Abstract

In hippocampal neurons and transfected CHO cells, neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) 120, NCAM140, and NCAM180 form Triton X-100–insoluble complexes with βI spectrin. Heteromeric spectrin (αIβI) binds to the intracellular domain of NCAM180, and isolated spectrin subunits bind to both NCAM180 and NCAM140, as does the βI spectrin fragment encompassing second and third spectrin repeats (βI2–3). In NCAM120-transfected cells, βI spectrin is detectable predominantly in lipid rafts. Treatment of cells with methyl-β-cyclodextrin disrupts the NCAM120–spectrin complex, implicating lipid rafts as a platform linking NCAM120 and spectrin. NCAM140/NCAM180–βI spectrin complexes do not depend on raft integrity and are located both in rafts and raft-free membrane domains. PKCβ2 forms detergent-insoluble complexes with NCAM140/NCAM180 and spectrin. Activation of NCAM enhances the formation of NCAM140/NCAM180–spectrin–PKCβ2 complexes and results in their redistribution to lipid rafts. The complex is disrupted by the expression of dominant-negative βI2–3, which impairs binding of spectrin to NCAM, implicating spectrin as the bridge between PKCβ2 and NCAM140 or NCAM180. Redistribution of PKCβ2 to NCAM–spectrin complexes is also blocked by a specific fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor. Furthermore, transfection with βI2–3 inhibits NCAM-induced neurite outgrowth, showing that formation of the NCAM–spectrin–PKCβ2 complex is necessary for NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth.

Keywords: NCAM; spectrin; PKC; neurons; outgrowth

Introduction

The formation, guidance, and stabilization of neurites, i.e., axons and dendrites, is a feature of both the developing and adult nervous system, and is critical for synaptic remodeling during memory formation or repair of neuronal injury. Recognition molecules at the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix provide short- and long-range cues that trigger these processes (Tessier-Lavigne and Goodman, 1996). Recognition cues act via transmembrane glycoproteins to recruit and assemble cell-specific subplasmalemmal protein complexes that regulate cell behavior. These complexes act as organized signaling platforms, controlling signal quality and strength, and locally organize the cytoskeleton. In turn, the cytoskeleton itself may form a scaffold upon which signaling complexes are assembled, and thereby become an integral component of the signaling machinery.

Typically, cell surface transmembrane receptors involved in cell–cell and cell–matrix recognition interact with the cytoskeleton. The integrin receptors that bind to the extracellular matrix organize complex ensembles of interacting cytoskeletal proteins such as talin, tensin, vinculin, actin, and α-actinin (Fields and Itoh, 1996; Juliano, 2002). The classical cadherins bind both actin and spectrin via α-catenin, a cytoplasmic adaptor protein (Rimm et al., 1995; Gumbiner, 2000; Pradhan et al., 2001). The immunoglobulin superfamily recognition molecule L1 and other L1 family members, such as CHL1, neurofascin, NgCAM, NrCAM, and neuroglian, bind to ankyrin, a large adaptor protein with binding sites for spectrin (De Matteis and Morrow, 2000; Bennett and Baines, 2001). Another example is neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM)* 180, the largest major isoform of NCAM, which interacts with spectrin (Pollerberg et al., 1986, 1987).

Spectrin is now recognized as a ubiquitous scaffolding protein that acts in conjunction with a variety of adaptor proteins to organize membrane microdomains on both the plasma membrane as well as on intracellular organelles. Spectrin can also link membranes and membrane protein complexes to filamentous actin or to microtubule transport motors (dynein–dynactin and some kinesins) (for reviews see Hirokawa, 1998; De Matteis and Morrow, 2000). The functional unit of spectrin is an α,β heterodimer, although homopolymeric forms exist (Bloch and Morrow, 1989). Two spectrin genes encode α-type subunits, and five genes encode the β spectrins. Spectrin–membrane interactions are mediated by both protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions. The most studied interactions operate through ankyrin. These join spectrin to a variety of membrane receptors and channels, including Na,K-ATPase, voltage-gated Na+ channel, and tyrosine phosphate phosphatase CD45. Ankyrin-independent association with proteins, such as complexes of cadherin–catenin and NCAM180–spectrin, as well as with cortical actin, offers additional pathways of membrane interaction. Finally, many β spectrins contain a pleckstrin homology domain. This domain mediates a direct interaction of spectrin with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdInsP2) and other acidic phospholipids.

Different β spectrin isoforms play specific roles in the formation of unique membrane microdomains. For example, whereas βII spectrin, the most widely distributed isoform, tends to be fairly uniformly distributed over the plasmalemma of neurons and other cells, βI spectrin sorts to specific organelles (De Matteis and Morrow, 2000) and to organized plasma membrane domains, such as the motor end plate of skeletal muscle (Bloch and Morrow, 1989), the postsynaptic density of cerebellar neurons (Malchiodi-Albedi et al., 1993), or to CD45-rich patches in T cells (Pradhan and Morrow, 2002). βI spectrin transcripts are now recognized in many nonerythroid cells, including neurons, lymphocytes, and epithelial cells. βIII spectrin is another widely expressed spectrin associated with intracellular organelles and the plasma membrane. Given the close association of spectrin with membrane-associated receptor clusters in muscle, neurons, and lymphocytes, it is likely that spectrin may trap or stabilize proteins at specific loci in neural membranes. However, little is known of the mechanisms that guide spectrin to membrane domains, or the consequences of its participation in cell interactions.

In the present study, and given our earlier observations that NCAM180 associates with spectrin in the brain (Pollerberg et al., 1986, 1987), we have hypothesized that NCAM might initiate the segregation of spectrin to localized membrane microdomains. We have chosen here to study βI spectrin, as it is the isoform most often associated with discrete receptor and organelle compartments, and is the form most prominent in postsynaptic densities. We find evidence for a direct interaction of the cytoplasmic domain of NCAM180 and NCAM140 with this spectrin and their colocalization in discrete membrane clusters. Building on observations that spectrin binds activated PKC (Rodriguez et al., 1999) and that PKC mediates NCAM-dependent neurite outgrowth (Kolkova et al., 2000a), we show that PKCβ2, an isoform enriched in neurons, interacts with NCAM140 and NCAM180 via spectrin in a fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)–dependent manner. Activation of NCAM results in a redistribution of the NCAM–βI spectrin–PKCβ2 complex to lipid-enriched microdomains to mediate neurite outgrowth.

Results

NCAM120, NCAM140, and NCAM180 form a 1% Triton X-100–insoluble complex with βI spectrin

To identify cytoskeletal components interacting with NCAM, we performed double immunofluorescence labeling of cultured hippocampal neurons using antibodies against all NCAM isoforms along with markers of microtubules, microfilaments, or spectrin. The NCAM and βI spectrin (hereafter called spectrin) distributions along neurites were similar (see Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200303020/DC1), with clusters of NCAM and spectrin localized along neurites and growth cones. After Triton X-100 extraction, 93.9 ± 0.615% of the total spectrin immunofluorescence was detected in detergent-insoluble clusters of NCAM (n = 9 neurons, 66 neurites). Conversely, the overall NCAM pattern was largely distinct from the microtubule and microfilament distributions (Fig. S1). When microtubules or microfilaments were disrupted by vincristine or latrunculin B, respectively (and this was confirmed by labeling with tubulin antibodies and Texas red-X phalloidin), NCAM clusters remained detergent insoluble, implying that neither actin nor tubulin was responsible for NCAM's detergent insolubility (unpublished data). Application of the drugs (latrunculin for 24 h, vincristine for 5 h) did not have any visible effect on the morphology of neurons, in accordance with previously published data (Allison et al., 1998, 2000). Depolymerization of microtubules and actin microfilaments did not have any effect on the colocalization of NCAM and spectrin and their association in detergent-insoluble complexes (unpublished data).

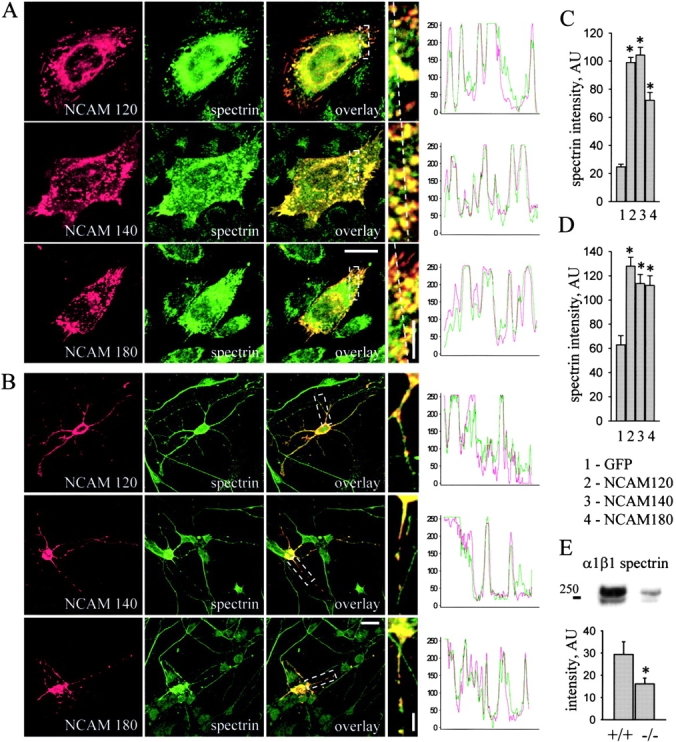

Previous studies have demonstrated an interaction of NCAM180 with spectrin (Pollerberg et al., 1986, 1987). To extend this analysis, CHO cells and hippocampal neurons from an NCAM-deficient mouse were transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that all three NCAM isoforms colocalized with spectrin, both in CHO cells and in neurons (Fig. 1, A and B) . Cells transfected with NCAM (versus GFP alone) also accumulated more spectrin (Fig. 1, C and D). This was also observed in the brains of wild-type versus NCAM-deficient mice (Fig. 1 E). As spectrin is stabilized when incorporated into a detergent-resistant membrane cytoskeleton (Molitoris et al., 1996), we examined the impact of NCAM expression on spectrin's detergent solubility. In CHO cells expressing any of the three major NCAM isoforms, the 0.1% Triton X-100–insoluble fraction was enriched in spectrin, whereas there was no effect on the detergent-soluble fraction (see Fig. S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200303020/DC1). We conclude that all major NCAM isoforms promote spectrin's incorporation into a detergent-insoluble membrane skeleton.

