Abstract

Dynamic regulation of integrin adhesiveness is required for immune cell–cell interactions and leukocyte migration. Here, we investigate the relationship between cell adhesion and integrin microclustering as measured by fluorescence resonance energy transfer, and macroclustering as measured by high resolution fluorescence microscopy. Stimuli that activate adhesion through leukocyte function–associated molecule-1 (LFA-1) failed to alter clustering of LFA-1 in the absence of ligand. Binding of monomeric intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) induced profound changes in the conformation of LFA-1 but did not alter clustering, whereas binding of ICAM-1 oligomers induced significant microclustering. Increased diffusivity in the membrane by cytoskeleton-disrupting agents was sufficient to drive adhesion in the absence of affinity modulation and was associated with a greater accumulation of LFA-1 to the zone of adhesion, but redistribution did not precede cell adhesion. Disruption of conformational communication within the extracellular domain of LFA-1 blocked adhesion stimulated by affinity-modulating agents, but not adhesion stimulated by cytoskeleton-disrupting agents. Thus, LFA-1 clustering does not precede ligand binding, and instead functions in adhesion strengthening after binding to multivalent ligands.

Introduction

Regulation of the adhesiveness of the integrin leukocyte function–associated molecule-1 (LFA-1) is critical for dynamic immune system functions such as leukocyte trafficking, migration within tissues, and formation of immunological synapses. The overall strength (or “avidity”) of cellular adhesive interactions results from the combination of both the affinity of individual receptor–ligand bonds and the total number of bonds formed, i.e., the “valency” of the interaction. Affinity regulation of integrins refers to changes in individual αβ heterodimer affinity that are coupled to alterations in integrin conformation, whereas valency regulation is mediated by changes in cell surface receptor diffusivity or local density that alter the number of adhesive bonds that can form (Dustin and Springer, 1989; Lollo et al., 1993; Bazzoni and Hemler, 1998; Stewart et al., 1998; van Kooyk and Figdor, 2000; Carman and Springer, 2003; Katagiri et al., 2003). The leukocyte integrin LFA-1 (lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1; αLβ2) is perhaps the most widely studied integrin with respect to affinity and valency regulation. The cell surface ligands recognized by LFA-1 are members of the Ig superfamily known as intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAMs) and are expressed on a wide variety of somatic cells, and in the case of ICAM-1 are inducible by inflammatory cytokines (Springer, 1990; de Fougerolles and Springer, 1992).

Integrins are heterodimeric receptors, consisting of α and β subunits that together form a globular, ligand-binding head region and individually form two legs that connect to the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of each subunit. In the low affinity integrin conformation the head folds over the legs owing to a bend at the knees, whereas the high affinity conformation is extended (Shimaoka and Springer, 2003). Transition to the extended state involves separation of the α and β subunits at their cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and leg domains (Takagi et al., 2002; Vinogradova et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2004). These events lead to disruption of the association between the integrin head and legs, and a switchblade-like extension (Takagi et al., 2002). These global conformational changes are coupled to specific inter- and intra-domain rearrangements that stabilize the high affinity states of the β I-like and α I domains in the head region (Shimaoka and Springer, 2003; Xiao et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2004).

Valency regulation is operationally defined, in part, by fluorescence microscopy–based observation of changes in integrin cell surface distribution. Though collectively referred to as “clustering,” reported redistribution patterns are variable, including large, dot-like unevenly distributed clusters (van Kooyk et al., 1994, 1999), polarized patches on one side of the cell surface (Constantin et al., 2000; Myou et al., 2002), and differential concentration of LFA-1 to the leading and trailing portions of polarized or migrating cells (Katagiri et al., 2003). Clustering has also been reported when the distribution appears even, and fluorescence measurements by microscopy differ from those by flow cytometry (Stewart et al., 1998; McDowall et al., 2003). In practice, valency regulation has also been inferred when activators promote cell adhesion without promoting direct soluble ligand binding. However, more sensitive ligand displacement assays can detect an increase in affinity with some such activators, i.e., PMA (Lollo et al., 1993).

The nature of integrin “clusters,” what drives their formation, and their role in dynamic adhesions remain unclear (Carman and Springer, 2003). Integrins on leukocytes can be activated with chemokines or agents that mimic inside-out signals, such as PMA, and adhesion can also be stimulated by agents that disrupt the actin cytoskeleton (Faull et al., 1994; Kucik et al., 1996; Zhou and Li, 2000; Ni et al., 2003). PMA and cytoskeleton-disrupting agents also increase diffusion of integrins in the cell membrane (Faull et al., 1994; Kucik et al., 1996; Zhou and Li, 2000; Zhou et al., 2001). Thus, one possibility is that increased integrin diffusivity acts simply to facilitate ligand-dependent, mass-action–driven accumulation of integrins into the site of contact with multivalent ligand-bearing substrates, functioning in “adhesion strengthening” (Kucik et al., 1996). It is noteworthy that all leukocytes that express LFA-1 also express one or more of its ligands, ICAM-1, ICAM-2, and ICAM-3, and that activation of LFA-1 often leads to formation of aggregates of homotypically adherent cells (Springer, 1990; de Fougerolles and Springer, 1992). Thus, ligand-dependent redistribution, as a consequence of binding to ICAMs on adjacent cells in homotypic aggregates that are disrupted before experimental observation by fluorescence microscopy, is one of several plausible explanations for observations of LFA-1 clustering (Carman and Springer, 2003).

An alternative hypothesis is that release of cytoskeletal constraints is rapidly followed by, or coupled to, intrinsic proactive induction of cell surface integrin clusters or oligomers in a ligand-independent manner, and serves to enhance the propensity to form initial adhesions with multivalent substrates (Bazzoni and Hemler, 1998; van Kooyk et al., 1999; Constantin et al., 2000; van Kooyk and Figdor, 2000; Hogg et al., 2002; Li et al., 2003). One of the proposed mechanisms for proactive integrin clustering involves the regulated recruitment of integrins into lipid raft domains (Hogg et al., 2002). In addition, based on the observation that peptides containing integrin α and β subunit transmembrane domains form homodimers and homotrimers in detergent micelles, it has also been suggested that transition of integrins to an extended conformation, and particularly separation of the α and β subunit cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains, is sufficient to drive microclustering by facilitating homomeric associations between the transmembrane domains of neighboring integrins (Li et al., 2001, 2003).

In this paper we establish fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and high resolution confocal fluorescence microscopy as quantitative methods for the analysis of LFA-1 distribution. Because the resolution scale of FRET and light microscopy differ by at least two orders of magnitude, we distinguish clustering data obtained by these two techniques as “microclustering” (scale of tens of angstroms) and “macroclustering” (scale of >200 nm). Importantly, the presence of macroclusters does not necessitate the existence of microclusters, and vice versa. Therefore, light microscopy and FRET microscopy should be considered complementary techniques. In parallel with cell adhesion, soluble ligand binding, and activation epitope exposure assays, we have addressed two central and longstanding questions: First, is rapid LFA-1 redistribution or clustering actively driven in cells, functioning to increase the propensity to form initial adhesions, or does it occur subsequent to formation of initial adhesions, in a mass-action–dependent manner, functioning primarily in adhesion strengthening? And second, is the conformation of LFA-1 linked to macro- or microclustering?

Results

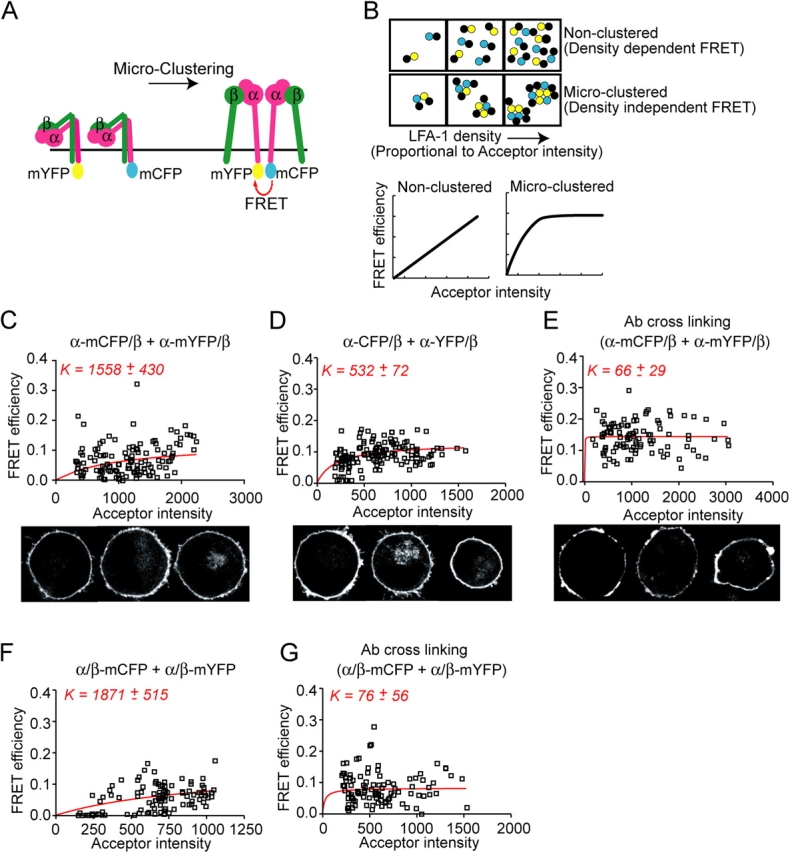

To quantitatively measure integrin clustering on the cell surface at the scale of molecular interactions, i.e., microclustering, we developed FRET-based assays. Nondimerizing or “monomeric” (m) mutants (Zacharias et al., 2002) of CFP (mCFP) and YFP (mYFP) were fused to the COOH termini of the αL and β2 subunit cytoplasmic domains (Fig. 1 A). To measure inter-heterodimer distances, K562 cells were transiently transfected with αL-mCFP, αL-mYFP, and wild-type β2, generating cell surface expression of αL-mCFP/β2 and αL-mYFP/β2 in approximately equal amounts. The redistribution of integrin heterodimers into microclusters, in which the αL subunits come within 100 Å of each other, should result in detectable CFP/YFP FRET. Similarly, cells were transfected with wild-type αL, β2-mCFP and β2-mYFP, such that FRET would measure proximity of β2 subunits of separate integrin heterodimers.

