Abstract

Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1), and interleukin 6 (IL-6) comprise a group of structurally related cytokines that promote the survival of subsets of neurons in the developing peripheral nervous system, but the signaling pathways activated by these cytokines that prevent neuronal apoptosis are unclear. Here, we show that these cytokines activate NF-κB in cytokine-dependent developing sensory neurons. Preventing NF-κB activation with a super-repressor IκB-α protein markedly reduces the number of neurons that survive in the presence of cytokines, but has no effect on the survival response of the same neurons to brain-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF), an unrelated neurotrophic factor that binds to a different class of receptors. Cytokine-dependent sensory neurons cultured from embryos that lack p65, a transcriptionally active subunit of NF-κB, have a markedly impaired ability to survive in response to cytokines, but respond normally to BDNF. There is increased apoptosis of cytokine- dependent neurons in p65 −/− embryos in vivo, resulting in a reduction in the total number of these neurons compared with their numbers in wild-type embryos. These results demonstrate that NF-κB plays a key role in mediating the survival response of developing neurons to cytokines.

Keywords: leukemia inhibitory factor, ciliary neurotrophic factor, cardiotrophin-1, apoptosis, neuron

Introduction

Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) is a ubiquitously expressed transcription factor that consists of homodimers or heterodimers of a family of structurally related proteins ( Baldwin 1996; Ghosh et al. 1998). In most cell types, it is present as a heterodimer comprising p65 (RelA) and p50 subunits, which is held in an inactive form in the cytosol by interaction with a member of the IκB family of inhibitory proteins ( Verma and Stevenson 1997; Karin 1998). NF-κB is activated by the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB, which results in translocation of the liberated NF-κB to the nucleus where it induces transcription of target genes. A wide variety of noxious stimuli, such as viral and bacterial infection, UV light, ionizing radiation, and free radicals, as well as a variety of lymphokines and cytokines, activate NF-κB which in turn positively regulates the expression of genes that mediate an acute inflammatory response ( Baldwin 1996; Baeuerle and Baichwal 1997). In addition, NF-κB activation suppresses apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and various genotoxic agents in lymphoid and fibroblast cell lines ( Beg and Baltimore 1996; Van Antwerp et al. 1996; Wang et al. 1996) and protects hippocampal neurons against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis ( Mattson et al. 1997). These data and the finding that there is massive hepatocyte death in p65 −/− mouse embryos ( Beg et al. 1995) indicate that NF-κB also plays a role in regulating cell survival.

In the nervous system, NF-κB is not only involved in mediating inflammatory responses ( O'Neill and Kaltschmidt 1997), but is induced by several molecules that play key roles in neural function and development. For example, NF-κB is induced by glutamate in cerebellar granule cells ( Guerrini et al. 1995; Kaltschmidt et al. 1995), by nerve growth factor (NGF) in Schwann cells ( Carter et al. 1996), and NGF-dependent sympathetic and sensory neurons ( Maggirwar et al. 1998; Hamanoue et al. 1999). In the case of Schwann cells and sensory neurons, it has been shown that NGF activates NF-κB by binding to the p75 neurotrophin receptor ( Carter et al. 1996; Hamanoue et al. 1999). Although p75 is not essential for the survival response of neurons to NGF, binding of NGF to this receptor in neurons coexpressing the NGF receptor tyrosine kinase, TrkA, significantly enhances the number of neurons that survive ( Davies et al. 1993; Lee et al. 1994; Horton et al. 1997; Ryden et al. 1997). Preventing NF-κB activation in NGF-treated sensory neurons causes a modest reduction in survival, suggesting that the p75-mediated enhancement of the NGF survival response is at least partly due to NF-κB activation ( Hamanoue et al. 1999). Likewise, preventing NF-κB activation in NGF-treated sympathetic neurons reduces the survival of these neurons ( Maggirwar et al. 1998).

In addition to the neurotrophins (NGF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF], neurotrophin 3 [NT-3], and NT-4), several other families of neurotrophic factors play key roles in promoting and regulating neuronal survival. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) comprise a family of cytokines that have multiple actions on cells of the nervous system and promote the survival of various kinds of neurons during development ( Sendtner et al. 1994; Stahl and Yancopoulos 1994). Although there is <15% amino acid sequence identity between these factors, they share several characteristic structural features ( Bazan 1991; Robinson et al. 1994; McDonald et al. 1995) and signal via oligomeric receptor complexes that have one or more components in common ( Davis et al. 1993; Stahl et al. 1994; Wollert et al. 1996). The transmembrane glycoproteins gp130 and LIFRβ are common components of the receptor complexes for CNTF, LIF, oncostatin M (OSM), and CT-1. The CNTF receptor complex has an additional GPI-linked CNTFRα subunit, and the IL-6 receptor consists of two gp130 subunits and an IL-6Rα subunit. Binding of these cytokines to their receptor complexes results in the direct or indirect activation of several signaling pathways including the JAK-Stat, PI-3 kinase, Ras/MAP kinase, and PLC-γ pathways ( Boulton et al. 1994; Stahl et al. 1994; Frank and Greenberg 1996).

To further investigate the role of NF-κB in regulating neuronal survival, we measured and experimentally manipulated NF-κB activation in populations of sensory neurons that survive in response to cytokines. Neurons from the trigeminal and nodose ganglia of embryonic day 18 (E18) mouse embryos were used for these studies because their large size facilitates microinjection of constructs used for measuring and manipulating NF-κB activation. These neurons are supported by neurotrophic cytokines in culture and die by apoptosis after neurotrophic factor deprivation ( Horton et al. 1998). We show that NF-κB activation plays a major role in mediating the survival response of these neurons to neurotrophic cytokines.

