Abstract

α-Dystrobrevin (DB), a cytoplasmic component of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex, is found throughout the sarcolemma of muscle cells. Mice lacking αDB exhibit muscular dystrophy, defects in maturation of neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) and, as shown here, abnormal myotendinous junctions (MTJs). In normal muscle, alternative splicing produces two main αDB isoforms, αDB1 and αDB2, with common NH2-terminal but distinct COOH-terminal domains. αDB1, whose COOH-terminal extension can be tyrosine phosphorylated, is concentrated at the NMJs and MTJs. αDB2, which is not tyrosine phosphorylated, is the predominant isoform in extrajunctional regions, and is also present at NMJs and MTJs. Transgenic expression of either isoform in αDB−/− mice prevented muscle fiber degeneration; however, only αDB1 completely corrected defects at the NMJs (abnormal acetylcholine receptor patterning, rapid turnover, and low density) and MTJs (shortened junctional folds). Site-directed mutagenesis revealed that the effectiveness of αDB1 in stabilizing the NMJ depends in part on its ability to serve as a tyrosine kinase substrate. Thus, αDB1 phosphorylation may be a key regulatory point for synaptic remodeling. More generally, αDB may play multiple roles in muscle by means of differential distribution of isoforms with distinct signaling or structural properties.

Keywords: dystrobrevin; dystrophin; muscular dystrophy; myotendinous junction; neuromuscular junction

Introduction

The dystrophin–glycoprotein complex (DGC),* which is found throughout the sarcolemma of skeletal muscle cells, forms a multimolecular, transmembrane link between the intracellular cytoskeleton and the extracellular basal lamina (Ervasti and Campbell, 1993). Constituents of the DGC include dystrophin, utrophin, dystroglycans (α and β), sarcoglycans (α, β, δ, γ, and ɛ), syntrophins (α1, β1, and β2), dystrobrevins (DBs; α and β), and sarcospan (Ervasti et al., 1990; Yoshida and Ozawa, 1990; for review see Blake et al., 2002). Interest in the DGC stemmed originally from the finding that mutations in genes encoding numerous DGC components cause muscular dystrophy: loss of dystrophin results in Duchenne muscular dystrophy; deficiencies in four of the sarcoglycans have been linked to limb-girdle muscular dystrophies; and mutations in laminin α 2, the main extracellular ligand for the DGC, lead to congenital muscular dystrophy (Cohn and Campbell, 2000; Blake et al., 2002).

In addition to its role in myofiber integrity, the DGC is also important in formation or maintenance of two specialized domains on the muscle fiber surface: neuromuscular junctions (NMJs), at which motor axons innervate muscle fibers, and myotendinous junctions (MTJs), at which muscle fibers form load-bearing attachments to tendons. The DGC is dispensable for initial steps in postsynaptic differentiation, but contributes importantly to the maturation and stabilization of the postsynaptic membrane. For example, myotubes lacking dystroglycan, utrophin, α1-syntrophin, or αDB have alterations in the density and patterning of acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) embedded within the postsynaptic membrane (Deconinck et al., 1997a; Grady et al., 1997a, 2000; Adams et al., 2000; Jacobson et al., 2001; Akaaboune et al., 2002). Roles of the DGC have been less extensively studied at the MTJ, but several DGC components are concentrated in this region (e.g., dystrophin, utrophin, syntrophin, sarcospan, and nNOS [Chen et al., 1990; Byers et al., 1991; Khurana et al., 1991; Chang et al., 1996; Crosbie et al., 1999]), and MTJs are structurally abnormal in mice lacking dystrophin or both dystrophin and utrophin (Ridge et al., 1994; Deconinck et al., 1997b).

Little is known about how the DGC plays these disparate roles, but one important factor is that its composition varies among cell types (Straub et al., 1999; Loh et al., 2000; Moukhles and Carbonetto, 2001) and, for muscle cells at least, from site to site within a single cell. In muscle fibers, dystrophin is present throughout the sarcolemma, whereas its autosomal homologue, utrophin, is confined to the NMJ and MTJ (Khurana et al., 1991; Ohlendieck et al., 1991). Likewise, each of the three syntrophins has a distinct sarcolemmal distribution (Kramarcy and Sealock, 2000). Here, we focus on another DGC component, αDB, to address the issue of how isoform diversity contributes to functional diversity. αDB is found throughout the sarcolemma in vertebrate skeletal muscle, where it binds dystrophin, utrophin, and syntrophin (Carr et al., 1989; Wagner et al., 1993; Peters et al., 1997b, 1998; Sadoulet-Puccio et al., 1997). A homologue, βDB, has been described but is expressed at low levels if at all in skeletal muscle (Peters et al., 1997a; Blake et al., 1998). Previously, we showed that αDB−/− knockout mice exhibit both muscular defects (muscular dystrophy) and abnormal NMJs (Grady et al., 1999, 2000; Akaaboune et al., 2002). In addition, we show here that αDB−/− mice have malformed MTJs. Thus, αDB influences DGC function at three distinct locations within the muscle cell.

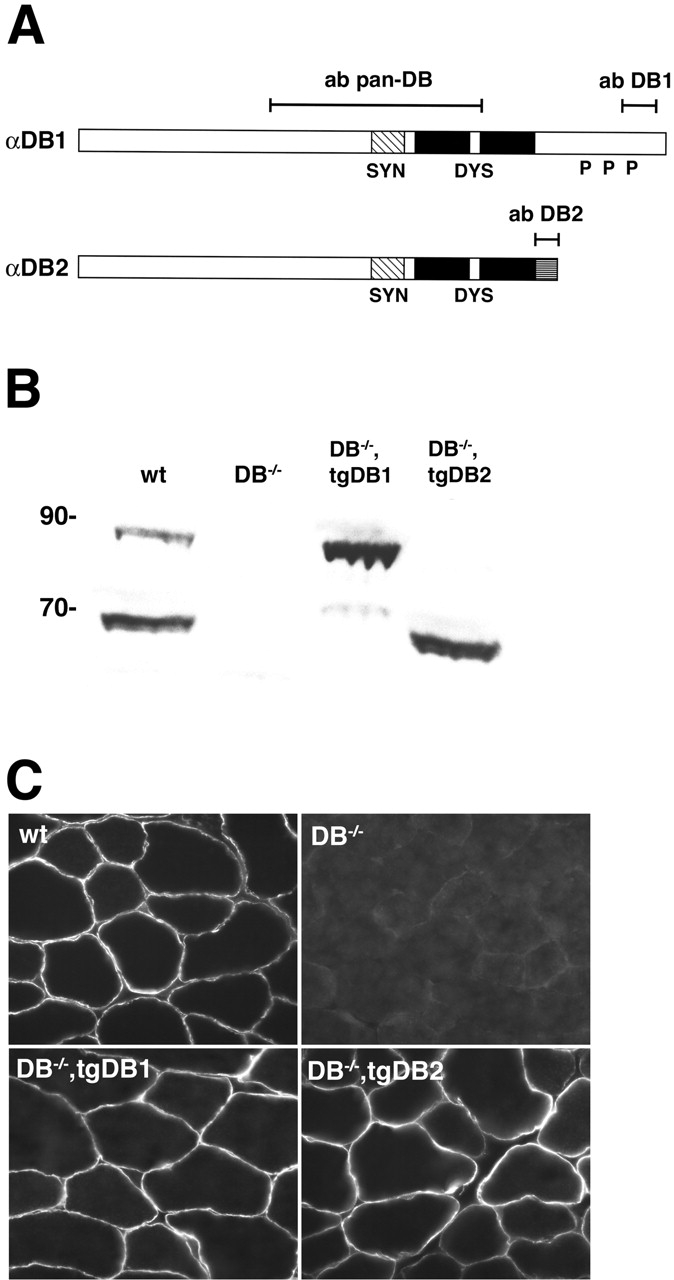

Several isoforms of αDB are generated by alternative splicing, of which three, αDB1–3, have been detected in skeletal muscle (Blake et al., 1996; Sadoulet-Puccio et al., 1996; Enigk and Maimone, 1999; Newey et al., 2001a) They are identical over most of their length (551 aa) but have distinct COOH termini (Fig. 1 A). The 188 aa COOH terminus of αDB1 is a substrate for tyrosine kinases in vivo (Wagner et al., 1993; Balasubramanian et al., 1998), whereas common sequences and the short (16 aa) COOH terminus of αDB2 do not appear to undergo phosphorylation. αDB3 lacks the syntrophin- and dystrophin-binding sites present in the other isoforms and has not been studied in detail. Although both αDB1 and αDB2 are concentrated at the postsynaptic membrane, their detailed localization differs within the junction; furthermore, only αDB2 is present at high levels in extrasynaptic regions (Peters et al., 1998; Newey et al., 2001a). Based on these differences, we hypothesized that αDB1 and αDB2 might have distinct functions. In addition, based on evidence that tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the plasticity of neuron–neuron synapses (Ali and Salter, 2001), we wanted to test the theory that tyrosine phosphorylation of αDB1 affects neuromuscular maturation or structure.

Figure 1.

Generation of transgenic mice. (A) Structure of αDB, showing the two main isoforms expressed in muscle and the regions recognized by anti-αDB antibodies (pan-DB, DB1, and DB2). Also shown are binding regions for syntrophin (SYN; hatched area) and dystrophin (DYS; black area), sequences unique to αDB2 (gray hatched area), and sites in αDB1 that undergo tyrosine phosphorylation in vivo (P). (B) Immunoblot of whole muscle extracts stained with a pan-DB antibody. Equal amounts (50 μg) of protein were loaded for each genotype (wt; wild-type). Molecular weight markers are shown in kD. (C) Immunostaining of skeletal muscle from the four genotypes with a pan-DB antibody. αDB is expressed in >95% of muscle fibers in both transgenic lines.