Figure 1.

Experimental design and validation of inter-heterodimer FRET microclustering assay. (A) A hypothetical model (Li et al., 2003) for integrin clustering. Cells expressing heterodimers with either the α (shown) or β subunits tagged with both mCFP and mYFP will exhibit FRET only when heterodimers are brought into close proximity (< 100 Å). (B) Schematic (top) and model curves (bottom) for FRET behavior under nonclustered and microclustered conditions (Kenworthy et al., 2000; Zacharias et al., 2002). See Results. (C–G) Inter-heterodimer FRET and acceptor intensities for individual ROIs from K562 cells expressing αL-mCFP/β2 and αL-mYFP/β2 (C and E), αL-CFP/β2 and αL-YFP/β2 (D), or αL/β2-mCFP and αL/β2-mYFP (F and G) were fit to  (red curves) using the Lineweaver-Burke equation as described in Materials and methods. Where indicated, cell surface LFA-1 was cross-linked by preincubation with either 10 μg/ml of TS2/4 mAb to αL (E) or CBR LFA-1/7 mAb to β2 (G) and secondary, purified goat anti–mouse antibody (10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. Representative confocal images, depicting the YFP signal from selected experiments (C–E), are shown below the graphs.

(red curves) using the Lineweaver-Burke equation as described in Materials and methods. Where indicated, cell surface LFA-1 was cross-linked by preincubation with either 10 μg/ml of TS2/4 mAb to αL (E) or CBR LFA-1/7 mAb to β2 (G) and secondary, purified goat anti–mouse antibody (10 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. Representative confocal images, depicting the YFP signal from selected experiments (C–E), are shown below the graphs.

For nonclustered molecules, the relationship between cell surface density and FRET is largely linear (Kenworthy et al., 2000; Zacharias et al., 2002) (Fig. 1 B). By contrast, microclustered molecules are in close proximity to one another, and therefore exhibit FRET at lower densities (Kenworthy et al., 2000; Zacharias et al., 2002) (Fig. 1 B). This relationship has been expressed as a saturable one-site binding model,

|

(1) |

where FRET efficiency (E) is a hyperbolic function of the cell surface density (F), which is usually taken from the fluorescence intensity of the directly excited acceptor (YFP), and K is analogous to the dissociation constant of microclusters (Zacharias et al., 2002). Thus, the lower the K value, the greater the tendency to cluster. Clustering becomes predominant when F > K (Zacharias et al., 2002).

Under basal conditions, αL-mCFP/β2 and αL-mYFP/β2, or αL/β2-mCFP and αL/β2-mYFP, showed largely linear FRET/acceptor density relationships and very large K values of 1558 ± 430 and 1871 ± 515, respectively, suggesting little microclustering (Fig. 1 C, top, and Fig. 1 F). High resolution confocal microscopy imaging also demonstrated a lack of LFA-1 macroclustering (Fig. 1 C, bottom). However, cross-linking of LFA-1 with antibodies to αL or β2 and polyclonal anti-Ig produced readily detectable microclustering between αL subunits (Fig. 1 E; K = 66 ± 29) and between β2 subunits (Fig. 1 G; K = 76 ± 56). Furthermore, antibody cross-linking also induced macroclustering (Fig. 1 E, bottom). In contrast to monomeric mCFP and mYFP mutants, CFP and YFP have a tendency to dimerize (Zacharias et al., 2002). When cells were transfected with constructs containing CFP and YFP (αL-CFP/β2 and αL-YFP/β2), an intermediate level of microclustering occurred (Fig. 1 D, top; K = 532 ± 72). This microclustering occurred in the absence of detectable macroclustering (Fig. 1 D, bottom). The results with microclustering induced by antibody and dimerizing CFP and YFP variants demonstrate a wide dynamic range of sensitivity for our FRET assay.

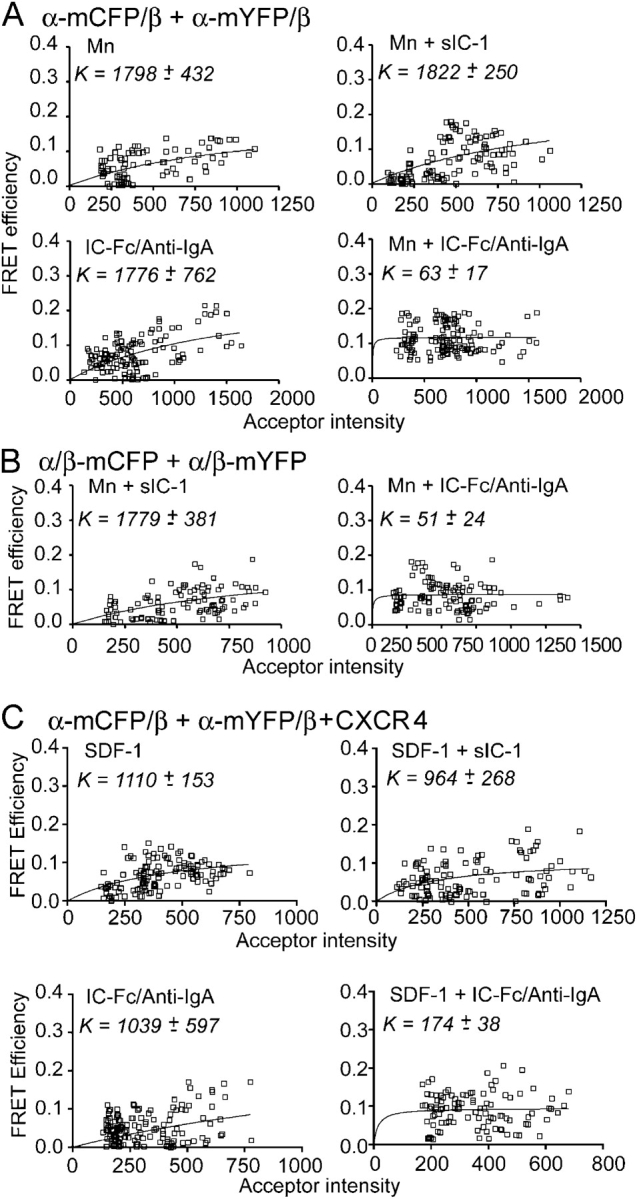

We used ligand-induced activation of LFA-1 to test for a linkage between changes in integrin conformation, specifically separation of α and β subunit cytoplasmic domains within a heterodimer (Kim et al., 2003), and the formation of clusters of LFA-1 molecules through homomeric interaction (Li et al., 2003). Mn2+ has been shown to promote conformational changes in the extracellular domain of LFA-1 that increases its affinity for ICAM-1 (Dransfield et al., 1992). Mn2+-promoted binding of ICAM-1 to LFA-1 induces separation of the αL and β2 cytoplasmic domains (Kim et al., 2003), as confirmed here with intra-heterodimer FRET using αL-mCFP/β2-mYFP transfectants (Fig. S1 A, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200404160/DC1). By contrast, parallel inter-heterodimer αL-αL FRET experiments showed absolutely no microclustering promoted with Mn2+ plus sICAM-1 using αL-mCFP/β2 + αL-mYFP/β2 transfectants (Fig. 2 A, Mn2+ + sIC compared with Mn2+). Similarly, Mn2+ plus sICAM-1 did not promote any β2-β2 FRET in the αL/β2- mCFP + αL/β2-mYFP transfectants (Fig. 2 B). Mn2+ + sICAM-1 also failed to induce macroclustering (Fig. S1 C).

Figure 2.

Multimeric ligand binding to activated LFA-1 but not activation alone induces LFA-1 microclustering. K562 cells expressing αL-mCFP/β2 and αL-mYFP/β2 (A), αL/β2-mCFP and αL/β2-mYFP (B), or αL-mCFP/β2 and αL-mYFP/β2 + CXCR4 (C) were preincubated with either 1 mM Mn2+, 1 mM Mn2+ + 100 μg/ml sIC-1, IC-Fc/Anti-IgA complex, 1 mM Mn2+ + IC-Fc/Anti-IgA complex, 1 μg/ml SDF-1, 1 μg/ml SDF-1 + 500 μg/ml sIC-1, or 1 μg/ml SDF-1 + IC-Fc/Anti-IgA complex, and were subjected to FRET measurements.

Clustering with multimeric ICAM-1 was tested using ICAM-1-Fcα chimera/anti-IgA immune complexes, which bind strongly to LFA-1–bearing cells in Mn2+ (Fig. S1 B). Binding of oligomeric ICAM-1 induced robust microclustering of LFA-1 in the presence of Mn2+ as measured by both FRET between αL subunits (Fig. 2 A; K = 63 ± 17) and FRET between β2 subunits (Fig. 2 B; K = 51 ± 24), but did not induce detectable macroclustering (Fig. S1 C). Thus, stabilization of the extended, high affinity integrin conformation by soluble monomeric ligand is insufficient to induce either micro- or macroclustering of LFA-1, whereas binding of soluble multivalent ligand promotes efficient microclustering but not macroclustering.

