Abstract

Investigation on the medical ethnobotany of the Q’eqchi Maya of Livingston, Izabal, Guatemala, was undertaken in order to explore Q’eqchi perceptions, attitudes, and treatment choices related to women’s health. Through participant observation and interviews a total of 48 medicinal plants used to treat conditions related to pregnancy, childbirth, menstruation, and menopause were collected and identified followed by the evaluation of 20 species in bioassays relevant to women’s health. Results of field interviews indicate that Q’eqchi cultural perceptions affect women’s health experiences while laboratory results (estrogen receptor and serotonin receptor binding assays) provide a scientific correlation between empirical medicinal plant use among the Q’eqchi and the pharmacological basis for their administration. These data can contribute to Guatemala’s national effort to promote a complementary relationship between traditional Maya medicine and public health services and can serve as a basis for further pharmacology and phytochemistry on Q’eqchi medicinal plants for the treatment of women’s health conditions.

Keywords: Guatemala, Women's health, Medicinal plants, Serotonin receptor assay, Estrogen receptor assay, Q'eqchi Maya

1. Introduction

Due to the unpleasant risks and side effects of long-term pharmaceutical treatment for women’s health conditions, specifically menstruation and menopause, women’s healthcare and the search for alternative treatment options have become an important focus of global scientific research. Of particular significance is the release of the findings on Hormone Therapy (HT) (estrogen plus progestin) by the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) (Rossouw et al., 2002), which displaced the common belief of the protective effects of HT for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Data from this randomized clinical trial revealed an increase in the incidence of heart disease by 29% and breast cancer by 26%. Thus, many women are reluctant to take HT due to the fear of developing cancer or experiencing unpleasant side effects. Meanwhile, in all aspects of women’s health -- menstruation, conception, pregnancy, birth, lactation, and the menopause -- an immense number of plant species have been and continue to be used by women and traditional healers worldwide (Stuart, 2004).

In Guatemala, as in other Central American countries, medicinal plants continue to be the most economically and culturally suitable treatment for a variety of health conditions, including those related to women’s health (Michel et al., 2006). Many of these plants have not been thoroughly documented, yet research on their biological and phytochemical potential may provide important information on their safety and efficacy, not only for women in Latin America, but for women worldwide who are searching for alternative natural therapies for menstrual and menopausal problems. (Nigenda, 2001). Economically, Guatemala is considered to be one of the poorest countries in Latin America, yet it is a nation extremely rich in traditional medical knowledge and biological resources (Cáceres et al., 1995). According to the Pan American Health Organization, 71% of its total population lives in poverty and less than 60% of the population has access to public services or biomedical health care facilities (PAHO, 1999). Guatemala continues to have one of the highest rates of infant mortality in Latin America (39 per 1,000 births in rural areas) and the institutional capacity to provide formal medical services for only 20% of birthing women (Villatoro, 1996). Health risks are even greater in the indigenous population, which makes up over 65% of the total national population (Villatoro, 1996). Being both women and indigenous, Maya women are the most marginalized and oppressed population in Guatemala (Villar Anleu, 1998). It is estimated that only 17% of Maya women receive any form of formal prenatal care (Lang and Elkin, 1997) and that, approximately eighty percent (80%) of childbirths among Maya women in Guatemala are attended in the home; 74.5% of which are attended by midwives, and 5.5% without any medical assistance (PAHO, 1994; Villatoro and Del Cid, 2003).

Although access to and utilization of biomedical care remains low, Guatemala has a long history of use of traditional Maya medicine, and approximately 80% of the current population rely on medicinal plants as their primary source of medical treatment (Cáceres, 1996). The majority of these botanicals, including those used for the treatment of women’s health conditions, have not been systematically documented or tested for safety and possible efficacy. Considering that a large portion of the female population of Guatemala are treated with these botanical medicines, there is an immediate need to document this information, collect the plant species used, and scientifically test each plant species in a rational and systematic manner.

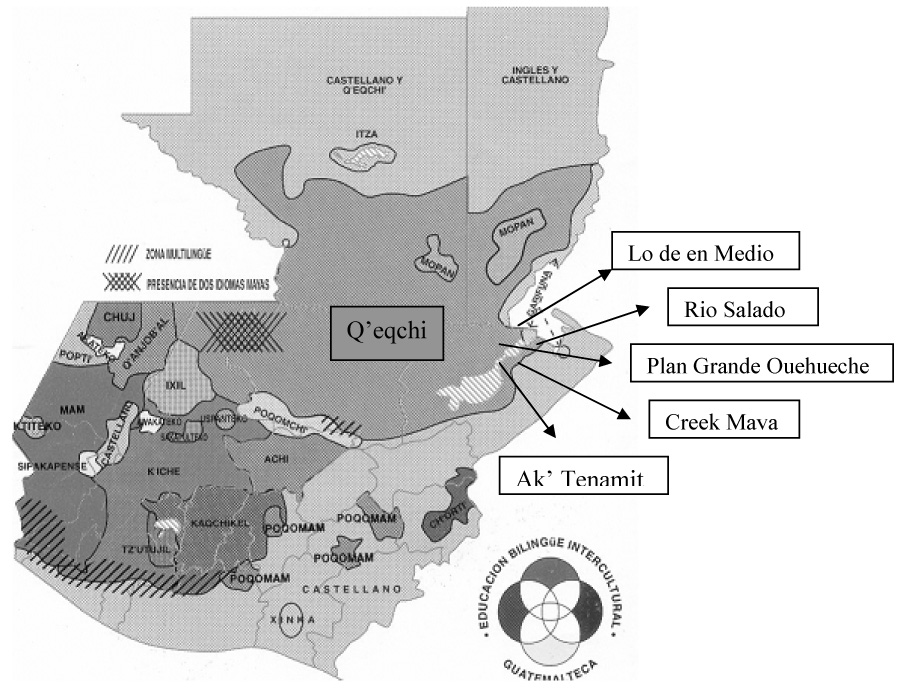

The Q’eqchi, also written as “Kekchi”, “K’ekchi”, “Keqchi”, or “Kekche”, are currently the third largest Maya population in Guatemala (700,000) and occupy the largest geographic area of any other ethnolinguistic group in the country (Figure 1) (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, 2002). Like most Maya communities, the Q’eqchi of the eastern lowlands maintain a rich tradition of medical beliefs and practices that include the use of the native flora to treat a variety of illnesses. Compared to the numerous ethnographic and ethnobotanical studies on the Q’eqchi from the highlands (Carlson and Eachus, 1978; Booth et al., 1992; Wilson, 1995; Cabarrus, 1998; Siebers, 1998; Coe, 1999; Collins, 2001; Hatse and De Ceuster, 2001), fewer studies have been made on the lowland Q’eqchi (Arnason et al., 1980; Collins, 2001; Amiguet et al., 2005) and no known ethnographic studies on the Q’eqchi from the eastern lowlands of Livingston, Izabal.