To directly assess these ideas, we expressed αDB1 or αDB2 in αDB−/− mice and analyzed the ability of each isoform to “rescue” the dystrophic, synaptic, and myotendinous phenotypes. We show that either αDB1 or αDB2 is able to maintain muscle stability but that αDB1 is significantly better than αDB2 in preventing synaptic and myotendinous defects. We also used sited-directed mutagenesis to show that the enhanced efficacy of αDB1 depends in part on its tyrosine phosphorylation.

Results

Generation of transgenic mice

We generated transgenic mice in which regulatory elements from the muscle creatine kinase gene were linked to cDNAs encoding αDB1 or αDB2. Transgenic mice were bred to αDB−/− mice (Grady et al., 1999, 2000). We studied two transgenic lines that expressed αDB1 (12 and 14) and three that expressed αDB2 (11A, 11B, and 28). In the text and figures, the designations tgDB1 and tgDB2 refer to lines 12 and 28, respectively. However, the main results were confirmed with the other lines (see Materials and methods).

Immunoblotting with antibodies that recognize all αDB isoforms showed that levels of transgene expression were similar in the tgDB1 and tgDB2 lines (Fig. 1 B). Levels of recombinant αDB2 in αDB−/−,tgDB2 were similar to levels of endogenous αDB2 in control mice, whereas levels of recombinant αDB1 in αDB−/−,tgDB1 muscle were significantly higher then levels of endogenous αDB1 but similar to levels of total αDB in controls (Fig. 1 B). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that αDB1 and αDB2 were present in >95% of all muscle fibers in αDB−/−,tgDB1 and αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice, respectively (Fig. 1 C). In both lines, the transgene was expressed in all skeletal muscles tested, including tibialis anterior, sternomastoid, and diaphragm, and there were no detectable differences among fibers that correlated with fiber type (unpublished data).

Muscular dystrophy

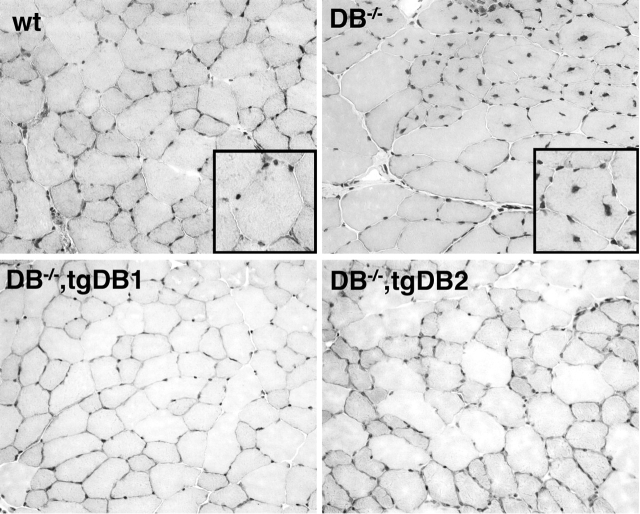

αDB−/− mice exhibit a mild muscular dystrophy characterized by degenerating myofibers, infiltrating monocytes, and centrally nucleated regenerating myotubes (Fig. 2) (Grady et al., 1999). To test whether αDB1 and αDB2 differ in their ability to maintain muscular integrity, we examined the diaphragm, quadriceps, soleus, sternomastoid, and tibialis anterior muscles of αDB−/−,tgDB1 and αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice. The diaphragm provided a particularly stringent test because it is the most severely affected muscle in several models of muscular dystrophy, including αDB−/− mice (Stedman et al., 1991; Grady et al., 1997b, 1999; Duclos et al., 1998). Rescue by both transgenes was dramatic. No degenerating fibers, regenerating (centrally nucleated) fibers, or infiltration by monocytes were detected in any muscles of either αDB−/−,tgDB1 or αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice (Fig. 2 and unpublished data). This was true in mice ranging in age from 1–7 mo, in muscles with predominantly fast (type IIB and II) fibers (tibialis anterior, quadriceps, diaphragm, and sternomastoid), and in muscles with predominantly slow (type I and IIA) fibers (soleus). Thus, either αDB1 or αDB2 alone is capable of maintaining muscle fiber integrity.

Figure 2.

αDB1 and αDB2 both prevent muscle fiber degeneration in αDB −/− mice. Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of skeletal muscle from wild-type, αDB−/−, αDB−/−,tgDB1, and αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice. Regenerated muscle fibers are centrally nucleated, indicating that some of the initial cohort of fibers had degenerated. No histological evidence for muscle fiber degeneration or regeneration was seen in either αDB−/− transgenic line. Insets show high power images.

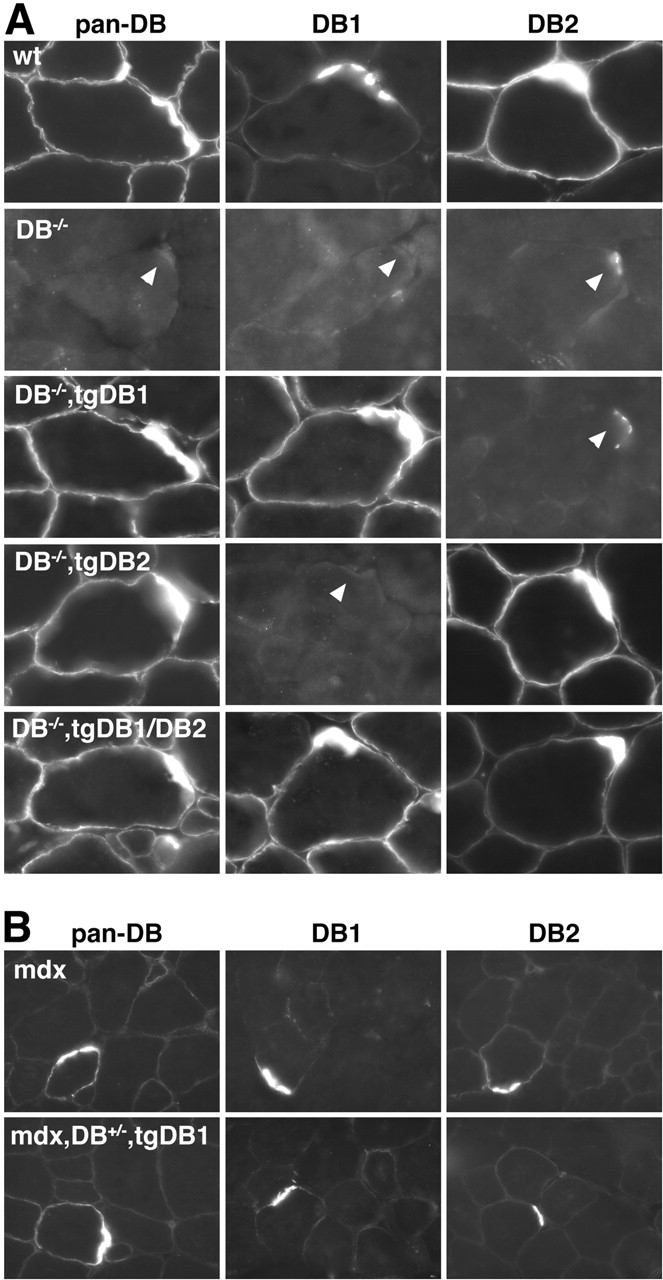

Synaptic localization of αDB isoforms

We immunostained muscles with antibodies specific for αDB1 and αDB2 (Fig. 1 A). Consistent with previous reports, both isoforms are present at higher levels at synaptic sites (marked with rhodamine α-bungarotoxin [rBTX], which binds specifically and quasiirreversibly to AChRs) than in extrasynaptic regions of the sarcolemma (Peters et al., 1998; Grady et al., 2000). Likewise, recombinant αDB1 and αDB2 were concentrated at synaptic sites in αDB−/−,tgDB1 and αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice, respectively (Fig. 3 A). For αDB2, the endogenous and recombinant proteins were distributed similarly. However, whereas endogenous αDB1 was barely detectable extrasynaptically, recombinant αDB1 was abundant extrasynaptically (Fig. 3 A). Thus, selective localization of αDB1 to the NMJ in wild-type muscle cannot be explained solely by its primary sequence.

Figure 3.

Localization of αDB isoforms in αDB −/− and mdx mice expressing αDB1 and/or αDB2. Sections of skeletal muscle stained with antibodies that recognize αDB1, αDB2, or both (pan-DB). Sections were counterstained with rBTX to identify synaptic sites, which are indicated by arrowheads. (A) In wild-type muscle, both αDB1 and 2 are enriched at the synapse, whereas αDB2 is the predominant extrasynaptic isoform. Both isoforms are absent from αDB−/− muscle, although weak synaptic reactivity of unknown molecular identity is seen using the DB2 antibody (Grady et al., 2000). In αDB−/−,tgDB1 and αDB−/−,tgDB2 muscle, transgene-encoded αDB is present throughout the sarcolemma and enriched at synaptic sites. For αDB2, this pattern is similar to that seen in control muscle, but the extrasynaptic abundance of transgenic αDB1 is greater than in controls. In αDB−/− muscle expressing both αDB1 and 2 (DB−/−,tgDB1/DB2), extrasynaptic αDB1 is retained and αDB2 decreases. (B) In mice lacking dystrophin (mdx), sarcolemmal expression of both isoforms is reduced. Likewise, only low levels of extrasynaptic αDB are present in mdx mice expressing recombinant αDB1 (mdx,DB+/−,tgDB1).