To assess the effect of chemokine receptor signaling on the clustering of LFA-1, K562 cells were transiently transfected with αL-mCFP, αL-mYFP, wild-type β2, and HA-tagged CXCR4. HA-CXCR4 transfectants were identified by immunofluorescence with anti-HA antibody and Cy5-labeled anti-Ig (Fig. S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200404160/DC1). Addition of the chemokine SDF-1 only or SDF-1 plus sICAM-1 did not promote FRET in the αL-mCFP/β2 + αL-mYFP/β2 + CXCR4 transfectants (Fig. 2 C). By contrast, SDF-1 induces separation of the αL and β2 cytoplasmic domains in αL-mCFP/β2-mYFP + CXCR4 transfectants (Kim et al., 2003). SDF-1 + sICAM-1 also failed to induce macroclustering (unpublished data). However, addition of SDF-1 + oligomeric ICAM-1 induced robust microclustering of LFA-1 (Fig. 2 C) without detectable macroclustering (Fig. S2 and Video 1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200404160/DC1).

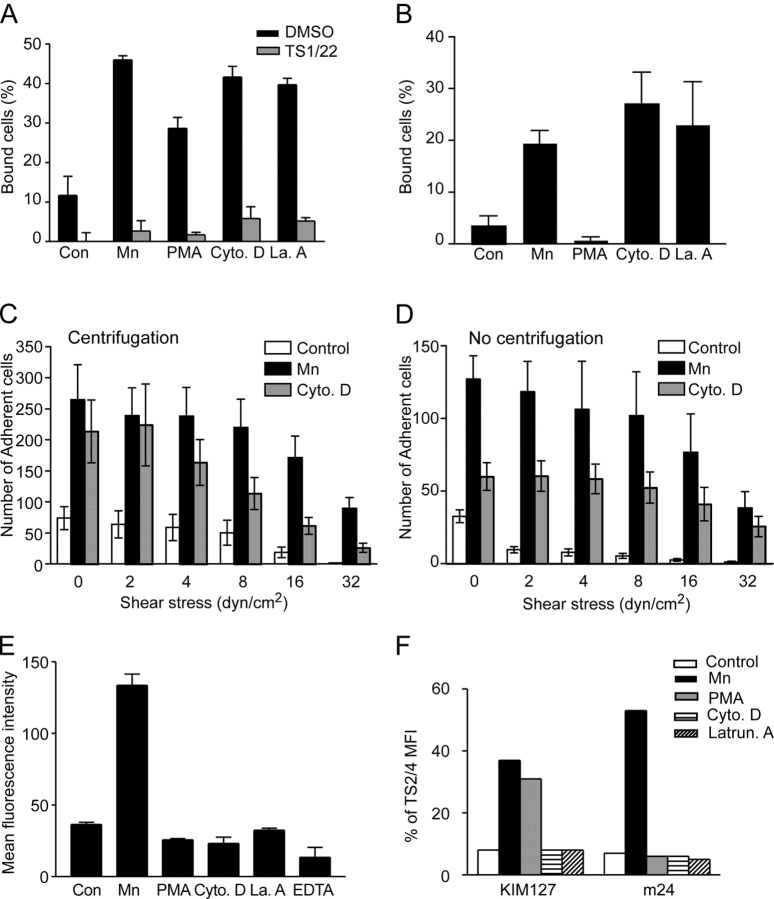

Valency-based modes of integrin regulation are known to act, at least in part, through increasing integrin cell surface diffusivity (Kucik et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 2001). Cytochalasin D and latrunculin A have been used previously to dissect integrin regulatory mechanisms, and are thought to act by selectively increasing integrin diffusivity without altering conformation (Kucik et al., 1996; van Kooyk and Figdor, 2000; Zhou et al., 2001). PMA has been reported both to modulate affinity and to increase diffusivity (Lollo et al., 1993; Kucik et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 2001). Consistent with previous reports (Kucik et al., 1996; van Kooyk and Figdor, 2000; Zhou et al., 2001), cell pretreatment with 1 μM cytochalasin D or 1 μM latrunculin A caused partial disruption of actin filaments in K562 cells (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200404160/DC1) and significantly increased LFA-1 lateral mobility (Fig. S4) as measured by Alexa 488–phalloidin staining and FRAP, respectively. The same concentrations of cytochalasin D and latrunculin A induced significant adhesion in both V-bottom (Fig. 3 A) and conventional flat-bottom well (Fig. 3 B) assays, which was comparable to that induced by 1 mM Mn2+. Substantial adhesion promoted by 1 μM PMA was readily detected by the V-bottom assay (Fig. 3 A), but not by the less sensitive flat-bottom assay (Fig. 3 B). In the flat-bottom assay cells are washed with high shear, whereas in the V-bottom assay nonadherent cells are separated by centrifugation and there is no washing. Adhesion stimulated by cytochalasin D was further analyzed under physiologic shear conditions in a parallel wall flow chamber (Fig. 3, C and D). Cytochalasin D promoted significant amounts of highly shear-resistant cellular adhesions either with (Fig. 3 C) or without (Fig. 3 D) brief precentrifugation to promote initial contacts, and was only somewhat less effective than Mn2+.

Figure 3.

Disruption of cytoskeletal constraints enhances cell adhesion but does not promote soluble ligand binding or conformational change. (A and B) K562 transfectants expressing wild-type αLβ2 were preincubated with Mn2+, PMA, cytochalasin D, or latrunculin A in the absence or presence of inhibitory αL mAb TS1/22 (10 μg/ml) and allowed to bind ICAM-1 immobilized on V-bottom (A) or flat-bottom (B) plates, as described in Materials and methods. Data represent mean ± SEM of all measurements from three independent experiments in duplicate (A) or three independent experiments in triplicate (B). (C and D) Stable K562 cell transfectants expressing wild-type αLβ2 were allowed to adhere, with (C) and without (D) an initial centrifugation, to coverslips coated with ICAM-1 in the absence (Control) or presence of 1 mM Mn2+ or 1 μM cytochalasin D for 30 min at 37°C under static conditions. Coverslips were transferred to a laminar flow chamber and cells were then detached by a shear regimen of 30 s each of 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 dyn/cm2. The number of cells remaining after each interval were counted. Values are mean ± SEM for three separate experiments. (E) Binding of soluble, multimeric ICAM-1-Fcα chimera/anti-IgA-FITC complex was conducted in the presence of Mn2+, PMA, cytochalasin D, or latrunculin A at 37°C and measured by flow cytometry. Data show mean ± SEM of three experiments, each in triplicate. (F) Binding of conformation-sensitive antibodies KIM127 and m24 in the absence or presence of Mn2+, PMA, cytochalasin D, or latrunculin A was measured by immunofluorescence flow cytometry. A representative of three separate experiments is shown.

In contrast to adhesion, but consistent with previous reports (Stewart et al., 1996), significant binding of soluble multimeric ICAM-1 was only observed with Mn2+ treatment (Fig. 3 E). Similarly, binding of the activation-dependent antibody KIM127, which recognizes a portion of the β2 EGF2 domain that is buried in the bent conformation and exposed in the extended conformation (Lu et al., 2001a; Beglova et al., 2002), and m24, which recognizes the active conformation of the β2 I-like domain (Lu et al., 2001b), was strongly induced by Mn2+, but not by cytochalasin D or latrunculin A (Fig. 3 F). Consistent with our previous observations (Lu et al., 2001a; Kim et al., 2003), PMA exposed the epitope for KIM127 but not m24 (Fig. 3 F), suggesting a partial ability to modulate integrin conformation.

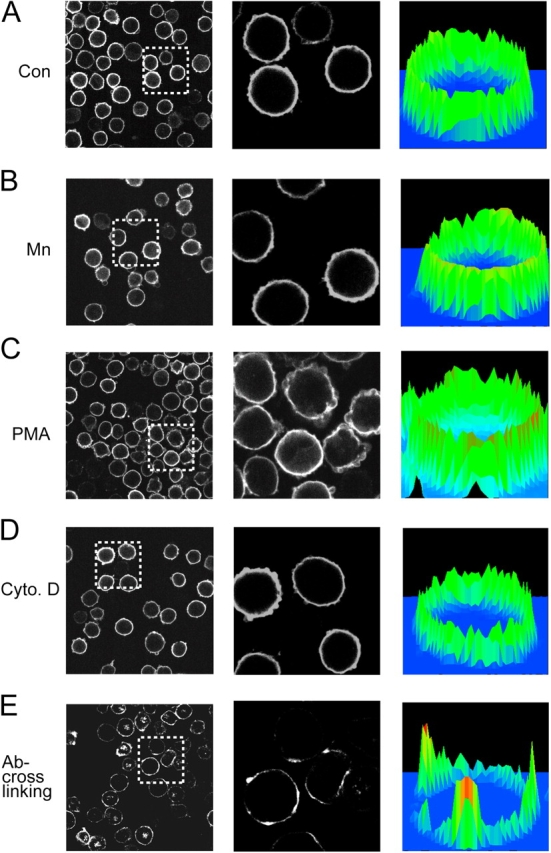

To determine whether actin-disrupting agents or PMA directly alter LFA-1 distribution patterns, we conducted confocal (Fig. 4) and FRET (Fig. 5) microscopy studies. Cross-linking cell surface LFA-1 with primary and secondary antibodies efficiently promoted LFA-1 macroclustering; however, treatment with cytochalasin D, latrunculin A, and PMA did not (Fig. 4 and unpublished data). Some alteration in the shape of PMA-treated cells was attributable to the ability of PMA to induce bleb formation in K562 cells (Osada et al., 1988), as confirmed by differential interference contrast (DIC) imaging (unpublished data). The amount of FRET between LFA-1 heterodimers in PMA- and cytochalasin D–treated cells measured either between αL subunits (Fig. 5 A) or between β2 subunits (Fig. 5 B) was similar to that in untreated cells (Fig. 1, C and F). This demonstrated an absence of significant microclustering induced by treatment with PMA or cytochalasin D. Thus, release of cytoskeletal constraints enables robust adhesion to ICAM-1 substrates, but does not drive ligand-independent integrin macro- or microclustering.

