Abstract

BACKGROUND

Rates of blood pressure (BP) control are lower in minority populations compared to whites.

OBJECTIVE

As part of a project to decrease health-related disparities among ethnic groups, we sought to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and management practices of clinicians caring for hypertensive patients in a predominantly minority community.

DESIGN/PARTICIPANTS

We developed clinical vignettes of hypertensive patients that varied by comorbidity (type II diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, coronary artery disease, or isolated systolic hypertension alone). We randomly assigned patient characteristics, e.g., gender, age, race/ethnicity, to each vignette. We surveyed clinicians in ambulatory clinics of the 4 hospitals in East/Central Harlem, NY.

MEASUREMENTS

The analysis used national guidelines to assess the appropriateness of clinicians’ stated target BP levels. We also assessed clinicians’ attitudes about the likelihood of each patient to achieve adequate BP control, adhere to medications, and return for follow-up.

RESULTS

Clinicians’ target BPs were within 2 mm Hg of the recommendations 9% of the time for renal disease patients, 86% for diabetes, 94% for isolated systolic hypertension, and 99% for coronary disease. BP targets did not vary by patient or clinician characteristics. Clinicians rated African-American patients 8.4% (p = .004) less likely and non-English speaking Hispanic patients 8.1% (p = .051) less likely than white patients to achieve/maintain BP control.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians demonstrated adequate knowledge of recommended BP targets, except for patients with renal disease. Clinicians did not vary management by patients’ sociodemographics but thought African-American, non-English-speaking Hispanic and unemployed patients were less likely to achieve BP control than their white counterparts.

KEY WORDS: hypertension, clinician, survey, quality of care, disparities

BACKGROUND

Hypertension, a highly prevalent and modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, affects an estimated 50 million individuals in the United States.1,2 Large randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that effective blood pressure (BP) control leads to reductions in adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal outcomes.3,4 Yet, despite a multitude of safe and proven-effective therapies to control hypertension, only 58% of patients with hypertension receive treatment and only 53% of treated patients have BP <140/90 mm Hg, as recommended by national guidelines.1

African-Americans have a higher prevalence of hypertension than whites and higher rates of hypertension-related cardiovascular and stroke mortality and end-stage renal disease.1,4,5 Rates of BP control are lower in minority populations, such as non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans, compared to non-Hispanic whites, further highlighting the tremendous need for improvement in identification and treatment of this chronic disease.1,3

Many possible explanations for these low rates of hypertension control exist within the complex interface among clinicians, patients, and the health care system. Emphasis is frequently placed on patient-related issues of adherence, awareness, and understanding of the condition, barriers to care, and social factors as targets for interventions.4,6,7 Quality of care provided by clinicians also merits attention. Past research has demonstrated that many clinicians are unaware of national guidelines and may accept higher BP values than recommended.8,9 In a 1996 survey of U.S. physicians, only 60% of respondents correctly defined mild, moderate, and severe hypertension according to then current national guidelines, which were only slightly less stringent than the Joint National Committee guidelines, JNC VI.4,9,10 Additional studies based on chart reviews have demonstrated that clinicians may set treatment thresholds for BP too high. Whether this situation results from a knowledge gap, clinical inertia, assumptions about patients’ behavior, or other reasons has yet to be determined.8,11–13

Evidence suggests that patient sociodemographic characteristics, such as gender, race, and socioeconomic status, impact physicians’ perceptions and attitudes, and thereby influence their behaviors and management. Using video vignettes to simulate patients, Schulman and colleagues found that both race and gender affected the likelihood that physicians would refer patients with chest pain for cardiac catheterization,14 although the effect of race on referrals was small, and other researchers have criticized the interpretation of the study.15 To evaluate physicians’ perceptions and attitudes towards patients with respect to race and sociodemographic characteristics, van Ryn surveyed clinicians after postangiogram encounters with patients. She found that physicians considered both African-American patients and those with lower socioeconomic status less likely to be compliant with cardiac rehabilitation, less intelligent, and more likely to lack adequate social support.16 Few studies have evaluated the impact that clinician and patient characteristics may have on clinicians’ attitudes and practice patterns in caring for patients with hypertension.