Materials and Methods

Neuron Culture, Microinjection, and Survival Assays

For microinjection studies, dissociated cultures of trigeminal and nodose ganglion neurons were established from E18 CD1 embryos. The dissected ganglia were trypsinized and dissociated by trituration, and the neurons were purified free of nonneuronal cells by differential sedimentation ( Davies 1986). The neurons (>95% pure) were grown in defined, serum-free medium on a poly-ornithine/laminin substratum in 60-mm diam tissue culture petri dishes ( Davies et al. 1993). After an initial 12–24-h incubation period with a neurotrophic factor that promotes survival, the neurons were washed extensively to remove this factor and were injected intranuclearly ( Allsopp et al. 1993) with pcDNAIII expression plasmids. The pcDNAIII plasmid without a cDNA insert was used to control for nonspecific effects of the injection procedure, and pcDNAIII plasmids containing cDNAs encoding the human p65 NF-κB subunit or a mutated IκB-α that is defective in signal-induced degradation ( Rodriguez et al. 1996) were used to investigate the role of NF-κB activation in promoting neuronal survival. The expression plasmids were diluted in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7, to a concentration of 100 μg/ml and filtered through a 0.22-μm filter before injection. Some cultures were resupplemented with neurotrophic factor 30 min after injection. The number of surviving neurons was counted at 24 hourly intervals after injection and is expressed as a percentage of the number injected. About 150 neurons were injected for each experimental condition.

For studies of the endogenous p65 on neuronal survival, cultures were established from mice that have a null mutation in the p65 gene (a gift of Amer Beg and David Baltimore (Beg et al., 1995). Heterozygous mice were crossed to obtain p65 −/−, p65 +/− and p65 +/+ embryos. After 12- or 14-d gestation, the pregnant females were killed and nodose ganglia were dissected from each embryo separately. After genotyping the embryos by a PCR based method, the ganglia of each genotype were pooled and low-density, dissociated cultures were established. The neurons were grown in defined medium in laminin/poly-ornithine coated petri dishes with a range of concentrations of CNTF, LIF, CT-1, IL-6, or BDNF as described above. The number of neurons surviving after 48-h incubation is expressed as a percentage of the number of attached neurons counted 6 h after plating.

Measurement of NF-κB Activation

E18 trigeminal neurons were grown for 24 h with 2 ng/ml NGF, washed thoroughly to remove the NGF, and incubated in F14 medium for a further 2 h before being injected with two DNA constructs: an NF-κB–dependent luciferase reporter gene that consists of three synthetic copies of the NF-κB–consensus sequence from the Ig-κ chain promoter upstream of the luciferase gene ( Rodriguez et al. 1996) and a lacZ gene that is driven by an RSV promoter. In some experiments, neurons were also coinjected with the mutated IκB-α expression plasmid. Injected neurons were harvested using a rubber policeman 6 h later. Several hundred neurons were injected for each assay. The cultures were treated with 50 ng/ml CNTF 30 min after injection; untreated cultures served as controls. Luciferase activity was measured by using a luminometer as described previously ( Rodriguez et al. 1996) and β-galactosidase activity was measured by using the Galactolight kit (Tropix) as recommended by the manufacturer. The relative level of NF-κB activation in each experiment was calculated by dividing the luciferase activity by β-galactosidase activity.

Quantification of the Number of Neurons in the Nodose Ganglia

E14 mouse embryos in litters resulting from overnight matings of p65 +/− mice were fixed in Carnoy's fluid (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, 10% acetic acid) for 20 min before dehydration and wax-embedding. Serial sections of the heads were cut at 8 μm, mounted on poly lysine-coated slides, and cleared in xylene and dehydrated before quenching (10% methanol, 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS). To identify all neurons in these preparations, the sections were stained for neurofilament protein as described previously ( Middleton et al. 1998). In addition, the sections were counterstained with cresyl fast violet to permit identification of pyknotic nuclei. Estimation of neuronal number was carried out as described previously ( Piñón et al. 1996) using the Abercrombie method to correct for split nuclei ( Abercrombie 1946). Pyknotic nuclei were recognized as one or more darkly stained spherical structures contained within a clearly visible membrane ( Piñón et al. 1996).

Immunocytochemical Detection of Cytokine Receptors on Nodose Neurons

To ascertain if the p65 null mutation affects the expression of cytokine receptors on nodose neurons, immunocytochemistry was used to assess the proportion of neurons that express cytokine receptor components in cultures established from the nodose ganglia of E12 and E14 wild-type p65 +/− and p65 −/− embryos. Dissociated cultures of nodose neurons were cultured with a cocktail of neurotrophic factors (50 ng/ml CNTF, 50 ng/ml LIF, 50 ng/ml CT-1, and 10 ng/ml BDNF) to sustain the survival of the maximum number of neurons. 6 h after plating, the cultures were fixed for 15 min in neutral buffered formalin. After washing with PBS, endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 1% hydrogen peroxidase in methanol. After 20 min incubation in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 10% serum (rabbit serum for goat primary antibody and goat serum for rabbit primary antibody), the cultures were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in 1:300 dilution of one of the following antibodies: rabbit anti-gp130, rabbit anti-LIFRβ, goat anti-CNTFRα, and rabbit anti-IL-6Rα (all from Santa Cruz). After washing with PBS, bound primary antibodies were labeled using biotinylated secondary antibody (1:200), avidin, and biotinylated HRP macromolecular complex (Vectastain ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories). The substrate used for the peroxidase reaction was 1 mg/ml diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (Sigma Chemical Co.). The number of labeled neurons was assessed by bright-field illumination on an inverted microscope.