Figure 1.

A map of Guatemala showing Q’eqchi territory and principal research sites

Due to the limited number of interdisciplinary studies on the ethnobotany, biology, and chemistry of medicinal plants used to treat women’s health conditions in Guatemala (Cáceres et al, 1995; Girón et al, 1988; Cáceres 1996;), and the lack of ethnobotanical data on the Q’eqchi Maya of Livingston, this study sought to explore Q’eqchi perceptions, attitudes, and treatment choices related to women’s health followed by the biological and chemical investigation of the medicinal plants commonly used by the Q’eqchi to treat symptoms related to menstruation and menopause. The purpose of this study was to provide data related to the safety and efficacy of Q’eqchi botanical medicines with the hope of contributing to Guatemala’s national effort to improve public health measures in rural areas through the documentation of Maya medical practices.

2. Methodology

2.1 Study Site

The Municipality of Livingston is located in the eastern Department (or State) of Izabal within a region characterized as “a very humid lowland tropical rainforest” (Holdridge et al., 1971). At elevations ranging from 0 to 200 meters above sea level, Livingston receives over 3,000 mm of annual rainfall with humidity levels of 76 – 85%. The Municipality of Livingston is surrounded by water, with the Río Dulce being its main water source and aquatic “highway”. The Río Dulce is bordered on the South by the Sierra de Las Minas Mountains, on its North side by the Santa Cruz Mountains, and to the South by the Mico Mountains.

Ethnobotanical fieldwork, including interviews and plant collections, was undertaken in six localities: (a) in four rural Q’eqchi Maya villages, (b) at the site of the non-profit Q’eqchi organization Asociación Ak’Tenamit (in the village of Barra Lámpara), and (c) in the semi-urban town of Livingston (Figure 1). All of these sites are located in the State of Izabal, Municipality of Livingston. The four Q’eqchi villages were selected among the approximately 45 Q’eqchi villages in the Livingston area based on their geographic separation from each other and previous contact (1999–2003) made by the first author with village women, elders, and healers.

2.2 Interviews

Due to the limited ethnographic data on women’s health in Latin America and the lack of systematic explorations on the biological activity of plants used to treat women’s health complaints in Guatemala, extended participant observation (1999–2004) and 8-months of in depth ethnobotanical field study (November 2003-June 2004) was carried out (Michel et al., 2006). A total of 50 individuals from four rural Q’eqchi villages and the semi-urban town of Livingston were interviewed, including five traditional Q’eqchi male healers (curanderos), 4 Q’eqchi female midwives (comadronas) and one Garifuna midwife, and 40 Q’eqchi men and women with no specialty healing expertise ranging in age from 18 to 60 years of age.

Interview methods to gather information on Q’eqchi cultural beliefs and practices regarding women’s health included participant observation in women’s daily activities (hauling water, making tortillas, and childrearing), open and semi-structured interviews with men and women, plant walks, and focus group discussion. Interviews were conducted in Spanish by the first author or in Q’eqchi with the assistance of a local interpreter. To initiate an interview, information on age, gender, occupation, birthplace, and religious affiliation was gathered. Each participant was then asked to verbally list all health conditions specific to women, to share their beliefs regarding allowable and prohibited activities surrounding pregnancy, childbirth, menstruation, and menopause, and to name the plant species they use to treat these conditions. Interviews lasted anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours, depending on the informants level of knowledge and willingness to share their information. A total of 50 interviews were conducted (25 men, 25 women) using the UIC IRB (Institutional Review Board) protocol number 2002-0514; informed consent was received from all participants before the interviews began (Michel et al., 2006).

2.3 Plant sample collection and identification

Prior to initiating fieldwork, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was negotiated and signed between the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and the University of San Carlos in Guatemala City (USAC). Permission to collect botanical specimens was granted by the Guatemalan National Council on Protected Areas (CONAP). During or after each interview, plants stated to be used by the Q’eqchi to treat conditions related to pregnancy, childbirth, menstruation, and menopause were pointed out by each informant and collected. For each species, detailed documentation of location, use, preparation, administration, and healing concepts were recorded. Whenever possible, 5 herbarium specimens were collected for each plant and voucher specimens were deposited at the Herbarium of the School of Biology (BIGU) at the University of San Carlos and at the John G. Searle Herbarium of the Field Museum in Chicago (F). At the same time, 100–500 g of the used plant part were collected and dried in a solar herb dryer (built by J. Michel and R. Duarte) for biological assays. Initially, all plant collections were identified with the assistance of plant taxonomists at the BIGU herbarium, later through the help of taxonomists at the Field Museum.

2.4 Plant extract preparation

Dried plant material of each species was hand milled and approximately 100 g of each sample was extracted at the University of San Carlos laboratory with 500 ml of 95% ethanol. This process was repeated three times for an exhaustive extraction. The filtered solvents were combined and evaporated under vacuum, then stored at room temperature until it was time to ship them to UIC for testing in estrogen and serotonin competitive binding assays.

2.5 Estrogen receptor binding assays using ERα and ERβ receptors

Estrogen binding assays were performed according to previously published procedures (Obourn et al., 1993). This experiment is a competitive binding assay and was performed in order to determine the percent by which plant extracts inhibited the ability of radio labeled (³H) estradiol to bind to the estrogen receptor. Such inhibition would indicate that there may be a constituent within the plant that has binding affinity for that receptor.

