Abstract

Receptor-regulated class I phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K) phosphorylate the membrane lipid phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns)-4,5-P2 to PtdIns-3,4,5-P3. This, in turn, recruits and activates cytosolic effectors with PtdIns-3,4,5-P3–binding pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, thereby controlling important cellular functions such as proliferation, survival, or chemotaxis. The class IB p110γ/p101 PI3Kγ is activated by Gβγ on stimulation of G protein–coupled receptors. It is currently unknown whether in living cells Gβγ acts as a membrane anchor or an allosteric activator of PI3Kγ, and which role its noncatalytic p101 subunit plays in its activation by Gβγ. Using GFP-tagged PI3Kγ subunits expressed in HEK cells, we show that Gβγ recruits the enzyme from the cytosol to the membrane by interaction with its p101 subunit. Accordingly, p101 was found to be required for G protein–mediated activation of PI3Kγ in living cells, as assessed by use of GFP-tagged PtdIns-3,4,5-P3–binding PH domains. Furthermore, membrane-targeted p110γ displayed basal enzymatic activity, but was further stimulated by Gβγ, even in the absence of p101. Therefore, we conclude that in vivo, Gβγ activates PI3Kγ by a mechanism assigning specific roles for both PI3Kγ subunits, i.e., membrane recruitment is mediated via the noncatalytic p101 subunit, and direct stimulation of Gβγ with p110γ contributes to activation of PI3Kγ.

Keywords: G protein; fluorescence imaging; phosphoinositide 3-kinase; FRET; PH domain

Introduction

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks)* phosphorylate the D3 position of the inositol ring of phosphoinositides, thereby generating intracellular signaling molecules (Stephens et al., 1993; Fruman et al., 1998). These phospholipids, i.e., phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns)-3-P, PtdIns-3,4-P2, and PtdIns-3,4,5-P3, have been implicated in cellular functions including chemotaxis, differentiation, glucose homeostasis, proliferation, survival, and trafficking (Vanhaesebroeck et al., 2001; Cantley, 2002). They transmit signals by recruiting effector molecules that possess specific lipid-binding domains. FYVE domains and PX domains bind to PtdIns-3-P with high affinity, whereas a subgroup of pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, containing a highly basic motif, preferentially binds PtdIns-3,4-P2 and PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 (Hurley and Misra, 2000; Simonsen et al., 2001; Wishart et al., 2001).

PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 represents the major product of class I PI3Ks in vivo. These lipid kinases are under tight control of cell surface receptors, including receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) or G protein–coupled receptors (GPCR; Katso et al., 2001). All class I members are heterodimers consisting of a p110 catalytic and a p85- or p101-type noncatalytic subunit. The class IA p110 isoforms α, β, and δ form a complex with p85 adaptor subunits, whereas the only class IB member (p110γ) is associated with a p101 noncatalytic subunit. The p85 subunit binds to tyrosine-phosphorylated RTKs. This interaction has two consequences resulting in activation of the PI3K. First, the cytosolic enzyme translocates to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, giving p110 access to its lipid substrate (Gillham et al., 1999). Second, the interaction with the tyrosine-phosphorylated receptor induces a conformational change of p85 that results in disinhibition of p110 enzymatic activity (Yu et al., 1998). Because the p85 regulatory subunit inhibits the p110 catalytic subunit, it is feasible that constitutively membrane-associated class IA p110 mutants trigger downstream responses characteristic of growth factor action (Klippel et al., 1996).

Similar to class IA PI3Ks, unstimulated PI3Kγ is predominantly localized in the cytosol, whereas GPCRs induced an increase of PI3Kγ in the membrane fraction (Al-Aoukaty et al., 1999; Naccache et al., 2000). GPCRs activate PI3Kγ through direct interaction with Gβγ, whereas a stimulation by Gα is quantitatively less important (Stoyanov et al., 1995; Stephens et al., 1997; Leopoldt et al., 1998). However, little is known about the activating mechanism, e.g., it remains elusive whether Gβγ functions as a membrane anchor or an allosteric regulator of PI3Kγ. Although the p101 subunit has been proposed to act as an indispensable adaptor linking Gβγ with p110γ (Stephens et al., 1997), in vitro studies have suggested that p101 is not mandatory for Gβγ-induced stimulation of PI3Kγ (Stoyanov et al., 1995). Moreover, a direct interaction of Gβγ with NH2- and COOH-terminal regions of p110γ has been demonstrated (Leopoldt et al., 1998). Further support for a direct interaction of Gβγ with the p110 catalytic subunit came from the observation that the p110β isoform can also be stimulated by Gβγ, regardless of whether p85 is present or not (Kurosu et al., 1997; Maier et al., 1999, 2000). Nevertheless, the noncatalytic p101 subunit of PI3Kγ binds tightly to Gβγ, suggesting specific roles in G protein–induced regulation of this lipid kinase. For instance, in vitro studies showed that Gβγ-stimulated p110γ potently produced PtdIns-3-P, whereas the Gβγ-activated heterodimeric p110γ/p101 counterpart potently catalyzed the formation of PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 (Maier et al., 1999). This suggests that p101 may affect the interaction of Gβγ-stimulated p110γ with the lipid interface.

Therefore, the exact roles of Gβγ and PI3Kγ subunits in G protein–induced activation of PI3Kγ in living cells remain unclear. Hence, we asked whether Gβγ functions as a membrane anchor and/or allosteric activator, and whether p101 is required for proper function of p110γ in vivo. To tackle these questions, we examined cellular events leading to activation of PI3Kγ using fluorescent fusion proteins in living cells.

Results

Characterization of fluorescent PI3K fusion proteins

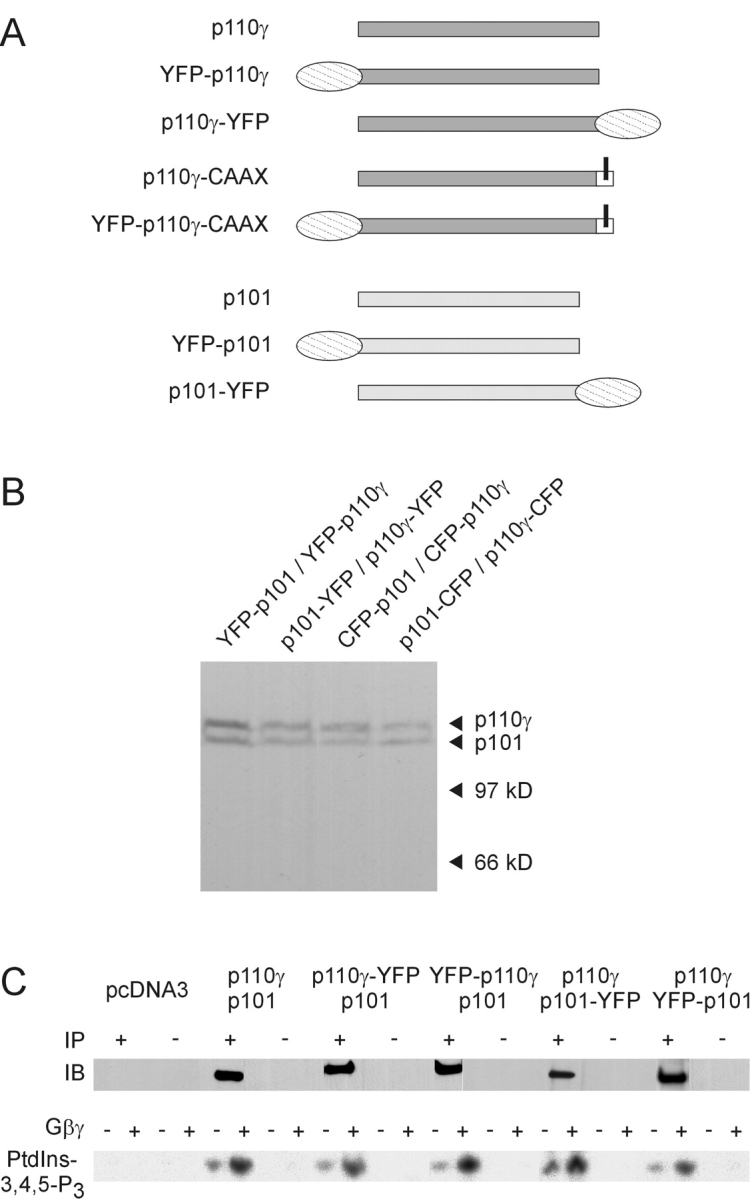

To visualize PI3Kγ subunits in vivo, we generated constructs encoding p110γ and p101 fused to YFP or CFP (Fig. 1 A). Their expression in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells was verified by immunoblot analysis using an antibody against GFP (Fig. 1 B). The catalytic activity and Gβγ sensitivity of PI3Kγ fusion proteins was confirmed by in vitro lipid kinase assays after immunoprecipitation with an mAb recognizing only intact p110γ (Fig. 1 C). Precipitates from vector-transfected control cells neither exhibited p110γ immunoreactivity nor lipid kinase activity. These results demonstrate that YFP-fused p110γ or p101 retain essential functions of the wild-type PI3Kγ.

Figure 1.

