Abstract

DNA topoisomerase (topo) II catalyses topological genomic changes essential for many DNA metabolic processes. It is also regarded as a structural component of the nuclear matrix in interphase and the mitotic chromosome scaffold. Mammals have two isoforms (α and β) with similar properties in vitro. Here, we investigated their properties in living and proliferating cells, stably expressing biofluorescent chimera of the human isozymes. Topo IIα and IIβ behaved similarly in interphase but differently in mitosis, where only topo IIα was chromosome associated to a major part. During interphase, both isozymes joined in nucleolar reassembly and accumulated in nucleoli, which seemed not to involve catalytic DNA turnover because treatment with teniposide (stabilizing covalent catalytic DNA intermediates of topo II) relocated the bulk of the enzymes from the nucleoli to nucleoplasmic granules. Photobleaching revealed that the entire complement of both isozymes was completely mobile and free to exchange between nuclear subcompartments in interphase. In chromosomes, topo IIα was also completely mobile and had a uniform distribution. However, hypotonic cell lysis triggered an axial pattern. These observations suggest that topo II is not an immobile, structural component of the chromosomal scaffold or the interphase karyoskeleton, but rather a dynamic interaction partner of such structures.

Keywords: DNA topoisomerase II; cell cycle; nucleolus; nuclear matrix; chromosomal scaffold

Introduction

Type II topoisomerases are enzymes able to relax, (un)knot, and (de)catenate closed circular DNA in vitro, properties required for DNA replication, chromosome condensation, and the segregation of daughter chromatids (Wang, 1996). DNA topoisomerase (topo)* II was previously recognized as the major nonhistone protein component of the chromosome scaffold (Earnshaw et al., 1985; Gasser et al., 1986) and the interphase nuclear matrix (Berrios et al., 1985), insoluble nuclear structures believed to play an architectural role. In keeping with this, topo II was detected by immunocytochemistry along the longitudinal axes of gently expanded chromosomes (Earnshaw and Heck, 1985; Gasser et al., 1986) and shown to bind preferentially to AT-rich DNA elements believed to specify the bases of chromatin loops (Adachi et al., 1989). As a result, topo II is considered to play a structural role in chromosome organization in addition to its enzymatic functions (Adachi et al., 1991). However, this view is not undisputed (Hirano and Mitchison, 1993), and lately the existence of a nuclear matrix in the living cell nucleus has been questioned altogether (Pederson, 2000).

Another open issue regards the biological roles of the two isoforms of mammalian topo II (α and β), which are similar in primary structure, have almost identical catalytic properties in vitro (Austin and Marsh, 1998), and are both able to complement topo II function in ΔTop2 strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Jensen et al., 1996a). In particular, the latter observation has argued against isoform-specific biological functions of topo IIα and IIβ. However, this might not be conclusive because yeast has only one form of topo II and might not utilize the mammalian enzymes in an isoform-specific manner.

Research on functions of mammalian topo II isoforms in their native environment has been impeded by various obstacles. For example, it has not been possible to unambiguously clarify their subnuclear localization. It has been established that topo IIα binds to condensed chromosomes and accumulates at centromeres in metaphase (Rattner et al., 1996; Sumner, 1996), but it is unclear whether the enzyme is distributed in the chromosome arms in a uniform (Boy de la Tour and Laemmli, 1988) or axial manner (Earnshaw and Heck, 1985; Gasser et al., 1986; Taagepera et al., 1993; Saitoh and Laemmli, 1994; Rattner et al., 1996; Sumner, 1996). The mitotic localization of topo IIβ is even less clear. Several investigations indicate that it is cytoplasmic during cell division (Petrov et al., 1993; Chaly et al., 1996; Meyer et al., 1997), whereas others also describe its association with chromosomes (Taagepera et al., 1993; Sugimoto et al., 1998). All of these studies were restricted to fixed or fractionated specimen, and the disparate results have in part been blamed on the use of different staining techniques and antibodies (Chaly and Brown, 1996; Warburton and Earnshaw, 1997; Austin and Marsh, 1998). The most comprehensive study on topo II in living cells is based on microinjection of purified, fluorescently tagged topo II from Drosophila melanogaster into living embryos, and has revealed a dynamic but homogenous chromosomal distribution of the enzyme (Swedlow et al., 1993). Comparable in vivo studies of the mammalian topo II isoforms using stable heterologous expression of GFP chimera are missing, probably because overexpression of topo IIα induces apoptotic cell death (McPherson and Goldenberg, 1998). On the other hand, transient expression of topo IIα fused to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) has not yielded conclusive data from cells in interphase, although it allowed confirmation of the enzyme's association with mitotic chromosomes (Mo and Beck, 1999). Reports on the disposition of topo IIβ in living cells are not available.

Here, we achieved constitutive expression of active GFP chimera of human topo II at physiological levels by a balanced coexpression with a selection marker from bicistronic transcripts. Thus, we could monitor dynamic relocations of both isozymes during mitosis and assess their localization and mobility during the whole cell cycle. Our data are suited to address most of the issues summarized above.

Results

Constitutive expression of active topo II–GFP chimera in 293 cells

To avoid the deleterious effects of topo II overexpression (McPherson and Goldenberg, 1998), we used a vector, allowing a balanced expression of a selection marker and a second (potentially harmful) protein via transcription of bicistronic mRNA (Mielke et al., 2000). We transfected human embryonal 293 kidney cells with such constructs, bearing in the first cistron hybrid genes of topo IIα or IIβ fused at their C termini to GFP, and in the second cistron the selection marker puromycin-N-acetyltransferase. Significantly less puromycin-resistant cell clones emerged from transfection with topo II–GFP than from transfection with the GFP gene alone, attesting to a narrow tolerance margin for transgenic expression of topo II. However, cell lines supporting constitutive expression of topo IIα–GFP or topo IIβ–GFP had growth rates and morphologies similar to untransfected cells or cells expressing GFP alone. This suggested a quasi physiological expression of the GFP-tagged topo II species suitable for fluorescence studies in living cells, provided that the fusion proteins were active, not overexpressed, and colocalized with their endogenous counterparts. Control experiments addressing these issues are summarized in Fig. 1.

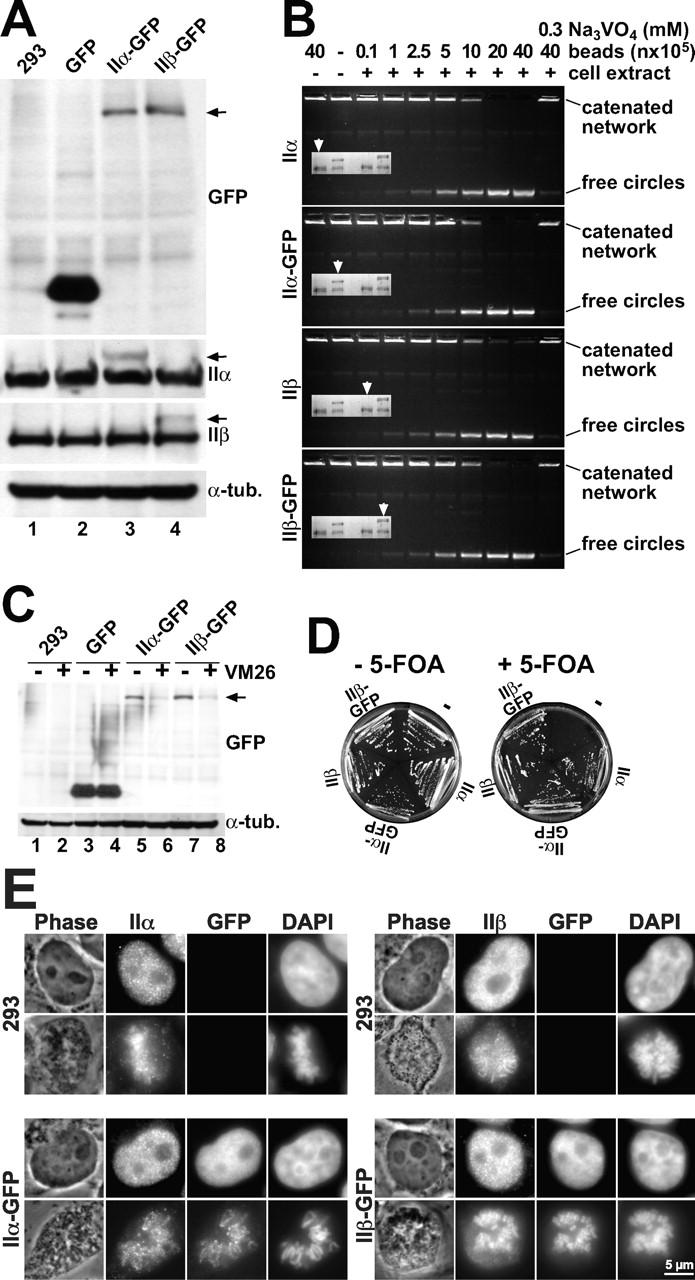

Figure 1.

