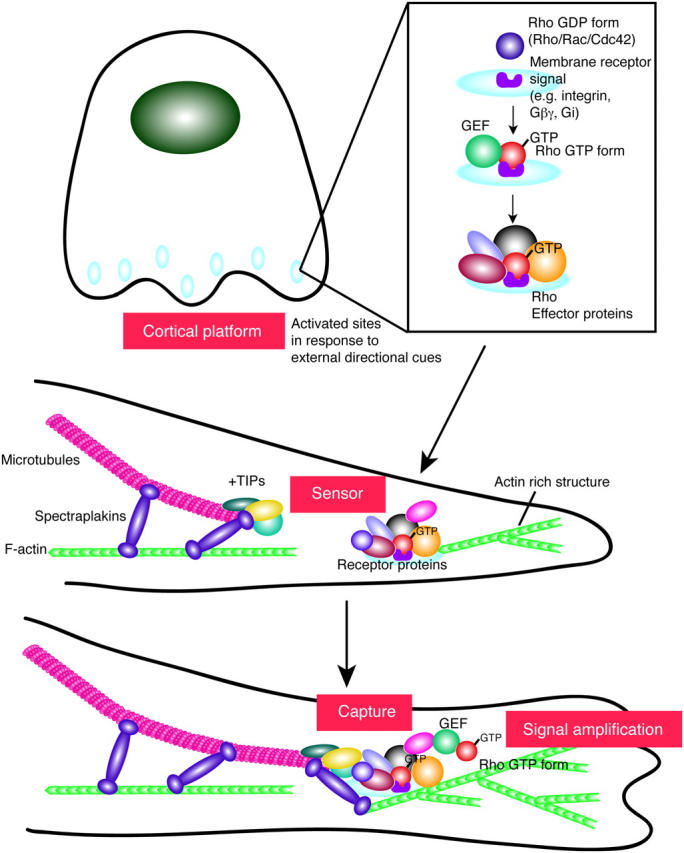

Cells migrate by coordinating cytoskeletal-mediated extensions and contractions concomitantly with making and breaking contacts to an underlying substratum. To orchestrate directional movements, cells must activate a specific site(s) at the membrane periphery in response to a polarized external cue (Fig. 1; top left). A particular locale then becomes a “cortical platform” for the transmission of converging internal signals that are necessary to elicit subsequent cytoskeletal responses. The outcome is dependent upon the cell type and the precise signaling pathways that are engaged, and can range from the polymerization and/or reorganization of actin to the polarized capture and stabilization of microtubules and their associated microtubule organizing center (MTOC).

Figure 1.

Schematic view of cortical platform formation, maturation, and function. Cortical platforms are localized membrane-associated sites that develop into a rich molecular center for the convergence of transmembrane receptors, signal transduction proteins, actin polymerization machinery, and microtubule capture mechanisms. One of the earliest steps in the formation of a cortical platform center is the recruitment and activation of the Rho family of small GTPases. Downstream GTPase-activated effector proteins, including actin binding proteins and +TIPs, are then recruited to these activated sites. This sets off a molecular cascade of events that culminates in the polarization and polymerization of actin and the capturing of the growing ends of microtubules. The strength of the actin–microtubule connection is likely to have a marked impact on the length of time that microtubules are polarized at cortical platforms. In simpler eukaryotes where microtubule capture typically occurs over short periods of time, these linkages are indirect, involving multiple proteins, some with actin binding domains and others with microtubule or +TIP binding domains. In more complex eukaryotes with needs to prolong the capture process, spectraplakins evolved as scaffold proteins that can bind F-actin, +TIPs, microtubules, and likely a myriad of other proteins. These proteins are likely to function not only in stabilizing microtubule–actin interactions, but also in integrating other events, such as cell migration or cell–cell adhesion, that may take place at cortical platforms. See text for detailed descriptions of the proteins and structures shown here.

A cortical platform can facilitate crosstalk between F-actin and microtubules by functioning as a transducer/amplifier of the internal cellular signals that orchestrate both cytoskeletons. Small GTPases such as Cdc42, Rac, and Rho have long been implicated in these processes, but precisely how their activities are temporally and spatially regulated at cortical platforms has often been obscure. Some insights have come from studying cultured mammalian cells, including epithelial cells, neurons, astrocytes, and fibroblasts, all of which use transmembrane integrin heterodimers to adhere to, organize, and migrate on a substratum of ECM (Hood and Cheresh, 2002; Fukata et al., 2003).

