Abstract

Caenorhabditis elegans is a powerful model system widely used to investigate the relationships between genes and complex behaviors like locomotion. However, physiological studies at the cellular level have been restricted by the difficulty to dissect this microscopic animal. Thus, little is known about the properties of body wall muscle cells used for locomotion. Using in situ patch clamp technique, we show that body wall muscle cells generate spontaneous spike potentials and develop graded action potentials in response to injection of positive current of increasing amplitude. In the presence of K+ channel blockers, membrane depolarization elicited Ca2+ currents inhibited by nifedipine and exhibiting Ca2+-dependent inactivation. Our results give evidence that the Ca2+ channel involved belongs to the L-type class and corresponds to EGL-19, a putative Ca2+ channel originally thought to be a member of this class on the basis of genomic data. Using Ca2+ fluorescence imaging on patch-clamped muscle cells, we demonstrate that the Ca2+ transients elicited by membrane depolarization are under the control of Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels. In reduction of function egl-19 mutant muscle cells, Ca2+ currents displayed slower activation kinetics and provided a significantly smaller Ca2+ entry, whereas the threshold for Ca2+ transients was shifted toward positive membrane potentials.

Keywords: Ca2+ currents; C. elegans; muscle; egl-19; excitation-contraction coupling

Introduction

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has become a preparation of prime interest to investigate the relationships between genes and physiological processes and behaviors. The main advantages of this model system include the fully sequenced genome, the short generation time, and the ability to perform extensive genetic maneuvers. However, to precisely determine how the product of a gene influences a cell function requires measurements of its effect on cell activity. In situ physiological studies have been nevertheless greatly restricted in this model system by the difficulty to dissect this microscopic animal and to expose the cells of interest. Thus, although large screens of mutants have led to the identification of genes involved in a variety of functions, very few of these mutants have been characterized at the cellular level.

egl-19 has been postulated to encode the α1 subunit of a pharyngeal voltage-activated L-type Ca2+ channel in C. elegans (Lee et al., 1997). egl-19 was also found to be expressed in body wall muscle cells used for locomotion by the animal (Lee et al., 1997). Null mutants of egl-19 are lethal, whereas reduction of function causes feeble contraction, suggestive of an important role played by these channels in body wall muscle function. Using in situ patch clamp techniques on split worms, high voltage-activated Ca2+ currents were first recorded by Richmond and Jorgensen (1999) in body wall muscles from C. elegans, but the properties and the role of these channels in nematode body wall muscle function are unknown. A primary C. elegans cell culture developed recently also appeared promising for electrophysiological approach (Christensen et al., 2002). However, whole cell Ca2+ currents were not measured in cultured muscle cells.

In this paper, using the whole cell configuration of the patch clamp technique on acutely dissected worms we give a detailed description of the properties of voltage-activated Ca2+ currents in body wall muscle cells from C. elegans and provide experimental evidence that the Ca2+ channels involved belong to the L-type class. Furthermore, we succeeded in coupling a Ca2+ imaging system and the patch clamp technique on muscle cells and demonstrate that these channels play a pivotal role in C. elegans muscle activation. Finally, we show that partial loss of function egl-19 mutant muscle cells have strongly altered Ca2+ currents and require stronger depolarizations to induce intracellular Ca2+ rise, most likely responsible for the flaccid phenotype observed in these worms.

Results

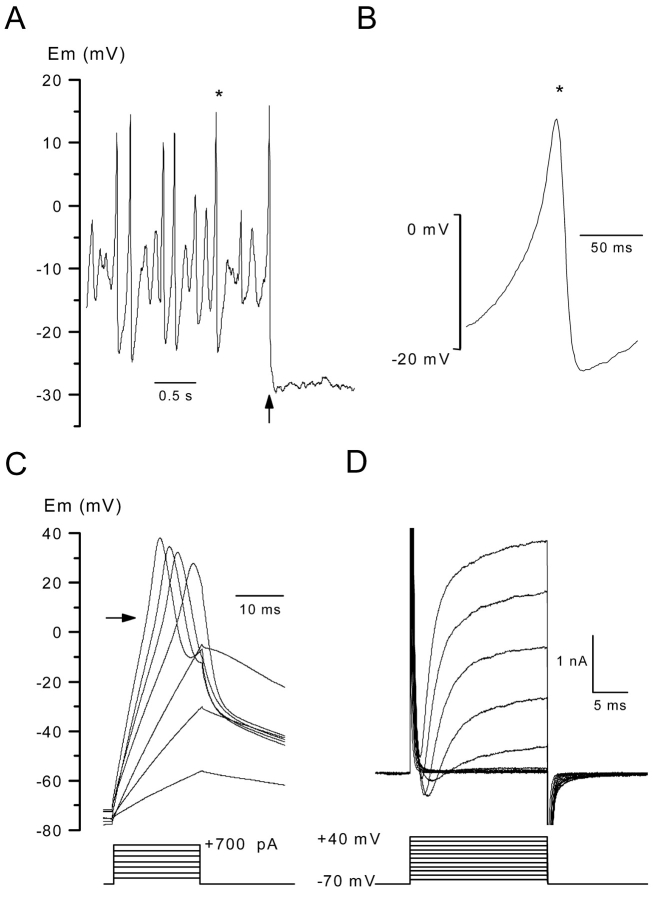

Voltage responses and membrane currents in standard saline

Using the whole cell configuration of the patch clamp technique, we first investigated the electrical excitability of body wall muscle cells. In the presence of standard external medium in the bath and a K+-rich solution in the pipette, the average resting membrane potential of body wall muscle cells was –19.7 ± 1.8 mV (n = 12). In two of eight muscle cells tested, the resting potential was interrupted by spontaneous abortive or overshooting spikes whose amplitude varied from one to another (Fig. 1 A). Under current clamp conditions, the injection of a hyperpolarizing current bringing the membrane potential close to –30 mV totally blocked this spike activity likely because the threshold for the production of these spontaneous responses could not be reached. Fig. 1 B shows one of the spontaneous spikes on an expanded scale. It can be seen that the potential overshot to +15 mV and was followed by a transient hyperpolarization whose amplitude apparently depended upon the height of the preceding spike. To test the possibility to evoke active responses, depolarizing currents of increasing amplitude were then injected into muscle cells from a membrane potential held at –70 mV by applying constant negative current. Measurement of the amplitude of the voltage change induced by injection of 500 ms current pulse of 20 pA amplitude indicated a mean input resistance of 1 ± 0.08 GΩ (n = 10). Out of the 14 cells tested, injection of depolarizing currents never induced voltage responses which could be unambiguously identified as all or none action potentials. However, graded humps were observed for injection of current higher than 300 pA superimposed on the electrotonic potentials (Fig. 1 C). An inflection point visible during the rising phase of the potential responses likely indicated that the graded humps represent active electrical response, resulting from the development of a net inward current activating upon depolarization. In support of this hypothesis, net inward currents were indeed recorded on the same cell under voltage clamp conditions in response to depolarizing voltage pulses. Fig. 1 D shows membrane currents elicited by 20 ms voltage pulses of increasing amplitude from a holding potential of –70 mV. Depolarizing steps to 0, +10, +20, and +30 mV evoked net transient inward currents followed by an outward current, which stabilized to an apparent plateau level. The use of the pharmacological compounds, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)* (3 mM) and tetraethylammonium (TEA) (20 mM) indicated that the total outward current resulted from the presence of two main voltage-dependent K+ conductances, a fast transient 4-AP–sensitive and a delayed outward rectifier TEA-sensitive component as first described by Richmond and Jorgensen (1999) (Jospin et al., 2002). Together, these results strongly suggest that the successive activation of inward and outward currents upon depolarization underlie the spontaneous and evoked graded action potentials generated by C. elegans muscle cells.

Figure 1.

Voltage responses and ionic currents in body wall muscle cells in the presence of standard saline. (A, left) Membrane potential was recorded in a muscle cell in the current clamp mode without current injection. The arrow indicates the time at which a negative hyperpolarizing current was injected. (B) A spontaneous spike indicated by a star in the left panel is shown on an expanded scale. (C) The internal potential was held at –70 mV by passing a constant negative current, and voltage responses were obtained in response to current injection of 20 ms duration in 100 pA increments. The arrow indicates an inflection point during the depolarizing phase. (D) Membrane currents were elicited on the same cell as in C under voltage clamp conditions by applying voltage pulses of 20 ms duration in 10-mV increments from a holding potential of –70 mV.