The abundance of extrasynaptic αDB1 in αDB−/−,tgDB1 muscle might result from its higher than normal levels (Fig. 1 B). An alternative, however, is that restriction of αDB1 to synaptic sites requires the presence of αDB2. For example, αDB2 might have a higher affinity than αDB1 for extrasynaptic-binding sites and thereby displace αDB1 from such sites. To test this hypothesis, we generated doubly transgenic αDB−/− mice that expressed αDB1 and αDB2 at similar levels. In αDB−/−,tgDB1/DB2 mice, αDB2 was clearly present extrasynaptically, but its presence failed to reduce extrasynaptic levels of αDB1 (Fig. 3 A). Indeed, levels of membrane-associated αDB2 immunoreactivity were decreased when αDB1 was present, suggesting that αDB2 did not bind selectively to extrasynaptic sites.

We also exploited the presence of extrasynaptic αDB1 to test whether αDB1 depends on the DGC for its localization to the sarcolemma. Levels of endogenous αDB, primarily αDB2, are greatly reduced in extrasynaptic regions of dystrophin-deficient (mdx) mice (Grady et al., 1997b). However, there is evidence for dystrophin-independent associations of αDB with the sarcolemma (Crawford et al., 2000), and these associations might be sufficient to tether αDB1 to the membrane. We found that levels of extrasynaptic αDB1 remained low in mdx,αDB+/−,tgDB1 mice despite the overexpression of recombinant αDB1 (Fig. 3 B). Consistent with this result, there was no attenuation of dystrophic symptoms in mdx,αDB+/−,tgDB1 compared with mdx,αDB+/− mice (unpublished data). Thus unique sequences in αDB1 neither mediate a DGC-independent association with the membrane nor attenuate dystrophy in the absence of dystrophin.

AChR distribution and density

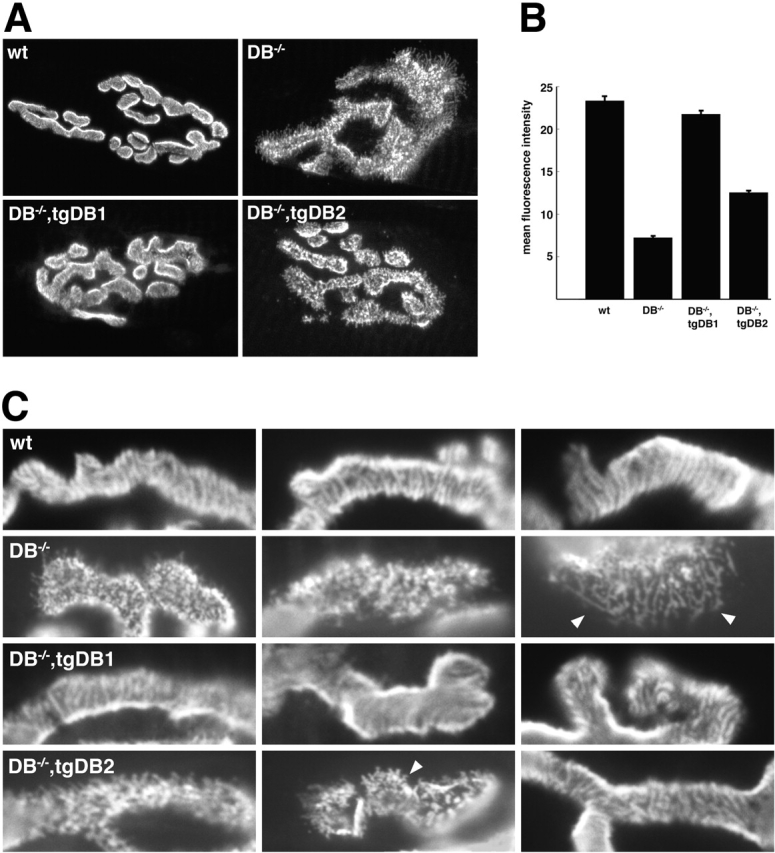

Normal adult mouse NMJs are pretzel shaped with an AChR-rich postsynaptic membrane underlying each branch of the nerve terminal. αDB deficiency does not greatly affect the overall topology of the NMJ but does affect the arrangement of its AChRs in three ways (Fig. 4) (Grady et al., 2000; Akaaboune et al., 2002). First, AChRs smoothly outline each branch in controls, whereas branch borders in mutants are fragmented with long finger-like spicules that radiate beyond the terminal's edge. Second, AChRs in control NMJs are enriched along the crests of the junctional folds that invaginate the postsynaptic membrane, leading to a striated appearance within each branch. In αDB−/− synapses, in contrast, the distinction between the crests and folds is blurred (shown ultrastructurally in Grady et al., 2000) with receptors forming small, irregularly spaced aggregates or clumps. Finally, the density of AChRs is reduced by ∼70% at αDB−/− synapses compared with controls.

Figure 4.

αDB1 is better able than αDB2 to restore normal AChR density and distribution to αDB −/− mice. (A) Longitudinal sections of wild-type, αDB−/−, αDB−/−,tgDB1, and αDB−/−,tgDB2 muscle stained with rBTX. In wildtype synapses, AChRs form multiple branches with smooth borders. Within branches, AChRs are evenly distributed or faintly striated. In αDB−/− synapses, AChRs are patchily distributed with fragmented branch borders and radiating spicules. In αDB−/−,tgDB1 synapses, AChR pattern is essentially normal. In the majority of αDB−/−,tgDB2 synapses, AChRs are patchily distributed, but spicules of AChRs at branch borders are shorter than those of mutants. (B) Synaptic density (± SE) of AChRs in each of the four genotypes as assessed by their mean fluorescence intensity after incubation with a saturating dose of rBTX. AChR density in αDB−/− synapses (n = 49) is ∼30% of wild-type (n = 18). At αDB−/−,tgDB1 synapses (n = 49), AChR density recovers to control levels, whereas in αDB−/−,tgDB2 synapses (n = 19) density remains intermediate between wild-type and αDB−/−. (C) High power images of branches from synapses such as those shown in A to highlight differences in AChR patterning. Spicules are indicated by arrowheads.

Expression of αDB1 in mice prevented all three of these defects: AChR distribution and density were indistinguishable from normal at >95% of synaptic sites examined (Fig. 4). Thus, αDB1 alone can support postsynaptic maturation. In contrast, in αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice examined at 4–6 wk of age the postsynaptic membrane remained abnormal at >90% of synaptic sites: AChRs formed small aggregates comparable to those seen at αDB−/− synapses rather than the linear striations characteristic of normal muscle. On the other hand, most αDB−/−,tgDB2 postsynaptic sites were distinguishable from those in mice lacking all αDB, in that spicules radiating from the edge of the AChR-rich region were either absent or short and AChR density was slightly but significantly greater than in mutants (Fig. 4, B and C). Thus, αDB2 supports normal postsynaptic maturation to a lesser degree than αDB1.

The difference between αDB−/−,tgDB1 and αDB−/−, tgDB2 synapses was also evident in 3–6-mo-old animals. However, the percentage of normal-appearing synapses in αDB−/−,tgDB2 increased to ∼50% at 6 mo of age. This age-related increase suggests that the continued presence of even the relatively ineffective αDB2 can eventually normalize the structure of initially abnormal synapses. Moreover, it raises the possibility that differences between αDB1 and αDB2 are quantitative rather than qualitative. In this regard, it is important to note that levels of transgene expression were similar in αDB−/−,tgDB1 and αDB−/−, DB2 mice (Fig. 1 B). Moreover, studies of transfected muscle fibers, described below, provide independent evidence that αDB1-specific sequences play a distinct role.

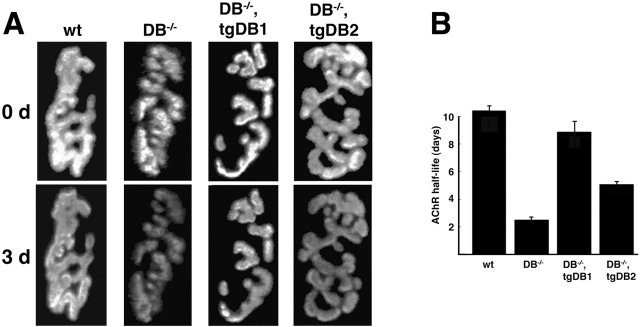

AChR turnover

AChRs migrate and turn over faster at αDB−/− synapses than in controls, supporting the idea that αDB acts in part by tethering AChRs to the postsynaptic cytoskeleton (Akaaboune et al., 2002). Because little is known about the molecular mechanisms that regulate AChR turnover, we quantitated rBTX fluorescence in vivo (see Materials and methods) to ask whether αDB1 and αDB2 had different effects on this process. Adult sternomastoid muscles were labeled with a single nonsaturating dose of rBTX, and individual synapses were imaged. 3 d later, the same synapses were located and imaged again to assess changes in fluorescence intensity. In wild-type mice, ∼20% of the labeled receptors were lost from the cell surface after 3 d. This degree of loss indicates a t1/2 of ∼10.5 d, similar to previous reports (Akaaboune et al., 1999, 2002). In αDB−/− mice, nearly 60% of AChRs were lost over a similar time, indicating a t1/2 of ∼2.5 d (Fig. 5) . AChR stability in αDB−/−,tgDB1 mice did not differ significantly from that of controls (t1/2 = ∼9 d), whereas the t1/2 of AChRs in αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice was intermediate between controls and mutants (t1/2 = ∼5.5 d). Thus, consistent with the results on AChR distribution and density, αDB1 alone can support normal AChR turnover, whereas αDB2 is only partially effective.