Referred to as “directional sensors” or “compasses,” the internal cellular modules able to sense extracellular directional gradients have been particularly well studied in chemotactic neutrophils. The engagement of G protein–coupled receptors and activation of Gβγ at the neutrophil surface triggers a complex signaling cascade that culminates in cytoskeletal reorganization and directed migration (Meili and Firtel, 2003). Recent reports reveal that Gβγ binds p21-activated kinase 1, which recruits and activates a guanine nucleotide exchange factor referred to as PIXα. Once activated, PIXα then associates with the small GTPase Cdc42, which upon activation can stimulate actin polymerization (Li et al., 2003).

Positive reinforcement of the process appears to occur through the added ability of Gi to recruit and activate phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase, which promotes the accumulation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)P3 (PIP3). PIP3 then serves as a docking site for PH domain harboring proteins such as guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho family GTPases, including not only Cdc42 but also Rac. In this way, the positive-feed back loop involving PIP3 results in increased levels of activated Rac/Cdc42 at the leading edge of the cell (Meili and Firtel, 2003). In the meantime, Rho appears to be activated at the rear of the neutrophils via G12 and G13 (Xu et al., 2003). A recent but likely not final twist to these complexities in directional sensing mechanisms comes from analyses on T cells, dendritic cells, and fibroblasts that implicate glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in lipid rafts in the activation of small GTPases (del Pozo et al., 2004; Jaksits et al., 2004; Krautkramer et al., 2004; Palazzo et al., 2004).

Localized activation of small GTPases appears to be a unifying and early step in orchestrating the downstream rearrangements in cytoskeleton necessary to polarize cell motility (Fig. 1; top right). Fluorescence resonance energy transfer experiments using probes tailored for individual family members have provided suggestive evidence that different Rho GTPases might function in transmitting unique signals from different cortical platforms, and such specificity may be operative at least in some situations (Kraynov et al., 2000; Gardiner et al., 2002; Itoh et al., 2002).

Actin and microtubule regulatory signals transmitted from the cortical platform

After polarized activation of Rho family small GTPases at cortical platforms, cells transmit downstream signals that are responsible for two distinct processes—motility and polarity. Cells respond to activated GTPases by mobilizing their actin cytoskeletal network and changing their morphology (Hall, 1998). This polarized rearrangement of actin-based structures provides the driving force for “motility,” resulting in the GTPase-dependent induction of filopodia, lamellipodia, and stress fibers (Hall, 1998). However, without polarization of the microtubule cytoskeleton as well, cells cannot sustain the directionality of their movements.

Recent reports reveal that activated Rho promotes the stabilization of microtubules through its downstream target effector mDia (Wen et al., 2004). This stabilization has been visualized by immunofluorescence through the aid of an antibody that binds to the exposed COOH-terminal glutamine residue in long-lived tubulin (Palazzo et al., 2001). Microtubule dynamics can also affect the activity of Rho GTPases and the ability of cells to migrate (Waterman-Storer et al., 1999; Rodriguez et al., 2003). In particular, microtubule disassembly results in Rho activation, yielding an increase in focal adhesions (Krendel et al., 2002; Kirchner et al., 2003), and conversely, microtubule targeting to focal adhesions appears to promote focal contact disassembly (Kaverina et al., 1999). The ability of Rho GTPases to impact on both actin and microtubule cytoskeletons suggests an underlying interdependency upon what had long been surmised to be separate cytoskeletal networks. However, in this case the microtubule–actin crosstalk arises not from structural interactions, per se, but rather from alterations in the regulatory signals that modulate these two cytoskeletons (Wehrle-Haller and Imhof, 2003).

