Abstract

Bioactive gibberellins (GAs) are phytohormones that regulate growth and development throughout the life cycle of plants. DELLA proteins are conserved growth repressors that modulate all aspects of GA responses. These GA-signaling repressors are nuclear localized and likely function as transcriptional regulators. Recent studies demonstrated that GA, upon binding to its receptor, derepresses its signaling pathway by binding directly to DELLA proteins and targeting them for rapid degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Therefore, elucidating the signaling events immediately downstream of DELLA is key to our understanding of how GA controls plant development. Two sets of microarray studies followed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis allowed us to identify 14 early GA-responsive genes that are also early DELLA-responsive in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Chromatin immunoprecipitation provided evidence for in vivo association of DELLA with promoters of eight of these putative DELLA target genes. Expression of all 14 genes was downregulated by GA and upregulated by DELLA. Our study reveals that DELLA proteins play two important roles in GA signaling: (1) they help establish GA homeostasis by direct feedback regulation on the expression of GA biosynthetic and GA receptor genes, and (2) they promote the expression of downstream negative components that are putative transcription factors/regulators or ubiquitin E2/E3 enzymes. In addition, one of the putative DELLA targets, XERICO, promotes accumulation of abscisic acid (ABA) that antagonizes GA effects. Therefore, DELLA may restrict GA-promoted processes by modulating both GA and ABA pathways.

INTRODUCTION

Bioactive gibberellins (GAs) control a wide range of processes during plant development, including seed germination, leaf expansion, stem and root elongation, flowering time, and flower and fruit development (Davies, 2004; Fleet and Sun, 2005; Swain and Singh, 2005). Genetic and molecular studies have identified the GA receptors and several positive and negative components in the GA signaling cascade (Sun and Gubler, 2004; Hartweck and Olszewski, 2006). Among them, three major players are the GA receptors, the DELLA repressor proteins, and the F-box proteins that control the stability of DELLA proteins. Elegant work by Ueguchi-Tanaka et al. (2005) demonstrated that GA-INSENSITIVE DWARF1 (GID1) is a soluble GA receptor in rice (Oryza sativa). Subsequently, the GID1 homologs (GID1a, GID1b, and GID1c) in Arabidopsis thaliana were identified (Nakajima et al., 2006). Null mutations in the single GID1 gene in rice or in all three genes in Arabidopsis lead to an extremely dwarf and GA-insensitive plant (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2005; Griffiths et al., 2006; Willige et al., 2007).

The DELLA proteins are conserved repressors of GA signaling that act immediately downstream of the GA receptor to modulate all aspects of GA-induced growth and development in plants (Thomas and Sun, 2004; Griffiths et al., 2006; Nakajima et al., 2006). Recent studies further suggest that DELLA proteins may also restrict plant growth by integrating signals from other hormone pathways and environmental cues (Achard et al., 2003, 2006; Fu and Harberd, 2003). There are five members of the DELLA gene family in Arabidopsis: REPRESSOR OF ga1-3 (RGA), GA-INSENSITIVE (GAI), RGA-LIKE1 (RGL1), RGL2, and RGL3. Characterization of mutant combinations of null alleles in each DELLA gene demonstrates the overlapping and distinct functions of these genes in plant development. GA-induced vegetative growth and floral initiation are repressed by RGA and GAI (Dill and Sun, 2001; King et al., 2001). GA-promoted seed germination is mainly regulated by RGL2, although the remaining DELLA genes also play a minor role (Lee et al., 2002; Wen and Chang, 2002; Tyler et al., 2004; Cao et al., 2005; Tyler, 2006). In addition, RGA, RGL1, and RGL2 are involved in flower and fruit development (Cheng et al., 2004; Tyler et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004). Structurally, DELLAs are a subgroup of proteins that belong to the GRAS (for GAI, RGA, SCARECROW) family of transcriptional regulators and share a conserved C-terminal GRAS domain (Pysh et al., 1999; Bolle, 2004). DELLA proteins are named after a conserved motif at their N termini, absent in other GRAS members (Silverstone et al., 1998; Peng et al., 1999; Pysh et al., 1999). All DELLA proteins also contain a polymeric Ser and Thr region that may include sites of phosphorylation or glycosylation, Leu heptad repeats that may mediate protein–protein interactions, and putative nuclear localization signals. DELLA-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion proteins are nuclear localized when expressed in transgenic plants (Silverstone et al., 2001; Gubler et al., 2002; Itoh et al., 2002). Although DELLAs do not have a clearly identified DNA binding domain, they may act as coactivators or repressors by interacting with other transcription factors. In support of this idea, two other GRAS proteins, SHORT-ROOT (SHR) and SCARECROW (SCR) have been shown recently to be associated with the promoter sequences of their target genes in vivo (Levesque et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2007).

Recent studies demonstrated that DELLA proteins are rapidly degraded in response to GA treatment and their N-terminal DELLA domain plays a vital regulatory role in DELLA protein stability (Sun and Gubler, 2004). Deletion or specific amino acid substitutions within the conserved DELLA motif (e.g. gai-1 and rga-Δ17 in Arabidopsis) stabilize mutant DELLA proteins and confer GA-insensitive dwarf phenotypes (Peng et al., 1997; Dill et al., 2001; Gubler et al., 2002; Itoh et al., 2002).

The F-box proteins SLEEPY1 (SLY1) in Arabidopsis and GID2 in rice are part of the SCFSLY1 and SCFGID2 E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes, respectively (McGinnis et al., 2003; Sasaki et al., 2003). Both sly1 and gid2 mutants display GA-unresponsive dwarf phenotypes and accumulate extremely high levels of DELLA proteins. Yeast two-hybrid and pull-down assays showed that both SLY1 and GID2 interact directly with DELLA proteins, indicating that SLY1 and GID2 recruit DELLA proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome (Sasaki et al., 2003; Dill et al., 2004; Fu et al., 2004; Gomi et al., 2004). With the recent discovery of the GA receptor, the mechanism involved in GA-induced DELLA proteolysis has been elucidated further. It appears that GA promotes interaction of its receptor GID1 with the DELLA proteins via their DELLA domains (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2005; Griffiths et al., 2006; Nakajima et al., 2006, Willige et al., 2007). This in turn may cause a conformational change in the DELLA protein that facilitates the F-box protein recognition (Griffiths et al., 2006), resulting in rapid degradation of DELLA through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Mutant studies also identified SPINDLY (SPY) as another GA signaling repressor in Arabidopsis (Jacobsen and Olszewski, 1993). SPY and its homologs in other species share high sequence similarity to the O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferases (OGTs) in mammals (Thornton et al., 1999; Roos and Hanover, 2000). The animal OGTs modify target proteins by glycosylation of Ser/Thr residues, which either interfere or compete with kinases for phosphorylation sites (Wells et al., 2001). The recombinant SPY protein exhibits OGT activity in vitro (Thornton et al., 1999), and like animal OGTs, SPY is localized to the cytoplasm and nucleus (Swain et al., 2002). Target proteins of SPY have not been identified, but potential candidates include the DELLA proteins (Olszewski et al., 2002; Shimada et al., 2006; Silverstone et al., 2007).

Further downstream in the GA signaling pathway, the transcription factor GAMYB induces transcription of α-amylase genes in the barley (Hordeum vulgare) aleurone (Gubler et al., 1995, 1999). GAMYB acts downstream of DELLA, although it is unlikely a direct target of DELLA because of a 1-h lag time between GA-dependent DELLA protein degradation and GAMYB mRNA induction (Gubler et al., 2002). Mutant and transgenic studies in barley, rice, and Arabidopsis indicate that GAMYB also modulates GA-regulated floral development (Murray et al., 2003; Kaneko et al., 2004; Millar and Gubler, 2005). Moreover, one of the Arabidopsis GAMYBs (MYB33) is likely to play a role in GA-mediated floral induction by activating expression of LEAFY (Blazquez and Weigel, 2000; Gocal et al., 2001; Millar and Gubler, 2005). In Arabidopsis, GA also induces trichome initiation by activating GLABROUS1, another MYB gene (Perazza et al., 1998).

Although the earliest events of GA signaling, from GA perception to DELLA degradation, are now better understood, the gene regulatory network directly downstream of DELLA is unclear. Several microarray experiments have examined the effects of GA and DELLA proteins on gene expression in germinating seeds, seedlings, and flowers in Arabidopsis (Ogawa et al., 2003; Cao et al., 2006; Nemhauser et al., 2006). These experiments have taken advantage of mutants with defects in the GA biosynthetic pathway and/or in DELLA genes. The null mutant ga1-3 is severely GA deficient because GA1 encodes ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase, which catalyzes the first committed step in GA biosynthesis (Sun and Kamiya, 1994). This mutant is an extreme dwarf and has delayed flowering and male sterility (Koornneef and van der Veen, 1980; Wilson et al., 1992). These defects can be completely rescued by exogenous application of GA. The work by Ogawa et al. (2003) identified GA-regulated genes during germination by analyzing ga1-3 seeds after GA treatment for 3 to 12 h. GA-induced genes include those that are involved in cell wall metabolism (for cell elongation) and cell division. Genes that function in other plant hormone pathways were also modulated by GA (Ogawa et al., 2003). Cao et al. (2006) monitored differential gene expression in imbibed seeds and developing flowers of the wild type, ga1-3, and a quintuple null mutant ga1 rga gai rgl1 rgl2. Their study uncovered a large number of GA-regulated genes, ∼50% of which were also DELLA dependent (Cao et al., 2006). However, this analysis could not distinguish early DELLA targets from those that are located further downstream in the GA response pathway. Nemhauser et al. (2006) compared the initial responses of Arabidopsis seedlings to GA and six additional plant hormones by analyzing publicly available microarray data from the AtGenExpress consortium (http://www.arabidopsis.org/servlets/TairObject?type=expression_set&id=1007966175). Interestingly, within a 3-h treatment period, genes involved in each hormone signaling pathway are largely specific, although each hormone appears to alter expression of other hormone metabolism genes (Nemhauser et al., 2006).

Because DELLA proteins play a central role in modulating GA responses in plants, elucidating the molecular events immediately downstream of DELLA should shed light on how GA controls plant development. In this study, we identified early GA-responsive genes and specifically those directly controlled by DELLA proteins in shoots of Arabidopsis seedlings by microarray analysis. Our results indicate that DELLA proteins participate in two aspects of the GA signaling network: they help establish GA homeostasis by feedback regulating the expression of GA biosynthetic genes and GA receptors, and they promote the expression of downstream regulatory proteins that are putative negative components in GA signaling. In addition, DELLA may mediate interaction between GA and ABA pathways by upregulating expression of a putative E3 ligase gene, XERICO, which in turn promotes ABA accumulation.