Figure 1.

NCAM120, NCAM140, and NCAM180 colocalize with spectrin and increase its steady-state level. Double immunostaining of (A) CHO cells and (B) hippocampal neurons from NCAM−/− mice transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180 with antibodies against NCAM and spectrin. Note the colocalization of all NCAM isoforms with spectrin. Density profiles of NCAM and spectrin immunofluorescence intensity calculated across CHO cells (dashed lines) or along neurites overlap. Spectrin immunofluorescence intensity relative to nontransfected cells in the same field or to GFP only–transfected cells (n > 30) is significantly higher in NCAM-transfected (C) CHO cells and (D) hippocampal neurons. (E) Levels of spectrin were increased in brain homogenates from wild-type versus NCAM-deficient mice, as assayed by immunoblotting with antibodies against spectrin. Mean values ± SEM from five independent experiments are shown. AU, arbitrary units. *, P < 0.05 (paired t test). Bars: (low power) 20 μm; (high power) 5 μm.

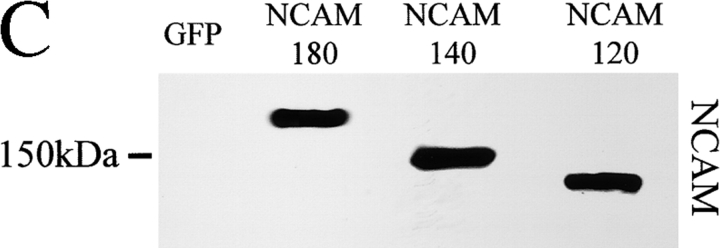

To establish that NCAM could direct the distribution of spectrin in neurons, we used antibodies against all NCAM isoforms to cluster cell surface NCAM in live hippocampal neurons and analyzed the impact on spectrin (Fig. 2 A). Clustering of endogenous NCAM in wild-type neurons was accompanied by coredistribution of spectrin. In neurons from NCAM-deficient mice, the same coredistribution of spectrin was achieved when the neurons were transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180. Moreover, spectrin coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM from brain homogenates, and NCAM180, NCAM140, and NCAM120 coimmunoprecipitated with spectrin (Fig. 2, B and C). NCAM180, NCAM140, or NCAM120 also coimmunoprecipitated with spectrin from transfected CHO cells (Fig. 2, D and E), confirming that the major NCAM isoforms are associated with spectrin in both normal brain and transfected cells. In these studies, NCAM180 was the most potent isoform precipitating spectrin. NCAM140 and NCAM120 precipitated 69.77 ± 4.85 and 74.6 ± 8.19%, respectively, of the amount of spectrin that coprecipitated with NCAM180 (set to 100%) under comparable conditions in three independent experiments.

Figure 2.

NCAM180, NCAM140, and NCAM120 form complexes with spectrin. (A) Hippocampal neurons from wild-type mice or NCAM−/− mice transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180 were incubated with NCAM antibodies to induce surface clustering. Note the overlap of NCAM clusters with spectrin. Bars: (low power) 30 μm; (high power) 5 μm. (B) Brain homogenate from wild-type (+/+) or NCAM-deficient (−/−) mice immunoprecipitated with NCAM antibodies and assayed for spectrin by immunoblotting. (C) Brain homogenate from wild-type or NCAM−/− mice immunoprecipitated with spectrin antibodies and assayed for NCAM by immunoblotting. (D) Lysates of CHO cells transfected with GFP, NCAM180, NCAM140, or NCAM120 and assayed for NCAM by immunoblotting. (E) Lysates of transfected CHO cells immunoprecipitated with NCAM antibodies (NCAM) or rabbit IgG (Ig) and assayed for spectrin by immunoblotting. Note the coprecipitation of spectrin with each of the NCAM isoforms.

NCAM180 and NCAM140 directly interact with the NH2-terminal region of βI spectrin

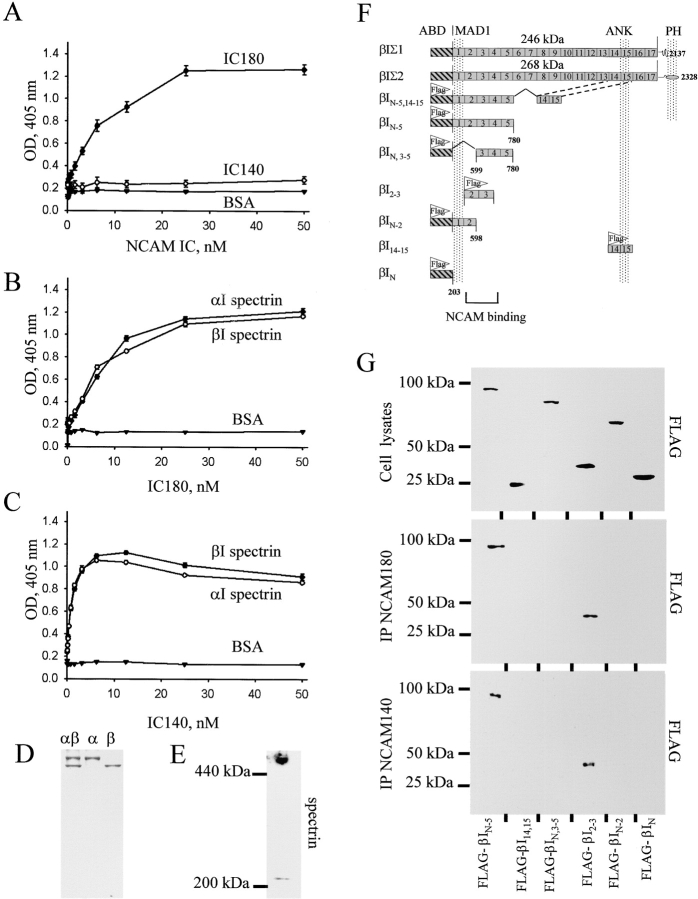

To investigate whether the interaction of NCAM with spectrin was direct, the intracellular domains of NCAM180 (IC180) and NCAM140 (IC140) were immobilized on plastic, and their ability to capture purified erythrocyte spectrin (αIβI) was measured by semiquantitative assay. Interestingly, the intact spectrin dimer bound selectively to IC180, but not IC140 (Fig. 3 A). However, when the subunits of the erythrocyte spectrin heterodimer were dissociated, both the αI and βI chains bound not only IC180, but also IC140 (Fig. 3, B and C). There was no binding of either subunit to BSA or to the intracellular domains of a different cell adhesion molecule, a close homologue of L1 (CHL1) (unpublished data). To verify whether binding of IC180 and IC140 to βI spectrin monomers was physiologically relevant, we analyzed the oligomeric state of βI spectrin bound to brain membranes, using Western blotting of membrane fractions after PAGE under nondenaturing conditions (Fig. 3 E). Two immunoreactive spectrin bands were evident: a complex of ∼520 kD, presumably representing spectrin heterodimers and possibly βI spectrin homodimers (Bloch and Morrow, 1989), and more importantly, a single band at ∼240 kD, representing βI spectrin monomers. This membrane-bound βI spectrin monomeric pool amounted to ∼13% of the total membrane-associated spectrin.

Figure 3.

The intracellular (IC) domains of NCAM180 and NCAM140 interact with the NH2-terminal region of spectrin. (A–C) Increasing concentrations of the IC domain of NCAM180 or NCAM140 were bound to plastic and assayed by ELISA for their ability to bind heterodimeric human erythrocyte spectrin (αIβI) or isolated αI and βI spectrin subunits. Binding to BSA served as a control. Mean values ± SEM from six independent experiments are shown. Note that heterodimeric spectrin bound well to IC180, whereas the isolated subunits bound to both IC180 and IC140. (D) Coomassie blue staining of the purified αIβI dimers and the isolated αI and βI spectrin subunits. (E) Isolated brain membranes assayed for βI spectrin by immunoblotting after PAGE under nondenaturing conditions. Note the low molecular weight band representing βI spectrin monomers. (F) Schematic alignment of βI spectrin fragments. For comparison, the βIΣ1 and βIΣ2 isoforms of βI spectrin are shown. These differ by alternative mRNA splicing at their COOH terminus, which contains the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. ABD, actin-binding domain; MAD1, membrane association domain 1; ANK, ankyrin-binding domain. (G) Lysates of CHO cells transfected with NCAM180 or NCAM140 together with FLAG-labeled spectrin fragments were immunoblotted with FLAG antibodies to confirm approximately equal expression of each of the constructs (top). Lysates from NCAM180 (middle)– and NCAM140 (bottom)–transfected cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with NCAM antibodies and immunoblotted with FLAG antibodies to detect which of the spectrin constructs would precipitate. Note that only βIN-5 and βI2–3 are present in the NCAM precipitates.