Figure 4.

Disruption of cytoskeletal constraints does not alter LFA-1 macroclustering. (A–D) K562 cells expressing wild-type αLβ2 were incubated in (A) L15 medium (control); (B) 1 mM Mn2+; (C) 1 μM PMA; or (D) 1 μM cytochalasin D for 30 min at 37°C. After fixation, cells were stained with Cy3-conjugated TS2/4 mAb. (E) Cells were incubated with Cy3-TS2/4 mAb (10 μg/ml) together with purified anti–mouse IgG (10 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min followed by fixation. All cells (A–E) were then plated on coverslips and subjected to confocal microscopy. Center panels depict a threefold magnification of the boxed regions shown in the left panels. Three-dimensional histograms of fluorescence intensity and cell surface distribution are shown in the right panels.

Figure 5.

Disruption of cytoskeletal constraints does not alter LFA-1 microclustering. Inter-heterodimer FRET between αL-mCFP/β2 and αL-mYFP/β2 (A) or αL/β2-mCFP and αL/β2-mYFP (B) was measured after 1 μM PMA or 1 μM cytochalasin D pretreatment for 30 min at 37°C, as indicated.

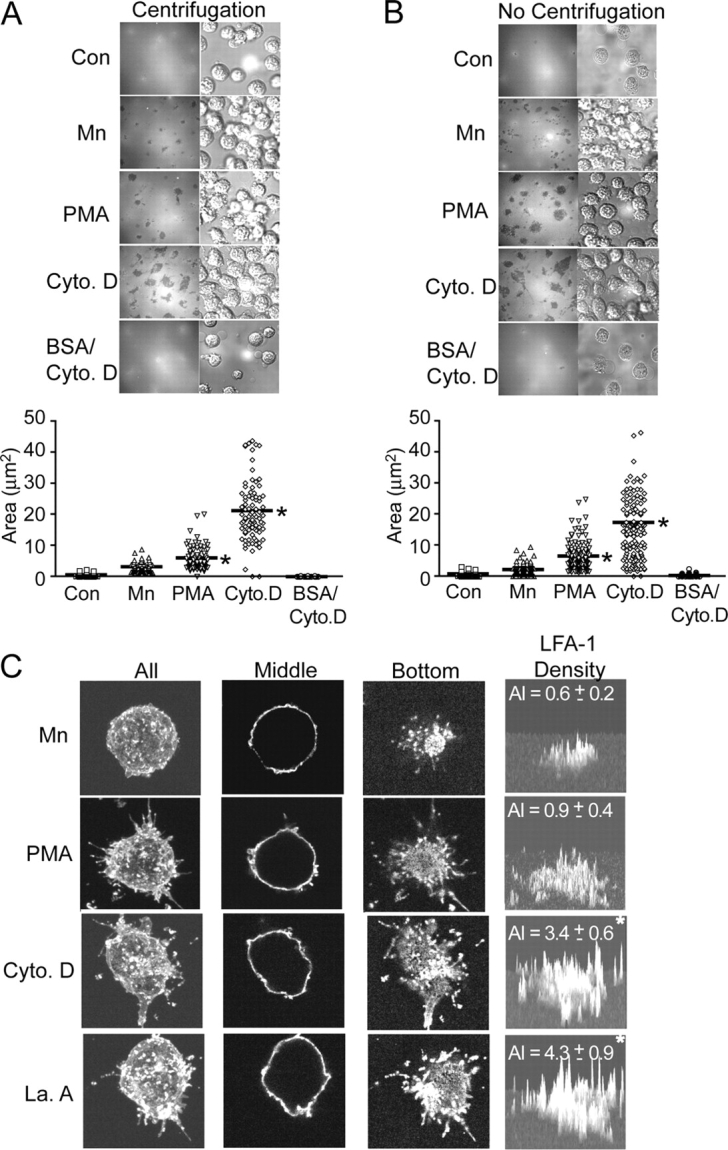

Based on these results and the finding above that binding of multivalent, soluble ICAM-1 in the presence of either Mn2+ or SDF-1 can drive microcluster formation, we hypothesized that agents that increase diffusivity regulate adhesion primarily by enhancing accumulation of LFA-1 into the zone of contact with ICAM-1 substrates. Examination of the contact zone itself by interference reflection microscopy (IRM) revealed that cytochalasin D–treated cells formed markedly larger contacts (P < 0.01) on ICAM-1 substrates than Mn2+-treated cells (Fig. 6, A and B). PMA-treated cells formed contact zones of intermediate size that were also significantly (P < 0.01) larger than those of Mn2+-treated cells. Furthermore, control cells that received no pretreatment failed to form significant contacts on ICAM-1 substrates (Fig. 6, A and B). Application of force by centrifugation did not alter the pattern of the contact zone or increase the overall contact area, suggesting that differences in contact zones were not a consequence of differential cell deformability. Fluorescence confocal microscopy revealed that the distribution of LFA-1 was not detectably different among Mn2+-, PMA-, cytochalasin D–, and latrunculin A–treated cells at planes above the cell–substrate contact interface (Fig. 6 C, middle). However, at the plane of contact, significantly (P < 0.01) greater total accumulation of LFA-1 was observed with cytochalasin D– and latrunculin A–treated cells than with Mn2+-treated cells (Fig. 6 C, bottom). Compared with Mn2+-treated cells, cytochalasin D– and latrunculin A–treated cells accumulated 5.7- and 7.2-fold more LFA-1 in the substrate contact zone, respectively, whereas PMA-treated cells exhibited a 1.5-fold increase (Fig. 6 C).

Figure 6.

Cytoskeleton disruption leads to accumulation of LFA-1 to the zone of ICAM-1 substrate contact. (A and B) Stable K562 cell transfectants expressing wild-type αLβ2 were allowed to adhere, with (A) and without (B) initial centrifugation, to coverslips coated with ICAM-1 or BSA in the absence (Control) or presence of 1 mM Mn2+, 1 μM PMA, or 1 μM cytochalasin D as indicated for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then fixed and subjected to IRM (top left panels) and DIC (top right panels). The zone including all IRM contacts for each cell was outlined and the area calculated by OpenLab software (bottom panels). Each symbol represents one cell. Bar = mean. *, P < 0.01 vs. Mn2+-treated cells. (C) Cells were prepared as in A and then were additionally subjected to staining with mAbs CBR LFA-1/7-Cy3 to β2 and TS2/4-Cy3 to αL followed by anti–mouse IgG-Cy3 to maximize the fluorescent signal. Samples were then analyzed by serial sectioning (0.5 μm Z-step) confocal microscopy. Images represent either the top view of the three-dimensional image reconstruction for “All” of the sections, or individual sections taken from the “Middle” or “Bottom” (at the ICAM-1 substrate contact interface) planes. Fluorescence intensity of LFA-1 staining in the “Bottom” section was plotted in the three-dimensional histogram of “LFA-1 density”. The LFA-1 accumulation index (AI) was calculated as (total number of pixels in the contact area × mean intensity of those pixels)/(106). AI = mean ± SEM for nine cells. *, P < 0.01 vs. Mn2+-treated cells.

The size of the contact zone and accumulation of LFA-1 (Fig. 6) were quantitated in parallel, and under exactly the same conditions, as the characterization of resistance to detachment in shear flow described in Fig. 3, C and D. Notably, Mn2+-treated cells were more resistant to shear than cytochalasin D– or latrunculin A–treated cells despite the smaller contact areas and lower amount of LFA-1 accumulation, consistent with evidence that Mn2+ increases the affinity of LFA-1 for ICAM-1.