RESULTS

DELLA proteins are conserved GA signaling repressors that act immediately downstream of the GA receptors (GID1) and play a pivotal role in modulating all aspects of GA responses (Thomas and Sun, 2004; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2005). These growth repressors may function as transcriptional regulators, although their direct targets have not been identified. To uncover early GA-responsive genes and those controlled by DELLA, we carried out two sets of microarray experiments. The first set aimed to identify early GA-regulated genes by analyzing the global gene expression profile in the GA-deficient mutant ga1-3 in the presence or absence of GA treatment; the second set aimed to uncover DELLA-regulated genes by induced expression of a dominant DELLA mutant protein (rga-Δ17) using a glucocorticoid (dexamethasone [DEX])-inducible system. All microarray data were generated using shoots of 8-d-old seedlings. The next two sections describe our initial experiments for determining the optimal GA treatment time point and for generating the reagents for the DEX-inducible rga-Δ17 system.

Early GA Responses Were Observed within Minutes of GA Treatment

In the wild-type background, responses to exogenous GA may be attenuated because of preexisting levels of endogenous GA. To maximize changes in gene expression between water versus GA treatment, the severely GA-deficient mutant ga1-3 was used. To determine the appropriate time point(s) of GA treatment for the microarray experiments, we first examined the rate of RGA protein disappearance and changes in transcript levels of two known GA-downregulated genes (GA3ox1 and GA20ox2) (Chiang et al., 1995; Phillips et al., 1995). In the ga1-3 mutant, RGA was rapidly degraded upon addition of 2 μM GA4 (Figure 1A). After 5 min of GA treatment, the amount of RGA was reduced to ∼50%. At 10 min, ∼90% of the RGA protein disappeared, and by 30 min it was no longer detectable (Figure 1A; see Supplemental Figure 1A online). GA3ox and GA20ox enzymes catalyze the last and penultimate steps for the synthesis of bioactive GAs in Arabidopsis, respectively (Hedden and Phillips, 2000). Transcript levels of GA3ox1 and GA20ox2 were shown to be under feedback regulation by GA treatment and by activity in the GA response pathway (Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Sun and Gubler, 2004). In the ga1-3 mutant, the amounts of GA3ox1 and GA20ox2 transcripts rapidly declined upon GA application, and changes were noticeable as early as 15 min after hormone treatment (Figure 1B). Our results showed that GA-induced RGA degradation precedes GA downregulation of GA3ox1 and GA20ox2 mRNA levels. Based on these results, we decided to perform microarray analysis using the ga1-3 samples that were treated with 2 μM GA4 or water for 1 h.

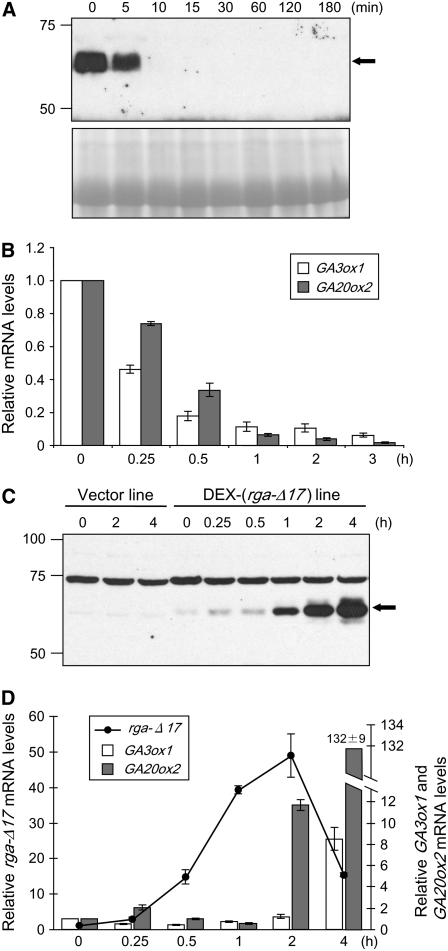

Figure 1.

Characterization of Arabidopsis Lines Used for Microarray Experiments.

(A) GA treatment triggers rapid degradation of endogenous RGA. Eight-day-old ga1-3 seedlings were treated with 2 μM GA4 for 0 to 3 h. Proteins extracted from shoots were analyzed by immunoblotting using affinity-purified anti-RGA antibody. Ponceau staining was used to confirm equal loading. Arrow indicates the position of RGA. The amounts of RGA remaining after 5- to 30-min treatments were estimated by serial dilutions as shown in Supplemental Figure 1A online.

(B) GA application causes a decrease in mRNA levels of GA biosynthetic genes. Seedlings were grown and treated as in (A) except that total RNA was isolated at the indicated time points. Transcript levels were determined by qRT-PCR, and the level at time 0 h was set to 1.0. Bars indicate the average transcript level ± se of four replications from two independent experiments.

(C) DEX treatment strongly induces the accumulation of rga-Δ17 in a DEX-inducible rga-Δ17 line. Eight-day-old seedlings were pretreated for 16 h with 2 μM GA4 followed by treatment for 0 to 4 h with either 2 μM GA4 only or in combination with 10 μM DEX. Shoot proteins were extracted and analyzed by immunoblotting using crude anti-RGA antibody. The 75-kD nonspecific band serves as evidence for equal loading. Arrow indicates the position of rga-Δ17.

(D) DEX treatment caused rapid accumulation of rga-Δ17 transcript, which precedes induction of GA3ox1 and GA20ox2. Seedlings were pretreated and treated as in (C). Total RNA from shoots was collected at the indicated time points. Transcript levels were determined by qRT-PCR, and the level at time 0 h was set to 1.0. Bars are the means ± se of three replicates. In (B) and (D), the housekeeping gene GAPC, whose expression is not responsive to GA (Dill et al., 2004), was used to normalize different samples.

An Inducible rga-Δ17 Protein Accumulated to High Levels and Caused Altered Expression of GA-Regulated Genes

Among the five DELLA proteins in Arabidopsis, RGA and GAI are the major regulators of GA-mediated vegetative growth (Dill and Sun, 2001; King et al., 2001). To identify direct targets of DELLA proteins in vegetative phase, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis carrying an inducible rga-Δ17 transgene using the DEX-mediated transcriptional induction system (Aoyama and Chua, 1997). The rga-Δ17 protein, which contains a DELLA motif deletion, is resistant to GA-induced degradation and therefore confers an extreme dwarf phenotype when expressed using the RGA promoter (Dill et al., 2001). The use of the DEX-inducible system allowed us to generate transgenic plants that grew normally in the absence of DEX treatment. The rga-Δ17–inducible construct contains a chimeric transcription factor (GVG), which is constitutively expressed under the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV35S) and six copies of the GAL4 upstream activating sequence fused to the rga-Δ17 coding sequence. GVG consists of the DNA binding domain of the yeast transcription factor GAL4, the transactivating domain of the herpes viral protein VP16, and the hormone binding domain of the rat glucocorticoid receptor. In plant cells, GVG exists as a cytoplasmic complex with the 90-kD heat shock protein (HSP90). Application of DEX results in dissociation of the GVG-HSP90 complex and rapid movement of GVG into the nucleus, where it activates transcription of the 6xUAS-driven transgene (rga-Δ17 in our experiment).

We identified multiple homozygous transgenic lines that contain the vector (control) or the DEX-inducible rga-Δ17 construct [DEX-(rga-Δ17)] in the T3 generation. For the DEX-(rga-Δ17) lines, we then screened for those that had low basal levels of transgene expression and demonstrated rapid and high induction levels of the rga-Δ17 transcript and protein following DEX treatment. We also analyzed GVG transcript levels in the vector control and the DEX-(rga-Δ17) lines and identified those with similar levels of GVG expression to minimize artifacts due to differential GVG levels (Kang et al., 1999). To determine the appropriate time points for microarray experiments, a DEX induction time course was carried out. Eight-day-old seedlings, pretreated for 16 h with 2 μM GA4 to saturate the GA responses in the plants, were then treated with 10 μM DEX plus 2 μM GA4 or only GA. Application of DEX caused rapid accumulation of rga-Δ17 protein in the DEX-(rga-Δ17) line but not in a vector control line (Figure 1C). By 1 h of DEX treatment, the rga-Δ17 protein was readily detectable and it continued to accumulate for up to 4 h, reaching ∼16 times the level of RGA protein present in ga1-3 (see Supplemental Figure 1B online). Although a small amount of rga-Δ17 protein was detected in the DEX-(rga-Δ17) line before DEX treatment (time 0 h; Figure 1C), this transgenic line did not show any growth defects without DEX induction (data not shown). Transcript levels of GA3ox1 and GA20ox2 were also determined. Accumulation of GA3ox1 transcript was only observed after 4 h of DEX induction. However, for GA20ox2, a >11-fold increase was observed after 2 h. By 4 h, the levels of GA20ox2 mRNA were >100-fold higher than those in the uninduced sample. It is worth noting that induction of both GA biosynthetic genes was preceded by accumulation of the rga-Δ17 transcript and protein (Figures 1C and 1D). In addition, the transcript levels of GA3ox1 and GA20ox2 were not induced in the vector control line (see Supplemental Figure 2A online). Based on these results, the 2- and 4-h time points were selected for microarray experiments.

Identification of Early GA-Responsive and DELLA Target Genes by Microarray Analysis

Using the conditions defined in the previous two sections, we produced two sets of data using Affymetrix ATH1 GeneChips: the first one allowed us to identify early GA-responsive genes, whereas the second one aimed to uncover early DELLA-responsive genes. Our assumption was that among the DELLA targets that function in the GA response pathway, DELLA-induced genes would be downregulated by GA treatment, and DELLA-repressed genes would be upregulated by GA.

