Abstract

Stagonospora nodorum is a major necrotrophic fungal pathogen of wheat (Triticum aestivum) and a member of the Dothideomycetes, a large fungal taxon that includes many important plant pathogens affecting all major crop plant families. Here, we report the acquisition and initial analysis of a draft genome sequence for this fungus. The assembly comprises 37,164,227 bp of nuclear DNA contained in 107 scaffolds. The circular mitochondrial genome comprises 49,761 bp encoding 46 genes, including four that are intron encoded. The nuclear genome assembly contains 26 classes of repetitive DNA, comprising 4.5% of the genome. Some of the repeats show evidence of repeat-induced point mutations consistent with a frequent sexual cycle. ESTs and gene prediction models support a minimum of 10,762 nuclear genes. Extensive orthology was found between the polyketide synthase family in S. nodorum and Cochliobolus heterostrophus, suggesting an ancient origin and conserved functions for these genes. A striking feature of the gene catalog was the large number of genes predicted to encode secreted proteins; the majority has no meaningful similarity to any other known genes. It is likely that genes for host-specific toxins, in addition to ToxA, will be found among this group. ESTs obtained from axenic mycelium grown on oleate (chosen to mimic early infection) and late-stage lesions sporulating on wheat leaves were obtained. Statistical analysis shows that transcripts encoding proteins involved in protein synthesis and in the production of extracellular proteases, cellulases, and xylanases predominate in the infection library. This suggests that the fungus is dependant on the degradation of wheat macromolecular constituents to provide the carbon skeletons and energy for the synthesis of proteins and other components destined for the developing pycnidiospores.

INTRODUCTION

Stagonospora nodorum (syn. Phaeosphaeria) is a major pathogen of wheat (Triticum aestivum) in most wheat-growing areas of the world. It is the major cause of losses due to foliar pathogens in Western Australia and north central and northeastern North America (Solomon et al., 2006a), and until the 1970s, it was the major foliar necrotrophic pathogen in Europe (Bearchell et al., 2005). Infection begins when spores (ascospores or asexual pycnidiospores) land on leaf tissue (Bathgate and Loughman, 2001; Solomon et al., 2006b). The spores rapidly germinate to produce hyphae that invade the leaf, using hyphopodia to gain entry to epidermal cells or by growing directly through stomata (Solomon et al., 2006b). The hyphae rapidly colonize the leaves and begin to produce pycnidia in 7 to 10 d. The infection has been divided into three metabolic phases (Solomon et al., 2003a). The first phase is penetration of the host epidermis and is fuelled predominantly by lipid stores in the spores (Solomon et al., 2004a); the second is proliferation throughout the interior of the leaf, involves toxin release (Liu et al., 2006), and uses host-derived simple carbohydrate sources (Solomon et al., 2004a); the final phase produces the new spores, but so far the metabolic requirements for pycnidiation are unclear.

The infection epidemiology follows a polycyclic pattern with repeated cycles of both asexual (Bathgate and Loughman, 2001) and sexual (B.A. McDonald, unpublished data) infection throughout the growing season. New rounds of infection are initiated by rain-splash of pycnidiospores and wind dispersal of ascospores. Eventually, wheat heads become infected, causing the glume blotch symptom. In Mediterranean climates, the fungus over-summers in senescent straw and stubble. Seed transmission can be important but is readily controlled by fungicides. Infected stubble harbors the pseudothecia that produce airborne (Bathgate and Loughman, 2001), heterothallic (Bennett et al., 2003) ascospores to reinitiate the infection in the following growing season. Epidemiological and population genetic evidence suggest that the fungus undergoes meiosis in the field regularly and that gene flow is global (Stukenbrock et al., 2006).

S. nodorum is a member of the Dothideomycetes class of filamentous fungi. This is a newly recognized major class that broadly replaced the long-recognized loculoascomycetes (Winka and Eriksson, 1997) and includes the causal organisms of many economically important plant diseases; notable examples are black leg (Leptosphaeria maculans), southern maize (Zea mays) leaf blight (Cochliobolus heterostrophus), barley (Hordeum vulgare) net blotch (Pyrenophora teres), apple scab (Venturia inaequalis), black sigatoka (Mycosphaerella fijiensis) of banana (Musa spp), wheat leaf blotch (M. graminicola), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) leaf mold (Passalora fulva), and Ascochyta blight of many legume species (Ascochyta spp). The taxon also includes large numbers of saprobic species occurring on substrates ranging from dung to plant debris, a few species associated with animals, and several lichenized species (Del Prado et al., 2006).

Many plant pathogens in this group produce host-specific toxins (Wolpert et al., 2002). These molecules interact with specific host factors to produce disease symptoms only in selected genotypes of specific plant hosts. Well-known examples are found in Alternaria alternata, Cochliobolus heterostrophus, and Pyrenophora tritici-repentis, while species in the genera Mycosphaerella, Corynespora, and Stemphylium are also thought to produce host-specific toxins (Agrios, 2005). Proteinaceous host-specific toxins have recently been shown to be important virulence determinants in S. nodorum (Liu et al., 2004a, 2004b), including one whose gene is thought to have been interspecifically transferred to the wheat tan spot pathogen, P. tritici-repentis (Friesen et al., 2006). Only one example of a host-specific toxin has been identified outside of the Dothideomycetes (Wolpert et al., 2002). Non-host-specific toxins produced by species in this group include cercosporin (Cercospora) and solanopyrone (Ascochyta) but are also produced by many other fungal taxa (Agrios, 2005).

S. nodorum is an experimentally tractable organism, which is easily handled in defined media, was one of the first fungal pathogens to be genetically manipulated (Cooley et al., 1988), and has been a model for fungicide development (Dancer et al., 1999). Molecular analysis of pathogenicity determinants is aided by facile tools for gene ablation and rapid in vitro phenotypic screens, and thus far, a small number of genes required for pathogenicity have been identified (Cooley et al., 1988; Bailey et al., 1996; Bindschedler et al., 2003; Solomon et al., 2003b, 2004a, 2004b, 2005, 2006a). It has thus emerged as a model for dothideomycete pathology.

Whole-genome sequences have been described for a handful of fungal saprobes and pathogens (Galagan et al., 2003, 2005; Jones et al., 2004; Dean et al., 2005; Kamper et al., 2006). Here, we present an initial analysis of the genome sequence of the dothideomycete S. nodorum. Gene expression studies using EST libraries from axenic mycelium and heavily infected wheat leaves complement the genome sequence and provide a broad-based analysis of the genomic basis of infection by S. nodorum.

RESULTS

Acquisition and Analysis of the Genome Sequence

The genome sequence was obtained using a whole-genome shotgun approach. Approximately 10× sequence coverage was obtained as paired-end reads from plasmids of 4 and 10 kb plus 40-kb fosmids. Reads were assembled using Arachne (Jaffe et al., 2003), forming 496 contigs totaling 37,071 kb. The contig N50 was 179 kb, meaning an average base in the assembly lies within a contig of at least 179 kb. Greater than 98% of the bases in the assembly have a consensus quality score of ≥40, corresponding to the standard error rate of fully finished sequence. The contigs are connected in 109 scaffolds spanning 37,202 kb with a scaffold N50 of 1.05 Mb. More than 50% of the genome is contained in the 13 largest scaffolds. Within the scaffolds, only ∼140 kb is estimated to lie within sequence gaps. Thus, in terms of representation, contiguity, and sequence accuracy, the draft assembly is of high quality. The mitochondrial genome comprises a circle of 49,761 bp (GenBank accession number EU053989). It replaces two of the auto-assembled scaffolds, 52 and 65. The nuclear genome is therefore assembled in 107 scaffolds of total length 37,164,227 bp.

General features of the assembly are described in Table 1. As detailed below, the genomic sequencing was complemented by sequencing EST libraries. One library was constructed from axenically grown mycelium, and after removing vector, poly(A) sequences, poor-quality sequences, and sequences <100 bp, there were 7750 remaining ESTs. Of these, 97.6% mapped to the genome assembly via Sim4, and 1.4% mapped to unassembled reads. This indicates that the assembly has achieved good coverage of the genome. In all, seven EST contigs and 13 singletons clustered to the unassembled reads.

Table 1.

The Assembly of the S. nodorum Nuclear Genome Sequence

| Scaffold count | 107 |

| Total/bp | 37,164,227 |

| Coverage | ∼10× |

| G + C % | 50.3% |

| Scaffold minimum length/bp | 2,005 |

| Scaffold maximum length/bp | 2,531,949 |

| Scaffold median length/bp | 32,376 |

| Scaffold mean length/bp | 347,329 |

| Gaps/number | 387 |

| Total length of gaps/bp | 146,025 |

| Max length of gap/bp | 11,204 |

| Median length of gap/bp | 325 |

Analysis of Repetitive Elements

Repetitive elements were identified de novo by identifying sequence elements that existed in 10 or more copies, were greater than 200 bp, and exhibited >65% sequence identity. The analysis revealed the presence of 25 repeat classes. Table 2 lists the general features of the repeats (see Supplemental Data Set 1 online). Only three, Molly, Pixie, and Elsa, had been detected earlier (GenBank accession numbers AJ277502, AJ277503, and AJ277966, respectively). Molly, Pixie, X15, and R37 show sequence characteristics of inverted terminal repeat–containing transposons, while Elsa, R9, and X11 appear to be retrotransposons. Repetitive elements were found individually throughout the genome but were often found in clusters spanning several kilobases.

Table 2.

