Abstract

Childbirth education was an important social movement in the 20th century but has lost its way in recent years. We describe the reasons for the dwindling importance of childbirth education and offer a proposal for reform that will align childbirth education with the needs of today's birthing mothers. Our plan will create “Centers for the Childbearing Year” (CCBYs) and a new model of childbirth educator, which we call the “birth coach.” The CCBY is the place for women to go to for information and support related to fertility, pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn care; the birth coach combines the role of childbirth educator, doula, and postpartum caregiver. In creating a fresh model of childbirth education, we not only honor our pioneers but also rediscover the wisdom in community and relationship that childbirth offers us, and we learn in new ways to journey alongside each other to create new possibilities for birthing families.

Keywords: childbirth education, doulas, social movements, trends in birth

Quick, what does the following list suggest to you: Lamaze classes; baby showers; “parenting skills”; preschool anxiety all the way up to college; …midlife crises; an uneasy feeling of identification with Bob Dylan; …a denial of death; …an excessively personalized vision of retirement?… If you still haven't figured out that I'm talking about the so-called baby-boomer generation, you might consider the possibility that the reason you are having difficulty making out the fine print of any given subtext is because you need reading glasses. (Merkin, 2007, p. 21)

Ouch! “Lamaze classes” lead the list in a long litany of the passé in this recent New York Times Magazine article on, of all things, the aging of the baby-boom generation. Has childbirth education really gone the way of tie-dyed t-shirts, macramé, and sand candles? Are we who believe childbirth education classes should be at the forefront of the pregnancy experience caught in a time warp? How could Elisabeth Bing1 and her empowering ideas on psychoprophylaxis bring about so much change in the mid-20th-century birth scene only to become culturally irrelevant in the 21st century?

“You've come a long way, baby” is a familiar advertising phrase to many who are reading this article. But ask people under the age of 40, and most won't know a thing about this “feminist” advertisement for Virginia Slims cigarettes that hit the public eye in the late 1960s. The marketing campaign was shelved in 1986 because it had grown passé. The culture had changed, and the message had grown stale. Likewise, there was a time when it was hip to grab your partner, pack your pillow under your arm, and trudge off to your Lamaze classes. Now that we're well into a new century, have things changed enough that women want and/or need a new way to learn about birth?

THE CHANGING FACE OF BIRTH

The “who” and “how” of birth vary markedly by place and time. When we look around the world, we find great differences in age at first birth, definitions of “legitimate” and “illegitimate” children, appropriate maternity caregivers, place of birth, and the rituals that accompany birth. These differences are most obvious when one compares dissimilar cultures; for example, no one is surprised to find that agrarian women in rural Mexico have a definition of a “proper” birth that is quite unlike the definition shared by middle-class women who live in the suburbs of the United States.

It is more surprising to learn that societies/cultures that seem to be similar have widely disparate conceptions of a “good” birth.2 Dutch society, for instance, is not unlike other European or North American societies—prosperous, well-educated, with a well-organized and technologically sophisticated health-care system—yet, women there have a distinctly peculiar perception of a pleasing birth: More than 50% of pregnant women in the Netherlands choose midwife care, and more than 40% choose to have their babies at home (De Vries, 2005). These numbers stand in stark contrast to the rest of the modern world: In the United States, fewer than 10% of pregnant women seek the care of a midwife, and no country with a modern medical system has a home-birth rate more than 3% (De Vries, 2005).

More than 50% of pregnant women in the Netherlands choose midwife care, and more than 40% choose to have their babies at home.

It is perhaps most surprising for members of a given society to see how their way of birth changes over time. Ironically, changes in birth that occur over time within one society are least likely to be noticed by those providing maternity care. The training a health-care provider receives is a strong determinant of practice patterns over a career. If a doctor does an obstetric residency at a time period when age at first birth is early 20s, and the vast majority of birthing women come from one ethnic group, and most mothers are not employed before or immediately after giving birth, these factors become what that obstetrician “knows” about birth. What a caregiver “knows” shapes what that caregiver sees—“you see what you know, and you know what you see”—and, in turn, the way a caregiver practices.