As part of a project to decrease health-related disparities among ethnic groups, we sought to identify underlying clinician-related obstacles to improving BP control among minority patients in East and Central Harlem, New York City. We developed a clinician survey that used patient-centered vignettes to ascertain clinicians’ knowledge about hypertension treatment goals, attitudes, and management practices regarding inner-city, minority, and nonminority patients with chronic hypertension. We hypothesized that (1) clinicians may lack knowledge of the more stringent BP targets recommended by national guidelines for patients with comorbidities, such as diabetes and renal disease, and (2) patient factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, employment status, English fluency, and reliability may play a role in clinicians’ attitudes and treatment decisions.

METHODS

Survey Design

We designed a survey containing clinical vignettes of hypertensive patients returning to their hypothetical physicians for scheduled follow-up appointments. Each survey consisited of 4 vignettes. The comorbidities for the first 3 scenarios were (1) type II diabetes mellitus, (2) chronic renal insufficiency with 1 g of proteinuria, and (3) coronary artery disease with a history of a myocardial infarction 2 years prior. The fourth scenario described a patient with isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) alone. We selected these comorbities because the JNC VI guidelines, current at the time of our study, contained clear recommendations for target BP levels in these patients.4 In each scenario, the patient presented with a BP reading that exceeded the guidelines. See Table 1 for samples of vignettes related to the 4 scenarios.

Table 1.

Sample Vignettes

| Sample survey with each vignette |

|---|

| Patient with hypertension and diabetes |

| A 48-y-old Spanish-speaking female who needs a translator returns to you for a follow-up visit with complaints of worsening allergy symptoms. She is unemployed and has a past medical history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension. On exam her BP is 138/85 mm Hg with a HR of 80 beats per minute. Her repeat BP is unchanged and the remainder of her exam is normal. Her labs reveal a normal creatinine with no microalbuminuria. Four weeks ago her BP was 150/90 and you increased her HCTZ from 12.5 to 25 mg qD (HCTZ, max dose 50 mg qD). |

| Patient with hypertension and renal disease |

| A 50-y-old Spanish-speaking female who is bilingual returns to your office for a follow-up BP check. She is a school teacher and has been your patient for many years. She arrives 45 min late for her appointment. At her previous visit 4 weeks ago, her BP was 160/90 mm Hg on atenolol 50 mg qD (Tenormin, beta-blocker, max dose 100 mg qD), and you increased the atenolol to 75 mg qD at that time. Today she feels well and her BP is 140/85 mm Hg on 2 measurements and her HR is 50 bpm. Her physical exam is otherwise unremarkable. Labs: creatinine 2.0 mg/dl (nml range 0.5–1.3 mg/dl), potassium 3.8 MEQ/L (nml range 3.5–5 MEQ/L), and a 24 h urine protein of 1.3 g (nml <150 mg/d), similar to her previous lab results 6 mo ago. |

| Patient with hypertension and cardiovascular disease |

| An 87-y-old African American male who formerly worked as a cashier returns to you for a routine follow-up visit. He has missed his last 2 appointments and needs forms completed. He had an inferior wall MI 1 y ago, and has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. He is feeling well and has no complaints of angina, dyspnea, or edema. His BP is 170/100 mm Hg and his HR is 86 bpm. A repeat BP measurement is unchanged and the remainder of his exam is unremarkable. His current medications include amlodipine 10 mg qD (Norvasc, calcium channel blocker, max dose 10 mg qD), HCTZ 25 mg qD (max dose 50 mg qD), ASA 325 mg qD, atorvastatin 20 mg qD (Lipitor). |

| Sample vignette of a patient with isolated systolic hypertension |

| A 65-y-old white female who has been your patient for some time presents to your office for routine follow-up. She is a retired school teacher and has a past medical history of hypertension and osteoarthritis. Other than her usual joint pains, she is feeling well without complaints. On exam her BP is 150/80 mm Hg and her HR is 72 bpm. The remainder of her exam is unremarkable and her BP remains unchanged after she sits quietly for 5 min. Her current medications are lisinopril 40 mg qD (Prinivil, ACE inhibitor, max dose 80 mg qD), nifedipine 120 mg qD (Procardia XL, long-acting calcium channel blocker, max dose 120 mg qD), and acetaminophen. Her BP was 148/80 at her previous visit 3 mo ago on the same regimen. |

Italicized type represents randomly assigned components.

