Abstract

Neurons and their precursor cells are formed in different regions within the developing CNS, but they migrate and occupy very specific sites in the mature CNS. The ultimate position of neurons is crucial for establishing proper synaptic connectivity in the brain. In Drosophila, despite its extensive use as a model system to study neurogenesis, we know almost nothing about neuronal migration or its regulation. In this paper, I show that one of the most studied neuronal pairs in the Drosophila nerve cord, RP2/sib, has a complicated migratory route. Based on my studies on Wingless (Wg) signaling, I report that the neuronal migratory pattern is determined at the precursor cell stage level. The results show that Wg activity in the precursor neuroectodermal and neuroblast levels specify neuronal migratory pattern two divisions later, thus, well ahead of the actual migratory event. Moreover, at least two downstream genes, Cut and Zfh1, are involved in this process but their role is at the downstream neuronal level. The functional importance of normal neuronal migration and the requirement of Wg signaling for the process are indicated by the finding that mislocated RP2 neurons in embryos mutant for Wg-signaling fail to properly send out their axon projection.

Keywords: Wingless, neuron, migration, Drosophila, axon projection, Cut, Zfh1

Introduction

Neurons and their precursor cells are formed in specific locations within the developing nervous system; however, they migrate, often taking very complex routes. They eventually occupy very distinct positions within a mature brain or nerve cord. Neurons can migrate a few cell-length to several thousand cell-lengths in defined paths (neuronal pathfinding), presumably responding to internal and external cues (Wong et al., 2002). This position of a neuron is thought to have a deterministic role in the connectivity of its synaptic terminals both at the sensory and the motor ends. Perturbations in neuronal migration are known to cause neurodevelopmental defects such as smooth brain disease (reviewed in Ghashghaei et al., 2007). Thus, elucidating the mechanisms that govern the initiation, maintenance, and termination of neuronal migration is crucial for our understanding of how a functional neuronal circuitry is established in the brain during neurogenesis.

Some of the best studied examples of neuronal migration are in the vertebrate brain. For example, in the cerebral cortex, post-mitotic neurons migrate from the ventricular zones to the surface in a radial manner. In doing so, they go past the previously generated layers of neurons, ultimately reaching the surface of the cortex (Sidman and Rakic, 1973; Mochida and Walsh, 2004; reviewed in Ghashghaei et al., 2007). The olfactory neurons are another class that undergo a lengthy migration; however, in this case it is the neuroblasts generated by neural progenitor cells in the subependymal zone of the lateral cerebral ventricle that migrate via the rostral migratory stream into the olfactory bulb, where they differentiate into neurons (Kornack and Rakic, 2001).

While the migration of neurons and the diseases associated with abnormal migration of neurons has been well studied in vertebrates, very little is known about this interesting problem in Drosophila. In the developing nerve cord of the Drosophila embryo, neurons are formed from ganglion mother cells (GMCs); GMCs are formed from neuroblast (NB) stem cells (reviewed in Goodman and Doe, 1993; Bhat, 1999; Gaziova and Bhat, 2006). NB stem cells are delaminated from the neuroectoderm under the control of proneural and neurogenic genes. While much is known about the precursor cell formation, cell fate specification, lineage elaboration and axon pathfinding (reviewed in Goodman and Doe, 1993; Bhat, 1999), to our knowledge, no genetic or molecular analysis of neuronal migration in Drosophila has been previously undertaken. Thus, the migratory routes of any neuron within the nervous system, or the genes that regulate neuronal migration have not been determined.

For the past several years, we have been focusing on a typical NB lineage, NB4−2→GMC-1->RP2/sib lineage, in the ventral nerve cord of Drosophila embryo (Bhat and Schedl, 1994; Bhat et al., 1995; Bhat, 1996; Bhat and Schedl, 1997; Bhat, 1998; Wai et a., 1999; Bhat et al., 2000; Mehta and Bhat, 2001; Yedvobnick et al., 2004; Bhat and Apsel, 2004; reviewed in Bhat, 1999; Gaziova and Bhat, 2006). NB4−2 is formed as one of 30 or so NB stem cells in a hemisegment; it is formed as an S2 NB (during the second wave of NB delamination). It then generates its first GMC, GMC-1 (also known as GMC4−2a), which then divides asymmetrically into a motoneuron called RP2 and its sibling cell, the ultimate identity of which is not known. During our analysis of the elaboration of this lineage, we noticed that the RP2/sib cells undergo a complex and elaborate migratory process. We also found that this process is affected in embryos mutant for the wingless (wg) gene. Wg is a secreted signaling molecule and is shown to regulate a variety of developmental events both in invertebrates and vertebrates (reviewed in Siegfried, and Perrimon, 1994; Klingensmith and Nusse, 1994; Cadigan and Nusse, 1997). Given the general importance of this signaling pathway and the fact that this signaling pathway has never been implicated in neuronal migration in any organism, we sought to investigate its role in this process.

Others and we have shown that Wg signaling regulates the formation and identity specification of NB4−2 (Patel et al., 1989; Chu-LaGraff and Doe, 1993; Bhat, 1996; 1998; Bhat et al., 2000). We have shown that Wg regulates this process by interacting with its receptors Frizzled (Fz) and Frizzled 2 (Fz2) and repressing the expression of Gooseberry (Bhat, 1996; 1998; see also Muller et al., 1999; Bhanot et al., 1996; Chen and Struhl, 1999). In this paper, we show that loss of Wg activity in the neuroectoderm and neuroblast affects the expression of neuron-specific genes two divisions later; this, in turn, causes aberrant neuronal migration. Consistent with this conclusion is the finding that loss of function for these neuron-specific genes lead to the same migration defects as loss of function for wg. The functional importance of normal neuronal migration and the requirement of Wg signaling for the process are indicated by the finding that mislocated RP2 neurons in embryos mutant for Wg-signaling fail to properly send out their axon projection. A Wg-regulated gene expression program at the precursor cell stage appears to set in motion a chain of genetic events over a period of two additional rounds of cell division that ultimately determines when and how the progeny pair of neurons migrates to their ultimate position. It seems likely that during these migratory steps a neuron undergoes proper differentiation thereby acquiring the ability to correctly project its axon growth cone within the nerve cord.

Materials and Methods

Mutant strains, Genetics

For the analysis of wg function during migration, a temperature sensitive allele of wg, wgIL114, was used. This allele genetically and phenotypically behaves as a null allele of wg at restrictive temperatures. The fz alleles used were fzK21, fzR52 and fz1. Embryos lacking both the maternal and the zygotic fz were generated from flies that are transheterozygous for fzR52 and fzK21, fz1 and fzK21, or fz1 and fzR52. These flies are viable and lay a normal number of eggs (see Table 1). For the analysis of fz2, we used the fz2C2, a loss of function fz2allele (Chen and Struhl, 1999). For the analysis of Arm function in migration, we used two alleles of arm, armS10C and armY025. For the pan, we used pan1 allele. The various mutant and genetic combinations were generated by standard genetics. Staging of embryos was done according to Wieschaus and Nusslein-Volhard (1986).

Table 1.

Mutants for the Wg-signaling pathway affect the migration of RP2 and sib cells

| Genotype |

% hemisegments affected |

Number of hemisegments counted |

|---|---|---|

| wgIL 114/wgIL 114 | 51 | 220 |

| fzK21/fzR52 (zygotic null) | 1 | 110 |

| fzK21/fzR52 (matemal and zygotic null) | 14 | 65 |

| fzK21/fzH51 (matemal and zygotic null) | 43 | 89 |

| fz2C1/fz2C1 (zygotic null) | 18 | 76 |

| fzH51 fz2C1/fzH51 fz2C1 / (zygotic null) | 43 | 110 |

| armS10C/armS10C | 10 | 50 |

| pan1/pan1 | 24 | 82 |

| ctdb7 | 32 | 140 |

| zfh-15 | 42 | 140 |

Migration defects in various mutants in the Wg-signaling pathway.