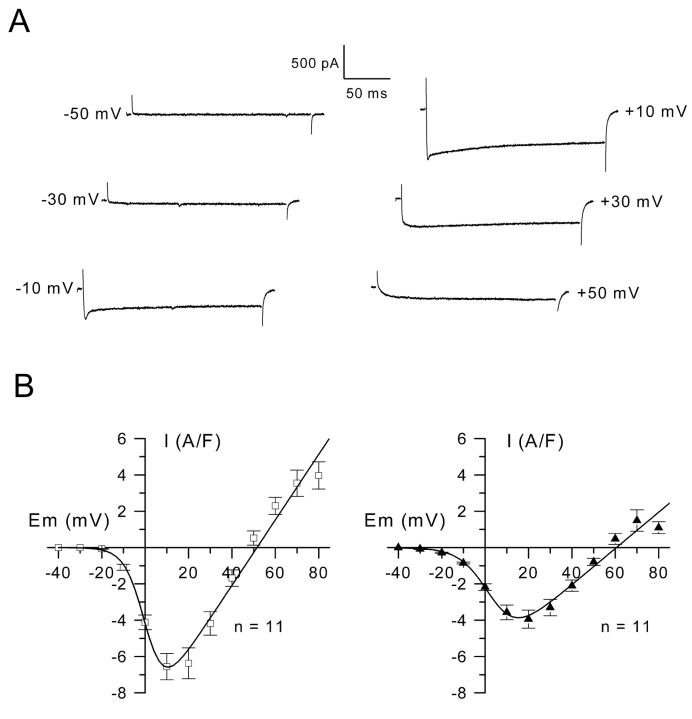

Voltage-activated inward Ca2+ currents

To reveal inward currents during depolarizing steps, opposing outward going potassium currents needed to be blocked by replacing external sodium by TEA, adding the potassium blocker 4-AP and substituting equimolarly Cs+ to K+ in the pipette. Under these conditions, muscle cells were depolarized by steps of 200 ms duration from a holding potential of –70 mV. Fig. 2 A shows that an inward current maintained throughout the depolarizing step developed, and its amplitude increased with depolarization to reach a maximum around +20 mV. It was also systematically observed that at –10, 0, +10, and +20 mV the inward current displayed an early transient peak lasting for ∼10 ms before stabilizing to a plateau level. Fig. 2 B presents the mean current-voltage relationships established for the peak and the steady state currents. For peak and maintained components, threshold of activation was –20 and –30 mV, respectively. Currents peaked at + 10 and +20 mV and reversed at +50 ± 2 mV and +59 ± 2 mV for the peak and the maintained components, respectively. For each cell, the current-voltage relationship was fitted using Eq. 1 (see Experimental procedures). Mean values for G max, V rev, V 0.5, and k were 199 ± 26 S/F, +50 ± 2 mV, +0.6 ± 1.3 mV, and 4.7 ± 0.5 mV for the peak and of 127 ± 20 S/F, +59 ± 2 mV, +6.4 ± 1 mV, and 7.9 ± 0.5 mV for the steady state current, respectively.

Figure 2.

Inward currents and mean current-voltage relationships. (A) Inward currents were evoked on the same cell by voltage pulses in the presence of K+ channel blockers from a holding potential of –70 mV to the indicated values. (B) Mean current-voltage relationships were established at the peak of the currents (left) and at the end of the depolarization pulses (right). The curves were fitted by using Eq. 1 (see Experimental procedures) with values for G max, V rev, V 0.5, and k of 180 S/F, +51 mV, 0.9 mV, and 4.6 mV (left) and of 100 S/F, +60 mV, 3.6 mV, and 6.6 mV (right).

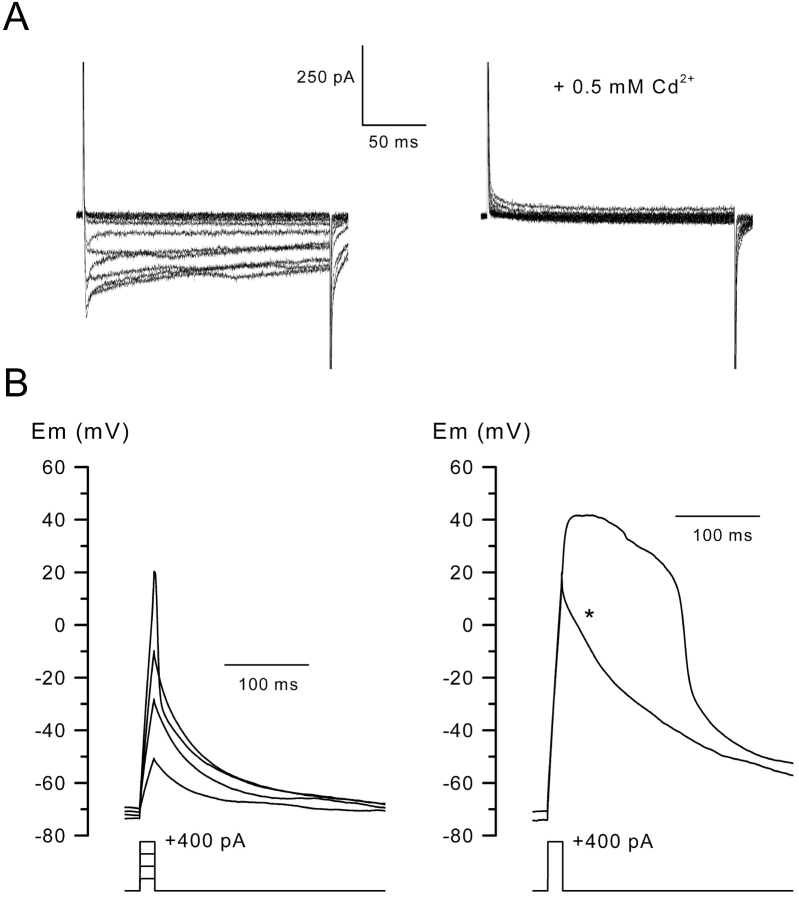

Fig. 3 A shows that the inward current elicited by depolarization was totally suppressed in the presence of 500 μM Cd2+ in the external medium (n = 5). Together, these observations strongly suggest that the two components of currents activated by depolarizing pulses correspond to voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents.

Figure 3.

Effect of Cd2 + on inward currents and on regenerative responses induced by current injection in the presence of K + channel blockers. (A) Inward currents were evoked by voltage pulses in the presence of K+ channel blockers from a holding potential of –70 mV in 10-mV increments in control (left) and in the same cell after addition of Cd2+ (right). (B) Voltage responses were obtained on the same cell under current clamp conditions using the current protocols indicated below, in the presence of a control external medium (left), and in the presence of a solution containing 20 mM TEA and 3 mM 4-AP (right). The internal potential was held at –70 mV by passing a constant negative current. The star shows the voltage response obtained after addition of 500 μM Cd2+ in the external solution.

Long duration Ca2+ spikes

A series of current clamp experiments was then performed to determine if the inward Ca2+ current, which develops in the presence of K+ channel blockers in the external medium, was able to elicit a regenerative all or none response. As described in Fig. 1 C, in the presence of a standard control medium injection of depolarizing currents of increasing amplitude induced graded responses (Fig. 3 B). When 3 mM 4-AP plus 20 mM TEA were added to the bath solution, a current injection of 400 pA amplitude led to the firing of a long lasting all or none action potential that overshot at +42 mV. Subsequent addition of 500 μM Cd2+ to the external solution abolished the regenerative response, indicating that the inward Ca2+ current was responsible for the action potential firing.

