Abstract

New generation anthrax vaccines have been actively explored with the aim of enhancing efficacies and decreasing undesirable side effects that could be caused by licensed vaccines. Targeting novel antigens and/or eliminating the requirements for multiple needle injections and adjuvants are major objectives in the development of new anthrax vaccines. Using proteomics approaches, we identified a spore coat-associated protein (SCAP) in Bacillus anthracis. An E. coli vector-based vaccine system was used to determine the immunogenicity of SCAP. Mice generated detectable SCAP antibodies three weeks after intranasal immunization with an intact particle of ultraviolet (UV)-irradiated E. coli vector overproducing SCAP. The production of SCAP antibodies was detected via western blotting and SCAP-spotted antigen-arrays. The adjuvant effect of a UV-irradiated E. coli vector eliminates the necessity of boosting and the use of other immunomodulators which will foster the screening and manufacturing of new generation anthrax vaccines. More importantly, the immunogenic SCAP may potentially be a new candidate for the development of anthrax vaccines.

Keywords: immunogenic, spore coat, Bacillus anthracis, proteomics, vector, vaccine

Recent terrorist attacks have involved the use of Bacillus anthracis spores as weapons. The development of vaccines for anthrax prevention has been extensively explored. The US anthrax vaccine which was licensed in 1970 is made from the filtrate of a non-encapsulated attenuated strain [1]. However, this regimen has unknown efficacy and can trigger local pain and edema as well as other undesirable side effects [2]. Contemporary anti-anthrax remedies focus mainly on three-component toxins: protective antigen (PA), lethal factor (LF), and edema factor (EF) which are massively produced by vegetative cells during the late stages of Bacillus anthracis infection [3, 4]. Although targeting PA has been shown to have varying degrees of success against Bacillus anthracis [5], the degree of protection provided by PA targeting methods against inhalational anthrax remains unknown. The recombinant PA products are currently undergoing human clinical trials, but they would still require multiple, needle-based dosing, and the inclusion of the adjuvant aluminum [6]. Thus next generation anthrax vaccines targeting new antigens may be needed to enhance efficacies and eliminate side effects.

Using proteomics approaches, we identified a spore coat-associated protein (SCAP) in the dormant spores of Bacillus anthracis Sterne strain. To know if the SCAP is an immunogenic protein, we utilized a vector-based vaccine system to immunize mice. SCAP was expressed in an E. coli vector. After irradiation with UV, an intact particle of irradiated E. coli vector overproducing SCAP was intranasally administered to the mice for immunization. Without adding extra adjuvants and boosting, immunized mice produced detectable antibodies against SCAP after a three-week administration, suggesting that SCAP is an immunogenic protein and the irradiated E. coli vector exhibits an adjuvant effect. Thus, SCAP can potentially be a new candidate for development of next generation anthrax vaccines. In addition, the irradiated E. coli vector overproducing an exogenous immunogen may facilitate the screening of new anthrax vaccine candidates and scale-up the production of next generation vaccines that can be manufactured rapidly and administered non-invasively in a wide variety of disease settings.

Materials and methods

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE)

Dormant spores of Bacillus anthracis Sterne strain were lyzed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, followed by adding dithiothreitol (DTT) to 0.1% and tricholoroacetic acid (TCA) to 10%]. TCA-precipitated proteins were separated by 2-DE via an IPGphor (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) according to protocols in our laboratory [7]. The 11 cm linear gradient Immobiline Dry-Strips (pH4-7) were used. Proteins in Dry-Strips were subsequently separated by 12.5% polyacrylamide gels in a Hoefer SE600 system (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ). Gels were visualized via silver nitrate staining [8]. In-gel digestion with trypsin and protein identification via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (Q-TOF MS/MS) analysis were performed essentially as described previously [9, 10].

MALDI-TOF MS

Peptides in the tryptic digests were eluted from ZipTips with 75% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and air-dried. Peptide fragments were then mixed with a matrix solution containing α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid dissolved in 50% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and analyzed with a PerSeptive Voyager-DE MALDI-TOF MS (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA) [9]. Peptides were laser-evaporated at 337 nm, and each spectrum was the cumulative average of 50-100 laser pulses. All peptides were measured as mono-isotopic masses, and a trypsin autolytic peak at 2164.04 m/z was chosen for internal calibration. Up to one missed trypsin cleavage was allowed, although most matches did not contain any missed cleavages. This procedure resulted in mass accuracies of 100 ppm. Peptide mass spectra above 5% of full scale were analyzed, interpreted, and matched to SWISS-PROT database using Mascot, a searching algorithm available at the Matrix Science Homepage, http:/www.matrixscience.com. Matches were computed using a probability-based Mowse score defined as -10 × log p, where p is the probability that the observed match was a random event [9]. Mowse scores greater than 70 were considered significant (p ≤ 0.05).

Q-TOF MS/MS sequencing and database searching

ZipTips-eluted samples were introduced into a nano reverse-phase column (75 μm × 15 cm, with Jupitor 4 μm Proteo bead packed in our laboratory), and gradient eluted into a Q-TOF 2 quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA) through an electrospray interface for tandem mass spectral analyses. Liquid chromatography was conducted using a LC Packings Ultimate LC, Switchos microcolumn switching unit, and Famos autosampler (LC Packings, San Francisco, CA). Spectral analyses were performed in automatic switching mode whereby multiply-charged ions were subjected to MS/MS if their intensities rose above 6 counts. The MassLynx 3.5 software (Waters, Milford, MA) [10] was utilized for instrument operation, data acquisition, and analysis. The search for amino acid sequence similarity was performed using BLAST and/or Scanps available from ExPASy internet server at http://www.expasy.ch.

