Abstract

Recent advances in the replication field have highlighted how the replication initiator proteins are negatively regulated by inhibitor proteins and ubiquitin-mediated degradation in mammalian cells to prevent rereplication. When these regulatory pathways go awry, uncontrolled rereplication ensues and a G2/M checkpoint is evoked to prevent cellular death. Many components of the checkpoints activated by rereplicaton are important for cancer prevention by facilitating DNA damage repair processes. The pathways that prevent rereplication themselves have also recently been implicated in preventing tumorigenesis. Studies from patient tumors, genetically altered mice, and mammalian cell culture suggest that deregulation of replication licensing proteins results in an increase in aneuploidy, chromosomal fusions, and DNA breaks. These studies provide a framework to address how regulators of replication function to maintain genomic stability.

Introduction

Duplication of chromosomal DNA is a key event in the cell cycle. In eukaryotes, DNA replication initiates at areas known as replication origins, which are recognized by a six-subunit ATPase complex called the origin recognition complex (ORC) [1]. This complex binds DNA in late mitosis or early G1 synergistically with a second AAA+-ATPase, Cdc6 [1,2]. The replication licensing factor, Cdt1 then recruits the MCM2-7 complex, the likely replicative DNA helicase, to the replication origins in a manner dependent on concerted ATP hydrolysis by Cdc6 and ORC subunits [3] to form the prereplicative complex (pre-RC) at the licensed origin. Subsequent replication initiation depends on activation of the helicase activity of MCM2-7 directly or indirectly by cdk2 (cyclin dependent kinase 2) and DDK (Dbf4 and Drf1-dependent kinase) [1] (figure 1 middle). It is important that replication initiation happens once and only once per cell cycle. To ensure this, cells inactivate the processes for pre-RC formation once S phase is initiated to prevent re-licensing and re-initiation. In doing so, rereplication within the same cell cycle is prevented. After mitosis, the pre-RC machinery is de-repressed so that origins can be licensed again for the next cell cycle.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms to prevent rereplication in mammalian cells. In the center is the pre-RC which is a pre-requisite for replication initiation. The pathways highlighted with black lines are known to inhibit pre-RC formation and by doing so have been demonstrated to prevent rereplication. The pathways denoted with dashed lines also inhibit pre-RC formation but have not yet been shown to prevent rereplication. The red lightening blot denotes pathways activated by DNA damage. The boxed section shows Emi1 which has been shown to prevent rereplication by stabilizing geminin and cyclinA.

In this review, we will focus on the newest advances in our understanding of the mechanisms and consequences of rereplication, ways mammalian cells try to prevent rereplication, and how rereplication is related to tumor formation.

Ways to Induce Rereplication

In various experimental organisms, the array of mechanisms to inhibit rereplication is somewhat different, and hence disruption of the regulatory pathways to induce rereplication also varies. In yeast, cdk2-dependent suppression of individual pre-RC components is the main mechanism to prevent rereplication [4]. However, in higher eukaryotes, including mammals, other cdk-independent pathways have been reported to suppress rereplication. In mammals, Cdt1 is the major target that is repressed once cells enter S phase for the prevention of re-licensing, although Cdc6 and ORC are also regulated [5,6]. Overexpression of Cdt1 itself or with Cdc6 causes rereplication in p53-/- human cancer cells [7]. This is in contrast to the yeasts, where the overexpression of Cdc18 (the ortholog of Cdc6) but not Cdt1 is sufficient to override the control of DNA replication in fission yeast, whereas simultaneous deregulation of the four pre-RC components are required to induce immense rereplication in budding yeast [5,8].

To repress Cdt1 after the onset of S phase, mammalian cells have developed multiple mechanisms, which include association with the inhibitor, Geminin, and degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome system by two distinct E3 ligases - SCFSkp2 (which is cdk dependent) and Cul4-DDB1Cdt2 (see figure 2) [4,6]. Depletion of the Cdt1 inhibitor, geminin, leads to DNA rereplication in Drosophila and certain human cancer cell lines [5]. However, in other human cell lines like HeLa or MCF10A, in Xenopus egg extracts, and in C. elegans loss of geminin does not induce rereplication. In contrast, Cdt2 depletion at least in HeLa cells, stabilizes Cdt1 levels in G2 phase and induces robust rereplication [9]. Similarly, Cul4 depletion in C. elegans [10] and a non-degradable Cdt1 overexpression in Xenopus [11] lead to rereplication. Thus, geminin and Cdt1 degradation mechanisms down regulate Cdt1 activity to differing extents in different experimental systems.

