Abstract

E-proteins are essential class I bHLH transcription factors that play a role in lymphocyte development. In catfish lymphocytes the predominant E-proteins expressed are CFEB (a homologue of HEB) and E2A1, which both strongly drive transcription. In this study the role of homodimerization versus heterodimerization in the function of these catfish E-proteins was addressed through the use of expression constructs encoding forced dimers. Constructs expressing homo- and heterodimers were transfected into catfish B cells and shown to drive transcription from the catfish IGH enhancer. Expression from an artificial promoter containing a trimer of μE5 motifs clearly demonstrated that the homodimer of E2A1 drove transcription more strongly (by a factor of 10–25) than the CFEB homodimer in catfish B and T cells, while the heterodimer showed intermediate levels of transcriptional activation. Both CFEB1 and E2A1 proteins dimerized in vitro, and the heterodimer CFEB1-E2A1 was shown to bind the canonical μE5 motif.

Keywords: E2A, HEB, heterodimer, IGH enhancer, B cells, channel catfish

1. Introduction

The E-proteins, class I basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors that bind specifically to the E-box consensus sequence, CANNTG (Ephrussi et al., 1985; Lazorchak et al., 2005; Murre, 2005), play key roles in a variety of developmental processes. The mammalian E-proteins are encoded by 3 genes: E2A/TCF3, which encodes by alternative RNA processing 2 proteins, E12 and E47 (Murre et al., 1989); HEB/TCF12; and E2-2/TCF4. In contrast, 5 E-protein genes E2A1, E2A2, HEB/CFEB, E2-2, and Ex have been found in teleost fish (Hikima et al., 2005a), a situation that likely reflects the whole-genome duplication believed to have occurred early in the evolution of the teleost lineage (Brunet et al., 2006). In mammals, the E-proteins are widely expressed, although not ubiquitously so (Murre, 2005). E12, E47, HEB, and E2-2 have the ability to form homo- or heterodimers with each other and with other members of the HLH protein family (Lazorchak et al., 2005; Murre, 2005). For example, in nonlymphoid developmental systems they readily form heterodimers with class II bHLH proteins such as MyoD (Blackwell and Weintraub, 1990; Sun and Baltimore, 1991). In contrast, lymphocyte development mainly utilizes E-proteins that function as homo- or heterodimers with one another (Bain et al., 1993; Sawada and Littman, 1993; Shen and Kadesch, 1995). In B lineage cells homodimers of E47 play an important role and their function is regulated in a B cell-specific manner by phosphorylation (Shen and Kadesch, 1995; Sloan et al., 1996), however heterodimers of E47 and E2-2 have also been noted (Bain et al., 1993). For thymocyte development, E47 and HEB form heterodimers (Sawada and Littman, 1993) that regulate the expression of important immune-function genes, including CD4 and T cell receptors (Sawada and Littman, 1993; Barndt et al., 2000). Heterodimers of E12 and E2-2 are also expressed in developing thymocytes and B cells (Bain et al., 1993; Corneliussen et al., 1991), although their functional significance has not been established.

In the catfish immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) locus, a single enhancer (Eμ3′) has been described. The Eμ33′ enhancer differs in structure and function from Eμ, the mammalian intronic IGH enhancer (Magor et al., 1994; 1997). The core region of Eμ33′ contains two variant octamer motifs and a consensus μE5 site that have been shown to be functionally important (Cioffi et al., 2001; Hikima et al., 2004). The major catfish transcription factors binding the octamer motifs (Oct1 and Oct2) and μE5 sites (CFEB1/2 and E2A1) have been cloned and characterized in the channel catfish (Ross et al., 1998; Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b; Lennard et al., 2007). The role of Oct2, CFEB1/2 and E2A1 in driving transcription from the Eμ33′ core region is established (Ross et al., 1998; Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b) but Oct1 in catfish appears to be a negative regulator of transcription (Lennard et al., 2007). The two CFEB proteins (CFEB1 and 2, which are alternatively spliced transcripts of the CFEB gene) have been shown to form both homo- and heterodimers by in vitro assay (Hikima et al., 2004), but the function of these dimers was not investigated. Thus the potential role of dimerization in regulating the function of catfish E-proteins has not yet been established, but by analogy with mammalian E-proteins it is assumed it plays an important role in determining cell-type specific function. The functional significance of catfish E-protein dimerization was addressed in this study by the expression of forced homo- and heterodimers of CFEB1 and E2A1.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. DNA constructs