Examples of the link between training and career practice abound. In a study of how often an obstetrician intervenes in birth, researchers discovered that physician intervention was best predicted not by the clinical condition of the mother, but by characteristics of the obstetrician—most importantly, by the person who directed the obstetrician's residency program (Pel, Heres, Hart, van der Veen, & Treffers, 1995). As Pel et al. put it, “[T]he effect of one's teacher strikes early and strikes hard” (p. 132). Another example comes from the underappreciated effect of women's employment on optimal positioning of the fetus. Sutton and Scott published their important research on fetal position in 1996, but obstetricians continue to act as if the increase in posterior presentations at birth is unrelated to changes in the lives of women over the last 50 years. Search the medical literature on fetal positioning, and you will find nary an acknowledgement related to changes in women's posture that are the result of office work and commuting.3

We, the advocates of childbirth education, also have failed to notice changes in birth that have occurred over the past three or four decades. We have not paid sufficient attention to who is having babies and how those babies are being born.

Who Is Giving Birth Today?

Table 1 is remarkable for several reasons. Not only does it reveal significant change in the demographics of birth, it also shows our blindness to ethnicity. Notice how the percent of White births drops over the 35-year period. But look again. How do we count White births? Before 1980, we looked at the ethnicity of the child; from 1980 on, we recognized that mother and child ethnicity were not always the same, and we began to record births by the mother's ethnicity. In 1995, we officially recognized that “White” was not really an ethnic category: Hispanic women were counted separately, resulting in a more accurate record of White (now, “non-Hispanic”) births.

TABLE 1.

Number of Births, United States, 1970–2005, White/Nonwhite (× 1,000)

| Year | All Ethnicities | White | Percent White |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 3,731 | 3,091 | 82.85 |

| 1975 | 3,144 | 2,552 | 81.17 |

| 1980a | 3,612 | 2,936 | 81.28 |

| 1985 | 3,761 | 3,038 | 80.78 |

| 1990 | 4,158 | 3,290 | 79.12 |

| 1995b | 3,900 | 2,383 | 61.11 |

| 2000 | 4,059 | 2,363 | 58.22 |

| 2005 | 4,140 | 2,285 | 55.19 |

Beginning in 1980, reported ethnicity is the mother's; in prior years, the child's ethnicity was reported.

Beginning in 1995, the number of births to Whites excludes Hispanic Whites.

Source: Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Sutton, P. D., Ventura, S. J., Menacker, F., & Kirmeyer, S. (2006). Births: Final data for 2004. National Vital Statistics Reports, 55(1). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

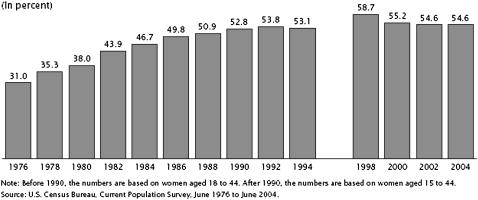

Table 2 and Figure 1 give us more information about today's mothers. Table 2 shows that women are delaying having children. Although an increase in age at first birth of 2 1/2 years over a 24-year span may seem insignificant, it signals an important shift in the social circumstances of mothers. More and more women are fitting childbirth and children into careers shaped by demands of education and the workplace. This fact is underscored by Figure 1, which shows a considerable increase in the number of women who go back to work within 1 year of the birth of their child (31.0% in 1976; 54.6% in 2004).

TABLE 2.

Mother's Mean Age at First Birth, United States, 1980–2004

| Year | Mean Age at First Birth |

|---|---|

| 1980 | 22.7 |

| 1985 | 23.7 |

| 1990 | 24.2 |

| 1995 | 24.5 |

| 2000 | 24.9 |

| 2004 | 25.2 |

Note. From Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Sutton, P. D., Ventura, S. J., Menacker, F., & Kirmeyer, S. (2006). Births: Final data for 2004. National Vital Statistics Reports, 55(1). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Labor Force Participation Rates of Women Who Had a Child in the Last Year for Selected Years: June 1976 to June 2004

Compared to the days when Lamaze International was founded, today's mothers are more likely to be single. In 1984, births to unmarried women accounted for 18.4% of all births; by 2003, that number had nearly doubled to 34.6% (see Table 3). Although the situations of unmarried women vary, this increase indicates important changes in the experience of pregnancy and birth and in the lives of new mothers. The increase in the number of working moms, changes in the ethnic composition of birthing mothers, and new domestic arrangements combine to suggest that the picture of pregnant moms and dads enjoying their evening Lamaze classes (in the home of the educator or in the hospital) no longer rings true.

TABLE 3.