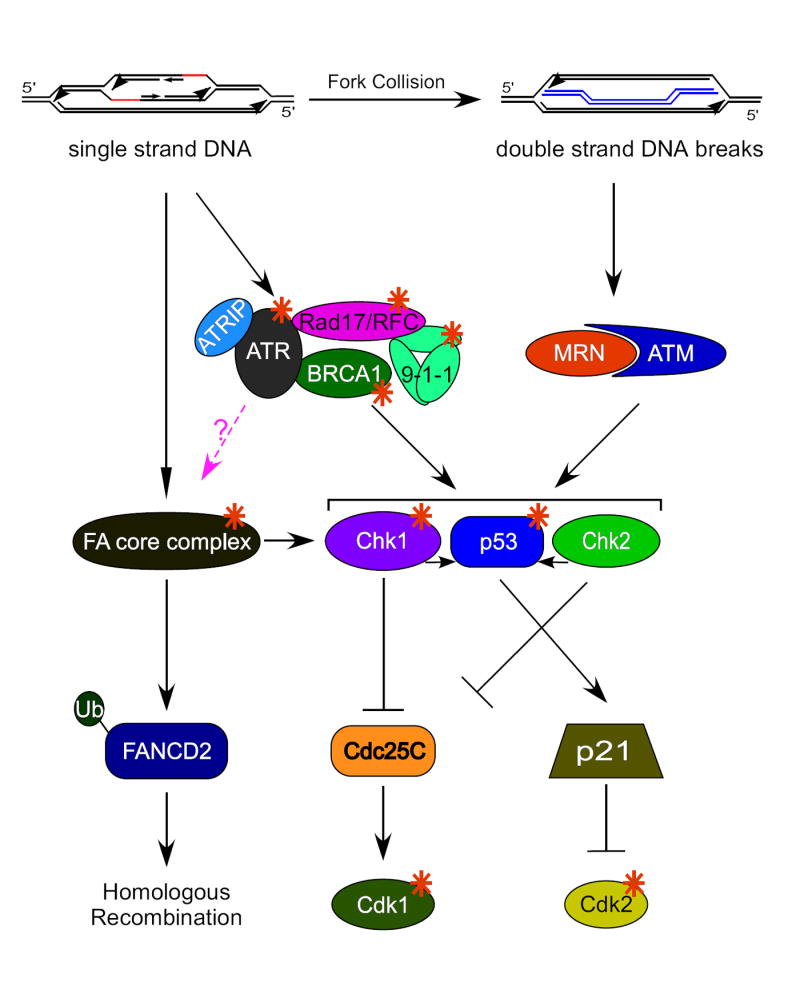

Figure 2.

Checkpoints activated upon rereplication. Multiple rounds of replication could give rise to replication origins within replication bubbles which would activate ATR-dependent signaling pathways. Replication fork collision could generate DNA double strand breaks and activate ATM-dependent pathways. Orange stars denote proteins essential for checkpoint activation in response to rereplication. The pink dashed line denotes a hypothetical pathway. The 9-1-1 complex is composed of Rad9-Rad1-Hus1. The MRN complex is made up of Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1.

Although the primary mechanism to induce rereplication in mammalian cells might be through regulating Cdt1, some mammalian cells like their yeast counterparts, continue to repress rereplication through the activity of cdk2/cyclinA. Recently, the depletion of Emi1, an inhibitor of anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) activity during S and G2 phases, has been reported to cause rereplication in HeLa and a non-malignant breast epithelial cell line MCF10A [12]. APC activation leads to the degradation of geminin, cyclin A, and cyclin B1 which in turn induces rereplication through Cdt1 activation and inactivation of cdk2/cyclinA and cdk1/cyclinB1 [12,13].

Mechanisms and Consequences of Rereplication

Regardless of the exact mechanism of inducing rereplication, the manner by which it happens has not been well studied. So far, many researchers rely on detecting rereplication using FACS (Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting) analysis of cells. In order for cells to display rereplication by FACS analysis, the majority of the cells need to contain significant amounts of rereplicated DNA. This fact led researchers to turn to either comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) anaysis, pulse gel electrophoresis, heavy/heavy DNA labeling, or FISH (Fluorescence In-Situ Hybridization) analysis to measure rereplication on a smaller, more precise scale.

Many have postulated that rereplication occurs primarily though ad-hoc reinititation at sites previously replicated and not due to a co-ordinated single round of rereplication since FACS profiles show the appearance of cells where the DNA content is increased beyond 4N in a broad range of ploidy and not as a discrete peak at 8N (for review see [14]). The ad-hoc reinititation is induced by either overexpression of licensing factors, such as Cdt1 and Cdc6, or by depletion of inhibitors of licensing such as geminin and Emi1. Overexpression of Cdt1 with Cdc6 causes rereplication preferentially at early firing origins at only 2-4 hours after an initial firing in S phase [7]. Recent studies have illustrated that even if only a fraction of the genome is rereplicated, the same origin can fire many times, and latent origins begin firing [15-17]. Although relicencing might be a major contributor to rereplication, it seems in S. cerevisiae that pre-RC formation alone is not sufficient to induce rereplication [15]. Perhaps this observation correlates with an older study using minichromosomes that showed that rereplication can be blocked during elongation [18]. The mechanism of this latter observation and whether this phenomenon exists in mammalian cells is unclear.