Screening was performed using an EtOH extract concentration of 50 µg/mL. The reaction mixture consisted of 5 µL of each extract dissolved in dimethysulfoxide (DMSO), 5 µL of pure human recombinant diluted ERα (estrogen receptor alpha) or ERβ (estrogen receptor beta) (0.5 pmol) in ER binding buffer, 5 µL of ‘Hot Mix’ (400 nanomolar) (nM), prepared fresh using 3.2 µl of 25 µM, 83 Ci/mM ³H-estradiol, 98.4 µl of ethanol, 98.4 µL of ER binding buffer, and 85 µL ER binding buffer. 24 h before the assay, 50% v/v hydroxylapatite (HAP) slurry was prepared using 10 g hydroxylapatite in 60 mL of TE buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic (EDTA), pH 7.4) and stored at 4°C. ER binding buffer (10 mM Tris, 10% glycerol, 2 mM dithiothrietol, 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, pH 7.5), Erα [40 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM ethylene glycol (EGTA), pH 7.5] and Erβ (40 mM Tris, pH 7.5) wash buffers were prepared subsequently.

Incubation was performed at room temperature for 3 h after which the experiment was terminated by adding 100 µL of 50% HAP slurry to each tube followed by incubation on ice for 15 minutes, with vortexing every 5 min. Respective ER wash buffers were then added (1 mL), and the tubes were vortexed again and centrifuged at 2000x g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded and this wash step was repeated two more times until a pellet formed at the bottom of each tube. This HAP pellet, containing the ligand-receptor complex, was then re-suspended in 200 µL ethanol, and transferred to scintillation vials to measure binding affinities. Four mL of Cytoscint™ fluid was added per vial and the samples were counted. The percent inhibition of [³H]-estradiol bound to the ER by each extract was determined as follows: [(dpmsample – dpmblank)/(dpmDMSO - dpmblank) – 1] × 100. The competitive binding capability (percent) of the sample was then calculated in comparison with the inhibition of estradiol (50 nM, 100%). All samples were tested in duplicate.

2.6 In vitro serotonin receptor (5-HT1A,5A,7) binding assay

Radioligand binding studies for the serotonin subtypes 5-HT1A and 5-HT5A were performed according to procedures described by Rees and colleagues (Rees et al., 1994) with the purpose of determining the binding activity of ethanol extracts compared to [³H]5-carboxamidotryptamine (5-CT). For the 5-HT7 receptor binding studies, [³H] LSD was used to measure the binding ability of ethanol extracts. Cell culture conditions, membrane preparation, and assay procedures for this assay were performed at UIC according to methods previously described (Burdette et al., 2003). Following the same principles as the estrogen bioassay, the serotonin assay measures the ability of plant extracts to inhibit the binding of a radio-labeled ligand, in this case [³H] 5-carboxamidotryptamine, to the serotonin receptor. The presence of such inhibition would indicate that there may be a constituent within the plant that has binding affinity for that receptor.

To summarize, 2–4 mg/mL of plant extract in DMSO was diluted with sterile water for a final concentration of 50 µg/mL. Plant extracts were then added to Cos M6 (green monkey kidney) cell membranes in a cell homogenate preparation (750 µL) with [³H] 5-carboxamidotryptamine (5-CT) (1.0 nM final concentration, 200 µL), and assay buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 1mM EDTA and 1% ascorbic acid, pH 7.7). This solution was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Incubations were terminated by rapid filtration (Tomtec, 48 well harvester) through Printed Filtermat B filters and washed four times with 1 mL ice cold assay buffer. Filters were then dried and melted onto scintillation wax. [³H] 5-CT was used to determine nonspecific binding which accounted for <10% of total binding (defined by inclusion of 10 µM 5-CT). Competition and ligand binding data was then analyzed using non-linear curve fitting techniques (RSI, Radlig). All samples were tested in duplicate.

For the 5-HT7 bioassay, 2–4 mg/mL of each plant extract was diluted 40-fold in DMSO for a final concentration of 100 µg/mL. The assay was performed using the human recombinant Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell membrane and [³H] LSD (5 nM) in an incubation buffer (75 mM Tris-HCl, 1.25 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) (Roth et al., 1994). After a 1 h incubation period at 37°C the mixture for the 5-HT7 receptor was filtered over 934-AH Whatman filter paper that was pre-soaked in 0.5% polyethylenimine and washed twice in ice cold 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) using a 96-well Tomtec-Harvester (Orange, CT). The filter was then dried and suspended in Wallac microbeta plate scintillation fluid (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) and counted with a Wallac 1450 Microbeta liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). 5-HT (250 nM) was then used to define nonspecific binding, which accounted for <10% of total binding. Percent inhibition of [³H] ligand bound to each 5-HT receptor was then determined as [1 – (dpmsample – dpmblank)/(dpmDMSO – dpmblank) X 100. Each plant extract was tested in triplicate with the data presented representing the average of these three determinants.

3. Results

3.1 Q’eqchi concepts surrounding health and healing

The Q’eqchi possess a number of cultural perceptions around health and well being that differ from the Western biomedical model of disease etiology and that affect health-seeking behaviors, practices, and outcomes. The Q’eqchi Maya of Livingston perceive man as composed of the following elements: body (Tz’ejwalej), spirit (Musuq’ej), heart (Ch’oolej) and shadow (Muhel) (Siebers, 1998). Consequently, health and well being are dependent on finding balance and harmony between all of these elements. An imbalance in any of these elements can cause unhappiness and/or physical or psychological illnesses (i.e., spirit loss). According to the Q’eqchi, all living creatures on earth are seen as possessing a guardian spirit that can become angered if respect and homage are not paid prior to initiating a particular activity. For the Q’eqchi this translates into a number of rules and regulations that must be honored in order to maintain harmony, including prayers and rituals to Ajaw (God) and to the 13 local mountains, or Tzuultaq’a (mountain-valley), prior to hunting wild game, cutting down a tree for firewood, building a home, or collecting a plant for medicinal purposes. These prayers and incantations usually incorporate the use of candles, herbs, and incense, and are commonly performed in the forest or in a cave by a healer or community leader that has received training in Q’eqchi prayers and rituals. In regard to healing practices, the Q’eqchi believe that these ceremonies are essential to a medicinal plant’s efficacy. Furthermore, if such ceremonies are not performed, the patient as well as the healer may suffer from a more severe illness or be attacked by a venomous snake.

Overall, the Q’eqchi consider women to have a weaker constitution than men, due, in part, to the debilitating effects of menstruation, pregnancy, and post-partum recovery. There are a number of cultural taboos and restrictions surrounding women’s health, which affect the way Q’eqchi women experience these conditions (Michel et al., 2006).

