Abstract

Endocytic cargo such as the transferrin receptor is incorporated into clathrin-coated pits by associating, via tyrosine-based motifs, with the AP2 complex. Cargo–AP2 interactions occur via the μ2 subunit of AP2, which needs to be phosphorylated for endocytosis to occur. The most likely role for μ2 phosphorylation is in cargo recruitment because μ2 phosphorylation enhances its binding to internalization motifs. Here, we investigate the control of μ2 phosphorylation. We identify clathrin as a specific activator of the μ2 kinase and, in permeabilized cells, we show that ligand sequestration, driven by exogenous clathrin, results in elevated levels of μ2 phosphorylation. Furthermore, we show that AP2 containing phospho-μ2 is mainly associated with assembled clathrin in vivo, and that the level of phospho-μ2 is strongly reduced in a chicken B cell line depleted of clathrin heavy chain. Our results imply a central role for clathrin in the regulation of cargo selection via the modulation of phospho-μ2 levels.

Keywords: regulation; endocytosis; sorting; coated vesicles; phosphorylation

Introduction

Clathrin-coated pits represent the major port of entry into higher eukaryotic cells (Conner and Schmid, 2003a). Within the clathrin lattice, the AP2 adaptor complex interprets signals in the cytoplasmic domains of transmembrane cargo, thus allowing its inclusion into coated pits. The AP2 complex is composed of two 100-kD subunits (α- and β2-adaptin), a 50-kD subunit (μ2), and a 17-kD subunit (σ2; Kirchhausen, 1999). While clathrin binds to AP2 via the β2 subunit (Shih et al., 1995), the μ2 subunit interacts with cargo, specifically recognizing tyrosine-based internalization motifs (Yxxφ; Y, tyrosine; φ, bulky hydrophobic; x, polar) in the cytoplasmic tails of receptors (Ohno et al., 1995; Owen and Evans, 1998). AP2 recruitment to the plasma membrane appears to be mediated at least partly because of interactions with phosphoinositides (Gaidarov and Keen, 1999).

Recent reports have demonstrated that μ2 phosphorylation regulates the interaction of AP2 with cargo. In permeabilized cells, it was shown that μ2 phosphorylation was required for the incorporation of transferrin bound to its receptor into newly formed coated pits (Olusanya et al., 2001). Furthermore, transfection of HeLa cells with mutant forms of μ2, which could not be phosphorylated, resulted in an inhibition of transferrin endocytosis, indicating the importance of μ2 phosphorylation in vivo (Olusanya et al., 2001). Other complementary analyses, measuring affinities of AP2 for peptides containing tyrosine-based internalization motifs, demonstrated that μ2 phosphorylation significantly enhances the association of AP2 with these motifs (Ricotta et al., 2002). The x-ray structure of the AP2 complex (lacking the hinge and ear domains of α- and β2-adaptin) has revealed that the binding site for cargo on μ2 is partially blocked by β2-adaptin in the unphosphorylated complex (Collins et al., 2002). This suggests that a conformational change is required to reveal the binding site, and such a change could be effected by phosphorylation. In particular, the phosphorylation site on μ2, Thr156 (Pauloin and Thurieau, 1993), is located on an exposed loop of μ2 and is thus ideally situated to elicit such a change (Collins et al., 2002). Interestingly, the paradigm of phosphorylation of μ subunits regulating cargo interactions has been further supported by the demonstration that phosphorylation of μ1, the medium subunit of the AP1 adaptor complex found in clathrin-coated vesicles budding from the TGN, also enhances its association with cargo (Ghosh and Kornfeld, 2003).

These data support the premise that reversible cycles of phosphorylation are important in the control of the coated vesicle cycle. However, they raise the question of how μ2 phosphorylation is itself regulated so that AP2 adaptors are activated only in the correct functional context. Previous reports have shown that AP2 within clathrin coats has a higher affinity for sorting signals, suggesting that the processes of coated vesicle formation might be coupled to cargo sorting (Rapoport et al., 1997). Here, we provide a mechanistic explanation for how this occurs by showing that clathrin can directly regulate the levels of phosphorylated μ2 in vivo and in vitro via activation of the μ2 kinase.