Features of Repetitive Element Classes Found in the Nuclear Genome

| Repeat Name | Class | Count | Full Length (bp) | Occupied (bp) | Percentage of Genome | RIPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtelomeric | ||||||

| R22 | Telomeric repeat | 23 | 678 | 12,565 | 0.03 | No |

| X15 | Telomeric repeat/transposon or remnant | 37 | 6,231 | 89,126 | 0.24 | No |

| X26 | Telomeric repeat | 38 | 4,628 | 77,020 | 0.21 | No |

| X35 | Telomeric repeat | 19 | 1,157 | 14,393 | 0.04 | No |

| X48 | Telomeric repeat | 22 | 265 | 5,631 | 0.02 | No |

| Ribosomal | ||||||

| Y1 | rDNA repeat | 113 | 9,358 | 40,1890 | 1.08 | No |

| Other | ||||||

| Elsa | Transposon | 17 | 5,240 | 34,287 | 0.09 | Yes |

| Molly | Transposon | 40 | 1,862 | 50,453 | 0.14 | Yes |

| Pixie | Transposon | 28 | 1,845 | 39,148 | 0.11 | No |

| R10 | Unknown | 59 | 1,241 | 44,018 | 0.12 | No |

| R25 | Unknown | 23 | 3,320 | 44,860 | 0.12 | No |

| R31 | Unknown | 23 | 3,031 | 40,267 | 0.11 | No |

| R37 | Transposon or remnant | 98 | 1,603 | 104,915 | 0.28 | No |

| R38 | Unknown | 25 | 358 | 8,556 | 0.02 | No |

| R39 | Unknown | 29 | 2,050 | 35,758 | 0.10 | No |

| R51 | Unknown | 39 | 833 | 25,538 | 0.07 | No |

| R8 | Unknown | 48 | 9,143 | 275,643 | 0.74 | No |

| R9 | Transposon or remnant | 72 | 4,108 | 163,739 | 0.44 | No |

| X0 | Unknown | 76 | 3,862 | 145,268 | 0.39 | No |

| X11 | Transposon or remnant | 36 | 8,555 | 128,638 | 0.35 | No |

| X12 | Unknown | 29 | 2,263 | 25,369 | 0.07 | No |

| X23 | Unknown | 29 | 685 | 11,679 | 0.03 | No |

| X28 | Unknown | 30 | 1,784 | 32,002 | 0.09 | No |

| X3 | Unknown | 213 | 9,364 | 463,438 | 1.24 | No |

| X36 | Unknown | 10 | 512 | 5,067 | 0.01 | No |

| X96 | Unknown | 14 | 308 | 4,321 | 0.01 | No |

| Sum | 4.52 | |||||

Evidence from the alignment that the repeat has been subjected to RIP mutation.

Telomere-associated repeats were identified by searching for examples of the canonical telomere repeat TTAGGG at the termini of auto-assembled scaffolds. Physically linked repetitive sequences were then analyzed for association with the TTAGGG sequence repeats. Between 19 and 38 copies of telomere-associated repeats were found in the assembly.

Repeat-induced point (RIP) mutation is a fungal-specific genome-cleansing process that detects repeated DNA at meiosis and introduces C-to-T mutations into the copies (Cambareri et al., 1989). Using the parameters defined for Magnaporthe grisea (Dean et al., 2005), we identified RIP-like characteristics in several of the repeat classes (Table 2; see Supplemental Data Set 1 online). The transposons Molly and Elsa were the most clearly affected classes. None of the telomere-associated repeats displayed RIP characteristics.

Mitochondrial Genome

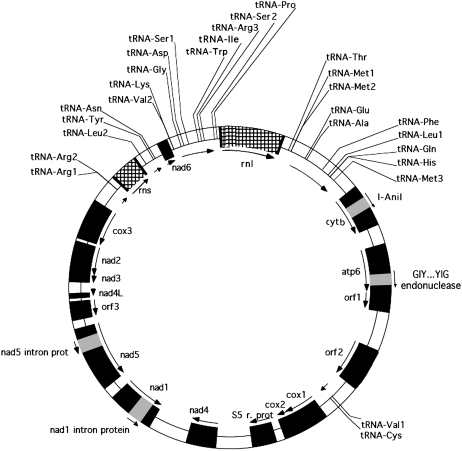

The mitochondrial genome of S. nodorum assembled as a circular molecule of 49,761 bp, with an overall G + C content of 29.4%. It contains the typical genes encoding 12 inner mitochondrial membrane proteins involved in electron transport and coupled oxidative phosphorylation (nad1-6 and nad4L, cytb, cox1-3, and atp6), the 5S ribosomal protein, three open reading frames (ORFs) of unknown function, and genes for the large and small rRNAs (rnl and rns) (Figure 1). The genes were coded on both DNA strands. The 27 tRNAs can carry all 20 amino acids. All tRNA secondary structures showed the expected cloverleaf form, but tRNA-Thr and tRNA-Phe had nine nucleotides in the anticodon loop instead of the typical seven, and tRNA-Arg2 had 11 nucleotides in its anticodon loop (Lowe and Eddy, 1997).

Figure 1.

The Structure of the Mitochondrial Genome.

Black segments are exons, hatched segments are rRNA genes, and white segments are introns. The direction of transcription is indicated with the arrows.

Gene Content

The initial gene prediction process identified 16,957 gene models of which 16,586 were located on the 107 nuclear scaffolds. A revised gene prediction procedure, using new ESTs (see below) and 795 fully supported and manually annotated gene models, identified 10,762 version 2 nuclear gene models. Of these, 617 genes corresponded to a merging of version 1 genes; in 50 cases, three prior gene models were merged, and in one case, four genes were merged. ESTs that aligned to unassembled reads identified one supported gene (SNOG_20000.2). A total of 5354 version 1 gene models were not supported but did not conflict with second-round predictions. We therefore conclude that S. nodorum contains a minimum of 10,762 nuclear genes of which all but 125 are supported by two gene prediction procedures and 2696 are supported by direct experimental evidence via EST alignment. These genes, with an identification format SNOG_xxxxx.2, were compared with the GenBank nonredundant protein database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Informative (not hypothetical, predicted, putative, or unknown) BLASTP (Altschul et al., 1990) hits with e-values <1 × 10−6 were found for 7116 genes (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). It is estimated that at least 46.6% of the nuclear genome is transcribed and 38.8% is translated.

The 5354 gene models without support from the reannotation have unaltered accession numbers as SNOG_xxxxx.1 and are retained for further possible validation and analysis. As 952 of these unsupported gene models have BLASTP hits with e-values <1 × 10−6, we predict that some will be validated as new evidence emerges.

Gene Expression during Infection

Two EST libraries were constructed and analyzed as part of this project. An in vitro library was constructed from axenic fungal mycelium transferred to media with oleate as the sole carbon source; this is referred to as the oleate library. An in planta library was made from bulked sporulating disease lesions on wheat 9, 10, and 11 d after infection (DAI). For both libraries, 5000 random clones were sequenced in both directions. The oleate library was entirely fungal and hence particularly suited for primary genome annotation purposes. The lipid growth media was chosen to replicate the early stages of infection in which lipolysis, the glyoxalate cycle, and gluconeogenesis are thought to be critical metabolic requirements (Solomon et al., 2004a). The in planta library was designed to reveal both plant and fungal genes expressed at a late stage of infection. After trimming and removal of plant ESTs and alignment to the genome assembly, the in planta library formed 1448 and the oleate library formed 1231 unigenes (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). Only 427 of the unigenes were found in both libraries. Although this represents 19% of the unigenes, it encompasses 46% of the ESTs, showing the genes expressed uniquely in one library are of relatively low expression.

The unigenes obtained from the in planta and oleate libraries were classified according to gene ontology (GO) categories. GO matches were obtained for 851 (59%) of the unigenes found in the in planta and 736 (59%) of those found in the oleate library. Relative numbers of ESTs and genes in different GO classes were compared (Table 3). GO categories were ranked by statistical discrimination between the two libraries, and the top 10 are shown for each of biological process, cellular component, and molecular function.

Table 3.

Comparison of GO Classification of Unigene and Transcript Numbers between the in Planta and Oleate Libraries

| Biological Processes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO Identifier | Description | Loci | In Planta | Oleate | P Valuea |

| Upregulated in planta | |||||

| GO:0006412 | Protein biosynthesis | 128 | 710 | 325 | 5.97E-19 |

| GO:0045493 | Xylan catabolism | 24 | 31 | 0 | 6.16E-09 |

| GO:0006508 | Proteolysis | 78 | 110 | 39 | 8.29E-07 |

| GO:0008643 | Carbohydrate transport | 58 | 22 | 0 | 1.26E-06 |

| GO:0000272 | Polysaccharide catabolism | 12 | 24 | 1 | 4.29E-06 |

| GO:0016068 | Type I hypersensitivity | 13 | 87 | 31 | 9.67E-06 |

| GO:0030245 | Cellulose catabolism | 16 | 18 | 0 | 1.33E-05 |

| GO:0005975 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 102 | 53 | 16 | 6.57E-05 |

| GO:0042732 | D-xylose metabolism | 2 | 25 | 4 | 2.01E-04 |

| GO:0009051 | Pentose-phosphate shunt, oxidative branch | 2 | 21 | 3 | 4.07E-04 |

| Upregulated oleate | |||||

| GO:0007582 | Physiological process | 24 | 8 | 48 | 1.04E-10 |

| GO:0006629 | Lipid metabolism | 20 | 6 | 40 | 1.42E-09 |

| GO:0006096 | Glycolysis | 21 | 42 | 92 | 5.93E-09 |

| GO:0006108 | Malate metabolism | 4 | 12 | 45 | 5.48E-08 |

| GO:0006099 | Tricarboxylic acid cycle | 20 | 50 | 85 | 4.11E-06 |

| GO:0015986 | ATP synthesis coupled proton transport | 26 | 34 | 65 | 6.56E-06 |

| GO:0006183 | GTP biosynthesis | 1 | 0 | 13 | 1.54E-05 |

| GO:0006228 | UTP biosynthesis | 1 | 0 | 13 | 1.54E-05 |

| GO:0006241 | CTP biosynthesis | 1 | 0 | 13 | 1.54E-05 |

| GO:0006334 | Nucleosome assembly | 12 | 65 | 95 | 3.21E-05 |

| Cellular Components | |||||

| GO Identifier | Description | Loci | In Planta | Oleate | P Valuea |

| Upregulated in planta | |||||

| GO:0005840 | Ribosome | 89 | 567 | 262 | 3.14E-15 |

| GO:0015935 | Small ribosomal subunit | 11 | 93 | 33 | 4.86E-06 |

| GO:0005576 | Extracellular region | 36 | 23 | 1 | 7.44E-06 |

| GO:0005730 | Nucleolus | 6 | 23 | 2 | 4.15E-05 |

| GO:0030529 | Ribonucleoprotein complex | 25 | 60 | 19 | 4.31E-05 |

| GO:0030125 | Clathrin vesicle coat | 9 | 7 | 0 | 8.86E-03 |

| GO:0016020 | Membrane | 338 | 127 | 122 | 1.07E-02 |

| GO:0016021 | Integral to membrane | 401 | 243 | 213 | 1.38E-02 |

| GO:0019867 | Outer membrane | 7 | 45 | 24 | 1.40E-02 |

| GO:0005874 | Microtubule | 19 | 8 | 1 | 1.97E-02 |

| Upregulated oleate | |||||

| GO:0005829 | Cytosol | 34 | 19 | 50 | 1.01E-06 |

| GO:0016469 | Proton-transporting two-sector ATPase complex | 24 | 27 | 60 | 1.41E-06 |