Temperature shift experiments

wgts embryos were collected for 15 min at 18°C. These embryos were immersed in halocarbon oil, kept for appropriate durations at 29°C (horizontal bars in Fig. 3). These embryos were then shifted back to 18°C (from 29°C) and were allowed to grow in this temperature until they reached stage 13. Embryos were quickly washed with heptane (to remove the oil), fixed and stained with anti-Eve as described previously (Bhat, 1996; Bhat and Schedl, 1997). Cuticle preparations were done using the standard procedure. The stages/Hrs of development for the embryos are normalized for 22°C by looking at the stages of development when the embryos are scored. See slegend to Figure 3 for scoring details.

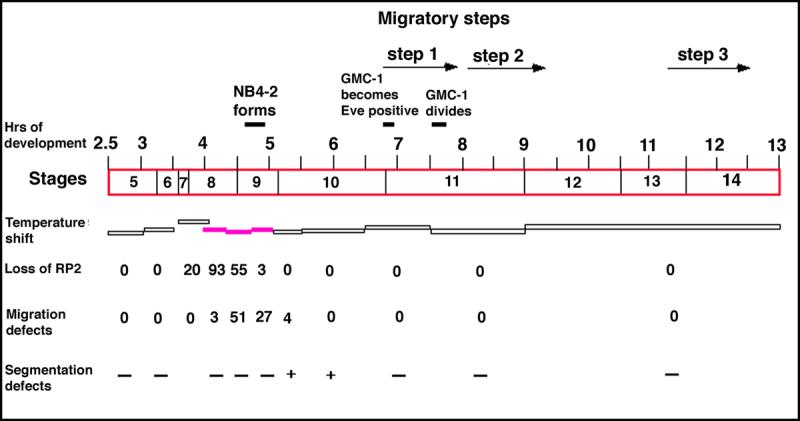

Figure 3. Wg requirement for the proper migration of GMC-1->RP2/sib cells is in the neuroectoderm/NB4−2.

Handpicked wgts mutant embryos at different developmental time points were shifted from the permissive 18°C temperature to the restrictive 29°C temperature and then shifted back to the permissive temperature. The duration at which the embryos were kept at the restrictive temperature is indicated by the horizontal bars. The filled in horizontal bars indicate sensitive period for the defect. These embryos were stained for Eve to determine the migration defects. The timings and stages correspond to developmental time/stages at 22°C; the numbers represent the percentage of hemisegments affected (number examined=220−300 per temperature-shift experiment). For example, when embryos were shifted to 29°C between 4.3−4.7 hours of developmental period, 55% of hemisegments were missing the RP2s; the percentage of migration defects indicate the defects for the remaining hemisegments where the RP2s were present. Segmentation defects were examined by cuticle preparation; at least 50 embryos were examined per temperature-shift experiment and minus symbol (−) indicates 4% or less showing the cuticle defect.

Immunohistochemistry

Standard immunostaining procedures were used with some modifications; modifications to the general fixation conditions and staining can be obtained by request. Embryos were fixed and stained with the following antibodies: Eve (rabbit, 1:2000 dilution), Eve (mouse, 1:5), Zfh1 (mouse, 1:400), 22C10 (mouse, 1:4), LacZ (rabbit, 1:3000 or mouse, 1:400), BP102 (mouse 1:10) FasII (mouse; 1:5). Other details can be obtained by request. For confocal microscopy of embryos, cy5 and FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were used. For light microscopy, alkaline phosphatase or DAB-conjugated secondary antibodies were used.

Results

The GMC-1→RP2/sib cells have a complex migratory path

In this work, the NB4−2→GMC-1->RP2/sib lineage (Thomas et al., 1984; reviewed in Bhat, 1999; Gaziova and Bhat, 2006) was used to study neuronal migration as well as the role of Wg signaling in neuronal migration. This lineage is a very well studied lineage and it has been shown that Wg-signaling pathway regulates the formation and identity specification of the parent neuroblast stem cell, NB4−2 (Chu-LaGraff and Doe, 1993; Bhat, 1996; Bhat, 1998). NB4−2, formed at around 5 hours of development at 25°C in row 4, column 2, divides at ∼6.5 hours of development to generate its first GMC, GMC-1. The GMC-1 asymmetrically divides at ∼7.5−7.45 hours of development at 25°C to generate an RP2 and a sib. By 13 hours of development, both the RP2 and the sib occupy very specific positions within the nerve cord.

To determine the migratory routes of GMC-1, RP2 and sib in wild type, we double stained wild type embryos for Even-skipped (Eve) and Wg. Wg is expressed only in row 5 NBs and its neuroectoderm, adjacent to the row from which NB4−2 is derived; it is not expressed in NB4−2 or in GMC-1 and its two progeny (Fig. 1A; see also Bhat, 1996; 1998). Eve, on the other hand, is expressed in GMC-1, a newly formed RP2 and sib, and in RP2; sib begins to lose its Eve expression soon after formation and thus, only the RP2 is positive for Eve in a 14 hr old embryo (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1A-G, we examined these double stained wild type embryos at different developmental time points beginning with the GMC-1 stage. Since Wg stains row 5 cells, it serves as a very good positional marker. Moreover, row 5 cells border the parasegmental boundary along the anterior-posterior (AP) axis, and these Wg-positive stripe of cells do not shift their position in any significant manner during development.

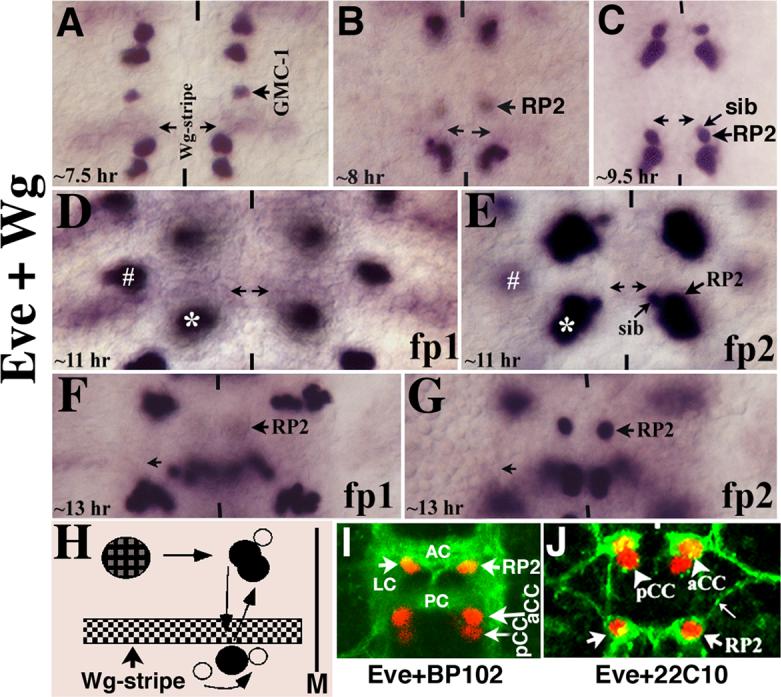

Figure 1. GMC-1->RP2/sib cells follow a complex migratory path.