Characterization of HEK 293 cells expressing topo II–GFP. (A) Western analysis of untransfected 293 cells and cells expressing GFP, topo IIα–GFP, or topo IIβ–GFP. Blots were probed with GFP antibodies (top), or antibodies against human topo IIα or IIβ (middle panels), or antibodies against α-tubulin serving as loading control (bottom). Arrowheads on the right margin indicate positions of topo II–GFP chimera. (B) DNA decatenation activity of GFP-fused and endogenous topo II. GFP-directed immunoprecipitates from cells expressing topo IIα–GFP or topo IIβ–GFP and immunoprecipitates from untransfected cells directed at topo IIα or IIβ were subjected to serial dilution and assessed for kDNA decatenation. SDS-PAGE of the immunoprecipitates is shown four times in the inserts with arrowheads identifying those lanes that correspond to the respective decatenation assay. (C) Topo II immunoband depletion assay. The same cell lines as in Fig. 1 A were cultured 1 h in medium containing 200 μM teniposide (+ VM 26) or in plain medium (− VM 26). Cells were then lysed, subjected to Western blotting, and the blots were probed with GFP-antibodies (top). The position of topo II–GFP is indicated on the right margin by an arrowhead. (D) Yeast complementation assay. The S. cerevisiae strain BJ201 carrying a disrupted endogenous TOP2 gene which is substituted by the S. pombe Top2 gene on a URA3-based plasmid, was transformed with LEU2 plasmids carrying either the TPI-promoter alone (−) or TPI-promoted topo II cDNAs encoding topo IIα, topo IIα-GFP, topo IIβ, and topo IIβ–GFP, respectively. After growth on selective plates (without Leu), single clones were streaked on plates with 5-FOA (right) to select for clones that had lost the S. pombe topo II–expressing plasmid. Plates without 5-FOA served as a control (left). Mitotic growth of cells transformed with the topo II expression plasmids on 5-FOA plates indicates that the essential topo II activity is likewise provided by GFP-tagged and untagged versions of human topo II isoforms. (E) Colocalization of GFP fusion proteins with endogenous topo IIα and IIβ by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Untransfected 293 cells (top) and topo IIα- (bottom, left) or topo IIβ–GFP-expressing cells (bottom, right) were grown on microscopic slides, PFA-fixed, permeabilized, and double stained with isoform-specific topo II antibodies (columns IIα and β, respectively) and DAPI. Corresponding images of phase contrast (Phase) and green fluorescence (GFP) are shown. From each staining combination one representative cell in interphase (top image) and pro-/metaphase (bottom image) is shown.

We performed Western blot analyses of the cell lines expressing topo IIα–GFP (Fig. 1 A, lane 3) and topo IIβ–GFP (Fig. 1 A, lane 4). Untransfected cells (Fig. 1 A, lane 1) and GFP-expressing cells (Fig. 1 A, lane 2) served as controls. To assess the integrity of the fusion proteins and to compare their relative expression levels, the blots were probed with GFP antibodies (Fig. 1 A, top panel). In transfected cells (Fig. 1 A, lanes 3 and 4), chimeric topo IIα and IIβ were detected as single protein bands of the expected size (arrow), but were absent in untransfected cells (Fig. 1 A, lane 1) and in cells expressing GFP alone (Fig. 1 A, lane 2). Thus, we could exclude rearrangements of the chimeric genes and ascertain that green fluorescence of the cells was due to full-length topo II–GFP chimera. Topo IIα–GFP and topo IIβ–GFP appeared to be expressed in similar amounts (Fig. 1 A, compare lanes 3 and 4), allowing a comparison of data between these cell lines.

To compare expression levels of GFP-fused topo II isozymes with the endogenous enzymes, blots were probed with isoform-specific antibodies against topo IIα (Fig. 1 A, second panel) or β (Fig. 1 A, third panel). The GFP chimera could clearly be discriminated from the corresponding endogenous enzymes as additional bands of slower migration (Fig. 1 A, arrows). From comparison within each lane, it became evident that they were expressed at much lower levels than the endogenous proteins. Moreover, the levels of untagged topo IIα and IIβ were the same in transfected and untransfected cells, indicating that the additional expression of GFP-tagged enzymes did not alter endogenous topo II expression.

Because protein functions could be disrupted by fusion to GFP, we wanted to ascertain that the topo II–GFP chimera had the same activity as the endogenous enzymes. We addressed this question by quantitative comparisons of the DNA decatenation activities of endogenous and GFP-fused enzymes isolated by immunoprecipitation. GFP-directed immunoprecipitates from cells expressing GFP chimera contained GFP-fused and unfused topo II in equal proportions (Fig. 1 B, inserts, lanes 2 and 4), suggesting heterodimers of GFP-fused and endogenous topo II. Upon comparing the DNA-decatenation activity of these mostly heterodimeric immunoprecipitates with similar amounts of endogenous enzymes obtained from untransfected 293 cells by topo II–directed immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1 B, inserts, lane 1 and 2, respectively), it appeared that the GFP chimera of topo IIα (Fig. 1 B, second panel) and β (Fig. 1 B, bottom) had the same activity as their endogenous counterparts (Fig. 1 B, top and third panel, respectively), and could likewise be inhibited by the ATPase-inhibitor orthovanadate (Fig. 1 B, outmost lanes on the right). Thus, fusion to GFP did not alter the catalytic properties of the enzymes. In addition, to ascertain that the GFP-fused enzymes were also active in the cells, we employed immunoband depletion (Fig. 1 C), which is based on the fact that the transient, covalent complex between topo II and genomic DNA is stabilized by specific topo II poisons (Liu, 1989). As a consequence, topo II–specific signals are depleted in Western analyses due to a retention of topo II–DNA complexes in the gel slots. Untransfected and transfected 293 cells were treated with the topo II poison teniposide (VM 26), and subjected to immunoblotting using GFP antibodies (Fig. 1 C, top). Obviously, the treatment depleted topo II–fused GFP bands from the blots (Fig. 1 C, compare lanes 5 and 6, and lanes 7 and 8). The extent of depletion was similar to that of endogenous topo II (unpublished data). GFP alone or α-tubulin (Fig. 1 C, compare lanes 3 and 4, top and bottom, respectively) were not depleted by VM 26, attesting to the specificity of the assay. These results confirmed that topo II–GFP chimera were as active as endogenous topo II because they formed the same amount of catalytic intermediates in the genome of the transfected cells.

To judge the global functionality of topo II–GFP in complex cellular processes such as mitosis, we tested complementation of topo II function in S. cerevisiae topo II deletion strains (Jensen et al., 1996b). This assay (Fig. 1 D) demonstrated that GFP chimera of human topo IIα and IIβ were fully capable of supporting the mitotic growth of Δtop2 yeast upon eradication of the endogenous salvage plasmid encoding Schizosaccharomyces pombe topo II (+5-fluoroorotic acid [FOA]), whereas cell growth was abolished in the absence of an additional topo II construct. Apparently, complementation by GFP chimera was as good as by untagged topo II. Thus, the functionality of human topo II is fully preserved in the corresponding GFP chimera.

Finally, we considered that fusion to GFP might disrupt cellular targeting of topo II. Therefore, we compared the distribution patterns of endogenous and GFP-tagged topo II by indirect immunofluorescence. Fig. 1 E shows examples of mitotic and of interphase cells labeled with isozyme-specific topo II antibodies. Untransfected cells (Fig. 1 E, top panels) gave rise to antibody-derived signals only, whereas cells expressing topo IIα–GFP (Fig. 1 D, bottom left) or topo IIβ–GFP (Fig. 1 E, bottom right) also emitted GFP fluorescence. The distribution patterns of GFP fluorescence (specific for GFP fusion proteins only) and immunofluorescence (specific for fused and endogenous enzymes) were virtually identical, attesting to the fact that the GFP chimera colocalized with their endogenous counterparts. In addition, distribution patterns of topo II in nontransfected and in topo II–GFP-expressing cells were identical (Fig. 1 D, compare top and bottom portion), making it unlikely that the GFP chimera disrupted localization of the endogenous enzymes. It should be noted that the patterns shown in Fig. 1 E do not represent the true localization of topo IIα or IIβ in living cells, because these cells were fixed and permeabilized which is known to alter the cellular distribution of topo II in an unpredictable fashion (Chaly and Brown, 1996). In fact, when we applied different protocols for permeabilization and/or fixation, we also obtained patterns different from those shown in Fig. 1 E, but in each case antibody staining and GFP fluorescence were identical. The colocalization of topo II and GFP epitopes in fixed cells shows that the cellular targeting of topo II–GFP chimera is similar to that of the endogenous enzymes. Thus, the GFP-tagged enzymes should also reflect faithfully the localization of topo II in living cells.

Distribution of topo IIα and IIβ in living cells

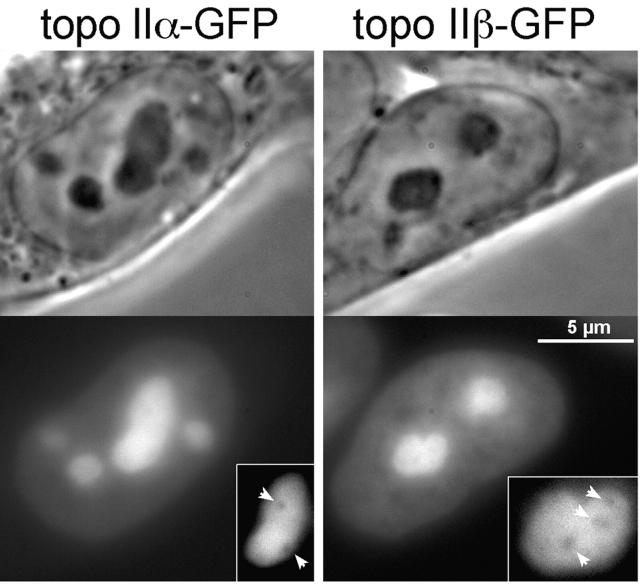

Monitoring of topo IIα–GFP and topo IIβ–GFP in living cells by GFP fluorescence revealed a very similar distribution of the isozymes in interphase nuclei (Fig. 2): both were exclusively in the nucleus, where they resided in the nucleoplasm and the nucleoli. The minor, nucleoplasmic subpopulation had a slightly uneven distribution. The major fraction of both isoforms accumulated in the nucleoli. It had a cloudy but otherwise unstructured distribution in the entire nucleolar space which distinctively excluded small globular compartments (not yet identified), imposing as dark holes within the brightly fluorescent nucleolus (Fig. 2, insert, arrows).

