Abstract

Dysregulation of calcium signaling has been causally implicated in brain aging and Alzheimer's disease. Mutations in the presenilin genes (PS1, PS2), the leading cause of autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer's disease (FAD), cause highly specific alterations in intracellular calcium signaling pathways that may contribute to the neurodegenerative and pathological lesions of the disease. To elucidate the cellular mechanisms underlying these disturbances, we studied calcium signaling in fibroblasts isolated from mutant PS1 knockin mice. Mutant PS1 knockin cells exhibited a marked potentiation in the amplitude of calcium transients evoked by agonist stimulation. These cells also showed significant impairments in capacitative calcium entry (CCE, also known as store-operated calcium entry), an important cellular signaling pathway wherein depletion of intracellular calcium stores triggers influx of extracellular calcium into the cytosol. Notably, deficits in CCE were evident after agonist stimulation, but not if intracellular calcium stores were completely depleted with thapsigargin. Treatment with ionomycin and thapsigargin revealed that calcium levels within the ER were significantly increased in mutant PS1 knockin cells. Collectively, our findings suggest that the overfilling of calcium stores represents the fundamental cellular defect underlying the alterations in calcium signaling conferred by presenilin mutations.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, endoplasmic reticulum, phosphoinositide signaling, store-operated calcium channel, store-operated calcium entry

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the leading cause of age-related dementia (Selkoe 1999). Certain familial forms of AD (FAD) are characterized by an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern and a tragically early age of onset, and most of these have been linked to mutations in the two presenilin genes (PS1, PS2). The PS1 and PS2 genes encode highly conserved, polytopic integral membrane proteins that are widely expressed not only within the central nervous system (Cribbs et al. 1996), but also in many peripheral tissues (Sherrington et al. 1995). Intracellularly, in both neural and nonneuronal cells, the presenilins are localized predominantly to the ER (Cook et al. 1996).

The precise mechanisms by which presenilin mutations lead to AD neurodegeneration are currently unresolved. It is well established that presenilin mutations lead to increased production of the longer species of β-amyloid (Aβ) from the Aβ precursor protein (APP; Scheuner et al. 1996). APP mismetabolism, however, need not represent the exclusive or most primary consequence of presenilin mutations. It remains possible that other pathological effects of presenilin mutations upstream of and/or independent of Aβ generation may also contribute to the molecular and cellular changes characterizing AD neurodegeneration.

Mounting evidence has established that presenilin mutations confer highly specific alterations in intracellular calcium signaling pathways. For instance, a potentiation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3)-mediated calcium signals has been documented in an array of experimental systems expressing PS1 mutations, ranging from Xenopus oocytes to transgenic animals (Guo et al. 1996, Guo et al. 1998, Guo et al. 1999; Begley et al. 1999; Leissring et al. 1999a,Leissring et al. 1999b). Similar alterations have also been observed in studies of human fibroblasts harboring FAD mutations (Ito et al. 1994; Gibson et al. 1996; Etcheberrigaray et al. 1998). The calcium signaling changes in FAD fibroblasts are highly selective and specific for the disease, being present in affected individuals, but not in unaffected family members (Etcheberrigaray et al. 1998). Moreover, mutations in PS2 produce alterations in calcium signaling indistinguishable from PS1 mutations (Leissring et al. 1999a,Leissring et al. 1999b), providing further support that these changes represent a common pathogenic feature of all FAD-linked presenilin mutations.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the dysregulation of calcium signaling conferred by presenilin mutations plays a causal role in the pathogenesis of FAD, underlying both the neuronal degeneration and the hallmark pathological features of the disease. For instance, elevated levels of cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]i) in cultured cells can modulate the processing of APP and thereby increase Aβ production (Querfurth and Selkoe 1994). This underscores the likelihood that calcium dysregulation is at least one cause of increased Aβ production, and thus possibly contributes to plaque formation. Furthermore, increased [Ca2+]i has also been shown to increase hyperphosphorylation of tau (Mattson et al. 1991). Finally, altered calcium homeostasis is centrally involved in the increased susceptibility to cell death conferred by PS1 mutations (Guo et al. 1996, Guo et al. 1998, Guo et al. 1999; Mattson et al. 2000).