Number and Percentage of Births to Unmarried Women in the United States, 1980 and 1985–2003

| Year | Number of Births to Unmarried Women | Percentage of All Births |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 1,415,995 | 34.6 |

| 2002 | 1,365,966 | 34.0 |

| 2001 | 1,349,249 | 33.5 |

| 2000 | 1,347,043 | 38.2 |

| 1999 | 1,308,560 | 38.0 |

| 1998 | 1,293,567 | 32.8 |

| 1997 | 1,257,444 | 32.4 |

| 1996 | 1,260,306 | 32.4 |

| 1995 | 1,253,976 | 32.2 |

| 1994 | 1,289,582 | 32.6 |

| 1993 | 1,240,172 | 31.0 |

| 1992 | 1,224,676 | 30.1 |

| 1991 | 1,213,769 | 29.5 |

| 1990 | 1,165,384 | 28.0 |

| 1989 | 1,094,169 | 27.1 |

| 1988 | 1,005,299 | 25.7 |

| 1987 | 933,013 | 24.5 |

| 1986 | 878,477 | 23.4 |

| 1985 | 828,174 | 22.0 |

| 1980 | 665,747 | 18.4 |

Note. From Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Sutton, P. D., Ventura, S. J., Menacker, F., & Munson, M. L. (2005). Births: Final data for 2003. National Vital Statistics Reports, 54(2). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

How Are Today's Women Giving Birth?

What has happened to the way women give birth in America? Much to the dismay of those of us who have been struggling to promote and protect normal birth, little has changed over the past 40 years. Table 4 shows that the hospital remains the location of birth for moms in the United States; thus, the dreams of those who hoped to demedicalize birth by moving it into birth centers and homes have not been realized. Yes, midwives have made some inroads as caregivers at birth—the overwhelming majority of births not attended by physicians are attended by midwives (Table 4)—but hopes of a greatly expanded midwife workforce in the United States remain just that: a hope for the future.

TABLE 4.

Location of Birth and Attendant, United States, 1975–2000

| Year | Percent of Births in the Hospital | Percent of Births Attended by Physicians |

|---|---|---|

| 1975 | 99.11 | 96.6 |

| 1980 | 99.01 | 97.2 |

| 1985 | 99.0 | 96.6 |

| 1990 | 98.9 | 94.9 |

| 1995 | 99.0 | 93.3 |

| 2000 | 99.06 | 91.7 |

Note. From National Center for Health Statistics. (2007). Vital statistics of the United States, 2001: Vol. 1. Natality. Retrieved August 28, 2007, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/datawh/statab/unpubd/natality/natab2001.htm

Much to the dismay of those of us who have been struggling to promote and protect normal birth, little has changed over the past 40 years.

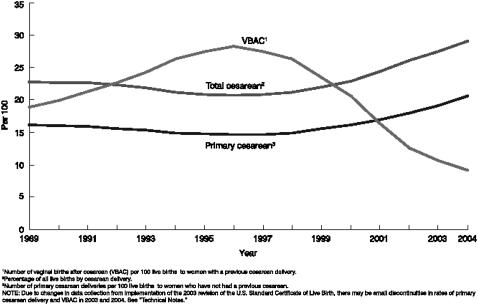

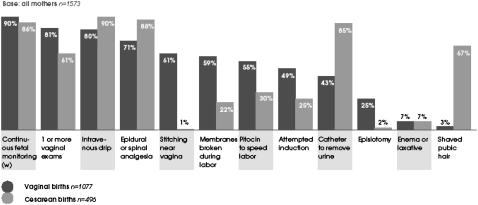

Data from a variety of sources show intervention in birth becoming commonplace. Figure 2 illustrates the well-known increase in surgical births, which, as of 2005, is more than 30%.4Table 5, drawn from the research of Simpson and Atterbury (2003), maps the increase in selected obstetrical interventions in the last quarter of the 20th century. And Figure 3, taken from the second Listening to Mothers survey (Declercq, Sakala, Corry, & Applebaum, 2006), gives us a snapshot of the kind and number of interventions in birth among women who had their babies in 2005 in the United States.

Total and Primary Cesarean Rate and Vaginal-Birth-After-Cesarean Rate: United States, 1989–2004

TABLE 5.