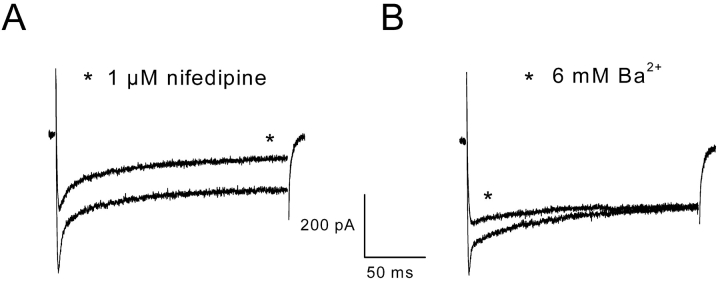

Dihydropyridine sensitivity and Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Ca2+ currents

In the presence of 1 μM nifedipine, a selective blocker of L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, partial inhibition of the peak, and the maintained component was observed (Fig. 4 A). In five cells, the average percentage of inhibition of the peak and of the steady state currents by nifedipine was 56 ± 5% and 47 ± 6%, respectively. In two cells tested, the agonist dihydropyridine Bay K 8644, up to 1 μM, was unable to potentiate current amplitude (unpublished data). When Ba2+ was substituted equimolarly to external Ca2+, the amplitude of the maintained component was not altered, whereas the peak component reversibly disappeared (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Effect on the inward current of the dihydropyridine compound nifedipine and of a substitution of Ba2 + for Ca2 + . (A) Currents were obtained on the same cell in response to a voltage pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of –70 mV. The star indicates the current evoked after addition of 1 μM nifedipine in the external solution. (B) Currents were evoked on the same cell in response to a voltage pulse to +10 mV from a holding potential of –70 mV. The star indicates the current evoked after substitution of 6 mM Ba2+ for 6 mM Ca2+ in the external solution.

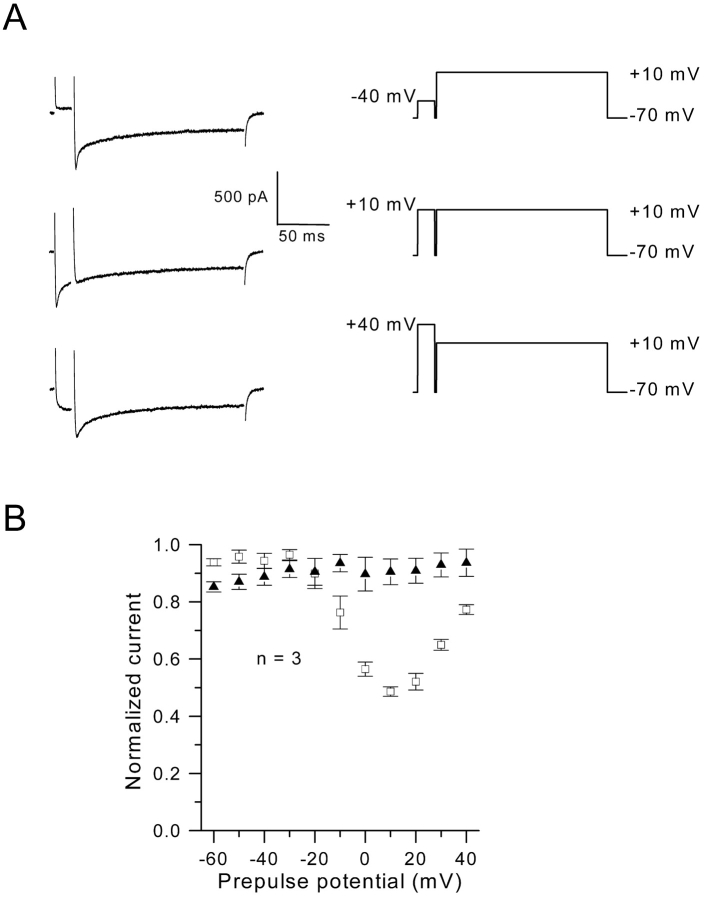

The transient aspect of the early peak component of the Ca2+ current strongly suggests that this current undergoes partial inactivation. This was further investigated using a steady state inactivation protocol. A 200-ms test pulse was delivered to +10 mV, a membrane potential at which the peak component was maximal, and was preceded by a 20-ms depolarizing prepulse of increasing amplitude. Fig. 5 A shows that for a predepolarization to −40 mV, which did not elicit Ca2+ current, the two components of Ca2+ current, which activated during the test pulse, remained unaltered. For a predepolarization to +10 mV, which evoked a robust Ca2+ current, the peak component during the test depolarization vanished, whereas the maintained component remained unchanged. The test Ca2+ current reincreased as the prepulse membrane potential was brought closer to the Ca2+ current reversal potential (+40 mV). The corresponding mean inactivation curve of the peak current is presented in Fig. 5 B. The bell-shaped relationship shows that inactivation was maximal at potentials where the influx of Ca2+ was maximal and attenuated at potentials where the driving force for Ca2+ and thus the influx of Ca2+ declined. When similar experiments were performed in the presence of 6 mM external Ba2+ instead of Ca2+, inward currents were not affected by the presence of a depolarizing prepulse whatever its value (unpublished data).

Figure 5.

Inactivation properties of inward currents. (A) Currents were elicited by the voltage protocol indicated next to each current trace; a first step of 20 ms duration and various amplitude was followed by a 200-ms pulse to +10 mV with a short interpulse hyperpolarization of 2-ms duration to –70 mV. (B) Relative peak current (□) and steady state current (▴) amplitudes are plotted as a function of the 20-ms prepulse potential.

Ca2+ transients in voltage-clamped cells

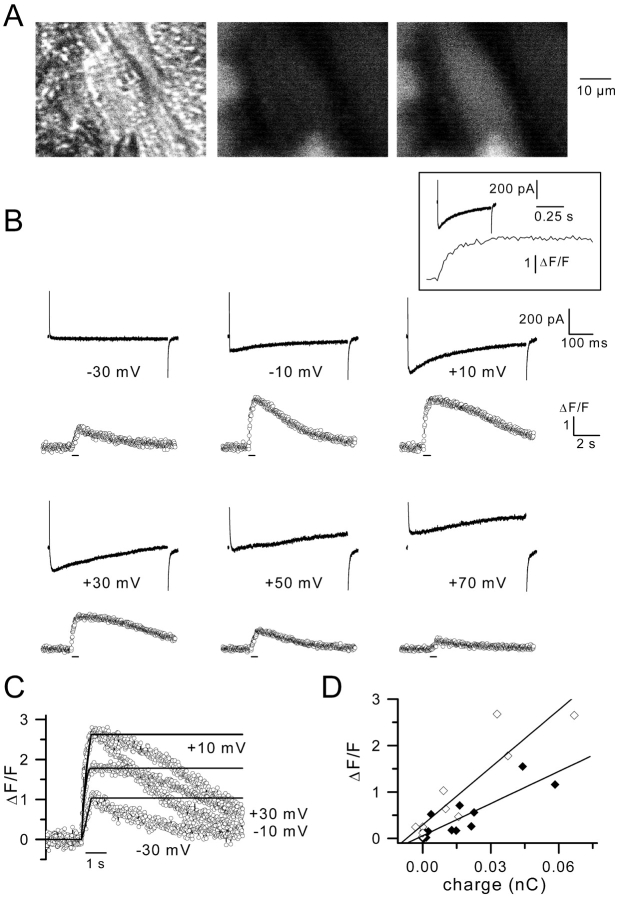

To investigate the physiological role of the voltage-gated Ca2+ current in C. elegans muscle cells, intracellular Ca2+ was measured simultaneously with the Ca2+ current. Fig. 6 A shows the muscle cell under study with the sealed recording pipette under transmitted light (Fig. 6 A, left) and a fluorescence view of the same field before (Fig. 6 A, middle) and during a depolarizing pulse to +10 mV, evoking a Ca2+ transient (Fig. 6 A, right). Fig. 6 B illustrates the membrane currents and the Ca2+ transients obtained from this voltage-clamped body wall muscle cell stimulated with 500 ms duration voltage steps of increasing amplitude. As illustrated in the above experiments, the Ca2+ current appeared at –30 mV, reached a maximum at +10 mV, and then decreased in amplitude for stronger depolarizations. A residual outward voltage-activated K+ current was present in the recordings likely because in this series of experiments the external solution corresponded to an Ascaris medium containing only 20 mM TEA and 3 mM 4-AP. It is clearly shown that the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient followed the one of the Ca2+ current; the Ca2+ transient appeared at –30 mV became maximal at –10 and +10 mV and decreased in amplitude thereafter. This decrease in the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient for high membrane potentials did not result from a run down process, since a maximal Ca2+ transient could again be elicited in response to voltage steps inducing a large inward Ca2+ current (unpublished data). The fact that the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient did not change between –10 and +10 mV while the Ca2+ current did increase was likely due to saturation of the dye. The running integral of the Ca2+ current was superimposed on the time course of the Ca2+ transient obtained at –30, –10, +10, and +30 mV (Fig. 6 C); it can be observed that the intracellular Ca2+ increase followed the integral of the inward Ca2+ current; intracellular Ca2+ kept increasing during the time depolarization was maintained and then dropped to basal levels in a few seconds (Fig. 6 B, inset). Fig. 6 D presents the relationship between the peak Ca2+ transient amplitude and the integral of the corresponding inward Ca2+ current obtained for a series of voltage pulses on two different cells. A linear function was fitted to the two series of data points. Correlation coefficient was 0.88 and 0.9, indicating a close correlation between the intracellular Ca2+ increase and the Ca2+ influx through the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels.