Despite the likely involvement of calcium disturbances in the pathogenesis of FAD, very little is known about the precise cellular mechanisms by which presenilin mutations alter calcium signaling pathways. To address this issue, we studied calcium signaling in fibroblasts from homozygous mutant PS1 knockin (KI) mice. In these genetically altered mice, the endogenous mouse PS1 gene has been replaced by the human counterpart containing the FAD-linked mutation, PS1M146V (Guo et al. 1999). This model possesses many advantages over other experimental paradigms, since the mutant human PS1 protein is expressed to physiological levels, and the endogenous tissue and cellular expression pattern is maintained. Hence, concerns about protein overexpression artifacts, ectopic expression, or confounding influences of the wild-type protein are obviated. Here, we demonstrate that agonist-evoked calcium signals are markedly potentiated in the PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts. In addition, we report the novel finding that PS1M146V-KI cells show deficits in capacitative calcium entry (CCE), i.e., the influx of extracellular calcium triggered by depletion of intracellular calcium stores. Finally, we provide evidence that both of these alterations are attributable to an abnormal elevation of ER calcium stores in the mutant cells. Thus, these findings provide a novel cellular mechanism to account for the calcium signaling alterations conferred by presenilin mutations, which could lead to the development of novel therapeutics for presenilin-associated FAD.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

The derivation and characterization of the PS1M146V-KI mice has been described elsewhere (Guo et al. 1999). To isolate fibroblasts, snips of tail from neonatal homozygous PS1M146V-KI animals and controls were washed with 70% ethanol, minced in CMF (Ca2+- and Mg2+-free HBSS), and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 2.5 ml of TCH solution (0.125% trypsin, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mg/ml collagenase Type V (Sigma Chemical Co.) in HBSS. After quenching the reaction by addition of DME supplemented with 20% FBS, the supernatant was removed and spun at 225 g for 5 min, and the pelleted cells were resuspended in DME/20% FBS. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For calcium imaging experiments, P1-P4 cultures were plated onto glass-bottomed 6-cm petri dishes (MatTek Corp.) and grown to near confluency. 1–2 h before imaging, cells were loaded for 45 min at room temperature with 5 μM Fura 2-AM supplemented with pluronic acid F-127 (Molecular Probes) in Hepes-buffered control solution (HCSS) containing 120 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 15 mM glucose, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.3, and 0.5% phenol red (calcium-deficient HCSS contained 1 mM EGTA and no CaCl2). Cells were washed three times with HCSS and allowed to incubate for at least 30 min before imaging. All reagents were purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. unless otherwise noted.

Calcium Imaging

Measurements of [Ca2+]i were obtained using the InCyt Im2™ Ratio Imaging System (Intracellular Imaging Inc.) using excitation at 340 and 380 nm. The system was calibrated using stock solutions containing either no calcium (0 calcium plus 1 mM EGTA) or a saturating level of calcium (1 mM) using the formula [Ca2+]i = K d(225) [(R−Rmin)/(Rmax−R)] (Fo/Fs). Drugs were added by superfusion via a peristaltic pump and removed by vacuum. All experiments were performed using fibroblasts harvested from at least three different animals (n = 5–28 cells per experiment). Quantitative data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Potentiation of Agonist-evoked Calcium Signals in Mutant PS1 Knockin Cells

We studied calcium signals in fibroblasts isolated from neonatal mutant PS1 KI mice and controls using the cytosolic calcium indicator Fura-2 AM. To activate the phosphoinositide/calcium signaling cascade, cells were stimulated with the cell surface receptor agonists, bradykinin (BK; Fig. 1) or bombesin (data not shown). In control fibroblasts, BK stimulation evoked calcium signals with two characteristic phases: a transient rise in [Ca2+]i lasting seconds, followed by a sustained phase of elevated [Ca2+]i lasting several minutes (Fig. 1 a).