Anterior end is up, midline is marked by vertical lines. All are wild type embryos in these panels. Panel A: The GMC-1 has already migrated several cells length towards the midline by 7.5 hours of development, though this Step 1 migration is not yet completed as the cell will migrate even further towards the midline. Panel B: The RP2/sib cells have begun their Step 2 posterior migration. The cells are slightly out of focus in this panel in order to show the Wg stripe (arrows). Panel C: The RP2/sib cells have reached the end of Step 2 migration; the Wg stripe is out of focus in this panel. Panels D and E: Two different focal panes (fp) of the same segment, in panel D, the Wg stripe is shown, whereas in panel E, the RP2/sib cells are shown. The two cells stay in this position for close to 2 hours and then they begin their Step 3 anterior migration. The asterisk marks Us/CQ neurons (just above the aCC/pCC pair) and the hash marks the EL neuron cluster. Panels F and G: Two different focal planes of the same segment; the RP2 neuron has migrated anterior to its ultimate position; the sib cell has lost its Eve expression by this time. Panel H: The migratory route of GMC-1->RP2/sib cells. The GMC-1 first moves toward the midline (M; Step 1 migration), it divides to generate an RP2 and a sib. Both RP2 and sib migrate to the posterior, parallel to the midline; they both cross the Wg stripe (and therefore the parasegmental boundary). The sib then moves toward the midline and to the anterior; it resides just about in the region of Wg stripe. The RP2 migrates anterior, it crosses the Wg stripe (the parasegmental boundary) and resides close to the original position from which it started the posterior migration. Panel I: Wild type embryo stained with Eve and BP102. AC, anterior commissure; PC, posterior commissure; LC, longitudinal connective. Panel J: Wild type embryo stained with Eve and 22C10, thin arrow indicates the ipsilateral RP2 axon projection.

Soon after its formation, the GMC-1 begins its migration toward the midline, parallel to the Wg expressing row of cells (compare Fig. 1A and B). In fact, the aCC/pCC clusters also migrate toward the midline. During this initial migration, the GMC-1 divides to generate an RP2 and a sib, and both these cells continue their migration toward the midline in the same path (we have named this Step 1 migration). Both RP2 and sib cells stop Step 1 migration approximately two to three neuroectodermal cells away from the midline and begin their second, or Step 2, migration. In this step, RP2 and sib cells move in the posterior direction, parallel to the midline and perpendicular to the cells expressing Wg. By ∼9.5 hours of development, both RP2 and sib cells have crossed the rows of Wg expressing cells (marked by two horizontal arrows; the Wg-cells are out of the focal plane); these cells then stop their posterior migration and reside right posterior to the Wg stripe (Fig. 1C). By 11 hours of development, the sib rotates around the RP2 to reside closer to the midline (Fig. 1E). Soon after, the RP2 (but not the sib) migrates in the anterior direction (Step 3), more or less parallel to the midline, crosses the Wg stripe again and resides in the location where the RP2 and sib had initially started their posterior migration (Fig. 1F and G). Note that the step 3 migration of sib is different from the step 3 migration of an RP2. These migratory steps are summarized in Fig. 1H. As shown in Fig. 1, panels I and J, double staining of embryos with Eve and BP102 (a monoclonal antibody that stains the commissures and connectives) or Eve and 22C10 (a monoclonal antibody against MAP1B/Futsch, which stains the membranes of RP2), reveal that an RP2 occupies the inner armpit of the anterior commissure and sends out its axon to the inter-segmental nerve bundle. (We could not visualize the migration of RP2/sib cells in live embryos using the Green Florescent Protein since it takes ∼3 hours for the Green Fluorescent Protein to become fluorescent after it is made, which makes it too late for this purpose.) In contrast to RP2/sib cells, other Eve-positive neurons such as aCC/pCC, Us and ELs undergo very little movement; CQs however, appear to undergo a postero-lateral migration (data not shown). These facts, taken together with the finding that RP2/sib pairs cross and re-cross the Wg-stripe (and thus the parasegmental boundary) argue that the migration of RP2/sib cells is not a passive movement brought about by the developing nerve cord such as formation of a new row of NBs, GMCs, neurons, etc., but that it is an actively guided process (see Discussion).

Loss of Wg activity from the neuroectoderm and NB4−2 disrupts the migration of GMC-1→RP2/sib cells

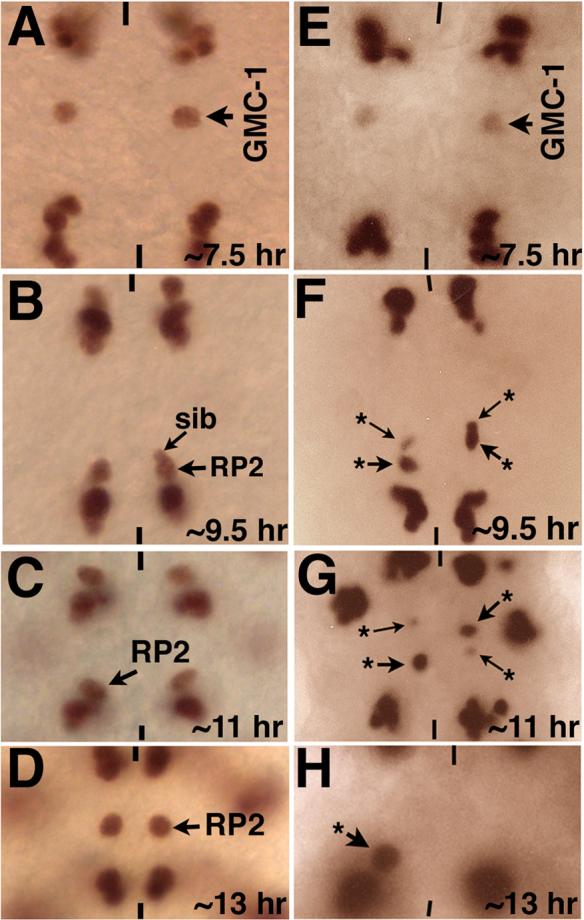

During the course of our work on Wg, I noticed that the location of RP2 neurons is disturbed in wg mutants. In order to explore the role of Wg in neuronal migration, wg mutant embryos from a temperature sensitive allele of wg where embryos are shifted to restrictive temperature during neurogenesis were examined. While the GMC-1 was formed correctly in its normal location, it exhibited defects in subsequent migratory steps (Fig. 2 and Table 1). While its initial Step 1 migration toward the midline was not significantly affected (Fig. 2E), Step 2 migration was affected. We found that both the RP2 and the sib failed to complete their posterior migration (Fig. 2F, arrow with star). Moreover, in a subset of hemisegments, the Step 3 migration -- migration of sib and the anterior migration of RP2--was affected (Fig. 2G and H). In those instances, the RP2 stayed in row 5/6, right anterior to the aCC/pCC cells of the posterior neuromere instead of moving back to row 4 (Fig. 2H). These various step 2 and step 3 migration defects were observed in about equal frequency (47% and 53%; n=580 hemisegments).

Figure 2. Migration of GMC-1->RP2/sib cells is affected in wg mutants.