Figure 6.

Ca2 + transients and Ca2 + currents in voltage-clamped cells. (A) The light micrograph in the left panel shows a muscle cell with a recording pipette sealed. The two other panels show the fluorescence images of the same field before (middle) and during a voltage pulse given to +10 mV (right). (B) The same cell was depolarized by 500 ms duration pulses from a holding potential of –70 mV to the indicated potentials. The upper and lower traces correspond to membrane currents and Ca2+ transients, respectively, on different time scales. Fluorescence was sampled at 50 Hz. Inset shows the membrane current and the Ca2+ transient obtained in response to a voltage pulse given to +10 mV on the same time scale. Bars below the fluorescence traces indicate the time during which depolarizing pulses were applied. (C) The running integral of the Ca2+ currents and the corresponding Ca2+ transients were superimposed for pulses to the indicated potentials. For each pulse, the integral of the current was normalized to the peak value of the Ca2+ transient to allow comparison of kinetics. For pulses to –10 and +10 mV, the integrals of current merge into one. (D) The amplitude of the Ca2+ transients were plotted against the integral of the corresponding Ca2+ currents for two different cells (⋄ and ♦, respectively) depolarized by 500 ms duration pulses from a holding potential of –70 mV up to +30 mV. A linear function was fitted to data points for each cell.

Voltage responses and Ca2+ currents in egl-19 mutants

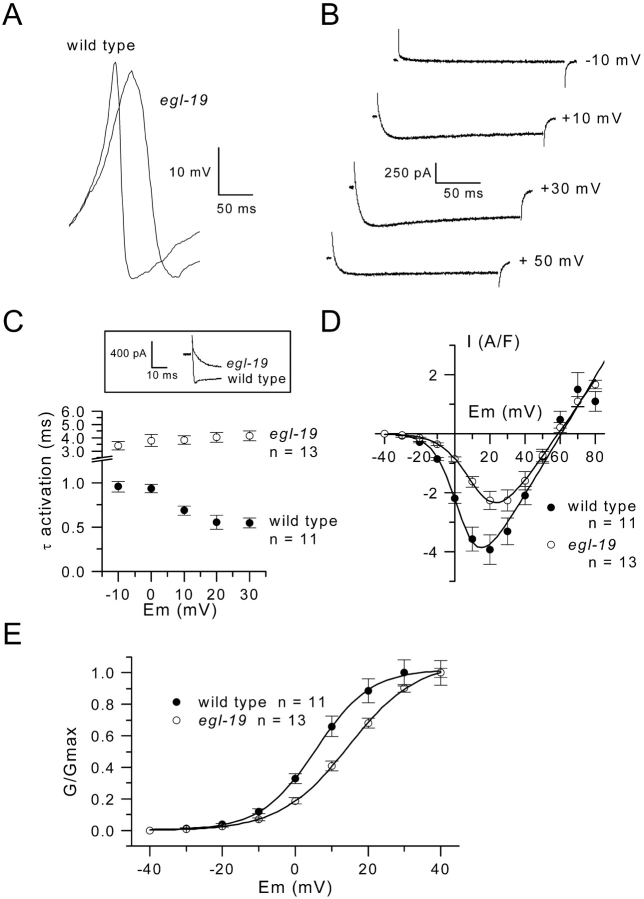

We then investigated the electrophysiological properties of egl-19 mutants. Among the different mutant alleles of the egl-19 gene, we selected one reduction of function allele, n582, a flaccid mutation class causing a feeble muscle contraction phenotype originally described by Trent et al. (1983). Under current clamp conditions, spontaneous spike potentials could also be recorded in egl-19 mutant muscle cells. However, as shown in Fig. 7 A, where a spontaneous spike from a wild-type and an egl-19 muscle cell are superimposed, the rising phase of the voltage response was considerably slowed in the egl-19 cell. The mean maximal slope (dV/dt) of the rising phase of the spikes was 1.38 ± 0.11 V/s in wild-type cells (n = 6) and significantly lower (Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.0022), 0.63 ± 0.015 V/s, in egl-19 mutant cells (n = 6). A series of voltage clamp experiments on egl-19 mutant muscle cells did not reveal any apparent alteration of voltage-dependent K+ currents (unpublished data). On the other hand, using the same experimental conditions as the one used previously for Ca2+ current recordings, we found that egl-19 mutant muscle cells displayed strongly altered voltage-activated Ca2+ currents. Fig. 7 B shows that Ca2+ currents activated in response to depolarizing pulses in egl-19 cells did not display the fast transient peak observed in wild-type worm muscle cells. In the 13 egl-19 muscle cells tested, this component was never observed. Current traces also clearly indicated that the sole maintained component activated much slower than in the wild-type worm muscle (Fig. 7 C, inset). An exponential function was fitted to the rising phase of the current at –10, 0, +10, +20, and +30 mV, and the mean time constant of activation was plotted against membrane potential in wild-type and mutant cells (Fig. 7 C). At –10 and +30 mV, τ was 0.95 ± 0.06 ms and 0.54 ± 0.06 ms in wild-type muscle (n = 11), whereas it was 3.4 ± 0.34 and 4.14 ± 0.37 ms for corresponding potentials in egl-19 mutant cells (n = 13); the time constants of activation of the Ca2+ current were significantly higher in mutant cells (Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.0002 for –10 mV and P < 0.0001 for other potentials). Moreover, activation became faster with increasing depolarization in wild-type muscle, whereas in egl-19 muscle activation slightly slowed with depolarization, suggesting that the voltage dependence of the time course of activation was lost. Fitting the steady state current-voltage relationship in egl-19 mutant muscle cells indicated mean values for G max, V rev, V 0.5, and k of 93 ± 9 S/F, +57 ± 2 mV, +14.4 ± 1.3 mV, and 8.9 ± 0.4 mV, respectively (Fig. 7 D). Statistical analysis indicated that the significant effect observed in egl-19 mutants was a shift of 8 mV of V 0.5 toward positive potentials (Student's unpaired t test, P = 0.0002). This voltage shift is clearly shown in Fig. 7 E where the mean normalized conductance voltage relationships in wild-type and egl-19 mutant cells are presented.

Figure 7.

Spontaneous spikes and inward current properties in egl-19 mutant muscle cells. (A) Spontaneous spikes recorded in the current clamp mode without current injection in a wild-type and in an egl-19 mutant muscle cell are superimposed. Voltage responses have been shifted on voltage axe to allow comparison. (B) Inward currents were elicited from a holding potential of –70 mV to the indicated voltages. (C) The time constant of activation of the inward current was plotted as a function of the membrane potential in egl-19 (○) and wild-type (•) muscles. Inset shows Ca2+ currents obtained at +10 mV in a wild-type and egl-19 muscle cell superimposed on an expanded scale. (D) The mean current-voltage relationship of the steady state inward current in wild-type and egl-19 muscle are presented. The curve for egl-19 muscle was fitted by using Eq. 1 (see Experimental procedures) with values for G max, V rev, V 0.5, and k of 86 S/F, +59 mV, 13.6 mV, and 8.4 mV. (E) The mean normalized conductance was plotted as a function of voltage in egl-19 (○) and wild-type (•) muscles. The curves were fitted by using a Boltzman equation with V 0.5 = 5.6 and k = 7.5 in wild-type and V 0.5 = 14.5 and k = 9.4 in egl-19 muscles, respectively.

Ca2+ currents in egl-19 mutant muscle cells were also found to be completely blocked by 500 μM Cd2+ and reduced to the same extent as in wild-type muscle by 1 μM nifedipine (unpublished data). Although substitution of Ba2+ for Ca2+ suppressed the peak component of the Ca2+ current in wild-type muscle, this maneuver had no marked effect on egl-19 Ca2+ currents, as expected, given the absence of such a component in egl-19 currents.