Rates of Selected Obstetric Interventions, 1975–2000

| Rate per 100 births | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amniotomy | 3.2 | 8.2 | 17.2 | 20.0 | 22.3 | |

| Labor induction w/medical indication | 1.1 | 1.7 | 5.6 | 9.7 | 11.7 | |

| Induction of labor (total) | 9.5 | 16.0 | 19.9 | |||

| Augmentation of labor | 11.4 | 16.1 | 17.9 | |||

| Electronic fetal monitoring | 22.3 | 54.8 | 63.4 | 73.2 | 81.3 | 84.0 |

| Cesarean birth | 10.4 | 16.5 | 22.7 | 23.5 | 20.8 | 22.9 |

| Cesarean birth primarya | 7.8 | 12.1 | 16.3 | 16.8 | 15.5 | 16.1 |

| Cesarean birth repeatb | 27.1 | 29.9 | 34.6 | 35.9 | 33.9 | 37.9 |

| Vaginal birth after cesareanc | 2.2 | 3.4 | 6.6 | 20.4 | 35.5 | 27.6 |

| Rate per 100 vaginal births | ||||||

| Operative vaginal birth | ||||||

| Forceps birth | 17.6 | 12.5 | 8.6 | 5.8 | 4.0 | |

| Vacuum | 0.7 | 2.2 | 6.1 | 9.2 | 8.4 | |

| Episiotomy | 64.0 | 61.1 | 55.6 | 47.2 | 32.7 |

Rate per 100 births without previous cesarean.

Rate per 100 cesarean births.

Rate per 100 births with previous cesarean birth.

Source: Simpson, K. R., & Atterbury, J. (2003). Trends and issues in labor induction in the United States: Implications for clinical practice. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 32(6), 767–779.

Use of Selected Interventions, by Mode of Birth, 2005

Taken together, this news is not encouraging for an organization whose mission is “to promote, support, and protect normal birth through education and advocacy” (Lamaze International, n.d., 1st paragraph). Yes, fathers and others are allowed to be present at birth and, yes, episiotomy rates have fallen. But these are small gains in a struggle to create “a world of confident women choosing normal birth” (Lamaze International, n.d., 1st paragraph).

LAMAZE INTERNATIONAL AND THE CULTURE OF TODAY'S BIRTHING WOMEN

These data about changes in the “who” and “how” of birth over the last 40 years point to the need for proactive change in childbirth education. But when we consider the growth and development of childbirth education in the last half-century, we find that the changes that have occurred are reactive. Admittedly, childbirth educators are in something of a sociological fix. That is, childbirth education is a profession that relies on the knowledge of another professional group and, in many cases, serves at the pleasure of members of that group (De Vries, 1989). Lacking professional independence, childbirth educators have been subject to push factors from medical organizations, other health professionals, and clients. Educators have had to move their classes from their homes to hospitals; they have been required to add content to their courses (e.g., the pharmacological aspects of labor and birth); and they have been forced to offer condensed courses and weekend cram sessions. In a recent Zoomerang survey of Lamaze educators, 73% of respondents indicated that they felt their teaching was strongly or somewhat censured.5 Admittedly a Zoomerang survey is not a scientific study, but it clearly indicates the pressure that childbirth educators are under.

Those who began the childbirth-education movement were pioneers. They captured the cultural mood of the 1960s and used it to help humanize an American way of birth that absented mothers from childbirth. But, as with any social movement, the initial pioneering spirit inevitably gives way to the need to get organized, to secure the future of the profession, and to establish new professionals as experts with control over a specified area of knowledge. It is this tension between pioneer and professional that animates much of what occurs in the organizations of childbirth education. As one group becomes too established—too much a part of the birthing establishment—other groups spring up to preserve the original spirit of the movement. The “Birthing Naturally” Web site lists 16 different childbirth education organizations ranging from Apple Tree Family Ministries to Lamaze International to Hypnobabies Network.6

Lamaze International can be proud of its organizational past. Although there was a period when Lamaze (then ASPO/Lamaze, the American Society for Psychoprophylaxis in Obstetrics) was accused of having sold out (the “Lamaze method” was charged by some with being a male invention meant to replace another male invention of obstetric anesthesia), in the early 1990s, the organization reinvented itself as the champion of normal birth. In pursuit of its goal of promoting and protecting normal birth, Lamaze has refused money from companies making breast-milk substitutes (scrupulously following the World Health Organization code in this regard), developed a philosophy of birth that supports birth at home and in hospitals, and created the Lamaze Institute for Normal Birth in order to collect and disseminate scientific evidence in support of its Six Care Practices That Support Normal Birth (Lamaze International, 2007).

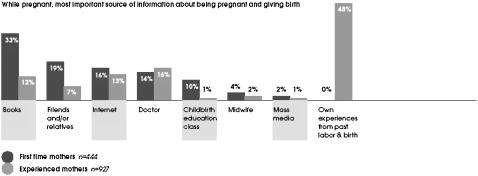

Although Lamaze has much to be proud of, this is no time for self-congratulation. The irrelevance of childbirth education is underscored by the Listening to Mothers II (LTM II) survey (Declercq et al., 2006). Percentage rates presented in Table 6 and Figure 4, taken from the report on LTM II, serve as a wake-up call. In 2005, only 56% of first-time mothers took childbirth education classes, and only 10% of that group mentioned childbirth education classes as the most important source of information about pregnancy and birth.