The NH2 terminus of βI spectrin contains sequences highly homologous to spectrin repeats located at the COOH terminus of the αI subunit. This region also exhibits homology with α-actinin (Byers et al., 1989; Winkelmann et al., 1990). Thus, although the binding to the isolated αI spectrin was not likely to be biologically meaningful, given the paucity of αI transcripts in either epithelial cells or neurons, the fact that this subunit could bind suggested that the biologically important ligand site might reside within homologous sequences in the NH2-terminal repeats of βI spectrin. To verify that NCAM bound in a biologically significant way to this region of βI spectrin, a series of spectrin truncation mutants were expressed in hippocampal neurons and in CHO cells. Neurons transfected with a GFP fusion construct encoding the NH2-terminal region of βI spectrin and its first five repeat units (GFP–βIN-5) demonstrated tight colocalization of NCAM with the GFP-labeled fragment (see Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200303020/DC1), indicating that the βIN-5 fragment bound the NCAM complex in vivo. This was confirmed when βIN-5 was coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM in CHO cells after they were cotransfected with FLAG epitope–labeled βIN-5 (FLAG–βIN-5) and either NCAM140 or NCAM180 (Fig. 3 G). A larger spectrin fragment containing βIN-5 fused to the ankyrin-binding region (repeats 14–15, βIN-5,14,15) also coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140 and NCAM180 (unpublished data). Spectrin βI fragments encompassing repeats 1–2, 3–5, or 14–15 alone, or the actin- and dynactin-binding domain alone within the NH2 terminus, did not precipitate with NCAM (Fig. 3 G), whereas the βI spectrin fragment containing 2–3 spectrin repeats coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140 and NCAM180. We conclude that the 2–3 homologous repeat units of βI spectrin are necessary and sufficient to bind to the intracellular domains of NCAM140 and NCAM180 in living cells.

Lipid rafts are necessary for the interaction of NCAM120 with βI spectrin

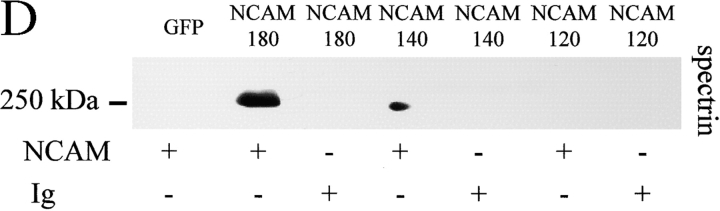

GPI-anchored NCAM120 is confined mainly to lipid rafts that are insoluble in cold 1% Triton (Kramer et al., 1999; He and Meiri, 2002). The coincidence of spectrin with NCAM120 (Fig. 1) suggested that spectrin also associates with lipid rafts, as it does in erythrocytes (Salzer and Prohaska, 2001). CHO cells and NCAM−/− neurons were thus transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180 and treated with 5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MCD), which disintegrates lipid rafts. The relationship of spectrin to NCAM was then examined by immunofluorescence and coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 4) . MCD did not disturb the plasma membrane association of spectrin with NCAM140 or NCAM180. After MCD treatment, NCAM140 precipitated 74 ± 7.32% (n = 3) of the amount of spectrin that coprecipitated with NCAM180 (set to 100%). This level was similar to the amount precipitated in cells not treated with MCD. In contrast, when rafts were dispersed by MCD, the association of NCAM120 with spectrin was lost. In NCAM120-transfected CHO cells treated with MCD, the spectrin distribution internalized and shifted to a more perinuclear appearance (Fig. 4 A), presumably reflecting its association with intracellular organelles (De Matteis and Morrow, 2001). We conclude that NCAM120 interacts indirectly with spectrin through lipid rafts.

Figure 4.

NCAM120 interacts with spectrin through rafts. Double immunostaining of (A) CHO cells and (B) hippocampal neurons from NCAM−/− mice transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180 with antibodies against NCAM and spectrin after treatment with MCD. Note that MCD disrupts the association of spectrin with NCAM120, but not with NCAM140 or NCAM180. Bars: (low power) 10 μm; (high power) 5 μm. (C) Immunoblots of lysates from transfected CHO cells reveal comparable NCAM isoform expression. GFP-transfected cells do not express NCAM. (D) Lysates from NCAM-transfected CHO cells were precipitated with NCAM antibodies (NCAM) or rabbit IgG (Ig) and assayed for spectrin by immunoblotting. Note that MCD treatment prevents the precipitation of spectrin with NCAM120, but not with NCAM140 or NCAM180.

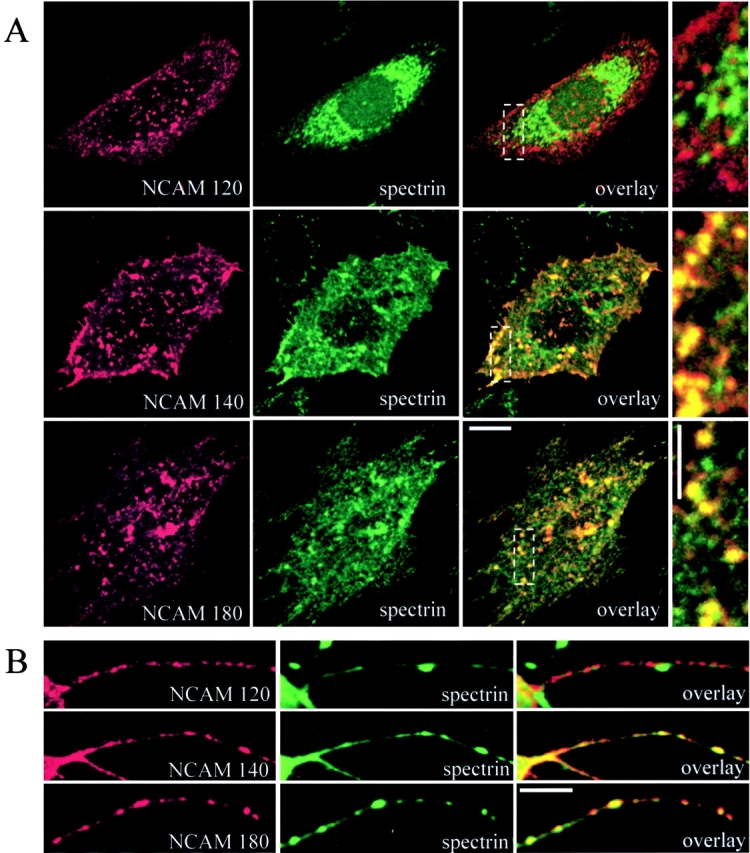

NCAM120 promotes association of spectrin exclusively with rafts, whereas NCAM140 and NCAM180 recruit spectrin both to rafts and nonraft areas

Whereas GPI-anchored NCAM120 is present mainly in lipid rafts, NCAM140 and NCAM180 segregate to both rafts and raft-free areas of the plasma membrane (Niethammer et al., 2002). To investigate whether NCAM can direct the association of spectrin with lipid rafts, CHO cells and NCAM−/− neurons were transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180 and extracted with cold 1% Triton X-100. After this treatment of CHO cells, NCAM120 was detectable in coarse dispersed clusters, whereas NCAM140 and NCAM180 remained in distinct clusters (Fig. 5 A). Spectrin colocalized with all of these detergent-insoluble clusters (Fig. 5 A). The same was observed in neurons (Fig. 5, B and E). To confirm that NCAM120 promoted the association of spectrin exclusively with lipid rafts, whereas NCAM180 and NCAM140 collected spectrin in both rafts and raft-free areas, we labeled detergent-treated neurons with fluorescein-conjugated cholera toxin B subunit, which marks GM1-rich areas. All NCAM120–spectrin complexes colocalized with GM1-positive areas (Fig. 5, B–E). Conversely, only a subset of the clusters containing spectrin and NCAM140 or NCAM180 colocalized with GM1 (Fig. 5, B–E). In astrocytes present in our cultures, NCAM120, the predominant isoform expressed in glial cells (Bhat and Silberberg, 1986), colocalized with spectrin, and NCAM120 expressed in NCAM−/− astrocytes also colocalized with spectrin. Both NCAM120 and spectrin formed detergent-insoluble clusters that colocalized with GM1 (unpublished data), suggesting an association between NCAM120 and spectrin, albeit indirect, in glial cells.

Figure 5.

Complexes containing NCAM120 and spectrin occur predominantly within rafts, whereas complexes with NCAM140 or NCAM180 and spectrin are present both within and outside of rafts. (A) Double immunostaining for NCAM and spectrin in CHO cells transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180 and extracted with 1% Triton X-100. Note the coincidence of spectrin with detergent-insoluble NCAM clusters. Bars: (low power) 20 μm; (high power) 5 μm. (B) Triple labeling for NCAM, spectrin, and GM1 in neurons from NCAM−/− mice transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180 and extracted with 1% Triton X-100. Note that complexes of NCAM120 and spectrin overlap with ganglioside GM1, whereas NCAM140 and NCAM180 clusters overlap with spectrin clusters in both GM1-positive and GM1-free areas. Bar, 10 μm. (C–E) NCAM-positive clusters in transfected neurons were outlined, and mean fluorescence intensities of NCAM (C), GM1 (D), and spectrin (E) were measured within the outlines. NCAM-negative GM1 clusters from NCAM140- and NCAM180-transfected neurons were taken as a reference value (C–E, 4). Note that all NCAM isoforms are associated with GM1-positive areas (D, compare 4 with 3, showing that NCAM120 localizes predominantly to GM1-positive rafts; also compare 4 with 1 and 2, showing that some NCAM180 and NCAM140 localizes to GM1-positive rafts). Spectrin is enriched in NCAM clusters (E). AU, arbitrary units. Mean values ± SEM are shown (n > 100). *, P < 0.05 (paired t test).

NCAM140 and NCAM180 form a complex with PKCβ2

The pleckstrin homology domain of βIΣ2 spectrin interacts with activated PKCβ2 (Rodriguez et al., 1999). To investigate whether spectrin may link PKCβ2 to NCAM, the distribution of these proteins was examined in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 6 A). NCAM colocalized with PKCβ2 along neurites and in growth cones, where clusters of NCAM overlapped with intensely labeled accumulations of PKCβ2. Similar results were also obtained with CHO cells and NCAM−/− neurons transfected with NCAM120, NCAM140, or NCAM180 (unpublished data). Clustering of NCAM by the application of antibodies to all NCAM isoforms to live neurons redistributed PKCβ2 to NCAM clusters (Fig. 6 A). When neurons were extracted with 1% Triton X-100, 74.6 ± 1.3% (n = 11 neurons, 84 neurites) of the total PKCβ2 immunofluorescence remained associated with NCAM clusters, confirming their coassociation in a detergent-insoluble complex (Fig. 6 A). Moreover, PKCβ2 was coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM from mouse brain homogenates (Fig. 6 B). When precipitation was performed with antibodies against PKCβ2, only NCAM140 and NCAM180 were coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 6 C). Also in CHO cells, PKCβ2 coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM140 and NCAM180. NCAM140 precipitated 58.7 ± 8.92% (n = 3) of the amount of PKCβ2 that coprecipitated with NCAM180. PKCβ2 did not coimmunoprecipitate with NCAM120 (Fig. 6 D). Given that spectrin and NCAM120 do coprecipitate (Fig. 2), the lack of PKCβ2 in the spectrin–NCAM120 raft complex suggested that there may be competing interactions that can favor the release of activated PCKβ2 from spectrin.