| GO:0000786 | Nucleosome | 11 | 65 | 95 | 3.21E-05 |

| GO:0043234 | Protein complex | 33 | 15 | 29 | 1.23E-03 |

| GO:0005739 | Mitochondrion | 102 | 138 | 147 | 1.62E-03 |

| GO:0005634 | Nucleus | 288 | 183 | 186 | 1.90E-03 |

| GO:0005777 | Peroxisome | 14 | 26 | 38 | 3.39E-03 |

| GO:0005746 | Mitochondrial electron transport chain | 8 | 36 | 47 | 4.40E-03 |

| GO:0045261 | Proton-transporting ATP synthase complex, catalytic core F(1) | 5 | 14 | 23 | 7.49E-03 |

| GO:0005778 | Peroxisomal membrane | 3 | 1 | 7 | 8.63E-03 |

| Molecular Functions | |||||

| GO Identifier | Description | Loci | In Planta | Oleate | P Valuea |

| Upregulated in planta | |||||

| GO:0003735 | Structural constituent of ribosome | 111 | 709 | 328 | 2.09E-18 |

| GO:0004553 | Hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds | 83 | 55 | 5 | 4.13E-10 |

| GO:0004252 | Ser-type endopeptidase activity | 14 | 43 | 3 | 6.92E-09 |

| GO:0005351 | Sugar porter activity | 64 | 22 | 0 | 1.26E-06 |

| GO:0046556 | α-N-arabinofuranosidase activity | 6 | 19 | 0 | 7.39E-06 |

| GO:0030248 | Cellulose binding | 19 | 18 | 0 | 1.33E-05 |

| GO:0004029 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD) activity | 1 | 15 | 0 | 7.85E-05 |

| GO:0050661 | NADP binding | 6 | 23 | 3 | 1.60E-04 |

| GO:0004185 | Ser carboxypeptidase activity | 8 | 13 | 0 | 2.56E-04 |

| GO:0004616 | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (decarboxylating) activity | 4 | 22 | 3 | 2.56E-04 |

| Upregulated oleate | |||||

| GO:0004459 | l-lactate dehydrogenase activity | 2 | 5 | 44 | 2.07E-11 |

| GO:0030060 | l-malate dehydrogenase activity | 2 | 5 | 44 | 2.07E-11 |

| GO:0005498 | Sterol carrier activity | 3 | 7 | 46 | 1.02E-10 |

| GO:0008415 | Acyltransferase activity | 17 | 4 | 34 | 4.64E-09 |

| GO:0005506 | Iron ion binding | 91 | 89 | 128 | 3.72E-06 |

| GO:0004550 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase activity | 1 | 0 | 13 | 1.54E-05 |

| GO:0005554 | Molecular function unknown | 49 | 40 | 65 | 7.95E-05 |

| GO:0046933 | Hydrogen-transporting ATP synthase activity, rotational mechanism | 24 | 34 | 58 | 8.73E-05 |

| GO:0046961 | Hydrogen-transporting atpase activity, rotational mechanism | 24 | 34 | 58 | 8.73E-05 |

| GO:0050660 | FAD binding | 27 | 13 | 30 | 2.85E-04 |

Probability of significant difference between the libraries (Audic and Claverie, 1997).

Coexpression of fungal gene clusters responsible for the synthesis of secondary metabolites (Bok and Keller, 2004) and pathogenicity (Kamper et al., 2006) has been observed. We compared the number of ESTs found in the in planta and oleate libraries to search for clusters of coexpressed genes. Using a window of 10 contiguous genes, we scanned for regions with biased ratios of ESTs from either library. One putatively in planta–induced region stood out. These six genes, SNOG_16151.2 to SNOG_16157.2, were exclusively in the in planta library with 4, 20, 0, 4 10, and 1 EST clones, respectively. The genes have best hits to a major facilitator superfamily transporter, a phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase, a CocE/NonD hydrolase, and a salicylate hydroxylase and are next to a transcription factor. Such a cluster may be involved in the degradation of phytols, phenylpropanoids, and catechols either for nutritional purposes, providing trichloroacetic acid intermediates via the β-ketoadipate pathway or to detoxify wheat defense compound(s). It is intriguing that overexpression of the thiolase in the β-ketoadipate pathway in L. maculans markedly reduced pathogenicity (Elliott and Howlett, 2006). Experiments to test these ideas in S. nodorum are in progress.

DISCUSSION

The estimated genome size of S. nodorum is 37.2 Mbp, which is significantly larger than the 28 to 32 Mbp previously estimated by pulsed-field gel analysis (Cooley and Caten, 1991). Electrophoretic karyotypes have proven to be unreliable estimators of total genome size in many fungal species (Orbach et al., 1988; Orbach, 1989; Talbot et al., 1993). In the case of S. nodorum, this discrepancy may be a consequence of comigration of chromosomal bands on pulsed-field gels leading to an underestimation of genome size (Cooley and Caten, 1991). The electrophoretic karyotype was found to be highly variable between strains, even when isolated from a single ascus, consistent with the generalization that many fungal species have plastic genome structures (Zolan, 1995). The revised genome size estimate is comparable to other sequenced filamentous fungi, such as the rice pathogen M. grisea, which is currently estimated to be 41.6 Mbp, and the nonpathogen Neurospora crassa now estimated at 39.2 Mbp.

Phylogenetic Analysis

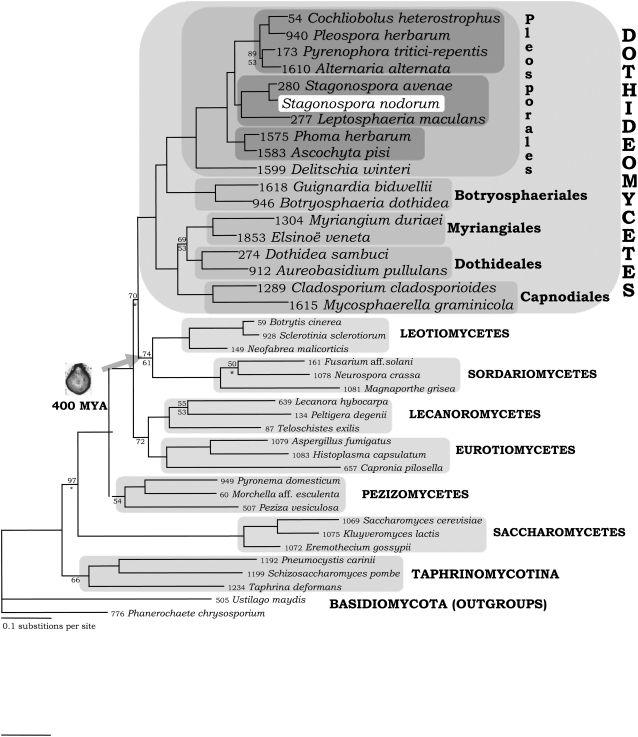

The genome sequence has confirmed the phylogenetic placement of S. nodorum in the class Dothideomycetes. Along with the Eurotiomycetes (containing Aspergillus and human pathogens such as Histoplasma), Lecanoromycetes (the majority of the lichenized species), Leotiomycetes (containing numerous endophytes and the plant pathogen Sclerotinia), and Sordariomycetes (with Neurospora, Magnaporthe, and Colletotrichum spp), the Dothideomycetes is now recognized as a major clade of the filamentous Ascomycota (James et al., 2006). Phylogenetic analyses of full fungal genomes and large-scale taxon sampling agree with the placement of S. nodorum and point to the rapid divergence of these major classes of ascomycetes (Robbertse et al., 2006; Spatafora et al., 2006). The tree in Figure 2 is a focused sampling of the largest classes of the Ascomycota with an emphasis on plant pathogenic species and those with genome sequences. The Dothideomycetes is supported as a single class and represented by samples of five of the nine currently proposed orders (Eriksson, 2006; Schoch et al., 2006). S. nodorum is placed in the Pleosporales, a large order containing >100 genera and several thousand species, many of which are important plant pathogens. The Pleosporaceae family contains Alternaria, Cochliobolus, and Pyrenophora (Kodsueb et al., 2006) and is closely related to the clade containing the genera Leptosphaeria and Phaeosphaeria (Stagonospora). Other orders in the Dothideomycetes include the Dothideales and the Capnodiales (Schoch et al., 2006), which contains the pathogen genera Mycosphaerella and Cladosporium.

Figure 2.

Phylogeny of Ascomycota Focused on Dothideomycetes.

Each species name is preceded by a unique AFTOL ID number (www.aftol.org). The tree is a 50% majority rule consensus tree of 45,000 trees obtained by Bayesian inference. All nodes had posterior probabilities of 100% except where numbers are shown above nodes. Similarly, all nodes had maximum likelihood bootstraps above 80% except where numbers are shown below nodes. Asterisks indicate nodes that were not resolved in >50% of bootstrap trees. Alignment data are provided in Supplemental Data Set 3 online. The gene data used are listed in Supplemental Table 3 online.

Repeated Elements in the Nuclear Genome

Prior to this study, only one unpublished study had been made of repetitive elements in the S. nodorum genome (Rawson, 2000). The de novo analysis of repeats is likely to become a feature of future genome sequencing projects as organisms with little prior molecular work are selected. The total amount of repetitive DNA in the S. nodorum nuclear genome is estimated at 4.5%. This compares with 9.5% in M. grisea. Some of these repeats could be associated with telomeres. Between 19 and 38 copies of telomere-associated repeats were found in the assembly. These numbers accord well with the 14 to 19 chromosomes visualized by pulsed-field electrophoresis (Cooley and Caten, 1991).