Plasmid construction and recombinant SCAP expression and purification

SCAP was amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by using Platinum Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with primers 5’-AGTCTGAAAAAGAAATTAGGTATGG and 5’-GGAGCTCGAGTTATTTTTCTTCTCCAGCTTCTTGG. The PCR product was digested with XhoI and inserted into pIVEX-MBP vector (Roche, Nutley, NJ) through StuI and XhoI in the multiple cloning sites. This insertion creates an in frame fusion of 6xHis and maltose binding protein (MBP) tags followed by factor Xa protease cleavage sequence at the N terminus of the cloned SCAP. The insert was verified by DNA sequence analysis (data not shown). In order to achieve high levels of protein expression and tight regulation in E. coli, the 6xHis-MBP-SCAP DNA fragment was cleaved and ligated into pET15b vector (EMD Biosciences, Inc., San Diego CA) through XbaI and XhoI sites and transformed into BL21(DE3) (EMD Biosciences, Inc., San Diego, CA). Thus, the E. coli vector-based vaccine (E. coli BL21 (DE3) T7/lacO SCAP) was constructed in the pET15b vector which contains a T7/LacO promoter to control protein expression. Protein expression was induced by 1 mM of isopropyl b-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when the bacteria culture was in logarithmic growth phase (OD595 at 0.4-0.5). After 3 h IPTG induction at 37 °C, the cells were sonicated and lysed with 50 mg/ml lysozyme and 0.5% Triton-X 100 in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 30 min. The fusion protein (approximately 1 mg) was purified from 1012 bacteria by the standard nickel resin purification protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) [11]. Subsequently, the purified fusion protein was sealed with a dialysis membrane (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and dialyzed in 0.5% Triton-X 100 in PBS at 4 °C overnight. To remove 6xHis and MBP tags, purified fusion protein (300 μg) was cleaved by factor Xa protease (6 μg) (NEB, Ipswich, MA) at room temperature overnight. Approximately 100 μg of purified proteins without 6xHis and MBP tags was obtained. 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequent gel staining with Coomassie blue were used for detection of SCAP expression.

Proteolytic activity of SCAP

Proteolytic activity was measured using azocasein (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo) as substrate [12]. Sample (0.5 ml) was added into 1 ml of azocasein [0.2% (w/v) in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5] for reaction. After incubation (1 h, 37 °C), the reaction was stopped by adding 2 ml of cold 10% TCA. Precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation (10,000 g, 10 min). Dilute sodium hydroxide (0.5 M) was added to an equal volume of supernatant. The mixture was allowed to stand for 20 min, and the absorbance (440 nm) was measured. One unit was defined as the amount of enzyme yielding an increase in absorbance of 1.0 per hour at 440 nm. Specific activity was expressed as units/mg protein.

Immunization with a UV-irradiated E. coli vector-based vaccine

E. coli harboring expression vectors with or without inserted SCAP genes were grown to logarithmic phase and induced with IPTG as described above. E. coli was spread on a sterilized surface and irradiated with UV at total energy of 3500 J/m2 by a Spectrolinker (Spectronics, Westbury, NY) [13]. The viability of UV-irradiated E. coli was determined by observing the bacterium colonies on Lauria-Bertani (LB) agar plates. For immunization, female ICR mice approximately 3-month-old (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), were intranasally immunized by inoculating 25 μl of UV-irradiated E. coli vector-based vaccine (E. coli BL21 (DE3) T7/lacO SCAP) into the nasal cavity of each mouse. 109 colony forming units (CFU) of E. coli were irradiated by UV prior to inoculation. CUF was determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of bacteria on LB agar plates and enumerating the bacterial colonies after overnight incubation at 37°C [14]. Serum was harvested for western blot and antigen array analysis at three weeks post immunization. Mice immunized by applying empty expression vectors served as control groups. Each group and each experiment was performed in triplicate. All experiments using mice were conducted according to institutional guidelines. 12.5% polyacrylamide gels and ECL kits (Pierce, Rockford, IL) were used for western blot analysis.

Antigen array printing and hybridization

Recombinant SCAP and MBP-tagged SCAP were diluted in 3X saline sodium citrate (SSC) and spotted on poly-L-lysine slides along with recombinant tetanus toxin C fragment (data not shown) and mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) for negative and positive controls, respectively. Proteins in three concentrations (30 mg/ml, 30 μg/ml and 30 ng/ml) were printed on the slides twice. The printing procedure has been described and essentially followed the manual of the DeRisi arrayer with silicon microcontact printing pins (Parallel Synthesis Technologies, Inc. Santa Clara, CA) [15, 16]. Arrays were UV cross linked with a total energy of 700 J/m2, then blocked with 0.2% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, and hybridized with diluted mouse serum at 4 °C overnight. After secondary antibody (Cy-3 labeled goat-anti-mouse IgG) incubation for 1 h at room temperature, arrays were washed 3 times in PBS and finally rinsed with water and dried before scanning. Arrays were scanned by GenePix 4000B scanner and analyzed by GenePix Pro 6.0 software (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA), Cluster and TreeViw programs [17].

Assay for apoptotic cells

A/J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were intra-tracheally injected with 25 μl of PBS or eluted fractions of proteins purified from vectors with and without SCAP insertion for 24 h. 6.25 ng of purified SCAP in 25 μl was injected per mouse. One day after injection, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was collected by instilling 5 ml of PBS into the lung via a tracheal cannula and carefully withdrawing the fluid. Cells in bronchoalveolar larvage fluid were centrifuged down to slides using a Cytospin 2 (Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA). Cells in the slides were subsequently fixed with 10% formalin and stained with a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega, Madison MI). Apoptotic cells were visualized in light blue which derived from the merging of green fluorescein-12-dUTP with nuclei blue dye Hoechst 33258.

