Abstract

INTRODUCTION

It is essential that higher surgical trainees (HSTs) obtain adequate emergency operative experience without compromising patient outcome. The aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of patients operated by HSTs with those operated by consultants and to look at the effect of consultant supervision.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective analysis of 362 patients who underwent urgent colorectal surgery was performed. The primary outcome was 30-day mortality. Secondary outcomes were intra-operative and postoperative surgery, specific and systemic complications, and delayed complications.

RESULTS

Comparison of the patients operated by a consultant (n = 190) and a HST (n = 172) as the primary surgeon revealed no significant difference between the two groups for age, gender, ASA status or indication for surgery. There was a difference in the type of procedure performed (left-sided resections: consultants 122/190, HST 91/172; P = 0.050). There was no difference between the two groups for the primary and secondary outcomes. However, HSTs operating unsupervised performed significantly fewer primary anastomoses for left-sided resections (P =0.019) and had more surgery specific complications (P = 0.028) than those supervised by a consultant.

CONCLUSIONS

HSTs can perform emergency colorectal surgery with similar outcomes to their consultants, but adequate consultant supervision is vital to achieving these results.

Keywords: Supervision, Training, Colorectal surgery, Emergency surgery

Surgical training in the UK, as in other specialties, has recently been the source of increased interest and activity. The changes that are being introduced as a result of Modernising Medical Careers and the European Working Time Directive are shortening training and time spent by specialist registrars in the operating theatre. This ultimately reduces the number of operations performed and the level of competence achieved by surgical trainees.1 It is, therefore, vital to optimise the training opportunities that present themselves.

Emergency and urgent colorectal surgery accounts for a large proportion of the general surgery on-call workload. However, it is high-risk surgery, with a high peri-operative morbidity and mortality. It is, therefore, important to ensure that, if this surgery is being performed by higher surgical trainees (HSTs), it is safe for them to do so. There is a gap in the literature regarding this aspect of surgical care. The aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of patients undergoing urgent colorectal surgery by consultants and HSTs.

Patients and Methods

Details of patients who underwent urgent colorectal surgery at a busy district general hospital in the West Midlands were retrospectively collected for a 5-year period (June 1998 to June 2003). Patients were identified, through the hospital coding department, by selecting patients who had had operations consistent with emergency and urgent colorectal surgery. The resulting list was then analysed for the coded diagnoses and appropriate notes selected for inclusion in the study. Based on codes for operation performed and diagnosis, 575 patients were identified who appeared to fit the intended population and 90.26% (519) of these notes were obtained. After initial screening, 157 patients were excluded due to incorrect coding or incomplete data.

Data were collected regarding patient demographics, disease process, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, indication for surgery, procedure performed, grade of operating surgeon and their assistant, along with short- and long-term outcome (survival and complications) in two groups of patients – those who were operated on by consultants and those operated on by HSTs. This information was then collated using an electronic data capture system called ‘Formic’. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Univariate analyses were performed using Chi-square and Mann-Whitney tests where appropriate. Multivariate analyses were performed using the logistic regression method.

The 30-day mortality was used as the primary outcome measure. Intra-operative complications, surgery-specific and systemic postoperative complications and delayed complications were used as secondary outcomes.

Results

In total, 362 patients for whom there was complete data were included. Similar numbers were operated on by consultants (190 patients; 52.5%) and HSTs (172 patients; 47.5%). Colorectal cancer and diverticular disease were the most common pathologies encountered (294 patients), accounting for 81.2% of the cohort. A total of 307 (84.82%) patients had their operation within 48 h of decision to operate. The majority of the remaining 55 (15.19%) were treated as urgent patients and kept until an appropriate elective list was available, when consultants were more likely to operate (67.27%).

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients operated on by the two groups. The distribution of age, sex, clinical presentation and ASA grade were equal between the two groups. There was a significant difference in the pathology operated on by the two groups (P = 0.037) as more patients with inflammatory bowel disease had their operation performed by a consultant.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

| Consultant (n = 190) | Registrar (n = 172) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female ratio | 83/107 | 87/85 | 0.206a |

| Age (years) – median, mean (range) | 68, 71 (19–64) | 69, 73 (6–94) | 0.398b |

| Indication for surgery | |||

| Obstruction | 92 (48.4) | 92 (53.5) | |

| Perforation | 56 (29.5) | 52 (30.2) | 0.321b |

| Abscess | 14 (7.4) | 13 (7.6) | |

| Others | 28 (14.7) | 16 (9.3) | |

| Pathology | |||

| Colorectal cancer | 96 (50.5) | 92 (53.5) | |

| Diverticular disease | 55 (28.9) | 51 (29.7) | 0.037b |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 20 (10.5) | 4 (2.3) | |