Figure 5.

αDB1 is better able than αDB2 to restore normal AChR turnover to αDB −/− mice. Turnover of AChRs as assessed by the change in fluorescence intensity in rBTX-labeled synapses over a 3-d period. (A) Grayscale images used to calculate t1/2. (B) AChRs in wild-type synapses had an average t1/2 of ∼10.5 d (± SE, n = 20), whereas those of αDB−/− synapses (n = 56) were ∼2.5 d. AChR t1/2 in αDB−/−,tgDB1 synapses (n = 45) was similar to that of control mice, whereas t1/2 of αDB−/−,tgDB2 synapses (n = 33) was intermediate between control and αDB−/−.

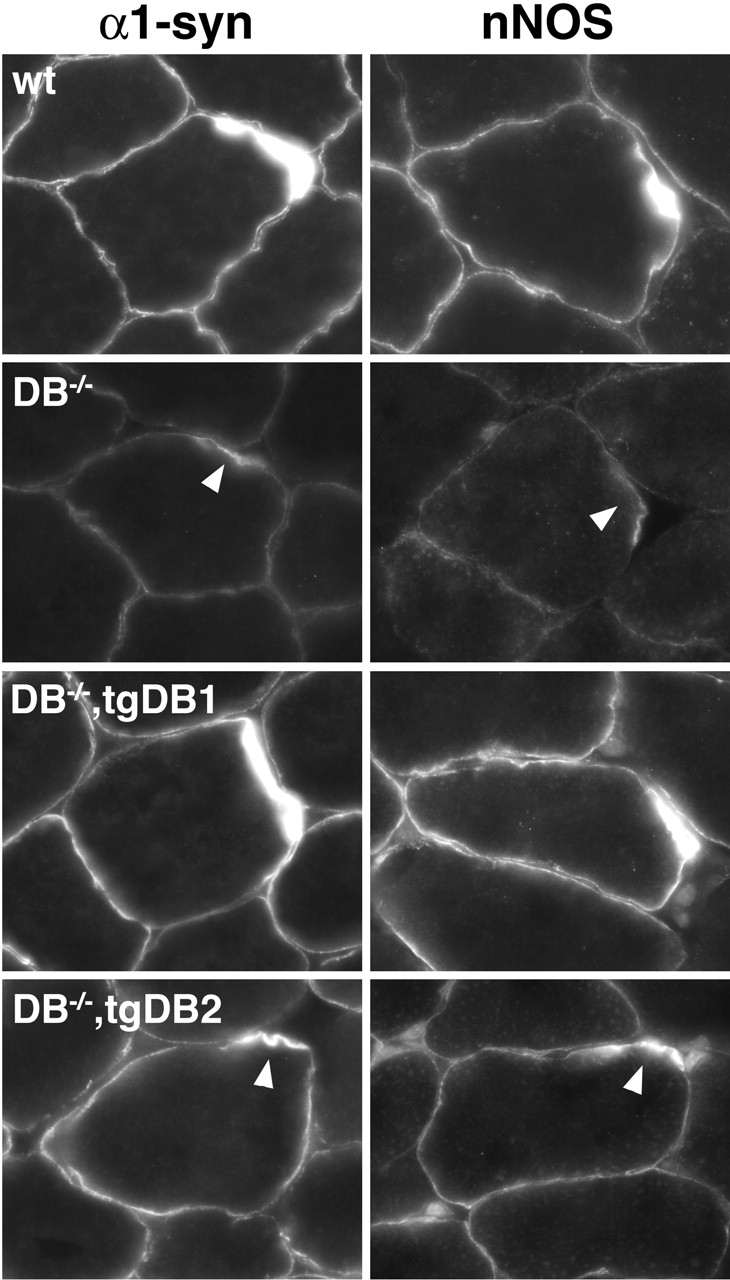

Synaptic localization of α1-syntrophin and nitric oxide synthase

To further investigate mechanisms that might account for the greater ability of αDB1 than αDB2 to support synaptic maturation, we studied the distribution of two proteins whose concentration at synaptic sites requires αDB: α1-syntrophin and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). Levels of both are reduced synaptically and extrasynaptically in αDB−/− mice (Grady et al., 2000). Moreover, α1-syntrophin mutants have synaptic defects similar to those seen in αDB−/− mice (Adams et al., 2000), and studies in vitro have implicated nNOS as a modulator of AChR clustering (Jones and Werle, 2000).

In αDB−/−,tgDB1 muscle, synaptic levels of α1-syntrophin and nNOS were similar to those in controls (Fig. 6) . In contrast, levels of α1-syntrophin and nNOS remained low in many synapses of αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice. Interestingly, when viewed en face, αDB−/−,tgDB2 synapses with the lowest levels of α1-syntrophin also had the most abnormal AChR distribution (unpublished data). Thus, although either αDB isoform can recruit α1-syntrophin and nNOS to the NMJ, the increased efficacy of αDB1 over αDB2 in maintaining synaptic architecture may reflect in part its increased recruiting ability.

Figure 6.

Localization of DGC-associated proteins in αDB mutant and transgenic mice. Sections of skeletal muscle were stained with antibodies to nNOS or α1-syntrophin (α1-syn). In wild-type muscle, nNOS and α1-syntrophin are present throughout the sarcolemma with enrichment at the synaptic sites (arrowheads). In αDB−/− muscle, membrane levels of both proteins were reduced. Expression of αDB1 restored normal levels of both proteins to αDB−/− muscle. In αDB−/−,tgDB2 muscle, levels of nNOS and α1-syntrophin remained lower than normal at many sites.

Role of tyrosine phosphorylation in αDB1 function

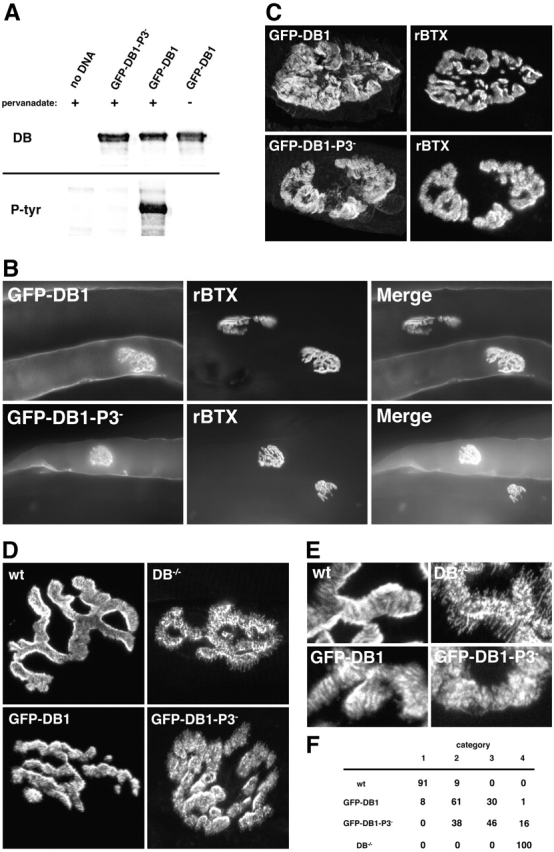

The COOH-terminal domain of αDB1 is tyrosine phosphorylated in vivo (Balasubramanian et al., 1998), raising the possibility that tyrosine phosphorylation is important for its synaptic function. To test this idea, we fused GFP to the NH2 terminus of αDB1 (GFP-DB1) or to a mutant form of αDB1 in which the three major phosphorylated tyrosine residues (aa 698, 706, and 723 [Balasubramanian et al., 1998]) had been changed to phenylalanine by site-directed mutagenesis (GFP-DB1-P3−). Expression of these constructs in heterologous cells showed that only the GFP-DB1 fusion protein underwent tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 7 A). Thus, the addition of GFP to αDB1 did not preclude its phosphorylation, whereas the mutation of its three tyrosine residues did. The two constructs were introduced into tibialis anterior muscles of 2-wk-old αDB−/− mice by electroporation. Muscles were removed 10–14 d later, transfected fibers were identified by GFP fluorescence, and their postsynaptic membranes were analyzed (Fig. 7, B and C).

Figure 7.