One of the major consequences of rereplication is the activation of DNA damage checkpoints [8]. Rereplication activates the serine/threonine kinases, ATR (ATM and Rad3-related) and ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated). These kinases phosphorylate and activate substrate kinases, chk1 and chk2 to evoke a G2/M cell cycle block (figure 2). Chk1 and chk2 in turn phosphorylate and inactivate cdc25C, the major phosphatase responsible for activating mitotic cdk1/cyclinB. If rereplication is induced while members of these checkpoint pathways are knocked-down by siRNA techniques, cells die due to their failure to arrest before mitosis. Viability and accumulation of cells with extensively rereplicated DNA is restored by an artificial G2 block [19]. The approach of co-depleting geminin with potential mediators of the G2/M checkpoint has been useful to establish that proteins such as Fanconi Anemia (FA) proteins, BRCA1, p53, etc. are important to establish the checkpoint in response to rereplication. Recent elegant work by Julian Blow’s group shows that uncontrolled rereplication is necessary for checkpoint activation and that a single co-ordinated round of rereplication in G2/M is not sufficient to elicit a checkpoint response. Additionally, they show that rereplication results in head to tail fork collision and generation of small double stranded fragments of rereplicated DNA [17]. Thus, the G2/M checkpoint is activated by rereplication to halt the cell cycle and prevent cells from mitotic catastrophe.

Mechanisms to prevent re-replication

Since global rereplication can be deleterious to a cell’s survival, there are several mechamisms in play to prevent rereplication. So far in mammalian cells the majority of these mechanisms impinge on the regulation of the replication inititation proteins, Cdt1 and Cdc6.

As mentioned above, Cdt1 is negatively regulated both by geminin and by proteolytic degradation. After cells initiate DNA replication in late G1, APC is inactivated and as a consequence its substrates such as geminin accumulate. Geminin binds to Cdt1 and inhibits its activity till late M phase [5], when APC gets activated and degrades geminin. To remove excess Cdt1 and prevent origin re-firing, cells have developed pathways for Cdt1 degradation. After the G1/S transition, Cdt1 associates with cyclin A through a cyclin binding (Cy motif) and gets phosphorylated by cdk2 on T29. Phospho-Cdt1 binds to Skp2 and is targeted for destruction via SCFSkp2 E3 ubiquitin ligase during the S to M cell cycle transition [6] (figure 1). Surprisingly however, Cdt1 mutants incapable of being phosphorylated by cdk2/cyclin A and of binding to Skp2 are still degraded in S phase [6]. This conundrum wasn’t resolved until recently when a new mechamism for Cdt1 degradation depending on the Cul4-DDB1Cdt2 ubiquitin ligase was characterized [9,11,20-25]. During DNA replication or after DNA damage (like UV irradiation), Cdt1 interacts with chromatin-bound proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) through its conserved N-terminal PCNA interaction motif (PIP box) (figure 1). The interaction is required for the subsequent recognition of Cdt1 by Cul4-DDB1Cdt2, which ubiquitinates and promotes the degradation of Cdt1. Cdt2/L2DTL was discovered to be essential for the proteolysis probably through functioning as a substrate receptor interposed between the Cdt1 substrate and the Cul4-DDB1 enzymatic complex. Thus, in mammals there are two redundant pathways for degradation Cdt1 once cells enter S phase.

Although there is considerable evidence in yeast that ORC and especially Cdc6 are important to prevent rereplication, their role in mammalian cells is not clear [5]. Some evidence in mammalian cells suggested these proteins were negatively regulated after replication initiation, but elimination of this regulation was not sufficient to induce DNA rereplication [4,5]. Overexpression of Cdc6, however, may have important implications for tumor formation by a mechanism independent of replication control (see below).

Rereplication and Tumorigenesis

Clearly, rereplication elicits a DNA damage response and many of the signaling proteins involved in these responses have been mutated or deleted in a variety of types of cancers [26,27].) In this section, however, we will focus on the current knowledge concerning the players important in regulating rereplication and their potential involvement in tumor formation.

In many types of mammalian cells, Cdt1 overexpression alone can cause rereplication which is augmented by Cdc6 overexpression. Interestingly, upregulation of these two proteins is also seen in several models of tumorigenesis. For example, elevated levels of Cdt1 and/or Cdc6 are seen in tumors and in tumor-derived cell lines [28-31] and NIH3T3 cells overexpressing Cdt1 cause tumors when injected into immunecompromised mice [28]. In addition, transgenic mice overexpressing Cdt1 in T cells develop thymic lymphoblastic lymphomas when p53 is deleted [32]. Although it is possible that overexpression of Cdt1 and/or Cdc6 in human tumors is a side effect of increased proliferative capacity, no correlation was noted between expression levels of either Cdt1 [31] or Cdc6 [29] and the proliferation marker, Ki-67.