Figure 2.

Distribution of topo II–GFP in interphase nuclei. Phase-contrast images and corresponding green fluorescence of living 293 cells expressing topo IIα–GFP (left) and topo IIβ–GFP (right). The insert shows images of selected nucleoli subjected to twofold magnification and contrast enhancement. Arrowheads indicate areas of decreased fluorescence intensity within the nucleoli.

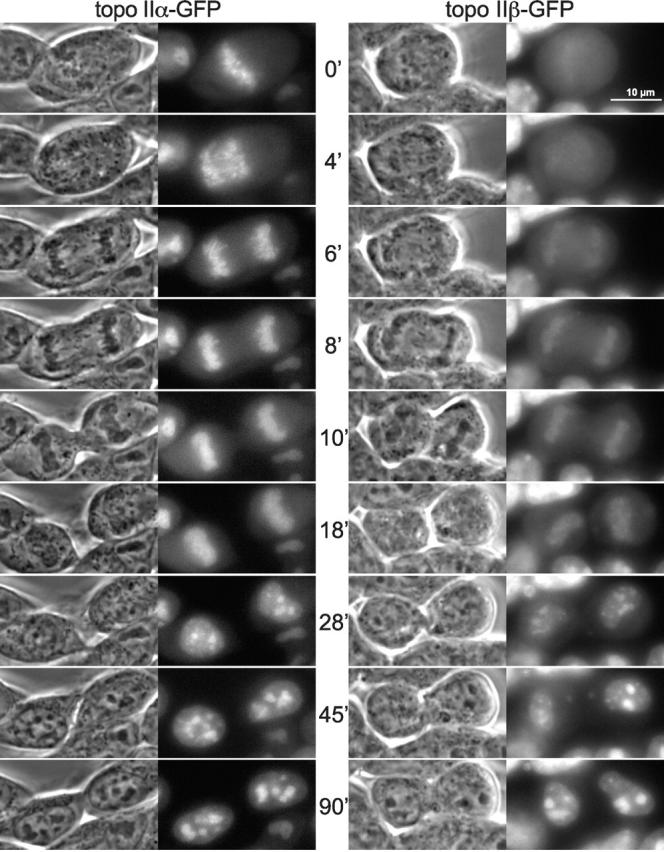

During cell division, the localization of topo II isoforms differed markedly. Fig. 3 shows time-lapsed images of topo IIα–GFP (left) and topo IIβ–GFP (right) in cells proceeding from metaphase (0′) to early G1-phase (90′) (Video 1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200112023/DC1, showing cell cycle progression from prophase through G1-phase acquired by confocal microscopy). Topo IIα–GFP was mostly chromosome-associated from metaphase until telophase (0–10 min). Chromosomal structures were distinctively labeled by the enzyme, whereas the mitotic cytosol contained only a minor fraction. In contrast, association of topo IIβ–GFP with chromosomes varied during mitosis. In metaphase (0 min), the enzyme was mostly in the cytosol; it started to associate with the chromosomes as soon as they were segregated (4 min) and continued to accumulate there until cytokinesis (18 min). From then on and throughout interphase, the two isoforms behaved similarly. During nuclear reorganization in early G1-phase (18–90 min), they concentrated in small, light–dense structures (18 and 28 min) which later on (45 and 90 min) gradually assembled into nucleoli. It is interesting to note that the patterns at early G1-phase (e.g., 28 min) resemble those of established marker proteins of prenucleolar bodies (e.g., B23; Olson et al., 2000), suggesting that both topo II isozymes participate in postmitotic reassembly of nucleoli.

Figure 3.

Time-lapse imaging of topo II isoforms during mitosis. Cells expressing either topo IIα–GFP (left) or topo IIβ–GFP (right) were grown on the microscope stage at 37°C and imaged at subsequent time points as indicated. Phase-contrast images and corresponding green fluorescence of representative cells are shown during progression from metaphase to early G1-phase. Video 1 (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200112023/DC1) shows topo II–GFP-expressing cells proceeding from prophase to early G1-phase. This image series represents a single optical section captured on a confocal microscope at intervals of 30 s.

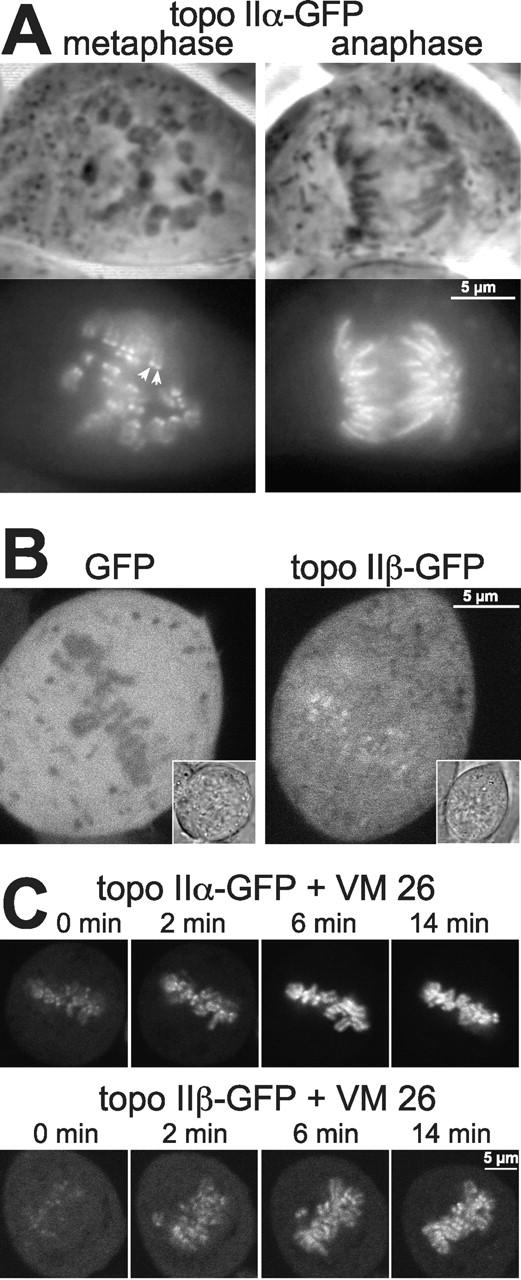

Because of the dense chromosome packing, we could not resolve the subchromosomal localization of topo IIα in metaphase plates of living cells. To overcome the problem, metaphase chromosomes were spread out by gentle mechanical compression of the cells (Fig. 4 A) which revealed a centromeric accumulation of topo IIα–GFP (Fig. 4 A, left). However, in anaphase the enzyme appeared to be evenly distributed over the whole chromosome (Fig. 4 A, right). These observations are in good agreement with previous immunohistochemical findings (Taagepera et al., 1993; Rattner et al., 1996; Sumner, 1996), supporting the idea that in metaphase (at the onset of chromatid segregation), topo IIα has its major role in separating the last catenates of centromeric DNA. It is interesting to see here how fast the enzyme becomes subsequently redistributed within the chromosome, considering the rapid progression of cells from metaphase to anaphase (Fig. 3 and Video 1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200112023/DC1).

Figure 4.

Features of topo II isoforms in mitosis. (A) Centromeric accumulation of topo IIα at metaphase is lost upon transition to anaphase. Topo IIα–GFP-expressing cells were grown on cover slides, then flattened by placing the slide with adherent cells directly onto a glass slide, and imaged directly thereafter. Representative examples of cells at metaphase (left) and anaphase (right) are presented by phase contrast (top) and corresponding green fluorescence of GFP (bottom). Arrowheads indicate an example of centromeric accumulation of topo IIα, as characterized by two pairs of dots per chromosome. (B) Topo IIβ is not excluded from mitotic chromosomes. A single high-resolution, confocal section of metaphase cells expressing either GFP alone (left) or topo IIβ–GFP (right) is shown (inserts: images of transmitted light of the same cells). (C) Topo IIα and topo IIβ accumulate on mitotic chromosomes upon treatment with VM 26. Cells expressing topo IIα–GFP (top) and IIβ–GFP (bottom) were imaged by confocal microscopy before (0 min) and at the indicated time points after the addition of 100 μM VM 26.

The data in Fig. 3 show that topo IIβ does not accumulate on chromosomes before telophase. This could either mean that the enzyme is altogether excluded from the condensing chromatin, or that a large cytoplasmic pool of topo IIβ obscures a smaller, chromosome-associated fraction. Evidence for the latter assumption came from a comparison of GFP alone and topo IIβ–GFP by high-resolution confocal microscopy of metaphase cells (Fig. 4 B). The untagged, freely diffusible protein GFP was clearly excluded from densely packed metaphase chromosomes (Fig. 4 B, left), whereas this was not the case for topo IIβ–GFP (Fig. 4 B, right). Here, the metaphase plate exhibited the same fluorescence intensity as the surrounding cytosol and was even highlighted by more intense speckles. This pattern argues against an exclusion of topo IIβ from metaphase chromosomes. It suggests that a minor fraction of the enzyme is indeed chromosome-associated at this stage of mitosis.