Results and discussion

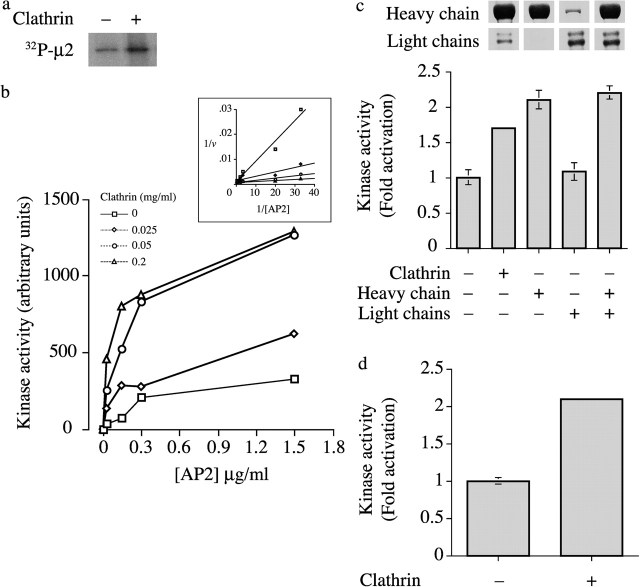

AAK1 is a likely candidate for the kinase that phosphorylates μ2 in vivo and is closely associated with AP2 (Conner and Schmid, 2002; Ricotta et al., 2002). It is composed of an NH2-terminal serine/threonine kinase domain and a COOH-terminal domain containing motifs mediating both AP2 binding (Owen et al., 1999) and clathrin binding (Morgan et al., 2000). Addition of purified clathrin to incubations containing μ2 kinase and AP2 adaptor complex resulted in a pronounced increase in μ2 phosphorylation (Fig. 1 a). To investigate the mechanism of kinase activation, we isolated μ2 kinase and AP2 under conditions that dissociate the kinase from the AP2 complex (Pauloin and Thurieau, 1993), and measured μ2 kinase activity in the presence of increasing concentrations of clathrin and AP2 substrate (Fig. 1 b). These data showed that clathrin activates the μ2 kinase by reducing the apparent Km for AP2 without affecting the apparent Vmax (Fig. 1 b, inset). Clathrin may either increase the affinity of the kinase for μ2 or may remove a competitive inhibitor, e.g., a pseudosubstrate as is common for many serine/threonine kinases (Kemp and Pearson, 1991). As a member of the Ark/Prk family of protein kinases, μ2 kinase recognizes the consensus sequence (L(I)xxQxTG) (Pauloin and Thurieau, 1993; Smythe and Ayscough, 2003), and thus one potential pseudosubstrate is the sequence LVNQSLG at the COOH terminus. In the AAK1 primary sequence, the NH2- and COOH-terminal domains are connected via a long central region unusually rich in prolines, alanines, and glutamines (Conner and Schmid, 2002). Sequences with this composition are generally flexible (Perham et al., 1987). Hence, this region is ideally suited to allow the activated NH2-terminal kinase domain the freedom of movement needed to phosphorylate μ2 on AP2 molecules within the tight confines of a coated pit, perhaps while tethered (via its COOH-terminal domain) to a clathrin molecule (see Fig. 4).

Figure 1.

Clathrin activates the μ2 kinase. (a) Autoradiography showing incorporation of 32P into μ2 after incubation of the μ2 kinase with AP2 in the presence or absence of clathrin. (b) The activity of the μ2 kinase was assayed using AP2 as a substrate in the presence of increasing concentrations of clathrin as indicated. μ2 kinase activity is expressed in arbitrary units. Results are from a typical experiment where each point is the mean of two samples that differed by <10%. The inset shows a double-reciprocal plot of 1/v versus 1/[AP2] for clathrin activation of μ2 kinase. (c) Kinase assay showing the effect of adding clathrin, heavy chain only, light chain, or reconstituted heavy and light chains. Results are from a typical experiment where each point is the mean and range of two samples. The Coomassie gels indicate the relative proportions of clathrin heavy and light chains added to each incubation. (d) Kinase assay using a peptide substrate showing activation by clathrin. Incubations contained 0.5 μM peptide (EEQSQITSQVTCQIGWRRR) and 0.25 mg/ml clathrin. Results are from a typical experiment where each point is the mean and range of two samples.