Embryos in panels A-D (wild type) are stained with Eve antibody and embryos in panels E-H (wg mutant) are stained with Eve and Wg antibodies. Wild type embryos shown in panels A-D are shifted the same way as mutantembryos. Anterior end is up, midline is marked by vertical lines. Panels A-D are wild type, panels E-H are wgts mutants. The Wg activity was inactivated by shifting mutant embryos to 29°C just about NB4−2 is formed (see Materials and Methods). Panel A: The GMC-1 has migrated several cell-lengths towards the midline. Panel B: The RP2/sib cells have migrated posterior towards the aCC/pCC and U/CQ cluster. Panel C: The RP2/sib cells have completed their Step 2 migration and are located very close to the aCC/pCC and CQ cluster. Panel D: The RP2 neuron has completed its Step 3 migration and is located in its ultimate position. Panel E: The GMC-1 has migrated several cells length towards the midline, but this Step 1 migration is not yet completed. Panels F-H: The RP2/sib cells show incomplete Step 2 (panels F, G) and Step 3 (panel H) migrations. Arrow with an asterisk indicates aberrantly migrated RP2/sib cells.

We entertained two possibilities of how loss of Wg-signaling could affect RP2/sib migration. It could affect the genes required for the migration such as cell-adhesion molecules during different migratory steps. Alternatively, it could indirectly affect migration by affecting the gene expression program in RP2/sib cells prior to or during migration. To address this issue, we determined the temporal requirement of Wg for the migration of RP2 using the temperature sensitive allele of wg. We sought to determine if the temperature sensitive periods (tsp) would coincide with the different migratory steps. Therefore, embryos were shifted to the restrictive 29°C at different time points during development, kept in this temperature for a short period of time, and then shifted back to the permissive temperature (see Fig. 3). The location of the RP2 neurons was determined by anti-Eve staining. As shown in Figure 3, we found that the tsp for the migration defects maps to between 4.5−5 hours of development. Remarkably, this tsp corresponds to the time prior to and during the formation of NB4−2. Previous results have shown that the identity of NB4−2 is specified at the neuroectodermal level, prior to its formation (Chu-LaGraff and Doe, 1993; Bhat, 1996; Bhat et al., 2000). This result indicates that the requirement of Wg for the migration of RP2/sib cells closely overlaps with the Wg requirement for the formation and specification of NB4−2. Migration of these cells was not affected when later stages of embryos were shifted to restrictive temperatures. Therefore, these results show that the ectodermal/segmentation defects do not alter the migratory behavior of GMC-1 and its progeny.

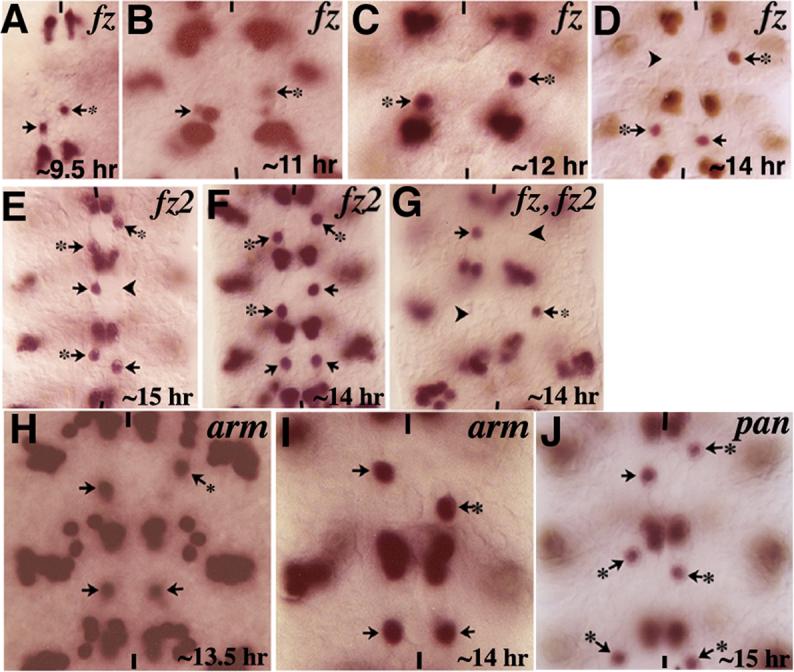

Loss of function for the downstream components of Wg signaling also disrupts the migration of RP2/sib cells

Wg signal is transmitted from the outside into the inside of a receiving cell via its receptors Frizzled (Fz) and Frizzled2 (Fz2)(Bhanot et al., 1996; Bhat, 1998; Muller et al., 1999; Bhanot et al., 1999; Chen and Struhl, 1999; see also Adler et al., 1990). We next examined if the migration of the RP2 neuron is affected in embryos that are mutant for fz and fz2. As shown in Figure 4 and Table 1, embryos that are fz or fz2 single mutants and fz fz2 double mutants showed the same migration defects as wg mutants (Fig. 4A-G). Since embryos lacking zygotic fz and fz2 genes showed migration defects in as many as 43% of the hemisegments (see Table 1), there must be a partial genetic redundancy between the two genes. Please note that loss of Fz or Fz2 activity also causes missing RP2s in a partially penetrant manner (Fig. 4D and E; see Bhat, 1998).

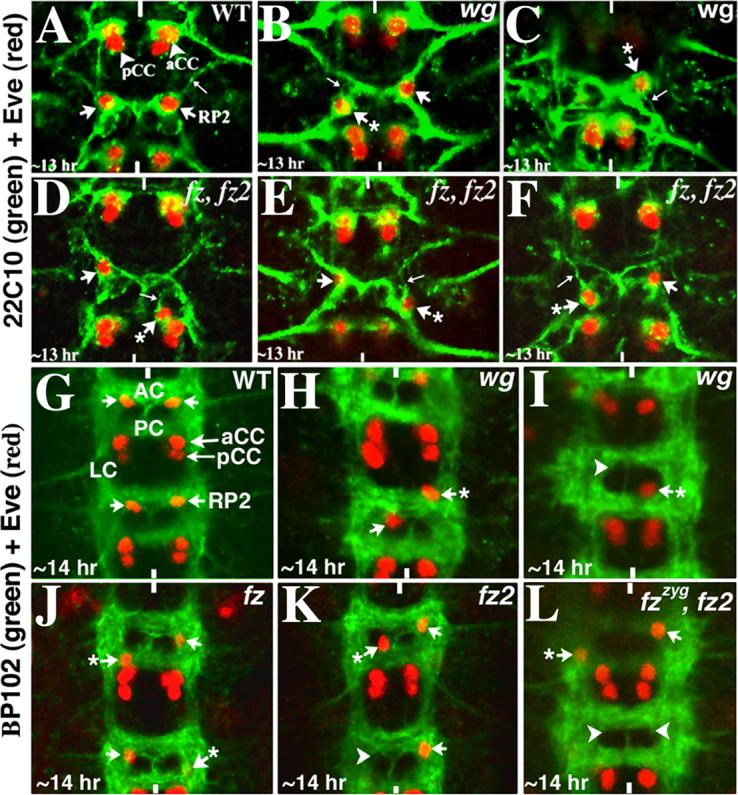

Figure 4. Migration of GMC-1->RP2/sib cells is affected in mutants for genes in the Wg-signaling pathway.

Embryos are stained for Eve. Anterior end is up, vertical lines indicate the midline. Panels A-D: Embryos mutant for the zygotic fz showing the RP2/sib migration defects (arrows with star). Note the occasional missing RP2 (panel D, arrowhead). Panels E and F: Embryos mutant for fz2 showing the RP2/sib migration defects (arrow with star); RP2s are occasionally missing as well (arrowhead in panel E). Panel G: Embryo double mutant for zygotic fz and fz2 showing the RP2/sib migration defects (arrows with star) and missing RP2s (arrowheads). Panels H and I: Embryos mutant for zygotic arm, armY025 (panel H), and armS10C (panel I). Panels J: Embryo mutant for pan showing the RP2/sib migration defects (arrows with star). Note that consistent with our previous finding (Bhat, 1998) and contrary to a subsequent paper (Chen and Struhl, 1999), both fz and fz2 single mutants have missing RP2s in a partially penetrant manner (see also Fig. 5).