A major mechanism by which tumors arise is genomic instability. Not only does overexpression of Cdt1 cause tumors, recent data suggests that Cdt1 may be doing so by inducing genomic instability. Over 50% of all human cancers contain mutations in the tumor suppressor gene p53. Deletion of p53 may synergize with overexpression of Cdt1 and Cdc6 to cause genomic instability in non-small cell carcinomas [31]. In addition, thymocytes from Cdt1 transgenic mice (also null for p53) had enhanced aneuploidy compared to p53-/- control thymocytes. Although some of the thymocytes from transgenic mice contained the usual 40 chromosomes, the vast majority contained between 49 to 58 [32]. Genomic instability stimulated by Cdt1 overexpression, however, is not completely dependent on p53 since in normal human fibroblasts where p53 is wildtype, Cdt1 overexpression still results in a large percentage of cells with aneuploidy [30]. Likewise, tumor cells from mice transplanted with Cdt1 overexpressing cells [28] also show aneuploidy as well as end-to-end chromosome fusions, chromosome gaps and breaks [32]. Since Cdt1 overexpression results in genomic instability, one could imagine that down-regulation of negative regulators of Cdt1, such as the Cul4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase complex would also cause genomic instability. Indeed, DDB1 siRNA causes a significant increase in chromosomal breaks [33]. In fact, it may be the balance of the replication initiator proteins, Cdt1 and Cdc6 relative to the levels of the replication inhibitor, geminin, that is crucial during tumorigenesis. For example, a subset of patients with mantle cell lymphomas had a “deregulated licensing signature,” that is high Cdt1 and Cdc6 with low geminin levels. These patients had an increase in chromosomal alterations by CGH analysis and ultimately a shorter median overall survival [34].

Although increased levels of Cdt1 and Cdc6 facilitate re-initiation of replication origins, recent papers suggest that some of their ability to promote genomic instability may not be dependent on their replicative functions. In quiescent cells, Cdt1 overexpression in either rat or human fibroblasts results in chromosomal gains or losses without any detectable rereplication [30]. In addition, increased Cdt1 induced by DDB1 siRNA, induced chromosomal breaks in regions that did not correlate to known fragile sites that are often broken during replication stress [33]. The most intriguing argument for replication initiators inducing genomic instability by a novel mechanism comes from the observation that Cdc6 can be recruited to the INK4/ARF tumor suppressor locus, recruit histone deacetylases, and stimulate heterochromatinization [29]. This observation might explain why tumors that contain high levels of Cdc6 often also repress the three tumor suppressors, p15INK4b, ARF, and p16INK4a, which are all transcribed from this locus [29].

Elevated levels of Cdc6 in tumors suggests that Cdc6 degradation might be an important barrier to tumor formation. Cells use at least two different ubiquitin ligases to degrade Cdc6. It was known that during early G1 Cdc6 can be degraded by APCCdh1 [35]. Recently, this work has been extended to show that cdk2 promotes pre-RC formation by phosphorylating ser54 of Cdc6 which prevents degradation by APC [36,37]. In addition, ionizing radiation activates APC-mediated degradation of Cdc6 through p53 inhibition of cdk2, possibly through transcriptional induction of the cdk inhibitor, p21 [37]. DNA damage stimulates Cdc6 degradation by a second mechanism which is p53, APC, and cell cycle-independent. Huwe1 (also known as Mule/UreB1/ARFBP1/Lasu1/HectH9) a HECT domain ubiquitin E3 ligase associates with chromatin bound Cdc6 and facilitates degradation after cells are exposed to UV or DNA alkylation [38] (figure 1). The use of different E3 ligases in response to differing forms of DNA damage may have to do with whether ATR (UV or alkylation) or ATM (ionizing radation) is the primary signal transducer. In addition, to ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, Cdc6 is also cleaved by caspase-3 in early apoptosis after DNA damage [39] or cancer drug therapy [40]. Despite so many mechanisms by which to reduce Cdc6 levels it is unclear whether elevated Cdc6 in tumors is the cause or effect of increased cell proliferation.

Outstanding Questions in the Field

Cells employ several mechanisms as barriers to tumorigenesis, including but not limited to cell cycle checkpoints and oncogene induced senescence. Two exciting papers have recently suggested that DNA damage checkpoint pathways are required for oncogenes to induce senescence as an adaptive cellular mechanism to slow the progression of preneoplastic lesions to neoplasias [41,42]. These groups show that oncogenes induce repeated origin firing, asymmetric fork progression, pre-mature fork termination, and double strand DNA breaks. As a result of this replication stress, the ATR/ATM checkpoint pathways are activated. Inactivation of the checkpoints by ATM shRNA, chk2 shRNA, or p53 shRNA (a substrate for both ATM and chk2), abrogated oncogene mediated senescence [41,42] and promoted transformation and tumor growth [42]. The model from these studies is that oncogenes induce replication stress and cells respond with DNA damage checkpoint activation and subsequent senescence. Interestingly, overexpression of both the oncogenes used in these studies, mos and ras, caused increases in Cdc6 protein levels, an effect which would facilitate rereplication or suppress the ARF/INK4 tumor suppressor locus. One could hypothesize that since rereplication also activates DNA damage checkpoints, rereplication might also induce senescence.