BP = blood pressure, HR = heart rate, nml = normal, max = maximum, MI = myocardial infarction, HCTZ = hydrochlorothiazide, ASA = aspirin, ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme

For a given vignette, the clinical characteristics of the patients were the same across all surveys; however, we assigned patient sociodemographic characteristics randomly to each vignette in each survey, such that no 2 clinicians completed exactly the same survey. For example, the first vignette in every survey described a patient with diabetes and hypertension and a BP of 135/85 mm Hg, but the sociodemographic characteristics of that patient varied from 1 survey to the next. These patient characteristics were gender, age (<65, 65–80, >80), ethnicity (white, African-American, Hispanic bilingual, Hispanic requiring a translator), employment status (unemployed, cashier, school teacher, retired cashier/school teacher), and punctuality/reliability in keeping appointments (45 minutes late for today’s appointment, missed previous 2 appointments, on time).

Each vignette was followed by questions on the clinician’s knowledge, attitudes, and practice patterns related to the hypothetical patient. The survey asked clinicians to choose from a list of treatment decisions they would make at that visit. Participants were instructed to select all that apply from the following options: make no changes, increase the current medication, decrease/discontinue the current medication, add an antihypertensive agent, and/or take other action (specify).

To assess clinicians’ attitudes regarding patient compliance and reliability, we asked clinicians to predict on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree) the likelihood that a patient with the characteristics described in the vignette would adhere to medications, return for follow-up visits, or achieve or maintain adequate BP control.

To assess the appropriateness of clinicians’ target BP levels, we used the recommendations of JNC VI: <140/90 mm Hg for ISH, <130/85 mm Hg for diabetes or coronary artery disease with target organ damage such as myocardial infarction, and <125/75 mm Hg for renal disease.4 Since the completion of our study, these guidelines have been updated in the JNC VII. The most notable change is that diabetic patients and patients with renal disease share the same target BP recommendation of <130/80 mm Hg, with a target of <140/90 mm Hg for the remainder of patients.3 After each vignette, we asked clinicians to specify the BP value at which they would consider treatment to be adequate. Because of evidence that clinicians demonstrate an end-digit preference of 0, 2, and 5 when documenting BP values, we analyzed the data for BP values within the target recommended by the JNC VI guidelines and within 2 mm Hg above the recommended target value.17 In this analysis, 140/90 mm Hg was considered an appropriate target for ISH.

To evaluate the association among reported treatment decisions, patient comorbidities, and other patient and clinician characteristics, we analyzed the medication selection by respondents for each vignette and compared these responses to the JNC VI guidelines.4 Lastly, the survey asked clinicians to report their gender, age, years in training, medical specialty, board certification, ethnicity/race, and Spanish fluency.

Study Population

From November 13, 2002, through April 10, 2003, we surveyed clinicians caring for ambulatory patients in outpatient settings affiliated with all 4 hospitals in East and Central Harlem: 2 municipal hospitals, an academic teaching hospital, and a community hospital. Each hospital is a nonprofit teaching hospital that provides care to the surrounding predominantly African-American and Hispanic communities.

The study population at each hospital included attending physicians, fellows, and nurse practitioners in the general Internal Medicine, geriatrics, cardiology, and hypertension clinics and Internal Medicine residents. We distributed surveys at weekly teaching conferences, during faculty meetings, and during precepting sessions. Survey completion was voluntary and anonymous. Participants submitted a separate card with their names at the time of survey completion to allow follow-up surveys to be given to individuals who had yet to complete the survey. We pilot tested the vignettes and survey questions among physicians not in the study to assess clarity and face validity. The Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using random effects models with a random intercept for each physician to account for the correlation among 4 observations (1 for each vignette) from each provider. Specifically, for the analysis of target BP levels, which is a continuous dependent variable, we estimated linear models with a provider-specific random intercept. For the analysis of treatment decisions, which were dichotomous dependent variables, we estimated random effects logit models. Key independent variables included dummy variables for each vignette: patient sociodemographics (age, race/ethnicity, gender, and employment status), characteristics of the encounter (whether the patient was late for the appointment and whether the patient spoke Spanish and/or needed a translator), and provider characteristics (e.g., race, gender, specialty, and whether the provider was a resident).