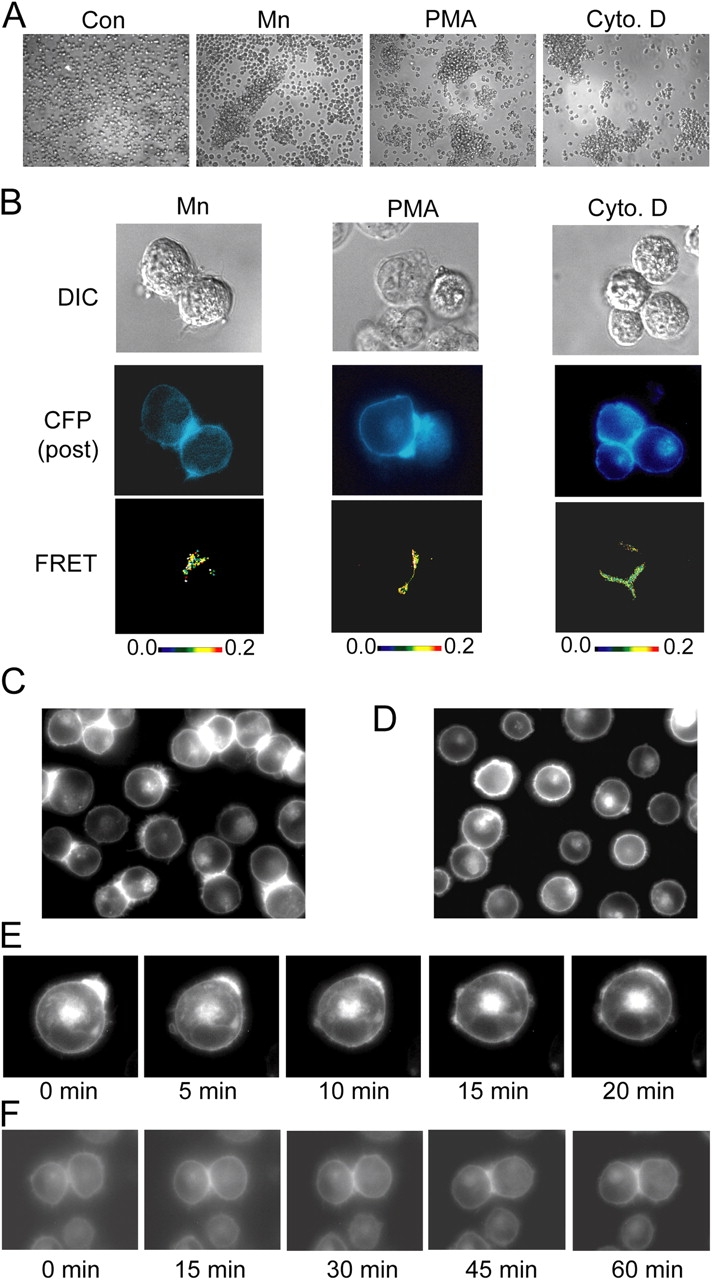

Many cell types, including K562 cells, and all leukocytes that express LFA-1 also express one or more of its ligands, the ICAMs, facilitating formation of aggregates of homotypically adherent cells (Springer, 1990; de Fougerolles and Springer, 1992). In all experiments described above, we avoided homotypic adhesion by activating cells at low density. Furthermore, cells were vigorously resuspended, allowed to settle, and incubated at 37°C for 10 min before fluorescence measurements to ensure that even if some preexisting homotypic adhesion had occurred, that the distribution of LFA-1 had equilibrated for 10 min after the cells were monodisperse. Under these conditions on ICAM-1 substrates, no homotypic adhesion occurred between neighboring K562 transfectants, as confirmed by the lack of redistribution of LFA-1 (Fig. 6 C, middle). However, when K562 transfectants were incubated at high cell densities with Mn2+, PMA, or cytochalasin D under conditions similar to those previously reported to lead to macroclustering of LFA-1, significant homotypic adhesion occurred (Fig. 7 A). Furthermore, marked macroclustering of LFA-1 was found at sites of cell–cell contact between homotypically adherent cells, whether stimulated with Mn2+, PMA, or cytochalasin D (Fig. 7 B). Moreover, LFA-1 was present in microclusters at the cell–cell contact zone, as revealed by inter-heterodimer FRET (Fig. 7 B, bottom). Notably, LFA-1 present outside the region of cell–cell contact was not microclustered.

Figure 7.

Homotypic cell aggregation promotes LFA-1 macro- and microclustering at the cell–cell contact interface. (A) K562 transfectants expressing wild-type αLβ2 in 1.5-ml microfuge tubes (106 cells in 100 μl L15 medium + 2 mg/ml glucose) were centrifuged at 200 g for 30 s and incubated in the absence (control) or presence of 1 mM Mn2+, 1 μM PMA, or 1 μM cytochalasin D for 1 h at 37°C, transferred to cell culture dishes, and imaged by phase-contrast microscopy using a 10× objective in the original experiment. (B) Transient αL-mCFP/β2 and αL-mYFP/β2 K562 transfectants were treated exactly as in A, and inter-heterodimer FRET was measured for homotypically adherent cells. DIC (top), CFP fluorescence after YFP bleaching (middle), and pixel-by-pixel FRET efficiency (from 0 [black] to 0.2 [red]) (bottom) are shown. (C and D) K562 transfectants stably expressing αL-mCFP/β2-mYFP and the talin head domain (Kim et al., 2003) were gently removed from culture flasks and either directly plated on cover glasses and imaged with YFP fluorescence (C) or micropipetted 5–10 times to obtain single suspensions, plated, and incubated for 10 min before imaging YFP fluorescence (D). (E) Aggregates of K562 transfectants expressing αL-mCFP/β2-mYFP and the talin head domain were dissociated as in D and immediately subjected to time-lapse fluorescence imaging at 37οC. (F) To observe the formation of macroclusters, cells treated as in D were allowed to reestablish homotypic cell–cell contacts during time-lapse fluorescence imaging. Images are from representative experiments. (See also Video 2 and Video 3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200404160/DC1).

The talin head domain binds to the cytoplasmic domain of the LFA-1 β2 subunit, induces conformational change in the extracellular domain of LFA-1, and increases its affinity for ICAM-1 (Kim et al., 2003). K562 cells stably transfected with LFA-1 grow as single cells, whereas additional transfection of the talin head domain (Kim et al., 2003) induced homotypic cell aggregates during growth in culture. When these cells are gently suspended, many of the cells remain homotypically adherent and show macroclustered LFA-1 at cell–cell contact interfaces (Fig. 7 C). Other suspended cells are free cells, and some of these have macroclustered LFA-1, presumably at recently disrupted sites of cell–cell contact (Fig. 7 C). The dependence of macroclustering on cell–cell contact is readily demonstrated by vigorously pipetting the cells so they are resuspended as single cells. At time 0 at 37°C, most cells show macroclustered LFA-1 (Fig. 7 E), but after 10 min of incubation at 37°C, the LFA-1 diffused into an even distribution pattern (Fig. 7, D and E; Video 2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200404160/DC1). Conversely, cells with no preformed LFA-1 macroclustering could be seen to form macroclusters within 15 min of establishing homotypic cell aggregates (Fig. 7 F and Video 3). LFA-1 in cells in the same field not involved in homotypic cell adhesions remained evenly distributed over the duration of the experiment (Fig. 7 F and Video 3). These results demonstrate that macroclusters are ligand-dependent, mass-action–driven assemblies.

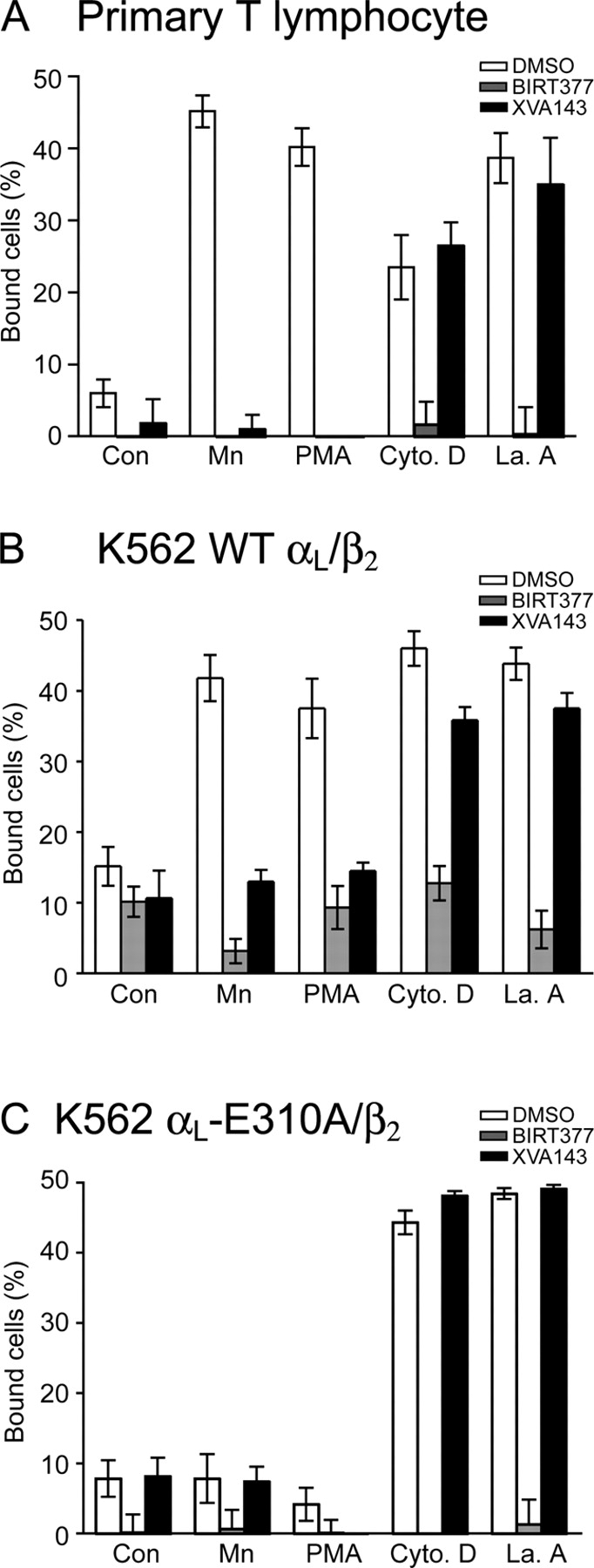

To extend our study on the relationship between integrin conformational change and valency regulation to nontransfected, primary T lymphocytes, we assessed the effects of two distinct classes of small molecule allosteric LFA-1 antagonists (Shimaoka and Springer, 2003). The α I allosteric antagonists, exemplified here with BIRT377, bind to the αL I domain and stabilize it in the low affinity, closed conformation. By contrast, the α/β I-like allosteric antagonists, exemplified here with XVA143, bind to the MIDAS of the β2 I-like domain and also in part to the αL subunit, and block the communication of conformational signals from the β2 I-like domain to the αL I domain (Shimaoka and Springer, 2003). Because of these different modes of action, we hypothesized that α I allosteric antagonists would inhibit both affinity and valency regulation of LFA-1, whereas α/β I-like allosteric antagonists would only inhibit affinity regulation. Indeed, the α I allosteric antagonist BIRT377 totally abolished adhesion to ICAM-1 induced by all agents tested (i.e., Mn2+, PMA, cytochalasin D, and latrunculin A), both with cultured primary human T lymphocytes (Fig. 8 A) and K562 transfectants expressing wild-type αLβ2 (Fig. 8 B). By contrast, XVA143 effectively blocked adhesion stimulated by Mn2+ and PMA, but did not inhibit adhesion stimulated by cytochalasin D or latrunculin A (Fig. 8, A and B). These results demonstrate that PMA- and Mn2+-stimulated adhesion (but not cytochalasin D– and latrunculin A–stimulated adhesion) requires conformational communication between the αL I- and β2 I-like domains, and that in all cases, the αL I domain must transit out of the closed, low affinity conformation to support adhesion.