Studies of S. nodorum life cycle have indicated that it undergoes regular sexual crossing, particularly in areas with Mediterranean-style climates with the associated need to over-summer as ascospores (Bathgate and Loughman, 2001; Stukenbrock et al., 2006). The relatively low content of repetitive DNA is consistent with this observation. The prevalence of clear cases of RIP further confirms that meiosis is a frequent event. RIP has been found to varying degrees in other fungal genomes. It is notable that the closely related L. maculans has previously been shown experimentally to exhibit RIP (Idnurm and Howlett, 2003).

The Mitochondrial Genome

A distinctive feature of fungal mitochondrial genomes is the clustering of tRNA genes (Ghikas et al., 2006), and it is thought that both the tRNA gene content and their placement will be conserved in fungi (Table 4). The 27 tRNA genes clustered into five groups, with the two larger tRNA gene clusters flanking rnl, a pattern common to other fungal mitochondrial DNAs (mtDNAs) (Tambor et al., 2006). The tRNA gene cluster 5′ to rnl had GDS1WIS2P as a consensus, with its closest sequenced relative M. graminicola (GenBank accession number EU090238), while the 3′-downstream consensus was EAFLQHM, having many tRNA genes in the same order found in other Ascomycetes. Variation in the order of tRNAs, such as inversions in Epidermophyton floccosum (Ile-Trp) or in Podospora anserina and S. nodorum (Met-His), suggest that rearrangements are common in fungal mtDNAs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of tRNA Gene Clusters Flanking the rnl Gene of the mtDNA Genome in Several Ascomycetesa

| Organism | 5′-Upstream Regionb | rnl | 3′-Downstream Regionb | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. marneffei | RKG1G2DS1WIS2P | rnl | TEVM1M2L1AFL2QM3H | AY347307 |

| A. niger | KGDS1WIS2P | rnl | TEVM1M2L1AFL2QM3H | DQ217399 |

| M. graminicola | GDS1WIS2P | rnl | M1L1EAFL2YQM2HRM3 | EU090238 |

| S. nodorum | VKGDS1WIRS2P | rnl | T M1M2EAFLQHM3 | EU053989 |

| E. floccosum | KGDSIWSP | rnl | TEVM1M2L1AFL2QM3H | AY916130 |

| H. jecorina | ISWP | rnl | TEM1M2L1AFKL2QHM3 | AF447590 |

| P. anserina | ISP | rnl | TEIM1L1AFL2QHM2 | X55026 |

The tRNA gene order of listed organisms is based on GenBank sequences.

Capital letters refer to tRNA genes for the following: R, Arg; K, Lys; G, Gly; D, Asp; S, serine; W, Trp; I, Ile; P, Pro; T, Thr; E, Glu; V, Val; L, Leu; A, Ala; F, Phe; Q, Gln; H, His; Y, Tyr.

The numbers (1 to 3) indicate the presence of more tRNA genes for the same amino acid in the consensus sequence.

Kouvelis et al. (2004) argued that gene pairs nad2-nad3, nad1-nad4, atp6-atp8, and cytb-cox1 would remain joined in ascomycetes with some possible exceptions, as already detected in M. graminicola that present only two of these gene pairs coupled. In S. nodorum, the atp8-9 genes were not present, cytb-cox1 were uncoupled, and the nad1 and nad4 genes were on sections of the mtDNA in an inverted orientation. Two orfs (orf1 and orf2) had homologous sequences in the in planta EST library. While the M. graminicola mtDNA genome had no introns, four intron-encoded genes were found in S. nodorum, with high homology to LAGLIDADG-type endonucleases or GIY-YIG–type nucleases (see Supplemental Table 1 online). Intron-encoded proteins have also been reported in P. anserina (Cummings et al., 1990) and Penicillium marneffei (Woo et al., 2003).

Functional Analysis of Proteins

Our primary goal in obtaining the genome sequence was to reveal genes likely to be involved in pathogenicity. While some genes seem to be specifically associated with pathogenicity in a single organism, other genes and gene families have been generally associated with pathogenicity, albeit they are also found in nonpathogens (see http://www.phi-base.org/about.php; Baldwin et al., 2006). Some of the generic functions are listed (Table 5; see Supplemental Data Set 2 and Supplemental Table 2 online). EST support was found for 59 of the genes, with no statistically significant difference in the numbers of ESTs in the in planta and oleate libraries.

Table 5.

Comparison of Selected Gene Families Identified by PFAM (Release 21) Domains between S. nodorum and Latest BROAD Releases of M. grisea, N. crassa, and A. nidulans and Incomplete Data from C. heterostrophus and F. graminearum (Kroken et al., 2003; Gaffoor et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2005)

|

S. nodorum

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Family | Genes with PFAM Match | Genes with EST Clones | In Planta Clones | Oleate Clones | M. grisea Release 5 | N. crassa v3 Assembly 7 | A. nidulans Release 3 | C. heterostrophus or F. graminearum |

| G-alpha | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Cfem | 4 | 1 | 17 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 9 Ch 8 Fg |

| Rhodopsin | 2 | 2 | 14 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Hydrophobin class 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Hydrophobin class 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Feruloyl esterase | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 5 | |

| Cutinase | 11 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 3 | 4 | |

| Subtilisin | 11 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 26 | 6 | 3 | |

| Transcription factor | 94 | 25 | 37 | 43 | 97 | 83 | 195 | |

| Cytochrome p450 | 103 | 20 | 27 | 20 | 115 | 39 | 102 | |

| PKS | 19 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 24 | 7 | 28 | 24 Ch 14 Fg |

| NRPS | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 13 | 10 Ch |

| PKS-NRPS | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 Ch |

Nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) are modular enzymes that synthesize a diverse set of secondary metabolites, including the dothideomycete host-specific toxins AM-toxin, HC-toxin, and victorin from Alternaria and Cochliobolus species (Wolpert et al., 2002). NRPS genes from C. heterostrophus have been analyzed in detail (Lee et al., 2005). Comparison of both protein sequences and domain structure of the C. heterostrophus NRPS genes (NPS1-11) with the eight identified in S. nodorum was undertaken (Table 6). Putative orthology was determined by identifying reciprocal best hits among the gene sets. Three pairs were identified. SNOG_02134.2 was linked to NPS2, and both appear to be orthologous to the Aspergillus nidulans gene SidC (Eisendle et al., 2003), which is responsible for the synthesis of ferricrocin, an intracellular iron storage and transport compound involved in protection against iron toxicity (Eisendle et al., 2006). It is likely that SNOG_02134.2 and NPS2 play similar roles. SNOG_14638.2 was linked to NPS6, a ubiquitous gene with a related role in siderophore-mediated iron uptake and oxidative stress protection (Oide et al., 2006). Third, SNOG_14834.2 appears to be directly related to NPS4, Psy1 from Alternaria brassicae (Guillemette et al., 2004), and NPS2 from Alternaria brassicicola (Kim et al., 2007). Ab NPS2 mutants are reduced in virulence, and the gene is predicted to encode a component of the conidial wall. It is likely that SNOG_14834.2 will have a similar generic role. Reciprocal best-hit relationships were observed between a further two SNOG NRPS genes and other fungal genes; SNOG_09081.2 was related to PesA (Bailey et al., 1996) and SNOG_14908.2 to the Salps2 gene from Hypocrea lixii (Vizcaino et al., 2006). These genes plus SNOG_14834.2, SNOG_09488.2, and SNOG_01105.2 are all closely related to NPS4, suggesting that this five-gene subfamily is expanded in S. nodorum. Interestingly, a further seven NRPS genes from C. heterostrophus (NPS3, 5, 8, 10, 11, and 12) have no obvious ortholog in S. nodorum, suggesting expansion of this subfamily in the maize pathogen (Yoder and Turgeon, 2001). Intensive studies in C. heterostrophus showed that individual gene knockouts produced altered phenotypes only for NPS6 (Lee et al., 2005), indicating redundancy of function. The smaller complement of NRPS genes in M. grisea (eight) and S. nodorum indicate that these organisms may be more fruitful models to study NRPS function. Furthermore, although toxins have been implicated in the virulence of both pathogens, nonribosomal synthetases cannot be expected to be a major source. No ESTs were found corresponding to these genes. This may be due to their large size or to a generally low level of expression.

Table 6.

Potential Orthologs to S. nodorum NRPS Genes

| SN15 NRPS | Domain/Module Structurea | Best Hit | Accession Number | Organism | Reciprocalb | Percentage of Similarityc | Domain/Module Structured | Inferred Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOG_01105.2 | TCyAT/CATE/CAT/CAT | NPS4 | AAX09986 | C. heterostrophus | No | 37.2% | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C/T/C/T | Unknown |

| Abre Psy1 | AAP78735 | A. brassicae | No | 39.0% | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C/T/C/T | |||

| SNOG_02134.2 | AT/CAT/CAT/C/T/C | NPS2 | AAX09984 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 53.8% | AT/CAT/CAT/CATT/C | Iron uptake and oxidative stress protection |

| SidC | AAP56239 | A. nidulans | Yes | 40.3% | A/CA/CA/C/T/C | |||

| SNOG_07021.2 | ATCT | NPS1 | AAX09983 | C. heterostrophus | No | 13.8% | AT/CAMT/CAT/C | Unknown |

| PesA | CAA61605 | Metarhizium anisopliae | No | 10.2% | ATE/CAT/CAT/CATE/C | Unknown | ||

| SNOG_09081.2 | ATE/CAT/CAT/CAT/C | NPS4 | AAX09986 | C. heterostrophus | No | 33.0% | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C/T/C/T | Unknown |

| PesA | CAA61605 | M. anisopliae | Yes | 58.1% | ATE/CAT/CAT/CATE/C | Unknown | ||

| SNOG_09488.2 | CATE/CAT/CATE | NPS4 | AAX09986 | C. heterostrophus | No | 26.3% | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C/T/C/T | Unknown |

| PesA | CAA61605 | M. anisopliae | No | 36.6% | ATE/CAT/CAT/CATE/C | Unknown | ||

| SNOG_14098.2 | ATE/CAT/CAT/CATE/C | NPS4 | AAX09986 | C. heterostrophus | No | 32.3% | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C/T/C/T | Unknown |

| Salps2 | CAI38799 | Hypocrea lixii | Yes | 34.4% | TCAT/CAT/CAT | |||

| SNOG_14368.2 | AT/C/TT | NPS6 | AAX09988 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 73.5% | AT/C/AT | Virulence, siderophore- mediated iron metabolism, tolerance to oxidative stress |

| NPS6 | ABI51982 | C. miyabeanus | Yes | 73.5% | AT/C/TT | |||

| SNOG_14834.2 | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C | NPS4 | AAX09986 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 75.9% | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C/T/C/T | Virulence, conidial cell wall construction, spore germination/sporulation efficiency |

| Ab NPS2e | A. brassicicola | Yes | 78.2% | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C/T/C | ||||

| Abre Psy1 | AAP78735 | A. brassicae | Yes | 78.0% | TECAT/CATE/CAT/CATE/C/T/C/T |

Domain abbreviations: A, adenylation; C, condensation; Cy, Cyclization; E, epimerization; T, thiolation; Te, Thioesterase. Potential orthologs were identified by best BLASTP hits to NRPS genes in C. heterostrophus (Lee et al., 2005) and by best informative hit to the nonredundant database at NCBI of e-value <1 × 10−10.