TABLE 6.

Childbirth Education Class Participation in Current or Past Pregnancy

| First-time mothers n=519 | Experienced mothers n=1,054 | All mothers n=1,573 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 56%* | 9% | 25% |

| No | 44% | 75% | |

| No, took classes before | 47% | ||

| No, never took classes | 44% |

p < .01 for difference between first-time and experienced mothers

Note. From Declercq, E. R., Sakala, C., Corry, M. P., & Applebaum S. (2006). Listening to mothers II: Report of the second national U.S. survey of women's childbearing experiences (p. 24). New York: Childbirth Connection.

Sources of Pregnancy and Childbirth Information, by Birth Experience

How can this be? What has happened? How did childbirth education drop by the wayside of pregnancy and birth? The answers to these questions can be found in a careful reading of the ethnographic study of childbirth education commissioned by Lamaze International (Morton & Hsu, 2007).

Considered together with the data on the changing face of birth, the conclusions of Morton and Hsu's (2007) study point to the fact that childbirth education in general, and Lamaze classes in particular, are woefully out-of-date. This is not just a matter of adopting “hip” language (“Like, she was sooo totally preggers, ya know?”) or getting your Web site up and running; rather, it is finding a way to connect with childbearing women at a deep and meaningful level. It will require rethinking everything from the content to the organization and location of our classes.

Morton and Hsu (2007) point to several disconnects in childbirth education. They found a mismatch between what teachers offered and what students wanted—a cultural bias embedded within the structure and message of contemporary childbirth education, a loss of community in childbirth classes, and an abdication of responsibility in the name of “choice.”

Today's women demand choice, a problematic thing for Lamaze International. Historically, we have been ambivalent about telling a woman what to do. We also have feared alienating hospitals and physicians. We are caught in the middle. Today's rate of surgical birth points squarely to the problem with choice when it comes to having babies: Women may come to our Lamaze classes, but many of them are not choosing the Lamaze philosophy when push comes to scalpel.

FACING THE FUTURE: A NEW MODEL FOR CHILDBIRTH EDUCATION

How can we take the Lamaze philosophy of birth (a good thing) and reshape and re-enliven it to make it relevant to birthing women in the 21st century? Lamaze International, together with childbirth educators of every stripe, needs to enter a new era where we cooperate with each other professionally, revitalize our philosophy, and grow in new ways into a profession that has a stronger, more vital voice in a world that needs to rethink how it views birth.

New Organization for a New Century

The model of childbirth education that was created in the 1960s fits well with the ethos of the era—it was a time of self-help, of grassroots organizing, of coming together to resist the “establishment.” Small classes in homes and hospitals created moments of solidarity for baby-boomer parents looking to find “their own path” in birth. This model of childbirth education fits poorly with today's parents (see Table 4). We need to find a new way to deliver much-needed information to moms and their partners—a method that will appeal to on-the-go, overworked, employed mothers from a variety of ethnic groups, living in a variety of relationships. In short, childbirth education must be organized to meet the needs of today's women.

Facing the cultural and social variety of today's birthing women may lead one to conclude that we need to develop an array of classes and approaches targeted to the specific needs of each type of woman. This is a dangerous idea. If we—the childbirth education community—continue to specialize and divide and split off from each other, we will continue to be subject to the authority and direction of doctors and obstetric specialists. By default, physicians' offices will become the centers of information about birth. Doctors will direct their clients to childbirth educators, exercise programs, doulas, and lactation consultants who fit with their idea of a good birth.

We need to find a way to respond to the diversity of today's mothers without diluting the important role of childbirth education.

We propose abandoning home- and hospital-based classes and creating community centers for the childbearing year. Our inspiration comes from The Center for the Childbearing Year (CCBY) in Ann Arbor, Michigan, an organization that “promotes healthy families by fostering a community that educates, empowers, and supports pregnant women, their growing families, and professionals who work with them during the childbearing year” (CCBY, 2006, 1st paragraph). Centers for the Childbearing Year will be the place for women to go for information and support related to fertility, pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn care. These centers will offer:

advice and information about getting pregnant;

childbirth education—either a “birth coach” (see below) or classes at the center;

caregiver recommendations (reviews of midwives, physicians, nurse practitioners, therapists, and hospitals);

exercise and nutrition classes;

a resource/media center on all aspects of childbearing and parenting;

lactation consulting;

parent and play groups; and

opportunities for mentoring and community activities.