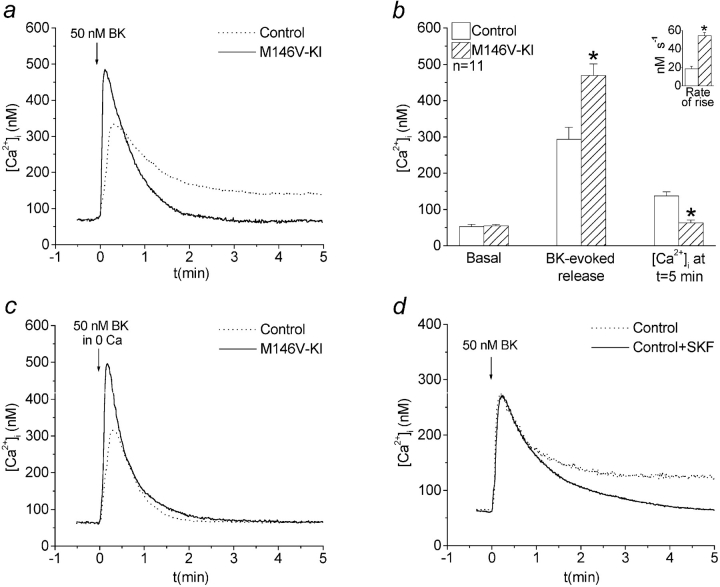

Figure 1.

Agonist-evoked calcium signals are altered in PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts: evidence for impaired capacitative calcium entry. a, Typical traces showing calcium signals induced by 50 nM BK. b, Quantitative data from n = 11 experiments showing mean basal [Ca2+]i, peak BK-evoked [Ca2+]i, and [Ca2+]i 5 min after agonist stimulation. Cytosolic calcium signals in control cells contain two phases: a transient rise in [Ca2+]i followed by a sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i lasting many minutes. Note the absence of the sustained phase in the PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts. The inset shows quantitative data for the rates of rise of the initial calcium transients. c, Representative calcium signals evoked by 50 nM BK in calcium-deficient medium. Note that control cells lack the sustained phase of elevated [Ca2+]i seen when extracellular calcium is present, whereas PS1M146V-KI are relatively unchanged (see a). d, Typical BK-evoked calcium signals in control cells incubated in calcium-containing medium with or without SFK-96365 (10 μM). Note that SKF-96365 reduces the sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i normally seen in control cells. *P < 0.01.

Calcium signals in PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts differed from controls in several salient respects. First, the rate of rise of the calcium signal was significantly increased (Fig. 1, a and b, inset). Second, the peak of the transient phase was significantly potentiated (Fig. 1, a and b). Finally, the sustained phase of elevated [Ca2+]i present in control cells was virtually absent in the mutant fibroblasts (Fig. 1, a and b).

Impaired Capacitative Calcium Entry in Mutant PS1 Knockin Cells

The sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i in control cells resembles CCE, in which depletion of ER calcium stores triggers the influx of extracellular calcium through store-operated calcium channels (SOCCs; Lewis 1999). To determine whether the sustained phase resulted from calcium influx, we stimulated cells with BK in calcium-deficient medium. Removal of extracellular calcium abolished the sustained phase in control cells, but had little effect on the calcium signal in PS1M146V-KI cells, indicating that the sustained phase of elevated [Ca2+]i in control cells reflects calcium influx (compare Fig. 1, a and c). Notably, the initial calcium transients in both control and PS1M146V-KI cells, which reflect calcium release from intracellular stores, were relatively unaffected by removal of extracellular calcium (compare Fig. 1, a and c). Therefore, the potentiation of the initial calcium transient seen in PS1M146V-KI cells is attributable to increased release of calcium from intracellular stores rather than calcium influx.

To determine if the sustained calcium phase reflected CCE, we treated control cells with SKF-96365, an agent known to block CCE through SOCCs (Merritt et al. 1990). As illustrated in Fig. 1 d, SKF-96365 treatment eliminated the sustained phase of [Ca2+]i in control cells stimulated with BK in calcium-containing medium. Collectively, these data indicate that the sustained phase of elevated [Ca2+]i in control cells is CCE, and that CCE is disrupted in cells harboring a mutation in PS1.