During neurogenesis, the Wg-signaling pathway regulates downstream events by preventing Shaggy/Zeste white 3 from phosphorylating Armadillo (Arm), the homologue of B-Catenin). The hypo-phosphorylated Arm associates with Pangolin (Pan)/TCF-1/LEF-1 and together, they translocate to the nucleus and activate downstream target genes such as sloppy paired to specify NB4−2 identity (Peifer et al., 1994; van de Wetering, 1997; Brunner et al., 1997; Riese et al., 1997; Miller and Moon, 1996; Bhat et al., 2000; reviewed in Bhat, 1999). We determined if this pathway also mediates the migration of the RP2 neuron. As shown in Figure 4 and Table 1, embryos mutant for zygotic arm (Fig. 4H, I) or zygotic pan (Fig. 4J), showed the same migration defects as wg or fz mutants. Note that two different alleles of arm and two different alleles of pan show the same migration defects. Also, since loss of pan affects the migration of RP2, it is unlikely that Wg regulates migration by regulating the junction bound Arm. Finally, consistent with the results from the analysis of wg mutants, the migration and positioning of aCC/pCC or other Eve-positive neurons was not affected in any of these mutants. The aCC/pCC pair, for example, is generated by NB1−1, which is not one of the NBs affected in wg mutants.

Mislocated RP2 have abnormal axon projection pattern

We next determined whether the axon projection of mislocated RP2s in wg mutant embryos is affected by visualizing the axon projection pattern of RP2 with Mab22C10 (Fujita et al., 1982), which is against MAPIB/Futsch. Mab 22C10 stains the cell membrane of a differentiated RP2, as well as its axon projection (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5A, a normal RP2 projects its axon in an antero-lateral direction, which then fasciculates with the postero-lateral projection of an aCC to make up the ipsileteral nerve bundle. The process of axon elongation is believed to start at around 9−10 hours of development. As shown in Fig. 5B and C, the projection of a mislocated RP2 was affected in wg mutants. For example, one can observe a mislocated RP2 that had projected its axon initially in the anterior direction but then toward the midline (Fig. 5B), or an RP2 with its axon projected in the posterior direction (Fig. 5C). Similarly, projection patterns of mislocated RP2s were also abnormal in embryos mutant for fz or fz2 (data not shown) or in fz fz2 double mutants (Fig. 5D-F). About 69% of the mislocated RP2s had projection defects (n=330). These results argue that a mislocated RP2 has an altered axon projection pattern; however, we also entertain the possibility that such altered projections are due to a mis-specification of RP2 identity, or a combination of both. While the tested RP2 markers (Eve, Zfh1, 22C10) were expressed in these mislocated RP2s, there can still be other genes whose expression is affected in these mutants. Furthermore, about 5% of those RP2 neurons located in their normal position (n=330) showed aberrant axon projection. However, the caveat is that since the ultimate location of an RP2 is the same as the location of the RP2 prior to its step 2 migration, some of these RP2 that occupy a normal position can still be defective in migration.

Figure 5. Aberrant axon projections in mislocated RP2s.

Anterior end is up, vertical lines mark the midline. Embryos in panels A-F are double stained for Eve (Red) and 22C10 (Green), whereas embryos in panels G-L are doubled stained with Eve (Red) and BP102 (Green). AC, anterior commissure; PC, posterior commissure, LC, longitudinal connectives. Panel A: Wild type embryo showing the axon projection of RP2 (thin arrow); this projection fasciculates with the projection from aCC. Panels B and C: wgts mutant embryos; mislocated RP2s (arrows with star) have aberrant axon projections (thin arrows). Panels D-F: fz fz2 double mutant embryos; mislocated RP2s (arrows with star) have aberrant axon projections (thin arrows). Panel G: Wild type embryo, the RP2 is located at the inner armpit of AC. Panels H and I: wgts mutant embryos showing the mis-localization of RP2 neurons (arrow with star), note the occasional missing RP2 (arrowhead). Panels J-L: Embryos mutant for fz, fz2 or fz fz2 double mutants are shown with mislocated RP2s (and occasional missing RP2s indicated by arrowheads).

We felt that an abnormal commissural architecture can also affect the location of neurons within the nerve cord. Therefore, we next determined whether those hemisegments of wg mutant embryos where the RP2 neuron is mislocated have abnormal commissural architecture. Mutant embryos were double stained with BP102 and Eve. BP 102 stains the longitudinal connectives as well as the two commissures, anterior and posterior (see Fig. 5G). In wild type, RP2 neurons occupy a very specific location within the segment, the inner armpits of the anterior commissure (Fig. 5G). As shown in Fig. 5G-L, examination of embryos mutant for wg (the temperature sensitive wg allele was used) or for the two-fz genes show that the commissural tracts or the connectives are not significantly affected in these mutants. However, RP2s are still mis-routed to aberrant locations in the commissures/connective. In some instances, the RP2 either did not undertake the posterior migration (Fig. 5H, arrow with a star), or it had failed to migrate towards its normal anterior location (Fig. 5I, arrow with a star). Similar defects were also observed in embryos mutant for fz or fz2, or in embryos double mutant for fz and fz2 (Fig. 5J-L, arrows with a star). Moreover, consistent with the Eve staining results, the positioning of the aCC/pCC neuronal pair was not affected in these mutants. This indicates that the defect is specific to RP2 neurons.

Zfh1 and Cut requirements for RP2 migration

Our results show that the temporal requirement of Wg for the migration (see Fig. 3) overlaps with its temporal requirement for NB4−2 formation/identity specification. This result suggests that loss of Wg activity within the neuroectoderm/NB4−2 affects aspects of cell identity necessary for the proper migration of progeny cells one or two cell divisions later. If this scenario were correct, it would mean that the Wg signaling in the neuroectoderm/NB4−2 sets in motion a genetic program that determines the complex migratory behavior of the GMC and its progeny one to two divisions later. To determine if this is indeed the case, we examined wg mutant embryos for the expression of Cut and Zfh1, two RP2-specific transcription factors (Mehta and Bhat, 2001; our unpublished data). Cut is not detectable in GMC-1 or newly formed RP2/sib cells (Fig. 6A and B); but it is expressed soon after in the RP2 and continues to be present in a differentiated RP2 (Fig. 6E, F). Similarly, Zfh1 is also not expressed in a GMC-1 but it is expressed in a newly formed RP2 (Fig. 6C and D); it continues to be expressed in a differentiating RP2 as well as in a fully differentiated RP2 (Fig. 6K, L). Both Cut and Zfh1 are not present at detectable levels in a sib as indicated by immunostaining (Fig. 6B and D).

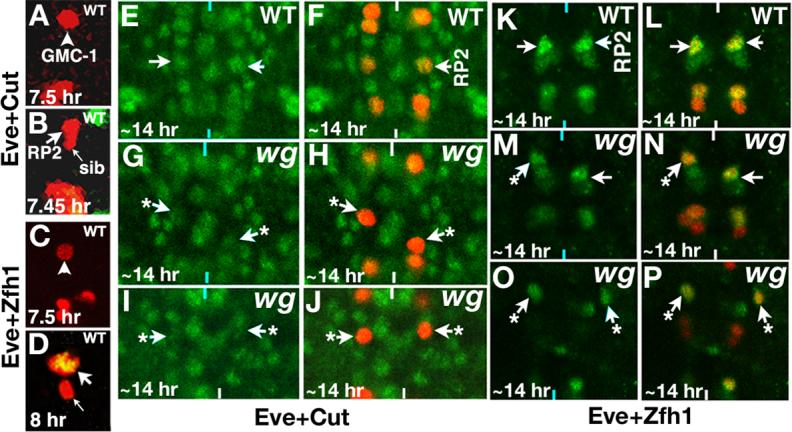

Figure 6. Expression of neuron-specific genes is affected in wg mutants.