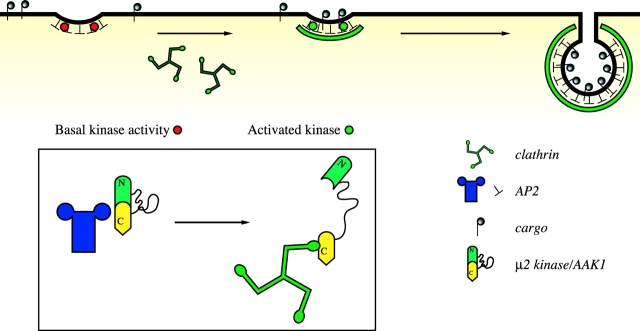

Figure 4.

Model for the role of clathrin activation of the μ2 kinase. AP2 recruitment to the membrane occurs independently of μ2 Thr156 phosphorylation, most likely via interactions with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and other protein components at the membrane. At this stage, the μ2 kinase has basal activity (red circles), and hence, there is minimal cargo recruitment. After clathrin recruitment, the μ2 kinase is activated (green circles) and maximal cargo recruitment occurs. The insert indicates a possible mechanism by which clathrin may activate the μ2 kinase, which is most likely to be AAK1, by inducing a conformational change in AAK1 so that the flexible P-, A-, G-, Q-rich domain can extend allowing the NH2-terminal kinase domain free access to phosphorylate μ2 within the coated pit.

However, previous reports have suggested that clathrin light chains might regulate μ2 phosphorylation (Pauloin and Jolles, 1984). To investigate whether light chains could activate the purified kinase, we separated clathrin heavy chain and light chains as described previously (Winkler and Stanley, 1983), and tested each separately and together in a kinase assay. We found that clathrin heavy chain was necessary and sufficient to activate the kinase. Light chains alone showed no activation (Fig. 1 c; light chains prepared by heat denaturation were also inactive [unpublished data]). This result is expected given the spatial organization of coated pits with light chains on the outside of the lattice and is consistent with the model described above. To rule out the possibility that the enhancement of μ2 phosphorylation was caused by clathrin aggregating the AP2 complexes, we tested the clathrin activation of μ2 kinase using a peptide substrate corresponding to residues 148–161 of μ2 and found that clathrin could also enhance phosphorylation of this substrate (Fig. 1 d).