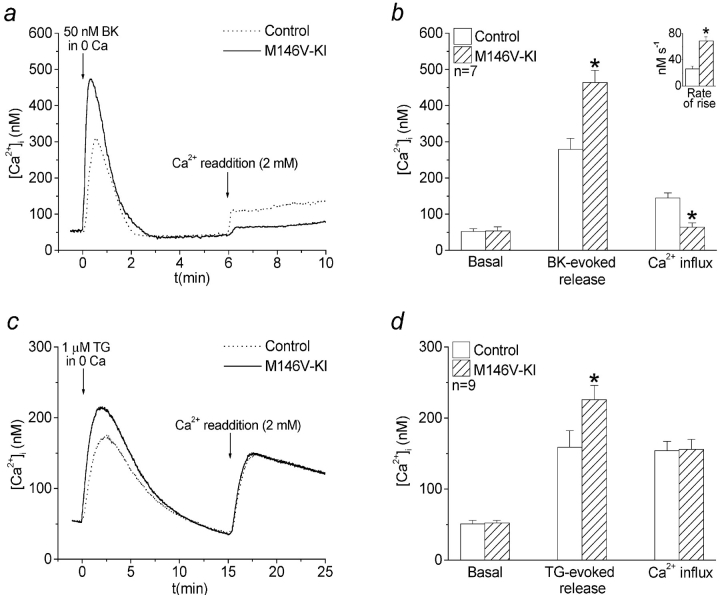

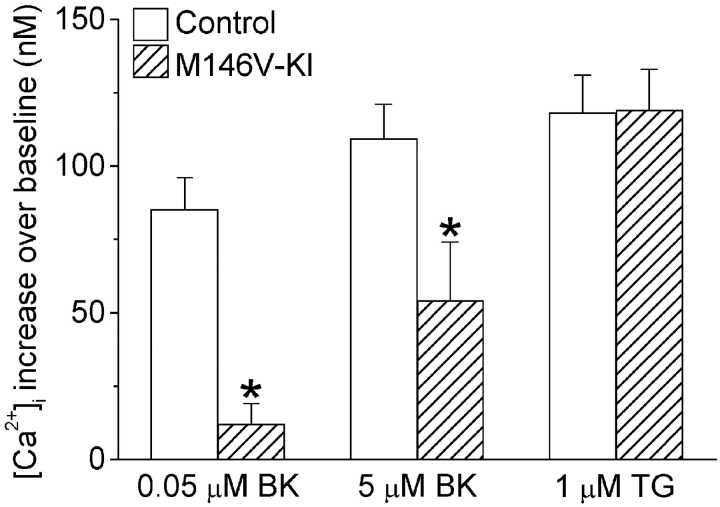

To quantify the magnitude of CCE after agonist stimulation, cells were initially stimulated with BK in calcium-deficient medium. Subsequently, after the initial calcium transients had returned to baseline, the calcium-deficient medium was replaced with medium containing 2 mM calcium (Fig. 2 a). Relative to controls, the magnitude of CCE upon calcium readdition was significantly reduced in PS1M146V-KI cells after stimulation with 50 nM BK (Fig. 2, a and b). Intriguingly, in similar experiments using higher concentrations of BK (5 μM), the deficits in CCE in PS1M146V-KI cells, though still present, were significantly attenuated (see Fig. 3). Furthermore, no differences in CCE were observed after complete depletion of calcium stores with thapsigargin (TG; Fig. 2c and Fig. d, and Fig. 3). Thus, as illustrated in Fig. 3, the magnitude of the deficits in CCE in PS1M146V-KI cells varied according to the degree and type of stimulation, with weak agonist stimulation eliciting the greatest deficits and complete store depletion eliciting no deficits whatsoever.

Figure 2.

Capacitative calcium entry is impaired in PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts after weak agonist stimulation, but not complete depletion of calcium stores. a, Representative calcium signals evoked by addition of 50 nM BK in calcium deficient medium, followed by the readdition of 2 mM extracellular calcium. b, Quantitative data from n = 7 experiments showing basal [Ca2+]i, peak BK-evoked [Ca2+]i, and peak [Ca2+]i 30 s after readdition of extracellular calcium. The inset shows quantitative data for the rates of rise of the initial calcium transients. c, Representative calcium signals after the addition of 1 μM TG in calcium-deficient medium, followed by the readdition of 2 mM extracellular calcium. d, Quantitative data from n = 9 experiments showing basal [Ca2+]i, peak TG-evoked [Ca2+]i, and peak [Ca2+]i after readdition of extracellular calcium. *P < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Comparison of capacitative calcium entry evoked by weak or strong agonist stimulation or TG treatment. Data are shown for experiments using the protocol illustrated in Fig. 2, in which cells were stimulated with either 0.05 μM BK, 5 μM BK, or 1 μM TG. Note that the data are expressed as the increase in [Ca2+]i relative to [Ca2+]i 30 s before readdition of extracellular calcium. *P < 0.01.