Figure 8.

Affinity regulation, but not valency regulation, depends on conformational communication within the extracellular domain of LFA-1 as shown with both primary T lymphocytes and K562 transfectants. V-bottom adhesion assays were with primary human T lymphocytes (A), or with K562 cells stably expressing either wild-type αLβ2 (B) or αL-E310A/β2 (C). T lymphocytes were preincubated with 1 mM Mn2+, 1 μM PMA, 1 nM cytochalasin D, or 100 nM latrunculin A, and K562 cells were preincubated with 1 mM Mn2+, 1 μM PMA, 1 μM cytochalasin D, or 1 μM latrunculin A. Assays were in the presence of 20 μM BIRT377, 1 μM XVA143, or an equivalent concentration of DMSO as control. Data are mean ± SEM of three experiments, each in duplicate or triplicate.

αL Glu-310 communicates conformational change between the αL I- and β2 I-like domains (Yang et al., 2004). Mutation of αL Glu-310 abrogates adhesion of LFA-1 to ICAM-1 substrates stimulated by activating mAb, Mg2+/EGTA, Mn2+, and PMA (Lupher et al., 2001); the effect on adhesion stimulated by cytochalasin D and latrunculin A has not previously been examined. We confirmed that Mn2+ and PMA do not stimulate adhesion through the αL-E310A/β2 mutant (Fig. 8 C). In a remarkable contrast, cytochalasin D and latrunculin A activated adhesion through αL-E310A/β2 (Fig. 8 C) to the same extent as for wild-type αL/β2 (Fig. 8, compare C with B). Furthermore, adhesion by the mutant stimulated by cytochalasin D and latrunculin A was unaffected by XVA143, and completely inhibited by BIRT377 (Fig. 8 C). Both compounds bind to αL-E310A/β2 (Salas et al., 2004). These findings demonstrate that adhesion promoted by disruption of the actin cytoskeleton requires local conformational change in the ligand-binding αL I domain, but not conformational coupling to other integrin domains, i.e., priming (inside-out signaling) is not required.

Discussion

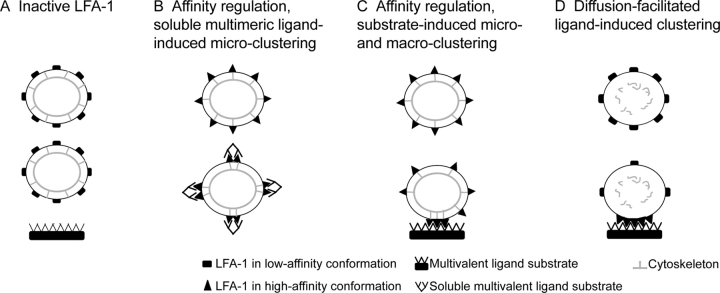

In this paper we have addressed whether LFA-1 clustering occurs independently of, or as a consequence of, ligand binding, and whether clustering can be induced by alterations in integrin conformation. Before the discovery of the structural basis (Shimaoka et al., 2003) for intermediate affinity states of LFA-1 (Lollo et al., 1993; Shimaoka et al., 2003), clustering was widely accepted as the mechanism of action for many agents such as PMA and actin microfilament disrupters that, in contrast to Mn2+, induce adhesiveness of LFA-1 but not detectable high affinity binding to ICAM-1 (Dransfield et al., 1992). Because of the perceived need to explain this disparity, it was generally accepted prima facie that clusters would be preformed. Our analysis of both macro- and microclustering demonstrate that, in the absence of either a multivalent ligand on a substrate or homotypic cell aggregation, PMA, cytochalasin D, latrunculin A, and chemokine treatments do not alter integrin distribution patterns despite their ability to promote significant adhesion (Fig. 9). These agents failed to increase FRET between neighboring αL-mCFP/β2 and αL-mYFP/β2 molecules or between neighboring αL/β2-mCFP and αL/β2-mYFP molecules. This agrees with our previous observation that stimulation with chemokines, Mn2+ plus sICAM-1, and PMA induced separation between the cytoplasmic domains of the αL and β2 subunits as shown by a decrease in FRET between αL-mCFP/β2-mYFP in individual LFA-1 heterodimers (Kim et al., 2003). Previous experiments designed to assess integrin macroclustering were often performed under conditions that promote robust homotypic cell aggregation; no effort was made to prevent homotypic adhesion, the effect of homotypic adhesion or a preincubation period in monodisperse cell suspension on cluster formation was not tested, and somtimes it was emphasized that after activation cells were fixed immediately before preparation for microscopy.

Figure 9.

Schematic of integrin affinity, diffusivity, and clustering. Inside-out signaling alters integrin affinity and cytoskeletal disruption alters integrin diffusity. How these regulate binding to ligand and the consequences for micro- and macroclustering are shown. Note that the additional effect of integrin redistribution in polarized cells was not studied here and is not shown.

The novel finding presented here that clustering of LFA-1 follows and does not precede ligand binding (Fig. 9, B–D) places the biology of β2 integrins in much better agreement with that of β1 and β3 integrins. Clustering of αIIbβ3 on activated platelets is observed in the presence (but not the absence) of fibrinogen, a multivalent ligand (Loftus and Albrecht, 1984; Isenberg et al., 1987). At concentrations that activate adhesion, PMA, cytochalasin D, and latrunculin A do not promote detectable microclustering of αIIbβ3, although these agents do enhance microclustering in response to soluble fibrinogen binding (Buensuceso et al., 2003). Furthermore, clustering of integrins αIIbβ3, αVβ3, and α5β1 into focal adhesions follows rather than precedes adhesion (Ballestrem et al., 2001; Laukaitis et al., 2001; Plancon et al., 2001).

We found that microclustering was readily induced by binding of soluble, multivalent ICAM-1 complexes (Fig. 9 B). Moreover, ICAM-1–mediated homotypic cell aggregation induced striking macro- and microclustering at the cell–cell interface (Fig. 9 C). Thus, binding to multivalent ligand drives integrin redistribution. Investigation of adhesion to ICAM-1–bearing substrates revealed that adhesion promoted by the selective disruption of cytoskeletal constraints with cytochalasin D or latrunculin A (Fig. 9 D) resulted in substantially greater accumulation of LFA-1 at the substrate contact interface than adhesion stimulated by selective enhancement of affinity with Mn2+. Thus, releasing integrins from cytoskeletal constraints facilitates not ligand-independent clustering, but ligand-dependent accumulation of integrins at the site of substrate contact, i.e., adhesion strengthening.

Based primarily on studies with peptides in detergent micelles, it was hypothesized that separation of integrin α and β subunit transmembrane domains during the global conformational shift to the open high affinity state would unmask homophilic dimerization and trimerization sites in the transmembrane segments of αIIb and β3, respectively, driving the oligomerization of integrins on the cell surface (Li et al., 2003). We have been able to directly test this hypothesis in intact cells with full-length integrins. Under conditions previously shown (Kim et al., 2003) and confirmed here to induce separation of the αL and β2 cytoplasmic domains, we found with FRET and confocal fluorescence microscopy that no macro- or microclustering occurred, as long as homotypic cell aggregation was prevented. In agreement, independent assays demonstrate that after activation in intact cells, the αIIb and β3 transmembrane domains separate, and homo-multimers of αIIb or β3 transmembrane domains are not detected (Luo et al., 2004). These results do not preclude the possibility that once ligand binding–driven microclustering takes place, homomeric interactions between transmembrane domains could stabilize adhesion assemblies.

Our results with α I- and α/β I-like allosteric antagonists demonstrate that these are excellent reagents for distinguishing between affinity and valency regulation of LFA-1 adhesiveness, and enabled us to extend our studies to untransfected T lymphocytes. The ability of the α/β I-like allosteric antagonist XVA143 to inhibit Mn2+ and PMA-stimulated adhesions demonstrates that activation by these agents requires conformational communication between the α I- and β2 I-like domains. PMA activates LFA-1 adhesiveness by virtue of its activation of PKC (Dustin and Springer, 1989), i.e., by integrin priming or inside-out signaling. By contrast, the lack of inhibition by XVA143 of cytochalasin D– and latrunculin A–stimulated adhesion demonstrates that activation by these agents does not require conformational change in response to signals from within the cell. Exactly the same pattern of inhibition by XVA143 was found with K562 transfectants and T lymphocytes, demonstrating the generality of the findings. The requirement for conformational communication between the α I- and β2 I-like domains for activation of adhesion by Mn2+ and PMA, but not cytochalasin D or latrunculin A, was confirmed with the αL-E310A mutation (Salas et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2004). The inhibition by the α I allosteric antagonist BIRT377 of adhesion stimulated by all agents demonstrates that even adhesion stimulated by cytochalasin D and latrunculin A requires conversion to the high affinity, open conformation of the αL I domain. In the case of these two agents, conformational change is driven by binding to ICAM-1 rather than inside-out signaling.