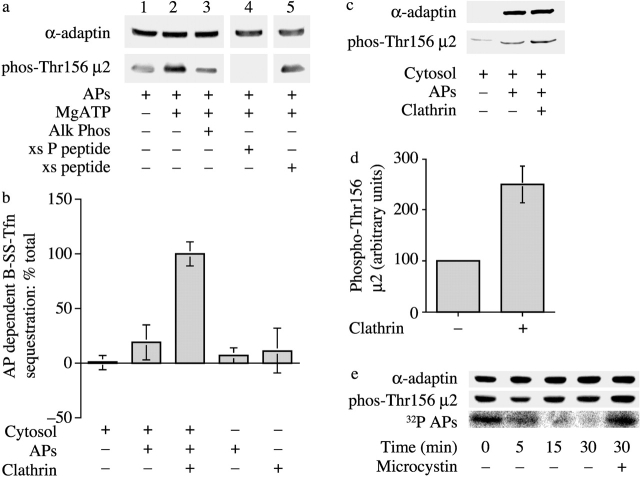

To pursue the role of phosphorylated μ2 in coated pit formation, we generated anti-peptide antibodies to a phosphopeptide that corresponds to the Thr156 phosphorylation site on μ2. In addition, we purified AP2 from bovine brain, under conditions whereby μ2 kinase remains associated with the AP2 complex (Campbell et al., 1984). Untreated AP2, or AP2 that had been incubated with Mg2+ATP, were immunoblotted either with an antibody that recognizes the brain-specific insert of α-adaptin or with the anti-phospho-Thr156 μ2 antibodies (Fig. 2 a). Although blotting with the α-adaptin antibodies showed that equal amounts of AP2 were present in each lane, immunoreactivity with anti-phospho-Thr156 μ2 antibodies was maximal where AP2 had been incubated with Mg2+ATP (Fig. 2 a, lane 2). Treatment of the phosphorylated complex with alkaline phosphatase resulted in a loss of immunoreactivity (Fig. 2 a, lane 3). Reactivity against phosphorylated μ2 was also lost when the antibody was incubated in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of phosphopeptide (Fig. 2 a, lane 4), but not when incubated with nonphosphorylated peptide (Fig. 2 a, lane 5). Together, these data confirm that the antibody recognizes phospho-Thr156 μ2 only.

Figure 2.

Clathrin activation of the μ2 kinase is required for coated pit function in vitro. (a) Characterization of phospho-Thr156 μ2 antibodies. APs were incubated with Mg2+ATP for 15 min at 30°C, and then in the presence or absence of calf alkaline phosphatase for 10 min at 30°C before immunoblotting. The blots were probed with antibodies that recognize the brain-specific insert of α-adaptin or with antibodies generated against phospho-Thr156 μ2. Lane 4, anti-phospho-Thr156 μ2 antibodies were incubated in the presence of a 100-fold molar excess of phosphorylated peptide used to generate the antibodies. Lane 5, anti-phospho-Thr156 μ2 antibodies were incubated with 100-fold molar excess of the nonphosphorylated peptide. (b) The sequestration of biotinylated transferrin into new clathrin coated pits was measured by inaccessibility to avidin with the modifications described in Materials and methods. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of three experiments. (c) Permeabilized cell membranes incubated as indicated were reisolated and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies against the brain-specific insert of α-adaptin or with anti-phospho-Thr156 μ2 antibodies. (d) A histogram showing quantitation of the levels of μ2 phosphorylation in permeabilized cell membranes in the presence or absence of clathrin. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD of three separate experiments. (e) μ2 undergoes cycles of phosphorylation during cargo sequestration. Permeabilized cell assay mixes were incubated APs that were phosphorylated before either with ATP (middle) or [32P]ATP (bottom) and in the absence or presence of microcystin as indicated. The membranes were reisolated at the indicated times, and after SDS-PAGE, the amount of phosphorylated μ2 was measured using phospho-Thr156 μ2 antibodies or by autoradiography.

We used these phosphospecific antibodies to investigate whether clathrin might regulate μ2 phosphorylation in the context of a coated pit using a permeabilized cell assay that reconstitutes the sequestration of cargo into newly formed coated pits (Smythe et al., 1992; McLauchlan et al., 1998). Briefly, this assay uses biotinylated transferrin that binds to transferrin receptors on the cell surface. The sequestration of biotinylated transferrin into newly formed coated pits is measured by inaccessibility to exogenously added avidin. In the permeabilized cell system, new coated pit formation is dependent on the addition of purified AP2 when AP2 is limiting in the cytosol. Previous experiments have demonstrated that μ2 phosphorylation is required for ligand sequestration into newly formed coated pits (Olusanya et al., 2001) and that clathrin required for new pit formation is recruited from the permeabilized cell membranes (McLauchlan et al., 1998). We modified the assay system to make it more dependent on the addition of exogenous clathrin by incubating membrane and soluble components with the protein phosphatase inhibitor microcystin (see Materials and methods). Fig. 2 b shows that when treated under these conditions, exogenous clathrin is now required for coat protein–dependent stimulation of sequestration, presumably because dephosphorylation is required for clathrin recruitment from the permeabilized cell membranes. Membranes from permeabilized cells incubated under the conditions shown in Fig. 2 b were reisolated from the assay mixes and subjected to immunoblotting (Fig. 2 c). The blots were probed with an antibody that recognizes the brain-specific insert of α-adaptin, and so recognized only AP2 that was added to the assay mix in purified form or in cytosol. Incubations performed in the presence of APs show that added AP2 associated with the permeabilized cell membranes and this amount was independent of added clathrin. However, phospho-Thr156 μ2 immunoreactivity was significantly increased (greater than twofold; Fig. 2 d) in those incubations containing clathrin and where ligand sequestration occurs. This indicates that clathrin is needed to maximize phospho-Thr156 μ2 at the plasma membrane, and this correlates with the ability of newly formed clathrin-coated pits to sequester ligand.