Early GA-Responsive Gene Data Set

For the first data set, we used 8-d-old shoots of ga1-3 seedlings treated for 1 h with either water or 2 μM GA4. Four biological replicas were performed. The CEL files that contained the raw hybridization signal values of each microarray were analyzed using GeneSpring 7.2. The data were normalized using the GC-RMA (robust multiarray analysis with correction for GC content of the oligonucleotide) algorithm. The statistical analysis consisted of a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using a cutoff value of P ≤ 0.01 because a more stringent filtering procedure (e.g., false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.05; Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) did not recover any GA-responsive genes. The resulting list included 81 genes (see Supplemental Table 1 online). When a 2 fold change (FC) in gene expression was used to filter our gene list, only 20 genes were recovered, all of them downregulated. When the threshold was lowered to 1.5 FC, 42 genes were obtained, 33 of them being downregulated and nine upregulated by GA. Our final list of 67 GA-responsive genes contained all genes that had at least 1.2 FC with respect to the water-treated control (Table 1). Among these, 45 were downregulated by GA and 22 induced. As expected, the two GA biosynthetic genes, GA3ox1 and GA20ox2, were present in this list. Recently, several GA-related data sets using the ATH1 arrays have become available. One of them, generated by the AtGenExpress consortium (http://www.arabidopsis.org/servlets/TairObject?type=expression_set&id=1007966175), examined the GA response of Columbia (Col-0; wild type) and ga1-5 mutant seedlings growing in liquid culture for 7 d and treated with 1 μM GA3 for 0.5, 1, and 3 h. Another data set contains gene expression profiles of Landsberg erecta (Ler), ga1-3, and the ga1-3 rga gai rgl1 rgl2 quintuple mutant of germinating seeds and developing flowers (Cao et al., 2006). To compare our data with those generated by AtGenExpress, we downloaded the Affymetrix CEL files and analyzed them using the same procedure and cutoffs as our own data set (FC ≥ 1.2 and P ≤ 0.01). The wild-type and ga1-5 data sets were analyzed together, and a list of 173 genes was obtained (see Supplemental Table 2 online). When we compared this list with our ga1-3 list of 67 genes, only 14 genes overlapped (∼21%), all of them GA repressed (Table 1). Similarly, 28 to 32% of our ga1-3 list overlapped with GA-responsive genes in seeds and flowers, identified by Cao et al. (2006). The differences among these gene lists could be caused by genetic backgrounds (extreme GA-deficient ga1-3 versus the wild type and ga1-5 leaky mutant, Ler versus Col), growth conditions (agar plates versus liquid culture), tissues (shoots versus whole seedlings, seeds or flowers), or GA treatments (2 μM GA4 versus 1 μM GA3). In addition, after 1- to 3-h GA treatments, the changes in transcript levels for most GA-responsive genes were very subtle (with FC ≤ 2). Therefore expression of these genes would be extremely sensitive to experimental conditions. In fact, none of the GA-responsive genes in our ga1-3 list or in the AtGenExpress data set could pass a more stringent filtering method (Nemhauser et al., 2006; this work).

Table 1.

GA-Responsive Genes and Overlaps with Other Microarray Data Sets

|

Cao et al. (2006)

|

Nemhauser et al. (2006)a

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ga1-3 | DEX-(rgaΔ17)

|

AtGenExpress**

|

(Flowers)

|

(Seeds)

|

|||||||||||

| AGI Locus | Description | 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | 0.5 h | 1 h | 3 h | DELLA-Dep.b | DELLA-Ind.b | DELLA-Dep.b | DELLA Ind.b | 0.5 h | 1 h | 3 h | |

| 1 | At2g45900 | Expressed protein (Exp-PT1)* | −13.5 | 31.5 | 31.8 | −1.3 | −4.3 | −15.6 | + | + | |||||

| 2 | At1g15550 | GA3ox1* | −10.9 | 1.0 | 2.4 | −1.5 | −4.8 | −6.8 | + | + | −1.4 | −5.3 | −6.5 | ||

| 3 | At5g51810 | GA20ox2* | −10.6 | 4.3 | 45.4 | −1.4 | −5.3 | −10.7 | + | + | |||||

| 4 | At1g50420 | SCL3* | −6.8 | 4.0 | 6.4 | −1.4 | −2.8 | −3.4 | + | + | −1.7 | −2.6 | −5.2 | ||

| 5 | At4g19700 | RING-E3 HCa type (RING)* | −5.5 | 1.7 | 1.9 | −2.8 | −4.0 | −4.3 | + | + | −3.3 | −3.0 | −3.2 | ||

| 6 | At3g63010 | GID1b* | −5.1 | 2.9 | 4.3 | −1.5 | −2.6 | −2.5 | + | −1.8 | −2.5 | −3.3 | |||

| 7 | At3g05120 | GID1a* | −4.1 | 1.3 | 1.7 | −1.8 | −1.9 | + | + | ||||||

| 8 | At4g36410 | UBC17* | −4.1 | 12.8 | 17.0 | −1.2 | −2.0 | −3.9 | |||||||

| 9 | At2g04240 | XERICO* | −3.7 | 1.9 | 1.7 | −1.5 | −2.4 | −2.4 | + | + | −1.7 | −2.8 | −3.0 | ||

| 10 | At1g54120 | Expressed protein | −3.4 | −1.4 | −1.4 | + | |||||||||

| 11 | At1g56650 | MYB75 | −3.1 | + | |||||||||||

| 12 | At5g19340 | Expressed protein | −2.9 | −1.3 | −1.5 | ||||||||||

| 13 | At4g23060 | IQD22 | −2.8 | −1.3 | −1.9 | −2.0 | |||||||||

| 14 | At1g17830 | Expressed protein | −2.3 | + | + | ||||||||||

| 15 | At5g18840 | Sugar transporter, putative similar to ERD6 | −2.2 | + | |||||||||||

| 16 | At5g03670 | Expressed protein | −2.2 | −1.0 | −2.2 | −1.8 | |||||||||

| 17 | At1g29270 | Expressed protein | −2.2 | + | |||||||||||

| 18 | At3g30180 | BR6ox2 | −2.2 | ||||||||||||

| 19 | At1g68570 | H+-dependent oligopeptide transport family protein | −2.1 | + | |||||||||||

| 20 | At5g67480 | BT4 (BTB/TAZ domain protein 4)* | −2.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 | −1.2 | −1.6 | −1.9 | + | ||||||

| 21 | At5g47550 | Cys protease inhibitor, putative/cystatin | −2.0 | ||||||||||||

| 22 | At1g21250 | WAK1 (Wall-Associated Kinase1) | −1.9 | + | |||||||||||

| 23 | At5g05180 | Expressed protein | −1.9 | ||||||||||||

| 24 | At4g27730 | Oligopeptide transporter family protein | −1.8 | ||||||||||||

| 25 | At4g36220 | FAH1 (Ferulate-5-hydroxylase1) | −1.8 | + | + | ||||||||||

| 26 | At3g54320 | WRI1 (WRINKLED1) | −1.7 | ||||||||||||

| 27 | At2g41180 | SigA binding protein-related | −1.7 | + | |||||||||||

| 28 | At2g02080 | Zinc finger (C2H2 type) family protein | −1.7 | ||||||||||||

| 29 | At1g76990 | ACT domain–containing protein | −1.7 | −1.3 | −1.3 | + | |||||||||

| 30 | At1g80870 | Protein kinase family protein | −1.6 | ||||||||||||

| 31 | At3g61460 | BRH1 (BR-responsive RING-H2) | −1.6 | ||||||||||||

| 32 | At4g27300 | S-locus protein kinase, putative | −1.6 | + | |||||||||||

| 33 | At1g69160 | Expressed protein | −1.5 | ||||||||||||

| 34 | At3g47160 | Expressed protein | −1.5 | + | |||||||||||

| 35 | At3g19850 | Phototropic-responsive NPH3 family protein | −1.5 | ||||||||||||

| 36 | At3g02910 | Expressed protein | −1.5 | −1.5 | −1.6 | + | + | ||||||||

| 37 | At3g52870 | CaM binding family protein (CaM-BP)* | −1.5 | −1.8 | −1.6 | ||||||||||

| 38 | At3g11280 | MYB-like protein* | −1.4 | 2.4 | 2.6 | + | + | ||||||||

| 39 | At4g38580 | Copper chaperone-related | −1.4 | ||||||||||||

| 40 | At3g12670 | CTP-synthase/UTP-ammonia ligase, putative | −1.4 | ||||||||||||

| 41 | At4g31590 | Glycosyl transferase family 2 protein | −1.4 | ||||||||||||

| 42 | At2g34340 | Expressed protein (Exp-PT2)* | −1.4 | 1.3 | 3.7 | ||||||||||

| 43 | At2g31730 | bHLH154*,c | −1.4 | 2.0 | 2.0 | ||||||||||

| 44 | At4g39630 | Expressed protein | −1.3 | ||||||||||||

| 45 | At2g33310 | IAA13 | −1.3 | ||||||||||||

| 46 | At4g28220 | NADH dehydrogenase-related | 1.2 | ||||||||||||

| 47 | At5g23290 | c-MYC binding protein, putative/prefoldin | 1.2 | ||||||||||||

| 48 | At2g21185 | Expressed protein | 1.3 | ||||||||||||

| 49 | At1g55190 | Prenylated rab acceptor (PRA1) family protein | 1.3 | ||||||||||||

| 50 | At5g04420 | No apical meristem (NAM) family protein | 1.3 | ||||||||||||

| 51 | At5g05250 | Expressed protein | 1.3 | ||||||||||||

| 52 | At5g22310 | Expressed protein | 1.3 | ||||||||||||

| 53 | At5g12980 | RCD1-like cell differentiation protein, putative | 1.4 | ||||||||||||

| 54 | At1g14440 | Zinc finger homeobox family protein | 1.4 | + | |||||||||||

| 55 | At3g01470 | HB-1/HAT5 | 1.4 | ||||||||||||

| 56 | At5g60970 | TCP family transcription factor, putative | 1.4 | ||||||||||||

| 57 | At5g16590 | LRR transmembrane protein kinase, putative | 1.4 | ||||||||||||

| 58 | At3g07010 | Pectate lyase family protein | 1.5 | + | |||||||||||

| 59 | At2g38090 | MYB family transcription factor | 1.5 | + | |||||||||||

| 60 | At5g03555 | Permease, nucleotide, allantoin family protein | 1.6 | ||||||||||||

| 61 | At3g60520 | Expressed protein | 1.6 | ||||||||||||

| 62 | At4g30850 | Expressed protein | 1.6 | + | + | ||||||||||

| 63 | At5g08130 | bHLH046c | 1.6 | ||||||||||||

| 64 | At2g19310 | Expressed protein | 1.6 | ||||||||||||

| 65 | At1g54050 | 17.4-kD class III heat shock protein | 1.7 | ||||||||||||

| 66 | At2g41940 | Zinc finger (C2H2 type) family protein | 1.7 | ||||||||||||

| 67 | AT3g50750 | BZR1-like BR-signaling positive regulator-related | 1.9 | + | |||||||||||

Single asterisks indicate genes that overlap between the ga1-3 and DEX-(rga-Δ17) microarray data sets, which are also listed in Table 2. Double asterisks indicate raw data from the AtGenExpress consortium analyzed in this work. The + indicates that the gene was identified by Cao et al. (2006) as a GA-responsive gene (either DELLA-dep. or DELLA-ind.). AGI, Arabidopsis Genome Initiative.