Results

Identification of SCAP via proteomics

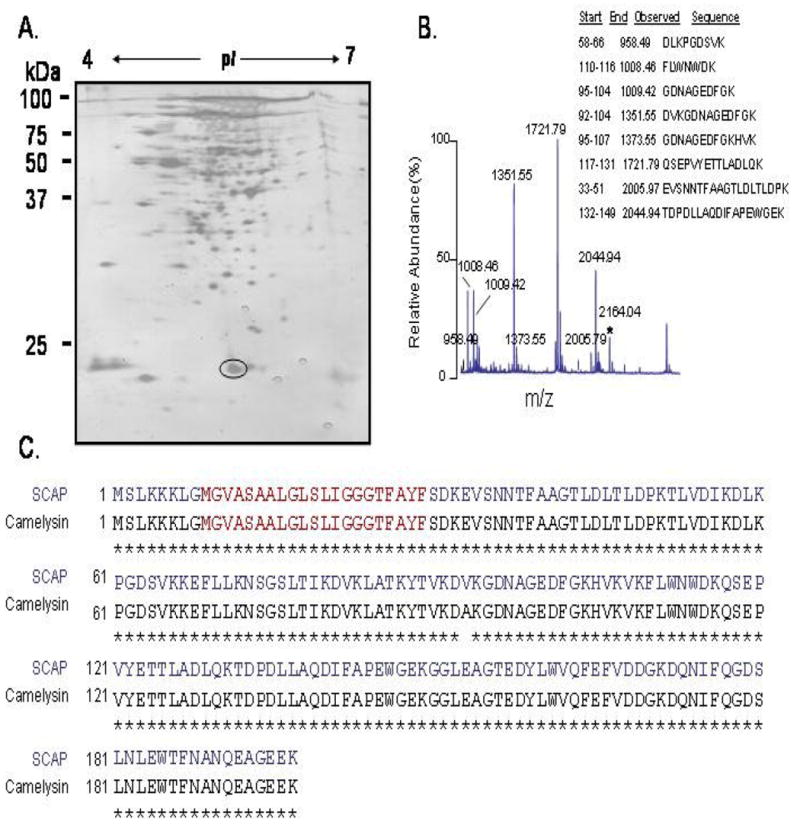

A proteome of Bacillus anthracis with fifty proteins has been established in our laboratory [2, 7]. Proteins from dormant Sterne spores were precipitated by TCA as described [7]. TCA-precipitated proteins were separated by 2-DE and stained with silver nitrate. Over five-hundred protein spots were reproducibly displayed across an iso-electric focusing range of 4 to 7 (Fig. 1A). A protein spot with Mr/pI at 21.7kDa/4.6 (Fig. 1A, circled) was originally assigned as a hypothetical protein (NP_655179) [7]. Here, we extracted the peptide fragments of this protein spot by in-gel trypsin digestion, generated the MALDI-TOF MS spectrum, and searched the updated Swiss-Prot database. Eight peaks within the MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of this protein spot matched those of spore coat-associated protein (SCAP) (accession number: Q81TI3) of Bacillus anthracis Ames strain (Fig. 1B). SCAP shares high amino acid homology (99.5 %) with a cell envelope-bound metalloprotease camelysin in Bacillus cereus (Fig. 1C) [3, 4]. Camelysin was known to be strongly bound to the cell surface of Bacillus cereus. A predicted transmembrane domain (MGVASAALGLSLIGGGTFAYF) can also be found in both SCAP and camelysin.

Fig. 1.

Proteomic identification of a spore coat-associated protein and its similarity with camelysin.

Protein (300 μg) from dormant spores of the Bacillus anthracis Sterne strain was separated in a silver-stained 2-DE gel as described in Materials and Methods (A). A circled spot was subsequently excised and analyzed by in-gel trypsin digestion followed by MALDI-TOF MS. The MALDI-TOF MS spectrum (B) of a circled spot revealed that the tryptic peptide mass fingerprint with eight peptide masses match with that of spore coat-associated protein (SCAP) in Bacillus anthracis (accession number: Q81TI3). The predicted peptide fragments corresponding to observed m/z values observed for SCAP are shown (B). The tryptic autodigestive peak at m/z value 2164.04, indicated by an asterisk, served as an internal calibration standard. The amino acid homology of SCAP (blue) to camelysin (black) (accession number: Q63E88) in Bacillus cereus was illustrated (C). Asterisks indicated the amino acid identities. Amino acid residues (9-29) were predicted as a transmembrane domain (red).

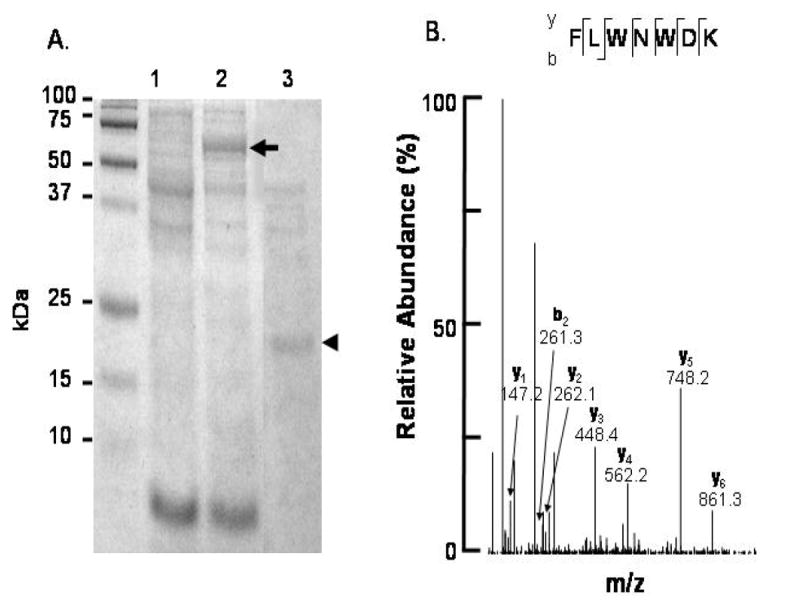

To examine the biological function and immunogenicity of SCAP, we inserted the SCAP coding sequence with MBP and 6xHis tags into a pET15b vector and expressed SCAP fusion protein in E. coli BL21 (DE3). The pET15b vector contains a T7/LacO promoter to control protein expression. After IPTG induction, SCAP expression in the E. coli vector-based vaccine (E. coli- T7/LacO SCAP) was easily detected by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2A, Lane 2). SCAP was efficiently purified by a Ni-NTA (nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid) resin because the vector allows for the fusion of a 6xHis-tagged affinity peptide to the terminus of SCAP. Factor Xa protease was used to cut out the fusion proteins from the recombinant SCAP. Purified SCAP was visualized by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2A, Lane 3). The SCAP expression and purification was confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS (data not shown) and Q-TOF MS/MS analysis (Fig. 2B). One internal sequence with seven amino acid residues (FLWNWDK) from SCAP was detectable in a Q-TOF MS/MS spectrum, indicating the protein band shown in figure 1A at approximately 21 kDa is purified SCAP. Since SCAP shares high homology with a metalloprotease camelysin in Bacillus cereus, we thus determine the proteolytic activity of purified SCAP using azocasein as substrate. The specific activity of the purified SCAP was 1.25 ± 0.07 units/mg of protein as compared to the activity in proteins purified from an empty expression vector (without SCAP insertion), which was 0.56 ± 0.06 units/mg of protein, indicating that purified SCAP possesses a proteolytic activity.