Capturing microtubules at cortical platforms

As postulated by Kirschner and Mitchison nearly two decades ago, microtubules “search” cytoplasmic space by continuously growing and shrinking from their plus ends, which project outward to the cell periphery (Kirschner and Mitchison, 1986). Microtubules are then “captured” and transiently stabilized at specific membrane target sites through plus end–interacting proteins (+TIPs), such as EB-1 and CLIP-170 (Schuyler and Pellman, 2001; Gundersen et al., 2004). +TIPs are thought to act in part by protecting the growing ends of microtubules from catastrophe proteins that might otherwise bind to and initiate the depolymerization of the microtubule (Komarova et al., 2002; Tirnauer et al., 2002). Interestingly, activated Cdc42 and Rac may impact on the growth and dynamics of microtubules at the cell periphery by a PAK signaling pathway that most likely inhibits the microtubule-destabilizing protein Op18/stathmin (Daub et al., 2001; Wittmann et al., 2003, 2004).

+TIPs not only participate in the stabilization of microtubules, but also in targeting microtubules to specific locales. For example, RNA interference knockdown analyses in Drosophila and mammalian cells have unveiled functions for EB-1 not only in microtubule dynamics, but also chromosome segregation (Rogers et al., 2002; see also Louie et al., 2004). +TIPs can also interact with members of protein complexes at cortical platforms. One such protein is APC, which through independent binding domains has the capacity to bind to both EB-1 and cortical proteins (Barth et al., 2002).

A particularly powerful system for dissecting the sequence of molecular events involved in cellular polarization is the introduction of scratches or wounds into a monolayer of adherent mammalian cells in culture. In wounded astrocyte cultures, for instance, the small GTPase Cdc42 is activated at the leading edge, a process that triggers the binding of a polarizing protein Par6, which in turn activates PKCζ, which then phosphorylates and inactivates GSK3β (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001, 2003). This cascade has been proposed to enable APC to then associate with microtubule tips and allow the selective capturing and stabilization of microtubules at the leading edge of the migrating front.

Some individual cells move in a random but polarized fashion, which at first glance appears to be analogous to the polarization process described for a wound response. However, in one report the downstream effector was IQGAP, which is also a direct binding partner for activated Cdc42 at the leading edge (Fukata et al., 2002). Additional direct interactions between IQGAP and the +TIP CLIP-170 then appeared to link the temporal capture of the microtubule plus ends to this activated cortical platform. Interestingly, expression of a mutant IQGAP that could not bind activated GTPases resulted in multiple protrusion sites (Fukata et al., 2002). This provides further evidence that coupling microtubule stabilization to a cortical platform is required for sustaining polarity.

Additional direct GTPase targets such as mDia have also surfaced as binding partners or regulators for the +TIP EB-1 (Wen et al., 2004). Other proteins that localize to and are likely to be involved in these types of F-actin–microtubule connections include the minus end–directed microtubule motor protein dynein, the CLIP-associated proteins (or CLASPs), and the gigantic spectraplakin protein ACF7 (Leung et al., 1999; Karakesisoglou et al., 2000; Kodama et al., 2003; Gundersen et al., 2004).

Whether in isolation or as an adhering sheet, cells also often polarize their MTOC in the direction of migration. In wounded astrocyte cultures, dominant-negative disruption of dynein function abrogates the MTOC reorientation process (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2001), and this and other reports implicate dynein/dynactin in the signaling pathway that leads to MTOC positioning (Burakov et al., 2003). Although a direct connection between dynein/dynactin and the Cdc42/Par6/PKCζ/GSK3β pathway has not yet surfaced, increasing evidence points to the view that the cortical platform that develops at a wound edge can act as a scaffolding complex. This concept sets the scene for multiple +TIPs to encounter many different receptor proteins that may converge at this platform.

To illustrate the myriad of potential interactions afforded by such a scaffold, APC can bind to the adherens junction protein β-catenin (Dikovskaya et al., 2001). β-Catenin in turn can bind to members of the dynein/dynactin complex (Ligon et al., 2001), although so can EB-1 (Berrueta et al., 1999), and EB-1 in turn can bind to CLIP170 and Lis1 (Coquelle et al., 2002; Goodson et al., 2003). As if one of these various circuitous routes weren't sufficient to recruit dynein/dynactin to polarized sites, yeast two-hybrid analyses have uncovered a direct association between the p150glued dynactin subunit and the ezrin/moesin/radixin domain of a neuronal spectraplakin that also possesses binding sites for EB-1, as well as F-actin and microtubules (Liu et al., 2003; Subramanian et al., 2003).