AtGenExpress data analyzed by Nemhauser et al (2006).

DELLA-dep., DELLA-dependent genes; DELLA-ind., DELLA-independent or partially dependent genes.

Names according to Bailey et al. (2003).

Early DELLA-Responsive Gene Data Set

A second set of microarray data was generated using 8-d-old shoots of the DEX-(rga-Δ17) and vector control transgenic lines that were pretreated for 16 h with 2 μM GA4 and then exposed to 2 μM GA4 ± 10 μM DEX for 2 and 4 h. Three biological replicates were performed for the DEX-(rga-Δ17) line and two replicates for the vector control line at 4 h.

The array data were filtered through several rounds of analyses. The CEL files from the Affymetrix output were analyzed with GeneSpring 7.2 as described above. To identify DELLA-responsive genes after DEX treatment, a two-way ANOVA statistical analysis was performed to compare gene expression in the DEX-(rga-Δ17) line ± DEX (for 2 or 4 h). A list of 666 DELLA-responsive genes was generated when filtered by FDR ≤ 0.01 and FC ≥ 1.5. An FDR ≤ 0.01 indicates 1% or less false positives. This gene list was then filtered by subtracting genes whose expression was affected by DEX treatment in the vector control line at 4 h (see Supplemental Table 3 online) to exclude those genes mainly affected by the GVG transgene. Because the vector control line accumulated an approximately three fold higher GVG transcript than the DEX-(rga-Δ17) line (see Supplemental Figure 2B online), genes with a P ≤ 0.01 and a FC ≤ 3 in the vector line were eliminated from the DELLA-responsive gene list. In addition, the RGA gene was removed from this list. As a result, 475 genes were listed as putative RGA-regulated, 336 being upregulated and 139 downregulated (see Supplemental Table 4 online).

To identify putative DELLA target genes that function in the GA response pathway, we compared the two microarray data sets and found only 14 overlapping genes (Figure 2, Table 2). All overlapping genes, except for At3g52870, were induced by rga-Δ17 and repressed by GA based on the microarray data (Table 2), suggesting that the direct downstream targets of RGA are mainly repressors of GA signaling. Among these 14 overlapping genes, nine of them were also found to be affected by the DELLA protein mutations in flowers and three in seeds (Cao et al., 2006) (Table 1). In addition to these 14 genes, we found four more genes, bHLH137, LBD40, WRKY27, and IQD22, that exhibited upregulation in the DEX-(rga-Δ17) data set and GA downregulation in the ga1-3 experiment. However, the P values in the ga1-3 microarray data set for the first three genes were above 0.01. In the case of IQD22, its FC value in the vector control line was >3. Further quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis corroborated their GA and RGA responses in ga1-3 and in a transgenic line that expresses the rga-Δ17 gene under the control of the endogenous RGA promoter, PRGA:(rga-Δ17) (Dill et al., 2001), respectively (Table 2, Figure 3). These results indicated that these four additional genes are indeed early GA and RGA responsive. The transcript levels of gene At3g52870 did not exhibit GA or RGA responses by qRT-PCR (Table 2); therefore, it was removed from the putative DELLA target gene list.

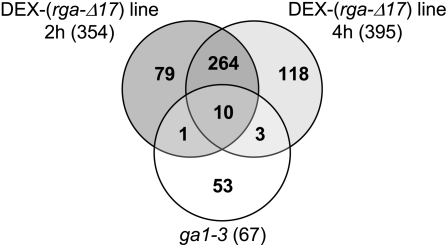

Figure 2.

Overlap between Microarray Data Sets of Early GA- and DELLA-Responsive Genes.

A total of 475 genes found to respond to rga-Δ17 at 2 and/or 4 h after DEX induction (FDR ≤ 0.01; FC ≥ 1.5) are shown in the upper circles. The 67 GA-responsive genes in ga1-3 after 1 h GA treatment (P ≤ 0.01; FC ≥ 1.2) are shown in the lower circle. Fourteen overlapping genes (listed in Table 2) were identified to be present in both GA- and DELLA-responsive gene lists.

Table 2.

Putative DELLA Targets

| Microarray Data

|

qRT-PCR Datab

|

ChIP-qPCRc

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGI Locusa | Descriptiona | DEX-(rga-Δ17) 2 h DEX 4 h DEX | ga1-3 1 h GA | ga1-3 1 h GA | ga1-3 3 h GA | PRGA:(rga-Δ17)d | Fold Enrichment | P Valuee | ||

| 1 | At5g51810 | GA20ox2 | 4.3 | 45.4 | −10.6 | −4.4 ± 0.3 | −23.5 ± 3.5 | 6.5 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.521 |

| 2 | At1g15550 | GA3ox1 | 1.0 | 2.4 | −10.9 | −7.1 ± 0.6 | −18.0 ± 3.6 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.287 |

| 3 | At3g05120 | AtGID1a | 1.3 | 1.7 | −4.2 | −2.1 ± 0.4 | −2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 0.043 |

| 4 | At3g63010 | AtGID1b | 2.9 | 4.3 | −5.1 | −2.9 ± 0.2 | −2.5 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 0.019 |

| 5 | At3g11280 | MYB | 2.4 | 2.6 | −1.4 | −1.3 ± 0.0 | −2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.0 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.002 |

| 6 | At5g50915 | bHLH137fg | 4.7 | 10.0 | −1.6 | −1.4 ± 0.1 | −6.7 ± 1.8 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 0.087 |

| 7 | At2g31730 | bHLH154g | 2.0 | 2.0 | −1.4 | −1.3 ± 0.0 | −2.2 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 0.228 |

| 8 | At5g52830 | WRKY27f | 4.6 | 5.0 | −1.6 | −1.6 ± 0.1 | −1.4 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.058 |

| 9 | At1g50420 | SCL3 | 4.0 | 6.4 | −6.8 | −7.7 ± 0.4 | −8.2 ± 1.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | <0.0001 |

| 10 | At1g67100 | LBD40f | 3.1 | 6.9 | −2.2 | −2.2 ± 0.7 | −9.3 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.011 |

| 11 | At4g23060 | IQD22f | 3.9 | 2.6 | −2.8 | −3.0 ± 0.2 | −2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 0.152 |

| 12 | At5g67480 | BT4h | 1.7 | 1.4 | −2.0 | −2.2 ± 0.2 | −2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | ND | |

| 13 | At2g45900 | Exp-PT1 | 31.5 | 31.8 | −13.5 | −7.9 ± 1.3 | −10.8 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.243 |

| 14 | At2g34340 | Exp-PT2h | 1.3 | 3.7 | −1.4 | −1.7 ± 0.2 | −2.2 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | ND | |

| 15 | At4g36410 | UBC17h | 12.8 | 17.0 | −4.1 | −1.8 ± 0.1 | −4.1 ± 0.7 | −1.4 ± 0.0 | ND | |

| 16 | At2g04240 | XERICO | 1.9 | 1.7 | −3.7 | −2.4 ± 0.3 | −3.0 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.080 |

| 17 | At4g19700 | RING | 1.7 | 1.9 | −5.5 | −2.4 ± 0.4 | −2.8 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.262 |

| 18 | At3g52870 | CaM-BPi | −1.8 | −1.6 | −1.5 | −1.1 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.0 | ND | |

The genes in boldface are responsive to both GA and DELLA, determined by microarray and qRT-PCR analyses.

Average values of three repeats ± se.

Means of three independent ChIP-qPCR ± se. ND, not determined.

FC between the Ler/PRGA:(rga-Δ17) transgenic line and wild-type Ler.

A t test analysis was performed using the statistical package SAS 9.1.3.

Genes that do not overlap between the ga1-3 and the DEX-(rga-Δ17) microarray data sets but that were rescued after further testing by qRT-PCR (see text).

Name according to Bailey et al. (2003).

GA-responsive genes with weak response to DELLA, measured by qRT-PCR.

This gene is considered a false positive because its expression, when measured by qRT-PCR, was not responsive to GA or DELLA.

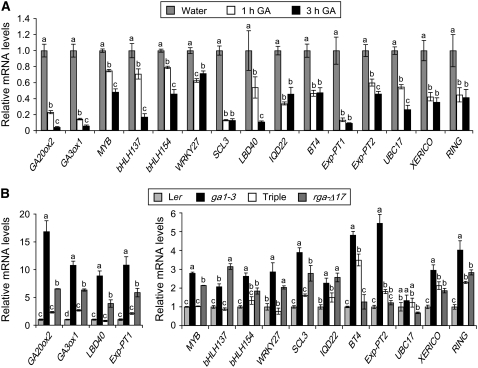

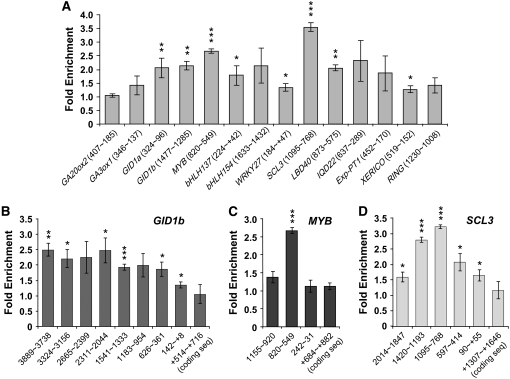

Figure 3.

Regulation of Transcript Levels of Putative RGA Target Genes by GA and DELLA.

(A) GA treatment downregulates mRNA levels of putative RGA targets in ga1-3. The means of three replicates of quantitative RT-PCR ± se are shown. Relative mRNA levels of individual genes after GA treatment were calculated in comparison to the water-treated control at each time point. Similar results were obtained when qRT-PCR was performed using two additional sets of biological replicates.

(B) Relative transcript levels of putative RGA target genes in the wild type, ga1-3, the triple homozygous mutant rga-24 gai-t6 ga1-3, and the transgenic line carrying PRGA:(rga-Δ17) (all lines are in the Ler background). The means of three replicates of qRT-PCR ± se are shown. The expression level in Ler was arbitrarily set to 1.0. Similar results were obtained when qRT-PCR was performed using a second set of samples.