Our data demonstrating that PMA activates adhesiveness predominantly through affinity rather than valency regulation are consistent with data in previous reports, even though the conclusions have differed. PMA enhances diffusion on the cell surface of LFA-1, but whether this is the cause of its enhancement of adhesiveness of LFA-1 was not determined (Kucik et al., 1996). Indeed, the greater adhesion stimulated by PMA than cytochalasin D, the enhancement by PMA of cytochalasin D–stimulated adhesion, and the lack of enhancement by cytochalasin D of PMA-stimulated adhesion are all consistent with PMA contributing to both affinity and valency regulation (Kucik et al., 1996). Furthermore, the complete abolition of PMA-stimulated adhesion (but not cytochalasin D– or latrunculin A–stimulated adhesion) by α/β I-like allosteric antagonist and the αL-E310A mutation demonstrate a requirement for affinity regulation for PMA-stimulated adhesion. The finding here that Mn2+ induces both activation epitopes in the β2 I-like domain in the headpiece and the β2 I-EGF2 domain near the bend in β2 leg, whereas PMA induces the activation epitope in the I-EGF2 domain (Lu et al., 2001a) and not in the I-like domain, suggests that Mn2+ induces the extended, high affinity conformation of αLβ2 with an open headpiece, whereas PMA induces the extended, intermediate affinity conformation of αLβ2 with a closed headpiece (Salas et al., 2004). The higher affinity of LFA-1 on Mn2+-stimulated cells than on PMA-stimulated cells is in complete agreement with the stronger stimulation by Mn2+ than by PMA of adhesion by K562 transfectants demonstrated here, despite the lesser accumulation of LFA-1 in the adhesion zone stimulated by Mn2+ than by PMA. Our results are also consistent with the findings that PMA stimulates an increase in the monomeric affinity of LFA-1 for soluble ICAM-1 that cannot be detected in direct binding assays, but can readily be detected by displacement by soluble ICAM-1 of 125I-labeled Fab fragments to the αL I domain (Lollo et al., 1993), and that Mn2+ but not PMA stimulates an increase in affinity of LFA-1 for ICAM-1 that can be detected in direct binding assays (Stewart et al., 1996).

In the context of leukocyte firm adhesion to the vascular endothelium, it is critical to understand the mechanistic basis for the transition from rolling to arrest, as this represents the initial, integrin-dependent event in development of inflammation. Given our observation that integrin macro- and microclustering occurs only after binding to multivalent ligands, it is tempting to speculate that modulation of the conformational equilibrium plays the critical and limiting role in formation of integrin–ligand bonds that initiate firm adhesion, and that this is followed in a mass-action–dependent, diffusion-limited manner by accumulation of LFA-1 at the substrate contact interface, resulting in adhesion strengthening (Fig. 9 C). Our studies with K562 cells do not define the role of active redistribution of LFA-1 during leukocyte polarization and migration; nonetheless, differential concentration of LFA-1 to the lamellapodium in polarized cells, a form of valency regulation, may work in concert with affinity regulation (Katagiri et al., 2003). Furthermore, regulation of the diffusiveness of LFA-1 may play an important role in adhesion strengthening.

Materials and methods

Materials

PMA, cytochalasin D, and latrunculin A were from Calbiochem. Cy3-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG and goat anti–human IgA were from Zymed Laboratories. Antibody conjugation to Cy3 was according to manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Biosciences). The small molecule LFA-1 inhibitor XVA143 was from Paul Gillespie (Roche) (Shimaoka and Springer, 2003). The inhibitor BIRT377 was from Terence Kelly (Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.). Sources for anti–human αL and β2 mAbs TS2/4 and CBR-LFA1/7 have been described previously (Lu et al., 2001b). KIM127 and m24 mAbs were provided by M. Robinson (Celltech Limited) and N. Hogg (Imperial Cancer Fund, Oxford, England), respectively.

Cell culture and transfections

Culture and transient transfection of K562 cells was as described previously (Kim et al., 2003). K562 stable transfectants expressing wild-type αLβ2 were described previously (Lu et al., 2001b).

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared by Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma-Aldrich) buoyant density centrifugation of 50 ml fresh human blood. Lymphocytes were cultured at 105/ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and PHA (1 μg/ml) for 3 d, followed by culture in IL-15 (20 ng/ml) for 4–7 d. Flow cytometry demonstrated that these cells were 97% CD3 positive.

DNA plasmids and constructs

Generation of αL-mCFP and β2-mYFP was previously described (Kim et al., 2003). αL-mYFP and β2-mCFP were generated by AgeI–NotI digestion of αL-mCFP and β2-mYFP, followed by swapping and religation of the 0.7-kb mCFP and mYFP inserts, respectively.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis was as described previously (Lu et al., 2001a). R-phycoerythrin–conjugated anti–mouse IgG (BD Biosciences) was used as secondary antibody for detection.

Cell adhesion assays

V-bottom cell adhesion assay was as described previously (Kim et al., 2003). 1 mM MnCl2, 1 μM PMA, 1 μM cytochalasin D, or 1 μM latrunculin A was used for K562 cells. For human T lymphocytes, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 μM PMA, 1 nM cytochalasin D, or 100 nM latrunculin A was used. Titrations demonstrated that concentrations of 1 and 100 nM for cytochalasin D and latrunculin A, respectively, were optimal for adhesion of T lymphocytes. ICAM-1–coated plates containing equal vol of L15 medium/2.5% FCS, with identical concentrations of activating agents as in each of the cell samples, were preequilibrated to 37°C. Cells were resuspended 5–10 times with a micropipette and were added to the plates followed by immediate centrifugation at 200 g for 15 min at RT. After centrifugation, nonadherent cells that accumulated at the center of the V-bottom were quantified on a fluorescence plate reader. Flat-bottom cell adhesion assay was as described previously (Lu and Springer, 1997).

Shear detachment assay was largely as described previously (Salas et al., 2004). In brief, cells were allowed to settle onto ICAM-1–coated coverslips with or without brief centrifugation (200 g for 1 min) to enforce interaction with substrate, and then the cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min.

Binding of soluble ICAM-1

Soluble ICAM-1 binding assay was as described previously (Salas et al., 2004).

Cellular imaging

For imaging adhesion to ICAM-1 substrates, glass surfaces of ΔT4 chambers (Bioptechs) were coated with human tonsil ICAM-1 as in adhesion assays described above. K562 cells expressing wild-type αLβ2 were incubated with or without MnCl2, PMA, cytochalasin D, or latrunculin A, as above, and then allowed to contact ICAM-1 substrates either by gravity or brief centrifugation (200 g for 1 min). After a 30-min incubation at 37°C, surfaces were washed once with PBS and cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS for 10 min at RT. Cells were then stained with TS2/4 mAb to αL directly conjugated to Cy3 and washed with PBS. IRM, DIC, and FRET imaging was conducted on an epifluorescence microscope (Axiovert S200; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) at RT, using 63× oil objective coupled to an Orca CCD (Hamamatsu Corporation). Confocal imaging, consisting of serial Z-sections of 0.5-μm thickness, was performed with a laser-scanning confocal system (Radiance 2000; Bio-Rad Laboratories) coupled to a microscope (BX50BWI; Olympus) and a 100× water immersion objective. All image processing was performed with OpenLab software (Improvision).

FRET

FRET was essentially as described previously (Kim et al., 2003). 106/ml cells were washed and resuspended with 1 ml L15 medium supplemented with 2.5% FCS and incubated in 6-well plates with or without 1 mM MnCl2, 1 μM PMA, 1 μM cytochalasin D, 1 μM latrunculin A, or 100 μg/ml soluble ICAM-1 (D1-D5) at 37°C for 30 min. Then cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS for 10 min at RT. Fields, usually containing one to two transiently transfected cells, were illuminated with a 100-W mercury arc lamp through a ND 1.5 filter and a 63× oil immersion objective lens. Cells with relatively similar intensity levels of CFP and YFP were selected for experiments. After image registration and background subtraction, the CFP signal in a ring outlining the cell membrane was randomly divided into 10–15 regions of interest (ROIs) that were each analyzed independently. ROIs exhibiting saturation in either the donor or acceptor channels were eliminated from the analysis. FRET efficiency (E) was calculated as

|

(2) |

where FCFP(Pre) and FCFP(Post) are the mean CFP emission intensity before and after YFP photobleaching, respectively (Kim et al., 2003). Data were fit to  (see Results) using Prism (San Diego, CA) and Lineweaver-Burke plots, i.e., 1/E = 1/Emax + K/Emax × 1/F. K was calculated from the slope of K/Emax and 1/Emax at the y intercept. K values are given ± SD. The curves for

(see Results) using Prism (San Diego, CA) and Lineweaver-Burke plots, i.e., 1/E = 1/Emax + K/Emax × 1/F. K was calculated from the slope of K/Emax and 1/Emax at the y intercept. K values are given ± SD. The curves for  shown in the figures use the K and Emax values calculated from the Lineweaver-Burke plots.

shown in the figures use the K and Emax values calculated from the Lineweaver-Burke plots.

Calculated FRET efficiencies were plotted as a function of YFP acceptor intensity for ∼100 individual ROIs from 10–15 individual cells. Freshly prepared cells were used for each photobleach, and each dataset contained ROIs from at least three separate experiments.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows evidence for Mn2+-stimulated ligand binding and effect on LFA-1 macroclustering. Fig. S2 shows coexpression of CFP- and YFP-tagged LFA-1 and CXCR4. Fig. S3 shows that concentrations of cytochalasin D and latrunculin A that promote adhesion induce only partial disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. Fig. S4 shows that disruption of cytoskeletal constraints increases lateral mobility of LFA-1. Video 1 shows that chemokine SDF-1–activated binding of multimeric ICAM-1 does not induce detectable macroclustering of LFA-1. Video 2 shows reversal of LFA-1 clusters after disruption of homotypic cell aggregation. Video 3 shows that homotypic cell aggregation promotes LFA-1 clustering at the cell–cell contact interface. Online supplemental material available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200404160/DC1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by fellowships from the American Heart Association (C.V. Carman), by the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (A. Salas), and by grant CA31798 from the National Institutes of Health (T.A. Springer).