Results

CNTF Activates NF-κB

To ascertain whether neurotrophic cytokines activate NF-κB in neurons, we microinjected neurotrophic factor-deprived neurons with an NF-κB–dependent luciferase reporter construct ( Rodriguez et al. 1996) and assayed luciferase activity after cytokine treatment. Because relatively large numbers of neurons have to be injected to produce a clearly quantifiable signal, we used trigeminal neurons for these studies because the trigeminal ganglia are by far the largest ganglia in the peripheral nervous system of the mouse embryo. These studies were carried out at E18 because trigeminal neurons display a clear survival response to CNTF at this stage ( Horton et al. 1998) and have grown to a sufficiently large size to facilitate microinjection. To standardize luciferase activity measurements between experiments, we coinjected a lacZ gene driven by a constitutive RSV promoter and additionally assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Separate experiments showed that β-galactosidase activity was unaffected by CNTF (data not shown). Fig. 1 shows that five hours after CNTF treatment, the relative luciferase activity was fourfold higher than in untreated control cultures, indicating that CNTF activates NF-κB in these neurons. The activity of a control luciferase reporter lacking NF-κB binding sites was unchanged by treatment with CNTF (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Bar chart of relative NF-κB activation (luciferase activity divided by β-galactosidase activity) in E18 trigeminal neurons under different experimental conditions. The neurons were initially cultured with NGF for 24 h, washed, and incubated in NGF-free medium for 2 h, then coinjected with the NF-κB–dependent luciferase reporter construct and the RSV lacZ expression plasmid (plus the super-repressor IκB-α expression plasmid in the cultures indicated), and maintained for a further 6 h before assaying for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. CNTF (50 ng/ml) was added to the cultures indicated immediately after injection. Relative NF-κB activity at each point is calculated from the ratio of luciferase to lacZ activity compared with the untreated control. The mean and SEM are shown for three separate experiments.

To determine if the rise in luciferase activity after CNTF treatment was a direct consequence of NF-κB–dependent transcription, the NF-κB–dependent luciferase reporter was coinjected with a plasmid that expresses a super-repressor form of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκB-α. This IκB-α protein associates normally with NF-κB, but carries serine-to-alanine mutations at residues 32 and 36 that prevents signal modification and proteosome-mediated degradation, thereby preventing release and translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus ( Rodriguez et al. 1996; Roff et al. 1996). This super-repressor IκB-α completely abolished the rise in luciferase activity after treatment with CNTF ( Fig. 1), indicating that this rise was due to NF-κB–dependent transcription.

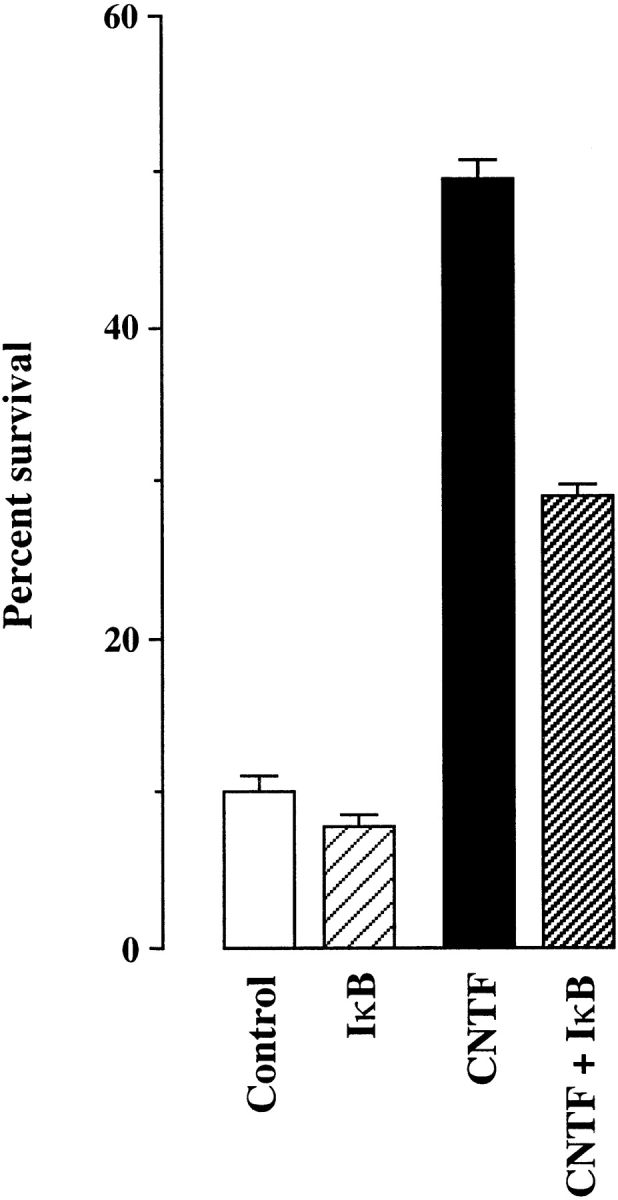

NF-κB Activation Plays a Role in Mediating the Cytokine Survival Response

Having ascertained that CNTF activates NF-κB, we investigated whether preventing NF-κB activation would interfere with the CNTF survival responses. Injection of the super-repressor IκB-α expression plasmid into E18 trigeminal neurons caused a highly significant reduction in the number of neurons surviving with CNTF, compared with neurons injected with an empty expression plasmid (P < 0.0001, t test; Fig. 2). These results suggest that the survival response of trigeminal neurons to CNTF is mediated to a large extent by the activation of NF-κB.

Figure 2.

Bar chart of the number of E18 trigeminal ganglion neurons surviving 24 h after injection with either and empty pcDNAIII plasmid (control and CNTF) or the super-repressor IκB-α plasmid (IκB and CNTF + IκB) expressed as a percentage of the number of injected neurons. The mean and SEM are shown for three separate experiments.