When permeabilized cell membranes were incubated with APs prelabeled with [32P]ATP, there was a time-dependent decline in radioactivity that was prevented by microcystin (Fig. 2 e, bottom). This suggests that phosphate turnover was occurring on the μ2 subunit. When this experiment was repeated with APs prelabeled with cold ATP, there was an initial decline in phospho-μ2 immunoreactivity followed by an increase (Fig. 2 e, compare 0 to 5 min). However, the level of phospho-μ2 immunoreactivity after 30 min in the absence of microcystin was less than in its presence for the same time period (Fig. 2 e, middle). This strongly suggests that the level of phospho-μ2 is determined by the net activities of both kinase and phosphatases.

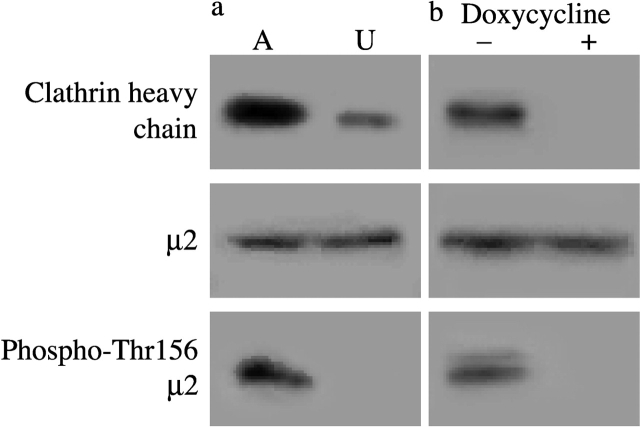

To investigate the connection between clathrin and μ2 phosphorylation in vivo, we examined the level of phospho-Thr156 μ2 in the chicken DT40 B cell line DKO-R. In this cell line, both endogenous alleles of clathrin heavy chain have been inactivated by homologous recombination and replaced with clathrin under the control of a tetracycline-responsive repressor (Wettey et al., 2002). From EST database searches (http://chick.umist.ac.uk), we confirmed that the amino acid sequence of chicken μ2 is 98% identical to the mammalian protein, and shows perfect conservation in the region surrounding Thr156 (unpublished data). We analyzed the distribution of phosphorylated μ2 in assembled and unassembled pools of clathrin prepared from DKO-R cells under clathrin-expressing conditions. Most of the clathrin was found in the assembled fraction (Fig. 3 a), consistent with the high endocytic capacity of the DKO-R cell line (Wettey et al., 2002). Immunoblotting of μ2 showed that the AP2 complex distributed more equally between the assembled and unassembled fractions. However, almost all the phospho-Thr156 μ2 was found in the assembled fraction, indicating that μ2 phosphorylation occurs primarily when AP2 is associated with the assembled pool of clathrin. In DKO-R cells treated with doxycycline for 96 h, clathrin expression was undetectable by immunoblotting (Fig. 3 b). Using a more sensitive clathrin triskelion ELISA (Cheetham et al., 1996), residual expression corresponding to ∼0.5% of the unrepressed level was detected under these conditions (unpublished data). As judged by immunoblotting, clathrin depletion did not affect the level of μ2 (Fig. 3 b) or, in separate experiments, α- and β-adaptin (unpublished data). However, the level of μ2 phosphorylation was strikingly reduced by clathrin removal (Fig. 3 b).

Figure 3.