Impaired restoration of postsynaptic structure in αDB − / − muscle by αDB1 that lacks tyrosine phosphorylation sites. (A) Immunoblot of HEK293 cells transfected with no DNA, GFP-DB1, or GFP-DB1-P3− expression constructs, lysed, and immunopurified with anti-GFP antibodies. Cells were treated with (+) or without (−) pervanadate before lysis to inhibit tyrosine phosphatases. Protein was identified with either an anti-αDB antibody (DB) or an antiphosphotyrosine antibody (P-tyr). Only GFP-DB1 from pervanadate-treated cells was tyrosine phosphorylated. (B) Fiber bundles from αDB−/− skeletal muscles that had been electroporated in vivo with GFP-DB1 or GFP-DB1-P3− 2 wk earlier. After dissection, muscles were stained with rBTX. Myofibers expressing either fusion protein demonstrate similar fluorescence along the entire sarcolemma with concentrations at synaptic sites. (C) High power images of synapses from transfected muscle fibers showing that both GFP-DB1 and GFP-DB1-P3− are highly concentrated at synaptic sites. (D) Muscle fibers stained with rBTX. Expression of GFP-DB1 in αDB−/− muscle leads to a qualitatively normal AChR pattern with synaptic branches having linear striations and relatively smooth borders. GFP-DB1-P3− has less ability to restore normal AChR distribution in αDB−/− muscle with many synapses having patchy clusters of AChRs and fragmented branch borders. (E) High power images of branches from synapses such as those shown in D to highlight differences in AChR patterning. (F) Comparison of AChR distribution in wild-type fibers (87 synapses), αDB−/− fibers (90 synapses), and in fibers electroporated with GFP-DB1 (118 synapses) or GFP-DB1-P3− (161 synapses). Categories 1 and 4 were synapses typical of wild-type and αDB−/− muscle, respectively; categories 2 and 3 were intermediate. Numbers represent percentages of total synapses examined. Approximately 70% of synapses in fibers expressing GFP-DB1 fell into category 1 or 2 with ≤1% in category 4. In contrast, over 70% of synapses in fibers expressing GFP-DB1-P3− fell into category 3 or 4 with none in category 1.

GFP-DB1 and GFP-DB1-P3− were expressed at equal levels based on fluorescence intensity and were concentrated at synaptic sites to a similar extent (Fig. 7 B), yet they affected AChR distribution in different ways. Expression of GFP-DB1 in αDB−/− myofibers resulted in significant restoration of postsynaptic structure at most synaptic sites, and AChR distribution was qualitatively normal at a subset of NMJs (Fig. 7, D–F). Expression of GFP-DB1-P3− also restored AChR distribution to some extent, but the recovery was significantly less than that seen with GFP-DB1 (p < 0.0001 by Chi-square test), and no synaptic sites appeared normal (Fig. 7, D–F). The variability of “rescue” seen among transfected fibers was greater than that seen in αDB−/− transgenic mice, possibly because GFP interfered with αDB function or because electroporation led to variable protein levels. Nonetheless, these results indicate a role for tyrosine phosphorylation in the function of αDB1.

Interestingly, the qualitative differences between αDB−/− fibers transfected with GFP-DB1 and GFP-DB1-P3− paralleled the differences described above between αDB−/−, tgDB1 and αDB−/−,tgDB2 fibers. Expression of αDB1 either transgenically or by transfection resulted in postsynaptic sites with sharp, spicule-free borders and striated instead of granular interiors. In contrast, although expression of either αDB2 or GFP-DB1-P3− in αDB−/− muscle usually led to restoration of sharp (spicule-poor) borders, interiors remained granular (Fig. 4 B compared with Fig. 7 D). These parallels suggest that the enhanced ability of αDB1 over αDB2 to support synaptic structure depends on its tyrosine phosphorylation.

The MTJ

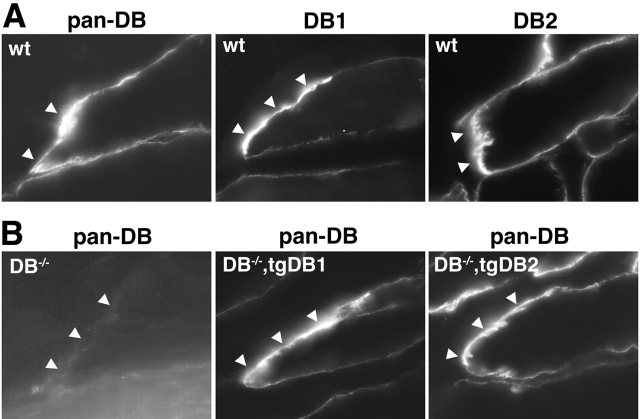

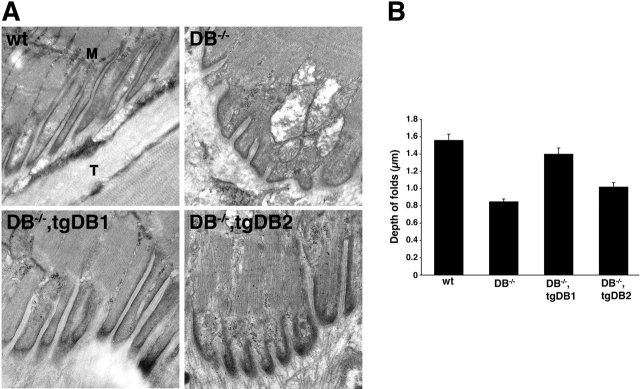

In initial studies, we found that both αDB1 and αDB2 were enriched at the MTJ in wild-type mice (Fig. 8) . We therefore asked whether αDB is required for the integrity of the MTJ. We used EM to address this issue. The muscle membrane at the MTJ is invaginated to form folds that run parallel to the myofiber's long axis (Fig. 9 A). These folds, which are deeper than those of the NMJ, create an interdigitation with the collagen fibrils of the tendon. Folds were also present at mutant MTJs but were significantly shorter than those in controls (Fig. 9, difference between control and αDB−/− p < 0.0001 by ANOVA). Thus, αDB is important for maintaining normal MTJ architecture.

Figure 8.

Localization of αDB isoforms at the MTJ. Sections of skeletal muscle were stained with antibodies to αDB1, αDB2, or both (pan-DB). (A) In wild-type muscle, both αDB1 and 2 were enriched at the MTJ (arrowheads). (B) In αDB−/− muscle, both forms were absent. In both αDB−/−,tgDB1 and DB−/−,tgDB2 muscle, transgene-encoded αDB was restored to the MTJ.

Figure 9.

MTJ structure is abnormal in αDB −/− mice and restored more completely by αDB1 than by αDB2. (A) Electron micrographs of MTJs from wild-type, αDB−/−, αDB−/−,tgDB1, and αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice. Normal MTJs are characterized by multiple folds with long slender projections of muscle (M) interdigitating with the collagen fibrils of the tendon (T). In αDB−/− MTJs, folds are shallower with blunted muscle projections. In αDB−/−,tgDB1 mice, the MTJs appear similar to wild-type, whereas in αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice the MTJs retain many features of αDB−/− MTJs. (B) Measurements of MTJ folds revealed that folds in αDB−/− MTJs (n = 437 folds) are half the size of normal folds (n = 203). Folds in αDB−/−,tgDB1 MTJs (n = 245) were similar to controls, whereas those of αDB−/−,tgDB2 MTJs (n = 230) were intermediate between control and αDB−/−.

Based on these results, we asked whether αDB1 and αDB2 differed in their ability to maintain MTJ structure. In αDB−/−,tgDB1 mice, the depth of the folds was not significantly different from wild-type (Fig. 9 B; p = 0.25), whereas folds in αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice were significantly shorter than those of wild-type or αDB−/−,tgDB1 animals (p < 0.0001). Thus, αDB1 was significantly more effective than αDB2 in maintaining the integrity of both MTJs and NMJs. Because we could not identify transfected fibers in the electron microscope, we were unable to test whether αDB1 phosphorylation plays a role in MTJ maintenance.

Discussion

The DGC plays at least three distinct roles in muscle: maintaining sarcolemmal integrity and stabilizing the structure of both the NMJ and the MTJ. Genetic studies in mice have shown that loss of some DGC components affects one function and not others. For example, absence of dystrophin or of γ-sarcoglycan results in muscular dystrophy with little impact upon the NMJ (Hack et al., 1998; Grady et al., 2000; Akaaboune et al., 2002). Conversely, mice lacking utrophin or α1-syntrophin have abnormal synapses with no detectable dystrophy (Deconinck et al., 1997a; Grady et al., 1997a; Kameya et al., 1999; Adams et al., 2000). In contrast, αDB is critical for all three DGC functions. In this paper, we show that αDB's disparate effects are explained in part through alternative splicing of the αDB transcript and selective localization of the two main muscle isoforms, αDB1 and αDB2.

Muscular dystrophy and αDB

In normal muscle, αDB2 is the predominant extrasynaptic isoform, suggesting that it plays the primary role in helping the DGC maintain muscle viability. Although we found that expression of αDB2 alone in αDB−/− mice prevented muscle fiber degeneration, αDB1 was equally capable. These findings show that the unique COOH terminus of αDB2 is not required for its effect upon the membrane and suggest that shared sequences suffice. Shared domains include sites that mediate binding of αDB to dystrophin and syntrophin. Also included are two EF hand domains and a zinc finger region that can potentially mediate other protein–protein interactions (for review see Enigk and Maimone, 2001). Ligands for these sites are unknown but may include novel αDB-binding proteins identified recently in yeast two-hybrid screens (Benson et al., 2001; Mizuno et al., 2001; Newey et al., 2001b). Thus, it is likely that both αDB1 and 2 can maintain myofiber integrity by attracting similar binding partners to the DGC.

On the other hand, loss of αDB1-specific functions at the MTJ may contribute to muscle pathology. αDB1 is better able than αDB2 to maintain the integrity of the MTJ. The MTJ is the major site of force transmission from muscle fibers to the skeleton, and disruption of this structure may be involved in the pathogenesis of some muscle disorders (Law et al., 1995; Miosge et al., 1999). Previous studies have implicated the DGC in maintenance of the MTJ (Ridge et al., 1994; Deconinck et al., 1997b), and our results suggest that a main role of the DGC at this site may be to recruit αDB1.