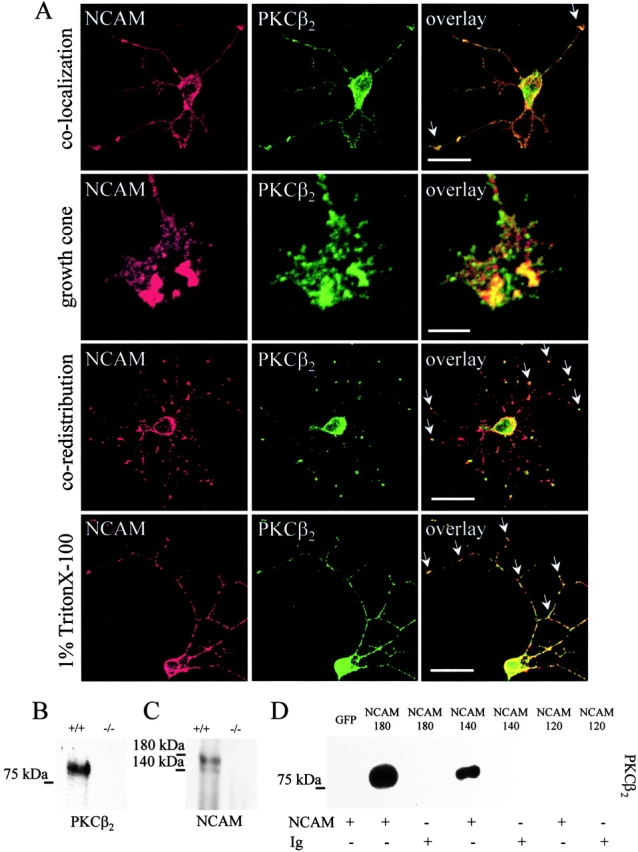

Figure 6.

NCAM and PKCβ2 are colocalized in detergent-insoluble clusters in neurons. (A) Hippocampal neurons stained with antibodies to NCAM and PKCβ2. Clusters of NCAM colocalize with accumulations of PKCβ2 along neurites and in growth cones (colocalization, arrows). In growth cones, NCAM clusters overlap with PKCβ2 accumulations (growth cone). Clustering of NCAM by antibodies induce coredistribution of PKCβ2 with NCAM clusters (coredistribution, arrows). In neurons extracted with detergent (1% Triton X-100), clusters of NCAM overlap with detergent-insoluble PKCβ2 (arrows). Bars: (rows 1, 3, and 4) 20 μm; (row 2) 10 μm. (B) Brain homogenates from wild-type (+/+) or NCAM-deficient (−/−) mice were immunoprecipitated with NCAM antibodies and assayed for PKCβ2 by immunoblotting. (C) Brain homogenate from wild-type (+/+) or NCAM-deficient (−/−) mice immunoprecipitated with PKCβ2 antibodies and assayed for NCAM by immunoblotting with NCAM antibodies. (D) Lysates of CHO cells transfected with NCAM180, NCAM140, or NCAM120 were immunoprecipitated with NCAM antibodies (NCAM) or rabbit IgG (Ig) and probed for PKCβ2 by immunoblotting. Note that PKCβ2 is precipitated with NCAM180 and NCAM140, but not with NCAM120.

NCAM activation promotes the formation of NCAM–spectrin–PKCβ2 complexes and enhances their association with lipid rafts

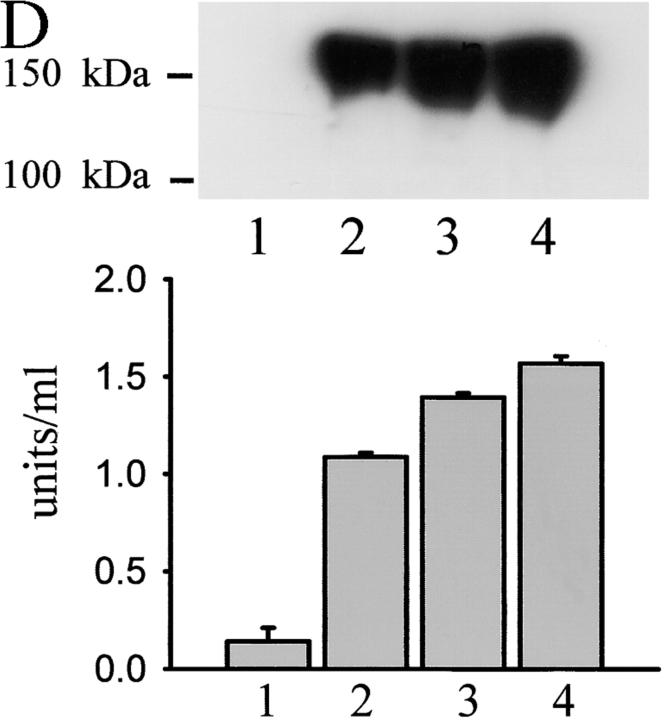

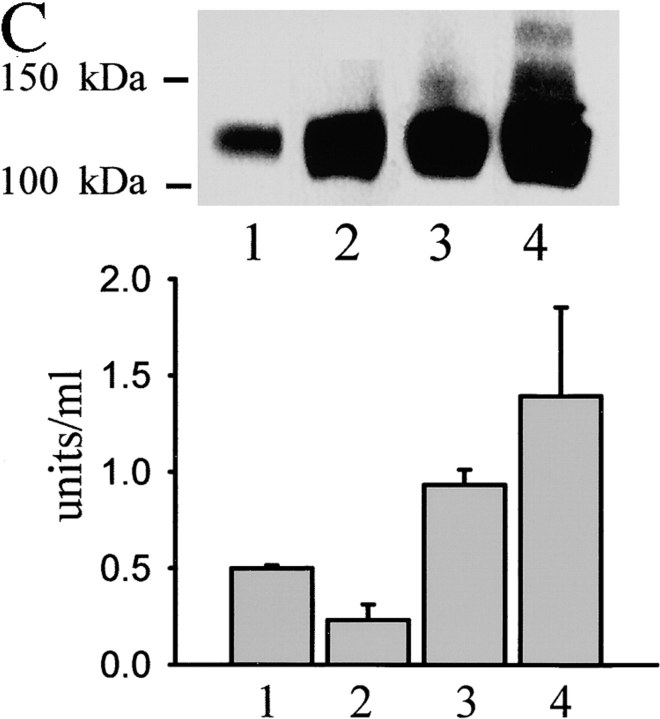

NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth depends on the activation of PKC (Kolkova et al., 2000a) and on the phosphorylation of one of its major substrates, GAP43 (Meiri et al., 1998). The phosphorylated forms of GAP43-like proteins accumulate in lipid rafts (Laux et al., 2000; He and Meiri, 2002), where they reorganize the cytoskeleton (Aarts et al., 1999; Laux et al., 2000). Palmitoylation of NCAM140 and its localization in lipid rafts is critical for NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth (Niethammer et al., 2002). To study the dynamics of NCAM association with spectrin and PKCβ2, we performed a set of experiments aimed to estimate the amount of spectrin and PKCβ2 associated with NCAM at resting conditions and in response to NCAM activation. We also investigated the localization of NCAM–spectrin–PKCβ2 complexes with regard to lipid rafts before and after NCAM activation using GM1 as a raft marker. Activation of NCAM with NCAM-Fc or antibodies against NCAM resulted in a recruitment of βI spectrin to NCAM140/NCAM180 and the formation of 1% Triton X-100–insoluble complexes (Fig. 7, A and B ; Fig. 8 D). Furthermore, the recruitment of βI spectrin to NCAM clusters correlated with an increase in the amount of PKCβ2 in detergent-insoluble clusters of NCAM (Fig. 7, A and B; Fig. 8 D). Activation of NCAM resulted also in an increase of GM1 fluorescence intensity associated with NCAM clusters, suggesting that there was a redistribution of NCAM–spectrin–PKCβ2 complexes into lipid rafts (Fig. 7, A and B). The relationship of NCAM140 and NCAM180 to raft-related PKC activity was also examined by fractionating lipid rafts from mouse brains or from isolated growth cones by equilibrium sucrose gradient centrifugation. Fraction 1 contained the low-density lipid rafts, whereas fraction 4 contained the high-density rafts. As described previously (He and Meiri, 2002), the amount of NCAM140/NCAM180 associated with lipid rafts gradually increased from fraction 2 to fraction 4 both in rafts isolated from brain (Fig. 7 C) and from growth cones (Fig. 7 D). All fractions (fractions 1–4) isolated from brain also contained NCAM120 that probably represents glia-associated NCAM (Fig. 7 C). PKC activity correlated in these fractions with the presence of NCAM140 and NCAM180 (Fig. 7, C and D).

Figure 7.

NCAM activation promotes formation of NCAM–spectrin–PKCβ2 complexes and enhances their association with lipid rafts. (A) Triple labeling for NCAM, GM1, and spectrin or PKCβ2 in neurons from wild-type mice extracted with 1% Triton X-100. Note the increase in intensity of spectrin, PKCβ2, and GM1 labeling (arrows) in NCAM clusters after preincubation of cells with NCAM antibodies (30 min) when compared with nonstimulated (control) cells. Images were taken with the same settings. Bar, 10 μm. (B) NCAM clusters were outlined, and mean fluorescence intensities of GM1 and spectrin or PKCβ2 were measured within the outlines for control cells and neurons stimulated with NCAM-Fc or NCAM antibodies. GM1, spectrin, and PKCβ2 are enriched in NCAM clusters after NCAM activation both with NCAM-Fc and NCAM antibodies. Mean values ± SEM are shown (n > 50 neurites). *, P < 0.05 (paired t test). (C and D) Immunoblot of NCAM in four raft fractions isolated by equilibrium sucrose gradient centrifugation from total brain (C) or growth cones (D). Mean values of PKC enzyme activity ± SEM are shown for each fraction derived from six independent experiments. PKC activity correlates with the presence of NCAM140 and NCAM180.