3.2 Q’eqchi medicinal plants for women’s health

A total of 48 plants belonging to 26 families were mentioned by the Q’eqchi for their use in treating women’s health ailments (Table 1). Of these 48 plants, 31 were collected from the field, 30 of which were identified to species and one to genus. 17 of the 48 plants, belonging to 13 plant families, could not be located or collected to verify their correct taxonomic identity. Five of these seventeen plants did not grow in the area but were purchased from the market. Market plants were available in bulk, but without the presence of fruits or flowers for identification purposes. Table 2 presents the common names and uses of these plants.

Table 1.

List of 31 plants collected in Guatemala and used by the Q’eqchi to treat women’s health complaints

| Species/Voucher Numbera | Q'eqchi (Q)/Spanish (S) Name | Part Usedb | Medicinal Use | # male informants | # female informants | Habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camphyloneurum sp. (Polypodiaceae)/JM24 | Cola de pavo (S) | Lf | Body aches | 4 | 1 | Forest |

| Cassia reticulata Willd. (Fabaceae)/JM30 | Barajo (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea | 4 | 4 | Open fields |

| Cecropia peltata L. (Cecropiaceae)/JM26 | Guarumo (S) | Lf | Expel placenta, lower womb, insomnia, nerves | 11 | 11 | Open fields |

| Cephaelis tomentosa (Aubl.) Vahl. (Rubiaceae)/JM33 | Ak Pere Tzo’ (Q) | Lf | Postpartum hemorrhaging | 5 | 0 | Forest |

| Cissampelos tropaeolifolia DC. (Menispermaceae)/JM39 | Bejuco de ombligo (S) | Lf | Release placenta | 6 | 6 | Forest |

| Citrus aurantium L. (Rutaceae)/JM27 | Naranja agria (S) | Lf | Nerves, insomnia, body aches, body sweats | 12 | 12 | Cultivated |

| Clidemia setosa (Triana) Gleason (Melastomataceae)/JM50 | Ixq Q’een (Q) | Lf | Fertility regulation | 7 | 0 | Forest |

| Clidemia petiolaris (Schlecht. et Cham.) Schlecht. ex Triana (Melastomataceae)/JM63 | Xa bol q’een (Q) | Lf | Postparum hemorrhaging, fertility regulationc, blood clots | 5 | 0 | Forest |

| Crossopetalum eucymosum (Loes. et Pitt.) Lundell (Celastraceae)/JM13 | Ra Mox (Q) | Lf | Cold body, body aches | 2 | 0 | Forest |

| Dioscorea bartletti Morton (Dioscoreaceae)/JM08 | Cocolmeca (S) | Rh | Stagnant blood, anemia | 6 | 2 | Forest |

| Henriettea cuneata (Standl.) Williams (Melastomataceae)/JM100 | Ixq Q’een (Q) | Lf | Fertility regulation | 2 | 0 | Forest |

| Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. (Malvaceae)/JM06 | Utz Uj’ (Q) | Lf, Fl | Postpartum hemorrhaging, infertility, nerves | 10 | 18 | Cultivated |

| Hyptis verticillata Jacq. (Lamiaceae)/JM05 | Verbena (S) | Lf | Release placenta, erratic menses | 0 | 4 | Open fields |

| Justicia breviflora (Nees) Rusby (Acanthaceae)/JM37 | Rax Pim (Q) | Lf | Menorrhagia, postpartum hemorrhagec | 2 | 0 | Forest |

| Justicia fimbriata (Nees) V.A.W. Graham (Acanthaceae)/JM16 | Numay Pim (Q) | Lf | Insomnia, excess body heat | 5 | 0 | Forest |

| Mimosa pudica L. (Mimosaceae)/JM57 | Dormilona (S) | Lf | Insomnia | 8 | 8 | Open fields |

| Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae)/JM59 | Sorosi (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea | 1 | 3 | Open fields |

| Neurolaena lobata (L.) R. Br. (Asteraceae)/JM31 | Kamank (Q) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea, vaginal infection | 8 | 24 | Open fields |

| Ocimum micranthum Willd. (Lamiaceae)/JM04 | Obej' (Q) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea, vaginal hemorraging | 1 | 3 | Cultivated, open fields |

| Piper aeruginosibaccum Trelease (Piperaceae)/JM25 | Ampom (Q) | Lf | Anemia, body aches | 4 | 0 | Forest |

| Piper auritum HBK. (Piperaceae)/JM03 | Ob'el (Q) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea, galactagogue | 16 | 16 | Open fields |

| Piper diandrum C.DC. (Piperaceae)/JM45 | Nin qui ru chaq’ q'een (Q) | Lf | Body aches, reposition womb | 3 | 0 | Forest |

| Piper hispidum Sw. (Piperaceae)/JM32 | Puchuq (Q) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, body aches | 5 | 0 | Forest |

| Piper tuerckheimii C. DC. (Piperaceae)/JM14 | Caite de Diablo (S) | Lf | Inflammation, “loss of senses” | 4 | 0 | Forest |

| Rondeletia stachyoidea Donn. Smith (Rubiaceae)/JM41 | Kandel Che (Q) | Lf | Reposition womb, insomnia, “witchcraft” | 3 | 0 | Forest |

| Scoparia dulcis L. (Schrophulariaceae)/JM58 | “Como Escobillo” (S) | Lf | Labor pains | 0 | 9 | Open fields |

| Sida rhombifolia L. (Malvaceae)/JM94 | Mesbel (Q) | Lf | Labor pains, burning urine | 0 | 8 | Open fields |

| Smilax domingensis Willd. (Smilacaceae)/JM60 | Chub Ixim (Q), Cocolmeca (S) | Rh | Night sweats | 4 | 8 | Forest |

| Solanum americanum Miller (Solanaceae)/JM72 | Hierba Mora (S), Quilete (S), Macuy (Q) | Lf | Anemia, dysmenorrhea | 2 | 4 | Open fields |

| Zebrina pendula Schnizl. (Commelinaceae)/JM106 | Cha cha (Q) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea | 2 | 1 | Cultivated |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Zingiberaceae)/JM01 | Xinxibeer (Q) | Rh | Dysmenorrhea, night sweats | 0 | 10 | Cultivated |

Voucher herbarium collection number (JM = Joanna Michel #)

Fl = Flower, Lf = Leaf, Rh = Rhizome

When combined with other herbs

Table 2.