Construction and characterization of fluorescent PI3Kγ fusion proteins. (A) Schematic representation of the wild-type, fluorescent, and membrane-targeted PI3Kγ subunits. A YFP (or CFP) tag was fused to either the NH2- or the COOH terminus of p110γ and p101. The p110γ-CAAX fusion protein contains an isoprenylation motif (bars for lipid modifications). (B) Differently fluorescence-tagged PI3Kγ subunits were coexpressed in HEK cells, and cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with a GFP-specific antibody. (C) Catalytic activity of fluorescent PI3Kγ fusion proteins. HEK cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with (+) or without (−) an anti-p110γ antibody. immunoprecipitation was controlled by immunoblotting (IB) with another anti-p110γ antibody. Shown are chemiluminescence images (top panels). Immunoprecipitates were assayed for in vitro PI3K activity in the absence or presence of 120 nM Gβγ using PtdIns-4,5-P2– containing lipid vesicles and γ[32P]ATP as substrates. Depicted are autoradiographs of the generated 32P-PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 (bottom panels).

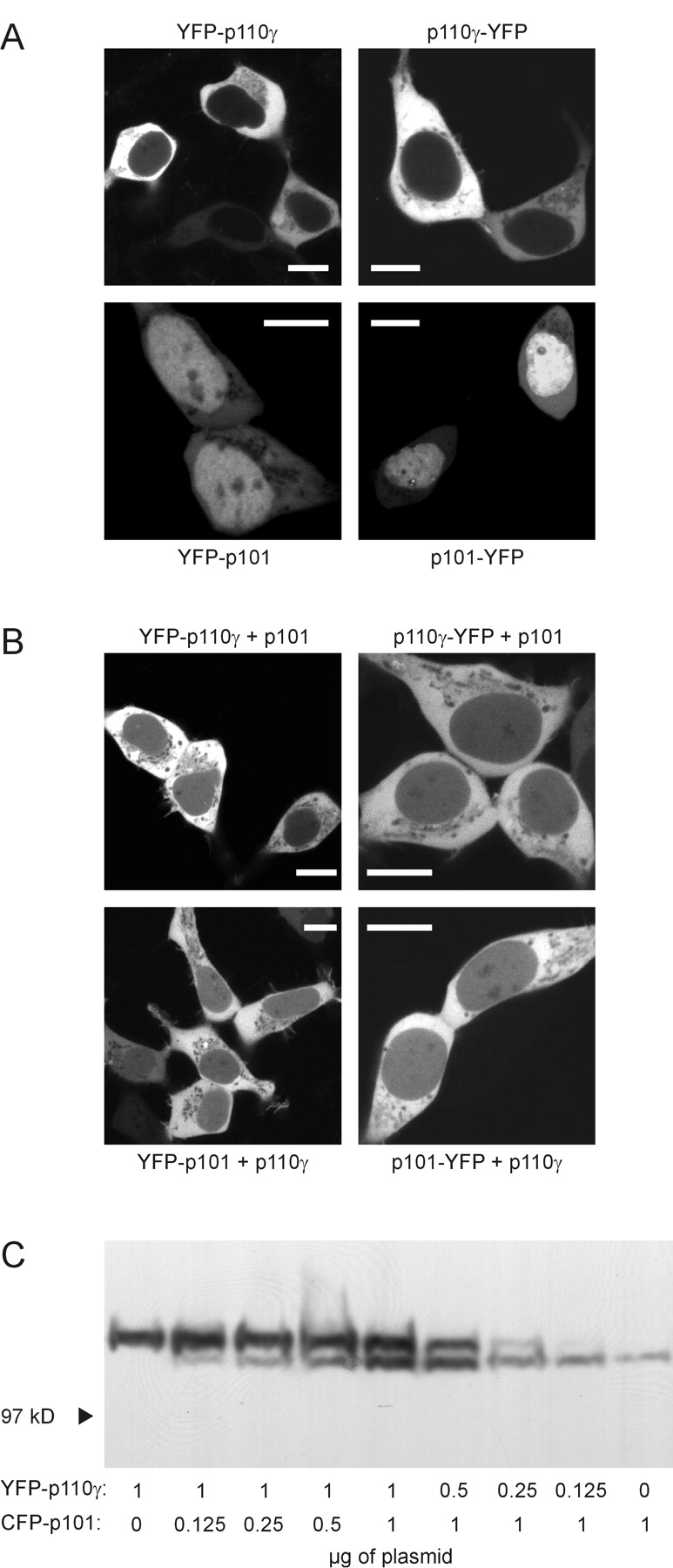

Subcellular distribution of PI3Kγ subunits and instability of monomeric p101

Next, we examined the subcellular distribution of the YFP-tagged PI3Kγ subunits in living cells by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Although YFP was uniformly distributed inside HEK cells (unpublished data), fluorescence signals from YFP fused to the NH2 or COOH termini of p110γ were only detected in the cytosolic compartment (Fig. 2 A, top). However, a small fraction of the YFP-fused p110γ was also detected in the nucleus when coexpressed with wild-type p101 (Fig. 2 B, top). The same distribution was seen for YFP-tagged p101 coexpressed with wild-type p110γ (Fig. 2 B, bottom). Thus, fluorescent PI3Kγ subunits form heterodimers (see next section), present in the cytosol and nucleus of HEK cells, whereas distribution of the p110γ subunit alone seems restricted to the cytosol. Interestingly, YFP-fused p101 alone showed a predominant nuclear localization with a significantly lower overall fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2 A, bottom).

Figure 2.

Expression and subcellular distribution of fluorescent p110γ and p101 in HEK cells. (A) Cells were transfected with plasmids for YFP-tagged single PI3Kγ subunits as indicated. Images were taken by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Images of typical cells are shown. White bars indicate a 10-μm scale. (B) Cells were cotransfected with both p110γ and p101. Only one subunit was fused to YFP as indicated. (C) Cells were transfected with plasmids encoding fluorescent p110γ and p101 at different ratios. The total amount of transfected cDNA was kept constant by the addition of pcDNA3. Equal amounts of whole-cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with an anti-GFP antibody.

To explore the possibility that expression levels of p101 could depend on the coexpression of p110γ, we transfected HEK cells with different ratios of plasmids encoding fluorescent p110γ or p101 and analyzed total cell lysates by immunoblotting using an anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 2 C). The expression level of p110γ correlated with the amount of the p110γ (but not the p101) plasmid. In contrast, the expression level of p101 was also dependent on the amount of the p110γ plasmid. Hence, the stability of p101 depends on the coexpression of p110γ, but not vice versa. The poor cytosolic fluorescence of YFP-tagged p101 in the absence of p110γ may thus be explained by cytosolic degradation of monomeric p101.

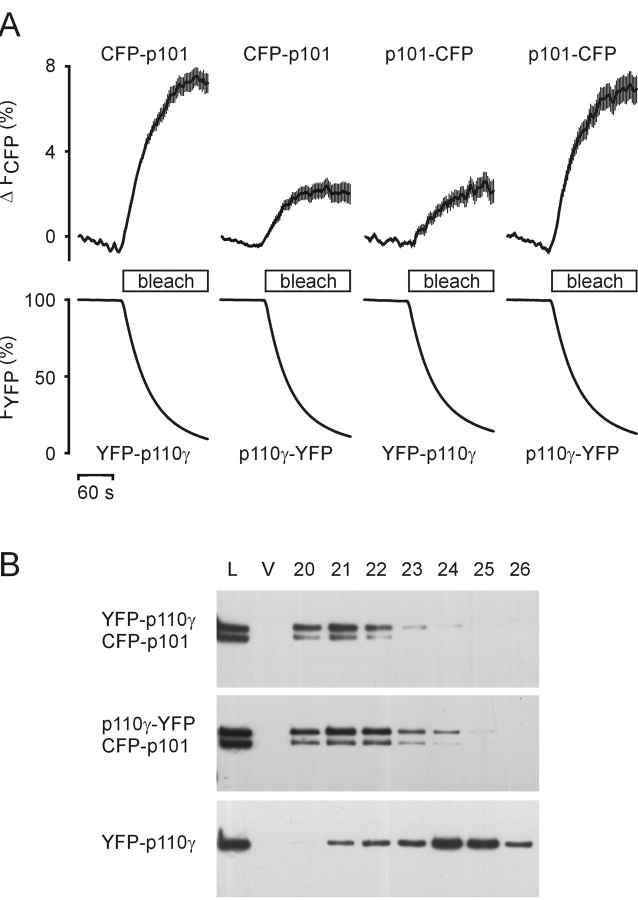

In vivo dimerization of PI3Kγ subunits

To directly demonstrate heterodimerization of PI3Kγ subunits in living cells, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). FRET between two fluorophores, e.g., CFP and YFP, is restricted to distances of <100 Å, and therefore, provides direct evidence for a protein–protein interaction (Teruel and Meyer, 2000). We coexpressed CFP- and YFP-tagged PI3Kγ subunits and determined FRET by following the donor (CFP) recovery during acceptor (YFP) bleach (Fig. 3 A). All combinations showed significant FRET, although quantitative differences were evident.

Figure 3.

Dimerization of p110γ and p101. (A) HEK cells were cotransfected with plasmids encoding NH2- or COOH-terminally YFP-tagged p110γ and NH2- or COOH-terminally CFP-tagged p101 in different combinations. FRET was measured in vivo. An increase in CFP (donor) fluorescence during YFP (acceptor) bleach indicates FRET between fluorescent PI3Kγ subunits. The depicted data represent means ± SEM of at least 18 single cells in three independent transfection experiments. (B) HEK cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Cytosols were prepared and subjected to gel filtration. The elution profiles were analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-GFP antibody (L, load diluted 1:5; V, void volume; 20–26, fraction numbers).