Anterior end is up, vertical lines mark the midline. The Wg activity was inactivated by shifting mutant embryos to 29°C just about NB4−2 is formed. Panels A and B: Embryos are double stained for Eve (Red) and Cut (Green); no detectable Cut is present in GMC-1 (panel A) or a newly generated RP2 and sib (panel B), but Cut is present at high levels in a differentiated RP2; Cut appears in an RP2 by ∼8 hours of development. Panels C and D: Embryos are double stained for Eve (Red) and Zfh1 (Green); no detectable Zfh1 is present in GMC-1 (panel C), but a newly generated RP2 has Zfh1 but not sib (yellow indicates co-localization of both Eve and Zfh1, panel D). Embryos in panels E-J are double stained for Eve (Red) and Cut (Green) and K-P are double stained for Eve (Red) and Zfh1 (Green). Panels E and F: Wild type embryo, note the levels of Cut in RP2 neurons. Panels G-J: wg mutant embryos showing mislocated RP2s (arrows with star) with reduced levels of Cut. The confocal images in Panels E-J were collected using the exact same settings. Panels K and L: Wild type embryo, note the levels of Zfh1 in RP2 neurons. Panels M-P: wg mutant embryos showing mislocated RP2s (arrows with star) with reduced levels of Zfh1. The confocal images in panels K-P were collected using the exact same settings. The aCC/pCC pairs are out of focus in panel N (left hemisegment) and we see U neuronal cluster due to some unevenness of the nerve cord in the mutant. We used the same settings for collecting images from the mutants as for collecting images from the wild type controls, and expression of Cut and Zfh1 in other cells in the nerve cord was also used as reference.

Using Eve as a second antibody to visualize RP2, we found that those RP2 neurons that had migrated to wrong positions in wgts mutant embryos showed very little of Cut expression (Fig. 6G/H and I/J, arrows with a star show mis-routed RP2s; two different segments of wg mutant embryo are shown), indicating that their neuron-specific gene expression is affected. Similarly, examination of the mutant embryos for Zfh1 expression indicates that RP2s with migration defects had much lower levels of Zfh1 (Fig. 6M/N and O/P, arrows with a star show mis-routed RP2s; two different segments of wg mutant embryo are shown); whereas RP2s that had migrated to normal locations in the same embryo had normal (high) levels of Zfh1 (Fig. 6M and N, arrows). However, none of the RP2s that migrated to wrong locations were completely Zfh1 negative. In about 11% of the cases (n=220), a mislocated RP2 was found to have close to wild type levels of Zfh1 (Fig. 6P, right hemisegment); this was also the case with Cut (∼6% of the cases, n=220). This is expected since loss of Wg activity is likely to affect not just Cut and Zfh1 but additional as yet unidentified downstream genes. In those hemisegments with mislocated RP2 but expressing normal Cut and Zfh1, expression of additional genes necessary for proper specification of RP2 identity are likely to be affected.

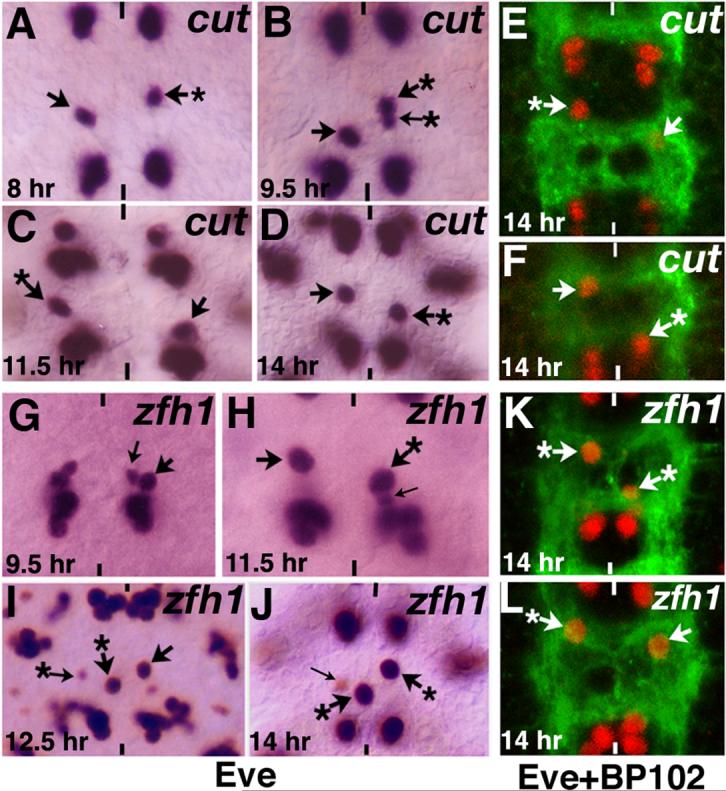

Given the above results, one should expect to observe RP2 migratory defects in embryos mutant for cut and zfh1. Therefore, we examined the migration of RP2s in these mutant embryos. As shown in Figure 7, the same type of Step 2 and Step 3 migration defects were observed in cut and zfh1 mutant embryos (see also Table 1) with about equal distribution. We also observed one intriguing result: the migration of sib was also affected in embryos mutant for cut or zfh1. Since both Cut and Zfh1 are not detectable in GMC-1 or sib but only in RP2, we entertain one of three possibilities. One, the GMC-1 or the sib do express Cut and Zfh1 but at very low levels. Two, RP2 influences the migration of sib--whenever the migration of RP2 is affected, the migration of sib is also affected. Three, loss of function for cut and zfh1 alters the environment/cells with which a sib interacts during its migration, thereby affecting the migration of sib. However, we observe a correlation between migration defect in RP2 and migration defect in sib, that is, nearly 95% of the times the migration of the RP2 is affected, so also is the migration of the sib (n=540 hemisegments: we examined 540 hemisegments where the migration of RP2 is affected for the migration of sib in these mutants). Both the step 2 and step 3 migrations of sib were affected in these hemisegments. Therefore, a non-cell autonomous dependency of sib on RP2 for proper migration is a distinct possibility. Using the same argument, it is also possible that Cut and Zfh1, which are also expressed elsewhere in the nerve cord, can influence the migration of RP2/sib cells in a cell non-autonomous manner.

Figure 7. Loss of function for cut and zfh1 causes similar migration defects as loss of function for wg.

Anterior end is up, vertical lines mark the midline. Arrow indicates normal RP2, arrow with star indicates RP2s with migration defects, thin arrow indicates sib. In some of the panels the sib is not visible since it is hidden under the RP2 (panels A, B, C, H) and occasionally a sib is visible with Eve even in 14 hr old embryo (cf., panel J). Panels A-F are cut mutant embryos and panels G-L are zfh1 mutant embryos showing the various RP2/sib migration defects. Embryos in panels A-D and G-J are stained with Eve; embryos in panels E, F and K, L are double stained with Eve (Red) and BP102 (Green).