Fig. 2.

Confirmation of expression and purification of SCAP.

The construct encoding SCAP for protein expression was described in Materials and methods. SCAP was expressed in the E. coli in the absence (A, lane 1) or presence (A, lane 2) of 1 mM IPTG. After IPTG induction, SCAP was successfully expressed in E. coli and shown by 12.5% SDS-PAGE (arrow). Purified SCAP at about 21 kDa (A, lane 3, arrowhead) was obtained by using Ni-NTA agarose. Purified SCAP was obtained by removing the SCAP-tag with factor Xa protease. The expression and purity of SCAP were confirmed by analysis of spectra of MALDI-TOF MS (data not shown) and Q-TOF MS/MS sequencing (B). The MALDI-TOF MS spectrum of purified SCAP is similar with that in figure 1B. An internal peptide of SCAP with m/z value at 1008.46 analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS was sequenced by Q-TOF MS/MS as FLWNWDK (B).

The toxic effect of SCAP

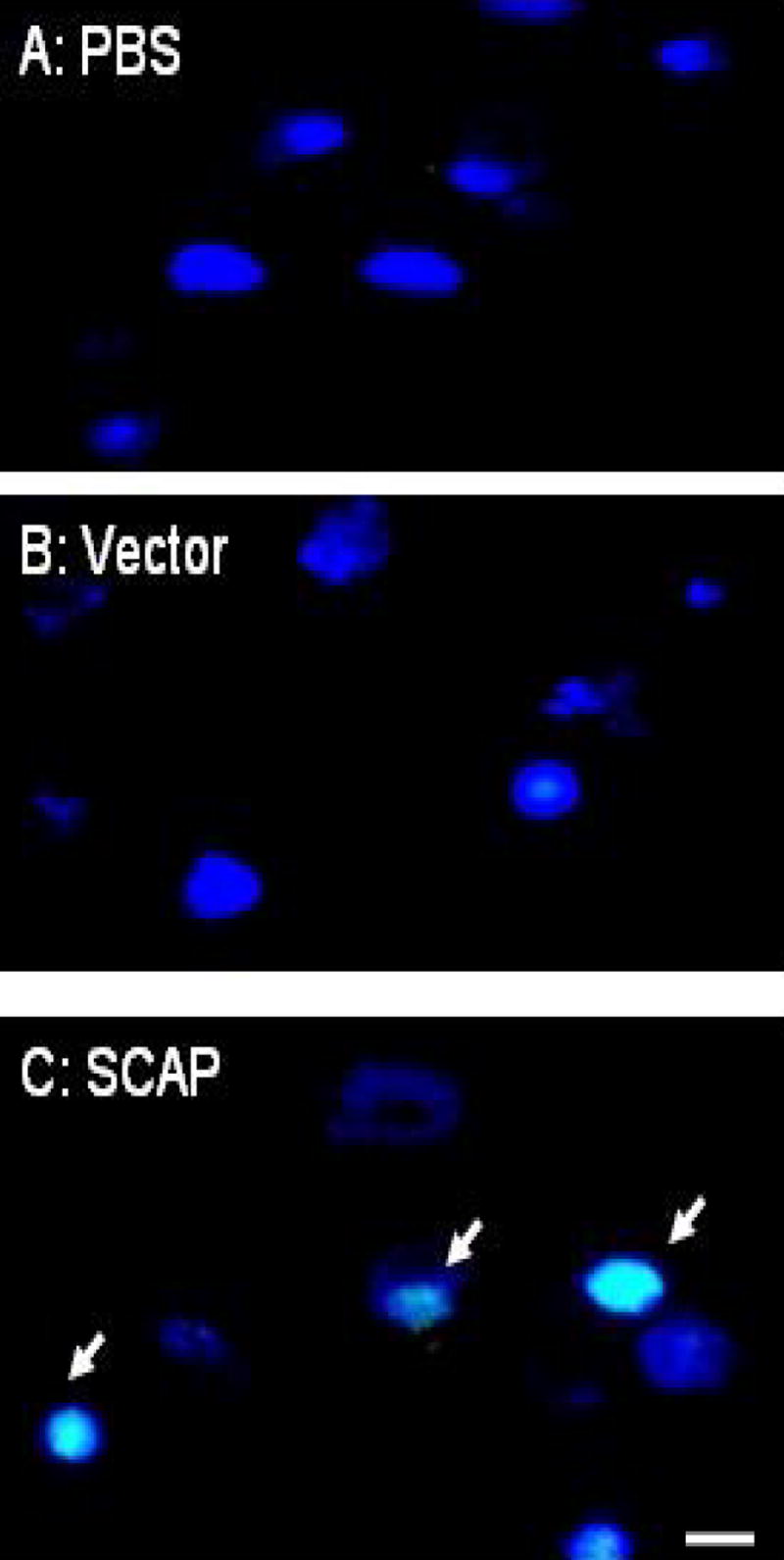

The cells in the lung have been known to be the primary target of inhalational Bacillus anthracis spores [18]. Thus we tested whether SCAP exerts a detrimental effect on cells in the bronchoalveolar larvage fluid of A/J mice. A/J mice have been known to be a spore-susceptible mouse strain [18 -20]. Purified SCAP (6.25 ng) was injected into the lung of A/J mice via intra-tracheal instillation. After one-day incubation, apoptotic cells were examined by TUNEL assay. No apoptotic cells were detected from mice injected with PBS (Fig. 3A) or proteins purified from an empty expression vector (without SCAP insertion) (Fig. 3B). Apoptotic cells are only detectable in the SCAP-injected mice (Fig. 3C), suggesting that SCAP is a toxic protein.