Abbreviations used in this paper: DIC, differential interference contrast; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; IRM, interference reflection microscopy; LFA-1, leukocyte function–associated molecule-1; ROI, region of interest.

References

- Ballestrem, C., B. Hinz, B.A. Imhof, and B. Wehrle-Haller. 2001. Marching at the front and dragging behind: differential αVβ3-integrin turnover regulates focal adhesion behavior. J. Cell Biol. 155:1319–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoni, G., and M.E. Hemler. 1998. Are changes in integrin affinity and conformation overemphasized? Trends Biochem. Sci. 23:30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beglova, N., S.C. Blacklow, J. Takagi, and T.A. Springer. 2002. Cysteine-rich module structure reveals a fulcrum for integrin rearrangement upon activation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buensuceso, C., M. De Virgilio, and S.J. Shattil. 2003. Detection of integrin αIIbβ3 clustering in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:15217–15224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman, C.V., and T.A. Springer. 2003. Integrin avidity regulation: Are changes in affinity and conformation underemphasized? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15:547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantin, G., M. Majeed, C. Giagulli, L. Piccib, J.Y. Kim, E.C. Butcher, and C. Laudanna. 2000. Chemokines trigger immediate β2 integrin affinity and mobility changes: differential regulation and roles in lymphocyte arrest under flow. Immunity. 13:759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Fougerolles, A.R., and T.A. Springer. 1992. Intercellular adhesion molecule 3, a third adhesion counter-receptor for lymphocyte function-associated molecule 1 on resting lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 175:185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dransfield, I., C. Cabañas, A. Craig, and N. Hogg. 1992. Divalent cation regulation of the function of the leukocyte integrin LFA-1. J. Cell Biol. 116:219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin, M.L., and T.A. Springer. 1989. T cell receptor cross-linking transiently stimulates adhesiveness through LFA-1. Nature. 341:619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faull, R.J., N.L. Kovach, H.M. Harlan, and M.H. Ginsberg. 1994. Stimulation of integrin-mediated adhesion of T lymphocytes and monocytes: two mechanisms with divergent biological consequences. J. Exp. Med. 179:1307–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, N., R. Henderson, B. Leitinger, A. McDowall, J. Porter, and P. Stanley. 2002. Mechanisms contributing to the activity of integrins on leukocytes. Immunol. Rev. 186:164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, W.M., R.P. McEver, D.R. Phillips, M.A. Shuman, and D.F. Bainton. 1987. The platelet fibrinogen receptor: an immunogold-surface replica study of agonist-induced ligand binding and receptor clustering. J. Cell Biol. 104:1655–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri, K., A. Maeda, M. Shimonaka, and T. Kinashi. 2003. RAPL, a novel Rap1-binding molecule, mediates Rap1-induced adhesion through spatial regulation of LFA-1. Nat. Immunol. 4:741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy, A.K., N. Petranova, and M. Edidin. 2000. High-resolution FRET microscopy of cholera toxin β-subunit and GPI-anchored proteins in cell plasma membranes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:1645–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M., C.V. Carman, and T.A. Springer. 2003. Bidirectional transmembrane signaling by cytoplasmic domain separation in integrins. Science. 301:1720–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucik, D.F., M.L. Dustin, J.M. Miller, and E.J. Brown. 1996. Adhesion-activating phorbol ester increases the mobility of leukocyte integrin LFA-1 in cultured lymphocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 97:2139–2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukaitis, C.M., D.J. Webb, K. Donais, and A.F. Horwitz. 2001. Differential dynamics of α5 integrin, paxillin, and α-actinin during formation and disassembly of adhesions in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 153:1427–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., C.R. Babu, J.D. Lear, A.J. Wand, J.S. Bennett, and W.F. Degrado. 2001. Oligomerization of the integrin αIIbβ3: Roles of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:12462–12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R., N. Mitra, H. Gratkowski, G. Vilaire, S.V. Litvinov, C. Nagasami, J.W. Weisel, J.D. Lear, W.F. DeGrado, and J.S. Bennett. 2003. Activation of integrin αIIbβ3 by modulation of transmembrane helix associations. Science. 300:795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus, J.C., and R.M. Albrecht. 1984. Redistribution of the fibrinogen receptor of human platelets after surface activation. J. Cell Biol. 99:822–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lollo, B.A., K.W.H. Chan, E.M. Hanson, V.T. Moy, and A.A. Brian. 1993. Direct evidence for two affinity states for lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 on activated T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268:21693–21700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C., and T.A. Springer. 1997. The α subunit cytoplasmic domain regulates the assembly and adhesiveness of integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1). J. Immunol. 159:268–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C., M. Ferzly, J. Takagi, and T.A. Springer. 2001. a. Epitope mapping of antibodies to the C-terminal region of the integrin β2 subunit reveals regions that become exposed upon receptor activation. J. Immunol. 166:5629–5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C., M. Shimaoka, Q. Zang, J. Takagi, and T.A. Springer. 2001. b. Locking in alternate conformations of the integrin αLβ2 I domain with disulfide bonds reveals functional relationships among integrin domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:2393–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B.H., T.A. Springer, and J. Takagi. 2004. A specific interface between integrin transmembrane helices and affinity for ligand. PLoS Biol. 2:776–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupher, M.L., Jr., E.A. Harris, C.R. Beals, L. Sui, R.C. Liddington, and D.E. Staunton. 2001. Cellular activation of leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 and its affinity are regulated at the I domain allosteric site. J. Immunol. 167:1431–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowall, A., D. Inwald, B. Leitinger, A. Jones, R. Liesner, N. Klein, and N. Hogg. 2003. A novel form of integrin dysfunction involving β1, β2, and β3 integrins. J. Clin. Invest. 111:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myou, S., X. Zhu, E. Boetticher, Y. Qin, S. Myo, A. Meliton, A. Lambertino, N.M. Munoz, K.J. Hamann, and A.R. Leff. 2002. Regulation of adhesion of AML14.3D10 cells by surface clustering of β2-integrin caused by ERK-independent activation of cPLA2. Immunology. 107:77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni, N., C.G. Kevil, D.C. Bullard, and D.F. Kucik. 2003. Avidity modulation activates adhesion under flow and requires cooperativity among adhesion receptors. Biophys. J. 85:4122–4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada, H., J. Magae, C. Watanabe, and K. Isono. 1988. Rapid screening method for inhibitors of protein kinase C. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 41:925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plancon, S., M.C. Morel-Kopp, E. Schaffner-Reckinger, P. Chen, and N. Kieffer. 2001. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagged to the cytoplasmic tail of αIIb or β3 allows the expression of a fully functional integrin αIIbβ3: effect of β3GFP on αIIbβ3 ligand binding. Biochem. J. 357:529–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas, A., M. Shimaoka, A.N. Kogan, C. Harwood, U.H. von Andrian, and T.A. Springer. 2004. Rolling adhesion through an extended conformation of integrin αLβ2 and relation to α I and β I-like domain interaction. Immunity. 20:393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimaoka, M., and T.A. Springer. 2003. Therapeutic antagonists and conformational regulation of integrin function. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2:703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimaoka, M., T. Xiao, J.H. Liu, Y. Yang, Y. Dong, C.D. Jun, A. McCormack, R. Zhang, A. Joachimiak, J. Takagi, et al. 2003. Structures of the αL I domain and its complex with ICAM-1 reveal a shape-shifting pathway for integrin regulation. Cell. 112:99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer, T.A. 1990. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 346:425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M.P., C. Cabanas, and N. Hogg. 1996. T cell adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is controlled by cell spreading and the activation of integrin LFA-1. J. Immunol. 156:1810–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M.P., A. McDowall, and N. Hogg. 1998. LFA-1-mediated adhesion is regulated by cytoskeletal restraint and by a Ca2+-dependent protease, calpain. J. Cell Biol. 140:699–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, J., B.M. Petre, T. Walz, and T.A. Springer. 2002. Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell. 110:599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooyk, Y., and C.G. Figdor. 2000. Avidity regulation of integrins: the driving force in leukocyte adhesion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooyk, Y., P. Weder, K. Heije, and C.G. Figdor. 1994. Extracellular Ca2+ modulates LFA-1 cell surface distribution on T lymphocytes and consequently affects cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 124:1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooyk, Y., S.J. van Vliet, and C.G. Figdor. 1999. The actin cytoskeleton regulates LFA-1 ligand binding through avidity rather than affinity changes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26869–26877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, O., A. Velyvis, A. Velyviene, B. Hu, T.A. Haas, E.F. Plow, and J. Qin. 2002. A structural mechanism of integrin αIIbβ3 “inside-out” activation as regulated by its cytoplasmic face. Cell. 110:587–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T., J. Takagi, B.S. Coller, J.H. Wang, and T.A. Springer. 2004. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 432:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W., M. Shimaoka, A. Salas, J. Takagi, and T.A. Springer. 2004. Inter-subunit signal transmission in integrins by a receptor-like interaction with a pull spring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:2906–2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias, D.A., J.D. Violin, A.C. Newton, and R.Y. Tsien. 2002. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science. 296:913–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X., and J. Li. 2000. Macrophage-enriched myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate and its phosphorylation is required for the phorbol ester-stimulated diffusion of β2 integrin molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20217–20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X., J. Li, and D.F. Kucik. 2001. The microtubule cytoskeleton participates in control of β2 integrin avidity. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44762–44769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]