RESULTS

Of the 469 clinicians at the participating sites, 343 (73%) completed surveys. As shown in Table 2, the respondents were predominantly Internists and medical residents.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Clinician Respondents (n = 343)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 159 | 48.3 |

| Resident | 151 | 45.2 |

| Specialty | ||

| Internists | 123 | 36.8 |

| Cardiologists | 18 | 5.4 |

| Geriatricians | 27 | 8.1 |

| Other | 15 | 4.5 |

| Board certified | 103 | 30.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 157 | 47.0 |

| African-American/black | 42 | 12.6 |

| Hispanic | 21 | 6.3 |

| Asian | 92 | 27.5 |

| Other | 22 | 6.6 |

| Age, years, mean (s.d.) | 35.6 (8.8) | |

| Patient care time in clinic/office, percent, mean (s.d) | 24.1 (23.0) | |

s.d. = standard deviation

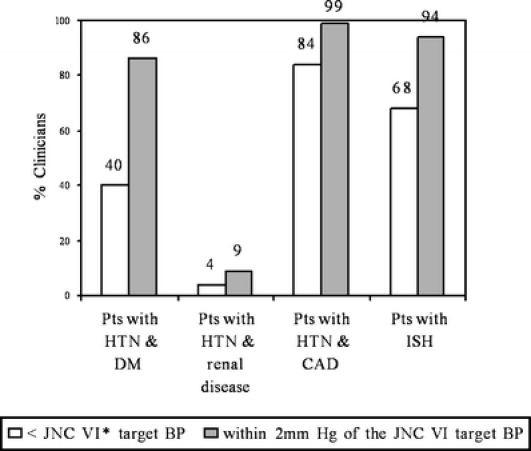

Clinicians’ accuracy in identifying adequate BP targets based on the JNC VI guidelines varied by the associated patient comorbidity. The majority of clinicians correctly identified the target BP for patients with coronary artery disease, but few were aware of the more stringent recommendations for patients with renal disease (Fig. 1). The current JNC VII guidelines for patients with renal disease are less stringent, with a target BP of <130/80 versus 125/75 mm Hg.3 Including responses within 2 mm Hg of the guidelines, to account for clinicians’ end-digit preferences of 0 and 5, the percentage of correct responses by clinicians improved markedly for all patients except those with renal disease.

Figure 1.

Clinicians’ knowledge of blood pressure targets by vignette. Pts, patients; HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; CAD, coronary artery disease; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; BP, blood pressure. Asterisk: The target BP values used in the study, from the outdated JNC VI BP targets, are: <130/85 mm Hg for DM and CAD with end organ damage; <125/75 mm Hg for renal disease with 1 g of proteinuria/day; <140/90 mm Hg for ISH. The current JNC VII guidelines recommend: <130/80 mm Hg for DM or chronic kidney disease; <140/90 mm Hg for all others

Patient characteristics including gender, age, race/ethnicity, Spanish speaking, employment status, and reliable follow-up did not influence clinicians’ BP targets (Table 4). However, the clinician characteristics of medical specialty and years in training were correlated with knowledge of JNC VI BP targets. Geriatricians were less likely than Internists and residents were less likely than other clinicians to choose guidelines-based BP targets. This translated into a small difference in target BPs (3.5 mm Hg systolic, 95% CI 1.0–6.0) between geriatricians and Internists (data not shown). There were no differences in target BP by clinician gender, age, board certification, race/ethnicity, or Spanish fluency.

Table 4.

Selected Coefficients (other variables include site indicators and indicators for vignette) from Logistic Regressions Relating Patient and Clinician Characteristics with Clinicians’ Correct Identification of Target Blood Pressure, and Attitudes Regarding Patient Likelihood of Returning for Follow-up

| JNC VI target blood pressure correct* | Patient not likely to control BP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | p value | Marginal effect (%) | Odds ratio | p value | Marginal effect (%) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age/5† | 1.02 | 0.55 | 0 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 1 |

| Female | 1.08 | 0.64 | 2 | 1.12 | 0.47 | 2 |

| Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white ref) | ||||||

| African American | 0.90 | 0.60 | −2 | 1.76 | <0.01 | 8 |

| Hispanic bilingual | 1.37 | 0.16 | 7 | 0.93 | 0.75 | −1 |

| Hispanic—needs interpreter | 0.88 | 0.63 | −3 | 1.67 | 0.05 | 8 |

| Employment status (teacher ref) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 1.37 | 0.20 | 7 | 1.99 | <0.01 | 10 |

| Cashier | 0.98 | 0.90 | −1 | 1.22 | 0.31 | 3 |

| Late for appointment | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0 | 6.47 | <0.01 | 26 |