Because FRET efficiency is a function of the distance between two fluorophores, quantitative differences may represent different distances of the fluorescent tags fused to the NH2 or COOH termini of p101 and p110γ in a particular combination. However, the different FRET efficiencies may also reflect different degrees of heterodimerization. To exclude the latter, we analyzed heterodimerization of different p101/p110γ combinations by size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 3 B). The elution profile of YFP-p110γ (Fig. 3 B, bottom) was completely shifted to earlier fractions on coexpression with CFP-p101 (Fig. 3 B, top), indicating a high degree of heterodimerization. A similar elution profile was found for p110γ-YFP + CFP-p101 (Fig. 3 B, middle), albeit a lower FRET efficiency was detected for this combination. Hence, the different FRET efficiencies observed are not due to different degrees of dimerization, but likely reflect different distances of the fluorescent tags in the p101/p110γ heterodimer. Thus, their two NH2 termini as well as their two COOH termini are in close proximity, whereas the NH2 terminus of each subunit is relatively far from the COOH terminus of the other.

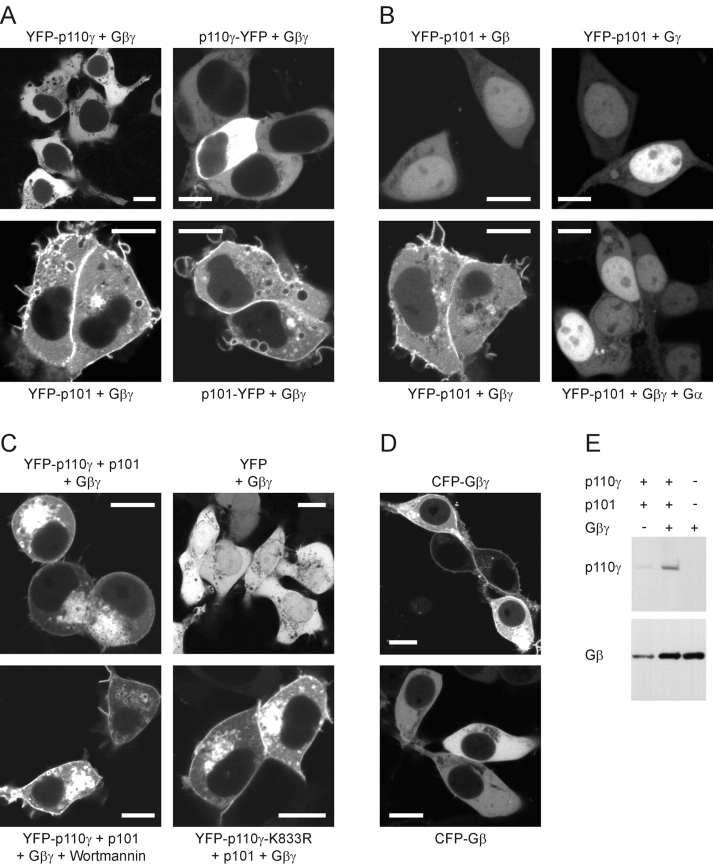

Gβγ dimers recruit PI3Kγ to membranes via the p101 subunit

Current concepts of PI3K activation are based on the recruitment of the cytosolic lipid kinase to the plasma membrane (Klippel et al., 1996). In the case of PI3Kγ, the major stimulus is assumed to be Gβγ, which is membrane-bound and has been shown to directly bind to both kinase subunits under in vitro conditions (Stephens et al., 1997; Maier et al., 1999). Therefore, we asked whether overexpression of free Gβγ directs YFP-fused PI3Kγ subunits to the cell membrane in vivo. Surprisingly, p110γ was not membrane-localized in the presence of coexpressed Gβγ in HEK cells (Fig. 4 A, top). In contrast, Gβγ recruited p101 to the membrane, resulting in accumulation of NH2- or COOH-terminally YFP-tagged p101 at both plasma- and endomembranes (Fig. 4 A, bottom, and Fig. 4 B). This corresponds to the subcellular distribution of overexpressed Gβγ dimers (see below), suggesting that p101 interacted with membrane-bound Gβγ.

Figure 4.

Membrane recruitment of PI3Kγ by Gβγ. The effect of coexpression of Gβγ on the subcellular distribution of p110γ, p101, and heterodimeric PI3Kγ in HEK cells was analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Images of typical cells are shown (white bars, 10 μm). (A) Coexpression of monomeric PI3Kγ subunits with Gβγ. (B) Controls; coexpression of YFP-p101 with Gβ1, Gγ2, Gβ1γ2, or Gβ1γ2 and the Gβγ- scavenging Gαi2. (C) Coexpression of heterodimeric PI3Kγ with Gβγ. Note the round shape of the cells. Controls; coexpression of Gβγ with YFP or with kinase-deficient YFP-p110γ-K833R and p101; effect of 100 nM wortmannin. (D) Subcellular localization of Gβγ. Cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding CFP-tagged Gβ1 alone or together with the Gγ2 plasmid. (E) Immunoblot analysis of membrane fractions. HEK cells were transfected with the plasmids encoding PI3Kγ, Gβγ, or both together. To avoid rounding and detachment of the cells, the kinase-deficient mutant YFP-p110γ-K833R was used. Membrane fractions were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p110γ and anti-Gβ antibodies.

Next, we examined the subcellular localization of p110γ/p101 heterodimers in the presence of free Gβγ. When coexpressed with p101 and Gβγ, the p110γ fluorescent signal was at, or close to, plasma and endosomal membranes of HEK cells (Fig. 4 C, top). The same picture emerged when the YFP-tag was fused to p101 (unpublished data). Correspondingly, CFP-tagged Gβ1 coexpressed with Gγ2 exhibited a similar subcellular distribution like fluorescent heterodimeric PI3Kγ (compare Figs. 4 C and 4 D), and immunoblotting of membrane-derived proteins confirmed an enrichment of PI3Kγ in the membrane compartment after overexpression of Gβγ (Fig. 4 E). Together, these data imply that Gβγ directs cytosolic PI3Kγ to the membrane via interaction with p101.

Interestingly, coexpression of heterodimeric PI3Kγ together with Gβγ produced a rounded morphology and detachment of the cells (Fig. 4 C). This morphological change was reversed by treatment with 100 nM of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin in approximately half of the cells within 30 min, and not seen when a kinase-deficient YFP-p110γ-K833R mutant was used (Fig. 4 C). Hence, the morphological change was related to the enzymatic activity of PI3Kγ stimulated by the coexpressed Gβγ.