Fig. 3.

SCAP triggers cells in bronchoalveolar larvage fluid to undergo apoptosis. Purified SCAP (6.26 ng) was injected into the lung of A/J mice via intra-tracheal instillation. One day after injection, cells from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were isolated and examined by TUNEL assay. Cells isolated from A/J mice treated with PBS (A) or proteins purified from E. coli transformed with an empty expression vector (B, vector) showed no apoptotic cells. In contrast, apoptotic cells (arrows) are detectable in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid isolated from mice injected with purified SCAP for one day (C). Light blue indicates the merging of green fluorescein-12-dUTP with nuclei dye Hoechst 33258, representing the localization of apoptotic cells. Bar, 5 μm.

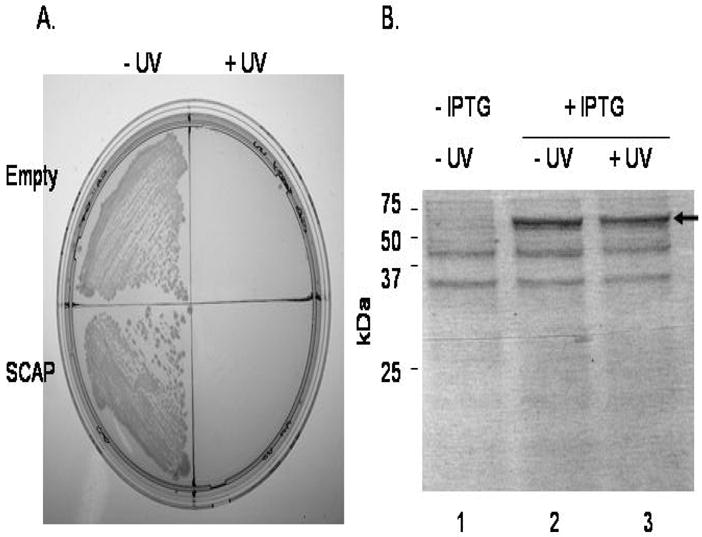

Creation of vector-based vaccine system

It was recently shown that vaccines based on “killed but metabolically active” (KBMA) microbes generated via UV rather than heat treatment protected mice from pathogen challenges [21]. Therefore, we used a UV-irradiated E. coli vector-based vaccine as one of our strategies to induce an immune response in vivo. To ensure the UV-irradiated E. coli would not replicate, we escalated the doses of total energy from 200 to 4500 J/m2 and found 3500 J/m2 to be optimal (Fig. 4A). Although the effect of UV irradiation is primarily on nucleic acids, the level of SCAP protein expressed from the E. coli vector before and after UV irradiation was compared. The amounts of SCAP in the Coomassie blue stained SDS-PAGE gels was not altered (Fig. 4B) suggesting that the UV-irradiated E. coli vector was replication incompetent but preserved the over-expression of recombinant protein.

Fig. 4.

UV-irradiation of an E. coli vector-based vaccine over-expressed SCAP. Bacteria were plated on a LB-agar plate as indicated (A). The upper half of the plate is control bacteria that were transformed with empty expression vectors. The lower half is the colonies of SCAP over-expressed E. coli. The left and right halves of the plate are bacteria without (- UV) and with UV irradiation (+ UV), respectively. The result indicates either control or SCAP-over-expressed bacteria are efficiently inactivated by 3500 J/m2 of UV irradiation. Protein profile in bacteria transformed by a SCAP fusion protein expression plasmid before (lane 1; - IPTG) and after (lane 2 and 3: + IPTG) IPTG induction is shown on a Coomassie blue gel (B). There was no significant change of protein expression profile including SCAP (arrow) before (lane 2) and after (lane 3) UV-irradiation.