In summary, although a common core pathway seems likely for polarizing cell movements, the mind-boggling opportunities for direct and indirect interactions between +TIPs and cortical platform proteins seem to reflect a tailoring of this process to suit the particular needs of different cells and tissues. A comparison of this process across the eukaryotic kingdom supports the notion that a general mechanism underlies the integration of polarization processes with microtubule search and capture dynamics. The molecular twists that appear to be superimposed upon this theme seem likely to exist for the purpose of coordinating these dynamics in a regulated fashion. Additional factors may be structural, using multiple protein complexes to modify or reinforce the strength of microtubule–actin interactions. Finally, the length of time during which a localized GTPase is activated might also influence the degree to which a cortical platform amplifies microtubule retention at a polarized site (Fig. 1; bottom).

One final issue worth considering is the impact of the evolutionary spectrum on the mechanisms underlying microtubule plus end capturing by cortical platforms. In this regard, the significantly larger size of mammalian cells compared with single-cell eukaryotes such as yeasts necessitates the production of longer and more stable microtubules to span the cytoplasm. In addition, when yeast cells polarize to divide, the orientation and establishment of actin–microtubule connections is exquisitely linked to the regulation of yeast's rapid cell cycles. As such, the tethering of microtubules to the cortical platform is both transient and cyclic. Similarly, the mating process in yeast needs only to sustain the polarization machinery for several hours. By contrast, higher eukaryotes must often maintain their tethering machinery for extended periods in order to accommodate more protracted polarization processes such as epithelial wound closure.

Spectraplakins: scaffolds for direct cross-linking of actin filaments and microtubules

The need to prolong microtubule–actin anchorage provides a potential explanation for why mammals have developed more efficient machineries to strengthen interactions between microtubule- and actin-based structures. In this regard, the spectraplakins have emerged as higher eukaryotic scaffolding proteins, which have direct binding sites for +TIPs, F-actin, and microtubules (Leung et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999; Karakesisoglou et al., 2000; Subramanian et al., 2003) (Fig. 1; bottom). At least some spectraplakins can also associate with intermediate filaments, dynein/dynactin, and cell–substratum and cell–cell contacts (Gregory and Brown, 1998; Leung et al., 1999; Karakesisoglou et al., 2000; Kodama et al., 2003; Roper and Brown, 2003). With sizes of >500 kD, these goliaths may act as master scaffolds to integrate a variety of different proteins and cytoskeletons at polarized junctures. An interesting twist to spectraplakins is that multiple modes of alternative splicing of a single transcript appears to translate into a myriad of isoforms, able to serve as spatially and structurally tailored scaffolds (Roper et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2003; Jefferson et al., 2004).

Genetic analyses reveal that spectraplakins are not simple bystanders at cortical platforms. For example, mutations in the Drosophila shot gene result in wing blisters and defects in neuromuscular junctions, both of which involve integrin-mediated connections between distinct cell types (Gregory and Brown, 1998; Prokop et al., 1998). Mutations that specifically abrogate the function of the Caenorhabditis elegans VAB-10 isoform, containing actin and microtubule binding domains, cause increased epidermal thickening at a time when the cells normally undergo shape changes (Bosher et al., 2003). And a mammalian BPAG1 isoform able to associate with microtubules and dynein/dynactin has been implicated in retrograde transport in sensory neurons (Yang et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2003). In contrast, endodermal cells cultured from a mouse embryo that lacks all known ACF7 isoforms display more global defects, some of which can be directly attributed to a need for actin–microtubule connections. These include abnormalities in the ability of microtubules to grow along actin cables and a failure of growing microtubules to tether to the cortex (Kodama et al., 2003) (Fig. 1; bottom). Interestingly, wounded ACF7 null endodermal cultures initiate a polarization process, but cannot sustain the localization of PKCζ, and neither reorient their MTOC nor stabilize microtubules at the wound front (Kodama et al., 2003).