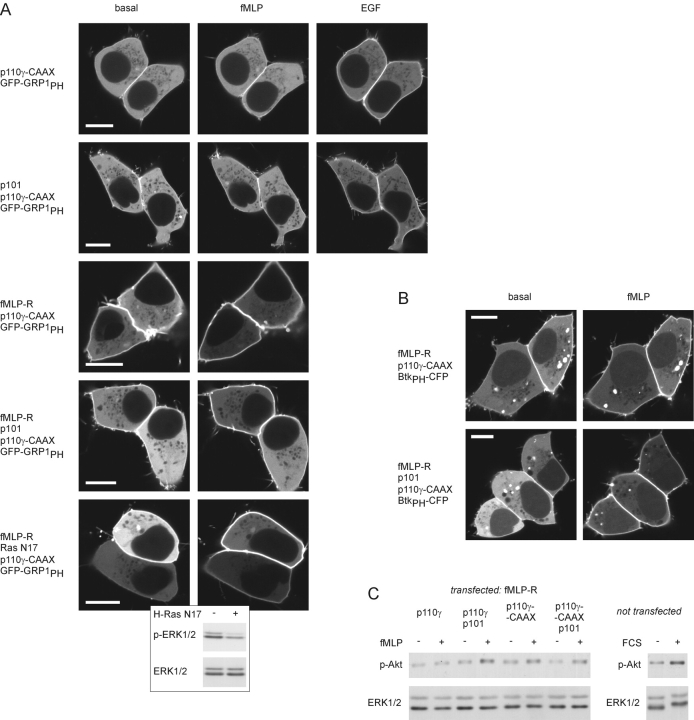

p101 is required for G protein–mediated activation of p110γ in vivo

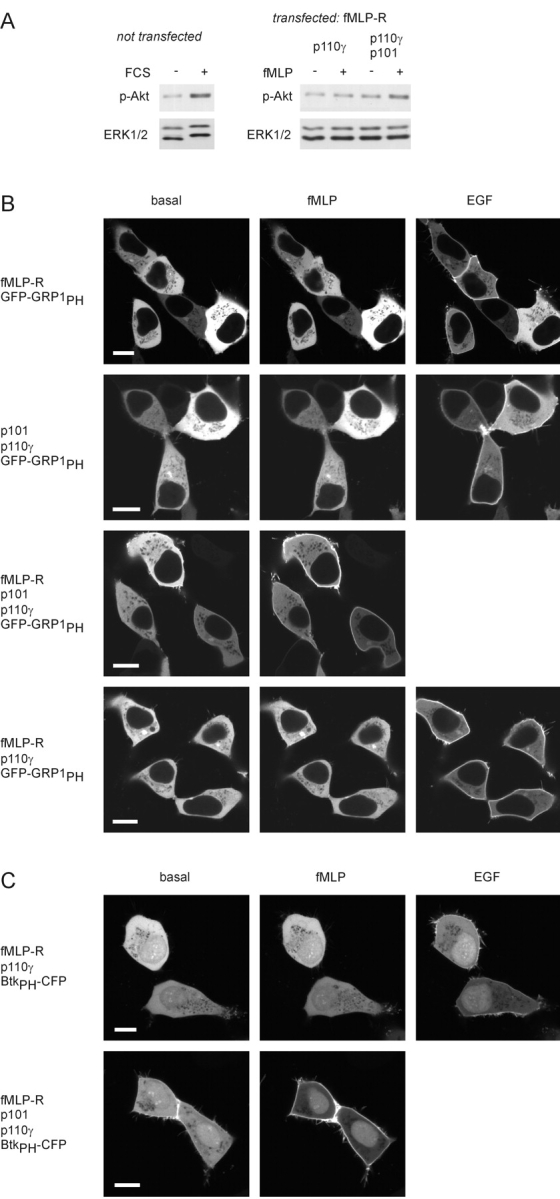

Because changes in morphology are not a very reliable measure of PI3K activity, we examined phosphorylation of endogenous protein kinase B (PKB or Akt) as an established PI3K-specific read-out system. To avoid detachment of the cells as a consequence of constitutive PI3Kγ stimulation by overexpressed Gβγ, we transiently stimulated the heterologously expressed Gi-coupled formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) receptor, which is known to activate PI3Kγ (Stephens et al., 1993). Stimulation with fMLP induced Akt phosphorylation in HEK cells in the same range as with FCS (Fig. 5 A). However, Akt phosphorylation was only seen when the receptor was coexpressed with both PI3Kγ subunits, and not with p110γ alone. These data imply that p101 is required for GPCR-induced activation of PI3Kγ in vivo.

Figure 5.

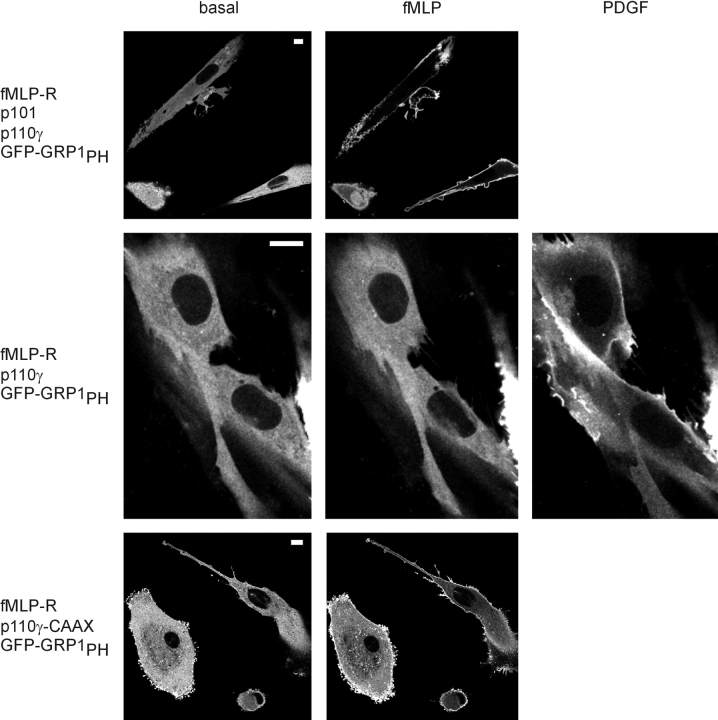

Activation of PI3Kγ by a G protein–coupled receptor. (A) Akt phosphorylation. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using an antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylated form of Akt. Equal loading was shown by using an anti-ERK antibody. Left; FCS-induced Akt phosphorylation in untransfected HEK cells. Right; fMLP-induced Akt phosphorylation in cells expressing the fMLP receptor and only the catalytic (p110γ) or both PI3Kγ subunits. (B) Membrane recruitment of the PtdIns-3,4,5-P3–binding PH domain of GRP1. HEK 293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the PH domain of GRP1 fused to GFP (GFP-GRP1PH), and the human fMLP receptor (fMLP-R), p110γ, and p101 in different combinations. The localization of the GFP-GRP1PH was monitored before and after the addition of 1 μM fMLP and 100 ng/ml EGF (added 8 min later) by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Pictures were taken 4 min after addition of either agonist. Images of typical experiments are shown (white bars, 10 μm). (C) Membrane recruitment of the PtdIns-3,4,5-P3–binding PH domain of Btk. Instead of GFP-GRP1PH, the PH domain of Btk fused to CFP (BtkPH-CFP) was used as a PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 sensor.

To measure PI3Kγ activity by a complementary experimental approach, the effects of fMLP receptor stimulation on the subcellular distribution of GFP-GRP1PH fusion proteins were examined. Recruitment of the GFP-labeled PH domain of general receptor for phosphoinositides-1 (GRP1), a PI3K-activated exchange factor for ADP-ribosylation factors (Lietzke et al., 2000), has been applied to detect formation of PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 with high affinity and selectivity (Gray et al., 1999; Balla et al., 2000). fMLP stimulation had no effect on the subcellular distribution of GFP-GRP1PH in HEK cells expressing either the receptor or PI3Kγ alone (Fig. 5 B, top two panels), whereas subsequent stimulation with EGF induced a rapid membrane recruitment of the PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 sensor, presumably through activation of an endogenously expressed RTK-sensitive class IA PI3K. In cells coexpressing the fMLP receptor and heterodimeric PI3Kγ, fMLP stimulation induced a rapid membrane translocation of GFP-GRP1PH (Fig. 5 B, third panel), indicating that this effect indeed reflects fMLP receptor–mediated stimulation of PI3Kγ. Accordingly, the fMLP-induced effect was sensitive to pretreatment with pertussis toxin (PTX; unpublished data). Interestingly, a slight basal membrane localization of GFP-GRP1PH was visible in the cells coexpressing heterodimeric PI3Kγ and the fMLP receptor even in the absence of agonist (Fig. 5 B, third panel). Because this was not seen after PTX treatment (unpublished data) or in cells omitting the receptor (Fig. 5 B, second panel), it most likely reflected a constitutively active fMLP receptor.

Translocation of an isolated PH domain in single cells may be a more sensitive read-out for PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 production than the Akt phosphorylation assay. Hence, we used the GFP-GRP1PH translocation approach to reexamine the requirement of p101 for receptor-induced PI3Kγ activation (Fig. 5 A). Nevertheless, an fMLP-induced membrane recruitment of GFP-GRP1PH in cells coexpressing the receptor and p110γ (but not p101) was not visible (Fig. 5 B, fourth panel). This finding confirms that the noncatalytic p101 subunit is required for GPCR-mediated stimulation of PI3Kγ in living cells.

To further strengthen the findings, we replaced GFP-GRP1PH by the GFP-fused PH domain of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BtkPH), which has also been described to bind PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 with high specificity and affinity (Várnai et al., 1999). As expected, fluorescent BtkPH was distributed equally between cytosol and nucleus in HEK cells (Fig. 5 C). However, cells coexpressing the receptor and both PI3Kγ subunits exhibited a slight basal membrane localization of BtkPH-CFP followed by a prominent translocation from the cytosol to the membrane on exposure to fMLP. Similar to GFP-GRP1PH, no fMLP-induced redistribution of BtkPH-CFP was seen in the absence of p101.