For voltage pulses eliciting a Ca2+ current of maximal amplitude, i.e., +10 and +20 mV in wild-type and mutant cells, respectively, the integral of the Ca2+ current was calculated. The mean value of the integral of the current was 0.816 ± 0.087 and 0.554 ± 0.071 C/F in wild-type and mutant cells, respectively. Thus, the loss of the early component of Ca2+ influx was accompanied by a significant lower amount of Ca2+ entering muscle cells in mutant compared with wild-type muscle (Student's unpaired t test, P = 0.029).

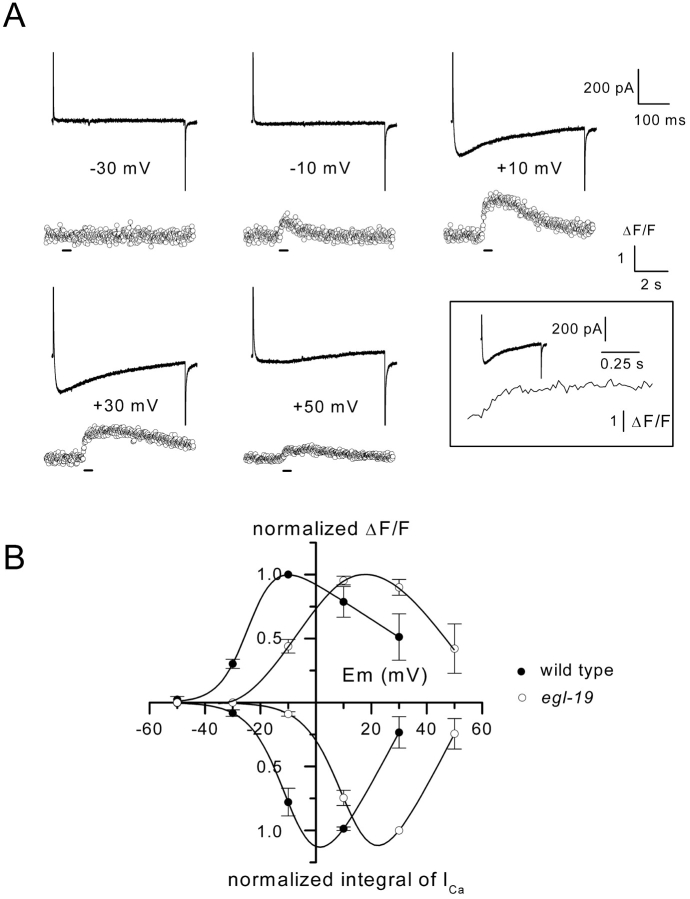

Ca2+ transients in voltage-clamped egl-19 mutant cells

Intracellular Ca2+ was also measured simultaneously with Ca2+ currents in voltage-clamped egl-19 mutant cells. Fig. 8 A illustrates the membrane currents and the Ca2+ transients obtained from an egl-19 mutant cell stimulated with 500 ms duration voltage steps of increasing amplitude. As observed in wild-type muscle cells, a close relationship was found between the Ca2+ transient and the Ca2+ current. The inset, displaying a Ca2+ current and a Ca2+ transient on the same time scale, also clearly shows that intracellular Ca2+ kept increasing, whereas the Ca2+ current developed and then stabilized upon termination of the voltage pulse. A marked discrepancy found in egl-19 muscle cells was that the threshold for Ca2+ current and Ca2+ transient was shifted toward positive membrane potentials with respect to wild-type cells. This result is clearly illustrated in Fig. 8 B where the mean normalized amplitude of the Ca2+ transient and the mean normalized value of the integral of the Ca2+ current are plotted as a function of membrane potential in wild-type and egl-19 mutant cells. Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ transient both appeared at –30 mV in wild-type muscle cells, whereas neither Ca2+ influx nor Ca2+ transient could be detected at this membrane potential in egl-19 mutant cells (Fig. 8 A). For stronger depolarizations, the relationship between Ca2+ transient and membrane potential mirrored the relationship between Ca2+ influx and membrane potential in both cell types. The mean maximal amplitude of the Ca2+ transient in wild-type (ΔF/F = 1.34 ± 0.49 [n = 4]) and in egl-19 muscle cells (ΔF/F = 2.2 ± 0.64 [n = 5]) were found to be not significantly different (Student's unpaired t test, P = 0.34). Finally, the sampling period of Ca2+ imaging (20 ms), during which Ca2+ currents fully activated in both cell types did not allow us to detect modification in the rate of rise of the Ca2+ transient in egl-19 mutant cells, possibly caused by the slowing of the activation of the Ca2+ current.

Figure 8.

Ca2 + transients and Ca2 + currents in egl-19 mutant muscle cells. (A) The cell was depolarized by 500-ms duration pulses from a holding potential of –70 mV to the indicated potentials. The upper and lower traces correspond to membrane currents and Ca2+ transients, respectively, on different time scales. Fluorescence was sampled at 50 Hz. Inset shows the membrane current and the Ca2+ transient obtained in response to a voltage pulse given to +10 mV on the same time scale. Bars below the fluorescence traces indicate the time during which depolarizing pulses were applied. (B) The mean normalized amplitude of the Ca2+ transients and the mean normalized value of the integral of the Ca2+ currents in wild-type and egl-19 muscle cells were plotted as a function of membrane potential. Data points correspond to values averaged from five series of voltage pulses applied in three egl-19 cells and four series of voltage pulses applied in two wild-type cells, respectively. Data points were normalized to the maximal mean value obtained in wild-type and egl-19 muscle cells, respectively. The curves were drawn by eyes.

Discussion

Ca2+ currents properties in C. elegans muscle

In this study, using in situ patch clamp technique on dissected worms we give the first detailed description of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel properties in body wall striated muscle cells from wild-type and egl-19 mutant nematodes. In wild-type muscle, in the presence of K+ channel blockers membrane depolarizations above −40 mV elicited Ca2+ inward currents, which peaked around +20 mV and reversed between +50 and +60 mV. These Ca2+ currents were characterized by two kinetically distinct components: a fast transient component lasting ∼10 ms followed by a component maintained throughout the 200 ms depolarization step. At first sight, this could indicate the existence of two types of Ca2+ channels. However, we showed that the Ca2+ channel blocker of the dihydropyridine class, nifedipine, reduced to the same extent both peak and maintained component of the current. Our results are thus consistent with only one channel population exhibiting a biphasic time course of activation of the Ca2+ current. Moreover, steady state inactivation experiments demonstrated that the early decay in Ca2+ current was related on an inactivation process resulting from Ca2+ current flow. Conditioning voltage pulses eliciting Ca2+ entry led to an inhibition of the transient peak component of the inward current elicited by a subsequent test depolarization, suggesting that inactivation was due to accumulation of Ca2+ at the inner surface of the membrane. Our experiments performed in the presence of Ba2+ confirm our Ca2+-dependent inactivation hypothesis. Indeed, in the presence of Ba2+, which is known to be less effective as intracellular Ca2+ in blocking the channel, inactivation was not observed. Additionally, the amplitude of the early peak component was reduced suggesting that Ba2+ does not conduct as well as Ca2+; this reduced permeation might be compensated by the reduced inactivation so that the maintained component remained unaffected in the presence of Ba2+. Ca2+-dependent inactivation of high voltage threshold Ca2+ channels have also been reported in other invertebrate cells, for example, Paramecium, Amphioxus myotome, and Aplysia neuron or muscle (Brehm and Eckert, 1978; Tillotson, 1979; Benterbusch and Melzer, 1992; Brezina et al., 1994).

Voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in C. elegans muscle belong to the L-type class

The Ca2+ currents described in this study share the main characteristics of vertebrate voltage-activated Ca2+ currents belonging to the L-type class, i.e., high voltage threshold of activation, the presence of a long lasting phase of current, total blockade by Cd2+, and sensitivity to dihydropyridines (DHPs). However, Ca2+ currents in C. elegans muscle exhibit much faster activation and inactivation kinetics than in vertebrate preparations. Such rapid kinetics in the millisecond range seem nevertheless to be common features in invertebrate tissues and have been observed for example in Amphioxus myotome and Aplysia muscle (Benterbusch and Melzer, 1992; Brezina et al., 1994). We also found that Ca2+ currents in C. elegans muscle were less sensitive to the DHP antagonist nifedipine than mammalian L-type channels and insensitive to the DHP agonist BayK 8644. Such discrepancies in the pharmacological properties with vertebrate L-type channels were also found in Amphioxus myotome and Aplysia muscle (Benterbusch et al., 1992; Brezina et al., 1994), and more generally it is known that invertebrate channels classified as L-type channels on the basis of molecular and biophysical criteria may display marked pharmacological differences with vertebrate L-type channels (Kits and Mansvelder, 1996; Skeer et al., 1996; Jeziorski et al., 2000). Along this line, by investigating mutant C. elegans strains Lee et al. (1997) have cloned a gene, egl-19, that encodes a protein which exhibits structural similarity to the pore-forming α1 subunit of vertebrate muscle L-type voltage-activated Ca2+ channel. egl-19 was found to be expressed in body wall, pharyngeal, egg-laying, and enteric muscles. Our electrophysiological data strongly suggest that the voltage-gated Ca2+ channel displaying L-type properties here described corresponds to EGL-19, although the possible contributions of other calcium channels whose genes are known to be present in C. elegans cannot be excluded (Bargmann, 1998; Jeziorski et al., 2000).

Mutation in the S4 segment in egl-19 mutants alters Ca2+ currents

Null mutation in egl-19 is lethal and was demonstrated to induce an embryonic arrest phenotype due to block of body wall muscle contraction (Williams and Waterston, 1994). Among viable egl-19 alleles, one loss of function mutation, n582, led to a flaccid phenotype characterized by feeble body wall muscle contraction (Trent et al., 1983; Lee et al., 1997). Interestingly, intracellular measurement of action potentials from pharyngeal terminal bulb muscle revealed that the rate of depolarization was reduced in n582 animals (Lee et al., 1997). Our results obtained on patch-clamped body wall muscle cells demonstrate that voltage-activated Ca2+ currents are also strongly altered in n582 mutants. First, the rate of current activation was dramatically reduced in mutants, and the voltage dependence of the time constant of activation was disrupted; this has to be paralleled to the reduced rate of depolarization observed in the body wall muscle spontaneous spikes but also in pharyngeal muscle action potentials (Lee et al., 1997). Second, the midpoint voltage (V 0.5) of the conductance-voltage relationship was shifted by 8 mV in the depolarized direction. In n582 mutation, arginine 899 is changed to a histidine in the S4 transmembrane segment of the third repeat in the α1 subunit (Lee et al., 1997). The S4 transmembrane segment has been shown to function as a voltage sensor in voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels (Tanabe et al., 1987; Garcia et al., 1997; Yamaguchi et al., 1999). Significant shift to the right of the midpoint potential and lengthening of the time constant of activation were produced by mutations of S4 arginine to neutral or negative residues principally in the first and third repeats (Garcia et al., 1997). Similar perturbations in channel gating and loss of the voltage dependence of the activation time course were also observed with a mutation of an arginine to a histidine in the S4 segment of the fourth domain of the skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel identified in families suffering from hypokalaemic periodic paralysis (Morrill and Cannon, 1999). Our data thus reinforces the notion that charged residues in the S4 segment play a fundamental role in Ca2+ channel activation by setting the voltage dependence of the channel.

Physiological role of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in C. elegans muscle

No voltage-activated Na+ channel has been found in the C. elegans genome (The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium, 1998), which is consistent with the absence of such an activity in our voltage clamp recordings. In spite of the absence of voltage-activated Na+ channels, we found that C. elegans body wall muscle cells were able to generate spontaneous spike potentials in standard external saline. Such spontaneous activity has been recorded early on in somatic muscle cells of the closely related nematode species Ascaris lumbricoides (Jarman, 1959; De Bell et al., 1963). Ion substitution experiments have demonstrated that Ca2+ currents were responsible for these spikes in Ascaris (Weisblat et al., 1976). Despite the marked size discrepancy, the morphology of somatic muscle cells in Ascaris and C. elegans displays a striking degree of similarity and consists of three parts: (i) a large sarcomere-containing compartment, (ii) a bag-shaped structure containing the intracellular organites, and (iii) a slender process, the arm, sent out to the nerve cord (Rosenbluth, 1965; White et al., 1976, 1986). De Bell et al. (1963) showed that spontaneous depolarizations were myogenic, arising from a syncitium of muscle arms, which branch and interdigitate with each other at the level of the nerve cord; the spike potentials were postulated to then propagate electrotonically to the rest of the cell. In view of the close similarities of the morphology and spontaneous electric responses observed in Ascaris, it is very likely that comparable mechanisms are responsible for spontaneous spikes in C. elegans muscle cells. Moreover, the graded action potentials elicited in response to positive current injection also closely resembled the evoked voltage responses developed by Ascaris muscle cells (De Bell et al., 1963; Del Castillo et al., 1967). Our voltage clamp experiments conducted in the presence of standard external saline revealed that in response to depolarization Ca2+ currents were net inward going before robust outward K+ currents activated. Ca2+ currents may hence be responsible for the initial rising phase of the graded action potentials, whereas K+ currents may well account for the repolarizing phase of the graded humps but also for the transient hyperpolarization that followed spontaneous spikes. Finally, our results obtained in the presence of K+ channel blockers confirmed the ionic mechanisms underlying these voltage responses. As originally described in crab muscle by Fatt and Katz (1953) and since in a great number of invertebrate preparations (see Hagiwara and Byerly, 1981), we indeed demonstrated that graded action potentials could be converted into all or none Ca2+ action potentials when inhibiting K+ channels with TEA and 4-AP.

Ca2+ ions may have not only influence on C. elegans muscle excitability but also likely, itself, play a pivotal role in C. elegans body wall muscle function. Body wall muscle cells are polyinnervated both by excitatory acetylcholine and inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid motor neurons (Lewis et al., 1980; McIntire et al., 1993a,b; Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999). As described in Ascaris muscle cells, it is plausible that opening of cholinergic receptors initiates graded action potentials at the level of the syncitium where synaptic inputs from motor neurons converged and graded action potentials next propagate electrotonically to the sarcomere-containing compartment of the cells. Given the close proximity of sarcomeres to the plasma membrane, the resulting activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels may provide a Ca2+ influx sufficient to directly initiate contraction as described in many invertebrate muscle cells (Hagiwara and Byerly, 1981; Brezina et al., 1994; Kits and Mansvelder, 1996). Kerr et al. (2000) have imaged calcium transients in intact transgenic nematodes expressing the calcium indicator protein cameleon and have shown that Ca2+ transients accompanied body wall muscle contractions. Here, for the first time, we used a Ca2+-sensitive dye in C. elegans muscle and successfully recorded Ca2+ transients in voltage-controlled muscle cells. Our fluorescence experiments show that the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient depended on the magnitude of the inward current: Ca2+ transient appears at the voltage threshold of the Ca2+ current, is maximal at voltages inducing the largest currents, and becomes smaller with the reduced Ca2+ entry at further depolarizations. Alternatively, Ca2+ entering through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels may also trigger a Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from internal stores as well as defined in vertebrate cardiac cells and also already described in invertebrate crayfish muscle cells (Fabiato, 1983; Györke and Palade, 1992). Sarcoplasmic reticulum has indeed been identified in C. elegans body wall muscle cells as a network of vesicules that surround dense bodies, the site of attachment for thin myofilaments (Wood, 1988; Maryon et al., 1998). The ryanodine receptor, the ionic channel that gates Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, has been characterized in C. elegans (Kim et al., 1992). This receptor is encoded by the unc-68 gene (Maryon et al., 1996; Sakube et al., 1997), and UNC-68 has been localized in body wall muscle cells to the vesicular structures assumed to represent the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Maryon et al., 1998). unc-68–null mutants are defective in locomotion (Brenner, 1974) but exhibit only incomplete flaccid paralysis, suggesting that ryanodine receptor function enhances motility but is not necessary in excitation-contraction coupling (Maryon et al., 1996). Consistent with our data, ryanodine receptors can then be thought to only act to amplify the Ca2+ signal that is mainly activated directly by the Ca2+ ions entering through the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels characterized in this study.