Exactly how spectraplakins function in orchestrating converging signals at cortical platforms is unknown. A priori, they could act early in polarization by directly tethering +TIP-associated microtubules to cortical F-actin. Alternatively, spectraplakins might act through dynein/dynactin complexes to reorient the MTOC or stabilize microtubules. Finally, spectraplakins may function structurally to reinforce the molecular hinge between polarized F-actin and microtubules. Given that spectraplakins can be recruited to focal adhesions, cell–cell junctions, and migrating cell and wound fronts, these tantalizing new findings fuel the fire for future analyses in this area.

Conclusions and prospects

Recent reports have contributed greatly to our understanding of how directed cell migration is orchestrated through cytoskeletal rearrangements triggered by polarized activation of small GTPases. A challenge for the future is to understand how these mechanisms are tailored to enable cells to perform this intricate process in response to specialized cues from their localized environment. Embedded within this issue are how polarized cortical platforms are sustained for different lengths of times and how the process is switched off. Whether the leading edge of a wound site or a cell–cell or cell–substratum junction, a polarized cortical platform presents a molecular galaxy in which to integrate a constellation of signal transduction pathways with cytoskeletal rearrangements. The science underlying this field is likely to hold many new insights into cell biology and is likely to keep researchers concentrated in this area for many years to come.

Acknowledgments

A special tribute goes to the Fuchs lab members, past and present, who contributed to the scientific foundation that inspired us to write this review. We are also grateful to our colleagues throughout the scientific community who have developed this field to the exciting state that it has become. Finally, we would like to thank Dr. Markus Schober for his critical reading of this review.

E. Fuchs is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. T. Lechler is a postdoctoral fellow supported by the Jane Coffin Childs Foundation. Past work contributing to this review has been supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01-AR27883).

Abbreviations used in this paper: +TIP, plus end–interacting protein; MTOC, microtubule organizing center.