The implication from these two studies is that after the initital checkpoint activation, some cells are able to “escape” senescence and it is these cells that go on to form the malignant neoplasias that are so deleterious for an organism. The question then arises, “How do cells escape senescence?” Perhaps it is through additional gene alterations. Over 25 years ago it was proposed that replication stress (or possibly rereplication) is a mechanism for gene amplification [43]). Although this idea is an attractive one, currently, there is no solid data for this idea. In theory, origin re-firing in a short space of time could result in the second fork catching up the initial origin and the generation of a double strand break [17]. If this break is repaired by homologous recombination, as has been postulated as the means to repair replication induced breaks [44], one could imagine that all three copies of the replicated region might be spared [17]. Of course this is only theoretical as it is not clear how the cell would try to repair DNA damage caused by the collision of replication forks. Many genes known to be important for cancer prevention and implicated in the cell’s response to rereplication are also required for repair of DNA breaks. The MRN complex which is important for chk2 activation during rereplication (Lin and Dutta, in press) is crucial for double strand break repair to keep the DNA ends in close proximity to one another. BRCA1, a protein required for the G2/M checkpoint pathway activated by rereplication, also functions as part of the homologous recombination machinery (figure 2). Studies are just being published that suggest that defects in components of the G2/M checkpoint activated in response to rereplication give rise to gene amplification in breast cancer [45,46]. Future research should shed light on the long standing question of whether rereplication indeed results in gene amplification.

Somewhat surprisingly, there have not been mutations or alterations identified in the core components of the pre-RC in human cancers. Although loss of function alterations would be incompatible with cellular survival the same cannot be said for gain of function mutations that could lead to rereplication. High Cdt1 levels correlate with tumorigenesis but mutations that increase Cdt1 activity have not been identified. One could hypothesize that the levels of geminin, an inhibitor, might be low in cancers. There have been reports, however, that show that in 49% of small cell lung carcinomas, geminin levels are dramatically changed, but counterintuitively, only 12% of the tumors have decreased geminin whereas 37% have increased geminin [31]. It is unclear whether these differences in geminin levels are seen on a per cell basis or are merely an indirect consequence of an altered cell cycle profile. Additionally, it could be that geminin levels are high in low grade tumors and as the grade increases, geminin levels become low. So far, no comprehensive studies have been done that correlate the expression of components of the replication machinery with tumor grade.

Although many groups have been studying how geminin is degraded to facilitate rereplication, another possibility is that geminin is regulated through changes in subcellular localization. It has been shown that at the end of mitosis avian geminin can be exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm to facilitate MCM loading [47]. It remains possible that during tumorigenesis, geminin is mislocalized and cannot function to restrain replication origin firing.

To date, there is no indication that elevated levels of the MCM complex components promote rereplication. However, several studies indicate that the MCM complex might be a target of negative regulation during rereplication. First, MCM subunits 2, 3, and 7 are phosphorylated by ATR in response to replication stress [48]. Second, rereplication can be blocked during elongation [18] and the MCM complex is required for elongation [8]. In budding yeast, the MCM subunits are also subject to nuclear export in response to cdk activity to prevent pre-RC formation [8]. Thus, whether excess MCM activity will affect rereplication and whether this might impact tumorigenesis remains to be elucidated.

Finally, an outstanding question is how a cell distinguishes between developmentally regulated, beneficial endoreduplication and aberrant rereplication? Two types of mammalian cells, megakarocytes and trophoblastic cells are able to undergo endoreduplication (also called endomitosis) or duplication of the entire genome successive times without transversing the G2/M transition. Trophoblast cells, essential for placental development and the barrier between material and fetal tissues, undergo concomitant differentiation, endoreduplication to reach 512-1024 N DNA content, as well as invasion into the endometrium [49]. Megakaryocytes on the other hand, go through several rounds of endoreplication (to 128 N) as a transition from a megakaryocyte progenitor to a terminally differentiated megakaryocyte capable of forming platelets [50].

Until recently, it was unclear whether replication proteins themselves were key regulators of endoreduplication. Laskey’s group has shown that in geminin knock-out mice, cells commit to the trophoblastic lineage and begin undergoing premature endoreduplication at the 8 cell stage [51]. In addition, they found that normally geminin is degraded during trophoblast endoreduplication, indicating that a similar mechanism prevents both rereplication and endoreduplication [51]. In megakaryoblastic cell lines able to undergo differentiation-induced endoreduplication, geminin levels go down [52,53]. Cyclin E overexpression stabilizes Cdc6 levels (probably through cdk2) and Cdc6 overexpression in the absence of megakaryocyte differentiation can cause cells to endoreduplicate [52]. Since inhibition of cdk1/cyclinB1 activity promotes endoreduplication in both trophoblastic cells and megakaryocytes [49,50], it is tempting to speculate that Emi1 depletion which causes degradation of cyclin B1 [13], might also facilitate endoreduplication. From these limited studies it appears that the mechanisms to limit rereplication might also act to inhibit endoreduplication. The key to whether a cell endoreduplicates would not only depend on pathways that prevent rereplication but would also depend on the concerted context of the differentiation program that is initiated, the signal transduction pathways activated, the gene expression changes, and the extracellular signaling environment.