The luciferase-expressing constructs containing pGL3/Δ56, pGL3/Δ56/R#2, or pGL3/Δ56/μE5x3 that were used in this study have been described (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b). The expression constructs for catfish CFEB1 and E2A1 (Genbank accession nos. AY528668 and AY770493)(pRc/E2A1 and pRc/CFEB1) have also been described (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b). Constructs that force the expression of E-protein dimers (E2A1/E2A1, pRc/ELE; CFEB1/CFEB1, pRc/CLC; and CFEB1/E2A1, pRc/CLE) were used for transfection and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). These constructs were produced using PCR-amplified CFEB1, E2A1, and linker region sequences. The linker primer set (cloning sites underlined) was 53′-TTT AAG CTT CCG CGG GGT ACG GGG GGT GGA TCC GG-33′ (G-3031: Forward), and 53′-TTT AAG CTT ACC TCC GCC GGA CCC TCC GC-33′ (G-3032: Reverse). The linker DNA fragments (Fig. 1A) were amplified using pFB-FL-MyoD/E12 as a template DNA (Neuhold and Wold, 1993; Dilworth et al., 2004), a kind gift of Dr. Dilworth. PCR was performed for 30 cycles with the following profile: 30s at 95°C, 15s at 58°C, and 30s at 72°C. The amplified linker fragments were cloned into the Hind III site of pRc/E2A1 or pRc/CFEB1 (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b). To insert an N-terminal E-protein, E2A1 and CFEB1 sequences (without stop codons) were amplified using the following primers that contained a cloning site (underlined) and a Kozak (Kozak, 1984) consensus sequence (italics) in the sense primer. The CFEB1 primer set was 53′-TTT CCG CGG GGC ACC ATG AAT CCT CAG CAG CGG ATC GCC GCT A-3′ (G-3033: Forward), and 5′-TTT CCG CGG CAA ATG GCC CAT GGG GTT AGA TGT GTC T-3′ (G-3037: Reverse). The E2A1 primer set was 5′-TTT CCG CGG GGC ACC ATG AAC GAT CAG CAG GGC CAC AGA ATG G-3′ (G-3035: Forward), and 5′-TTT CCG CGG TAT ATG CCC AAC AGA ACT GTG TCC ATC T-3′ (G-3038: Reverse). PCR was performed for 30 cycles using the following conditions: 15s at 94°C and 6 min at 68°C. The amplified CFEB1 or E2A1 fragments were then cloned into the Sac II site of the linker sequence (Fig. 1A). The direction and sequence of each inserted E-protein and the linker fragments in the forced dimer constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing performed with GenomeLab™ dye terminator cycle sequencing with quick start kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and CEQ™ 8000 genetic analysis system (Beckman Coulter).

Figure 1. Heterodimers of CFEB1-E2A1 drive transcription from the core region of the IGH enhancer in catfish B cells.

(A) Schematic of expression constructs for the forced dimerization (including the linker sequence) of catfish E-proteins. (B) Transcriptional activity driven from the reporter constructs by cotransfection of forced dimer expression vectors (pRc/ELE, pRc/CLC, and pRc/CLE) in the catfish B cell line (1G8). The p-values (below B) were calculated by student’s T-test (n=7). The structure of the reporter construct (pGL/Δ56/R#2) is shown at the bottom of the figure. Abbreviations: H; Hind III, S; Sac II, A/N; Apa I or Not I, E; E2A1, C; CFEB1, ELE; E2A1-Linker-E2A1, CLC; CFEB1-Linker-CFEB1, CLE; CFEB1-Linker-E2A1.

For EMSA and pull-down assays, the recombinant E-protein monomers, (CFEB1, CFEB2, and E2A1) and the CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimers were generated by the TNT T7 quick coupled transcription/translation system (Promega, Madison, WI) using pCITE/CFEB1, pCITE/CFEB1, pCITE/E2A1, and pRc/CLE as template DNAs. These pCITE vector constructs were described in previous studies (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b).