In (A) and (B), the housekeeping gene GAPC, whose expression is not responsive to GA (Dill et al., 2004), was used to normalize different samples. One-way ANOVA was performed with least significant difference multiple comparison tests at an α level of 0.05 using SPSS version 11.5.0. When two samples show different letters (a to d) above the bars, the difference between them is significant (P < 0.05).

Among the early DELLA-induced genes, four of them encode either GA biosynthetic enzymes (GA20ox2 and GA3ox1) or GA receptors (GID1a and GID1b). Transcript levels of these genes are known to be reduced by GA treatment and by the loss-of-function DELLA mutations (Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Griffiths et al., 2006). Our microarray data suggested that DELLA proteins may directly regulate expression of these genes.

The physiological roles of the rest of the early DELLA-induced genes have not been reported previously. Three genes encode putative ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzyme (UBC17) or RING-type ubiquitin E3 ligases (XERICO and At4g19700), which may ubiquitinate and modify activity of downstream components (Conaway et al., 2002) or regulate their stability via the proteasome pathway (Kraft et al., 2005; Stone et al., 2005). At4g19700 will be referred to as RING in the rest of this article. Several DELLA-responsive genes are predicted to encode nuclear transcription factors (MYB, bHLH137, bHLH154, and WRKY27) or transcriptional regulators (SCL3, LBD40, IQD22, and BT4). MYB, bHLH, and WRKY proteins belong to large families of transcription factors that regulate a myriad of processes during plant growth and development (Kranz et al., 1998; Eulgem et al., 2000; Toledo-Ortiz et al., 2003). SCL3, like the DELLA proteins, belongs to the GRAS family of putative transcriptional regulators (Pysh et al., 1999). LBD is a member of the ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2/LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES domain (AS2/LBD) family (Iwakawa et al., 2002; Shuai et al., 2002). IQD22 belongs to the IQD (IQ domain) family of calmodulin (CaM) binding proteins (Abel et al., 2005), which contain putative nuclear localization signals and may mediate Ca2+ signaling to regulate gene expression in the nucleus (Levy et al., 2005). BT4 is a member of another family of nuclear Ca2+/CaM binding proteins, which contain a BTB/POZ domain at their N terminus and a zinc finger TAZ domain at the C terminus (Du and Poovaiah, 2004) and may function in transcriptional regulation (Kanai et al., 2000). At2g45900 and At2g34340, which will be referred to as Exp-PT1 and Exp-PT2, respectively, were annotated as expressed proteins and both are predicted to be localized to the nucleus (Nakai and Kanehisa, 1992; Heazlewood et al., 2005, 2007; Nair and Rost, 2005).

To corroborate our putative DELLA target gene list, we analyzed their transcript levels in GA time-course experiments and in DELLA mutant seedlings by qRT-PCR.

Putative RGA Targets Were GA and DELLA Responsive by qRT-PCR Analysis

We have previously shown, by qRT-PCR analysis, that the transcript levels of GA3ox1, GID1a, and GID1b are reduced by GA treatment and by the loss-of-function DELLA mutations (Griffiths et al., 2006). Similar results were also obtained in a microarray study that compared gene expression profiles in the wild type, ga1-3, and the rga gai rgl1 rgl2 ga1 quintuple mutant (Cao et al., 2006). These observations are consistent with our microarray data showing that these three genes may be direct targets of DELLA proteins. To verify our microarray results, we examined the transcript levels of the remaining 14 putative DELLA targets by qRT-PCR analysis. GA3ox1 was also included in the analysis as a control. Consistent with our ga1-3 microarray data, the transcript levels of all of these genes were downregulated by GA treatment (Figure 3A).

To confirm that these genes are DELLA responsive, we compared their transcript levels in Ler, ga1-3, the rga-24 gai-t6 ga1-3 triple null mutant, and the PRGA:(rga-Δ17) transgenic line by qRT-PCR. As expected, almost all (except UBC17) displayed elevated mRNA levels in ga1-3 compared with Ler (Figure 3B, Table 2). Consistent with the microarray data indicating that they are DELLA-induced genes, transcript levels of these genes, except BT4, Exp-PT2, and UBC17, were increased by rga-Δ17 (comparing Ler versus rga-Δ17). Moreover, their expression in the triple null mutant was lower than in ga1-3 but similar to that in Ler (Figure 3B). These results support the idea that these genes are immediate targets of both RGA and GAI. Interestingly, the mRNA levels of XERICO and RING in the triple mutant remained higher than in Ler, suggesting that additional DELLA proteins may be also involved in controlling GA signaling through these two genes.

Our qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that 14 of the 17 RGA putative targets listed in Table 2 are both GA and DELLA responsive. BT4, Exp-PT2, and UBC17 were clearly GA responsive, but their expression was not significantly affected in the PRGA:(rga-Δ17) transgenic line or in the rga gai ga1 background. Therefore, these genes were classified as only GA responsive but not DELLA responsive. In the rest of this article, we focus on the remaining 14 genes.

The putative DELLA targets may be coordinately regulated through common cis-elements in their promoters. Alternatively, different elements may be present in these genes if DELLA proteins interact with different transcription factors to regulate individual promoters. Promoter analysis of the 14 DELLA-responsive genes using the Web-based promoter analysis tool Athena (http://www.bioinformatics2.wsu.edu/cgi-bin/Athena/cgi/home.pl) (O'Connor et al., 2005) did not find any known transcription factor binding site to be significantly enriched. Using the MEME program (Bailey and Elkan, 1994; Bailey and Gribskov, 1998), a consensus sequence [C/T]T[C/T][C/A]TC[T/C][C/T]TCT[C/T][C/T]T[T/C] (named CCT element) with P < 7.2 × 10−6 was found to be present within 1 kb 5′ upstream from the transcription start site of all 14 DELLA-responsive genes. To test whether DELLA directly binds to the promoters of its targets and whether this CCT element plays an important role in DELLA binding, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments.

RGA Interacted with Target Promoters in Vivo

ChIP is a powerful technique to detect protein–DNA interactions in vivo (Orlando, 2000) and has been used effectively to verify putative direct target genes of transcription factors in Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2002; Wigge et al., 2005; Levesque et al., 2006). DELLA proteins do not have a bona fide DNA binding domain. However, other members of the GRAS superfamily, SHR and SCR, are capable of interacting with DNA by ChIP-qPCR assays (Levesque et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2007). We therefore employed this assay to test whether RGA directly interacts with the promoters of the early DELLA-induced genes identified by microarrays. To pull-down RGA protein efficiently from Arabidopsis, we generated transgenic lines that express a RGA fusion protein with a TAP (alternative tandem affinity purification) tag. The TAP tag sequence contains nine copies of the Myc epitope, six His residues, the cleavage site of the 3C protease, and two copies of IgG binding sequence (Rubio et al., 2005). This RGA-TAP fusion protein is responsive to GA-induced degradation (Figure 4A) and is functional in planta to rescue the rga-24 null allele defect (see Supplemental Figure 3 online). Using IgG-coated beads, RGA-TAP can be pulled down efficiently from chromatin preparations from RGA-TAP plants (Figure 4B). ChIP, followed by gene-specific real-time qPCR, was performed using chromatin from the control rga-24 ga1-3 and the rga-24 ga1-3 RGA-TAP transgenic line. For each putative RGA target promoter, qPCR primers were designed to amplify ∼250-bp sequences within the 1-kb 5′ upstream promoter region. Because the transcription start site has not been determined for all genes, we will refer to the position as bases upstream of the ATG. Whenever possible, the primer sets were designed to amplify promoter sequences containing at least one CCT element. The 18S rRNA gene was used to normalize the qPCR results in each ChIP sample. A 1.3- to 3.5-fold consistent enrichment was observed for promoter sequences of GID1a, GID1b, MYB, bHLH137, WRKY27, SCL3, LBD40, and XERICO in the RGA-TAP samples (Figure 5A, Table 2), supporting that these genes are RGA direct targets. The subtle enrichment observed so far may be because the PCR primers do not amplify the optimal RGA binding region of the promoter of the putative target genes. Alternatively, the RGA–DNA interaction may not be direct, but through other transcription factor(s), the cross-linking of RGA-TAP to DNA would be less efficient. The first possibility was tested by performing ChIP-qPCR using additional primer sets spanning different regions within the 5′ upstream sequences of GA3ox1 (4 kb), GA20ox2 (3 kb), GID1b (4 kb), MYB (1.2 kb), and SCL3 (2 kb). A primer set that amplified the coding region of each gene was also included in the qPCR analysis as an additional control. We observed up to a 2.5-, 2.7-, and 3.2-fold enrichment for GID1b, MYB, and SCL3, respectively (Figures 5B to 5D). However, no significant enrichment was obtained for GA3ox1 or GA20ox2 (see Supplemental Figure 4 online). The consistent but moderate enrichment of promoters of eight DELLA-responsive genes in these ChIP experiments suggest that RGA may be associated with its target promoters via interaction with additional DNA binding proteins. The CCT element alone seemed to be insufficient for RGA interaction because several promoter regions containing this element were not significantly enriched (e.g. Exp-PT1 [452∼170], GA3ox1 [428∼257], and GA20ox2 [201∼18]) (Figure 5; see Supplemental Figure 4 online). In addition, some promoter regions without the CCT element were enriched by ChIP with RGA-TAP (e.g. SCL3 [1095∼768] and GID1b [1477∼1285]). These observations suggest that the CCT element may not be required for RGA binding, consistent with the hypothesis that other transcription factors are involved and that, therefore, different elements may be needed for different DELLA target genes.

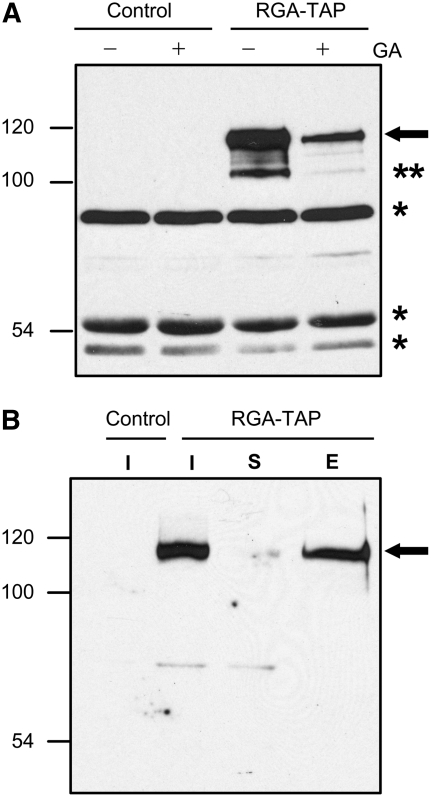

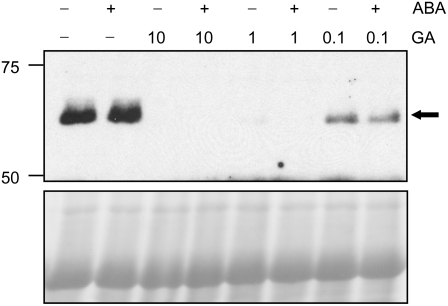

Figure 4.