Localization of αDB isoforms

In normal muscle, αDB1 is selectively associated with the NMJ and MTJ, but when overexpressed transgenically it was capable of association with extrasynaptic membrane. We therefore wondered what factors account for the normally distinct distributions of the two isoforms. Analysis of mdx mice has shown that the extrasynaptic localization of αDB2 requires an intact DGC, so we considered the possibility that the extrasynaptic localization of αDB2 seen in normal mice results from the preferential binding of αDB2 over that of αDB1 to the DGC. This competition might be accentuated by the higher levels of αDB2 than αDB1 seen in normal muscle (Fig. 1 B). However, analysis of the αDB−/−,tgDB1/DB2 double transgenics, in which αDB1 and αDB2 were expressed at similar levels, showed that αDB1 was not dislodged from its extrasynaptic position by αDB2. Thus the extrasynaptic predominance of αDB2 in normal muscle is not likely to be a result of competition between the isoforms.

Other reasons for the selective distribution of the two isoforms include the possibility that αDB1 might be selectively transcribed from synaptic nuclei, analogous to the synaptic expression of AChR subunits (for review see Sanes and Lichtman, 2001). This is unlikely, however, because both isoforms appear to be transcribed from the same promoter (Newey et al., 2001a). Two remaining potential explanations are as follows: First, there may be posttranscriptional localization of αDB1 mRNA either by synapse-specific stabilization of the mRNA or by synapse-specific transport of the mRNA using targeting information encoded in the 3′ UTR (Newey et al., 2001a). Second, αDB3 might play a role. αDB3 lacks the syntrophin- and dystrophin-binding sites present in αDB1 and 2 (Nawrotzki et al., 1998) but is nonetheless associated with the DGC (Yoshida et al., 2000). Thus, in normal mice αDB3 may confine αDB1 to the NMJ by blocking its access to extrasynaptic-binding sites. This interaction would not occur in αDB−/−,tgDB1 muscle, which lacks αDB1–3.

αDB and the NMJ

αDB is a component of the molecular machinery that stabilizes AChRs within the postsynaptic membrane. In αDB mutants, the mobility of synaptic receptors is increased; as a result, there is enhanced flux from the synapse to perijunctional regions, which are sites of AChR internalization (Sanes and Lichtman, 2001; Akaaboune et al., 2002). This mechanism could explain, at least in part, the appearance of the αDB−/− postsynaptic membrane in which AChR turnover is abnormally high, density is low, and the distinction between crests and troughs of junctional folds is blurred (Grady et al., 2000; Akaaboune et al., 2002). Here, we show that αDB1 is better able than αDB2 to rescue these synaptic defects in αDB−/− mice, indicating that its unique COOH terminus is important for αDB's synaptic function.

How might αDB act? One possibility is that αDB exerts two distinct effects on the postsynaptic membrane, one mediated by common sequences and one by αDB1-specific sequences. Alternatively, common sequences might mediate all synaptic effects, with αDB1-specific sequences serving to enhance their efficacy. For example, even though regions common to αDB1 and 2 bind both utrophin and α-syntrophin, there is some evidence that αDB1 associates more tightly with both proteins than does αDB2 (Balasubramanian et al., 1998; Peters et al., 1998) (Fig. 6). These differences are likely to be relevant because AChR density is decreased in the absence of utrophin (Deconinck et al., 1997a, Grady et al., 1997a) and mice lacking α1-syntrophin have postsynaptic defects similar to those in αDB−/− mice (Adams et al., 2000). Thus, sequences in the unique COOH terminus of αDB1 could enhance the ability of common sequences to bind utrophin and syntrophin, thereby enhancing αDB1's ability to stabilize the postsynaptic membrane.

αDB phosphorylation and synaptic plasticity

Replacement of three tyrosine residues in αDB1's unique COOH-terminal domain by phenylalanine decreased its synaptic efficacy. These residues are the major, if not the only sites of tyrosine phosphorylation in αDB1 (Balasubramanian et al., 1998) (Fig. 7 A). Our results, therefore, provide strong evidence that αDB1 function is modulated by phosphorylation. Phosphorylation might alter the conformation of neighboring sequences to affect their affinity for other proteins (as suggested by modeling studies of Balasubramanian et al., 1998) or may serve to recruit adaptor or signaling proteins as occurs in numerous other phosphoproteins.

Our interest in αDB1 phosphorylation stems from the growing realization that even though mature synapses are remarkably stable, they are not inert. Instead, several of their features, most notably the distribution and density of their postsynaptic receptors, can change rapidly and dramatically in response to altered input (Sheng and Lee, 2001). At the NMJ, the t1/2 of AChRs increases, and their density begins to decrease within 1 h after imposition of complete paralysis (Akaaboune et al., 1999). AChR turnover and density are similarly affected in αDB−/− mice, suggesting that αDB is part of the regulatory mechanism. However, actual loss of αDB is unlikely to be a physiological mechanism for such rapid activity-dependent alterations. On the other hand, altered efficacy of αDB1 by changes in its phosphorylation state could affect AChR mobility quickly, reversibly, and in an activity-dependent fashion.

Several tyrosine kinases have been implicated in postsynaptic structure: erbB and ephA kinases are concentrated in the postsynaptic membrane; MuSK plays a critical role in postsynaptic differentiation; src and fyn modulate AChR stability in vitro; and trkB affects AChR distribution in vivo (DeChiara et al., 1996; Gonzalez et al., 1999; Buonanno and Fischbach, 2001; Lai et al., 2001; for review see Sanes and Lichtman, 2001; Smith et al., 2001). It will be interesting to learn whether αDB1 is a substrate for any of these kinases and whether activators of the kinases (neuregulin for erbBs, ephrinA for ephA, agrin for MuSK, and BDNF for trkB) affect αDB1 phosphorylation. In addition, in view of numerous reports implicating tyrosine kinases in central synaptic plasticity and the presence of DGC components, including αDB and βDB, at central synapses (Blake and Kroger, 2000; Levi et al., 2002) it is intriguing to consider the possibility that similar mechanisms act there.

Materials and methods

Generation of transgenic mice

To generate the αDB1 expression vector, two cDNA clones (16.1A and 14.1.2 [Enigk and Maimone, 1999]) were isolated from a BC3H1 mouse muscle cDNA library and ligated. The 3′ end of the cDNA, including the stop codon and ∼125 bp of the 3′ UTR, was generated by RT-PCR from mouse muscle RNA. The entire coding region was then subcloned first into the SalI/NotI sites of pBK-RSV (Stratagene) and then into a pEtCAT vector, which contains 3.3 kb of regulatory sequences from the mouse muscle creatine kinase gene, extending from −3,300 to +7 with respect to the transcriptional start site (Jaynes et al., 1988) (a gift from S. Hauschka, University of Washington, Seattle, WA). In addition, the vector contains an SV40/polyadenylation sequence. To generate the αDB2 expression vector, a full-length clone was isolated from the BC3H1 library, subcloned into the EcoRI site of pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene) and then into pEtCAT.

Linearized constructs were injected into C57BL6 oocytes at the Washington University Mouse Genetics Core. Four independent lines of mice carrying the αDB1 construct (tgDB1) and six independent lines carrying the αDB2 construct (tgDB2) were identified by PCR. Each line was bred onto an αDB−/− background (Grady et al., 1999). αDB−/−,tgDB1 line was also bred to mdx mice and to αDB−/−,tgDB2 mice.

Histology

For bright field microscopy, muscles were frozen in liquid nitrogen–cooled isopentane and cross sectioned in a cryostat at 8 μm; sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemistry, sections from the same muscles were stained with primary antibody diluted in PBS/1% BSA/2% normal goat serum for 2 h and then rinsed with PBS. Sections were then incubated 1 h with a mixture of fluorescein-conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG (Alexa 488; Molecular Probes) and rBTX (Molecular Probes), rinsed in PBS, and mounted using 0.1% p-phenylenediamine in glycerol/PBS. For en face views, sternomastoid muscles were fixed in 1% PFA in PBS for 20 min, cryoprotected in sucrose, frozen, and sectioned en face at 40 μm. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to αDB1 (αDB638), αDB2, and α1-syntrophin (SYN17) were gifts from Stanley Froehner, University of Washington (Peters et al., 1997b). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies that recognize all forms of αDB (called pan-αDB here) were generated using a recombinant fragment of αDB and affinity purified using the immunogen (Grady et al., 1997a). Rabbit polyclonal antibody to nNOS was purchased from Immunostar Inc. (no. 24287). Illustrations were prepared in Adobe Photoshop®.

For ultrastructural studies, tibialis anterior muscles were fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde/4% PFA in PBS, washed, refixed in 1% OsO4, dehydrated, and embedded in resin. Thin sections were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate. Sections were systematically scanned in the electron microscope, and all MTJs encountered were measured from the micrographs. Muscles from two to four animals were analyzed per genotype.

Immunoblotting

For immunoblots, sternomastoid muscle was homogenized and sonicated in extraction buffer (PBS, 5 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, and protease inhibitors [CompleteMini; Roche]). Protein concentration of whole muscle extract was determined by a BCA protein assay (Pierce Chemical Co.). Equal amounts of protein (50 μg) were resolved on 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gels and incubated with monoclonal antibody to αDB (D62320; Transduction Laboratories). This antibody was detected with goat anti–mouse IgG1 peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Roche) using ECL (NEN).