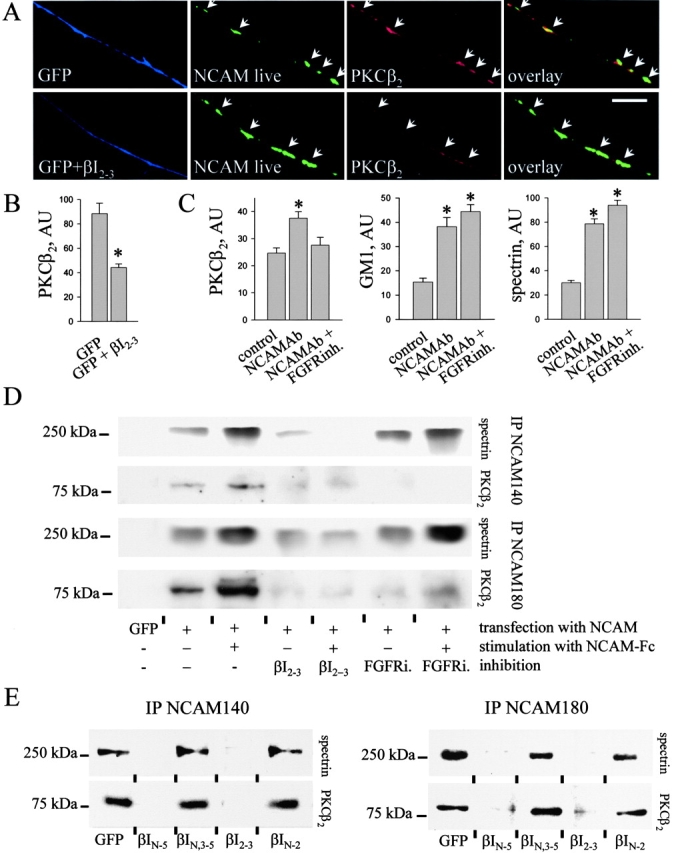

Figure 8.

NCAM140 and NCAM180 bind PKCβ2 via spectrin in an FGFR- dependent manner. (A) Wild-type neurons were transfected either with GFP or GFP together with the βI2–3 construct. NCAM was clustered by application of NCAM antibodies to live cells. Note the reduced redistribution of PKCβ2 to NCAM clusters in neurons cotransfected with βI2–3. Bar, 10 μm. NCAM clusters were outlined, and the level of PKCβ2 immunoreactivity was measured within the outlines (B). Mean values ± SEM are shown (n > 20 neurites). (C) Hippocampal neurons were incubated with NCAM antibodies or NCAM antibodies plus the FGFR inhibitor (PD173074, 50 nM), extracted with 1% Triton X-100, and triple labeled for NCAM, GM1, PKCβ2, or spectrin. NCAM clusters were outlined, and the mean fluorescence intensities of GM1 and PKCβ2 or spectrin were measured within the outlines for control cells and neurons stimulated with NCAM antibodies with or without the inhibitor. The FGFR inhibitor blocked redistribution of PKCβ2 to NCAM clusters but not recruitment of spectrin to NCAM and redistribution of the NCAM–spectrin complex to lipid rafts. Mean values ± SEM are shown (n > 50 neurites). *, P < 0.05 (paired t test). (D) CHO cells transfected with GFP, NCAM140, NCAM180, NCAM140 + βI2–3, or NCAM180 + βI2–3 were incubated with NCAM-Fc or NCAM-Fc plus the FGFR inhibitor. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with NCAM antibodies and probed for spectrin and PKCβ2 by immunoblotting. Fragment βI2–3 interferes with the precipitation of spectrin and PKCβ2, whereas the FGFR inhibitor blocks only precipitation of PKCβ2. Note the increased amount of spectrin and PKCβ2 precipitating with NCAM after NCAM activation. (E) Lysates of CHO cells cotransfected with NCAM140 or NCAM180 with GFP, βIN-5, βIN,3–5, βI2–3, or βIN-2 were immunoprecipitated with NCAM antibodies and probed for spectrin and PKCβ2 by immunoblotting. Note that only fragments βIN-5 and βI2–3 interfere with the precipitation of spectrin and PKCβ2.

NCAM140 and NCAM180 bind PKCβ2 via spectrin in an FGFR–dependent manner

To verify whether spectrin is indeed a linker protein between NCAM and PKCβ2, we transfected neurons with the βI2–3 construct that deletes spectrin's pleckstrin homology domain, the binding site for PKCβ2, but retains the NCAM-binding site. The redistribution of PKCβ2 to NCAM clusters induced by the application of NCAM antibodies to live cells was significantly inhibited in cells transfected with the βI2–3 construct when compared with GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 8, A and B). In CHO cells cotransfected with βIN-5 or βI2–3 constructs, coprecipitation of endogenous spectrin and PKCβ2 with NCAM180 or NCAM140 was also blocked both at resting conditions and in response to NCAM activation (Fig. 8, D and E). Conversely, spectrin mutants, βIN-2 and βIN,3–5, that did not bind IC140 or IC180 did not disturb coprecipitation (Fig. 8 E). We conclude that PKCβ2 is associated indirectly with NCAM140 or NCAM180 via its interaction with spectrin.

NCAM-mediated activation of PKC occurs via the FGFR (Kolkova et al., 2000a). Inhibition of the FGFR with the specific inhibitor PD173074 blocked redistribution of PKCβ2 to detergent-insoluble NCAM clusters in response to NCAM activation (Fig. 8 C). It also significantly inhibited coprecipitation of PKCβ2 with NCAM140/NCAM180 from CHO cells (Fig. 8 D). By contrast, inhibition of the FGFR did not affect the ability of NCAM to recruit spectrin and redistribute to lipid rafts (Fig. 8, C and D).

Formation of a complex between PKCβ2, spectrin, and NCAM is implicated in NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth

To investigate whether the association of PKCβ2 with NCAM140 and NCAM180 was functionally important for NCAM-mediated outgrowth, we compared neurite length in hippocampal neurons from wild -type mice cotransfected with GFP and βIN-5 or βI2–3 with neurons transfected with GFP alone. Labeling of neurons transfected with GFP–βIN-5 by NCAM antibodies under nonpermeabilizing conditions confirmed that βIN-5 did not disturb delivery of NCAM to the plasma membrane (Fig. S3, A). In βIN-5-transfected neurons, NCAM was distributed along neurites and accumulated in growth cones in a manner similar to nontransfected cells. GFP–βIN-5 colocalized with NCAM and also accumulated in growth cones. When grown on a poly-l-lysine substrate, GFP- or GFP + βIN-5–transfected neurons extended neurites equally well. Stimulation with soluble NCAM-Fc led to a significant increase in the neurite lengths of the GFP-transfected neurons, whereas the GFP + βIN-5– or GFP + βI2–3 –transfected neurons were unresponsive (Fig. S3, B). Conversely, neurite outgrowth in response to NCAM-Fc stimulation in neurons transfected with spectrin βIN-2 or βIN,3–5 was not inhibited, suggesting that the βIN-5 and βI2–3 effect is due to the disruption of the NCAM–βI spectrin–PKCβ2 complex. We also compared NCAM-Fc– and L1-Fc–mediated neurite outgrowth from neurons transfected with the βI2–3 spectrin construct. L1-mediated neurite outgrowth depends on the activation of pp60c-src, p21rac, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, which differs from the NCAM-mediated signal transduction cascade (Ignelzi et al., 1994; Beggs et al., 1997; Schmid et al., 2000). Transfection with βI2–3 did not inhibit L1-mediated neurite outgrowth (Fig. S3, B). We conclude that the association of PKCβ2 with NCAM140 and NCAM180 via spectrin is implicated in NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth.

Discussion

The results presented here establish a direct structural and functional linkage between βI spectrin (hereafter called spectrin) and NCAM180 and NCAM140. This linkage mediates the localized assembly of spectrin microdomains at points of NCAM concentration, the recruitment of activated PKCβ2 to these patches, and the subsequent translocation of activated PKCβ2 to detergent-insoluble lipid rafts. Spectrin-mediated coordination between NCAM and PKCβ2 is required to trigger NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth in cultured neurons. Several lines of data support these conclusions. Specifically, (a) NCAM180 and NCAM140 are colocalized with spectrin and PKCβ2 in detergent-insoluble clusters in cultured hippocampal neurons and in CHO cells; (b) patching and capping of NCAM by antibodies induces a coincident redistribution of spectrin and PKCβ2; (c) NCAM antibodies coprecipitate NCAM180 and NCAM140 with spectrin and PKCβ2 and vice versa; (d) the recombinant intracellular domains of NCAM180 and NCAM140 bind to spectrin; (e) the steady-state levels of spectrin are up-regulated in cells expressing NCAM and down-regulated in NCAM-deficient mouse brains; and (f) the spectrin fragments βIN-5 and βI2–3 coprecipitate with NCAM180 and NCAM140, but block the recruitment of PKCβ2 to NCAM clusters at the cell surface, and suppress NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth. Collectively, these findings suggest that spectrin participates in a complex interplay between NCAM organization, the activation of PKCβ2, and the control of neurite outgrowth.