Further evidence for this hypothesis was obtained from metaphase cells treated with the topo II–specific drug VM 26 (Fig. 4 C). This caused a rapid redistribution of both topo IIα–GFP (Fig. 4 C, top) and topo IIβ–GFP (bottom) from the cytosol to the chromosomes, indicating that the drug efficiently trapped both isozymes on chromosomal DNA. Of interest, the VM 26–induced chromosomal accumulation of topo IIα–GFP was faster and more complete than that of topo IIβ–GFP. In summary, these data indicate that during mitosis topo IIβ has a propensity to engage in DNA turnover, but the enzyme is clearly biased to the cytosolic state. In addition, the rapid redistribution of both isoforms from the cytosol to the chromosomes after treatment with VM 26 suggests a dynamic interchange between the two populations thus identifying these enzymes as highly mobile constituents of the mitotic cell.

Mobility of topo IIα and IIβ and the effects of topo II poisons

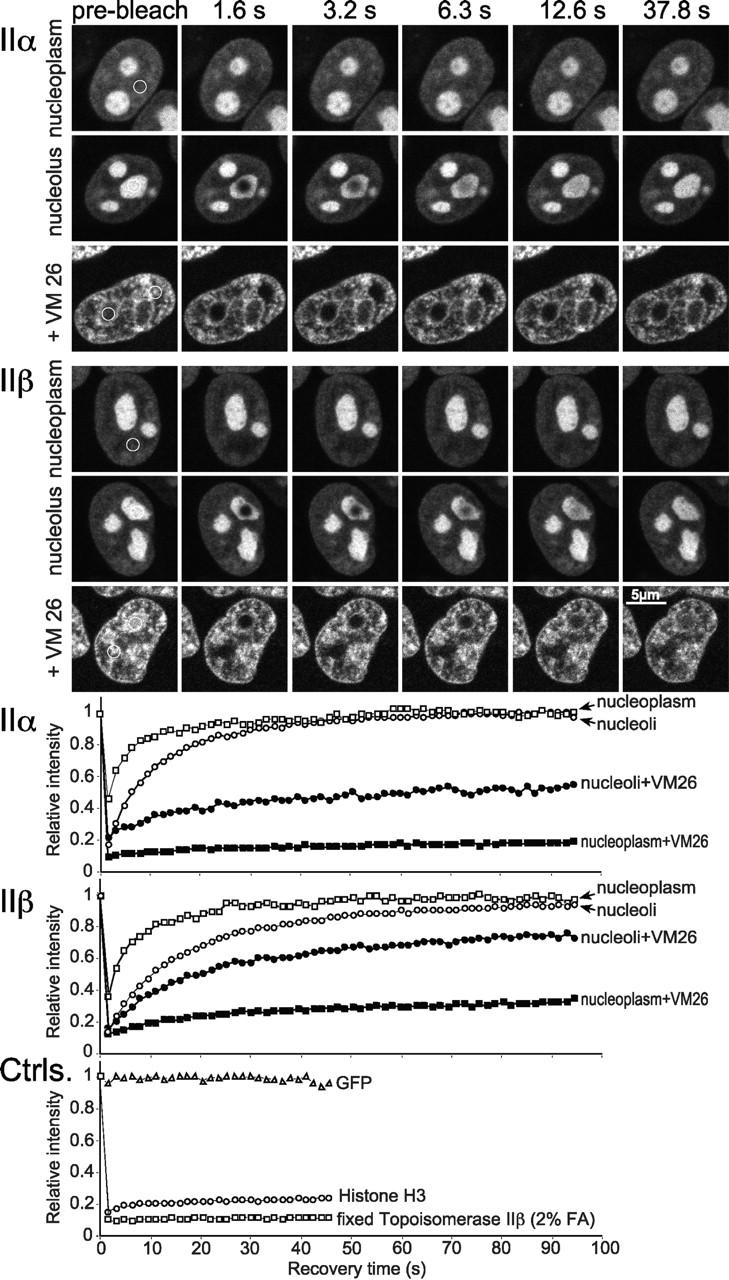

To follow up on the mobility of topo IIα and topo IIβ in living cells, we employed photobleaching techniques. Fig. 5 summarizes a series of experiments, determining the mobility of topo IIα and IIβ in interphase nuclei via kinetics of FRAP (White and Stelzer, 1999). Topo II–linked GFP fluorescence was bleached irreversibly in circular areas (Ø = 1 μm) by high-powered laser pulses and fluorescence recovery in the bleached spots as a consequence of topo II–GFP molecules moving in from unbleached areas was recorded over time. It is readily apparent from time-lapsed fluorescent images (Fig. 5, top) and quantitative plots of recovery kinetics (Fig. 5, bottom) that FRAP of a nucleoplasmic or a nucleolar area was in each compartment fast and complete for both topo II isoforms. This suggests that immobile molecules are virtually absent. Recovery kinetics of topo II–GFP were much faster than those of GFP-histone H3, a member of nucleosomal core proteins (Fig. 5, Ctrls.) known to be firmly immobilized on chromatin (Phair and Misteli, 2000). On the other hand, both topo II isozymes were by no means as freely diffusible as unfused GFP which exhibited recovery kinetics even too fast to be recorded with our experimental settings (Fig. 5, Ctrls.). Moreover, recovery of topo IIα–GFP and topo IIβ–GFP was notably slower in nucleoli (t1/2 = 6.2 and 10 s, respectively) than in the nucleoplasm (t1/2 = 1.8 and 3 s, respectively), suggesting less mobile enzyme subpopulations in the nucleoli. This, and the slight difference in mobility between the isozymes (topo IIβ was somewhat slower), raised the question of what controls topo II mobility and which role DNA interactions play in this respect. We could address this issue experimentally, as covalent topo II·DNA intermediates are stabilized by specific agents such as VM 26 (compare Figs. 1 C and 4 C). VM 26 treatment induced a profound redistribution of topo II in the nucleus which was similar for both isoforms (Fig. 5, top panels, bottom rows). Nucleoli became largely depleted, and almost the entire enzyme pool concentrated at distinct sites in the nucleoplasm, forming there a granular pattern. FRAP analysis revealed that topo II was clearly much less mobile at these granular nucleoplasmic sites. Notably, immobilization was less pronounced for topo IIβ which still exhibited a slight ascension of the recovery curve, whereas topo IIα did not. This is in agreement with previous pharmacological studies showing that topo IIβ is less sensitive to VM 26 (Drake et al., 1989). In comparison, the small amount of topo IIα and β remaining inside nucleoli after VM 26 treatment retained a much higher mobility and, here again, topo IIβ was more mobile (less affected by VM 26) than topo IIα. These data demonstrate for the first time directly that the vast majority of topo IIα and IIβ molecules present in a living cell becomes indeed trapped by VM 26 in its covalently DNA-bound intermediate state which must be relieving for oncologists, relying on this mechanism of action for tumor therapy. These findings also suggest that nuclear sites where topo II normally accumulates (Fig. 2) do not necessarily represent sites where the enzymes are most actively engaged in DNA catalysis. This is most evident in nucleoli where topo II concentration is highest (Fig. 2), enzyme mobility is lowest (Fig. 5, untreated cells), but entrapment by VM 26 is least efficient (Fig. 5, VM 26-treated cells). Thus, interaction of topo II with genomic DNA seems not to constitute the major determinant of topo II localization or mobility.

Figure 5.

FRAP analysis of topo II–GFP. Cells expressing GFP chimera of topo IIα and IIβ were bleached for 1.8 s. Images were taken before bleaching and at the indicated time points after the end of the bleach pulse. The area to be bleached is indicated by a circle in the prebleach panels. In VM 26–treated cells a nucleolar or a nucleoplasmic region was bleached simultaneously in the same cell, whereas in untreated cells each compartment was bleached in separate cells. Corresponding quantitative data of fluorescence recovery kinetics are plotted below. Fluorescence intensities in the bleached region were measured and expressed as the relative recovery over time. Values represent means from at least six individual cells and three independent experiments. Standard deviations were in each case <5% of the mean values (unpublished data). FRAP kinetics of freely diffusible GFP, chromatin-bound histone H3-GFP and formaldehyde-fixed topo IIβ–GFP served as controls.