Conclusions

The balance between levels of the inititation factors, Cdt1 and Cdc6, and their negative regulators is crucial in determining whether cells will rereplicate their DNA. High Cdt1 and/or high Cdc6 promote rereplication as seen in various tumor models, and correlate with genomic instability. In contrast, depletion of the Cdt1 inhibitor, geminin induces rereplication although a role in tumor formation is not well established. The major recent advance in understanding how cells prevent rereplication has been in elucidating the pathways that regulate the degradation of Cdt1 and Cdc6. Cdt1 is targeted for destruction by skp2 and Cul4-DDB1, whereas Cdc6 is regulated by HUWE1 and APC. Now that techniques to visualize replication foci in live cells [54] and crystallographic and proteometric analysis of the ligase complexes [9,55-57] are being published, our arsenal with which to study rereplication is rapidly increasing. The recent expanse in knowledge of how the replication initiation pathways are controlled has revealed that cells use diverse, distinct and precise mechanisms to prevent rereplication. By employing such mechanisms, cells control tumorigenesis by increasing the fidelity with which genomes are passed to daughter cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to those whose primary work has not been sited due to space limitations. Work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by NIH grant CA60499 to A. D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sara S. Hook, Email: hook@virginia.edu.

Jie Jessie Lin, Email: jl9sj@virginia.edu.

References

- 1.Bell SP, Dutta A. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:333–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lei M, Tye BK. Initiating DNA synthesis: from recruiting to activating the MCM complex. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1447–1454. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.8.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randell JC, Bowers JL, Rodriguez HK, Bell SP. Sequential ATP hydrolysis by Cdc6 and ORC directs loading of the Mcm2-7 helicase. Mol Cell. 2006;21:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machida YJ, Hamlin JL, Dutta A. Right place, right time, and only once: replication initiation in metazoans. Cell. 2005;123:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias EE, Walter JC. Strength in numbers: preventing rereplication via multiple mechanisms in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:497–518. doi: 10.1101/gad.1508907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim Y, Kipreos ET. Cdt1 degradation to prevent DNA re-replication: conserved and non-conserved pathways. Cell Div. 2007;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaziri C, Saxena S, Jeon Y, Lee C, Murata K, Machida Y, Wagle N, Hwang DS, Dutta A. A p53-dependent checkpoint pathway prevents rereplication. Mol Cell. 2003;11:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blow JJ, Dutta A. Preventing re-replication of chromosomal DNA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:476–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •9.Jin J, Arias EE, Chen J, Harper JW, Walter JC. A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol Cell. 2006;23:709–721. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.010. This paper, along with references 23 and 25, shows that the Cul4-DDB1 E3 complex utilizes the adapter Cdt2 to degrade Cdt1.These authors identify Cul4-DDB1 interacting proteins and show that Cdt2 in human cells and X. laevis extracts is important to degrade Cdt1 during S phase and after DNA damage to prevent rereplication.

- 10.Zhong W, Feng H, Santiago FE, Kipreos ET. CUL-4 ubiquitin ligase maintains genome stability by restraining DNA-replication licensing. Nature. 2003;423:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature01747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •11.Arias EE, Walter JC. PCNA functions as a molecular platform to trigger Cdt1 destruction and prevent re-replication. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:84–90. doi: 10.1038/ncb1346. This paper, along with references 20 and 22, shows that Cdt1 interacts with PCNA to facilitate its destruction by the Cul4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase complex.The authors show that mutation of the PCNA interacting motif within Cdt1 or depletion of PCNA stabilizes Cdt1 and causes rereplication.

- 12.Machida YJ, Dutta A. The APC/C inhibitor, Emi1, is essential for prevention of rereplication. Genes Dev. 2007;21:184–194. doi: 10.1101/gad.1495007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Fiore B, Pines J. Emi1 is needed to couple DNA replication with mitosis but does not regulate activation of the mitotic APC/C. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:425–437. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blow JJ, Hodgson B. Replication licensing--defining the proliferative state? Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:72–78. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanny RE, MacAlpine DM, Blitzblau HG, Bell SP. Genome-wide analysis of rereplication reveals inhibitory controls that target multiple stages of replication initiation. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2415–2423. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodward AM, Gohler T, Luciani MG, Oehlmann M, Ge X, Gartner A, Jackson DA, Blow JJ. Excess Mcm2-7 license dormant origins of replication that can be used under conditions of replicative stress. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:673–683. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••17.Davidson IF, Li A, Blow JJ. Deregulated replication licensing causes DNA fragmentation consistent with head-to-tail fork collision. Mol Cell. 2006;24:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.010. This paper shows that uncontrolled replication and not a co-ordinated single round of genome rereplication in G2 activates DNA damage checkpoints. Rereplication results in head-to-tail collision of replication forks and generates short rereplicated sequences of double stranded DNA.

- 18.Krude T, Knippers R. Minichromosome replication in vitro: inhibition of rereplication by replicatively assembled nucleosomes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21021–21029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saxena S, Dutta A. Geminin-Cdt1 balance is critical for genetic stability. Mutat Res. 2005;569:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senga T, Sivaprasad U, Zhu W, Park JH, Arias EE, Walter JC, Dutta A. PCNA is a cofactor for Cdt1 degradation by CUL4/DDB1-mediated N-terminal ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6246–6252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512705200. This paper, along with references 11 and 22, shows that Cdt1 interacts with PCNA to facilitate its destruction by the Cul4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase complex.The authors show that this complex degrades Cdt1 by N-terminal ubiquitination in S phase or after DNA damage.