Elevated Calcium-Store Content in Mutant PS1 Knockin Mice

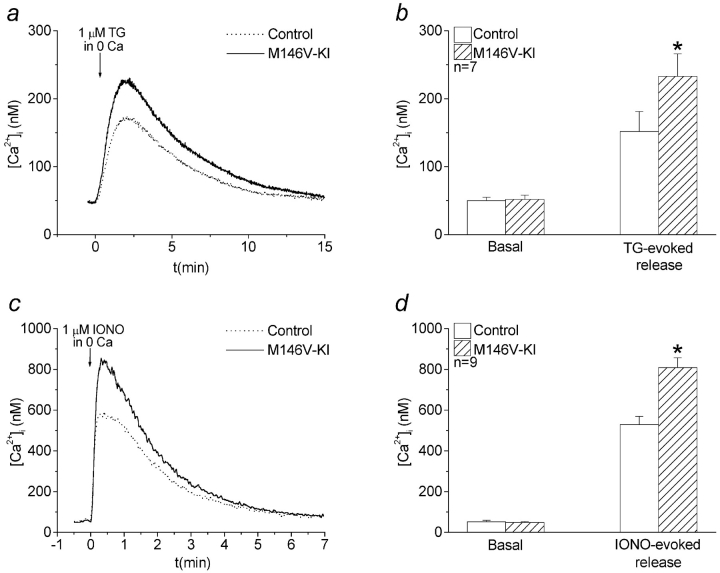

The preceding results suggested that the PS1M146V-KI cells possess functional SOCCs, but are impaired in their ability to trigger CCE when weakly stimulated. Since the trigger for CCE is the depletion of intracellular calcium stores, we hypothesized that CCE is impaired in PS1M146V-KI cells because their ER calcium levels are abnormally elevated. On this view, weak agonist stimulation, which elicits only a transient release of ER calcium through rapidly inactivating InsP3 receptors (Parekh et al. 1997), fails to deplete stores in the PS1M146V-KI cells to the threshold required for CCE activation (see Fig. 5). To test this idea, the intracellular calcium stores of resting cells were released by treatment with TG or ionomycin in the nominal absence of extracellular calcium (Fig. 4). The TG-releasable calcium pool was significantly larger in PS1M146V-KI relative to controls, as indicated by increases in both the peak value of TG-evoked calcium transients (Fig. 4, a and b) and in their rate of rise (1.67 ± 0.12 nM s−1 versus 1.11 ± 0.11 nM s−1, respectively, P < 0.01). Similar results were obtained when cells were treated with the calcium ionophore ionomycin in calcium-deficient medium (Fig. 4c and Fig. d). These data indicate that intracellular calcium stores, including the ER, are increased in cells from PS1M146V-KI mice. Collectively, our results suggest that the potentiation of calcium transients and absence of CCE observed in mutant PS1M146V-KI cells are attributable to increased ER calcium levels.