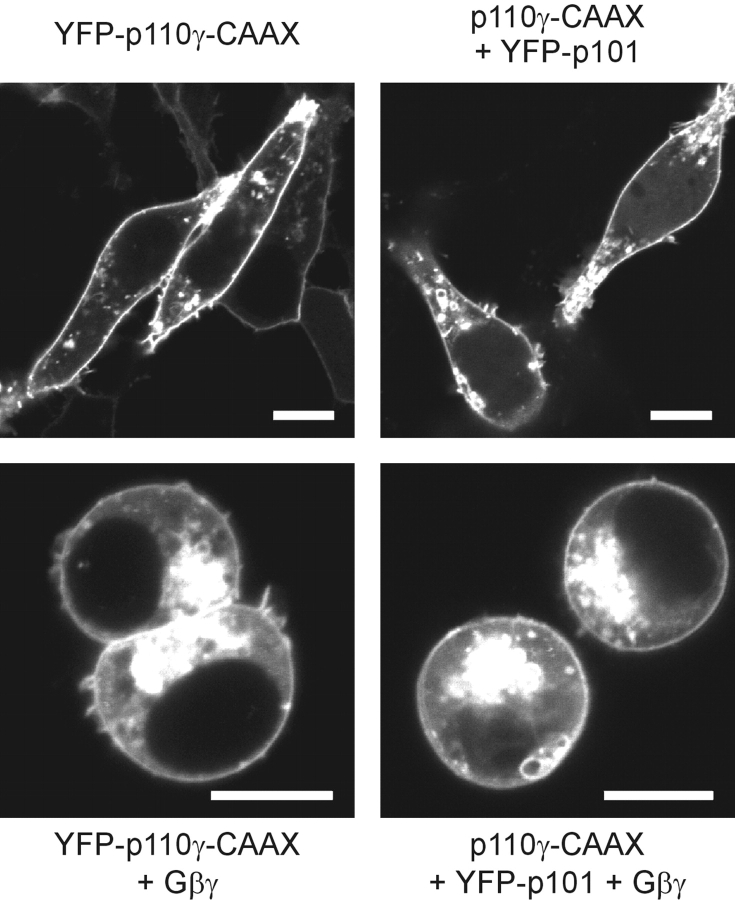

Activation of a membrane-targeted p110γ-CAAX in vivo

The presented data suggest that in living cells, p101 is an indispensable adaptor for GPCR-induced translocation and activation of class IB PI3Kγ, which is equivalent to the role of p85 in RTK-induced class IA PI3K activation. Vice versa, Gβγ behaves as a membrane anchor recruiting PI3Kγ through association with p101. So far, these experiments did not clarify whether membrane recruitment itself is sufficient for activation of the enzyme or whether additional allosteric stimulation is required. To tackle this question, we generated p110γ mutants containing a COOH-terminal isoprenylation signal, i.e., a CAAX-box motif, which constitutively localizes p110γ to the plasma membrane. p110γ-CAAX accumulated at the plasma membrane of HEK cells, and was able to complex with p101 (Fig. 6, top). Coexpression of Gβγ together with YFP-p110γ-CAAX increased not only fluorescent staining of endomembranes, but also produced a wortmannin-sensitive rounding of the cells (Fig. 6, bottom) even in the absence of p101 (not depicted), which was similar to the effect after coexpression of Gβγ with p110γ/p101 dimers (see Fig. 4 C). These observations imply that membrane-bound PI3Kγ is not fully active, but can be further activated by Gβγ.

Figure 6.

Characterization of a constitutively membrane-associated p110γ-CAAX. HEK cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Images of typical cells are shown. White bars indicate a 10-μm scale. Top panel; Subcellular localization of YFP-p110γ-CAAX (left) or YFP-p101 expressed together with p110γ-CAAX (right). Bottom panel; Coexpression with Gβγ.

To substantiate this assumption, we analyzed the subcellular redistribution of GFP-GRP1PH in HEK cells coexpressing membrane-targeted p110γ-CAAX, p101 and the fMLP receptor in various combinations (Fig. 7 A). A slight basal membrane localization of the fluorescent PH domain was evident on coexpression with p110γ-CAAX (Fig. 7 A, top panel) indicating an elevated PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 level. The same picture emerged when p101 was present in the panel of transfected plasmids (Fig. 7 A, second panel). On coexpression of the receptor, fMLP induced a significant additional translocation of GFP-GRP1PH from the cytosol to the membrane (Fig. 7 A, third and fourth panel) indicating additional stimulation of the membrane-bound lipid kinase. Interestingly, the effect was similar irrespective of whether p101 was present or not, suggesting direct activation of monomeric p110γ. PTX sensitivity confirmed that fMLP-induced activation of p110γ-CAAX was mediated by Gi proteins (unpublished data). Because Gβγ can activate Ras, which in turn may activate p110γ, one may imagine that fMLP-induced, p101-independent stimulation of p110γ-CAAX was mediated by Ras. However, coexpression of dominant-negative Ras N17 had no effect on fMLP-induced p110γ-CAAX stimulation, whereas its inhibitory effect was evident when EGF-induced MAP kinase activation was assessed (Fig. 7 A, bottom panel). In addition, an indirect autocrine stimulatory effect was excluded because supernatants of fMLP-stimulated cells failed to induce GFP-GRP1PH translocation in cells omitting fMLP receptors (unpublished data).

Figure 7.

Activation of a constitutively membrane-associated p110γ-CAAX. (A) GFP-GRP1PH translocation. HEK cells were transfected with plasmids for GFP-GRP1PH and p110γ-CAAX, p101, fMLP-R, and dominant-negative Ras N17 in different combinations. Translocation of the PtdIns-3,4,5-P3–binding GFP-GRP1PH in response to agonist stimulation was monitored as described above (see Fig. 5). White bars indicate a 10-μm scale. As a positive control for H-Ras N17, cells were transfected with the H-Ras N17 plasmid (same amount as for the GFP-GRP1PH translocation experiment) or empty vector. Cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml EGF, and whole-cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylated form of ERK (p-ERK). Equal loading was shown using the anti-ERK-antibody. (B) BtkPH-CFP translocation. (C) Akt phosphorylation. The experiment shown in Fig. 5 was repeated. In addition, cells were transfected with the plasmid for the membrane-targeted p110γ-CAAX instead of wild-type p110γ.

By using BtkPH-CFP instead of GFP-GRP1PH as the PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 sensor, we confirmed both the basal enzymatic activity and fMLP-induced stimulation of membrane-targeted p110γ-CAAX, regardless of coexpressed p101 (Fig. 7 B). Furthermore, the Akt phosphorylation assay corroborated that p101 was dispensable for GPCR-induced stimulation of membrane-targeted p110γ-CAAX (Fig. 7 C).

Next, we sought to confirm our principal findings using nontransformed cells in primary culture with a higher degree of differentiation than HEK cells. Vascular smooth muscle (VSM) cells were injected with plasmids encoding the fMLP receptor, p101, p110γ or p110γ-CAAX, and GFP-GRP1PH in different combinations, and redistribution of the fluorescent PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 sensor was monitored (Fig. 8). Again, this series of experiments confirmed that p101 is required for GPCR-mediated activation of PI3Kγ in living cells, whereas membrane-targeted p110γ can be stimulated even in the absence of p101.

Figure 8.

PI3Kγ-mediated membrane translocation of GFP-GRP1 PH in vascular smooth muscle (VSM) cells. VSM cells were microinjected with plasmids for GFP-GRP1PH, fMLP-R, p101, and p110γ or p110γ-CAAX in different combinations. The localization of GFP-GRP1PH was monitored before and after the addition of 1 μM fMLP (picture taken after 4 min) and 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB (added 12 min later, picture taken after 8 min). White bars indicate a 10-μm scale.

Discussion

PI3Kγ is a key player in the regulation of leukocyte functions such as chemotaxis and superoxide production (Katso et al., 2001). To elucidate the mechanism of how Gβγ activates the enzyme in vivo, we studied the subcellular localization and translocation of GFP-tagged PI3Kγ subunits and PH domains in living cells.

A p110γ-GFP construct has been previously reported (Metjian et al., 1999), but data describing a functional interaction of the fusion protein with G proteins are not available. Therefore, we systematically tagged each PI3Kγ subunit and found heterodimerization, enzymatic activity, and Gβγ-sensitivity of the fusion proteins unaffected by the tags, whereas a GFP-tagged Gβ complexed to Gγ did not interact with PI3Kγ (unpublished data). In resting cells, fluorescent PI3Kγ was predominantly detected in the cytosol. This resembles the native situation in which the vast majority of the endogenous PI3Kγ pool has been assigned to the cytosol (Stephens et al., 1994, 1997; Tang and Downes, 1997). Thus, the GFP-tagged proteins are appropriate tools to study the cellular events leading to activation of PI3Kγ.

Recent analysis of p110γ crystals gave insights into the three-dimensional structure of the catalytic PI3Kγ subunit (Walker et al., 1999; Pacold et al., 2000). However, the structure of p101 and the molecular determinants for the interaction of both PI3Kγ subunits are currently unknown. In vitro data derived from p101 and p110γ deletion mutants suggest that large areas of p101 may interact with the NH2-terminal side of p110γ (Krugmann et al., 1999). FRET data presented here indicate that NH2 and both COOH termini of p110γ and p101 are in close proximity. The latter finding is of interest because the p110γ COOH terminus harbors the catalytic domain. Previous data have implied that not only Ras (Pacold et al., 2000), but also Gβγ (Leopoldt et al., 1998) directly interact with the COOH terminus of p110γ. Therefore, interaction of p101 with the catalytic domain of p110γ would be in line with the functional data suggesting that p101 affects interaction of Gβγ-stimulated p110γ with the lipid interface (Maier et al., 1999).

Gβγ is considered to be the principal, direct stimulus of GPCR-induced PI3Kγ enzymatic activity. Convincing evidence for this assumption has come from reconstitution of purified proteins, demonstrating that in vitro, the enzymatic activity of heterodimeric and monomeric PI3Kγ is significantly stimulated by Gβγ (Stoyanov et al., 1995; Stephens et al., 1997; Tang and Downes, 1997; Leopoldt et al., 1998). However, when we challenged the concept in living cells, marked differences in the sensitivities between heterodimeric and monomeric PI3Kγ emerged. The G protein–coupled fMLP receptor activated p110γ/p101, but not p110γ, as evident from the translocation of fluorescent PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 sensors or the stimulation of Akt phosphorylation. Likewise, coexpressed Gβγ recruited p110γ/p101, but not p110γ, to membranes of HEK cells. Interestingly, PI3Kβ, another Gβγ-regulated PI3K, did not translocate to the membrane on GPCRs or Gβγ stimulation, whereas RTKs induced membrane recruitment in vivo (unpublished data).