- 21.Higa LA, Banks D, Wu M, Kobayashi R, Sun H, Zhang H. L2DTL/CDT2 interacts with the CUL4/DDB1 complex and PCNA and regulates CDT1 proteolysis in response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1675–1680. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.15.3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishitani H, Sugimoto N, Roukos V, Nakanishi Y, Saijo M, Obuse C, Tsurimoto T, Nakayama KI, Nakayama K, Fujita M, et al. Two E3 ubiquitin ligases, SCF-Skp2 and DDB1-Cul4, target human Cdt1 for proteolysis. EMBO J. 2006;25:1126–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601002. This paper, along with references 11 and 20, shows that Cdt1 interacts with PCNA to facilitate its destruction by the Cul4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase complex.This paper also highlights that Cdt1 can be degraded in a PCNA-independent manner in S and G2 phases of the cell cycle by SCFSkp2.

- •23.Sansam CL, Shepard JL, Lai K, Ianari A, Danielian PS, Amsterdam A, Hopkins N, Lees JA. DTL/CDT2 is essential for both CDT1 regulation and the early G2/M checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3117–3129. doi: 10.1101/gad.1482106. This paper, along with references 9 and 25, shows that the Cul4-DDB1 E3 complex utilizes the adapter Cdt2 to degrade Cdt1.The authors identify Cdt2 in a screen for DNA damage checkpoint genes in zebrafish and show it is required to prevent rereplication.

- 24.Hu J, Xiong Y. An evolutionarily conserved function of proliferating cell nuclear antigen for Cdt1 degradation by the Cul4-Ddb1 ubiquitin ligase in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3753–3756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •25.Ralph E, Boye E, Kearsey SE. DNA damage induces Cdt1 proteolysis in fission yeast through a pathway dependent on Cdt2 and Ddb1. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:1134–1139. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400827. This paper, along with references 9 and 23, shows that the Cul4-DDB1 E3 complex utilizes the adapter Cdt2 to degrade Cdt1.The authors show that in fission yeast this degradation is cell cycle dependent and induced after DNA damage in an ATR and chk2-independent manner.

- 26.Jeggo PA, Lobrich M. Contribution of DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoint arrest to the maintenance of genomic stability. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakanishi M, Shimada M, Niida H. Genetic instability in cancer cells by impaired cell cycle checkpoints. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:984–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arentson E, Faloon P, Seo J, Moon E, Studts JM, Fremont DH, Choi K. Oncogenic potential of the DNA replication licensing protein CDT1. Oncogene. 2002;21:1150–1158. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••29.Gonzalez S, Klatt P, Delgado S, Conde E, Lopez-Rios F, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Mendez J, Antequera F, Serrano M. Oncogenic activity of Cdc6 through repression of the INK4/ARF locus. Nature. 2006;440:702–706. doi: 10.1038/nature04585. Cdc6 is overexpressed in tumors and the authors present evidence that cdc6, as well as other replication initiator proteins, is recruited to a regulatory domain upstream of the ARF/ink4 locus. Cdc6 can cause transformation by facilitating heterochromatinization and gene silencing which results in a decrease expression of the tumor suppressors ARF, p16INK4a and p15INK4b.

- 30.Tatsumi Y, Sugimoto N, Yugawa T, Narisawa-Saito M, Kiyono T, Fujita M. Deregulation of Cdt1 induces chromosomal damage without rereplication and leads to chromosomal instability. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3128–3140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karakaidos P, Taraviras S, Vassiliou LV, Zacharatos P, Kastrinakis NG, Kougiou D, Kouloukoussa M, Nishitani H, Papavassiliou AG, Lygerou Z, et al. Overexpression of the replication licensing regulators hCdt1 and hCdc6 characterizes a subset of non-small-cell lung carcinomas: synergistic effect with mutant p53 on tumor growth and chromosomal instability--evidence of E2F-1 transcriptional control over hCdt1. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1351–1365. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo J, Chung YS, Sharma GG, Moon E, Burack WR, Pandita TK, Choi K. Cdt1 transgenic mice develop lymphoblastic lymphoma in the absence of p53. Oncogene. 2005;24:8176–8186. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovejoy CA, Lock K, Yenamandra A, Cortez D. DDB1 maintains genome integrity through regulation of Cdt1. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7977–7990. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00819-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinyol M, Salaverria I, Bea S, Fernandez V, Colomo L, Campo E, Jares P. Unbalanced expression of licensing DNA replication factors occurs in a subset of mantle cell lymphomas with genomic instability. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2768–2774. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersen BO, Wagener C, Marinoni F, Kramer ER, Melixetian M, Lazzerini Denchi E, Gieffers C, Matteucci C, Peters JM, Helin K. Cell cycle-and cell growth-regulated proteolysis of mammalian CDC6 is dependent on APC-CDH1. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2330–2343. doi: 10.1101/gad.832500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •36.Mailand N, Diffley JF. CDKs promote DNA replication origin licensing in human cells by protecting Cdc6 from APC/C-dependent proteolysis. Cell. 2005;122:915–926. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.013. This paper delineates the first role for cyclinE/cdk2 in promoting replication licensing by phosphorylating cdc6 and thereby preventing its association and degradation by the APC.