| Other | 19 (10) | 25 (14.5) | |

| Tumour stage | |||

| Dukes'A | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Dukes'B | 28 (29.2) | 35 (38) | 0.583b |

| Dukes' C/D | 54 (56.3) | 43 (46.7) | |

| Unrecorded | 13 (13.5) | 13 (14.1) | |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists | |||

| I E | 20 (14.2)* | 30 (20.1)* | |

| II E | 51 (36.2)* | 59 (39.6)* | |

| III E | 35 (24.8)* | 39 (26.2)* | 0.117b |

| IV E | 24 (17)* | 11 (7.4)* | |

| V E | 10 (7.1)* | 9 (6)* | |

| Unrecorded | 49 | 23 | |

| Operation performed | |||

| Defunctioning procedure | 10 (5.3) | 8 (4.7) | |

| Hartmann's procedure | 75 (39.5) | 60 (34.9) | |

| L colon resection & anastomosis | 47 (24.7) | 31 (18) | 0.050b |

| R colon resection & anastomosis | 49 (25.8) | 64 (37.2) | |

| Other | 9 (4.7) | 9 (5.2) | |

Figures are number and (percentage) unless stated.

Percentage of those recorded.

P-values – Mann-Whitney test

χ2 test.

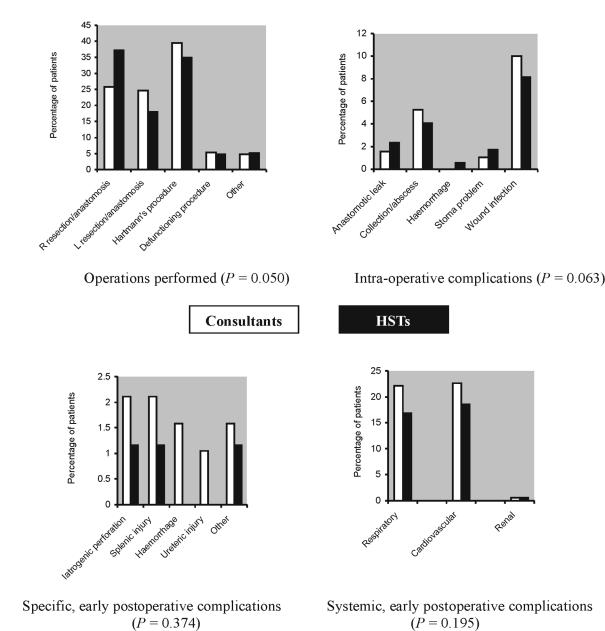

Figure 1A displays the types of operation performed during the study. This demonstrates a statistically significant variation (P = 0.050) between the two groups of surgeons. It apparent that HSTs were more likely to perform right-sided resections than their consultants and, more importantly, less likely to perform a primary anastomosis following a left-sided resection.

Figure 1.

Operation and outcomes of the patients.

The 30-day mortality was 33/190 (17.4%) for the consultants and 25/172 (14.5%) for the HSTs. In this cohort, the grade of surgeon was not a determinant of 30-day mortality on univariate or multivariate analysis (P = 0.278). On further analysis, the only factor that was found to be a predictor of 30-day mortality was the patient's ASA status.

Figure 1B–D shows the results of the secondary outcome measures. In Figure 1B, it appears that the consultant group had more intra-operative complications, although this did not quite reach statistical significance. Other than this, secondary outcomes were statistically comparable in the two groups.

Importantly, subgroup analysis revealed that there were differences between the patients when consultants supervised trainees and when they did not (as documented in the operation note). Colorectal surgeons were significantly more likely to supervise trainees as compared to other sub-specialties, being involved in 41 (60.29%) of the 68 consultant-supervised procedures (P = 0.010).

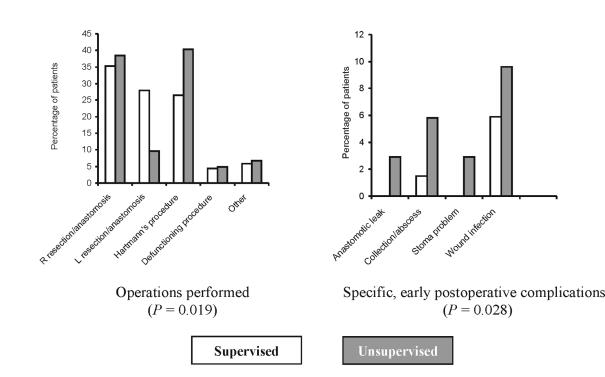

While the patient demographics, ASA grade, presenting complaint and underlying pathology were all statistically comparable (Table 2), there was a variation in the type of procedures performed, as shown in Figure 2A (P = 0.019). This specifically shows that, if unsupervised, trainees were far less likely to perform a primary anastomosis following a left-sided resection than if their consultant was scrubbed with them.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and operative outcomes of patients undergoing emergency colorectal surgery when HSTs were the lead surgeon