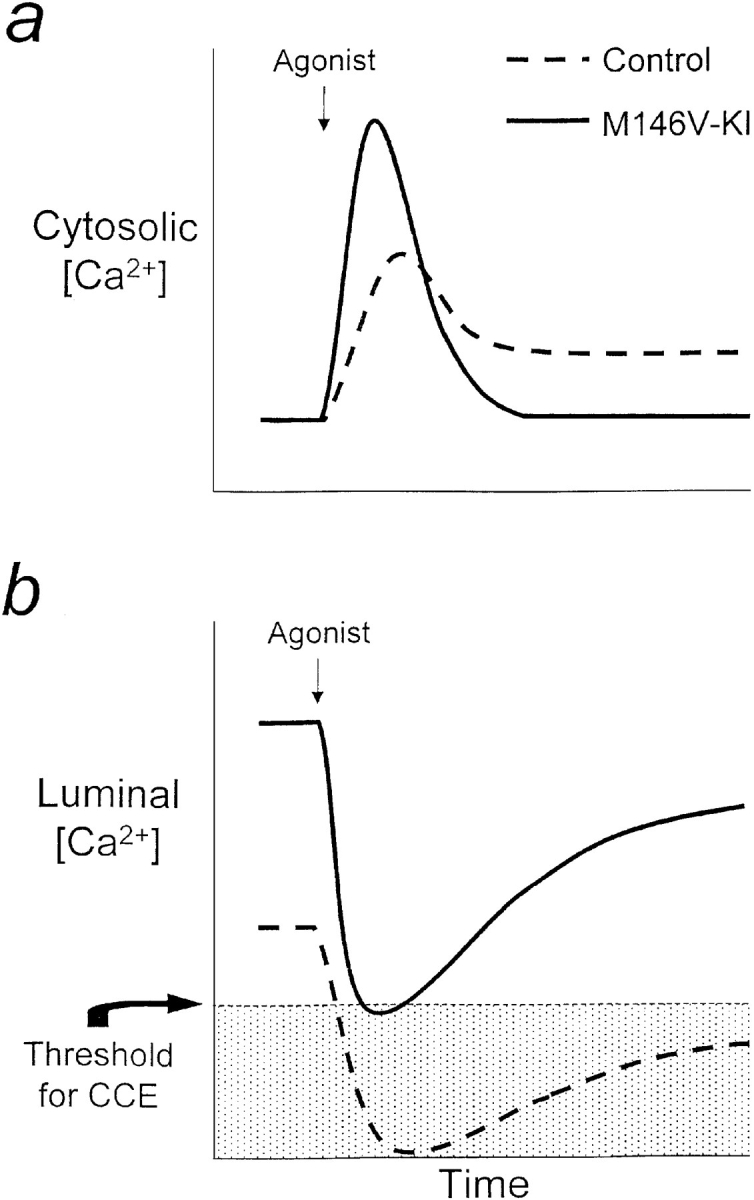

Figure 5.

Model of the perturbations in calcium signaling in PS1M146V-KI mice. a, Schematic diagram illustrating changes in cytosolic calcium signals after weak agonist stimulation. b, Similar diagram showing calcium levels within the lumen of the ER. After weak agonist stimulation, luminal calcium levels in control cells fall well below the threshold level required for activation of CCE. In contrast, weak agonist stimulation barely triggers CCE in PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts because luminal calcium levels are abnormally elevated.

Figure 4.

Intracellular calcium-store content is elevated in PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts. a, Typical calcium signals evoked by 1 μM TG in calcium-deficient medium. b, Quantitative data for n = 7 experiments showing basal [Ca2+]i and peak [Ca2+]i induced by TG treatment. c, Typical calcium signals evoked by 1 μM ionomycin (IONO) in calcium-deficient medium. d, Quantitative data for n = 9 experiments showing basal [Ca2+]i and peak [Ca2+]i evoked by ionomycin treatment. *P < 0.01.

Discussion

In this study we investigated calcium signaling in fibroblasts from KI mice harboring a PS1 mutation linked to FAD. Relative to controls, cytosolic calcium signals from PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts exhibited a significant potentiation in calcium released by agonist activation of the phosphoinositide signaling pathway. In addition, KI cells exhibited deficits in CCE evoked by agonist stimulation, but not by complete depletion of ER calcium stores. We conclude that both of these alterations are attributable to the elevation of ER calcium content in PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts.

The agonist-evoked calcium signals in PS1M146V-KI fibroblasts are virtually indistinguishable from comparable experiments with human fibroblasts from FAD patients harboring PS1 mutations (compare our Fig. 1 a to Figure 1 a in Ito et al. 1994). Thus, the PS1M146V-KI animals faithfully mimic the calcium signaling changes seen in presenilin-associated FAD. Importantly, since the mutant PS1 protein is expressed to physiological levels in these animals (Guo et al. 1999), none of the observed changes is attributable to protein overexpression.

It is notable that, unlike human FAD fibroblasts, the cells in this study were isolated from neonatal animals. This suggests that the changes in calcium signaling in FAD fibroblasts do not merely reflect secondary consequences of AD pathogenesis, such as the accumulation of mitochondrial mutations during the lifetime of the individual that have been shown to affect calcium signaling in cybrids transformed with mitochondria from nonfamilial AD patients (Sheehan et al. 1997). Rather, our findings support the hypothesis that altered calcium signaling is an early and chronic consequence of PS1 mutations, one that may play a causal role in the pathogenesis of FAD.