GA-Induced Degradation and Efficient Immunoprecipitation of RGA-TAP.

(A) The RGA-TAP fusion protein is responsive to GA treatment. Total proteins were extracted from control (rga-24 ga1-3) and the RGA-TAP line (also in the rga-24 ga1-3 background) that were treated with water (–) or 2 μM GA4 (+) for 1 h.

(B) Immunoprecipitation of RGA-TAP from nuclear extracts with IgG-Sepharose beads. Isolated chromatin from control and RGA-TAP lines that were treated with 1% formaldehyde was incubated with IgG beads to pull down RGA-TAP. I, input (total protein extract before immunoprecipitation); S, supernatant after immunoprecipitation; E, eluate. Protein blots were probed with crude anti-RGA antibody. Arrows indicate the position of the RGA-TAP protein. Bands marked with ** and * are truncated RGA-TAP fusion protein and nonspecific cross-reacting proteins, respectively.

Figure 5.

RGA-TAP Binds the Promoters of Its Putative Direct Targets in Vivo.

(A) Chromatin preparations of the control line (rga-24 ga1-3) or the rga-24 ga1-3 RGA-TAP line were subjected to ChIP followed by qPCR. Fold enrichment of each promoter region in the RGA-TAP line was calculated by comparing to the control line. The numbers adjacent to the gene names indicate base pairs upstream of the ATG of each gene. A + indicates base pairs downstream of the ATG. The values for fold enrichment for most genes are the average ± se of at least two qPCR reactions from three independent ChIP experiments. The values for MYB, bHLH154, LBD40, and RING are the average of three qPCR reactions from one ChIP experiment.

(B) to (D) The promoters of GID1b, MYB, and SCL3 were scanned to identify sequences with maximal interaction with RGA-TAP. As an additional negative control, a coding region in each gene was also analyzed by qPCR. The numbers below each bar indicate the region amplified by qPCR as in (A).

In (A) to (D), t tests were performed using the statistical package SAS 9.1.3. ***, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.05; *, P < 0.1.

Ontology of Early GA-Responsive Transcripts

To further understand the early events in GA signaling that lead to eventual changes in overall plant growth and development, we classified our GA-responsive gene list by gene ontology (http://www.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/go/index.jsp and https://www.affymetrix.com/analysis/netaffx/go_analysis_netaffx4.affx). Out of the 67 genes that responded to GA treatment at 1 h, 45 were downregulated by GA, ranging from −1.3 to −13.5-fold. The rest (22 genes) displayed slight upregulation, between 1.2- and 1.9-fold. Forty-eight genes had an assigned molecular function, and the remaining 19 are novel (Table 3). Of the 35 genes with binding activity, 14 are predicted to bind nucleic acids. We found 15 genes (22%) in the “transcription regulator activity” category. These include previously uncharacterized transcription factors (MYB-like, bHLH, and zinc finger–containing proteins), as well as SCL3, ATHB-1/HAT5, IAA13, and WRINKLED1 (WRI1). ATHB-1, a GA-induced gene, encodes a homeodomain Leu zipper protein involved in leaf development (Aoyama et al., 1995). IAA13, a GA-repressed gene, is a repressor of auxin signaling involved in embryonic root development (Weijers et al., 2005). WRI1, a GA-repressed gene, encodes an AP2/EREB-type transcription factor (Cernac and Benning, 2004). WRI1 functions in lipid storage during late embryogenesis and regulates sugar metabolism in germinating seeds (Cernac and Benning, 2004; Cernac et al., 2006). The loss-of-function wri1 mutant is hypersensitive to abscisic acid (ABA) during germination.

Table 3.

Ontology of Early GA-Responsive Genes

| Total | Upa | Downa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Function | 48 | 15 | 33 | ||

| Catalytic | Total | 13 | 3 | 10 | |

| Transferase | 5 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Kinase | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Glycosylase | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Oxidoreductase | 5 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Lyase | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Ligase | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Binding | Total | 35 | 12 | 23 | |

| Nucleic acid | 14 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Ion | 16 | 4 | 12 | ||

| Nucleotide | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Protein | 10 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Tetrapyrrole | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Carbohydrate | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| CaM | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Amine | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Transcription factor/regulator | Total | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| MYB | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Zinc finger | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| bHLH | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Others | 6 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Transporter | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Enzyme inhibitor | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Cell elongation | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Signal transducer | Total | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Receptor | 5 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Hormone pathways | Total | 8 | 1 | 7 | |

| Biosynthesis | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| GA | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| ABA | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| BR | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Signaling | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| GA | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| BR | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Auxin | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Function not assigned | 19 | 7 | 12 |

Up, GA-upregulated genes at 1 h; down, GA-downregulated genes at 1h.

Besides IAA13 and WRI1, GA treatment appears to also affect several additional genes that are involved in other hormone pathways. XERICO, a GA-repressed gene, plays a role in regulating ABA accumulation (Ko et al., 2006). In addition, the BR6ox2 (Brassinosteroid-6-oxidase2) gene, which was downregulated by GA, encodes a cytochrome p450 enzyme (CYP85A2) that catalyzes the last step in brassinosteroid (BR) biosynthesis (Shimada et al., 2003; Nomura et al., 2005).

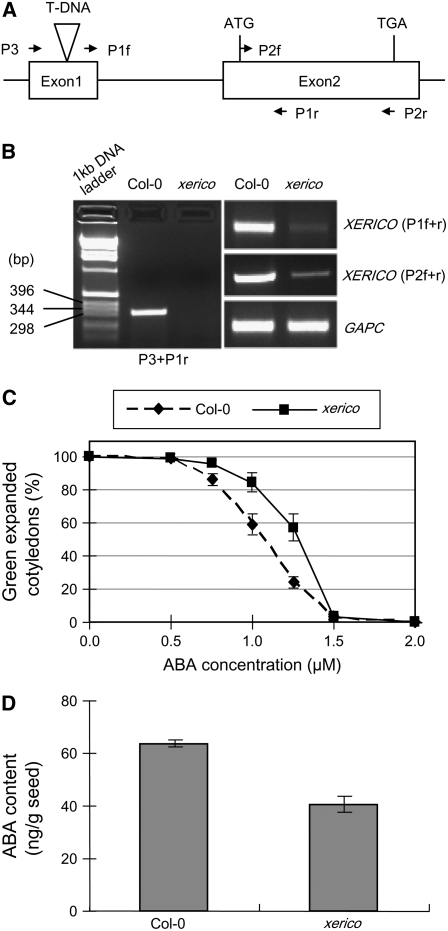

Characterization of the xerico Mutant and Interaction between GA and ABA Pathways

XERICO is one of the putative DELLA target genes, and its transcript levels were induced by DELLA and repressed by GA (Table 2, Figure 3). XERICO was named for the drought tolerance phenotype of overexpression of this gene using the CaMV35S promoter in Arabidopsis (Ko et al., 2006). This drought tolerance phenotype is accompanied by an elevated level of ABA in the plant and hypersensitivity to salt and ABA during seedling growth. These observations suggested that XERICO plays a role in ABA metabolism, presumably by upregulating ABA biosynthesis or by downregulating ABA catabolism. Our finding that XERICO is a putative DELLA target suggests that DELLA proteins may induce ABA accumulation by upregulating XERICO. However, in the previous study (Ko et al., 2006), no loss-of-function xerico mutant was included. To verify the physiological role of XERICO, we obtained a T-DNA insertion xerico mutant (SALK_075188), in which the T-DNA is inserted into the first exon that is 560-bp upstream from the start codon (Figure 6A). In the homozygous xerico mutant, no full-length WT XERICO transcript was detected by RT-PCR using primers (P3 and P1r) flanking the T-DNA insertion site (Figures 6A and 6B). Because the T-DNA is inserted into the 5′ untranslated region of this gene, we also tested whether any truncated transcripts downstream from the insertion site were present in this mutant. Two pairs of primers (P1f+P1r and P2f+P2r) downstream of the T-DNA insertion site were used for real-time qRT-PCR. In the xerico mutant, the gene-specific transcript is still detectable but at ∼10-fold lower level than in the wild-type Col-0 plants. Therefore, this xerico mutant is a leaky allele rather than a null allele.

Figure 6.

The T-DNA Insertion Site and ABA-Resistant Phenotype of the xerico Mutant.

(A) The genomic structure of XERICO is shown. The position of the T-DNA insertion is indicated by a triangle above the genomic structure. The locations and orientations of primers used to detect wild-type or truncated transcripts are also shown in this diagram.

(B) The wild-type or truncated transcripts of the XERICO gene in Col-0 (wild type) and the xerico mutant. qRT-PCR was performed using RNA isolated from the wild type and the homozygous xerico mutant using three sets of primers as labeled. Using P3 and P1r, the wild-type transcript was only detected in Col-0 but not in the xerico mutant (left panel). However, the mutant still accumulated truncated xerico transcripts (∼10% of wild-type amounts), which were detected using two pair of primers (P1f + P1r and P2f + P2r) that are downstream of the T-DNA insertion site. The agarose gel image shown contains the qRT-PCR products after 30 cycles of amplification.

(C) Seedling establishment of the xerico mutant is resistant to ABA. Seeds of Col-0 and the homozygous xerico mutant were incubated at 22°C for 7 d under continuous light, and seedlings with fully expanded green cotyledons were scored. Data represent means ± se of three replicates (100 seeds per treatment). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

(D) ABA contents are lower in the xerico mutant seeds than in Col-0. Data represent means ± se of three replicates. Similar results were obtained in an independent experiment. A t test indicated that the difference between means was highly significant (P < 0.01)

Because overexpression of XERICO leads to high ABA contents, the loss-of-function xerico allele might have lower amounts of endogenous ABA and be more resistant than the wild type to ABA treatment during seedling establishment. Indeed, we found that the xerico mutant was more resistant to exogenous ABA treatment (at 0.75 to 1.25 μM; Figure 6C). In addition, the seeds of this xerico mutant contained lower amounts of endogenous ABA than the wild type (Figure 6D). Although we only characterized one loss-of-function xerico allele, its phenotype is opposite to the XERICO overexpression line, suggesting that the ABA-deficient phenotype is caused by the xerico mutation and supporting the idea that XERICO plays a role in ABA metabolism.