Clathrin controls μ2 phosphorylation in DKO-R cells. (a) Phosphorylated μ2 is largely associated with the assembled fraction of clathrin. DKO-R cells were homogenized, and membrane (A) and cytosolic (U) fractions were prepared to separate assembled and unassembled pools of clathrin. The fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and after transfer to nitrocellulose were immunoblotted with antibodies to clathrin, μ2, and phospho-Thr156 μ2. (b) Phosphorylated μ2 is substantially reduced in clathrin-depleted DKO-R cells. Exponentially growing chicken DKO-R cells treated for 96 h without (lane 1) or with (lane 2) 0.1 μg/ml doxycycline were lysed and subjected to immunoblotting with antibodies to clathrin, μ2, and phospho-Thr156 μ2.

By activating the μ2 kinase, we propose that clathrin provides a crucial regulatory link between AP2 phosphorylation and functional coated pit assembly (Fig. 4). To explain the low level of phospho-Thr156 μ2 found in cytosolic AP2, we suggest that the μ2 kinase associated with cytosolic AP2 has a low basal activity. This implies that AP2 must first bind the plasma membrane via a cargo-independent interaction, and is consistent with the observation that, in the permeabilized cell system, AP2 bound membranes independently of clathrin, although ligand sequestration was facilitated by clathrin via its effect on μ2 phosphorylation. It is also consistent with our observation that in DKO-R cells, clathrin depletion did not prevent the binding of AP2 to the plasma membrane, but did inhibit endocytosis (Wettey et al., 2002). One likely possibility for this cargo-independent binding is via the phosphoinositide-binding sites of α-adaptin (Gaidarov and Keen, 1999) and μ2 (Rohde et al., 2002). This could provide an initial targeting of AP2 as the plasma membrane is enriched in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Once AP2 was associated with the correct membrane, clathrin binding would activate the μ2 kinase, driving μ2 phosphorylation. This would induce a conformational change in AP2, allowing μ2 to bind cargo receptors. Our model explains the long-standing observation that the proteolytic sensitivity of μ2 dramatically increases when AP2 is incorporated into clathrin cages (Matsui and Kirchhausen, 1990), and is consistent with previous experiments showing that the incorporation of AP2 into clathrin coats increases its affinity for cargo (Rapoport et al., 1997). It will be of considerable interest to investigate if clathrin also regulates μ1–cargo interactions via a similar mechanism. Recent reports have shown that overexpression of wild-type and kinase-dead AAK1 resulted in an inhibition of transferrin endocytosis. (Conner and Schmid, 2003b). A likely interpretation, consistent with our results, is that excess AAK1, independently of its kinase activity, acts in a dominant-negative fashion by binding either AP2 and/or clathrin and preventing their interaction.

In summary, our results point to a novel regulatory feature for clathrin that is independent of its structural role and that provides elegant spatial control of AP2 and cargo interactions, ensuring that AP2 is only activated at the correct cellular location and in the correct functional context.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Antibodies to the brain-specific insert of α-adaptin (aa 706–722) were prepared as described previously (Ball et al., 1995). Antibodies to the phosphorylated form of μ2 were generated by injection of the phosphopeptide CEEQSQITSQVT(P)GQIGWRRR coupled to BSA into a sheep. Antibodies were affinity purified on a column containing the phosphopeptide. mAbs to μ2 were obtained from Transduction Laboratories and were a gift from Margaret Robinson, Cambridge University, UK.

Clathrin, AP2, and μ2 kinase

Coat proteins were prepared by differential centrifugation followed by gel filtration as described previously (Campbell et al., 1984). This allowed separation of clathrin from the APs. Further preparation of AP2 from the μ2 kinase was performed on hydroxyapatite as described previously (Pauloin and Thurieau, 1993). Some batches of AP2 and kinase were prepared by Linda Adams (University of Dundee, Dundee, UK) and Sophia Semerdjieva (University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK). Clathrin heavy and light chains were separated as described previously (Winkler and Stanley, 1983).