Because nodose ganglion neurons are more responsive to cytokines than trigeminal neurons ( Horton et al. 1998), we extended our analysis of the antiapoptotic function of NF-κB to this population of sensory neurons. Fig. 3 shows that injection of E18 nodose neurons with the super-repressor IκB-α expression plasmid markedly reduced the number of neurons surviving with CNTF, CT-1, and LIF, compared with neurons injected with an empty expression plasmid (P < 0.0001 in all cases, t tests). The percentage reduction in survival ranged from 45% with LIF to 62% with CNTF. In contrast, injection of nodose neurons with the super-repressor IκB-α expression plasmid had no effect on the survival response of these neurons to BDNF ( Fig. 3). This not only clearly indicates that expression of super-repressor IκB-α does not exert a nonspecific detrimental effect on neuronal survival, but shows that NF-κB activation plays a highly selective role in mediating neurotrophic factor responses.

Figure 3.

Bar chart of the number of E18 nodose ganglion neurons surviving 24 and 48 h after injection with either an empty pcDNAIII plasmid (vector) or the super-repressor IκB-α plasmid (IκB) expressed as a percentage of the number of injected neurons. The data from neurons grown separately with 50 ng/ml CNTF, 50 ng/ml CT-1, 50 ng/ml LIF, and 10 ng/ml BDNF are shown. The means and SEM of the results of five to ten separate experiments for each factor are shown.

To confirm that NF-κB activation independent of cytokine treatment could sustain the survival of neurotrophic factor-deprived nodose neurons, we microinjected a plasmid expressing the transcriptionally active p65 subunit of NF-κB into neurotrophic factor-deprived nodose neurons. In these experiments, cultures of purified nodose neurons were first incubated for 24 h in LIF-supplemented medium. The neurons were then deprived of LIF by extensive washing and injected with the p65 expression plasmid or an empty plasmid to control for the injection procedure. Counts of surviving neurons made at 24 hourly intervals after injection revealed that virtually all neurotrophic factor-deprived neurons injected with the empty expression plasmid had died after 72 h, whereas a large proportion of p65 overexpressing neurons survived at all time points ( Fig. 4). Coinjection of the super-repressor IκB-α plasmid with the p65 plasmid completely prevented the antiapoptotic function of overexpressed p65 (data not shown), indicating that exogenous p65 prevented apoptosis as a direct consequence of NF-κB activation. Neurons that were resupplemented with LIF or CNTF survived better than neurotrophic factor-deprived neurons overexpressing p65 ( Fig. 4), suggesting that NF-κB activation may not be sufficient to account for the full survival-promoting effects of these cytokines, as suggested in the data shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3.

Figure 4.

Graph of the number of E18 nodose ganglion neurons surviving at 24 hourly intervals after LIF deprivation and injection with either an empty pcDNAIII plasmid (vector) or the p65 plasmid (p65) expressed as a percentage of the number of injected neurons or resupplemented with LIF or CNTF. The means and SEM are shown for three separate experiments.