Quantitative fluorescence microscopy and in vivo imaging

AChR density at NMJs was calculated using the quantitative fluorescence imaging technique described by Akaaboune et al. (1999)(2002). Briefly, mice were anesthetized, and the exposed sternomastoid muscle was saturated with rBTX (5 μg/ml) for 60 min, and superficial NMJs were viewed with a fluorescence microscope. The fluorescence intensity at synapses was compared with that of a nonbleaching fluorescent standard viewed concurrently. To study loss rate of AChRs, a nonblocking dose of rBTX (0.1 μg/ml) was applied to the sternomastoid for 2–5 min and 1 d later, after unbound toxin had cleared, individual synapses were imaged. Total fluorescence intensity at the first view was expressed as 100%. Mice were then reexamined 3 d later, and total fluorescence intensity of the previously identified junctions was measured (Akaaboune et al., 1999). The use of a nonblocking dose ensured that the turnover rate was not affected by paralysis.

Comparison of transgenic lines

Of the four αDB1 transgenic lines examined on a αDB−/− background, two (lines 12 and 14) expressed detectable αDB1. More than 95% of muscle fibers expressed αDB in line 12 but only 50–70% in line 14. However, both lines were similar in that expression of the transgene prevented dystrophy in transgene-positive fibers and led to a more normal synaptic structure than observed in αDB−/−,tgDB2 transgenic lines. Of the six αDB2 lines examined, expression was detected in three (lines 11A, 11B, and 28). Results from αDB−/−,tgDB2 lines 11B and 28 were similar in all respects tested (muscle and synaptic structure and AChR turnover). Levels of transgene expression were lower in line 11A, and only ∼70% of muscle fibers in αDB−/−,tgDB2 line 11A mice were transgene positive. No central nuclei occurred in these transgene-positive fibers, indicating rescue of the dystrophic phenotype, but rescue of the synaptic phenotype was significantly less in this line than in any of the other lines tested. In summary, all five transgenic lines tested exhibited rescue of the dystrophic phenotype, and both tgDB1 lines rescued synaptic defects more effectively than any of the tgDB2 lines. Based on these results, we studied αDB−/−,tgDB1 line 12 and αDB−/−,tgDB2 line 28 in greatest detail.

In vitro and in vivo transfection

Expression vector GFP-DB1 was constructed by cloning the αDB1 cDNA described above into a pEGFP-C1 plasmid (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.), generating a fusion protein with GFP attached to the NH2 terminus of αDB1. To create GFP-DB1-P3−, PCR-directed mutagenesis was used to change three terminal tyrosine residues (aa 698, 706, and 723) to phenylalanine. These residues correspond to aa 685, 693 and 710, which were shown to be major if not sole sites of tyrosine phosphorylation in Torpedo αDB (Balasubramanian et al., 1998).

The αDB1 constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine Plus transfection reagent (Invitrogen) and 4 μg of DNA per 10-cm dish. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. Immediately before collection, cells were subjected to pervanadate stimulation to inhibit tyrosine phosphatases as described by Balasubramanian et al. (1998). Soluble fractions were collected and immunopurified by incubating with GFP specific antibodies (A-11120; Molecular Probes) for 1 h at 4°C, and then with protein G sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) for 3 h more. Beads were precipitated, washed, resuspended in 1× sample buffer, boiled for 4 min, and subjected to immunoblotting (see above). αDB was detected using an mAb (D62320, Transduction Labs), and phosphotyrosine was detected using PY20 antibody (610000, Transduction Labs).

For in vivo electroporation, DNA was dissolved into normal saline (0.9% NaCl) at a concentration of 2 μg/μl. Mice were anesthetized, and their tibialis anterior muscles were injected transcutaneously with 25 μl of a 4 U/μL bovine hyaluronidase/saline solution (Sigma-Aldrich) as recommended by McMahon et al. (2001). 2 h later, the mice were reanesthetized, the tibialis was exposed, injected with 25 μl of DNA (50 μg), and electroporated (Aihara and Miyazaki, 1998). Electroporation was performed with a pair of 0.2-mm diameter stainless steel needle electrodes (Genetronics) held 4 mm apart and inserted on either side of the injection site parallel to the muscle fibers. Ten 80 V pulses, each 20 ms in duration, were delivered at a frequency of 1 Hz, giving a field strength of ∼200 V/cm (BTX electroporator). Muscles were dissected 10–14 d after injection and fixed for 20 min in 1% PFA. Fiber bundles exhibiting GFP fluorescence were isolated under a fluorescence dissecting microscope, stained with rBTX and viewed by both light (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) and confocal (Olympus) microscopy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Renate Lewis for tissue culture assistance, Jeanette Cunningham for EM, and the Washington University Mouse Genetics Core facility for transgenic mice production, and Cheryl Rivers for manuscript assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (to R.M. Grady and J.R. Sanes) and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute undergraduate fellowship to A.L. Cohen.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: AChR, acetylcholine receptor; DB, dystrobrevin; DGC, dystrophin–glycoprotein complex; MTJ, myotendinous junction; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; nNOS, nitric oxide synthase; rBTX, rhodamine α-bungarotoxin.