SCAP is an immunogenic protein

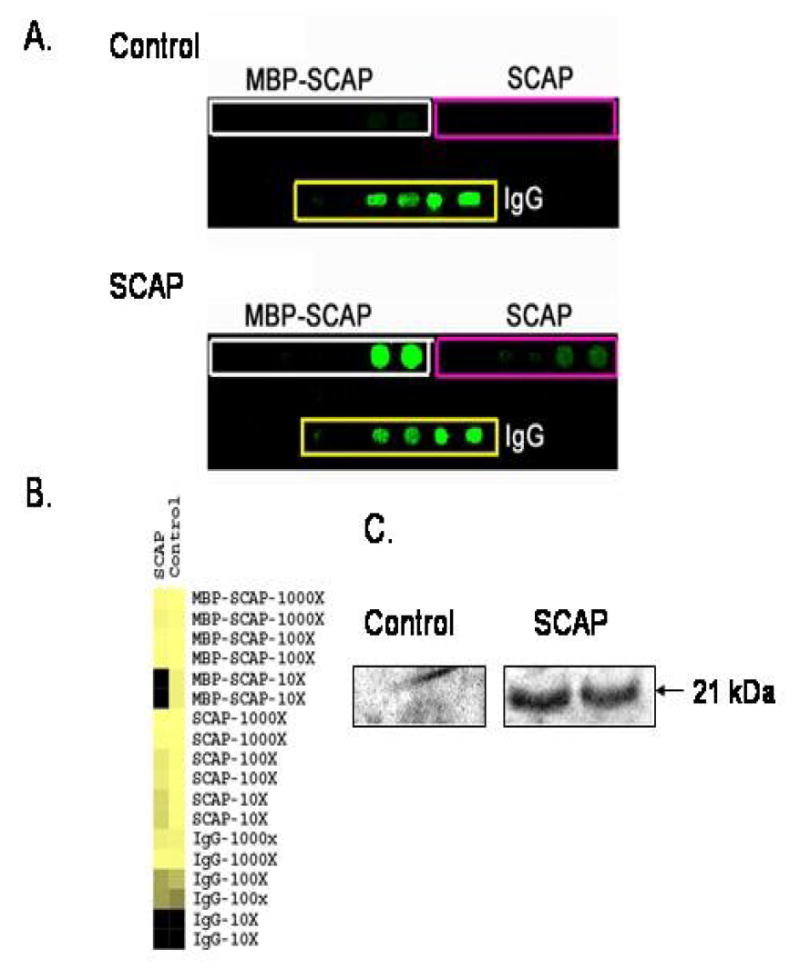

For determination of imunogenicity of SACP, E. coli. that carries either an empty expression vector or a SCAP expression plasmid were killed by UV irradiation after IPTG induction. For immunization, the UV-irradiated E. coli vector-based vaccine, not mixed with exogenous adjuvants, was then directly administered into the nasal cavity of mice. We pooled the sera harvested from each group (n = 4) of mice three weeks after immunization. The production of anti-SCAP IgG was detected by an antigen array (Fig. 5A) and western blot (Fig. 5C). The antigen array was created by spotting with recombinant SCAP, MBP-tagged SCAP, mouse IgG (positive controls) and tetanus toxin C fragment (negative controls; data not shown). The sera from mice immunized with an empty expression vector and an E. coli vector with SCAP over-expression were hybridized on arrays (Fig. 5A). While the negative control yielded only background signals, the positive control (IgG) generated a dilution-dependent signal reduction. The experiment clearly showed that anti-SCAP antibody was produced after immunization with E. coli vector-based vaccine (E. coli BL21 (DE3) T7/lacO SCAP) by comparing to control serum. More importantly, we found the anti-SCAP antibody can be produced without boosting. The digitized array images were converted into a heat-map format (Fig. 5B) for ease of analysis. The MBP-tagged SCAP spots (MBP-SCAP) have significantly higher intensity than SCAP spots. This may simply reflect more epitopes were recognized by a bigger MBP-SCAP (57 kDa) fusion protein than SCAP alone (21 kDa). Furthermore, the production of anti-SCAP antibody was confirmed by western blotting to recombinant SCAP (Fig. 5C). Data from the detection of antigen arrays and western blotting indicated that SCAP is immunogenic.

Fig. 5.

Anti-SCAP antibody assays.

Antigens indicated were spotted twice for each dilution of 10-fold serial dilution (A). The upper and lower arrays were hybridized with sera (1:250 dilution) from mice immunized with an empty expression vector (Control) or a SCAP over-expressing E. coli vector (SCAP). Arrays were spotted with MBP-tagged SCAP (MBP-SACP; enclosed by white rectangles), SCAP (enclosed by pink rectangles) and mouse IgG (enclosed by yellow rectangles). Mouse IgG is used as a positive reaction as well as a reference for array normalization. The digital images in panel A were quantified and analyzed with GenePix 6.0, Cluster and TreeViw programs (B). The spot intensities were normalized to the average of two spots of IgG with 100 × dilution on each array. The product value of each spot was expressed in a gray-scale fashion. The result unambiguously revealed anti-SCAP antibody production from the SCAP immunized mice. Factor Xa protease cleaved SCAP was subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and blotted with immunized mouse sera (C). A band at 21 kDa, consistent with full-length SCAP protein was recognized by sera (1:500 dilution) from SCAP (right) immunized but not control (left) mice. Two identical samples were run on the gel for each blot.

Discussion

The entire amino acid sequence of SCAP of Bacillus anthracis shares 99.5% identity with camelysin (casein-cleaving metalloproteinase) of Bacillus cereus [22, 23]. Both of these proteins contain a predicted transmembrane domain, suggesting that SCAP may have a similar function as camelysin which is strongly bound to the cell surface and exerts a proteolytic activity. Camelysin preferentially cleaves peptide bonds in front of aliphatic hydrophobic amino acids and hydrophilic amino acid residues, avoiding bulky aromatic residues in the P1’ position [23]. Camelysin has been known to be a neutral metalloprotease, showing its typical strong inhibition by metal chelators, but it is insensitive to phosphoramidon or zincov, which are the strongest inhibitors of thermolysin type neutral metalloprotases [23]. Bacterial surface proteases have been detected in some gram-positive species [24], and often play a key role as virulence factors through interactions with the host defense systems and by destruction of extracellular matrix proteins. It has been reported that camelysin from Bacillus cereus could have a similar significant role in host-pathogen interactions, because it cleaves serum protease inhibitors, collagen type I, fibrin, and fibrinogen [23]. Although the proteolytic activity of SCAP was measurable when azocasein was used as substrate, it would be worthwhile to determine the real substrates in biological system. Our data indicated that SCAP exhibits a toxic effect on the cells from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (Fig. 3). It is also worth studying if SCAP possesses protease activity that contributes to its toxicity and investigating what types of cells in bronchoalveolar larvage fluid underwent apoptosis after SCAP treatment. The PBS and samples derived from E. coli transformed with an empty expression vector were used as controls to examine the SCAP-induced apoptosis (Fig. 3). To exclude the possibility that the apoptosis was induced by any foreign protein, an anthrax alanine racemase (accession number: Q81TI3) available in our laboratory was injected into the lung of A/J mice via intra-tracheal instillation. After alanine racemase (6.26 ng) injection, no apoptosis of cells in bronchoalveolar larvage fluid was detectable (data not shown). Indeed, injection with a genetically modified and non-toxic SCAP may provide the further confirmation of cytotoxicity of SCAP. In addition, since the vaccine contains a toxic SCAP antigen may be a less acceptable candidate for the human application; therefore, it will be essential to engineer a non-toxic yet highly immunogenic vaccine to achieve a marketable version for public use in the future. Genetic detoxification of protein antigens has been widely used in human vaccines [25].