This model has several advantages. Most importantly, CCBYs shift the balance of power at birth. As a point of first contact, CCBYs will gain control of the birthing market in their community. When doctors refer mothers to childbirth educators, doctors retain control, sending pregnant women only to classes with physician-approved content. When CCBYs refer mothers to doctors (and midwives and hospitals), they gain control. Doctors will notice and respond when the women begin to avoid their practices because of negative reviews by moms and the staff of the CCBY. Of course, this shift of power can only occur if the CCBY remains independent of medical practices and hospitals. If the CCBY model catches on, there no doubt will be an effort by large medical centers to create their own center or buy up the local center.

The CCBY provides a supportive community for the many women who lack a natural community of relatives and friends with knowledge of birth. Because CCBYs draw women from across the community, there will be greater opportunity for like-situated mothers to find each other, as compared to a luck-of-the-draw childbirth education class, where a woman might find she is the only one from her ethnic group, social class, age group, etc. The CCBY draws on and builds community, inspiring mutual confidence in pregnancy and early mothering and building friendships that start “on the same page.”

The CCBY also creates a solid base for childbirth education professionals, drawing together the resources of a community and the women and families who need them. At present, many childbirth educators struggle to survive on their own, hunting for clients and often serving at the pleasure of hospital administrators.

Finally, the CCBY will improve the health of moms, babies, and families. A recent study by Ickovics et al. (2007) provides evidence that birth outcomes improve when prenatal care is offered in a community setting to like-situated women. In a world where new mothers often feel isolated, the CCBY shines. And what better model can Lamaze International offer than a relational one that offers a broader support, going beyond the classroom and into each other's lives, one-on-one and in community?

The New Birth Coach

You may think the CCBY is simply a place to run good-old-fashioned Lamaze classes. Wrong. As we noted above, the pillow-under-the-arm, let's-all-get-on-the-floor type of class has ceased to appeal to today's mothers. We need a new model here as well. To build that model, we need to look at what is working in childbirth education. Today's success story in birth is the doula. Table 7 offers evidence of this success: Membership in Doulas of North America (DONA) International has skyrocketed, growing from 750 to more than 6,000 in just 12 years. By way of contrast, the number of childbirth educators has stagnated—neither Lamaze International nor the International Childbirth Education Association could offer an exact count of certified educators, but combining their best guesses results in about 7,000 childbirth educators. And this after 40-plus years!

TABLE 7.

Membership in DONA (Doulas of North America) International, 1994–2006

| 1994 | 750 |

| 1995 | 1,200 |

| 1996 | 1,800 |

| 1997 | 2,050 |

| 1998 | 2,400 |

| 1999 | 2,800 |

| 2000 | 3,350 |

| 2001 | 3,800 |

| 2002 | 4,550 |

| 2003 | 4,906 |

| 2004 | 5,221 |

| 2005 | 5,842 |

| 2006 | 6,137 |

Note. From DONA International. (n.d.). Member statistics. Retrieved August 27, 2007, from http://www.dona.org/aboutus/statistics.php

Like Lamaze in the 1960s, DONA International connects with the culture of today, offering a model that fits with the cultural turn toward “life coaches.” Life coaching is the practice of assisting clients to determine and achieve their personal goals, using a variety of methods tailored in content, organization, and location to the client's life situation. Life coaches build relationship with their clients in order to gain their trust, to help build confidence, and to better understand a client's character, hopes for the future, and strengths—in short, to help clients be their best selves and to experience success in their undertakings.

We propose a new kind of educator who builds on the best of the doula and the traditional childbirth educator: the “birth coach.” The new birth coach is different from the old (often Bradley-Method-linked) model—the partner or friend who offered verbal support during labor to help a woman give birth naturally. The new birth coach is much more—a professional who is trained to be an “accompanist”; to enter a client's life in the first months of pregnancy; to form a bond of mutual trust and confidence; to share stories, understandings, wisdom, and experiences; to help unpack questions around this unique life passage of giving birth; and to offer continuous support after the baby has arrived. The new birth coach would provide an individualized education for clients in a relaxed setting of mutual choice. She would continue on as her client's doula, remaining quietly present even as the nursing staff changes shifts during labor. And she would serve as a kraamverzorgster—a wonderful Dutch term for a “postpartum caregiver” who visits the home to observe how the mother and baby are faring, to offer instruction in baby care and feeding, and to help with simple household chores during the transitions a newborn can bring to the home front.7

Stepping beyond the boundaries of classroom instructor, the new birth coach becomes something more—confidante, teacher, doula, caregiver—in her new role accompanying a client in her journey through pregnancy, contracting to offer one-on-one support to one client. Evidence has shown how education better prepares a woman in pregnancy and birth and how the presence of a doula paves the way for a better labor and birth. Add these qualities to the benefit of continuity of care from a confidante that the birth coach can become and the opportunity for encouragement and confidence building over the months that lead to and follow the birth. Moreover, the birth coach becomes a person who is privileged to hold the story of one baby's beginning and one woman's pregnancy in her memory.