2.2. Cell lines, DNA transfection, and Luciferase Reporter Assay

The catfish B lymphoblastoid cell line 1G8 (Miller et al., 1994) and T cell line G14D were used for transfections as described previously (Cioffi et al., 2001). Equimolar amounts of construct were transfected in each experiment. Each group contained the same amount of reporter, 3.1 pM (corresponding to 10 μg for pGL/Δ56, 10.3 μg for pGL/Δ56/R#2, and 10.1 μg for pGL/Δ56/μE5x3), the same amount of expression vector, 2.19 pM (corresponding to 8 μg for the empty expression vector pRc/CMV, 11.1 μg for pRc/CFEB1, 10.9 μg for pRc/E2A1, 13.9 μg for pRc/ELE, 14.2 μg for pRc/CLC, 14.0 μg for pRc/CLE), and the same amount of Renilla luciferase construct pRL/CMV, 0.37 pM (1.0 μg) as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Optimal electroporation conditions and the luciferase assay have been previously described (Cioffi et al., 2001). Values were calculated as mean ±SE. P-values were calculated using the student’s T-test.

2.3. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The probe containing the μE5 consensus sequence in the context of the native surrounding sequence, and a corresponding probe with a scrambled μE5 site were previously described (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b). These probes were used to determine the binding ability of the CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimer. Methods for probe preparation and labeling were previously described (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b). In vitro synthesized CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimers were produced by the TNT system (Promega). The EMSA reaction mixtures contained a 2μl aliquot of 5X gel shift binding buffer (Promega) and 2 or 4μl of TNT products in a total volume of 8–9μl. These reactions were incubated at room temperature for 15 min and then 1 μl of 32P-labeled probe (105 cpm/μl, specific activity 5 x 104 cpm/ng), unlabeled competitor, or scrambled competitor (each 100 times the concentration of the labeled probe) were added. After a 30 min incubation, DNA-protein complexes were analyzed on 4% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels in 0.5X TBE buffer (45 mM Tris-HCl, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA). Gels were dried, exposed to a phosphoimager screen and analyzed using a Typhoon phosphoimager and the ImageQuant program (Amersham Biosciences).

The molecular size of recombinant CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimers was compared to CFEB1 and E2A1 monomers by SDS-PAGE using 35S-methionine labeled proteins.

2.4. Assay of E-protein Interactions

E2A1, CFEB1 and CFEB2 proteins were produced by transcription and translation using the TNT quick coupled transcription/translation system (Promega). Two forms of the proteins were synthesized: 35S-labeled proteins without an S-tag, and non-radioactive proteins with an S-tag. One hundred μl of the in vitro synthesized non-radioactive Stagged catfish E2A1 and CFEB1 were bound to 25 μl of S-protein agarose resin for 5 hours at 4°C in 500 μl of binding/washing (B/W) buffer (25mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and then washed twice with 500 μl of the B/W buffer. One hundred μl of 35S-labeled in vitro synthesized E2A1 proteins (without S-tag) were then incubated with the resin bound E2A1 and CFEB1/2 proteins for 5 hours at 4°C in 500 μl of the B/W buffer. The samples were then washed four times in 500 μl of the B/W buffer, boiled in 25 μl of 2x sample buffer and analyzed on a 7% SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was dried completely, and exposed to a phosphoimager screen for 16–20 hours, and analyzed using a Typhoon phosphoimager and the ImageQuant program (Amersham Biosciences). Western blot analysis of the synthesized proteins was performed using the S•Tag™ HRP LumiBlot™ Kit (Novagen) according to the manufacturer’s method.

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptional activation of forced E-protein dimers

The ability of constructs expressing either monomeric E-proteins (CFEB1 and E2A1) or the forced E-protein homo- and heterodimers to drive expression from the Eμ3′ enhancer core region was tested in catfish 1G8 B cells (Fig. 1A). Only CFEB1 was used for these experiments since both CFEB1 and CFEB2 possess similar transcriptional activity in catfish B cells (Hikima et al., 2004). As predicted from previous results (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b), the transfected monomeric E-proteins each effectively drove expression from this construct (Fig. 1B). The forced dimer constructs also all drove expression (Fig. 1B), with the E2A1 homodimer producing stronger expression than either the CFEB1-CFEB1 homodimer or the CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimer.