Does membrane recruitment of PI3Kγ by itself result in constitutive activation of p110γ? To answer this intriguing question, we used an isoprenylated mutant of p110γ, i.e., p110γ-CAAX, which is permanently attached to the membrane, and thereby, is in close proximity to its lipid substrates. Expression of p110γ-CAAX only slightly enhanced membrane association of fluorescent PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 sensors in HEK or VSM cells. Notably, it did not affect the morphology of HEK cells. In contrast, coexpression of Gβγ together with p110γ-CAAX induced morphological changes comparable to cells transfected with plasmids encoding Gβγ and p110γ/p101. Furthermore, stimulation of the cells with fMLP stimulated Akt phosphorylation and membrane recruitment of PH domains regardless of whether p110γ/p101 or p110γ-CAAX was the effector. This establishes a second role for Gβγ, i.e., the activation of the membrane-attached catalytic p110γ subunit even in the absence of p101 (Fig. 9). Although Gβγ interacts with either monomeric PI3Kγ subunit through individual binding sites, it does not exclude the possibility that heterodimeric PI3Kγ forms either a common or different binding site(s) for Gβγ. Attempts to determine the stoichiometry of the interaction between heterodimeric PI3Kγ and one or more Gβγ were inconclusive. One possible reason may be a weak affinity between p110γ and Gβγ, whereas p101 binds at least with moderate affinity to Gβγ as determined by copurification studies (Stephens et al., 1997; Krugmann et al., 1999; Maier et al., 1999) and by a Biacore plasmon resonance approach (unpublished data).

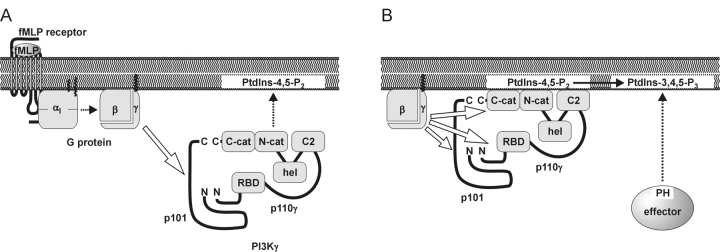

Figure 9.

Hypothetical model for receptor- induced membrane recruitment and activation of heterodimeric PI3Kγ. fMLP receptor, a prototypical heptahelical receptor coupled to Gi proteins. PI3Kγ; the cytosolic enzyme consists of a noncatalytic p101 subunit, which is in a tight complex with p110γ, thereby stabilizing p101. The NH2 and COOH termini of p101 and p110γ are oriented in close proximity, respectively. Contact sites involve the NH2 termini of both subunits. The modular domain structure of p110γ (RBD, Ras binding domain; C2, C2 domain; hel, helical domain; N-cat, C-cat, NH2- and COOH-terminal lobes of the catalytic domain) is based on the crystal structure of an NH2-terminally truncated p110γ. (A) Membrane recruitment. The agonist-stimulated receptor induces the release of Gβγ from Gi proteins (dotted arrow). Gβγ recruits the PI3Kγ heterodimer to the plasma membrane (dotted arrow) by binding to the noncatalytic p101 (hollow arrow). Accordingly, Gβγ and p101 function as a membrane anchor and an adaptor for PI3Kγ, respectively. In addition, the C2 domain of p110γ may facilitate membrane attachment through interaction with phospholipids. p101 may also affect the interaction of PI3Kγ with the lipid interface. Membrane-attached PI3Kγ exhibits basal enzymatic activity. (B) Allosteric activation. At the membrane, Gβγ activates PI3Kγ by direct interaction with p110γ (hollow arrows). This stimulation does not require p101. However, p101 may participate in Gβγ-induced stimulation of membrane-attached p110γ. The stoichiometry of the Gβγ–PI3Kγ interaction is unknown, i.e., Gβγ may interact with p101 and p110γ through individual or common binding sites. Gβγ binds to the NH2- and COOH-terminal part of p110γ, the latter harboring the catalytic domain. Thus, Gβγ may allosterically activate PI3Kγ through a conformational change in the catalytic domain. Accordingly, Gβγ significantly increases Vmax of PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 production. PtdIns-3,4,5-P3, in turn, recruits PH domain–containing effectors such as GRP1 or Btk to the plasma membrane (dotted arrow).

In our paper, we present evidence that p110γ is stable as a monomer without p101, but not vice versa. This may explain why relevant amounts of native monomeric p101 do not occur in vivo (Wetzker, R., personal communication). p110γ can be expressed as a stable protein independent of the presence of p101, as shown previously (Fig. 2 C; Lopez-Ilasaca et al., 1997, 1998; Leopoldt et al., 1998; Maier et al., 1999). Interestingly, the p110 subunit of class IA PI3Ks needs stabilization by forming a complex with the p85 adaptor (Yu et al., 1998). Accordingly, class IA p110α,β,δ subunits are thought to occur only in their adaptor-bound form. Moreover, the p85 adaptor is more abundant than the p110 counterparts (Ueki et al., 2002). In contrast, p110γ is also suggested to occur in the absence of p101 (Baier et al., 1999).

Increasing evidences suggest that monomeric p110γ may also function as a downstream regulator of GPCR-dependent signal transduction pathways in cells (Lopez-Ilasaca et al., 1997, 1998; Bondeva et al., 1998; Murga et al., 1998; Baier et al., 1999). However, under in vivo conditions the p101 subunit seems mandatory for G protein–mediated activation of PI3Kγ by mediating membrane recruitment. Therefore, the question arises of how monomeric p110γ translocates to the membrane. In this context, recent in vitro evidence points to the possibility that membrane attachment of p110γ may involve binding to anionic phospholipids (Kirsch et al., 2001). In line with this finding, the majority of PI3Kγ is already associated with lipid vesicles in the absence of Gβγ under in vitro conditions, and vesicle-bound PI3Kγ can still be activated by Gβγ (Krugmann et al., 2002). Alternatively, p110γ may be recruited by binding to membrane-anchored proteins other than Gβγ. In this respect, p110γ, like all other class I PI3Ks, is directly activated by GTP-bound Ras (Pacold et al., 2000).

In conclusion, we present in vivo evidence that Gβγ may stimulate PI3Kγ in a dual and complementary way, i.e., by recruitment to the membrane, and by activation of the membrane-bound enzyme (Fig. 9). In this scenario, the p101 subunit functions as an adaptor molecule necessary to recruit the catalytic subunit to the plasma membrane through high affinity interaction with Gβγ. In turn, direct interaction between Gβγ and the membrane-attached catalytic p110γ subunit contributes to a final activation of the enzyme by a mechanism other than translocation.

Materials and methods

Construction of expression plasmids

For generation of expression plasmids of PI3Kγ subunits, restriction sites were introduced, and stop codons were removed by 8–12 cycles of PCR using the indicated primers, a PCR system (Expand HF; Roche), and a pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) for first subcloning. Subcloned PCR fragments were confirmed by sequencing with fluorescent dye terminators (ABI-Prism 377; PerkinElmer). Expression plasmids encoding NH2- and COOH-terminally tagged fusion proteins were generated by subsequent subcloning into the vectors pEYFP-C1 and pECFP-C1 (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) or into pcDNA3-YFP and pcDNA3-CFP (Schaefer et al., 2001), respectively. The constructs are designated indicating the color and the position of the tag (see Fig. 1 A). In detail, wild-type p110γ; human p110γ cDNA (Stoyanov et al., 1995; a corrected nucleotide sequence for p110γ is available from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ, accession no. AF327656) was amplified with the primers 5′-GCC ACC ATG GAG CTG GAG AAC TAT AA-3′ and 5′-GGA TCC AGC TTT CAC AAT GTC TAT TG-3′, and subcloned into pcDNA3 via KpnI and XhoI. p110γ-YFP and -CFP; the stop codon was replaced by an XbaI site using the primer 5′-GTC TAG AGC TGA ATG TTT CTC TCC CTT GT-3′ and the same forward primer as above. Subcloning into pcDNA3-YFP and -CFP was done via BamHI and XbaI. YFP- and CFP-p110γ; XhoI and BamHI sites were introduced using the primers 5′-CTC GAG GCA TGG AGC TGG AGA ACT A-3′ and 5′-GGA TCC AGC TTT CAC AAT GTC TAT TG-3′ for subcloning into pEYFP-C1 and pECFP-C1. p110γ-K833R; position 2498 was mutated from A to G using the QuikChange® Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) and appropriate primers. p110γ-CAAX; two AfeI sites in p110γ were removed, and the stop codon was replaced by a new AfeI site by silent mutations using the QuikChange® Mutagenesis Kit and appropriate primers. Adaptor oligonucleotides encoding the 18 COOH-terminal amino acids of H-Ras were inserted into the AfeI and BamHI sites. Wild-type p101; the cDNA for porcine p101 (Stephens et al., 1997) was subcloned in pcDNA3 via EcoRI and NotI. An optimized ribosomal docking sequence was introduced by PCR using the primers 5′-GCC ACC ATG CAG CCA GGG GCC ACG GA-3′ and 5′-GGC CCG AGA CGA AGG AGG T-3′ and subsequent exchange of the 5′-end via HindIII and BsmBI. YFP- and CFP-p101; the EcoRI/NotI fragment of p101 was subcloned into EcoRI/Bsp120I-digested pEYFP-C1 or pECFP-C1. To adapt the reading frames, the HindIII site was blunted with Klenow fragment (New England Biolabs, Inc.) and religated. p101-YFP and -CFP; PCR with the primers 5′-GTC CTC TCC TCA CAC GGT TCT T-3′ and 5′-GTC TAG AGG CAG AGC TCC GCT GAA AGT-3′ generated the 3′-end of p101 with an XbaI site instead of the stop codon. To restore the full-length p101 cDNA, the 5′-part was excised from wild-type p101 in pcDNA3 with HindIII and ClaI (partial digest) and ligated to the HindIII/ClaI-digested 3′-end. Subsequent subcloning in pcDNA3-YFP and pcDNA3-CFP was done via HindIII and XbaI.