Although the present study was focused on fibroblasts, the potentiation of calcium transients has been described in neuronal cells from these same animals (Guo et al. 1999; Leissring, M.A., Y. Akbari, and F.M. LaFerla, manuscript in preparation). This strongly suggests that the alterations in calcium signaling observed in peripheral cells from FAD patients may be directly involved in FAD neurodegeneration and memory loss (Disterhoft et al. 1994; Mattson et al. 2000). This finding also supports the use of fibroblasts as a model to study the pathological alterations in calcium signaling associated with presenilin mutations.

Our results suggest that elevated ER calcium levels are a fundamental cellular defect underlying the alterations in calcium signaling conferred by presenilin mutations. As illustrated in Fig. 5, we postulate that the higher levels of ER calcium in PS1M146V-KI cells would impair CCE by preventing agonist stimulation from depleting intracellular calcium stores beyond the threshold level required to activate CCE. Moreover, this model provides a satisfactory cellular mechanism to account for several observations made in other experimental systems. First, elevated ER calcium levels, by increasing the driving force on calcium across the ER, would be expected to increase the amplitude of calcium release transients, as has been documented in many systems (Ito et al. 1994; Gibson et al. 1996; Guo et al. 1996, Guo et al. 1998; Etcheberrigaray et al. 1998; Leissring et al. 1999a,Leissring et al. 1999b). Second, an increased driving force on calcium would also increase the rate of ER calcium release (see Fig. 1 a) and would account for our observations in Xenopus oocytes that mutant PS1 increases both the rate of calcium efflux and the average quantal content of elementary calcium release events, the fundamental building blocks making up global calcium signals (Mattson et al. 2000; Leissring, M.A., F.M. LaFerla, N. Callamaras, and I. Parker, manuscript submitted for publication). Third, because ER calcium levels can modulate the activity of IP3 receptors (Missiaen et al. 1992), elevated calcium stores may also account for the increased sensitivity of cells expressing presenilin mutations to IP3 stimulation. Finally, an overfilling of calcium stores may also explain the interesting observation that long-term potentiation is altered in mutant PS1 transgenic animals (Parent et al. 1999; Mattson et al. 2000), raising the specter that calcium dysregulation may underlie the memory impairments characterizing AD (Disterhoft et al. 1994).

The mechanism by which PS1 mutations elevate intracellular calcium stores is not yet known. Intriguingly, however, FAD fibroblasts harboring PS1 mutations have elevated levels of acylphosphatase, an enzyme that modulates the activity of the ER calcium-ATPases responsible for loading the ER (Liguri et al. 1996). Thus, overactivation of ER calcium pumps may underlie the overfilling of calcium stores. Future research into the molecular mechanisms by which presenilin mutations increase ER calcium levels could uncover novel targets for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Luette Forrest and Ms. Tritia Yamasaki for superb technical assistance.

We are grateful for support from the National Institute for Aging (P50 AG16573) and the American Health Assistance Foundation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: Aβ, β-amyloid; AD, Alzheimer's disease; APP, β-amyloid precursor protein; BK, bradykinin; [Ca2+]i, cytosolic calcium; CCE, capacitative calcium entry; FAD, familial Alzheimer's disease; InsP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; KI, knockin; PS1, presenilin-1; PS2, presenilin-2; SOCC, store-operated calcium channel; TG, thapsigargin.