The best hit of the identified gene in the S. nodorum gene set was observed reciprocally.

Percentage of similarity of ortholog pairs (Needleman and Wunsch, 1970) via NEEDLE (Rice et al., 2000).

Domain structure and modular organization for all sequences was determined via the online NRPS-PKS database (Ansari et al., 2004). It should be noted that domain structure predictions may vary slightly from those stated in the original studies.

Protein sequence for Ab NPS2 available in Supplemental Appendix S2 online from Kim et al. (2007).

Polyketide synthases (PKSs) are a second modular gene family strongly associated with pathogenicity (Kroken et al., 2003; Gaffoor et al., 2005), being responsible for the production of T-toxin from C. heterostrophus and PM-toxin from Mycosphaerella zeae-maydis (Yun et al., 1998; Baker et al., 2006). S. nodorum is predicted to contain 19 PKS genes compared with the 24, 14, and 24 in the pathogens M. grisea, Fusarium graminearum, and C. heterostrophus, respectively, and 28 in the saprobe A. nidulans but significantly more than the seven in N. crassa (Table 5). Orthology relationships between the well-studied F. graminearum and C. heterostrophus gene sets and S. nodorum are shown in Table 7. Reciprocal best BLAST hits were observed with eight genes from C. heterostrophus and five from F. graminearum. This close relationship, particularly with C. heterostrophus, reflects the close phylogenetic relationship and suggests an ancient origin for the majority of the PKS paralogs (Kroken et al., 2003). SNOG_11981.2 is supported by five ESTs from the in planta library and none from the oleate library, consistent with upregulation during infection and sporulation (no other PKSs have EST support). This gene is orthologous to nonreducing clade 2 PKS genes that are associated with 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene melanin biosynthesis in Bipolaris oryzae and many other pathogens (Kroken et al., 2003; Moriwaki et al., 2004; Amnuaykanjanasin et al., 2005). We showed previously that S. nodorum produces melanin from dihydroxyphenlyalanine (Solomon et al., 2004b), for which a PKS would not be necessary. This finding suggests that either S. nodorum produces 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene melanin in addition to dihydroxyphenlyalanine melanin or that SNOG_11981.2 plays another role.

Table 7.

Potential Orthologs of S. nodorum PKS Genes

| SN15 PKS | Domain/Module Structure | Best Hit | Accession Number | Organism | Reciprocal | Similarity | Inferred Clade | Domain/Module Structure | Inferred Function of Ortholog |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNOG_00477.2 | KsAtKrAcp | fg12100 | F. graminearum | No | 21.6% | Fungal 6MSAS | KsAtAcp/KrAcp/Acp | 6-Methylsalicylic acid synthesis (Fujii et al., 1996) | |

| PKS25 | AAR90279 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 59.7% | KsAtKrAcp | ||||

| atX | BAA20102 | A. terreus | Yes | 69.0% | KsAtKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_02561.2 | KsAtErKrAcp | fg12109 | F. graminearum | No | 42.1% | Reducing PKS clade I | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of diketide moiety of compactin or similar polyketide (Abe et al., 2002a, 2002b) | |

| PKS3 | AAR90258 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 45.8% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| mlcB | BAC20566 | P. citrinum | Yes | 47.7% | KsAtDhErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_04868.2 | KsAtErKrAcp | fg05794 | F. graminearum | Yes | 38.9% | Reducing PKS clade I | KsAtAcp/ErKrAcp | Synthesis of squalestatin (Nicholson et al., 2001) | |

| PKS6 | AAR90261 | C. heterostrophus | No | 46.5% | KsAtErKr | ||||

| type I PKS | AAO62426 | Phoma sp C2932 | No | 49.8% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_05791.2 | KsAtErKrAcp | fg12109 | F. graminearum | Yes | 43.1% | Reducing PKS clade I | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of alternapyrone (Fujii et al., 2005) | |

| PKS5 | AAR90261 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 73.1% | KsAtErKr | ||||

| atl5 | BAD83684 | A. solani | Yes | 79.2% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_06676.2 | KsAtErKr | fg01790 | F. graminearum | No | 31.3% | Reducing PKS clade IV | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of fumonisin (Proctor et al., 1999) | |

| PKS14 | AAR92221 | G. moniliformis | No | 31.8% | KsAtErKr | ||||

| FUM1 | AAD43562 | G. moniliformis | No | 30.0% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_06682.1 | KsAtAcp | fg03964 | F. graminearum | No | 36.2% | Nonreducing PKS clade III (uncharacterized) | KsAtAcp | Synthesis of citrinin (Shimizu et al., 2005) | |

| PKS17 | AAR90253 | B. fuckeliana | Yes | 43.9% | KsAtAcp | ||||

| pksCT | BAD44749 | M. purpureus | Yes | 44.7% | KsAtAcp | ||||

| SNOG_07866.2 | KsAtKr | fg12100 | F. graminearum | No | 37.8% | Reducing PKS clade II | KsAtAcp/KrAcp/Acp | Synthesis of polyketide similar to citrinin/lovastatin | |

| PKS16 | AAR90270 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 67.9% | KsAtKr | ||||

| EqiS | AAV66106 | F. heterosporum | Yes | 39.8% | KsAtKrAcp/Acp | ||||

| SNOG_08274.2 | KsAcp/AtAcp/Acp | fg12040 | F. graminearum | No | 40.3% | Nonreducing PKS clade II (e.g., melanins) | KsAtAcp | Synthesis of perithecial pigment, autofusarin, or similar polyketide (Graziani et al., 2004) | |

| PKS12 | AAR90248 | B. fuckeliana | No | 44.5% | KsAtAcp/Acp | ||||

| PKS | AAS48892 | N. haematococca | No | 47.8% | KsAtAcp/Acp | ||||

| SNOG_08614.2 | KsAtAcp/Acp/Te | fg12125 | F. graminearum | Yes | 41.2% | Nonreducing PKS clade I | KsAtAcp/Acp | Synthesis of perithecial pigment, cercosporin, or similar polyketide; cercosporin is a reactive oxygen species–generating toxin degrading plant cell membranes (Chung et al., 2003) | |

| PKS3 | AAR92210 | G. moniliformis | No | 49.3% | KsAtAcp/Acp | ||||

| PKS | AAT69682 | C. nicotianae | No | 60.7% | KsAtAcp/Acp | ||||

| SNOG_09623.2 | KsAtAcp/ErKrAcp | fg01790 | F. graminearum | No | 58.9% | Reducing PKS clade IV | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of fumonisin (Proctor et al., 1999) | |

| PKS11 | AAR90266 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 56.1% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| FUM1 | AAD43562 | G. moniliformis | Yes | 57.7% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_11066.2 | KsKsAtErKrAcp | fg12055 | F. graminearum | No | 43.2% | Reducing PKS clade III | KsAtErKrAcp | High virulence; synthesis of T-toxin; zearalenone (Gaffoor et al., 2005; Baker et al., 2006) | |

| PKS8 | AAR90244 | B. fuckeliana | Yes | 59.7% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| PKS2 | ABB76806 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 44.9% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_11076.2 | KsAtDhErKrAcp | fg01790 | F. graminearum | Yes | 62.8% | Reducing PKS clade IV | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of fumonisin (Proctor et al., 1999) | |

| PKS14 | AAR90268 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 82.7% | KsAtDHErKrAcp | ||||

| FUM1 | AAD43562 | G. moniliformis | No | 53.9% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_11272.2 | KsKsAtErKrAcp | fg12055 | F. graminearum | No | 44.7% | Reducing PKS clade IV | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of zearalenone or similar polyketide; similar to HR-type PKS (Gaffoor et al., 2005) | |

| PKS14 | AAR92221 | G. moniliformis | Yes | 48.7% | KsAtErKr | ||||

| PKSKA1 | AAY32931 | Xylaria sp BCC 1067 | No | 47.3% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_11981.2 | KsAtAcp/Acp/Acp/Te | fg12040 | F. graminearum | Yes | 54.9% | Nonreducing PKS clade II | KsAtAcp | Synthesis of melanin (Moriwaki et al., 2004; Amnuaykanjanasin et al., 2005). | |

| PKS18 | AAR90272 | C. heterostrophus | Yes | 85.7% | KsAtAcp/Acp/Te | ||||

| PKS1 | BAD22832 | B. oryzae | Yes | 88.2% | KsAtAcp/Acp/Te | ||||

| SNOG_12897.2 | KsAtErKr | fg10548 | F. graminearum | No | 39.7% | Reducing PKS clade I | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of alternapyrone (Fujii et al., 2005) | |

| PKS5 | AAR92212 | G. moniliformis | No | 38.2% | KsAtAcp/ErKrAcp | ||||

| alt5 | BAD83684 | A. solani | No | 37.8% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_13032.2 | KsAtAcpKr | fg01790 | F. graminearum | No | 40.4% | Reducing PKS clade IV | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of fumonisin (Proctor et al., 1999) | |

| PKS12 | AAR92219 | G. moniliformis | No | 45.1% | KsAtAcp/Acp/ErKrAcp | ||||

| FUM1 | AAD43562 | G. moniliformis | No | 39.1% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_14927.2 | KsAtDhKrAcp | fg01790 | F. graminearum | No | 44.3% | Reducing PKS clade IV | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of diketide moiety of compactin (Abe et al., 2002a, 2002b). | |