Given the many responsibilities of the birth coach, a new training program will need to be created. A Lamaze International birth coach must be trained as a doula and a childbirth educator and know something of social work, lactation consulting, and running a business. The coach becomes the very model of a modern “professional-plus.”

This will not be easy. But the creation of a training program for birth coaches could bring about much needed cooperation between the many groups in the childbirth education market. At present, childbirth education suffers from unproductive internal competition. There are at least 15 ways to be certified as a childbirth educator, many specialties and subspecialties, and, of course, the possibility of just calling yourself a childbirth educator. The Coalition for Improving Maternity Services (born out of the “Winds of Change” Lamaze meeting held in Chicago in 1994) was an effort to align the interests of these many groups, but working together to create the birth-coach program would bring real and important unification. And just think how annual meetings would be revitalized as the depth and breadth of the new model leads to expanded horizons in learning from and working with each other!

Combining the CCBY and the Birth Coach: One-Stop Shopping

The combination of the CCBY and the birth coach offers a new way of being with pregnant and birthing women. We realize that not all women may want or can afford a birth coach. The services of a birth coach will appeal to middle-, upper-middle-, and upper-class women who can afford the luxury of one-on-one care. But the CCBY can organize more traditional classes and provide the space for women to meet and mentor each other.

The CCBY model can be expanded (or contracted) to fit the needs of the local community. For example, the CCBY can generate additional support by selling birth-related items, books, maternity clothes, and baby clothes. The center may also be used as a clinic for prenatal care offered in conjunction with childbirth classes. Additionally, CCBYs might be able to negotiate with local, third-party payers to receive complete or partial payment for classes and/or birth coaching. At present there are perinatal education centers that are getting third-party reimbursement; they accomplished this by showing insurers evidence of the value of childbirth education in reduced costs of care and by offering to “certify” the knowledge of students in their classes (see Johnson et al., 2000).

WHAT HAVE WE GOT TO LOSE?

At a recent meeting of childbirth educators, midwives, and labor-and-delivery nurses in Denver, Colorado, many of the educators we spoke with expressed similar frustrations with their shrinking numbers, their loss of venue and clients, and the slowing of momentum in work that held such vitality in the past. Some spoke of the hospitals where they had taught for many years and of ending their affiliation to put their own hospital-designed classes in place. Others spoke of the need for a renewal of the birth-education movement. “It's not only better understanding what today's women want to know. It's about a new packaging, a new way of doing what we used to do in classes,” one educator said. “A new model would take change, and—oh, gosh—that can be hard.”

It's not only better understanding what today's women want to know. It's about a new packaging, a new way of doing what we used to do in classes.

If training for a new millenium is to come about, change is necessary, indeed—a change in the shape of our classes (location, duration); in our language (the modern woman's choices are influenced by a world that has dramatically changed since the 1960s); and in the scope of what we bring into our relationship with the women Lamaze International seeks to serve. Change would include broadening the scope of what we do and whom we affiliate with, professionally. Change would mean work, and it would mean growth.

We do not show respect for Elisabeth Bing's model if we stubbornly cling to it 40 years later, stuck in the mire of convention and unwilling to change and to re-envision the important work she began on our behalf a half century ago. Just as Bing tapped into the culture of her time, we are called to tap into the culture of a new century. In creating a fresh model of childbirth education, we not only honor our pioneers but also rediscover the wisdom in community and relationship that childbirth offers us, and we learn in new ways to walk the walk as well as to talk the talk as we journey alongside each other to create new possibilities for birthing families.

Footnotes

Elisabeth Bing, together with Marjorie Karmel, founded Lamaze International (then known as the “American Society for Psychoprophylaxis in Obstetrics” or “ASPO/Lamaze”) in 1960.

See De Vries, Wrede, van Teijlingen, and Benoit (2001) for several examples of differences in maternity care among the countries of North America and Europe.