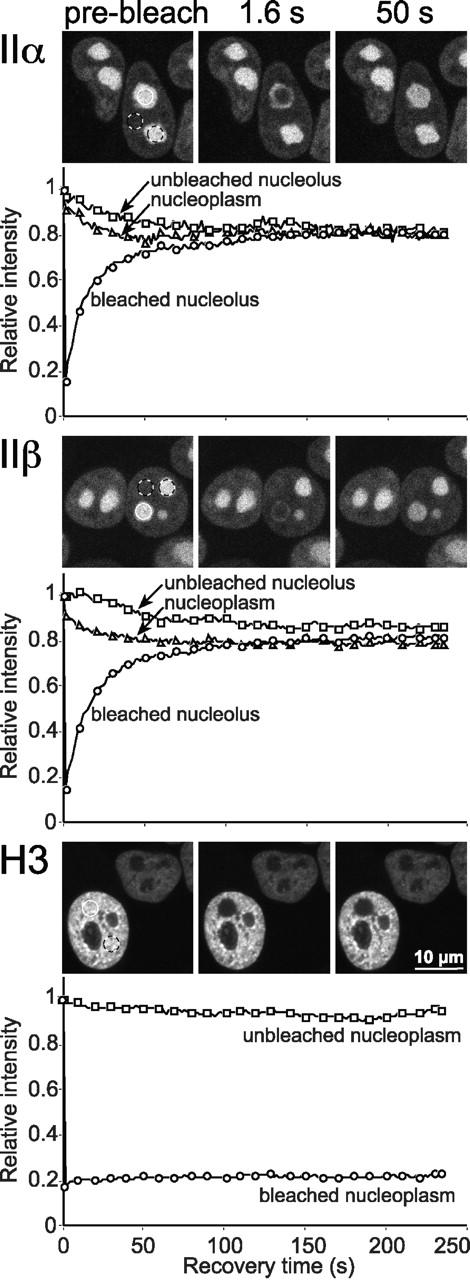

To investigate whether all topo II–GFP molecules are free to traffic between different nucleoli and between nucleoli and the nucleoplasm, we applied a combined FRAP/fluorescence loss in photobleaching (FLIP) analysis (Fig. 6). First, an entire nucleolus was bleached in a circular area (Ø = 3 μm). Subsequently, we recorded by sequential imaging scans the fluorescence recovery of the bleached nucleolus and the loss of signal intensity in an unbleached nucleolus of the same cell and in a neighboring, unbleached nucleoplasmic area. To enable a comparison of FRAP and of FLIP, quantitative data were plotted without the usually applied correction for the bleach pulse-induced, overall loss of fluorescence, giving rise to the slightly unusual drawings shown in Fig. 6. The plots for topo IIα–GFP (Fig. 6, top) and topo IIβ–GFP (Fig. 6, middle) show that in both cases the fluorescence of the bleached nucleolus recovered at the expense of the two neighboring areas which decreased by the same rate. The three curves rapidly reached equilibrium, and the equilibrium values were virtually the same, indicating that the mean fluorescence intensity of nucleoli, having completely recovered from bleaching, was identical to unbleached ones which lost a corresponding amount of fluorescence over time. Moreover, unbleached nucleoli were subjected to the same percentage loss of fluorescence intensity as the nucleoplasm. Thus, bleached topo II molecules (from the bleach spot) and unbleached ones (from the selected neighboring areas) mixed completely within the time frame of the experiment, indicating that all of them could freely move between their respective nuclear compartments. These data are in striking contrast to those obtained with the largely immobile GFP-histone H3 (Fig. 6, bottom), where fluorescence recovery in the bleach spot and fluorescence loss in the neighborhood did not converge.

Figure 6.

Exchange between nucleoplasmic and nucleolar topo II–GFP. Cells expressing GFP chimera of topo IIα, IIβ, and histone H3, respectively, were bleached and analyzed as in Fig. 5 with two exceptions: (a) A larger area (3 μm diam; white circle) was bleached to achieve a substantial loss of total cellular fluorescence. (b) The relative recovery over time in the bleach spot and the relative loss of fluorescence intensity in unbleached areas (black and white circles) is plotted below each image panel. Plotted data were not corrected for the overall loss of fluorescence induced by the bleach pulse (∼20%), to allow a quantitative comparison of signal loss in unbleached areas with signal gain in the bleached area. For greater clarity, only every tenth data point is marked by a symbol.

The free exchange of topo II between nuclear compartments was further corroborated by a conventional FLIP experiment (White and Stelzer, 1999), where nucleoli labeled by topo IIα–GFP or topo IIβ–GFP were repeatedly bleached (Fig. 7). As a consequence, all topo II–GFP fluorescence was lost from the nucleoplasm as well as from other nucleoli, indicating that all fluorescent topo II molecules were eventually hit by a bleach pulse and therefore must be exchanging rapidly between the nuclear subcompartments.

Figure 7.

FLIP analysis of interphase topo II–GFP. Nucleoli of cells expressing topo IIα–GFP or topo IIβ–GFP were repeatedly bleached in a circular area (3 μm diam; white circles). Cells were imaged before each new bleach pulse, and fluorescence intensities of neighboring nucleoli and nucleoplasmic areas (black and white circles) were determined. Almost all fluorescence was lost from both compartments after 50 bleach cycles, indicating a high exchange rate between nucleolar and nucleoplasmic topo II.

In summary, these data support the conclusion of a rapid and unrestricted exchange of fluorescent topo II molecules between individual nucleoli, and between the nucleoplasm and nucleoli. This interpretation is more in agreement with a recent concept proposing rapid and continuous diffusional movement of proteins between nucleoplasm and nuclear compartments (Misteli, 2001) than with the older idea of distinct subpopulations of topo II existing in separate cellular pools (Swedlow et al., 1993).

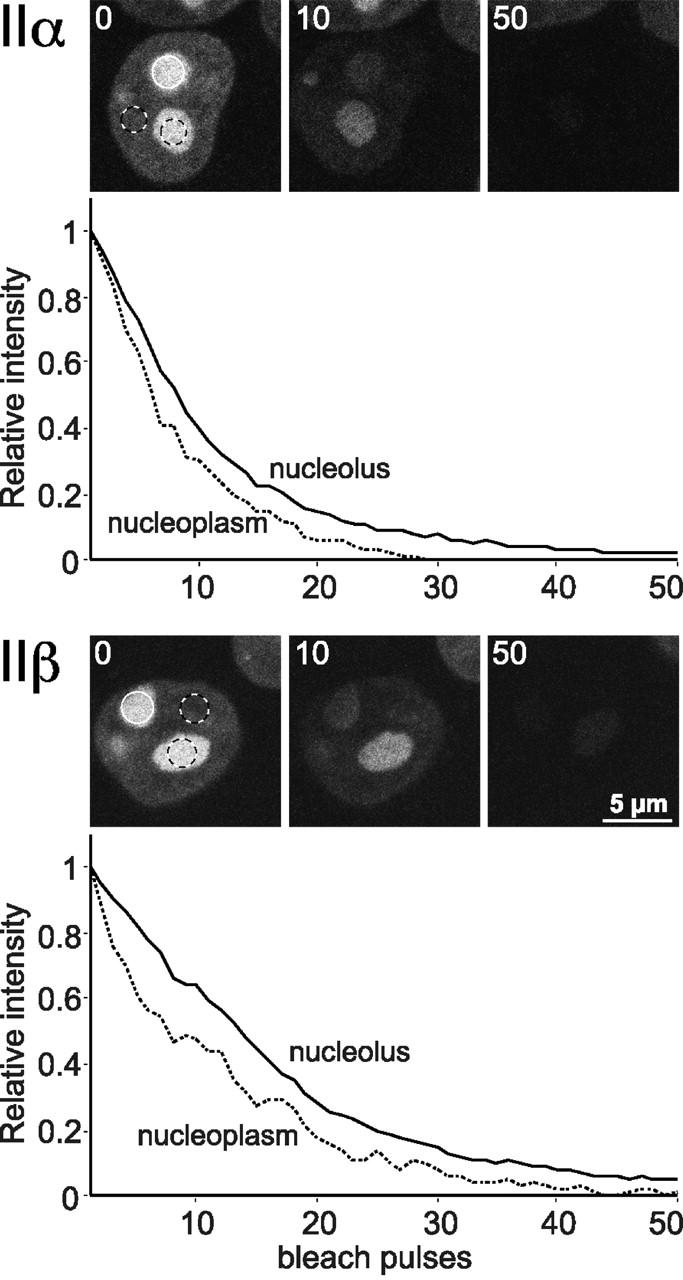

Mobility of mitotic topo IIα

The high degree of mobility of topo IIα and IIβ in interphase nuclei makes it unlikely that the enzymes play a structural role in building a karyoskeleton. However, it is still possible that they participate in building the mitotic chromosome scaffold which is the major structural role proposed for these enzymes (Adachi et al., 1991). To address this issue, we determined the mobility of topo IIα in chromosomes (Fig. 8). These experiments were restricted to the α-isozyme, because chromosomal and cytosolic locations of topo IIβ–GFP could not be reliably discriminated (compare Figs. 8 and 4 B). Unexpectedly, fluorescence recovery of topo IIα–GFP (Fig. 8 A, upper panel) after photobleaching of a chromosomal area in a metaphase plate, was fast (t1/2 = 3.5 s) and complete. We obtained similar recovery kinetics with chromosomes of cells in pro-, ana- or telophase (unpublished data). Moreover, the FLIP experiment shown in Fig. 8 B demonstrates that all topo IIα–GFP fluorescence was lost from chromosomes and the cytoplasm of a given cell when repeated bleach pulses were applied to a distinct chromosomal area. Comparable results were obtained when the cytosol was repeatedly bleached (unpublished data). In summary, these data indicate that topo IIα is mobile within the chromosome. An immobile fraction is virtually absent. The FLIP experiment also demonstrates unrestricted movements of the enzyme between chromosomes and the cytoplasm. To corroborate these controversial findings, we needed to prove that we would have detected an immobile fraction, if present. This was achieved in two ways. First, we demonstrated immobility of GFP-histone H3 in mitotic chromosomes (Fig. 8 A, bottom). Second, we demonstrated immobility of topo IIα–GFP and topo IIβ–GFP trapped on chromosomal DNA by VM 26 (Fig. 8 A, middle panels). Both control experiments attest to the validity of our data regarding the unexpected degree of mobility of chromosomal topo IIα in the absence of VM 26.

Figure 8.

Photobleaching experiments on mitotic chromosomes. (A) FRAP (as described in Fig. 5) of metaphase chromosomes in cells expressing GFP chimera of topo IIα (with and without 100 μM VM 26), topo IIβ (VM 26-treated) or histone H3 after bleaching a circular area of 3 μm diam. Bleaching of topo IIβ–GFP-labeled chromosomes not treated with VM 26 was not possible, as they were obscured by large amounts of cytosolic topo IIβ–GFP (Figs. 3 and 4 B). (B) FLIP (as described in Fig. 7) of a chromosomal and a cytoplasmic region (black and white circles) after bleaching of another chromosomal area (white circle) in a metaphase cell expressing topo IIα–GFP.