The human fMLP receptor cDNA (Boulay et al., 1990) was amplified with the primers 5′-GCC ACC ATG GAG ACA AAT TCC TCT CTC-3′ and 5′-TCA CTT TGC CTG TAA CTC CAC-3′ and subcloned in pcDNA3 via HindIII and XhoI. The cDNAs of Gαi2 (Conklin et al., 1993), human Gβ1 (Codina et al., 1986), and bovine Gγ2 (Gautam et al., 1989) were subcloned into pcDNA3. Plasmids for GFP-GRP1PH and Ras N17 are described elsewhere (Ridley et al., 1992; Gray et al., 1999).

For generation of expression plasmids encoding CFP-tagged Gβ1 and BtkPH, restriction sites were introduced by PCR using the indicated primers, the Advantage™ II PCR enzyme system (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) and the pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Promega) for first subcloning. The Gβ1 cDNA was amplified using the primers 5′-TAC AAG TCC GGA CAA GCT TCC ATG AGT GAG CTT GAC CAG TTA CGG C-3′ and 5′-CGG GAT CCG TCG ACC CAT GGT GGC GTT AGT TCC AGA TCT TGA GGA AGC-3′, allowing for in-frame subcloning into the HindIII and BamHI sites of pECFP-C1. The cDNA encoding the PH domain of human Btk (Várnai et al., 1999) and adjacent 5′ untranslated bases was amplified from cDNA of dibuturyl-cAMP–differentiated HL-60 cells using the primers 5′-CCA AGT CCT GGC ATC TCA ATG CAT CTG-3′ and 5′-TGG AGA CTG GTG CTG CTG CTG GCT C-3′. A nested PCR was performed using the primers 5′-GGA AGA TCT CGA GCC ACC ATG GCC GCA GTG ATT CTG G-3′ and 5′-GGG GAT CCC GGG CCC GAG GTT TTA AGC TTC CAT TCC TGT TCT CC-3′, allowing for in-frame subcloning into the XhoI and BamHI sites of pECFP-N1 (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.). The cDNA inserts and flanking regions of the resulting CFP-Gβ1 and BtkPH-CFP constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell culture, transfection, and intranuclear microinjection

HEK 293 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DME or in MEM with Earle's salts supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin. All transfections were done with a FuGENE™ 6 transfection reagent (Roche) following the manufacturer's recommendations. For fluorescence microscopy experiments, cells were seeded on glass coverslips. For confocal imaging of the subcellular localization of the PI3Kγ subunits, cells were transfected with 0.1 μg of plasmid encoding YFP-tagged PI3Kγ subunits, 0.2 μg of plasmid for the untagged complementary subunit, and 1 μg each of plasmid for Gβ1 and Gγ2 (except for the experiment shown in Fig. 4 B; 0.1 μg YFP-p101 + 2 μg Gβ1 or Gγ2 alone, or 0.5 μg Gβ1 + 0.5 μg Gγ2 + 1 μg Gαi2). For monitoring PH domain translocation, or Akt- or ERK phosphorylation, HEK cells were transfected with 0.2 μg plasmid encoding the fMLP receptor, and 0.4 μg each of the plasmids encoding the PI3Kγ subunits and the fluorescent PH domain. The total amount of transfected cDNA was always kept constant (2.5 μg/well) by the addition of empty expression vector. For FRET analysis, cells were transfected with 1.5 μg of plasmid encoding the YFP-tagged p110γ and 0.5 μg of plasmid for CFP-tagged p101. All experiments were performed one or two days after transfection.

VSM cells from neonatal rat aortas were cultured as described previously (Reusch et al., 2001). Cells were seeded on glass coverslips and microinjected with the plasmids for GFP-GRP1PH (0.4 μg/ml), fMLP receptor (0.05 μg/ml), p110γ (0.05 μg/ml), and p101 (0.05 μg/ml) using an Eppendorf micromanipulator and transjector. Confocal images were taken one day after microinjection.

Immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates, gel filtration, and membrane fractions

p110γ/p101 titration; transfected HEK cells were lysed in Laemmli buffer and whole-cell lysates including nuclei were subjected to a 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were blotted on nitrocellulose membranes, probed with anti-GFP (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) and peroxidase-coupled anti–rabbit IgG antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) and visualized by ECL (Amersham Biosciences). Akt and ERK phosphorylation; HEK 293 cells were transfected as indicated with the plasmids encoding the fMLP receptor (0.2 μg), PI3Kγ subunits (each 0.4 μg), and H-Ras N17 (1.5 μg). Cells were serum-starved overnight, then stimulated as indicated, and lysed in Laemmli buffer. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, and probed with anti–Phospho-Akt or anti–Phospho-ERK1/2 and anti-ERK1/2 as described previously (Reusch et al., 2001). Gel filtration; HEK cells were transfected with equal amounts of the plasmids for YFP-p110γ (or p110γ-YFP) and CFP-p101 (or pcDNA3). Cells were washed in PBS and lysed in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 4 mM EDTA, 0.2% polyoxyethylene-10-laurylether (C12E10), 200 μM Pefabloc® SC, 30 μg/ml TPCK, 30 μg/ml trypsin inhibitor, and 50 μg/ml benzamidine by repetitive aspiration through a 26-gauge needle. Cytosols were prepared (100,000 g for 30 min at 4°C), and subjected to gel filtration on a 24-ml Superdex 200 column and eluted with the same buffer on an ÄKTA™ purifier system (Amersham Biosciences). Fractions were collected, and aliquots were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-GFP. Preparation of membrane fractions; HEK cells were transfected as indicated with the plasmids for YFP-p110γ-K833R (0.1 μg), p101 (0.2 μg), Gβ1 (1.0 μg), and Gγ2 (1.0 μg). Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in PBS with protease inhibitors (see above) by repetitive aspiration through a 26-gauge needle. Membranes were prepared (16,000 g for 20 min at 4°C), redissolved in Laemmli buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, and probed with anti-p110γ (see next section) and anti-Gβcommon (AS398; Leopoldt et al., 1997).

In vitro PI3K assay

HEK cells were transfected with equal amounts of the plasmids encoding p110γ and p101 (or empty pcDNA3 to keep the total amount of transfected cDNA constant). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using a monoclonal anti-p110γ antibody (Bondev et al., 2001). In brief, protein A Sepharose was preincubated with or without antibody, washed, incubated overnight with cleared lysates, and washed again. The in vitro PI3K assay was performed as described previously (Maier et al., 1999). Radioactive PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 was visualized with a PhosphorImager (Fuji Bas-Reader 1500; Ray Test).

Fluorescence imaging and detection of FRET

Glass coverslips were mounted on a custom-made chamber and covered with a Hepes-buffered solution containing 138 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 5.5 mM glucose, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and 2 mg/ml BSA. For confocal imaging, an inverted confocal laser scanning microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 objective (model LSM 510; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) was used. YFP or GFP were excited at 488 nm, and fluorescence emission was detected through a 505-nm long pass filter. CFP was excited 458 nm, and detected through a 475-nm long pass filter. Pinholes were adjusted to yield optical sections of 0.5–1.5 μm.

FRET analysis was performed using an inverted microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 objective (Axiovert 100; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). CFP and YFP were alternately excited at 440 and 500 nm with a monochromator (Polychrome II; TILL Photonics) in combination with a dual reflectivity dichroic mirror (<460 nm and 500–520 nm; Chroma Technology Corp.). Emitted light was filtered through 475–505-nm (CFP) and 535–565-nm (YFP) band pass filters, changed by a motorized filter wheel (Lambda 10/2; Sutter Instrument Co.), and detected by a cooled CCD camera (Imago; TILL Photonics). FRET was assessed as recovery of CFP (donor) fluorescence during YFP (acceptor) bleach. First, CFP and YFP fluorescences without acceptor bleach were recorded during 30 cycles with a 10–20-ms exposure. Then, 60 cycles were recorded with an additional 2-s illumination per cycle at 510 nm to bleach YFP.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Claudia Plum, A. Schulz and J. Malkewitz for technical assistance. We are grateful to Drs. P. Gierschik, A. Gray and P. Downes, M.I. Simon, L. Stephens and P. Hawkins, and R. Wetzker for providing experimental tools. Thanks to Celsa Antao-Paetsch for assistance in preparation of the manuscript. We appreciate valuable discussions with Drs. Len Stephens, Phil Hawkins, Lewis Cantley, Reinhard Wetzker, and Roland Piekorz.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: Btk, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; fMLP, formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; GPCR, G protein–coupled receptor; GRP1, general receptor for phosphoinositides-1; HEK, human embryonic kidney; PH, pleckstrin homology; PtdIns, phosphatidylinositol; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PTX, pertussis toxin; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; VSM, vascular smooth muscle.