Recorded names and uses of plants for women’s health complaints by the Q’eqchi but for which voucher specimens could not be collected

| Q'eqchi (Q)/Spanish (S) Name | Part Useda | Q’eqchi Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Cotacám (Q) | Lf | Amenorrhea |

| Samat (Q)/Culantro (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea |

| Manzanilla (S) | Fl | Dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, insomnia |

| Pericón (S) | Lf, Fl | Dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea |

| Bak Chayou (Q)/Achiote (S) | Lf | Accelerate childbirth |

| Chacal (Q)/Indio Desnudo (S)/Palo jiote (S) | Bk | Vaginal infections |

| Papay (Q)/Papaya (S) | Sd | Abortive |

| Epazote (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea |

| Hierba de cáncer (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea |

| Orej’ (Q)/Oregano (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea |

| Romero (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea |

| O' (Q)/Aguacate (S) | Sd | Abortive |

| Pimenta gorda (S) | Sd, Lf | Dysmenorrhea, facilitate childbirth |

| Pimenta negra (S) | Sd | Facilitate childbirth |

| Yut-it (Q)/San Diego (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea |

| Ruda (S) | Lf | Dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea |

| Valeriana (S) | Rt | Nerves, insomnia |

Fl = Flower, Lf = Leaf, Sd = Seed, Rt = Root, Bk = Bark

3.3 In vitro results in estrogen and serotonin bioassays

Of the 12 species tested in estrogen receptor binding assays, five (42%) bound to the ERα and six plant extracts (50%) bound to the ERβ, with activity being defined as greater than 50% binding at a concentration of 50 µg/ml (Table 3). Smilax domingensis had the most significant binding to the ERα receptor (67%), while Piper hispidum displayed the greatest activity in the ERβ bioassay (76%). With the exception of P. hispidum, all 12 plants showed similar binding affinity for both receptors. The binding preference of P. hispidum for the ERβ receptor suggests that it may contain compounds that act as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) which bind to estrogen receptors and produce estrogen-like (agonist) effects in some tissues (e.g. skeletal and cardiovascular system) and estrogen-blocking (antagonist) effects in other tissues (e.g. uterus and breast)‥

Table 3.

In vitro estrogen and serotonin bioassay results for 12 species used by the Q’eqchi for women’s health complaints

| Species | Plant Parta | ERαb | ERβc | 5HT1Ab | 5HT5Ab | 5HT7c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cassia reticulata Willd. (Fabaceae); JM30 | Lf | NT | NT | NT | NT | 48 |

| Cecropia peltata L. (Cecropiaceae); JM26 | Lf | 61 | 57 | 62 | 38 | 81 |

| Cephaelis tomentosa (Aubl.) Vahl. (Rubiaceae) JM33 | Lf | 48 | 52 | 81 | 78 | 67 |

| Cissampelos tropaeolifolia DC. (Menispermeaceae); JM39 | Lf | 51 | 46 | 88 | 51 | 94 |

| Clidemia setosa (Triana) Gleason (Melastomataceae); JM50 | Lf | NT | NT | NT | NT | 47 |

| Clidemia petiolaris (Schlecht. & Cham.) Schlecht. ex Triana (Melastomataceae); JM63 | Lf | NT | NT | NT | NT | 44 |

| Dioscorea bartletti Morton (Dioscoreaceae); JM08 | Rh | 51 | 51 | NT | NT | NT |

| Henriettea cuneata (Standl.) Williams (Melastomataceae); JM100 | Lf | 56 | 55 | 55 | 43 | NT |

| Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. (Malvaceae); JM06 | Lf | 43 | 38 | 61 | 70 | NT |

| Hyptis verticillata Jacq. (Lamiaceae); JM05 | Lf | NT | NT | NT | NT | 89 |

| Justicia breviflora (Nees) Rusby (Acanthaceae); JM37a | Lf | 32 | 24 | 72 | 43 | 70 |

| Justicia fimbriata (Nees) V.A.W. Graham (Acanthaceae); JM16 | Lf | 28 | 33 | 48 | 28 | 17 |

| Neurolaena lobata (L.) R. Br. (Asteraceae); JM31 | Lf | NT | NT | NT | NT | 86 |

| Piper aeruginosibaccum Trelease (Piperaceae); JM25 | Lf | NT | NT | NT | NT | 82 |

| Piper auritum HBK. (Piperaceae); JM03 | Lf | 49 | 42 | 66 | 68 | 83 |

| Piper hispidum Sw. (Piperaceae); JM32 | Lf | 49 | 76 | 63 | 76 | 96 |

| Piper tuerckheimii C. DC. (Piperaceae); JM14 | Lf | NT | NT | NT | NT | 72 |

| Rondeletia stachyoidea Donn. Smith (Rubiaceae); JM41 | Lf | 31 | 36 | 51 | 37 | 26 |

| Smilax domingensis Willd. (Smilacaceae); JM60 | Rh | 67 | 69 | 27 | 2 | 16 |

| Zebrina pendula Schnizl. (Commelinaceae); JM106 | Lf | NT | NT | NT | NT | 0 |

Lf = Leaf; Rh = Rhizome; NT = Not Tested

Tested by MDS Pharma Services (Bothell, Wa.) at 50 µg/ml

Tested by UIC/NIH Center for Botanical and Dietary Supplements Research (Chicago, IL) at 100 µg/ml

Nine out of the 11 species (82%) that were tested bound (> 50% binding at 50 µg/ml) to the 5-HT1A serotonin receptor, with Cissampelos tropaeolifolia showing the most significant binding activity (88%). Five out of 11 species (45%) bound to the 5-HT5A receptor with Piper poeppigiana demonstrating the strongest binding (78%), followed by P. hispidum (76%) and Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (70%). Ten of the 16 species (63%) tested bound to the 5-HT7 serotonin bioassay assay, with activity being defined as greater than 50% binding at 100 µg/ml. P. hispidum (96%), C. tropaeolifolia (94%), and Hyptis verticillata (89%) showed the greatest binding to the 5-H T7 receptor. With the exception of Rondeletia stachyoidea, all 8 extracts tested positive in both the 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 bioassay. 5-HT1A and 7 have similar drug sensitivities, similar structural configuration, and are both located in the hypothalamus where they might be involved in hormonal regulation (Burdette et al., 2003). Similar affinity by the plant extracts in this study for both receptors suggests further support for these claims.