| Supervised (n = 68) | Unsupervised (n = 104) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation | |||

| Obstruction | 36 (52.9) | 56 (53.8) | |

| Perforation | 16 (23.5) | 35 (33.7) | 0.142 |

| Abscess | 6 (8.8) | 7 (6.7) | |

| Others | 10 (14.7) | 6 (5.8) | |

| Pathology | |||

| Colorectal cancer | 39 (57.3) | 53 (51.0) | |

| Diverticular disease | 21 (30.9) | 30 (28.8) | 0.677 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 2 (2.9) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Other | 6 (8.8) | 19 (18.3) | |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists | 0.979 | ||

| Operation performed | |||

| Defunctioning procedure | 3 (4.4) | 5 (4.8) | |

| Hartmann's procedure | 18 (26.5) | 42 (40.4) | |

| L colon resection & anastomosis | 19 (27.9) | 10 (9.6) | 0.979 |

| R colon resection & anastomosis | 24 (35.3) | 40 (38.5) | 0.019 |

| Other | 4 (5.9) | 7 (6.7) | |

| Intraoperative complications | 2 (2.9) | 5 (4.8) | 0.925 |

| Specific postoperative complications | |||

| Anastomotic leak | 0 | 3 (2.9) | |

| Collection/abscess | 1 (1.5) | 6 (5.8) | 0.028 |

| Stoma problem | 0 | 3 (2.9) | |

| Wound infection | 4 (5.9) | 10 (9.6) | |

| Systemic complications | 24 (35.3) | 45 (43.3) | 0.488 |

| Long-term complications | 18 (26.5) | 20 (19.2) | 0.234 |

| 30-day mortality | 9 (13.2) | 16 (15.8) | 0.826 |

Figures are number and (percentage) unless stated.

P-values – χ2 test.

Figure 2.

Subgroup analysis of HST data.

Also, although there were no differences between the cases that were supervised and those that were not in terms of 30-day mortality and systemic complications (Table 2), there was a significant difference in the number of specific postoperative complications (P = 0.028). In this subgroup, anastomotic leaks and stoma-related problems were only seen in patients who did not have a consultant present in theatre. Wound and intra-abdominal infections were also more prevalent in this group. These findings are highlighted in Figure 2B.

Discussion

The results of this study have demonstrated comparable outcomes for patients undergoing urgent colorectal surgery performed by consultants and higher surgical trainees. However, the data highlight the importance of consultant supervision in attaining these results. It also shows that it is only with consultants present that a high proportion of primary anastomoses are performed following a left-sided resection. This is important because there is now mounting evidence to show a more positive outcome, especially regarding postoperative quality of life, and no increase in mortality associated with primary anastomosis over Hartmann's procedure.2–5

This is the first study in recent times to look at the outcomes of all emergency colorectal surgery as performed at a district general hospital (DGH). Other studies have shown similar results between consultants and HSTs in a wide range of surgical practice (inguinal hernia surgery,6 vascular surgery,7–9 laparoscopic cholecystectomy,10 breast surgery,11 and elective colorectal cancer surgery12), but most of these studies have involved intense consultant supervision or have not looked at the implications of supervision.

We have shown that it is possible for HSTs to perform urgent colorectal surgery in a DGH setting to an equivalent standard to their consultants. This should offer some reassurance to patients and trainers alike that a good outcome can be expected following surgery by trainees and that training is not an impediment to service.

It is interesting to note that colorectal specialists were more likely to supervise trainees in theatre for this type of surgery than non-colorectal specialists. Perhaps non-specialist consultants feel that the HSTs actually have more up-to-date experience than they do in dealing with such cases? However, all the consultants involved in this study were trained in the pre-Calman era and should have a broad base of experience to draw from. Also, results that we have previously presented13 have shown no difference in the outcome of surgery for these patients when comparing colorectal and non-colorectal specialists. Instead, it seems most likely that colorectal consultants feel more confident about training on these cases and like to ensure good results with their colorectal emergencies. This lends strength to the argument that such cases should pass to a colorectal specialist on the day after admission, as it provides HSTs with more exposure with consultant supervision.

Trainees actually appeared to have less intra-operative complications than their trainers, although these numbers were small and did not reach statistical significance. This unexpected disparity probably relates to the different case mix (e.g. more right-sided resections in the trainee group) and pathologies (e.g. more inflammatory bowel disease in the consultant group) operated on by the two groups. Another explanation could be that, when complications occur, the consultants would take over, thus being documented as the lead surgeon role in the operative notes.

The Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality14 highlighted the importance of case selection and consultant supervision (both during and after surgery) on operative outcome from large bowel surgery. Our subgroup analysis has highlighted the same problem almost a decade later. The Scottish Audit was performed before Calman reforms were introduced and included senior registrars as trainees. The HSTs in our study represent a more junior cohort of surgeons with less experience. Supervision is, therefore, a more critical requirement now than when it was previously concluded. Our findings also reflect those reported by Zorcolo et al.2 in 2003, who found that unsupervised trainees performed less primary anastomosis and had worse morbidity and mortality outcomes. However, their study was performed in a large teaching hospital and the study was primarily to look at the effects of sub-specialisation in surgery.

Consultant supervision in theatre was also a concern in the 1997 National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths (NCEPOD).15 NCEPOD has since reported an increase in consultant presence in theatre during emergency surgery, subsequent to their recommendations.16 This probably represents policies with-in many NHS trusts to excuse consultants of their routine duties whilst on call, allowing them more freedom to oversee the management of emergency cases. In view of our findings, this type of policy should be encouraged in DGHs.

We were unable to ascertain the level of seniority of HSTs in our cohort, but have demonstrated that trainees are capable of operating to high standards in a DGH given adequate supervision. Consultants were documented as primary surgeon in over 50% of cases here, which may represent some lost opportunities to train. Current initiatives being introduced in the UK are bringing down training times. In some areas of surgery the shortage of ‘on-the-job’ experience can be partly overcome by skills training outside of theatre. However, for urgent colorectal surgery there are no such bench models. We should, therefore, be looking to optimise and use opportunities as they present themselves; it is more critical now than when the Calman changes were first introduced.17 This way we can make the new systems work and continue producing high-quality surgeons for the future.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been presented, in part, as a poster at the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland meeting in Glasgow, April 2005 (Hawkins W, Moorthy K, Yoong K, Patel R. Outcomes of patients undergoing emergency colorectal surgery by higher surgical trainees are comparable to those operated by consultants. Br J Surg 2005; 92 [Suppl. 1]: 91). It is also related to a short paper presentation at the same meeting (Hawkins W, Moorthy K, Yoong K, Patel R. Is there a valid need for the establishment of a dedicated emergency colorectal service in a district general hospital? Br J Surg 2005; 92 [Suppl. 1]: 135).

The authors would like to thank Miss Samantha Fitter, Russells Hall Hospital Audit Department for her help in preparing this paper.

References

- 1.Beard JD, Jolly BC, Newble DI, Thomas WEG, Donnelly J, Southgate LJ. Assessing the technical skills of surgical trainees. Br J Surg. 2005;92:778–82. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zorcolo L, Covotta L, Carlomagno N, Bartolo DCC. Toward lowering morbidity, mortality and stoma formation in emergency colorectal surgery: the role of specialization. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1461–8. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mealy K, Salaman A, Arthur G. Definitive one-stage emergency large bowel surgery. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1216–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800751224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alanis A, Papanicolau GK, Tadros RR, Fielding LP. Primary resection and anastomosis for treatment of acute diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:933–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02552268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biondo S, Jaurrieta E, Jorba R, Moreno P, Farran L, Borobia F, et al. Intraoperative colonic lavage and primary anastomosis in peritonitis and obstruction. Br J Surg. 1997;84:222–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robson AJ, Wallace CG, Sharma AK, Nixon SJ, Paterson-Brown S. Effects of training and supervision on recurrence after inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2004;91:774–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naylor AR, Thompson MM, Varty K, Sayers RD, London NJ, Bell PR. Provision of training in carotid surgery does not compromise patient safety. Br J Surg. 1998;85:939–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pai M, Handa A, Hands L. Adequate vascular training opportunities can be provided without compromising patient care. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:524–7. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans SM, Adam DJ, Murie JA, Jenkins AM, Ruckley CV, Bradbury AW. Training in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair: 1987-1997. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;18:430–3. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1999.0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imhof M, Zacherl J, Rais A, Lipovac M, Jakesz R, Fuegger R. Teaching laparoscopic cholecystectomy: do beginners adversely affect the outcome of the operation? Eur J Surg. 2002;168:470–4. doi: 10.1080/110241502321116479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moorthy K, Asopa V, Wiggins E, Callam M. Is the reexcision rate higher if breast conservation surgery is performed by surgical trainees? Am J Surg. 2004;188:45–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh KK, Aitken RJ. Outcome in patients with colorectal cancer managed by surgical trainees. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1332–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkins WJ, Moorthy K, Yoong K, Patel R. Is there a valid need for the establishment of a dedicated emergency colorectal service in a district general hospital? Br J Surg. 2005;92(Suppl 1):135. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macarthur DC, Nixon SJ, Aitken RJ. Avoidable deaths still occur after large bowel surgery. Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality, Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Br J Surg. 1998;85:80–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Who operates when? London: NCEPOD; 1997. National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths 1995–96. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Who operates when? II. London: NCEPOD; 2003. The 2003 Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hargeaves DH. A training culture in surgery. BMJ. 1996;313:1635–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]