- 37.Duursma A, Agami R. p53-Dependent regulation of Cdc6 protein stability controls cellular proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6937–6947. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.6937-6947.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall JR, Kow E, Nevis KR, Lu CK, Luce KS, Zhong Q, Cook JG. Cdc6 Stability Is Regulated by the Huwe1 Ubiquitin Ligase after DNA Damage. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3340–3350. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yim H, Hwang IS, Choi JS, Chun KH, Jin YH, Ham YM, Lee KY, Lee SK. Cleavage of Cdc6 by caspase-3 promotes ATM/ATR kinase-mediated apoptosis of HeLa cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:77–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li JL, Cai YC, Liu XH, Xian LJ. Norcantharidin inhibits DNA replication and induces apoptosis with the cleavage of initiation protein Cdc6 in HL-60 cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:307–314. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •41.Bartkova J, Rezaei N, Liontos M, Karakaidos P, Kletsas D, Issaeva N, Vassiliou LV, Kolettas E, Niforou K, Zoumpourlis VC, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature. 2006;444:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature05268. This paper along with reference 42 shows a relationship between replication stress which activates the DNA damage response and oncogene-induced senescence.These authors show that oncogene-induced senescence requires intact DNA damage checkpoints and induces replication stress characterized by terminated replication forks and DNA double strand breaks. Moreover, suppression ATM-dependent signaling abrogates senescence and increases tumorigenesis and invasiveness in mouse models.

- •42.Di Micco R, Fumagalli M, Cicalese A, Piccinin S, Gasparini P, Luise C, Schurra C, Garre M, Nuciforo PG, Bensimon A, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature. 2006;444:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nature05327. This paper along with reference 41 shows a relationship between replication stress which activates the DNA damage response and oncogene-induced senescence.The authors show that oncogenes induce hyper-replication, asymmetric replication fork movement, and loss-of-heterozygosity. Rereplication is crucial for both the stimulation of DNA damage response pathways and senescence inititated by activated oncogenes.

- 43.Albertson DG. Gene amplification in cancer. Trends Genet. 2006;22:447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wyman C, Kanaar R. DNA double-strand break repair: all’s well that ends well. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:363–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smolen GA, Muir B, Mohapatra G, Barmettler A, Kim WJ, Rivera MN, Haserlat SM, Okimoto RA, Kwak E, Dahiya S, et al. Frequent met oncogene amplification in a Brca1/Trp53 mouse model of mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3452–3455. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hagen AI, Bofin AM, Ytterhus B, Maehle LO, Kjellevold KH, Myhre HO, Moller P, Lonning PE. Amplification of TOP2A and HER-2 genes in breast cancers occurring in patients harbouring BRCA1 germline mutations. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:199–203. doi: 10.1080/02841860600949552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo L, Uerlings Y, Happel N, Asli NS, Knoetgen H, Kessel M. Regulation of geminin functions by cell cycle-dependent nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4737–4744. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00123-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cortez D, Glick G, Elledge SJ. Minichromosome maintenance proteins are direct targets of the ATM and ATR checkpoint kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10078–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403410101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zybina TG, Zybina EV. Cell reproduction and genome multiplication in the proliferative and invasive trophoblast cell populations of mammalian placenta. Cell Biol Int. 2005;29:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deutsch VR, Tomer A. Megakaryocyte development and platelet production. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:453–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •51.Gonzalez MA, Tachibana KE, Adams DJ, van der Weyden L, Hemberger M, Coleman N, Bradley A, Laskey RA. Geminin is essential to prevent endoreduplication and to form pluripotent cells during mammalian development. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1880–1884. doi: 10.1101/gad.379706. Geminin knock-out mice arrest at the 8 cell stage of development when they have prematurely differentiated into giant trophoblastic cells and undergone endoreduplication. In the normal regulation of endoreduplication in trophoblastic cells, geminin is degraded to facilitate duplication of the genome.

- 52.Bermejo R, Vilaboa N, Cales C. Regulation of CDC6, geminin, and CDT1 in human cells that undergo polyploidization. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3989–4000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vilaboa N, Bermejo R, Martinez P, Bornstein R, Cales C. A novel E2 box-GATA element modulates Cdc6 transcription during human cells polyploidization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:6454–6467. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kitamura E, Blow JJ, Tanaka TU. Live-cell imaging reveals replication of individual replicons in eukaryotic replication factories. Cell. 2006;125:1297–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Angers S, Li T, Yi X, MacCoss MJ, Moon RT, Zheng N. Molecular architecture and assembly of the DDB1-CUL4A ubiquitin ligase machinery. Nature. 2006;443:590–593. doi: 10.1038/nature05175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li T, Chen X, Garbutt KC, Zhou P, Zheng N. Structure of DDB1 in complex with a paramyxovirus V protein: viral hijack of a propeller cluster in ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2006;124:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Higa LA, Wu M, Ye T, Kobayashi R, Sun H, Zhang H. CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase interacts with multiple WD40-repeat proteins and regulates histone methylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1277–1283. doi: 10.1038/ncb1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]