4. Discussion

Since the 1950’s, hormonal therapies (HT) containing estrogen and/or progesterone have been the mainstay for the treatment of premenstrual distress and menopausal symptoms. More recent advances in the treatment of PMS and menopause also include the use of antidepressants such as sertraline (Zoloft), fluoxetine (Prozac), and paroxetine (Paxil) that act as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Considering recent concern over the increase of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and stroke associated with the use of steroidal hormone therapy (Rossouw et al., 2002), and the unpleasant side affects associated with the use of SSRIs (nausea, diarrhea, decreased libido), studies that search for alternative therapies and mechanisms of action to treat women’s health complaints are needed (Rossouw et al., 2002; Mahady et al., 2003).

The purpose of the present work was to provide scientific support for the medicinal uses of plants by the Q’eqchi for the treatment of women’s health disorders, particularly menstrual and menopausal symptoms and discomfort. The results demonstrate that plants used by the Q’eqchi for these purposes showed significant in vitro activity in estrogen and serotonin receptor binding assays. Although the absence or presence of activity through in vitro bioassay evaluation does not necessarily correspond directly to in vivo efficacy, nevertheless these data do suggest that plants used traditionally to treat women’s health complaints by the Q’eqchi have a plausible mechanism of action and therefore warrant further animal and human studies.

A literature review of the plants used by the Q’eqchi for women’s health complaints reveals that many of these species are also used traditionally to relieve women’s health complaints in other Latin American countries and cultural groups. For example, the leaf of Cecropia peltata (Cecropiaceae; Table 1, JM26), or Guarumo, also known as Trumpet Tree by the Maya of Belize and Guatemala and by the Paya of Honduras, used by the Q’eqchi to expel the placenta, lower the womb, and to treat nervousness and insomnia, is also commonly used in a bath for rheumatism, and as a tea to treat nervous conditions, menstrual problems, and to ease the pain of childbirth (Lentz, 1989; Comerford, 1996; Cáceres, 1996). Dioscorea bartletti Morton (Dioscoreaceae; Table 1, JM08) is among the many species of Dioscorea referred to as wild yam which are known to have a long history of medicinal use in Central America and were popular among the ancient Aztec and Maya people. The Q’eqchi administer a decoction of the rhizome of D. bartletti to treat stagnant blood and anemia, whereas other groups in Latin America have used decoctions of the rhizome of various Dioscorea sp. to relieve the pain of childbirth and cramps, to treat painful menstruation, ovarian pain and to alleviate vaginal cramping (Rodriguez Martinez, 1987; Ososki et al., 2002). The leaves of Piper auritum (Piperaceae; Table 1, JM03) are used as a tea by the Q’eqchi to treat dysmenorrhea or placed on the breast as a galactagogue, while the Garifuna of Guatemala use the leaves of P. auritum to treat ovarian pain, rheumatism, and gonorrhea (Giron et al., 1991). The leaves of this species are also used in Nicaragua to treat anemia, rheumatism, and to ease the pain of childbirth (Barrett, 1994). In Mexico P. auritum leaves are used as an emmenagogue and to speed childbirth, whereas the root is administered to remove the placenta (Browner, 1985), and in Panama the leaves are used as an emmenagogue (Gupta et al., 1996). Piper hispidum (Piperaceae; Table 1, JM32), known as puchuq by the Q’eqchi and used as a tea to treat dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, and body aches is also commonly known as cordoncillo and also used in Nicaragua to ease aches and pains (Coe and Anderson, 1996), in Peru to regulate menstruation, and in the Amazon to treat urinary infections (Duke and Vásquez, 1994).

A literature review of the biological activity of the aforementioned plants revealed that only 4 plants; Dioscorea sp., Hyptis verticillata, Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, and Scoparia dulcis had corresponding published biological data relevant to their traditional use in treating women’s health complaints. Dioscorea sp., or wild yam, is commonly used as an ingredient of commercial topical progesterone creams to treat menopausal hot flashes, but its effectiveness has not been demonstrated (Komesaroff, 2001). Yams are known to contain sapogenins, specifically diosgenin, a precursor to progesterone. While the human body is incapable of transforming diosgenin into progesterone, yams do appear to exert a hormonal influence when taken orally (not topically) (Higdon et al., 2001). Oral administration of diosgenin to female rats induced an increase in uterine weight, vaginal opening and vaginal cell proliferation, and reduced bone loss; suggestive of an estrogenic mechanism of action (Higdon et al., 2001). In our study, D. bartlettii, used by the Q’eqchi to treat stagnant blood and anemia, displayed mild in vitro binding affinity (51%) for both the estrogen alpha and beta receptor. The aerial parts of Hyptis verticillata, exhibited in vitro anti-inflammatory activity as determined by the extract’s ability to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis (ether, petroleum ether and acetone extracts) and cyclooxygenase (50 µg/mL) (Kuhnt et al., 1995). Anti-inflammatory medications are often effective in relieving menstrual discomfort and may explain the traditional use of H. verticillata by the Q’eqchi to release the placenta and to treat erratic menstruation. Our results on H. verticillata (89% binding to the 5HT7 receptor) suggest that there may also be a serotonergic mechanism of action and rationale for the use of H. verticillata. Hibiscus rosa-sinenses is a popular herbal remedy among numerous geographically and culturally distinct populations and include flower extracts used as emmenagogues, abortifacients, contraceptives, and labor inducers (Kabir et al., 1984). There are a number of biological studies on H. rosa-sinensis from India. One study examined the effects of the administration of the benzene extract to female albino mice. Results showed a dose-dependent increase in the duration of estrus, premature cornification of vaginal epithelium and an increase in uterine weight, thereby suggesting mild estrogenicity (Murthy et al., 1997). Furthermore, the authors of this paper concluded that an increase in ovarian ascorbic acid was also an indication of the depletion of pituitary LH. In contrast, another study indicated a dose-dependent suppression of an estrone-induced gain in uterine weight in bilaterally ovariectomized immature rats thereby concluding that both the alcoholic and benzene extract of H. rosa-sinensis extract demonstrated antiestrogenic activity (Kholkute and Udupa, 1976). Results on the estrogenic activity of H. rosa-sinensis from the present study do not support these findings, but rather, suggest that H. rosa-sinensis may exhibit serotonergic activity (61% and 70% binding to the 5HT1A and 5HT5A serotonin receptors, respectively). Although the estrogenic and serotonergic activity of Scoparia dulcis was not tested in the present study, data from in vitro ligand binding studies conducted in Belgium (Hasra et al., 1997) revealed that an ethanol extract of S. dulcis showed binding affinity to the 5HT1A serotonin receptor (> 50% at 100 µg/mL). Furthermore, scoparinol, a diterpene isolated from S. dulcis, demonstrated sedative activity by a marked potentiation of pentobarbital-induced sedation, showing a significant effect on both the duration and onset of sleep (p < 0.01) (Ahmed et al., 2001).