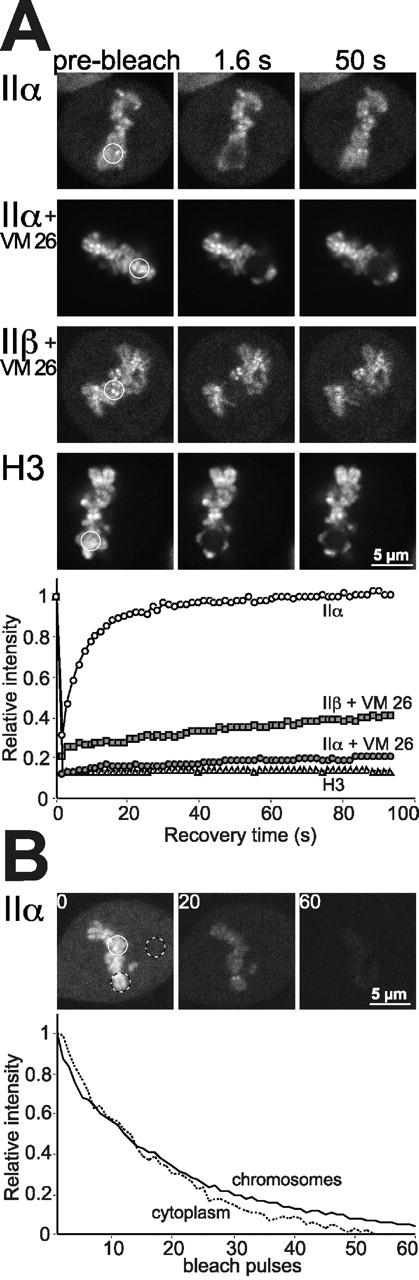

Is topo II axially located in chromosomes?

Our data obviously conflict with the established view that topo IIα plays a structural role in building a static chromosome scaffold. This view stems in part from observations made by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, demonstrating topo II along the longitudinal axes of chromosome arms (Earnshaw and Heck, 1985; Gasser et al., 1986; Taagepera et al., 1993; Sumner, 1996; Meyer et al., 1997). However, such axial patterns were not seen when rhodamine-labeled topo II was injected into living insect cells (Swedlow et al., 1993), and were not consistently seen with immunofluorescence (Warburton and Earnshaw, 1997). Here, we determined the distribution of GFP-tagged topo IIα in chromosomes of living cells and in native chromosome spreads prepared thereof.

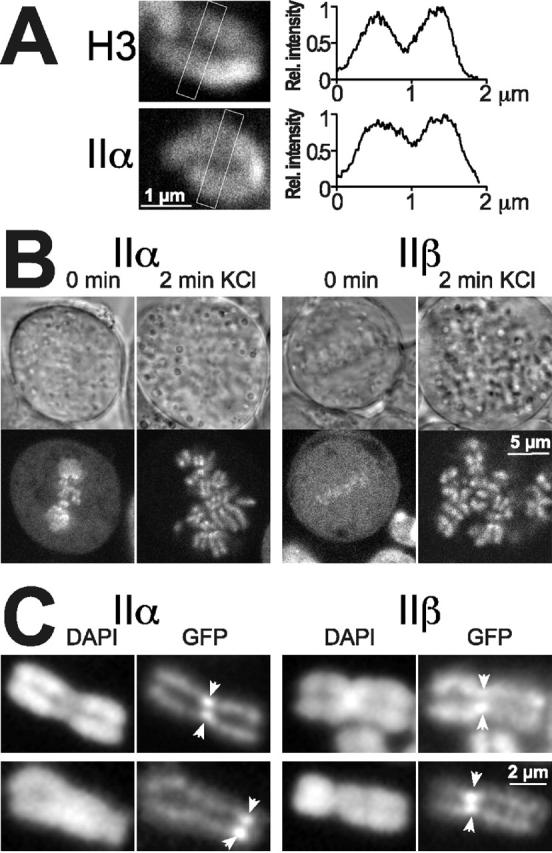

Fig. 9 A shows high-resolution confocal microscopy images of topo IIα–GFP and GFP-histone H3 in single chromosomes of living cells. The quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity distribution in representative cross sections of the chromosomes (boxes) shows that both proteins covered a similar chromosome diameter of 0.8–1 μm, and had a similar distribution. Because histone H3 is an integral part of the chromatin and hence can be assumed to cover the entire chromosome, these data suggest that, in living cells, topo IIα is not confined to chromosome axes.

Figure 9.

Chromosomal distribution of topo II. (A) Single chromosomes in living metaphase cells expressing topo IIα–GFP or GFP-histone H3 were imaged by high resolution confocal microscopy. Distribution of fluorescence intensity was quantified in the boxed cross sections of the chromosomes. Mean fluorescence intensity of pixel columns across the short diameter of the boxes was normalized to maximal values, and plotted against corresponding distances measured across the long diameter of the boxes (right). (B) Effect of hypotonic treatment on topo II distribution in metaphase. Two cells expressing topo IIα–GFP or topo IIβ–GFP were imaged by confocal microscopy before (0 min) and 2 min after exchanging the medium for KCl solution (75 mM). Images of transmitted light are shown above a corresponding confocal section showing green fluorescence of the same cell. Note the substantial increase in size of KCl-treated cells. (C) Subchromosomal distribution and stability of topo II isoforms in unfixed, spread chromosomes. Cells expressing topo IIα–GFP or topo IIβ–GFP were harvested, collected by centrifugation, swollen in hypotonic solution, and spotted on glass slides without fixation. Spread chromosomes were mounted in DAPI-containing CSK buffer and imaged either immediately (top) or 2 h later (bottom) using filter sets for the specific detection of the DNA stain (DAPI) and the green fluorescence (GFP), respectively. Arrowheads mark the position of centromere pairs.

Next, we exposed cells at metaphase expressing topo IIα–GFP (Fig. 9 B, left) or topo IIβ–GFP (Fig. 9 B, right) to 75 mM KCl for 2 min which is a standard procedure for preparing chromosome spreads. As expected, the cells increased in volume (Fig. 9 B, top). Unexpectedly, the metaphase plate was completely disrupted by the treatment and, most notably, the entire cellular complement of topo IIα and IIβ became associated with the chromosomes (Fig. 9 B, bottom). This redistribution closely resembles the effect of VM 26 (compare Figs. 9 B and 4 C), suggesting that hypotonic treatment disrupts the catalytic cycle of topo II in such a way that all enzyme molecules are rapidly (within 2 min) trapped in the DNA-bound state. Fig. 9 C shows chromosome spreads subsequently prepared from swollen cells spotted on microscope glass slides and mounted without further fixation. When such native chromosomes were inspected immediately after spreading (Fig. 9 C, top), both GFP-tagged topo II isoforms (GFP) appeared to be more or less evenly distributed over the whole length and width of the chromosome arms, as defined by the DNA stain (DAPI). Topo IIα–GFP was enhanced at the centromeres (arrows), whereas this was less evident for topo IIβ–GFP. When the same specimen were inspected after incubation at ambient temperature for 2 h (Fig. 9 C, bottom), the overall intensity of topo II–GFP-specific signals decreased and the pattern changed. Both isoforms were now clearly confined to the central axis of chromosome arms, delineating a structured pattern that closely resembled numerous published immunohistochemical images. In addition, centromeric accumulation became more pronounced and evident with topo IIβ–GFP, too.

In summary, these observations demonstrate that the localization of topo II in chromosome spreads differs notably from the situation in living cells. Apparently, hypotonic treatment of cells triggers a series of events eventually generating an axial pattern of topo II. First, the whole complement of the enzymes relocates rapidly from the cytosol to the chromosomes. Then, a loosely bound fraction of topo II is gradually lost over time from the outer region of the chromosome arms. This unveils another fraction bound to the centromere and the chromosomal core in a more stable manner. We envisage that during immunohistochemical staining procedures topo II can easily be lost from the chromosomal periphery, thus leading to the impression that topo II is confined to the chromosome axis. This would also explain why in some cases both patterns—axial and even distribution over chromosome arms—have been detected within the same sample (Sumner, 1996).

Discussion

Our findings about the dynamic distribution and mobility of topo II isoforms in living cells have implications for their involvement in nuclear architecture. Recent studies using photobleaching techniques have shown that only a few components of the nucleus are immobile, i.e. the chromatin itself, chromatin-bound core histones (Phair and Misteli, 2000), and structural components building the nuclear lamina (Moir et al., 2000), whereas most other nuclear proteins move rapidly throughout the nucleus. Moreover, the components of nuclear compartments, e.g. nucleoli, seem to be in continuous flux between the compartment and the nucleoplasm (Misteli, 2001). Here, we find that both human topo II isoforms belong to the class of mobile proteins. Their entire pools are mobile and exchange rapidly between nuclear compartments in interphase and between chromosomes and the cytoplasm in mitosis. This came as a surprise, considering the general opinion on the dual role of topo II as an enzyme and a structural protein forming a mitotic scaffold or interphase nuclear matrix (Berrios et al., 1985; Earnshaw and Heck, 1985; Gasser et al., 1986; Adachi et al., 1991). Our observation that at each stage of the cell cycle bleached areas were rapidly and completely replenished with fluorescent topo II molecules, makes it unlikely that even a subpopulation of topo II could be an integral component of immobile structures such as a putative karyoskeleton or chromosome scaffold. However, we cannot rule out that topo II transiently associates with such structures. In fact, the often reported colocalization of topo II with the chromosomal core together with our own observations on the distribution of topo II–GFP in native chromosome spreads (Fig. 9 C) even suggests a tight (but dynamic) interaction of topo II with the chromosomal scaffold.