p65-deficient Sensory Neurons Are Less Responsive to Cytokines

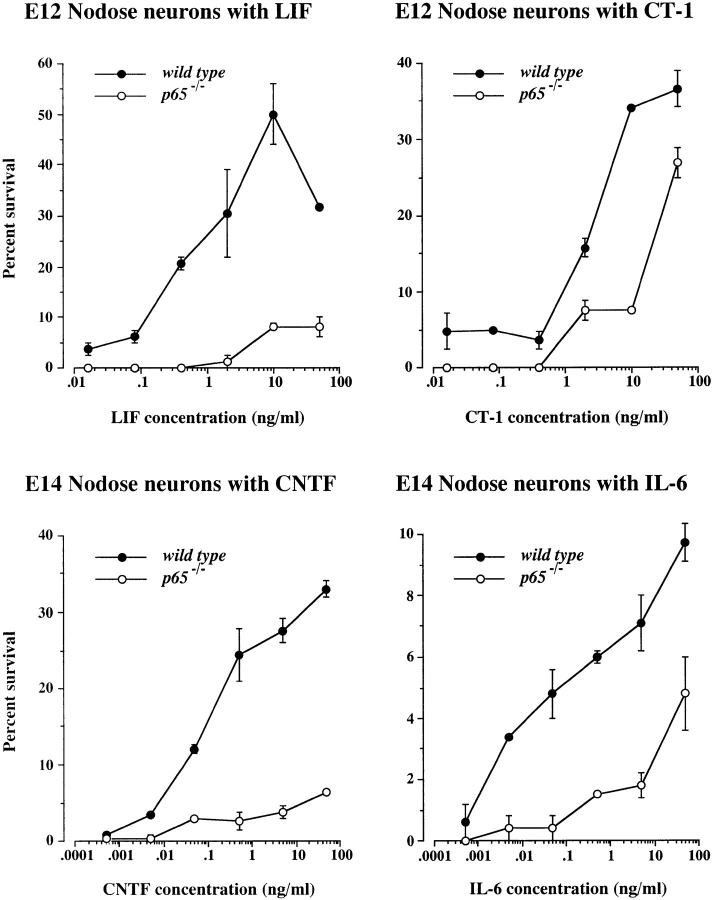

To further investigate the role of NF-κB activation in mediating the response of neurons to cytokines, we compared the dose responses of nodose neurons obtained from wild-type embryos and embryos that are homozygous for a null mutation in the p65 gene ( Beg et al. 1995). The latest stage at which these experiments could be carried out was E14 because p65 −/− embryos die in utero shortly after this stage. Although nodose neurons are maximally responsive to neurotrophic cytokines at late fetal stages, a substantial proportion of these neurons survive in response to cytokines at stages up to E14 ( Horton et al. 1998). For these experiments, adult p65 +/− mice were crossed and pregnant females were killed after 12- or 14-d gestation and the nodose ganglia dissected out from the embryos. Because of the small size of the nodose ganglia, a rapid genotyping procedure was used so that the ganglia from either wild-type or p65 −/− embryos could be pooled to obtain sufficient neurons for at least one dose response in each experiment. Fig. 5 shows that p65-deficient nodose neurons displayed a substantially reduced survival response to LIF, CNTF, CT-1, and IL-6 compared with wild-type embryos from the same litters. Although only either E12 or E14 data are illustrated for each cytokine, in several experiments carried out at both ages, the survival of p65-deficient neurons to each cytokine was markedly lower than wild-type neurons throughout the broad concentration range studied. In the case of CNTF, where the difference in survival between wild-type and p65-deficient neurons was most pronounced, the number of wild-type neurons surviving with CNTF was more than fivefold greater than the number of p65-deficient neurons surviving with this factor over virtually the entire concentration range. These results indicate that the absence of p65 substantially reduces the ability of neurotrophic cytokines to promote the survival of developing nodose neurons. In contrast to the markedly impaired survival response of p65-deficient nodose neurons to cytokines, our previous work on the response of p65-deficient neurons to neurotrophins has demonstrated that the dose response of p65-deficient nodose neurons to BDNF is completely normal ( Hamanoue et al. 1999). This demonstrates that the impaired survival response of p65-deficient nodose neurons to cytokines is not some nonspecific detrimental effect of the lack of p65 on cell viability, but shows that p65 plays a highly selective role in mediating responses to certain neurotrophic factors.

Figure 5.

Graphs of the dose responses of E12 or E14 nodose neurons from wild-type and p65 −/− embryos to LIF, CT-1, CNTF, and IL-6. The means and standard errors of typical dose responses set up in triplicate are shown. The results of two to four separate dose response experiments for each factor at each age were very similar to the results illustrated.

Increased Apoptosis in the Nodose Ganglia of p65-deficient Embryos

To determine if the reduced survival response of p65-deficient nodose neurons to cytokines observed in vitro results in increased death of these neurons in vivo, we counted the total number of neurons in the nodose ganglia of wild-type and p65 −/− embryos and estimated the proportion of neurons undergoing apoptosis at E14. Embryos were fixed, embedded, and serially sectioned through the nodose ganglia and stained for neurofilament protein to positively identify all neurons. The number of neurons with pyknotic nuclei and the total number of neurons were counted in these sections. All histology slides were coded so that these estimates were made without knowledge of the genotype.

The number of cells undergoing apoptosis in the trigeminal ganglion was estimated by counting the number of pyknotic nuclei that were recognized as one or more darkly stained spherical structures contained within a clearly visible membrane. The great majority of pyknotic nuclei were observed in large degenerating cells, suggesting that these were neurons ( Oppenheim 1991). Fig. 6 shows that the number of pyknotic nuclei in the nodose ganglia of E14 p65 −/− embryos was almost threefold greater than in wild-type embryos of the same age. There was also a 30% reduction in the total number of neurons in the nodose ganglia of p65 −/− embryos at this age. The total number of neurons in the nodose ganglia of p65 +/− embryos was intermediate between the numbers in wild-type and p65 −/− embryos, indicating a gene dosage effect. These results indicate that the survival of p65-deficient nodose neurons is impaired in vivo.

Figure 6.

Bar charts of the number of pyknotic nuclei and total numbers of neurons in the nodose ganglia of E14 wild-type, p65 +/−, and p65 −/− embryos. The means and standard errors of the data obtained from five wild-type, seven p65 +/−, and seven p65 −/− embryos are shown.

Cytokine Receptor Expression Is Unaffected in p65-deficient Nodose Neurons

As NF-κB is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of many genes, it is possible that the reduced survival response of p65-deficient sensory neurons to cytokines is not a direct consequence of p65 being an integral component of a cytokine signaling pathway, but may be secondary to a reduction in cytokine receptor expression. There is evidence, for example, that NF-κB regulates the expression of the IL-2 receptor ( Cross et al. 1989). To explore the possibility that the selective reduction of the cytokine survival responses in p65-deficient neurons might be due to reduced expression of cytokine receptors, we used immunocytochemistry to assess the proportion of neurons that express cytokine receptor components in cultures established from the nodose ganglia of E12 and E14 wild-type, p65 +/−, and p65 −/− embryos. In these experiments, dissociated cultures of nodose neurons were cultured for six hours with a cocktail of cytokines and BDNF to sustain the survival of the maximum number of neurons. The cultures were then fixed and stained with antibodies to gp130, LIFRβ, CNTFRα, and IL-6Rα. Fig. 7 shows that the great majority of neurons exhibited positive staining for each of these receptors and that the percentage stained for each receptor was almost identical in wild-type and p65-deficient neurons. No neurons were stained in cultures that were not incubated with primary antiserum, but otherwise, were processed normally. These findings suggest that similar levels of cytokine receptors are expressed in p65-deficient and wild-type nodose neurons and that reduced receptor expression is unlikely to account for the decreased sensitivity of p65-deficient neurons to cytokines.

Figure 7.

Bar chart of the percentage of E14 nodose neurons in short-term cultures established from wild-type, p65 +/−, and p65 −/− embryos that are immunoreactive for gp130, LIFRβ, CNTFRα, and IL-6Rα. The means and standard errors of the percentage of labeled neurons in quadruplicate wells for each data point in a representative experiment are shown. Similar results were observed in two additional experiments carried out at E12 and E14.