| PKS15 | AAR90269 | C. heterostrophus | No | 43.5% | KsAtAcp/ErKrAcp | ||||

| PKS | BAC20566 | P. citrinum | No | 39.1% | KsAtDhErKrAcp | ||||

| SNOG_15829.2 | KsAtAcp | fg12040 | F. graminearum | No | 42.2% | Nonreducing PKS proteins basal to clades I and II (uncharacterized) | KsAtAcp | Synthesis of melanin, autofusarin, or similar polyketide (Moriwaki et al., 2004) | |

| PKS1 | BAD22832 | B. oryzae | No | 41.3% | KsAtAcp/Acp/Te | ||||

| PKS14 | AAR90250 | B. fuckeliana | No | 67.6% | KsAtAcp/Acp | ||||

| SNOG_15965.2 | KsAtErKrAcp | fg10548 | F. graminearum | No | 43.9% | Reducing PKS clade IV | KsAtErKrAcp | Synthesis of fumonisin (Proctor et al., 1999) | |

| PKS10 | AAR90246 | B. fuckeliana | Yes | 68.8% | KsAtErKrAcp | ||||

| PKSKA1 | AAY32931 | Xylaria sp BCC 1067 | No | 54.7% | KsAtErKrAcp |

Domain abbreviations: ACP, acyl-carrier protein domain; At, acetyl transferase; Dh, dehydratase; Er, enoyl reductase; Kr, keto reductase; Ks, keto synthase; Te, thioesterase. Potential orthologs to PKSs C. heterostrophus and F. graminearum (Kroken et al., 2003; Gaffoor et al., 2005) and by best informative hit to the nonredundant database at NCBI of e-value <1 × 10−10. Domain structure and modular organization for all sequences was determined via the online NRPS-PKS database (Ansari et al., 2004). It should be noted that domain structure predictions may vary slightly from those stated in the original studies. Percentage of similarity of ortholog pairs was determined (Needleman and Wunsch, 1970) via NEEDLE (Rice et al., 2000).

A single PKS-NRPS hybrid protein (SNOG_00308.2.) was identified in the genome of S. nodorum as was found for F. graminearum (Gaffoor et al., 2005) and C. heterostrophus (Lee et al., 2005). C. heterostrophus NPS7 and SNOG_00308.2 do not appear to be closely related, and it is likely that they evolved independently. By contrast, the hybrid protein of F. graminearum (Gz FUS1/FG12100) is closely related to SNOG_00308.2. Overall, they are 54.5% similar, and apart from an acyl binding domain found only in SNOG_00308.2, the domain structures are identical. Gz FUS1 produces fusarin C, a mycotoxin (Gaffoor et al., 2005). The best hit (with 59.4% similarity) to SNOG_00308.2 in M. grisea is Ace1, a hybrid PKS/NRPS that confers avirulence to M. grisea during rice (Oryza sativa) infection (Bohnert et al., 2004). It will be intriguing to determine if the product of SNOG_00308.2 is required for pathogenicity.

G-alpha proteins have been extensively studied in fungi (Lafon et al., 2006), and many are required for pathogenicity. Distinct roles for three g-alpha genes have been revealed in M. grisea, A. nidulans, and N. crassa. It was therefore a surprise to find a fourth g-alpha gene in the S. nodorum genome. This gene (SNOG_06158.2) was shown to be expressed in vitro and in planta. It was investigated by gene disruption, and its loss resulted in no discernable phenotype (data not shown). A fourth g-alpha protein has been recently identified in both A. oryzae (Lafon et al., 2006) and Ustilago maydis (Kamper et al., 2006), but neither shows significant sequence similarity to that of S. nodorum. Indeed, SNOG_06158.2 is most similar to Gba3 among the U. maydis g-alphas and GpaB among the A. oryzae genes.

G-alpha proteins transduce extracellular signals leading to infection-specific development (Solomon et al., 2004b). Pth11 and ACI1 are two M. grisea genes encoding transmembrane receptors that defined a new protein domain, CFEM (Kulkarni et al., 2003), with roles in g-protein signaling. M. grisea has nine CFEM domain proteins, and F. graminearum has eight. Using a combination of domain searches and BLAST searches seeded with the M. grisea and F. graminearum genes, we identified six related genes (Table 8). Four of these have at least a weak match to the CFEM domain, but only three are predicted to be transmembrane proteins. SNOG_09610.2 appears to be the ortholog of Pth11 and the F. graminearum gene fg05821, suggesting these genes are ancient and conserved. Pth11 is required for appressorial development and perception of suitable surfaces (DeZwaan et al., 1999). Neither S. nodorum nor F. graminearum form classical appressoria (Solomon et al., 2006b), suggesting that the genes have different functions in these species. SNOG_05942.2 is also closely related to Pth11. Knockout strains for this gene were obtained but had no obvious phenotype (data not shown). SNOG_03589.2 is also related to Pth11 and appears to be a transmembrane protein but lacks the CFEM domain. Both SNOG_08876.2 and SNOG_15007.2 possess CFEM domains and a signal peptide but do not appear to be integral membrane proteins. Knockout strains for SNOG_08876.2 were obtained but revealed no obvious phenotype (data not shown). SNOG_15007.2 is similar to glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored CFEM-containing proteins from three other fungal species. It appears to be heavily expressed both in the oleate and in planta EST libraries with 17 and 27 ESTs, respectively. A clear role for this gene is as yet unknown. CFEM domain proteins are thought to be involved in surface signal perception, and three candidates for this role have been identified. The paucity of such genes in S. nodorum and lack of phenotype associated with deletion of two of them suggests that this function may be covered by a different class of transmembrane receptors.

Table 8.

Potential Orthologs of S. nodorum CFEM Proteins Identified by Matches to PFAM Domain PF05730 and Best Hit to M. grisea and F. graminearum CFEM Proteins

| Best Seeda | Similarity | SN15 CFEM Protein | PF05730 Matcha | Locationb | 7tmc | Informative Best Hit (Nonredundant) | Reciprocal | Similarity | Inferred Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fg08554 | 36.4% | SNOG_02161.2 | No | Extracellular | No | None | Unknown | ||

| SNOG_08876.2 | Yes | Extracellular | No | None | Unknown | ||||

| MGG06724.5 | 21.4% | SNOG_03589.2 | No | Plasma membrane | Yes | AAD30437 M. grisea PTH11 | No | 24.8% | GPCR involved in surface perception |

| MGG05871.5 | 38.3% | SNOG_05942.2 | Yes | Plasma membrane | Yes | AAD30438 M. grisea PTH11 | No | 38.3% | GPCR involved in surface perception |

| MGG10473.5 | 57.5% | SNOG_09610.2 | Yes | Plasma membrane | Yes | AAD30437 M. grisea PTH11 | Yes | 33.1% | GPCR involved in surface perception |

| Fg05821 | Yes | 59.0% | |||||||

| MGG05531.5 | 38.0% | SNOG_15007.2 | Yes | Extracellular | No | ABA33784 Pro-rich antigen- like protein (Paracoccidioides brasiliensis) | Yes | 51.2% | Similar to Pro-rich antigens and Ag2/Pra CRoW domains more commonly identified as immunoreactive antigens of mammalian fungal pathogens (Peng et al., 2002); similar to GPI-anchored CFEM proteins |

| XP_750946.1 GPI-anchored CFEM domain protein (Aspergillus fumigatus Af293) | Yes | 56.6% | |||||||

| AAP84613.1|Ag2/Pra CRoW domain (Coccidioides posadasii) | Yes | 25.7% |

In addition to HMMER matches to PFAM accession PF05730 (using gathering cutoffs), CFEM domain–containing proteins from M. grisea (BROAD release 5: MGG_01149.5, MGG_01872.5, MGG_05531.5, MGG_05871.5, MGG_06724.5, MGG_06755.5, MGG_07005.5, MGG_09570.5, and MGG_10473.5) and Fusarium graminearum (FGDB: fg00588, fg02077, fg02155, fg02374, fg03897, fg05175, fg05821, and fg08554) were used as seeds to identify putative CFEM proteins by their best BLASTP match with an e-value <1 × 10−10 to S. nodorum.

Cellular location was determined with WoLF PSORT (Horton et al., 2007), and the presence of transmembrane-spanning regions (7tm) was determined by consensus between TMHMM (Krogh et al., 2001), TMPRED (Hofmann and Stoffel, 1993), and Phobius (Kall et al., 2004). Best hits of Stagonospora CFEM proteins to the nonredundant protein database at NCBI was determined by informative BLASTP hits of e-value <1 × 10−10 (hits excluding seed and self hits, which are not hypothetical or unknown and preferentially yield useful functional information).

Hydrophobins are small, secreted proteins with eight Cys residues in a conserved pattern that coat the fungal mycelium and spore (Wessels, 1994). Class 2 hydrophobins are restricted to ascomycetes, whereas class 1 hydrophobins are also found in other fungal divisions (Linder et al., 2005). Two class 2 and no class 1 hydrophobin genes were found in the S. nodorum genome (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). This is an unusual example of an ascomycete genome with only class 2 hydrophobin genes. It is interesting to note that although a range of Neurospora species all contained a gene orthologous to the class 1 hydrophobin EAS gene from N. crassa, they were expressed significantly only in species that produced aerial conidia (Winefield et al., 2007). S. nodorum produces pycnidiospores in a gelatinous cirrhus adapted for rain dispersal (Solomon et al., 2006b). It may be that the absence of aerial mitosporulation negates the need for class 1 hydrophobins.

Two rhodopsin-like genes were found in the genome, one of which is similar to the bacteriorhodopsin-like gene found in L. maculans that is a proton pump (Sumii et al., 2005). The likely physiological roles of these genes are currently under investigation.