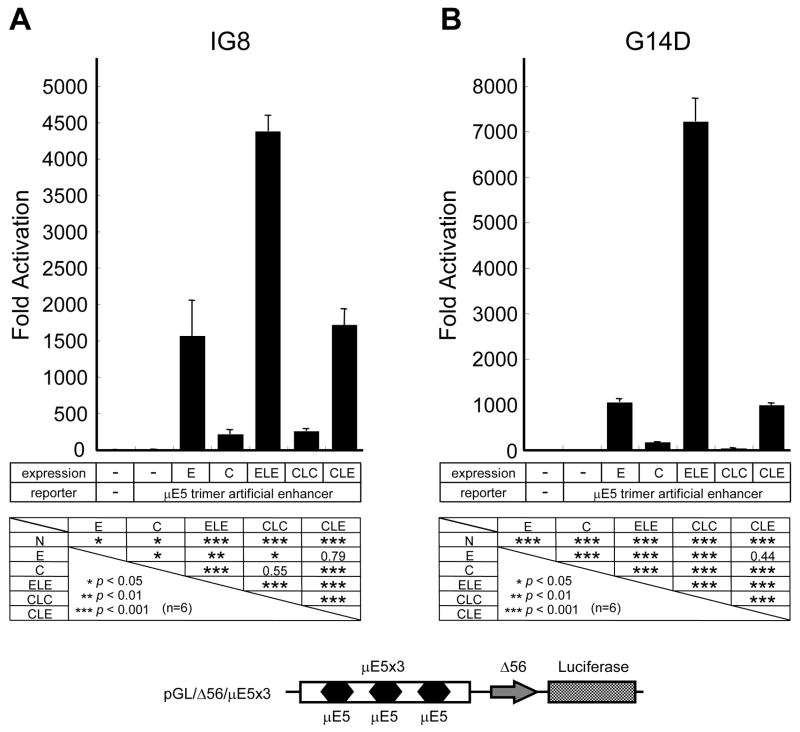

Next, to understand the potential function of dimerized E-proteins without interaction with other transcription factors in catfish lymphoid cells, the ability of the forced dimers (E2A1-E2A1, CFEB1-CFEB1, and CFEB1-E2A1) to drive transcription from an artificial promoter containing 3 copies of the μE5 motifs (Fig. 2) was tested using catfish 1G8 B cells. The results (Fig. 2A) clearly demonstrate that transfected monomeric and forced dimeric forms of E-proteins were capable of driving expression from this construct. Interestingly, the trimer of μE5 motifs is much more responsive to E2A1 than to CFEB1, whether constructs expressing the monomeric or forced homodimer forms were compared. The forced heterodimer-expressing construct showed approximately 1800-fold activation over the negative control, but it was less than half as active as the construct expressing the forced E2A1 homodimers (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Heterodimers of CFEB1-E2A1 drive transcription from a μE5-dependent reporter construct in catfish lymphoid cell lines.

Transcriptional activities in catfish 1G8 B cells (A) and G14D T cells (B) are shown. The p-values calculated by student’s T-test (n=6) are indicated below the figures. The structure of the reporter construct containing the μE5 trimer artificial enhancer (pGL/Δ56/μE5x3) is shown below.

The function of the forced E-protein dimers acting on this μE5-driven construct was also tested in catfish G14D T cells. The results (Fig. 2B) were similar to those seen using the 1G8 B cells. Although CFEB1 was active when expressed as either monomer (approximately 200-fold activation) or forced homodimer (about 1000-fold above control), E2A1 induced much stronger activation, especially when expressed as the homodimer, where it gave over 7000-fold enhancement. The heterodimer was also active in the T G14D cells, with an approximate 1000-fold enhancement observed (Fig. 2B).