Discussion

Using a variety of complementary experimental approaches, we have demonstrated that NF-κB plays a major role in mediating the survival response of embryonic sensory neurons to the neurotrophic cytokines, CNTF, LIF, CT-1, and IL-6. First, CNTF causes a marked activation of NF-κB in cultured trigeminal neurons. Second, preventing CNTF-induced NF-κB activation in these neurons with super-repressor IκBα causes a substantial reduction in the survival response of these neurons to CNTF. Likewise, super-repressor IκB causes a marked reduction in the survival response of nodose neurons to CNTF, LIF, and CT-1. Third, nodose neurons from p65 −/− embryos have a poor survival response to these cytokines compared with neurons from wild-type embryos. Fourth, increased numbers of cytokine-dependent nodose neurons die by apoptosis in p65 −/− embryos in vivo. Expression of the super-repressor IκB does not exert a nonspecific detrimental effect on neuronal survival because it has no effect whatsoever on the survival of nodose neurons grown with BDNF. Likewise, the poor survival of p65-deficient nodose neurons with neurotrophic cytokines does not represent a nonspecific detrimental effect of the absence of this protein on cell survival because the dose response of these neurons to BDNF is entirely normal. Furthermore, the selective reduction in the response of nodose neurons to cytokines is not due to reduced expression of cytokine receptors because the proportion of nodose neurons that express cytokine receptor subunits is completely unaffected by the p65 null mutation.

Previous work has shown that NGF activates NF-κB in developing sensory neurons by binding to the p75 neurotrophin receptor and that inhibiting NF-κB activation with super-repressor IκBα causes a small reduction in the number of neurons surviving with NGF ( Hamanoue et al. 1999). In contrast, the level of NF-κB activation induced by CNTF in the same sensory neurons is greater and the decrease in the survival response to this and other neurotrophic cytokines brought about by super-repressor IκB is substantially greater. These findings, together with our demonstration that the response of p65-deficient sensory neurons to neurotrophic cytokines is markedly reduced, indicate that NF-κB activation plays a much more prominent role in mediating the survival response of developing sensory neurons to cytokines than to NGF.

Although it has been established that binding of CNTF to its receptor complex activates directly or indirectly a number of signaling pathways, including the JAK-Stat, PI-3 kinase, Ras/MAP kinase, and PLC-γ pathways ( Boulton et al. 1994; Stahl et al. 1994; Frank et al., 1996), the mechanism by which CNTF promotes neuronal survival is not known. However, most signals that induce NF-κB do so by activation of the IκB kinases α and β. The activated kinases phosphorylate IκB-α on serines 32 and 36 leading to recognition of phosphorylated IκB-α by an SCF ubiquitin ligase complex containing βTrCP ( Maniatis 1999). Studies with knockout mice have indicated that, whereas IKKα appears to be involved in the development of skin and skeleton, IKKβ appears to participate in signaling mediated by the proinflammatory cytokines, TNFα and IL-1β ( May and Ghosh 1999). As CNTF signaling is blocked by the S32A/S36A mutant of IκBα that is unable to be phosphorylated by IKKα or IKKβ, it seems likely that CNTF signaling leads to activation of either IKKα or -β. In addition, it has recently been demonstrated that the PKB/Akt protein kinase, activated by PI-3 kinase, directly phosphorylates and activates IKKα, leading to NF-κB activation ( Ozes et al. 1999; Romashkova and Makarov 1999). Thus, a possible sequence of events after engagement of CNTF by its receptor complex is activation of PI-3 kinase, leading to activation of PKB/Akt, which in turn phosphorylates and activates IKKα, resulting in signal-induced degradation of IκBα and release of active NF-κB.

In addition to promoting neuronal survival, CNTF has many functions in different cell types, including regulation of neuroblast and oligodendrocyte proliferation ( Ernsberger et al. 1989; Barres et al. 1996), neuropeptide and neurotransmitter synthesis ( Ernsberger et al. 1989; Rao et al. 1992; Louis et al. 1993), rod cell differentiation ( Fuhrmann et al. 1998), and induction of acute phase proteins in hepatocytes ( Schooltink et al. 1992). It has yet to be ascertained which of the signaling pathways activated by CNTF mediate each of these cellular responses. Although LIF has been shown to activate NF-κB in phagocytes ( Gruss et al. 1992), we have shown for the first time that CNTF activates NF-κB in neurons and that this plays a major role in mediating the trophic actions of this and other cytokines.

Although the mechanism by which NF-κB activation promotes the survival of cytokine-dependent developing sensory neurons is unknown, there is growing evidence that NF-κB induces the expression of several genes encoding proteins that oppose the cell death program. It appears that prevention of TNFα-mediated apoptosis by NF-κB is a direct consequence of increased expression of genes encoding TRAF1, TRAF2, c-IAP1, and c-IAP2, which block caspase 8 activation ( Chu et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1998). Two other genes that appear to be important in protecting cells from TNF-induced apoptosis, A20 and IEX-1L, are also direct transcriptional targets of NF-κB ( Krikos et al. 1992; Wu et al. 1998). NF-κB induces expression of the Bcl-2 homolog A1 in B and T cells, which is critical for survival during lymphocyte activation ( Grumont et al. 1999; Zong et al. 1999), and NF-κB–mediated induction of Bcl-2 and Bcl-x also plays a role in the neuroprotective action of TNF against hypoxia- or nitric oxide-induced injury ( Tamatani et al. 1999).

In summary, we have provided the first evidence that NF-κB plays a major role in mediating the neurotrophic actions of cytokines. These findings not only have implications for understanding survival signaling in neurons during the critical stages of development when connections are being established, but raise questions about the importance of NF-κB for sustaining the survival of mature neurons and in neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Amer Beg and David Baltimore for generously making available the p65 knockout mice. Liz Alcamo's assistance in arranging transfer of the mice to St. Andrews is greatly appreciated. We thank Gene Burton and David Shelton of Genentech Inc. for the purified recombinant NGF and CNTF.

This work was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research Campaign.

Footnotes

Makoto Hamanoue's present address is Department of Molecular Neurobiology, Institute of DNA Medicine, Jikei University, School of Medicine, 3-25-8 Nishishinbashi, Minatoku, Tokyo 105, Japan.

Yasushi Enokido's present address is Division of Protein Biosynthesis, Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan.