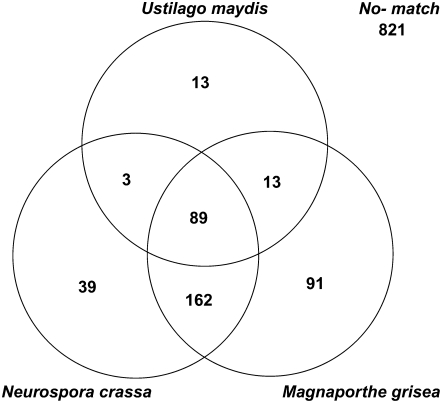

The interaction between a pathogen and its host is to a large extent orchestrated by the proteins that are secreted or localized to the cell wall or cell membrane. Pathogens such as M. grisea, which kill and degrade host tissues, have been shown to secrete large numbers of degradative enzymes (Dean et al., 2005). More surprisingly, the biotrophic pathogen U. maydis was also found to secrete many proteins; many of the genes are clustered, coexpressed, and required for normal pathogenesis but are of unknown molecular functions (Kamper et al., 2006). We have therefore analyzed the putative proteome of S. nodorum for potentially secreted proteins and compared them with these pathogens and the saprobe N. crassa. A total of 1782 proteins was predicted to be extracellular based on predictions using WoLF PSORT; a further 1760 were predicted to be plasma membrane located (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). GO annotations were assigned via Blast2GO for 551 of the putatively extracellular proteins (Table 9). They are dominated by carbohydrate and protein degradation enzymes as would be expected and which is consistent with the EST analysis (see below). The role of many fungal extracellular proteins is currently unknown. Among the S. nodorum predicted extracellular proteins, 1231 had no GO annotation. Of these, only 410 had significant matches to putatively extracellular proteins from U. maydis, M. grisea, or N. crassa (Figure 3). More of these 410 genes had homologs in M. grisea (13 + 91 = 104) than in N. crassa (3 + 39 = 42). As M. grisea and N. crassa are phylogenetically equidistant from S. nodorum, this suggests both that the pathogens secrete more proteins than N. crassa and that the genes are related. Expanding this generalization will require genome analysis of a saprobic dothideomycete. A further 251 genes (89 + 162) had homologs in both M. grisea and N. crassa. Another 118 S. nodorum putatively secreted genes of unknown function had significant similarity to genes encoding the U. maydis secretome, including 13 that uniquely hit the biotrophic basidiomycete. We found no obvious patterns of clustering of any of these secreted genes. The most striking finding was that 821 genes had no significant similarity to predicted extracellular proteins of any of these fully sequenced genomes. These large numbers of putatively secreted proteins of mostly unknown functions, whose genes appear to be rapidly evolving, points to a hitherto unsuspected complexity and subtlety in the interaction between the pathogen and its environments.

Table 9.

The Most Abundant Gene Ontologies Associated with the Predicted Secretome

| GO Identifier | Description | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Biological processes | ||

| GO:0005975 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 42 |

| GO:0008152 | Metabolism | 34 |

| GO:0006118 | Electron transport | 30 |

| GO:0006508 | Proteolysis | 26 |

| GO:0045493 | Xylan catabolism | 19 |

| GO:0044237 | Cellular metabolism | 17 |

| GO:0030245 | Cellulose catabolism | 12 |

| GO:0000272 | Polysaccharide catabolism | 10 |

| Molecular functions | ||

| GO:0003674 | Molecular function | 68 |

| GO:0016491 | Oxidoreductase activity | 52 |

| GO:0016787 | Hydrolase activity | 52 |

| GO:0004553 | Hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds | 48 |

| GO:0005488 | Binding | 34 |

| GO:0003824 | Catalytic activity | 33 |

| GO:0046872 | Metal ion binding | 19 |

| GO:0030248 | Cellulose binding | 18 |

| GO:0016798 | Hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds | 13 |

| GO:0008233 | Peptidase activity | 12 |

| GO:0008810 | Cellulase activity | 12 |

| GO:0016740 | Transferase activity | 12 |

| GO:0016789 | Carboxylic ester hydrolase activity | 10 |

Figure 3.

Homology Relationships of the S. nodorum Secretome.

The 1231 predicted extracellular proteins without GO annotation were compared with the latest releases of the U. maydis, N. crassa, and M. grisea genomes. Counts are best hits of e-value <1e-10 if predicted as extracellular by WoLF PSORT.

One newly recognized aspect of S. nodorum is the production of secreted proteinaceous toxins. SNOG_16571.2 encodes a host-specific protein toxin called ToxA that determines the interaction with the dominant wheat disease susceptibility gene Tsn1 (Friesen et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006). Population genetic evidence suggests that this gene was interspecifically transferred to the wheat tan spot pathogen, P. tritici-repentis, prior to 1941, thereby converting a minor into a major pathogen. An RGD motif that is involved in import into susceptible plant cells is required for activity (Meinhardt et al., 2002; Manning et al., 2004; Manning and Ciuffetti, 2005). Biochemical and genetic evidence suggests that S. nodorum isolates contain several other proteinaceous toxins (Liu et al., 2004a, 2004b). ToxA is a 13.2-kD protein, and current research indicates that the other toxins are also small proteins. Among the predicted extracellular proteins, 840 are <30 kD and 26 have an RGD motif (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). Analysis of these toxin candidates is underway.

Gene Expression during Infection

When analyzed by biological process and molecular function, the in planta EST library was dominated by genes involved in the biosynthesis of proteins and in the degradation and use of extracellular proteins and carbohydrates, specifically cellulose and arabino-xylan (Table 3; see Supplemental Table 5 online). The secretion of proteases (Bindschedler et al., 2003), xylanases, and cellulases suggests that the fungus catabolizes plant proteins and carbohydrates for energy in planta at this late stage of infection. Studies in a range of pathogens suggest that early infection is characterized by the catabolism of internal lipid stores and that mid stages are characterized by the use of external sugars and amino acids (Solomon et al., 2003a). These studies of late infection suggest that polymerized substrates are used after the more easily available substrates are exhausted and provide a novel perspective to in planta nutrition. The abundance of transcripts linked to protein synthesis indicates that this process is very active during this stage of infection and may be related to the massive secretion of degradative enzymes and to the synthesis of proteins needed for sporulation. A similar picture was observed when the genes were analyzed by cellular component (Table 3) with gene products destined for the ribosome dominating. Genes whose products are targeted to the nucleolus and cytoskeleton illustrate the importance of nuclear division and cytokinesis at this stage of infection as many new cell types are elaborated in the developing pycnidium. Thirty-six gene products targeted to the extracellular region include a protease, an α-glucuronidase, and various glucanases consistent with the picture of polymerized substrate breakdown.

Late-stage infection has rarely been examined in plant–fungal interactions, and it is therefore noteworthy that upregulation of transcripts involved in protein synthesis was also observed in late-stage infections of wheat by M. graminicola (Keon et al., 2005). The high rate of protein synthesis may be required for pycnidial biogenesis and may also represent an attractive target for fungicidal intervention.

The oleate EST library was dominated by genes involved in lipid and malate metabolism, the trichloroacetic acid cycle, and electron transport. To determine whether the ratio of ESTs in the in planta and oleate libraries was indicative of early- and late-stage infection, transcript levels from eight candidate genes were determined by a quantitative PCR. The genes were chosen from those found exclusively in the in planta library. Transcripts were quantified in cDNA pools made from RNA isolated from in vitro and in planta growth of SN15 at early and late infection time points. The in vitro cultures sampled at 4 DAI did not contain any pycnidia, whereas cultures sampled at 18 DAI were heavily sporulating with many pycnidia. To isolate RNA from both early and late infections of wheat, an SN15 infection latent period assay was used to provide in planta infection transcripts (Solomon et al., 2003b). Lesions were excised after 8 and 12 DAI, representing early and late infection stages. The three genes most upregulated during growth in planta (SNOG_00557.2, SNOG_03877.2, and SNOG_16499.2) all had >20 in planta ESTs, indicating that the EST frequencies were useful predictors of gene expression at these levels. SNOG_00557.2 was the gene with the highest peak expression level in planta and the largest difference between in vitro and in planta conditions. As the gene is predicted to be an arabinofuranosidase, this reaffirmed the important role of carbohydrolases during colonization of the host tissue. Overall, the four tissue types represented clear states of nonsporulation and sporulation during both in vitro and in planta growth. All the genes were found to be expressed in the 12-DAI infected sample, and this was the highest level observed in all but one case (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). On the other hand, moderate to high levels of gene expression were found in the in vitro samples from six of the eight genes. Attempts to use axenic samples to mimic infection has a long history (Coleman et al., 1997; Talbot et al., 1997; Solomon et al., 2003a; Trail et al., 2003; Thomma et al., 2006). Our data indicate that oleate feeding is not a significantly closer model for infection than starvation has proved to be.

Genome Architecture

Colinearity of gene order is a notable feature of closely related plant and animal genomes but is represented in fungi by a complex pattern of dispersed colinearity, such as observed between Aspergillus spp (Galagan et al., 2005). This low degree of organizational conservation can be attributed to the 200 million year separation of these species and the rarity of meiotic events that would tend to maintain chromosomal integrity. S. nodorum is the first dothideomycete to have its sequence publicly released; thus, the closest species for which whole-genome comparisons could be made are the Aspergilli and N. crassa, which are separated from S. nodorum by ∼400 million years of evolution. Thus far, we have been unable to detect significant regions of colinearity with other sequenced genomes, but it is possible that more sensitive methods and the release of more closely related genome sequences will succeed in revealing patterns of chromosomal level evolution.

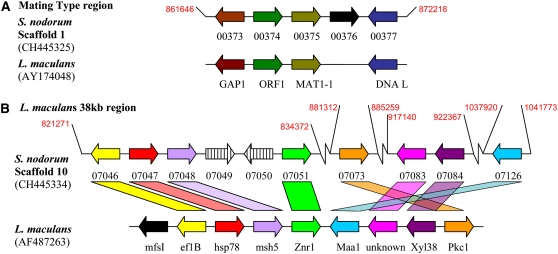

At a smaller scale, the mating type loci of L. maculans, C. heterostrophus, A. alternata, and M. graminicola have been previously analyzed (Cozijnsen and Howlett, 2003). Apart from Mat1-1 and orf1, the only shared genes were a DNA ligase gene found in L. maculans and M. graminicola and Gap1 found in L. maculans and C. heterostrophus. The colinearity between L. maculans and S. nodorum is more complete. Figure 4A shows the relationship of gene order and orientation between these sibling species. It is clear that gene order and orientation are conserved, though the intergenic regions have no discernable relationships. This confirms the close phylogenetic relationship between these species, with S. nodorum closest to L. maculans and more distantly related to C. heterostrophus.

Figure 4.