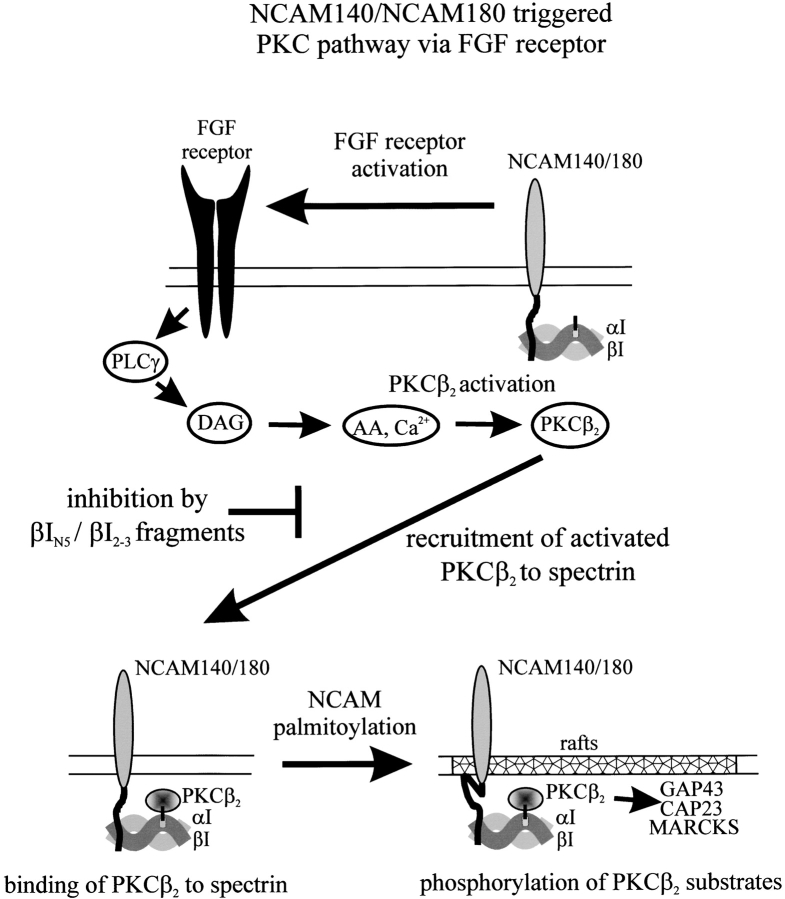

We have previously shown that FGFR activation in nonraft membrane domains, followed by the recruitment of NCAM140 to lipid rafts via palmitoylation, is necessary for neurite outgrowth (Niethammer et al., 2002). The present results establish that the spectrin-mediated recruitment of activated PKCβ2 to lipid rafts is also a step along this pathway. Our concept of how this process works is presented in Fig. 9 . Earlier work has established that PKC can be activated by diacylglycerol (Inoue et al., 1977; Kishimoto et al., 1980) via the FGFR (Walsh and Doherty, 1997; Kolkova et al., 2000a). We envision that the NCAM-mediated activation of the FGFR occurs independently of lipid rafts and induces the formation of a spectrin microdomain enriched in activated PKCβ2 that binds to spectrin's pleckstrin homology domain. Subsequent palmitoylation of NCAM140 transfers the NCAM–spectrin–PKCβ2 complex to a lipid raft. It is also possible that direct palmitoylation of spectrin may contribute to this process (Das et al., 1997). Once in the lipid raft, the NCAM–spectrin–PKCβ2 complex encounters growth-associated and cytoskeletal control molecules that include GAP43, CAP23, and MARCKS (Laux et al., 2000; He and Meiri, 2002). These proteins, recruited to lipid rafts via myristolylation, are major substrates of PKC, and at least GAP43 is required for NCAM-stimulated neurite outgrowth (Meiri et al., 1998). Thus, the recruitment of the NCAM–spectrin–PKCβ2 complex to lipid rafts may initiate the activation of downstream cytoskeletal organizers that contribute to neurite outgrowth.

Figure 9.

Proposed model of NCAM–spectrin–PKC interactions in the NCAM-triggered PKC pathway. See text in Discussion.

We have also shown that both NCAM140 and NCAM180 can each form a signaling complex with PKCβ2 via spectrin. These data are in agreement with our previous finding that both NCAM140 and NCAM180 can signal via the FGFR–PKC pathway (Niethammer et al., 2002). NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth depends on the activation of two signaling pathways. One pathway includes activation of PKC, whereas the other requires activation of fyn and FAK kinases (Beggs et al., 1997; Kolkova et al., 2000a). NCAM140, but not NCAM180, can signal independently of the FGFR by activating fyn/FAK kinases. Due to conformational constraints in NCAM180, its interaction with fyn is prevented (Beggs et al., 1997; Kolkova et al., 2000b; Niethammer et al., 2002). Thus, because NCAM140 can activate both signaling pathways, it alone is sufficient to stimulate NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth when expressed in NCAM−/− neurons (Niethammer et al., 2002). NCAM180, on the other hand, would then be more instrumental in the accumulation of spectrin–PKCβ2 complexes at sites of cell contacts, as proposed previously (Pollerberg et al., 1986, 1987) and indicated by the localization of NCAM180 and spectrin, for instance, in postsynaptic densities (Persohn et al., 1989; Malchiodi-Albedi et al., 1993; Schuster et al., 1998). However, preliminary evidence suggests that in hippocampal neurons expressing both NCAM140 and NCAM180, NCAM180 may amplify NCAM140-mediated activation of the FGFR–PKC pathway, and thus participate in NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth (unpublished data).

It is interesting, in this respect, that NCAM180 coimmunoprecipitates spectrin with higher efficiency than NCAM140 or NCAM120. This phenomenon could account for our previous observation that NCAM180, but not NCAM140, coisolated with the spectrin by immunoaffinity chromatography (Pollerberg et al., 1986, 1987, note the purification procedure for NCAM140 and NCAM120 in these studies, which consisted of consecutive isolation of NCAM180 from the immunoaffinity-purified L1 fraction and of NCAM140 and NCAM120 from the residual fraction, thus possibly accounting for a depletion of spectrin in the latter fraction). The ability of spectrin to bind as the αβ heterodimer to the recombinant intracellular domains of NCAM180, but not of NCAM140, has been noted previously (Pollerberg et al., 1986, 1987). We attribute little significance to the in vitro binding of the isolated αI spectrin subunit, as this isoform of spectrin is either nonexistent or present at extremely low levels in either neurons or epithelial cells. However, both heterodimeric, and to a lesser extent homopolymeric, βI spectrins exist in neurons and in other cells, often as specialized membrane complexes, such as with the secretory pathway, at the postsynaptic density, or with lymphocyte receptors (Bloch and Morrow, 1989; De Matteis and Morrow, 2000). As demonstrated here, ∼13% of the total membrane-bound βI spectrin exists in a monomeric state. We thus believe that βI spectrin could play a role in the control of NCAM-mediated signaling.

The question arises how NCAM120, the GPI-linked isoform of NCAM, associates with spectrin. It cannot do so directly, as it lacks an intracellular domain, yet it colocalizes and coimmunoprecipitates with spectrin in both neurons and in transfected CHO cells. Both NCAM120 and spectrin associate with lipid rafts, and this association is disturbed by the dispersal of rafts after treatment with MCD. We infer that a direct association with acidic lipids, possibly in rafts, may be mediated by spectrin's pleckstrin homology domain, as detected in other studies (for reviews see De Matteis and Morrow, 2000; Muresan et al., 2001). As PKCβ2 binds to the pleckstrin homology domain and as this domain is occupied by acidic lipids in rafts, the lack of this kinase in the NCAM120 immunoprecipitates can be accounted for. The functional role of spectrin's association with NCAM120 is interesting in view of its predominant expression by astrocytes. NCAM120 is involved in signal pathways regulating astrocyte proliferation via glucocorticoid receptors (Krushel et al., 1998). These pathways are different from the signals regulating neurite outgrowth in neurons (Krushel et al., 1998). The intracellular glucocorticoid receptor binds to the heat shock protein and chaperone hsp70 (Morishima et al., 2000), which in turn binds to spectrin (Di et al., 1995). Whether spectrin also provides a platform for glucocorticoid receptors and whether NCAM120 modulates this interaction are intriguing issues for further studies.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and toxins

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against NCAM (Martini and Schachner, 1986) were used in immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and immunocytochemical experiments, and rat monoclonal antibodies H28 against mouse NCAM (Gennarini et al., 1984) were used in immunocytochemical experiments. Both antibodies react with the three major isoforms of NCAM. Mouse monoclonal antibodies 5B8 against the NCAM140 and NCAM180 intracellular domains (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) were also used for immunocytochemical experiments. The hybridoma H28 clone was obtained from Christo Goridis (Developmental Biology Institute of Marseille, Marseille, France). We also used polyclonal rabbit antibodies against human erythrocyte spectrin and mouse monoclonal antibodies against PKCβ2, tubulin, and FLAG epitope (Sigma-Aldrich). Secondary antibodies against rabbit, rat, and mouse Ig coupled to Cy2, Cy3, or Cy5 were from Dianova. Cholera toxin B subunit labeled with fluorescein and vincristine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, latrunculin B was from Calbiochem, and Texas red-X phalloidin was from Molecular Probes.

Cultures and transfection of hippocampal neurons and CHO cells

Cultures of hippocampal neurons were prepared from 1–3-d-old C57BL/6J mice or from NCAM-deficient (NCAM−/−) mice (Cremer et al., 1994) inbred for at least nine generations onto the C57BL/6J background. Neurons were grown in 10% horse serum on glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (100 μg/ml) in conjunction with laminin (20 μg/ml) (Dityatev et al., 2000). Transfection of hippocampal neurons and neurite outgrowth quantification were performed as previously described (Niethammer et al., 2002). CHO cells were maintained in Glasgow modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instruction.

Fluorescence labeling

Indirect immunofluorescence staining of fixed cells was performed as previously described (Dityatev et al., 2000). Clustering of NCAM was induced by incubating live cells for 15 min (5% CO2 at 37°C) with NCAM antibodies, visualized with secondary antibodies applied for 5 min. To visualize cholesterol-enriched microdomains, fluorescein-conjugated cholera toxin B subunit (8 μg/ml) was applied to formaldehyde-fixed cells for 30 min at room temperature. Images were acquired using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.).