3.2. The forced CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimers bind the μE5 motif

The ability of the forced CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimer to drive transcription from constructs containing the core region of the Eμ3′ enhancer (Fig. 1B) or a trimer of μE5 motifs (Fig. 2) suggests, but does not formally demonstrate, its ability to bind a μE5 site. To assess its ability to bind directly, the forced CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimer was expressed as a recombinant protein by in vitro transcription and translation, and tested for the ability to bind the μE5 motif sequence found in the native Eμ3′ enhancer (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b) by EMSA (Fig. 3). The CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimer was capable of binding the μE5 probe (Fig. 3, Lanes 1 and 2), and this binding was specific, as shown by inhibition with an excess of unlabeled μE5 motif (Lane 3), but not by an excess of scrambled μE5 sequence (Lane 4)(Fig. 3A). The SDS-PAGE analysis of the 35S-labled CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimers demonstrates that the recombinant protein expressed by the TNT system was of the predicted molecular size, when compared to E2A1 and CFEB1 monomers (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Heterodimers of CFEB1-E2A1 bind μE5 motifs.

(A) EMSA assessing the binding of in vitro produced recombinant CFEB1-E2A1 protein to μE5 motifs. (B) The molecular size of the forced E-protein dimers was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. The 35S-met labeled E2A1 monomer, CFEB1 monomer, and CFEB1-E2A1 dimer were produced in the TNT system. Molecular size markers (kDa) are shown to the left of the panels. The monomeric and dimeric shifts are indicated by black arrows.

3.3. Physical interaction between E2A1 and CFEB1/2

Although the above results show the function of the forced CFEB1-E2A1 heterodimers, the physical interactions of catfish E2A1 with CFEB1 or CFEB2 have not been addressed. To directly test homotypic and/or heterotypic interactions between E2A1 and CFEB1/2, their binding was investigated with a pull-down technique using epitope-tagged protein. In these experiments, the ability of 35S-labeled in vitro synthesized E2A1 proteins to bind to S-tagged and unlabeled E-proteins (E2A1 and CFEB1/2) was assessed by SDS-PAGE and phosphoimaging (Fig. 4A). The results show that E2A1 was capable of both homodimerization (Fig. 4A, lane 3) and heterodimerization with CFEB1/2 (Fig. 4A, lanes 6, and 9). These interactions are mediated by the E2A1 proteins and not by the epitope tag, as shown by the lack of interaction when the S-tag peptide alone was used (Fig. 4A, lanes 2, 5, and 8). Western blot analysis of the S-protein agarose-bound proteins confirmed that S-tagged recombinant proteins bind to S-protein agarose (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. The E2A1 protein can form homo- and heterodimers.

(A) Dimerization was assayed in pull-down experiments by affinity chromatography on S-protein agarose. In vitro synthesized 35S-labeled E2A1 was mixed with in vitro synthesized unlabeled Stagged E2A1, CFEB1 or CFEB2 pre-bound to S-protein agarose. Lanes 1, 4, and 7 show the input (1/100 volume) of 35S-labeled E2A1 protein. Lane 3 shows the homodimerization of E2A1. The heterodimerization of E2A1 with CFEB1 or CFEB2 is shown in lanes 6 and 9. (B) Western blot analysis of the in vitro synthesized S-tagged E2A1, CFEB1 and CFEB2, developed using S-protein conjugated with HRP. The abbreviations E, C1, C2 and S indicate E2A1, CFEB1, CFEB2, and S-tag peptide, respectively.

4. Discussion

CFEB1/2 and E2A1 are the major expressed E-proteins of catfish B cells (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b), and the data presented here, combined with previous observations, show that they are capable of forming both homotypic and heterotypic associations. As shown in this study, forced dimers of the catfish E-proteins are capable of driving transcription from μE5-dependent expression constructs both as homodimers and heterodimers.