On the other hand, topo II is obviously restricted in its mobility, because it moves slower than GFP which is believed to be freely diffusible. It has been proposed that such an attenuation in mobility is caused by interactions with less mobile nuclear components (Misteli, 2001). However, the nature of such components—the chromatin, a putative karyoskeleton, or both—is an unsolved issue (Shopland and Lawrence, 2000; Misteli, 2001). In this respect, our observation that VM 26 treatment depletes topo II from nucleoli is of interest, because it suggests that it is not the direct interaction with chromatin that slows down topo II and causes its accumulation in this compartment. Moreover, nucleoli recruit most of the topo II complement of the nucleus and it is not likely that such a large fraction is required for the topological organization of the nucleolar chromatin which is small in comparison to the entire genome. Thus, the decreased mobility of topo IIα and IIβ in nucleoli is likely due to interactions with other proteins and not with DNA. On the other hand, considering the dense packing of topo IIα and IIβ in the nucleoli of living cells (Fig. 2), and considering that among numerous topo II–interacting proteins described in the literature, none is a nucleolar protein, it could also be imagined that polymerization of topo II (Vassetzky et al., 1994) might create a transient, less mobile structure thus contributing to accumulation of the enzymes in nucleoli.

Our observations also shed some light on ongoing discussions about isoform-specific topo II functions in mammalian cells. It is clear that topo II function in general is required for maintenance of the nucleolar structure and the folding of rDNA into functionally organized nucleolar genes in yeast and mammals (Christman et al., 1988; Hirano et al., 1989; Iarovaia et al., 1995). We find that both isoforms accumulate in nucleoli and exhibit the same subnucleolar distribution, indicating that they are both engaged in these functions. Thus, topo IIα and IIβ have probably many similar functions in the interphase nucleus. However, our data clearly indicate that topo IIβ differs significantly from topo IIα in its contribution to the mitotic cycle. We find that in metaphase topo IIβ is scarcely chromosome-associated. This fits with the recent observation that disruption of the TOP2β gene has little effect on early embryonal development in mouse (Yang et al., 2000), and with our previous finding that in a mammalian cell, topo IIβ cannot substitute topo IIα during mitosis (Grue et al., 1998). It now seems quite clear that topo IIβ is not required for mitotic cell division; however, in a living cell, topo IIβ is not fully excluded from metaphase chromosomes (Fig. 4 B), and to some extent it retains the ability to engage in catalytic DNA turnover in the chromosome (Fig. 4 C). This might be sufficient to support mitotic topo II functions in yeast (Jensen et al., 1996a; Fig. 1 C), but not in mammals (Grue et al., 1998).

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

Bicistronic expression vectors for mammalian cells were constructed from the plasmid pMC-2P (Mielke et al., 2000), in which the translational initiation of the selection marker in the second cistron is mediated by an internal ribosome entry site from poliovirus. The coding sequences for GFP and for fusions of human topo II isoforms and GFP were inserted in front of the internal ribosome entry site by linker PCR. For the yeast complementation assay plasmids pHT300 and pHT400 (Jensen et al., 1996a), carrying cDNAs of human topo IIα and IIβ under the control of the yeast triose phosphate isomerase (TPI) gene promoter, were modified to express human topo II–GFP fusion proteins by replacing 3′-terminal restriction fragments of topo II reading frames by PCR-generated fragments containing the respective GFP chimera from the mammalian expression vectors.

Cell culture and transfection

The human embryonal kidney cell line 293 (DSMZ) was grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in DME with Glutamax-I (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U penicillin/ml, and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (GIBCO BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 2 d, stable cell lines were selected and maintained thereafter in medium containing 0.35 μg ml−1 puromycin.

Complementation assay

Yeast complementation was carried out as described by Jensen and colleagues (1996a). Briefly, LEU2 expression plasmids for human topo II isoforms and the respective GFP chimera were transformed into the haploid Δtop2 strain BJ201 (pHT173 [S.pombe TOP2/URA-ARS/CEN] MATα ura3 trp1 leu2 his3 pep4::HIS3 prb1Dcan1 top2::TRP1 GAL) which contains a URA3 plasmid carrying the S. pombe TOP2 gene to substitute for the essential topo II activity. Colonies from selection plates (without Leu) were then streaked onto media containing 1 mg ml–1 5-FOA to counterselect against the plasmid carrying the S. pombe TOP2 gene.

Immunoblotting and band depletion assay

5 × 105 cells were harvested, resuspended in PBS, and lysed by addition of an equal volume of twofold lysis buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 8 M urea, 20% glycerol, 0.04% bromophenol blue, 10 mM 4-[2-Aminoethyl]-benzenesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM PMSF, 20 μg ml−1 Aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 Pepstatin A). Whole cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, and blotted onto PVDF membranes (Immobilon P; Millipore). Blots were blocked in 2% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20 in CMF-PBS (167 mM NaCl, 25.5 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.5) and then incubated for 1 h in the same buffer with diluted primary antibodies (mouse monoclonal topo IIα antibody KiS1 [Boege et al., 1995]; mouse monoclonal peptide topo IIβ antibody 3H10 [Kimura et al., 1996]; mouse monoclonal GFP-antibody [CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.]; and mouse monoclonal α-tubulin antibody [Sigma-Aldrich]). After washing, the filters were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti–rabbit or goat anti–mouse antibodies in 2% BSA, 0.1% Tween 20 in CMF-PBS for 1 h. After extensive washing with the same buffer, specific protein bands were detected with the ECL Plus system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). For immunoband depletion, cells were incubated with 200 μM VM 26 for 1 h prior to harvesting.

Immunoprecipitation and kDNA decatenation

Magnetic particles (Dynabeads M 500; Dynal) were covalently coated (according to the producers manual) with rabbit antibodies against topoisomerase IIα (Genosys) and mouse monoclonal antibodies against topo IIβ (Meyer et al., 1997) or GFP (Roche). 2 × 107 coated beads were saturated for 2 h at 4°C with nuclear extracts obtained from 109 cells (Meyer et al., 1997). Subsequently, the beads were collected with a magnet, washed with binding buffer (175 mM NaCl, 6 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 14% glycerol, 0.2 mM DTT, 0.5 mM 4-[2-Aminoethyl]-benzenesulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 5% FBS), and then with assay buffer (120 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.9, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA, 30 μg ml−1 BSA). Finally, the beads were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with 1 μg crithidia fasciculata kinetoplast DNA (kDNA; TopoGen, Inc.) in a final volume of 40 μl assay buffer. Negative controls included addition of 300 μM Na3VO4 and beads not incubated with nuclear extracts. Alternatively, the beads were eluted with 100 mM Na3PO4, 100 mM NaCitrate, pH 3 and 3 M urea. Eluates were subjected to SDS-PAGE (6% gels) and visualized by silver staining.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were grown on microscopic coverslips, washed in PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min on ice, and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in the presence of 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min on ice. All subsequent steps were carried out at ambient temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were blocked for 1 h in PBS, 2% BSA, 5% goat serum and then incubated for 1 h with topo IIα antibody KiS1 or topo IIβ antibody 3H10 diluted 1:500 in blocking solution. After washing, bound antibodies were visualized by incubation for 1 h with Cy3™-conjugated goat anti–rabbit or anti–mouse F(ab′)2 fragments (Dianova) diluted 1:1,000. Coverslips were then washed three times for 5 min in PBS. The first wash contained 80 ng ml−1 DAPI to stain genomic DNA.

Microscopy

Epifluorescent images were acquired with appropriate filter sets (AHF Analysentechnik) at 630× magnification using an inverted microscope (Axiovert 100; Carl Zeiss) equipped with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (Sensys; Photometrics Ltd.) and an additional 4× magnification lens. Living cells were grown and inspected in CO2-independent medium (GIBCO BRL) in poly-l-lysine–coated live-cell chambers (Bioptechs, Inc.) at 37°C.

Confocal imaging, FRAP and FLIP analyses of living cells were performed at 37°C with a Zeiss LSM 510 inverted confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a CO2-controlled on-stage heating chamber using a heated 63×/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective and the FITC filter setting (488 nm/ 515 nm). It should be emphasized that strict temperature control was crucial for topo II localization and mobility. For FRAP experiments, a single optical section was acquired with 5.6× zoom. Images were taken before and at 1.577 s time intervals after bleaching of a circular area at 20 mW nominal laser power with three iterations. The imaging scans were aquired with a laser power attenuated to 0.1–1% of the bleach intensity. The same settings were used for FLIP experiments where cells were repeatedly bleached and imaged at intervals of 15 s. For quantitative FRAP analysis, fluorescence intensities of the bleached region and the entire cell nucleus were measured at each time point. Data were corrected for extracellular background intensity and for the overall loss in total intensity as a result of the bleach pulse itself and the imaging scans. Unless stated otherwise, FRAP recovery curves were generated by calculating the relative intensity of the bleached area I rel as described (Phair and Misteli, 2000). FLIP depletion curves of selected areas outside the bleach spot were just corrected for the loss of fluorescence intensity caused by the imaging scans by comparison with the fluorescence intensity of a neighboring cell nucleus. Bleaching of mitotic cells (Fig. 8) was performed in the presence of 0.1 μM paclitaxel to reduce movements of the chromosomes.