5. Conclusions

The majority of the world’s population does not have access to pharmaceuticals, including steroid based pharmaceuticals to treat women’s health complaints (World Health Organization, 2004). Studies show that, instead, many women worldwide rely on herbal remedies to treat hormonally-regulated health conditions (Browner, 1985; Cáceres et al., 1995; Duke, 1994; Ososki et al., 2002). Our results present data for the first time on the traditional use and in vitro biological activity of medicinal plants used by the Q’eqchi Maya of Livingston, Izabal. The results of this work provide a scientific basis to support the traditional use of these plants by the Q’eqchi, yet further research is needed to access the safety and toxicity profile of these empirically-based medicinal products. Above all, due to the popularity of herbal therapies used worldwide for the treatment of women’s health complaints, coupled with the lack of scientifically tested safe and effective treatment options to treat menstrual and menopausal symptoms, our results provide additional data on Latin American herbal remedies toward the development of standardized phytomedicines to treat women’s health conditions.

The Ministry of Health in Guatemala is in the process of recognizing traditional Maya medicine as a formal system of healthcare in Guatemala (PAHO, 2001). In the past, the government created a program of traditional and alternative medicine (Programa Nacional de Medicina Popular Tradicional Alternativa) in an attempt to sensitize the biomedical community on traditional medical practices and to establish a safer environment under which traditional healers could practice. A preliminary inventory of healers was made in 2004, and some workshops were held to coordinate these activities toward the creation of this national program. A desire was also manifested to support a national medical herbarium (Herbario Médico Nacional) that would house the most frequently used and documented medicinal plants in the country.

Although Guatemala’s Acuerdo de Paz or postwar Peace Accords signed in 1996 officially acknowledged the sovereign rights of the Maya to practice their traditional medical practices, nonetheless, most Maya practitioners remain outside of any formal medical sector, lacking any specific support from the government (Nigenda, 2001). In terms of medicinal plants used in their practice, these remain largely unstudied and there are currently no formal government initiatives to study the safety and efficacy of the botanicals currently being used by the majority of the national population. The only initiative put into action for the past 20 years or so comes from the academic sector, in an effort to screen and find the scientific rationale on the use of medicinal plants by these populations.

Finally, it may be stated that the qualitative field results obtained in the present study have contributed to a better understanding of Maya medical beliefs and cultural concepts surrounding women’s health, while the experimental laboratory results support their empirical use by the Q’eqchi, compel the need to further investigate these and other herbal treatments remedies, and underscore the need and value of government programs and initiatives that support such endeavors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable friendship and generosity of the Q’eqchi Maya of Livingston, Izabal and the support of Asociación Ak’Tenamit (Barra Lampara, Guatemala). PhD research funding for JLM was made possible by a US Fulbright Fellowship (2003), a pre-doctoral fellowship from the American Foundation of Pharmaceutical Education (2001–2005), and the generous monetary gift of Djaja Doel Soejarto from his Senior University Scholar Fund.

This study was partly funded by NIH grant AT002381 awarded to G. Mahady and P50 AT00155 jointly provided to the UIC/NIH Center for Botanical Dietary Supplements Research by the Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institute for General Medical Sciences, Office for Research on Women’s Health, National Center for Complementary, and Alternative Medicine. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmed M, Shikha HA, Sadhu SK, Rahman MT, Datta BK. Analgesic, diuretic, and anti-inflammatory principle from Scoparia dulcis. Pharmazie. 2001;56:657–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiguet VT, Arnason JT, Maquin P, Cal V, Vindas PS, Poveda L. A consensus ethnobotany of the Q'eqchi Maya of Southern Belize. Economic Botany. 2005;59:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Arnason T, Uck F, Lambert J, Hebda R. Maya medicinal plants of San Jose Succotz, Belize. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1980;2:345–364. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(80)81016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asprey GF, Thornton P. Medicinal plants of Jamaica. III. West Indian Medical Journal. 1955;4:69–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balick MJ, Nee MH, Atha DE. Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Belize, with common names and uses. Bronx, NY: New York Botanical Gardens Press; 2000b. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett B. Medicinal plants of Nicaragua's Atlantic coast. Economic Botany. 1994;48:8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Booth S, Bressani R, Johns T. Nutrient content of selected indigenous leafy vegetables consumed by the Kekchi people of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 1992;5:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Browner CH. Plants used for reproductive health in Oaxaca, México. Economic Botany. 1985;39:482–504. doi: 10.1007/BF02858757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette JE, Liu J, Chen SN, Fabricant DS, Piersen CE, Barker EL, Pezzuto JM, Mesecar A, Van Breemen RB, Farnsworth NR, Bolton JL. Black cohosh acts as a mixed competitive ligand and partial agonist of the serotonin receptor. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51:5661–5670. doi: 10.1021/jf034264r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabarrus CR. La cosmovisión Q'eqchi en proceso de cambio. Guatemala City: CHOLSAMAJ; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres A. Plantas de uso medicinal en Guatemala. Guatemala City: Universidad de San Carlos; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres A, Menendez H, Mendez E, Cohobon E, Samayoa BE, Jauregui E, Peralta E, Carrillo G. Antigonorrheal activity of plants used in Guatemala for the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1995;48:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01288-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson R, Eachus F. El mundo espiritual de los Kekchies. Instituto Indigenista Nacional. 1978;Vol. XIII:37–73. [Google Scholar]