Discussion

Results described in this paper show that neurons in the ventral nerve cord of Drosophila embryo can undertake complex migratory pathfinding in response to various cues. While many of the genes well studied in Drosophila, such as Slit, have been shown to regulate neuronal migration in vertebrates (reviewed in Wong et al., 2002; Ghashghaei et al., 2007), to our knowledge, this is the first report describing neuronal migration in Drosophila. This is also the first work, to our knowledge, to provide insight that the neuronal migration is determined at the precursor stage itself and that a mislocated neuron has aberrant axon projection. These phenomena are likely to be true in other organisms as well, including vertebrates. The results show that one of the best studied neuronal lineages, the NB4−2→GMC-1->RP2/sib lineage, exhibits a very complex migratory behavior, including crossing over the parasegmental boundary and re-crossing it, ultimately settling in a specific position within the nerve cord. Our results also show that while the initial migratory step that occurs at the GMC-1 level does not appear to be under the strict control of Wg-signaling, the later events are regulated by the Wg signaling. The Wg signaling, however, sets in motion a genetic program within the neuroectoderm and neuroblast well ahead of the actual migratory events, to regulate the migratory behavior of cells two divisions later. Proper migration of neurons appears to be necessary for their correct axon projection. It seems likely that a neuron undergoes further development during its migration and acquires the ability to project its growth cone and function properly. Finally, the partial penetrance of the defects in the mutants for the Wg-signaling indicates that there is either a genetic redundancy for this pathway, or in the case of wg mutant, there is still some Wg activity retained at the non-permissive temperature.

The complex migratory pathfinding by GMC-1->RP2/sib cells

The GMC-1>RP2/sib cells undertake a very reproducible and an unusual migratory route in the ventral nerve cord. While the initial Step 1 migration appears to be also undertaken by other neurons such as the other Eve-positive neuronal pair, aCC/pCC, the subsequent Step 2 and Step 3 migrations appear to be specific to the RP2/sib cells and not any of the other Eve-positive lineages such as aCC/pCC, Us, or ELs (CQs undergo a small postero-lateral migration). Furthermore, the RP2/sib pairs cross and re-cross the Wg-stripe (and therefore the parasegmental boundary) during this process. These results argue that the migratory process is highly specific and programmed and not due to changes occurring during neurogenesis, such as being passively moved around by the generation of new cells, or due to extension and retraction of the germband. It is also unlikely due to the condensation of the nerve cord, or an effect due to segmentation of the ectoderm. The aCC/pCC pair more or less stays in the same place throughout development once they are formed; the Wg-stripe also stays the same position, both at the nerve cord as well as the ectodermal levels, therefore these serve as reference points for the RP2/sib migration. Moreover, the complexity of the migratory routes of RP2 and sib themselves (note that the final steps of migration of sib are different from that of an RP2) argue against a passive event. Finally, the fact that loss of function for the various players in the Wg-signaling as well as loss of function for Cut and Zfh1 alters the migration of these cells, also argue against a passive event.

Furthermore, aCC/pCC neurons are formed from an S1 NB, slightly earlier than an RP2/sib (which is formed from a S2 NB), therefore, the nerve cord is somewhat more “spacious” compared to the nerve cord when the RP2/sib pairs are formed. Thus, the aCC/pCC should exhibit a more passive jostling movement compared to RP2/sib. But aCC/pCC cells do not migrate very much, arguing that the migration of RP2/sib is an active process. Similarly, the sibling pair, dMP2 and vMP2, are formed in the same row as RP2/sib and very next to the RP2/sib GMC (but slightly earlier than the RP2/sib), and these pairs do not show the same complex migratory behavior as RP2/sib (data not shown).

However, one might think that the initial Step 1 migration is a passive event since the GMC/aCC/pCC also migrate toward the midline (I want to point out here that we have mutants that show a loss of Step 1 migration for GMC-1 of the RP2/sib cells but not the GMC/aCC/pCC cells; data not shown). Having said this, there still is a possibility that the migration of RP2/sib cells is not an active process but simply the net result of “jostling” as surrounding cells undergo development. It would have been better if information on the cellular structure of RP2 and sib and the cells that surround them can be obtained; morphology or polarity of RP2 during these movements might help determine whether RP2 displays the features of a migrating cell. However, there are no good markers that would reveal these characteristics of RP2/sib cells, therefore, we have not done these experiments.

A more intriguing question, however, is the reason for these cells to undergo these complex migratory steps since the RP2 come to reside in the same approximate position as it starts its posterior migration (the sib, however, resides in a location more posterior to RP2). One major finding that suggests a functional role for this migration is the fact that RP2s that fail to undertake a normal migration fail to project their axon tracts correctly (Fig. 5B-F). During axonogenesis, an RP2, for example, extends and retracts many neurites, one of which at the ipsilateral location eventually grows into an axon. A positional specificity for axonogenesis thus exists. Perhaps these migratory steps help define the site of axonogenesis: the ipsilateral neurite growing into an axon. Any aberrant migration (or no migration, Step 2 and Step3, that is) will make it such that the correct ipsilateral neurite is unable to grow into an axon. One tempting speculation is that the RP2 neuron also rotates during the migration and this rotation has a deterministic role in a specific neurite growing into an axon. A migrating RP2 also encounters other cells in the posterior rows and this may have an instructive role for the normal differentiation of RP2. One obvious question is against which cells these neurons migrate. It seems likely that these cells migrate against the surfaces of other cells within the CNS (i.e., neuroblasts, GMCs, neurons and glial cells).

Wg signaling in RP2/sib migration

Our results show that Wg-signaling regulates RP2/sib migration. Thus, loss of function for the various players in the Wg-signaling pathway affects the migration of RP2/sib cells in the same way. It must be pointed out that in these mutants, the RP2/sib migration is not arrested at one specific point, but at varied points. This is most likely due to a partial redundancy for these mutants. The wg allele used is a ts allele and a complete loss of Wg activity leads to loss of RP2/sib cells. Similarly, fz has partial redundancy with fz2, and there is maternal deposition of these gene products as well; thus, embryos lacking maternal and zygotic Fz and Fz2 will have no RP2/sib cells. Arm and Pan are also maternally deposited and embryos lacking both maternal and zygotic products for these genes again will have complete loss of RP2/sib cells. The important result, however, is that loss of function for all these genes do give partially penetrant but the same range of migration defects. Moreover, our results with wg mutants reveal a very intriguing aspect of neuronal identity specification: the neuronal identity specification can occur as early as two generations prior to their formation. These results suggest that the genetic program within the neuroectoderm and the neuroblast determines the identity and migratory behavior of post-mitotic neurons. This must occur via a stepwise activation of genetic programs, ultimately a combinatorial gene activity correctly specifying the migratory events. These results therefore indicate that the Wg-signaling in the neuroectoderm/NB4−2 specifies not just the genetic program of NB4−2, but also the GMC-1 and its daughter cells, RP2 and sib.

While this study does not identify all the players involved in these stepwise genetic programs, the results show that at least two downstream gene products are involved in this process: Cut and Zfh1. Both these are present in the RP2 neuron but not in the sib or the GMC-1. They are also not present in the parent NB4−2 or the neuroectoderm from which NB4−2 delaminates. Thus the temperature sensitive period of wg for the migration defects is restricted to stages well before the expression of cut or zfh1. In wg mutants, while the expression of these genes are rarely missing in those RP2s with defective migration, their expression is almost always affected in such RP2s. Finally, embryos mutant for cut and zfh1also exhibit similar migration defects as wg. Since Cut and Zfh1 are transcription factors, it must be that they regulate genes that are directly involved in cell migration such as a cell adhesion molecule.