Finally, consistent with the n582 mutation Ca2+ imaging experiments on voltage-clamped egl-19 muscle cells indicated that the threshold for intracellular Ca2+ rise was shifted toward positive membrane potentials with respect to wild-type cells. The amount of Ca2+ entering egl-19 muscle cells was also found to be reduced by 30%. However, in terms of absolute peak-free Ca2+ concentration the consequence of a 30% reduction in total Ca2+ influx was expected to be hardly detectable under the present conditions due to limitations related both to the dye and to the complexity of the relationship between the rate of Ca2+ entry and the actual size of the free Ca2+ transient. Because of technical limitations, we were also unable to determine whether or not the rate of rise of the Ca2+ transient was decreased in egl-19 mutant cells. Nevertheless, the shift of the relationship between Ca2+ transient and membrane potential toward positive voltages may alone account for the flaccid phenotype that characterizes egl-19 mutants. We indeed demonstrated that C. elegans muscle cells develop spontaneous spike potentials of various amplitudes; depending on the potential reached, depolarization of the muscle cell of a given amplitude may trigger a substantial intracellular Ca2+ rise in wild-type muscle, whereas a depolarization of the same magnitude may induce a lower Ca2+ rise or no Ca2+ rise at all in egl-19 mutant muscle. However, the fact that a shift of the same extent was observed in the Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ transient between wild-type and egl-19 mutants strengthens the central role played by the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in C. elegans muscle activation.

In conclusion, the detailed description of the Ca2+ current properties and the combination of fluorescence and patch clamp techniques allowed us to unravel the properties of activation of C. elegans body wall muscle which up to now has remained unknown. This type of study represents an inescapable complement to the phenotypic characterization of mutant nematodes. Furthermore, it will definitely be of great help in determining the role of proteins relevant to muscle function, which would be hard to achieve solely with behavioral studies.

Materials and methods

Strains

Experiments were performed on derivatives of the N2 reference strain and of strain MT1212, which carries the egl-19(n582) mutation. To identify body wall muscle cells more easily after dissection, both strains were marked by an extra chromosomal unc-54:gfp transgene, which promotes GFP expression in body wall muscles. In these strains, LS543 and LS716, respectively, most body wall muscles were strongly fluorescent. LS543 was obtained by microinjecting unc-54:gfp DNA in N2 at a concentration of 50 ng/μL using standard techniques and selecting fluorescent offspring. LS716 was obtained by crossing LS543 into MT1212 and selecting fluorescent animals of egl-19(n582) phenotype in the F2 progeny. For Ca2+ transient measurements, N2 and MT1212 strains were used.

Dissection

The dissection technique was adapted from Richmond and Jorgensen (1999) and Goodman et al. (1998). Adult nematodes were glued by applying a cyanoacrylic glue (Histoacryl Blue; B. Braun) along one side of the body. An incision was made in the cuticle using a sharpened tungsten rod (Phymep). The viscera were cleared, and the cuticle flap was pushed down with a glass rod held by a micromanipulator. Cellular surfaces were cleaned during 30 s using an external solution containing 2 mg/ml of collagenase (Type 1; Sigma-Aldrich). Recording pipettes were sealed on ventral GFP-expressing body wall muscle cells except for experiments in Figs. 6 and 8 where muscle cells did not express GFP to avoid interference with Ca2+ fluorescence measurements. All experiments were performed at room temperature (21–24°C).

Electrophysiology

Membrane currents and membrane potentials were recorded in the whole cell configuration using a patch clamp amplifier (model RK 400; Bio-Logic). The resistance of recording pipettes was within 2–3 MΩ. Acquisition, generation of command voltage, and current pulse were done using the Biopatch software (Bio-Logic) driving an A/D, D/A converter (Lab Master DMA board; Scientific Solutions Inc.). Currents and potential differences were analyzed using Microcal Origin software (Microcal Software Inc.). Resistance and capacitance were not compensated. Cell capacitance was determined by integration of a control current trace obtained with a 10-mV depolarizing pulse from the holding potential. This capacitance was used to calculate the density of Ca2+ currents (A/F). Leak currents were subtracted from all recordings using a 10-mV depolarizing pulse from the holding potential supposing a linear evolution of leak current with depolarization. Individual curves of the voltage dependence of the Ca2+ current density were fitted with Eq. 1:

|

(1) |

where I(V) is the density of the current measured, V is the test pulse, G max is the maximum conductance, V rev is the apparent reversal potential, V 0.5 is the half-activation voltage, and k is a steepness factor. Individual curves of the voltage dependence of the normalized conductance were obtained by dividing I(V) by G max(E − Erev). The time constant of activation of the Ca2+ current was obtained by fitting a single exponential function to the current from the point where the charge of capacitance was completed to the peak of the current.

Voltage uniformity

Ultrastructural studies suggest that body wall muscle cells are coupled via gap junctions (White et al., 1976, 1986). However, our Ca2+ fluorescence experiments indicated that only the cells patched and dialysed with fluo-3, which is known to cross gap junctions (Carter et al., 1996), emitted fluorescence even after 20 min of dialysis. The fact that fluo-3 never diffused to adjacent cells strongly suggests that muscle cells are not coupled under our experimental conditions.

Recordings have been made on ventromedial muscle cells adjacent to the ventral nerve cord that project short muscle arms, which minimizes space clamp problems. Nevertheless, an estimate of the spatial uniformity of the membrane voltage was made with the following assumptions: cells of 100 μm in length and 10 μm in diameter were considered to be analogous to a short cable with an internal resistivity of 100 Ωcm. In the worst case, i.e., when a maximal K+ current of 5 nA amplitude developed, the input resistance drops to 20 MΩ. In that case, R m was calculated to be 628 Ωcm2 and the space constant (λ) 560 μm. From linear cable theory, if a current is injected into one end of a cable of length L and space constant λ, the other end being sealed, then the fractional variation of voltage along the cell according to Attwell and Wilson (1980) is as follows in Eq. 2:

|

(2) |

Using the above values for L and λ, we found that ΔV/V is 0.016, so the voltage can be considered as uniform and the cell isopotential.

Fluorescence measurements

For these experiments, muscle cells were not labeled with GFP. Cells were loaded with fluo-3 through the patch pipette, the dye being added at a concentration of 300 μM to the intrapipette solution. After whole cell voltage-clamp was established, fluo-3 was allowed to diffuse for 2 min before voltage pulses were applied. Experiments were performed on an inverted microscope (Olympus IMT2) equipped for epifluorescence. Cells were imaged using a ×20 objective. Fluo-3 fluorescence was produced by excitation from a 100 W mercury-vapor lamp and an appropriate filter set (excitation, 450–480 nm; emission, above 515 nm, dichroic mirror 500 nm). Images from a region of interest (280 × 280 pixels) centered on the cell under study were captured with a Coolsnapfx charge-coupled device camera (Roper Scientific) at a frequency of 50 Hz. In some cases (as illustrated in Fig. 6 A), 4 × 4 binning was used to increase the image acquisition rate. Image acquisition and processing were performed using the MetaVue imaging workbench (Universal Imaging Corp.). The mean intensity of fluorescence (F) was measured from an area of the cell away from the tip of the patch pipette. Background fluorescence was measured from an area distant from the studied cell and subtracted from the corresponding F. No attempt was done to convert the changes in fluo-3 fluorescence in terms of absolute changes in [Ca2+]. Fluorescence values were expressed as ΔF/F, F being the baseline fluorescence and ΔF the change in fluorescence from baseline.

Solutions and chemicals

For potential and current recordings in the whole cell configuration in the presence of standard saline (Fig. 1, Fig. 3 B, and Fig. 7 A), pipettes were filled with an internal solution containing (in mM) 120 KCl, 20 KOH, 4 MgCl2, 5 TES, 4 Na2ATP, 36 sucrose, and 5 EGTA, pH 7.2, and the bath solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 6 CaCl2, 5 MgCl2, 11 sucrose, and 5 Hepes, pH 7.2. For inward current recordings without fluorescence measurements, worm dissection was conducted in a modified Ascaris solution containing (in mM) 23 NaCl, 110 NaAc, 5 KCl, 6 CaCl2, 5 MgCl2, 11 sucrose, and 5 Hepes, pH 7.2. After dissection, the muscle cells were superfused with a solution containing (in mM) 140 TEAmethanesulfonate, 6 CaCl2 (or 6 BaCl2 when mentioned), 5 MgCl2, 3 4-AP, and 10 Hepes, pH 7.2; pipettes contained (in mM) 140 CsCl, 4 MgATP, 5 TEACl, 5 EGTA, 5 TES, pH 7.2. For inward current recordings coupled to fluorescence measurements, pipettes contained the Cs+-rich solution without EGTA plus 300 μM of the Ca2+ dye fluo-3, and the bath solution contained an Ascaris Ringer plus 20 mM TEA and 3 mM 4-AP. Nifedipine (ICN Biomedicals) was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mM. TEACl, 4-AP, nifedipine, and cadmium were diluted to the required concentrations in the bath solution. Cells were exposed to different solutions by placing them in the mouth of a perfusion tube from which flowed by gravity the rapidly exchanged solutions. Voltages were not corrected for liquid junction potentials, which were calculated to be lower than 5 mV with the different solutions used.