References

- Barth, A.I., K.A. Siemers, and W.J. Nelson. 2002. Dissecting interactions between EB1, microtubules and APC in cortical clusters at the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 115:1583–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrueta, L., J.S. Tirnauer, S.C. Schuyler, D. Pellman, and B.E. Bierer. 1999. The APC associated protein EB1 associates with components of the dynactin complex and cytoplasmic dynein intermediate chain. Curr. Biol. 9:425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosher, J.M., B.S. Hahn, R. Legouis, S. Sookhareea, R.M. Weimer, A. Gansmuller, A.D. Chisholm, A.M. Rose, J.L. Bessereau, and M. Labouesse. 2003. The Caenorhabditis elegans vab-10 spectraplakin isoforms protect the epidermis against internal and external forces. J. Cell Biol. 161:757–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burakov, A., E. Nadezhdina, B. Slepchenko, and V. Rodionov. 2003. Centrosome positioning in interphase cells. J. Cell Biol. 162:963–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquelle, F.M., M. Caspi, F.P. Cordelieres, J.P. Dompierre, D.L. Dujardin, C. Koifman, P. Martin, C.C. Hoogenraad, A. Akhmanova, N. Galjart, et al. 2002. LIS1, CLIP-170's key to the dynein/dynactin pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3089–3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub, H., K. Gevaert, J. Vandekerckhove, A. Sobel, and A. Hall. 2001. Rac/Cdc42 and p65PAK regulate the microtubule-destabilizing protein stathmin through phosphorylation at serine 16. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1677–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo, M.A., N.B. Alderson, W.B. Kiosses, H.H. Chiang, R.G. Anderson, and M.A. Schwartz. 2004. Integrins regulate Rac targeting by internalization of membrane domains. Science. 303:839–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikovskaya, D., J. Zumbrunn, G.A. Penman, and I.S. Nathke. 2001. The adenomatous polyposis coli protein: in the limelight out at the edge. Trends Cell Biol. 11:378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville, S., and A. Hall. 2001. Integrin-mediated activation of Cdc42 controls cell polarity in migrating astrocytes through PKCξ. Cell. 106:489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville, S., and A. Hall. 2003. Cdc42 regulates GSK-3β and adenomatous polyposis coli to control cell polarity. Nature. 421:753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata, M., T. Watanabe, J. Noritake, M. Nakagawa, M. Yamaga, S. Kuroda, Y. Matsuura, A. Iwamatsu, F. Perez, and K. Kaibuchi. 2002. Rac1 and Cdc42 capture microtubules through IQGAP1 and CLIP-170. Cell. 109:873–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata, M., M. Nakagawa, and K. Kaibuchi. 2003. Roles of Rho-family GTPases in cell polarisation and directional migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15:590–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, E.M., K.N. Pestonjamasp, B.P. Bohl, C. Chamberlain, K.M. Hahn, and G.M. Bokoch. 2002. Spatial and temporal analysis of Rac activation during live neutrophil chemotaxis. Curr. Biol. 12:2029–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson, H.V., S.B. Skube, R. Stalder, C. Valetti, T.E. Kreis, E.E. Morrison, and T.A. Schroer. 2003. CLIP-170 interacts with dynactin complex and the APC-binding protein EB1 by different mechanisms. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 55:156–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, S.L., and N.H. Brown. 1998. kakapo, a gene required for adhesion between and within cell layers in Drosophila, encodes a large cytoskeletal linker protein related to plectin and dystrophin. J. Cell Biol. 143:1271–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen, G.G., E.R. Gomes, and Y. Wen. 2004. Cortical control of microtubule stability and polarization. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. 1998. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 279:509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood, J.D., and D.A. Cheresh. 2002. Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, R.E., K. Kurokawa, Y. Ohba, H. Yoshizaki, N. Mochizuki, and M. Matsuda. 2002. Activation of rac and cdc42 video imaged by fluorescent resonance energy transfer-based single-molecule probes in the membrane of living cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:6582–6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaksits, S., W. Bauer, E. Kriehuber, M. Zeyda, T.M. Stulnig, G. Stingl, E. Fiebiger, and D. Maurer. 2004. Lipid raft-associated GTPase signaling controls morphology and CD8+ T cell stimulatory capacity of human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 173:1628–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, J.J., C.L. Leung, and R.K. Liem. 2004. Plakins: goliaths that link cell junctions and the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:542–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakesisoglou, I., Y. Yang, and E. Fuchs. 2000. An epidermal plakin that integrates actin and microtubule networks at cellular junctions. J. Cell Biol. 149:195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaverina, I., O. Krylyshkina, and J.V. Small. 1999. Microtubule targeting of substrate contacts promotes their relaxation and dissociation. J. Cell Biol. 146:1033–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner, J., Z. Kam, G. Tzur, A.D. Bershadsky, and B. Geiger. 2003. Live-cell monitoring of tyrosine phosphorylation in focal adhesions following microtubule disruption. J. Cell Sci. 116:975–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, M., and T. Mitchison. 1986. Beyond self-assembly: from microtubules to morphogenesis. Cell. 45:329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, A., I. Karakesisoglou, E. Wong, A. Vaezi, and E. Fuchs. 2003. ACF7: an essential integrator of microtubule dynamics. Cell. 115:343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova, Y.A., A.S. Akhmanova, S. Kojima, N. Galjart, and G.G. Borisy. 