References

- Al-Aoukaty, A., B. Rolstad, and A.A. Maghazachi. 1999. Recruitment of pleckstrin and phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ into the cell membranes, and their association with Gβγ after activation of NK cells with chemokines. J. Immunol. 162:3249–3255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla, T., T. Bondeva, and P. Várnai. 2000. How accurately can we image inositol lipids in living cells? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 21:238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier, R., T. Bondeva, R. Klinger, A. Bondev, and R. Wetzker. 1999. Retinoic acid induces selective expression of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ in myelomonocytic U937 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 10:447–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondev, A., T. Bondeva, and R. Wetzker. 2001. Regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ protein kinase activity in vitro and in COS-7 cells. Signal Transduction. 1:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bondeva, T., L. Pirola, G. Bulgarelli-Leva, I. Rubio, R. Wetzker, and M.P. Wymann. 1998. Bifurcation of lipid and protein kinase signals of PI3Kγ to the protein kinases PKB and MAPK. Science. 282:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay, F., M. Tardif, L. Brouchon, and P. Vignais. 1990. The human N-formylpeptide receptor. Characterization of two cDNA isolates and evidence for a new subfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochemistry. 29:11123–11133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley, L.C. 2002. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 296:1655–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codina, J., D. Stengel, S.L. Woo, and L. Birnbaumer. 1986. β-subunits of the human liver Gs/Gi signal-transducing proteins and those of bovine retinal rod cell transducin are identical. FEBS Lett. 207:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin, B.R., Z. Farfel, K.D. Lustig, D. Julius, and H.R. Bourne. 1993. Substitution of 3 amino acids switches receptor specificity of Gqα to that of Giα. Nature. 363:274–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman, D.A., R.E. Meyers, and L.C. Cantley. 1998. Phosphoinositide kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:481–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, N., M. Baetscher, R. Aebersold, and M.I. Simon. 1989. A G protein γ subunit shares homology with ras proteins. Science. 244:971–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham, H., M.C. Golding, R. Pepperkok, and W.J. Gullick. 1999. Intracellular movement of green fluorescent protein-tagged phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in response to growth factor receptor signaling. J. Cell Biol. 146:869–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, A., J. Van Der Kaay, and C.P. Downes. 1999. The pleckstrin homology domains of protein kinase B and GRP1 (general receptor for phosphoinositides-1) are sensitive and selective probes for the cellular detection of phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate and/or phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in vivo. Biochem. J. 344:929–936. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, J.H., and S. Misra. 2000. Signaling and subcellular targeting by membrane-binding domains. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29:49–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katso, R., K. Okkenhaug, K. Ahmadi, S. White, J. Timms, and M.D. Waterfield. 2001. Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17:615–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch, C., R. Wetzker, and R. Klinger. 2001. Anionic phospholipids are involved in membrane targeting of PI3-kinase γ. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 282:691–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klippel, A., C. Reinhard, W.M. Kavanaugh, G. Apell, M.A. Escobedo, and L.T. Williams. 1996. Membrane localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is sufficient to activate multiple signal-transducing kinase pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:4117–4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugmann, S., P.T. Hawkins, N. Pryer, and S. Braselmann. 1999. Characterizing the interactions between the two subunits of the p101/p110γ phosphoinositide 3-kinase and their role in the activation of this enzyme by Gβγ subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17152–17158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugmann, S., M.A. Cooper, D.H. Williams, P.T. Hawkins, and L.R. Stephens. 2002. Mechanism of the regulation of type IB phosphoinositide 3OH-kinase by G-protein βγ subunits. Biochem. J. 362:725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu, H., T. Maehama, T. Okada, T. Yamamoto, S. Hoshino, Y. Fukui, M. Ui, O. Hazeki, and T. Katada. 1997. Heterodimeric phosphoinositide 3-kinase consisting of p85 and p110β is synergistically activated by the βγ subunits of G proteins and phosphotyrosyl peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24252–24256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopoldt, D., C. Harteneck, and B. Nürnberg. 1997. G proteins endogenously expressed in Sf 9 cells: interactions with mammalian histamine receptors Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 356:216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopoldt, D., T. Hanck, T. Exner, U. Maier, R. Wetzker, and B. Nürnberg. 1998. Gβγ stimulates phosphoinositide 3-kinase-γ by direct interaction with two domains of the catalytic p110 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 273:7024–7029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lietzke, S.E., S. Bose, T. Cronin, J. Klarlund, A. Chawla, M.P. Czech, and D.G. Lambright. 2000. Structural basis of 3-phosphoinositide recognition by pleckstrin homology domains. Mol. Cell. 6:385–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ilasaca, M., P. Crespo, P.G. Pellici, J.S. Gutkind, and R. Wetzker. 1997. Linkage of G protein-coupled receptors to the MAPK signaling pathway through PI3-kinase γ. Science. 275:394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ilasaca, M., J.S. Gutkind, and R. Wetzker. 1998. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ is a mediator of Gβγ-dependent Jun kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 273:2505–2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier, U., A. Babich, and B. Nürnberg. 1999. Roles of non-catalytic subunits in Gβγ-induced activation of class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase isoforms β and γ. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29311–29317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier, U., A. Babich, N. Macrez, D. Leopoldt, P. Gierschik, D. Illenberger, and B. Nürnberg. 2000. Gβ5γ2 is a highly selective activator of phospholipid-dependent enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:13746–13754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metjian, A., R.L. Roll, A.D. Ma, and C.S. Abrams. 1999. Agonists cause nuclear translocation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase γ. A Gβγ-dependent pathway that requires the p110γ amino terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 274:27943–27947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga, C., L. Laguinge, R. Wetzker, A. Cuadrado, and J.S. Gutkind. 1998. Activation of Akt/protein kinase B by G protein-coupled receptors. A role for α and βγ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins acting through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase γ. J. Biol. Chem. 273:19080–19085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naccache, P.H., S. Levasseur, G. Lachance, S. Chakravarti, S.G. Bourgoin, and S.R. McColl. 2000. Stimulation of human neutrophils by chemotactic factors is associated with the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase γ. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23636–23641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacold, M.E., S. Suire, O. Perisic, S. Lara-Gonzalez, C.T. Davis, E.H. Walker, P.T. Hawkins, L. Stephens, J.F. Eccleston, and R.L. Williams. 2000. Crystal structure and functional analysis of Ras binding to its effector phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ. Cell. 103:931–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reusch, H.P., M. Schaefer, C. Plum, G. Schultz, and M. Paul. 2001. Gβγ mediate differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:19540–19547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, A.J., H.F. Paterson, C.L. Johnston, D. Diekmann, and A. Hall. 1992. The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell. 7:401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, M., N. Albrecht, T. Hofmann, T. Gudermann, and G. Schultz. 2001. Diffusion-limited translocation mechanism of protein kinase C isotypes. FASEB J. 15:1634–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, A., A.E. Wurmser, S.D. Emr, and H. Stenmark. 2001. The role of phosphoinositides in membrane transport. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, L.R., T.R. Jackson, and P.T. Hawkins. 1993. Agonist-stimulated synthesis of phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-trisphosphate: a new intracellular signalling system? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1179:27–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, L., A. Smrcka, F.T. Cooke, T.R. Jackson, P.C. Sternweis, and P.T. Hawkins. 1994. A novel phosphoinositide 3 kinase activity in myeloid-derived cells is activated by G protein βγ subunits. Cell. 77:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, L.R., A. Eguinoa, H. Erdjument-Bromage, M. Lui, F. Cooke, J. Coadwell, A.S. Smrcka, M. Thelen, K. Cadwallader, P. Tempst, and P.T. Hawkins. 1997. The Gβγ sensitivity of a PI3K is dependent upon a tightly associated adaptor, p101. Cell. 89:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov, B., S. Volinia, T. Hanck, I. Rubio, M. Loubtchenkov, D. Malek, S. Stoyanova, B. Vanhaesebroeck, R. Dhand, B. Nürnberg, et al. 1995. Cloning and characterization of a G protein-activated human phosphoinositide-3 kinase. Science. 269:690–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X., and C.P. Downes. 1997. Purification and characterization of Gβγ-responsive phosphoinositide 3-kinases from pig platelet cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 272:14193–14199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruel, M.N., and T. Meyer. 2000. Translocation and reversible localization of signaling proteins: a dynamic future for signal transduction. Cell. 103:181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki, K., D.A. Fruman, S.M. Brachmann, Y.H. Tseng, L.C. Cantley, and C.R. Kahn. 2002. Molecular balance between the regulatory and catalytic subunits of phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates cell signaling and survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:965–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaesebroeck, B., S.J. Leevers, K. Ahmadi, J. Timms, R. Katso, P.C. Driscoll, R. Woscholski, P.J. Parker, and M.D. Waterfield. 2001. Synthesis and function of 3-phosphorylated inositol lipids. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:535–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Várnai, P., K.I. Rother, and T. Balla. 1999. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent membrane association of the Bruton's tyrosine kinase pleckstrin homology domain visualized in single living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10983–10989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, E.H., O. Perisic, C. Ried, L. Stephens, and R.L. Williams. 1999. Structural insights into phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalysis and signalling. Nature. 402:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, M.J., G.S. Taylor, and J.E. Dixon. 2001. Phoxy lipids: Revealing PX domains as phosphoinositide binding modules. Cell. 105:817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J., Y. Zhang, J. McIlroy, T. Rordorf-Nikoloic, G.A. Orr, and J.M. Backer. 1998. Regulation of the p85/p110 phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase: stabilization and inhibition of the p110α catalytic subunit by the p85 regulatory subunit. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1379–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]