GA and ABA play antagonistic roles, with GA promoting and ABA inhibiting seed germination, seedling growth, and flower initiation (Koornneef et al., 1991; Gazzarrini and McCourt, 2003; Razem et al., 2006). Our data suggest that one function of the DELLA proteins is to upregulate ABA accumulation by inducing XERICO expression.

ABA Inhibits GA Signaling Downstream of DELLA Proteins

Previous studies in cereal aleurone suggest that ABA inhibits GA responses by acting downstream of DELLA proteins (Gómez-Cadenas et al., 2001; Gubler et al., 2002; Zentella et al., 2002). The sln1a mutant of barley, which contains a recessive mutation in the DELLA gene SLN1, exhibits constitutive GA responses. In the aleurone of wild-type embryoless half seeds, expression of α-amylase genes requires the addition of GA, but in sln1a α-amylase, expression is constitutive. ABA treatment can effectively block α-amylase production in sln1a (Chandler, 1988; Lanahan and Ho, 1988), but it does not protect against GA-induced SLN1 degradation (Gubler et al., 2002). These observations indicate that ABA inhibits GA responses downstream of DELLA proteins. By contrast, by analyzing a GFP-RGA protein in transgenic Arabidopsis (Ler/PRGA:GFP-RGA), it was reported recently that 2-h 20 μM ABA pretreatment inhibited the GA (10 μM GA3)–induced degradation of this fusion protein (Achard et al., 2006). This discrepancy could be due to the differences in species and/or tissues, or endogenous versus fusion protein. To investigate the effect of ABA on the GA signaling pathway and specifically on DELLA protein stability, we monitored the levels of endogenous RGA in response to exogenous ABA and/or GA in the ga1-3 mutant. This mutant background was chosen to avoid the indirect effect of ABA on DELLA stability because ABA is known to have an inhibitory effect on GA biosynthesis (Seo et al., 2006; Oh et al., 2007).

Seedlings of ga1-3 were pretreated for 2 h with water or 20 μM ABA, followed by 1 h treatment with water, GA3 (10 μM), ABA (20 μM), or a combination of ABA and GA (as in Achard et al., 2006). Figure 7 shows that the endogenous RGA levels did not change when seedlings were treated with either water or ABA. By contrast, GA treatment, in the presence or absence of ABA, led to RGA degradation, similar to what was observed in barley aleurone by Gubler et al. (2002). We also found that RGA responded more rapidly to GA than the GFP-RGA fusion protein (Figure 7; see Supplemental Figure 5A online). Therefore, lower concentrations of GA were also tested in the ga1-3 mutant. However, ABA did not prevent RGA degradation even in the presence of 0.1 μM GA3 (Figure 7). To ensure that our ABA treatment was effective, we analyzed the transcript levels of RD29A, an ABA-responsive gene (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 1994), and found that the amount of RD29A mRNA was >200-fold higher in the ABA-treated sample than in the water control (see Supplemental Figure 5C online).

Figure 7.

ABA Inhibits GA Signaling Downstream of RGA.

Five-day-old ga1-3 seedlings were pretreated with water or 20 μM ABA for 2 h, followed by treatment with the indicated concentration (μM) of GA3 for 1 h. Total proteins were extracted from whole seedlings and analyzed by immunoblotting with affinity-purified anti-RGA antibody. Ponceau staining was used to confirm equal loading. Arrow indicates the position of the RGA protein.

We also performed the ABA and GA treatment experiment using Ler/PRGA:GFP-RGA as described by Achard et al. (2006) and found that GFP-RGA did accumulate to a slightly higher level by ABA in the presence or absence of GA treatment (see Supplemental Figure 5A online). Because ABA may reduce GA biosynthesis and lower bioactive GA levels in the Ler/PRGA:GFP-RGA plant, the observed effect of ABA treatment on GFP-RGA stability may be indirect. To test this hypothesis, we measured the relative mRNA levels of GA metabolic genes in this line. Our qRT-PCR data indicated that, indeed, the transcript levels of a GA biosynthetic gene, GA20ox1, were significantly reduced by ABA (see Supplemental Figure 5B online). Conversely, mRNA levels of the GA catabolic gene GA2ox6 were upregulated by ABA.

DISCUSSION

DELLA proteins are repressors that act directly downstream of the GA receptor to modulate all aspects of GA-induced growth and development in plants (Thomas and Sun, 2004; Griffiths et al., 2006; Nakajima et al., 2006). Elucidating the early gene regulatory network downstream of DELLA is crucial to our understanding of how GA controls plant development. By microarray analysis, we identified early GA- and DELLA-responsive genes that are putative DELLA direct targets in shoots of young Arabidopsis seedlings. Surprisingly, all of them are GA repressed and DELLA induced. ChIP-qPCR experiments provided evidence for in vivo interaction of a DELLA protein, RGA, with its putative target promoters. Several DELLA targets encode GA biosynthetic enzymes and GA receptors, indicating direct involvement of DELLA in feedback regulation. Most of the remaining DELLA target genes encode transcription factors/regulators, and ubiquitin E2 and E3 enzymes, which may be negative regulators acting downstream of DELLA in the GA response pathway. Our study also revealed a role of DELLA in mediating interaction between GA and ABA pathways.

Identification of DELLA Target Genes Involved in GA Responses

Because previous mutant analysis indicated that DELLA proteins affect all aspects of GA responses, we originally expected to find early GA-responsive genes to be mostly DELLA responsive. However, only 14 overlapping genes were identified between the GA-responsive and DELLA-responsive data sets in this study. This is likely due to two factors. First, most of the GA-responsive genes have very subtle changes in their expression at the 1-h GA treatment time point and therefore were difficult to detect in our experiments. For example, bHLH137, LBD40, and WRKY27 were not among the 14 overlapping genes, although qRT-PCR analysis supported that they are both GA and DELLA responsive (Figure 3). Secondly, the DEX-inducible system has a significant background noise because GVG appears to affect transcription of many genes. We attempted to remove genes whose expression was mainly altered by GVG by filtering the DELLA-induced gene list with those genes that were affected in the vector line. However, the remaining genes on the list are not all DELLA responsive when we compared their expression in the wild type, ga1-3, ga1-3 rga-24 gai-t6, and PRGA:(rga-Δ17) by qRT-PCR (e.g., BT4, Exp-PT2, and UBC17; Figure 3). In addition, IQD22, which responded to GA and DELLA (Table 2, Figure 3), was originally excluded from the overlapping gene list because GVG had a strong effect on its expression (FC = 5.5, P = 0.004; see Supplemental Table 3 online). Due to these limitations, we may have missed some of the DELLA targets whose expression is very subtly affected by GA treatment or strongly affected by GVG. In addition, the 475 putative DELLA-responsive genes listed in Supplemental Table 4 online need to be verified by further experimentation. The levels of rga-Δ17 protein in the DEX-(rga-Δ17) transgenic line, after 2 and 4 h of DEX treatment, are ∼8 and 16 times higher than RGA in the ga1-3 mutant, respectively (see Supplemental Figure 1B online). It is possible that some of the DELLA-responsive genes listed in Supplemental Table 4 online are false positives due to overexpression of rga-Δ17. However, for our final list of 14 DELLA target genes, we have strong evidence from analyzing their expression in DELLA loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutants that they are indeed responsive to both DELLA and GA. Similarly, the use of a 35S:RGA-TAP transgenic line for ChIP-qPCR analysis may raise concerns because overexpression of a transcription factor/regulator may result in nonspecific binding to DNA and/or other proteins. Phenotypic characterization of this line suggests that this is unlikely. The transgenic line 35S:RGA-TAP in the double mutant rga-24 ga1-3 background displayed a dwarf phenotype that is nearly identical to ga1-3 (see Supplemental Figure 3 online), indicating that this transgene rescued the rga defect as effectively as the endogenous RGA.

A Direct Role of DELLA in Maintaining GA Homeostasis

GA homeostasis is achieved by a feedback mechanism that appears to coordinate activities in the GA metabolic and response pathways (Hedden and Phillips, 2000; Sun and Gubler, 2004). Under GA-deficient conditions or in mutants with reduced GA signaling (e.g., gai-1, rga-Δ17, and sly1), transcript levels of GA biosynthetic genes, such as GA20ox and GA3ox, are upregulated, whereas expression of the GA catabolic gene GA2ox is downregulated. Conversely, GA application or mutations that lead to increased GA signaling, such as rga and gai null alleles, cause reduced expression of GA3ox and GA20ox and elevated expression of GA2ox. Recently, expression of GID1 genes in Arabidopsis was also found to be under feedback regulation. Transcript levels of all three GID1 genes are downregulated upon GA treatment (Griffiths et al., 2006). In addition, GID1 transcript levels were more elevated in ga1-3 and PRGA:(rga-Δ17) than in the wild type. In the triple (ga1 rga gai) and quintuple (ga1 rga gai rgl1 rgl2) null mutants, their transcripts are similar to the wild type (Cao et al., 2006; Griffiths et al., 2006). Although the feedback phenomena have been well documented, the molecular mechanism involved is unclear. Evidence presented in this report supports that GA3ox1, GA20ox2, GID1a, and GID1b may be direct DELLA targets. Our microarray and qRT-PCR data showed that these genes are early GA and DELLA responsive. ChIP-qPCR assays further indicate that RGA is associated with the promoters of GID1a and GID1b in vivo. The lack of significant enrichment of GA20ox2 and GA3ox1 promoters could be because DELLA associates with its target sequences via other DNA binding proteins. In this study, GID1c was not identified as an early GA- and DELLA-responsive gene, probably because its responses to GA and DELLA are subtler than GID1a and GID1b. This possibility is supported by our previous qRT-PCR analysis of these genes (Griffiths et al., 2006). Surprisingly, we did not find any GA2ox genes in our overlapping gene list or in either of our individual lists for each microarray experiment, suggesting that GA2ox may respond at a later time point and is not a direct DELLA target. Our results suggest that DELLA proteins not only are repressors of GA signaling, but they also modulate GA homeostasis by upregulating expression of GA biosynthetic and GA receptor genes. A similar mechanism has been reported recently in the BR pathway, in which a positive regulator of BR signaling (BZR1) represses transcription of several BR biosynthetic genes (He et al., 2005).