Abbreviations used in this paper: BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factors; CT-1, cardiotrophin-1; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor; E, embryonic day; IL-6, interleukin 6; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; NGF, nerve growth factor; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NT, neurotrophin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

References

- Abercrombie M. Estimation of nuclear population from microtome sections. Anat. Rec. 1946;94:239–247 . doi: 10.1002/ar.1090940210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp T.E., Wyatt S., Paterson H.F., Davies A.M. The proto-oncogene bcl-2 can selectively rescue neurotrophic factor-dependent neurons from apoptosis. Cell. 1993;73:295–307 . doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90230-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle P.A., Baichwal V.R. NF-kappa B as a frequent target for immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory molecules. Adv. Immunol. 1997;65:111–137 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin A.S., Jr. The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteinsnew discoveries and insights. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:649–683 . doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barres B.A., Burne J.F., Holtmann B., Thoenen H., Sendtner M., Raff M.C. Ciliary neurotrophic factor enhances the rate of oligodendrocyte generation. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 1996;8:146–156 . doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan J.F. Neuropoietic cytokines in the hematopoietic fold. Neuron. 1991;7:197–208 . doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg A.A., Baltimore D. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science. 1996;274:782–784 . doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg A.A., Sha W.C., Bronson R.T., Ghosh S., Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1995;376:167–170 . doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton T.G., Stahl N., Yancopoulos G.D. Ciliary neurotrophic factor/leukemia inhibitory factor/interleukin 6/oncostatin M family of cytokines induces tyrosine phosphorylation of a common set of proteins overlapping those induced by other cytokines and growth factors. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:11648–11655 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B.D., Kaltschmidt C., Kaltschmidt B., Offenhauser N., Bohm-Matthaei R., Baeuerle P.A., Barde Y.A. Selective activation of NF-kappa B by nerve growth factor through the neurotrophin receptor p75. Science. 1996;272:542–545 . doi: 10.1126/science.272.5261.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z.L., McKinsey T.A., Liu L., Gentry J.J., Malim M.H., Ballard D.W. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor-induced cell death by inhibitor of apoptosis c-IAP2 is under NF-kappaB control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:10057–10062 . doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross S.L., Halden N.F., Lenardo M.J., Leonard W.J. Functionally distinct NF-kappa B binding sites in the immunoglobulin kappa and IL-2 receptor alpha chain genes. Science. 1989;244:466–469 . doi: 10.1126/science.2497520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A.M. The survival and growth of embryonic proprioceptive neurons is promoted by a factor present in skeletal muscle. Dev. Biol. 1986;115:56–67 . doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A.M., Lee K.F., Jaenisch R. p75-deficient trigeminal sensory neurons have an altered response to NGF but not to other neurotrophins. Neuron. 1993;11:565–574 . doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S., Aldrich T.H., Ip N.Y., Stahl N., Scherer S., Farruggella T., DiStefano P.S., Curtis R., Panayotatos N., Gascan H. Released form of CNTF receptor alpha component as a soluble mediator of CNTF responses. Science. 1993;259:1736–1739 . doi: 10.1126/science.7681218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernsberger U., Sendtner M., Rohrer H. Proliferation and differentiation of embryonic chick sympathetic neuronseffects of ciliary neurotrophic factor. Neuron. 1989;2:1275–1284 . doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D.A., Greenberg M.E. Signal transduction pathways activated by ciliary neurotrophic factor and related cytokines. Perspect. Dev. Neurobiol. 1996;4:3–18 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann S., Heller S., Rohrer H., Hofmann H.D. A transient role for ciliary neurotrophic factor in chick photoreceptor development. J. Neurobiol. 1998;37:672–683 . doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199812)37:4<672::aid-neu14>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., May M.J., Kopp E.B. NF-kappa B and Rel proteinsevolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:225–260 . doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumont R.J., Rourke I.J., Gerondakis S. Rel-dependent induction of A1 transcription is required to protect B cells from antigen receptor ligation-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:400–411 . doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss H.J., Brach M.A., Herrmann F. Involvement of nuclear factor-kappa B in induction of the interleukin-6 gene by leukemia inhibitory factor. Blood. 1992;80:2563–2570 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini L., Blasi F., Denis-Donini S. Synaptic activation of NF-kappa B by glutamate in cerebellar granule neurons in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9077–9081 . doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamanoue M., Middleton G., Wyatt S., Jaffrey E., Hay R.T., Davies A.M. p75-mediated NF-kB activation enhances the survival response of developing sensory neurons to nerve growth factor. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1999;14:28–40 . doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton A.R., Laramee G., Wyatt S., Shih A., Winslow J., Davies A.M. NGF binding to p75 enhances the sensitivity of sensory and sympathetic neurons to NGF at different stages of development. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1997;10:162–172 . doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton A.R., Barlett P.F., Pennica D., Davies A.M. Cytokines promote the survival of mouse cranial sensory neurons at different developmental stages. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:673–679 . doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltschmidt C., Kaltschmidt B., Baeuerle P.A. Stimulation of ionotropic glutamate receptors activates transcription factor NF-kappa B in primary neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9618–9622 . doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M. The NF-kappa B activation pathwayits regulation and role in inflammation and cell survival. Cancer J. Sci. Am. 1998;4:S92–S99 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krikos A., Laherty C.D., Dixit V.M. Transcriptional activation of the tumor necrosis factor alpha-inducible zinc finger protein, A20, is mediated by kappa B elements. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:17971–17976 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.F., Davies A.M., Jaenisch R. p75-deficient embryonic dorsal root sensory and neonatal sympathetic neurons display a decreased sensitivity to NGF. Development. 