Spreading of native chromosomes

107 exponentially growing cells were harvested, collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 160 g, and carefully resuspended in 6 ml hypotonic solution (0.075 M KCl). Cells were pelleted as above, resuspended in 400 μl hypotonic solution and drops of about 50 μl were then spotted on a slightly tilted glass slide. Prior to this, slides were carefully cleaned in methanol and then soaked in double distilled water. After spreading, unattached cells were removed by letting 200 μl isotonic cytoskeleton CSK buffer (100 mM KCl, 300 mM sucrose, 10 mM Pipes, pH 6.8, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM 4-[2-Aminoethyl]-benzenesulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM PMSF, 20 μg/ml Aprotinin, 10 μg/ml Pepstatin A) containing 80 ng/ml DAPI run down the slightly tilted slide. Spread chromosomes were then carefully mounted in the same buffer.

Online supplemental material

Video 1 (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200112023/DC1)(10 images per second) shows topo IIα–GFP- and topo IIβ–GFP-expressing cells proceeding through a mitotic cycle from prophase to early G1 phase. Time-lapsed images (one image every 30 s) were acquired by confocal microscopy, and corresponding images of transmitted light (left) and green fluorescence (right) are mounted side by side.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ullrich Scheer, Jörg Hacker, Hilde Merkert, and Jørn Koch for providing help with and access to high quality microscopy devices.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bo 910/3-1, Bo 910/4-1, GRK 639, HA 1434/13-1), the Danish Cancer Society (97-100-32, 97-143-09-9132, 97-143-10-9132), the Danish Research Council, the Danish Center for Molecular Gerontology, and the Thaysen Foundation.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: FLIP, fluorescence loss in photobleaching; FOA, fluoroorotic acid; GFP, green fluorescent protein; topo, DNA topoisomerase; TPI, triose phosphate isomerase.

References

- Adachi, Y., E. Kas, and U.K. Laemmli. 1989. Preferential, cooperative binding of DNA topoisomerase II to scaffold-associated regions. EMBO J. 8:3997–4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi, Y., M. Luke, and U.K. Laemmli. 1991. Chromosome assembly in vitro: topoisomerase II is required for condensation. Cell. 64:137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin, C.A., and K.L. Marsh. 1998. Eukaryotic DNA topoisomerase IIβ. Bioessays. 20:215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrios, M., N. Osheroff, and P.A. Fisher. 1985. In situ localization of DNA topoisomerase II, a major polypeptide component of the Drosophila nuclear matrix fraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 82:4142–4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boege, F., A. Andersen, S. Jensen, R. Zeidler, and H. Kreipe. 1995. Proliferation-associated nuclear antigen Ki-S1 is identical with topoisomerase IIα. Delineation of a carboxy-terminal epitope with peptide antibodies. Am. J. Pathol. 146:1302–1308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boy de la Tour, E., and U.K. Laemmli. 1988. The metaphase scaffold is helically folded: sister chromatids have predominantly opposite helical handedness. Cell. 55:937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaly, N., and D.L. Brown. 1996. Is DNA topoisomerase IIβ a nucleolar protein? J. Cell. Biochem. 63:162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaly, N., X. Chen, J. Dentry, and D.L. Brown. 1996. Organization of DNA topoisomerase II isotypes during the cell cycle of human lymphocytes and HeLa cells. Chromosome Res. 4:457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman, M.F., F.S. Dietrich, and G.R. Fink. 1988. Mitotic recombination in the rDNA of S. cerevisiae is suppressed by the combined action of DNA topoisomerases I and II. Cell. 55:413–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, F.H., G.A. Hofmann, H.F. Bartus, M.R. Mattern, S.T. Crooke, and C.K. Mirabelli. 1989. Biochemical and pharmacological properties of p170 and p180 forms of topoisomerase II. Biochemistry. 28:8154–8160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw, W.C., B. Halligan, C.A. Cooke, M.M. Heck, and L.F. Liu. 1985. Topoisomerase II is a structural component of mitotic chromosome scaffolds. J. Cell Biol. 100:1706–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw, W.C., and M.M. Heck. 1985. Localization of topoisomerase II in mitotic chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 100:1716–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser, S.M., T. Laroche, J. Falquet, E. Boy de la Tour, and U.K. Laemmli. 1986. Metaphase chromosome structure. Involvement of topoisomerase II. J. Mol. Biol. 188:613–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grue, P., A. Grasser, M. Sehested, P.B. Jensen, A. Uhse, T. Straub, W. Ness, and F. Boege. 1998. Essential mitotic functions of DNA topoisomerase IIα are not adopted by topoisomerase IIβ in human H69 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:33660–33666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T., G. Konoha, T. Toda, and M. Yanagida. 1989. Essential roles of the RNA polymerase I largest subunit and DNA topoisomerases in the formation of fission yeast nucleolus. J. Cell Biol. 108:243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T., and T.J. Mitchison. 1993. Topoisomerase II does not play a scaffolding role in the organization of mitotic chromosomes assembled in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Biol. 120:601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iarovaia, O.V., M.A. Lagarkova, and S.V. Razin. 1995. The specificity of human lymphocyte nucleolar DNA long-range fragmentation by endogenous topoisomerase II and exogenous Bal 31 nuclease depends on cell proliferation status. Biochemistry. 34:4133–4138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, S., C.S. Redwood, J.R. Jenkins, A.H. Andersen, and I.D. Hickson. 1996. a. Human DNA topoisomerases IIα and IIβ can functionally substitute for yeast TOP2 in chromosome segregation and recombination. Mol. Gen. Genet. 252:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, S., A.H. Andersen, E. Kjeldsen, H. Biersack, E.H. Olsen, T.B. Andersen, O. Westergaard, and B.K. Jakobsen. 1996. b. Analysis of functional domain organization in DNA topoisomerase II from humans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:3866–3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, K., N. Nozaki, T. Enomoto, M. Tanaka, and A. Kikuchi. 1996. Analysis of M phase-specific phosphorylation of DNA topoisomerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21439–21445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.F. 1989. DNA topoisomerase poisons as antitumor drugs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58:351–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, J.P., and G.J. Goldenberg. 1998. Induction of apoptosis by deregulated expression of DNA topoisomerase IIα. Cancer Res. 58:4519–4524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, K.N., E. Kjeldsen, T. Straub, B.R. Knudsen, I.D. Hickson, A. Kikuchi, H. Kreipe, and F. Boege. 1997. Cell cycle–coupled relocation of types I and II topoisomerases and modulation of catalytic enzyme activities. J. Cell Biol. 136:775–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke, C., M. Tummler, D. Schubeler, I. von Hoegen, and H. Hauser. 2000. Stabilized, long-term expression of heterodimeric proteins from tricistronic mRNA. Gene. 254:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli, T. 2001. Protein dynamics: implications for nuclear architecture and gene expression. Science. 291:843–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y.Y., and W.T. Beck. 1999. Association of human DNA topoisomerase IIα with mitotic chromosomes in mammalian cells is independent of its catalytic activity. Exp. Cell Res. 252:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moir, R.D., M. Yoon, S. Khuon, and R.D. Goldman. 2000. Nuclear lamins A and B1. Different pathways of assembly during nuclear envelope formation in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 151:1155–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson, M.O., M. Dundr, and A. Szebeni. 2000. The nucleolus: an old factory with unexpected capabilities. Trends Cell Biol. 10:189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson, T. 2000. Half a century of “the nuclear matrix.” Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phair, R.D., and T. Misteli. 2000. High mobility of proteins in the mammalian cell nucleus. Nature. 404:604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, P., F.H. Drake, A. Loranger, W. Huang, and R. Hancock. 1993. Localization of DNA topoisomerase II in Chinese hamster fibroblasts by confocal and electron microscopy. Exp. Cell Res. 204:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattner, J.B., M.J. Hendzel, C.S. Furbee, M.T. Muller, and D.P. Bazett-Jones. 1996. Topoisomerase IIα is associated with the mammalian centromere in a cell cycle- and species-specific manner and is required for proper centromere/kinetochore structure. J. Cell Biol. 134:1097–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh, Y., and U.K. Laemmli. 1994. Metaphase chromosome structure: bands arise from a differential folding path of the highly AT-rich scaffold. Cell. 76:609–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shopland, L.S., and J.B. Lawrence. 2000. Seeking common ground in nuclear complexity. J. Cell Biol. 150:F1–F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto, K., K. Yamada, M. Egashira, Y. Yazaki, H. Hirai, A. Kikuchi, and K. Oshimi. 1998. Temporal and spatial distribution of DNA topoisomerase II alters during proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in HL-60 cells. Blood. 91:1407–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, A.T. 1996. The distribution of topoisomerase II on mammalian chromosomes. Chromosome Res. 4:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedlow, J.R., J.W. Sedat, and D.A. Agard. 1993. Multiple chromosomal populations of topoisomerase II detected in vivo by time-lapse, three-dimensional wide-field microscopy. Cell. 73:97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taagepera, S., P.N. Rao, F.H. Drake, and G.J. Gorbsky. 1993. DNA topoisomerase IIα is the major chromosome protein recognized by the mitotic phosphoprotein antibody MPM-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:8407–8411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassetzky, Y.S., Q. Dang, P. Benedetti, and S.M. Gasser. 1994. Topoisomerase II forms multimers in vitro: effects of metals, β-glycerophosphate, and phosphorylation of its C-terminal domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:6962–6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.C. 1996. DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:635–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, P.E., and W.C. Earnshaw. 1997. Untangling the role of DNA topoisomerase II in mitotic chromosome structure and function. Bioessays. 19:97–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J., and E. Stelzer. 1999. Photobleaching GFP reveals protein dynamics inside live cells. Trends Cell Biol. 9:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., W. Li, E.D. Prescott, S.J. Burden, and J.C. Wang. 2000. DNA topoisomerase IIβ and neural development. Science. 287:131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.