Kinase assays

Kinase assays (20-μl final volume) contained μ2 kinase, AP2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 100 μM γ[32P]ATP (specific activity of 0.5 μCi/nmol) in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5. Incubations were performed for 10 min at 30°C, reactions were stopped by addition of 5× Laemmli sample buffer, and the samples were heated at 60°C for 5 min before electrophoresis. Gels were fixed, dried, and radioactivity was quantified using a PhosphorImager (Fuji) followed by analysis using Fuji Science lab. Peptide kinase assays were performed using the peptide (EEQSQITSQVTCQIGWRRR) as substrate. Incubations were as described above, except that ATP was used at a specific activity of 2 μCi/nmol; incubations were processed as described previously (Cross and Smythe, 1998).

Permeabilized cell assay

The permeabilized cell assays were performed as described previously (Smythe et al., 1994; McLauchlan et al., 1998) with the following modifications: assay mixes were pretreated with 1 μM microcystin at 4°C for 10 min before allowing the reaction to proceed.

Growth and preparation of DKO-R cells

Maintenance of DKO-R cells and doxycycline treatment were as described previously (Wettey et al., 2002). 5 × 106 cells were lysed in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.2 mM PMSF, and 50 mM NaF, and were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 5 min. Cytosol was prepared as described previously (Wettey et al., 2002). Clathrin was detected with mAb TD1 (Wettey et al., 2002), μ2 with an mAb from Transduction Laboratories. To separate assembled from unassembled clathrin, cells were lysed in 40 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 75 mM KCl, 4.5 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 0.01% PMSF, and 50 mM NaF, and were centrifuged at 1,000 g. After centrifugation at 100,000 g for 20 min, the supernatant (unassembled clathrin) was removed and the pellet (assembled clathrin) was resuspended in the same volume of lysis buffer as the supernatant (Cheetham et al., 1996). Both fractions were subjected to immunoblotting as above.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Osborne for generating the α-adaptin antibodies; Jane Leitch for affinity purifying the phospho-μ2 antibody; and Nick Gay and Kenji Mizugichi for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council (G117/267), the Biotechnology and Sciences Research Council (94/C15666), and the British Heart Foundation (FS/2001053) to E. Smythe. F. Wettey received support from the Marie Curie Foundation, and L. Hufton from funds provided by Cambridge University.

A.P. Jackson and A. Flett contributed equally to this paper.