Colocalization analysis

For colocalization analysis, we defined an NCAM cluster as an accumulation of NCAM labeling with a mean intensity at least 30% higher than background. NCAM clusters were automatically outlined using the threshold function of the Scion Image software. Within the outlined areas, the mean intensities of NCAM, spectrin, PKCβ2, and GM1 labeling associated with an NCAM cluster were measured. The same threshold was used for all groups. In nontransfected neurons, GM1 clusters were outlined using the same procedure. To determine the total amount of spectrin or PKCβ2, neurites were manually outlined, and the total fluorescence of spectrin or PKCβ2 along the neurites was measured. Colocalization profiles were plotted using LSM510 software.

Detergent extraction, cholesterol depletion, and cytoskeleton disruption

Detergent extraction followed Ledesma et al. (1998). Cells washed in PBS, pH 7.3, were incubated for 1 min in cold microtubule-stabilizing buffer (MSB; 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA, 60 mM Pipes, pH 7.0) and extracted 8 min on ice with 1% Triton X-100 in MSB. After washing, cells were fixed with cold 4% formaldehyde. To deplete cholesterol from lipid rafts, cultures were incubated for 15 min at 37°C with 5 mM MCD (Sigma-Aldrich) in culture medium. To disrupt microtubules, cell cultures were incubated with vincristine (5 μM) for 5 h before fixation (Allison et al., 2000). For disruption of actin filaments, cultures were incubated in 5 μM latrunculin B for 24 h before fixation (Allison et al., 1998).

Protein purification

The αIβI spectrin dimers were purified from erythrocyte ghosts (Shotton, 1998). Cells were washed three times in 15 volumes of 155 mM NaCl and then three times in 15 volumes of 155 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.6. Erythrocytes were lysed for 20 min in 15 volumes of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.6. Erythrocyte ghosts were collected by centrifugation at 30,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, washed in ice-cold extraction buffer (1 mM EDTA, 10 μM DTT, pH 9.5), sonicated for 30 s, incubated for 60 min at 37°C with occasional mixing, and centrifuged at 230,000 g for 60 min at 4°C. The supernatant containing αIβI spectrin dimers and actin was further purified by gel filtration chromatography on Sepharose 4B in 1 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0, containing 100 μM EDTA, 10 μM DTT, and 0.02% NaN3.

The isolated spectrin αI and βI subunits of spectrin were purified according to Davis and Bennett (1983). The αIβI spectrin dimers were dialyzed against 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.3, containing 7 M urea, 10 mM glycine, 0.05% Tween 20, 1 mM DTT, and applied to a hydroxylapatite column (Sigma-Aldrich). αI subunit of spectrin was eluted by 80 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.3, containing 7 M urea, 10 mM glycine, 0.05% Tween 20, and 1 mM DTT. βI spectrin was eluted by 250 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.1, containing 7 M urea, 10 mM glycine, 0.05% Tween 20, and 1 mM DTT. Subunits were dialyzed against the 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 1 M NaBr, 6 M urea, 10 mM glycine, 0.05% Tween 20, 1 mM DTT, with subsequent dialysis against the same buffer without urea. Aggregated complexes of βI spectrin were removed by gel filtration on Sepharose 4B.

DNA constructs

Rat NCAM140 and rat NCAM180/pcDNA3 were a gift of Patricia Maness (University of North Carolina, Durham, NC). Rat NCAM120 (gift of Elisabeth Bock, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark) was subcloned into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) by two EcoRI sites. The eGFP plasmid was from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc. Spectrin βI full-length DNA was used as template to produce fragments encoding βI spectrin domains that were cloned in pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) and verified by DNA sequencing (Devarajan et al., 1997; De Matteis and Morrow, 2001).

Production of intracellular domains of NCAM140 and NCAM180

The BamHI sites were introduced at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cDNAs encoding the NCAM140 or NCAM180 intracellular domains and were cloned in frame into the BamHI site of pQE30 (QIAGEN). Proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli strain M15 and purified on Ni-NTA-agarose (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

ELISA protein ligand-binding assay

Intracellular domains of NCAM180 or NCAM140 (IC180 and IC140; 0.025–50 nM) were immobilized overnight on 96-well polyvinyl chloride plates (Nunc) in PBS. Wells were then blocked for 1.5 h with PBS containing 1% BSA and incubated for 1.5 h at RT with αIβI spectrin dimers or αI and βI spectrin subunits diluted in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and 1% BSA. Plates were washed three times with PBS-T and incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature with polyclonal antibodies against human erythrocyte spectrin diluted 1:4,000 in PBS-T containing 1% BSA. After washing with PBS-T, wells were incubated with peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies in PBS-T containing 1% BSA, washed three times, and developed with 0.1% ABTS (Roche Diagnostics) in 100 mM acetate buffer, pH 5.0. The reaction was stopped with 100 mM NaF. The OD was measured at 405 nm.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Transiently transfected CHO cells were washed two times with ice-cold PBS, lysed 30 min on ice with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM Na2P2O7, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM NaVO4, 0.1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail from Roche Diagnostics), and centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 g at 4°C. Supernatants were cleared with protein A/G–agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) (3 h at 4°C) and incubated with NCAM Pab or control Ig (1.5 h, 4°C), followed by precipitation with protein A/G–agarose beads (1 h, 4°C). The beads were washed three times with RIPA buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Detergent fractionation of spectrin from cells

Fractionation of spectrin into 0.1% Triton X-100–soluble and –insoluble material was performed according to Molitoris et al. (1996). In brief, CHO cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, collected with a rubber policeman, solubilized, and extracted for 5 min at 4°C with PHEM buffer (60 mM Pipes, 25 mM Hepes, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.9, containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.1 mM DTT). Cells were then centrifuged for 10 min at 48,000 g at 4°C. Supernatants and pellets were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Subcellular fractionation and isolation of lipid-enriched microdomains

Membrane fractions were isolated from brains of adult mice (Kleene et al., 2001), and rafts were prepared according to Brown and Rose (1992) with modifications. Membranes were lysed on ice for 20 min in four volumes of ice-cold 1% Triton X-100 in TBS and mixed with an equal volume of 80% sucrose in 0.2 M Na2CO3. A 10–30% linear sucrose gradient was layered on top of the lysate and centrifuged for 18 h at 230,000 g at 4°C (SW55 Ti rotor; Beckman Coulter). Raft fractions were collected as previously described (He and Meiri, 2002). Nerve growth cones were isolated as previously described (Pfenninger et al., 1983).

PKC assay and immunoblotting

PKC activity was measured using the PepTag assay for nonradioactive detection according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE (8%) or PAGE (3–6%) (nondenaturing conditions) were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose transfer membrane (PROTRAN; Schleicher & Schuell) for 3 h at 250 mA. Immunoblots were incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies followed by incubation with peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies and visualized using Super Signal West Pico reagents (Pierce Chemical Co.) on BIOMAX film (Sigma-Aldrich). Molecular weight markers were prestained protein standards from Bio-Rad Laboratories.

Online supplemental material

The supplemental material (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200303020/DC1) includes images showing colocalization of NCAM and spectrin in detergent-insoluble clusters in neurons (Fig. S1), Western blots showing NCAM-mediated formation of a detergent-insoluble spectrin cytoskeleton (Fig. S2), and neurite outgrowth data showing the involvement of NCAM association with PKCβ2 via spectrin in NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth (Fig. S3).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Harold Cremer (Developmental Biology Institute of Marseille, Marseille, France) for his gift of NCAM-deficient mice. We are grateful to Achim Dahlmann, Galina Dityateva, and Eva Kronberg for genotyping, cell culture, and animal care, Drs. Ulrich Bormann and Melanie Richter for purification of NCAM-Fc and intracellular domains of CHL1, NCAM140, and NCAM180, and Drs. Patricia Maness and Elisabeth Bock for the gift of NCAM cDNAs. Drs. Carol Cianci and Deepti Pradhan and Mr. Paul Stabach are thanked for their help with this paper and for assistance with the spectrin constructs. We thank Dr. Alexander Dityatev for helpful discussions and suggestions.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (M. Schachner), and Zonta Club Hamburg-Alster (I. Leshchyns'ka) and in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (J.S. Morrow).

I. Leshchyns'ka and V. Sytnyk contributed equally to this work.

The online version of this article includes supplemental material.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; MCD, methyl-β-cyclodextrin; NCAM, neural cell adhesion molecule.