2002. Cytoplasmic linker proteins promote microtubule rescue in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 159:589–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautkramer, E., S.I. Giese, J.E. Gasteier, W. Muranyi, and O.T. Fackler. 2004. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef activates p21-activated kinase via recruitment into lipid rafts. J. Virol. 78:4085–4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraynov, V.S., C. Chamberlain, G.M. Bokoch, M.A. Schwartz, S. Slabaugh, and K.M. Hahn. 2000. Localized Rac activation dynamics visualized in living cells. Science. 290:333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krendel, M., F.T. Zenke, and G.M. Bokoch. 2002. Nucleotide exchange factor GEF-H1 mediates cross-talk between microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C.L., D.M. Sun, M. Zheng, D.R. Knowles, and R.K.H. Liem. 1999. Microtubule actin cross-linking factor (MACF): A hybrid of dystonin and dystrophin that can interact with the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. J. Cell Biol. 147:1275–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., M. Hannigan, Z. Mo, B. Liu, W. Lu, Y. Wu, A.V. Smrcka, G. Wu, L. Li, M. Liu, et al. 2003. Directional sensing requires Gβγ-mediated PAK1 and PIXα-dependent activation of Cdc42. Cell. 114:215–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon, L.A., S. Karki, M. Tokito, and E.L. Holzbaur. 2001. Dynein binds to β-catenin and may tether microtubules at adherens junctions. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J., J.Q. Ding, A.S. Kowal, T. Nardine, E. Allen, J.D. Delcroix, C.B. Wu, W. Mobley, E. Fuchs, and Y.M. Yang. 2003. BPAG1 n4 is essential for retrograde axonal transport in sensory neurons. J. Cell Biol. 163:223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie, R.K., S. Bahmanyar, K.A. Siemers, V. Votin, P. Chang, T. Stearns, W.J. Nelson, and A.I. Barth. 2004. Adenomatous polyposis coli and EB1 localize in close proximity of the mother centriole and EB1 is a functional component of centrosomes. J. Cell Sci. 117:1117–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meili, R., and R.A. Firtel. 2003. Two poles and a compass. Cell. 114:153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, A.F., T.A. Cook, A.S. Alberts, and G.G. Gundersen. 2001. mDia mediates Rho regulated formation and orientation of stable microtubules. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:723–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, A.F., C.H. Eng, D.D. Schlaepfer, E.E. Marcantonio, and G.G. Gundersen. 2004. Localized stabilization of microtubules by integrin- and FAK-facilitated Rho signaling. Science. 303:836–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokop, A., J. Uhler, J. Roote, and M. Bate. 1998. The kakapo mutation affects terminal arborization and central dendritic sprouting of Drosophila motorneurons. J. Cell Biol. 143:1283–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, O.C., A.W. Schaefer, C.A. Mandato, P. Forscher, W.M. Bement, and C.M. Waterman-Storer. 2003. Conserved microtubule-actin interactions in cell movement and morphogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.L., G.C. Rogers, D.J. Sharp, and R.D. Vale. 2002. Drosophila EB1 is important for proper assembly, dynamics, and positioning of the mitotic spindle. J. Cell Biol. 158:873–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper, K., and N.H. Brown. 2003. Maintaining epithelial integrity: a function for gigantic spectraplakin isoforms in adherens junctions. J. Cell Biol. 162:1305–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper, K., S.L. Gregory, and N.H. Brown. 2002. The ‘spectraplakins’: cytoskeletal giants with characteristics of both spectrin and plakin families. J. Cell Sci. 115:4215–4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler, S.C., and D. Pellman. 2001. Microtubule “plus-end-tracking proteins”: the end is just the beginning. Cell. 105:421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A., A. Prokop, M. Yamamoto, K. Sugimura, T. Uemura, J. Betschinger, J.A. Knoblich, and T. Volk. 2003. Shortstop recruits EB1/APC1 and promotes microtubule assembly at the muscle-tendon junction. Curr. Biol. 13:1086–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer, J.S., S. Grego, E.D. Salmon, and T.J. Mitchison. 2002. EB1-microtubule interactions in Xenopus egg extracts: Role of EB1 in microtubule stabilization and mechanisms of targeting to microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:3614–3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman-Storer, C.M., R.A. Worthylake, B.P. Liu, K. Burridge, and E.D. Salmon. 1999. Microtubule growth activates Rac1 to promote lamellipodial protrusion in fibroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrle-Haller, B., and B.A. Imhof. 2003. Actin, microtubules and focal adhesion dynamics during cell migration. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 35:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y., C.H. Eng, J. Schmoranzer, N. Cabrera-Poch, E.J. Morris, M. Chen, B.J. Wallar, A.S. Alberts, and G.G. Gundersen. 2004. EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:820–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, T., G.M. Bokoch, and C.M. Waterman-Storer. 2003. Regulation of leading edge microtubule and actin dynamics downstream of Rac1. J. Cell Biol. 161:845–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, T., G.M. Bokoch, and C.M. Waterman-Storer. 2004. Regulation of microtubule destabilizing activity of Op18/stathmin downstream of Rac1. J. Biol. Chem. 279:6196–6203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J., F. Wang, A. Van Keymeulen, P. Herzmark, A. Straight, K. Kelly, Y. Takuwa, N. Sugimoto, T. Mitchison, and H.R. Bourne. 2003. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils. Cell. 114:201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., C. Bauer, G. Strasser, R. Wollman, J.P. Julien, and E. Fuchs. 1999. Integrators of the cytoskeleton that stabilize microtubules. Cell. 98:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]