Colinearity between S. nodorum SN15 and L. maculans Identified by tBLASTX.

(A) Mating-type locus.

(B) A 38-kb region of L. maculans.

Colors indicate an orthologous relationship between genes, whereas black indicates no relationship. Numbers in red give coordinates on the S. nodorum scaffolds.

There is tantalizing evidence of residual colinearity of the genes present in a contiguous 38-kb region of L. maculans DNA (Idnurm et al., 2003). Six of the nine L. maculans genes have orthologs within a 200-kb region of S. nodorum DNA. Gene orientation is retained, but they are interspersed with ∼60 other predicted genes (Figure 4B).

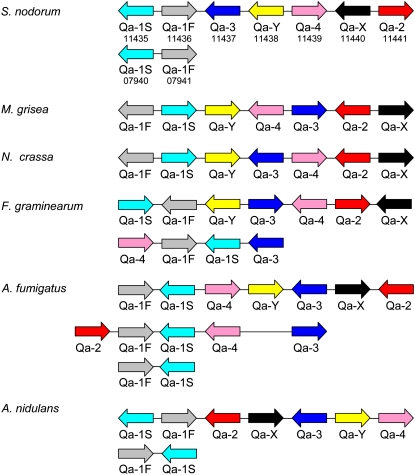

A different pattern of colinearity is apparent in the quinate gene cluster. The quinate genes regulate the catabolism of quinate and have a wide distribution in filamentous fungi (Giles et al., 1991). The cluster comprises seven coregulated genes. In some cases, portions of the cluster are repeated at other genomic locations. In S. nodorum, the main cluster is located on scaffold 19 with two genes on scaffold 12. Figure 5 show the relationship of gene content and order in six fungal species. As the species for comparison span 400 million years of evolution, it is apparent that clustering of these genes per se is highly conserved. However, the gene order and orientation shows no conservation apart from the constant juxtaposition of homologs of Qa-1S and Qa1-F and of Qa-X and Qa-2. Even in these cases, though, some are 5′ to 5′ and others are 3′ to 3′. It appears, therefore, that there must be selection for retention of clustering of these seven genes, even if the exact orientation may not be so important. It may be that such proximity clustering is important in that it enables gene regulation by chromatin remodeling mediated by a gene such as LaeA (Bok and Keller, 2004). SNOG_11365.2 is an apparent ortholog of LaeA.

Figure 5.

Organization of the Quinate Cluster from Several Sequenced Fungal Genomes.

Numbers under the S. nodorum genes refer to the SNOG identifiers. The S. nodorum genes are located on scaffolds 19 and 12, respectively.

Fungi have a truly ancient history, many times longer than that of animals and flowering plants (Padovan et al., 2005). The extent of genetic diversity is correspondingly large. Phylogenetic analysis of fungi has been hampered by a paucity of reliable morphological indicators. As a consequence, phylogenetic reconstruction of the fungi has been particularly unstable until the widespread introduction of multigene-based DNA sequence comparisons. This study confirms the overall monophyletic characters of the Dothideomycetes and the Pleosporales taxa. These groups contain many thousands of species and are notable for their content of major plant pathogens infecting many important plant families. The origins of this class, likely >400 million years ago, is considerably older than their plant hosts. It is particularly interesting to note that all the fungal plant pathogens that are well established as host-specific toxin producers are in this class (Stagonospora, Cochliobolus, Pyrenophora, M. zeae-maydis, and Alternaria). Taken as a whole, the pathogens in this class are mainly described as necrotrophic, while a few are debatably described as biotrophic (Venturia and C. fulvum) or hemibiotrophic (L. maculans, M. graminicola, and M. fijiensis). None of the species in this class are obligate pathogens, and none possess classical haustoria (Oliver and Ipcho, 2004); furthermore, many other species are nonpathogenic. The genome sequence of S. nodorum represents an important point of comparison from which to derive hypotheses about the genetic basis of pathogenicity in these organisms. Genome sequences of several of these species are in progress (Goodwin, 2004), including A. brassicicola, M. fijiensis, M. graminicola, L. maculans, and P. tritici-repentis, or have been completed but not released (C. heterostrophus; Catlett et al., 2003). Three of these species, S. nodorum, M. graminicola, and P. tritici-repentis, are wheat pathogens. The possibility of multiple pairwise comparisons of gene content between phylogenetically and ecologically close species promises to be a powerful method to derive workably small lists of candidate effector genes controlling pathogenicity, host specificity, and life cycle characters and thus provide ideas for the generation of novel crop protection strategies. The genome sequence provides the tools for global transcriptome analysis, thereby identifying the genes expressed during different phases of infection. This study has also highlighted secreted proteins, which appear to be markedly more numerous than in nonpathogens but which have predominately mysterious roles. Finally, the genome sequence is an essential prerequisite for the critical analysis of hypotheses of interspecific gene transfer. This has already been identified in pathogens in general (Richards et al., 2006) and S. nodorum in particular (Friesen et al., 2006; Stukenbrock and McDonald, 2007) and may emerge as a major feature in the evolution of these organisms.

METHODS

Fungal Strains

Stagonospora nodorum strain SN15 (Solomon et al., 2003b) was used for both genome and EST libraries and has been deposited at the Fungal Genetics Stock Center. The genome sequence was obtained as described (http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/stagonospora_nodorum/Assembly.html). The sequences are available for download from GenBank under accession number AAGI00000000.

Phylogenetic Analysis

A combined matrix of 41 taxa was generated from DNA sequences obtained from two ribosomal (nuclear large and small subunit [nuc-LSU and nuc-SSU]) and three protein genes (elongation factor 1 α [EF-1α] and the largest and second largest subunits of RNA polymerase II [RPB1 and RPB2]). Data were obtained from the Assembling the Fungal Tree of Life (AFTOL; www.aftol.org) and GenBank sequence databases, which aligned in ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997) and manually improved where necessary. After introns and ambiguously aligned characters were excluded, 6694 bp were used in the final analyses. In some cases, genes were missing (see Supplemental Table 3 and Supplemental Data Set 3 online). The resulting data were combined and delimited into 11 partitions, including nuc-SSU, nuc-LSU, and the first, second, and third codon positions of EF-1α, RPB1, and RPB2, with unique models applied to each partition. Metropolis coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo analyses were conducted using MrBayes 3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001) with a six-parameter model of evolution (generalized time reversible) (Rodriguez et al., 1990) and gamma distribution approximated with four categories and a proportion of invariable sites. Trees were sampled every 100th generation for 5,000,000 generations. Three runs were completed to ensure that stationarity was reached, and 5000 trees were discarded as “burn in” for each. Posterior probabilities were determined by calculating a 50% majority-rule consensus tree of 45,000 trees from a single run. Maximum likelihood bootstrap proportions were calculated by doing 1000 replicates in RAxML-VI-HPC (Stamatakis, 2006) with the GTRCAT model approximation and 25 rate categories with the same data partitions as for the Bayesian runs.

Repetitive Elements

Repetitive elements were identified de novo using RepeatScout v1.0.0 (Price et al., 2005) with a minimum threshold of 10 matches and a minimum repeat length of 200 bp. Newly generated repeats were aligned to the genome assembly via BLASTN v2.0 (Altschul et al., 1990). Hits were discarded if sequence identity fell below 35% or alignment length was <200 bp. For each repeat, the number of filtered hits was counted, and repeats were discarded if the number of hits to the assembly was <10. Prototype repeat regions were defined by identification of sequence similarities among themselves via BLASTN and deletion of redundant repeat sequence. Regions of the genome assembly that matched to a repeat were aligned using MUSCLE v3.6 (Edgar, 2004). To identify repeat type and function, repeats were compared with the nonredundant sequence database hosted by NCBI via BLASTN/BLASTX, and subrepeat regions within repeats were also analyzed. Tandem repeats were identified using Tandem Repeat Finder (Benson, 1999), direct repeats were identified via MegaBLAST (Zhang et al., 2000), and inverted repeats were identified using both MegaBLAST and eINVERTED (Rice et al., 2000).

Putative telomeric regions were predicted by considering scaffold ends containing successive repetitive elements without interspersed predicted protein coding genes. The occurrence of repeat classes within these regions was counted and compared with occurrences throughout the genome. Where >85% of the repeats were found to be at nongenic scaffold end regions, these classes were classified as telomeric repeats. The scaffold ends were predicted to be physical telomeres if they contained three or more telomeric repeats.

To analyze and compare the prevalence of RIP mutation, we developed a program to compare RIP mutations between multiple sequences (J.K. Hane and R.P. Oliver, unpublished data). RIPCAL compares the aligned sequences against a designated model sequence (in this case the trimmed de novo repeats) and was configured to calculate RIP (Dean et al., 2005).

Gene Content

An automated genome annotation was initially created using the Calhoun annotation system. A combination of gene prediction programs, FGENESH, FGENESH+, and GENEID, and 317 manually curated transcripts were used. GENEWISE was used with non-species specific parameters to predict genes from proteins identified by BLASTX. To refine the initial genome annotation, a further 10,752 EST reads were obtained from an EST library from oleate-grown mycelium and 10,751 from S. nodorum–infected wheat (see below for details). These EST sequences were screened against a library of wheat ESTs, trimmed for vector sequence manually, for poly(A) tail sequence using TrimEST (Rice et al., 2000), screened for unusable sequences of poor quality, filtered for remaining sequence of ≥50 bp, and aligned to the genome assembly using Sim4 (Florea et al., 1998). ESTs with multiple genomic locations were assigned their optimum location based on percent identity, total alignment length, and best location of the EST mated pair. Gene models were manually annotated according to optimum EST alignments using Apollo (Lewis et al., 2002).

Genes that were fully supported by EST data were used to train the gene prediction program UNVEIL (Majoros et al., 2003). Second-round gene annotations were created by combining gene predictions with EST data, with EST data replacing predicted gene models, and UNVEIL predictions preferred over first-round predictions. Genes with coding regions <50 amino acids were discarded. The numerical identifiers assigned during the first-round predictions have been retained. New gene models were assigned loci from 20,000 onwards. Updated loci (UNVEIL and EST supported) have been given the numerical suffix 2 (e.g., SNOG_16571.2). The 5354 unsupported genes have retained the numerical identifiers and suffix 1. Where genic regions lack EST support, only the coding sequence is reported.