| Clinician characteristics | ||||||

| Female | 1.20 | 0.41 | 4 | 0.87 | 0.46 | −2 |

| Resident | 0.46 | 0.02 | −17 | 0.84 | 0.55 | −2 |

| Specialty (medicine ref) | ||||||

| Cardiology | 0.96 | 0.93 | −1 | 1.44 | 0.44 | 6 |

| Geriatrics | 0.15 | <0.01 | −28 | 0.89 | 0.77 | −1 |

| Other or none | 0.79 | 0.58 | −5 | 1.64 | 0.17 | 8 |

| Board certified | 0.83 | 0.57 | −4 | 0.85 | 0.55 | −2 |

| Race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white ref) | ||||||

| African American | 0.91 | 0.81 | −2 | 0.58 | 0.13 | −6 |

| Hispanic | 1.59 | 0.31 | 11 | 0.80 | 0.57 | −3 |

| Asian | 1.22 | 0.51 | 4 | 0.64 | 0.08 | −6 |

| Other | 0.82 | 0.71 | −4 | 0.57 | 0.22 | −7 |

| Patient care time in clinic/office (<10% ref) | ||||||

| 10–19% | 0.81 | 0.54 | −5 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0 |

| 20–29% | 0.62 | 0.19 | −10 | 0.82 | 0.52 | −3 |

| ≥30% | 0.66 | 0.25 | −9 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0 |

| Age (<30 reference) | ||||||

| 30–39 | 1.49 | 0.15 | 9 | 0.64 | 0.05 | −6 |

| ≥40 | 1.21 | 0.63 | 4 | 0.35 | <0.01 | −11 |

| Missing/refused | 3.32 | 0.01 | 29 | 0.44 | 0.05 | −9 |

Data not shown for patient categories were not likely to adhere to therapy and not likely to return, as values did not reach statistical significance except for the following: Not likely to adhere to therapy: late patients, odds ratio 6.04, p value <.01; unemployed patients, odds ratio1.65, p value .04. Not likely to return: late patients, odds ratio 14.13, p value <.01. Marginal effect: the change in the probability of the outcome compared to the reference group

*Target blood pressures are based on the JNC VI guidelines, which were current at the time of the study

†Patient age divided by 5. Odds ratio and marginal effect reflect change associated with a 5-year increase in age

BP = blood pressure, ref = reference group

Regarding clinicians’ treatment practices, nearly one quarter of clinicians opted to make no change in the treatment regimen for the vignette with the diabetic patient, despite a BP value of 138/85 mm Hg, which exceeded the JNC VI target (<130/85 mm Hg). Across all the vignettes, the majority of clinicians, however, did choose to change patient management by either increasing the current medication and/or by adding a new agent to the regimen. Over 70% of clinicians added a new agent for patients with renal or coronary artery disease and over 50% for patients with ISH (Table 3). Clinicians’ decisions to change treatments did not correlate with any clinician characteristics or patient characteristics across the 4 vignettes (data not shown).

Table 3.

Frequency of Clinicians’ Management Decisions Regarding Medications by Vignette

| Clinician responses (n = 334 total responses) | Vignette 1: HTN and diabetes mellitus | Vignette 2: HTN and renal disease | Vignette 3: HTN and coronary artery disease | Vignette 4: isolated systolic HTN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No changes in medications | n = 78 | n = 30 | n = 16 | n = 46 |

| 23.4% (19.8%, 28.8%) | 9.0% (6.2%, 12.6%) | 4.8% (2.8%, 7.7%) | 13.8% (10.3%, 17.9%) | |

| Increase dose of a current medication | n = 16 | n = 9 | n = 20 | n = 106 |

| 4.8% (3%, 8%) | 2.7% (1.2%, 5.1%) | 6.0% (3.7%, 9.1%) | 31.7% (26.8%, 37.0%) | |

| Discontinue a medication | n = 12 | n = 56 | n = 59 | n = 16 |

| 3.6% (2%, 6%) | 16.8% (13.0%, 21.3%) | 17.7% (13.7%, 22.2%) | 4.8% (2.8%, 7.7%) | |

| Add a new medication | n = 241 | n = 287 | n = 249 | n = 172 |

| 72.2% (67%, 77%) | 86.2% (82.0%, 89.7%) | 74.6% (69.5%, 79.1%) | 51.5% (46.0%, 57.0%) |

Percentages sum to greater than 100% because multiple treatment decisions were possible. Figures in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals

HTN = hypertension

Patient characteristics were associated with clinicians’ expectations that patients would succeed in adhering to medications, returning for follow-up visits, and achieving/maintaining BP control (Table 4). Specifically, clinicians rated patients who were late or absent for appointments as less likely to succeed in all 3 categories. Clinicians gave patients who were unemployed a lower probability of achieving BP control than patients who were school teachers, and rated African-American patients and Hispanic patients who needed a translator less likely than white patients to achieve/maintain BP control. Compared to clinicians under the age of 30, clinicians aged 40 years old or older were more skeptical of the likelihood of adherence and ultimate control of BP of all patients (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The majority of clinicians we surveyed, who represent the front line of hypertension management in East and Central Harlem, had a high degree of knowledge of BP targets for patients with diabetes, coronary artery disease, and ISH. Their knowledge about the target for patients with renal disease, however, fell far short of the JNC VI guidelines. Residents and geriatricians were least likely to correctly identify target BPs. Although clinicians did not appear to base their management decisions or target BPs on patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, they thought African-American, non-English-speaking Hispanic, and unemployed patients were less likely to achieve BP control than their white counterparts.

The poor knowledge of BP targets in renal patients may reflect a lack of guideline awareness by clinicians or confusion stemming from the multiple comorbidity-related target values in the JNC VI guidelines. The current JNC VII guidelines, published in May 2003, have been simplified, and combine patients with diabetes or renal disease into 1 category with a target BP of <130/80 mm Hg.3 This simplification may help improve awareness and control rates.

Clinician characteristics of training and specialty were associated with small differences in BP targets, as residents and geriatricians were less likely to correctly identify target BP values compared to Internists and cardiologists. Geriatricians may be more sensitive to possible adverse events from hypotension, including falls, bradycardia, dizziness, and orthostatic hypotension, when treating elderly patients. This difference, however, persisted for all patients regardless of age groups. Geriatricians, therefore, represent an important group to target for further interventions to improve hypertension management.

With respect to patient characteristics, we found that clinicians’ did not vary their BP targets or treatment plans based on patient race/ethnicity, gender, employment status, or any other patient characteristics examined. Clinicians set BP goals and made management decisions irrespective of patients’ sociodemographics. Discovering whether this situation applies to clinicians who have chosen to practice in other inner-city minority areas and in more affluent areas with less diverse populations would be valuable.

Clinicians’ attitudes towards patients, however, did differ according to the hypothetical patients’ reliability, employment status, and race/ethnicity. Clinicians considered patients who were African-American, non-English-speaking Hispanic, unemployed, or late/absent for appointments to be less likely to achieve adequate BP control. Late or unemployed patients were also considered less likely to adhere to medications, and late patients less likely to follow-up as well. Perhaps clinicians’ regarded missed appointments or tardiness as markers for poor adherence and therefore deemed these patients less likely to achieve adequate BP control. Likewise, clinicians may have considered the burden of financial and social stressors shouldered by unemployed patients as barriers to adherence.

These arguments fail to explain the differences in clinician attitudes found for African-American patients and non-English-speaking Hispanic patients who were considered less likely to achieve BP control yet equally likely to adhere. Perhaps clinicians are uncertain of the exact cause of the poor control, yet are basing the response on stereotypes, previous experience, or knowledge that African-Americans have more severe hypertension. Our results are similar to van Ryn’s findings in physician surveys following angiogram encounters that race and socioeconomic status influence physicians’ perceptions of patient adherence. Van Ryn’s results suggest that some clinicians practicing in these communities harbor stereotypes.16 These stereotypes may interfere with clinician–patient communications. Clinicians’ may provide less information to patients regarded as being less likely to achieve BP control. Or clinicians may be less aggressive in implementing treatment, although we did not find this pattern in our survey. Alternatively, these findings may reflect clinicians’ actual experience in treating African-American patients. As mentioned previously, African-American patients often have increased severity of hypertension when compared to whites. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment To Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) found a reduced response to monotherapy with beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors compared to diuretics and calcium channel blockers in African-American patients.18

The fact that clinicians’ self-reported practice patterns for hypertensive patients did not vary by patient characteristics may reflect the social desireablility phenomenon, in which clinicians’ report what is expected of them in the survey, yet choose different actions, consciously or unconsciously, in actual practice.

Clinicians’ management practices varied by vignette. Nearly 1 in 4 clinicians opted not to change the treatment of the diabetic patient, a much higher frequency compared to the other vignettes. This may relate to the fact that the diabetic patient’s BP was only mildly elevated resulting in less aggressive management or, possibly, clinical inertia.