References

- Begley J.G., Duan W., Chan S., Duff K., Mattson M.P. Altered calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction in cortical synaptic compartments of presenilin-1 mutant mice. J. Neurochem. 1999;72:1030–1039. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D.G., Sung J.C., Golde T.E., Felsenstein K.M., Wojczyk B.S., Tanzi R.E., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M., Doms R.W. Expression and analysis of presenilin 1 in a human neuronal systemlocalization in cell bodies and dendrites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9223–9228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs D.H., Chen L.S., Bende S.M., LaFerla F.M. Widespread neuronal expression of the presenilin-1 early-onset Alzheimer's disease gene in the murine brain. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;148:1797–1806. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disterhoft J.F., Moyer J.R., Jr., Thompson L.T. The calcium rationale in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Evidence from an animal model of normal aging. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1994;747:382–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etcheberrigaray R., Hirashima N., Nee L., Prince J., Govoni S., Racchi M., Tanzi R.E., Alkon D.L. Calcium responses in fibroblasts from asymptomatic members of Alzheimer's disease families. Neurobiol. Dis. 1998;5:37–45. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G.E., Zhang H., Toral-Barza L., Szolosi S., Tofel-Grehl B. Calcium stores in cultured fibroblasts and their changes with Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1316:71–77. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(96)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Furukawa K., Sopher B.L., Pham D.G., Xie J., Robinson N., Martin G.M., Mattson M.P. Alzheimer's PS-1 mutation perturbs calcium homeostasis and sensitizes PC12 cells to death induced by amyloid beta-peptide. Neuroreport. 1996;8:379–383. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Christakos S., Robinson N., Mattson M.P. Calbindin D28k blocks the proapoptotic actions of mutant presenilin 1reduced oxidative stress and preserved mitochondrial function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3227–3232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Fu W., Sopher B.L., Miller M.W., Ware C.B., Martin G.M., Mattson M.P. Increased vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to excitotoxic necrosis in presenilin-1 mutant knock-in mice. Nat. Med. 1999;5:101–106. doi: 10.1038/4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito E., Oka K., Etcheberrigaray R., Nelson T.J., McPhie D.L., Tofel-Grehl B., Gibson G.E., Alkon D.L. Internal Ca2+ mobilization is altered in fibroblasts from patients with Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:534–538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leissring M.A., Parker I., LaFerla F.M. Presenilin-2 mutations modulate amplitude and kinetics of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated calcium signals J. Biol. Chem 274 1999. 32535 32538a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leissring M.A., Paul B.A., Parker I., Cotman C.W., LaFerla F.M. Alzheimer's presenilin-1 mutation potentiates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated calcium signaling in Xenopus oocytes J. Neurochem 72 1999. 1061 1068b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R.S. Store-operated calcium channels. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1999;33:279–307. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(99)80014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liguri G., Cecchi C., Latorraca S., Pieri A., Sorbi S., Degl'Innocenti D., Ramponi G. Alteration of acylphosphatase levels in familial Alzheimer's disease fibroblasts with presenilin gene mutations. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;210:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M.P., Engle M.G., Rychlik B. Effects of elevated intracellular calcium levels on the cytoskeleton and tau in cultured human cortical neurons. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1991;15:117–142. doi: 10.1007/BF03159951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M.P., LaFerla F.M., Chan S.L., Leissring M.A., Shepel P.N., Geiger J.D. Calcium signaling in the ERits role in neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:222–229. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt J.E., Armstrong W.P., Benham C.D., Hallam T.J., Jacob R., Jaxa-Chamiec A., Leigh B.K., McCarthy S.A., Moores K.E., Rink T.J. SK&F 96365, a novel inhibitor of receptor-mediated calcium entry. Biochem. J. 1990;271:515–522. doi: 10.1042/bj2710515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L., De Smedt H., Droogmans G., Casteels R. Ca2+ release induced by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate is a steady-state phenomenon controlled by luminal Ca2+ in permeabilized cells. Nature. 1992;357:599–602. doi: 10.1038/357599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh A.B., Fleig A., Penner R. The store-operated calcium current I (CRAC)nonlinear activation by InsP3 and dissociation from calcium release. Cell. 1997;89:973–980. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent A., Linden D.J., Sisodia S.S., Borchelt D.R. Synaptic transmission and hippocampal long-term potentiation in transgenic mice expressing FAD-linked presenilin 1. Neurobiol. Dis. 1999;6:56–62. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querfurth H.W., Selkoe D.J. Calcium ionophore increases amyloid beta peptide production by cultured cells. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4550–4561. doi: 10.1021/bi00181a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D., Eckman C., Jensen M., Song X., Citron M., Suzuki N., Bird T.D., Hardy J., Hutton M., Kukull W. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D.J. Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1999;399:A23–A31. doi: 10.1038/399a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan J.P., Swerdlow R.H., Miller S.W., Davis R.E., Parks J.K., Parker W.D., Tuttle J.B. Calcium homeostasis and reactive oxygen species production in cells transformed by mitochondria from individuals with sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:4612–4622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04612.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington R., Rogaev E.I., Liang Y., Rogaeva E.A., Levesque G., Ikeda M., Chi H., Lin C., Li G., Holman K. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1995;375:754–760. doi: 10.1038/375754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]