References

- Aarts, L.H., P. Verkade, J.J. van Dalen, A.J. van Rozen, W.H. Gispen, L.H. Schrama, and P. Schotman. 1999. B-50/GAP-43 potentiates cytoskeletal reorganization in raft domains. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 14:85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison, D.W., V.I. Gelfand, I. Spector, and A.M. Craig. 1998. Role of actin in anchoring postsynaptic receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons: differential attachment of NMDA versus AMPA receptors. J. Neurosci. 18:2423–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison, D.W., A.S. Chervin, V.I. Gelfand, and A.M. Craig. 2000. Postsynaptic scaffolds of excitatory and inhibitory synapses in hippocampal neurons: maintenance of core components independent of actin filaments and microtubules. J. Neurosci. 20:4545–4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggs, H.E., S.C. Baragona, J.J. Hemperly, and P.F. Maness. 1997. NCAM140 interacts with the focal adhesion kinase p125(fak) and the SRC-related tyrosine kinase p59(fyn). J. Biol. Chem. 272:8310–8319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, S., and D.H. Silberberg. 1986. Oligodendrocyte cell adhesion molecules are related to neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM). J. Neurosci. 6:3348–3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, V., and A.J. Baines. 2001. Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues. Physiol. Rev. 81:1353–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, R.J., and J.S. Morrow. 1989. An unusual β-spectrin associated with clustered acetylcholine receptors. J. Cell Biol. 108:481–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.A., and J.K. Rose. 1992. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 68:533–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers, T.J., A. Husain-Chishti, R.R. Dubreuil, D. Branton, and L.S. Goldstein. 1989. Protein sequence similarity of the amino-terminal domain of Drosophila β spectrin to α actinin and dystrophin. J. Cell Biol. 109:1633–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, H., R. Lange, A. Christoph, M. Plomann, G. Vopper, J. Roes, R. Brown, S. Baldwin, P. Kraemer, S. Scheff, et al. 1994. Inactivation of the N-CAM gene in mice results in size reduction of the olfactory bulb and deficits in spatial learning. Nature. 367:455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K., B. Dasgupta, R. Bhattacharya, and J. Basu. 1997. Purification and biochemical characterization of a protein-palmitoyl acyltransferase from human erythrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 272:11021–11025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J., and V. Bennett. 1983. Brain spectrin. Isolation of subunits and formation of hybrids with erythrocyte spectrin subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 258:7757–7766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis, M.A., and J.S. Morrow. 2000. Spectrin tethers and mesh in the biosynthetic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 113:2331–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis, M.A., and J.S. Morrow. 2001. ADP ribosylation factor (ARF) as a regulator of spectrin assembly at the Golgi complex. Regulators and Effectors of Small GTPases, part F. Vol. 329. W. Balch, editor. Academic Press, New York. 405–416. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Devarajan, P., P. Stabach, A.M. De Matteis, and J.S. Morrow. 1997. Na, K-ATPase transport from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi requires the Golgi spectrin-ankyrin G119 skeleton in Madin Darby canine kidney cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:10711–10716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di, Y.P., E. Repasky, A. Laszlo, S. Calderwood, and J. Subjeck. 1995. Hsp70 translocates into a cytoplasmic aggregate during lymphocyte activation. J. Cell. Physiol. 165:228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev, A., G. Dityateva, and M. Schachner. 2000. Synaptic strength as a function of post- versus presynaptic expression of the neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM. Neuron. 26:207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields, R.D., and K. Itoh. 1996. Neural cell adhesion molecules in activity-dependent development and synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 19:473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennarini, G., M. Hirn, H. Deagostini-Bazin, and C. Goridis. 1984. Studies on the transmembrane disposition of the neural cell adhesion molecule N-CAM. The use of liposome-inserted radioiodinated N-CAM to study its transbilayer orientation. Eur. J. Biochem. 142:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner, B.M. 2000. Regulation of cadherin adhesive activity. J. Cell Biol. 148:399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Q., and K.F. Meiri. 2002. Isolation and characterization of detergent-resistant microdomains responsive to NCAM-mediated signaling from growth cones. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 19:18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa, N. 1998. Kinesin and dynein superfamily proteins and the mechanism of organelle transport. Science. 279:519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignelzi, M.A., Jr., D.R. Miller, P. Soriano, and P.F. Maness. 1994. Impaired neurite outgrowth of src-minus cerebellar neurons on the cell adhesion molecule L1. Neuron. 12:873–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M., A. Kishimoto, Y. Takai, and Y. Nishizuka. 1977. Studies on a cyclic nucleotide-independent protein kinase and its proenzyme in mammalian tissues. II. Proenzyme and its activation by calcium-dependent protease from rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 252:7610–7616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano, R.L. 2002. Signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors and the cytoskeleton: functions of integrins, cadherins, selectins, and immunoglobulin-superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 42:283–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto, A., Y. Takai, T. Mori, U. Kikkawa, and Y. Nishizuka. 1980. Activation of calcium and phospholipid-dependent protein kinase by diacylglycerol, its possible relation to phosphatidylinositol turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 255:2273–2276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleene, R., H. Yang, M. Kutsche, and M. Schachner. 2001. The neural recognition molecule L1 is a sialic acid-binding lectin for CD24, which induces promotion and inhibition of neurite outgrowth. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21656–21663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolkova, K., V. Novitskaya, N. Pedersen, V. Berezin, and E. Bock. 2000. a. Neural cell adhesion molecule-stimulated neurite outgrowth depends on activation of protein kinase C and the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J. Neurosci. 20:2238–2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolkova, K., N. Pedersen, V. Berezin, and E. Bock. 2000. b. Identification of an amino acid sequence motif in the cytoplasmic domain of the NCAM-140 kDa isoform essential for its neuritogenic activity. J. Neurochem. 75:1274–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, E.M., C. Klein, T. Koch, M. Boytinck, and J. Trotter. 1999. Compartmentation of Fyn kinase with glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored molecules in oligodendrocytes facilitates kinase activation during myelination. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29042–29049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krushel, L.A., M.H. Tai, B.A. Cunningham, G.M. Edelman, and K.L. Crossin. 1998. Neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) domains and intracellular signaling pathways involved in the inhibition of astrocyte proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:2592–2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laux, T., K. Fukami, M. Thelen, T. Golub, D. Frey, and P. Caroni. 2000. GAP43, MARCKS, and CAP23 modulate PI(4,5)P(2) at plasmalemmal rafts, and regulate cell cortex actin dynamics through a common mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 149:1455–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, M.D., K. Simons, and C.G. Dotti. 1998. Neuronal polarity: essential role of protein-lipid complexes in axonal sorting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:3966–3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi-Albedi, F., M. Ceccarini, J.C. Winkelmann, J.S. Morrow, and T.C. Petrucci. 1993. The 270 kDa splice variant of erythrocyte β-spectrin (βIΣ2) segregates in vivo and in vitro to specific domains of cerebellar neurons. J. Cell Sci. 106:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini, R., and M. Schachner. 1986. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of neural cell adhesion molecules (L1, N-CAM, and MAG) and their shared carbohydrate epitope and myelin basic protein in developing sciatic nerve. J. Cell Biol. 103:2439–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiri, K.F., J.L. Saffell, F.S. Walsh, and P. Doherty. 1998. Neurite outgrowth stimulated by neural cell adhesion molecules requires growth-associated protein-43 (GAP-43) function and is associated with GAP-43 phosphorylation in growth cones. J. Neurosci. 18:10429–10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molitoris, B.A., R. Dahl, and M. Hosford. 1996. Cellular ATP depletion induces disruption of the spectrin cytoskeletal network. Am. J. Physiol. 271:F790–F798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima, Y., P.J. Murphy, D.P. Li, E.R. Sanchez, and W.B. Pratt. 2000. Stepwise assembly of a glucocorticoid receptor-hsp90 heterocomplex resolves two sequential ATP-dependent events involving first hsp70 and then hsp90 in opening of the steroid binding pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18054–18060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muresan, V., M.C. Stankewich, W. Steffen, J.S. Morrow, E.L.F. Holzbaur, and B.J. Schnapp. 2001. Dynactin-dependent, dynein-driven vesicle transport in the absence of membrane proteins: a role for spectrin and acidic phospholipids. Mol. Cell. 7:173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer, P., M. Delling, V. Sytnyk, A. Dityatev, K. Fukami, and M. Schachner. 2002. Cosignaling of NCAM via lipid rafts and the FGF receptor is required for neuritogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 157:521–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persohn, E., G.E. Pollerberg, and M. Schachner. 1989. Immunoelectron-microscopic localization of the 180 kD component of the neural cell adhesion molecule N-CAM in postsynaptic membranes. J. Comp. Neurol. 288:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfenninger, K.H., L. Ellis, M.P. Johnson, L.B. Friedman, and S. Somlo. 1983. Nerve growth cones isolated from fetal rat brain: subcellular fractionation and characterization. Cell. 35:573–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollerberg, G.E., M. Schachner, and J. Davoust. 1986. Differentiation state-dependent surface mobilities of two forms of the neural cell adhesion molecule. Nature. 324:462–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollerberg, G.E., K. Burridge, K.E. Krebs, S.R. Goodman, and M. Schachner. 1987. The 180-kD component of the neural cell adhesion molecule N-CAM is involved in a cell-cell contacts and cytoskeleton-membrane interactions. Cell Tissue Res. 250:227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, D., and J. Morrow. 2002. The spectrin-ankyrin skeleton controls CD45 surface display and interleukin-2 production. Immunity. 17:303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, D., C.R. Lombardo, S. Roe, D.L. Rimm, and J.S. Morrow. 2001. α-Catenin binds directly to spectrin and facilitates spectrin-membrane assembly in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 276:4175–4181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm, D.L., E.R. Koslov, P. Kebriaei, C.D. Cianci, and J.S. Morrow. 1995. α1(E)-catenin is a novel actin binding and bundling protein mediating the attachment of F-actin to the membrane adhesion complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:8813–8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M.M., D. Ron, K. Touhara, C.H. Chen, and D. Mochly-Rosen. 1999. RACK1, a protein kinase C anchoring protein, coordinates the binding of activated protein kinase C and select pleckstrin homology domains in vitro. Biochemistry. 38:13787–13794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer, U., and R. Prohaska. 2001. Stomatin, flotilin-1 and flotilin-2 are major integral proteins of erythrocyte lipid rafts. Blood. 97:1141–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, R.S., W.M. Pruitt, and P.F. Maness. 2000. A MAP kinase-signaling pathway mediates neurite outgrowth on L1 and requires Src-dependent endocytosis. J. Neurosci. 20:4177–4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, T., M. Krug, H. Hassan, and M. Schachner. 1998. Increase in proportion of hippocampal spine synapses expressing neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM180 following long-term potentiation. J. Neurobiol. 37:359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shotton, D.M. 1998. Preparation of human erythrocyte ghosts. Cell Biology. A Laboratory Handbook. Vol. 2. J.E. Cellis, editor. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 26–33.

- Tessier-Lavigne, M., and C.S. Goodman. 1996. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science. 274:1123–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F.S., and P. Doherty. 1997. Neural cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily: role in axon growth and guidance. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:425–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann, J.C., J.G. Chang, W.T. Tse, A.L. Scarpa, V.T. Marchesi, and B.G. Forget. 1990. Full-length sequence of the cDNA for human erythroid β-spectrin. J. Biol. Chem. 265:11827–11832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]