Our study design had several strengths. We collected surveys from all 4 hospitals in East and Central Harlem and achieved a high response rate from a wide range of clinicians in the area. Furthermore, we randomly assigned characteristics of the hypothetical patients among the versions of the survey that clinicians received.

Our study also had limitations. We used clinical vignettes of hypertensive patients to assess clinicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice patterns. These written vignettes lacked visual cues that occur in a medical encounter and rely on clinician self-report rather than actual practice. Several reports, however, support the use of case simulations to assess respondents’ attitudes, knowledge, and decision-making.19,20,21 Previous reports have also demonstrated high correlations between written simulations and actual practice.22,23 To recruit clinicians providing care to the inner-city community, we included only clinicians practicing within hospital-affiliated clinics, the major providers in this area. However, this may not represent all clinicians in the region.

The influence of patients’ sociodemographics on clinicians’ attitudes about the likelihood of patients’ achieving BP control as reported in this survey offers opportunities for quality-improvement programs and future research. Deficiencies in patients’ abilities to better manage this chronic condition or in clinicians’ skills in pharmaceutical and other management may underlie these findings. Improvement in clinicians’ knowledge of BP targets for renal disease and therapy for diabetic and renal disease patients holds substantial promise of better quality of care and patients’ outcomes. The impact on African-Americans, who have higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, and renal disease, and Hispanics, who have higher rates of poorly controlled hypertension, could be substantial.24

Acknowledgements

This work was presented in abstract form at The Society of General Internal Medicine 26th Annual Meeting, April 30 to May 3, 2003, in Vancouver, British Columbia, and at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, June 27–29, 2003, in Nashville, TN.

Funding Source Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, P01 HS10859; National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health, P60 MD00270-01; and The Commonwealth Fund, 20030088.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Footnotes

This research project has not been published in any other peer-reviewed media and is not under review elsewhere. This study was conducted at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York. All of the authors listed on the manuscript have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors.

References

- 1.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25:305–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Chobian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VII). JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.JNC 6. National High Blood Pressure Education Program. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Randall BL, Neaton JD, Brancati FL, Stamler J. End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men. 16-year MRFIT findings. JAMA. 1997;277:1293–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Stockwell DH, Madhavan S, Cohen H, Gibson G, Alderman MH. The determinants of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in an insured population. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1768–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ahluwalia JS, McNagny SE, Rask KJ. Correlates of controlled hypertension in indigent, inner-city hypertensive patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN. Self-reported hypertension treatment practices among primary care physicians: blood pressure thresholds, drug choices, and the role of guidelines and evidence-based medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2281–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN, Vallbona C. Physician role in lack of awareness and control of hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2000;2:324–30. [PubMed]

- 10.Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The fifth report of the Joint National Committee on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC V). Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:154–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC, et al. Inadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive population. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1957–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Oliveria SA, Lapuerta P, McCarthy BD, L’Italien GJ, Berlowitz DR, Asch SM. Physician-related barriers to the effective management of uncontrolled hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:413–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002;40(Suppl 1):I-140–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:618–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Welch HG. Misunderstandings about the effects of race and sex on physicians’ referrals for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:279–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Green BB, Kaplan RC, Psaty BM. How do minor changes in the definition of blood pressure control affect the reported success of hypertension treatment? Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:219–24. [PubMed]

- 18.The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker or diuretic. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Swanson DB, Barrow HS, Friedman CP. Issues in assessment of clinical competence. Prof Educ Res. 1982;4:2.

- 20.Moskowitz AJ, Kuipers B, Kassirer JP. Dealing with uncetainty, risks, and trade offs in clinical decisions: a cognitive science approach. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:435–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Jones TV, Gerrity MS, Earp J. Written case simulations: do they predict physicians’ behavior? J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:805–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kirwan JR, Chaput de Saintonge DM, Joyce CRB, Currey HLF. Clinical judgement in rheumatoid arthritis. I. Rheumatologists’ opinions and the development of “paper patients.” Ann Rheum Dis. 1983;42:644–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kirwan JR, Bellamy N, Condon H, Buchanan WW, Barnes CG. Judging “current disease activity” in rheumatoid arthritis—an international comparison. J Rheumatol 1983;10:901–5. [PubMed]

- 24.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/estimates.htm, accessed September 2, 2005.