References

- Adams, M.E., N. Kramarcy, S.P. Krall, S.G. Rossi, R.L. Rotundo, R. Sealock, and S.C. Froehner. 2000. Absence of alpha-syntrophin leads to structurally aberrant neuromuscular synapses deficient in utrophin. J. Cell Biol. 150:1385–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aihara, H., and J. Miyazaki. 1998. Gene transfer into muscle by electroporation in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:867–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaaboune, M., S.M. Culican, S.G. Turney, and J.W. Lichtman. 1999. Rapid and reversible effects of activity on acetylcholine receptor density at the neuromuscular junction in vivo. Science. 286:503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaaboune, M., R.M. Grady, S.G. Turney, J.R. Sanes, and J.W. Lichtman. 2002. Neurotransmitter receptor dynamics studied in vivo by reversible photo-unbinding of fluorescent ligands. Neuron. 34:865–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, D.W., and M.W. Salter. 2001. NMDA receptor regulation by Src kinase signalling in excitatory synaptic transmission and plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11:336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, S., E.T. Fung, and R.L. Huganir. 1998. Characterization of the tyrosine phosphorylation and distribution of dystrobrevin isoforms. FEBS Lett. 432:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson, M.A., S.E. Newey, E. Martin-Rendon, R. Hawkes, and D.J. Blake. 2001. Dysbindin, a novel coiled-coil-containing protein that interacts with the dystrobrevins in muscle and brain. J. Biol. Chem. 276:24232–24241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D.J., and S. Kroger. 2000. The neurobiology of duchenne muscular dystrophy: learning lessons from muscle? Trends Neurosci. 23:92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D.J., R. Nawrotzki, M.F. Peters, S.C. Froehner, and K.E. Davies. 1996. Isoform diversity of dystrobrevin, the murine 87-kDa postsynaptic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7802–7810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D.J., R. Nawrotzki, N.Y. Loh, D.C. Gorecki, and K.E. Davies. 1998. beta-dystrobrevin, a member of the dystrophin-related protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:241–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D.J., A. Weir, S.E. Newey, and K.E. Davies. 2002. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol. Rev. 82:291–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonanno, A., and G.D. Fischbach. 2001. Neuregulin and Erbβ receptor signaling pathways in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11:287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers, T.J., L.M. Kunkel, and S.C. Watkins. 1991. The subcellular distribution of dystrophin in mouse skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle. J. Cell Biol. 115:411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, C., G.D. Fischbach, and J.B. Cohen. 1989. A novel 87,000-Mr protein associated with acetylcholine receptors in Torpedo electric organ and vertebrate skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 109:1753–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.J., S.T. Iannaccone, K.S. Lau, B.S. Masters, T.J. McCabe, K. McMillan, R.C. Padre, M.J. Spencer, J.G. Tidball, and J.T. Stull. 1996. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase and dystrophin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93:9142–9147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q., R. Sealock and, H.B. Peng. 1990. A protein homologous to the Torpedo postsynaptic 58K protein is present at the myotendinous junction. J. Cell Biol. 110:2061–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, R.D., and K.P. Campbell. 2000. Molecular basis of muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve. 23:1456–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, G.E., J.A. Faulkner, R.H. Crosbie, K.P. Campbell, S.C. Froehner, and J.S. Chamberlain. 2000. Assembly of the dystrophin-associated protein complex does not require the dystrophin COOH-terminal domain. J. Cell Biol. 150:1399–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie, R.H., C.S. Lebakken, K.H. Holt, D.P. Venzke, V. Straub, J.C. Lee, R.M. Grady, J.S. Chamberlain, J.R. Sanes, and K.P. Campbell. 1999. Membrane targeting and stabilization of sarcospan is mediated by the sarcoglycan subcomplex. J. Cell Biol. 145:153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChiara, T.M., D.C. Bowen, D.M. Valenzuela, M.V. Simmons, W.T. Poueymirou, S. Thomas, E. Kinetz, D.L. Compton, E. Rojas, J.S. Park, et al. 1996. The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK is required for neuromuscular junction formation in vivo. Cell. 85:501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deconinck, A.E., A.C. Potter, J.M. Tinsley, S.J. Wood, R. Vater, C. Young, L. Metzinger, A. Vincent, C.R. Slater, and K.E. Davies. 1997. a. Postsynaptic abnormalities at the neuromuscular junctions of utrophin-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 136:883–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deconinck, A.E., J.A. Rafael, J.A. Skinner, S.C. Brown, A.C. Potter, L. Metzinger, D.J. Watt, J.G. Dickson, J.M. Tinsley, and K.E. Davies. 1997. b. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 90:717–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duclos, F., V. Straub, S.A. Moore, D.P. Venzke, R.F. Hrstka, R.H. Crosbie, M. Durbeej, C.S. Lebakken, A.J. Ettinger, J. van der Meulen, et al. 1998. Progressive muscular dystrophy in alpha-sarcoglycan–deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 142:1461–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enigk, R.E., and M.M. Maimone. 1999. Differential expression and developmental regulation of a novel alpha-dystrobrevin isoform in muscle. Gene. 238:479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enigk, R.E., and M.M. Maimone. 2001. Cellular and molecular properties of alpha-dystrobrevin in skeletal muscle. Front. Biosci. 6:D53–D64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti, J.M., and K.P. Campbell. 1993. A role for the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex as a transmembrane linker between laminin and actin. J. Cell Biol. 122:809–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti, J.M., K. Ohlendieck, S.D. Kahl, M.G. Gaver, and K.P. Campbell. 1990. Deficiency of a glycoprotein component of the dystrophin complex in dystrophic muscle. Nature. 345:315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M., F.P. Ruggiero, Q. Chang, Y.J. Shi, M.M. Rich, S. Kraner, and R.J. Balice-Gordon. 1999. Disruption of Trkb-mediated signaling induces disassembly of postsynaptic receptor clusters at neuromuscular junctions. Neuron. 24:567–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, R.M., J.P. Merlie, and J.R. Sanes. 1997. a. Subtle neuromuscular defects in utrophin-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 136:871–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, R.M., H. Teng, M.C. Nichol, J.C. Cunningham, R.S. Wilkinson, and J.R. Sanes. 1997. b. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 90:729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, R.M., R.W. Grange, K.S. Lau, M.M. Maimone, M.C. Nichol, J.T. Stull, and J.R. Sanes. 1999. Role for alpha-dystrobrevin in the pathogenesis of dystrophin-dependent muscular dystrophies. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady, R.M., H. Zhou, J.M. Cunningham, M.D. Henry, K.P. Campbell, and J.R. Sanes. 2000. Maturation and maintenance of the neuromuscular synapse: genetic evidence for roles of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex. Neuron. 25:279–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack, A.A., C.T. Ly, F. Jiang, C.J. Clendenin, K.S. Sigrist, R.L. Wollmann, and E.M. McNally. 1998. Gamma-sarcoglycan deficiency leads to muscle membrane defects and apoptosis independent of dystrophin. J. Cell Biol. 142:1279–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, C., P.D. Cote, S.G. Rossi, R.L. Rotundo, and S. Carbonetto. 2001. The dystroglycan complex is necessary for stabilization of acetylcholine receptor clusters at neuromuscular junctions and formation of the synaptic basement membrane. J. Cell Biol. 152:435–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, J.B., J.E. Johnson, J.N. Buskin, C.L. Gartside, and S.D. Hauschka. 1988. The muscle creatine kinase gene is regulated by multiple upstream elements, including a muscle-specific enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.A., and M.J. Werle. 2000. Nitric oxide is a downstream mediator of agrin-induced acetylcholine receptor aggregation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 16:649–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameya, S., Y. Miyagoe, I. Nonaka, T. Ikemoto, M. Endo, K. Hanaoka, Y. Nabeshima, and S. Takeda. 1999. alpha1-syntrophin gene disruption results in the absence of neuronal-type nitric-oxide synthase at the sarcolemma but does not induce muscle degeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 274:2193–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, T.S., S.C. Watkins, P. Chafey, J. Chelly, F.M. Tome, M. Fardeau, J.C. Kaplan, and L.M. Kunkel. 1991. Immunolocalization and developmental expression of dystrophin related protein in skeletal muscle. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1:185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramarcy, N.R., and R. Sealock. 2000. Syntrophin isoforms at the neuromuscular junction: developmental time course and differential localization. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 15:262–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, K.O., F.C. Ip, J. Cheung, A.K. Fu, and N.Y. Ip. 2001. Expression of Eph receptors in skeletal muscle and their localization at the neuromuscular junction. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 17:1034–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law, D.J., A. Caputo, and J.G. Tidball. 1995. Site and mechanics of failure in normal and dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 18:216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi, S., R.M. Grady, M.D. Henry, K.P. Campbell, J.R. Sanes, and A.M. Craig. 2002. Dystroglycan is selectively associated with inhibitory GABAergic synapses but is dispensable for their differentiation. J. Neurosci. 22:4274–4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh, N.Y., S.E. Newey, K.E. Davies, and D.J. Blake. 2000. Assembly of multiple dystrobrevin-containing complexes in the kidney. J. Cell Sci. 113:2715–2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, J.M., E. Signori, K.E. Wells, V.M. Fazio, and D.J. Wells. 2001. Optimisation of electrotransfer of plasmid into skeletal muscle by pretreatment with hyaluronidase–increased expression with reduced muscle damage. Gene Ther. 8:1264–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miosge, N., C. Klenczar, R. Herken, M. Willem, and U. Mayer. 1999. Organization of the myotendinous junction is dependent on the presence of alpha7beta1 integrin. Lab. Invest. 79:1591–1599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Y., T.G. Thompson, J.R. Guyon, H.G. Lidov, M. Brosius, M. Imamura, E. Ozawa, S.C. Watkins, and L.M. Kunkel. 2001. Desmuslin, an intermediate filament protein that interacts with alpha-dystrobrevin and desmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:6156–6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moukhles, H., and S. Carbonetto. 2001. Dystroglycan contributes to the formation of multiple dystrophin-like complexes in brain. J. Neurochem. 78:824–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrotzki, R., N.Y. Loh, M.A. Ruegg, K.E. Davies, and D.J. Blake. 1998. Characterisation of alpha-dystrobrevin in muscle. J. Cell Sci. 111:2595–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newey, S.E., A.O. Gramolini, J. Wu, P. Holzfeind, B.J. Jasmin, K.E. Davies, and D.J. Blake. 2001. a. A novel mechanism for modulating synaptic gene expression: differential localization of alpha-dystrobrevin transcripts in skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 17:127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newey, S.E., E.V. Howman, C.P. Ponting, M.A. Benson, R. Nawrotzki, N.Y. Loh, K.E. Davies, and D.J. Blake. 2001. b. Syncoilin, a novel member of the intermediate filament superfamily that interacts with alpha-dystrobrevin in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 276:6645–6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlendieck, K., J.M. Ervasti, K. Matsumura, S.D. Kahl, C.J. Leveille, and K.P. Campbell. 1991. Dystrophin-related protein is localized to neuromuscular junctions of adult skeletal muscle. Neuron. 7:499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.F., K.F. O'Brien, H.M. Sadoulet-Puccio, L.M. Kunkel, M.E. Adams, and S.C. Froehner. 1997. a. beta-dystrobrevin, a new member of the dystrophin family. Identification, cloning, and protein associations. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31561–31569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.F., M.E. Adams, and S.C. Froehner. 1997. b. Differential association of syntrophin pairs with the dystrophin complex. J. Cell Biol. 138:81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.F., H.M. Sadoulet-Puccio, R.M. Grady, N.R. Kramarcy, L.M. Kunkel, J.R. Sanes, R. Sealock, and S.C. Froehner. 1998. Differential membrane localization and intermolecular associations of alpha-dystrobrevin isoforms in skeletal muscle. J. Cell Biol. 142:1269–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge, J.C., J.G. Tidball, K. Ahl, D.J. Law, and W.L. Rickoll. 1994. Modifications in myotendinous junction surface morphology in dystrophin-deficient mouse muscle. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 61:58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoulet-Puccio, H.M., T.S. Khurana, J.B. Cohen, and L.M. Kunkel. 1996. Cloning and characterization of the human homologue of a dystrophin related phosphoprotein found at the Torpedo electric organ post-synaptic membrane. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5:489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoulet-Puccio, H.M., M. Rajala, and L.M. Kunkel. 1997. Dystrobrevin and dystrophin: an interaction through coiled-coil motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:12413–12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes, J.R., and J.W. Lichtman. 2001. Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2:791–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, M., and S.H. Lee. 2001. AMPA receptor trafficking and the control of synaptic transmission. Cell. 105:825–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.L., P. Mittaud, E.D. Prescott, C. Fuhrer, and S.J. Burden. 2001. Src, Fyn, and Yes are not required for neuromuscular synapse formation but are necessary for stabilization of agrin-induced clusters of acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci. 21:3151–3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, H.H., H.L. Sweeney, J.B. Shrager, H.C. Maguire, R.A. Panettieri, B. Petrof, M. Narusawa, J.M. Leferovich, J.T. Sladky, and A.M. Kelly. 1991. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature. 352:536–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub, V., A.J. Ettinger, M. Durbeej, D.P. Venzke, S. Cutshall, J.R. Sanes, and K.P. Campbell. 1999. epsilon-sarcoglycan replaces alpha-sarcoglycan in smooth muscle to form a unique dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 274:27989–27996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, K.R., J.B. Cohen, and R.L. Huganir. 1993. The 87K postsynaptic membrane protein from Torpedo is a protein-tyrosine kinase substrate homologous to dystrophin. Neuron. 10:511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, M., and E. Ozawa. 1990. Glycoprotein complex anchoring dystrophin to sarcolemma. J. Biochem. (Tokyo). 108:748–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, M., H. Hama, M. Ishikawa-Sakurai, M. Imamura, Y. Mizuno, K. Araishi, E. Wakabayashi-Takai, S. Noguchi, T. Sasaoka, and E. Ozawa. 2000. Biochemical evidence for association of dystrobrevin with the sarcoglycan-sarcospan complex as a basis for understanding sarcoglycanopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9:1033–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]