Normal migration of sib may be dependent on the normal migration of RP2

Cell non-autonomous regulation of events is a common theme in development. Neuronal migration, like axon guidance, depends on interaction of the migrating neuron with its environment—other cells and the intercellular space. The results show that mutations in genes that are expressed in the RP2 but not in the sib or their parents (GMC-1 and NB4−2) causes an aberrant migration of the sib. This suggests one of three possibilities: one, the GMC-1 or the sib do express Cut and Zfh1 but at very low levels and we are not able to detect their expression in sib or GMC-1 using the antibodies. At least for cut, we have done whole mount RNA in situ and did not observe cut expression in the GMC-1 or sib. Two, whenever the migration of RP2 is affected, the migration of sib is also affected via a cell-non-autonomous influence of sib by RP2. This is supported by the observation that whenever the migration of RP2 is affected, the migration of the sib is also affected. Three, loss of function for cut and zfh1 alters the environment/cells with which a sib interacts during its migration, thereby affecting the migration of sib. Since the migration defects of the sib in both cut and zfh1 mutants are very similar, it seems more likely that there is an RP2-dependency for the migration of sib, or it is a combination of the RP2-dependency and the environmental changes with which the sib interacts.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Drs. Manfred Frasch, Zun Lai, Gary Struhl, Paul Adler, Mark Peifer and Roel Nusse for sharing antibodies and mutant stocks. I also would like to thank Kathy Matthews and Kevin cook at the Bloomington stock Center for fly stocks and Iowa Hybridoma Center for antibodies. I thank Ms. Smitha Krishnan for technical assistance. This work is funded by grants from the NIH (NIGMS and NINDS) to K.B.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler PN, Vinson C, Park WJ, Conover S, Klein L. Molecular structure of frizzled, a Drosophila tissue polarity gene. Genetics. 1990;126:401–416. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanot P, Brink M, Samos CH, Hsieh J-C, Wang Y, Macke JP, Andrew D, Nathans J, Nusse R. A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature. 1996;382:225–230. doi: 10.1038/382225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KM. The patched signaling pathway mediates repression of gooseberry allowing neuroblast specification by wingless during Drosophila neurogenesis. Development. 1996;122:2911–2923. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KM. frizzled and frizzled 2 play a partially redundant role in Wingless signaling and have similar requirements to Wingless in neurogenesis. Cell. 1998;95:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KM. Segment polarity genes in neuroblast formation and identity specification during Drosophila neurogenesis. BioEssays. 1999;21:472–485. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199906)21:6<472::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KM, van Beers E, Bhat P. Sloppy paired acts as the downstream target of Wingless in the Drosophila CNS and interaction between sloppy pairedand gooseberry inhibits sloppy paired during neurogenesis. Development. 2000;127:655–665. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KM, Apsel N. Upregulation of Mitimere and Nubbin acts through cyclin E to confer self-renewing asymmetric division potential to neural precursor cells. Development. 2004;131:1123–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KM, Schedl P. The Drosophila mitimere gene, a member of the POU family, is required for the specification of the RP2/sibling lineage during neurogenesis. Development. 1994;120:1483–1501. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KM, Schedl P. Requirements of engrailed and invected genes reveal novel regulatory interactions between engrailed/invected, patched, gooseberry and wingless during Drosophila neurogenesis. Development. 1997;124:1675–1688. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.9.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KM, Poole S, Schedl P. mitimere and pdm1 genes collaborate during specification of the RP2/sib lineage in Drosophila neurogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:4052–4063. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner E, Peter O, Schweizer L, Basler K. pangolin encodes a Lef-1 homologue that acts downstream of Armadillo to transduce the Wingless signal in Drosophila. Nature. 1997;385:829–833. doi: 10.1038/385829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: A common theme in animal development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3286–3305. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Struhl G. Wingless transduction by the Frizzled and Frizzled 2 proteins of Drosophila. Development. 1999;126:5441–5452. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu-LaGraff Q, Doe CQ. Neuroblast specification and formation regulated by wingless in the Drosophila CNS. Science. 1993;261:1594–1597. doi: 10.1126/science.8372355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita SC, Zipursky SL, Benzer S, Ferrus A, Shotwell SL. Monoclonal antibodies against the Drosophila nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1982;79:7929–7933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaziova I, Bhat KM. Generating Asymmetry: With and without self-renewal. Progress in Mol. And Sub. Biol. 2006:144–178. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69161-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaei HT, Lai C, Anton ES. Neuronal migration in the adult brain: are we there yet? Nat Rev Neruosci. 2007;8:141–151. doi: 10.1038/nrn2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CS, Doe CQ. Embryonic development of the Drosophila central nervous system. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1993. pp. 1131–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Klingensmith J, Nusse R. Signaling by wingless in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 1994;166:396–414. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornack DR, Rakic P. The generation, migration, and differentiation of olfactory neurons in the adult primate brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:4752–4757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081074998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnow RE, Wong LL, Adler PN. Dishevelled is a component of the frizzled signaling pathway in Drosophila. Development. 1995;121:4095–4102. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta B, Bhat KM. Slit signaling promotes the terminal asymmetric division of neural precursor cells in the Drosophila CNS. Development. 2001;128:3161–3168. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JR, Moon RT. Signal transduction through beta-Catenin and specification of cell fate during embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2527–2539. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida GH, Walsh CA. Genetic basis of developmental malformations of the cerebral cortex. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:637–40. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A-HJ, Samanta R, Wieschaus E. Wingless signaling in Drosophila embryo: zygotic requirements and the role of the frizzled genes. Development. 1999;126:577–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NH, Schafer B, Goodman CS, Holmgren R. The role of segment polarity genes during Drosophila neurogenesis. Genes Dev. 1989;3:890–904. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peifer M, Sweeton D, Casey M, Wieschaus E. wingless signal and zeste-white 3 kinase trigger opposing changes in the intracellular distribution of armadillo. Development. 1994;120:369–380. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese J, Yu X, Munnerlyn A, Eresh S, Hsu SC, Grosschedl R, Bienz M. LEF-1, a nuclear factor coordinating signaling inputs from wingless and decapentaplegic. Cell. 1997;88:777–787. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81924-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman RL, Rakic P. Neuronal migration, with special reference to developing human brain: a review. Brain Res. 1973;62:1–35. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried E, Perrimon N. Drosophila wingless: A paradigm for the function and mechanism of Wnt signaling. BioEssays. 1994;16:395–404. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JB, Bastiani MJ, Bate M, Goodman CS. From grasshopper to Drosophila: a common plan for neuronal development. Nature. 1984;310:203–207. doi: 10.1038/310203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M, Cavallo R, Dooijes D, van Beest M, van Es J, Loureiro J, Ypma A, Hursh D, Jones T, Bejsovec A, Peifer M, Mortin M, Clevers H. Armadillo coactivates Transcription Driven by the Product of the Drosophila Segment. Cell. 1997;88:789–799. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wai P, Truong B, Bhat KM. Cell division genes promote asymmetric localization of determinants and interaction between Numb and Notch in the Drosophila CNS. Development. 1999;126:2759–2770. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.12.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieschaus E, Nusslein-Volhard C. Looking at Embryos. In: Roberts DB, editor. Drosophila a practical approach. IRL Press; Oxford, Washington DC: 1986. pp. 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Wong K, Park HT, Wu JY, Rao Y. Slit proteins: molecular guidance cues for cells ranging from neurons to leukocytes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:583–91. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedvobnick B, Kumar A, Chaudhury P, Opraseuth J, Mortimer N, Bhat KM. Differential effects of Drosophila mastermind on asymmetric cell fate specification and neuroblast formation. Genetics. 2004;166:1281–1289. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.3.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]