1994;120:1027–1033 . doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis J.C., Magal E., Burnham P., Varon S. Cooperative effects of ciliary neurotrophic factor and norepinephrine on tyrosine hydroxylase expression in cultured rat locus coeruleus neurons. Dev. Biol. 1993;155:1–13 . doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggirwar S.B., Sarmiere P.D., Dewhurst S., Freeman R.S. Nerve growth factor-dependent activation of NF-kappaB contributes to survival of sympathetic neurons. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:10356–10365 . doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10356.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T. A ubiquitin ligase complex essential for the NF-κB, Wnt/Wingless, and Hedgehog signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 1999;13:505–510 . doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M.P., Goodman Y., Luo H., Fu W., Furukawa K. Activation of NF-kappaB protects hippocampal neurons against oxidative stress-induced apoptosisevidence for induction of manganese superoxide dismutase and suppression of peroxynitrite production and protein tyrosine nitration. J. Neurosci. Res. 1997;49:681–697 . doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19970915)49:6<681::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May M.J., Ghosh S. IκB kinaseskinsmen with different crafts. Science. 1999;284:271–273 . doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald N.Q., Panayotatos N., Hendrickson W.A. Crystal structure of dimeric human ciliary neurotrophic factor determined by MAD phasing. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. 1995;14:2689–2699 . doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton G., Hilton M., Piñón L.G.P., Wyatt S., Davies A.M. Bcl-2 accelerates the maturation of early sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:3344–3350 . doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03344.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill L.A., Kaltschmidt C. NF-kappa Ba crucial transcription factor for glial and neuronal cell function. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:252–258 . doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim R.W. Cell death during development of the nervous system. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 1991;14:453–501 . doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozes O.N., Mayo L.D., Gustin J.A., Pfeffer S.R., Pfeffer L.M., Donner D.B. NF-κB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85 . doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñón L.G.P., Minichiello L., Klein R., Davies A.M. Timing of neuronal death in trkA, trkB, and trkC mutant embryos reveals developmental changes in sensory neuron dependence on Trk signalling. Development. 1996;122:3255–3261 . doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M.S., Tyrrell S., Landis S.C., Patterson P.H. Effects of ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and depolarization on neuropeptide expression in cultured sympathetic neurons. Dev. Biol. 1992;150:281–293 . doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R.C., Grey L.M., Staunton D., Vankelecom H., Vernallis A.B., Moreau J.F., Stuart D.I., Heath J.K., Jones E.Y. The crystal structure and biological function of leukemia inhibitory factorimplications for receptor binding. Cell. 1994;77:1101–1116 . doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M.S., Wright J., Thompson J., Thomas D., Baleux F., Virelizier J.L., Hay R.T., Arenzana-Seisdedos F. Identification of lysine residues required for signal-induced ubiquitination and degradation of I kappa B-alpha in vivo. Oncogene. 1996;12:2425–2435 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roff M., Thompson J., Rodriguez M.S., Jacque J.M., Baleux F., Arenzana-Seisdedos F., Hay R.T. Role of IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in signal-induced activation of NFkappaB in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7844–7850 . doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romashkova J.A., Makarov S.S. NF-κB is a target of AKT in anti-apoptotic PDGF signalling. Nature. 1999;401:86–90 . doi: 10.1038/43474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryden M., Hempstead B., Ibanez C.F. Differential modulation of neuron survival during development by nerve growth factor binding to the p75 neurotrophin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:16322–16328 . doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooltink H., Stoyan T., Roeb E., Heinrich P.C., Rose-John S. Ciliary neurotrophic factor induces acute-phase protein expression in hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 1992;314:280–284 . doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendtner M., Carroll P., Holtmann B., Hughes R.A., Thoenen H. Ciliary neurotrophic factor. J. Neurobiol. 1994;25:1436–1453 . doi: 10.1002/neu.480251110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl N., Yancopoulos G.D. The tripartite CNTF receptor complexactivation and signalling involves components shared with other cytokines. J. Neurobiol. 1994;25:1454–1466 . doi: 10.1002/neu.480251111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl N., Boulton T.G., Farruggella T., Ip N.Y., Davis S., Witthuhn B.A., Quelle F.W., Silvennoinen O., Barbieri G., Pellegrini S. Association and activation of Jak-Tyk kinases by CNTF-LIF-OSM-IL-6 beta receptor components. Science. 1994;263:92–95 . doi: 10.1126/science.8272873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamatani M., Che Y.H., Matsuzaki H., Ogawa S., Okado H., Miyake S., Mizuno T., Tohyama M. Tumor necrosis factor induces Bcl-2 and Bcl-x expression through NFkappaB activation in primary hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8531–8538 . doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Antwerp D.J., Martin S.J., Kafri T., Green D.R., Verma I.M. Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:787–789 . doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma I.M., Stevenson J. IkappaB kinasebeginning, not the end. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11758–11760 . doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.Y., Mayo M.W., Baldwin A.S., Jr. TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosispotentiation by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:784–787 . doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.-Y., Mayo M.W., Korneluk R.G., Goeddel D.V., Baldwin A.S. NF-κB apoptosisinduction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281:1680–1683 . doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollert K.C., Taga T., Saito M., Narazaki M., Kishimoto T., Glembotski C.C., Vernallis A.B., Heath J.K., Pennica D., Wood W.I., Chien K.R. Cardiotrophin-1 activates a distinct form of cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy. Assembly of sarcomeric units in series via gp130/leukemia inhibitory factor receptor-dependent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:9535–9545 . doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M.X., Ao Z., Prasad K.V., Wu R., Schlossman S.F. IEX-1L, an apoptosis inhibitor involved in NF-kappaB-mediated cell survival. Science. 1998;281:998–1001 . doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong W.X., Edelstein L.C., Chen C., Bash J., Gelinas C. The prosurvival Bcl-2 homolog Bfl-1/A1 is a direct transcriptional target of NF-kappaB that blocks TNFalpha-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:382–387. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]