Statistics

Nonlinear least-squares fits were performed using a Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm routine included in Microcal Origin. Data values are presented as means ± SEM. Data were statistically analyzed using Student's unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney test. Values were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to André Bilbaut, Robert Bonvallet, Christophe Chouabe, and Oger Rougier for helpful discussion while the manuscript was in preparation.

This study was supported by funds from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Ministère de la Recherche (Action Concertée Incitative Project 2000), the Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, and the Association Française contre les Myopathies.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: 4-AP, 4-aminopyridine; DHP, dihydropyridine; TEA, tetraethylammonium.

References

- Attwell, D., and M. Wilson. 1980. Behaviour of the rod network in the tiger salamander retina mediated by membrane properties of individual rods. J. Physiol. 309:287–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann, C.I. 1998. Neurobiology of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Science. 282:2028–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benterbusch, R., and W. Melzer. 1992. Ca2+ current in myotome cells of the lancelet (Banchiostoma lanceolatum). J. Physiol. 450:437–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benterbusch, R., F.W. Herberg, W. Melzer, and R. Thieleczek. 1992. Excitation-contraction coupling in a pre-vertebrate twitch muscle: the myotome of Banchiostoma lanceolatum. J. Membr. Biol. 129:237–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm, P., and R. Eckert. 1978. Calcium entry leads to inactivation of calcium channel in Paramecium. Science. 202:1203–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S. 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezina, V., C.G. Evans, and K.R. Weiss. 1994. Characterization of the membrane ion current of a model molluscan muscle, the accessory radula closer muscle of Aplysia californica. III. depolarization-activated Ca current. J. Neurophysiol. 71:2126–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. 1998. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 282:2012–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, T.D., X.Y. Chen, G. Carlile, E. Kalapothakis, D. Ogden, and W.H. Evans. 1996. Porcine aortic endothelial gap junctions: identification and permeation by caged InsP3. J. Cell Sci. 109:1765–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M., A. Estevez, X. Yin, R. Fox, R. Morrison, M. McDonnell, C. Gleason, D.M. Miller, and K. Strange. 2002. A primary culture system for functional analysis of C. elegans neurons and muscle cells. Neuron. 33:503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bell, J.T., J. Del Castillo, and V. Sanchez. 1963. Electrophysiology of the somatic muscle cells of Ascaris lumbricoides J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 62:159–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo, J., W.C. De Mello, and T. Morales. 1967. The initiation of action potentials in the somatic musculature of Ascaris lumbricoides. J. Exp. Biol. 46:263–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato, A. 1983. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am. J. Physiol. 245:C1–C14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatt, P., and B. Katz. 1953. The electrical properties of crustacean muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 120:171–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, J., J. Nakai, K. Imoto, and K.G. Beam. 1997. Role of S4 segments and the leucine heptad motif in the activation of an L-type calcium channel. Biophys. J. 72:2515–2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, M.B., D.H. Hall, L. Avery, and S.R. Lockery. 1998. Active currents regulate sensitivity and dynamic range in C. elegans neurons. Neuron. 20:763–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Györke, S., and P. Palade. 1992. Calcium-induced calcium release in crayfish skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 457:195–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, S., and L. Byerly. 1981. Calcium channel. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 4:69–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman, M. 1959. Electrical activity in the muscle cells of Ascaris lumbricoides Nature. 184:1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeziorski, M.C., R.M. Greenberg, and P.A.V. Anderson. 2000. The molecular biology of invertebrate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. J. Exp. Biol. 203:841–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jospin, M., M.C. Mariol, L. Ségalat, and B. Allard. 2002. Characterization of K+ currents using in situ patch clamp technique in body wall muscle cells from Caenorhabditis elegans J. Physiol. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, R., V. Lev-Ram, G. Baird, P. Vincent, R.Y. Tsien, and W.R. Schafer. 2000. Optical imaging of calcium transients in neurons and pharyngeal muscle of C. elegans. Neuron. 26:583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.K., H.H. Valdivia, E.B. Maryon, P.A. Anderson, and R. Coronado. 1992. High molecular weight proteins in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans bind [3H] ryanodine and form a large conductance channel. Biophys. J. 63:1379–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kits, K.S., and H.D. Mansvelder. 1996. Voltage gated calcium channels in molluscs: classification, Ca2+ dependent inactivation, modulation and functional roles. Invert. Neurosci. 2:9–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.Y., L. Lobel, M. Hengartner, H.R. Horvitz, and L. Avery. 1997. Mutations in the α1 subunit of an L-type voltage-activated Ca2+ channel cause myotonia in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 16:6066–6076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.A., C.H. Wu, J.H. Levine, and H. Berg. 1980. Levamisole-resistant mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans appear to lack pharmacological acetylcholine receptors. Neuroscience. 5:967–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryon, E.B., R. Coronado, and P. Anderson. 1996. unc-68 encodes a ryanodine receptor involved in regulating C. elegans body-wall muscle contraction. J. Cell Biol. 134:885–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryon, E.B., B. Saari, and P. Anderson. 1998. Muscle-specific functions of ryanodine receptor channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci. 111:2885–2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire, S.L., E. Jorgensen, and H.R. Horvitz. 1993. a. Genes required for GABA function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 364:334–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire, S.L., E. Jorgensen, J. Kaplan, and H.R. Horvitz. 1993. b. The GABAergic nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 364:334–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill, J.A., and S.C. Cannon. 1999. Effects of mutations causing hypokalaemic periodic paralysis on the skeletal muscle L-type Ca2+ channel expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J. Physiol. 520:321–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, J.E., and E.M. Jorgensen. 1999. One GABA and two acetylcholine receptors function at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. Nat. Neurosci. 2:791–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbluth, J. 1965. Ultrastructure of somatic muscle cells in Ascaris lumbricoides. II. Intermuscular junctions, neuromuscular junctions, and glycogen stores. J. Cell Biol. 26:579–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakube, Y., H. Ando, and H. Kagawa. 1997. An abnormal ketamine response in mutants defective in the ryanodine receptor gene ryr-1 (unc-68) of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mol. Biol. 267:849–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeer, J.M., R.I. Norman, and D.B. Satelle. 1996. Invertebrate voltage-dependent calcium channel subtypes. Biol. Rev. 71:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, T., H. Takeshima, A. Mikami, V. Flockerzi, H. Takahashi, K. Kangawa, M. Kojima, H. Matsuo, T. Hirose, and S. Numa. 1987. Primary structure of the receptor for calcium channel blockers from skeletal muscle. Nature. 328:313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillotson, D. 1979. Inactivation of Ca conductance dependent on entry of Ca ions in molluscan neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 76:1497–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent, C., N. Tsung, and H.R. Horvitz. 1983. Egg-laying defective mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 104:619–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisblat, D.A., L. Byerly, and R.L. Russell. 1976. Ionic mechanisms of electrical activity in somatic muscle of the nematode Ascaris lumbricoides J. Comp. Physiol. 111:93–113. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.G., E. Southgate, J.N. Thomson, and S. Brenner. 1976. The structure of the ventral nerve cord of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol Sci. 275:327–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J.G., E. Southgate, J.N. Thomson, and S. Brenner. 1986. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol Sci. 275:327–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.E., and R.H. Waterston. 1994. Genes critical for muscle development and function in Caenorhabditis elegans identified through lethal mutations. J. Cell Biol. 124:475–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W.B. 1988. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. pp. 1–16, 281–336.

- Yamaguchi, H., J.N. Muth, M. Varadi, A. Schwartz, and G. Varadi. 1999. Critical role of conserved proline residues in the transmembrane segment 4 voltage sensor function and in the gating of L-type calcium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:1357–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]