In order to determine the significance of the present observations in our overall understanding of E-protein function in vertebrate B cells, it is important to understand the role of E-proteins in the development and function of mammalian B cells. It has been argued that E2A plays a major role in regulating B cell development and differentiation (Zhuang et al., 1994; Bain et al., 1994). This contention is supported by E47 homodimers being easily detected in B cells but not in other cell types (Shen and Kadesch, 1995). The homodimerization of E47 is B-cell specific and is regulated by posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation (Sloan et al., 1996) and disulfide bond formation (Benezra, 1994). It is also known that E47 when overexpressed in pre-T cells is able to activate immunoglobulin D-JH gene rearrangement (Schlissel et al., 1991), which further supports the importance of E47 in B cell development. However, other studies have suggested that E47 is not absolutely essential for mammalian B cell development. For example, it has been shown that HEB can functionally compensate for the loss of E2A, as shown by the rescue of B cell development in E2A-knockout mice that expressed human HEB in place of E2A (Zhuang et al., 1998), In addition, it has been suggested that B-cell development is regulated not by the level or activity of a single E-protein but by the combined influence of all 3 E-proteins (Zhuang et al., 1996). These studies suggest that there may be great flexibility in the regulation of mammalian lymphocyte function by E-proteins; such that the overall level of E-protein activity and individual gene-expression appear to be critical regulators of both B and T cell development in mammals.