The SCAP of Bacillus anthracis was originally assigned as a hypothetical protein that was down-regulated in germinating cells in comparison with dormant spores [7]. One possibility is that SCAP is released from dormant spores when the spores break down their dormancy during germination at the early stage of anthrax infection. Due to the high identity of SCAP to the cell surface-bound metalloprotase camelysin and its differential abundance during the early life cycle of Bacillus anthracis, SCAP can potentially serve as a new vaccine target aimed at blocking the early stage of anthrax infection. There are several advantages in support of developing vaccines targeting the early stages of anthrax infection. The interaction between spores and host cells is an early-stage event during the life cycle of Bacillus anthracis. By interrupting the early-stage events, the late-stage events including the production of PA, LF, or EF cannot occur [26]. Additionally, in contrast to toxins and antibiotic resistance that are prone to change, spore-host cell interaction is highly conserved and is difficult to alter [27]. Blocking upstream events with vaccines may prevent the use of anthrax spores as bioweapons. More importantly, PA, LF, and EF are encoded by a plasmid in Bacillus anthracis [26]. Therefore it is possible to replace this plasmid with others that encode other malicious toxins (e.g., tetanus toxin, cobra toxin, etc.). Thus, bioterrorists have the potential to introduce mutant anthrax spores that produce toxins other than PA-LF-EF.

It has been observed that recombinant proteins or vaccines derived from heat-killed microbes often induce weaker cellular immunity than live vaccines [28]. However, it is not ideal to use live pathogens as vaccines due to safety concerns. Alternatively, killed but metabolically active (KBMA) microbes generated via UV or gamma irradiation have been reported to have the benefit of live vaccines to induce an appropriate immune response without the issue of pathogen replication in the host [21, 29]. We chose UV irradiation to create KBMA vaccines since the equipment is readily available in most laboratories. It has been well documented that the major effect of UV to inactivate bacteria is through nucleic acid damage [30]. Indeed, our data showed that UV irradiation did not significantly change the protein expression profile in the E. coli vector (Fig. 4). Furthermore, immunization using a UV-irradiated E. coli vector can elicit a detectable humoral immune response (Fig. 5). In addition, the humoral immune response can be induced without boosting or the assistance of exogenous adjuvants. It is certainly worth investigating if immunization using a UV-irradiated E. coli vector can activate the cellular immune response which is known to be critical for elimination of invading pathogens.

E. coli components such as lipopolysaccharide and CpG have been commonly used as adjuvants for immunization [31, 32]. It has been illustrated that an array of E. coli components are able to induce a specific gene expression profile in dendritic cells via the activation of the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway [33-35]. Conceivably, the high immunogenicity of endogenous E. coli components may thus mediate the efficiency of E. coli vector-based vaccines via activation of an E. coli-induced defense mechanism, thus serving as a natural adjuvant. Overall, the use of E. coli vector-based vaccines eliminates the time-consuming steps for antigen purification and the requirement for deleterious adjuvants. Our data support that intranasal immunization with E. coli vector-based vaccines is a non-invasive method that circumvents the intrinsic problems associated with multiple needle injections (Fig. 5). Thus, E. coli vector-based vaccines will be beneficial for large-scale, rapid, low-cost production, distribution, and administration [34].

We used an antigen array to assay antibody production in addition to the traditional western blot (Fig. 5). Several advantages are obvious and have been documented [36], such as reduced reagent consumption and multiplexing. We can print thousands of arrays with just 10 μl of antigen supply with our current arrayer and spotting pins. An area of one square inch can accommodate thousands of antigen spots and can be hybridized with only 20 μl of diluted serum. Such features are useful not only for screening vaccine candidates but also for studying other aspects of the immune response. By using mouse IgG for normalizing day-to-day experimental variation, we were able to quantify relative antibody titers on the array. The antigen array has been reported to have superior sensitivity as compared to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [36-38].

Conclusions

In summary, we employed proteomics approaches to identify a novel spore coat-associated protein (SCAP) in Bacillus anthracis. The immunogenicity of SCAP was determined by a non-invasive E. coli vector-based vaccine system. Additionally, the production of SCAP antibodies was detected via antigen spotted arrays. Our data support that SCAP serves as a novel antigen candidate to determine the protective effect of the challenge of Bacillus anthracis spores. The non-invasive E. coli vector-based vaccine system holds promise as the preferred modality for vaccination in general and for mass immunizations needed specifically during extenuating disease outbreaks and bioterrorist attacks.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants (R01-AI067395-01, R21-R022754-01, R21-I58002-01), a SERCEB grant 5 U54 AI057157-02, a Dermatology Foundation Grant (C.-M. H.) and P30-AI36214-12S1 (Y.-T. L.). We thank M. Kirk and L. Wilson for their assistance with MALDI-TOF MS and Q-TOF MS/MS analysis, DT McPherson for his assistance with molecular cloning and AJ Livengood for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used