A recent study (Matsuo, Shimoya, & Kimura, 2007) examines the relationship between maternal and fetal positioning, but the key independent variable is the mother's preferred position for sleep.

For the 2005 surgical birth statistic (30%), see Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2006, November). Births: Preliminary data for 2005. Health e-stats. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved August 29, 2007, from (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/prelimbirths05/prelimbirths05.htm#ref01

Lamaze members can view the entire report of the Listening to Mothers II survey by logging in to the Lamaze Web site (www.lamaze.org). Others can purchase the full report from the Childbirth Connection Web site (www.childbirthconnection.org), where the Executive Summary of the report is also available to the public.

Lamaze members can view the entire report of the Listening to Mothers II survey by logging in to the Lamaze Web site (www.lamaze.org). Others can purchase the full report from the Childbirth Connection Web site (www.childbirthconnection.org), where the Executive Summary of the report is also available to the public.

LCCE educator survey, 2/27/2007. Unpublished, Lamaze International, Washington, DC.

See the “Birthing Naturally” Web site at http://www.birthingnaturally.net/directory/cbe/organization.html (retrieved August 29, 2007)

For more information on the Lamaze Institute for Normal Birth and on Lamaze International's updated Six Care Practices That Support Normal Birth, log on to the Lamaze Web site (www.lamaze.org).

For more information on the Lamaze Institute for Normal Birth and on Lamaze International's updated Six Care Practices That Support Normal Birth, log on to the Lamaze Web site (www.lamaze.org).

See pages 25–37 of this journal issue for Morton and Hsu's (2007) ethnographic study of childbirth education, describing the dilemmas that American childbirth educators face.

See pages 25–37 of this journal issue for Morton and Hsu's (2007) ethnographic study of childbirth education, describing the dilemmas that American childbirth educators face.

Learn more about The Center for the Childbearing Year in Ann Arbor, Michigan, by logging on to its Web site (www.center4cby.com).

Learn more about The Center for the Childbearing Year in Ann Arbor, Michigan, by logging on to its Web site (www.center4cby.com).

See De Vries (2005, pp. 74–76) for a more complete description of the training and work of a kraamverzorgster.

REFERENCES

- Center for the Childbearing Year [CCBY] 2006. Our mission. Retrieved October 17, 2007, from http://center4cby.com/content/view/29/46. [Google Scholar]

- Declercq E. R, Sakala C, Corry M. P, Applebaum S. Listening to mothers II: Report of the second national U.S. survey of women's childbearing experiences. 2006 New York: Childbirth Connection. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries R. 1989. Care givers in pregnancy and childbirth. In I. Chalmers, M. Enkin, & M. J. N. C. Keirse (Eds.), Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth (pp. 144–161). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- De Vries R. A pleasing birth: Midwifery and maternity care in the Netherlands. 2005 Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries R, Wrede S, van Teijlingen E, Benoit C. Birth by design: Pregnancy, maternity care, and midwifery in North America and Europe. 2001 Eds. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J. R, Kershaw T. S, Westdahl C, Magriples U, Massey Z, Reynolds H. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;110:330–339. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. R. B, Zettelmaier M. A, Warner P. A, Hayashi R. H, Avni M, Luke B. A competency based approach to comprehensive pregnancy care. Women's Health Issues. 2000;10(5):240–247. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(00)00058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamaze International. n.d.). Lamaze philosophy: Mission and vision statements Retrieved August 28, 2007, from http://www.lamaze.org/Default.aspx?tabid=105.

- Lamaze International. The six care practices that support normal birth. [Entire issue] Journal of Perinatal Education. 2007;16(3) doi: 10.1624/105812407X217084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Shimoya K, Ushioda N, Kimura T. Maternal positioning and fetal positioning in utero. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2007;33(3):279–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkin D. (2007, May 6). Reinventing middle age. New York Times Magazine pp. 21–22.

- Morton C. H, Hsu C. Contemporary dilemmas in American childbirth education: Findings from a comparative ethnographic study. Journal of Perinatal Education. 2007;16(4):25–37. doi: 10.1624/105812407X245614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pel M, Heres M. H, Hart A. A, van der Veen F, Treffers P. E. Provider-associated factors in obstetric interventions. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1995;61(2):129–134. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02129-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson K. R, Atterbury J. Trends and issues in labor induction in the United States: Implications for clinical practice. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2003;32(6):767–779. doi: 10.1177/0884217503258528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton J, Scott P. 1996. Understanding and teaching optimal foetal positioning Tauranga. New Zealand: Birth Concepts. [Google Scholar]