Combined with previous studies on catfish E-proteins, the present results are consistent with the view that E-proteins have flexible and even interchangeable roles in B-cell function. In mammalian B cells E2A is the dominant E-protein expressed, whereas in catfish B cells CFEB1/2 dominates, with expression several fold higher than for E2A1 (Hikima et al., 2004; 2005b). The ability of the catfish CFEB1/2 and E2A1 proteins to form functional homo- and heterodimers in B cells not only points to the flexibility of E-protein function in vertebrate B cells, but also suggests that what is known about mammalian B cell development cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other vertebrates. The above findings shed light on the specific functional properties of catfish E-proteins allowing us to compare teleost E-protein function to that of mammals and is relevant to our broader understanding of the role E-proteins play in the development and function of the vertebrate immune system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeffrey F. Dilworth (University of Washington School of Medicine) for providing the DNA construct (pFB-FL-MyoD/E12) to clone the linker sequence. This work was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM62317 and R01-AI-19530). This study was also supported in part by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Hollings Marine Laboratory, National Ocean Service, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science). Publication #38 from the Marine Biomedicine and Environmental Science Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bain G, Gruenwald S, Murre C. E2A and E2-2 are subunits of B-cell-specific E2- box DNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3522–3529. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain G, Robanus Maandag EC, Izon DJ, Armsen D, Kruisbeek AM, Weintraub BC, Krop I, Schlissel MS, Feeney AJ, van Roon M, van der Valk M, te Riele HPJ, Berns A, Murre C. E2A proteins are required for proper B cell development and initiation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. Cell. 1994;79:885–892. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barndt RJ, Dai M, Zhuang Y. Function of E2A-HEB heterodimers in T-cell development revealed by a dominant negative mutation of HEB. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6677–6685. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6677-6685.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benezra R. An intermolecular disulfide bond stabilizes E2A homodimers and is required for DNA binding at physiological temperatures. Cell. 1994;79:1057–1067. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell TK, Weintraub H. Differences and similarities in DNA-binding preferences of MyoD and E2A protein complexes revealed by binding site selection. Science. 1990;250:1104–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.2174572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet BF, Crollius HR, Paris M, Aury JM, Gibert P, Jaillon O, Laudet V, Robinson-Rechavi M. Gene loss and evolutionary rates following whole-genome duplication in teleost fishes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1808–16. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi CC, Middleton DL, Wilson MR, Miller NW, Clem LW, Warr GW. An IgH enhancer that drives transcription through basic helix-loop-helix and Oct transcription factor binding motifs. Functional analysis of the Eμ3′ enhancer of the catfish. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27825–27830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneliussen B, Thornell A, Hallberg B, Grundström T. Helix-loop-helix transcriptional activators bind to a sequence in glucocorticoid response elements of retrovirus enhancer. J Viol. 1991;65:6084–6093. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6084-6093.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth FJ, Seaver KJ, Fishburn AL, Htet SL, Tapscott SJ. In vitro transcription system delineates the distinct roles of the coactivators pCAF and p300 during MyoD/E47-dependent transactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11593–11598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404192101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ephrussi A, Church GM, Tonegawa S, Gilbert W. B lineage-specific interactions of an immunoglobulin enhancer with cellular factors in vivo. Science. 1985;227:134–140. doi: 10.1126/science.3917574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikima J, Cioffi CC, Middleton DL, Wilson MR, Miller WN, Clem LW, Warr GW. Evolution of transcriptional control of the IgH locus: characterization, expression, and function of TF12/HEB homologs of the catfish. J Immunol. 2004;173:5476–5484. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikima J, Lennard ML, Wilson MR, Miller WN, Clem LW, Warr GW. Evolution of vertebrate E protein transcription factors: comparative analysis of the E protein gene family in Takifugu rubripes and humans. Physiol Genome. 2005a;21:144–151. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00312.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikima J, Lennard ML, Wilson MR, Miller NW, Warr GW. Regulation of the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus expression at the phylogenetic level of a bony fish: Transcription factor interaction with two variant octamer motifs. Gene. 2006;377:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikima J, Middleton DL, Wilson MR, Miller NW, Clem LW, Warr GW. Regulation of immunoglobulin gene transcription in a teleost fish: identification, expression and functional properties of E2A in the channel catfish. Immunogenetics. 2005b;57:273–282. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0793-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Point mutations close to the AUG initiator codon affect the efficiency of translation of rat preproinsulin in vivo. Nature. 1984;308:241–246. doi: 10.1038/308241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazorchak A, Jones ME, Zhuang Y. New insights into E-protein function in lymphocyte development. Trends Immunol. 2005;25:334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennard ML, Hikima J, Ross DA, Kruiswijk CP, Wilson RM, Miller WN, Warr GW. Characterization of an Oct1 orthologue in the channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus: A negative regulator of immunoglogulin gene transcription? BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magor BG, Ross DA, Middleton DL, Warr GW. Functional motifs in the IgH enhancer of the channel catfish. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:192–198. doi: 10.1007/s002510050261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magor BG, Wilson MR, Miller NW, Clem LW, Middleton DL, Warr GW. An Ig heavy chain enhancer of the channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus: evolutionary conservation of function but not structure. J Immunol. 1994;153:5556–5563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NW, Rycyzyn MA, Wilson MR, Warr GW, Naftel JP, Clem LW. Development and characterization of channel catfish long term B cell lines. J Immunol. 1994;152:2180–2189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins and lymphocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/ni1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C, McCaw PS, Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989;56:777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhold LA, Wold B. HLH forced dimers: Tethering MyoD to E47 generates a dominant positive myogenic factor insulted from negative regulation by Id. Cell. 1993;74:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90725-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross DA, Magor BG, Middleton DL, Wilson MR, Miller NW, Clem LW, Warr GW. Characterization of Oct2 from the channel catfish: functional preference for a variant octamer motif. J Immunol. 1998;160:3874–3882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada S, Littman DR. A heterodimer of HEB and an E12-related protein interacts with the CD4 enhancer and regulates its activity in T-cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5620–5628. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlissel M, Voronova A, Baltimore D. Helix-loop-helix transcription factor E47 activates germ-line immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene transcription and rearrangement in a pre-T-cell line. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1367–1376. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen CP, Kadesch T. B-cell-specific DNA binding by an E47 homodimer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4518–4524. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan SR, Shen CP, McCarrick-Walmsley R, Kadesch T. Phosphorylation of E47 as a potential determinant of B-cell-specific activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6900–6908. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XH, Baltimore D. An inhibitory domain of E12 transcription factor prevents DNA binding in E12 homodimers but not in E12 heterodimers. Cell. 1991;64:459–470. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90653-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y, Barndt RJ, Pan L, Kelley R, Dai M. Functional replacement of the mouse E2A gene with a human HEB cDNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3340–3349. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y, Cheng P, Weintraub H. B-lymphocyte development is regulated by the combined dosage of three basic helix-loop-helix genes, E2A, E2-2, and HEB. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2898–2905. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y, Soriano P, Weintraub H. The helix-loop-helix gene E2A is required for B cell formation. Cell. 1994;79:875–884. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]