- CFU

colony forming units

- 2-DE

two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EF

edema factor

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- LB

Lauria-Bertani

- LF

lethal factor

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IPTG

isopropyl b-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- KBMA

killed but metabolically active

- MALDI-TOF MS

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- MBP

Maltose binding protein

- PA

protective antigen

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- Q-TOF MS/MS

quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SSC

saline sodium citrate

- TCA

tricholoroacetic acid

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase dUTP nick end labeling

- UV

ultraviolet

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Inglesby TV, O’Toole T, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Friedlander AM, Gerberding J, Hauer J, Hughes J, McDade J, Osterholm MT, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Tonat K. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense, Anthrax as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 1999;281:1735–1745. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang CM, Elmets CA, Tang DC, Li F, Yusuf N. Proteomics reveals that proteins expressed during the early stage of Bacillus anthracis infection are potential targets for the development of vaccines and drugs. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2004;2:143–2151. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(04)02020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaur R, Gupta PK, Banerjea AC, Singh Y. Effect of nasal immunization with protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis on protective immune response against anthrax toxin. Vaccine. 2002;20:2836–2839. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brey RN. Molecular basis for improved anthrax vaccines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:1266–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keltel WA. Recombinant protective antigen 102 (rPA102): profile of a second-generation anthrax vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006;5:417–430. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baillie LW. Past, imminent and future human medical countermeasures for anthrax. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101:594–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang CM, Foster KW, DeSilva TS, Van Kampen KR, Elmets CA, Tang DC. Identification of Bacillus anthracis proteins associated with germination and early outgrowth by proteomic profiling of anthrax spores. Proteomics. 2004;4:2653–2661. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang CM, Shi Z, DeSilva TS, Yamamoto M, Van Kampen KR, Elmets CA, Tang DC. A differential proteome in tumors suppressed by an adenovirus-based skin patch vaccine encoding human carcinoembryonic antigen. Proteomics. 2005;5:1013–1023. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang CM, Wang CC, Kawai M, Barnes S, Elmets CA. Surfactant sodium lauryl sulfate enhances skin vaccination: molecular characterization via a novel technique using ultrafiltration capillaries and mass spectrometric proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:523–532. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500259-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang CM, Foster KW, DeSilva T, Zhang J, Shi Z, Yusuf N, Van Kampen KR, Elmets CA, Tang DC. Comparative proteomic profiling of murine skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:51–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zahn R, von Schroetter C, Wuthrich K. Human prion proteins expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by high-affinity column refolding. FEBS Lett. 1997;417:400–404. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preston KR, Dexter JE, Kruger JE. Relationship of exoproteolytic and endoproteolytic activity to storage protein hydrolysis in germinated and hard red spring wheat. Cereal Chem. 1978;55:877–888. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courcelle J, Crowley DJ, Hanawalt PC. Recovery of DNA replication in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli requires both excision repair and recF protein function. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:916–922. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.916-922.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterz ME. Temperature in agar plates and its influence on the results of quantitative microbiological food analyses. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;14:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90037-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisen MB, Brown PO. DNA arrays for analysis of gene expression. Methods Enzymol. 1999;303:179–205. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)03014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D, Urisman A, Liu YT, Springer M, Ksiazek TG, Erdman DD, Mardis ER, Hickenbotham M, Magrini V, Eldred J, Latreille JP, Wilson RK, Ganem D, DeRisi JL. Viral discovery and sequence recovery using DNA microarrays. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14863–1468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidi-Rontani C. The alveolar macrophage: the Trojan horse of Bacillus anthracis. Trends in Microbiol. 2002;10:405–409. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JS, Hadjipanayis AG, Welkos SL. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus-vectored vaccines protect mice against anthrax spore challenge. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1491–1496. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1491-1496.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flick-Smith HC, Waters EL, Walker NJ, Miller J, Stagg AJ, Green M, Williamson ED. Mouse model characterisation for anthrax vaccine development: comparison of one inbred and one outbred mouse strain. Microb Pathog. 2005;38:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brockstedt DG, Bahjat KS, Giedlin MA, Liu W, Leong M, Luckett W, Gao Y, Schnupf P, Kapadia D, Castro G, Lim JY, Sampson-Johannes A, Herskovits AA, Stassinopoulos A, Bouwer HG, Hearst JE, Portnoy DA, Cook DN, Dubensky TW., Jr Killed but metabolically active microbes: a new vaccine paradigm for eliciting effector T-cell responses and protective immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11:853–860. doi: 10.1038/nm1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grass G, Schierhorn A, Sorkau E, uller H, Rucknagel P, Nies DH, Fricke B. Camelysin is a novel surface metalloproteinase from Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 2004;72:219–228. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.219-228.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fricke B, Drossler K, Willhardt I, Schierhorn A, Menge S, Rucknagel P. The cell envelope-bound metalloprotease (camelysin) from Bacillus cereus is a possible pathogenic factor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1537:132–146. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(01)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohnsack JF, Zhou XN, Williams PA, Cleary PP, Parker CJ, Hill HR. Purification of the proteinase from group-B Streptococci that inactivates human C5a. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1079:222–228. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90129-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodgson AL, Carter K, Tachedjian M, Krywult J, Corner LA, McColl M, Cameron A. Efficacy of an ovine caseous lymphadenitis vaccine formulated using a genetically inactive form of the Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis phospholipase D. Vaccine. 1999;17:802–808. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatnagar R, Batra S. Anthrax toxin. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2001;27:167–200. doi: 10.1080/20014091096738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster SJ, Johnstone K. Pulling the trigger: the mechanism of bacterial spore germination. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:137–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauvau G, Vijh S, Kong P, Horng T, Kerksiek K, Serbina N, Tuma RA, Pamer EG. Priming of memory but not effector CD8 T cells by a killed bacterial vaccine. Science. 2001;294:1735–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1064571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Datta SK, Okamoto S, Hayashi T, Shin SS, Mihajlov I, Fermin A, Guiney DG, Fierer J, Raz E. Vaccination with irradiated Listeria induces protective T cell immunity. Immunity. 2006;25:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hijnen WA, Beerendonk EF, Medema GJ. Inactivation credit of UV radiation for viruses, bacteria and protozoan (oo)cysts in water: a review. Water Res. 2006;40:3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh M, Srivastava I. Advances in vaccine adjuvants for infectious diseases. Curr HIV Res. 2003;1:309–320. doi: 10.2174/1570162033485195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Hagan DT, MacKichan ML, Singh M. Recent developments in adjuvants for vaccines against infectious diseases. Biomol Eng. 2001;18:69–85. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0344(01)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Q, Liu D, Majewski P, Schulte LC, Korn JM, Young RA, Lander ES, Hacohen N. The plasticity of dendritic cell responses to pathogens and their components. Science. 2001;294:870–875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5543.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Shi Z, Kong FK, Jex E, Huang Z, Watt JM, Van Kampen KR, Tang DC. Topical application of Escherichia coli-vectored vaccine as a simple method for eliciting protective immunity. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3607–3617. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01836-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Regulation of phagosome maturation by signals from Toll-like receptors. Science. 2004;304:1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.1096158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson WH, DiGennaro C, Hueber W, Haab BB, Kamachi M, Dean EJ, Fournel S, Fong D, Genovese MC, de Vegvar HE, Skriner K, Hirschberg DL, Morris RI, Muller S, Pruijn GJ, van Venrooij WJ, Smolen JS, Brown PO, Steinman L, Utz PJ. Autoantigen microarrays for multiplex characterization of autoantibody responses. Nat Med. 2002;8:295–301. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Predki PF, Mattoon D, Bangham R, Schweitzer B, Michaud G. Protein microarrays: a new tool for profiling antibody cross-reactivity. Hum Antibodies. 2005;14:7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Copeland S, Siddiqui J, Remick D. Direct comparison of traditional ELISAs and membrane protein arrays for detection and quantification of human cytokines. J Immunol Methods. 2004;284:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]