- Coe FG, Anderson GJ. Screening of medicinal plants used by the Garifuna of Eastern Nicaragua for bioactive compounds. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1996;53:29–50. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)01424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe M. Breaking the Maya code. New York: Thames & Hudson; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Collins DA. From woods to weeds: Cultural and ecological transformations in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. New Orleans: Master's thesis, Tulane University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Comerford SC. Medicinal plants of two Mayan healers from San Andres, Peten, Guatemala. Economic Botany. 1996;50:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Duke JA, Vásquez R. Amazonian ethnobotanical dictionary. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Girón LM, Freire V, Alonzo A, Cáceres A. Ethnobotanical survey of the medicinal flora used by the Caribs of Guatemala. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1991;34:173–187. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90035-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girón LM, Aguilar GA, Cáceres A, Arroyo GL. Anticandidal activity of plants used for the treatment of vaginitis in Guatemala and clinical trial of a Solanum nigrescens preparation. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1988;22:307–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta MP, Monge A, Karikas GA, Lopez de Cerain A, Solis PN, de Leon E, Trujillo M, Suarez O, Wilson F, Montenegro G, Noriega Y, Santana AI, Correa M, Sanchez C. Screening of Panamanian medicinal plants for brine shrimp toxicity, crown gall tumor inhibition, cytotoxicity and DNA intercalation. Pharmaceutical Biology. 1996;34:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hasrat JA, Pieters L, De Backer JP, Vauquelin G, Vlietinck AJ. Screening of medicinal plants from Suriname for 5-HT1A ligands: Bioactive isoquinoline alkaloids from the fruit of Annona muricata. Phytomedicine. 1997;4:133–140. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(97)80059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatse I, De Ceuster P. Cosmovisión y espiritualidad en la agricultura Q'eqchi. Cobán, Guatemala: Centro Bartolomé de Las Casas; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Higdon K, Scott A, Tucci M, Benghuzzi H, Tsao A, Puckett A, Cason Z, Hughes J. The use of estrogen, DHEA, and diosgenin in a sustained delivery setting as a novel treatment approach for osteoporosis in the ovariectomized adult rat model. Biomedical Sciences Instrumentation. 2001;37:281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdridge LR, Grenke WC, Hatheway WH, Llang T, Tosi JAJ. Forest environments in tropical life zones: A pilot study. Oxford-New York - Toronto – Sydney - Braunschweig: Pergamon Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Características de la población y de los locales de habitación cansados. Guatemala City: Censos Nacionales XI de Población y VI de Habitación; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir SN, Bhattacharya K, Pal AK, Oakrashi A. Flowers of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, a potential source of contragestative agent: I. Effect of Benzene extract on implantation of mouse. Contraception. 1984;29:386–397. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(84)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholkute SD, Udupa KN. Effects of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis on pregnancy of rats. Planta Medica. 1976;29:321–329. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1097671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komesaroff PA, Black CV, Cable V, Sudhir K. Effects of wild yam extract on menopausal symptoms, lipids and sex hormones in healthy menopausal women. Climacteric. 2001;4:144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnt M, Probstle A, Rimpler H, Bauer R, Heinrich M. Biological and pharmacological activities and further constituents of Hyptis verticillata. Planta Medica. 1995;61:227–232. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang JB, Elkin ED. A study of the beliefs and birthing practices of traditional midwives in rural Guatemala. Journal of Nurse Midwifery. 1997;42:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0091-2182(96)00069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws MB, Carballeira N. Use of nonallopathic healing methods by Latina women at midlife. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.524-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz DL. Medicinal and other economic plants of the Paya of Honduras. Economic Botany. 1989;47:358–370. [Google Scholar]

- Mahady GB, Parrot J, Lee C, Yun GS, Dan A. Botanical dietary supplement use in peri- and postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2003;10:65–72. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel JL, Mahady GB, Veliz M, Soejarto DD, Cáceres A. Symptoms, attitudes and treatment choices surrounding menopause among the Q'eqhchi Maya of Livingston, Guatemala. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;63:732–742. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy DRK, Reddy CM, Patil SB. Effect of benzene extract of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis on the estrous cycle and ovarian activity in albino mice. Biological and Pharmeutical Bulletin. 1997;20:756–758. doi: 10.1248/bpb.20.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigenda G, Mora-Flores G, Aldama-Lopez S, Orozco-Nunez E. The practice of traditional medicine in Latin America and the Caribbean: The dilemma between regulation and tolerance. Salud Pública de México. 2001;43:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obourn JD, Koszewski NJ, Notides AC. Hormone and DNA-binding mechanisms of the recombinant human estrogen receptor. Biochemistry. 1987;32:6229–6236. doi: 10.1021/bi00075a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orellana SL. Indian medicine in highland Guatemala: The Pre-Hispanic and Colonial periods. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ososki AL, Lohr P, Reiff M, Balick MJ, Kronenberg F, Fugh-Berman A, O'Connor B. Ethnobotanical literature survey of medicinal plants in the Dominican Republic used for women's health conditions. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2002;79:285–298. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAHO. Medicinas y terapias indígenas en la atención primaria de salud: El caso de las Mayas de Guatemala. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- PAHO. Traditional health systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: Base information technical project report. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- PAHO. Concepciones y prácticas de salud reproductiva de las mujeres de las communidades K'iche y K'aqchikel en Guatemala. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rees S, den Daas I, Foord S, Goodson S, Bul D, Kilpatrick G, Lee M. Cloning and characterization of the human 5-HT5A serotonin receptor. FEBS Letters. 1994;355:242–246. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robineau L, Weniger B, editors. Elements for a Caribbean pharmacopeia: Tramil 3 Workshop Havana, Cuba, November 1988. Santo Domingo: Enda-caribe; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Martinez NR. Plantas alimenticias y medicinales. Santiago, República Dominicana: Editora Nani; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL, Craigo SC, Choudhary MS, Uluer A, Monsma FJ, Jr, Shen Y, Meltzer HY, Sibley DR. Binding of typical and atypical antipsychotic agents to 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 and 5-hydroxytryptamine-7 receptors. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;268:1403–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebers H. Tradición, modernindad e identidiad en los Q'eqchies. Cobán, Alta Verapaz: Centro Ak'Kutan; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Silfen SL, Ciaccia AV, Bryant HU. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: tissue selectivity and differential uterine effects. Climacteric. 1999;2:268–283. doi: 10.3109/13697139909038087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley PC, Steyermark JA. Flora of Guatemala. Vol. 24. Fieldiana: Botany; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart D. Dangerous garden: the quest for plants to change our lives. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Villar Anleu L. La Flora Silvestre de Guatemala. Guatemala City: Editorial Universitaria: Universidad de San Carlos Guatemala; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Villatoro E, Del Cid P. Salud integral de las mujeres. Guatemala: FLASCO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Villatoro E. Las plantas: Recurso terapéutico a través de la historia. Tradiciones de Guatemala. 1996;45:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva: The World Health Report. 2004

- Wilson R. Maya resurgence in Guatemala: Q'eqchi experiences. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]