Putative DELLA Downstream Targets: Transcription Factors/Regulators and Ubiquitin E2/E3 Enzymes

Several putative DELLA target genes are predicted to function in transcriptional regulation or in proteolysis of downstream GA response components. Among the previously studied Arabidopsis bHLH genes, SPATULA and PIL5 inhibit seed germination by repressing GA3ox transcription and inducing expression of GA2ox (Penfield et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2006). Further studies on PIL5 demonstrated that RGA and GAI are its direct targets, whereas its regulation of GA metabolic genes is indirect via an unknown mechanism (Oh et al., 2007). MYB and bHLH protein complexes have been shown to function in cellular pathways, such as anthocyanin biosynthesis, trichome formation, and ABA and drought responses (Lloyd et al., 1992; Abe et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003). It is conceivable that products of the DELLA-induced genes bHLH137, bHLH154, and MYB may act as repressors of GA signaling, either by themselves or as heterodimers. Characterized Arabidopsis WRKY genes function in various plant responses to developmental cues or to pathogens (Eulgem et al., 2000). Two rice WRKYs (Os WRKY51 and 71) when transiently expressed in aleurone cells, act as transcriptional repressors of GA signaling that interfere with GAMYB and block α-amylase gene expression (Zhang et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2006). DELLA-induced WRKY27 may play a similar role in regulating GA signaling in Arabidopsis.

SCL3 belongs to the plant-specific GRAS family of putative transcriptional regulators (Pysh et al., 1999; Bolle, 2004). Two Arabidopsis GRAS members, SCR and SHR, regulate radial root patterning (Di Laurenzio et al., 1996; Nakajima et al., 2001). Recent microarray and ChIP-qPCR analysis indicated that SHR binds to promoters of SCR and SCL3 and activates their transcription (Levesque et al., 2006). Together with evidence presented here, GRAS proteins can regulate transcription by interacting with target promoters, either directly or through other transcription factor(s). GRAS proteins also appear to function in transcriptional networks to modulate expression of other GRAS genes.

LBD40 belongs to the class II subgroup of plant-specific AS2/LBD protein family (Iwakawa et al., 2002; Shuai et al., 2002). All members of this family contain an LBD domain with a conserved Cys-rich motif, which may form a zinc finger. However, only class I LBD proteins contain a coiled-coil protein–protein interaction domain, suggesting that classes I and II may have distinct functions. Two previously characterized class I LBD genes (AS2 and LBD36) encode nuclear proteins that control the development of lateral organs (leaf and/or flowers) (Iwakawa et al., 2002; Chalfun-Junior et al., 2005). GA also appears to promote lateral organ differentiation (Sakamoto et al., 2001; Hay et al., 2002). One possible role of LBD40 and perhaps other class II LBD members is negative regulation of GA-promoted lateral organ development.

IQD22 and BT4 encode nuclear CaM binding proteins, suggesting that Ca2+ may mediate GA-regulated gene expression. IQD22 belongs to the IQD family with a plant-specific IQ domain that contains three CaM binding motifs (Abel et al., 2005). BT4 has two protein–protein interaction domains: a BTB/POZ domain for dimer or oligomer formation and a zinc finger TAZ domain that is present in transcriptional modulators (Kanai et al., 2000; Du and Poovaiah, 2004). Future studies on IQD22 and BT4 will shed light on the regulatory mechanism of these proteins and Ca2+ in GA responses.

XERICO is an H2-type RING E3 protein that when overexpressed in Arabidopsis causes dramatic ABA accumulation, which leads to increased drought tolerance (Ko et al., 2006). However, transcript levels of ABA biosynthetic genes are not affected by overexpression of XERICO, suggesting that XERICO may induce ABA accumulation by affecting the activity of an ABA metabolic enzyme(s). XERICO contains a putative chloroplast transit peptide (Emanuelsson et al., 1999), although the SubCellular Proteomic Database (http://www.plantenergy.uwa.edu.au/applications/suba) predicts that it is equally likely to be cytoplasmic or plastid localized (Heazlewood et al., 2005, 2007). Early portions of the ABA biosynthetic pathway (until the step catalyzed by 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase) occur in the plastid, whereas later steps are localized in the cytosol (Nambara and Marion-Poll, 2005). One possible role of XERICO would be to mediate inactivation or degradation of a negative regulator of ABA biosynthesis. Our analysis of the loss-of-function xerico mutant supports that XERICO indeed promotes ABA accumulation. Our data also suggest that DELLA may upregulate ABA accumulation by inducing XERICO expression, revealing an interesting regulatory circuitry between GA and ABA pathways.

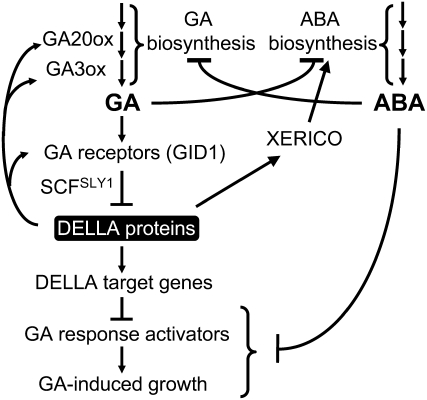

Model of the GA Biosynthesis and Signaling Networks and Interaction between GA and ABA Pathways

Our model (Figure 8) reflects the regulatory networks that control GA biosynthesis and GA signaling pathways as well as the interaction between GA and ABA pathways. GA20ox and GA3ox catalyze the final steps in the synthesis of bioactive GA. Upon binding to the GA receptor GID1, the GA-GID1 complex targets DELLA proteins for ubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome via the SCFSLY1 E3 ligase. Based on our microarray and qRT-PCR data (Table 2), DELLA inhibits GA signaling by activating its downstream target genes (presumably encoding GA signaling repressors). DELLA also feedback induces expression of GA20ox2, GA3ox1, and GID1 (Table 2; Griffiths et al., 2006). In addition, DELLA proteins induce XERICO expression, which then promotes ABA accumulation (Ko et al., 2006). Inhibition of GA-promoted processes by DELLAs is therefore achieved by modulating both GA and ABA pathways.

Figure 8.

Model of GA Signaling Network and Interaction between GA and ABA Pathways in Arabidopsis.

GA and ABA not only mutually inhibit each other's biosynthesis but also promote each other's catabolism (data not shown). Inhibition of GA-promoted processes by DELLA proteins is achieved by modulating both GA and ABA pathways. DELLA also plays a direct role in maintaining GA homeostasis by inducing genes encoding GA biosynthetic enzymes and GA receptors. Our data support the idea that ABA inhibits GA signaling downstream of DELLA, although ABA direct targets need to be elucidated.

Although ABA was shown to stabilize the GFP-RGA fusion protein (Achard et al., 2006; Penfield et al., 2006), the endogenous RGA protein is not protected by ABA treatment in our study. Our results agree with the studies in barley aleurone showing that ABA interferes with the GA signaling pathway by acting downstream of DELLA (Gómez-Cadenas et al., 2001; Gubler et al., 2002). In addition, ABA and GA mutually affect each other's metabolism. For example, the Arabidopsis ABA-deficient mutant aba2 exhibits increased GA biosynthesis (Seo et al., 2006), and the GA-deficient mutant ga1-3 accumulates higher amounts of ABA (Oh et al., 2007). Also, we observed that ABA treatment may affect GA levels by decreasing the expression of GA biosynthetic genes and inducing those involved in GA catabolism (see Supplemental Figure 5B online). Therefore, interactions between GA and ABA pathways occur in both their metabolic and signaling pathways to balance the antagonistic activities of these two hormones in plants.

This study uncovered two roles of DELLA proteins: direct feedback regulation of GA homeostasis and interaction with the ABA pathway. Most of the DELLA immediate targets are regulatory proteins, some of which may function in modulating transcription of downstream GA-responsive genes, and others regulate protein activity or stability of their targets. Future reverse genetic and biochemical studies of these newly identified DELLA targets will help to dissect the downstream regulatory network in GA signaling, which is responsible for the eventual changes in plant growth and development.

METHODS

Plasmid Constructions

Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 5 online. DNA sequencing was performed to confirm the absence of sequence errors in plasmid inserts that were generated by PCR amplification. For making the DEX-inducible rga-Δ17 [DEX-(rga-Δ17)] construct (pRG217), the rga-Δ17 coding region was amplified using the primers 503 and 504 from pRG59 (Dill et al., 2001). The PCR product was purified and digested with SalI and SpeI and subcloned into the XhoI-SpeI sites of the binary vector pTA7001 (Aoyama and Chua, 1997). For RGA-TAP overexpression, the RGA coding sequence was amplified by PCR using primers RGA-224 and NotRGAR-34 and cloned into pCR4Blunt-TOPO (Invitrogen) to generate pCRRGA. The BamHI-NotI fragment from pCRRGA was cloned into BamHI-NotI sites of pENTR1A (Invitrogen), resulting in pENTRRGA (without stop codon). The RGA fragment of pENTRRGA was inserted into the binary vector pYL436 (Rubio et al., 2005) by Gateway reaction using Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix (Invitrogen) to generate pKM30 (CaMV35S:RGA-TAP).

Plant Materials

All mutant and transgenic lines in this study derived from Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Ler (wild type), with the exception of the xerico mutant that was isolated from the Col-0 ecotype. In the latter case, Col-0 was used as the wild-type control. The homozygous mutants ga1-3, ga1-3 rga-24, and ga1-3 rga-24 gai-t6 and the transgenic lines PRGA:rga-Δ17 and PRGA:GFP-RGA were described previously (Dill et al., 2001; Dill and Sun, 2001; Silverstone et al., 2001). All new transgenic lines were generated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens–mediated transformation using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). For the DEX-inducible system, Ler was transformed with pRG217 and pTA7001 to generate the DEX-(rga-Δ17) lines and vector control lines, and transformants were selected on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium containing 35 mg/mL hygromycin B (Sigma-Aldrich). Lines with a 3:1 ratio of resistant:sensitive (in T2) were tested in the T3 generation to identify homozygous transgene plants. The vector control line L7001-465 and DEX-(rga-Δ17) line L217-3b11 that accumulated most similar levels of GVG mRNA were used for the microarray experiment. To generate the RGA-TAP transgenic lines, ga1-3 rga-24 was transformed with plasmid pKM30. Lines with a 3:1 (resistant:sensitive) segregation ratio in the T2 generation were selected on MS plates supplemented with 40 mg/L gentamicin sulfate. Line C3-1 fully complemented the rga-24 mutation. T2 and T3 plants were used for immunoblotting and ChIP experiments.