References

- Ball, C.L., S.P. Hunt, and M.S. Robinson. 1995. Expression and localization of α-adaptin isoforms. J. Cell Sci. 108:2865–2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C., J. Squicciarini, M. Shia, P.F. Pilch, and R.E. Fine. 1984. Identification of a protein kinase as an intrinsic component of rat liver coated vesicles. Biochemistry. 23:4420–4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham, M.E., B.H. Anderton, and A.P. Jackson. 1996. Inhibition of hsc70-catalysed clathrin uncoating by HSJ1 proteins. Biochem. J. 319:103–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, B.M., A.J. McCoy, H.M. Kent, P.R. Evans, and D.J. Owen. 2002. Molecular architecture and functional model of the endocytic AP2 complex. Cell. 109:523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner, S.D., and S.L. Schmid. 2002. Identification of an adaptor-associated kinase, AAK1, as a regulator of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 156:921–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner, S.D., and S.L. Schmid. 2003. a. Regulated portals of entry into the cell. Nature. 422:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner, S.D., and S.L. Schmid. 2003. b. Differential requirements for AP-2 in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 162:773–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross, D.A., and C. Smythe. 1998. PD 98059 prevents establishment of the spindle assembly checkpoint and inhibits the G2-M transition in meiotic but not mitotic cell cycles in Xenopus. Exp. Cell Res. 241:12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidarov, I., and J.H. Keen. 1999. Phosphoinositide-AP-2 interactions required for targeting to plasma membrane clathrin-coated pits. J. Cell Biol. 146:755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, P., and S. Kornfeld. 2003. AP-1 binding to sorting signals and release from clathrin-coated vesicles is regulated by phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 160:699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, B.E., and R.B. Pearson. 1991. Intrasteric regulation of protein kinases and phosphatases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1094:67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhausen, T. 1999. Adaptors for clathrin-mediated traffic. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15:705–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, W., and T. Kirchhausen. 1990. Stabilization of clathrin coats by the core of the clathrin-associated protein complex AP-2. Biochemistry. 29:10791–10798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLauchlan, H., J. Newell, N. Morrice, A. Osborne, M. West, and E. Smythe. 1998. A novel role for rab5-GDI in ligand sequestration into clathrin-coated pits. Curr. Biol. 8:34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J.R., K. Prasad, W. Hao, G.J. Augustine, and E.M. Lafer. 2000. A conserved clathrin assembly motif essential for synaptic vesicle endocytosis. J. Neurosci. 20:8667–8676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, H., J. Stewart, M.C. Fournier, H. Bosshart, I. Rhee, S. Miyatake, T. Saito, A. Gallusser, T. Kirchhausen, and J.S. Bonifacino. 1995. Interaction of tyrosine-based sorting signals with clathrin-associated proteins. Science. 269:1872–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olusanya, O., P.D. Andrews, J.R. Swedlow, and E. Smythe. 2001. Phosphorylation of threonine156 of the μ2 subunit of the AP2 complex is essential for endocytosis in vitro and in vivo. Curr. Biol. 11:896–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, D.J., and P.R. Evans. 1998. A structural explanation for the recognition of tyrosine-based endocytotic signals. Science. 282:1327–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, D.J., Y. Vallis, M.E.M. Noble, J.B. Hunter, D.R. Dafforn, P.R. Evans, and H.T. McMahon. 1999. A structural explanation for the binding of multiple ligands to the α-adaptin appendage domain. Cell. 97:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauloin, A., and P. Jolles. 1984. Internal control of the coated vesicle pp50-specific kinase complex. Nature. 311:265–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauloin, A., and C. Thurieau. 1993. The 50 kda protein subunit of assembly polypeptide (ap) ap-2 adapter from clathrin-coated vesicles is phosphorylated on threonine-156 by ap-1 and a soluble ap50 kinase which copurifies with the assembly polypeptides. Biochem. J. 296:409–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perham, R.N., L.C. Packman, and S.E. Radford. 1987. 2-Oxo acid dehydrogenase multi-enzyme complexes: in the beginning and halfway there. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 54:67–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, I., M. Miyazaki, W. Boll, B. Duckworth, L.C. Cantley, S. Shoelson, and T. Kirchhausen. 1997. Regulatory interactions in the recognition of endocytic sorting signals by AP-2 complexes. EMBO J. 16:2240–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricotta, D., S.D. Conner, S.L. Schmid, K. von Figura, and S. Honing. 2002. Phosphorylation of the AP2 μ subunit by AAK1 mediates high affinity binding to membrane protein sorting signals. J. Cell Biol. 156:791–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, G., D. Wenzel, and V. Haucke. 2002. A phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate binding site within μ2-adaptin regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 158:209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih, W., A. Gallusser, and T. Kirchhausen. 1995. A clathrin-binding site in the hinge of the beta 2 chain of mammalian AP-2 complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:31083–31090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe, E., and K. Ayscough. 2003. The Ark/Prk kinase family: regulators of endocytosis and the actin cytoskeleton. EMBO Rep. 4:246–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe, E., L.L. Carter, and S.L. Schmid. 1992. Cytosol-dependent and clathrin-dependent stimulation of endocytosis in vitro by purified adapters. J. Cell Biol. 119:1163–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe, E., P.D. Smith, S.M. Jacob, J. Theobald, and S.E. Moss. 1994. Endocytosis occurs independently of annexin-VI in human a431 cells. J. Cell Biol. 124:301–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettey, F.R., S.F. Hawkins, A. Stewart, J.P. Luzio, J.C. Howard, and A.P. Jackson. 2002. Controlled elimination of clathrin heavy-chain expression in DT40 lymphocytes. Science. 297:1521–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, F.K., and K.K. Stanley. 1983. Clathrin heavy-chain, light chain interactions. EMBO J. 2:1393–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]